Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. LC Reported Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations

3. LC Clinical Manifestations in the Oral Cavity

4. Periodontitis: Definition and Systemic Impact

5. Epidemiologic Factors Shared Between LC and Periodontitis

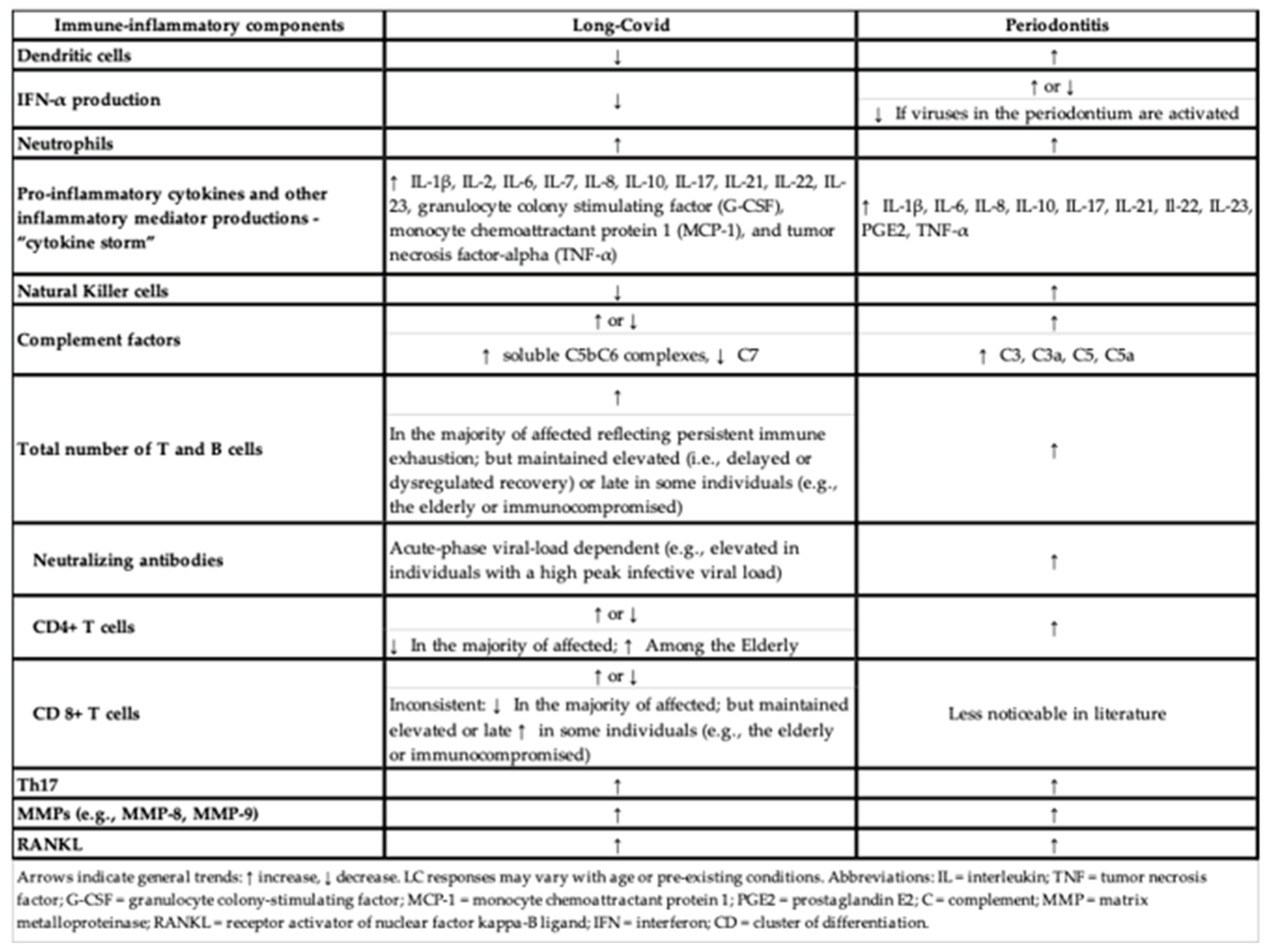

6. Immuno-Pathophysiology Mechanisms Shared by LC and Periodontitis

6.1. Early Immune Response to the SARS-COV-2

6.1.1. Interferon-Mediated Innate Immune Response to a Viral Infection

6.1.2. The Short-Term T-Cell Response to SARS-CoV-2

6.1.3. Neutrophils and the “Cytokine Storm”

6.1.4. Monocytes and Macrophages

6.2. A Persistent Active Immune Response to the SARS-CoV-2, the Key to LC

6.2.1. The Resolution of the SARS-Cov-2 Infection

6.2.2. A Persistent Dysregulation of T-Cells in LC

6.2.3. A Broad and Continuous Adaptive Immune Response Is Part of LC

6.3. The Complement System

6.4. The Role of IL-17, RANKL, and Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in Bone Metabolism Related to LC

7. The Potential Mechanisms of COVID-19/LC Effects on Periodontitis

7.1. The Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the LC and Periodontitis Association

7.2. LC May Affect Oral Dysbiosis, Increasing Susceptibility to Chronic Infections, Including Periodontitis

8. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- (WHO), W.H.O. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020; Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- Chen, C.; et al. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Infect Dis 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull-Otterson, L.B. , S; Saydah, S; Boehmer, TK; Adjei, S; Gray, S; Harris, AM Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years — United States, 20–November 2021, M.M.M.W. Rep, Editor. 2022, p. 713–717. 20 March.

- Ladds, E.; et al. Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: qualitative study of 114 "long Covid" patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A. , Long-Haul COVID. Neurology 2020, 95, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaweethai, T.; et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA 2023, 329, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; et al. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowe, B., Y. Xie, and Z. Al-Aly, Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat Med 2022, 28, 2398–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malizos, K.N. , Long COVID-19: A New Challenge to Public Health. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2022, 104, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesh, V.; et al. Symptom Clusters Seen in Adult COVID-19 Recovery Clinic Care Seekers. J Gen Intern Med 2023, 38, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese, J.T.; et al. Generalisable long COVID subtypes: findings from the NIH N3C and RECOVER programmes. EBioMedicine 2023, 87, 104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, A.; et al. Multi-organ impairment and long COVID: a 1-year prospective, longitudinal cohort study. J R Soc Med 2023, 116, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, R.H.; et al. Research Letter: Association between long COVID symptoms and employment status. medRxiv 2022. [CrossRef]

- Admon, A.J.; et al. Assessment of Symptom, Disability, and Financial Trajectories in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 at 6 Months. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2255795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M. , The Costs of Long COVID. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e221809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A detailed study of patients with long-haul COVID: an analysis of private healthcare claims. 2021: New York, NY.

- Gottlieb, M.; et al. Severe Fatigue and Persistent Symptoms at 3 Months Following Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infections During the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Time Periods: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, 1930–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandjour, A. , Long COVID: Costs for the German economy and health care and pension system. BMC Health Serv Res 2023, 23, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premraj, L.; et al. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 2022, 434, 120162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z., Y. Xie, and B. Bowe, High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 594, 259–264. [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and male infertility: from short- to long-term impacts. J Endocrinol Invest 2023, 46, 1491–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, H.; et al. Long COVID in cancer patients: preponderance of symptoms in majority of patients over long time period. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; et al. The Oral Complications of COVID-19. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 803785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; et al. Oral mucormycosis in post-COVID-19 patients: A case series. Oral Dis 2022, 28, 2591–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalowicz, B., L. Wagner, and J. Rafalowicz, Long COVID Oral Cavity Symptoms Based on Selected Clinical Cases. Eur J Dent.

- Chandwani, N.; et al. Oral Tissue Involvement and Probable Factors in Post-COVID-19 Mucormycosis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare (Basel).

- Alfaifi, A.; et al. Long-Term Post-COVID-19 Associated Oral Inflammatory Sequelae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 831744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, W.; et al. Case of maxillary actinomycotic osteomyelitis, a rare post COVID complication-case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 80, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frencken, J.E.; et al. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis - a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol 2017, 44, S94–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, M.; et al. Association between sequelae of COVID-19 with periodontal disease and obesity: A cross-sectional study. J Periodontol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2018, 89, S74–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, P.I., W. S. Borgnakke, and R.J. Genco, Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontol, 82.

- Kassebaum, N.J.; et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res 2014, 93, 1045–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapanou, P.N. , Epidemiology of periodontal diseases: an update. J Int Acad Periodontol 1999, 1, 110–6. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, V.E.; et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors' Consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2009, 104, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa De Accioly Mattos, M.; et al. Coronary atherosclerosis and periodontitis have similarities in their clinical presentation. Frontiers in Oral Health 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of, P. , American Academy of Periodontology statement on risk assessment. J Periodontol 2008, 79, 202. [Google Scholar]

- Andriankaja, O.M.; et al. Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus using lipid-lowering agents have better periodontal health than non-users. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease, 2040. [Google Scholar]

- Andriankaja, O.M.; et al. Periodontal Disease, Local and Systemic Inflammation in Puerto Ricans with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines.

- Andriankaja, O.M.; et al. Systemic Inflammation, Endothelial Function, and Risk of Periodontitis in Overweight/Obese Adults. Biomedicines.

- Kinane, D.F.; et al. Humoral immune responses in periodontal disease may have mucosal and systemic immune features. Clin Exp Immunol 1999, 115, 534–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappin, D.F., A. M. McGregor, and D.F. Kinane, The systemic immune response is more prominent than the mucosal immune response in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol.

- Lin, E.C.; et al. Unraveling the Link between Periodontitis and Coronavirus Disease 2019: Exploring Pathogenic Pathways and Clinical Implications. Biomedicines.

- Loe, H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1993, 16, 329–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, T.; et al. Periodontal complications of hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus: Epidemiologic complexity and clinical challenge. Periodontol 2000 2018, 78, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimlich, R. What Is Long COVID? 2023.

- Yong, S.J. , Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis (Lond) 2021, 53, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, H.; et al. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, I. , Risk factors for periodontitis & peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 2022, 90, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, H.M.; et al. Identifying Factors Associated with Periodontal Disease Using Machine Learning. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2022, 12, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol 2018, 45, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizales-Sepulveda, E.F.; et al. Periodontal Disease, Systemic Inflammation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Heart Lung Circ 2018, 27, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Z.; et al. Epidemiologic relationship between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health.

- Abu-Shawish, G., J. Betsy, and S. Anil, Is Obesity a Risk Factor for Periodontal Disease in Adults? A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

- Jepsen, S., J. Suvan, and J. Deschner, The association of periodontal diseases with metabolic syndrome and obesity. Periodontol, 83.

- Rivas-Agosto, J.A. , Camacho-Monclova, D.M., Vergara, J.L., Vivaldi-Oliver, J., Andriankaja, O.M., Disparities in periodontal diseases occurrence among Hispanic population with Type 2 Diabetes: the LLIPDS Study. EC. Dental Science.

- Smith, H.; et al. Cross-sectional association among dietary habits, periodontitis, and uncontrolled diabetes in Hispanics: the LLIPDS study. Front Oral Health 2025, 6, 1468995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.M. , K, Janeway's immunobiology, in Garland Science. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sette, A. and S. Crotty, Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell 2021, 184, 861–880. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.H.; et al. T cell immunobiology and cytokine storm of COVID-19. Scand J Immunol 2021, 93, e12989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.E.; et al. Untuned antiviral immunity in COVID-19 revealed by temporal type I/III interferon patterns and flu comparison. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, P.S.; et al. Systems biological assessment of immunity to mild versus severe COVID-19 infection in humans. Science 2020, 369, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; et al. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell, 1036. [Google Scholar]

- Laing, A.G.; et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjadj, J.; et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science 2020, 369, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gomez, A.; et al. Dendritic cell deficiencies persist seven months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 2128–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.; et al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 2023, 623, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoni, V.; et al. An Inflammatory Profile Correlates With Decreased Frequency of Cytotoxic Cells in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 2272–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, B.; et al. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front Immunol 2020, 11, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharawi, H.; et al. The Prevalence of Gingival Dendritic Cell Subsets in Periodontal Patients. J Dent Res 2021, 100, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., P. Feng, and J. Slots, Herpesvirus-bacteria synergistic interaction in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2020, 82, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammil, et al., Association of interferon lambda-1 with herpes simplex viruses-1 and -2, Epstein-Barr virus, and human cytomegalovirus in chronic periodontitis. J Investig Clin Dent.

- Kajita, K.; et al. Quantitative messenger RNA expression of Toll-like receptors and interferon-alpha1 in gingivitis and periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2007, 22, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Immune response pattern across the asymptomatic, symptomatic and convalescent periods of COVID-19. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2022, 1870, 140736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell, 1489. [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtsev, I.; et al. Dysregulated Immune Responses in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients: A Comprehensive Overview. Viruses.

- Silva, M.J.A.; et al. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1001198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parackova, Z.; et al. Neutrophils mediate Th17 promotion in COVID-19 patients. J Leukoc Biol 2021, 109, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martonik, D.; et al. The Role of Th17 Response in COVID-19. Cells.

- De Biasi, S.; et al. Marked T cell activation, senescence, exhaustion and skewing towards TH17 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibabaw, T. , Inflammatory Cytokine: IL-17A Signaling Pathway in Patients Present with COVID-19 and Current Treatment Strategy. J Inflamm Res 2020, 13, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; et al. The role of interleukin-22 in lung health and its therapeutic potential for COVID-19. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 951107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcorn, J.F. , IL-22 Plays a Critical Role in Maintaining Epithelial Integrity During Pulmonary Infection. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenobia, C. and G. Hajishengallis, Basic biology and role of interleukin-17 in immunity and inflammation. Periodontol, 69.

- Bilich, T.; et al. T cell and antibody kinetics delineate SARS-CoV-2 peptides mediating long-term immune responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Sci Transl Med.

- Ibarrondo, F.J.; et al. Rapid Decay of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Persons with Mild Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1085–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, J.; et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol 2020, 5, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamayoshi, S.; et al. Antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 decline, but do not disappear for several months. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 32, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K.W.; et al. Longitudinal analysis shows durable and broad immune memory after SARS-CoV-2 infection with persisting antibody responses and memory B and T cells. Cell Rep Med 2021, 2, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; et al. Dynamics of TCR repertoire and T cell function in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Cell Discov 2021, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, A.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain antibody evolution after mRNA vaccination. Nature 2021, 600, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, E.M. and F.A. Arosa, CD8(+) T Cells in Chronic Periodontitis: Roles and Rules. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, V.; et al. A role for CD8+ T lymphocytes in osteoclast differentiation in vitro. Endocrinology 1996, 137, 2457–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; et al. Osteoclastogenesis is enhanced by activated B cells but suppressed by activated CD8(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol 2001, 31, 2179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G. and J.M. Korostoff, Revisiting the Page & Schroeder model: the good, the bad and the unknowns in the periodontal host response 40 years later. Periodontol 2000 2017, 75, 116–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kuri-Cervantes, L.; et al. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol.

- Aschenbrenner, A.C.; et al. Disease severity-specific neutrophil signatures in blood transcriptomes stratify COVID-19 patients. Genome Med 2021, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meizlish, M.L.; et al. A neutrophil activation signature predicts critical illness and mortality in COVID-19. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 1164–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbeke, L.; et al. Monocyte-driven atypical cytokine storm and aberrant neutrophil activation as key mediators of COVID-19 disease severity. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; et al. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: The Current Evidence and Treatment Strategies. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojyo, S.; et al. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm Regen 2020, 40, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, M.Z.; et al. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol 2020 20, 363–374. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.; et al. Self-sustaining IL-8 loops drive a prothrombotic neutrophil phenotype in severe COVID-19. JCI Insight.

- Frishberg, A.; et al. Mature neutrophils and a NF-kappaB-to-IFN transition determine the unifying disease recovery dynamics in COVID-19. Cell Rep Med 2022, 3, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. Temporal transcriptomic analysis using TrendCatcher identifies early and persistent neutrophil activation in severe COVID-19. JCI Insight.

- Jukema, B.N.; et al. Neutrophil and Eosinophil Responses Remain Abnormal for Several Months in Primary Care Patients With COVID-19 Disease. Front Allergy 2022, 3, 942699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, N. and M. Kesting, Cytokines in gingivitis and periodontitis: from pathogenesis to therapeutic targets. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1435054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W., Q. Wang, and Q. Chen, The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci 2019, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorch, S.K. and P. Kubes, An emerging role for neutrophil extracellular traps in noninfectious disease. Nat Med 2017, 23, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, L. and U. Kelter, Ultrasonography and scintigraphy of the liver in focal and diffuse disease. Acta Radiol 1987, 28, 165–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitkov, L.; et al. Periodontitis-Derived Dark-NETs in Severe Covid-19. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 872695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twaddell, S.H.; et al. The Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Respiratory Disease. Chest 2019, 156, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veras, F.P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID-19 pathology. J Exp Med.

- Zuo, Y.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight.

- Carmona-Rivera, C.; et al. Multicenter analysis of neutrophil extracellular trap dysregulation in adult and pediatric COVID-19. JCI Insight.

- Mohandas, S.; et al. Immune mechanisms underlying COVID-19 pathology and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabuschnig, S.; et al. Putative Origins of Cell-Free DNA in Humans: A Review of Active and Passive Nucleic Acid Release Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci.

- Vitkov, L.; et al. Extracellular neutrophil traps in periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 2009, 44, 664–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magan-Fernandez, A.; et al. Characterization and comparison of neutrophil extracellular traps in gingival samples of periodontitis and gingivitis: A pilot study. J Periodontal Res 2019, 54, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, C.; et al. Circulating levels of carbamylated protein and neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with periodontitis severity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot case-control study. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvin, A.; et al. Elevated Calprotectin and Abnormal Myeloid Cell Subsets Discriminate Severe from Mild COVID-19. Cell, 1401. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Pathogenic T-cells and inflammatory monocytes incite inflammatory storms in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl Sci Rev 2020, 7, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, M. and J.C. Martin, Author Correction: Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulert, G.S. and A.A. Grom, Pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome and potential for cytokine- directed therapies. Annu Rev Med 2015, 66, 145–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, R.; et al. Synergism of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma triggers inflammatory cell death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and cytokine shock syndromes. bioRxiv 2020.

- Swanson, K.V., M. Deng, and J.P. Ting, The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol 2019 19, 477–489.

- Junqueira, C.; et al. FcgammaR-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection of monocytes activates inflammation. Nature 2022, 606, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, H.K. and M.R. Mehra, COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020, 39, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, B.K.; et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 Protein in CD16+ Monocytes in Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 Months Post-Infection. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 746021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassler, K.; et al. The Myeloid Cell Compartment-Cell by Cell. Annu Rev Immunol 2019, 37, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnacker, S.; et al. Correction to: Mild COVID-19 imprints a long-term inflammatory eicosanoid- and chemokine memory in monocyte-derived macrophages. Mucosal Immunol 2022, 15, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernichel-Gorbach, E.; et al. Host responses in patients with generalized refractory periodontitis. J Periodontol 1994, 65, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, L.; et al. The secretion of PGE2, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and TNF alpha by adherent mononuclear cells from early onset periodontitis patients. J Periodontol 1994, 65, 139–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; et al. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol 1996, 67(10 Suppl), 1123–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ptasiewicz, M.; et al. Armed to the Teeth-The Oral Mucosa Immunity System and Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci.

- Kudo, O.; et al. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-11 support human osteoclast formation by a RANKL-independent mechanism. Bone 2003, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutzan, N.; et al. On-going Mechanical Damage from Mastication Drives Homeostatic Th17 Cell Responses at the Oral Barrier. Immunity 2017, 46, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahammam, M.A. and M.S. Attia, Effects of Systemic Simvastatin on the Concentrations of Visfatin, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha, and Interleukin-6 in Gingival Crevicular Fluid in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Periodontitis. J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 8481735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitompul, S.I.; et al. Analysis of the Effects of IL-6 -572 C/G, CRP -757 A/G, and CRP -717 T/C Gene Polymorphisms; IL-6 Levels; and CRP Levels on Chronic Periodontitis in Coronary Artery Disease in Indonesia. Genes (Basel).

- Hobbins, S.; et al. Is periodontitis a comorbidity of COPD or can associations be explained by shared risk factors/behaviors? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017, 12, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center, D.M. and W. Cruikshank, Modulation of lymphocyte migration by human lymphokines. I. Identification and characterization of chemoattractant activity for lymphocytes from mitogen-stimulated mononuclear cells. J Immunol 1982, 128, 2563–8. 128.

- Loretelli, C.; et al. PD-1 blockade counteracts post-COVID-19 immune abnormalities and stimulates the anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune response. JCI Insight.

- Shuwa, H.A.; et al. Alterations in T and B cell function persist in convalescent COVID-19 patients. Med.

- Szabo, P.A.; et al. Longitudinal profiling of respiratory and systemic immune responses reveals myeloid cell-driven lung inflammation in severe COVID-19. Immunity.

- Zhang, J.Y.; et al. Single-cell landscape of immunological responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phetsouphanh, C.; et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, M.C.; et al. Chronic inflammation, neutrophil activity, and autoreactivity splits long COVID. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Files, J.K.; et al. Sustained cellular immune dysregulation in individuals recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Invest.

- Daugherty, S.E.; et al. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, A.; et al. One-Year Adverse Outcomes Among US Adults With Post-COVID-19 Condition vs Those Without COVID-19 in a Large Commercial Insurance Database. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e230010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkova, A.; et al. Post COVID-19 Syndrome in Patients with Asymptomatic/Mild Form. Pathogens.

- Maglietta, G.; et al. Prognostic Factors for Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med.

- Sandler, C.X.; et al. Long COVID and Post-infective Fatigue Syndrome: A Review. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021, 8, ofab440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A. , Wamil, M,Kapur,S, Alberts, J, Badley, A.D., Decker, G.A., Rizza,S.A.,Banerjee, R., Banerjee, A., Multi-organ impairment in low-risk individuals with long COVID. medRxiv.

- Sudre, C.H.; et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, M.I. , Comparison of neutrophil functions in aggressive and chronic periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2010, 53, 124–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luntzer, K.; et al. Increased Presence of Complement Factors and Mast Cells in Alveolar Bone and Tooth Resorption. Int J Mol Sci.

- Vernal, R.; et al. High expression levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand associated with human chronic periodontitis are mainly secreted by CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Periodontol 2006, 77, 1772–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, M.J.; et al. Long-term SARS-CoV-2-specific immune and inflammatory responses in individuals recovering from COVID-19 with and without post-acute symptoms. Cell Rep 2021, 36, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynne, P.; et al. Long COVID following mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: characteristic T cell alterations and response to antihistamines. J Investig Med 2022, 70, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlefield, K.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associate with inflammation and reduced lung function in pulmonary post-acute sequalae of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, B.; et al. Immuno-proteomic profiling reveals aberrant immune cell regulation in the airways of individuals with ongoing post-COVID-19 respiratory disease. Immunity.

- Woodruff, M.C.; et al. Extrafollicular B cell responses correlate with neutralizing antibodies and morbidity in COVID-19. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell.

- Gold, J.E.; et al. Investigation of Long COVID Prevalence and Its Relationship to Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation. Pathogens.

- Alramadhan, S.A.; et al. Oral Hairy Leukoplakia in Immunocompetent Patients Revisited with Literature Review. Head Neck Pathol 2021, 15, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, B.J.H.; et al. EBV Association with Lymphomas and Carcinomas in the Oral Compartment. Viruses.

- Maulani, C.; et al. Association between Epstein-Barr virus and periodontitis: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0258109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastard, P.; et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science, 6515. [Google Scholar]

- Combes, A.J.; et al. Publisher Correction: Global absence and targeting of protective immune states in severe COVID-19. Nature 2021, 596, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; et al. Human genetic and immunological determinants of critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Nature 2022, 603, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, Y.; et al. Innate immune sensing of coronavirus and viral evasion strategies. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowery, S.A., A. Sariol, and S. Perlman, Innate immune and inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2: Implications for COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1052–1062. 29.

- Schultze, J.L. and A.C. Aschenbrenner, COVID-19 and the human innate immune system. Cell, 1671. [Google Scholar]

- Merad, M., A. Subramanian, and T.T. Wang, An aberrant inflammatory response in severe COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1043–1047. 29.

- Wang, E.Y.; et al. Diverse functional autoantibodies in patients with COVID-19. Nature 2021, 595, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.S.; et al. The intersection of COVID-19 and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest.

- Mishra, P.K.; et al. Vaccination boosts protective responses and counters SARS-CoV-2-induced pathogenic memory B cells. medRxiv 2021.

- Chang, S.E.; et al. New-onset IgG autoantibodies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, W.H. and L. Steinman, Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; et al. Low Prevalence of Interferon alpha Autoantibodies in People Experiencing Symptoms of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Conditions, or Long COVID. J Infect Dis 2023, 227, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seessle, J.; et al. Persistent Symptoms in Adult Patients 1 Year After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2022, 74, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; et al. Lack of Antinuclear Antibodies in Convalescent Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients With Persistent Symptoms. Clin Infect Dis 2022, 74, 2083–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M. , The four most urgent questions about long COVID. Nature 2021, 594, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, R.; et al. Antibodies against Spike protein correlate with broad autoantigen recognition 8 months post SARS-CoV-2 exposure, and anti-calprotectin autoantibodies associated with better clinical outcomes. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 945021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervia-Hasler, C.; et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid. Science 2024, 383, eadg7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; et al. Complement-Dependent Mechanisms and Interventions in Periodontal Disease. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of complement component 5 and periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 2010, 45, 301–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; et al. Prioritization of candidate genes for periodontitis using multiple computational tools. J Periodontol 2014, 85, 1059–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; et al. The angiotensin converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas Receptor axis as a key player in alveolar bone remodeling. Bone 2019, 128, 115041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azzawi, I.S. and N.S. Mohammed, The Impact of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE-2) on Bone Remodeling Marker Osteoprotegerin (OPG) in Post-COVID-19 Iraqi Patients. Cureus 2022, 14, e29926. [Google Scholar]

- Creecy, A.; et al. COVID-19 and Bone Loss: A Review of Risk Factors, Mechanisms, and Future Directions. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2024, 22, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapra, L.; et al. Long-term implications of COVID-19 on bone health: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Inflamm Res 2022, 71, 1025–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces inflammatory bone loss in golden Syrian hamsters. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; et al. Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med 2006, 203, 2673–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.A.; et al. Elevated vascular transformation blood biomarkers in Long-COVID indicate angiogenesis as a key pathophysiological mechanism. Mol Med 2022, 28, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, G.; et al. Reduction in ACE2 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells during COVID-19 - implications for post COVID-19 conditions. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis. Cureus 2022, 14, e22770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.C.; et al. COVID-19 Mimics Pulmonary Dysfunction in Muscular Dystrophy as a Post-Acute Syndrome in Patients. Int J Mol Sci.

- Banerjee, S.; et al. An updated patent review of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors (2021-present). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2023, 33, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulet, A.; et al. Biomarkers of Fibrosis in Patients with COVID-19 One Year After Hospital Discharge: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2023, 69, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, S., P. K. Cholan, and D.J. Victor, An emphasis of T-cell subsets as regulators of periodontal health and disease. J Clin Transl Res.

- Luchian, I.; et al. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13) in Periodontal and Peri-Implant Pathological Processes. Int J Mol Sci.

- da Silva-Neto, P.V.; et al. sTREM-1 Predicts Disease Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: Involvement of Peripheral Blood Leukocytes and MMP-8 Activity. Viruses.

- Gelzo, M.; et al. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) 3 and 9 as biomarkers of severity in COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, E. and C. Fernandez-Patron, Targeting MMP-Regulation of Inflammation to Increase Metabolic Tolerance to COVID-19 Pathologies: A Hypothesis. Biomolecules.

- Cutler, C.W. and Y.T. Teng, Oral mucosal dendritic cells and periodontitis: many sides of the same coin with new twists. Periodontol 2007, 45, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, A.; et al. Dendritic cells and their role in periodontal disease. Oral Dis 2014, 20, 119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.; et al. Evidence for a cross-talk between human neutrophils and Th17 cells. Blood 2010, 115, 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutzan, N.; et al. Characterization of the human immune cell network at the gingival barrier. Mucosal Immunol 2016, 9, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutsopoulos, N.M.; et al. Defective neutrophil recruitment in leukocyte adhesion deficiency type I disease causes local IL-17-driven inflammatory bone loss. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 229ra40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotake, S.; et al. Role of osteoclasts and interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: crucial 'human osteoclastology'. J Bone Miner Metab 2012, 30, 125–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; et al. The potential role of interleukin-17 in the immunopathology of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2005, 32, 369–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, C.R.; et al. Evidence of the presence of T helper type 17 cells in chronic lesions of human periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2009, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuta, J.; et al. Dynamic visualization of RANKL and Th17-mediated osteoclast function. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 866–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T., M. Donati, and N. Zitzmann, B cells in periodontitis: friends or enemies? Periodontol 2000 2007, 45, 51–66. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, J.R. , T- and B-cell subsets in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2015, 69, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, A. , Is There a Similarity in Serum Cytokine Profile between Patients with Periodontitis or 2019-Novel Coronavirus Infection?-A Scoping Review. Biology (Basel).

- Bemquerer, L.M.; et al. Clinical, immunological, and microbiological analysis of the association between periodontitis and COVID-19: a case-control study. Odontology 2024, 112, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; et al. Acute coronavirus infection triggers a TNF-dependent osteoporotic phenotype in mice. Life Sci 2023, 324, 121750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.Y.; et al. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis Poverty 2020, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scialo, F.; et al. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torge, D.; et al. Histopathological Features of SARS-CoV-2 in Extrapulmonary Organ Infection: A Systematic Review of Literature. Pathogens.

- Bourgonje, A.R.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Pathol 2020, 251, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; et al. Viral persistence, reactivation, and mechanisms of long COVID. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; et al. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboudounya, M.M. and R.J. Heads, COVID-19 and Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4): SARS-CoV-2 May Bind and Activate TLR4 to Increase ACE2 Expression, Facilitating Entry and Causing Hyperinflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2021, 2021, 8874339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell.

- Senapati, S.; et al. Contributions of human ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in determining host-pathogen interaction of COVID-19. J Genet.

- Sakaguchi, W.; et al. Existence of SARS-CoV-2 Entry Molecules in the Oral Cavity. Int J Mol Sci.

- Zou, X.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med 2020, 14, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.Y.; et al. Potential effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 133, 111064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract. Cell.

- Zhuang, M.W.; et al. Increasing host cellular receptor-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression by coronavirus may facilitate 2019-nCoV (or SARS-CoV-2) infection. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 2693–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.C.; et al. Cigarette Smoke Exposure and Inflammatory Signaling Increase the Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in the Respiratory Tract. Dev Cell.

- Zhang, J., K. M. Tecson, and P.A. McCullough, Endothelial dysfunction contributes to COVID-19-associated vascular inflammation and coagulopathy. Rev Cardiovasc Med.

- Ziegler, C.G.K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 Is an Interferon-Stimulated Gene in Human Airway Epithelial Cells and Is Detected in Specific Cell Subsets across Tissues. Cell, 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, M.; et al. Inflammation Triggered by SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 Augment Drives Multiple Organ Failure of Severe COVID-19: Molecular Mechanisms and Implications. Inflammation 2021, 44, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, H.K., P. Libby, and P.M. Ridker, COVID-19 - A vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med.

- Patel, S.K.; et al. Plasma ACE2 activity is persistently elevated following SARS-CoV-2 infection: implications for COVID-19 pathogenesis and consequences. Eur Respir J.

- Proal, A.D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nat Immunol 2023, 24, 1616–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaebler, C.; et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 591, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; et al. Distinguishing features of Long COVID identified through immune profiling. medRxiv 2022. [CrossRef]

- de Melo, G.D.; et al. COVID-19-related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Sci Transl Med.

- Yao, Q.; et al. Long-Term Dysfunction of Taste Papillae in SARS-CoV-2. NEJM Evid.

- Gomes, S.C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in dental biofilms: Supragingival and subgingival findings from inpatients in a COVID-19 intensive care unit. J Periodontol 2022, 93, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, J.T., B. M. Warner, and K.M. Byrd, The "oral" history of COVID-19: Primary infection, salivary transmission, and post-acute implications. J Periodontol, 1357. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, D.; et al. Differences in saliva ACE2 activity among infected and non-infected adult and pediatric population exposed to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect 2022, 85, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci 2020, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, A., H. Nowzari, and J. Slots, Herpesviruses in periodontal pocket and gingival tissue specimens. Oral Microbiol Immunol.

- Cappuyns, I., P. Gugerli, and A. Mombelli, Viruses in periodontal disease - a review. Oral Dis.

- Badran, Z.; et al. Periodontal pockets: A potential reservoir for SARS-CoV-2? Med Hypotheses 2020, 143, 109907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; et al. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Correlates With Long COVID-19 at One-Year After Discharge. J Korean Med Sci 2023, 38, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; et al. Longitudinal alterations of the gut mycobiota and microbiota on COVID-19 severity. BMC Infect Dis 2022, 22, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, V.; et al. Mild SARS-CoV-2 infection results in long-lasting microbiota instability. mBio 2023, 14, e0088923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollner, A.; et al. Postacute COVID-19 is Characterized by Gut Viral Antigen Persistence in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology.

- He, K.Y.; et al. Development and management of gastrointestinal symptoms in long-term COVID-19. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1278479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paine, S.K.; et al. Temporal dynamics of oropharyngeal microbiome among SARS-CoV-2 patients reveals continued dysbiosis even after Viral Clearance. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, J.P.; et al. Inflammation-type dysbiosis of the oral microbiome associates with the duration of COVID-19 symptoms and long COVID. JCI Insight.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).