1. Introduction

Swimming in surface water not designated as bathing water (wild swimming) has been practiced in Europe for a long time and, in recent decades, mainly by trained adults in competition [

1]. Wild swimming by families and groups of adolescents and children is a phenomenon that seems to have increased in the last years [

2,

3]. This growth in popularity has been driven by several factors, including the occurrence of hot summers and the organization of mass sporting events for people of all ages [

3]. The practice of wild swimming is considered beneficial to people's physical and mental well-being [

4,

5,

6]. It also serves to connect people with the region's landscape and nature, and it is regarded as a catalyst for regional and local tourism. Nevertheless, this activity poses various health risks, such as hypothermia, ear infections and gastrointestinal infections [

7]. Health risks increase particularly when recreation occurs in waters containing partially treated sewage from sewage treatment plants (STPs) and untreated sewage from sewer overflows, as these waters are contaminated with enteric pathogenic viruses such as hepatitis A, norovirus, rotavirus, adenoviruses and enteric bacteria such as

Salmonella spp.,

Shigella spp., including bacteria carrying genes for multi-drug resistances, such as expanded spectrum beta-lactamases and carbapenemase-producing

E. coli [

8,

9,

10]. Large groups of people engaged in recreational activities can become ill or infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria [

11,

12,

13]. However, there is limited information available regarding the environmental fate and health risks associated with this contamination. It is a task of governments to regulate and monitor official bathing areas. As a result, there is a lack of data on swimming in other types of water. This exploratory case study focuses on the German-Dutch Vecht(e) catchment in which several outbreaks of stomach and intestinal problems (gastroenteritis, GE) occurred with people swimming in streams and rivers that carry STP effluent and raw sewage. The study discusses the local situation regarding wild swimming, the risk of infection for wild swimmers and the policy implications in terms of toleration of bathing, public information and regular monitoring of pathogens and outbreaks. Finally, an assessment of possible measures was carried out to facilitate policy making and manage the biological risks of wild swimming in general.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Focus

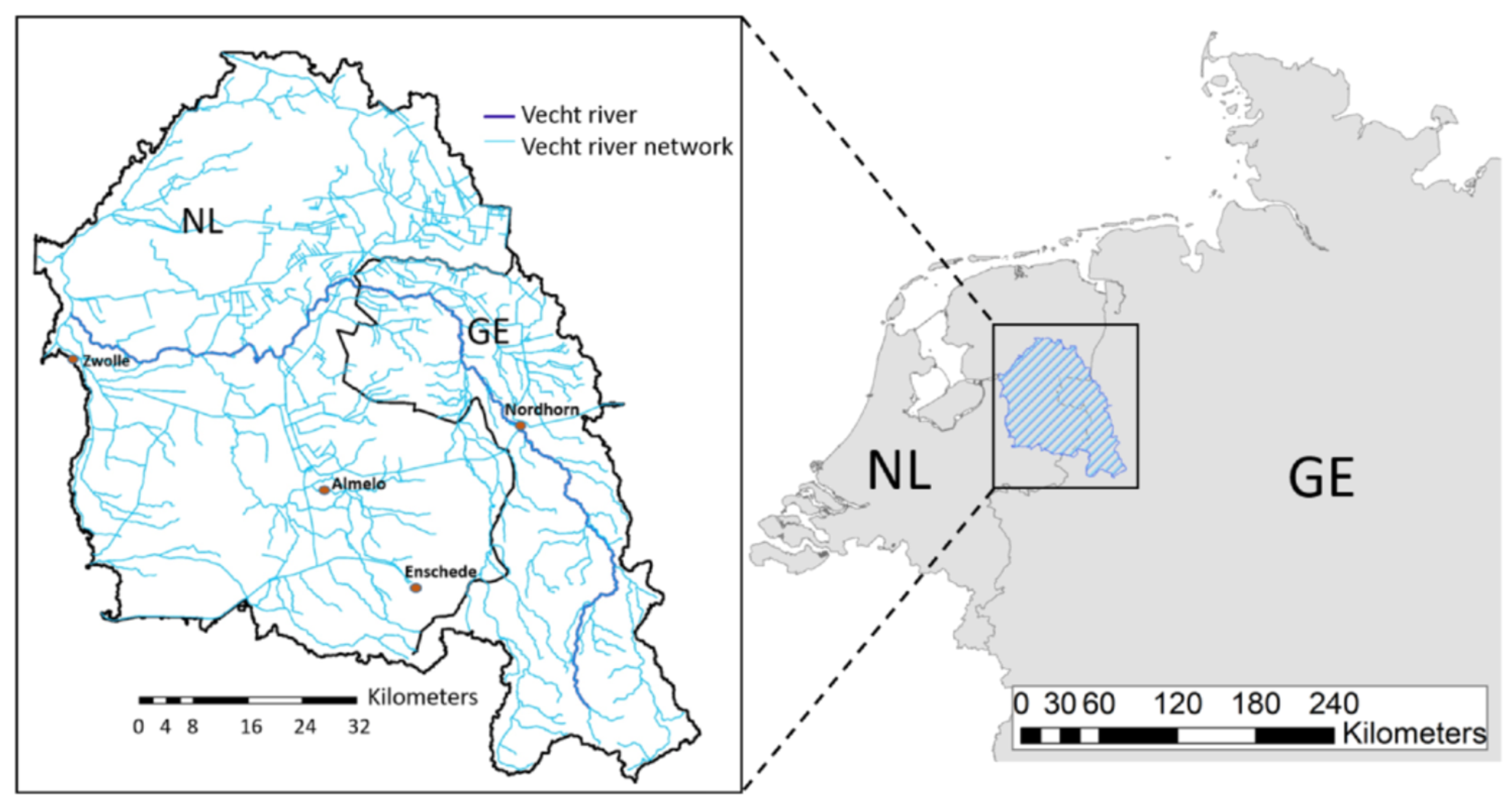

The 6100 km

2 cross-border German-Dutch Vecht river basin was selected as study area (

Figure 1). The focus was on bathing in flowing, effluent-bearing surface waters: streams, rivers, canals and one lake. Lakes and sand pits without flowing water were excluded.

2.2. Working Definition of Wild Swimming

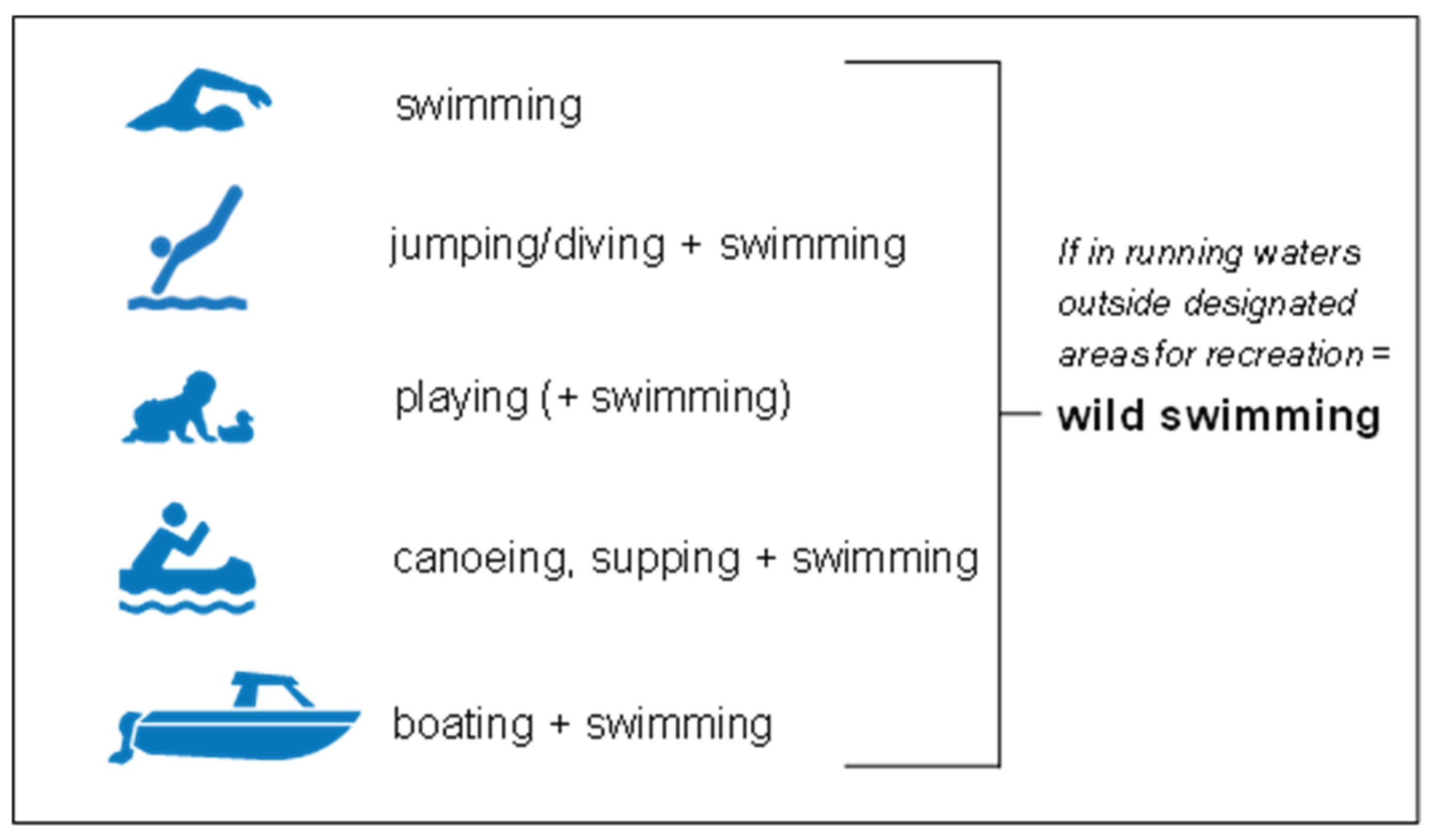

Wild swimming is an internationally used term for year-round swimming in more or less natural waters, and is also called outdoor, open water or natural water swimming. Several categories of recreational activities with varying degrees of water contact were distinguished: swimming, jumping, playing, and canoeing, stand-up paddling, and boating when combined with swimming (

Figure 2). All these activities, when carried out in flowing water outside official bathing areas, were referred to here as wild swimming.

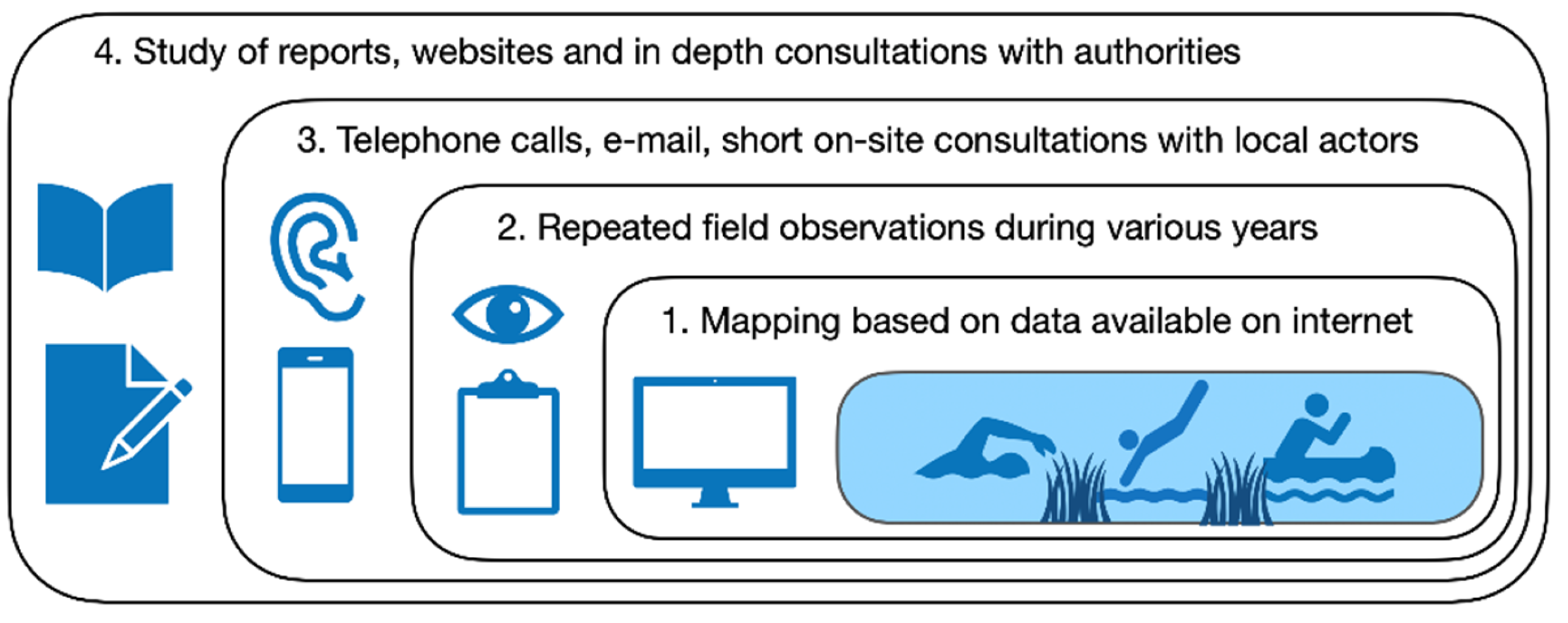

2.3. Mapping of Wild Swimming Sites

To validate the observations several survey methods were applied (method triangulation,

Figure 3). Firstly, to determine which of the waters in the basin were used for wild swimming, old and current swimming sites were mapped using Google, Google Maps and social media. Search terms used were (in Dutch and German): swimming/cooling/recreation in canal/river/stream, open/outdoor/nature/surface water, accompanied by names of local water bodies, villages, cities and the region (Twente/Overijssel). If more than one recent visual evidence (photo or video) was found, or in addition to one visual evidence also a comment that bathing was still a habit at the location, the location was mapped.

2.4. Data Collection

During the hot summer seasons from 2019 to 2021, when temperatures were ≥30°C, data were repeatedly collected from own observations and consultations with campsite managers, boat rental companies and recreational users during field visits in both countries, complemented with telephone calls and e-mail communications. Information was requested on the maximum number of tourists per category of wild swimmer, as well as the frequency of visits. Based on the collected data, conservative final estimates of visitor numbers per site were calculated, taking duplicates into account. Estimates for local bathing sites, which are mainly used by the local population, were more conservative than those for beaches close to campsites.

2.5. Determining of Outbreaks

Information about outbreaks associated with wild swimming from all over the Netherlands (as a reference) and the Vecht river basin was obtained via internet. Waterborne outbreaks are defined according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) as "two or more persons with the same health complaints who had contact with the same recreational water at the same time and place”. Google was used to search for media reports and Google Scholar for scientific literature about outbreaks (possibly) related to wild swimming. The following search terms were used: illness, belly flu, gastroenteritis after swimming. Reports of GE outbreaks in the study area were collected from local stakeholders, regional water authorities, municipal health centres, care centres, general practitioners, and schools.

2.6. Assessment of Policies and Measures

Insight was gained into local developments and policies on wild swimming through direct contact with stakeholders and the study of reports, websites and social media. Based on scientific literature and expert judgement, possible measures were weighed against criteria such as practicality, efficacy, costs and social acceptability.

3. Results

3.1. Wild Swimming Sites and Numbers of Wild Swimmers

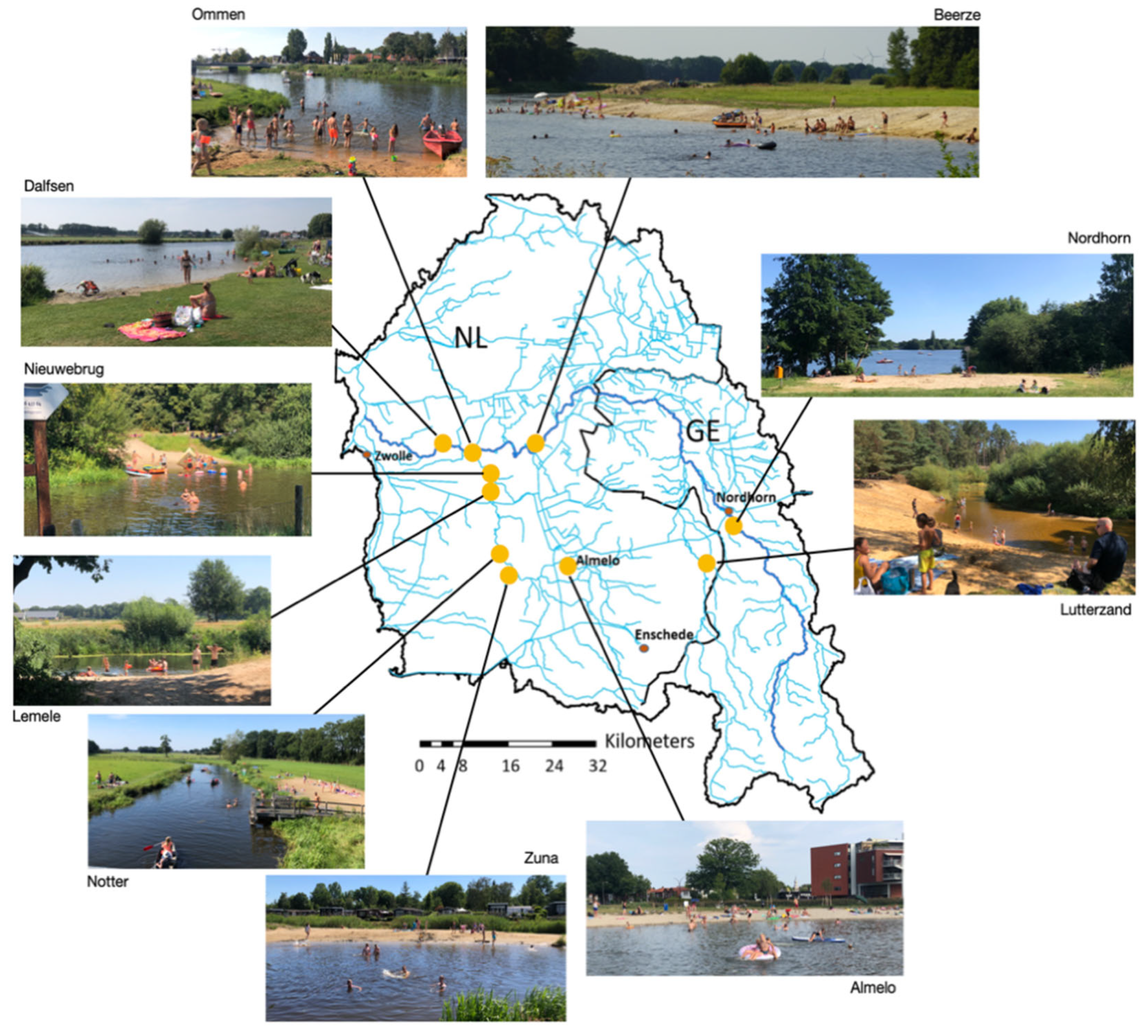

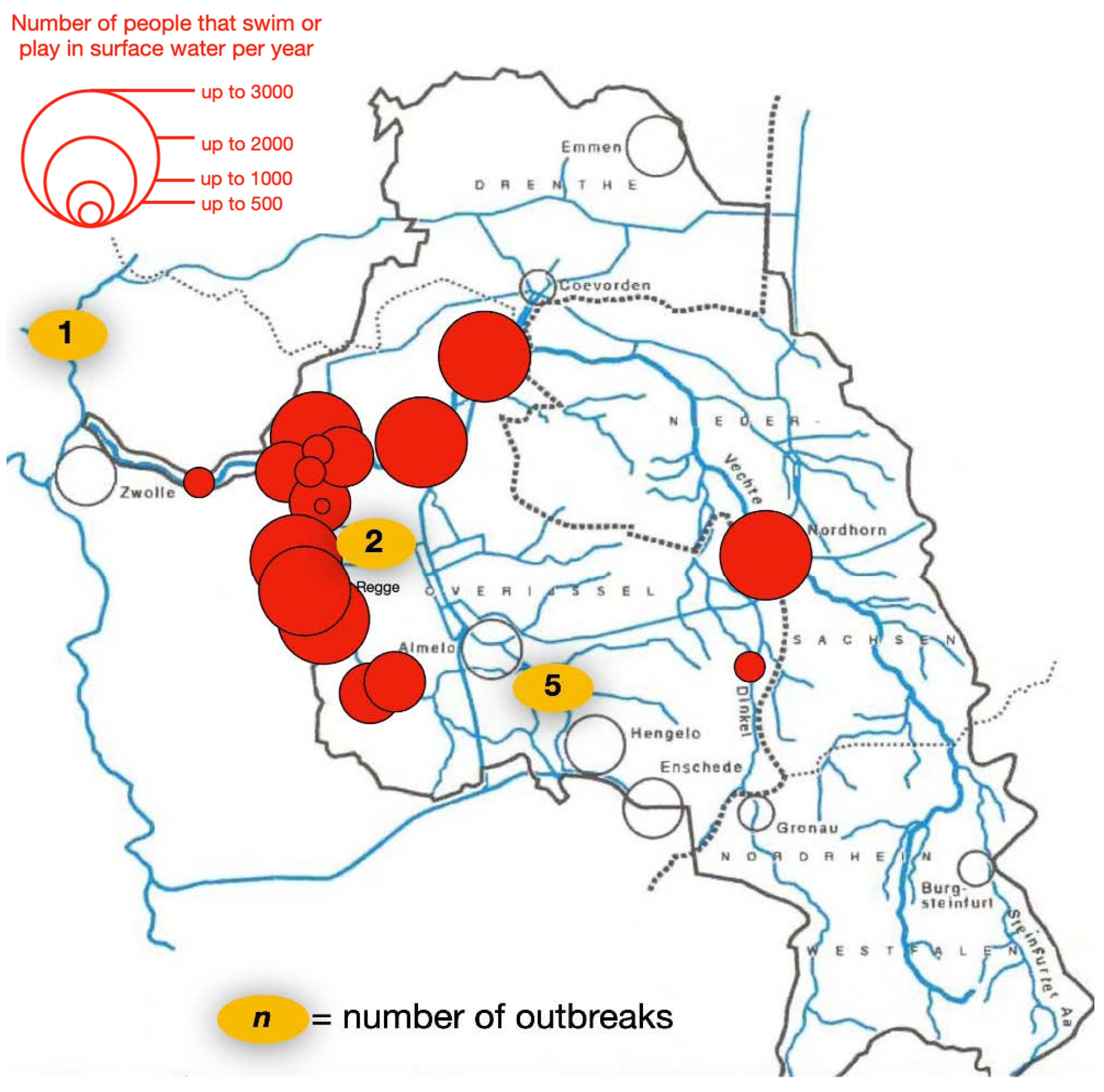

In 2019-2021, on very hot days, groups of visitors could be found scattered along the Regge and Vecht rivers. The presence of sandy beaches, sunbathing areas and bridges makes the water attractive to a large public. In 2021 a total of 10 sandy beaches were along the Regge, Vecht and Dinkel rivers (

Figure 4;

Figures S1-S3). The origins and management of the beaches vary considerably. Some of the beaches are natural banks created by river erosion (the Dinkel) or bank widening as part of river restoration (in particular the Regge and Vecht). Some beaches were originally intended for launching canoes (Ommen, Dalfsen). Other beaches have been created and are maintained by the adjoining campsites (Mölke, Grimberghoeve, Koeksebelt). The natural beaches along the Dinkel are maintained by the Vechtstromen water authority. The city beach in the center of Almelo was constructed in 2019 and is maintained by the municipality. During warm days the need for beaches at all locations significantly exceeds the supply. For example, since 2020, the campers at Camping de Roos at Beerze have been making eager use of the widened banks along the Vecht.

In total 24 main wild swimming locations were identified (

Table S1 and

Figure S4). Wild swimming sites were not diffused throughout the catchment. The vast majority of these sites were located in the western (Dutch) part of the catchment. In the eastern (German) part of the catchment, only a single swimming location was found (a beach at the Vechtesee), but people also swam in the German Vecht on warm days. Nine camping sites that promote wild swimming were located along the Vecht and the Regge. There are six sites across the area that also host annual water sports events, which include wild swimming. The number of wild swimmers per location varied from a few dozen to several thousand per year (

Figure 5). Municipalities with the largest numbers of wild swimmers were Wierden, Rijssen-Holten, Hellendoorn and Ommen.

In total, during the warm summers of 2018 to 2020, between 29,000 and 37,000 (on average approximately 33,000) people per year swam in the rivers, streams and canals of the Vecht river basin. The population of wild swimmers consisted of camping guests, participants of annual sporting events (triathlons, city swims, survival races), scouts and daily visitors (

Table S1).

Children and adolescents were the groups being most regularly and intensively in contact with surface water. For example, although it is strictly forbidden to jump from bridges, on hot days jumping could be seen in several places (

Figures S5-S8). These groups of young people were mainly from the local area. Camping guests and scouts from outside the region stayed for between a few days and several weeks. In contrast, participants of sports and game events had intensive water contact for a very short period of time.

3.2. Economic Value of Wild Swimming

In the German/Dutch Vecht catchment, approximately 80,000 water visitors yearly used paid services during the hot summers of 2018 to 2020, excluding round trips with tour boats (

Table 1; detailled

Table S2)

. The Vecht with some 56,000 annual paying visitors (excluding 10,000 visitors/year per tour boat) from 11 companies was the most popular river. Next came the Regge with over 22,000 visitors from 4 companies; the Bornsebeek with about 1,500 visitors from 2 companies, and the Dinkel with about 550 paying visitors from 2 companies. Of these customers 16,000 (20%) had intensive contact with the water. This means that nearly half of the wild swimmers in the river basin were paid recreational swimmers. It shows that wild swimming is used and encouraged by hire companies and therefore represents an economic interest.

The absolute number and percentage of wild swimmers (both paying and non-paying) were highest in the Regge and lowest in the Bornsebeek. In the Vecht, there were relatively few paying wild swimmers compared to the number of water tourists. Wild swimmers seemed to prefer the more pleasant beaches and sunbathing areas along the Regge. The fact that motorboats are not allowed on the Regge contributes to this. In the Vecht, many tourists hired a motorboat. The number of (non-paying) canoeists on the Regge was probably underestimated. River restoration is expected to make the Vecht and Dinkel more attractive for water recreation, including wild swimming.

3.3. Wild Swimming Associated Outbreaks in the Netherlands

As outbreaks are indicative of biological risks to which people are exposed when in contact with water, the study also collected data on outbreaks that were attributed to wild swimming. For the purpose of reference, data concerning outbreaks associated with water recreation in the whole of the Netherlands was analyzed. Through the Dutch platform for swimming at official swimming locations in open water (zwemwater.nl), 1,055 outbreaks were reported between 1991 and 2013. About 60% of the complaints were skin complaints, particularly swimmer's itch caused by

Trichobilharzia, and 30% gastrointestinal complaints [

15]. An internet search for reports of GE outbreaks associated with wild swimming in the Netherlands, including the Dutch part of the study area, revealed at least 20 potentially wild swimming-related GE outbreaks between 2014 and 2020 (Table A3). The limited data suggest that these outbreaks were widespread throughout the country (

Figure S2). Only one outbreak involving leptospirosis (Weil's disease, caused by

Leptospira spp.) was found, affecting just two people. There were no reported outbreaks of swimmer's itch related to wild swimming.

Projection of all registered outbreaks over a calendar year reveals that these outbreaks coincided with the water recreation season from June to September (

Table 2). A quarter of the outbreaks occurred in the month of September. The number of wild swimmers decreased significantly in this month after the summer holidays, but group outings, city swims etc. still took place.

The maximum number of cases per reported GE outbreak was 364 and the average number of cases per outbreak was 37 (Table A3). In total, at least 746 people fell ill. In 8 cases, the group size was not known. The 12 cases where the group size was known involved a total of 7,768 participants, of whom at least 678 became infected. It is unclear how many swimmers became ill per incident, as not everyone reports gastrointestinal illness and not everyone relates it to contact with surface water. In cases where the group size was known, the maximum infection frequency was 75% and the overall average infection frequency was 11.46%. Most reported outbreaks have occurred during sporting events with large numbers of participants. Sporting events were mainly attended by adults (5,900 adults compared to 550 children). Other wild swimming activities were almost exclusively attended by adolescents and children (1,318 against zero adults). No reports were found before 2014. Group infections presumably caused by wild swimming therefore seems to be a phenomenon of recent years. However, after 2014, possibly due to the (limited) data, no increase or decrease in the number of outbreaks could be observed (2014: 1; 2015: 3; 2016: 4; 2017: 0; 2018: 4; 2019: 7; 2020; 1).

3.4. Wild Swimming Associated Outbreaks in the Study Area

In the years 2016 - 2020, at least eight wild swimming associated GE outbreaks occurred in the Vecht river catchment (Table A3). A total of 1201 people, almost exclusively children, participated in the activities, of whom at least 107 became infected. The infection rate varied from 2 to 22.73% and the average infection rate was 11.22%.

There have been no reports of further spread of infection in the local community. Given the significant number of individuals who engage in recreational activities in surface waters within the designated area, the overall risk of infection appears to be minimal. Nevertheless, under certain circumstances, there is a possibility of elevated risk levels, which could result in outbreaks. Since no stool or other samples were analyzed, there is no indication of what caused the group infections. Various factors can cause outbreaks, including sick recreationists, food poisoning, pathogens originating from untreated sewage, livestock or wild animals, and pathogens that naturally live in water. According to local water authorities, the risk of infection from wild swimming is often associated with periods of heavy rainfall that result in sewage overflows. However, it has been observed that outbreaks have occurred during both periods of heavy rainfall and drought. It was also notable that the outbreaks were not evenly distributed among the swimming locations. The outbreaks did not occur at the locations most popular with wild swimmers, but were limited to three locations. As illustrated in

Figure 5, there have been five outbreaks in Bornsebeek, two outbreaks at the Koemaste location in Midden-Regge and one outbreak in Zwarte Water. These locations had no more than a few hundred wild swimmers per year (

Table S1). It therefore seems that local circumstances were at play. All reported activities associated with outbreaks of gastroenteritis included intensive contact with surface water through the combination of playing, jumping, diving and swimming. It is acknowledged that children and adolescents have the potential to ingest elevated quantities of water, thereby increasing the likelihood of exposure to pathogens during recreational activities involving water [

16]. As shown in

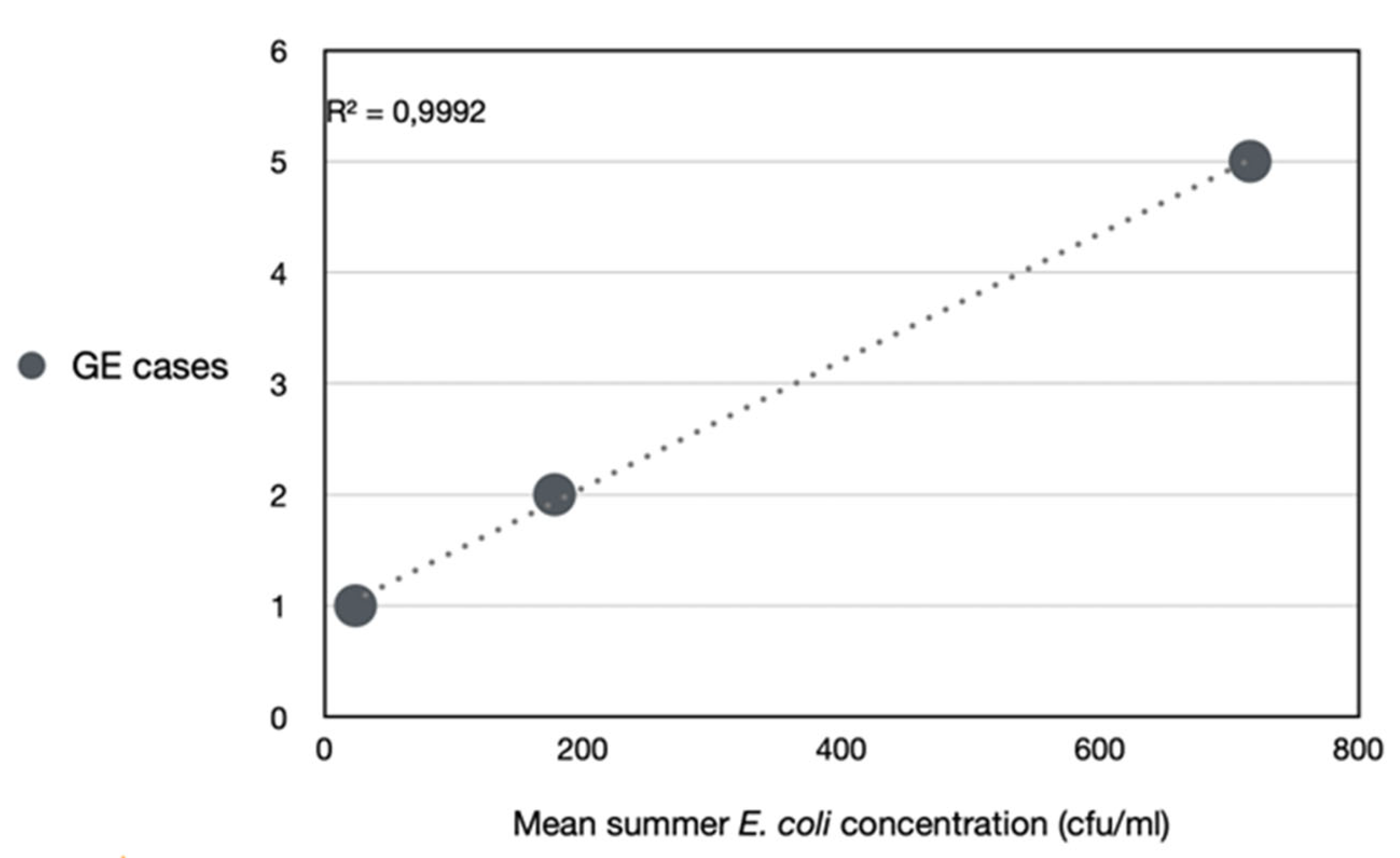

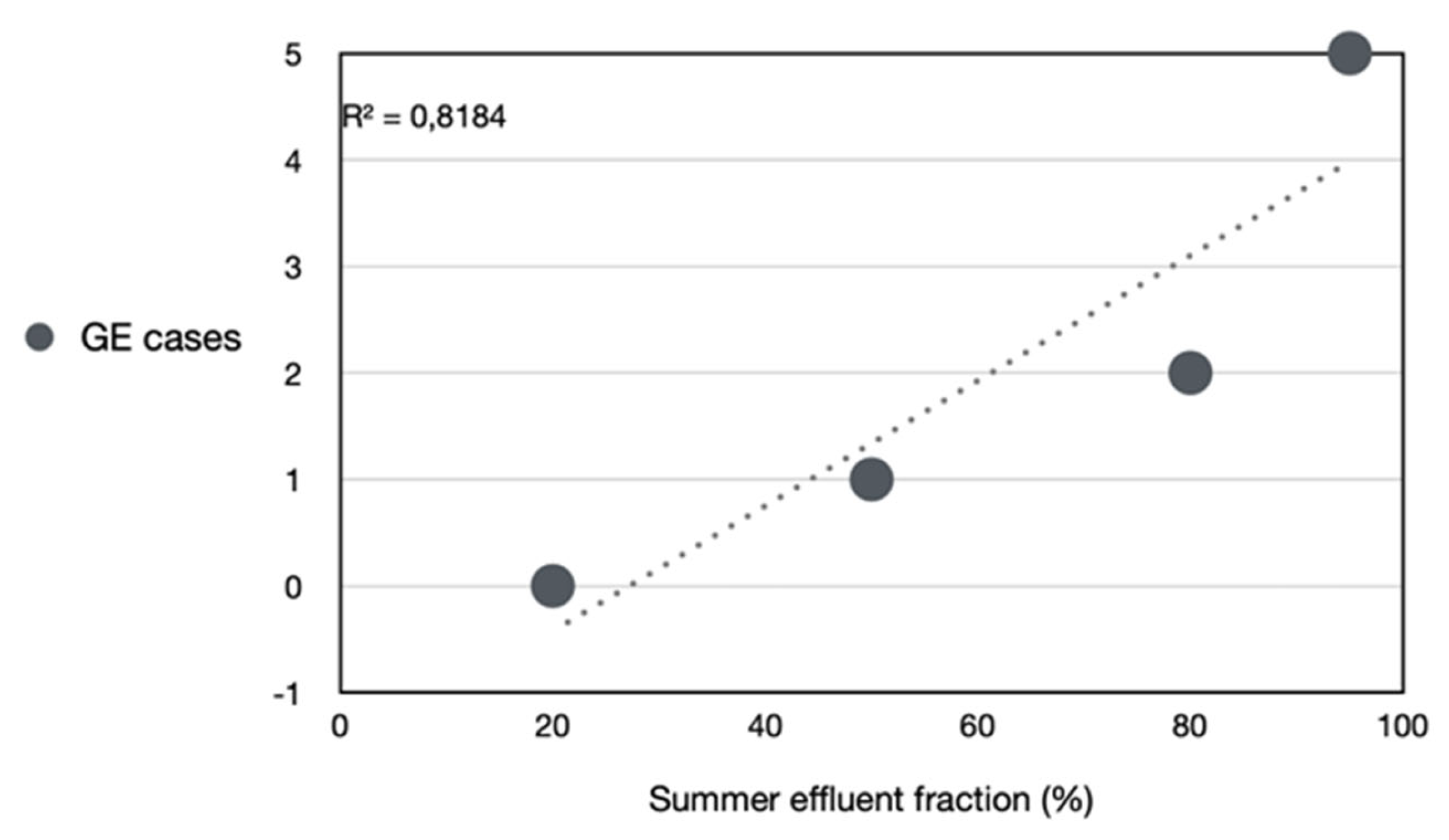

Table 4, these waters (with the exception of Zwarte Water) were exhibiting STP-effluent fractions ranging from 80–95% and

E. coli concentrations between 15,000–71,500 colony forming units (cfus)/100 ml. The summer

E. coli concentration (R² = 0.9992) and, to a lesser extent, the summer effluent fraction (R² = 0.8184) predict the likelihood of GE (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). This finding suggests that the reported outbreaks were indeed associated with exposure to faecally contaminated water.

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Assessment of the Study Area

Assuming the presence of pathogens in the water was indeed the cause of the outbreaks, it would be prudent to consider appropriate measures. Prior to the in-depth exploration of potential policy measures concerning wild swimming, this chapter undertakes a systematic analysis of the prevailing policy framework within the designated study area.

4.1.1. Mass Behavior Not Foreseen

Mass use of (effluent-carrying) streams, rivers, lakes and canals not designated as bathing water during heat waves was not foreseen in Dutch national and regional future scenarios for both water recreation [

18,

19] climate and public health [

20,

21]. In one study, it was assumed that people would stay indoors in extreme heat and therefore swim less [

15]. Enquiries among recreationists in the study area revealed that during heat waves, residents of poorly insulated homes and poorly weatherproofed residential areas seek out local bodies of water in order to avoid experiencing heat stress. Avoiding entrance fees, chlorine, crowds and control are other factors that contribute to the choice of swimming location. Young people who go bridge jumping, for example, are there among themselves; without parents and lifeguards. The beautiful surroundings (experience of the landscape) and recreational habits passed down from generation to generation also play a role. Another stimulating factor is that the visual quality of flowing surface water has improved significantly since the 1960s due to the reduction of nutrients in sewage treatment plants [

22]. Consequently, during the consultations, the quality of flowing surface waters in the study area was rated positively by water recreationists (

Figure 8). The idea that surface water is good for bathing again is an international phenomenon that also seems to be part of a health trend, especially among city dwellers, towards contact with natural elements for recreation and sport [

23]. This favourable trend has made the flowing surface waters of the study area attractive for tourism and has also led businesses and governments to promote water recreation. Campsite owners and boat hire companies in the study area communicate to their customers that water quality is under control. According to the companies, the Bornsebeek (in summer ≥90% STP-effluent), for example, is an excellent place for all kinds of water recreation “because it is always full of water, even during the driest periods”. In recent years, campsite owners have created beaches along rivers that attracts masses of people. Furthermore, when major sporting events are held on rivers and canals, the public expects recreation in these waters to be commonplace and the biological and chemical risks to be manageable and negligible [

24]. In addition, the local water authority has been sending an ambivalent message, on the one hand discouraging wild swimming and on the other hand allowing swimming outside the designated areas and communicating that the water is clean [

25] (see also

Figures S10-S13). Moreover, national (semi) governmental institutions regard river swimming as a healthy form of exercise. According to the Dutch Institute for Public Health and Environment (RIVM), swimming offers children exercise and relaxation, which contributes to good health. “For this reason, it is not considered desirable to discourage swimming and other forms of water sports by merely pointing out the risk of (usually minor) health complaints” [

26].

4.1.2. Wild Swimming as Legal Dilemma

Wild swimming puts governments in a dilemma. According to the European Bathing Water Directive (BWD, 2006/7/EC), it is not allowed to swim in surface waters that has been polluted by effluent and overflow from sewage treatment plants. Based on the

E. coli levels shown in

Table 3, it can be concluded that 71% of the flowing waters used for recreational purposes in the study area did not comply with the BWD. It is also estimated that 85% of wild swimmers in the area were exposed to these contaminated waters. Also the Dutch Health Council considers the proximity of STP discharges and overflows to be incompatible with the function of bathing water [

27]. According to the regional authorities, people use flowing surface water at their own risk [

25,

28]. However, this can only be done properly if the risks are known. Acquiring knowledge about unknown hazards is not an individual matter, but a public one. By discouraging swimming in non-designated waters, whilst tolerating and encouraging recreation in these waters, (semi) governments seem to be relieved of the task of monitoring water quality and managing risks. This is not in line with the spirit of the Bathing Water Directive, which is to manage risks in places where large numbers of people are expected to swim.

4.1.3. Low Risk Awareness

At present, society is hardly aware of outbreaks outside healthcare facilities. In the study area, health departments, local and regional governments and water authorities approached have not expressed concern about the reported GE outbreaks. However, the contacted stakeholders did associate them with water contact. Commotion is also unfavorable for the image of the institutions, schools and companies involved. Only one boat hire company systematically informed customers of the risk of waterborne infection and advised them to shower after canoeing. Outside the school holidays, schools are a place where outbreaks are noticed because suddenly several children fall ill at the same time. Children go to recreational areas together after school and school classes meet at swimming locations. However, although 11 of the 16 schools contacted were aware that their pupils swam in the Regge, few schools were aware that the group infections can be caused by contact with surface water. Only the schools with the most recent outbreaks, after pupils had been in contact with the water in the Bornsebeek or Regge, took more precautions, for example when organizing canoe trips or other surface water activities. At one affected primary school near the Regge, a link has been made between swimming in the river and health problems known as 'Regge disease'. The affected schools have expressed concern and have called for governments to take action. However, they have also acknowledged that they avoided publicity in order to minimize any potential damage to their image. General practitioners generally only see individual cases, should people ask for help with a stomach flu. Three general practitioners' offices in Hellendoorn and Nijverdal along the Lower Regge approached in July 2020 were not aware of any water recreation-associated outbreak.

4.1.4. No Outbreak Monitoring

In the study area, only two of the eight reported GE outbreaks came to the attention of the regional health and water authorities. Previously undetected outbreaks were only reported by local stakeholders. The discovery of these outbreaks indicates that by no means all cases come to light. There is no protocol for reporting and recording wild swimming related outbreaks in the area. Existing procedures are not always appropriate for wild swimming. The reporting of an outbreak may be followed by an investigation of the cause. According to the regional health authority (GGD Twente, 2019), in the Netherlands water authorities only take water samples at the request of a municipal health authority after a surface water-related outbreak reported by a GP or school. However, the process of reporting, submitting requests, sampling and analyzing can take days, while heavy rain can completely change the situation within hours. In addition, water authorities only measure indicators of fecal contamination (mainly

E. coli) and do not test for pathogens. For example, the outbreak following a sporting event in and around the Bornsebeek in June 2019 was not investigated because, according to the local water authority, “it made no sense to measure

E. coli in a water body that mainly carries much STP-effluent”. Still, it is important for risk management to report outbreaks. To prevent the spread of infectious diseases, GPs, laboratories and health care institutions in the Netherlands are legally obliged to report certain infectious diseases to the communal health service. Of the six most frequent water recreation-related diseases in the Netherlands, this only applies to leptospirosis and shigellosis. The other four frequent water recreation-related infections, caused by cyanobacteria, sapo-/noroviruses, adenoviruses and trichobilharzia, do not need to be reported [

29]. On the other hand, food poisoning involving two or more people must be reported [

30]. As sapo-/noroviruses are also an important source of food poisoning, these common and highly infectious viruses are of legal relevance. In practice, identifying this group of pathogens is not yet straightforward, and distinguishing between infections caused by food, recreation or other factors is difficult. It is therefore appropriate to report all group infections

. This is in line with the message from the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC): "Public health/environmental authorities should be informed of two or more cases of diarrhoea and/or vomiting within a 24-hours that are linked by time, place and person” [

31].

4.2. Assessment of Possible Measures

In the following possible measures to lower biohazards of wild swimming will be discussed. Their levels of knowledge, efficacy in solving infection risks, practical applicability, implementation and/or maintenance costs, and social acceptance will be assessed. While complete avoidance of water contact may be difficult in areas with high dependence on surface water for recreation or economic activities, these measures can significantly reduce risks. The goal is not to limit fun, but rather to combine the enjoyment of swimming with safety and awareness.

4.2.1. Raising Awareness and Risk Perception

Citizens need information to weigh up their own risks. Nevertheless, most people are not fully aware of the pathogens in the water and the factors favoring their proliferation. They are also unaware of the social consequences of infection. The risks of sopo- or norovirus infections, for example, are not limited to children and adolescents wild swimming. In the family, they can infect more vulnerable young brothers and sisters as well as grandparents. Family members can transmit these infections to others. A noro- or sapovirus infection taken to a care home can spread quickly [

32,

33] and cause severe complications in the elderly [

34]. The adoption or rejection of protective measures and changes in preventive behavior are influenced and determined by awareness and risk perception. As such, these factors are the key pillars in the promotion of safe recreational water use. However, risk behavior cannot be changed by information alone as more knowledge about risks is not related to less risky behavior [

35]. People's capacity to weigh information and make rational choices is limited [

36]. Especially, during heat waves, the need for contact with water is great and the threshold for water contact is low. People may be informed but still choose not to change their relationship with surface water. If a risk is perceived as low or unlikely, preventive measures may seem unnecessary or even excessive, making them difficult to accept. Those who place a higher value on leisure than on public health, or those who are indifferent to their own or others' health, may be less inclined to accept restrictions based on risks that they perceive as less visible or imminent. People may perceive a high risk but reject measures as inconvenient, costly or incompatible with the enjoyment of water activities. Also, risks could be perceived to be inherent to the water activity or unavoidable. Furthermore, social pressure, previous experience and trust in authorities shape risk perception.

To be effective, awareness messages should be differentiated by group [

37]. Specific strategies are needed for children, adolescents and adults, highlighting risks and benefits in terms that resonate with each group. For example, visual or interactive narratives could be used for children and adolescents, while adults may prefer clear facts and practical options. Interventions that include more domains like neighborhoods, parents, schools, health professionals, scouting groups, camping holders, outdoor sports and tourism companies, events organizers and (social) media could be more effective [

38]. Key actors can also be asked to contribute to the targeted approach. For example, schools could provide information to children and their families. Therefore, awareness raising should start with the professionals and educators involved

As risk perception is highly subjective and varies between demographic groups and professional contexts, raising awareness is a complex and costly process. To facilitate work and to lower costs messages can be integrated into routine communications. Information sharing between health, recreation and water sectors needs to be encouraged to balance access and safety. For example, it is the duty of water authorities to provide information on the extent of sewage water treatment and to be transparent about the occurrence and consequences of overflows. Local health services are expected to provide data on the various pathogens associated with sewage effluent and to explain the societal consequences of these infections. This collaborative approach can align perceptions and avoid conflicting messages to the public. The process of aligning content, methods, channels and audiences is a lengthy one. Moreover, to be effective, risk awareness and perception should be integrated with other complementary strategies. To enable the provision of appropriate information, research is required on the local pathogen(s) involved and on the factors that promote an outbreak. To be able to change recreationists' perceptions of water quality and recreation in unofficial recreational waters, also these local perceptions need to be understood.

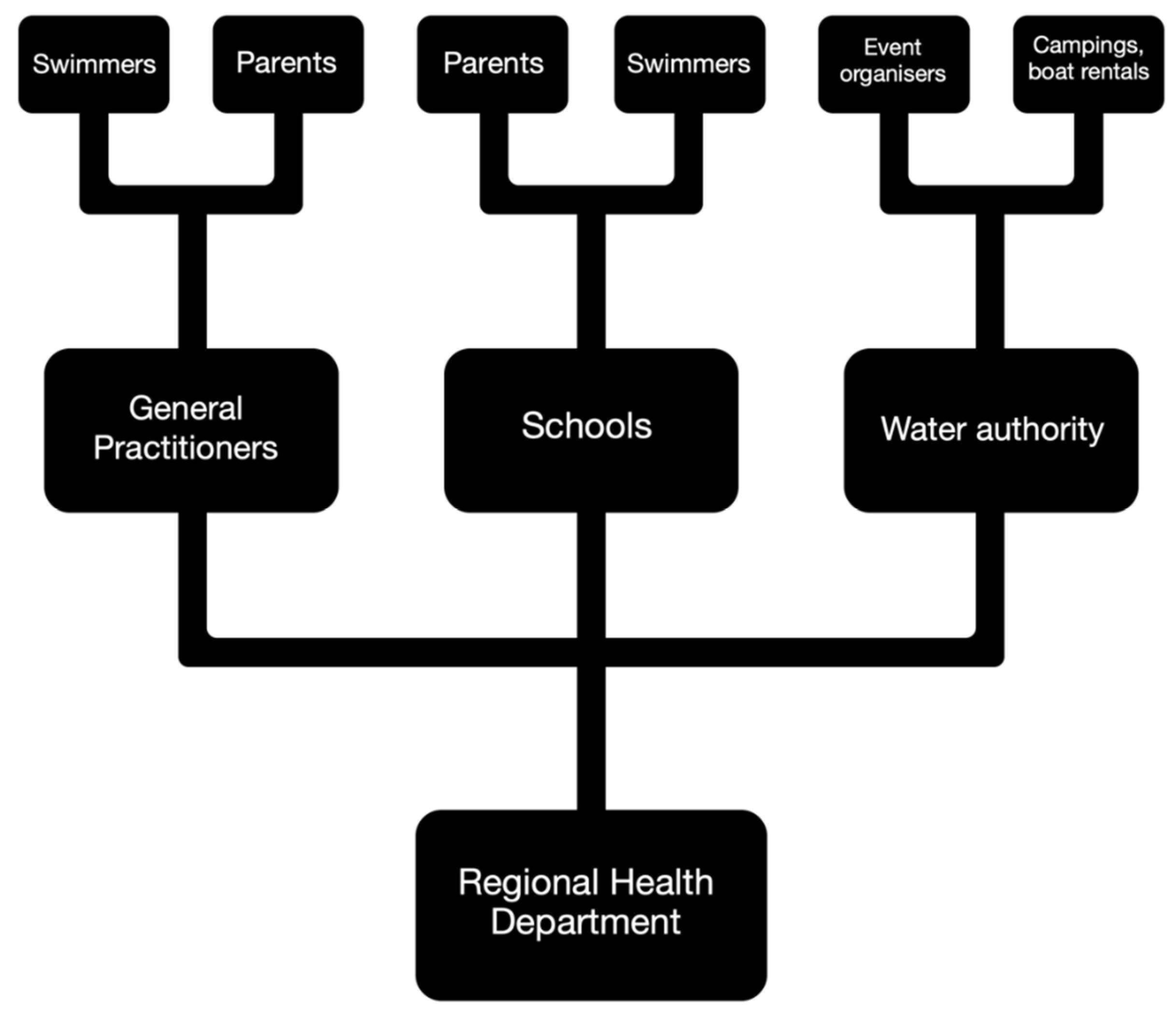

4.2.2. Outbreak Surveillance

Monitoring outbreaks provides insight into the risks of wild swimming; who is most at risk, what are the societal consequences, and what may be the most effective interventions. There has been little research on outbreaks associated with recreation in surface water that is contaminated with STP-effluent. Due to the short duration of infections systematic recording of outbreaks is difficult. By the time health authorities receive the information it is too late for further investigation. To enable and speed up effective monitoring of outbreaks, it is essential to improve the status of wild swimming and raise awareness of the biological risks involved, while facilitating anonymous reporting. Surveillance is most effective if outbreaks are reported directly by stakeholders. For public health reasons, all professionals involved could consider it a social duty to report outbreaks. It would be preferable if boat rental companies, event organizers, campsite owners and schools were required to report outbreaks to the local water or health authority. GPs, hospitals, laboratories and families could be asked to report to the health services (

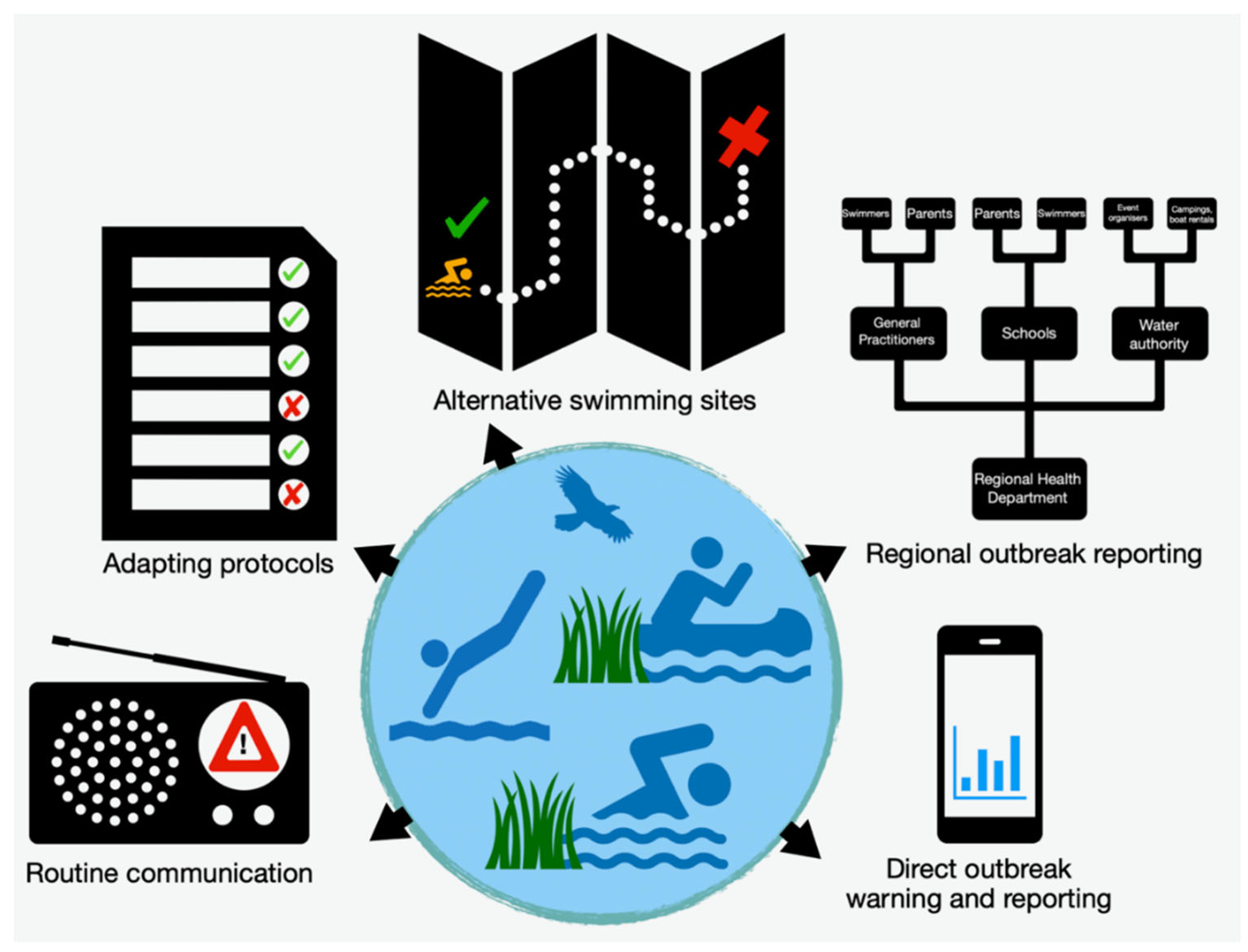

Figure 9). In the Netherlands, for example, water recreationists and their families can voluntarily report complaints via zwemwater.nl. This portal is only for complaints about official bathing water. A similar but anonymous service could be developed for wild swimmers. Outbreak monitoring can be incorporated into the official outdoor swimming routines of water managers and health departments. The registration of outbreaks and the consideration of measures demonstrate that governments are responsive to the needs of their citizens. Conversely, the failure to register outbreaks and the refusal to implement measures may create a negative perception.

4.2.3. Biohazard Monitoring

According to European Bathing Water Directive, in places where there is mass recreation in the water, monitoring of fecal contamination should take place. However, monitoring of fecal indicators may not be relevant in water bodies where STP-effluent is routinely discharged or where sewage overflows occur. In addition, it is uncertain if indicators of fecal contamination say anything about the presence of pathogens [

39]. Once information is available on the presence of the pathogens that are causing local outbreaks, consideration could be given to measuring only these pathogens in water and sediment [

40]. As a precautionary measure, this also applies to resistant micro-organisms [

41]. However, due to effects of droughts and heavy rainfall, concentrations of pathogens and resistant micro-organisms may vary locally considerably [

42]. Conditions that are expected to increase in the coming decades [

43]. Moreover, the efficacy of conventional risk assessment techniques, which employ fortnightly measurements, averaging variations and exclude sediments, is questionable.

Furthermore, the inherent variability of microorganisms at the local level is too high to be accurately represented by a single standard sample [

44]. Consequently, measurements may provide an illusory sense of security. Further consideration should be given to the possibility of undertaking faster and regular measurements. With new PCR techniques pathogens can be determined more quickly based on their DNA or RNA. However, it is still unclear to what extent DNA/RNA detection relates to the risk of infection. Additionally, the role of sediment in preserving and transferring pathogens, as well as its relationship to weather conditions and overflows, must be clarified. Without this information, the analysis of water samples may not accurately represent the actual risk. It therefore can be considered whether measurements in the sewer (

environmental or sewage water surveillance) are suitable methods for predicting the burden of the surface water with, for example, noroviruses [

45]. The presence of pathogens in continuous effluent carrying waters may also be well predicted by models [

46,

47]. If pathogens in water and sediment are linked to the STP-effluent fraction, risk management could be related to this fraction. Modelling avoids the need for expensive, labor-intensive and lengthy measurements. On the other hand, a model-based approach is usually also non-reactive. An alternative option is the implementation of instant and cost-effective analysis methods, which can be utilized by those who are most involved at or immediately prior to the moment when they intend to use the water. Finally, to gain a better understanding of the health hazard, also more knowledge is needed about the negative health effects on wild swimmers and their immediate social environment.

4.2.4. Hazard alerts

The management of the risks associated with wild swimming is still in its relatively early stages of development. In the absence of precise data regarding the nature of the infection risk, it is not possible to determine the most effective management strategy. Consequently, the current measures are either ineffective or even counterproductive. For example, discouraging swimming while simultaneously developing infrastructure such as beaches and communicating that sewage is cleaned up is misleading to the public and undermines the credibility of warnings. Furthermore, rapid detection methods must be implemented before rapid warnings can be issued.

It will also be necessary to determine the extent to which other biological and chemical risks associated with the use of STP effluent-containing surface water of, for example, drinking water abstraction, irrigation and (sports) fishing, will be integrated into the risk management and communication. Modern, largely model-based, techniques make it possible to have continuous access to actual information on the chances of water contact-related infections and other related risks. The Water Information System (WIS)

, developed for the Vecht basin by the University of Osnabrück, based on measurements and modelling (GREAT-ER model) of some pharmaceuticals and antibiotic-resistant

E. coli, has been a first step towards such an integrated approach [

17,

48,

49]. Such a platform visualizes contamination to managers, governors and the general public through maps, and also offers the possibility to test the effectiveness of possible measures through simulations. To ensure the platform is fit for purpose in assessing the risk of infection from wild swimming, it would be necessary to add data on pathogens in water and sediments.

The development and implementation of an integrated risk management and warning system requires a certain investment of time and financial resources. Furthermore, effective data collection, sharing and communication require close coordination between the relevant stakeholders in public health, water, sanitation, agriculture, fisheries, education, recreation and tourism. If the warning system is unambiguous and responsive, indicating water safety per water body and targeting different user groups, hazard warnings will be more readily accepted. Ideally, the public and local media will be automatically kept informed of actual local risks via the Internet, for example through a mobile application. Through linked theme-specific mobile applications, the different groups can be served.

4.2.5. Adapting Infection Prevention Manuals

Infection prevention manuals do not yet take into account the risk of infection from wild swimming. Currently, the relevant authorities use infection prevention protocols for water recreation in average surface waters. For example, in the case of a waterborne outbreak, the Dutch Infection Control Coordination Centre (LCI) advises that the water should be allowed to flow to reduce the source of infection [

29]. Such measures are not effective for effluent-carrying water bodies, as STP-effluent is discharged day and night throughout the year. Such measures are also ineffective when sediment is a source of pathogens. The ECDC guidelines for the prevention of gastro-enteritis or norovirus infection in schools advise the application of a strict hand washing regime. Emphasis is placed on food handling and toilet use [

31]. After-school recreation in contaminated surface water is not included in the guideline. Washing hands or taking a shower after contact with surface water is not effective if the infection inadvertently entered the body directly through the mouth and nose.

Especially during the summer season, instructions for hygiene measures should be extended to the outdoors activities. Particular attention should be paid to transmission to vulnerable people. Inclusion of these risks in standard manuals promotes recognition and action. It also reduces conflicting messaging by professionals. The adaptation of the manuals is relatively simple and can already be done at low cost on the basis of the current understanding of the risks of wild swimming. Measures are more likely to be accepted when all stakeholders contribute. For example, by setting up a school infection network, parents, family doctors and regional health services can be warned in good time, cases can be detected more quickly, and additional measures can be initiated earlier.

4.2.6. Vaccination

Once there is a better understanding of the pathogens behind outbreaks, vaccination of wild swimmers may be considered. Vaccination isn't just a preventive measure; it also raises awareness and can act as a disincentive. In the case of the highly infectious sopo-/noroviruses, a vaccine is currently in development. However, due to the high mutation rate of these viruses, it is likely to be effective for only six months [

50]. Given that outbreaks are particularly prevalent among young people, annually recurring vaccination programs can be implemented through schools and linked to events held in or around waters that carry sewage effluent. However, the development and application of the vaccins is expensive. The potential for reluctance to vaccinate with a rapidly expiring vaccine is high, particularly given the current lack of awareness regarding the potential health hazards associated to wild swimming. Furthermore, vaccination may provide an erroneous sense of security. While vaccination against an infectious virus can instill a sense of protection, other pathogens present in water can also cause infection. In addition, even after vaccination, individuals can unknowingly act as a source of infection.

4.2.7. Upgraded Sewage Treatment

The impact of not fully treated effluent from sewage treatment plants on surface water is typically evaluated in terms of its effect on water quality. The analysis does not include sediment, which constrains the capacity to evaluate the efficacy of STPs in averting infections. Although the incorporation of sophisticated water treatment processes represents an efficacious approach to pathogen management, this outcome is nullified during sewer overflows resulting from heavy precipitation. Overflows replenish the pathogens left in the sediment, thereby extending the duration of the overflow's impact [

51]. While techniques are available, their implementation and maintenance costs are considerable. It is probable that social acceptance will be low in the event of a substantial increase in water treatment and pollution charges.

4.2.8. Banning Wild Swimming

It is unlikely that simply banning wild swimming will deter people from ignoring the cooling, clear running water during a heatwave. Even less so when all kinds of facilities are offered to encourage people to swim and public swimming pools are being closed due to high costs and staff shortages.

A ban is easy to institute but may meet with low social acceptance and is costly to implement as surveillance is needed over a large area. Acceptance will be diminished if this is perceived as a means of circumventing the responsibility of (semi-)government bodies.

4.2.9. Promote Safe Alternatives

Information can be provided regarding alternative water-based recreational activities that carry a lower level of risk, such as controlled swimming pools or bodies of water that are monitored. Some individuals may be reluctant to depart from natural aquatic environments due to an affinity with immersive experiences of nature or outdoor recreation. The extent to which safe alternatives are accepted depends on how these options are promoted to various groups of recreational users in terms of convenience and enjoyment, and on how the freedom to enjoy natural waters is presented. The practical applicability of promoting safe alternatives is dependent upon the presence of adequate infrastructure and a constant monitoring system within the community. The costs of developing and maintaining alternative water recreation options may be considerable, but they can be offset in the long term by the public health benefits and reduction of water-related diseases.

The assessment of possible measures to lower biohazards of wild swimming has been summarized in

Table 4 and

Figure 10. In short, targeted awareness raising, adaptation of prevention manuals, outbreak surveillance with regional and direct outbreak reporting, and promoting safe alternatives are expected to be relatively easy to apply, effective, socially acceptable and not very costly. In order to achieve optimal efficacy, it is essential to integrate risk awareness and perception with other complementary strategies. It is recommended that the reporting of outbreaks by schools, camp sites, rental companies and event organizers to health authorities be made mandatory. It is anticipated that annual vaccination and upgraded sewage water treatment will prove ineffective, very costly and met with social opposition. Further research and development are required in order to assess the applicability of pathogen monitoring and hazard alerts. To get started, a simple biohazard warning system can be set up based on expected STP-effluent fractions and sewer overflow risk.

5. Conclusions

In the area studied, wild swimming is practiced by both locals and tourists, stimulated by heat waves, advertising and recreational infrastructures such as beaches. Wild swimming can be part of paid and unpaid leisure activities, and contributes to well-being, enjoyment of the landscape, and the local economy. However, outbreaks of infection show that it is not without health risks. In past future scenarios, mass recreational behavior of people during heat waves was not anticipated. As a result, there is a gap in knowledge about the risks of wild swimming and prevention measures are delayed. Future research on this phenomenon should focus on analyzing human behavior during heat waves, identifying the micro-organisms responsible for outbreaks and studying the local circumstances that increase the likelihood of infection. To prevent the spread and possible accelerated mutation of pathogens, it is essential to prioritize awareness of the risks of infection associated with recreational activities in surface waters fed by sewage treatment plants. It is also recommended that infection prevention manuals are adapted, a system for reporting and recording outbreaks is established, early warning procedures and appropriate indicators are implemented, and effective surveillance and risk management models are developed.

The practice of wild swimming will continue to increase as heat waves become more frequent due to climate change. To manage this activity structurally, it needs to be recognized as an emerging social phenomenon. This means not only addressing the risks associated with water recreation, but also improving the livability of homes, schools, workplaces and creating more green spaces in neighborhoods to help people better adapt to high temperatures. However, it is foreseeable that many people will defy warnings and restrictions and seek to cool off in nearby waters, often unaware of the risks involved. The resulting outbreaks of infection have a disruptive effect on society, affecting groups such as schoolchildren, residents or staff of different institutions at the same time. In addition, these outbreaks can have a significant economic impact on businesses in the tourism and leisure sectors. The occurrence of infections also serves as a warning sign of other potential risks, such as the presence of resistant microorganisms and hazardous chemicals in the water. The introduction of effective risk management procedures in relation to water recreation complements the European Union's efforts to achieve good chemical and biological status of surface waters, including Germany [

52] and the Netherlands [

53]. These goals, complicated by climate change [

54], can only be achieved if all stakeholders are willing to collaborate. This requires promoting synergies between different efforts and ensuring effective communication and cooperation, including at transboundary level.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s, Figure S1: Wild swimming in the Vechtesee, Municipality of Nordhorn; Figure S2: Sunbathing lawn at the Vecht, Municipality of Dalfsen; Figure S3: City beach near the centre of Almelo (under construction, 2020); Figure S4: Wild swimming locations in the Vecht watershed; Figure S5: Sunbathing lawn and bridge jumping at the Vecht, Municipality of Ommen; Figure S6: Bridge jumping in Midden Regge near camping Grimberghoeve, Rijssen; Figure S7: Bridge jumping in the Midden Regge near the Koemaste, Hellendoorn; Figure S8: Organized bridge jumping in the Bornsebeek, Borne; Figure S9: Reported GE outbreaks associated with wild swimming in the Netherlands 2014 – 2020; Figure S10: Water authorities also promote swimming in the Vecht; Figure S11: Information panel at the Bornsebeek, Borne; Figure S12: Triathlon in the Vecht, Municipality of Hardenberg; Figure S13: Play facility across the Bornsebeek, Borne; Table S1: Wild swimming locations and numbers of wild swimmers in the Vecht river basin during the hot summers of 2018, 2019 and 2020; Table S2: Clients from German and Dutch boat rentals in the Vecht watershed between 2018 and 2020; Table S3: Reported GE outbreaks associated with wild swimming in the study area and the rest of the Netherland Wild.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.U. and A.M.; methodology, A.U. and A.M.; validation, A.U. and A.M.; investigation, A.U. and T.K.; data curation, A.U. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.U, A.M. and T.K.; writing—review and editing, A.U. and T.K.; supervision, A.U. and T.K.; project administration, A.U. and T.K.; funding acquisition, A.U. and T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was part of the Interreg-VA Deutschland-Nederland MEDUWA-Vecht(e) (project no. 142118) (meduwa.eu). The project has been funded by the European Union's Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the Lower Saxony Ministry for Federal and European Affairs, the Ministry of Economic Affairs of the Land of NRW, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Change and the provinces of Overijssel, Gelderland, Flevoland and Friesland.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data obtained have been included in

the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all camping site owners, boat renters, employees of water authorities, health services and schools. The data obtained from stakeholders has been anonymized in this report to protect their commercial interests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Nuffield Health. Wild swimming | A beginner’s guide to open water swimming. Available online: https://www.nuffieldhealth.com/article/beginners-open-water-swimming-guide#what-is-wild-swimming (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Griffiths, S. Trends in Outdoor Swimming Report. Available online: https://outdoorswimmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/TrendsReport_Full_LR.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Oliver, D.M.; McDougall, C.W.; Robertson, T.; Grant, B.; Hanley, N.; Quilliam, R.S. Self-reported benefits and risks of open water swimming to health, wellbeing and the environment: Cross-sectional evidence from a survey of Scottish swimmers. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0290834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, W.; Krainz, M.; White, M.P.; Heske, A.; Elliott, L.R.; Bratman, G.N.; Fleming, L.E.; Grellier, J.; McDougall, C.W.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; et al. The psychological benefits of open-water (wild) swimming: Exploring a self-determination approach using a 19-country sample. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2025, 102, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, H.; Gorczynski, P.; Harper, C.M.; Sansom, L.; McEwan, K.; Yankouskaya, A.; Denton, H. Perceived Impact of Outdoor Swimming on Health: Web-Based Survey. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2022, 11, e25589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbury, K.; Conroy, B.W.; Marks, E. Swimming in nature: A scoping review of the mental health and wellbeing benefits of open water swimming. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2023, 90, 102073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, M.; Marshall, A.N.; Keeler, S. Open Water Swimming: Medical and Water Quality Considerations. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2019, 18, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marutescu, L.G.; Popa, M.; Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Barbu, I.C.; Rodríguez-Molina, D.; Berglund, F.; Blaak, H.; Flach, C.-F.; Kemper, M.A.; Spießberger, B.; et al. Wastewater treatment plants, an "escape gate" for ESCAPE pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1193907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Fischer, M.A.; Neumann, B.; Kiesewetter, K.; Hoffmann, I.; Werner, G.; Pfeifer, Y.; Lübbert, C. Carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in hospital wastewater, wastewater treatment plants and surface waters in a metropolitan area in Germany, 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 890, 164179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, C.; van den Akker, B.; Young, F.; Franco, C.; Blackbeard, J.; Monis, P. Pathogen and Particle Associations in Wastewater: Significance and Implications for Treatment and Disinfection Processes. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 97, 63–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.; Taye, A.; Walsh, B.; Maguire, H.; Dave, J.; Wright, A.; Anderson, C.; Crook, P. A large outbreak of gastrointestinal illness at an open-water swimming event in the River Thames, London. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 1246–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, R.; Sonder, G.; Parkkali, S.; Brandwagt, D.; Fanoy, E.; Mughini-Gras, L.; Lodder, W.; Ruland, E.; Siedenburg, E.; Kliffen, S.; et al. Risk factors for gastroenteritis associated with canal swimming in two cities in the Netherlands during the summer of 2015: A prospective study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, H.; M. A. Kemper; R. Pijnacker; L. Mughini; A. M. de Roda Husman; C. Schets; H. Schmitt. Resistente darmbacteriën bij open water zwemmers (Resistant intestinal bacteria in open water swimmers). Available online: https://rivm.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10029/623618/2019-0113.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wöhler, L.; Niebaum, G.; Krol, M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The grey water footprint of human and veterinary pharmaceuticals. Water Res. X 2020, 7, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schets, F.; De Roda Husman, AM. Infecties door recreatie in oppervlaktewater: huidige en toekomstige risico's op transmissie in Nederland. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2014, 158, A7969. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour, A.P.; Behymer, T.D.; Cantú, R.; Magnuson, M.; Wymer, L.J. Ingestion of swimming pool water by recreational swimmers. J. Water Health 2017, 15, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heijnsbergen, E.; Niebaum, G.; Lämmchen, V.; Borneman, A.; Hernández Leal, L.; Klasmeier, J.; Schmitt, H. (Antibiotic-Resistant) E. coli in the Dutch-German Vecht Catchment─Monitoring and Modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15064–15073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcadis Heidemij Advies. De Regge, blauwe slagader van Twente - Een visie voor het jaar 2020.

- Tuunter E, H de Jong, K Hoenderkamp. Pre-verkenning waterrecreatie. Inventarisatie van beschikbare kennis.

- Sterk, A.; Schijven, J.; Nijs, T. de; Roda Husman, A.M. de. Direct and indirect effects of climate change on the risk of infection by water-transmitted pathogens. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12648–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynen M; van Vliet A; Staatsen B; Hall L; Zwartkruis J; Kruize H; Betgen C; Verboom J; Martens P. Kennisagenda Klimaat en Gezondheid. Available online: https://www.zonmw.nl/sites/zonmw/files/typo3-migrated-files/Kennisagenda_Klimaat_en_Gezondheid_digi_versie.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Rozemeijer, J.C.; Klein, J.; Broers, H.P.; van Tol-Leenders, T.P.; van der Grift, B. Water quality status and trends in agriculture-dominated headwaters; a national monitoring network for assessing the effectiveness of national and European manure legislation in The Netherlands. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 8981–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmin-Woolfrey, U. Why wild swimming is Britain's new craze. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20210603-why-wild-swimming-is-britains-new-craze (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- GGD Amsterdam. Zwemmen in open water. Available online: https://www.ggd.amsterdam.nl/gezond-wonen/zwemmen-open-water/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Vechtstromen. Waterbeheerplan 2016 - 2021. Available online: https://repository.officiele-overheidspublicaties.nl/externebijlagen/exb-2015-63/1/Bijlage/exb-2015-63.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Schets FM; De Roda Husman AM. Gezondheidsklachten door recreatiewater in de zomers van 2014, 2015 en 2016. Vooral veel kinderen met klachten / IB 06-2017. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/weblog/gezondheidsklachten-door-recreatiewater-in-zomers-van-2014-2015-2016-IB-06-2017 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wijbenga, A. , van Dissel, J., Haring, BJAM., Huisman, J., Leenen, EJTM., Medema, GJ., Mur, LR., Ruiter, H., Sluiters, H., & Woudenberg, F. Gezondheidsraad: Microbiële risico's van zwemmen in de natuur. Available online: https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/documenten/adviezen/2001/11/27/microbiele-risicos-van-zwemmen-in-de-natuur.

- Vechstromen. Nota Beleefbaar Water Waterschap Vechtstromen. Available online: https://waterrecreatienederland.nl/kennisbank/waterschap-vechtstromen-nota-beleefbaar-water/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Dutch Coordination of Infectious Disease Prevention. Roadmap water recreation and infectious diseases. Available online: https://lci.rivm.nl/draaiboeken/waterrecreatie-en-infectieziekten (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Dutch Coordination of Infectious Disease Prevention. Norovirus | LCI- richtlijn. Available online: https://lci.rivm.nl/richtlijnen/norovirus (accessed on 20 May 2022; 28 October 2025).

- European Centre For Disease Prevention And Control. Communication toolkit to support infection prevention in schools. Focus: Gastrointestinal diseases [Online]. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/healthtopics/food_and_waterborne_disease/communication_toolkit/Documents/131119-gastro-toolkit-implementation-hanbook.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ghosh, S.; Kumar, M.; Santiana, M.; Mishra, A.; Zhang, M.; Labayo, H.; Chibly, A.M.; Nakamura, H.; Tanaka, T.; Henderson, W.; et al. Enteric viruses replicate in salivary glands and infect through saliva. Nature 2022, 607, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Most M, Wanner T, de Jong H, Autar A, Vlaspolder F. Sapovirus, het onbekende broertje van norovirus. Available online: https://www.verenso.nl/tijdschrift-voor-ouderengeneeskunde/tijdschrift-2016-no-4-augustus/praktijk/sapovirus-het-onbekende-broertje-van-norovirus (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Koopmans MPG, LM Kortbeek, Van Duynhoven YTPH. Acute gastro-enteritis: inzicht in incidentie, oorzaken en diagnostiek door populatieonderzoek (acute gastroenteritis: insight in incidence, causes and diagnostics by population research). Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/publicaties/acute-gastro-enteritis-inzicht-in-incidentie-oorzaken-en-diagnostiek-door (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Cook, P.A.; Bellis, M.A. Knowing the risk: relationships between risk behaviour and health knowledge. Public Health 2001, 115, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M. , Keizer, A.-G., Tiemeijer, W. Weten is nog geen doen : een realistisch perspectief op redzaamheid / Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid; Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid: Den Haag, 2017; ISBN 9789490186487. [Google Scholar]

- Gorham, L.M.; Lamm, A.J.; Rumble, J.N. The Critical Target Audience: Communicating Water Conservation Behaviors to Critical Thinking Styles. Journal of Applied Communications 2014, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.A.; Henderson, M.; Frank, J.W.; Haw, S.J. An overview of prevention of multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and young adulthood. J. Public Health (Oxf) 2012, 34 Suppl 1, i31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schets, F.; Roda Husman, A. de; Havelaar, A. Disease outbreaks associated with untreated recreational water use. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyn-Jones, A.P.; Carducci, A.; Cook, N.; D'Agostino, M.; Divizia, M.; Fleischer, J.; Gantzer, C.; Gawler, A.; Girones, R.; Höller, C.; et al. Surveillance of adenoviruses and noroviruses in European recreational waters. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, D.J.; Oldenkamp, R.; Ragas, A.M.J. Modelling environmental antibiotic-resistance gene abundance: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, D.J.; Niebaum, G.; Lämmchen, V.; van Heijnsbergen, E.; Oldenkamp, R.; Hernández-Leal, L.; Schmitt, H.; Ragas, A.M.J.; Klasmeier, J. Ecological Risk Assessment of Pharmaceuticals in the Transboundary Vecht River (Germany and The Netherlands). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 41, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut. KNMI'14-klimaatscenario's. Available online: https://www.knmi.nl/kennis-en-datacentrum/achtergrond/knmi-14-klimaatscenario-s (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Lange de M, M de Haan, R Gylstra. Huidige wijze van monitoren van fecale bacteriën in zwemwater geeft geen betrouwbaar beeld van actueel gezondheidsrisico zwemmers.

- Lodder, W.J.; Buisman, A.M.; Rutjes, S.A.; Heijne, J.C.; Teunis, P.F.; Roda Husman, A.M. de. Feasibility of quantitative environmental surveillance in poliovirus eradication strategies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 3800–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.; Husman, A.M.d.R.; Altavilla, N.; Deere, D.; Ashbolt, N. Fate and Transport of Surface Water Pathogens in Watersheds. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2003, 33, 299–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, R.; Gordon, R.; Joy, D.; Lee, H. Assessing microbial pollution of rural surface waters. Agricultural Water Management 2004, 70, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebaum, G.; Berlekamp, J.; Schmitt, H.; Lämmchen, V.; Klasmeier, J. Geo-referenced simulations of E. coli in a sub-catchment of the Vecht River using a probabilistic approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watershed Information System. Available online: www.meduwa.geoplex.de (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Glass, R.I.; Parashar, U.D.; Estes, M.K. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1776–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, K.N.; Pettibone, G.W. Dynamics of indicator bacteria populations in sediment and river water near a combined sewer outfall. Environmental Technology 1993, 14, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLWKN. Unser Wasser im Fokus: Umsetzung der Wasserrahmenrichtlinie in Niedersachsen (2. Bewirtschaftungszeitraum 2015-2021. Wasserrahmenrichtlinie Band 9. NLWKN_WRRL_2017, 2017.

- Van Gaalen F, Osté L, Van Boekel E. Nationale analyse waterkwaliteit, 2020.

- WHITEHEAD, P.G.; WILBY, R.L.; BATTARBEE, R.W.; Kernana, M.; WADE, A.J. A review of the potential impacts of climate change on surface water quality. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2009, 54, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).