Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

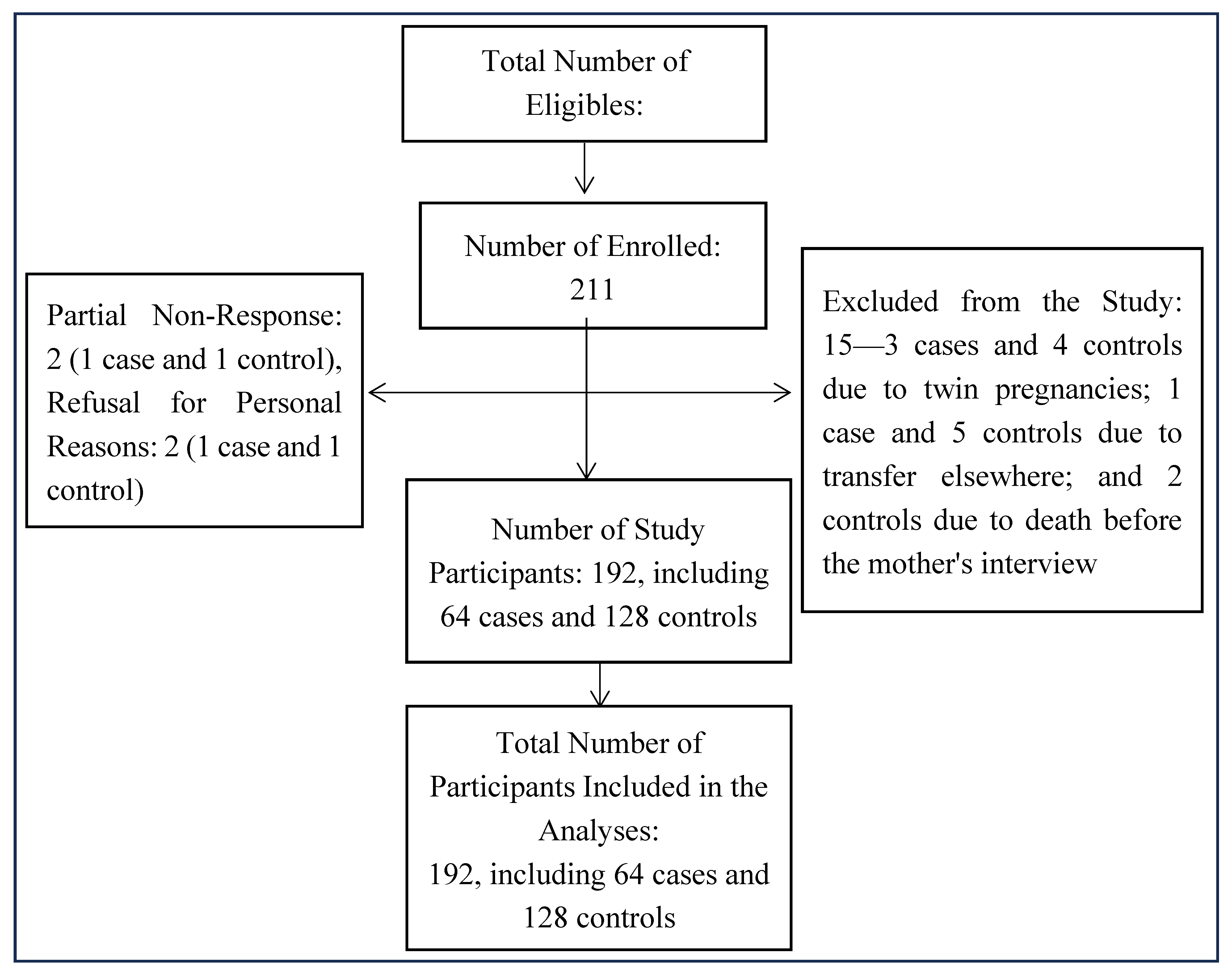

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

2.2. Sampling and Sample Size

2.3. Case and Control Definitions and Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria

- Exclusion criteria:

2.4. Recruitment Procedure for Eligible Subjects

2.5. Exposures and Covariates

- Main exposure: Maternal dietary diversity was measured using the Diet Quality Questionnaire (DQQ), dietary diversity score (DDS; number of distinct food groups consumed), and the minimum binary dietary diversity for women (MDD-W, DDS ≥ 5).

-

Other exposures/covariates:

- -

- Sociodemographic and economic data: maternal age (years), maternal education, marital status, maternal education level, maternal occupation, husband’s smoking status at home, and household wealth index, food security, unintended pregnancy, and facility identifier;

- -

- Maternal obstetric and health characteristics: parity, history of LBW, number of prenatal care visits (PCCs), maternal smoking status, gestational age at first PC, iron folate supplementation, hemoglobin level (mg/dL), blood pressure (mm Hg), HIV status, malaria during pregnancy;

- -

- Maternal nutritional characteristics and behavior: prior nutrition education, maternal height (cm), mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC, in mm), maternal weight in the first, second, and third trimesters of pregnancy (in kg), intermittent preventive treatment (IPT), number of IPT doses, and maternal alcohol consumption.

2.6. Data Collection

- The mothers were interviewed to collect sociodemographic data, maternal dietary diversity, lifestyle, prenatal follow-up, maternal history, and pregnancy intention.

- Medical records (partogram and prenatal consultation form) were used to triangulate specific data collected during the interview and to collect data on the child’s birth weight, gestational age, prenatal visits, IPT for malaria, last-trimester hemoglobin (Hb) level (measured using a hemoglobinometer), and malaria, which was assessed using a thick drop test in the laboratory. Self-reports were cross-referenced with prenatal records.

- Direct measurements: Maternal anthropometry (height (cm), measured using a height chart; mid-upper arm circumference, measured using the MUAC, with a threshold of 230 mm).

-

Dietary diversity measurement: Maternal dietary diversity was measured using two complementary methods.

- -

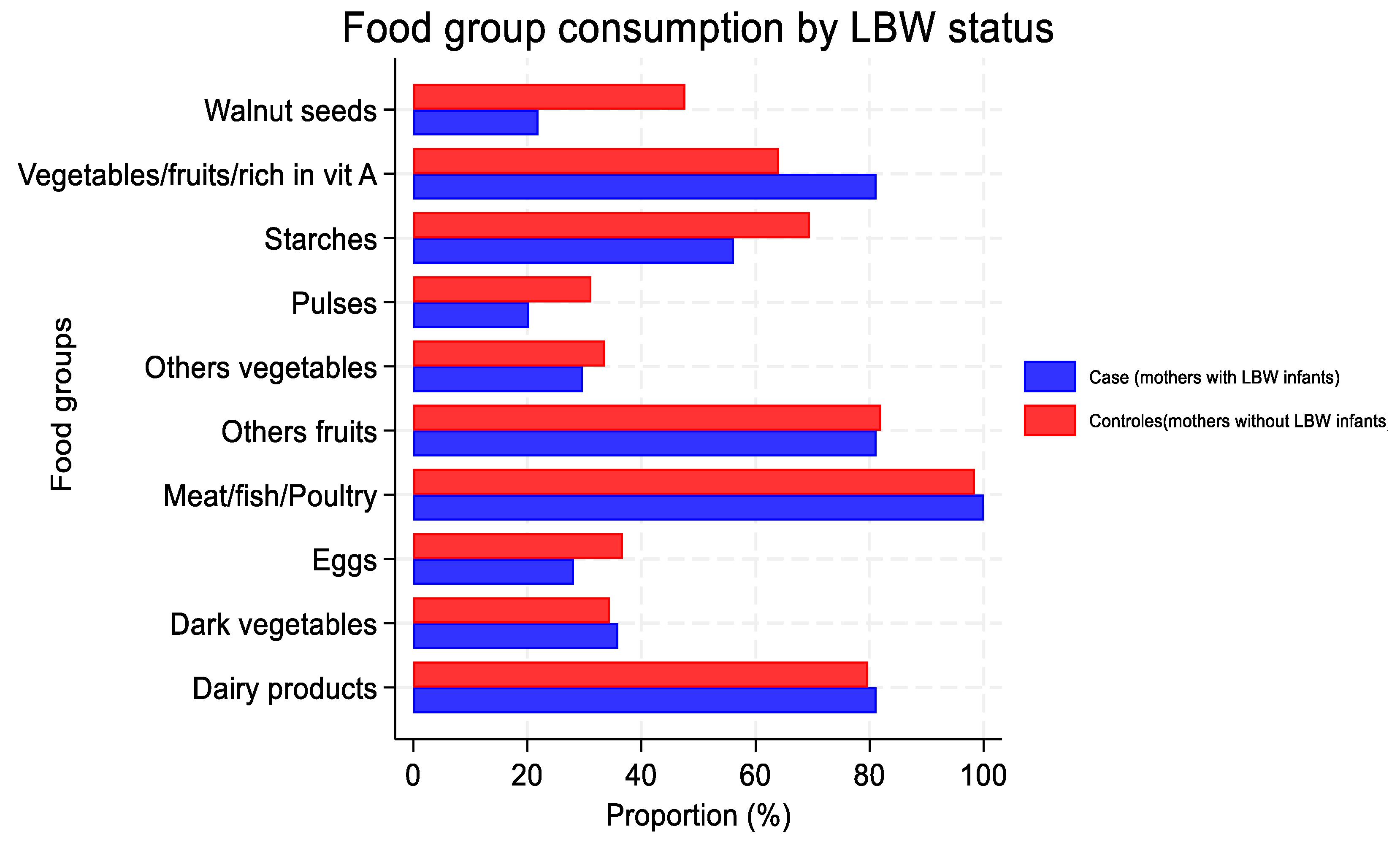

- Maternal dietary diversity was determined from the Diet Quality Questionnaire (DQQ), which was adapted to the DRC context, and enabled a qualitative recall of consumption over the last 24 h (MDD-W, FAO/WHO). The 10 food groups were (1) basic starchy foods; (2) legumes; (3) nuts/seeds; (4) dairy products; (5) meat products; (6) eggs; (7) dark green leafy vegetables; (8) other fruits/vegetables rich in vitamin A; (9) other vegetables; and (10) other fruits. A composite women’s dietary diversity score (SDAF) was calculated based on the number of food groups consumed by each mother, with a scale ranging from 0 (no consumption) to 10 (consumption of all groups). A score of ≥5 groups is considered to indicate adequate dietary diversity, while a score of <5 groups reflects inadequate dietary diversity [26].

- -

- Weekly recall (modified MDD-W): Using a qualitative recall of food-group consumption (MDD-W, modified FAO), the frequency of habitual consumption of food groups ≥ 3 times per week was assessed. A composite women’s dietary diversity score (SDAF) was adapted according to the country context, with a scale ranging from 0 (no consumption) to 9 (consumption of all groups). A score of ≥5 is considered to indicate adequate dietary diversity, while a score of <5 reflects inadequate dietary diversity [12].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Dietary Diversity

3.3. Food-Group Consumption

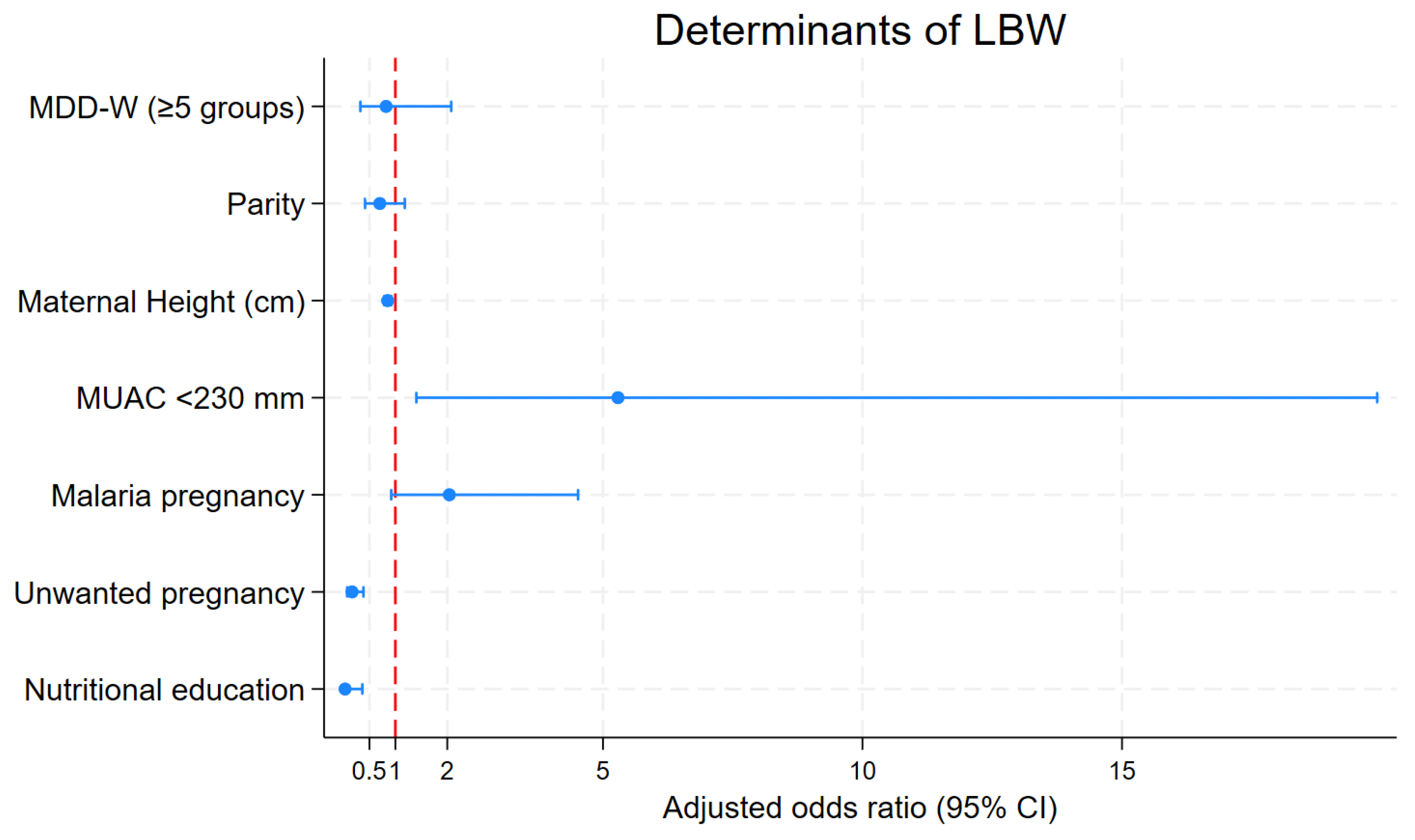

3.4. Determinants of Low Birth Weight

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Implications

4.2. Addressing Malaria and Other Determinants

4.3. Recommendations for Policy and Practice

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; UNICEF. Estimates of Low Birthweight: Levels and Trends 2000–2015; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mare, K.U.; Andarge, G.G.; Sabo, K.G.; Mohammed, O.A.; Mohammed, A.A.; Moloro, A.H.; Ebrahim, O.A.; Seifu, B.L.; Kase, B.F.; Demeke, H.S.; et al. Regional and Subregional Estimates of Low Birthweight and Its Determinants in 44 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Data from Demographic and Health Surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; Lee, S.E.; Donahue Angel, M.; Adair, L.S.; Arifeen, S.E.; Ashorn, P.; Barros, F.C.; Fall, C.H.; Fawzi, W.W.; Hao, W.; et al. Risk of childhood undernutrition related to small-for-gestational age and preterm birth in low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1340–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cutland, C.L.; Lackritz, E.M.; Mallett-Moore, T.; Bardají, A.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Lahariya, C.; Nisar, M.I.; Tapia, M.D.; Pathirana, J.; Kochhar, S.; et al. Low birth weight: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine 2017, 35 Pt A, 6492–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seid, A.; Dugassa Fufa, D.; Weldeyohannes, M.; Tadesse, Z.; Fenta, S.L.; Bitew, Z.W.; Dessie, G. Inadequate dietary diversity during pregnancy increases the risk of maternal anemia and low birth weight in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 3706–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Planning and Monitoring the Implementation of the Revolution of Modernity (MPSMRM); Ministry of Public Health (MSP); ICF International. Demographic and Health Survey in the DRC 2013-2014; MPSMRM: Rockville, MA, USA; MSP: Rockville, MA, USA; ICF International: Rockville, MA, USA, 2014.

- Mushagalusa, F.T.; Mungo, O.M.; Kambale, A.M.; Iragi, F.M.; Baguma, M.B.; Niyukuri, A.M.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of low birth weight in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2024, 47, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Cespedes, E.M.; Hu, F.B. Dietary patterns: From nutritional epidemiologic analysis to national guidelines. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 899–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; FHI 360. Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women: A Measurement Guide; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zerfu, T.A.; Umeta, M.; Baye, K. Dietary diversity during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of maternal anemia, preterm delivery, and low birth weight in a prospective cohort study in rural Ethiopia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melaku, Y.A.; Gill, T.K.; Taylor, A.W.; Adams, R.; Shi, Z. Associations entre la diversité alimentaire et le syndrome métabolique et ses composantes en Australie-Méridionale. Santé Publique Nutr. 2018, 21, 2072–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchenbecker, J.; Reinbott, A.; Mtimuni, B.; Krawinkel, M.B.; Jordan, I. Nutrition education improves dietary diversity of children 6-23 months at community-level: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in Malawi. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung AS, Yaqub N, Lattof SR, Strong J, Maliqi B. Private sector quality interventions to improve maternal and newborn health in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1332612. Published 2025 Apr 9. [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; Stewart, C.P. Maternal micronutrient deficiency, fetal development, and the risk of chronic disease. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrimpton, R. Global policy and programme guidance on maternal nutrition: What exists, the mechanisms for providing it, and how to improve them? Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26 (Suppl. 1), 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belete, N.K.; Belete, A.G.; Assefa, D.T.; Sorrie, M.B.; Teshale, M.Y. Effects of maternal anemia on low-birth-weight in Sub-Sahara African countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- UrbanBirth Collective. Improving complex health systems and lived environments for maternal and perinatal well-being in urban sub-Saharan Africa: The UrbanBirth Collective. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kibombi, W.I. Maternal responsibility in clandestine abortions of their underage daughters in Kinkenda at the Luka camp, DR Congo. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Sci. Stud. 2024, 3, 3482–3499. Available online: https://www.ijssass.com/index.php/ijssass/article/view/256 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- FAO; European Union; CIRAD. Food Systems Profile–Democratic Republic of Congo. Enabling the sustainable and inclusive transformation of our food systems. Rome, Brussels, and Montpellier, France. 2022.

- Muzinga, M.S.; Leopard City Development Policy. Luka Camp in the Ngaliema Commune. 2018. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/797074583/TP-analyse-de-Camp-Luka (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Review of Urbanization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Productive and Inclusive Cities for the Emergence of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. 2018. Available online: https://documents.banquemondiale.org/fr/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/82983153426354100325 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Unicef. State of the World’s Children 2019. Children. Food and Nutrition. 2019. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/state-of-the-worlds-children-2019/24 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Girma, S.; Fikadu, T.; Agdew, E.; Haftu, D.; Gedamu, G.; Dewana, Z.; Getachew, B. Factors associated with low birthweight among newborns delivered at public health facilities of Nekemte town. West Ethiopia: A case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DQQ Overview. Guide I. Diet Quality Questionnaire (DQQ) Indicator Guide. 2023; Volume 4, pp. 1–14. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/722118215/DQQ-Indicator-Guide-2023 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Madzorera, I.; Isanaka, S.; Wang, M.; Msamanga, G.I.; Urassa, W.; Hertzmark, E.; Duggan, C.; Fawzi, W.W. Maternal dietary diversity and dietary quality scores in relation to adverse birth outcomes in Tanzanian women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kheirouri, S.; Alizadeh, M. Maternal dietary diversity during pregnancy and risk of low birth weight in newborns: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4671–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, N.; Kishore, J.; Gupta, M.; Singla, H.; Dayma, R.; Sharma, J.B. The Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD-W) Score: Its Association With the Prevalence and Severity of Anemia in Pregnancy. Cureus 2024, 16, e66248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Geta, T.G.; Gebremedhin, S.; Abdiwali, S.A.; Omigbodun, A.O. Dietary diversity and other predictors of low birth weight in Gurage Zone. Ethiopia: Prospective study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilunga, P.M.; Mukuku, O.; Mawaw, P.M.; Mutombo, A.M.; Lubala, T.K.; Shongo Ya Pongombo, M.; Kakudji Luhete, P.; Wembonyama, S.O.; Mutombo Kabamba, A.; Luboya Numbi, O. Risk factors for low birth weight in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Med. Sante Trop. 2016, 26, 386–390. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshinzobe, J.C.K.; Ngaya, D.K. Case-control study of factors associated with low birth weight at the Kingasani Hospital Center. Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo). Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapil, S.; Ververs, M. Maternal Mid-Upper Arm Circumference: Still Relevant to Identify Adverse Birth Outcomes in Humanitarian Contexts? Volume 70, 28 September 2023. Available online: https://www.ennonline.net/fex/70/en/maternal-mid-upper-arm-circumference-still-relevant-identify-adverse-birth-outcomes (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Bilal, J.A.; Rayis, D.A.; AlEed, A.; Al-Nafeesah, A.; Adam, I. Maternal Undernutrition and Low Birth Weight in a Tertiary Hospital in Sudan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 927518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuki, N.; Katz, J.; Lee, A.C.; Vogel, J.P.; Silveira, M.F.; Sania, A.; Stevens, G.A.; Cousens, S.; Caulfield, L.E.; Christian, P.; et al. Short Maternal Stature Increases Risk of Small-for-Gestational-Age and Preterm Births in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis and Population Attributable Fraction. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2542–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arendt, E.; Singh, N.S.; Campbell, O.M.R. Effect of maternal height on caesarean section and neonatal mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of 34 national datasets. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticona, D.M.; Huanco, D.; Ticona-Rendón, M.B. Impact of unplanned pregnancy on neonatal outcomes: Findings of new high-risk newborns in Peru. Int. Health 2024, 16, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Tintelen, A.M.G.; Jansen, D.E.M.C.; Bolt, S.H.; Warmelink, J.C.; Verhoeven, C.J.; Henrichs, J. The Association Between Unintended Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Low-Risk Pregnancies: A Retrospective Registry Study in the Netherlands. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2024, 69, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibaba YFantahun MHindin, M.J. The association of unwanted pregnancy and social support with depressive symptos in pregnancy: Evidence from rural Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chalasani, S.; Koenig, M.A.; Mahapatra, B. The consequences of unintended births for maternal and child health in India. Popul. Stud. 2012, 66, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; Shamsipour, M.; Yunesian, M.; Hassanvand, M.S.; Agordoh, P.D.; Seidu, M.A.; Fotouhi, A. Prenatal malaria exposure and risk of adverse birth outcomes: A prospective cohort study of pregnant women in the Northern Region of Ghana. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Satapathy, P.; Khatib, M.N.; Gaidhane, S.; Zahiruddin, Q.S.; Sharma, R.K.; Rustagi, S.; Al-Jishi, J.M.; Albayat, H.; Al Fares, M.A.; Garout, M.; et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in maternal malarial infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 62, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Case (n = 64) n (%) |

Control (n = 128) n (%) |

Total (n = 192) n (%) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution of mothers by sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Mother’s age (years) (mean ± SD) | 25.98 ± 5.21 | 28.35 ± 5.65 | 27.56± 5.61 | 0.0056 |

| Age group (years) | 0.127 | |||

| Less than 25 | 22 (34.38) | 33 (25.78) | 55 (28.65) | |

| 25–34 | 39 (60.94) | 78 (60.94) | 117 (60.94) | |

| 35 and above | 3 (4.69) | 17 (13.28) | 20 (10.42) | |

| Education level | 0.007 | |||

| Below secondary school | 27 (42.19) | 30 (23.44) | 57 (29.69) | |

| Secondary school and above | 37 (57.81) | 98 (76.56) | 135 (70.31) | |

| Marital status | 0.001 | |||

| Single | 17 (26.56) | 10 (7.81) | 27 (14.06) | |

| Married/in union | 46 (71.88) | 118 (92.19) | 164 (85.42) | |

| Others | 1 (1.56) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.52) | |

| Occupation | 0.032 | |||

| Housewife | 40 (62.50) | 76 (59.38) | 116 (60.42) | |

| Unemployed | 11 (17.19) | 9 (7.03) | 20 (10.42) | |

| Employee | 13 (20.31) | 43 (33.59) | 56 (29.17) | |

| Unwanted pregnancy | <0.001 | |||

| No | 32 (50.00) | 22 (17.19) | 54 (28.12) | |

| Yes | 32 (50.00) | 106 (82.81) | 138 (71.88) | |

| Passive smoking | 0.043 | |||

| Yes | 14 (21.88) | 14 (10.94) | 28 (14.58) | |

| No | 50 (78.12) | 114 (89.06) | 164 (85.42) | |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.092 | |||

| Poor | 28 (43.75) | 37(28.91) | 65 (33.85) | |

| Middle | 26 (40.62) | 59 (46.09) | 85 (44.27) | |

| Rich | 10 (15.62) | 32 (25.00) | 42 (21.88) | |

| Food security level | 0.123 | |||

| Food insecurity | 41(64.06) | 67 (52.34) | 108 (56.25) | |

| Food security | 23 (35.94) | 61 (47.66) | 84 (43.75) | |

| Mother’s obstetrics and health-related characteristics | ||||

| Number of ANC | 0.006 | |||

| <4 | 33 (51.56) | 40 (31.25) | 73 (38.02) | |

| ≥4 | 31 (48.44) | 88 (68.75) | 119 (61.98) | |

| Pregnancy age at 1st ANC (week) | 0.186 | |||

| Over 16 | 49 (76.56) | 108 (84.38) | 157 (81.77) | |

| Before 16 | 15 (23.44) | 20 (15.62) | 35 (18.23) | |

| History of malaria during pregnancy | 0.024 | |||

| Yes | 43 (67.19) | 64 (50.00) | 107 (55.73) | |

| No | 21 (32.81) | 64 (50.00) | 85 (44.27) | |

| Hemoglobin level (mg/dL) | 0.019 | |||

| <12 | 38 (59.38) | 53 (41.41) | 91 (47.40) | |

| ≥12 | 26 (40.62) | 75 (58.59) | 101 (52.60) | |

| Number of previous births (parity) | <0.001 | |||

| Primiparous | 35 (54.69) | 33 (25.78) | 68 (35.42) | |

| 2–3 | 24 (37.50) | 71 (55.47) | 95 (49.48) | |

| Over 3 | 5 (7.81) | 24 (18.75) | 29 (15.10) | |

| History of low birth weight | 0.504 | |||

| Yes | 8 (12.50) | 12 (9.38) | 20 (10.42) | |

| No | 56 (87.50) | 116 (90.62) | 172 (89.58) | |

| History of hypertension | 0.586 | |||

| Yes | 3 (4.69) | 4 (3.12) | 7 (3.65) | |

| No | 61 (95.31) | 124 (96.88) | 185 (96.35) | |

| Mother’s nutritional and behavioral factor characteristics | ||||

| Mother’s height (cm) | 0.200 | |||

| <150 | 3 (4.69) | 2 (1.56) | 5 (2.60) | |

| ≥150 | 61 (95.31) | 126 (98.44) | 187 (97.40) | |

| Maternal MUAC (mm) | <0.001 | |||

| <230 | 14 (21.88) | 5 (3.91) | 19 (9.90) | |

| ≥230 | 50 (78.12) | 123 (96.09) | 173 (90.10) | |

| Nutritional education | ||||

| No | 8 (12.50) | 1 (0.78) | 9 (4.69) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 56 (87.50) | 127 (99.22) | 183 (95.31) | |

| Have you ever taken IPT | 0.294 | |||

| Yes | 56 (87.50) | 118 (92.19) | 174 (90.62) | |

| No | 8 (12.50) | 10 (7.81) | 18 (9.38) | |

| How many times have you taken | 0.123 | |||

| No | 8 (12.50) | 10 (7.81) | 18 (9.38) | |

| Less than 3 | 51 (79.69) | 95 (74.22) | 146 (76.04) | |

| 3 and above | 5 (7.81) | 23 (17.97) | 28 (14.58) | |

| Have you ever drunk alcohol | 0.225 | |||

| Yes | 18 (28.12) | 26 (20.31) | 44 (22.92) | |

| No | 46 (71.88) | 102 (79.69) | 148 (77.08) | |

| Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD-W 24 h recall) | ||||

| Inadequate | 12 (18.75) | 21 (26.41) | 33 (17.19) | 0.685 |

| Adequate | 52 (81.25) | 107 (83.59) | 159 (82.81) | |

| Modified MDD-W (weekly) | <0.001 | |||

| Inadequate | 37 (57.8) | 36 (28.1) | ||

| Adequate | 27 (42.2) | 92 (71.9) |

| Dietary Diversity Indicator | Case (Low Birth Weight, n = 64) | Control (Weight > 2500 g, n = 128) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDS (24 h) mean ± SD | 5.36 ± 1.19 | 5.77 ± 1.37 | 0.0407 |

| Reached MDD-W (24 h) (%) | 81.2% (n = 52) | 83.6% (n = 107) | 0.685 |

| DDS (weekly) mean ± SD | 4.48 ± 1.63 | 5.21 ± 1.31 | <0.001 |

| Reached MDD-W (weekly) | 42.2% (n = 27) | 71.9% (n = 92) | <0.001 |

| Discrepancies (24 h vs. weekly) | 51.6% (n = 33) | 32.0% (n = 41) | 0.009 |

| Variable | Non Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

p-Value | Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD-W (DDS ≥ 5) | 0.85 [0.39–1.86] | 0.685 | 0.82 [0.32–2.07] | 0.678 |

| Parity | 0.67 [0.52–0.87] | 0.002 | 0.70 [0.42–1.18] | 0.182 |

| Maternal Height (cm) | 0.87 [0.82–0.92] | <0.001 | 0.85 [0.79– 0.92] | <0.001 |

| MUAC < 230 mm | 6.89 [2.36–20.14] | <0.001 | 5.29 [1.40–19.91] | 0.014 |

| Malaria during pregnancy | 2.05 [1.09–3.83] | 0.025 | 2.04 [0.92–4.52] | 0.079 |

| Unwanted pregnancy | 0.21 [0.11–0.41] | <0.001 | 0.17 [0.071–0.385] | <0.001 |

| Nutritional education | 0.055 [0.007–0.45] | 0.007 | 0.032 [0.003–0.364] | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).