2.2. Datasets

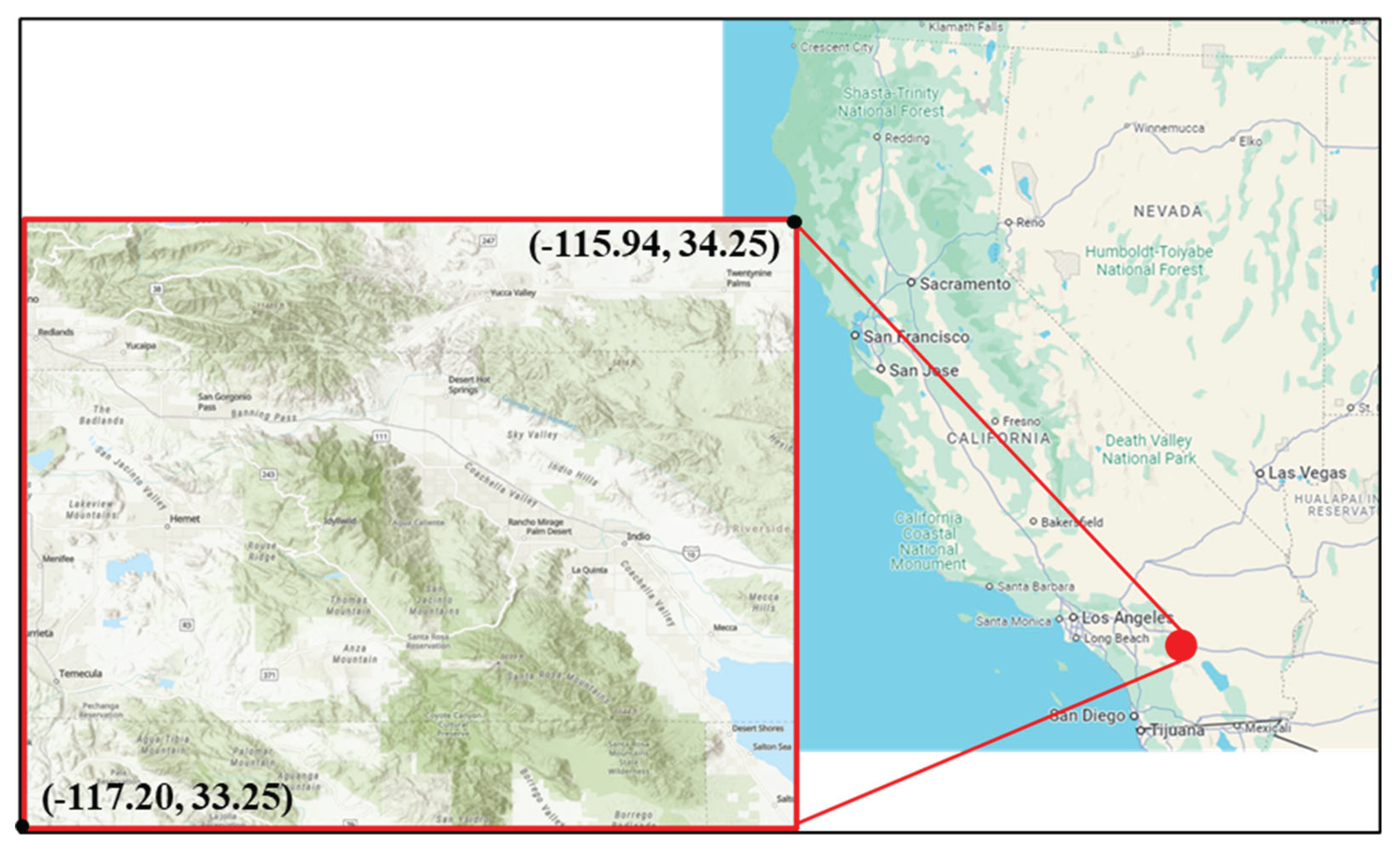

The ground data were collected from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Physical Sciences Laboratory “CPC Global Unified Gauge-Based Analysis of Daily Precipitation” product [

31]. This dataset consists of daily precipitation values obtained from a network of gauges and uses the optimal interpolation objective analysis technique. The spatial resolution is 0.5 degrees latitude by 0.5 degrees longitude. Four gauges were identified within the spatial boundary of this project, one each at (-116.75, 33.75), (-116.25, 33.75), (-116.75, 34.25), and (-116.25, 34.25), longitude and latitude. Daily precipitation values from each gauge were averaged to create the reference dataset.

Four datasets were analyzed against the reference ground data and are described next: ERA5, MERRA2, WLDAS, and IMERG.

The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) atmospheric reanalysis of global climate data is produced by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). The fifth generation ECMWF Reanalysis (ERA5) produces data using 4D-Variational data assimilation and modeling in the ECMWF Integrated Forecast System (IFS) [

32]. This includes data at 137 model pressure levels, which are all interpolated to different pressure, temperature, and vorticity levels [

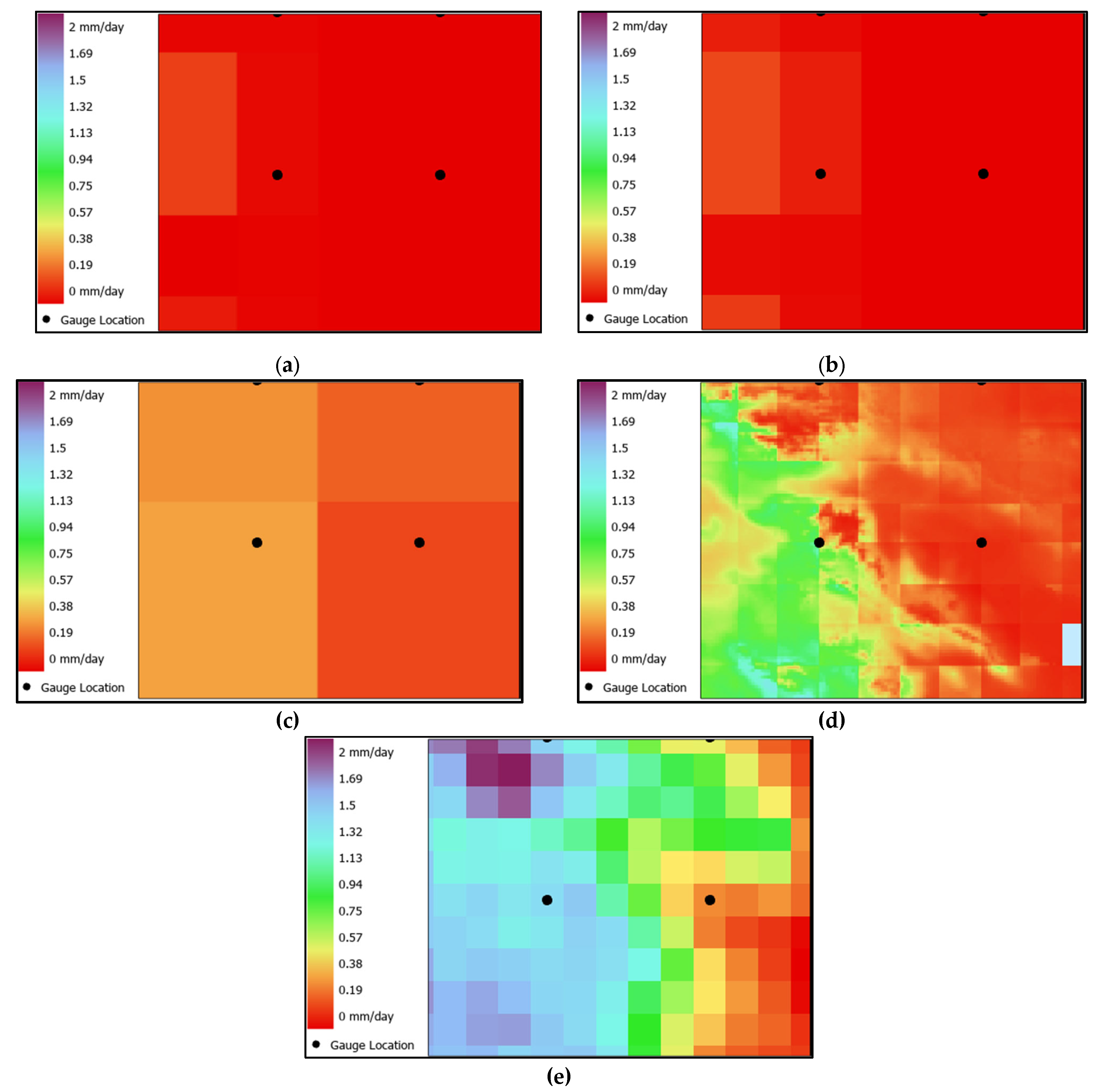

32]. Two variables were analyzed from this dataset: maximum total precipitation rate (MXTPR) and minimum total precipitation rate (MNTPR). For reference in this study, the MXTPR dataset will be noted as ERA5-MAX, and the MNTPR dataset will be noted as ERA5-MIN. The temporal range is January 1, 1940 to present. 20 ERA5 pixels are available across the study area (

Figures 2a and 2b).

The MERRA2, WLDAS, and IMERG datasets were obtained from the NASA Goddard Earth Sciences (GES) Data and Information Services Center (DISC) database.

The Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, version 2, (MERRA2) uses a combination of observations, microwave sounders, and hyperspectral infrared radiance instruments to provide hourly data [

33]. It provides a reanalysis of precipitation data collected from Goddard Earth Observing System Model, Version 5 (GEOS-5) and a data assimilation system [

33]. All fields are computed on a cubed grid, and the precipitation is then either provided on all 72 model layers or interpolated to 42 pressure levels [

33]. This dataset is available from January 9, 1980 to present.

Figure 2c shows the four MERRA2 pixels that cover the study area.

The Western Land Data Assimilation System (WLDAS) utilizes the NASA Land Information System (LIS) and meteorological observations to simulate precipitation. This product is catered to the Western United States, and produces daily high-resolution data [

34]. The available time series is January 6, 1979 through December 31, 2023. There are 12,522 WLDAS pixels across the study area, as shown in the map in

Figure 2d.

The Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) dataset uses the GPM (Global Precipitation Measurement) Core Observatory satellite to combine infrared and microwave sensor readings and precipitation observations from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) and Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite missions [

35]. The dataset used for this project is product version 7 [

16]. IMERG is available from June 5, 2000 to present.

Figure 2e presents a map of average precipitation measured by IMERG during 14 February 2019.

A summary of each product’s characteristics is provided in

Table 1. WLDAS is available at the finest spatial resolution, whereas ERA5 (both -MAX and -MIN), and MERRA2 have the highest temporal resolution.

This study focuses on an almost 20 year-long time series, from June 5, 2000 through December 31, 2019. The time series of precipitation events recorded by each dataset is illustrated in

Figure 3. The standard deviation of each dataset was calculated using the usual Equation 1, as follows:

where

hat is the estimated precipitation value,

µ is the average of the estimated precipitation dataset, and

n is the total number of data points. The standard deviations of ERA5-MAX, ERA5-MIN, MERRA2, WLDAS, IMERG, and the reference ground data are 7.69 mm/day, 5.47 mm/day, 6.05 mm/day, 5.85 mm/day, 6.36 mm/day, and 5.54 mm/day, respectively. ERA5-MIN and WLDAS have standard deviations that are close to that of the reference dataset, meaning they are able to capture the rainfall variability as measured by the rain gauges.

The peaks observed in the time series correspond to extreme precipitation events, which are clearly identifiable across all datasets. These events exhibit strong temporal alignment, indicating consistent detection of rainfall occurrences across the observational and estimation products. However, discrepancies in peak magnitudes are evident, reflecting systematic biases wherein certain estimation products either overestimate or underestimate the actual precipitation intensities associated with these events.

A more detailed investigation of these discrepancies is conducted through quantitative analyses aimed at characterizing the deviations in reported precipitation across datasets. These analyses facilitate a rigorous evaluation of each product’s performance, enabling identification of the temporal and contextual conditions under which discrepancies are most pronounced. The resulting insights are instrumental in guiding the selection of appropriate estimation products for application in arid and semi-arid regions, with consideration given to both accuracy and reliability under varying climatic conditions.

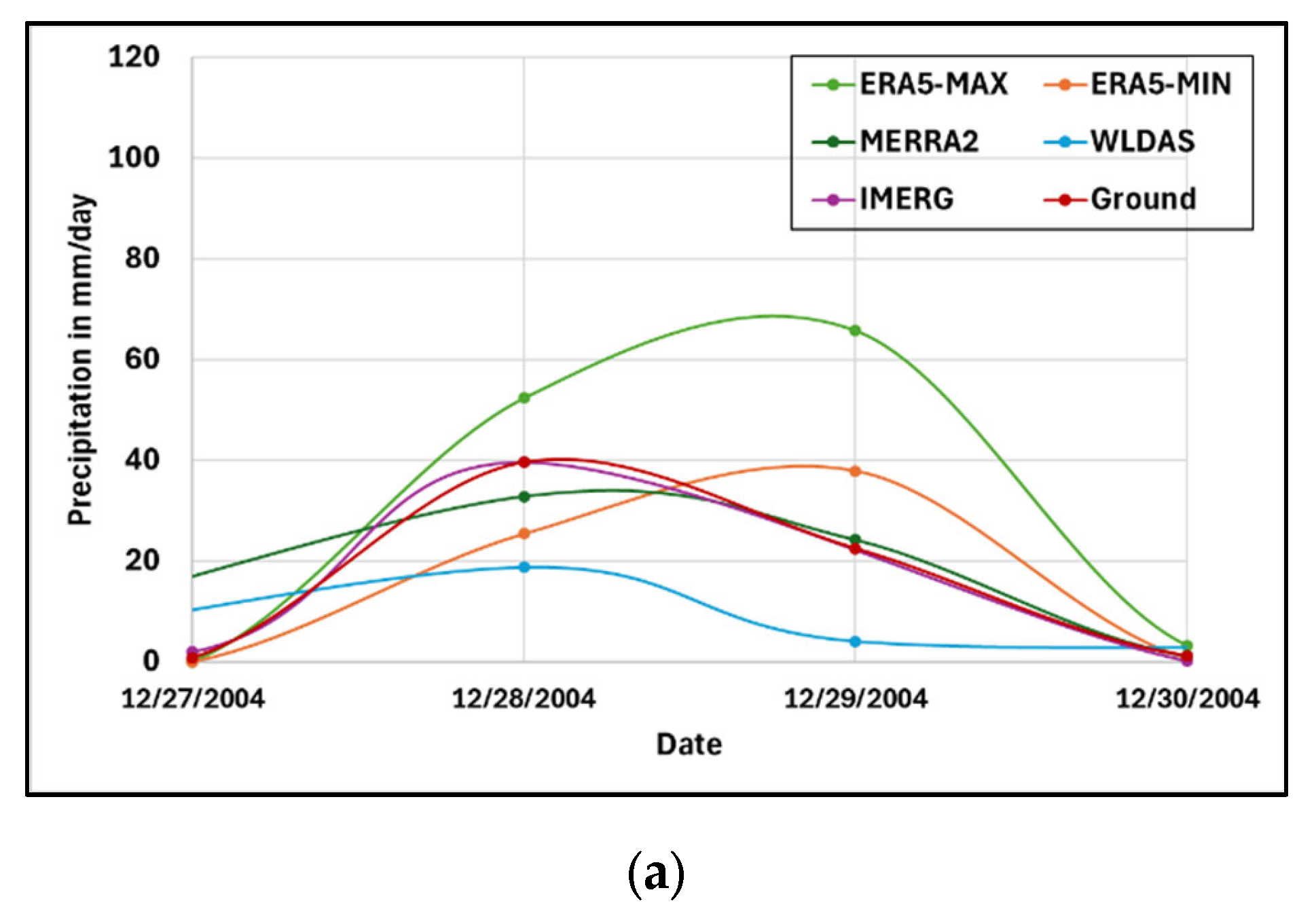

An initial step in diagnosing the discrepancies among estimation products involved isolating extreme precipitation events within the time series and studying their evolution in time. Figure 7 shows time series for three specific events: December 29, 2004, January 21, 2010, and February 14, 2019.

In the first event (

Figure 4a), the rain gauges reported the rainfall event starting on December 28, 2004, continuing to the next day at a lower rate, and having concluded by December 30, 2004. IMERG, MERRA2, and WLDAS capture the event timing, although WLDAS underestimates the amount of rainfall on both days of the event. ERA5-MAX and ERA5-MIN show a delay in the event detection, with the peak occurring on the second day rather than the first. ERA5-MAX overestimates the precipitation rate, whereas ERA5-MIN appears to report values much closer to the reference rainfall. In summary, if IMERG, MERRA2, and WLDAS are better at estimating the timing of this event, IMERG, MERRA2, and ERA5-MIN are better at estimating its peak magnitude.

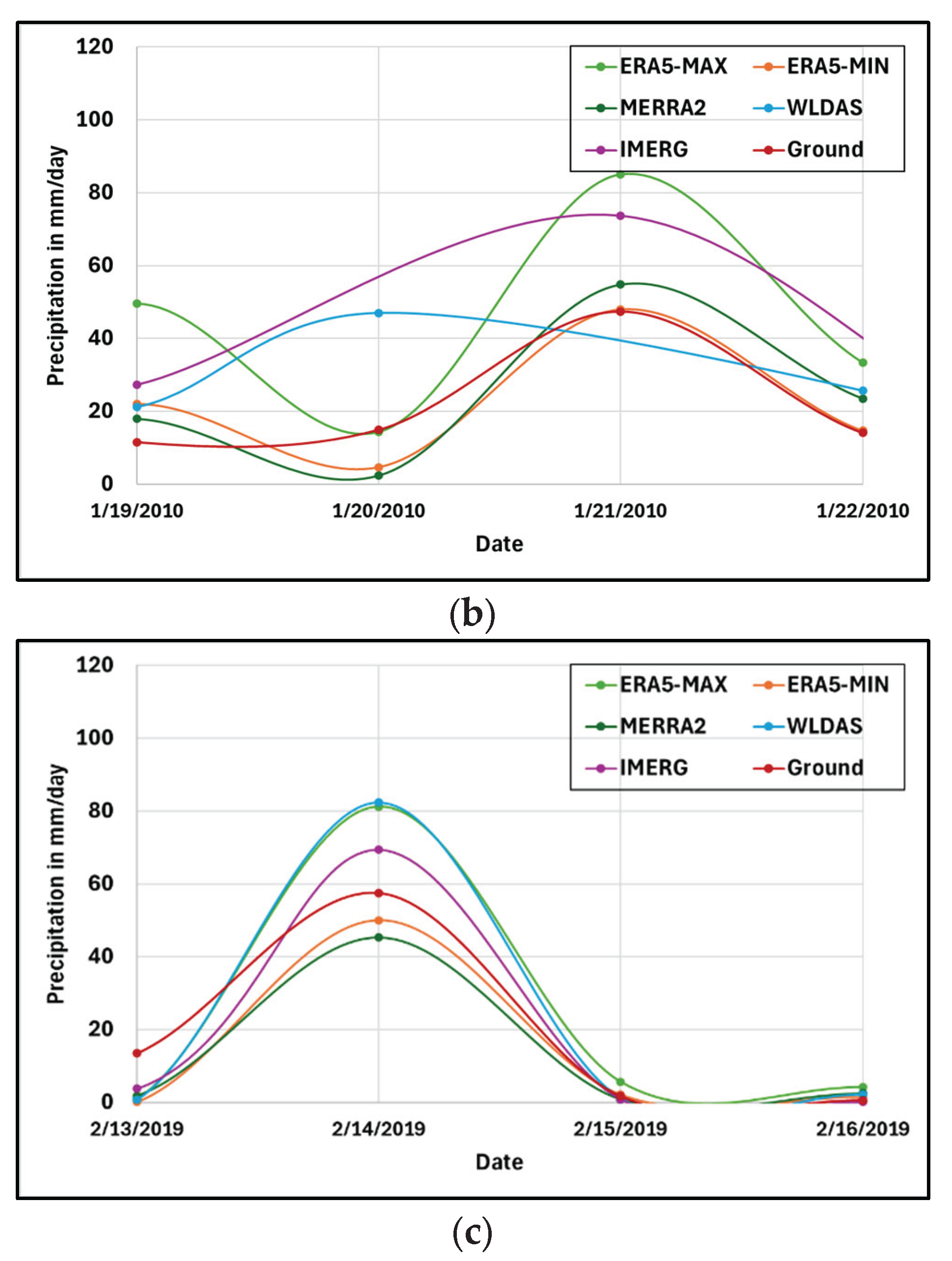

The peak of the second event (

Figure 4b) occurred on January 21, 2010 (as detected by the in-situ stations), with the storm overall lasting the course of many days building up to the peak and slowly ramping down after. For this event, the timing across all products seemed more in accordance with the reference dataset, except for WLDAS that anticipates the peak of the precipitation event to the previous day. The estimated magnitude, however, was most precise amongst WLDAS, MERRA2, and ERA5-MIN, while IMERG and ERA5-MAX overestimated the rainfall rate. ERA5-MAX, ERA5-MIN, MERRA2, and IMERG were therefore better at estimating the timing of the event peak, while ERA5-MIN, MERRA2, and WLDAS were better at estimating its magnitude.

Finally, the third event (

Figure 4c) seems to have perfect timing across all estimation products with a peak on February 14, 2019. However, the magnitude of such peak varies across datasets. Specifically, ERA5-MIN and MERRA2 underestimated the peak magnitude, while ERA5-MAX, WLDAS, and IMERG overestimated it.

Across all three events (

Figure 4), IMERG and MERRA2 consistently correctly reported the timing of precipitation, and ERA5-MIN and MERRA2 consistently reported similar magnitudes of precipitation to the reference. This could indicate a good performance of MERRA2 relative to other re-analysis and satellite-based products at both estimating the timing and magnitude of extreme events across the study area, although further investigation is required.

2.3. Data Analysis

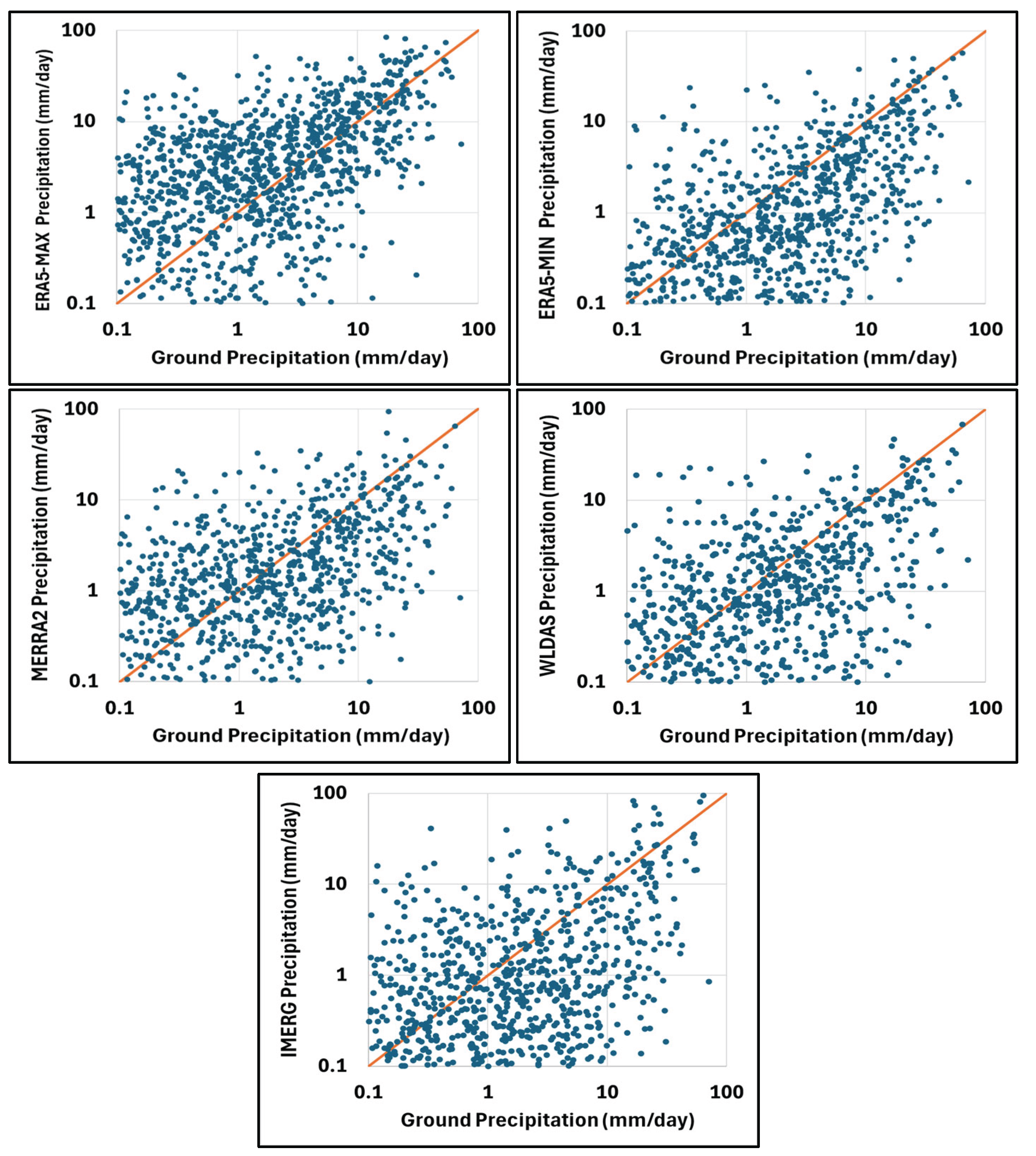

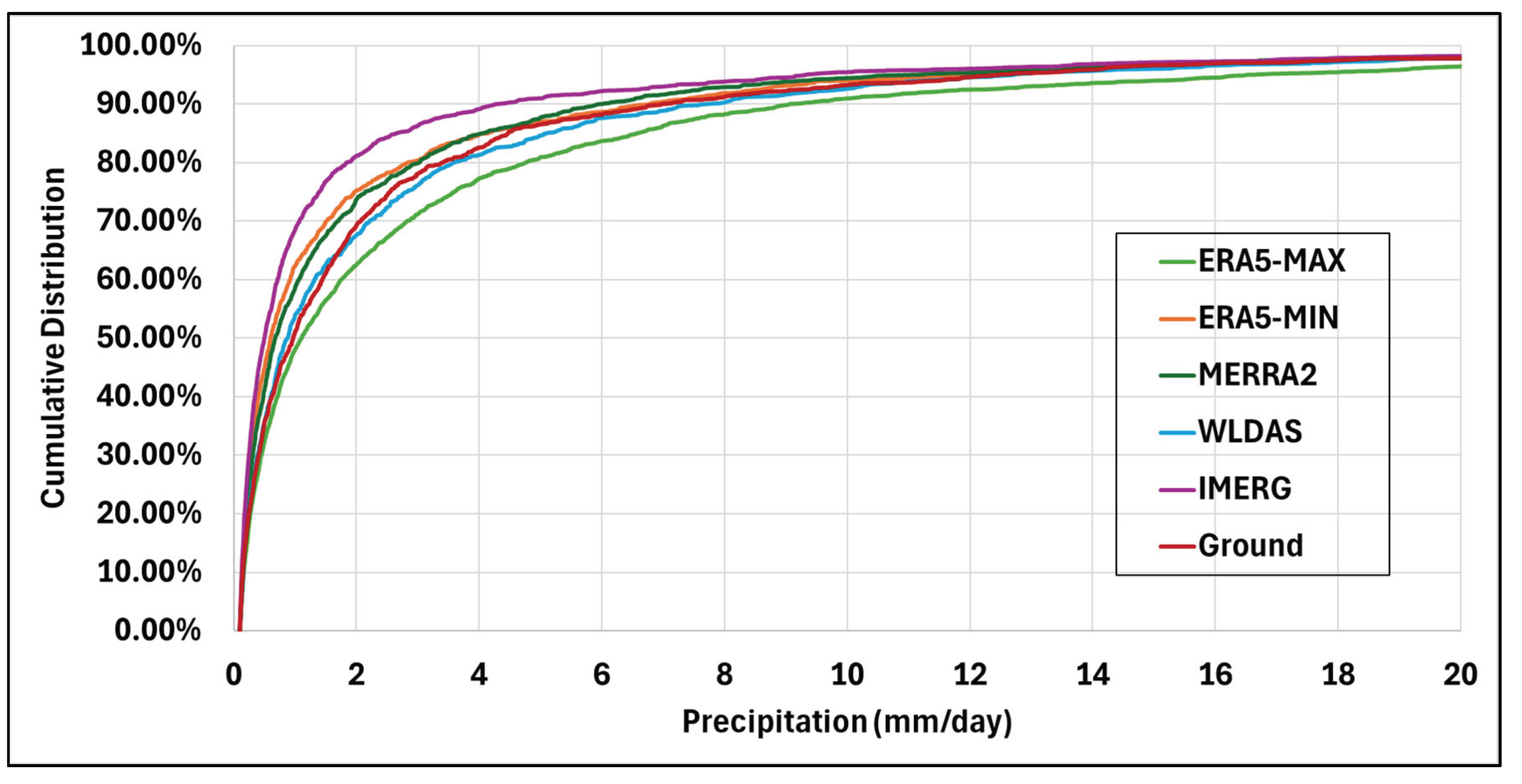

The first set of analyses to assess the performance of the four precipitation products in Palm Desert is based on scatterplots and cumulative distribution functions (CDFs).

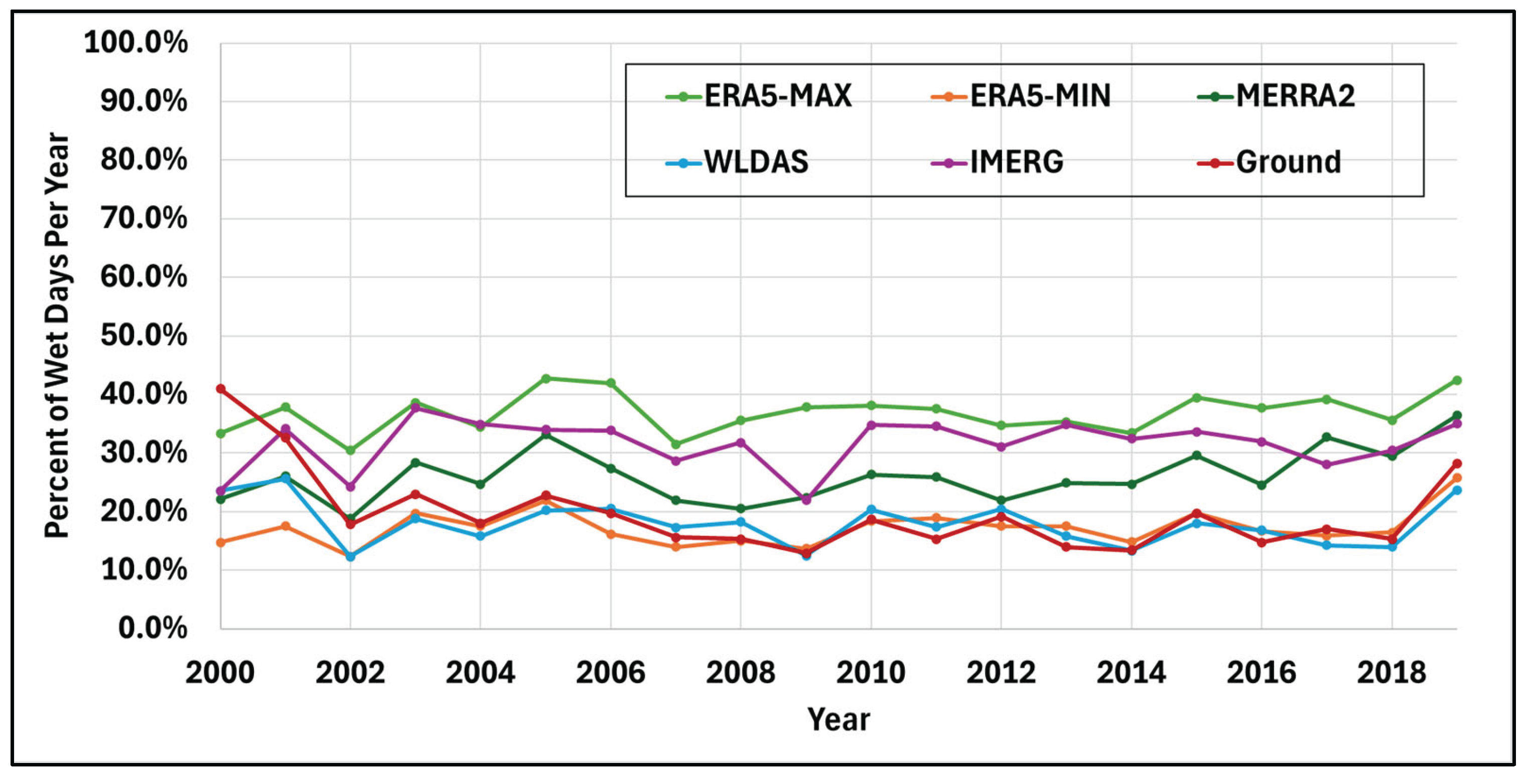

The percentage of days with no precipitation (dry days) and days with precipitation (wet days) was then investigated for each product. The threshold for wet days included any precipitation detected over 0.1 mm/day.

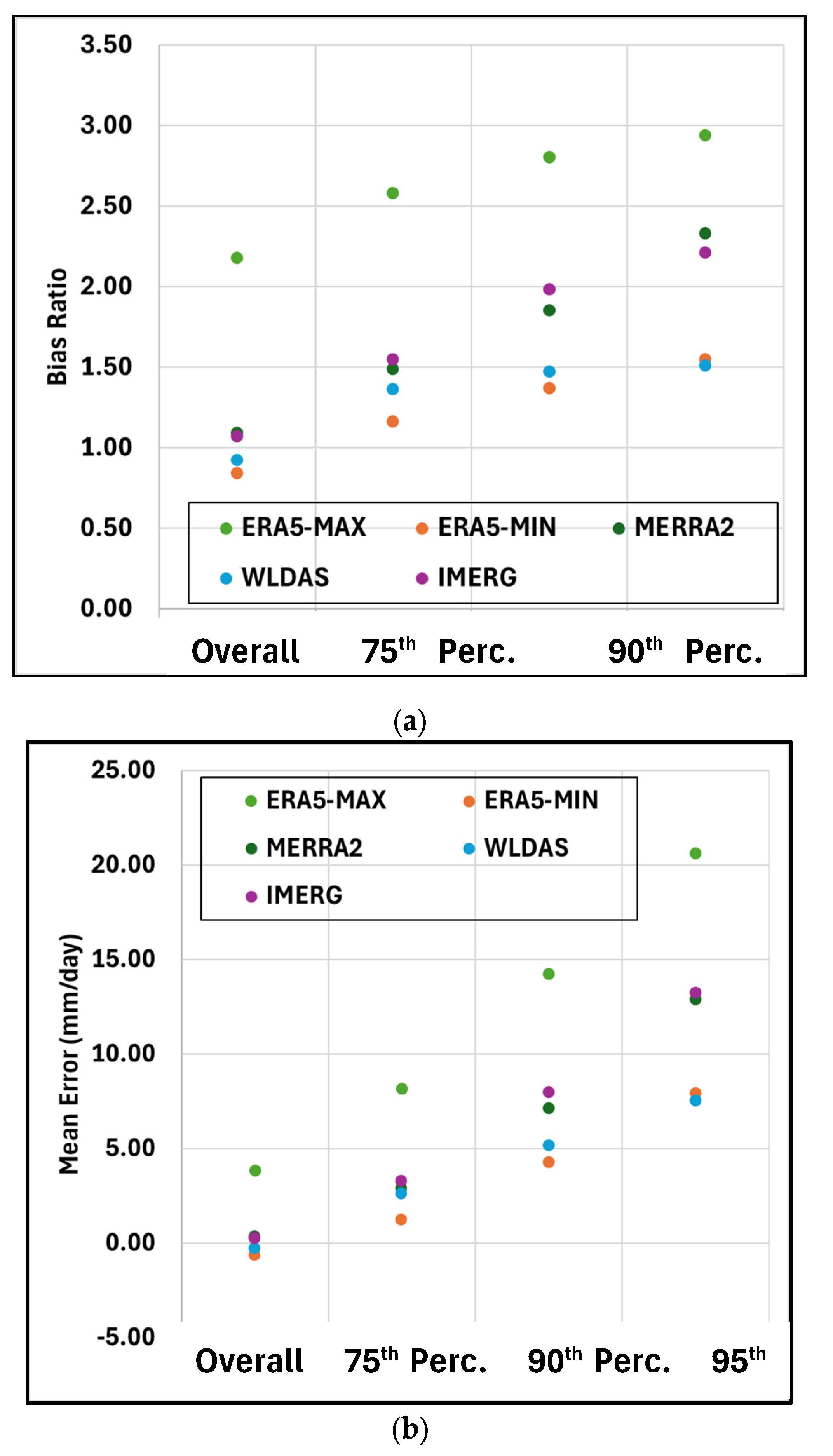

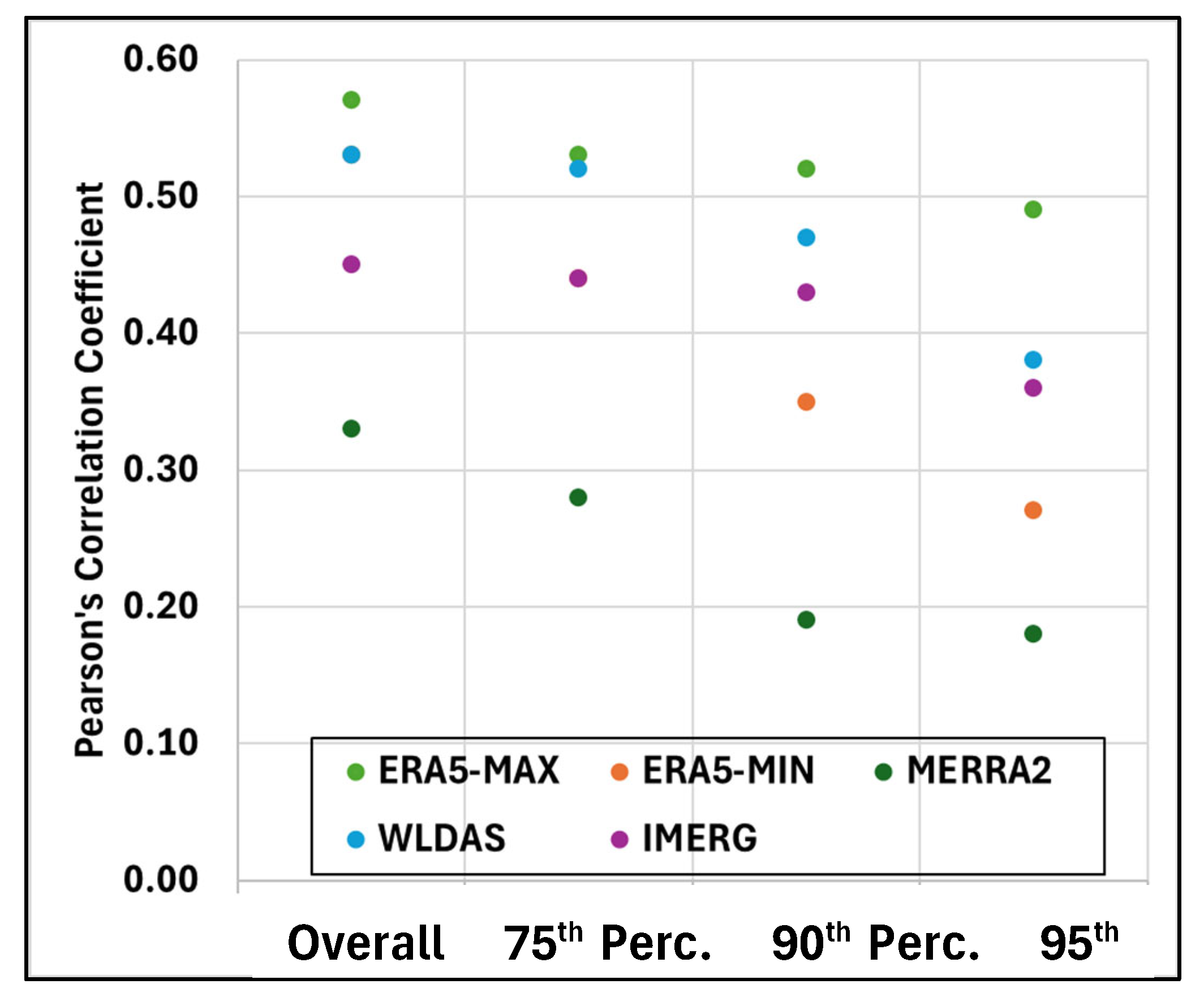

Next, three common statistical metrics were used to further investigate the products’ performance: bias ratio, mean error, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient [

36]. The bias ratio compares each evaluation dataset to the reference dataset, as shown in Equation 2. Ideally, there would not be any bias in the datasets, meaning the bias ratio would be one.

where

is the estimated precipitation value,

x is the reference precipitation value, and

n is the total number of data points.

The mean error measures the average difference between two datasets. The closer to zero this metric is, the smaller the difference between the two, as shown in Equation 3.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient looks at the linear association between the datasets. Ideally, the datasets would have a linear relationship, which corresponds to value of 1 for this metric. This coefficient is represented by the variable and the formula is shown in Equation 4:

Contingency tables were then created to calculate the number of hit cases (

H), missed events (

M), false alarms (

F), and correct no precipitation presence (

Z).

H represents the number of times the estimate correctly detected the presence of precipitation [

36].

M refers to times in which precipitation was not detected, but the reference did observe rain.

F represents the number of times the estimate did detect precipitation when in fact it had not rained.

Z refers to the number of times both estimate and reference detected no precipitation.

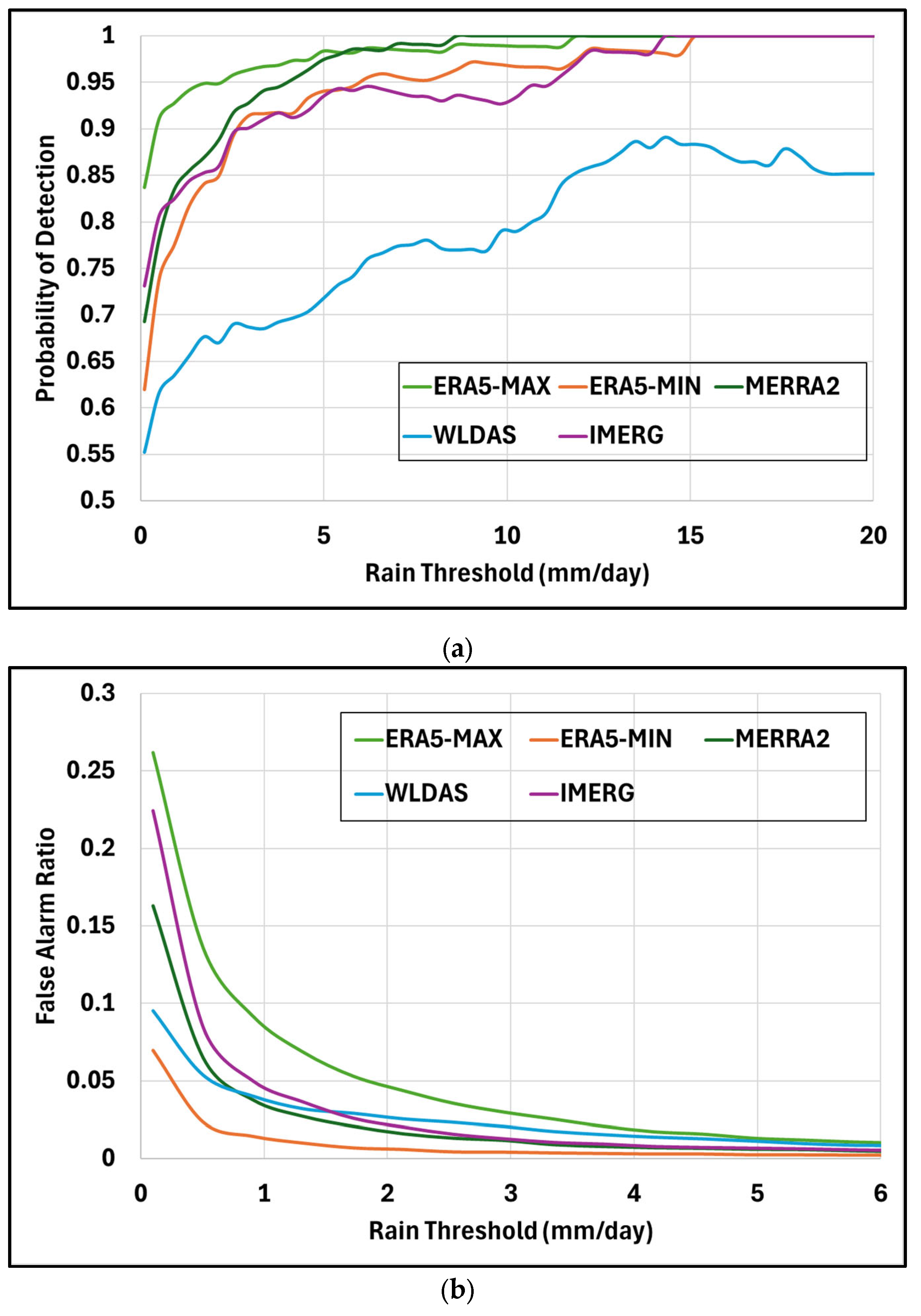

This study used contingency tables to calculate error statistics as a function of precipitation threshold. The probability of detection (POD) measures the likelihood of a product to correctly detect the presence of precipitation by comparing the number of times the evaluation dataset correctly detected precipitation and the number of times it incorrectly detected precipitation:

POD can be computed as a function of a threshold defined based on reference precipitation, as shown in

Table 2 [

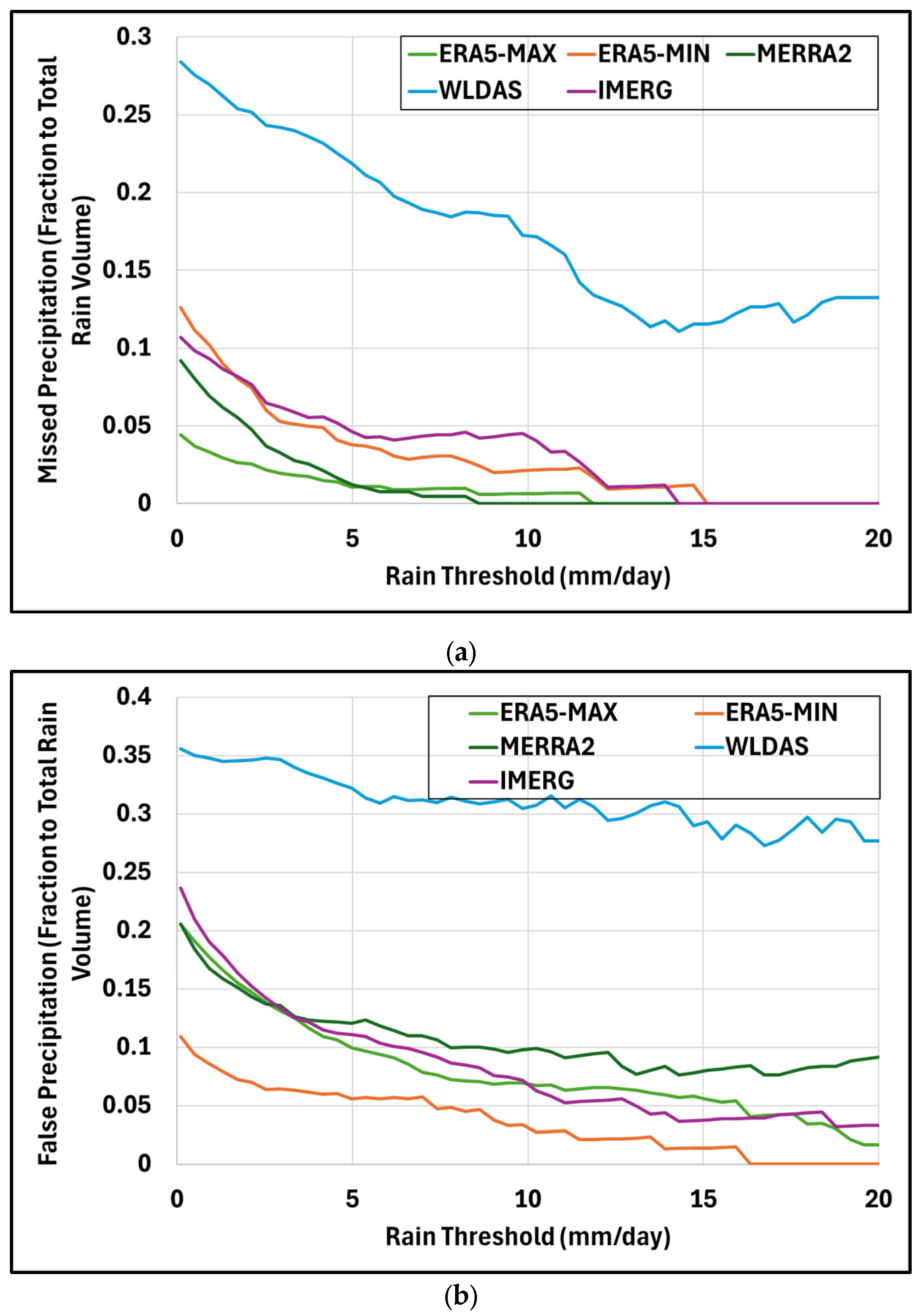

37]. The missed precipitation represents the ratio of the volume of precipitation not captured by the estimation product to the total volume of precipitation captured by the reference product, with respect to the reference rain threshold [

37].

Missed precipitation is computed as a function of the POD contingency values, where the number of missed events is divided by the sum of the number of missed events and hit cases. This is represented by Equation 6 below:

The false alarm rate (FAR) quantifies the number of times the remote dataset incorrectly detected the presence of precipitation by comparing the number of times the remote equipment incorrectly and correctly detected the presence of precipitation:

FAR, or the likelihood of an evaluation product incorrectly detecting precipitation when in fact it does not rain, can be calculated as a function of threshold defined based on the evaluation product, as presented in

Table 3 [

37].

The falsely detected precipitation represents the ratio of the volume of precipitation incorrectly captured by the estimation product to the total volume of precipitation detected by the estimation product, with respect to the reference rain threshold.

Falsely detected precipitation is computed as a function of the FAR contingency values, where the number of false detections is divided by the sum of the number of false detections and hit cases. This is represented by Equation 8 below: