1. Introduction

Head and neck paragangliomas are rare tumors characterized by indolent to slow progression. Not all paragangliomas necessarily need active treatment. However, growing tumors may cause serious complaints primarily involving hearing, balance and swallowing. Surveillance is therefore necessary, with regular MR imaging to evaluate tumor progression. Unfortunately, active treatment modalities, i.e. surgery or radiotherapy, carry an inherent risk of cranial nerve damage that may result in complications very similar to those caused by the tumor itself. Therefore, making treatment decisions is difficult. Being able to make accurate predictions of tumor growth would be of great value when deciding which patients require active intervention in the near or more distant future, and to optimize the timing of active intervention when necessary [

1,

2]. Additionally, accurate growth prediction could improve follow-up timing, and reduce the number of MR scans required for adequate monitoring.

We previously published prediction models for tumor growth that we obtained using a novel eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) technique [

3]. In the current study, we investigate different ways to determine the uncertainty of these prediction models, in order to increase the usefulness and trustworthiness of the predictions.

This study focuses on both historical and Bayesian methods to estimating uncertainty. Furthermore, we examine whether accounting for auto-segmentation uncertainty enhances the uncertainty estimates for growth prediction, since volume measurement is known to introduce some uncertainty [

4]. Additionally, we explore whether employing multiple models for predicting tumor growth can improve uncertainty estimation. Finally, we demonstrate how uncertainty information can be used to distinguish tumors that are very likely to grow from those that will remain stable in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tumor Volume Data

Patients with head and neck paragangliomas treated at the Leiden University Medical Center (Leiden, The Netherlands) were included in this study if at least three MRI scans were acquired for follow-up purposes between 2000 and 2020. Tumor volumes were measured using an AI-based segmentation model developed with nnU-Net [

5], the performance of which has been shown to be on par with that of humans [

6]. The resulting tumor volume was cross-referenced with the radiology report to exclude obvious segmentation errors.

2.2. Tumor Growth Models

Next, we used models generated by an AI algorithm to predict paraganglioma tumor growth [

3]. To ensure physical plausibility, three constraints were applied: (1) the tumor has no significant volume at birth, (2) the predicted volume at age 100 must be smaller than 1500 ml (the largest observed tumor volume at our institution), and (3) tumor volume cannot decrease over time. Further details can be found in

Appendix A.1.

The algorithm identified three distinct models for describing paraganglioma growth well:

These growth models are similar or equivalent to the Gompertz model, which is traditionally used to describe growth of (cell) populations [

7]. All models have an S-shaped curve, consistent with bi-phasic growth patterns: an initial phase of accelerating growth, followed by a phase of decelerating growth.

In these models, the coefficients c1, c2, and c3 are free variables and should be tuned for a specific tumor based on multiple tumor volume measurements at various patient ages (denoted as t in the models). Further details on how we tune these coefficients can be found in

Appendix A.2.

2.3. Uncertainty Estimation Methods

To estimate the uncertainty of growth predictions, we considered two methods: a historical one and a Bayesian one. In the historical method it is assumed that past errors (i.e., deviations from the predictions coming from one of the above models) are representative of future prediction errors, providing the basis for an uncertainty estimate. No explicit modeling of the source of the errors is performed. In the Bayesian method it is assumed that uncertainty in growth predictions can primarily be attributed to the uncertainty associated with the estimation of the model’s coefficients.

To estimate the 95% confidence interval for a growth curve prediction using the historical method, we used the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of normalized historical errors from comparable tumor growth predictions. Errors were considered comparable when the prediction model was based on the same number of measurements to tune the model and the model predicted the same number of years ahead. The historical errors are normalized by tumor volume to account for differences in tumor size.

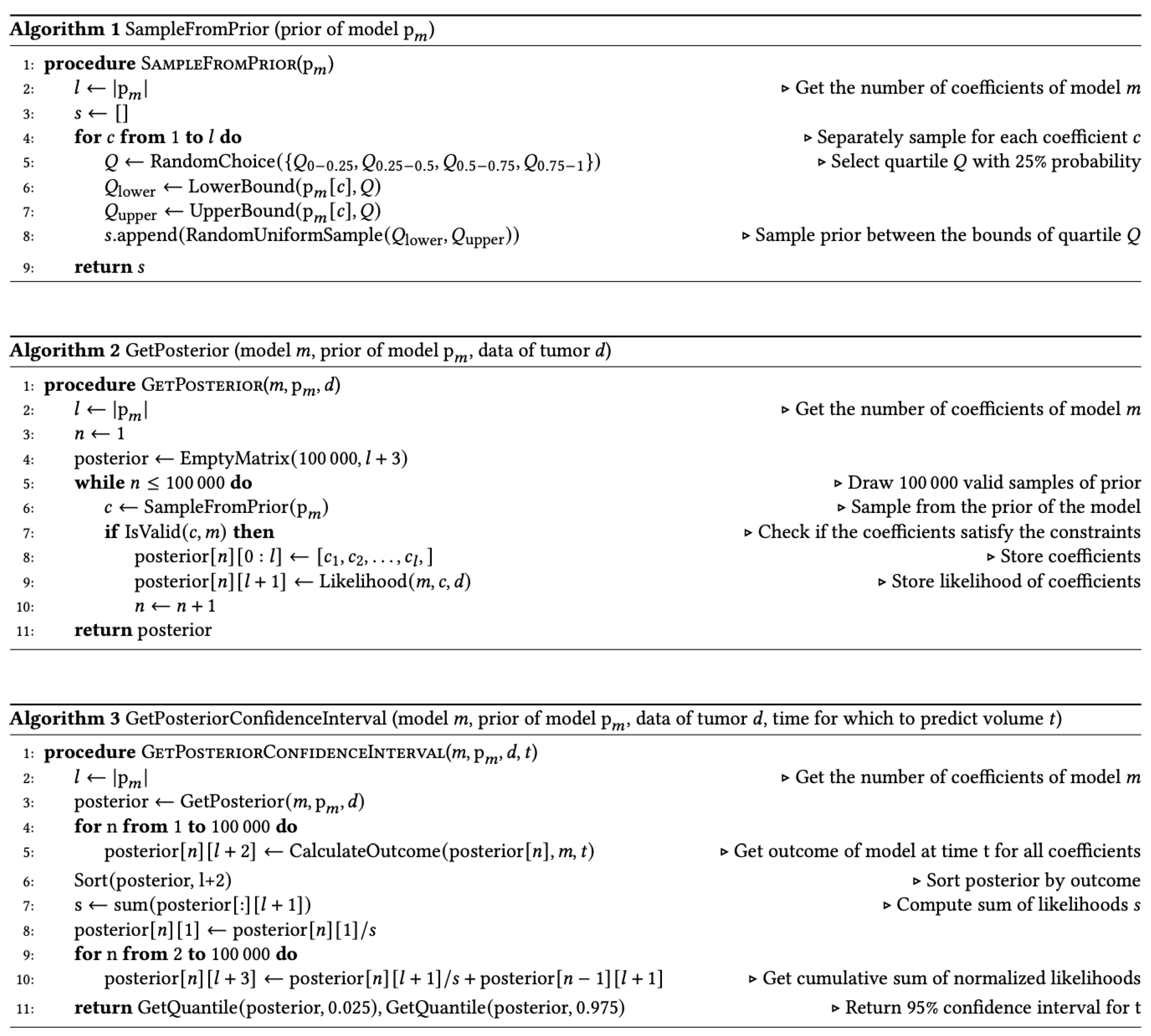

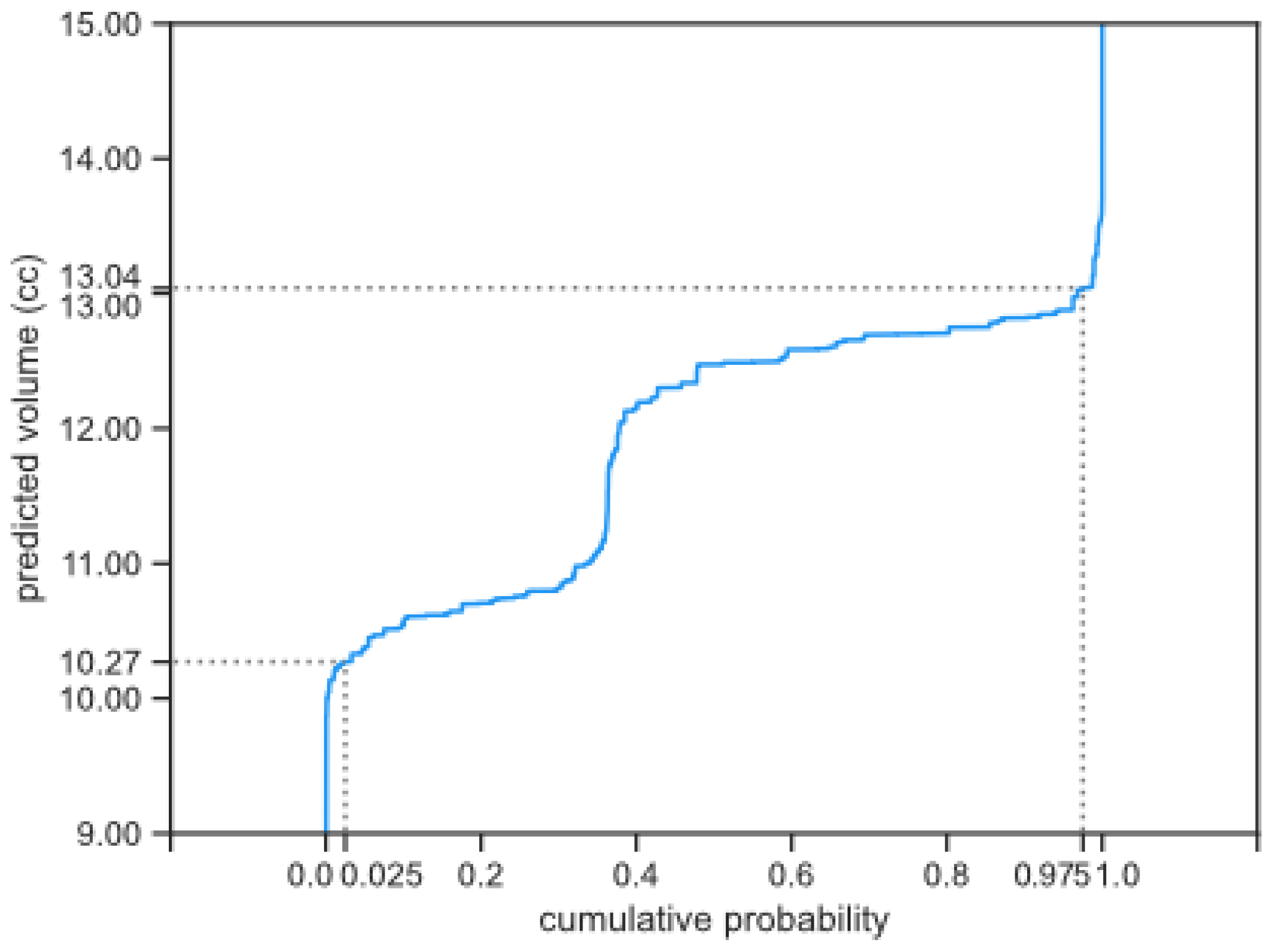

To calculate the estimate of the 95% confidence interval for a growth curve prediction using the Bayesian method, we used a Monte Carlo simulation [

8]. The result of the simulation can be used to transform a single growth prediction into a probability distribution [

9,

10]. From that distribution, we then derived the estimated 95% confidence interval, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Further implementation details can be found in

Appendix A.3.

In the Bayesian method, we factored in the uncertainty of the auto-segmentation. This is done by using a normal distribution estimate of tumor volume instead of a single value as volume measurement. We considered two ways to estimate this distribution: a tumor-specific estimate and a general estimate. Both ways rely on the ensemble method [

11,

12], which is typically useful for output generated by multiple models. Our segmentation model combines the output of five different models, as is standard for models trained with nnU-Net. From the output of these five models, we estimated the standard deviation of the normal distribution. More specifically, for the tumor-specific estimates, standard deviations of the tumor volume of the five different models were used. Further details can be found in

Appendix A.4. For the general method, we used a standard deviation equal to the average of the standard deviations used in the tumor-specific estimates, expressed as a percentage of the mean tumor volume.

2.4. Evaluating Uncertainty Methods

When evaluating uncertainty estimates, two key factors are usually considered: sharpness and calibration [

13]. Sharpness expresses how narrow the estimated confidence interval is, while calibration refers to how frequently observed values fall within the predicted interval. Ideally, estimated confidence intervals are both narrow and well-calibrated. However, there is often a trade-off between these two—improving one can worsen the other.

Some authors suggest offering multiple solutions with different trade-offs between calibration and sharpness for each individual tumor growth prediction [

14]. However, this would either lead to an arbitrary selection or force users to make decisions for each tumor growth prediction, which could introduce additional complexity and bias (when it is difficult to determine the best solution, a user may choose the most convenient solution).

To address this, we compared this trade-off at the method level, rather than the individual tumor level. We assess sharpness by measuring the median prediction interval width of the estimated 95% confidence interval, normalized by tumor volume, and evaluate calibration by tracking how often the observed value falls within the estimated 95% confidence interval.

While calibration and sharpness offer some insight into the usefulness and reliability of estimated confidence intervals, they do not always provide a complete picture. Calibration is typically averaged over multiple data points, which may not capture how well the intervals reflect reality. For example, a model with overly wide intervals for some datapoints and overly narrow intervals for others, might still appear well-calibrated, but it may not accurately reflect real-world outcomes [

15]. Moreover, a model that is well-calibrated but has overly wide intervals may not offer enough information for making treatment decisions.

To address this, we used an evaluation that is aimed at demonstrating usefulness in clinical practice. Specifically, we determined whether the uncertainty estimates can help distinguish between tumors that will grow, remain stable, or have uncertain outcomes.

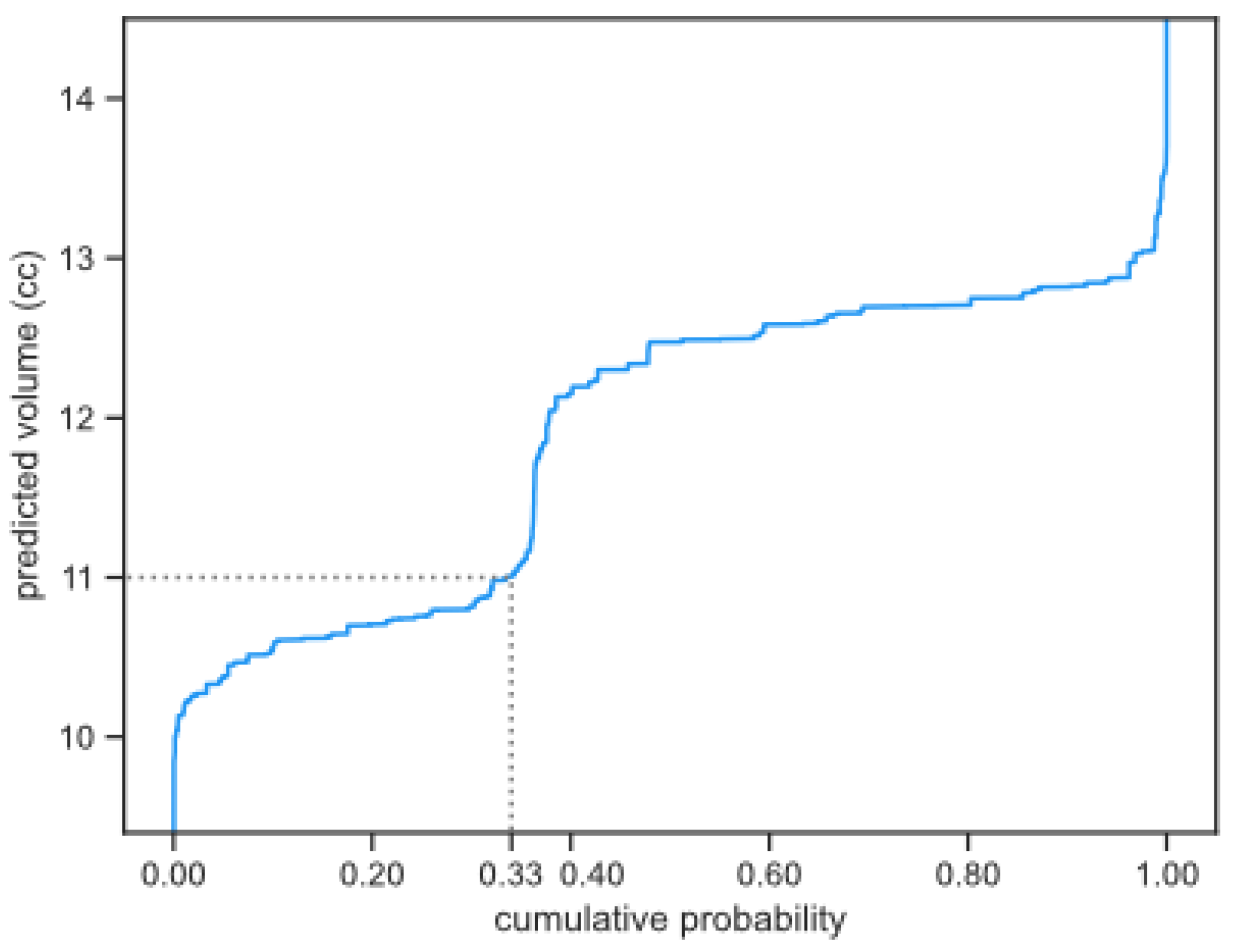

Tumors were classified as having a low (<5%) or high-risk (>90%) for growth, based on the predicted probability of growth using the cumulative probability distribution (as shown in

Figure 2) and using a 20% volume increase as a threshold for growth (the 20% increase was based on [

16]). This classification could be determined for any future moment in time, but we determine the classification for the future moments in which we have available measurements, since it allows us to determine the quality of the risk classifications. If the probability of a 20% increase in tumor volume at the next follow-up was estimated to be less than 5%, the tumor was classified as low risk, whereas if this probability was estimated to be more than 90%, the tumor was classified as high risk. Otherwise, the tumor remained unclassified. We evaluate how well these risk classifications align with the actual tumor growth, using the same 20% as a threshold [

16].

To evaluate whether including multiple growth models as a form of uncertainty improves our risk classifications [

11,

12], we examined both the combined uncertainty of the three growth prediction models (later referred to as the models combined method), as well as their individual uncertainties. The risk classification of the combination of all growth prediction models was calculated by taking the lowest chance of growth when the minimum chance of growth of the three models was above 80%, and by taking the highest chance of growth when the maximum chance of growth of the three models was below 20%, otherwise the average of the three prediction models was taken. This approach adopts a more conservative stance on risk classification than averaging the results of the three models by essentially looking at the worst case.

3. Results

We used data of 213 patients. Five patients were excluded because their volume measurements could not be matched with the radiology reports. In the remaining 208 patients, a total of 311 paragangliomas were detected. A total of 1515 tumor segmentations were available from these 311 tumors. Fourteen of those tumor segmentations were deemed inaccurate since they did not align with the tumor volume changes as described in the radiology reports, and were not included in the growth predictions. With the remaining 1501 tumor segmentations, we could study 2547 tumor growth predictions (a median of 10 predictions per tumor).

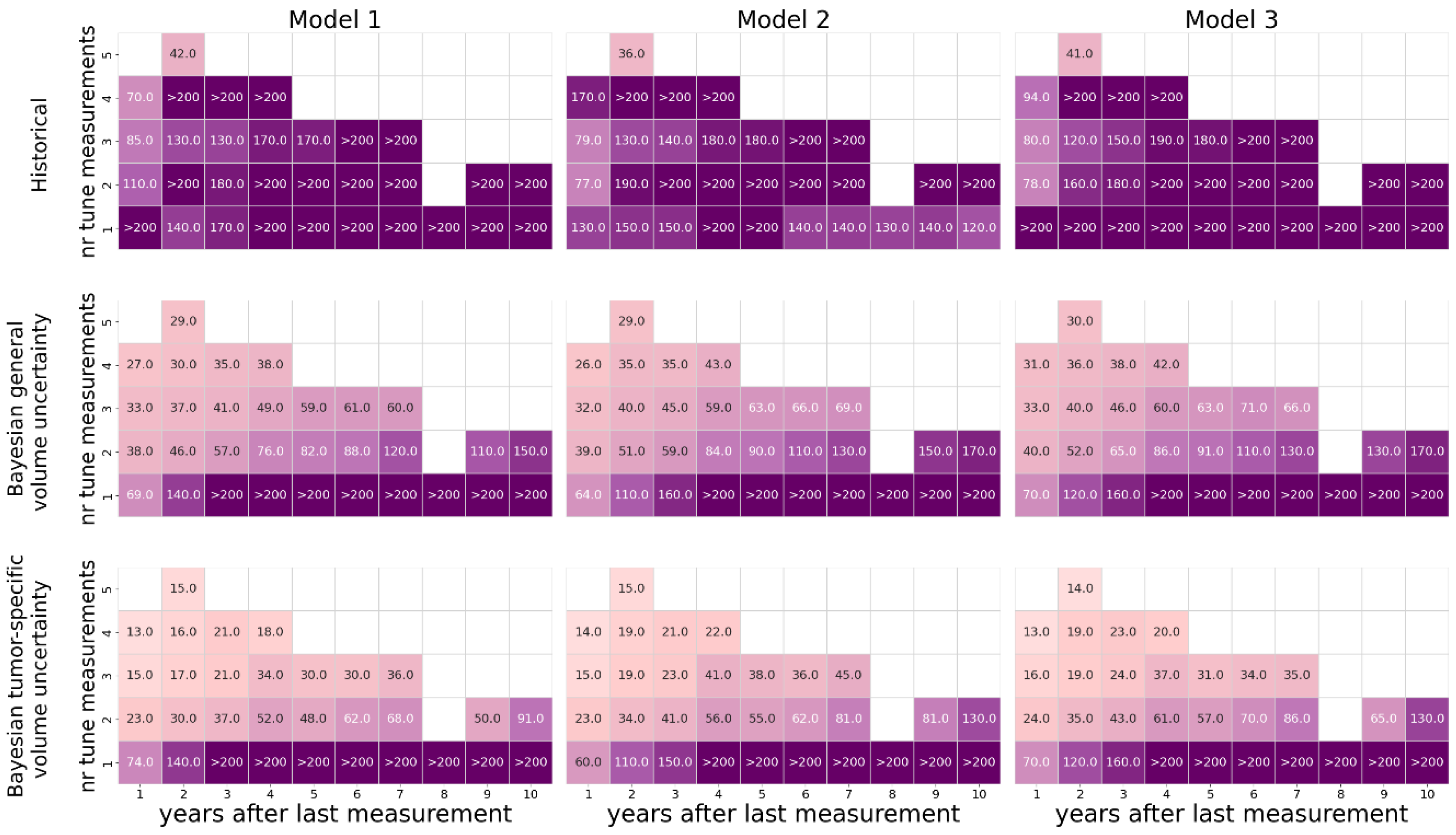

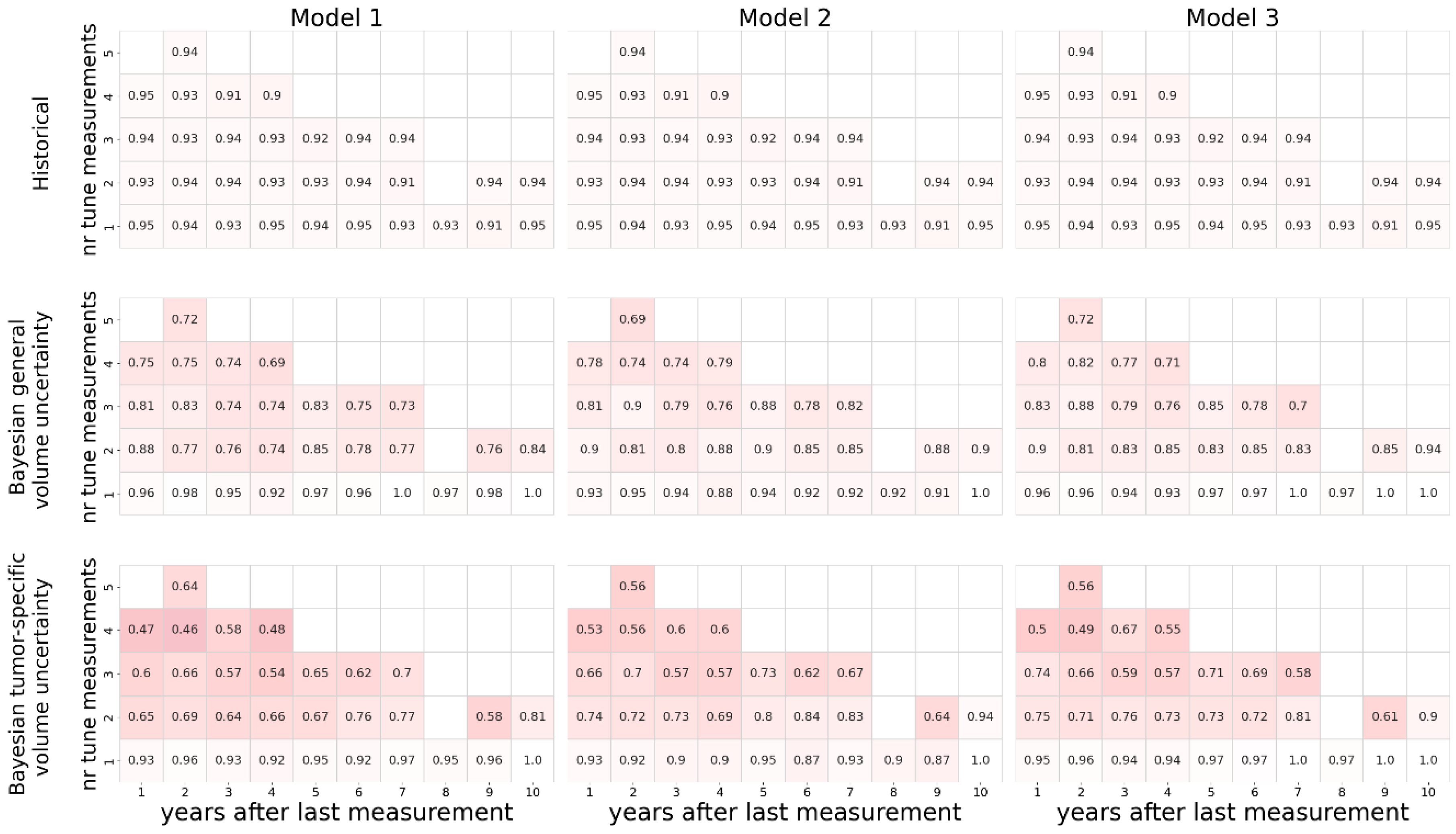

The sharpness of the estimated uncertainty is shown in

Figure 3. As expected, the uncertainty increases with a decreasing number of measurements used to tune the coefficients, and with forecasts projected further in time. In line with this, most predictions based only on a single tumor volume measurement resulted in a 95% confidence interval that is bigger than the predicted volume itself, regardless of the method used. The historical method estimated large confidence intervals for all predictions, often surpassing 200%. The Bayesian method led to narrower estimations of the confidence intervals. Using tumor-specific estimations of auto-segmentation uncertainty generally narrowed the estimated confidence intervals. With respect to the estimated uncertainty, no relevant differences were observed between the three different growth models.

The calibration in terms of the proportion of predictions where the actual measurement fell within the predicted estimated 95% confidence interval is shown in

Figure 4. As expected, this shows an inverse relation to the width of the estimated confidence intervals estimated and depicted in

Figure 3.

The historically generated uncertainty estimates did not reliably differentiate between tumors with a low (<5%) or high (>90%) risk of growth (

Table 1). Bayesian derived estimates performed much better both using general volumetric or tumor-specific volumetric uncertainty, especially when the output of all 3 models was combined.

Table 1 shows that the Bayesian method that uses general volume auto-segmentation uncertainties performed better in the low risk category (8.2% vs 15.3% growth). The number of classified tumors however was much higher in the tumor-specific estimate, reducing the number of unclassified predictions from 2017 to 1746 (

Table 2). The unclassified predictions were mainly based on 1 or 2 observed tumor volumes only, but represent the majority of predictions made.

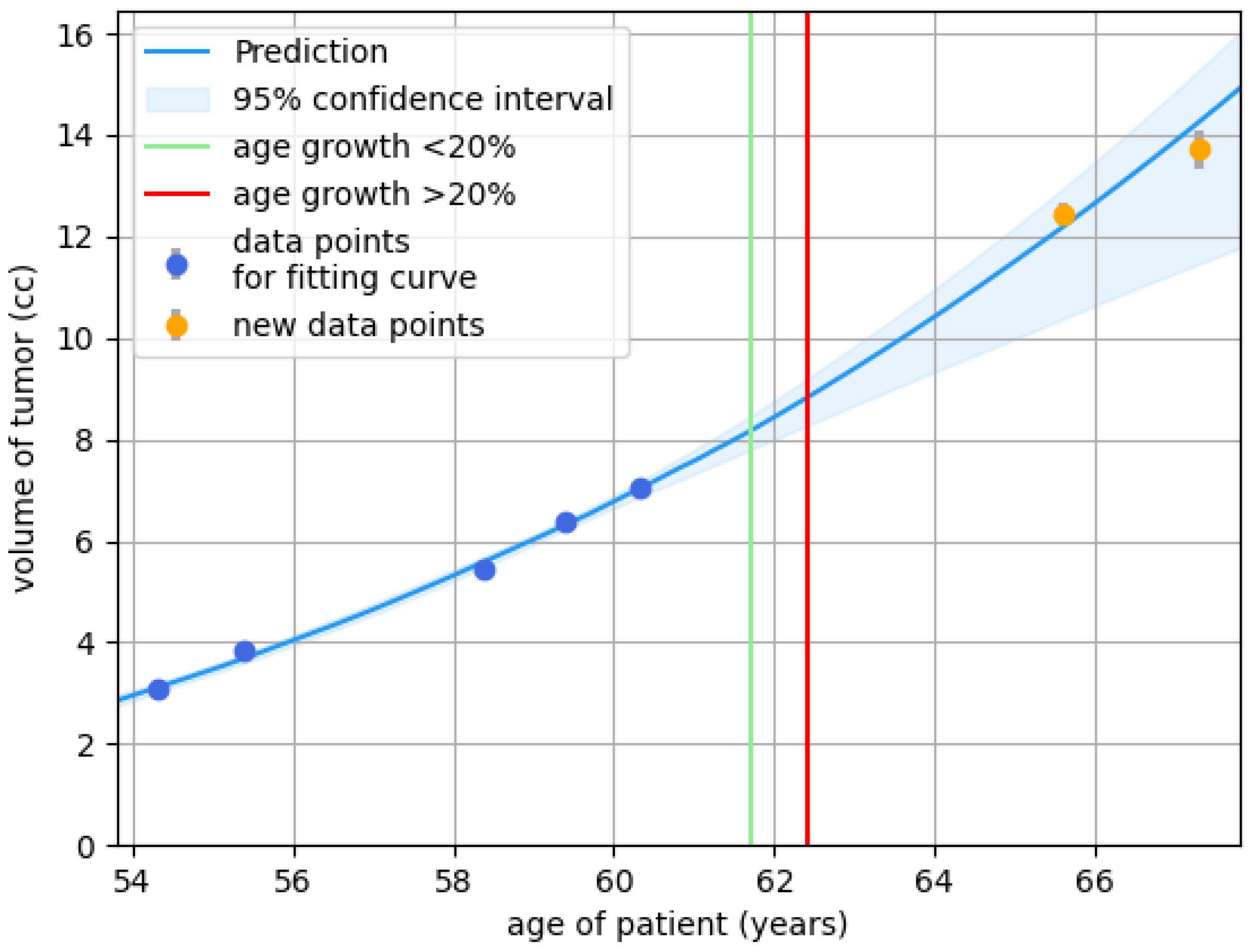

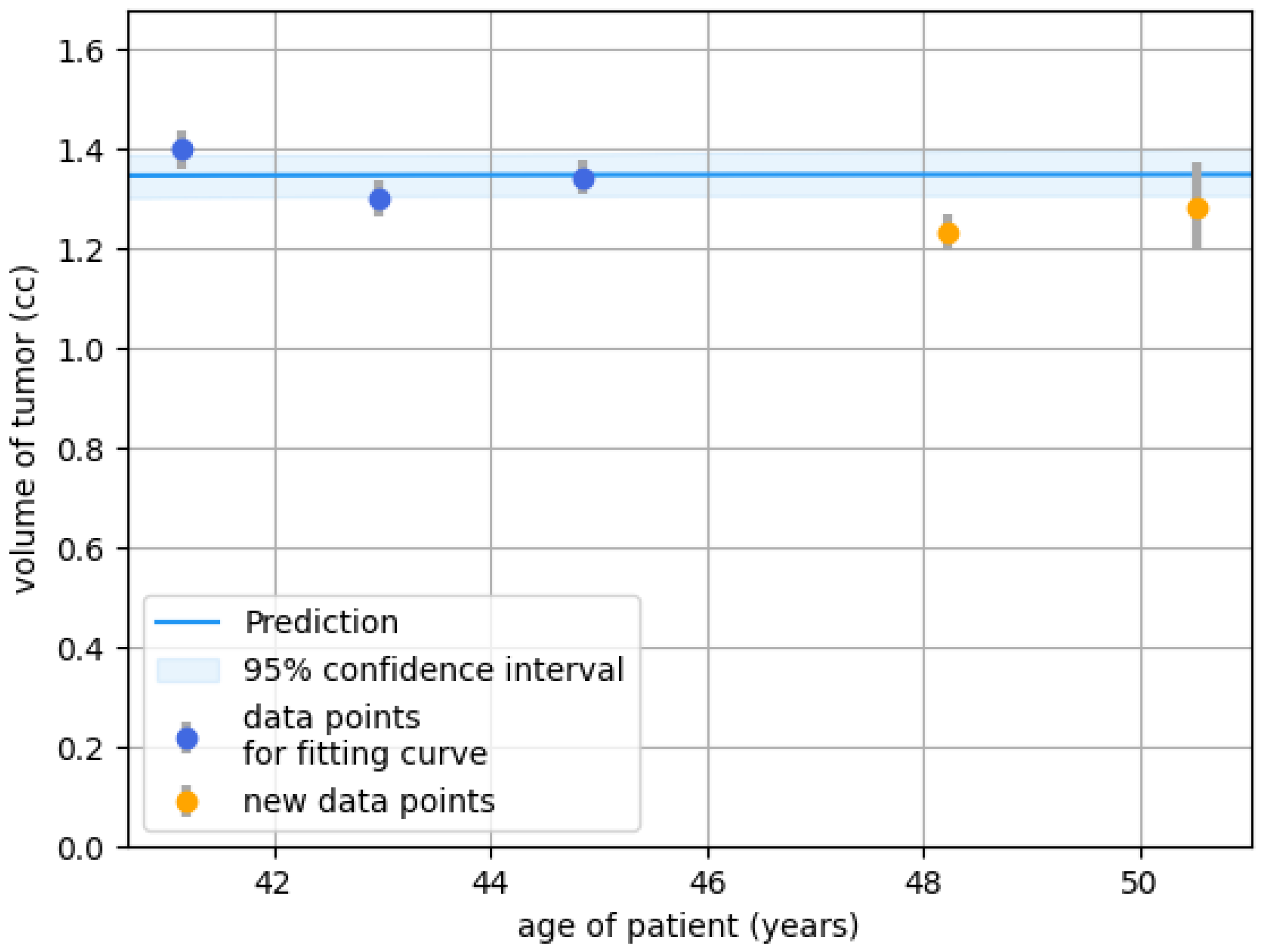

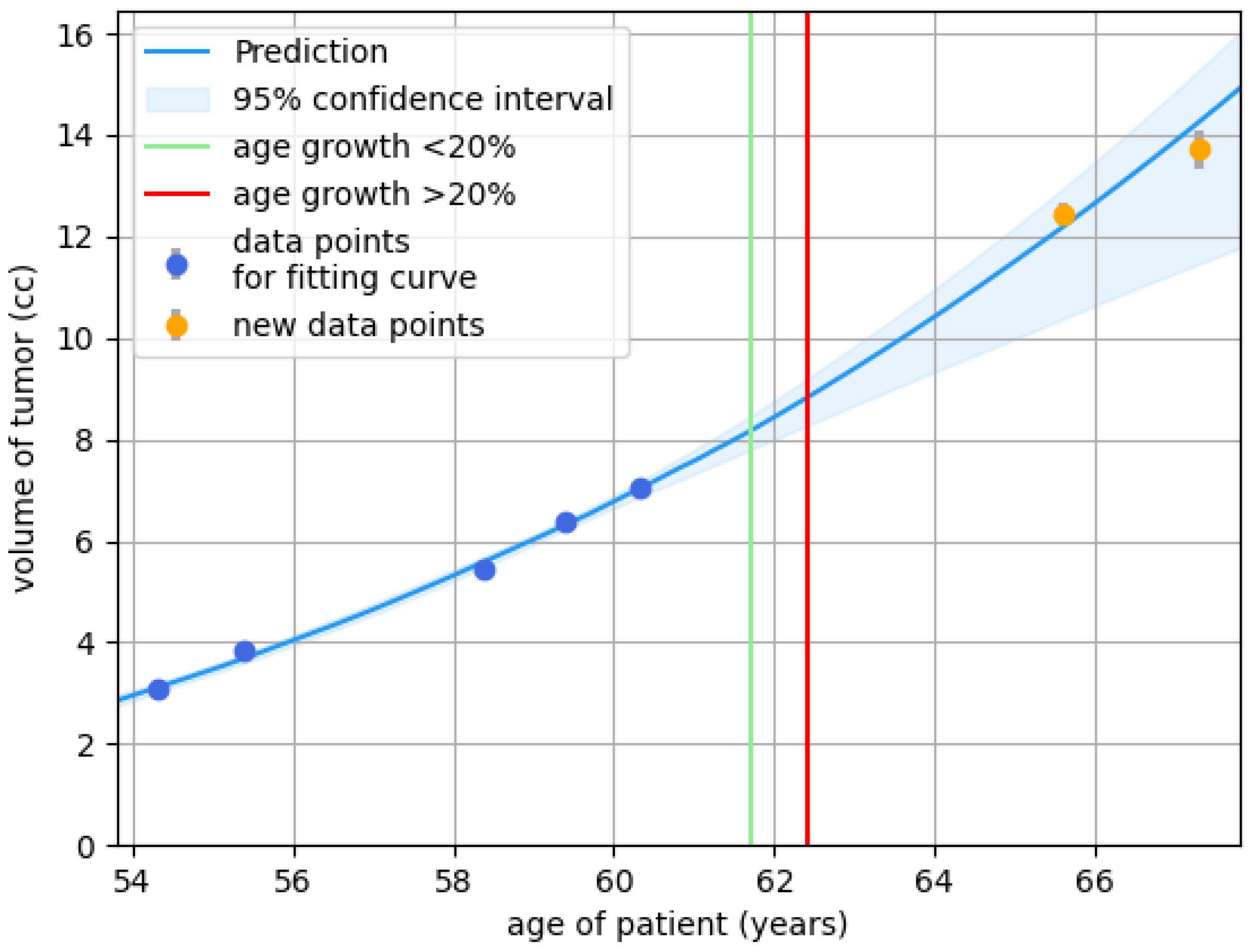

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are examples of how the presented methods could be useful in practice.

Figure 5 shows a case of a clearly growing tumor, for which the prediction (of the Bayesian method) could have been a reason for earlier follow-up, or even a proposal for active treatment. In contrast, the prediction (of the Bayesian method) of a stable volume in the case depicted in

Figure 6 could have led to less frequent imaging. In these scenarios, the risk classifications can guide better-informed timing of follow-up measurements, avoiding assessment of the tumor before detectable growth has occurred (which could cause a false sense of security) and after excessive growth has occurred (which could lead to potentially irreversible complications).

4. Discussion

The management of head and neck paragangliomas is challenging because of their uncertain behavior. Although other factors like symptoms, age, and co-morbidity play an important role too, treatment decisions largely depend on the expected growth of a paraganglioma. Accurate prediction of growth would therefore be enormously helpful in clinical decision-making. Discovering and fitting growth models as a means of making predictions however does not incorporate the uncertainty that is inherent to making predictions. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to compare different methods for estimating the uncertainty of the growth prediction.

The historical method resulted in estimated confidence intervals that were so high that they most likely are not useful in clinical practice. Both variants of the Bayesian method produce narrower confidence intervals, but are less favorable with regard to calibration. This can be explained by the fact that the historical method prioritizes calibration (by setting its estimation for the confidence intervals to match the distribution), relevant specifics of the problem such as volume measurement data and model characteristics are not taken into account. By using these problem-specific details, the Bayesian method can individualize the intervals for each specific tumor. Most importantly, the Bayesian method was found to perform best at differentiating between tumors that will grow, remain stable, and those with a more uncertain course. This type of prediction is likely very helpful in a clinical context.

Using multiple prediction models of growth simultaneously improved performance. We argue that the tumor-specific auto-segmentation uncertainty is preferred over the general uncertainty. Although the general method performed better in the low risk category, the tumor-specific method was on par in the high risk category and was able to classify 50% more predictions within their adequate risk categories. Multiple sources can introduce uncertainty [

12,

17], so combining uncertainty over the prediction models, coefficients, and volume measurements in the estimation method appears to make sense.

While we evaluated multiple models and also combinations of these models, some growth patterns might still not be covered. It very seldom occurs that a tumor drastically decreases in volume (in our dataset approximately 1% of tumors), which is not captured in either of the three models. Because only a handful of tumors show this behavior, it is more suitable for a case study than incorporating it into any (AI-based) growth model, merely because there is so little data on this phenomenon. Therefore, this scenario is not taken into account in our method. Additionally, in at least a few cases, the tumor seems to be stable over some time and then seems to resume progression later on. This pattern is also not covered by our three growth patterns. Further research should be performed to determine whether this pattern is valid, or whether (large) measurement errors could still play a role.

Finally, the Bayesian approach used here attributes growth prediction uncertainty mainly to uncertainty in the coefficients of the growth models, given the nnU-Net–derived tumor volume distributions. However, the resulting uncertainty bands are not the same as those obtained by repeatedly sampling tumor volumes from the nnU-Net–derived tumor volume distributions and refitting growth models. While both approaches may produce similar margins of uncertainty, the final shape of the growth curves for individual patients can differ. Studying the practical relevance of these differences remains a topic of interest for future work.

The auto-segmentation uncertainty estimates could be further developed and systematically evaluated. Although the volume measurement uncertainties of the segmentation model do show a slight improvement in performance in risk classification, our current study does not directly evaluate these uncertainty estimates. Furthermore, other sources of measurement variation such as geometric uncertainties of the MRI scan itself [

18] or uncertainties related to variations in patient positioning are not quantified nor taken into account. Further studies would be required to determine whether these or other potential sources of uncertainty have significant impact on the prediction of paraganglioma growth.

While the nnU-Net ensemble provides a measure of variability, it does not directly capture the clinically relevant source of uncertainty, namely inter-observer variation. In the limit of very large training datasets, the variance of an nnU-net ensemble would approach zero, whereas observer variability remains irreducible. To capture this type of variability, deep learning methods that explicitly model differences in annotations are required (e.g., [

19]).

5. Conclusions

We have proposed two methods for adding uncertainty estimates to tumor growth predictions. We found that, in the context considered, the Bayesian method performed best when distinguishing between growing and non-growing tumors, and is therefore the preferred method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ES, TA, PB and JJ; methodology, ES, VV and JJ; software, ES.; validation, ES,VV, TA, and PB; formal analysis, ES, VV and JJ.; investigation, ES.; resources, TA, PB and JJ.; data curation, ES.; writing—original draft preparation, ES, VV and JJ; writing—review and editing, TA, PB, BV and EH; visualization, ES; supervision, JJ; project administration, VV and JJ.; funding acquisition, TA and PB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission within the HORIZON Programme (TRUST AI Project, Contract No.: 952060).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Patients were informed about the research project, with the possibility to withdraw their data from the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because patients were informed that their data would only be used as part of this research project, and would not be publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Learning the Growth Prediction Models

The functional forms of the growth prediction models (i.e., including the free variables) were learned using a subset of the data, with the same settings and the same algorithm as described in [

1]. The data set is split into two subsets. The first subset contains 80% of the tumors and is used during development of the models, also referred to as training data set. The other 20% is held out to test the developed models. When splitting the data, we balance the number of data points per tumor data set, such that each subset has a proportional number of measurements per data set. Additionally, if a patient had multiple tumors, all tumors were assigned the same split to keep the training and test set independent. The subset used to learn the growth models is comprised of the tumors in the training data set for which at least five measurements are available.

Appendix A.2 Fitting the Growth Prediction Models

When fitting the growth prediction models (i.e., tuning the free variables in the functional forms), we used fine-tuned coefficient ranges and we constrained unlikely rapid growth. Specifically, the constraint prohibits more than 10 times volume increase in a year. Because we only know what is within the range of realistic growth when the tumor is at a human-detectable volume, this constraint is only considered when the tumor volume is at least 0.1 cc at the start of that year. To determine the fine-tuned coefficient ranges, for each coefficient we calculated the minimum and maximum values for that coefficient as observed for the fitted models in the training data set with at least five measurements (the same set as used for learning the growth prediction models). The maximum tumor volume coefficient c

1 is set to 1500 cc. Any other settings as well as the algorithm used for fitting the models are the same as in [

3].

Appendix A.3 Implementation Details Bayesian Method

The Monte Carlo simulation of the Bayesian method is started with an initial estimate of the distribution over the model coefficients, based on historical data from previous paraganglioma growth patterns. Next, the distribution over these coefficients is refined using the tumor volume measurements. This is achieved by repeatedly varying the initial coefficients and calculating the likelihood of the observed volume data for each variation, progressively updating the distribution to better match the tumor growth.

The pseudo-code of the method is given in

Figure 7. As a prior distribution over the coefficients, we employ a stratified Monte Carlo method [

20], in which we sample uniformly within each quartile of the fine-tuned coefficient ranges (as described in A2), with each quartile sampled equally (Algorithm 1). This method provides a computationally efficient approach that better reflects the prior than a naive uniform or Gaussian approximation. With this prior, we reduce the likelihood of sampling invalid coefficient sets, which speeds up the simulation up to one order of magnitude compared to naive (min-max) uniform sampling.

Figure 7.

Pseudo-code for performing Bayesian calculation.

Figure 7.

Pseudo-code for performing Bayesian calculation.

To get the posterior distribution, we first sample 100.000 valid coefficients sets from the prior distribution (Algorithm 2, line 5 -10). This number of samples was experimentally determined to have a high likelihood of convergence. The coefficients are not valid when any of the four constraints are violated (Algorithm 2, line 7). Otherwise, the likelihood is calculated under the assumption of a normal distribution, with the following formula (Algorithm 2, line 9):

(the mean) and (the standard deviation) are derived from the segmentation model, and is the volume predicted by the growth model for the specific set of coefficients for each of the K data points. Next, the cumulative probability distribution is calculated for a specific age t. Predictions for all 100.000 coefficient sets are made using the growth prediction model with t (Algorithm 3, line 4 and 5). These predictions are then sorted in ascending order (Algorithm 3, line 6). Next, the corresponding likelihoods of those predictions are normalized by the sum of all likelihoods, and their cumulative sum is computed to obtain the cumulative probability distribution (Algorithm 3, line 7-10). Based on the cumulative probability distribution the 95% confidence is obtained (Algorithm 3, line 11).

Appendix A.4 Calculating the Tumor-Specific Standard Deviation

To calculate the tumor-specific standard deviation, we use the output of the 5 neural networks in the segmentation model obtained using nnU-net. Since multiple tumors could be present in one scan, it has to be decided which of the volume segmentations in the individual outputs refer to which tumor in the overall segmentation. We do so by matching each volume in the individual outputs to a volume in the overall segmentation. Each volume is only matched once (to the volume with the most overlap), and any volumes that do not overlap are left out. For any outliers in the standard deviations as ratio of the mean value, the individual volumes were inspected and if any outlier values were detected, the volumes causing the outlier value in the standard deviation were removed. This happened for 4 of the 1501 measurements.

References

- Heesterman B, de Pont L, Verbist B, et al. Age and Tumor Volume Predict Growth of Carotid and Vagal Body Paragangliomas. Journal of Neurological Surgery Part B Skull Base. 2017;78(06):497-505. [CrossRef]

- Heesterman B, Bokhorst J, de Pont L, et al. Mathematical Models for Tumor Growth and the Reduction of Overtreatment. Journal of Neurological Surgery Part B: Skull Base. 2018;80(01):072-078. [CrossRef]

- Sijben E, Jansen J, Bosman P, Alderliesten T. Function Class Learning with Genetic Programming: Towards Explainable Meta Learning for Tumor Growth Functionals. Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference. Published online , 2024:1354-1362. [CrossRef]

- Heesterman B, Verbist B, van der Mey A, et al. Measurement of head and neck paragangliomas: is volumetric analysis worth the effort? A method comparison study. Clinical Otolaryngology. 2016;41(5):571-578. [CrossRef]

- Isensee F, Jaeger PF, Kohl SAA, Petersen J, Maier-Hein KH. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nature Methods. 2020;18(2):203-211. [CrossRef]

- Sijben E, Jansen J, de Ridder M, Bosman P, Alderliesten T. Deep learning-based auto-segmentation of paraganglioma for growth monitoring. arXiv (Cornell University). Published online , 2024. [CrossRef]

- Winsor, CP. The Gompertz Curve as a Growth Curve. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1932;18(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Mooney, CZ. Monte Carlo Simulation. Sage Publications; 1997.

- Dimitriou NM, Demirag E, Strati K, Mitsis GD. A calibration and uncertainty quantification analysis of classical, fractional and multiscale logistic models of tumour growth. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2024;243:107920. [CrossRef]

- Collis J, Connor AJ, Paczkowski M, et al. Bayesian Calibration, Validation and Uncertainty Quantification for Predictive Modelling of Tumour Growth: A Tutorial. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2017;79(4):939-974. [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan B, Pritzel A, Blundell C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty estimation using deep ensembles. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates Inc.;6405-6416.

- Werner M, Junginger A, Hennig P, Martius G. Uncertainty in equation learning. Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion. Published online , 2022:2298-2305. [CrossRef]

- Chung Y, Char I, Guo H, Schneider J, Neiswanger W. Uncertainty Toolbox: an Open-Source Library for Assessing, Visualizing, and Improving Uncertainty Quantification. arXiv.org. Published 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.

- Andreu-Vilarroig C, Josu Ceberio, Juan-Carlos Cortés, Fernández F, Hidalgo JI, Villanueva RJ. Evolutionary approach to model calibration with uncertainty. Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion. Published online , 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sluijterman L, Cator E, Heskes T. How to evaluate uncertainty estimates in machine learning for regression? Neural Networks. 2024;173:106203-106203. [CrossRef]

- Jansen JC, van den Berg R, Kuiper A, van der Mey AGL, Zwinderman AH, Cornelisse CJ. Estimation of growth rate in patients with head and neck paragangliomas influences the treatment proposal. Cancer. 2000;88(12):2811-2816.

- Gawlikowski J, Tassi N, Ali M, et al. A survey of uncertainty in deep neural networks. Artificial Intelligence Review. Published online , 2023. [CrossRef]

- Weygand J, Fuller CD, Ibbott GS, et al. Spatial Precision in Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Radiation Therapy: The Role of Geometric Distortion. 2016;95(4):1304-1316. [CrossRef]

- Dushatskiy, A. , Lowe, G., Bosman, P. A., & Alderliesten, T. (2022, April). Data variation-aware medical image segmentation. In Medical Imaging 2022: Image Processing (Vol. 12032, pp. 759-765). SPIE.

- Kroese, D. P. , Taimre, T., & Botev, Z. I. (2013). Handbook of monte carlo methods. John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 1.

Example of how the 95% confidence interval is derived from a cumulative probability distribution associated with the Bayesian method. In this example, the 95% confidence interval ranges from 10.27 to 13.04 cc.

Figure 1.

Example of how the 95% confidence interval is derived from a cumulative probability distribution associated with the Bayesian method. In this example, the 95% confidence interval ranges from 10.27 to 13.04 cc.

Figure 2.

Example of probability that the tumor will grow bigger than a certain volume, derived from the cumulative probability distribution. In this example the probability that the tumor grows above 11 cc is 67%.

Figure 2.

Example of probability that the tumor will grow bigger than a certain volume, derived from the cumulative probability distribution. In this example the probability that the tumor grows above 11 cc is 67%.

Figure 3.

Median width of the estimated 95% confidence interval as percentage of the tumor volume. Darker colors indicate wider confidence intervals and, therefore, worse scores. For each method the three different growth models are compared. The impact of multiple measurements vertical axis) and number of years to forecast (horizontal axis) are plotted, showing the best results for short term predictions based on multiple historical measurements using the Bayesian method and tumor specific volume uncertainty.

Figure 3.

Median width of the estimated 95% confidence interval as percentage of the tumor volume. Darker colors indicate wider confidence intervals and, therefore, worse scores. For each method the three different growth models are compared. The impact of multiple measurements vertical axis) and number of years to forecast (horizontal axis) are plotted, showing the best results for short term predictions based on multiple historical measurements using the Bayesian method and tumor specific volume uncertainty.

Figure 4.

The fraction of prediction instances that fell in the estimated 95% confidence interval. Darker colors indicate lower fractions and, therefore, worse scores. For each method the three different growth models are compared. The impact of multiple measurements (vertical axis) and number of years to forecast (horizontal axis) are plotted, showing the best results for short term predictions based on multiple historical measurements for the Historical method.

Figure 4.

The fraction of prediction instances that fell in the estimated 95% confidence interval. Darker colors indicate lower fractions and, therefore, worse scores. For each method the three different growth models are compared. The impact of multiple measurements (vertical axis) and number of years to forecast (horizontal axis) are plotted, showing the best results for short term predictions based on multiple historical measurements for the Historical method.

Figure 5.

Growth prediction with an estimated 95% confidence interval and age thresholds for risk classification: low-risk to unclassified (green) and unclassified to high-risk (red), based on the data points (blue). The orange points represent future data that the model does not use. Grey bars indicate uncertainty in tumor-specific volume measurement. This example illustrates how short follow-ups comparing dimensional size (the standard clinical practice) rather than comparing total volume of the tumor (using volume measurement based on auto-segmentation), may falsely suggest no growth (ages 55.5, 59.5, and 60.5), leading to extended follow-up periods before growth is observed. Using the green and orange lines to guide follow-up decisions could support a balanced measurement strategy, preventing both premature assessments (which may miss growth) and overly delayed ones (which may allow significant growth, potentially leading to irreversible complaints). At ages 59.5 and 60.5, no growth was detected, and follow-up time was extended, but following the growth predictions, different conclusions might have been reached, possibly leading to shorter follow-up intervals or consideration of active treatment.

Figure 5.

Growth prediction with an estimated 95% confidence interval and age thresholds for risk classification: low-risk to unclassified (green) and unclassified to high-risk (red), based on the data points (blue). The orange points represent future data that the model does not use. Grey bars indicate uncertainty in tumor-specific volume measurement. This example illustrates how short follow-ups comparing dimensional size (the standard clinical practice) rather than comparing total volume of the tumor (using volume measurement based on auto-segmentation), may falsely suggest no growth (ages 55.5, 59.5, and 60.5), leading to extended follow-up periods before growth is observed. Using the green and orange lines to guide follow-up decisions could support a balanced measurement strategy, preventing both premature assessments (which may miss growth) and overly delayed ones (which may allow significant growth, potentially leading to irreversible complaints). At ages 59.5 and 60.5, no growth was detected, and follow-up time was extended, but following the growth predictions, different conclusions might have been reached, possibly leading to shorter follow-up intervals or consideration of active treatment.

Figure 6.

Growth prediction with a 95% confidence based on the data points (blue). The orange points represent future data that the prediction model does not use. Grey bars indicate uncertainty in tumor-specific volume measurement. The tumor is not predicted to grow the coming years. Based on this prediction, follow-up might have been done after a 5-year interval (at age 50), measuring once instead of twice.

Figure 6.

Growth prediction with a 95% confidence based on the data points (blue). The orange points represent future data that the prediction model does not use. Grey bars indicate uncertainty in tumor-specific volume measurement. The tumor is not predicted to grow the coming years. Based on this prediction, follow-up might have been done after a 5-year interval (at age 50), measuring once instead of twice.

Table 1.

Observed growth percentages for different risk classifications. These scores reflect how well the method and model were able to correctly classify the risk of growth. The better the risk classifications, the better the observed growth percentages aligned with them. Consequently, low growth percentages are desired in the low risk category, and high growth percentages are desired in the high risk category. The scores marked in bold are the best scores for that method.

Table 1.

Observed growth percentages for different risk classifications. These scores reflect how well the method and model were able to correctly classify the risk of growth. The better the risk classifications, the better the observed growth percentages aligned with them. Consequently, low growth percentages are desired in the low risk category, and high growth percentages are desired in the high risk category. The scores marked in bold are the best scores for that method.

| Uncertainty method |

Model |

Low risk |

Unclassified |

High risk |

| Historical |

Model 1 |

41.7 |

58.5 |

58.5 |

| Model 2 |

60.0 |

58.5 |

43.8 |

| Model 3 |

50.0 |

58.5 |

55.0 |

| |

Models combined |

45.0 |

58.6 |

43.8 |

| Bayesian general volume uncertainty |

Model 1 |

15.2 |

60.6 |

84.9 |

| Model 2 |

15.7 |

62.0 |

86.6 |

| Model 3 |

20.5 |

61.1 |

86.7 |

| Models combined |

8.2 |

60.7 |

88.7 |

| Bayesian tumor-specific uncertainty |

Model 1 |

18.8 |

61.2 |

85.2 |

| Model 2 |

18.7 |

63.1 |

86.8 |

| Model 3 |

24.7 |

63.3 |

87.0 |

| Models combined |

15.3 |

62.5 |

88.3 |

Table 2.

Number of predictions within the different risk classifications (for the combined models).

Table 2.

Number of predictions within the different risk classifications (for the combined models).

| Uncertainty method |

Low risk |

Unclassified |

High risk |

| Historical |

20 |

2511 |

16 |

| Bayesian general volume uncertainty |

255 |

2017 |

275 |

| Bayesian tumor-specific uncertainty |

424 |

1746 |

377 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).