1. Introduction

Depressive disorder is a common mental health condition affecting millions of people globally. In the United States, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) reported that 21 million adults (8.3% of the US adult population) had at least one major depressive episode in 2021.1 Depressive disorder is a complex condition that develops from an interplay of multiple factors, such as biological mechanisms, psychological influences, and social determinants.2−4

In addition to individual-level determinants, there is evidence that risk for depressive disorder may include community-based factors such as socioeconomic and environmental exposures.5,6 Although treatment for mental health is generally considered effective, only about 23% of adults aged 18 y and older (approximately 59.2 million) received any mental health treatment, such as inpatient or outpatient care, prescription medication, or telehealth services.7 The most common type of treatment reported was prescription medication, used by 16.3% of adults (approximately 41.9 million), followed by telehealth services, used by 12.1% (approximately 31.3 million people), according to the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.7 Common reasons people reported not receiving mental health treatment included worrying about what others would think or say (43.9%), concerns about cost being too high (42.4%), not having enough time (41.0%), and not knowing how or where to get help (38.7%). Others reported being afraid that their information would not stay private (34.8%) or thought there would be negative consequences to receiving treatment, such as losing their job, home, or custody of children (33.5%). Others reported that health insurance would not cover enough of the costs (31.9%).7 Thus, there remains an urgent need to identify scalable and modifiable factors that impact depressive symptoms among adults beyond pharmacological treatment.

Diet has been shown to play an important role, impacting onset, severity, and progression of depression.8−10 In particular, fruit and vegetables, rich in essential vitamins, minerals, fiber, phytochemicals and antioxidants, have been associated with better mental health outcomes, including a lower risk of depression in epidemiologic studies.11−14 However, the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and depression may vary across population groups due to cultural factors, dietary behaviors, socioeconomic status, and genetic and environmental influences.15−18 Higher fruit and vegetable intake has been associated with better cognitive measures (memory (β = 0.031, 95%CI: 0.014-0.049), verbal fluency (β = 0.030, 95%CI: 0.004-0.056), and global cognition (β = 0.035, 95%CI: 0.015-0.055) in urban, but not rural adults, suggesting that area of residence may modify this relationship.19

Much of the existing literature has examined dietary influences on depressive disorders without accounting for potential geographic or environmental differences, such as urban versus rural residence, which may influence both dietary behavior and mental health outcomes.13,20,21 To our knowledge, no nationally representative epidemiologic study has examined whether the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and depression disorder differs by urban versus rural residence. To address this gap, this study aims to incorporate geographic areas of residents into the investigation of fruit and vegetable intake on mental health using nationally representative data.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

This cross-sectional study utilized data from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), an ongoing, nationally representative, health-related telephone survey conducted annually among non-institutionalized adults aged 18 y and older in the US. BRFSS collects self-reported data on a wide range of health topics, including chronic medical conditions, healthcare access, health behaviors, and use of preventative services. Data are collected via landline and cellular telephone interviews from randomly selected adults (one per household) across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Verbal informed consent is obtained from all participants prior to the interview.

Compared to other national datasets, BRFSS uses a complex sampling design and iterative proportional fitting (raking) weighting methods to adjust for nonresponse and demographic discrepancies, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, geographic region, telephone source, and homeownership status. These techniques produce both national and state-representative estimates, making BRFSS well-suited for population-level surveillance and subgroup analyses by demographics, region, and area of residence. BRFSS includes responses from over 400,000 adults annually and provides urban–rural classification variables and geographic indicators, enabling examination of spatial disparities in health outcomes. This level of detail supports investigation into whether associations, such as fruit and vegetable intake and depression, differ by urban versus rural residence, a distinction not possible with smaller-sample surveys. A more detailed description of the BRFSS sampling methodology is available elsewhere.22 The 2021 BRFSS is the most recent dataset that includes information on fruit and vegetable intake.

In the 2021 BRFSS, 241,694,953 individuals responded to the question on depressive disorder. After excluding missing and refused responses for confounding variables, the final analytic sample included 156,256,279 individuals. BRFSS data are available as a de-identified, publicly available dataset, and therefore, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval is not required. Reporting of our findings adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

2.2. Primary Exposure: Fruit and Vegetable Intake

Fruit and vegetable intake was assessed based on self-reported daily median frequency of intake. BRFSS respondents reported their intake as times per day, week, or month. The following questions were included: “Now think about the foods you ate or drank in the past month (the last 30 days), including meals and snacks. You can tell me times per day, times per week or times per month:

100% fruit (not including juices): Not including juices, how often did you eat fruit?

100% fruit juice (not including fruit-flavored drinks or juices with added sugar): Not including fruit-flavored drinks or fruit juices with added sugar, how often did you drink 100% fruit juice, such as apple or orange juice?

Dark green vegetables: How often did you eat a green leafy or lettuce salad, with or without other vegetables?

Fried potatoes: How often did you eat any kind of fried potatoes, including home fries, or hash browns?

Other potatoes: How often did you eat any other kind of potatoes, or sweet potatoes, such as baked, boiled, mashed potatoes, or potato salad?

Other vegetables: Not including lettuce salads and potatoes, how often did you eat other vegetables?”

Respondents provided a numerical answer along with a specified time frame. These responses were then standardized to a daily frequency. Frequency of total fruit intake was calculated by combining responses for both 100% fruit juice and fruit, while frequency of total vegetable intake included responses for fried potatoes, other kinds of potatoes, dark green vegetables, and other vegetables. A total vegetable group without fried potatoes was also calculated and included other kinds of potatoes, dark green vegetables, and other vegetables. BRFSS reported the median frequency of intake (times per day) instead of the mean due to the historically skewed distribution of the data. Participants who answered, “Don’t know/not sure,” “refused to answer,” or had missing responses were excluded from the analysis (n= 40,732,203). The median daily intake of fruit and vegetables was calculated by first converting weekly and monthly intake frequencies into daily values (by dividing weekly intake by 7 and monthly intake by 30) and then summing the frequency of all fruit and vegetable variables to determine total frequency of fruit and vegetable intake. The median frequency of total daily fruit and vegetable intake was calculated as a continuous variable and dichotomized as <1x/day (lower intake) or >1x/d (higher intake) More details can be found in the BRFSS Data User guide for fruit and vegetable questions: how to analyze consumption of fruit and vegetables.23

2.3. Primary Outcome: Self-Reported Depressive Disorder

Depression was assessed based on participants’ self-reported answers to the following: “(Ever told) (you had) a depressive disorder (including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression)?” (Yes/No).

2.4. Covariates

Covariates included age (y), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White (NHW), non-Hispanic Black (NHB), non-Hispanic other race (American Indian, Alaska Native only, Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander Race only, non-Hispanic Multiracial or Hispanic), household income (< $15,000, $15,000 to < $25,000, $25,000 to < $35,000, $35,000 to < $50,000, $50,000 to < $100,000, $100,000 to < $200,000, or ≥ $200,000), smoking (have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in entire life [Note: 5 packs = 100 cigarettes (Yes/No)], alcohol use (had at least one drink of alcohol in the past 30 d Yes/No), exercise (during the past month, other than regular job, participated in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise (Yes/No)), having health insurance (Yes/No), self-reported diabetes ((Yes), (Yes, but only during pregnancy), (No), (No, but borderline diabetes)), self-reported cardiovascular disease (CVD: heart attack, angina, coronary heart disease, or stroke), and urban-rural area of residence based upon 2013 NCHS Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Individuals who responded with “Don’t know/not sure,” “refused to answer,” or provided a missing response were excluded (n= 44,706,471). Marital status and adverse childhood experiences were considered as potential confounders, but were not retained in final models, as inclusion did not substantially impact results.

2.5. Statistical Methods

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software. All analyses were adjusted using survey weights, stratum, and cluster. Descriptive analyses were presented as percentages for categorical variables by rural or urban areas and differences between groups were determined using chi-square analyses. Multivariable logistic regression models examined associations between each fruit (reference group: >1x/day vs. <1x/day) and vegetable group (reference group: >1x/day vs. <1x/day) and self-reported depression adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, smoking, alcohol use, exercise, health insurance status, self-reported diabetes, and self-reported CVD. Interaction terms for each fruit and vegetable group and area of residence (categorized as urban or rural) for depression were examined in separate final models. A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding fried potatoes. Models with an interaction of P < 0.01 were stratified by area of residence.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Of the 156,256,279 participants available for analyses the majority were female (51.5% vs. 48.5% male), NHW (63.8% vs. 11.1% NHB vs. 16.1% Hispanic/Latino vs. 7.5% non-Hispanic another race vs. 1.5% non-Hispanic Multiracial). Of the participants, 124,046,746 (79.4%) reported not being diagnosed with a depressive disorder, while 32,209,533 (20.6%) reported a diagnosis of depressive disorder. Compared to urban counties, rural counties had a higher proportion of older adults and NHW participants (

Table 1). Rural residents were more likely to be male, NHW, older, lower income, smoke, report consuming fruit <1x/day, and self-report having diabetes (all

P < 0.001). Additionally, rural respondents were less likely to have health insurance, consume alcohol, exercise or self-report having CVD (all

P < 0.001).

3.2. Association of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption with Depressive Disorder

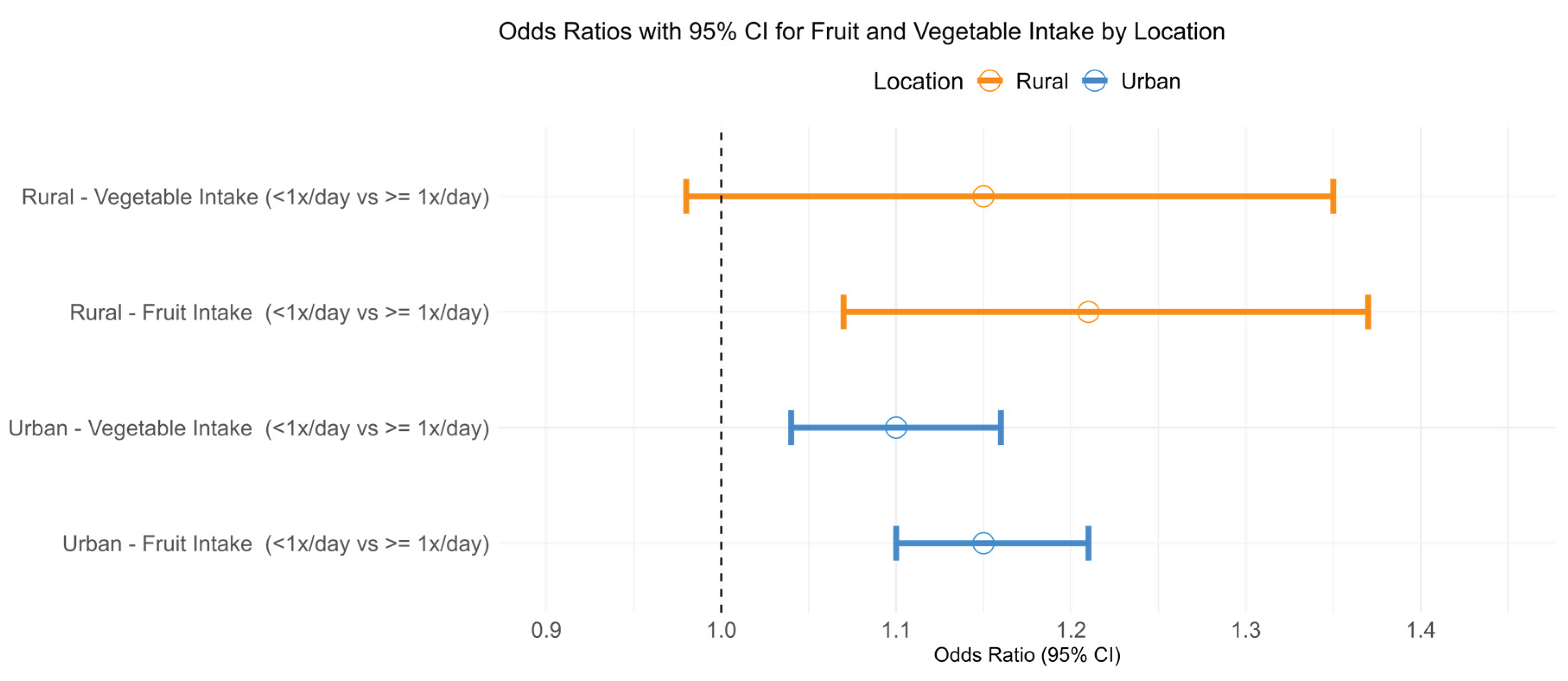

After adjusting for confounding variables, low fruit (<1x/d) and vegetables (<1x/d) consumption was associated with higher odds of depressive disorder compared with greater consumption (

>1x/day) (OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.12-1.22,

P <0.001 and OR = 1.10, 95%CI 1.04-1.16,

P <0.001, respectively) (Model 2,

Table 2). There were interactions between fruit intake and area of residence, and between vegetable intake and area of residence, in relation to self-reported depressive disorder (both interaction

P <0.001). In stratified analyses, low fruit intake was associated with higher odds of self-reported depressive disorder for participants living in urban and rural areas (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.10-1.21,

P <0.001 and OR = 1.21, 95%CI: 1.07-1.37,

P < 0.001, respectively). However, low vegetable intake was associated with higher likelihood of depressive disorder for participants living in urban areas only, but not rural areas (OR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.04-1.16,

P = 0.002 and OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 0.98-1.35,

P = 0.09, respectively) (

Figure 1). Sensitivity analyses, excluding fried potatoes from the total vegetable category, resulted in similar associations (

Supplemental Figure S1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings of This Study

This study found that lower fruit and vegetable intake was associated with higher odds of self-reported depressive disorder among U.S. adults, using a large, nationally representative sample from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Notably, this association differed by area of residence. Low fruit intake (<1x/day) was linked to higher odds of depression among both urban and rural residents, whereas low vegetable intake was associated with increased odds of depression only among urban residents. This study provides important findings on relationships between fruit and vegetable intake and depressive disorder between rural and urban areas, providing further support for the challenges faced by people living in different areas.

4.2. What Is Already Known on This Topic

In the total sample, low fruit and vegetable intake (<1x/day) was associated with higher odds of self-reported depressive disorder. This finding aligns with previous epidemiological research showing that fruit and vegetable consumption is an important aspect of dietary quality that should be considered in the prevention of poor mental health outcomes like depression disorder.14,24,25 Fruits and vegetables are rich in vitamins (e.g., folate, vitamin C), minerals, fiber, and phytochemicals with powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. These nutrients are likely to impact depression by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, supporting neurotransmitter synthesis, and promoting a healthy gut microbiome.26 Antioxidants reduce oxidative stress, which has been linked to neuronal damage and the pathophysiology of depression.27 Many fruits and vegetables contain anti-inflammatory compounds (e.g., polyphenols, carotenoids, magnesium) that reduce chronic low-grade inflammation, a state increasingly linked with depressive symptoms.28,29 Additionally, nutrients like folate and vitamin B6 are essential in neurotransmitter synthesis (e.g., serotonin, dopamine), which regulate mood.30 Dietary fiber also supports a healthy gut microbiome impacting mental health outcomes through the gut–brain axis.30 Collectively, these mechanistic pathways support our findings of protective associations between fruit and vegetables and depressive disorder, which remained after adjusting for sociodemographic and health-related confounders, underscoring the potential mental health benefits of higher fruit and vegetable intake. While a growing body of literature supports the protective role of diet in mental health, few studies have considered how these associations may vary by geographic factors such as urban versus rural residence.

4.3. What This Study Adds

Our findings extend current epidemiologic work to also include the potential impact of urban–rural differences on these associations. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale, nationally representative epidemiologic study to examine whether the association between fruit and vegetable intake and depressive disorder differs by urban–rural status in the U.S.

Rural participants in our study differed from their urban counterparts in several ways including that they were more likely to be older, NHW, male, have lower income, and to report poorer health behaviors (e.g., low fruit/vegetable intake, higher prevalence of smoking) and greater chronic disease burden (e.g., diabetes), while being less likely to engage in physical activity. Stratified analysis showed that low fruit intake was associated with higher odds of depression in both urban and rural residents, suggesting a link between low fruit consumption and poor mental health outcomes, regardless of geographic location.

In contrast, low vegetable intake was associated with depression only among urban participants, but not in those living in rural areas. This urban-specific association may reflect contextual differences in lifestyle behaviors and access to food. In urban communities, the increased cost of fresh vegetables often limits affordability for residents.31,32 Additionally, in urban neighborhoods, those with lower socioeconomic status tend to have less access to high-quality produce, especially vegetables, due to limited availability in local stores.32 Vegetables sold in corner and convenience stores are often of lower quality and less fresh compared to those found in larger supermarkets, which may influence both consumption and nutritional benefits.31 These factors collectively may contribute to the inverse association between vegetable intake and depression in urban areas. Rural populations also may have better access to home-grown or locally sourced produce, or stronger community ties that mitigate the mental health consequences of dietary inadequacies.33 In rural areas, other aspects of dietary quality such as higher intake of minimally processed foods or prepared home-cooked meal may be protective for mental health34 and may obscure the impact of vegetable consumption on depressive symptoms.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

The study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional design, which limits causal inferences between fruit and vegetable intake and depression disorder. The reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, such as inaccurate recall or social desirability bias, particularly with measures like fruit and vegetable consumption and depression disorder diagnosis. While the study adjusted for several covariates, there may be residual confounding present. Additionally, the interaction between rural and urban residence in relation to dietary intake and depression is complex, with weaker associations observed in rural areas, which warrants further exploration. Despite these limitations, the study offers important contributions to literature. To our knowledge, it is one of the first large-scale, population-based studies to examine whether the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and depression differs by urban versus rural residence. This study provides insight into potential environmental impacts on diet and mental health and lays the groundwork for future longitudinal or intervention-based research aimed at reducing risk of depression through dietary behavior change, particularly in communities with lower socioeconomic status. This study has several strengths including a large, diverse sample size of over 156 million participants to support power and generalizability across different demographic groups. The inclusion of both urban and rural populations allows for meaningful regional comparisons and offers valuable insights into how fruit and vegetable consumption may impact depression disorders differently in urban versus rural areas.

5. Conclusions

Differences in the relationship between vegetable intake on depression between urban and rural areas may be due to multiple factors such as cost, access to and quality of vegetables available across communities. While dietary quality is important for mental health, additional factors, such as lack of mental health resources and economic stress may contribute and require further investigation. Future research should further explore specific factors contributing to these regional differences to inform tailored interventions to address mental health disparities in both urban and rural settings.

Abbreviations

BRFSS: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CVD: Cardiovascular disease (heart attack, angina, coronary heart disease, or stroke); FV: Fruit and vegetable; IRB: Institutional Review Board; NHB: Non-Hispanic Black; NHW: Non-Hispanic White; NIMH: National Institute of Mental Health; STROBE: Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines

Author Contributions

The authors responsibilities were as follows - CND and SEN designed and guided the research and had primary responsibility for the final content; CND and TD conducted data analysis; CND and TL drafted the manuscript; TD, LF, and SEN: critically reviewed and contributed to the manuscript and literature review. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data described in the manuscript are publicly available from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website:

https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Major Depression - National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

- Remes O, Mendes JF, Templeton P. Biological, Psychological, and Social Determinants of Depression: A Review of Recent Literature. Brain Sci. 2021;11(12):1633. [CrossRef]

- Schotte CKW, Van Den Bossche B, De Doncker D, Claes S, Cosyns P. A biopsychosocial model as a guide for psychoeducation and treatment of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(5):312-324. [CrossRef]

- Zhou F, He S, Shuai J, Deng Z, Wang Q, Yan Y. Social determinants of health and gender differences in depression among adults: A cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2023;329:115548. [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride JB, Anglin DM, Colman I, et al. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry. 2024;23(1):58-90. [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Garshick E, Si F, et al. Environmental Toxicant Exposure and Depressive Symptoms. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2420259. [CrossRef]

-

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2023.

- Mrozek W, Socha J, Sidorowicz K, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of depression: Role of diet in prevention and therapy. Nutrition. 2023;115:112143. [CrossRef]

- Gianfredi V, Dinu M, Nucci D, et al. Association between dietary patterns and depression: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and intervention trials. Nutr Rev. 2023;81(3):346-359. [CrossRef]

- Marx W, Lane M, Hockey M, et al. Diet and depression: exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1):134-150. [CrossRef]

- Mihrshahi S, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-age women: results from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(5):585-591. [CrossRef]

- Mujcic R, Oswald AJ. Evolution of Well-Being and Happiness After Increases in Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1504-1510. [CrossRef]

- Brookie KL, Best GI, Conner TS. Intake of Raw Fruits and Vegetables Is Associated With Better Mental Health Than Intake of Processed Fruits and Vegetables. Front Psychol. 2018;9:487. [CrossRef]

- Saghafian F, Malmir H, Saneei P, Milajerdi A, Larijani B, Esmaillzadeh A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of depression: accumulative evidence from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. British journal of nutrition. 2018;119(10):1087-1101.

- Blissett J. Relationships between parenting style, feeding style and feeding practices and fruit and vegetable consumption in early childhood. Appetite. 2011;57(3):826-831. [CrossRef]

- Affret A, Severi G, Dow C, et al. Socio-economic factors associated with a healthy diet: results from the E3N study. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(9):1574-1583. [CrossRef]

- Huang P, O’Keeffe M, Elia C, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mental health across adolescence: evidence from a diverse urban British cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Matison AP, Thalamuthu A, Flood VM, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on fruit and vegetable consumption and depression in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):67. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves NG, Bertola L, Ferri CP, Suemoto CK. Rural-urban disparities in fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive performance in Brazil. Braz J Psychiatry. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, et al. Association of Western and Traditional Diets With Depression and Anxiety in Women. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):305-311. [CrossRef]

- Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, et al. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(7):965-986. [CrossRef]

- CDC - 2021 BRFSS Survey Data and Documentation.

- Data User’s Guide to the BRFSS Fruit and Vegetable Module | Nutrition | CDC.

- Lee M, Bradbury J, Yoxall J, Sargeant S. A longitudinal analysis of Australian women’s fruit and vegetable consumption and depressive symptoms. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2023;28(3):829-843. [CrossRef]

- Matison AP, Thalamuthu A, Flood VM, et al. Longitudinal associations between fruit and vegetable intakes and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults from four international twin cohorts. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):29711. [CrossRef]

- Fatahi S, Matin SS, Sohouli MH, et al. Association of dietary fiber and depression symptom: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2021;56:102621. [CrossRef]

- Ji N, Lei M, Chen Y, Tian S, Li C, Zhang B. How oxidative stress induces depression? ASN neuro. 2023;15:17590914231181037. [CrossRef]

- Belliveau R, Horton S, Hereford C, Ridpath L, Foster R, Boothe E. Pro-inflammatory diet and depressive symptoms in the healthcare setting. BMC psychiatry. 2022;22(1):125. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Pu H, Voss M. Overview of anti-inflammatory diets and their promising effects on non-communicable diseases. British Journal of Nutrition. 2024;132(7):898-918. [CrossRef]

- Bender A, Hagan KE, Kingston N. The association of folate and depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of psychiatric research. 2017;95:9-18. [CrossRef]

- Miller V, Yusuf S, Chow CK, et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. The lancet global health. 2016;4(10):e695-e703. [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Compte M, Burrola-Méndez S, Lozano-Marrufo A, et al. Urban poverty and nutrition challenges associated with accessibility to a healthy diet: a global systematic literature review. International journal for equity in health. 2021;20(1):40. [CrossRef]

- Saju S, Reddy SK, Bijjal S, Annapally SR. Farmer’s mental health and well-being: Qualitative findings on protective factors. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice. 2024;15(2):307. [CrossRef]

- Dicken SJ, Jassil FC, Brown A, et al. Ultraprocessed or minimally processed diets following healthy dietary guidelines on weight and cardiometabolic health: a randomized, crossover trial. Nature Medicine. 2025:1-12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).