1. Introduction

Pulsed power’s evolution to submicrosecond pulsed electric fields—Pulsed power technology has advanced from basic high-voltage discharges to applications in defense, energy, industry, and more recently, biology and medicine [

1]. It originated in the 1920s with the development of high-voltage pulse generation, rooted in early research on voltage discharge systems and spark gaps. During World War II, breakthroughs in high-voltage pulse technology were driven by radar and early particle accelerators. In the postwar period, pulsed power became essential for nuclear weapons testing and simulations, magnetically driven fusion experiments, and initial plasma physics research. In the 1970s and 1980s, it found applications in medical and biological fields, utilizing millisecond pulses for lithotripsy and both millisecond and microsecond pulses for electroporation. Electroporation allowed for the delivery of DNA and impermeant drugs into cells and tissues [

2]. By the mid-1990s, pulsed power expanded to include sub-microsecond pulses, especially nanosecond and picosecond durations for biomedical and medical purposes [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The idea of amplifying power through ultrashort pulses in the megawatt and gigawatt ranges involved creating an electric field-dependent effect that is independent of energy and heating. As pulse duration shortens and/or the electric field rise increases, the frequency spectrum of pulsed electric fields contains increasingly higher frequencies. When pulses are shorter than the plasma membrane’s charging time, with significant spectral components above the β-frequency, the chance of electric field interactions with intracellular structures increases significantly, allowing access to intracellular membranes [

3,

4,

5,

6,

8,

9]. This nanosecond stimulation differs from traditional microsecond or millisecond electroporation pulses because charges pass through the cell, affecting intracellular structures and functions, rather than merely passing around the cells and mostly impacting the plasma membrane [

10]. The first major use of submicrosecond pulses involved nanosecond pulse durations, called nsPEFs or ns electric pulses (nsEPs), also known as nanopulse stimulation (NPS). This term indicates these pulses can stimulate some cell mechanisms beyond ablation and RCD, including immunity. Nonetheless, Pulse Biosciences, Inc. (Nasdaq: PLSE) has mainly applied this technology clinically for ablation, referring to it as nanosecond pulsed field ablation (nsPFA). Pulse Biosciences is continuing to develop its nsPFA technology to treat tumors [

11,

12,

13], as well as other markets such as surgical soft tissue ablation, including recent reports on the safe and effective treatment of symptomatic benign thyroid nodules with minimal side effects [

13]. More recently, studies with picosecond pulses (psPEFs) have demonstrated specific effects on calcium mobilization [

14] and electroporation [

15]. It was also shown that psPEFs could operate through an antenna to target deeper tissues [

4,

16,

17]. PsPEFs also showed cell type-dependent effects on cell proliferation in neuronal stem cells, which exhibited characteristics of astrocyte-specific differentiation [

18]. The applications of pulsed power beyond pure physics open new possibilities for this technology in biology and medicine.

Four cancer cell models were used to study NPS as a potential immunotherapy. NPS-induced immunity functions as an in situ vaccine (ISV) in the N1-S1 liver cancer and 4T1-luc mammary cancer models. The N1-S1 liver tumors were treated with a five-needle electrode array [

19], with the central needle positive and four surrounding needles as ground. This specifically defines the NPS zone within the electrodes. The mouse 4T1-luc tumors were treated with a 2-plate pinch electrode with an 8 mm diameter, with the treatment zone between the electrodes. Both tumor models received NPS conditions of 100 ns at 50 kV/cm and 1000 pulses at 1-3 Hz. The B16f10 melanoma and Pan02 pancreatic cancer did not show immune responses. The B16f10 tumors were treated with a 2-plate pinch electrode with NPS conditions of 100 or 200 ns duration, applied at 50 kV/cm, with 1000 pulses at 1-3 Hz. The Pan02 tumors were also treated with a 2-plate pinch electrode at 200 ns, 30 kV/cm, and 600-1200 pulses at 2 Hz. All tumor models are considered cold tumors, characterized by low tumor mutational burden (TMB), a lack of significant tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes (TILs), and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) containing T-regulatory cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which hinder immune activity and block anti-tumor responses. Despite all models being classified as rat or mouse cold tumors, there are two fundamentally different model types: rat liver and mouse mammary orthotopic models, meaning tumors implanted into their original tissues, and mouse Pan02 pancreatic and B16f16 melanoma ectopic models, where tumors are placed subcutaneously. The orthotopic models induced ISV, possibly highlighting the key immune features provided by the TME, which seem to be present in orthotopic models and likely absent in ectopic ones. However, other factors prevent ISV in ectopic models. The liver model is unique because it is a “specialized anatomical and immunological site” [

20], with its own lymphatics, antigen-presenting cells, and lymphocytes that flow into a network of sinusoids, filtering blood rich in antigens from the gastrointestinal tract and innate immune cells. The liver acts as a frontline immune barrier to blood from the intestines, carefully balancing immune tolerance with strong defenses against pathogens.

NPS can induce ISV. While studies with NPS showed significant effectiveness in killing bacteria for decontamination purposes, it was reasonable to believe they could also kill cancer cells, which they did [

7,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Today, NPS is widely recognized for ablating cancer [

11,

21,

22]. Recent research has shown that they can not only eliminate tumors but also induce immune system-mediated vaccine effects, or

in situ vaccinations (ISVs). Two ISV cancer models include rat N1-S1 liver cancer [

19] and murine 4T1-Luc mammary cancer [

25,

26,

27]. However, two other models, mouse B16f10 melanoma and Pan 02 pancreatic cancer, could eliminate tumors but did not induce ISV. By analyzing the immune responses in these four animal cancer models, differences were identified that explain, at least in part, the conditions that prevent ISV and those necessary for it. This has led to the observation that immunosuppression, a primary cancer survival mechanism, must be overcome in the presence of active cytotoxic CD8+ T cells or active natural killer cells (NKs) or NK T cells

.

Conditions for immunity – [28] To activate immunity, three key factors and molecular interactions must come together. The first is antigenicity, which involves high or low tumor mutation burden (TMB) caused by cancer neoantigens. The second requirement for immunity is adjuvanticity, which results from the release of danger signals called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from dying cancer cells. The third condition is a supportive tumor microenvironment. This means antigens must be present, and immune activation must also occur through the activation of DAMPs within a favorable microenvironment for anti-tumor immunity to develop. Even if cancer antigens are present, cells need to undergo cell death involving the release of immunogenic factors (DAMPs), resulting in what is called immunogenic cell death (ICD) when accompanied by robust immune responses, especially activation of dendritic cells that can cross-react with T-cells. This suggests that the immune system might respond more strongly to danger signals than to foreignness (self-versus-non-self) [

29].

The Role of Antigens in cancer can be categorized as cold or hot. Cold cancer models have very low TMB, meaning they harbor few genetic mutations and are therefore less antigenic. Hot tumors have high TMB and numerous genetic mutations that produce neo-antigens—new proteins expressed by cancers that are recognized by the immune system. All tumor models discussed here are cold tumors with low antigenicity and are essentially invisible to the immune system, making them more resistant to immunotherapy. This presents a significant challenge because, to induce immunity, the NPS must be strong enough to promote the presence of neo-antigens and include adjuvants to trigger an immune response.

A Role for Adjuvants - When cell sensors detect environmental stress and danger, efforts to restore balance are coordinated. If cells cannot recover, they shift to promote regulated cell death (RCD), which involves programmed processes that are genetically encoded [

30]. Our understanding of cell death has expanded to include over a dozen RCD mechanisms [

30]. Kerr et al., [

31], were the first to discover an RCD mechanism they called apoptosis, from the Greek meaning “falling off,” based on morphological features. They defined it as a naturally occurring cell death, like leaves falling off trees, involved in development, and distinguished it from necrosis (meaning dead), which is caused by acute injury and is perhaps best referred to as accidental cell death [

30]. Other mechanisms, such as necroptosis and pyroptosis, sometimes called regulated cell necrosis, trigger inflammatory RCD responses. For immunity to occur, cell death mechanisms must include ICD signaling, which is not a specific RCD mechanism itself but occurs as a subroutine in some RCD mechanisms when characterized by its ability to produce DAMPs and induce immune responses [

32,

33]. So far, at least four ICD mechanisms within RCD have been identified, each relying on the emission and detection of specific DAMPs [

30]. DAMPs are adjuvants that function as endogenous molecules signaling the presence of cellular danger or stress to the immune system. They are expressed by damaged or dying cells recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on immune cells. Examples include ATP, which recruits antigen-presenting cells (APCs, dendritic cells, DCs); high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), which promotes the synthesis of proinflammatory factors like IFNs; calreticulin (CALR), heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), which promote the uptake of dead-cell associated antigens [

30]. In general, these DAMPs activate immune cells and stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, initiating an immune response. ICD can be part of several RCD mechanisms.

A role for permissive TME - A permissive environment influences whether cancer cells can evade immune surveillance. This includes how the tissue microenvironment and systemic immune system can either support or hinder effective anti-tumor immunity. As shown in the four cancer models presented here, a key aspect is overcoming immunosuppressive TME. This involves removing (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). It is also vital for converting a cold tumor into a hot tumor. This includes loosening the dense extracellular matrix and abnormal blood vessel structures that block immune cell infiltration into the tumor [

34]. It also helps if NPS can promote neo-antigen presence and increase the TMB. Overall, the goal is to develop a therapy that transforms a cold, immunosuppressive tumor into a hot tumor with active immune infiltration and response.

NPS and RCD - NPS was initially shown to induce RCD through apoptosis in Jurkat cells [

7]. Later, it was demonstrated in Jurkat cells that NPS could trigger caspase-dependent apoptosis at lower electric fields and caspase-independent RCD mechanisms at higher electric fields [

35]. NPS-induced cell death also varies depending on the cell type [

36]. Interestingly, apoptosis was identified as an RCD mechanism through in vitro caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation in rat N1-S1 liver cancer cells [

37], but not in 4T1-luc mammary cancer in mice (both of which induce ISV) [

25,

26], Pan02 pancreatic cancer [Guo et al., unpublished], or mouse B16f10 melanoma [

38]. Caspase-3 and caspase-9 RCD were observed

in vivo in the B16f10 tumor microenvironment (TME), indicating intrinsic cell death [

39], but this was due to apoptosis in host cells within the tumor microenvironment, given that apoptotic cell death was not observed

in vitro in B16f10 melanoma [

38]. Instead, B16f10 cell death was described as necrosis, which does not specify a particular cell death mechanism. The authors showed that cell death was time-dependent (indicating it was not accidental cell death, ACD, or frank necrosis), and RIP-3 was absent, so the B16f10 RCD mechanism was not necroptosis. Necroptosis and pyroptosis are RCD mechanisms often described as regulated necrosis because they involve cell membrane permeabilization like ACD but instead utilize regulated intracellular protein pore-forming mechanisms [

40]

.

NPS and ICD. ICD is not a cell death mechanism itself. It is a subroutine of RCD mechanisms or of accidental cell death (often called necrosis). Several DAMPs were identified in the NPS of 4T1-luc tumors. Calreticulin, HMGB1, and ATP were recovered after NPS treatment of 4T1-luc cells [

25]. Since these cells demonstrated ISV and defined immune mechanisms, it can be said they died including activation of subroutines of ICD, although their RCD mechanism has not been specifically defined. DAMPs were not found in B16F10 melanoma cells [

39]. This is at least one reason why NPS does not induce immunity in B16F10 melanoma. However, NPS-induced DAMPs have been detected in other cell types, including MCA205 murine fibrosarcoma, McA-RH7777 rat hepatocarcinoma, and Jurkat human T-cell leukemia. None of these examples confirmed aspects of immunity. Therefore, these cells died with the release of ICD markers, but there was no data indicating that they died because of the release of these DAMPs, since no immunity characteristics were identified [

41].

2. NPS Induction of ISV After N1-S1 Liver Tumor Elimination [18]

Recent evidence shows that radiation induces DAMPs and ICD, which can stimulate and enhance a strong anti-tumor immune response in tumor cells and function as an ISV [

42,

43]. Other physical methods, including ultraviolet light, hydrostatic pressure, photodynamic therapy, and mild hyperthermia, also show some evidence of triggering ICD [

44]. Radiotherapy and mice “vaccinated” with dendritic cells loaded with irradiated cancer cells become immune to challenge with live syngeneic cells [

45]. It has been proposed that NPS, as a physical modality, could potentially induce immunity and ISV. In fact, NPS produces durable immunity in rat N1-S1 liver cancer (up to 8 months) [

19] and mouse mammary cancer [

25,

26,

27].

NPS treatment encourages lymphocyte infiltration into the N1-S1 TME. In an early study using the rat N1-S1 model, it was observed that after removing N1-S1 tumors, a challenge injection of N1-S1 liver tumor cells did not result in tumor formation. In a detailed study [

37], 23 of 25 tumors were eliminated; the remaining two failures were likely due to incomplete coverage of the tumor with the NPS. Among those challenged, none of the rats developed tumors. This was carefully described as a vaccine-like effect [

37], indicating that NPS functioned as a systemic vaccination (ISV).

These findings prompted further investigation into the immune response after NPS treatment, revealing that the therapeutic effect of NPS extends well beyond cytotoxicity. NPS activates both innate and adaptive immune systems [

19]. Following NPS, significant increases in influxes of granzyme B-secreting T-cells [

37], dendritic cells (CD 11c), activated CD4+ and CD8+ T effector memory cells (Tem, CD44+ CD62L-), as well as T central memory cells (Tcm, CD44+, CD62L+) [

19], were observed. Additionally, CD8+ T cells were shown to be cytotoxic against N1-S1 cells. Two weeks after NPS treatment of N1-S1 tumors, isolated splenic CD8+ T cells induced intrinsic apoptosis in vitro, as evidenced by annexin V binding and activated caspase 3. This indicates that these CD8+ T cells are cytotoxic to N1-S1 liver cancer cells [

19]. In other studies, intrinsic apoptosis was demonstrated in N1-S1 cells through in vitro activation of caspases 9 and 3 and in vivo activation of caspases 9 and 3, but not caspase 8 [

37].

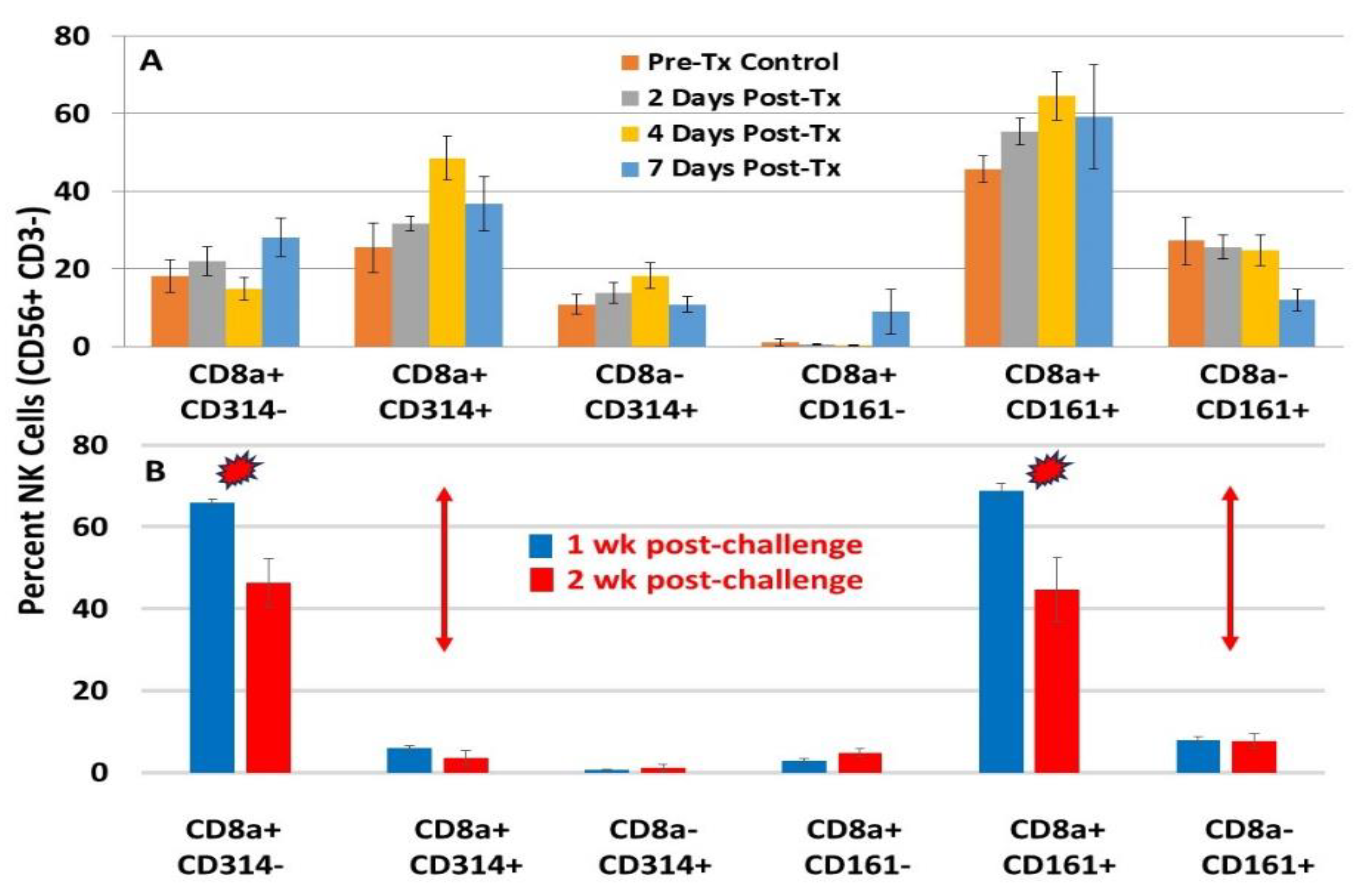

In addition to adaptive immune T-cell phenotypes in the N1-S1 liver cancer model, innate immune cells are also present, including natural killer (NK) cells (CD56+ CD3-) and NK-T cells (CD56+ CD3+). Both NK and NK-T cells can express CD8, a co-receptor usually associated with T cells that helps recognize antigen-presenting cells expressing MHC I molecules. This indicates a distinct functional subset of NK/NK-T cells based on CD8 expression. Another unique subset of these cells expresses CD161 or CD314 (NKG2D). NKG2D is a key activating receptor for NK and NK-T cells. Cells with NKG2D, along with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), are the first responders of innate immunity. This is supported by the observation that increases in NK and NK-T cells expressing CD314 (NKG2D)+ occurred first in the liver tumor microenvironment in response to NPS-induced stress.

These NK and NK-T cells are crucial for the initial immune defense against cancers and pathogens, regulating liver injury and recruiting circulating lymphocytes. NK cells are innate lymphocytes that focus on detecting and destroying infected or malignant cells. They also produce cytokines, especially IFNγ, which boosts antigen presentation by malignant cells [

46]. NK cells secrete chemokines such as XCL1 and XCL2 that attract dendritic cells to the tumor microenvironment [

47,

48,

49]. Many studies, including clinical trials, aim to increase NK cell numbers and enhance their activity as a form of immunotherapy [

50].

NK cells operate quite differently from T-cells. Unlike T-lymphocytes, NK cells lack specific antigen receptors. Instead, they function based on a balance of inhibitory and activating signals. This is explained by the missing-self hypothesis, which states that NK cells are usually inhibited by signals from healthy (self) cells, primarily Major Histocompatibility Complex class I (MHC-1) molecules, and become active when these signals are significantly reduced or absent. They also recognize “induced-self” ligands MICA and MICB (MICA/B) via NKG2D, which are not expressed or are expressed at low levels on most normal cells but are upregulated in response to cellular stress, infection, or malignant transformation. In these conditions, cancer cells increase the expression of NKG2D ligands MICA/B on their surface, shifting the balance from inhibitory to activating signals. Several activating receptors are present on NK cells, with NKG2D (CD314) being the most well-characterized. The NKG2D/MICA/B axis defines “induced-self” recognition, wherein innate immune cells detect these ligands. NKG2D ligands, such as MICA and MICB, are major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA) and B (MICB). When recognized, the NKG2D receptor activates NK cells. Although the NKG2D: MICA/B axis is not traditionally classified as a pattern recognition receptor (PRR) system, it works alongside TLR- PRR-mediated signaling to produce a comprehensive antitumor response. The presence of T-cells, NK cells, and NK-T cells in the TME indicates that NPS has transformed N1-S1 liver cancer from a cold tumor to a hot tumor. This transformation is partly due to NPS modifying the immunosuppressive TME, making it more accessible to immune cell infiltration. It is also specifically related to reversing the TME from a suppressive to an active state.

NK and NK-T cells (not shown), characterized by CD8a+ CD314 (NKG2D)+ and CD8+ CD161+, were abundant in the liver’s lymphocyte populations after NPS (

Figure 1A). However, after tumor elimination and during challenge, only NK and NK-T cells (not shown) expressing CD8+ and CD161+ were present, without those expressing CD8+ CD314 (NKG2D)+ (

Figure 1B). This suggests that NK and NK-T cells expressing CD8+ and CD314 (NKG2D) are specifically activated by NPS. Without NPS-induced cancer cell ligand MICA/B stimulation, expression of CD314 (NKG2D) decreases. Conversely, the phenotype of NKs or NK-Ts expressing CD8a+ and CD161+ persists as tissue-resident memory-like NK / NK-T cells [

54] and remains after tumor elimination and subsequent challenge. CD161+ NK cells are “licensed” by prior activation and retained in the liver, enabling them to respond more effectively upon tumor rechallenge—even without NKG2D ligands. These cells have been linked to long-lived tissue-resident NK cells (especially in the liver), enhanced recall responses similar to memory T cells, and crosstalk with cytokines (IL-12, IL-18, IL-15) that can “imprint” memory-like features. After NPS clears the primary tumor, the remaining CD161+ NK population functions as a memory-like reservoir, mediating protection during tumor rechallenge. The persistent presence of these memory-like NK / NK-T cells is a vital component of NPS-induced ISV.

Other characteristics of post-challenge memory cells included increases in the blood of NPS mice of memory precursor effector cells (MPECs, CD4+ CD127+ KLRG-), and short-lived liver effector cells (SLECs, CD4+ CD127- KLRG1+). CD127+ cells mature into long-lived, protective memory CD8+ T-cells after an immune challenge. KLRG1+ cells are terminally differentiated, short-lived effector T cells that arise in response to strong inflammatory signals during infection, likely driven by NPS in the liver. Interestingly, no CD8+ MPECs were present in the blood, although there were large numbers of CD8+ SLECs. There were no significant increases in MPECs or SLECs during NPS of N1-S1 liver tumors. Tem and Tcm cells were present during NPS and after challenge.

Resolution of Treg Immunosuppression in N1-S1 Tumors [

19]

: Hepatic immunosuppressive Tregs were defined using CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ phenotypes. Two days after NPS treatment, Tregs significantly increased compared to naïve and pre-treated levels. However, Treg levels significantly decreased on days 4 and 7 following NPS treatment. Although other immunosuppressive cells were not characterized in these studies, a more comprehensive examination of the removal of immune suppressor cells will be presented

below in the studies involving NPS treatment of 4T1-luc mammary cancer cells. Nevertheless, the decline in immunosuppressive Tregs and the appearance of active immune T-cells, NKs, and NK-Ts clearly support the formation of ISV in NPS-treated N1-S1 tumors in the rat liver.

In summary, orthotopic rat N1-S1 liver cancer treated with NPS showed tumor ablation along with durable, tumor-specific immunity lasting up to 8 months; reduced Tregs, increased DC influx, granzyme B-expressing cells, and dynamic responses from NK/NK-T and CD4+ CD8+ T-cells. NPS transformed the TME, turning a cold tumor into a hot one.

The first prospective multicenter human liver clinical trial evaluated the effectiveness and safety of nsPEF (NPS) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in high-risk locations [

55]. The study involved 192 patients across five hospitals in China. Results show that nsPEFs could serve as an alternative treatment for HCCs when thermal ablation is not suitable. Technical success was achieved in 99.5%, with complete ablation in 91.7% of 217 tumors. Recurrence-free survival rates at 1, 2, and 3 years were 72.2%, 51.7%, and 43.5%, respectively. This study was single-armed (lacking a control group). A randomized controlled trial is needed to further confirm nsPEFs' effectiveness in treating HCC and to compare its potential benefits over other treatments, such as transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) and others

.

3. NPS Induction of ISV After Elimination of 4T1-Luc Mammary Tumor [25,26]

NPS response to orthotopic 4T1-luc mammary cancer tumors in mice is another example of ISV. The studies in this model demonstrated that after ablation, a complex, multi-layered immune mechanism triggers a vaccine-like effect. NPS destroys primary 4T1-luc tumors by inducing immunogenic, caspase-independent cell death. NPS-treated 4T1-luc cells release DAMPs including calreticulin, HMGB1, and ATP, which lay the foundation for ICD, adding the adjuvanticity component to immunity [

28]. However, at this stage, one can only assume that these ICD adjuvants were associated with tumor death and activated immunity. Confirming ICD requires evidence that the adjuvants caused immunity and ISV. Based on what follows, these 4T1-luc cells have died including ICD because multiple immune mechanisms were involved leading to ISV.

NPS turns cold 4T1-luc tumors hot - The increased expression of IFNγ by T-cells within the TME indicates a key factor that influences tumor immunity. IFNγ promotes the differentiation and activation of cytotoxic T-cells. It can also decrease tumor growth and enhance apoptotic signaling. Additionally, IFNγ can interfere with tumor immune evasion by reducing T-regs and MDSCs in the TME [

46,

56]. IFNγ-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in 4T1-luc tumor-bearing mice increased. The activation marker CD40 also increased [

25]. When splenocytes from tumor-bearing animals were co-cultured with tumor lysate, IFNγ levels also rose. Significant amounts of IFNγ were released from splenocytes of tumor-free mice in response to tumor antigens within 24 hours, but not from naïve mice [

25].

In NPS-treated tumors, CD4+ and CD8+ T memory cells increased [

25]. Early anti-tumor immune responses appeared as tissue-resident immune cells (Trm). In later studies [

27], after NPS treatment, CD103+ CD8+ T-cells resident memory cells (Trm) continued to rise during the first week. Tissue effector memory (Tem, CD44+ CD62L-) and central memory (Tcm, CD44+ CD62L+) cells increased over three days following treatment [

27]. Additionally, IFNγ-producing CD8+ T-cells in the spleen were significantly elevated [

25,

27]. Trm cells from the spleen also expressed significantly higher levels of IFNγ, demonstrating CD8+ cell activation with enhanced tumor toxicity and immunity. Like the N1-S1 tumor model, NPS treatment of 4T1-luc tumors alters the tumor microenvironment, transforming cold tumors into hot tumors and enhancing tumor regression.

NPS also prevented distant metastasis in the 4T1-luc metastatic model [

25]. In mice treated with an intermediate lethal condition (600 pulses, 100ns, 50kV/cm instead of 1000), half of the mice were tumor-free, and half received incomplete treatment, which led to tumor regrowth two weeks after treatment, although at a slower rate than in untreated tumors. Analysis of luminescence in isolated organs showed that distant metastasis in the liver, lungs, or spleen occurred in 82% (9/11) of control mice. Conversely, 86% of mice that were incompletely treated showed no metastasis. This indicates that the prevention of spontaneous metastasis was due to NPS-induced anti-tumor immunity.

4. NPS Reverses Immunosuppression Dominance in Mouse Mammary TME and Elicits ISV [27]

Having observed the expression of DAMPs from these 4T1-luc mammary cancer cells [

25], the influx of DCs, and early activation of memory cells (days 2-7 post NPS), it follows that the NPS-induced DAMPs recruited APCs / DCs, promoted the uptake of dead-cell associated antigens, and stimulated the production of IFNs. This led to the early presence of Trm, Tem, and Tcm cells in 4T1-luc mammary cancer cells. Therefore, NPS not only killed cancer cells but also triggered multiple layers of immune mechanisms. It is also noteworthy that heterogeneous electric field strengths, which can occur in or around the NPS tumor-killing zone, may activate DCs, as demonstrated in in vitro experiments [

25].

A major challenge for immunotherapy is overcoming immunosuppression within the TME) and related tissues. In the 4T1-luc mammary cancer models, three key immunosuppressive cell types were studied: Tregs, MDSCs, and TAMs. Initially, untreated controls showed Tregs predominating in the draining lymph nodes (dLN), spleen, and blood. After NPS treatment, the frequencies of Tregs consistently decreased both locally and systemically, as observed from 4 hours to 7 days afterward. NPS specifically reduced Tregs while sparing CD4 and CD8 T conventional (Tconv) cells. This was demonstrated by the percentage of Tregs among CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) dropping more than threefold by day 3 post-treatment. Notably, NPS caused apoptosis preferentially in activated Tregs compared to naïve Tregs, as indicated by Annexin V binding. Treg frequencies declined in the TME, dLN, spleen, and blood following NPS. Conversely, the levels of conventional T cells (Tconv) also decreased but to a lesser extent, leading to about a threefold increase in the intratumoral Tconv to Treg ratio on days 3 and 7 post-treatment. Both activated (CD44+ CD62L-) and naïve (CD44- CD62L+) T-cell populations were the only groups showing increased apoptosis. Although low levels of apoptosis were observed in naïve T cells, apoptotic activated T cells were significantly more abundant. Activated Tregs are more likely to be affected by NPS than resting Tregs for several reasons. Active Tregs rely heavily on mitochondrial function, which is targeted by NPS. NPS induces Ca2+ influx, and activated Tregs already have elevated Ca2+ levels supporting their function, making them more vulnerable to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload. NPS also increases reactive oxygen species (ROS), and Tregs likely have weaker antioxidant defenses and reduced anti-apoptotic reserves, making them more susceptible to mitochondrial stress caused by NPS.

In vitro Treg suppression activity was also reduced [

27]. Tregs were isolated from the dLNs of NPS-treated mice and incubated with CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells at various Treg/CD8+ T-cell ratios in the presence of activation beads. At a 1:1 ratio, NPS-treated Tregs showed a 50% decrease in their suppressive function. Further analysis evaluated whether NPS treatment altered different activation markers on T cells. The decline in Treg suppression ability can be linked to the downregulation of activation markers, especially 4-1BB and TGFβ. Focus was on Tregs expressing 4-1BB, a co-stimulatory receptor involved in T-cell activation, belonging to the TNFR superfamily, found on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. 4-1BB on Tregs may promote their proliferation and boost their immunosuppressive role within the TME. This contributes to a more immunosuppressive environment by expanding the Treg population and increasing suppressive factors like TGFβ [

57]. In 4T1-luc tumor-bearing mice, 4-1BB was expressed on Tregs in the dLNs, tumors, and spleens. However, it was not detected on Tregs in the blood, naive tissues, or on conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in naive or untreated tumor-bearing mice. A significant decrease in the total number of 4-1BB+ Tregs was observed in the dLN and spleen between Days 1–7 after NPT. Interestingly, there was a twofold increase in 4-1BB Tregs four hours after treatment, but a sevenfold decrease by Day 7 post-treatment. The reduced Treg suppression capacity is best explained by the downregulation of activation markers, particularly 4-1BB and TGFβ, along with a phenotypic shift from active to naive Tregs, changing the active/naive Treg ratio from 2:1 to 1:2 three days after treatment.

Other immunosuppressive phenotypes exhibited the same NPS-induced disappearance effect: NPS continually reduced TAMs from day 1 to day 3 after treatment, resulting in about a 10-fold decrease in the dLNs by day 3. Similar to the decline in Treg cells, NPS-triggered cell death in TAMs occurred through apoptosis. MDSCs showed different dynamic patterns, increasing on the first day after treatment before decreasing by day 3. MDSCs did not die via apoptosis, and the mechanism of cell death was not examined. Interestingly, caspases have paradoxical roles that can induce cell signaling, promoting apoptosis-induced proliferation by secreting mitogens that affect neighboring surviving cells, and they also play roles in replacing dying cells through wound healing and tissue regeneration [

58]. The effects NPS might have on resolving the TME through these mechanisms remain to be explored.

Overall, NPS suppressed at least three immunosuppressive cell phenotypes and changed the TME from a cold, immunosuppressed tumor to a hot tumor with more active T cells and fewer Tregs, TAMs, and MDSCs. This enhanced the activation and function of TIF CD8+ cells.

The NPS tumor cell death occurred through an ICD mechanism because the expression of calreticulin and the release of ATP and HMGB1 were evident [

25]—well-known molecules with DAMPs involved in immunogenic cell death (ICD) [

28], as well as the presence of active memory T-cells. While DAMPs and ICD are induced, the exact cell death mechanism is not apoptosis [

26], but remains unknown. Nonlethal levels of NPS have been shown to activate DCs, as indicated by increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules [

25]. Furthermore, extracts from 4T1-luc cells treated with lethal NPS incubated with mouse bone marrow-derived DCs increase the expression of co-stimulatory receptors, which help recognize and cross-present antigens to T lymphocytes, suggesting the potential to develop immunological memory [

25]. Overall, NPS promotes coordinated changes in both lymphoid and myeloid immune systems, shifting the TME from an immunosuppressive to an immunostimulatory state as part of the nsPEF-induced immune response [

27].

NPS eliminates Pan02 tumors without inducing ISV [59].

NPS induced a pulse number-dependent regression of Pan02 tumors, especially in smaller treated tumors. To achieve a 78% regression rate, 1200 pulses at 1 Hz under NPS conditions of 200 ns, 30 kV/cm were required; however, regression was only about 23% in larger tumors, likely because the entire tumors were not fully exposed to high electric fields using the 2-plate pinch electrode. Among the tumor-free mice, only 1 out of 15 showed ISV. When NPS with 100 ns, 500 kV/cm, and 1000 pulses was used, only 1 of 3 mice exhibited ISV. Using irreversible electroporation (IRE), which involved conditions of 100 µs durations, 2-2.5 kV/cm, and 90 pulses at 1 Hz, none of the 5 treated mice with eliminated tumors showed ISV. Interestingly, recurrent tumor growth after IRE was accelerated, a phenomenon not observed with NPS-treated tumors [

59].

The effects of NPS on abscopal tumors were limited. For abscopal effects, two tumors were implanted on opposite flanks; one large tumor was treated, and a smaller one was left untreated. When larger tumors were ablated with NPS, 9 out of 10 smaller tumors grew. The lower effectiveness of NPS on abscopal tumors is likely partly due to the immunosuppressive TME, which NPS clears in liver and mammary cancer models. In the NPS TME, Tregs increased on day 2 after treatment but disappeared by day 7. MDSCs were present at similar levels on day 2 as in pre-treated mice but were significantly reduced and remained abundant on day 7. DCs were activated, indicated by increased levels of co-stimulatory molecules MHC II, CD86, and CD40. However, there were no increases in memory cell numbers, such as Tem (CD44+ CD62L-) or Tcm (CD44+ CD62L+). Therefore, the Pan02 tumors remained relatively cold after NPS, likely due to minimal infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells and a highly immunosuppressive TME.

Generally, Pan02 tumors proved more difficult to eliminate compared to N1-S1 liver and 4T1-luc mammary cancer. These findings suggest several reasons for the poorer response of NPS in the Pan02 model. It was observed that Pan02 tumors exhibited greater impedance [

60], indicating that a higher energy level might have been necessary. Although the study was small, this was implied by the more effective ISV with NPS conditions of 50 kV/cm and 100 ns (1 in 3) versus 200 ns and 30 kV/cm (1 in 17).

5. TLR Agonist Adjuvant and Full T-CELL Activation Enhanced the Effectiveness of NPS Against Ectopic Pan02 Tumors [61]

Pan02 tumors were treated with two NPS conditions, including a mid-dose of 180 mJ/mm³ and a high dose of 360 mJ/mm³, both with and without resiquimod (RES), a Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist. In the mid-dose groups, the clearance was 57% without RES and 81% with RES. For the 360 mJ/mm³ dose, clearance was 86% without RES and 82% with RES. However, only the 180 mJ/mm³ dose in the presence of RES significantly prevented the growth of a rechallenge re-injection of live Pan 02 cancer cells. NPS combined with the TLR agonist RES was identified as an optimal regimen for both eliminating the primary tumor and preventing the growth of rechallenge Pan 02 cells. These results suggest that an immune response had been initiated. This is further supported by a 35% reduction in rechallenge growth after depleting CD8 cells, indicating an incomplete role for CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells in the immune response. Furthermore, stimulation of T-cells with the OX40 agonist, which acts as a co-stimulatory molecule for T-cell receptor activation, completely prevented all rechallenged tumor growth (10/10) and 80% of untreated abscopal tumor growth (8/10). The presence of OX40 increases cytokine production and memory cell formation, while Tregs are likely suppressed. The OX40/OX40L axis is essential for effective immune responses against infections and cancers [

62], and full activation of T-cells with OX40 was necessary in Pan02 to replicate the immune response observed in N1-S1 liver and 4T1-luc mammary cancers treated with NPS alone.

Compared to the NPS of 4T1-luc tumors [

25,

27], results with Pan02 tumors indicate that the NPS does not effectively stimulate the production of adjuvant or OX40, which are necessary to properly activate T-cells for immunity.

NPS of ectopic B16f10 tumors without induction of ISV [63].

The B16f10 was the first cancer model used widely to demonstrate NPS tumor clearance [

23,

24]. In initial studies [

23], 300 ns pulses over 20 kV/cm seemed sufficient to reduce tumor growth. Later studies showed that NPS with 300 ns pulses at 40 kV/cm could eliminate 24% of tumors with a single treatment. However, some tumors required a second treatment (59%) or sometimes a third (18%) for complete elimination [

24]. Nonetheless, NPS had a significant effect on tumor structure [

39]. Treated tumors displayed densely stained, condensed, and elongated nuclei. NPS melanomas showed individual cells scattered from tumor cords with coarse intracellular melanin granules and aggregated extracellular melanin. There were decreases in both the number of vessels within tumors and the vessels supplying them. Additionally, markers of micro-vessel density such as CD31 and CD34 significantly declined, along with CD105, an endothelial marker linked to proliferation. Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived endothelial growth factor (PD-ECGF) were also reduced. Therefore, NPS clearly targeted conditions necessary for angiogenesis [

39].

In studies by Ruedlinger [

63], 100 ns and 200 ns pulse durations were used, each with 50 kV/cm and 1000 pulses at 1-2 Hz. For eliminating primary tumors, the 100 ns regimen cleared 64% (7:11), while the 200 ns treatment cleared 50% (6:12). In rechallenge studies, only 14% (1:7) of tumors cleared by 100 ns pulses failed to regrow. For tumors treated with 200 ns pulses, 50% (3:6) failed to regrow tumors. The immune phenotype studies used the 200 ns conditions. In other studies with B16f10 tumors, NPS at 360 mJ/mm³ cleared 90-100% of tumors, while NPS at 180 mJ/mm³ cleared 60-70%, indicating that higher energy levels are necessary to effectively eliminate B16f10 tumors [

64].

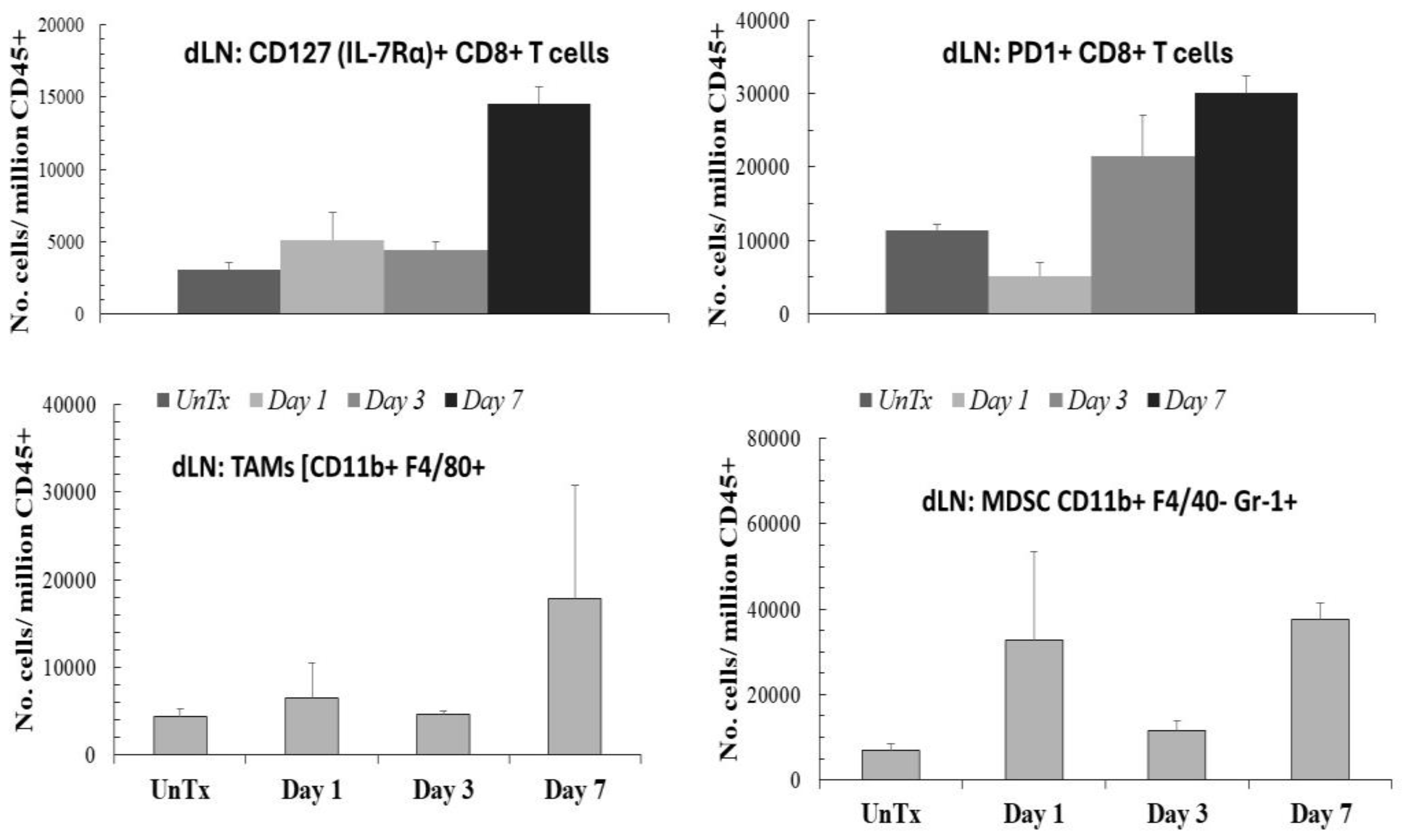

In immunity analyses (

Figure 2), one day after NPS treatment of B16f10 melanoma tumors, CD8+ T-cells expressing CD127 (IL-7Rα+) increased threefold in the TME and 1.4-fold in the draining lymph nodes (dLNs), totaling about 15,000 cells. High CD127 expression is generally associated with activated memory T cells [

65,

66]. IL-7 is a crucial cytokine for T cell development, proliferation, and the maintenance of memory T cells [

67]. However, there are nearly 30,000 cells expressing programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1+) among the CD8+ T-cells in the dLNs. CD8+ cells expressing PD1+ are exhausted or anergic cytotoxic T-cells resulting from chronic stimulation in cases of cancer or chronic infection [

67]. TAMs {CD11b F4/80+} and MDSCs [CD11b+ F480- Gr-1+] in the dLNs increased significantly to nearly 20,000 and 30,000 cells, respectively, by day 7. Additionally, these MDSCs expressed activation co-molecules MHCII and CD80 (not shown). Therefore, in the presence of immunosuppressive TAMs, activated MDSCs, and PD1+ exhausted T-cells, the memory (CD127+) T-cells are unlikely to induce immunity. (

Figure 2).

Further investigation of the dLN of NPS B16f10 melanoma tumors revealed a significant presence of CD4+ CD25+ Tregs that also expressed CD127. As expected for Tregs in tumor models, these cells were notably abundant in untreated mice. In functional suppression assays, CD127 Tregs proved to be highly suppressive. One day after NPS, CD127 Tregs decreased by about one third but increased 1.5 times by day 7. The substantial presence of highly immunosuppressive Tregs, along with TAMs and activated MDSCs, created a strongly immunosuppressive environment where immunity would not be expected.

A previous study reported that NPS stimulated an immune response in UV-induced murine melanoma, based on the observation that a second tumor (challenge) grew more slowly in mice whose primary tumor had been ablated by NPS. The only immune analysis as evidence for immunity was the presence of CD4+ T-cells in treated tumors and in non-treated tumors in mice whose primary tumor was ablated [

68].

6. Conclusions

Hallmarks of immunity [

28] and ISV vaccination were observed in orthotopic models of N1-S1 rat liver cancer [

19] and 4T1-luc mouse breast cancer [

25,

26,

27], but not in ectopic models of mouse Pan02 pancreatic cancer [

60] or in mouse B16f10 melanoma [

64]. The immune response in orthotopic tumor models has the advantage of recognizing danger signals (DAMPs) [

25] within the correct organ context [adjuctivity] and replicating the appropriate vasculature, enabling the natural interaction of tumor cells with host stromal cells (permissive TME) [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73], which recruit and activate innate and tissue-specific immune cells as tumors release antigens into natural lymphatic routes (antigenicity) [

25,

27,

63].

A key difference in inducing immunity between orthotopic and ectopic models is that tumor cells in the TME of the ISV model are implanted in their natural tissue (orthotopic), closely resembling the native tissue environment [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74]. In this setting, tumor cells are surrounded by their natural microenvironment, which can influence NPS-induced effects such as natural RCD mechanisms with ICD credentials. Orthotopic tumors develop within the correct microenvironment that includes natural stroma, ECM, and cytokine signals. This setup allows interactions between stromal and endothelial cells that regulate immune infiltration and activation. In contrast, ectopic tumors lack a normal microenvironment. Orthotopic models drain into physiological lymph nodes, enabling antigen recognition, presentation, and adaptive immune responses [

71,

74]. This facilitates communication among stromal, endothelial, and resident immune cells in the natural orthotopic environment, providing signaling and cytokine cues that affect T-cell differentiation, priming, and memory [

71,

73]. Conversely, antigen drainage in ectopic models goes to abnormal lymph nodes (such as inguinal or axillary), which may not effectively prime systemic antitumor T-cell responses, leading to tolerance instead of immunity. Consequently, the immune system may not recognize tumor cells [

38,

59,

61,

63] or respond adequately to strong danger signals [

41].

Host and resident immune cell interactions in the natural orthotopic setting provide signaling and cytokine crosstalk [

69,

70,

71] that influence T-cell [

25,

27] and NK/NK-T cell [

19] differentiation and memory, which are absent in ectopic models [

38,

59,

61,

62]. The orthotopic interactions enable tumor growth patterns that closely resemble those observed in human cancer patients. Orthotopic models represent a more complex, yet more disease-relevant preclinical approach compared to ectopic models [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73].

Having tumor cells in their natural environment may allow more realistic interactions between NPS and the vascular and immune systems [

70,

72,

73,

74], potentially improving NPS effects. In contrast, in non-ISV models, tumor cells are injected subcutaneously into a foreign tissue site. These conditions do not mimic the natural interactions between the tumor and its surrounding environment, which can influence tumor growth, behavior, and response to NPS. Subcutaneous tumors have different vascular structures and blood supplies [

72,

73]. Additionally, ectopic models may fail to capture the complex interactions between cancer and the immune system [

68,

70,

74]. Under these conditions, ectopic tumor models might not reliably predict how NPS treatment will work in humans. Overall, these points suggest that ectopic cancer models are less translatable to the human condition than orthotopic models [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73].

In orthotopic sites, suppressive cells cannot flourish due to the disruption of supportive structures that create metabolically favorable niches in the TME (e.g., high lactate in mammary tumors, fatty acids in liver tumors). NPS disrupts the TME and metabolism in these areas, cutting off the fuel sources for suppressive cells. In ectopic sites, suppressive cells are less metabolically developed, so NPS may break down the TME structures [

39], but it does not have the same selective effects.

The most noticeable differences between the orthotopic and ectopic cancer models, based on immune cell characterizations, were the presence of cytotoxic T-cells in the TME and dLNs [

25,

27], or activated NK cells and NK-T cells in the liver [

19], and their absence in the ectopic models [

38,

59]. The TME’s mixture of Tregs, TAMs, and MDSCs influences immune outcomes [

73]. This is likely partly due to the poor development of cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells and/or their suppression by the persistent presence of immunosuppressive cells in a TME that seemed to resolve early after NPS but returned in the following days [

58,

62]. It is also probable that circulating monocytes re-enter the inflammatory TME and reprogram into immunosuppressor cells [

74,

75]. Additionally, the TME may not have been thoroughly disrupted by the NPS conditions in this unnatural environment. The B16f10 melanoma model showed that higher energy pulses were more effective at eliminating tumors than lower energy pulses, indicating that higher energy might be necessary in ectopic models.

Orthotopic models better mimic physiological immune suppression and activation as seen in patients [

69,

72,

73]. They eliminate the TME immunosuppression and replace it with an immunoactive environment [

19,

25,

26,

27]. In contrast, ectopic models' TME and associated immune tissues [

59,

63] retain immunosuppressive cells, creating an unnatural TME.

In short, orthotopic cancer models more accurately reflect the tissue environment and their natural origin. This allows for natural stroma and paracrine signaling; proper 3D structure and spatial organization; accurate vasculature and tumor perfusion; tissue-specific APC, lymph node drainage, and antigen transport; and a balanced immune response between suppression and activation. Ectopic models lack these features, failing to elicit significant immune responses and a meaningful translation of therapies to human cancers.

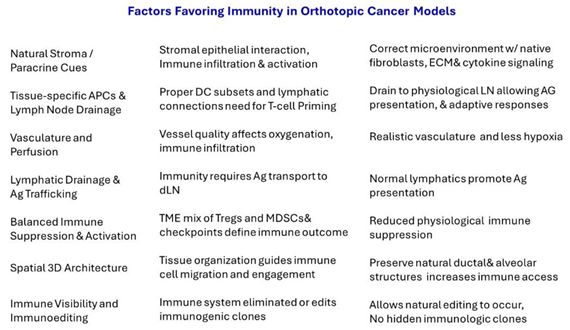

Table 1 shows an overview of advantages offered in orthotopic cancer models