Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measurement of Variables

2.3.1. Dietary Diversity Score

2.3.2. Others Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Food Groups Consumed, Prevalence of Dietary Diversity and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Factors Associated with Being on Adequate Dietary Diversity

3.2.1. Multivariate Logistic Regression

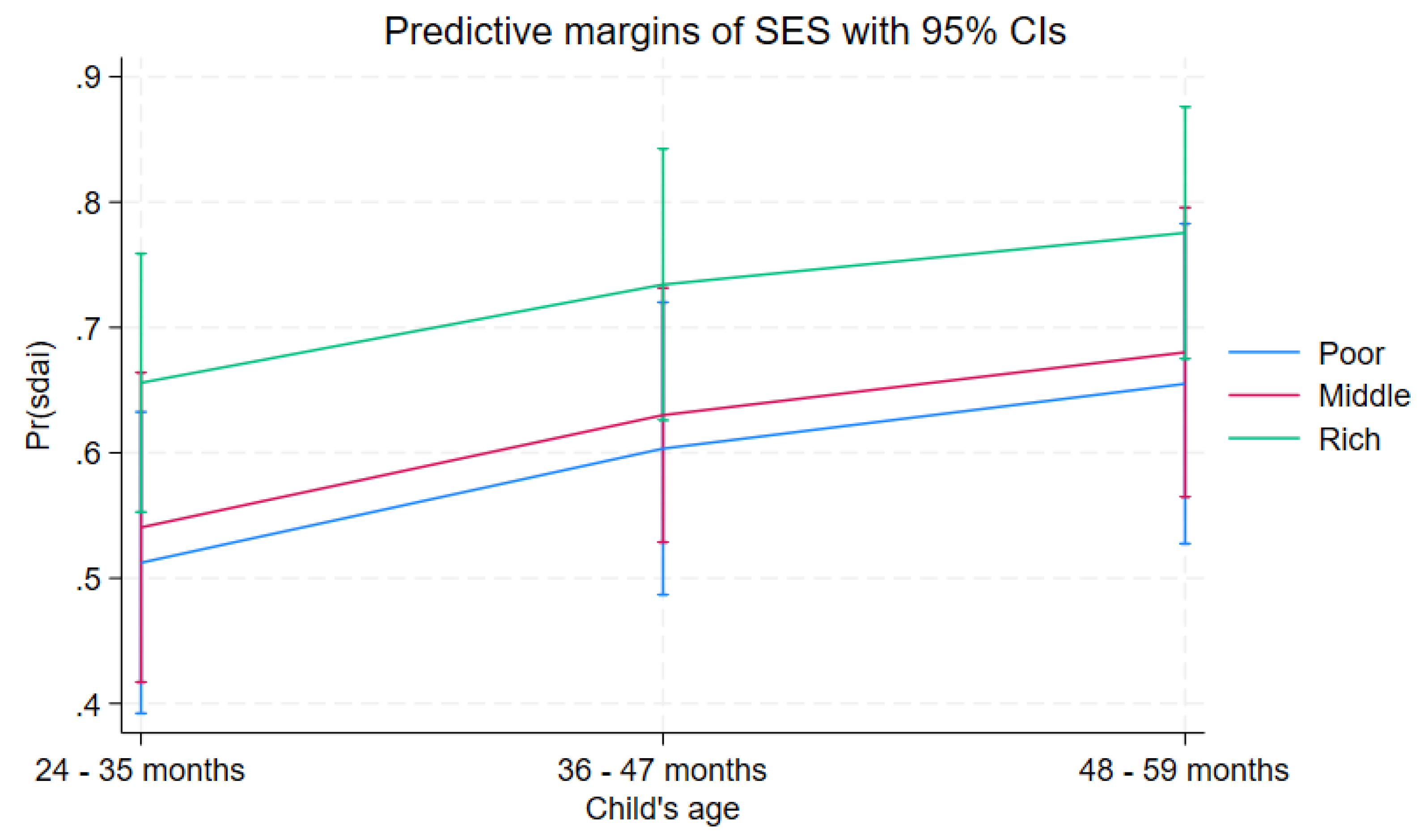

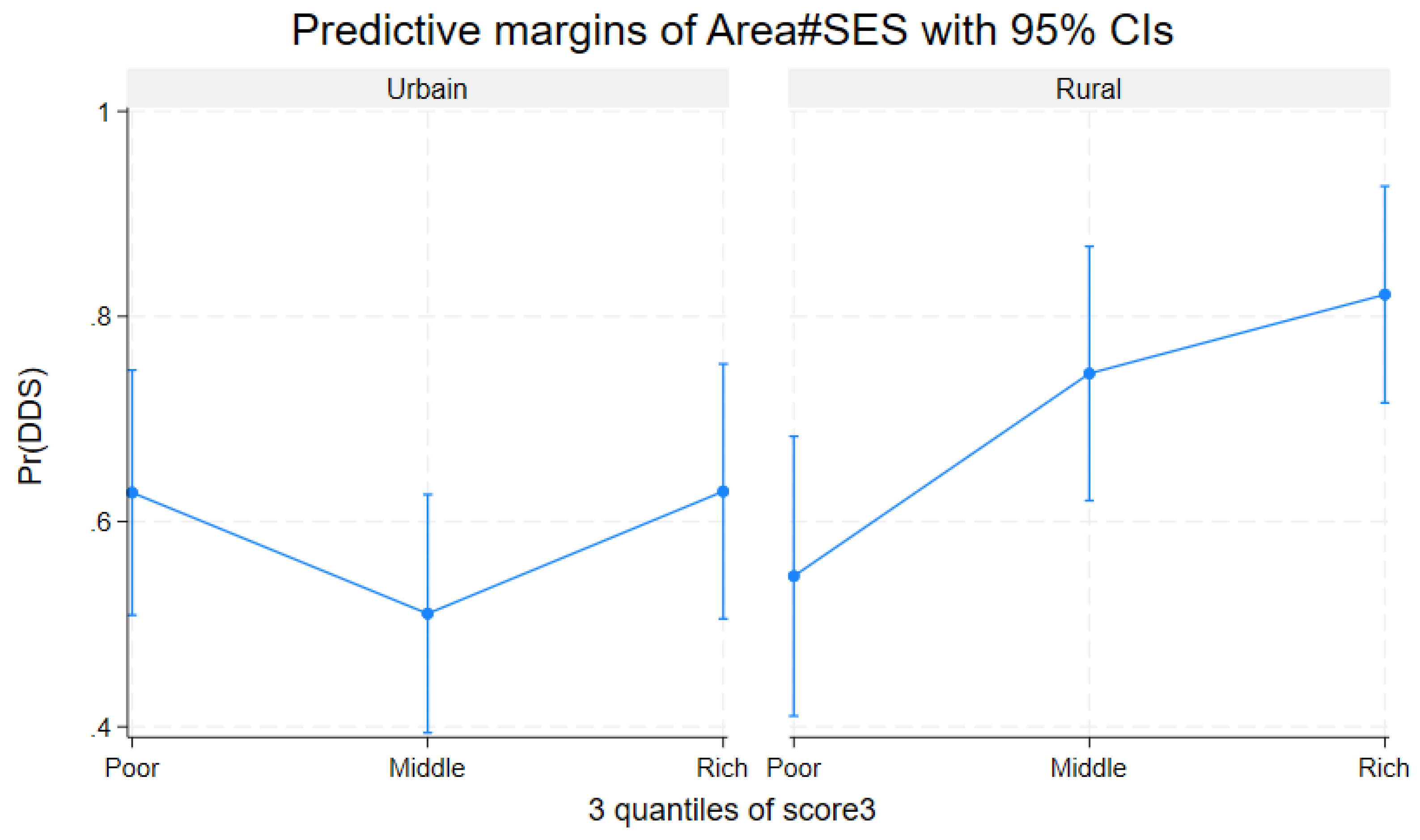

3.2.2. Predicted Probabilities and Interaction Analyses

3.2.3. Model Performance and Diagnostics

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vollmer S, Laillou A, Albers N, Nanama S. Measuring child food poverty : understanding the gap to achieving minimum dietary diversity. Public Health Nutr. 2025 Jan 8 ;28(1) : e27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- George CM, Coglianese N, Bauler S, Perin J, Kuhl J, Williams C, Kang Y, Thomas ED, François R, Ng A, Presence AS, Jean Claude BR, Tofail F, Mirindi P, Cirhuza LB. Low dietary diversity is associated with linear growth faltering and subsequent adverse child developmental outcomes in rural Democratic Republic of the Congo (REDUCE program). Matern Child Nutr. 2022 Jul ;18(3): e13340. Epub 2022 Mar 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raru TB, Merga BT, Mulatu G, Deressa A, Birhanu A, Negash B, Gamachu M, Regassa LD, Ayana GM, Roba KT. Minimum Dietary Diversity Among Children Aged 6-59 Months in East Africa Countries : A Multilevel Analysis. Int J Public Health. 2023 Jun 1 ;68 :1605807. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdulahi A, Shab-Bidar S, Rezaei S, Djafarian K. Nutritional Status of Under Five Children in Ethiopia : A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017 Mar ;27(2) :175-188. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kanté AM, Gutierrez HR, Larsen AM, Jackson EF, Helleringer S, Exavery A, Tani K, Phillips JF. Childhood Illness Prevalence and Health Seeking Behavior Patterns in Rural Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2015 Sep 23 ;15 :951. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Uggla Caroline and Mace Ruth. Parental investment in child health in sub-Saharan Africa : a cross-national study of health-seeking behaviors (2016) R. Soc. Open Sci. 3 150460. [CrossRef]

- Azupogo Fusta, Chipirah J, Halidu Ramatu. The association between dietary diversity and anthropometric indices of children aged 24-59 months: A cross-sectional study in northern Ghana 2022}, Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr;2022 ,10 :22; 20829-20848. [CrossRef]

- Belay DG. Determinants of Inadequate Minimum Dietary Diversity Intake Among Children Aged 6 – 23 Months in Sub-Saharan Africa: Pooled Prevalence and Multilevel Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey in 33 Sub-Saharan African Countries. frontiers in nutrition ,2022;9(July):1–16.

- Paulo HA, Andrew J, Luoga P, Omary H, Chombo S, Mbishi JV, Addo IY. Minimum dietary diversity behaviour among children aged 6 to 24 months and their determinants : insights from 31 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. BMC Nutr. 2024 Dec 18 ;10(1) :160. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gassara G, Chen J. Household Food Insecurity, Dietary Diversity, and Stunting in Sub-Saharan Africa : A Systematic Review. Nutriments 2021, 13(12), 4401. [CrossRef]

- FAO and WHO. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: definitions and measurement methods. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018389 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- UNICEF. The State of the World's Children 2023: Nutrition for Every Child. https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2023 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Global Nutrition Report. Profile of the Democratic Republic of Congo. https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-of-the-congo (accessed on 01 August 2025).

- Bangelesa F, Hatløy A, Mbunga BK, Mutombo PB, Matina MK, Akilimali PZ, Paeth H, Mapatano MA. Is stunting in children under five associated with the state of vegetation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo ? Secondary analysis of Demographic Health Survey data and the satellite-derived leaf area index. Heliyon. 2023 Feb 3 ;9(2) : e13453. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- George CM, Coglianese N, Bauler S, Perin J, Kuhl J, Williams C, Kang Y, Thomas ED, François R, Ng A, Presence AS, Jean Claude BR, Tofail F, Mirindi P, Cirhuza LB. Low dietary diversity is associated with linear growth faltering and subsequent adverse child developmental outcomes in rural Democratic Republic of the Congo (REDUCE program). Matern Child Nutr. 2022 Jul ;18(3):e13340. Epub 2022 Mar 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Niken V, Nur D, Nugroho D, Anjani G. Socio-demographics, dietary diversity score, and nutritional status of children aged 2–5 years : A cross-sectional study of Indonesian coastal areas. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal [Internet]. 2024 ;27(Septembre 2023) :101599. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food and nutrition security in urban Africa: case study of Kinshasa. 2024. https://www.fao.org/publications/en/ (accessed on 2 Jun 2025).

- Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for measuring household food access: Indicator Guide VERSION 2. Nutritional Assistance Project, Academy for Development and Education [Internet]. 2006;14p. Available from: www.fantaproject.org.

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development; Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; WHO Child Growth Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 51.

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; Version 3; FHI360/FANTA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- UNICEF. Tools—UNICEF MICS. 2023. Available online: https://mics.unicef.org/tools (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- UNICEF. The Early Childhood Development Index 2030: A New Measure of Early Childhood Development; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ECDI2030_Technical_Manual_Sept_2023.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Petrowski N, de Castro F, Davis-Becker S, Gladstone M, Lindgren Alves CR, Becher Y, Grisham J, Donald K, van den Heuvel M, Kandawasvika G, Maqbool S, Tofail F, Xin T, Zeinoun P, Cappa C. Establishing performance standards for child development: learnings from the ECDI2030. J Health Popul Nutr. 2023 Dec 12;42(1):140. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Woldegebriel AG, Desta AA, Gebreegziabiher G, Berhe AA, Ajemu KF, Woldearegay TW. Dietary Diversity and Associated Factors among Children Aged 6-59 Months in Ethiopia: Analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016 (EDHS 2016). Int J Pediatr. 2020 Aug 21; 2020:3040845. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bliznashka L, Perumal N, Yousafzai A, Sudfeld C. Diet and development among children aged 36-59 months in low-income countries. Arch Dis Child. 2022 Aug;107(8):719-725. Epub 2021 Dec 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yunhee Kang, Rebecca A Heidkamp, Kudakwashe Mako-Mushaninga, Aashima Garg, Joan N Matji, Mara Nyawo, Hope C Craig, Andrew L Thorne-Lyman. Factors associated with diet diversity among infants and young children in the Eastern and Southern Africa region. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2023;19(3): e13487. [CrossRef]

- Birhanu H, Gonete KA, Hunegnaw MT, Aragaw FM. Minimum acceptable diet and associated factors among children aged 6-23 months during fasting days of orthodox Christian mothers in Gondar city, North West Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 2022 Aug 10 ;8(1):76. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Armdie AZ, Fenta EH, Shiferaw S. The effect of mothers and caregivers' fasting status on the dietary diversity of children 6-23 months : A longitudinal study in Debrebirhan, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2022 Feb 24 ;17(2) : e0264164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumera G, Tsedal E, Ayana M. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children of Orthodox Christian mothers/caregivers during the fasting season in Dejen District, North West Ethiopia. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2018 Feb 14 ;15 :16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ndovie P, Geresomo N, Nkhata SG, Pakira L, Chabwera M, Millongo F, Nyau V. Exploring the determinants of undernutrition among children aged 6-59 months old in Malawi : Insights on religious affiliation, ethnicity, and nutritional status using the 2015-2016 Malawi demographic and health survey. Nutrition. 2026 Jan;141:112922. Epub 2025 Aug 5. Headey D. Remoteness, urbanization, and child nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy. 2017 ; 67 :64–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headey D. Remoteness, urbanization, and child nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy. 2017 ; 67 :64–77.

- Harvey CM, Newell ML, Padmadas SS. Socio-economic differentials in minimum dietary diversity among young children in South-East Asia: evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Nov;21(16):3048-3057. Epub 2018 Sep 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Briaux J, Martin-Prevel Y, Carles S, Fortin S, Kameli Y, Adubra L, Renk A, Agboka Y, Romedenne M, Mukantambara F, Van Dyck J, Boko J, Becquet R, Savy M. Evaluation of an unconditional cash transfer program targeting children's first-1,000-days linear growth in rural Togo : A cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2020 Nov 17 ;17(11) : e1003388. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jef L. Leroya; Marie Ruelb; Ellen: The impact of conditional cash transfer programmes /on child nutrition. https://globalepri.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/07/Leroy2009TheImpactofConditionalCashTransferProgrammesonChildNutrition.pdf.

- Hearst MO, Wells L, Hughey L, Makhoul Z. Household Dietary Diversity among Households with and without Children with Disabilities in Three Low-Income Communities in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 28;20(3):2343. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khonje, MG, Ricker-Gilbert, J., Muyanga, M., & Qaim, M. (2022). Agricultural production diversity and nutrition of children and adolescents in rural sub-Saharan Africa: a multinational longitudinal study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(5), e391–e399.

| Foods groups | n (total=348) or Mean (SD) | % |

| Seeds, roots, and tubers | 267 | 76.72 |

| Foods rich in vitamin A | 248 | 72.26 |

| Fruits and vegetables | 237 | 68.10 |

| Meat, poultry, and fish | 260 | 74.71 |

| Eggs | 70 | 20.21 |

| Legumes and pod vegetables | 146 | 41.95 |

| Milk and dairy products | 189 | 54.31 |

| Oils and fats | 252 | 72.41 |

| DDS continu (mean± SD) | 4.795 ± 2.281 | 100 |

| Characteristics |

Total (column) n (%) |

Dietary diversity (row) | ||

|

Adequate n (%) |

Inadequate n (%) |

p-value | ||

| 348 (100.00) | 221 (63.51) | 127 (36.49) | ||

| Children’s characteristics | ||||

| Gender | 0.831 | |||

| Boy | 178 (51.15) | 114 (64.04) | 64 (35.96) | |

| Girl | 170 (48.85) | 107 (62.94) | 63 (37.06) | |

| Age (in months) | 0.079 | |||

| 24 – 35 | 134 (38.51) | 76 (56.72) | 58 (43.28) | |

| 36 – 46 | 124 (35.63) | 81 (65.32) | 43 (34.68) | |

| 47 – 59 | 90 (25.86) | 64 (71.11) | 26 (28.89) | |

| Preschool education | 0.399 | |||

| No | 251 (72.13) | 156 (62.15) | 95 (37.85) | |

| Yes | 97 (27.87) | 65 (67.01) | 32 (32.99) | |

| Early childhood development | 0.282 | |||

| Not on track | 103 (29.60) | 61 (59.22) | 42 (40.78) | |

| On track | 245 (70.40) | 160 (65.31) | 85 (34.69) | |

| Stunting (n=313) | 0.810 | |||

| Yes | 38 (12.14) | 23 (60.53) | 15 (39.47) | |

| No | 275 (87.86) | 172 (62.55) | 103 (37.45) | |

| Parents or caregivers’ Characteristics | ||||

| Age (in years) * | 0.019 | |||

| < 30 | 131 (37.64) | 73 (55.73) | 58 (44.27) | |

| ≥ 30 | 217 (62.36) | 148 (68.20) | 69 (31.80) | |

| Gender | 0.261 | |||

| Male | 33 (9.48) | 18 (54.55) | 15 (45.45) | |

| Female | 315 (90.52) | 203 (64.44) | 112 (35.56) | |

| Education level | 0.471 | |||

| Low | 142 (40.80) | 87 (61.27) | 55 (38.73) | |

| Secondary school or above | 206 (59.20) | 134 (65.05) | 72 (34.95) | |

| Occupation | 0.858 | |||

| Unemployed | 56 (16.09) | 34 (60.71) | 22 (39.29) | |

| Housewife | 78 (22.41) | 51 (65.38) | 27 (34.62) | |

| Employee | 214 (61.49) | 136 (63.55) | 78 (36.45) | |

| Religion* | 0.048 | |||

| No religion | 4 (1.15) | 1(25.00) | 3 (75.00) | |

| Christian | 316 (90.80) | 207 (65.51) | 109 (34.49) | |

| Muslim | 1 (0.29) | 1 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Local/Traditional | 27 (7.76) | 12(44.44) | 15 (55.56) | |

| Marital status* | 0.049 | |||

| Alone | 86 (24.71) | 47(54.65) | 39 (45.35) | |

| Married/in union | 262 (75.29) | 174 (69.41) | 88 (33.59) | |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Household size | 0.564 | |||

| < 6 | 141 (40.52) | 87 (61.70) | 54 (38.30) | |

| ≥ 6 | 207 (59.48) | 134 (64.73) | 73 (32.27) | |

| Area * | 0.035 | |||

| Urban | 199 (57.18) | 117 (58.79) | 82 (41.21) | |

| Rural | 149 (42.82) | 104 (69.80) | 45 (30.20) | |

| Socioeconomic status* | 0.040 | |||

| Poor | 116 (33.33) | 66 (56.90) | 50 (43.10) | |

| Middle | 116 (33.33) | 71 (61.21) | 45 (38.79) | |

| Rich | 116 (33.33) | 84 (72.41) | 32 (27.59) | |

| Food security level | 0.123 | |||

| Food insecurity | 287 (82.47) | 177 (61.67) | 110 (38.33) | |

| Food security | 61 (17.53) | 44 (72.13) | 17 (27.87) | |

| Number of meals per day | 0.801 | |||

| < 3 | 277 (79.60) | 175 (63.18) | 102 (36.82) | |

| ≥ 3 | 71 (20.40) | 46 (64.79) | 25 (35.21) | |

| Variable | aOR | CI 95% | p-Value |

| Child age (24–35 months = ref) * | |||

| 36 - 47 months | 1.48 | 0.85–2.56 | 0.161 |

| 48 - 59 months | 1.87 | 1.02–3.43 | 0.043 |

| Parent or caregiver age (under 30 years = ref) | |||

| 30 years and above | 149 | 0.91–2.44 | 0.108 |

| Marital status (alone = ref) | |||

| Married or in union | 1.37 | 0.79–2.36 | 0.260 |

| SES (poor = ref) * | |||

| Middle | 1.12 | 0.63–2.01 | 0.685 |

| Rich | 1.88 | 1.003–3.51 | 0.049 |

| Area (Urbain=ref) * | |||

| Rural | 1.65 | 1.02–2.66 | 0.040 |

| Religion (Local/tradition=ref) * | |||

| No religion | 0.47 | 0.05–4.24 | 0.503 |

| Christian | 2.50 | 1.02–6.10 | 0.044 |

| Muslim | 1 | ||

| Food Security (Severate food insecurity=ref) | |||

| Food security | 1.24 | 0.61–2.52 | 0.543 |

| Low food insecurity | 0.74 | 0.28–1.93 | 0.542 |

| Moderate food insecurity | 0.92 | 0.51–1.63 | 0.764 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).