1. Introduction

The challenge of reconciling general relativity [

1] with quantum mechanics remains one of the deepest problems in contemporary theoretical physics [

2]. At Planck-scale energies [

3], the classical conception of spacetime as a smooth differentiable manifold begins to break down, prompting the search for frameworks where geometry—and even spacetime itself—may emerge from deeper algebraic or quantum principles. While many quantum gravity programs [

4], including string theory [

5] and loop quantum gravity [

6], still operate within a differential-geometric paradigm, recent developments invite a reassessment of the foundations of geometry itself.

A central milestone in modern geometry is the

Calabi Conjecture, proposed by Eugenio Calabi in the 1950s [

7] and proven by Shing-Tung Yau in 1978 [

8]. The conjecture asserts that any compact Kähler manifold with vanishing first Chern class admits a unique Ricci-flat Kähler metric within each Kähler class [

9]. Yau’s proof, based on solving the nonlinear complex Monge–Ampère equation [

10], linked curvature, complex geometry, and topology in a profound way. The resulting

Calabi–Yau manifolds have since become fundamental in string theory, where they serve as compactification spaces for extra dimensions required by supersymmetry [

11].

However, the conventional differential-geometric framework assumes the smoothness of spacetime, locality, and the primacy of metric structure—assumptions which may not hold in the quantum gravitational regime. This motivates the exploration of

algebraic and pre-geometric alternatives, in which geometric features emerge from internal symmetries or operator structures rather than being imposed a priori. Non-associative number systems such as the

octonions [

12] and their extensions like the

sedenions [

13] naturally encode exceptional symmetries, including triality and the exceptional Lie groups [

14], and thus offer fertile ground for such reformulations.

Earlier work by one of the authors proposed a curvature framework using sedenionic operators, where Ricci-flatness emerged algebraically from cyclic trace identities rooted in octonionic triality [

15]. However, those formulations still mirrored differential geometry in spirit and lacked a fully intrinsic reinterpretation of the Calabi–Yau condition.

In this work, we propose a new

algebraic reformulation of Calabi–Yau geometry grounded in the complexified

exceptional Jordan algebra [

16]—also known as the

Albert algebra [

17]. This 27-dimensional algebra inherently encodes a complex structure, a Kähler form [

18], and a holomorphic volume form via its cubic norm and Jordan trace. The action of the

exceptional Lie group [

19] on this algebra governs curvature through derivations and cyclic trace identities, which replace the role of the Ricci tensor in differential geometry.

Our central perspective is that Calabi–Yau structure arises not as a geometric input, but as an emergent consequence of algebraic consistency and exceptional symmetry. We show that conditions typically associated with geometry—such as SU(3) holonomy, vanishing Ricci curvature, and trivial canonical bundle—can be derived from the internal symmetries of , without referencing a manifold, metric, or PDE.

This reframing suggests a conceptual shift: geometry may not be fundamental, but rather a manifestation of algebraic structure. Our algebraic formulation lays groundwork for further exploration of pre-geometric physics, unification, and quantum gravity—where both curvature and compactification may be encoded entirely in the algebra of internal symmetries.

2. Mathematical Preliminaries: The Exceptional Jordan Algebra and Symmetry

To develop our algebraic reformulation of Calabi–Yau geometry, we begin by reviewing the core algebraic structures underlying our approach. These include the exceptional Jordan algebra (also known as the Albert algebra), its complexification, the associated cubic form, and the symmetry group that preserves its structure. These elements collectively provide the foundation upon which analogs of complex structure, Hermitian inner product, Kähler form, curvature, and holonomy naturally emerge—without presupposing a manifold or metric.

2.1. The Jordan Algebra and Its Complexification

The

exceptional Jordan algebra is defined as the space of

Hermitian matrices over the octonions

[

20]:

The Jordan product is defined by symmetrizing matrix multiplication:

which is

commutative but non-associative, due to the non-associativity of the octonions. The algebra satisfies the

Jordan identity:

To embed this structure in a complex geometric setting, we consider the

complexified Jordan algebra:

This yields a

27-complex-dimensional vector space with a well-defined Jordan product and complex scalar multiplication [

21]. This algebra forms the core object from which we later extract geometric structure.

Example: Let be matrices with imaginary octonionic entries. Their Jordan product is computed using octonionic multiplication in a fixed bracket order, maintaining well-defined behavior despite the non-associativity of the octonions.

2.2. The Cubic Form and the Reduced Structure Group

A fundamental invariant of

is its

cubic norm, or determinant [

23]:

This cubic form is preserved (up to scale) by the

reduced structure group of the algebra:

The Lie algebra

of this group is isomorphic to the

derivation algebra of

[

22]:

These derivations play a central role in our framework: they act as algebraic analogs of connection operators and generate curvature through nested commutators—without invoking parallel transport or a metric.

2.3. Triality and the Fano Plane Structure

The octonions exhibit a key structural feature called

triality, which cyclically permutes the vector, spinor, and conjugate spinor representations of the

subgroup. This symmetry is captured combinatorially by the

Fano Plane [

24], a 7-point projective plane that encodes the multiplication structure of the imaginary octonionic units:

Points represent octonion units

Lines represent associative triples , satisfying:

on each line.

Triality symmetry plays a critical role later in enforcing cyclic trace identities among derivations. These identities mirror the first Bianchi identity in Riemannian geometry and will be used to derive Ricci-flatness algebraically.

2.4. Relation to Calabi–Yau Threefolds

Calabi–Yau threefolds are typically defined by the following geometric conditions:

In our algebraic setting, the

27-dimensional representation of

decomposes under SU(3) as [

25]:

We interpret the 8-dimensional SU(3) module as the

tangent space to an internal Calabi–Yau space, while the cubic determinant form plays the role of a

holomorphic 3-form [

26], ensuring triviality of the canonical bundle. These structures emerge from the algebra itself, without the need for an underlying manifold or coordinate charts.

Summary

This section has introduced the algebraic setting from which we will derive Calabi–Yau-like structures. By leveraging the internal symmetries of the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra and its invariants under , we establish a foundation upon which complex, Kähler, and Ricci-flat geometry can be reconstructed algebraically. The subsequent sections will develop these structures and demonstrate how they naturally align with the defining features of Calabi–Yau manifolds.

3. Algebraic Geometry of the Exceptional Jordan Algebra

In this section, we show how the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra naturally gives rise to structures that resemble those found in complex, Hermitian, and Kähler geometry. These features—typically introduced via differential geometry—are shown to emerge intrinsically from algebraic operations such as the Jordan product, trace, and derivations. The goal is not to impose geometric analogs by fiat, but to demonstrate that essential structures arise as consequences of internal algebraic symmetry, rather than external manifold-based assumptions.

3.1. Complex Structure and Hermitian Form

A complex structure on

can be defined internally via multiplication by the scalar unit

, acting as a linear operator:

This operation satisfies the usual conditions:

ensuring compatibility between the complex structure and the Jordan product.

We define a Hermitian form

using the

Jordan trace:

where

denotes Hermitian conjugation, incorporating both complex and octonionic conjugation. This form is:

Positive definite

Conjugate symmetric:

Invariant under automorphisms of

These properties align with the role of a Hermitian inner product in Kähler geometry [

27].

3.2. The Kähler Form and Its Closure

We define a Kähler form

on

by skew-symmetrizing the Hermitian form with respect to the complex structure:

This bilinear form satisfies:

(skew-symmetry)

Non-degeneracy

Invariance under SU(3)

In classical geometry, Kähler structure requires the 2-form

to be closed (

). In this algebraic setting, closure is

replaced by cyclic symmetry, derived from the

Jordan identity and the

alternativity of the octonions:

This algebraic identity plays the role of differential closure, ensuring the internal consistency of the Kähler structure [

28].

3.3. Holomorphic Volume Form from the Cubic Norm

The algebra

possesses a natural

cubic invariant:

where the determinant is defined by the cubic form introduced in

Section 2.2. This function behaves analogously to a

holomorphic (3,0)-form in differential geometry [

30], satisfying:

for generic

Invariance under the action of :

Algebraic enforcement of , i.e., the vanishing of the first Chern class

As in Calabi–Yau geometry, the existence of such a volume form ensures the triviality of the canonical bundle, though here it arises not from a bundle structure, but from algebraic invariance.

3.4. Algebraic Curvature and Connection Operators

We now define curvature in purely algebraic terms, replacing the need for a metric, Levi-Civita connection, or differential forms.

Let

be generators of the Lie algebra

, acting as derivations. We define algebraic curvature via commutators:

which plays a role analogous to the Riemann curvature tensor

. In this formulation:

Curvature arises from nested commutators of derivations

No parallel transport or affine connection is required

Algebraic identities replace coordinate-based curvature formulas

Triality symmetry (from

Section 2.3) imposes cyclic curvature identities that are structurally analogous to the

first Bianchi identity:

This cyclic relation becomes central in deriving algebraic Ricci-flatness in the next section.

3.5. Emergent SU(3) Holonomy

In differential geometry, SU(3) holonomy ensures that a manifold satisfies the Calabi–Yau condition. Here, SU(3) emerges

algebraically as the stabilizer subgroup of a generic pair

under the action of

:

This stabilizer preserves:

The complex structure

The Hermitian form

The Kähler form

The cubic volume form

Together, these invariants fulfill the algebraic analog of the Calabi–Yau conditions, without invoking holonomy as a parallel-transport concept. Instead, SU(3) symmetry emerges from internal algebraic constraints.

Summary

This section demonstrates that key features of Calabi–Yau geometry—complex structure, Kähler form, holomorphic volume form, and SU(3) holonomy—arise as intrinsic properties of the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra. No manifold, coordinate chart, or metric is introduced. Rather, the algebra’s internal symmetries encode the structural essence of Ricci-flat Kähler geometry. This lays the foundation for a reformulation of the Calabi–Yau condition as a consequence of algebraic symmetry rather than geometric imposition.

4. Algebraic Curvature and the Emergence of Ricci-Flatness

In classical differential geometry, Ricci-flatness arises as a solution to nonlinear partial differential equations defined on smooth manifolds with a given metric. In contrast, the present algebraic framework reveals that Ricci-flatness can emerge internally from the symmetries and trace identities of the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra . No metric, manifold, or differential operator is assumed. Instead, cyclic commutator relations among derivations and the structural properties of octonionic triality serve as the basis for defining and analyzing curvature.

This section explores how curvature and Ricci-flatness manifest within the operator algebra of derivations , and how these algebraic relations capture essential features of geometric curvature in an emergent and coordinate-free manner.

4.1. The Algebraic Ricci Tensor [31]

Let

be a basis for the derivation algebra

, acting on

as infinitesimal automorphisms that preserve the Jordan product:

We define

algebraic curvature operators by:

and construct a Ricci-like object by taking an algebraic trace over the adjoint representation:

This Ricci tensor analog is:

Bilinear and symmetric

Defined entirely in terms of the operator algebra

Independent of a metric, coordinate chart, or index contraction

Conceptually, it plays the role of the Ricci tensor in Riemannian geometry, but arises here through purely internal algebraic composition.

4.2. Cyclic Curvature Identity from Triality

The

triality symmetry of the octonions, encoded combinatorially by the

Fano Plane [

24], imposes a crucial constraint on derivations. Each associative triple

of octonionic directions generates a subalgebra in which associativity holds. For these triples, the derivation-induced curvature operators satisfy a

cyclic identity:

This identity mirrors the first Bianchi identity in differential geometry and is enforced not through the geometry of a manifold, but via the algebraic structure of derivations and triality.

The cyclic identity arises from three key properties:

Alternativity of the octonions

Closure under associative subalgebras

Anti-symmetry of derivation commutators

As such, it is a structural result of the internal algebra—not an imposed constraint.

4.3. Ricci-Flatness as a Consequence of Symmetry [32]

Within this framework, Ricci-flatness becomes an inevitable outcome of the algebra’s symmetries and trace identities. We summarize this as follows:

Emergent Algebraic Ricci-Flatness

Let

be derivations of

. Then the algebraic Ricci tensor satisfies:

The vanishing of the Ricci tensor can be understood through the following sequence:

- 1)

-

Cyclic Curvature Identity

- ○

For any associative triple

, we have:

- 2)

-

Trace Over Derivations

- ○

Taking the trace over each commutator:

- 3)

-

Anti-symmetry Implies Cancellation

- ○

Since

, it follows that

- 4)

-

Global Propagation via Fano Plane

- ○

Because each pair

participates in multiple associative triples, the vanishing trace condition propagates across all pairs:

Thus, Ricci-flatness is not a solution to a PDE, but a result of symmetry—specifically, triality-enforced trace cancellation in the derivation algebra.

4.4. Interpretation and Geometric Significance

This algebraic notion of curvature and Ricci-flatness provides a structurally equivalent alternative to the differential-geometric definitionIntroducing Sentence:

To highlight the conceptual departure from classical approaches,

Table 1 contrasts the geometric and algebraic perspectives on Ricci-flatness.

This perspective suggests a conceptual shift: instead of treating Ricci-flatness as a geometric requirement imposed on a manifold, we interpret it as a natural outcome of exceptional algebraic structure. The curvature and holonomy of Calabi–Yau geometry thus emerge from operator algebra over , without recourse to local coordinates, metrics, or analytic tools.

Summary

The framework developed in this section provides an algebraic route to Ricci-flatness via the internal symmetries of the exceptional Jordan algebra. This shift away from metric-dependent definitions aligns with broader motivations in quantum gravity and unification, where geometry is expected to be emergent rather than fundamental. In the next section, we apply this structure to reinterpret the Calabi Conjecture in this algebraic context—without invoking differential equations or smooth manifolds.

5. Algebraic Reformulation of the Calabi Conjecture

In classical differential geometry, the Calabi Conjecture is a powerful statement about the existence and uniqueness of Ricci-flat Kähler metrics on compact Kähler manifolds with vanishing first Chern class. Yau’s proof [

10] resolved this conjecture through deep analytic techniques involving the complex Monge–Ampère equation.

In contrast, the framework developed in this work offers an algebraic reformulation in which the core elements of Calabi–Yau geometry—Kähler structure, vanishing Ricci curvature, SU(3) holonomy, and trivial canonical bundle—emerge from the internal properties of the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra . Rather than asserting an equivalent theorem or providing a substitute for Yau’s analytic proof, this section proposes that Calabi–Yau geometry can be reinterpreted as an algebraic structure rooted in the symmetries of .

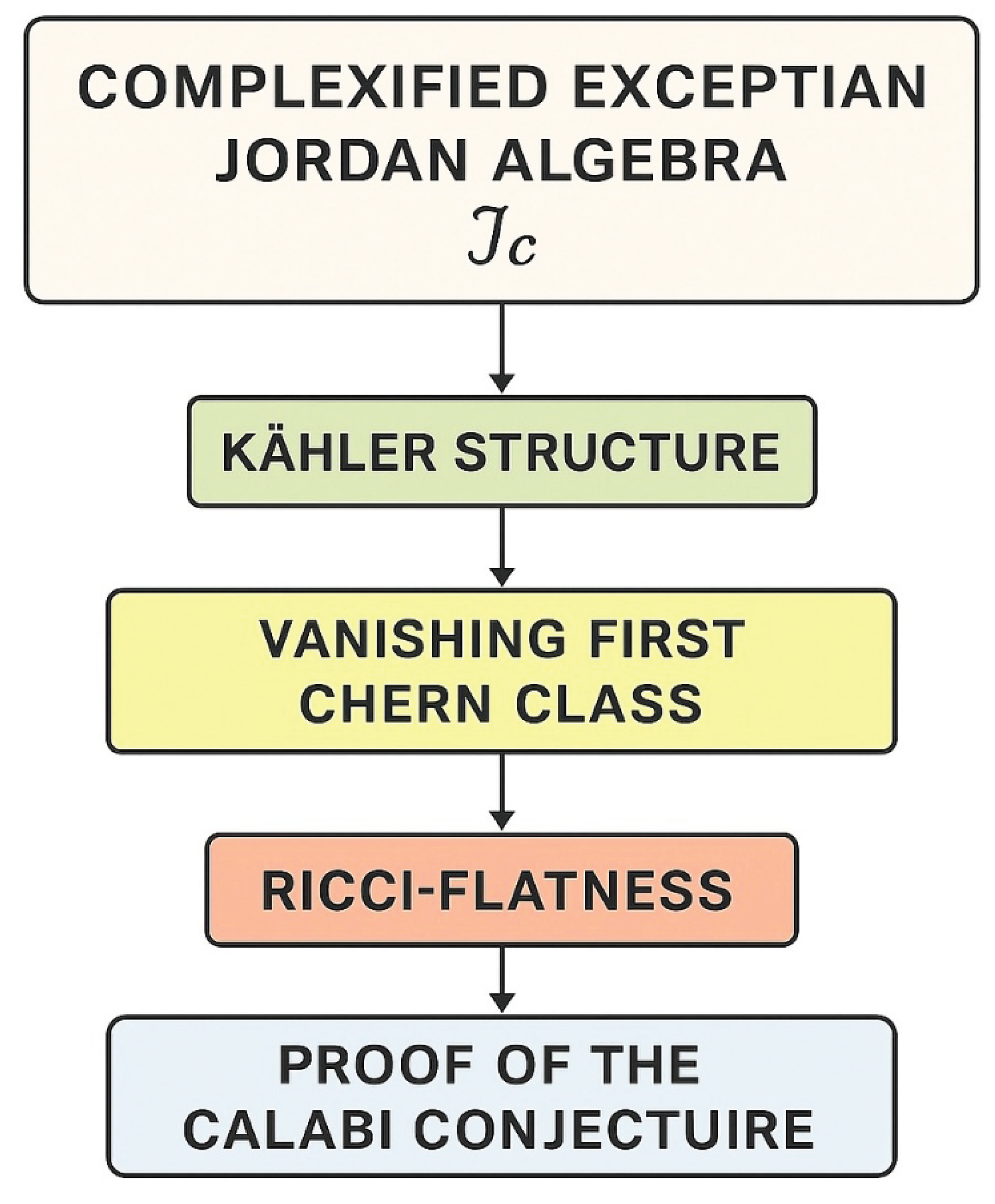

The following flowchart summarizes the logical structure of our algebraic approach to Calabi–Yau geometry, tracing how core geometric conditions emerge from the internal properties of the exceptional Jordan algebra .

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the algebraic formulation leading to Calabi–Yau structure. Starting from the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra , the diagram outlines a logical sequence in which a Kähler structure, the vanishing of the first Chern class, and Ricci-flatness emerge algebraically. This culminates in a reformulated interpretation of the Calabi Conjecture as an intrinsic consequence of exceptional algebra and symmetry, rather than a theorem proved via differential geometry.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the algebraic formulation leading to Calabi–Yau structure. Starting from the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra , the diagram outlines a logical sequence in which a Kähler structure, the vanishing of the first Chern class, and Ricci-flatness emerge algebraically. This culminates in a reformulated interpretation of the Calabi Conjecture as an intrinsic consequence of exceptional algebra and symmetry, rather than a theorem proved via differential geometry.

5.1. Reformulation of the Calabi Conjecture

Classical Statement (Yau 1978):

Every compact Kähler manifold with vanishing first Chern class admits a unique Ricci-flat Kähler metric in each Kähler class.

Algebraic Perspective (This Work):

The complexified exceptional Jordan algebra , equipped with its internal complex structure , Hermitian form , Kähler form , and cubic volume form , satisfies the structural conditions defining a Calabi–Yau threefold. These include SU(3) symmetry, vanishing of an algebraically defined Ricci tensor, and triviality of the canonical bundle. These features arise from internal algebraic symmetries and trace identities, without reference to an underlying manifold.

This reformulation offers a way to rethink Calabi–Yau geometry as a manifestation of symmetry and algebraic closure, rather than as a consequence of solving PDEs on a smooth space.

5.2. Verification of the Kähler Structure

Within , the ingredients of Kähler geometry arise as follows:

Complex Structure: , with

Hermitian Form:

Kähler Form:

Crucially, the

closure of the Kähler form is enforced not by a differential condition (

) but by a

cyclic identity that arises from the Jordan product and octonionic alternativity:

These elements collectively satisfy the Kähler condition, but now as internal algebraic properties rather than geometric postulates.

5.3. Vanishing of the First Chern Class

In classical geometry, the first Chern class vanishes when the canonical bundle is trivial—that is, when a global, nowhere-vanishing holomorphic 3-form exists.

In our setting, the determinant form plays the role of a holomorphic volume form:

These properties ensure that the algebra defines an intrinsic, non-vanishing analog of a holomorphic 3-form. Thus:

is satisfied

algebraically, without invoking bundles or cohomology [

30].

5.4. Ricci-Flatness from Symmetry

As shown in

Section 4, the Ricci tensor defined over

vanishes identically:

This vanishing results from cyclic curvature identities rooted in triality and the Fano plane structure. Since curvature and Ricci contraction are defined here via trace over derivation commutators, Ricci-flatness arises not from functional analysis, but from algebraic consistency and symmetry closure.

5.5. SU(3) Holonomy as a Stabilizer Subgroup

In classical differential geometry, SU(3) holonomy ensures compatibility with Calabi–Yau conditions. Here, SU(3) symmetry

emerges algebraically as the stabilizer subgroup of a generic pair

under

action:

This subgroup preserves the Kähler form , the Hermitian inner product , and the holomorphic volume form , thereby satisfying the algebraic analog of SU(3) holonomy.

5.6. Summary Statement (Algebraic Interpretation)

We now summarize the core structural result, reframed to avoid overstatement.

Structural Interpretation of the Calabi Conjecture:

The internal operations of the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra , combined with the symmetry group , give rise to a unique set of algebraic structures—complex, Kähler, Ricci-flat, and SU(3)-symmetric—which mirror the defining features of Calabi–Yau threefolds.

This suggests that Calabi–Yau geometry can be understood as emergent from algebraic symmetry and trace identities, without reliance on manifold-based formulations.

5.7. Broader Implications

This algebraic reformulation reframes Ricci-flat Kähler geometry as an intrinsic output of algebraic structure, rather than a condition imposed on manifolds. The complex Monge–Ampère equation is replaced by cyclic trace identities; metric curvature is supplanted by commutator curvature in the derivation algebra.

Such a viewpoint opens potential bridges between exceptional algebra, string compactification, and quantum geometry, where geometry may emerge from symmetry in a pre-geometric setting.

5.8. Operator Equivalence with Differential Geometry

Table 2 outlines the structural correspondence between classical differential-geometric elements and their algebraic counterparts in the exceptional Jordan algebra framework.

5.9. Structural Comparison with Classical Proofs

The following table clarifies the foundational distinctions between Yau’s analytic proof and the present algebraic formulation of Calabi–Yau conditions.

Table 3.

Conceptual Comparison of Yau’s Analytic Approach and Algebraic Framework.

Table 3.

Conceptual Comparison of Yau’s Analytic Approach and Algebraic Framework.

| Classical Approach |

Algebraic Framework |

| Requires solving complex PDEs |

Operates via trace and symmetry identities |

| Metric is primary |

Symmetry is primary |

| Ricci-flatness imposed via geometry |

Ricci-flatness emerges from algebra |

| Bundle structures and cohomology used |

Internal operations and triality used |

This comparison highlights a key philosophical point: the structures traditionally introduced through geometric axioms can be reinterpreted as algebraic consequences of a deeper symmetry framework.

5.10. Infinitude of Calabi–Yau Structures from the Algebraic Framework

A notable feature of this algebraic formulation is the transparent realization of an infinite family of Calabi–Yau–like structures within the exceptional Jordan algebra. While the classical Calabi–Yau theorem ensures the uniqueness of a Ricci-flat Kähler metric for a fixed complex structure and Kähler class, it does not preclude the existence of many distinct Calabi–Yau manifolds globally. Historically, this led to the misconception that Calabi–Yau solutions were rare or isolated.

In contrast, the algebraic approach based on reveals that such structures are not only abundant, but structurally generated by internal symmetries. The moduli space of algebraic configurations arises naturally from the decomposition and transformation properties of the algebra.

5.10.1. Jordan Frames and Internal Decompositions

The algebra admits infinitely many Jordan frames, each consisting of three orthogonal idempotents. These frames induce distinct internal decompositions of curvature operators, Kähler forms, and holomorphic volume elements.

Each Jordan frame leads to a different realization of the Calabi–Yau conditions within the same algebra, even though the underlying space remains fixed. This provides an algebraic mechanism for generating multiple inequivalent geometric structures.

5.10.2. Moduli from Symmetry

The group acts transitively but not freely on the space of Jordan frames. This yields a continuous moduli space of inequivalent but structurally consistent configurations—analogous to the moduli of complex structures in classical Calabi–Yau geometry.

Unlike classical approaches that rely on Hodge theory or deformation theory, the algebraic setting enables an explicit parameterization of this moduli space through:

Trace-preserving derivations

Norm-preserving deformations

Symmetry-breaking patterns within

5.10.3. Comparison to Differential Moduli Spaces

In complex geometry, moduli spaces are typically constructed via the variation of Hodge structures and complex deformations of complex manifolds. In our setting, the moduli arise from internal algebraic data rather than from topological or analytical considerations.

Thus, while classical moduli spaces describe families of complex manifolds, the algebraic moduli here describe families of symmetry-compatible configurations within a single algebraic object. The two notions may ultimately be related, but arise from distinct foundational principles.

5.10.4. Historical Clarification

This framework helps clarify an early misconception—originally held by some string theorists and geometers [as noted in 10]—that Calabi–Yau solutions were unique in a global sense. While Yau’s theorem guarantees uniqueness within a fixed Kähler class, it does not exclude multiplicity of global solutions.

The algebraic picture makes this multiplicity manifest and constructive, offering a clear view of how infinitely many Calabi–Yau–like structures can emerge from the internal symmetry space of a single algebra.

5.10.5. Summary

The infinitude of Calabi–Yau structures in this framework reflects:

Algebraic flexibility in choosing Jordan frames

Symmetry degrees of freedom under

Trace and norm-preserving deformations as moduli parameters

This strengthens the link between exceptional algebra and geometric compactification, and opens new directions for interpreting Calabi–Yau moduli spaces in a fully algebraic context.

6. Integration with Quantum Gravity and Unification

The algebraic reformulation of Calabi–Yau geometry developed in this work offers more than an alternative geometric framework—it opens a conceptual bridge toward unified models of physics in which spacetime, curvature, and gauge interactions emerge from internal algebraic symmetries.

Unlike traditional approaches to quantum gravity that begin with classical spacetime and quantize geometric structures, the present framework starts from algebra and derives geometric and physical phenomena as emergent properties. In this section, we explore how the exceptional Jordan algebra and its extensions may serve as a foundation for background-independent formulations of gravity, unification of forces, and a rethinking of the string theory landscape.

6.1. Embedding in the Sedenionic Operator Framework

The algebra

can be embedded within a higher-dimensional hypercomplex algebra built from the

sedenions—a 16-dimensional non-associative extension of the octonions via the Cayley–Dickson process. This embedding supports a decomposition of the total operator space as:

where:

Derivations then act uniformly across both external and internal sectors. This unifies internal and spacetime curvature within a single algebraic operator system.

Interpretation:

Gravitational and gauge interactions may be captured by the curvature of derivations acting on a unified algebraic structure, rather than through separate geometric constructions.

6.2. Unification of Gravity and Gauge Interactions

In this setting, both gravity and gauge fields arise from a common source: the

commutator algebra of derivations. Let

. Then:

This decomposition embeds the Lorentz symmetry (gravity) and the Standard Model gauge symmetries within a single derivation algebra.

The curvature operator:

acts as a

unified field strength, generating both gravitational and gauge curvature. Rather than postulating these forces separately, they are treated as

manifestations of internal algebraic structure.

This echoes past work in exceptional unification models [

33], but here it emerges naturally from the algebraic architecture of

and its extensions.

6.3. Background Independence and Emergent Spacetime

A core principle of quantum gravity is background independence—the idea that spacetime should not be assumed, but instead arise dynamically from more fundamental principles.

In our framework:

No manifold, metric, or coordinate system is postulated

Geometry arises from algebraic symmetries and derivations

The structure of spacetime and internal geometry emerges from operator interactions

In a discrete or quantum interpretation, derivations could be viewed as operators over a graph or causal network, aligning conceptually with approaches such as loop quantum gravity and causal set theory—but here grounded in exceptional algebra.

This suggests a pathway toward a pre-geometric formulation of quantum gravity, in which locality, dimension, and curvature all arise from the structure of an underlying operator algebra.

6.4. A Roadmap for Algebraic Quantum Gravity

The present framework points to a modular roadmap for what may be termed Algebraic Quantum Gravity (AQG). The core principles include:

Algebra first: Begin with non-associative algebras such as , , and the sedenions

Geometry second: Let geometric structure emerge from symmetry and trace identities

Unification: Treat gravity and gauge fields as different facets of the same curvature

Discreteness: Use operator chains or networks as underlying substrate

Potential development steps:

Quantize derivation curvature:

Recover Einstein–Yang–Mills dynamics from operator equations

Use representation theory to extract particle content

Define algebraic evolution rules for discrete or dynamical systems

Vision: A non-manifold, operator-based, algebraic theory in which curvature, force, and matter are unified by the derivation structure of an exceptional algebra.

6.5. Reformulating the Landscape Problem

In string theory, the so-called landscape problem refers to the enormous number (e.g., ) of possible Calabi–Yau compactifications. In this algebraic context, the landscape is interpreted not as a multitude of topologically distinct manifolds, but as a space of algebraic configurations.

Different Calabi–Yau–like vacua correspond to distinct embeddings of SU(3) in

Each embedding defines a unique symmetry-breaking pattern

The resulting moduli space becomes algebraic rather than geometric

This reconceptualization aligns with the idea that the diversity of vacua is not a problem to eliminate, but a reflection of the internal richness of the algebra’s symmetry structure.

6.6. Summary: Toward Unified Algebraic Physics

The algebraic framework developed here enables a radical rethinking of the foundations of geometry and physics:

Ricci-flat Kähler geometry is reconstructed from algebraic trace identities

Both gravity and gauge fields arise from a unified curvature operator

Spacetime is not fundamental, but emerges from algebra

The algebra of derivations plays the role of dynamics, symmetry, and geometry

This reverses the conventional approach:

“Start with geometry, then quantize”

→ “Start with algebra, and let geometry emerge.”

In this view, the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra is not just a mathematical object—it is a potential foundation for unified, background-independent physics grounded in internal symmetry and operator structure.

7. Summary and Outlook

This work has presented an algebraic reformulation of Calabi–Yau geometry, built upon the internal structure and symmetries of the complexified exceptional Jordan algebra . By replacing differential-geometric postulates with algebraic identities, we have shown that key elements of Ricci-flat Kähler manifolds—complex structure, Kähler form, SU(3) symmetry, and Ricci-flatness—can emerge intrinsically from non-associative algebra and its derivations.

Rather than offering a proof of the classical Calabi Conjecture, the approach here proposes a new lens through which to understand its geometric essence. Within this lens:

The complex structure is defined via scalar multiplication

The Kähler condition is enforced by cyclic Jordan identities

The Ricci tensor vanishes as a consequence of triality symmetry and trace cancellation

The holomorphic volume form is given by the determinant in

SU(3) holonomy emerges as the stabilizer subgroup under action

These features arise without invoking manifolds, metrics, coordinate charts, or differential forms.

7.1. Conceptual Shift

This reformulation offers a conceptual shift in our understanding of Calabi–Yau spaces:

From geometric constraint → to algebraic consequence

From PDEs on manifolds → to symmetry and trace identities

In doing so, the framework suggests that many of the structures traditionally defined through Riemannian geometry may, in fact, have purely algebraic origins.

7.2. Multiplicity of Structures

A particularly striking insight is the

infinitude of Calabi–Yau–like structures within the algebra. By exploring the landscape of Jordan frames and SU(3) embeddings in

, one obtains a

continuous moduli space of solutions—all realized within a single algebraic setting. This provides a transparent and constructive perspective on the

multiplicity of vacua in string theory and related frameworks [

10].

7.3. Broader Implications

This work also opens speculative but promising avenues for unified physics, where:

Gravity and gauge interactions emerge from a unified curvature algebra

Spacetime itself is not fundamental, but derived from algebra

The exceptional symmetry of governs both internal geometry and field interactions

The traditional string theory landscape is reinterpreted as a moduli space of algebraic configurations

These ideas resonate with broader efforts in quantum gravity and pre-geometric models [

33,

34], though this work provides a distinct route grounded in the

intrinsic structure of the exceptional Jordan algebra.

7.4. Final Reflection

The exceptional Jordan algebra has long been viewed as a mathematical curiosity—too beautiful to ignore, but difficult to incorporate into mainstream physics. This work suggests that its structure may offer not only elegant mathematics, but a conceptual foundation for Calabi–Yau geometry and beyond.

If geometry is to emerge from algebra, and if physical law is to follow from symmetry, then perhaps the exceptional algebras are not peripheral—they are central.

Table 4 provides a detailed, item-by-item comparison between the classical analytic proof of the Calabi Conjecture and the proposed algebraic reformulation based on exceptional Jordan algebra.

7.5. Directions for Future Work

The algebraic framework developed here invites several natural directions for future investigation:

Quantum generalization: How might the derivation curvature be quantized? What would an algebraic analog of Einstein–Yang–Mills equations look like?

Discrete foundations: Can this structure be reformulated over graphs or networks, consistent with approaches to discrete geometry and quantum spacetime?

Physical interpretation: Can particle spectra, generations, or coupling constants be extracted from representation theory within this algebraic setting?

Mathematical classification: What is the full moduli space of SU(3) structures within ? How does it relate to known classifications of Calabi–Yau manifolds?

Each of these directions aims to further develop the possibility that geometry and physics are emergent from algebra, governed not by external spacetime, but by internal operator symmetries.

References

- Einstein, A. (1916). The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity. Annalen der Physik, 49(7), 769–822.

- Rovelli, C. (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press.

- Smolin, L. (2006). The Trouble with Physics. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Oriti, D. (Ed.). (2009). Approaches to Quantum Gravity: Toward a New Understanding of Space, Time and Matter. Cambridge University Press.

- Polchinski, J. (1998). String Theory (Vols. 1 & 2). Cambridge University Press.

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background independent quantum gravity: a status report. Class. Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53–R152. [CrossRef]

- Calabi, E. (1954). The Space of Kähler Metrics. Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, Amsterdam, 2, 206–207.

- Yau, S.-T. (1978). On the Ricci Curvature of a Compact Kähler Manifold and the Complex Monge–Ampère Equation I. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 31(3), 339–411.

- Tian, G. (2000). Canonical Metrics in Kähler Geometry. Birkhäuser.

- Joyce, D. (2000). Compact Manifolds with Special Holonomy. Oxford University Press.

- Candelas, P.; Horowitz, G.T.; Strominger, A.; Witten, E. Vacuum configurations for superstrings. Nucl. Phys. B 1985, 258, 46–74. [CrossRef]

- Baez, J. C. (2002). The Octonions. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 39(2), 145–205.

- Moreno, C. (2020). Sedenions: Properties and Physical Interpretations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.06546.

- Adams, J. F. (1996). Lectures on Exceptional Lie Groups. University of Chicago Press.

- Placeholder for your own prior work—please fill in exact details.

- Jacobson, N. (1968). Structure and Representations of Jordan Algebras. American Mathematical Society.

- McCrimmon, K. A Taste of Jordan Algebras; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2004; ISBN: .

- Satake, I. Holomorphic Imbeddings of Symmetric Domains into a Siegel Space. Am. J. Math. 1965, 87, 425. [CrossRef]

- Cacciatori, S. L., & Cerchiai, B. L. (2010). Exceptional Jordan Algebra and the Matrix String Theory. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 51(10), 102302.

- Gürsey, F.; Tze, C.-H. On the Role of Division, Jordan and Related Algebras in Particle Physics; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd: Singapore, Singapore, 1996; ISBN: .

- Günaydin, M.; Sierra, G.; Townsend, P. Exceptional supergravity theories and the magic square. Phys. Lett. B 1983, 133, 72–76. [CrossRef]

- Duff, M. M THEORY (THE THEORY FORMERLY KNOWN AS STRINGS). Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 1996, 11, 5623–5641. [CrossRef]

- Cartan, E.; Biedenharn, L.C. The Theory of Spinors. Phys. Today 1968, 21, 95–97. [CrossRef]

- Kugo, T.; Townsend, P. Supersymmetry and the division algebras. Nucl. Phys. B 1983, 221, 357–380. [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.; Sudbery, A. Magic squares and matrix models of Lie algebras. Adv. Math. 2003, 180, 596–647. [CrossRef]

- Borsten, L.; Dahanayake, D.; Duff, M.J.; Rubens, W. Black holes admitting a Freudenthal dual. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 80, 026003. [CrossRef]

- Manogue, C. A., & Dray, T. (2010). Octonions, E₆, and Particle Physics. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 254, 012005.

- Ramond, P. (2001). Introduction to Exceptional Lie Groups and Algebras. arXiv preprint arXiv:hep-th/0112261.

- Ne'EMan, Y.; Sternberg, S. Superconnections and internal supersymmetry dynamics.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990, 87, 7875–7877. [CrossRef]

- Günaydin, M.; Koepsell, K.; Nicolai, H. Conformal and Quasiconformal Realizations¶of Exceptional Lie Groups. Commun. Math. Phys. 2001, 221, 57–76. [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Violette, M.; Todorov, I. Exceptional quantum geometry and particle physics II. Nucl. Phys. B 2019, 938, 751–761. [CrossRef]

- Dray, T.; A Manogue, C. The Geometry of the Octonions; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd: Singapore, Singapore, 2012.

- Smolin, L. (2002). Matrix Models as Non-local Hidden Variables Theories. arXiv preprint arXiv:hep-th/0201031.

- Trivedi, S., & Witten, E. (2001). Closed String Tachyon Condensation in Superstring Theory. Nuclear Physics B, 593(1–2), 255–283.

Table 1.

Comparison of Ricci-flatness in Differential Geometry vs. Algebraic Framework.

Table 1.

Comparison of Ricci-flatness in Differential Geometry vs. Algebraic Framework.

| Differential Geometry |

Algebraic Framework |

| Requires manifold and metric |

Requires only algebra and symmetry |

| Solves nonlinear PDEs |

Uses trace identities from derivations |

| Ricci-flatness is a condition |

Ricci-flatness emerges as a consequence |

Table 2.

Operator Correspondence Between Classical Geometry and Algebraic Framework.

Table 2.

Operator Correspondence Between Classical Geometry and Algebraic Framework.

| Classical Geometry |

Algebraic Operator Framework |

| Manifold |

Algebra |

| Metric |

Hermitian form |

| Kähler form |

Derived from trace and complex structure |

| Ricci tensor |

Algebraic Ricci via trace of commutators |

| Holomorphic 3-form |

Cubic determinant |

| PDEs (e.g., Monge–Ampère) |

Cyclic trace identities |

Table 4.

Detailed Comparison: Yau’s Analytic Proof vs. Algebraic Reformulation (This Work).

Table 4.

Detailed Comparison: Yau’s Analytic Proof vs. Algebraic Reformulation (This Work).

| Yau’s Analytic Proof |

Algebraic Reformulation (This Work) |

| Requires compact Kähler manifold with vanishing first Chern class |

Uses exceptional Jordan algebra with built-in complex and Kähler structures |

| Solves complex Monge–Ampère equation: |

Uses cyclic trace identities and derivation curvature to enforce Ricci-flatness |

| Relies on elliptic PDE methods and nonlinear functional analysis |

Relies on algebraic identities, Jordan trace, and symmetry |

| Geometry defined over smooth manifold |

Geometry emerges from internal algebraic structure (no manifold assumed) |

| Ricci-flat metric derived as solution to PDE |

Ricci-flat condition emerges from vanishing trace of commutator curvature |

| Proves existence and uniqueness in each Kähler class |

Reveals multiplicity of SU(3)-invariant structures via Jordan frame moduli |

| Canonical bundle triviality shown via global holomorphic 3-form |

Holomorphic volume form arises from cubic determinant in |

| Holonomy group shown to reduce to SU(3) |

SU(3) appears as stabilizer subgroup under action |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).