1. Introduction

The establishment of the Australia–United Kingdom–United States (AUKUS) security partnership in September 2021 represents one of the most significant developments in contemporary Indo-Pacific geopolitics. Centreing on the transfer of nuclear-powered submarine technology, the initiative embodies a new form of strategic alignment among the three partners. Since its announcement, AUKUS has attracted widespread international attention, sparking debates on security, sovereignty, and the potential reshaping of regional and global order.

Existing scholarship has devoted considerable attention to AUKUS from multiple perspectives. The literature has broadly explored definitional debates regarding what AUKUS represents within international relations theory. Researchers have also examined its driving factors in each of the three countries. Policy-oriented studies have concentrated on its global implications, particularly for the Indo-Pacific and the European Union. Some research has addressed public opinion, but primarily through conventional surveys focusing on narrow issues, such as support for nuclear submarines, regional impacts, costs, or the alliance’s prospective trajectory. These studies, however, remain geographically limited—predominantly to Australia—and methodologically constrained.

Against this backdrop, this paper advances a new line of inquiry by systematically analysing public opinion on AUKUS across Australia, the UK, and the US using Google Trends data. Unlike traditional surveys, this approach enables real-time, large-scale, and comparative assessment of public discourse, capturing patterns that would otherwise remain inaccessible. The paper contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it introduces a novel methodological perspective on studying public opinion in international relations through digital trace data. Second, it extends the scope of AUKUS scholarship beyond elite and policy-level analyses to examine mass-level perceptions and their interrelations. Third, it provides new empirical evidence on the dynamics linking public opinion and foreign policy.

The structure of this paper is as follows.

Section 1 reviews relevant literature on a range of issues, including definitions, theoretical and practical origins, implementation, global implications, and public opinion.

Section 2 introduces the study’s data source, Google Trends, addressing its practical considerations and interpretations.

Section 3 analyses public opinion in Australia, the UK, and the US using Google Trends data, focusing on salient issues, driving factors, and interrelations.

Section 4 draws policy implications from the findings on public opinion, and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Existing literature on AUKUS has primarily focused on conceptual analysis, the origins of the partnership in theory and practice, its implementation, its global implications, and public opinion, with a particular emphasis on Australia.

First, regarding the definition or concept of AUKUS, Shoebridge (2021) describes it as an essentially trilateral technology accelerator aimed at enhancing the military capabilities of Australia, the UK, and the US. It is not merely a pact for sharing nuclear submarine technology with Australia, nor is it a new military alliance or an effort to sideline other multilateral mechanisms, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue involving India, the US, Japan, and Australia, the ASEAN or East Asia Summit, and the Five Eyes intelligence partnership. Markowski, Wylie, and Chand (2024) further argue that AUKUS shifts the focus from deterrence to strengthening partner military capabilities, rather than simply responding to attacks. The partnership follows a two-pronged strategy: Pillar 1 aims to enhance Australia’s military through US/UK nuclear submarines, while Pillar 2 seeks to advance defence cooperation in cyber, AI, quantum technologies, and undersea capabilities (Koga, 2025).

Second, various studies have examined the sources or motivations behind AUKUS. Theoretically, it can be interpreted through frameworks such as balancing (Türkcan, 2022), tactical hedging (Koga, 2025), minilateral grouping (Chan and Rublee, 2024), world-systems theory (Kurt, Tüysüzoğlu, and Özgen, 2022), and mutant neoliberalism (2025). In practice, China has often been cited as a major factor (Shoebridge, 2021), though the significance varies. In Australia, it is widely believed that a deteriorating strategic environment vis-à-vis China was a key driver of the decision to join AUKUS (McDougall, 2023; Kumar, 2024; Markowski, Wylie, and Chand, 2024). Bisley (2024) notes that between 2016 and 2020, China was perceived as a hostile actor interfering in Australian politics and disrupting the regional strategic balance. By mid-2020, Australia assessed that the ‘strategic warning time’ for major conflict had drastically shortened, positioning China as the principal source of risk. From mid-2022, the centre-left Labor Party signalled little substantive change in the direction of its international policy. Beyond the China factor, Rees (2025) argues that Australia’s decision to join AUKUS reflects an effort to preserve its ‘Self’ identity by stabilising ties with ‘great and powerful friends’, while Clayton and Newman (2023) highlight the influence of Australia’s settler-colonial positionality.

In the UK, the drivers of AUKUS are diverse. Shoebridge (2021) argues that AUKUS forms part of the UK’s post-Brexit “Global Britain” ambition, a view echoed by Cornish (2021), who suggests that the partnership validates this stance. According to Liz Truss, then Foreign Secretary and later Prime Minister, AUKUS represents a clear example of “Global Britain in action” (Truss, 2021). McDougall (2023) identifies the rise of a more assertive China as a factor influencing the UK’s decision, although, given the UK’s geographic distance from the Indo-Pacific, this concern is primarily mediated through its special relations with the US. Markowski, Wylie, and Chand (2024) note that AUKUS provides the UK with an opportunity to deepen its strategic ties with the US. Haugevik (2023) concludes that the Anglosphere and the Euro-Atlantic form the foundations of the “Global Britain” narrative. Puri (2024) emphasises the commercial motivations underpinning the UK’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific, alongside regional security considerations focused on deterring China. Furthermore, Markowski, Wylie, and Chand (2024) argue that AUKUS supports the UK in achieving economies of scale and broadening its export base, while McDougall (2023) highlights the integration of the China factor into Global Britain’s security framework. In summary, several factors potentially drive the UK’s participation in AUKUS, including cultural ties via the Anglosphere, strategic deterrence of China, diplomatic alignment with Global Britain policy, and commercial trade expansion. These factors are not mutually exclusive and will be empirically examined in a later section.

In the US, the primary driver of AUKUS is straightforward: China. As noted by Türkcan (2022), AUKUS is widely regarded as part of the US effort to counter Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific. China was characterised as a strategic rival during the Trump–Pence administration and as the sole competitor capable of challenging the US-led international system—through its diplomatic, economic, and military power—during the Biden–Harris administration. Within the Indo-Pacific, US concerns centre on China’s assertiveness, which is perceived as a major threat to regional stability.

Third, several studies have explored practical implementation issues, including the US export control system (Greenwalt and Corben, 2023), production, costs, and personnel challenges (Childs, 2023), the integration of data analytics and AI into joint exercises (Wyatt et al., 2024), and the legal risks associated with sharing military technology for use on and under the ocean (McKenzie and Massingham, 2023).

Fourth, a substantial body of research has examined the regional and global implications of AUKUS. As this paper does not focus on these issues, the review is brief. For Australia, AUKUS may further align its defence policy with the US (O’Connor, Cox, and Cooper, 2023; Cox, Cooper, and O’Connor, 2023; Caverley, 2023) and influence aspects of Australians’ daily lives (Rainnie, 2023). For China, implications include increased nuclear risks, containment strategies, geopolitical bloc formation, alienation, a potential new Cold War, and regional arms racing (Tzinieris, Leoni, and Blachford, 2024). Other studies have considered impacts on Japan (George Mulgan, 2024), India (Tzinieris, Chauhan, and Athanasiadou, 2023), ASEAN (Umar and Santoso, 2023), New Zealand and Pacific Islands (Smith and Bland, 2024; McDougall), France (Holland and Staunton, 2024) and the EU (Perot, 2021), Canada (Carvin and Juneau, 2023), and the wider international community (Barnes and Makinda, 2022).

Fifth, as AUKUS is an Australian initiative, studies on related public opinion have primarily focused on Australia. Survey questions can be categorised into four types: those concerning the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, its impacts on security and the economy, its costs, and its future delivery. Regarding support for acquiring nuclear-powered submarines, various surveys indicate that a majority of Australians are in favour1. Concerning its impact, fewer than half of respondents believe that AUKUS will make Australia safer2; while more people are supportive than opposed, a large proportion remain uncertain. Similarly, in terms of economic impact, Australians are more likely to perceive AUKUS as beneficial for job creation than not, although substantial uncertainty persists3. Regarding costs, more Australians express concern about the high expenditure than believe it is justified4, and for delivery, more are worried about delays than confident in timely implementation5. Given the technical nature of the latter three issues, it is reasonable to assume that many Australians may lack the expertise to make fully informed judgements, which likely explains the high proportion of uncertain responses. A survey on British public opinion, conducted in January 2025, found that more respondents agreed that AUKUS could enhance the UK’s security, competitiveness, and deter China’s aggression than disagreed, although around 30 per cent remained unsure (Gaston, 2025).

This study employs Google Trends data to measure public opinion, with a focus on its relation to foreign policy and the interconnections among Australia, the UK, and the US. A comparison between Google Trends-based public opinion and traditional survey results is presented in the following section.

3. Data Source

This study uses Google Trends as its data source. Google Trends (

https://trends.google.com/trends/) is a tool developed by Google to track the popularity of search queries across different regions and languages. The platform provides anonymized, categorized, and aggregated data, ensuring privacy while organizing search queries into meaningful topics for analysis. Trends can be examined on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. A notable feature of Google Trends is the normalization of search data by time and location, allowing meaningful comparisons across dates, countries, or cities. Search interest is expressed numerically, with the peak popularity in a specific region and time period set at 100. A value of 50 indicates that the term’s popularity was half that of its peak, while a score of 0 indicates insufficient data to measure interest. Google Trends offers two types of searches: term searches and topic searches. Term searches retrieve results that exactly match the words entered in a specific language. In contrast, topic searches aggregate different terms that convey the same concept across multiple languages, allowing for a broader and more conceptually unified analysis.

Several practical issues arise. First, it could be argued that internet users are not demographically representative of the general population, which may result in the underrepresentation of certain groups. In the US, this is unlikely to pose a major issue6. Moreover, internet penetration rates have risen since 2021 to 91% in the US7, 97% in Australia8, and 96% in the UK9. This indicates that demographic differences between internet users and the general populations in these three countries are diminishing. Salganik (2019) highlights non-representativeness as a typical characteristic of big data, emphasizing that this limitation does not reduce its scientific utility. He offers multiple examples demonstrating that valid inferences and predictions can still be drawn, challenging the common assumption that representativeness is a prerequisite for reliable analysis. Second, Google Trends data can be unstable due to random sampling and occasional algorithm updates. Using multiple draws improves stability. In this study, all datasets were collected over 12 samples on generally 12 different days10 for low-variation data, and 20 samples on 20 different days11 for high-variation data, with the arithmetic average then calculated. Any algorithmic changes are assumed to primarily affect forecasting but have minimal impact on causal inference.

Google Trends has been utilized in hundreds of studies across disciplines including information systems and computer science, healthcare, economics and finance, and political science

12. From a communications perspective, Google Trends is often viewed as a measure of the public agenda, reflecting the issues that the public perceives as important. In this study, as in several of the author’s other works (available upon request), Google Trends results are conceptualized as reflecting the agenda-setting effect

13, defined as “not the result of receiving one or a few messages but... the aggregated impact of a very large number of messages, each of which has a different content but all of which deal with the same issue” (Dearing & Rogers, 1996). Accordingly, Google Trends can be interpreted as a measure of public priorities shaped by policy developments, media coverage, and individuals’ attention to specific issues. Google Trends can also be used to track narratives, defined as discourses with a clear sequence that link events meaningfully and offer insights into the world or individual experiences. The relations among these narratives, as shown in the regression results in

Section 4, reflect public opinion, whereas the “public agenda” refers to the issues or topics considered important by the public at a given time.

Compared with traditional polls, Google Trends offers several advantages. First, regarding timeframe and granularity, Google Trends provides real-time or near-real-time data, capturing trends over hours, days, or years. This allows researchers to track shifts in interest quickly, including responses to events. In contrast, polls are typically conducted at specific points in time, providing only a snapshot of opinion. Longitudinal polls can reveal trends but are less frequent and slower to produce, and they cannot capture historical opinions beyond the survey period. Second, in terms of question scope, Google Trends allows exploration of a wide range of topics, whereas polls are limited to pre-defined questions, which can be influenced by wording or framing. Third, regarding accuracy and bias, both methods have potential limitations. However, Google Trends reflects actual search behavior, which may better capture genuine interest than polls, which rely on respondents’ willingness to provide honest answers. Fourth, Google Trends data are free and publicly accessible, while conducting polls can be costly and time-consuming.

4. Public Opinions

This section examines three aspects of public opinion in Australia, the UK, and the US: issue salience, driving factors, and interconnections. The policy implications of these findings are analysed in the subsequent section.

4.1. Salient Issues

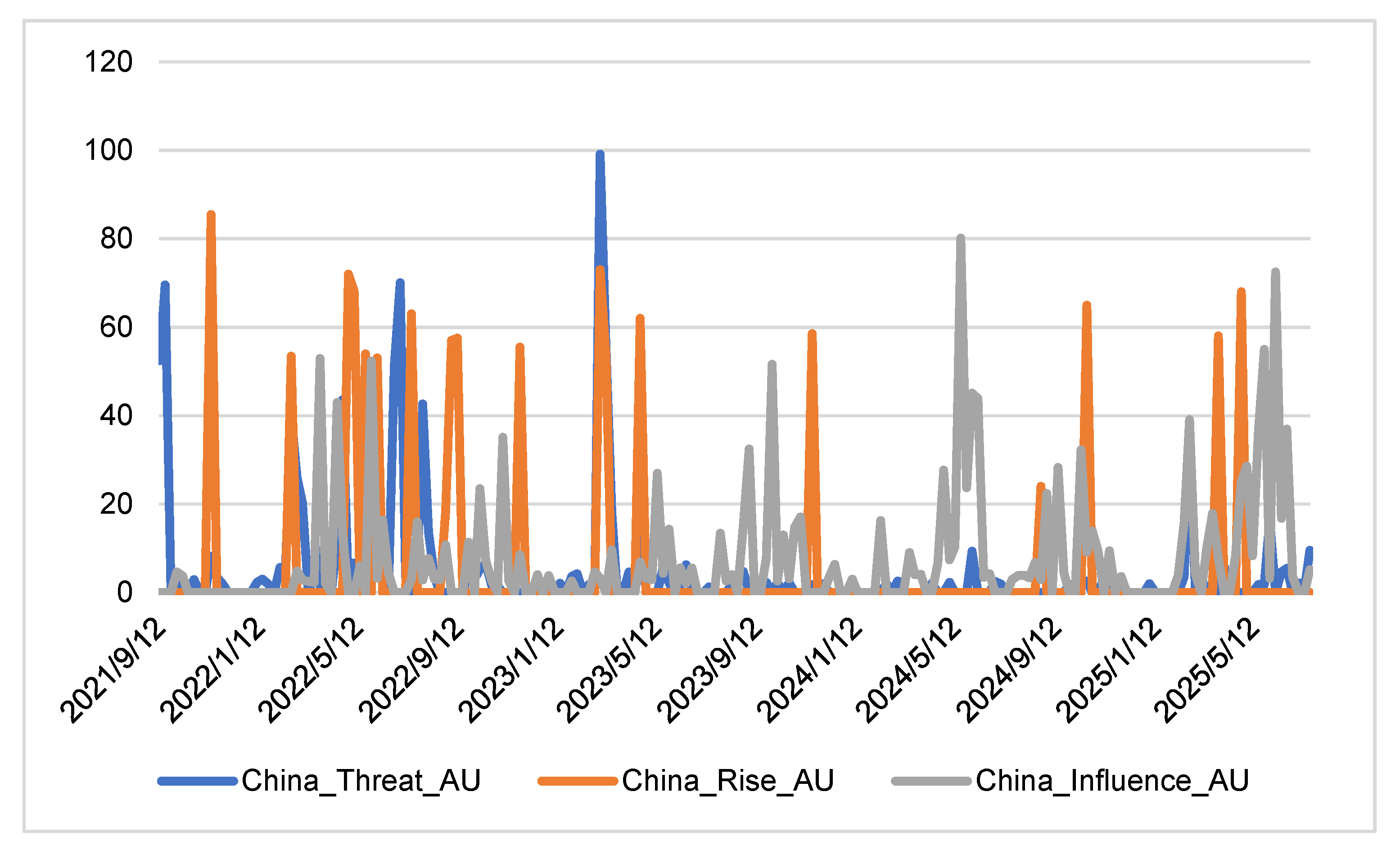

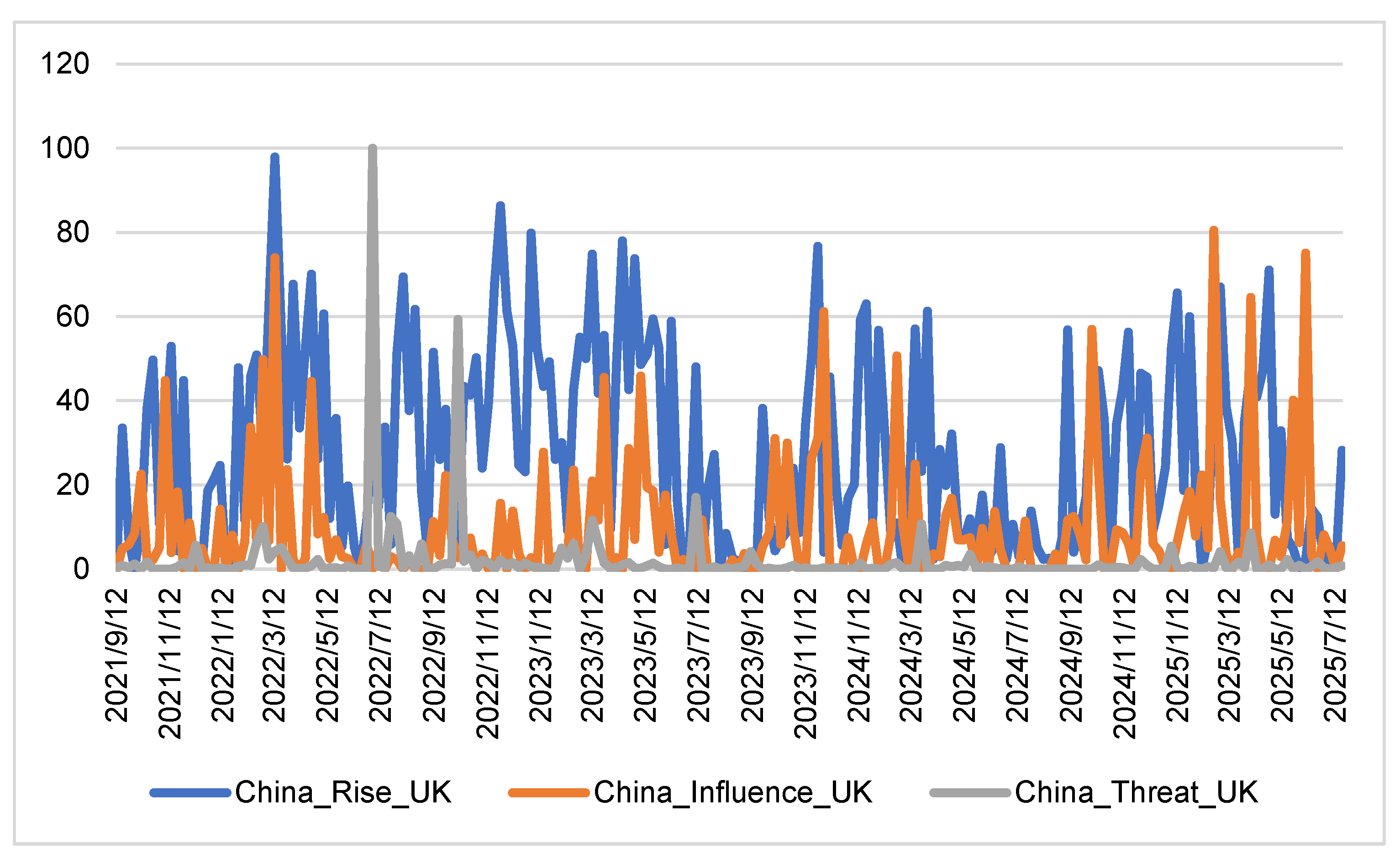

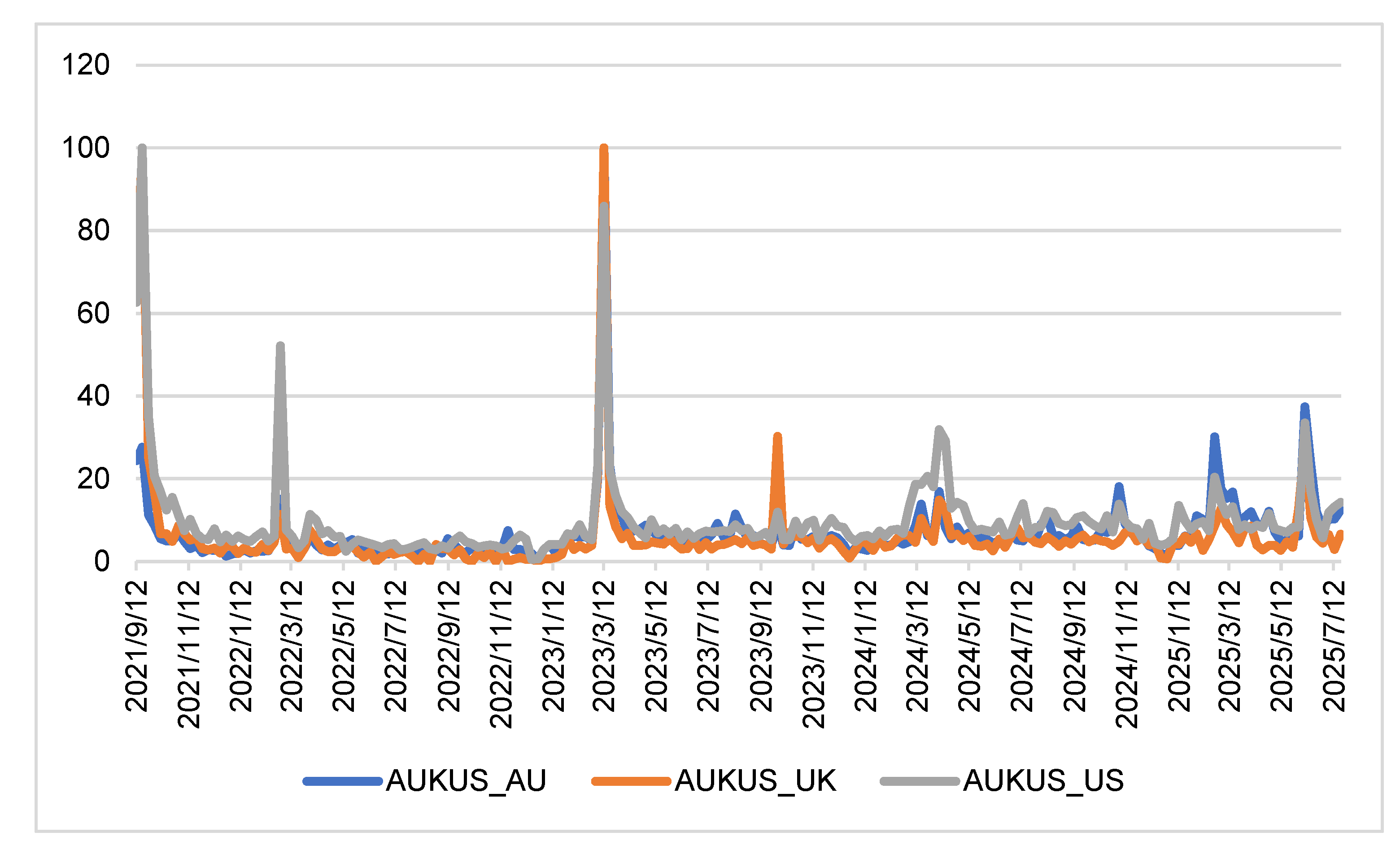

Figure 1 illustrates the AUKUS narratives in Australia, the UK, and the US, based on the arithmetic average of 12 different samples retrieved from Google Trends. The analysis focuses on the AUKUS topic rather than a specific search term. Observations prior to the week of 12 September 2021 yield zero values, consistent with the timeline of AUKUS’s development.

Weekly Google Trends datasets from 12 September 2021 to 20 July 2025

In Australia, the largest peak in public attention occurred in the week of 12 March 2023, following the announcement of AUKUS details in San Diego on 14 March 2023. Various official statements were issued, including from the Prime Minister14 and the defence minister15. While the government emphasised job creation (Greene, 2023) and industrial transformation16, analysts focused on broader implications, such as geopolitical consequences (Rachman, 2023), risks (Meadows, 2023), and, notably, costs. Estimated between A$268 billion (US$200 billion) and A$368 billion (US$273 billion) over the next three decades—Australia’s largest-ever defence expenditure (Groch, 2023)—the topic attracted extensive public discussion (Varghese, 2023; Quiggin, 2023). The second-largest peak occurred in the week of 8 June 2025, driven by US President Trump’s decision to review the AUKUS deal, widely covered in sources such as Tillett (2025) and 7news.com.au (2025). While Australian officials and some analysts expressed confidence that the partnership would continue smoothly (Ryan and Gramenz, 2025), others advocated abandoning the initiative (Shortis, 2025; Australian Institute, 2025). The third-largest peak occurred in the week of 23 February 2025, prompted by reports that, when asked about AUKUS, Trump replied, “What does that mean?” This story received extensive coverage in Australia, including by 9news.com.au (2025), Harris (2025), Vyas (2025), and McIlroy and Harris (2025).

In the UK, the largest peak in public attention occurred in the week of 12 March 2023, following the finalisation of the AUKUS deal on 13 March 202317. The UK government released several policy papers on AUKUS18, emphasising job creation and the country’s contribution to global security (Hughes, 2023). Analysts assessed its broader implications for the UK: O’Grady (2023) argued that AUKUS could strengthen close relations between China and Russia while creating business opportunities, whereas Howe (2023) highlighted the substantial R&D opportunities under Pillar 2 and noted that the initiative demonstrates the credibility of British military involvement in the Indo-Pacific, alongside the Anglosphere, forming two of the three post-Brexit pillars of British foreign policy (the third being Europe). The second-largest peak occurred in the week of 19 September 2021, followed by the third-largest in the week of 12 September 2021, both driven by the initial announcement of AUKUS on 15 September 2021. Coverage focused on its background19 and reactions from various parties20, with the UK government releasing multiple documents21. Several reports emphasised the China factor, including those by The Sun22, BBC23, and The Express24. Analyses25 also discussed France’s role in AUKUS (Keiger, 2021), its implications for the EU (Whitman, 2021; Münchau, 2021), and potential business opportunities for the UK (Tovey, 2021). The fourth-largest peak occurred in the week of 1 October 2023, driven primarily by news that British defence giant BAE Systems had secured an AUKUS-related contract worth £3.95 billion (US$4.84 billion) 26.

In the US, the largest peak in public attention occurred in the week of 19 September 2021, followed by the third-largest peak in the week of 12 September 2021 and the fifth-largest in the week of 26 September 2021. These surges were primarily driven by the announcement of the AUKUS deal on 15 September 2021, accompanied by official press releases from the White House27 and extensive media coverage28. Discussions centred on three main themes: great-power competition between the US and China (Mount and Jackson, 2021; Pager and Gearan, 2021; Briançon, 2021), transatlantic relations and coordination (Kupchan, 2021; Scheffer and Quencez, 2021; Hemphill, 2021), and potential nuclear proliferation issues (Acton, 2021; Roblin, 2021; Das, 2021). The second-largest peak occurred in the week of 12 March 2023, following the release of detailed AUKUS plans on 13 March 2023. US officials, including the White House29, the Department of Defence30, and the Department of State31, issued statements, and media outlets such as The Guardian US32, Reuters33, NPR34, and NBC News35 reported on the deal, highlighting it as “the biggest single investment in Australia's defence capability in history.” Analysts focused on great-power competition, with commentary framing AUKUS as “an emerging alliance at sea,” 36 “an Indo-Pacific NATO,” 37 and a potential shift in the global balance of power38, alongside discussions of its broader significance and challenges39. The fourth-largest peak occurred in the week of 27 February 2022, driven mainly by speeches delivered on 4 March 2022 by Australia’s incumbent Prime Minister40 and opposition leader41 prior to the election, both expressing support for the AUKUS programme, as well as accompanying news reports and analyses42.

In summary, public concerns regarding AUKUS differ across Australia, the UK, and the US. The Australian public focused primarily on the costs and uncertain future of the initiative. The British public was chiefly concerned with the UK’s foreign policy stance and potential business opportunities arising from AUKUS. In contrast, the US public concentrated on geopolitical and strategic considerations.

4.2. Driving Factors

As discussed in the literature review, multiple factors drive AUKUS at the policy level. This section examines the significance of these factors at the public level in Australia, the UK, and the US. Before proceeding, several issues concerning variables and data must be addressed.

First, it is widely acknowledged that China constitutes a major driving factor for all three countries. Three variables are used to capture distinct dimensions. China’s rise refers to the structural or systemic increase in China’s capabilities—economic, military, technological, and diplomatic—relative to other states in the international system, focusing on objective indicators such as GDP growth, military modernisation, and participation in international institutions. China’s influence captures China’s capacity to shape the preferences, decisions, or behaviour of other states, institutions, or non-state actors through political, economic, cultural, or diplomatic means, emphasising the effects of China’s actions on others rather than its internal capabilities; these effects may be benign or coercive. China as a threat denotes the perception or reality that China’s military, economic, or political actions pose risks to the security, sovereignty, or interests of other states. This threat framing is normative and risk-based, highlighting potential harm and often motivating defensive or counterbalancing policies. Other variables are discussed in subsequent sections.

Second, the choice of search terms or topics in Google Trends is critical. For China’s rise, the term “China rise” was selected, as alternatives such as “China’s rise,” “rising China,” or “rise of China” yielded fewer results across all three countries. For China’s influence, the term “China influence” was used, which proved more popular than alternatives like “Chinese influence.” For China as a threat, the term “China threat” was chosen.

Third, although Google Trends also provides monthly datasets, this study utilises weekly data. The variables under investigation are inherently high-frequency and likely to fluctuate on a weekly basis. Aggregating these into monthly observations risks discarding meaningful variation and attenuating genuine relations. Moreover, the statistical model specification (see

Section 4.2.1 for details) includes twelve weekly lags, effectively capturing dynamics over a three-month horizon, rendering additional temporal aggregation unnecessary.

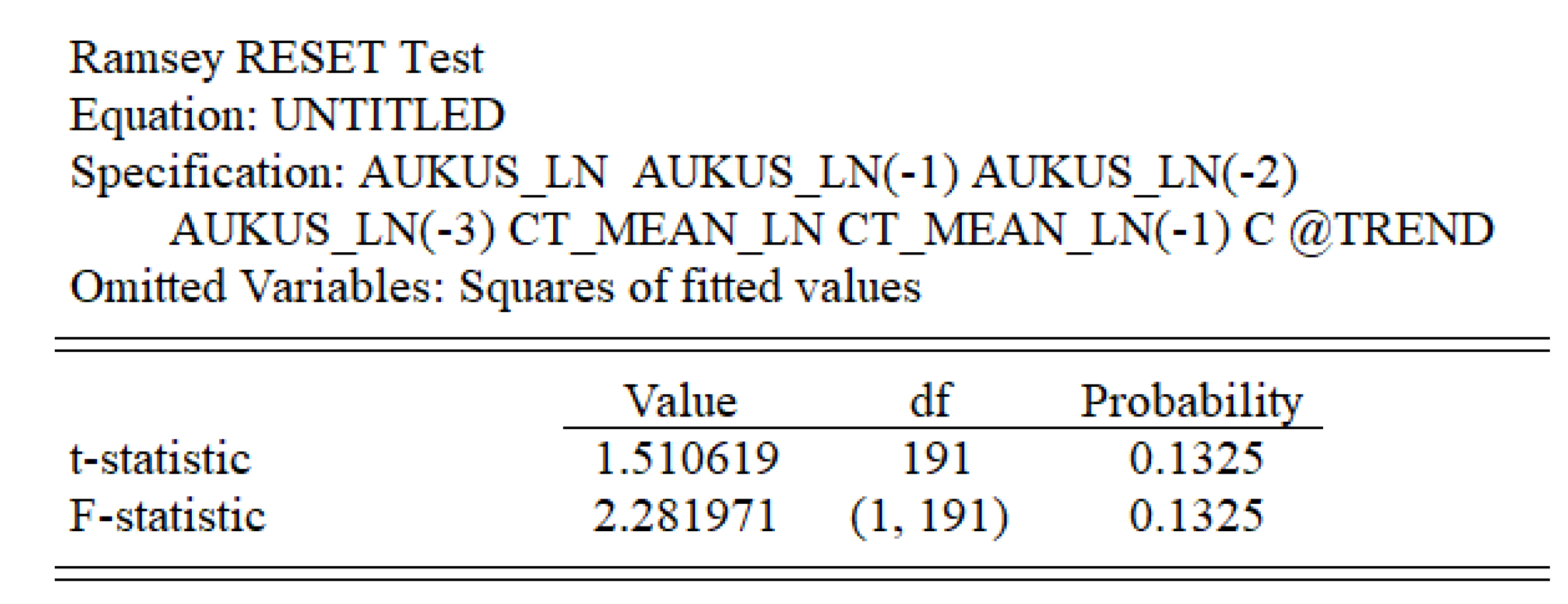

Fourth, in most cases, the mean of 12 or 20 samples is preferable, as it incorporates all data points and provides a better representation of overall search interest trends. The only exception is “China rise” in Australia, which is skewed and contains outliers. Using the mean as an independent variable in this case violates the linearity assumption, as indicated by the Ramsey RESET test (see Appendix 2). The median, being robust to extreme values, preserves the model’s linearity and passes the RESET test, making it a more reliable measure of central tendencies in public attention.

4.2.1. Australia

As discussed in the literature review, China may be the principal factor shaping Australia’s AUKUS policy. It has also been suggested that the policy may be influenced by Australia’s desire to preserve its “self” identity. However, the variable “Anglosphere” yields almost zero results in Australia. This does not necessarily imply that it is unimportant; rather, it may reflect an inverse relation with China threat.

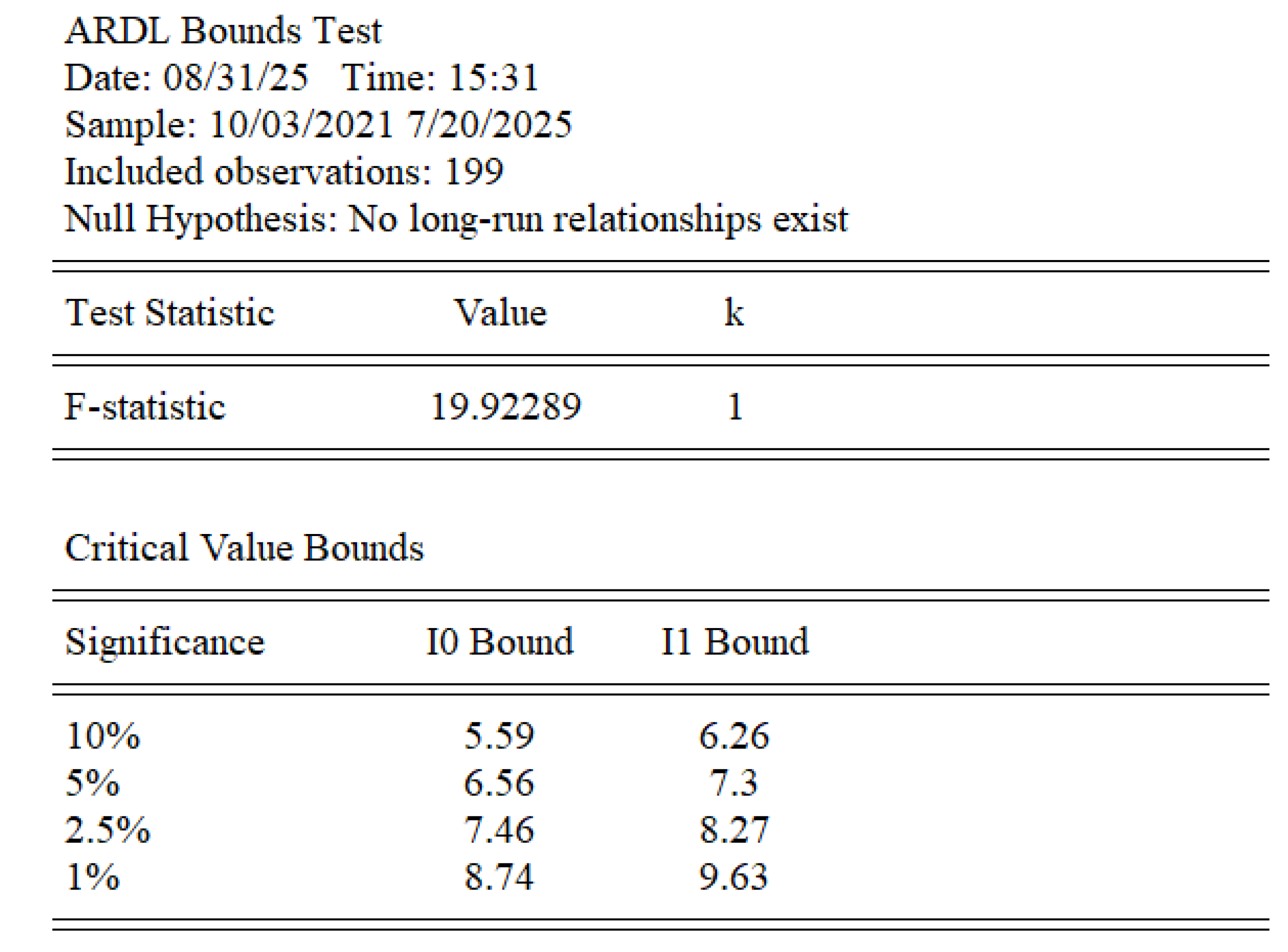

The datasets used are presented in Appendix 1. The statistical method employed is the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model, a regression technique used to analyse the relations between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables over time. ARDL incorporates lagged values of the dependent variable to capture past effects, and current and lagged values of the independent variables to model delayed impacts. It is particularly suitable for datasets containing a mix of stationary and non-stationary series, allowing the separation of short-run dynamics (with lags) from long-run equilibrium effects (without lags). In this study, only long-run relations are reported.

Table 1 presents the results.

AUKUS_AU and

China_Threat_AU are transformed using natural logarithms to mitigate issues with residual normality.

Various model fit tests (see Appendix 2) indicate that Model C performs well43. Models A and B also demonstrate satisfactory performance, with detailed model fit test results available upon request.

In the ARDL long-run estimates for Australia, the coefficient on China_Threat_AU is significant, while its constant term is not, indicating that AUKUS dynamics are almost entirely driven by perceptions of China as a threat. By contrast, for China Rise and China Influence, the coefficients are not significant, whereas the constant terms are, suggesting that support for AUKUS in Australia persists even in the absence of these factors, reflecting a historically embedded baseline concern. Notably, the prominence of China Threat aligns with Australia’s longstanding historical anxieties towards China, dating back to the “Yellow Peril” discourse, anti-Chinese movements, and the White Australia policy. These legacies have entrenched a persistent perception of China as a security threat in the public imagination, providing fertile ground for contemporary AUKUS narratives.

Since the Albanese government in May 2022 maintained broad support for AUKUS, there is no sharp policy shift that requires controlling. However, rhetorical tone or domestic framing may still be relevant. A dummy variable (post-May 2022 = 1, otherwise 0) was created. The results (available upon request) indicate that the coefficients are consistently insignificant, and the inclusion of this variable does not materially affect the performance of other variables.

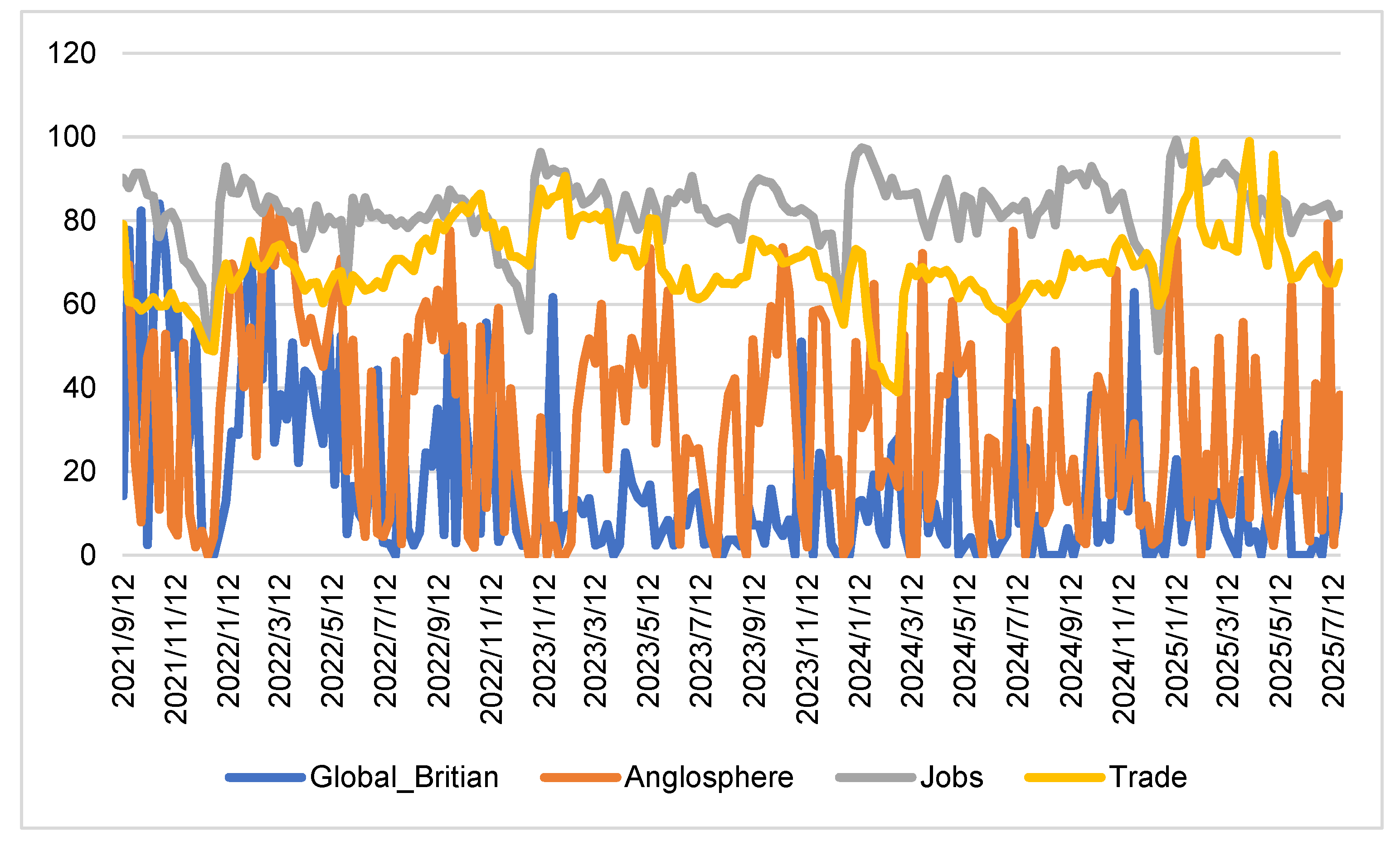

4.2.2. UK

As discussed in the literature review, multiple factors may have driven the AUKUS policy in the UK. Politically, it serves as a tool to counter China, captured by three variables: China Rise, China Influence, and China Threat. Diplomatically, AUKUS forms part of the UK’s Global Britain agenda, the post-Brexit foreign policy vision aimed at projecting the UK as an active global power. Culturally, it is intended to strengthen connections among Anglosphere countries. Economically, it is expected to generate commercial opportunities for the UK, captured by the variables trade and jobs. The datasets are presented in Appendix 3. To account for the potential effects of the government change from the Conservative Party to the Labour Party in July 2024, a dummy variable,

D_GovChg_UK, was created, equal to 1 after 5 July 2024 and 0 otherwise. The regression results are shown in

Table 2.

Various model fit tests (available upon request) indicate satisfactory performance. The regression results for the UK reveal a nuanced pattern in the factors driving public attention to AUKUS.

First, the framing of China produces divergent effects depending on the dimension emphasised. China_Rise_UK appears largely insignificant, indicating that perceptions of China’s growing economic and technological capabilities do not strongly influence public attention to AUKUS. By contrast, China_Influence_UK exhibits a positive and statistically significant effect, suggesting that the UK public responds to narratives emphasising China’s global sway. Interestingly, China_Threat_UK demonstrates a highly context-dependent impact: it is insignificant in models focusing on Trade but becomes strongly negative when paired with the Jobs variable. This suggests that portraying China explicitly as a threat can provoke a backlash among the UK public when domestic economic considerations are salient.

In the British context, where official discourse frames China as a “systemic competitor” while simultaneously emphasising trade, investment, and cooperation opportunities, the threat narrative lacks salience among the wider population. Ordinary citizens, geographically distant from China and with limited direct exposure to security risks, respond more to narratives of influence and interdependence—through everyday interactions with China, such as students, restaurants, consumer goods, or technology—than to securitised framings. As shown in the data (see Appendix 3), China_Threat_UK contains many zero values. Surges in interest regarding “China threat” were largely driven by two extreme events and lacked substantive connection to AUKUS. While surveys indicate high levels of distrust towards China (BFPG, 2025), this sentiment does not automatically translate into perceptions of imminent danger. Rather, it generates a tension: strong awareness of Chinese influence combined with limited personal experience of security risk. In this context, initiatives such as AUKUS function less as responses to public demand for protection against an immediate threat.

The Australian and UK cases demonstrate how identical events can generate divergent public perceptions and narrative dynamics. For instance, during the week of 23 February 2025, China conducted military exercises near Australia and New Zealand. Australian media framed these actions simultaneously as a threat and as exerting influence (AFR, 2025), resulting in elevated Google Trends scores for both China Threat and China Influence. By contrast, UK media predominantly portrayed the event as an example of Chinese influence (Graham-McLay, 2025; Newey, 2025), with public concern regarding China Threat remaining negligible.

Economic framing also exerts a decisive influence. The Jobs variable is consistently positive and highly significant, suggesting that the UK public associates AUKUS with potential domestic economic benefits. By contrast, Trade appears statistically insignificant, indicating that trade-related narratives resonate less strongly in the UK context. The significance of the Jobs variable, compared with the insignificance of Trade, can be explained at three levels. First, official government documents consistently emphasise job creation over abstract trade metrics. Second, media narratives reinforce this focus, frequently highlighting employment benefits and research or collaboration opportunities under frameworks such as Pillar II. Third, at the societal level, citizens respond more strongly to immediate, tangible outcomes—such as employment—than to distant, macro-level indicators like trade volumes.

The variable Global_Britain_UK captures a broader national identity narrative. Its significance in four of the six models highlights the salience of post-Brexit identity politics, though its inconsistency suggests that this narrative resonates only under specific conditions. Notably, its influence diminishes when job-related factors dominate public attention. This statistical interaction—where the significance of Global Britain declines when modelled alongside Jobs—is consistent with the substitutability of these two narratives, with economic priorities prevailing in the public mindset.

Another key finding emerges from examining the interaction between the government-change dummy variable (D_GovChg_UK) and economic indicators. When the dummy variable representing the transition to the Starmer government is included alongside Jobs, its significance disappears, suggesting that public concern over employment and its relation to AUKUS remained stable across administrations. In contrast, when Trade serves as the economic indicator, the dummy variable assumes a negative coefficient with marginal significance, implying that under the Starmer government, public attention to AUKUS may have slightly declined in relation to trade considerations. This contrast highlights that economic dimensions are not uniform, and different indicators (Jobs versus Trade) interact differently with political transitions, producing subtle shifts in public opinion towards AUKUS.

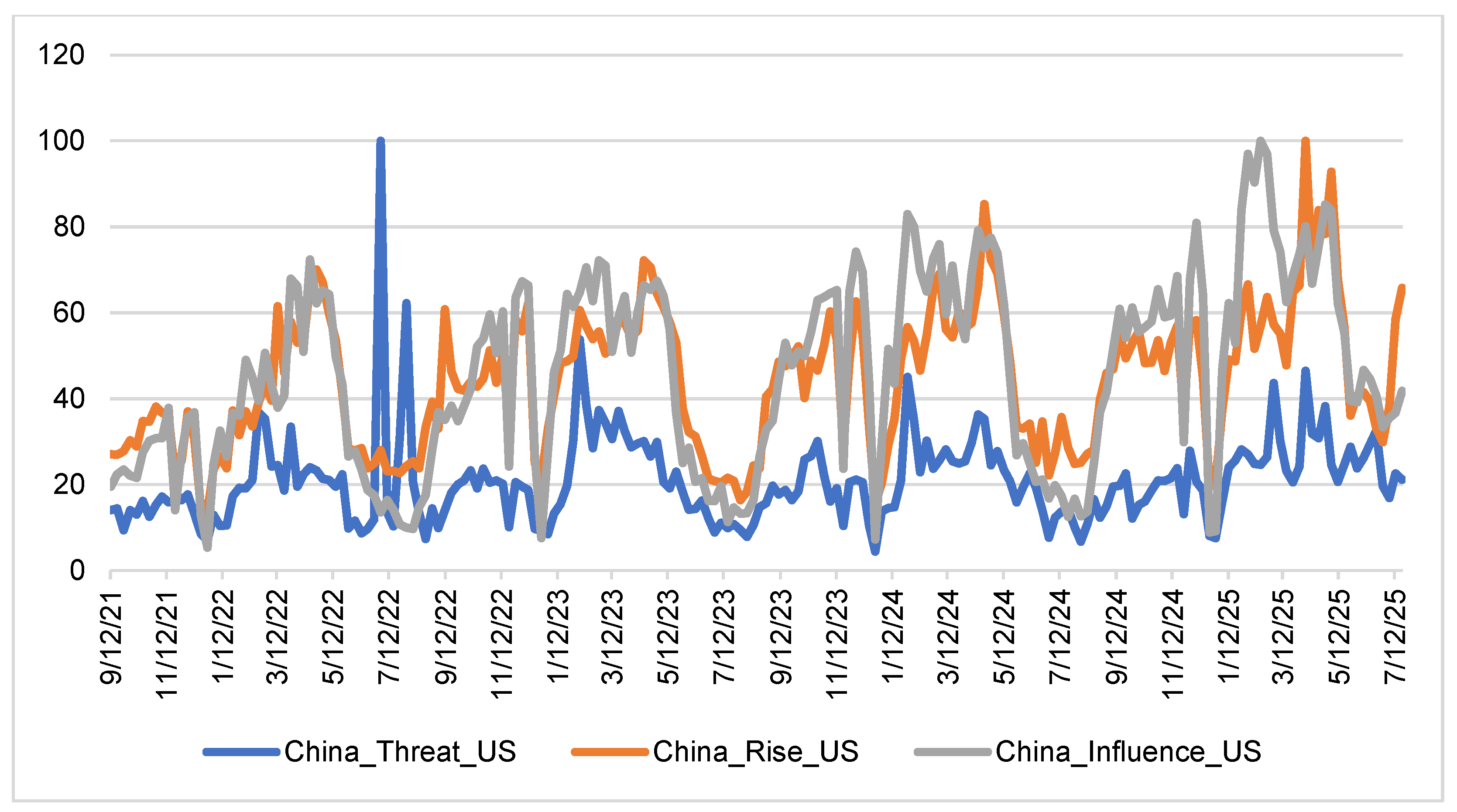

4.2.3. US

As discussed in the literature review, China appears to be the primary driver of AUKUS in the US. The datasets used are provided in Appendix 4. The regression results are presented in

Table 3.

The analysis indicates that US public attention to AUKUS is most strongly influenced by perceptions of China as a security threat, with the coefficient significant at the 0.9% level. In contrast, variables representing China’s rise and China’s influence are only marginally significant, at 8.8% and 9.9% respectively. These results suggest that US public interest in AUKUS is primarily driven by threat perceptions rather than by awareness of China’s growing capabilities or broader influence. In other words, abstract concerns about China’s power or global sway are less salient to the public than the perception of direct security risks. This finding underscores the centrality of threat framing in shaping public attention and indicates that US domestic engagement with AUKUS is more reactive to perceived dangers than to China’s rise per se.

When a dummy variable D_GovChng_US, equalling 1 after the week of 19 January 2025 and 0 elsewhere, is added to the models, its coefficients are consistently insignificant. Changes to other variables are minimal, except for China Influence, whose significance level rises slightly above 10 per cent. Given that it is only marginally significant in Model B, further analysis of this minor difference is likely unnecessary.

Taken together, the positive and highly significant trend coefficients across all models in all three countries indicate that public attention to AUKUS is increasing over time, irrespective of region, government changes, or narrative framing. Comparative analysis across Australia, the US, and the UK reveals distinct public drivers behind the AUKUS narrative. In Australia, China Threat emerges as the dominant and historically embedded factor, rooted in a century-long apprehension towards China, making it the key explanatory variable. In the US, China Threat and, to a lesser extent, China Rise and China Influence are relevant, reflecting a security-focused yet multifaceted perception of China’s role in shaping AUKUS. The UK diverges sharply: threat-based narratives are weak, while China Influence, Global Britain, and Jobs consistently emerge as significant, indicating that British framing of AUKUS is less about existential security threats and more about influence-balancing, national identity projection, and economic opportunity.

In sum, these findings demonstrate that AUKUS is not perceived as a monolithic security alliance by the public, but rather as a narrative shaped by distinct historical legacies, geopolitical roles, and domestic concerns across the three countries.

4.3. Interconnections

This section analyses the interconnections of AUKUS narratives across the three countries. Data samples are divided into sub-samples according to government change dates. In Australia, two sub-samples are created around 23 May 2022 to control for the transition from a Coalition government to a Labor government. In the UK, two sub-samples are created around 5 July 2024 to account for the shift from Conservative to Labor government. In the US, two dates are considered: 12 March 2024, when Donald Trump became the Republican presumptive presidential nominee, and 20 January 2025, marking the start of the Trump-Vance administration. For the US government change break, three data items from December are removed to mitigate uncertainties during the transition period..

Granger causality tests are employed to assess whether past values of one variable help predict the current value of another. If the inclusion of lagged values of variable X improves forecasts of variable Y, then X is said to ‘Granger-cause’ Y. Importantly, this indicates predictive power rather than true causal relations. All sub-samples are stationary (test results available upon request).

Table 4 presents the results, with up to five lags included.

Regarding the relations between AUKUS search trends in Australia and the UK,

Table 4 indicates that both the direction and significance of predictive influence are contingent on political events. Around the Australian government change on 23 May 2022, all tests are insignificant, suggesting that the transition did not materially affect attention to AUKUS in either country. By contrast, around the UK government change on 5 July 2024, the dynamics shift: prior to the change,

AUKUS_AU predicts

AUKUS_UK, whereas following the change,

AUKUS_UK robustly Granger-causes

AUKUS_AU, with no reverse effect. This pattern implies that, after the UK government transition, the UK emerged as a more salient reference point for AUKUS discourse in Australia.

Regarding the relations between AUKUS search trends in Australia and the US, prior to 23 May 2022, the bidirectional causality between AUKUS_AU and AUKUS_US indicates a strong interplay, likely driven by the Coalition’s assertive rhetoric on China and the US’ initial leadership in AUKUS. Public interest in Australia was closely aligned with US policy and media narratives. After 23 May 2022, the pattern shifts to one-way causality (AUKUS_AU → AUKUS_US), suggesting that the Australian public began to shape the AUKUS narrative, with the US responding rather than leading. The reduction in China-focused rhetoric may have partially redirected public attention away from the US’ geopolitical stance, weakening its predictive influence. The lack of significance during major US political milestones further suggests that US domestic politics exert minimal immediate effect on the interrelation of AUKUS_AU and AUKUS_US as reflected in public interest.

Regarding the relations between AUKUS_UK and AUKUS_US, the results consistently indicate that AUKUS_UK significantly Granger-causes AUKUS_US, with no reciprocal effect, irrespective of data splits. It should be noted that Granger causality reflects whose public or political discourse shifts first, not substantive leadership. This pattern suggests that UK governments (both Conservative and Labour) discuss AUKUS more frequently and frame the narrative in ways subsequently adopted by US media and policymakers. Given the special relationship between the UK and the US, the UK’s domestic politics require a continual demonstration of the alliance’s value, prompting more active communication of AUKUS. By contrast, the US, for whom AUKUS constitutes one element of a broader global security posture, communicates more intermittently. The statistical results thus position the UK as a leading indicator of US public and political discourse on AUKUS.

In short, while AUKUS is formally structured as “Australia provides funding, the US supplies technology, with the UK appearing a minor supporting actor,” the narrative centre in fact rests with the UK. Through its influence over domestic media, the British government has shaped public discourse, linking China-related concerns with the Global Britain agenda and domestic job creation. This narrative not only frames AUKUS domestically but also projects influence onto Australia and the US. Thus, AUKUS functions as much as a military-industrial arrangement as it does a narrative project centred on the UK, reinforcing Britain’s diplomatic visibility and strategic legitimacy under the Global Britain framework.

5. Policy Implications

In democracies, elected officials often consider public opinion when shaping policies. Prominent or contested issues can drive initiatives, as leaders seek popularity and re-election. Politicians may adjust positions or actions to align with voters’ preferences, making public sentiment a key influence on government priorities and decision-making.

Regarding foreign policy specifically, in Australia, while elite consensus dominates, a surge in public awareness and concern has emerged recently, particularly on issues like war and security threats (Chubb and McAllister, 2020). In the UK, public opinion has had a limited role in shaping foreign and defence policy. The elite consensus, particularly within the government and political establishment, has dominated foreign policy-making (Clements, 2018; Gaston, 2025). In the US context, Page and Shapiro (1983) showed that public opinion frequently drives foreign policy decisions rather than simply reacting to them. Eichenberg (2016) calls this a “landmark study,” emphasizing that shifts in public sentiment often precede and shape policy, making opinion a powerful determinant.

The implications of public opinion for AUKUS vary significantly across these three countries. In Australia, while foreign policy remains primarily the prerogative of the executive, public opinion—particularly on issues of war and military involvement, such as AUKUS—carries weight insofar. In the UK, foreign policy remains more insulated from public pressures, with decision-making largely elite-driven and less exposed to shifts in opinion. In the US, by contrast, public attitudes can exert a direct influence on foreign policy through presidential and congressional accountability, meaning that widespread opposition or support may shape the sustainability of AUKUS commitments. Consequently, the durability of AUKUS across these states is conditioned by the varying degrees to which public opinion interacts with institutional structures and elite decision-making.

5.1. On Salient Issues

As discussed in part 3.1, the publics in Australia, the UK, and the US exhibit distinct concerns regarding AUKUS, which translate into different policy implications. In Australia, attention centers on the costs and uncertainties of the partnership, suggesting that policymakers should emphasize economic benefits, risk management, and the long-term strategic rationale. In the UK, concern is directed toward foreign policy and business opportunities, indicating that communication should highlight trade, investment, and international influence - or may already have done so. In the US, attention is primarily directed toward geopolitical and strategic issues, reinforcing the need to frame AUKUS in terms of regional security, alliance cohesion, and deterrence.

5.2. On Driving Factors

5.2.1. Australia

In Australia, the AUKUS deal was supported by both the Coalition and Labor governments (McDougall, 2023). As Chubb and McAllister (2020) note, Australia’s foreign policy is largely bipartisan, though rhetorical emphases differ. Regarding China, former Prime Minister Tony Abbott famously described policy as driven by “fear and greed” (Garnaut, 2015): greed reflecting economic opportunities through trade and investment, and fear reflecting deep-rooted anxieties about China’s threat. Alan Renouf’s The Frightened Country (1979) argued that such anxieties have shaped Australian policy since federation.

Regarding public opinion, survey evidence44 shows a marked shift in Australians’ perception of China as a security threat in recent years. Prior to 2020, this perception remained relatively moderate; however, it has risen substantially since then. Complementing these findings, Google Trends data45 reveal that from 2017 onward, the Australian public increasingly associated China with war-related activities and conflict risks. From early 2020 to 2023, in particular, concerns about the prospect of a potential war with China intensified sharply.

The findings of this study suggest that the perceived “China threat” is the primary factor shaping the AUKUS narrative in Australia. This conclusion aligns with both public perceptions and policy discourse, highlighting a clear consistency between public opinion and foreign policy.

5.2.2. UK

In its 2021 Integrated Review of foreign policy, the UK defined China as a “systemic competitor,” stating it would “continue to pursue a positive trade and investment relationship with China, while ensuring our national security and values are protected” (HM Government, 2021). Cornish (2021) characterized this as a mature and balanced approach to relations with China. The 2023 update (HM Government, 2023) emphasized strengthening national security protections against Chinese threats, deepening cooperation with core allies and partners, maintaining direct engagement with China, and enhancing China-related capabilities. Following the government change in July 2024, Prime Minister Starmer became the first British leader in six years to meet Xi Jinping46, declaring a desire for “a serious and pragmatic relationship with China. 47” The UK’s National Security Strategy 202548 reflects this stance, acknowledging China’s global influence, pursuing economic engagement, and reinforcing national security capacities to address related challenges.

As shown in part 3.2.2, UK public opinion on AUKUS is shaped primarily by concerns over jobs, Britain’s global role, and perceptions of China’s influence, rather than by perceptions of China as a direct threat. This aligns closely with the UK government’s official policy framing, which portrays China as a “systemic competitor” rather than an existential adversary, while emphasizing economic benefits, job creation, and Britain’s global presence. The broader implication is that UK public opinion largely mirrors existing policy orientations rather than driving new ones, in contrast to the US, where public attitudes more directly influence policy trajectories. Consequently, British public opinion tends to fluctuate within the boundaries set by elite consensus and government narratives. At the same time, episodic events can produce short-term shifts in salience, suggesting that the relationship is one of policy-led framing with limited public responsiveness, rather than a complete absence of reciprocal influence.

5.2.2. US

During the initial period of the Trump administration (January 2017 to January 2021), China was defined as a competitor and a key player in great power competition49. For decades, U.S. policy assumed that fostering China’s rise and integrating it into the post-war international order would encourage liberalization. In practice, however, China followed a markedly different path. In response, the US began implementing a decoupling strategy in 2018, targeting trade, investment, finance, people, and technology50. A trade agreement was reached in January 2020, but the targets were not fully met. By mid-2020, senior Trump administration officials delivered a series of speeches outlining a more confrontational U.S. policy toward China, signaling a significant shift toward an adversarial approach. Specifically: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo advocated for a more assertive stance toward “Frankenstein” China and urged Chinese citizens to help “change the behaviour” of their government51; FBI Director Christopher Wray labeled China as the greatest long-term threat to U.S. economic and national security52; National Security Advisor Robert C. O’Brien announced new measures to counter China’s growing threat53; and Attorney General William P. Barr stated that the CCP threatened the U.S. way of life, including its very lives and livelihoods54.

During the Biden administration (January 2021 – January 2025), China was defined as “the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to advance that objective. 55” Supporting allies’ capabilities, especially in the Indo-Pacific, against China’s pressure was a key strategic goal. From this perspective, AUKUS aligns with the administration’s stated strategy. Other policies toward China, such as trade, remained largely unchanged, while technology export controls were strengthened (Borg, 2024). The perception of China as a threat, or its “rise,” enjoyed bipartisan consensus. During the Trump administration’s second term (as of August 2025), in addition to labeling China as the origin of COVID-19, trade decoupling efforts were further intensified.

Public opinion reflects strong concern over China. For example, Gallup polls conducted from 2013 to 202456 show that consistently around 90 percent (or higher) of the U.S. public viewed China’s economic and/or military power as a threat to the U.S. The share of Americans who considered China the U.S.’s greatest enemy rose sharply from 22 percent in 2020 to 45 percent in 2021, 49 percent in 2022, 50 percent in 2023, before declining to 41 percent in 2024.

U.S. foreign policy toward China closely aligns with public opinion, as both survey and Google Trends data show sustained concern over the China threat. Public attention to AUKUS, for instance, is strongly driven by perceived security risks, indicating that threat framing outweighs abstract awareness of China’s rise or influence. Both the Trump and Biden administrations adopted assertive strategies—including trade decoupling, technology controls, and, in Biden’s case, alliance-building initiatives like AUKUS—that reflect these public concerns.

5.3. On Interconnections

In both Australia and the UK, foreign policy is primarily determined by political elites, implying that policy decisions influence public opinion more than the reverse. In the US, public opinion has a relatively greater capacity to shape policy. This suggests that the Australian government may have deliberately adjusted its rhetoric toward China, producing a policy orientation less responsive to U.S. domestic politics and more attentive to the UK. At the policy level, Australia may have actively sought to minimize the impact of U.S. domestic developments, a pattern reflected in public opinion. In the UK, by contrast, the longstanding “special relations” with the US is evident at both policy and public levels, with UK policy consistently shaping U.S. public attention and discourse.

6. Concluding Remarks

AUKUS, established in September 2021, has drawn significant attention from scholars and policymakers. Using weekly Google Trends data from 12 September 2021 to 20 July 2025, this study examines public opinion and its relation to national policies in Australia, the UK, and the US. Through a novel methodology and comprehensive analysis, it provides a rigorous assessment of public sentiment and policy interactions, offering insights that go beyond previous research.

The findings reveal three main aspects of public opinion. First, the focus of attention varies across the three countries: Australians are primarily concerned with costs and uncertainties, the British with diplomatic strategy and economic opportunities, and Americans with broader strategic considerations. Second, the driving factors behind AUKUS perceptions differ: in Australia, the China Threat is the sole significant determinant; in the UK, China Influence, employment concerns, and post-Brexit identity politics collectively drive public attention; in the US, China Threat dominates, while China Rise and China Influence are only marginally significant. Third, interconnections indicate that, since the UK government change in July 2024, Australian public responsiveness to UK AUKUS actions has increased, whereas responsiveness to the US has decreased. Meanwhile, the UK consistently shapes U.S. public perception regardless of American domestic politics. Overall, the narrative core of AUKUS rests in the UK.

Building on these public opinion findings, this study further examines policy implications. Across Australia, the UK, and the US, public sentiment and government policy are largely aligned, reflecting the accountability mechanisms inherent in democratic systems. Following the Australian Labor government’s update in May 2022, Australia appears more responsive to UK perspectives than to U.S. developments, potentially reducing the impact of domestic political shifts in the US—an important consideration for policymakers. While consistently shaping U.S. public discourse, the UK may play a leading role in the AUKUS policy agenda.

Finally, the use of high-frequency time-series data and time-series modeling offers a novel perspective that complements traditional survey-based studies. While cautious in its claims, this methodology opens promising avenues for future research, enabling a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between public sentiment and government policy across a wide range of issues.

Conflicts of Interest

none.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT and Grok AI to assist with writing refinement and certain analyses. All contents were subsequently reviewed and edited by the author, who takes full responsibility for the final publication.

Appendix 1. Datasets: Australia

Median value of “China Rise” and mean values for “China Influence” and “China Threat;” Number of samples: 20; weekly data spanning 12 September 2021 – 20 July 2025

For China_Rise_AU, the largest peak occurred in the week of 5 March 2023. The surge in search interest was primarily driven by a “red alert” series published on 7 March 2023 by Australia’s two major newspapers, The Sydney Morning Herald57 and The Age58, warning that Australia could face the threat of war with China within three years and that Australians are unprepared. This series sparked contentious discussions about a potential military conflict with China. The second-largest peak occurred in the week of 14 November 2021, mainly driven by former Prime Minister Paul Keating’s speech at the National Press Club on China’s rise and subsequent responses from various parties.

For China_Influence_AU, the largest peak of search interest occurred in the week of 19 May 2024. This surge was primarily driven by reports from Australia’s flagship investigative program Four Corners59, which revealed China’s overseas operations and influencing activities through the account of a former spy from China’s secret police. The second-largest peak occurred in the week of 8 June 2025, when U.S. President Trump was compelled to make a deal with China to lift rare earth export controls60, highlighting China’s influence.

For China_Threat_AU, the largest peak occurred in the week of 5 March 2023. Similar to China_Rise_AU, this surge was driven by the “Red Alert” series, which argued that Australia faces the threat of war with China within three years.

Appendix 2. Model Fit Tests

| Variable |

Centered VIF |

| AUKUS_AU(-1) |

3.043 |

| AUKUS_AU(-2) |

3.225 |

| AUKUS_AU(-3) |

2.331 |

| China_Threat_AU |

1.353 |

| China_Threat_AU(-1) |

1.815 |

| C |

NA |

| @TREND |

2.380 |

- B.

ARDL Bounds Test

- C.

Correlogram – Q-Statistics

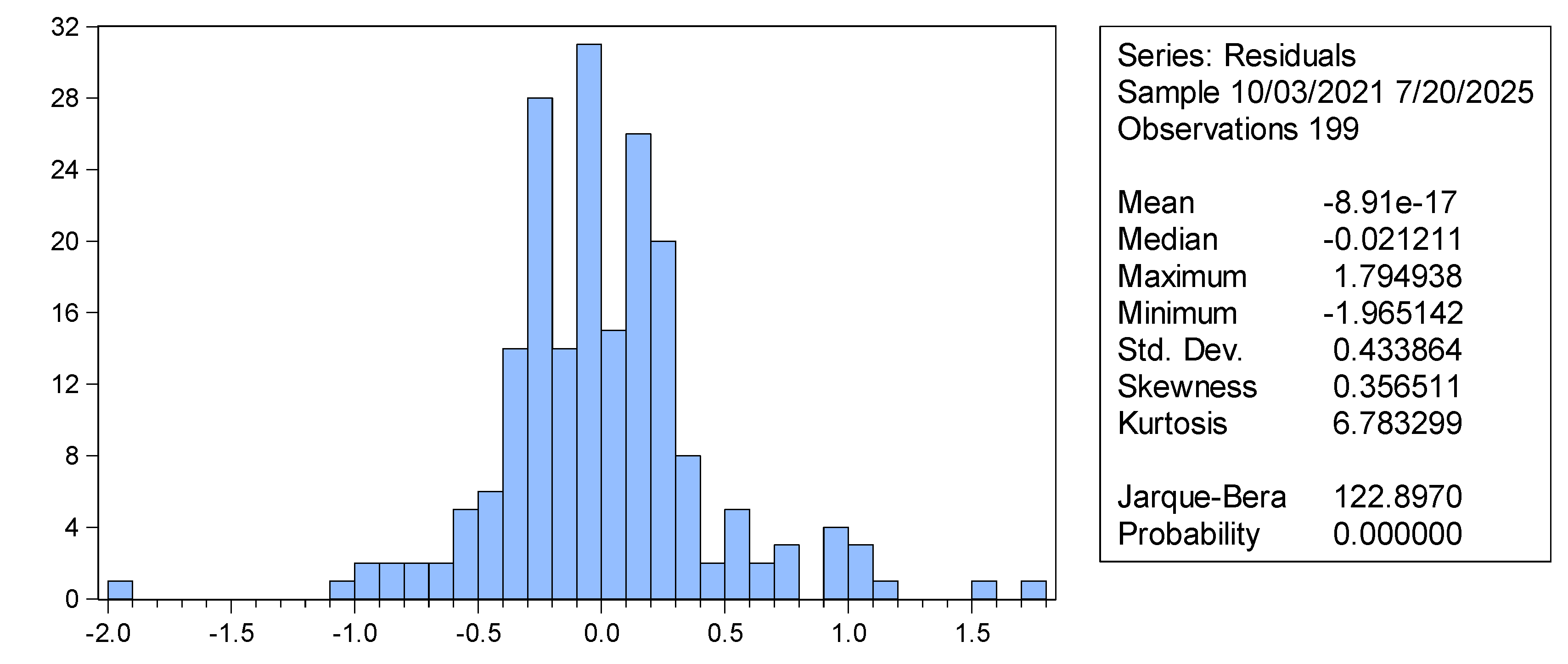

D. Histogram – Normality Test

- D.

Ramset RESET Test

The ARDL bounds test confirms the existence of long-run relations. Coefficient diagnostics show that variance inflation factors for key variables are below 5, indicating negligible multicollinearity. Residual tests, including correlograms of standardized and squared residuals (available on request), reveal no serial correlation. A Kurtosis value over 3 indicates leptokurtic residuals with heavier tails than a normal distribution, prompting the use of robust standard errors. The Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test (available on request) detects heteroskedasticity, suggesting non-constant error variance and justifying robust estimators for reliable inference. The Ramsey RESET test shows no evidence of non-linear functional forms.

Appendix 3. Datasets: UK

Mean values of 20 samples: weekly data spanning 12 September 2021 – 20 July 2025

The largest peak in China_Rise_UK searches occurred in the week of 13 March 2022. This surge was driven by reports that Russia sought military and economic support from China for its war in Ukraine61. Historically the dominant partner, Russia’s apparent reliance on China may have prompted the UK public to perceive China’s rising power.

The largest peak in China_Influence_UK searches occurred in the week of 23 February 2025. The surge was primarily driven by two events: discussions of Chinese influence amid foreign aid cuts in the US and UK62, and China’s military demonstration near Australia and New Zealand63.

Compared with China_Rise_UK and China_Influence_UK, China_Threat_UK contains more zero data points. Search interest was primarily driven by two extreme events: the week of 3 July 2022 (the largest peak) and the week of 9 October 2022 (the second-largest peak). The largest peak was prompted by a joint MI5–FBI statement warning that China would pose the greatest security threat to the West over the next decade64. The second peak was driven by a rare protest calling for the overthrow of CCP rule65.

For Global_Britain and Anglosphere, the mean values of 20 weekly samples are used. For Trade and Jobs, the mean values of 12 weekly samples are used. Data cover the period from 12 September 2021 to 20 July 2025.

For Global_Britain, the largest peak in search interest occurred during the week of 24 October 2021. This surge was driven by the Johnson Conservative government’s Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021, which emphasized the government’s vision of Global Britain66.

For Anglosphere, the largest peak in search interest occurred during the week of 27 February 2022. This surge was driven by Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and the coordinated responses from Anglosphere countries.

For Jobs, peaks in search interest typically occurred in early January of 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025, while troughs appeared in late December each year. January historically sees heightened job-seeking activity in the UK, as individuals reassess career paths following the festive season.

For Trade, the largest peaks in search interest occurred during the weeks of 2 February 2025 and 6 April 2025, primarily driven by U.S. President Trump’s announcements of massive tariffs on multiple countries67.

Appendix 4. Datasets: US

Mean values of 12 samples; weekly data covering 12 September 2021 – 20 July 2025

For China_Rise_US, the largest peak occurred in the week of 6 April 2025. This surge followed the U.S. announcement on 2 April 2025 of broad import tariffs targeting nearly all countries. China’s unique resistance68, employing a tit-for-tat strategy, led observers—including Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates—to interpret it as evidence of U.S. decline and China’s rise, signaling a rare breakdown in the global economic and political order69.

For China_Influence_US, the largest peak occurred between 2 February and 23 February 2025. During this period, the U.S. abruptly shut down the United States Agency for International Development and blocked Treasury disbursements from the National Endowment for Democracy. Analysts suggested these moves could expand China’s influence70. Additional commentary highlighted China’s role in the Panama Canal71.

For China_Threat_US, the largest peak occurred in the week of 3 July 2022. The surge was mainly driven by news coverage of joint statements from the FBI and MI5 declaring China as the “biggest long-term threat” to the US72.

References

- 7news.com.au. 2025. Huge blow for Australia’s nuclear submarine plans as US government reviews AUKUS deal. 12 June. https://7news.com.au/news/huge-blow-for-australias-nuclear-submarine-plans-as-us-government-reviews-aukus-deal-c-19006333.

- 9news.com.au. 2025. 'Not everyone knows acronyms': Australian politicians shrug off Trump blunder on AUKUS. https://www.9news.com.au/world/donald-trump-stumbles-when-asked-about-aukus-defence-deal/6a602864-b990-4d37-95a4-530e31bd96e8.

- Acton, James M. 2021. Why the AUKUS Submarine Deal Is Bad for Nonproliferation—And What to Do About It. 21 September. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2021/09/why-the-aukus-submarine-deal-is-bad-for-nonproliferationand-what-to-do-about-it?lang=en.

- AFR. 2025. Chinese warships a wake-up call to step up our maritime security. 28 February. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/chinese-warships-a-wake-up-call-to-step-up-our-maritime-security-20250228-p5lfxk.

- Australian Institute. 2025. AUKUS review a golden opportunity to escape a disastrous deal. 12 June. https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/aukus-review-a-golden-opportunity-to-escape-a-disastrous-deal/.

- Barnes, Jamal, and Samuel M. Makinda. "Testing the limits of international society? Trust, AUKUS and Indo-Pacific security." International Affairs 98.4 (2022): 1307-1325. [CrossRef]

- BFPG. 2025. UK Public Opinion on Foreign Policy and Global Affairs Annual Survey – 2025. https://bfpg.co.uk/2025/07/2025-annual-survey-of-uk-public-opinion-on-foreign-policy/.

- Briançon, Pierre. 2021. U.S., U.K. Defense Groups Will Benefit From Australian Submarine Deal. 21 September. Barrons. https://www.barrons.com/articles/u-s-u-k-defense-stocks-will-benefit-from-australian-submarine-deal-51631802997.

- Bisley, Nick. "The Quad, AUKUS and Australian Security Minilateralism: China’s Rise and New Approaches to Security Cooperation." Journal of Contemporary China (2024): 1-13.

- Carvin, Stephanie, and Thomas Juneau. "Why AUKUS and not CAUKUS? It's a Potluck, not a Party." International Journal 78.3 (2023): 359-374.

- Caverley, Jonathan D. "AUKUS: When naval procurement sets grand strategy." International Journal 78.3 (2023): 327-334.

- Chan, Lai-Ha, and Maria Rost Rublee. "The promise of AUKUS: implications of its minilateral institutional form." Australian Journal of International Affairs 78.6 (2024): 848-868. [CrossRef]

- Childs, Nick. "The AUKUS anvil: Promise and peril." Survival: October–November 2023. Routledge, 2023. 7-23. [CrossRef]

- Chubb, Danielle, and Ian McAllister. Australian public opinion, defence and foreign policy: Attitudes and trends since 1945. Springer Nature, 2020.

- Clayton, Kate, and Katherine Newman. "Settler colonial strategic culture: Australia, AUKUS, and the anglosphere." Australian Journal of Politics & History 69.3 (2023): 503-521. [CrossRef]

- Clements, Ben. British Public Opinion on Foreign and Defence Policy: 1945-2017. Routledge, 2018.

- Cornish, Paul. "AUKUS and “Global Britain”: Sub-Standard Strategy?." https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul-Cornish/publication/355985176_AUKUS_and_'Global_Britain'_Sub-standard_Strategy/links/6189162961f0987720706277/AUKUS-and-Global-Britain-Sub-standard-Strategy.pdf (2021).

- Cox, Lloyd, Danny Cooper, and Brendon O’Connor. "The AUKUS umbrella: Australia-US relations and strategic culture in the shadow of China's rise." International Journal 78.3 (2023): 307-326. [CrossRef]

- as, Debak. 2021. Australia will get nuclear-powered submarines. Some see a proliferation threat. 24 September. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/09/24/australia-will-get-nuclear-powered-submarines-some-see-proliferation-threat/.

- Dearing, James W., and Everett M. Rogers. Agenda-Setting. Communication Concepts 6. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1996. [CrossRef]

- Eichenberg, Richard C. "Public opinion on foreign policy issues." Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Garnaut, John. 2015. Fear and greed' drive Australia's China policy, Tony Abbott tells Angela Merkel. 16 April. Syndey Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/fear-and-greed-drive-australias-china-policy-tony-abbott-tells-angela-merkel-20150416-1mmdty.html.

- Gaston, Sophia. 2025. British public opinion on foreign policy: President Trump, Ukraine, China, Defence spending and AUKUS. March. https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2025-03/British%20public%20opinion%20on%20foreign%20policy.pdf?VersionId=yDoZndIq7Hl0QxRTJX.tCR.

- George Mulgan, A. George Mulgan, A., 2024. "Can Japan contribute to AUKUS?". AJRC Working Paper No. 4, May 2024. Australia-Japan Research Centre, Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstreams/91109283-2c6c-4160-82c4-db912bbcdb1a/download.

- Graham-McLay, Charlotte. 2025. Why Chinese warships have got these Western countries so rattled. The Independent. 24 February. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/australasia/chinese-warships-australia-new-zealand-b2703462.html.

- Greene, Andrew. 2023. AUKUS nuclear submarine deal to create tens of thousands of jobs, government says. 13 March. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-03-13/aukus-submarine-deal-to-support-20000-jobs-next-30-years/102087324.

- Greenwalt, William, and Tom Corben. Breaking the barriers: reforming US export controls to realise the potential of AUKUS. United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, 2023. https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Breaking-the-barriers-Reforming-US-export-controls-to-realise-the-potential-of-AUKUS.pdf.

- Groch, Sherryn. 2023. What is AUKUS and what are we getting in Australia’s biggest ever defence spend? Syndey Morning Herald. 14 March. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/what-is-aukus-and-what-are-we-getting-in-australia-s-biggest-ever-defence-spend-20230310-p5cr2j.html.

- Haugevik, Kristin, and Øyvind Svendsen. "On safer ground? The emergence and evolution of ‘Global Britain’." International affairs 99.6 (2023): 2387-2404.

- Harris, Rob. 2025. Asked about AUKUS, Trump replies: ‘What does that mean?’ 28 Febuary, Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/world/north-america/asked-about-aukus-trump-replies-what-does-that-mean-20250228-p5lfua.html.

- Hemphill, Tamara. 2021. The AUKUS Submarine Agreement: Ally and Partner Expectations. 23 September. https://www.cna.org/our-media/indepth/2021/09/aukus-submarine-agreement.

- HM Government. 2021. Global Britain in a competitive age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. March. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60644e4bd3bf7f0c91eababd/Global_Britain_in_a_Competitive_Age-_the_Integrated_Review_of_Security__Defence__Development_and_Foreign_Policy.pdf.

- HM Government. 2023. Integrated Review Refresh 2023: Responding to a more contested and volatile world. March. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/641d72f45155a2000c6ad5d5/11857435_NS_IR_Refresh_2023_Supply_AllPages_Revision_7_WEB_PDF.pdf.

- Holland, Jack, and Eglantine Staunton. "‘BrOthers in Arms’: France, the Anglosphere and AUKUS." International affairs 100.2 (2024): 712-729.

- Howe, Tom. 2023. AUKUS: more than submarines. 15 March. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/aukus-more-thansubmarines/.

- Hughes, David. 2023. Aukus: US, UK and Australia sign landmark nuclear submarine deal. 14 March. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/aukus-submarine-nuclear-china-ssn-b2300256.

- Keiger, John. 2021. The real reason France was excluded from Auku. 18 September. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-real-reason-france-was-excluded-from-aukus/.

- Kurt, Selim, Göktürk Tüysüzoğlu, and Cenk Özgen. "The weakening hegemon's quest for an alliance in the Indo-Pacific: AUKUS." Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 18.3 (2022): 230-249. [CrossRef]

- Koga, Kei. "Tactical hedging as coalition-building signal: The evolution of Quad and AUKUS in the Indo-Pacific." The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 27.1 (2025): 109-134.

- Kumar, Suneel. "Shifting balance of power and the formation of AUKUS in the Indo-Pacific region." Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 16.4 (2024): 456-476. [CrossRef]

- Kupchan, Charles A. 2021. Europe’s Response to the U.S.-UK-Australia Submarine Deal: What to Know. 22 September. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/europes-response-us-uk-australia-submarine-deal-what-know.

- Markowski, Stefan, Robert Wylie, and Satish Chand. "The AUKUS agreement: a new form of the plurilateral defence alliance? A view from downunder." Defense & Security Analysis 40.3 (2024): 430-449. [CrossRef]

- McDougall, Derek. "AUKUS: a Commonwealth perspective." The Round Table 112.6 (2023): 567-581. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00358533.2023.2286841.

- McKenzie, Simon, and Eve Massingham. "AUKUS: The Regulation of the Ocean and the Legal Dangers of Working Together", Ocean Yearbook Online 37, 1 (2023): 136-170. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, Josh. 2023. Sub-standard: AUKUS plan means more risks for Australia. 14 March. https://www.acf.org.au/news/substandard-aukus-plan-means-more-risks-for-australia.

- McIlroy, Tom and Trudy Harris. 2025. What does that mean? Trump asks reporter what AUKUS is. 28 February. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/world/north-america/what-does-that-mean-trump-asks-reporter-what-aukus-is-20250228-p5lfuw.

- Mount, Adam, Van Jackson. 2021. Biden, You Should Be Aware That Your Submarine Deal has costs. 30 September. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/30/opinion/aukus-china-us-australia-competition.

- Münchau, Wolfgang. 2021. Aukus is a disaster for the EU. 17 September. The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/aukus-is-a-sign-of-eu-impotence/.

- Newey, Sarah. 2025. Chinese warships with ‘extremely capable’ missiles alarm New Zealand and Australia. 24 February. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2025/02/24/chinese-warships-missiles-new-zealand-australia/.

- O’Connor, Brendon, Lloyd Cox, and Danny Cooper. "Australia's AUKUS ‘bet’on the United States: nuclear-powered submarines and the future of American democracy." Australian Journal of International Affairs 77.1 (2023): 45-64. [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, Sean. 2023. What does the Aukus nuclear submarine deal mean for world politics? 15 March. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/politics-explained/nuclear-submarines-us-australia-uk-china-b2300759.html.

- Page, B. I. , and R. Y. Shapiro. 1983.“Effects of Public Opinion on Policy.” American Political Science Review 77(1): 175–90.

- Pager, Tyler and Anne Gearan. 2021. U.S. will share nuclear submarine technology with Australia as part of new alliance, a direct challenge to China. 16 September. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/09/15/us-will-share-nuclear-submarine-technology-with-australia-part-new-alliance-direct-challenge-china/.

- Parker, Jennifer. 2025. Far from ruinous, the US AUKUS review is routine. The Strategist. 14 June. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/far-from-ruinous-the-us-aukus-review-is-routine/.

- Perot, Elie. "The Aukus agreement, what repercussions for the European Union." European Issue n 608, Fondation Robert Schuman 27 (2021).

- Puri, Samir. "Britain’s Indo-Pacific Security and Trade Policies: Continuity and Change Under the Labour Government." East Asian Policy 16.04 (2024): 72-83. https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/S1793930524000291.

- Quiggin, John. 2023. $18 million a job? The AUKUS subs plan will cost Australia way more than that. The Conversation. 17 March. https://theconversation.com/18-million-a-job-the-aukus-subs-plan-will-cost-australia-way-more-than-that-202026.

- Rachman, Gideon. 2023. The grim reality behind AUKUS celebrations. Australian Financial Review. 14 March. https://www.afr.com/world/north-america/the-grim-reality-behind-aukus-celebrations-20230314-p5crtu.

- Rainnie, Al. "AUKUS and jobs." The Journal of Australian Political Economy 92 (2024): 217-223.

- Rees, Morgan. "AUKUS as ontological security–Australian foreign policy in an age of uncertainty." Australian Journal of International Affairs 79.1 (2025): 91-109.

- Roblin, Sebastien. 2021. Does Giving Australia Submarines that Use Highly Enriched Uranium Fuel Risk Proliferating Nuclear Weapons? 22 September. National Interests. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/does-giving-australia-submarines-use-highly-enriched-uraniumfuel-risk-proliferating.

- Ryan, Brad and Emilie Gramenz. 2025. US launches AUKUS review to ensure it meets Donald Trump's 'America First' agenda. 12 June. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-06-12/aukus-pentagon-review-donald-trump-america-first/105406254.

- Salganik, Matthew J. Bit by bit: Social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Scheffer, Alexandra de Hoop, Martin Quencez. 2021. The New AUKUS Alliance Is Yet Another Transatlantic Crisis for France. 17 September. https://www.gmfus.org/news/new-aukus-alliance-yetanother-transatlantic-crisis-france.

- Shoebridge, Michael. 2021. "What is AUKUS and what is it not?." http://ad-aspi.s3.amazonaws.com/2021-12/What%20is%20AUKUS%20and%20what%20is%20it%20not.pdf.

- Smith, Nicholas Ross, and Lauren Bland. "The AUKUS debate in New Zealand misses the big picture." Australian Journal of International Affairs 78.5 (2024): 652-659.

- Tillett, Andrew. 2025. Trump’s review may not be the biggest threat to AUKUS. 13 June. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/trump-s-review-may-not-be-the-biggest-threat-to-aukus-20250612-p5m6wd.

- Tovey, Alan. 2021. Rolls-Royce and BAE set to benefit after Australia spurns French submarines. 16 September. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2021/09/16/rolls-royce-bae-set-benefit-australia-spurns-french-submarines/.

- Truss, Liz. 2021. Global Britain is planting its flag on the world stage. 18 September. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/09/18/global-britain-planting-flag-world-stage/.

- Türkcan, Muhammed Lutfi. "AUKUS and the Return of Balance of Power Politics." TRT World Research Centre Policy Outlook (2022). https://researchcentre.trtworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Aukus-1.pdf.

- Tzinieris, Sarah, Rishika Chauhan, and Eirini Athanasiadou. "India’s A La Carte minilateralism: AUKUS and the quad." The Washington Quarterly 46.4 (2023): 21-39.

- Tzinieris, Sarah, Zeno Leoni, and Kevin Blachford. "Shedding Light on Chinese Thinking on AUKUS." Pacific Focus 39.3 (2024): 499-528. [CrossRef]

- Umar, Ahmad Rizky M., and Yulida Nuraini Santoso. "AUKUS and Southeast Asia's ontological security dilemma." International Journal 78.3 (2023): 435-453.

- Varghese, Peter. 2023. The balance sheet of the nuclear subs deal. Australian Financial Review. 16 March. https://www.afr.com/policy/foreign-affairs/the-balance-sheet-of-the-nuclear-subs-deal-20230315-p5csgi.

- Vyas, Heloise. 2025. Donald Trump's 'what does that mean?' AUKUS remark played down as verbal slip-up. 28 February. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-02-28/donald-trump-asks-what-aukus-means-after-keir-starmer-meeting/104993110.

- Whitman, Richard. 2021. AUKUS: The implications for EU security and defence. 24 September. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/aukus-eu-security-and-defence/.

- Wijaya, Trissia, and Ali Hayes. "AUKUS ‘behind the scenes’: through the lens of militarised neoliberalism." Australian journal of international affairs 79.1 (2025): 110-131.

- Wyatt, Austin, James Ryseff, Elisa Yoshiara, Benjamin Boudreaux, Marigold Black, And James Black. "Towards AUKUS Collaboration on Responsible Military Artificial Intelligence." (2024). https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA3000/RRA3079-1/RAND_RRA3079-1.pdf.

Figure 1.

AUKUS in Australia, the UK, and the US.

Figure 1.

AUKUS in Australia, the UK, and the US.

Table 1.

Driving Factors of AUKUS Narrative in Australia - Long-run Coefficients. Dependent Variable: AUKUS_AU (the natural log form of AUKUS in Australia). Method: ARDL. Maximum dependent lags: 12 (Automatic selection); Model selection method: Akaike info criterion; HAC standard errors & covariance. For Model A: Included observations: 198 after adjustments; Dynamic regressors (12 lags, automatic): China_Rise_AU; Fixed regressors: C @TREND; Selected Model: ARDL(3, 4). For Model B: Included observations: 199 after adjustments; Dynamic regressors (12 lags, automatic): China_Influence_AU; Fixed regressors: C @TREND; Selected Model: ARDL(3, 0). For Model C: Included observations: 199 after adjustments; Dynamic regressors (12 lags, automatic): China_Threat_AU (the natural log form of China Threat in Australia); Fixed regressors: C @TREND; Selected Model: ARDL(3, 0).

Table 1.

Driving Factors of AUKUS Narrative in Australia - Long-run Coefficients. Dependent Variable: AUKUS_AU (the natural log form of AUKUS in Australia). Method: ARDL. Maximum dependent lags: 12 (Automatic selection); Model selection method: Akaike info criterion; HAC standard errors & covariance. For Model A: Included observations: 198 after adjustments; Dynamic regressors (12 lags, automatic): China_Rise_AU; Fixed regressors: C @TREND; Selected Model: ARDL(3, 4). For Model B: Included observations: 199 after adjustments; Dynamic regressors (12 lags, automatic): China_Influence_AU; Fixed regressors: C @TREND; Selected Model: ARDL(3, 0). For Model C: Included observations: 199 after adjustments; Dynamic regressors (12 lags, automatic): China_Threat_AU (the natural log form of China Threat in Australia); Fixed regressors: C @TREND; Selected Model: ARDL(3, 0).

| Variable |

Model A |

Model B |

Model C |

| |

Coefficient |

Prob. |

Coefficient |

Prob. |

Coefficient |

Prob. |

| China_Rise_AU |

0.002 |

88.5% |

|