Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass Preparation and Characterization

2.2. Catalysts Preparation

2.3. Rice Husk ash Characterization

2.4. Catalysts Characterization

2.5. Catalyst Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

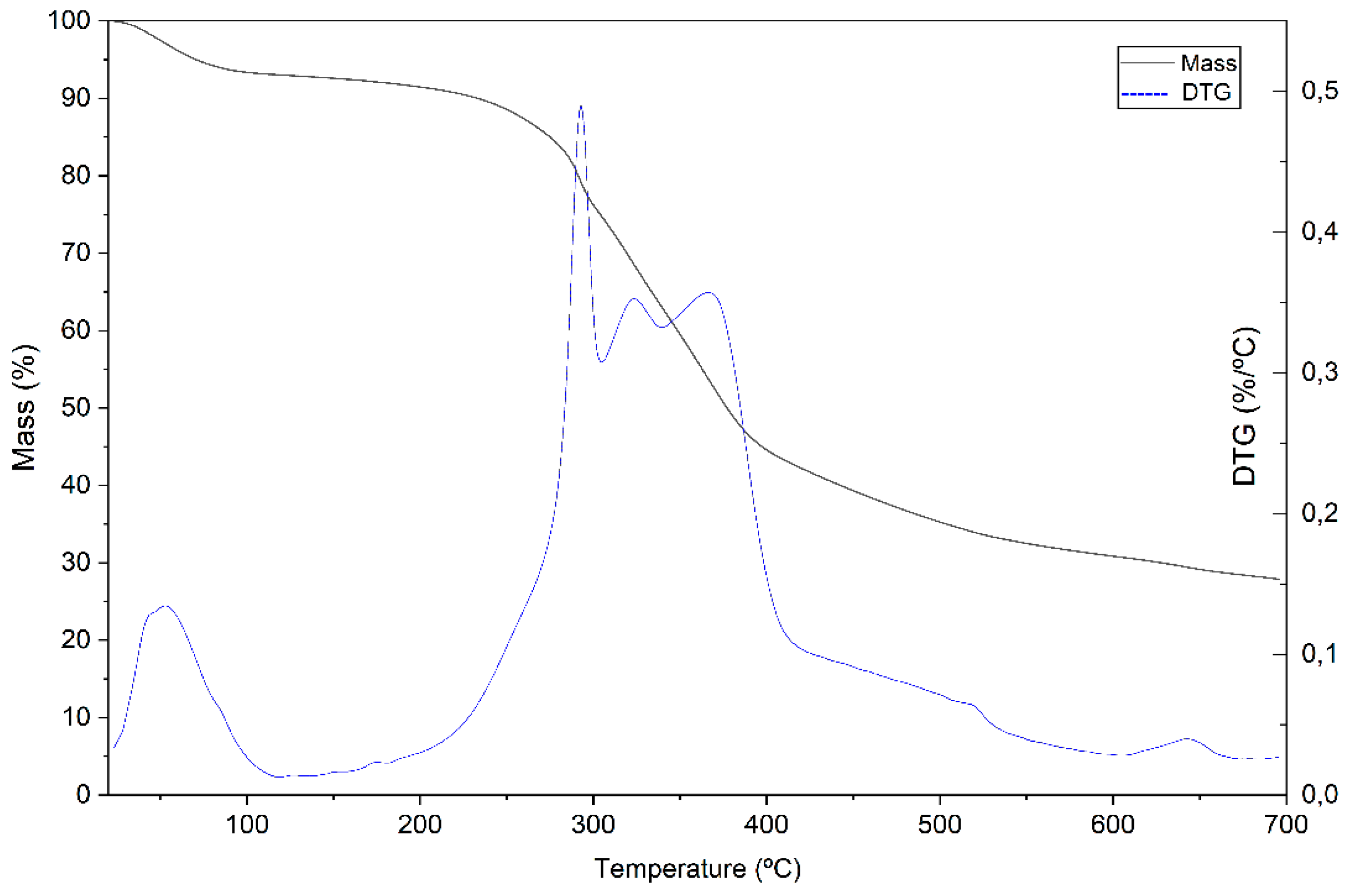

3.1. Biomass Characterization

3.2. Rice Husk Ash Characterization

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

3.3.1. Si/Al Ratio Results

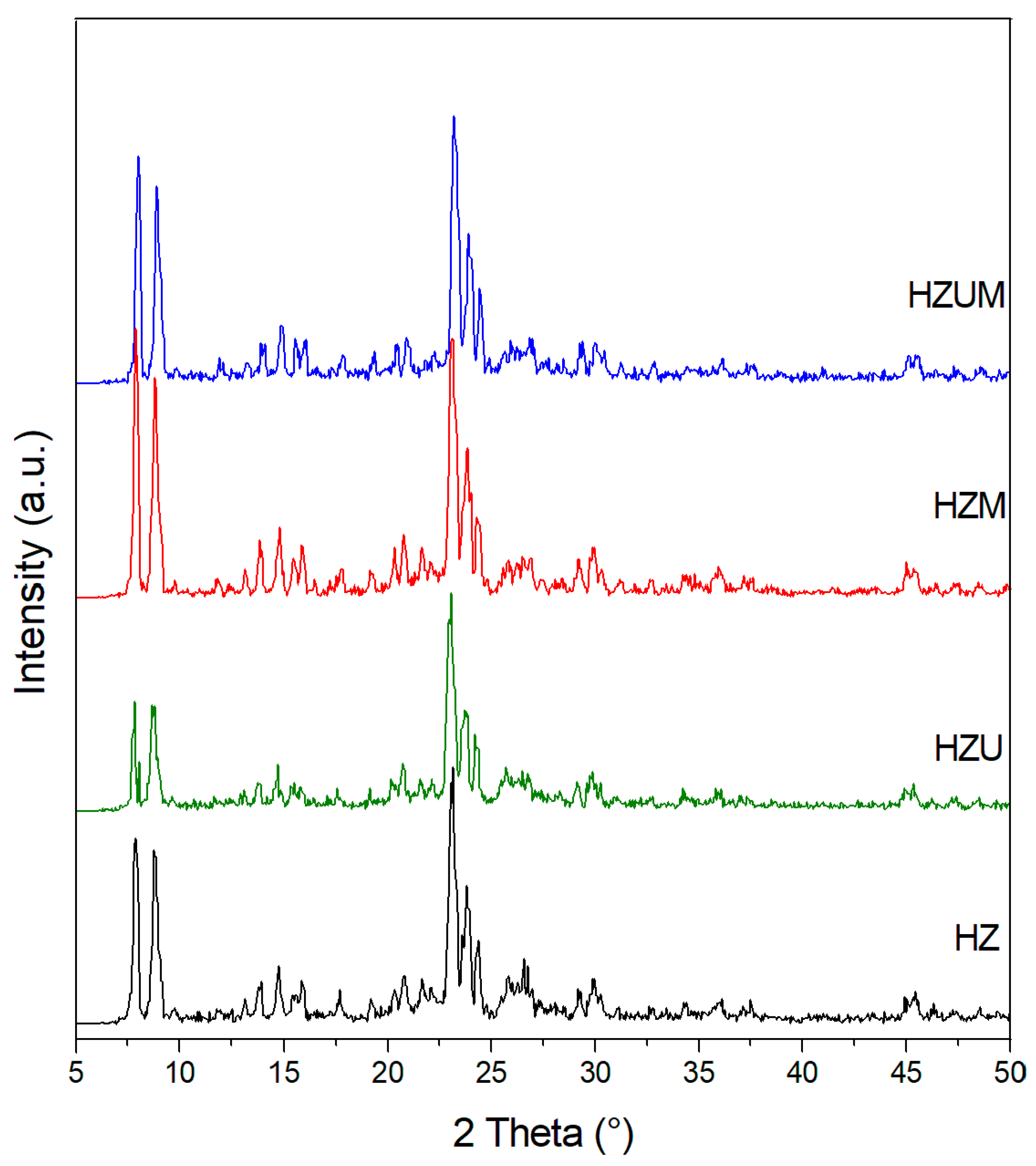

3.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Results

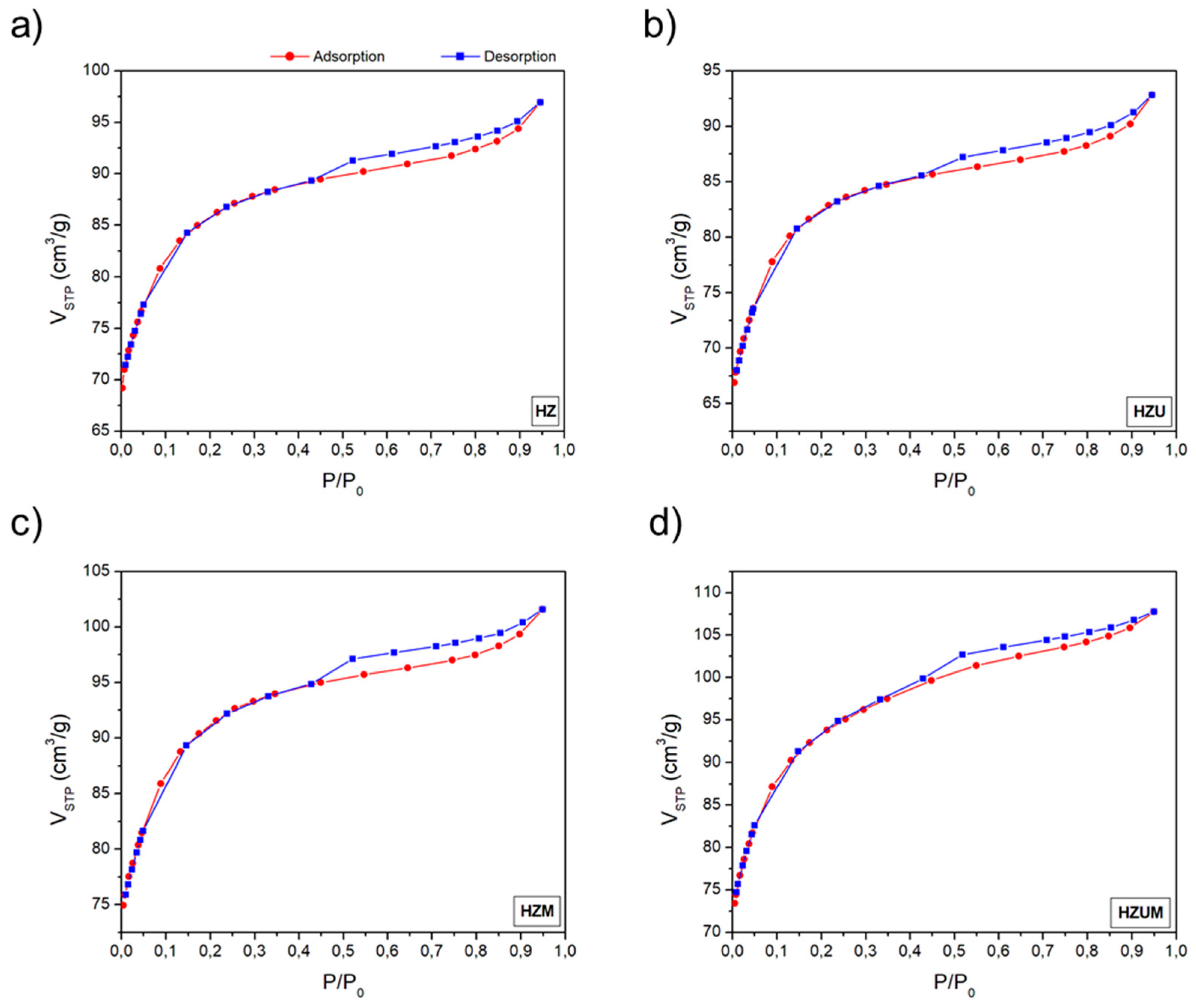

3.3.3. Textural Properties Results

| Samples | Sg (m2/g) | Vmicro (cm3/g) |

| HZ HZU HZM HZUM |

322 310 342 347 |

0.099 0.096 0.105 0.100 |

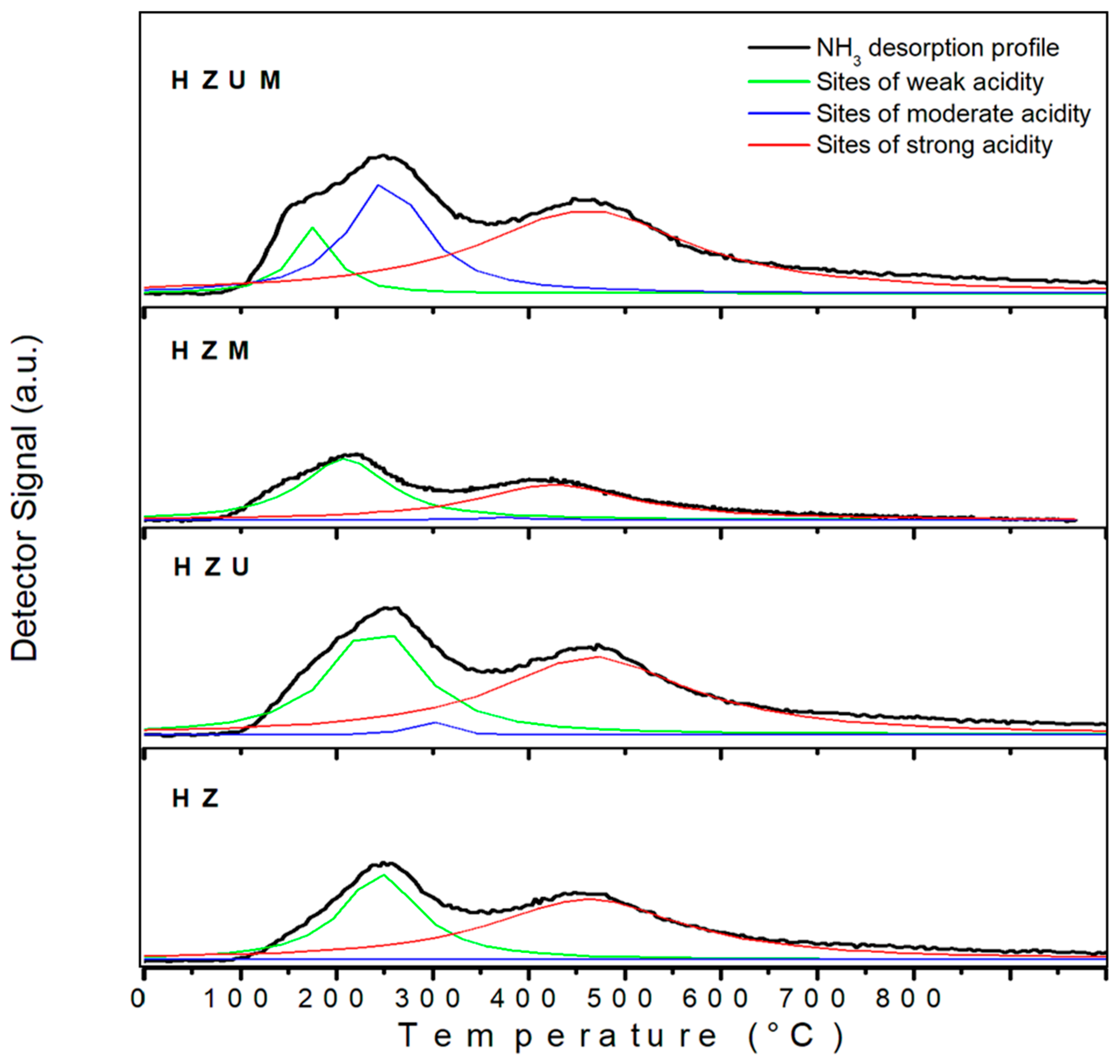

3.3.4. Acidity Results

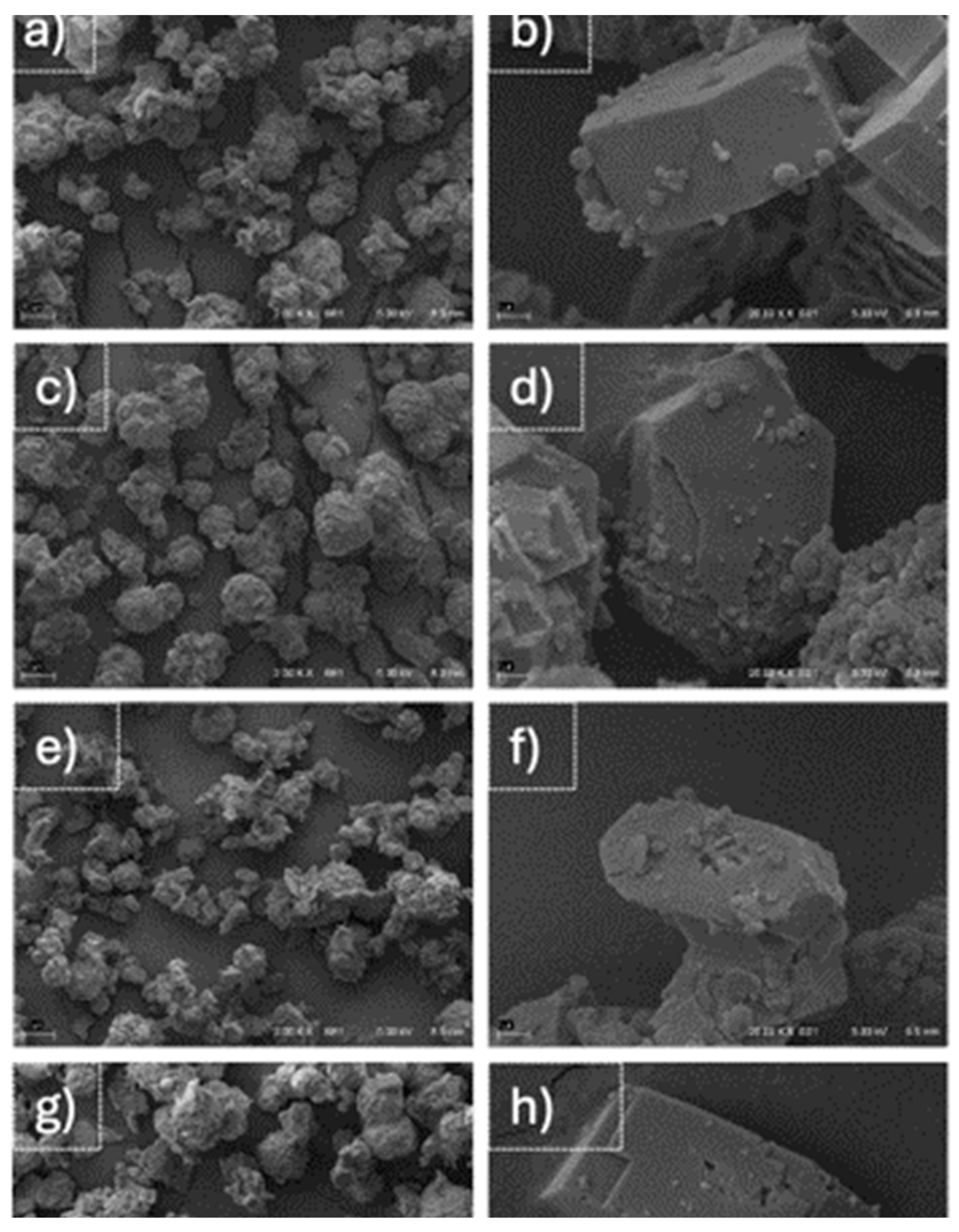

3.3.5. SEM Results

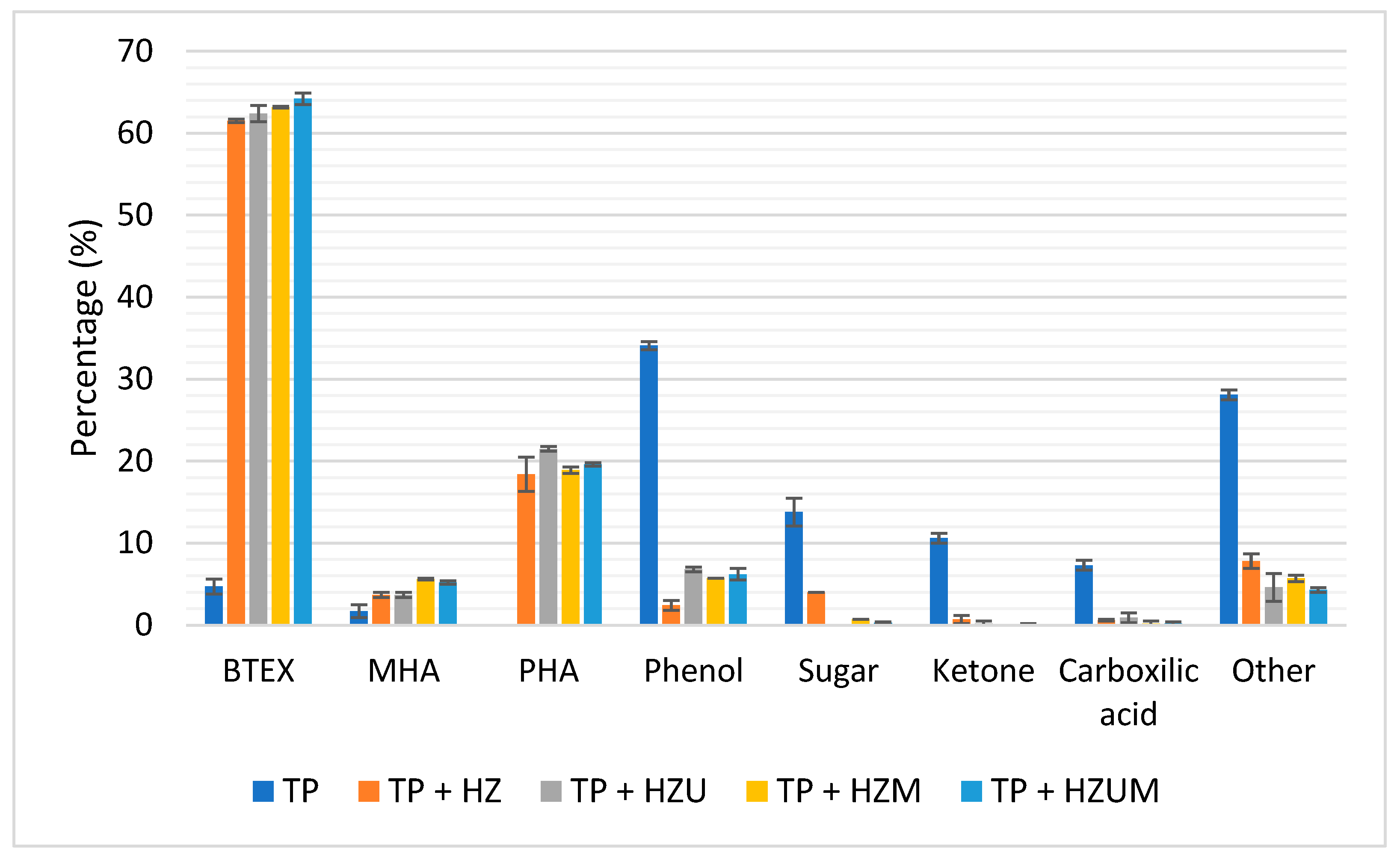

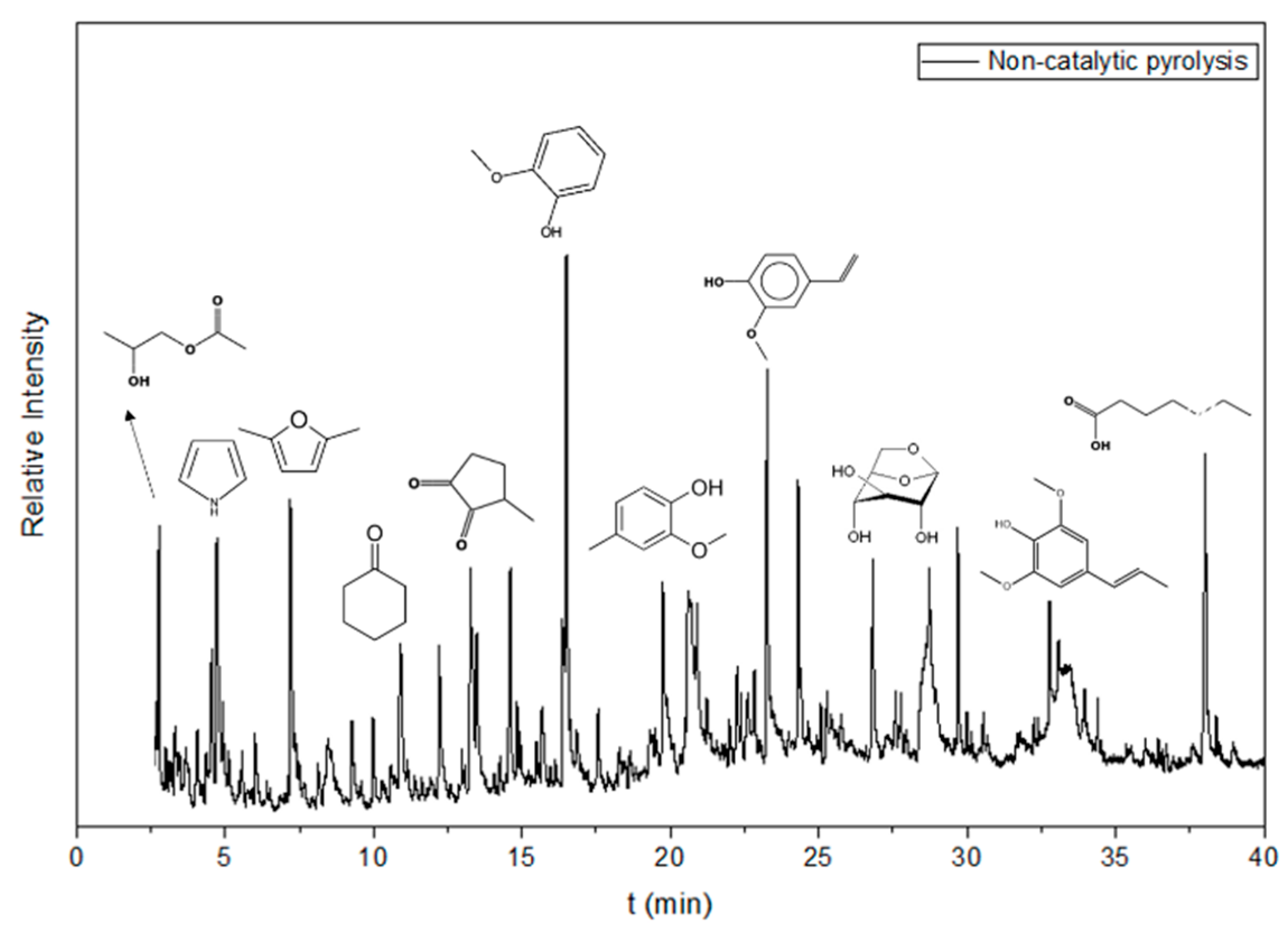

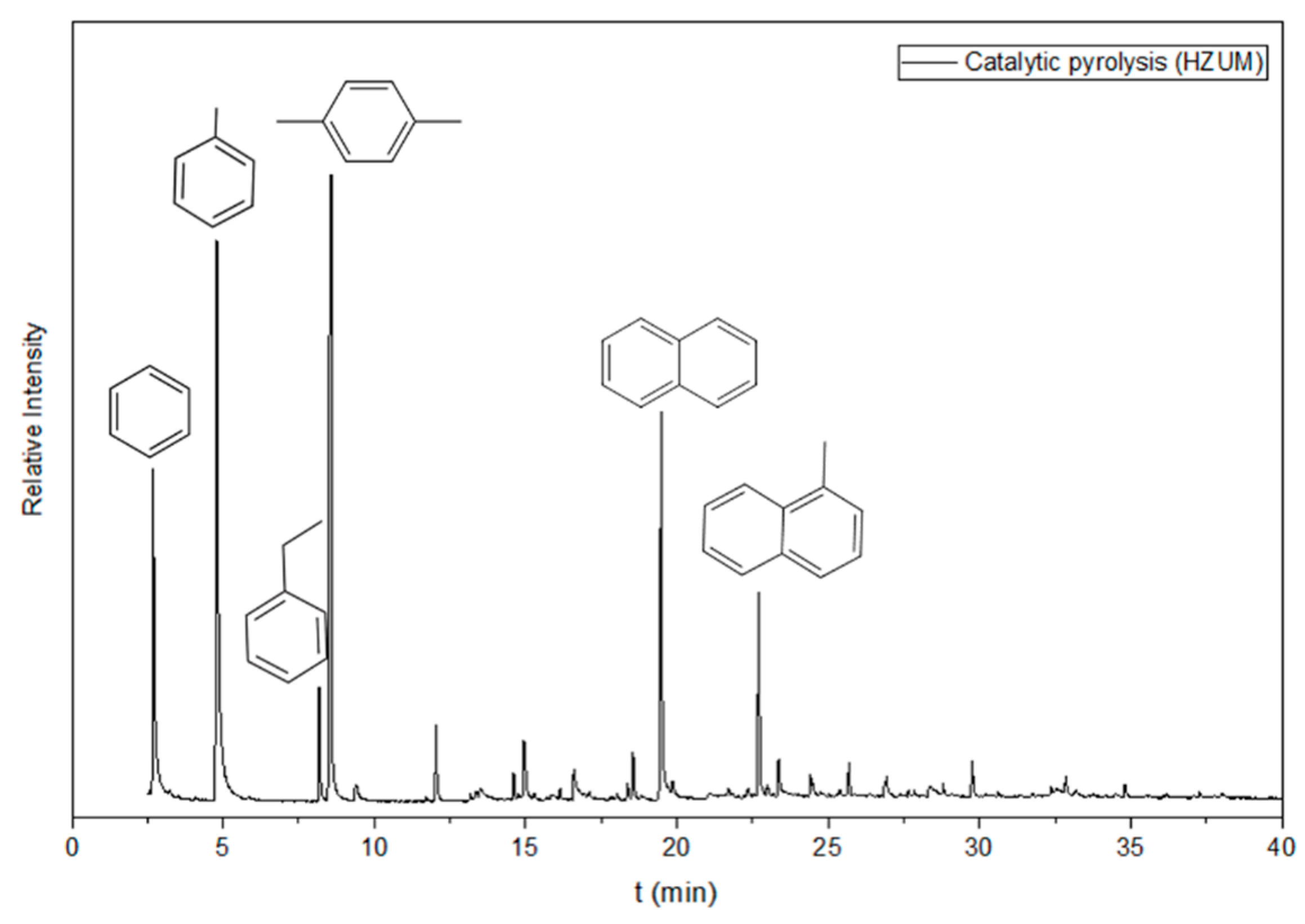

3.3.6. Catalytic Evaluation Results

| Compounds | TP | TP + HZ | TP + HZU | TP + HZM | TP + HZUM |

| Hydrogenated Oxygenated Nitrogenous |

19.4 ± 1.2% 78.1 ± 1.3% 2.6 ± 0.1% |

89.7 ± 1.3% 9.0 ± 1.1% 1.2 ± 0.3% |

91.3 ± 0.0% 8.3 ± 0.1% 0.4 ± 0.0% |

92.3 ± 0.1% 7.5 ± 0.2% 0.3 ± 0.0% |

92.0 ± 0.6% 7.6 ± 0.7% 0.4 ± 0.6% |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RHA | Rice Husk Ash |

| Z | ZSM5 zeolite without any treatment |

| ZU | ZSM5 zeolite treated with ultrasound |

| ZM | ZSM5 zeolite treated with microwave |

| ZUM | ZSM5 zeolite treated with ultrasound and microwave |

| HZ | HZSM5 zeolite without any treatment |

| HZU | HZSM5 zeolite treated with ultrasound |

| HZM | HZSM5 zeolite treated with microwave |

| HZUM | HZSM5 zeolite treated with ultrasound and microwave |

| NH3-TPD | Temperature Programmed Desorption of Ammonia |

| Sg | Specific Surface Area |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HDO | Hydrodeoxygenation reaction |

| BTEX | Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene, and Xylenes |

| PHA | Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons |

| MHA | Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons |

| Py-GC/MS | Fast Catalytic Micropyrolysis |

References

- Causes and Effects of Climate Change. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/causes-effects-climate-change (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Mahala, K.R. The Impact of Air Pollution on living things and Environment: A review of the current evidence. WJARAI 2024, 24, 03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R. The Rising Threat of Atmospheric CO2: A Review on the Causes, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Environments 2023, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Moreno, M.-A.; Samerón-Manzano, E.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J. Biomass as Renewable Energy: Worldwide Research Trends. Sustainability 2019, 11, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Possibility of utilizing agriculture biomass as a renewable and sustainable future energy source. Heliyon 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.W.; Lee, S.H.; Nam, H.; Lee, D.; Tokmurzin, D.; Wang, S.; Park, Y.-K. Recent advances of thermochemical conversion processes for biorefinery. Bioresource Technology 2022, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvari, E.; Mahajan, D.; Hewitt, E.L. A Review of Biomass Pyrolysis for Production of Fuels: Chemistry, Processing, and Techno-Economic Analysis. Biomass 2025, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelela, D.; Saleh, H.; Attia, A.M.; Elhenawy, Y.; Majozi, T.; Bassyouni, M. Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis Processes for Bioenergy Production: Optimization of Operating Conditions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahnila, M.; Koskela, A.; Sulasalmi, P.; Fabritius, T. A Review of Pyrolysis Technologies and the Effect of Process Parameters on Biocarbon Properties. Energies 2023, 16, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Kumar, D.J.P.; Sankannavar, R.; Binnal, P.; Mohanty, K. Hydro-deoxygenation of pyrolytic oil derived from pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: A review. Fuel 2024, 360, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachos-Perez, D.; Martins-Vieira, J.C.; Missau, J.; Anshu, K.; Siakpebru, O.K.; Thengane, S.K.; Morais, A.R.C.; Tanabe, E.H.; Bertuol, D.A. Review on Biomass Pyrolysis with a Focus on Bio-Oil Upgrading Techniques. Analytica 2023, 4, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, M.d.C.; Mayer, F.M.; Carvalho, M.d.S.; Saboia, G.; de Andrade, A.M. Selecting Catalysts for Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Biomass 2023, 3, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, B.; Gauram, D.K.; Yadav, H.C.; Gaurha, A.; Kumar, V.; Omer, S.; Chawla, R. Tamarind Cultivation, Value-Added Products and Their Health Benefits: A Review. IJPSS 2023, 35, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, M.A.; Islam, M.R.; Parveen, M.; Haniu, H.; Takai, K. Pyrolysis decomposition of tamarind seed for alternative fuel. Bioresour Technol. 2013, 149, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiarasu, A.; Pugazhvadivu, M. Studies on microwave pyrolysis of tamarind seed. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2225. [Google Scholar]

- Somani, O.G.; Choudhari, A.L.; Rao, B.S.; Mirajkar, S.P. Enhancement of crystallization rate by microwave radiation: Synthesis of ZSM-5. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2003, 82, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.R.M.; Giannetti, B.F.; Agostinho, F.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Sevegnani, F.; Pérez, K.M.P.; Velásquez, L. Assessing the sustainability of rice production in Brazil and Cuba. JAFR 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Du, T.; Fang, X.; Gong, H.; Qiu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Synthesis of Template-Free ZSM-5 from Rice Husk Ash at Low Temperatures and its CO2 Adsorption Performance. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 3961–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, A.M.; Ebrahimi, A.A. Eco-friendly synthesis of ZSM-5 from rice husk ash using top-down modifications for enhancing acetone-to-olefin conversion: Evaluation of catalytic performance and operating conditions. Fuel 2025, 386, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, H.; Lima, D.S.; Perez-Lopez, O.W. Hydrothermal synthesis of analcime without template. JCW 2020, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajobi, M.O.; Lasode, O.A.; Adeleke, A.A.; Ikubanni, P.P.; Balogun, A.O. Investigation of physicochemical characteristics of selected lignocellulose biomass. Scientific Reports 2022, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onokwai, A.O.; Ajisegiri, E.S.A.; Okokpujie, I.P.; Ibikunle, R.A.; Oki, M.; Dirisu, J.O. Characterization of lignocellulose biomass based on proximate, ultimate, structural composition, and thermal analysis. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 65, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.P.; Ghosh, S.; Naskar, M.K. Organic template-free-synthesis of ZSM-5 zeolite particles using rice husk ash as silica source. Ceramics International 2013, 39, 2153–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbin, R.; Karimzadeh, R. Synthesis of mesoporous ZSM-5 from rice husk ash with ultrasound assisted alkali-treatment method used in catalytic cracking of light naphta. Advanced Power Technology 2017, 28, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koningsveld, H.V. High-temperature (350 K) orthorhombic framework structure of zeolite H-ZSM-5. Acta Cyst. 1990, 46, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, T.; Otsuka, K.; Murakami, T.; Ishigami, T.; Fukui, K. Synthesis of zeolites with hierarchical porous structures using a microwave heating method. CISC 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Song, G.; Lin, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wu, T.; Yi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Kawi, S. Synthesis and catalytic performance of Linde-type A zeolite (LTA) from coal fly ash utilizing microwave and ultrasound collaborative activation method. Catalysis Today 2022, 397–399, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.S.; Lopez, O.W.P. Catalytic conversion of glycerol to olefins over Fe, Mo, and Nb catalysts supported on zeolite ZSM-5. Renewable Energy. 2019, 136, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoke, Y.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.; Arnaiz, I.; Diaz, I. Synthesis of ZSM-5 from natural mordenite from Spain. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2025, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kumar, A.; Biswas, B.; Krishna, B.; Bhaskar, T. Py-GC/MS and slow pyrolysis of tamarind seed husk. JMCWM 2024, 26, 1131–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.M.; Carvalho, M.d.S.; Mallmann, A.; Oliveira, A.P.S.; Ruiz, D.; Boeira, A.C.S.; Lima, D.d.S.; Rangel, M.d.C. Catalytic pyrolysis of MDF wastes over beta zeolite-supported platinum. Catalysis Today 2025, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiha, D.K.; Viju, D.; Vinu, R. Fast pyrolysis kinetics of lignocellulosic biomass of varying compositions. ECM 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, G.; Laurel, M.; Mackinnon, D.; Zhao, T.; Houck, H.A.; Becer, C.R. Polymers without Petrochemicals: Sustainable Routes to Conventional Monomers. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2609–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzene-Toluene-Xylene (BTX) Market Size & Share Analysis—Growh Trends and Forecast (2025-2030). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/benzene-toluene-xylene-btx-market (accessed on 7 November 2025).

| Composition | SiO2 | Al2O3 | TiO2 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | P2O5 | LOI |

| % | 93.49 | 1.36 | nd | nd | 0.3 | 0.12 | 0.33 | Nd | 1.5 | 0.18 | 1.54 |

| Samples |

Elements (% w/w) Si Al |

Si/Al |

| HZ HZU HZM HZUM |

94.2 3.5 93.8 3.8 93.8 3.9 93.7 4.1 |

27 25 25 23 |

| Samples |

T (maximum) (ºC) 1° 2° 3° peak peak peak |

Relative amount of acid sites (%) Weak Moderate Strong acidity acidity acidity |

Total acidity (µmol NH3/gcat) |

| HZ HZU HZM HZUM |

246 350 461 241 294 467 208 375 426 175 253 460 |

36.0 0.2 63.8 36.7 1.7 59.6 47.8 1.7 50.5 9.5 29.0 61.5 |

327 480 392 571 |

| Sample | BAS (a.u) | LAS (a.u) | BAS/LAS |

| 1545 (cm−1) | 1445 (cm−1) | ||

| HZ | 0.00031 | 0.0073 | 0.042 |

| HZU | 0.00032 | 0.0073 | 0.044 |

| HZM | 0.00029 | 0.0075 | 0.038 |

| HZUM | 0.00028 | 0.0082 | 0.034 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).