1. Introduction

The central problem of modern oncology is to find treatments that can selectively destroy cancer cells effectively, without causing significant damage to non-targeted tissues. Conventional modalities like chemotherapy and radiotherapy, while indispensable, are often constrained by systemic toxicity and the development of resistance. This has led to the exploration of novel approaches such as those that can target vital and unique characteristics of cancer cells. Perhaps the most promising frontier is the targeting of cancer’s distinctive bioelectrical signature, changing the therapeutic focus beyond strictly biochemical interactions into the cell’s underlying biophysics. It has been known for long that cancer cells possess a distinct bioelectrical signature that makes them distinct from normal cells [

1,

2]. This signature is a consequence of profound metabolic remodeling, including the Warburg effect, that produces a modified intracellular ionic balance and a more depolarized transmembrane potential [

3].

These biophysical alterations are not secondary effects of malignancy but are directly linked to the processes of uncontrolled growth, invasion, and immune evasion. This novel physical phase presents a physical and exploitable vulnerability, which has given rise to a novel class of physical energy-based treatments for selectively disrupting cancer cells. Our group recently characterized the effects of a novel technology, Multifrequency Electromagnetic Pulse (MEMP). This non-invasive and non-thermal treatment involves the delivery of extremely low frequency (<30 Hz) electromagnetic pulses at a high magnetic flux density (>2 T) [

4]. Our initial study demonstrated that MEMP possesses excellent specificity, inducing death in a panel of highly tumorigenic cell lines (such as glioblastoma, cervical, and colon carcinoma) quickly and selectively, with minimal damage to non-tumorigenic cells and primary macrophages.

In vitro, MEMP exposure selectively induced rapid cell death in a panel of tumorigenic cell lines while leaving non-tumorigenic cells unharmed. We identified the mechanism as a catastrophic collapse of the actin cytoskeleton, leading to a subsequent G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Furthermore, we established the safety of the procedure in healthy mice and provided initial evidence showing that a brief ex vivo MEMP treatment completely abrogated the ability of colon cancer cells to form tumors upon injection in mice.

Although these findings were very encouraging, the efficacy of MEMP in a real therapeutic setting, applicable in clinical practice, where the fields must penetrate a complex tumor microenvironment, remained a critical unanswered question. The objective of the present study was, therefore, to bridge this gap by evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of systemic MEMP treatment on established MC38 colon carcinomas in a syngeneic, immunocompetent mouse model. The use of an immunocompetent host is crucial, as it allows for the assessment not only of the direct cytotoxic effects of MEMP on the tumor but also of its potential to modulate and engage the host’s anti-tumor immune response, a key determinant of long-term therapeutic success in precision oncology.

2. Results

2.1. MEMP Effect on the Growth of MC38 Colon Adenocarcinoma Tumors

We have previously shown that MEMP can selectively affect tumor cells without affecting non-transformed cells in vitro, and mice subjected to MEMP remained healthy with no effect on the well-being, including biochemical parameters and blood counts [

4]. Thus, we here decided to apply MEMP to treat tumor-bearing mice. The MC38/C57BL6 syngeneic model, inoculating the colon cancer cells subcutaneously, was chosen. As shown in Fig. 1A, 600,000 MC38-Luc cells inoculated in the right flank of the mice could be monitored for bioluminescence (BLI) with an IVIS Spectrum system. One week after inoculation, tumors were barely palpable, and the mice were therefore separated into two groups with equivalent tumor load, based on BLI. MEMP treatment was initiated on this same day, and for this the mice were placed on the electromagnetic emitter, in a small methacrylate box, to limit movement outside the emitter’s focus (Fig. 1B). In this first regime, the MEMP treatment was applied for 15 minutes every other day for two weeks. The device was set to 80% intensity, a frequency of 30 Hz, and an electromagnetic field strength greater than 2 Tesla. Tumor growth was monitored once a week by BLI quantification (Fig. 1C). While the tumors of control mice grew at the expected rate, those of MEMP-treated mice showed a tendency to grow less (Fig. 1D). Notably in the case of two treated mice, an important regression of the tumors was observed, whereas, in general, control mice reached humane endpoint conditions earlier than the MEMP-treated ones (Fig 1E). These results indicate that MEMP treatment affected tumor growth, even causing the regression of some tumors.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of tumor progression of mice subjected to MEMP treatment. A. Regime scheme. B. Illustration of the MEMP device. C. C57BL/6 mice injected with mouse MC-38-Luc adenocarcinoma cells and expressing formed tumors were modulated at 7 days post injection. MEMP treatment was continued for two weeks until day 26 post-tumor. Representative IVIS images from day 5 until 26 days post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= e3-e6, Max= e6-e7) of controls and modulated mice. D. In vivo imaging quantification of tumor bioluminescence in mice. Data represent the mean with +/-SEM, and were statistically analysed using a Mixed-effects analysis with Sidak’s test. E. Survival analysis.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of tumor progression of mice subjected to MEMP treatment. A. Regime scheme. B. Illustration of the MEMP device. C. C57BL/6 mice injected with mouse MC-38-Luc adenocarcinoma cells and expressing formed tumors were modulated at 7 days post injection. MEMP treatment was continued for two weeks until day 26 post-tumor. Representative IVIS images from day 5 until 26 days post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= e3-e6, Max= e6-e7) of controls and modulated mice. D. In vivo imaging quantification of tumor bioluminescence in mice. Data represent the mean with +/-SEM, and were statistically analysed using a Mixed-effects analysis with Sidak’s test. E. Survival analysis.

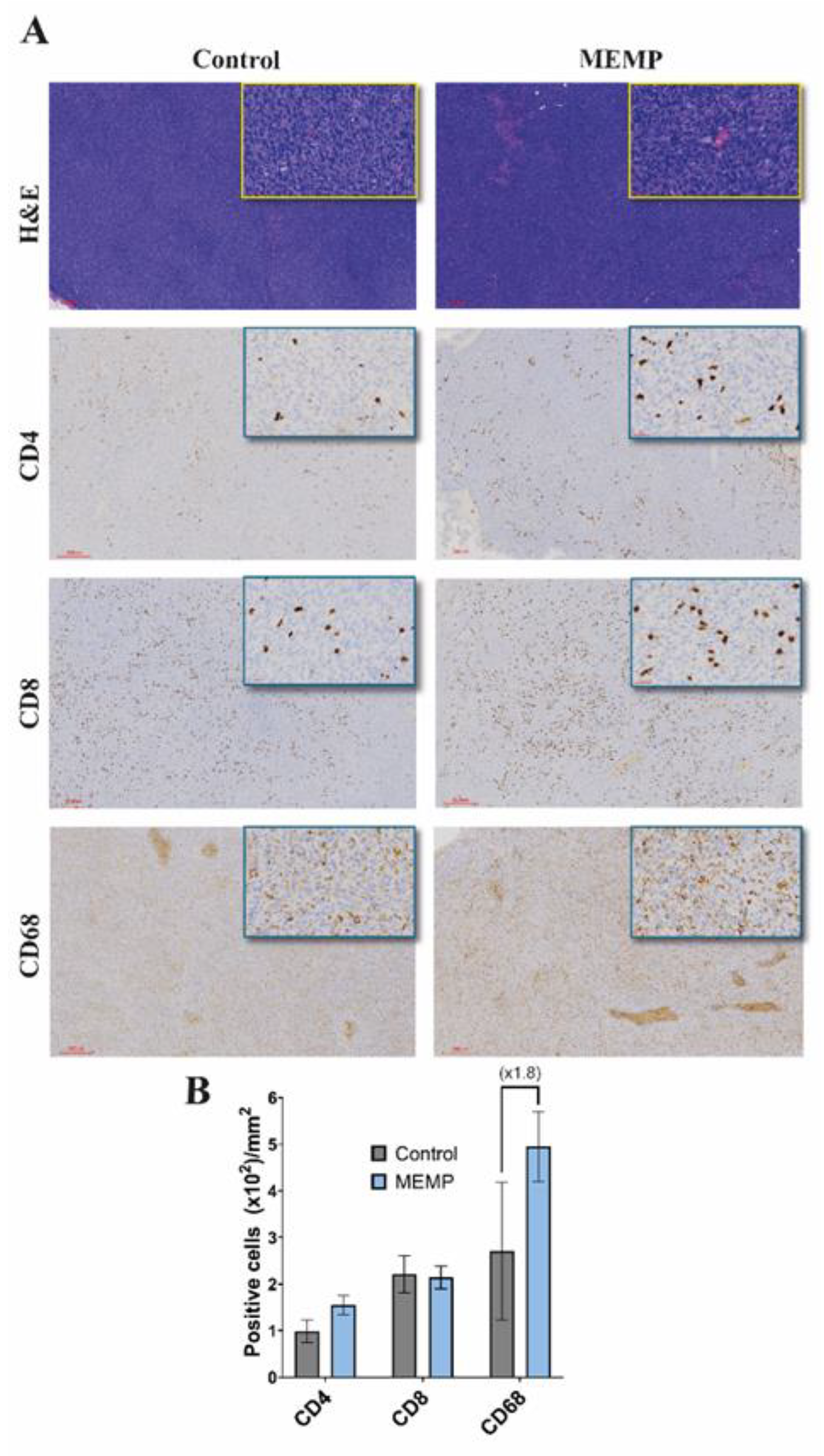

To investigate a possible interference of the MEMP with the anti-tumor immune response, after animal sacrifice, tumors were extracted and processed for histology and IHC. H&E staining of tumors showed compact tumors with high cellularity, observing more necrotic areas in the MEMP-treated tumors (Fig. 2A), without other notable differences between groups, as for example in vascularization. Staining for immune cell populations showed that tumors were infiltrated by immune cells, showing similar numbers of CD4 and CD8 T cells in control and modulated tumors, but with more than two-fold increase in the number of CD68 positive macrophages (Fig. 2B). In this later case, it must be further noted that the MEMP-treated mice tumors showed stronger CD68 staining. As all IHC staining and DAB development were performed by an automated system (Dako Autostainer Link 48), intensity differences may be considered reliable.

Figure 2.

Immune marker in control and modulated explanted tumors. Animals were sacrificed and tumors were extracted and processed for histology and IHC (A). Upper, HE staining. Lower, immune markers. (B) Scored numbers of the respective immune marker represented as the mean with +/-SEM per area of the tumors.

Figure 2.

Immune marker in control and modulated explanted tumors. Animals were sacrificed and tumors were extracted and processed for histology and IHC (A). Upper, HE staining. Lower, immune markers. (B) Scored numbers of the respective immune marker represented as the mean with +/-SEM per area of the tumors.

2.2. MEMP and Immune System: Impact and Protection Against Re-Inoculated Tumors

The two mice with tumor regression were monitored after the end of the MEMP treatment for tumor relapses for 60 days and subjected to blood tests (Supplementary figure 1 and 2). Since no tumor growth, by BLI or by normal exploration, was observed (Fig. 3A), mice were re-inoculated with 600,000 MC38-Luc cells, in this case, in the opposite flank, in parallel with naïve mice. As expected, tumors in naïve mice grew fast, reaching endpoint criteria in just 15 days (Fig. 3B-D). On the contrary, tumors in the MEMP-treated regressed mice grew much more slowly, indicating a potential vaccination effect.

Figure 3.

Protection against neo-tumor inoculation. Evaluation of tumor relapse in mice subjected to MEMP treatment. A. IVIS images of tumor bioluminescence at day 50 and day 60 post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= 9.09e3, Max= 1.18e5) of two modulated mice that showed reduction of tumor growth from day 5 to 26. B. Evaluation of the MEMP treatment on protection against the growth of implanted homologous tumor. C57BL/6 mice injected with mouse MC-38-Luc adenocarcinoma cells and tumors progression evaluated at 7- and 16-days post injection. IVIS images of tumor bioluminescence at day 7 and day 16 post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= 2.33e5, Max= 1.75e7) of previously modulated mice that have remitted tumors versus controls mice not subjected to MEMP treatment. C-D. Tumors size evaluation after explants.

Figure 3.

Protection against neo-tumor inoculation. Evaluation of tumor relapse in mice subjected to MEMP treatment. A. IVIS images of tumor bioluminescence at day 50 and day 60 post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= 9.09e3, Max= 1.18e5) of two modulated mice that showed reduction of tumor growth from day 5 to 26. B. Evaluation of the MEMP treatment on protection against the growth of implanted homologous tumor. C57BL/6 mice injected with mouse MC-38-Luc adenocarcinoma cells and tumors progression evaluated at 7- and 16-days post injection. IVIS images of tumor bioluminescence at day 7 and day 16 post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= 2.33e5, Max= 1.75e7) of previously modulated mice that have remitted tumors versus controls mice not subjected to MEMP treatment. C-D. Tumors size evaluation after explants.

2.3. Enhancement of Anti-Tumor Effect by Higher MEMP Regime

We then sought to further explore if the protocol of MEMP treatment could be improved so as to have a stronger effect against the tumors. Therefore, in a second experiment, we decided to apply a treatment regimen that involved daily 15-minute MEMP sessions, at 95% potency, administered for five consecutive days, followed by a two-day rest period, and then a second five-day block of treatment (Fig 4A). In this case, to avoid excessive early tumor growth that could overwhelm the immune system, we inoculated 600,000 cells, and we started MEMP treatment earlier, 3 days post-inoculation. Tumor growth was monitored by BLI twice per week. As can be seen in figure 4B-D, control tumors grew faster than the MEMP-treated ones, reaching a significant difference, both in comparing individual day values as well as the areas under the curve. Interestingly, all MEMP-treated mice managed to reach the 30-day experiment end without reaching humane endpoint conditions (fig. 4E), in contrast to the control mice that had to be sacrificed at day 20 or before (average humane endpoint for C57BL/6 mice inoculated with MC38Luc cells at the Preclinical Biomedicine Service, CBM, is 21 days, n = 84, various independent experiments).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of tumor progression of mice subjected to higher regime of MEMP. C57BL/6 mice injected with mouse MC-38-Luc adenocarcinoma cells and modulated at 72h post injection. MEMP treatment was continued until day 20 of tumor (2 weeks of treatment). A. Regime scheme. B. IVIS images of tumor bioluminescence from day 7 to day 20 post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= from e4 to e6, Max= from e5 to e7) of modulated and controls mice. C. In vivo imaging quantification of tumor bioluminescence from day 3 until day 20 of tumor progression. Data represent the mean with +/-SEM, and were statistically analysed using a Mixed-effects analysis with Sidak’s test. D. Survival analysis.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of tumor progression of mice subjected to higher regime of MEMP. C57BL/6 mice injected with mouse MC-38-Luc adenocarcinoma cells and modulated at 72h post injection. MEMP treatment was continued until day 20 of tumor (2 weeks of treatment). A. Regime scheme. B. IVIS images of tumor bioluminescence from day 7 to day 20 post-inoculation (radiance p/sec/cm2/sr color scale Min= from e4 to e6, Max= from e5 to e7) of modulated and controls mice. C. In vivo imaging quantification of tumor bioluminescence from day 3 until day 20 of tumor progression. Data represent the mean with +/-SEM, and were statistically analysed using a Mixed-effects analysis with Sidak’s test. D. Survival analysis.

2.4. Analysis of the Impact of High MEMP Regime on the Immune Response

Histology of the extracted tumors showed similar characteristics to those in the previous experiment, with the MEMP-treated ones containing more necrotic areas (fig. 5A). In consistency with above, in this experiment as well the numbers of CD4 and CD8 positive T cells remained similar between the control and MEMP-treated tumors (fig. 5B, and supplementary table 1). However, the numbers of tumor-associated macrophages (CD68 staining) showed again close to a two-fold relative increase in MEMP-treated tumors (Fig. 5B), which was consistently supported by a stronger CD68 staining. These results suggest a robust macrophage-mediated immune response against the tumor cells in the MEMP-treated mice.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry evaluation of T cells infiltration in explanted tumors. Mice were sacrificed 26 days post injection, and tumors were explanted, fixed and analysed by immunohistochemistry. A. Tissues evaluated for CD8, CD4 and CD68 markers expression by specific immune staining. B. Scored numbers of the respective immune marker represented as the mean with +/-SEM per area of the tumors.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry evaluation of T cells infiltration in explanted tumors. Mice were sacrificed 26 days post injection, and tumors were explanted, fixed and analysed by immunohistochemistry. A. Tissues evaluated for CD8, CD4 and CD68 markers expression by specific immune staining. B. Scored numbers of the respective immune marker represented as the mean with +/-SEM per area of the tumors.

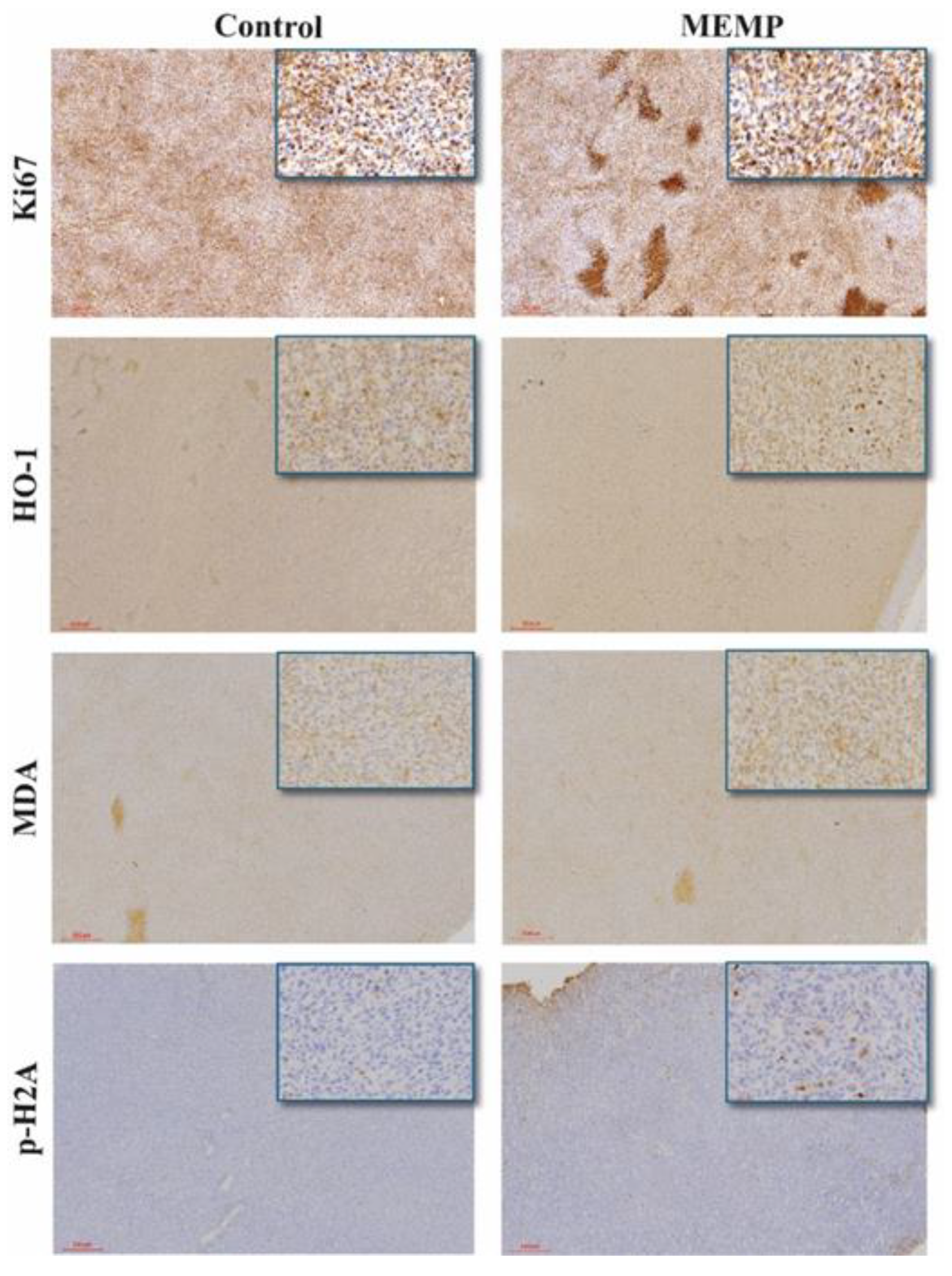

2.5. Study of MEMP Effect on Tumor Cell Proliferation and Oxidative Stress

To further characterize MEMP effect on tumors, we tested cell proliferation byKi67 staining. This antibody produced both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining, also marking intensely the necrotic areas. No differences could be observed between control and MEMP-treated tumors on Ki67 nuclear staining (fig. 6). On the other hand, numerous necrotic areas could be observed, showing an apparently bigger difference between the control and the MEMP-treated tumors than the one observed with H&E.

To further investigate the possible consequences of MEMP treatment on tumor cells, we performed oxidative stress-related staining, using Heme Oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and malondialdehyde-protein adduct (MDA) antibodies. As shown in

Figure 6, both control and MEMP tumors show a generalized basal expression of HO-1, with a limited number of cells with a stronger staining. The amount of strong positive cells and intensity of their staining was apparently higher in the MEMP-treated tumors, suggesting a MEMP-derived effect. In the case of MDA, as expected, tumors show a positive, diffuse staining, with a tendency for the MEMP-treated ones to have higher intensity. These results indicate that MEMP treatment may have caused, directly or indirectly, an increase in oxidative stress, still detectable in some cells 4 days after the last treatment.

Finally, to test if the mentioned oxidative stress had some physiological consequences, we tested if DNA damage could be detected as an effect of the MEMP treatment itself or of the resulting oxidative stress. Anti-phospho Histone 2A staining showed rare positive events in control tumors, while frequent positive cells were observed in the MEMP-treated ones, reaching approximately 1% of the cell numbers (Fig. 6). This would indicate that some of the cells suffered severe DNA damage, probably as a consequence of the oxidative stress. On the other hand, this result confirms that MEMP itself does not induce generalized genotoxic stress, but it does affect tumor physiology and growth.

3. Discussion

3.1. MEMP as Non-Invasive Anti-Tumor Physical Therapy

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that systemic, non-invasive MEMP therapy can significantly inhibit the growth of established solid tumors in an immunocompetent host, increasing the overall survival of the mice treated. Our results show that MEMP treatment not only slows the progression of MC38 colon carcinomas but can induce complete tumor regression in a subset of animals, leading to improved survival. This therapeutic effect was achieved with no observable adverse effects, confirming the excellent safety profile reported previously.

3.2. MEMP in Immune Activation and Related Mechanisms

It is remarkable that MEMP treatment does not induce side effects in mice or perturb the quantitative penetration of immune effectors cells into tumors, allowing a robust and durable anti-tumor immune response. Our findings indicate that MEMP treatment antitumor action could involve a combination of direct tumor cell damage associated with oxidative injury together with a remarkable anti-tumor immune response.

The anti-tumor effect of MEMP appears to be mediated directly by the induction of intense cellular stress rather than by the cytostatic mechanisms observed

in vitro. While our previous work showed a clear G2/M arrest [

4], our current in vivo data revealed no significant change in the proliferation marker Ki67. Instead, we observed a marked increase in tumor necrosis, accompanied by clear evidence of elevated oxidative stress (HO-1 and MDA staining) and a corresponding increase in DNA damage (phospho-Histone 2A) in a subset of cells. This suggests that in the complex

in vivo environment, MEMP pushes cancer cells past a repairable checkpoint and into a state of irreparable damage, leading to necrotic cell death. This finding aligns with other studies showing that low-frequency magnetic fields can induce apoptosis via reactive oxygen species [

7,

8]. The MEMP-induced physical perturbation, possibly initiated by the cytoskeletal collapse seen

in vitro, likely triggers a cascade of oxidative stress and cell death

in vivo, as it has been shown in other studies using technologies of similar concept [

9,

10].

During the intensified treatment regimen, which yielded superior tumor control, we found infiltration of CD4

+ and CD8

+ cytotoxic T cells into the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 5). The immune activation was however consistent for the CD68 marker, with two-fold increase in the two independent experiments performed at different MEMP regimes (Fig. 2 and 5). Furthermore, the CD68+ macrophages consistently showed stronger staining intensity in treated tumors, suggesting a change in their activation state, possibly a shift toward an M1, pro-inflammatory, phagocytic phenotype, as shown elsewhere [

11,

12]. This profile is highly indicative of immunogenic cell death (ICD), a process where dying cancer cells release signals that attract and activate an adaptive immune response [

13]. We hypothesize that the MEMP-induced necrosis and oxidative stress lead to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which serve to recruit and activate macrophages capable of recognizing and eliminating cancer cells, contributing to the oxidative environment too.

The differences between the two experiments can be explained by the complexity of the tumor-immune system interplay and the MEMP application protocol. While in the first one with more cells injected, treatment started only when tumors were palpable in most animals, in the second, fewer cells were inoculated and treatment started earlier, to avoid the tumor overwhelming the immune system. As expected, bigger differences in the growth curves of control and MEMP-treated tumors were observed in the second experiment. The tumor regression in 20% of the MEMP-treated mice of the first experiment was surprising and probably MEMP treatment-dependent, since we have never observed rejection of MC38 cell-derived tumors injected subcutaneously, after at least 100 C57BL/6 mouse inoculations for other experiments (source: Preclinical Biomedicine Service, CBM). We could observe BLI in the first week after inoculation, indicating that enough cells were injected and survived the first critical days. The preclinical evaluation of immunotherapies is a complex effort, where seemingly minor changes in experimental parameters, such as tumor cell inoculum size, can lead to profoundly different or even contradictory results. We hypothesize that the higher amount of infiltrating macrophages in the second experiment, probably functioning as tumor-protecting M2 macrophages, may have avoided the rejection of the cells, even if the MEMP treatment eventually activated them towards an M1 phenotype, elevating CD68 expression.

3.3. MEMP and Immune Memory

The generation of a durable, systemic anti-tumor immunity was unequivocally demonstrated by our re-challenge experiment. Mice that had previously rejected their tumors following MEMP therapy were protected from a subsequent inoculation of the same cancer cells, while tumors grew rapidly in naïve animals. This demonstrates the establishment of immunological memory, effectively functioning as an in situ cancer vaccine. The initial MEMP treatment did not just destroy the primary tumor; it educated the host’s immune system to recognize and remember the tumor antigens, enabling a swift and effective response against future encounters. This has profound clinical implications, suggesting that MEMP could not only treat primary tumors but also provide long-term protection against local and metastatic relapses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells

MC-38-Luc cells, derived from MC-38 cell line (SCC172, Sigma-Aldrich) as mentioned in Piredda et., al 2024, were cultivated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.4 mM non-essential amino acids,100 U/mL gentamicin, and 10% fetal calf serum (FBS; Invitrogen Life Technologies). Cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% of CO2 in a humidified air (95%).

4.2. Allografts Cancer Model

All animal care procedures used in this study were carried out following ARRIVE (

https://arriveguidelines.org/) guidelines. All animal procedures were performed in strict accordance with the European Commission legislation for the protection of animal use purposes (2010/63/EU). The protocol for the treatment of the animals was approved by the local government Ethics committee (Comité de Ética de la Dirección General del Medio Ambiente de la Comunidad de Madrid, Spain, PROEX 217.4/23) and was supervised by the Ethics Committee of the UAM (Madrid, Spain). Mice were purchased from Janvier Labs, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France. Mice were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle in a specific pathogen-free facility with controlled temperature and humidity (20–24 °C, 45–65 % humidity) and allowed access to food and water ad libitum. 12-week-old female immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice (initial weight 18–22 g), were injected subcutaneously in the right flank with 0.6x10

6 colon mouse adenocarcinoma cells (MC-38-Luc). In vivo tumor cell bioluminescence was monitored and quantified using the IVIS Spectrum System (PerkinElmer) after IP injection of D-Luciferin (150 mg/kg), with the mice anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation (4% induction, 2% maintenance of anesthesia). Body weight and general physical status were recorded daily, and the mice were sacrificed by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation at the end of every experiment or when reaching the endpoint criteria.

4.3. Molecular Modulation

The biomodulation device used in this study is an instrument developed by Paso Alto Biotechnology Inc. (USA). The system consists of two main components: a low-frequency electromagnetic radiation generator, configured to operate under constant parameters, and a high-power hardware module. For Multifrequency Electromagnetic Pulse (MEMP) treatment, mice were exposed to an electromagnetic field of non-ionizing frequency (f < 30 Hz) and high intensity (B > 2 T). The exposure was performed strictly following current ethical and regulatory standards for biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) laboratories and animal wellbeing. Each animal was individually placed in a 3x5x3 cm methacrylate container designed to restrict its movement without the need for anesthesia or further restraint devices, located directly above the emitter platform. The pulsed electromagnetic modulation treatment was applied for 15 minutes. MEMP treatment was carried out, in a first experiment, 7 days after inoculation of the tumor cells with the presence of preformed tumors, and subjecting mice to modulation on alternate days continuing the treatment for 2 weeks and modulating at a maximum power of 80%. In a second experiment, MEMP treatment was started 72 hours after cell inoculation and for five consecutive days, followed by a two-day rest period, and then a second five-day block of treatment with a maximum power of 95%.

4.4. Blood Analysis

Blood sampling from mice was performed from the submandibular vein using a small scalpel, and the sample was collected in Eppendorf tubes. Samples were analyzed by Element HT5 hematology system (Scilvet Company) that combine a laser flow cytofluorimetry for the accurate identification of neutrophilic granulocytes, lymphocytes, and exosinophilic and basophilic monocytes, an electrical impedance method for the detection of red blood cells and platelets, and a colorimetric method for the detection of HGBs.

4.5. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (3 µm) of paraffin-embedded tissues were hydrated prior to antigen retrieval in Dako Target Retrieval Solution, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides in Peroxidase-blocking solution (Dako) for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were incubated with 1% BSA-PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature before primary antibody incubation. Primary antibodies, against CD4 (1:500, Abcam ab183685), CD8 (1:2000, Abcam ab209775), CD68 (1ug/ml, Abcam ab125212), CD36 (1:150, Abcam ab252923), CD163 (1:500, Abcam ab182422 ), CD31-PECAM-1 (1:100,Santa Cruz sc-1506), PCNA (1:10000, Cell Signaling 2586S), Anti HO-1 (1:100, Merk SAB5700731), Malondialdehyde 11E3 (1:250, Novus NBP2-59367) and Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) (1:500, Cell Signaling 9718) were incubated overnight at 4°C. EnVision+ Dual Link secondary antibody (Dako) and DAB (Dako) solution were used for immunohistochemistry visualization. All histology and IHC stainings and DAB development were performed by an automated system (Dako Autostainer Link 48). Finally, sections were dehydrated and mounted with mounting media (Dako).

4.6. Quantitative Determination of Immune Cells Infiltration Into Tumors

Images obtained from the staining of the tumors with the CD8, CD4 and CD68 were processed using a custom ImageJ macro [

5]. Preprocessing included background subtraction followed by color deconvolution to separate H&E and DAB stainings [

6]. Tumor regions were segmented, and positive cells were subsequently quantified using ImageJ’s measurement tools on the DAB channel.

5. Conclusions

This study elevates MEMP therapy from a promising in vitro tool to a validated in vivo therapeutic modality. Its implementation allows a robust activation of the immune system against the tumor, mainly driven by CD68+ macrophages infiltration, culminating in long-term immunological memory. These features, combined with its non-invasive nature and excellent safety profile, positions MEMP as a powerful new platform in oncology. Further experimentation is necessary to optimize MEMP treatment protocol for maximal antitumor effect and to profoundly study the mechanisms of action of this treatment. Future studies should also focus on combining MEMP with already established immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, where its ability to induce T-cell infiltration could create a powerful synergistic effect, and may overcome the resistance to these inhibitors already observed in several tumors. The potential of MEMP to serve as a safe, repeatable, and systemic in situ vaccine represents a significant advance in the pursuit of non-invasive and effective cancer treatments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Blood analysis of previously MEMP treated and remitted tumor mouse 1-0. Figure S2: Blood analysis of previously MEMP treated and remitted tumor mouse 3-2. Table S1: Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for CD4, CD8, and CD68.

Author Contributions

R.P. and L.G.R.M. equally contributed to this work. The conception and design of the work, and manuscript writing, was performed by L.G.R.M, J.M.A., K.S. and Y.R. R.P., J.M.O., A.L.F, S.V.G, E.M.G, M. L.G.B. conducted different experiments and prepared all the figures. K.S. supervised and supported the mice experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This project has been funded by PASO ALTO ADVANCED TREATMENT CENTER LLC, USA and PASO ALTO BIOPHYSIC SL, Spain, and by the grant PID2022-141799OB-I00 /AEI (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación) to J.M.A. The Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa (CSIC-UAM) is in part supported by institutional grants from the Fundación Ramón Areces and Banco Santander.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the local government Ethics committee (Comité de Ética de la Dirección General del Medio Ambiente de la Comunidad de Madrid, Spain, PROEX 217.4/23) and was supervised by the Ethics Committee of the UAM (Madrid, Spain).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr David Pérez Pérez for his support, to Dr. Alberto Crespo Calderon, in memoriam, to Mr Fidel Valdés Rodríguez, CEO of Paso Alto Advanced Treatment Center and Mr. F. Rafael López Ferraz, President and CFO of Paso Alto Advanced Treatment Center and Paso Alto Biotechnology Inc. for their collaboration and contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests. The US company PASO ALTO BIOTECHNOLOGY INC has developed a new non-ionizing radiation technology that enables the sustained delivery of intense, time-controlled, multi-frequency electromagnetic pulses (MEMP). The technology is under industrial secrecy.

References

- Payne SL, Levin M, Oudin MJ. Bioelectric Control of Metastasis in Solid Tumors. Bioelectricity. 2019, 1, 114–30. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Brackenbury WJ. Membrane potential and cancer progression. Front Physiol. 2013, 4, 185. [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Panadero R, Lucantoni F, Gamero-Sandemetrio E, Cruz-Merino L de la, Álvaro T, Noguera R. The tumor microenvironment as an integrated framework to understand cancer biology. Cancer Lett. 2019, 461, 112–22. [CrossRef]

- Piredda R, Martínez LGR, Stamatakis K, Martinez-Ortega J, Ferráz AL, Almendral JM, et al. Assessment of molecular modulation by multifrequency electromagnetic pulses to preferably eradicate tumorigenic cells. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 30150. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 676–82. [CrossRef]

- Landini G, Martinelli G, Piccinini F. Colour deconvolution: stain unmixing in histological imaging. Bioinformatics. 2021, 37, 1485–7. [CrossRef]

- Barati M, Javidi MA, Darvishi B, Shariatpanahi SP, Mesbah Moosavi ZS, Ghadirian R, et al. Necroptosis triggered by ROS accumulation and Ca2+ overload, partly explains the inflammatory responses and anti-cancer effects associated with 1Hz, 100 mT ELF-MF in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021, 169, 84–98. [CrossRef]

- Kirson ED, Dbalý V, Tovaryš F, Vymazal J, Soustiel JF, Itzhaki A, et al. Alternating electric fields arrest cell proliferation in animal tumor models and human brain tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007, 104, 10152–7. [CrossRef]

- Sandberg M, Whitman W, Bissette R, Ross C, Tsivian M, Walker SJ. Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy Alters the Genomic Profile of Bladder Cancer Cell Line HT-1197. J Pers Med. 2025, 15, 143. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Xing X, Zhou J, Jiang H, Cen P, Jin C, et al. Therapeutic potential of tumor treating fields for malignant brain tumors. Cancer Rep. 2023, 6. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho TG, Lara P, Jorquera-Cordero C, Aragão CFS, de Santana Oliveira A, Garcia VB, et al. Inhibition of murine colorectal cancer metastasis by targeting M2-TAM through STAT3/NF-kB/AKT signaling using macrophage 1-derived extracellular vesicles loaded with oxaliplatin, retinoic acid, and Libidibia ferrea. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023, 168, 115663.

- Chistiakov DA, Killingsworth MC, Myasoedova VA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev Y V. CD68/macrosialin: not just a histochemical marker. Laboratory Investigation. 2017, 97, 4–13. [CrossRef]

- Ren J, Li L, Yu B, Xu E, Sun N, Li X, et al. Extracellular vesicles mediated proinflammatory macrophage phenotype induced by radiotherapy in cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022, 22, 88. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).