Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Objectives and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

Case mix Adjustment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CoNS | Coagulase-negative Staphylococci |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trial |

| DFI | Diabetic foot infection |

| SSI | Surgical site infection |

| DAIR | Debridement, antibiotics and implant retention |

References

- Weinstein, M.A.; McCabe, J.P.; Cammisa, F.P. Postoperative Spinal Wound Infection: A Review of 2,391 Consecutive Index Procedures. J. Spinal. Disord. 2000, 13, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherpour, N.; Mehrabi, Y.; Seifi, A.; Eshrati, B.; Hashemi Nazari, S.S. Epidemiologic Characteristics of Orthopedic Surgical Site Infections and Under-Reporting Estimation of Registries Using Capture-Recapture Analysis. BMC. Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farshad, M.; Bauer, D.E.; Wechsler, C.; Gerber, C.; Aichmair, A. Risk Factors for Perioperative Morbidity in Spine Surgeries of Different Complexities: A Multivariate Analysis of 1,009 Consecutive Patients. Spine. J. 2018, 18, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Klemt, C.; Smith, E.J.; Tirumala, V.; Xiong, L.; Kwon, Y.-M. Outcomes and Risk Factors Associated With Failures of Debridement, Antibiotics, and Implant Retention in Patients With Acute Hematogenous Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 29, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.F.; Kim, K.; Cavadino, A.; Coleman, B.; Munro, J.T.; Young, S.W. Success Rates of Debridement, Antibiotics, and Implant Retention in 230 Infected Total Knee Arthroplasties: Implications for Classification of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J. Arthroplasty. 2021, 36, 305–310.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.J.; Ro, D.H.; Kim, T.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Han, H.-S.; Chang, C.B.; Kang, S.-B.; Lee, M.C. Worse Outcome of Debridement, Antibiotics, and Implant Retention in Acute Hematogenous Infections than in Postsurgical Infections after Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Multicenter Study. Knee. Surg. Relat. Res. 2022, 34, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernigou, P.; Scarlat, M.M. Implant removal in orthopaedic surgery: far more than a resident’s simple task. Int. Orthop. 2025, 49, 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuarin, L.; Abbas, M.; Harbarth, S.; Waibel, F.; Holy, D.; Burkhard, J.; Uçkay, I. Changing Perioperative Prophylaxis during Antibiotic Therapy and Iterative Debridement for Orthopedic Infections? PLoS. One. 2019, 14, e0226674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, S.; Faulhaber, S.; Hupp, M.; Uçkay, I. Selection of new pathogens during antibiotic treatment or prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopedic surgery, Euro. Soc. Medicine. 2024, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Uçkay, I.; Wirth, S.; Zörner, B.; Fucentese, S.; Wieser, K.; Schweizer, A.; Müller, D.; Zingg, P.; Farshad, M. Study Protocol: Short against Long Antibiotic Therapy for Infected Orthopedic Sites - the Randomized-Controlled SALATIO Trials. Trials. 2023, 24, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, M.; Uçkay, I.; Schüpbach, R.; Gröber, T.; Botter, S.M.; Burkhard, J.; Holy, D.; Achermann, Y.; Farshad, M. Short Postsurgical Antibiotic Therapy for Spinal Infections: Protocol of Prospective, Randomized, Unblinded, Noninferiority Trials (SASI Trials). Trials. 2020, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waibel, F.; Berli, M.; Catanzaro, S.; Sairanen, K.; Schöni, M.; Böni, T.; Burkhard, J.; Holy, D.; Huber, T.; Bertram, M.; et al. Optimization of the Antibiotic Management of Diabetic Foot Infections: Protocol for Two Randomized Controlled Trials. Trials. 2020, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brügger, J.; Saner, S.; Nötzli, H.P. A Treatment Pathway Variation for Chronic Prosthesis-Associated Infections. JBJS. Open. Access. 2020, 5, e20.00042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gümbel, D.; Matthes, G.; Napp, M.; Lange, J.; Hinz, P.; Spitzmüller, R.; Ekkernkamp, A. Current management of open fractures: results from an online survey Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2016, 136, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi YR, Kim BS, Kim YM, Park JY, Cho JH, Ahn JT, Kim HN. Second-look arthroscopic and magnetic resonance analysis after internal fixation of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendi, P.; Rohrbach, M.; Graber, P.; Frei, R.; Ochsner, P.E.; Zimmerli, W. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants in prosthetic joint infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, M.; Abrassart, S.; Vaudaux, P.; Gjika, E.; Schindler, M.; Billières, J.; Zenelaj, B.; Suvà, D.; Peter, R.; Uçkay, I. Increased Risk of Joint Failure in Hip Prostheses Infected with Staphylococcus Aureus Treated with Debridement, Antibiotics and Implant Retention Compared to Streptococcus. Int. Orthop. 2015, 39, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciola, C.R.; An, Y.H.; Campoccia, D.; Donati, M.E.; Montanaro, L. Etiology of Implant Orthopedic Infections: A Survey on 1027 Clinical Isolates. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2005, 28, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Loubet, P.; Salipante, F.; Laffont-Lozes, P.; Mazet, J.; Lavigne, J.P.; Cellier, N.; Sotto, A.; Larcher, R. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Enterococcal Bone and Joint Infections and Factors Associated with Treatment Failure over a 13-Year Period in a French Teaching Hospital. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün D, Trampuz A, Perka C, Renz N. High failure rates in treatment of streptococcal periprosthetic joint infection: results from a seven-year retrospective cohort study. Bone. Joint. J. 2017, 99-B, 653-659. [CrossRef]

- Achermann, Y.; Goldstein, E.J.; Coenye, T.; Shirtliff, M.E. Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 419–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansorge, A.; Betz, M.; Wetzel, O.; Burkhard, M.D.; Dichovski, I.; Farshad, M.; Uçkay, I. Perioperative Urinary Catheter Use and Association to (Gram-Negative) Surgical Site Infection after Spine Surgery. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2023, 15, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldevila-Boixader, L.; Murillo, O.; Waibel, F.W.A.; Schöni, M.; Aragón-Sánchez, J.; Gariani, K.; Lebowitz, D.; Ertuğrul, B.; Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, I. The increasing prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae as pathogens of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: A multicentre European cohort over two decades. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 154, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltoğlu, N.; Ergönül, Ö.; Tülek, N.; Yemisen, M.; Kadanalı, A.; Karagöz, G.; Batırel, A.; Ak, O.; Sönmezer, C.; Eraksoy, H.; et al. Influence of Multidrug Resistant Organisms on the Outcome of Diabetic Foot Infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 70, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.N.; Tluanpuii, V.; Trikha, V.; Sharma, V.; Farooque, K.; Mathur, P.; Mittal, S. Unraveling antibiotic susceptibility and bacterial landscapes in orthopedic infections at India’s apex trauma facility. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma. 2024, 57, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.; Tsang, S-TJ. ; Jansen van Rensburg, A.; Venter, R.; Epstein, G.Z. Unexpected high prevalence of Gram-negative pathogens in fracture-related infection: is it time to consider extended Gram-negative cover antibiotic prophylaxis in open fractures? SA. Orthop. J. 2023, 22, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jamei, O.; Gjoni, S.; Zenelaj, B.; Kressmann, B.; Belaieff, W.; Hannouche, D.; Uçkay, I. Which Orthopaedic Patients Are Infected with Gram-negative Non-fermenting Rods? J. Bone. Jt. Infect. 2017, 2, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçkay, I.; Bernard, L. Gram-negative versus gram-positive prosthetic joint infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Junyent, J.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Sorlí, L.; Murillo, O. Challenges and strategies in the treatment of periprosthetic joint infection caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: a narrative review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboltins, C.A.; Page, M.A.; Buising, K.L.; Jenney, A.W.J.; Daffy, J.R.; Choong, P.F.M.; Stanley, P.A. Treatment of Staphylococcal Prosthetic Joint Infections with Debridement, Prosthesis Retention and Oral Rifampicin and Fusidic Acid. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenke, Y.; Motojima, Y.; Ando, K.; Kosugi, K.; Hamada, D.; Okada, Y.; Sato, N.; Shinohara, D.; Suzuki, H.; Kawasaki, M.; Sakai, A. DAIR in treating chronic PJI after total knee arthroplasty using continuous local antibiotic perfusion therapy: a case series study. BMC. Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumenos, S.; Hardt, S.; Kontogeorgakos, V.; Trampuz, A.; Perka, C.; Meller, S. Success Rate After 2-Stage Spacer-Free Total Hip Arthroplasty Exchange and Risk Factors for Reinfection: A Prospective Cohort Study of 187 Patients. J. Arthroplasty. 2024, 39, 2600–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batailler, C.; Cance, N.; Lustig, S. Spacers in two-stage strategy for periprosthetic infection. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2025, 111, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Wong, T.M.; To, K.K.; Wong, S.S.; Lau, T.W.; Leung, F. Infection after fracture osteosynthesis - Part II. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong). 2017, 25, 2309499017692714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsemakers, W.J.; Kuehl, R.; Moriarty, T.F.; Richards, R.G.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; Borens, O.; Kates, S.; Morgenstern, M. Infection after fracture fixation: Current surgical and microbiological concepts. Injury. 2018, 49, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H. ; Sohn, H-S. Fracture-related infections: a comprehensive review of diagnosis and prevention. J. Musculoskelet. Trauma. 2025, 38, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, R.; Wirth, T.; Hahn, F.; Vögelin, E.; Sendi, P. Pyogenic Arthritis of the Fingers and the Wrist: Can We Shorten Antimicrobial Treatment Duration? Open. Forum. Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofx058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.S.; Carter, Y.M.; Marshall, M.B. Surgical Management of the Infected Sternoclavicular Joint. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2013, 18, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPaola, C.P.; Saravanja, D.D.; Boriani, L.; Zhang, H.; Boyd, M.C.; Kwon, B.K.; Paquette, S.J.; Dvorak, M.F.S.; Fisher, C.G.; Street, J.T. Postoperative Infection Treatment Score for the Spine (PITSS): Construction and Validation of a Predictive Model to Define Need for Single versus Multiple Irrigation and Debridement for Spinal Surgical Site Infection. Spine. J. 2012, 12, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billières, J.; Uçkay, I.; Faundez, A.; Douissard, J.; Kuczma, P.; Suvà, D.; Zingg, M.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Dominguez, D.E.; Racloz, G. Variables Associated with Remission in Spinal Surgical Site Infections. J. Spine. Surg. 2016, 2, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gram-Positive | 532 (49.8%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 202 (18.9%) | Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 174 (16.3%) |

| Methicillin sensitive | 184 | S. epidermidis | 128 |

| Methicillin resistant | 18 | S. lugdunensis | 18 |

| S. caprae | 15 | ||

| Cutibacterium spp. | 103 (9.7%) | S. hominis | 3 |

| S. saccharolyticus | 2 | ||

| Streptococcus spp | 34 (3.2%) | S. capitis | 2 |

| S. pneumoniae | 3 | S. simulans | 1 |

| S. dysgalactiae | 7 | S. pseudointermedius | 1 |

| S. agalactiae | 10 | S. warneri | 1 |

| S. bovis | 2 | S. haemolyticus | 3 |

| S. gordonii | 2 | ||

| S. anginosus | 2 | Enterococcus spp. | 9 (0.8%) |

| S. sanguis | 1 | E. faecalis | 8 |

| S. mitis | 5 | E. faecium | 1 |

| Other streptococci | 2 | Other Gram-positive | 10 (0.9%) |

| Gram-Negative | 103 (9.7%) | ||

| P. aeruginosa | 25 | ||

| Enterobacter sp. | 22 | ||

| Escherichia coli | 19 | ||

| Klebsiella sp. | 11 | ||

| Proteus sp. | 10 | ||

| Serratia marcescens | 7 | ||

| Citrobacter sp. | 2 | ||

| Other | 7 | ||

| Polymicrobial | 283 (26.5%) | ||

| Culture-Negative | 149 (14%) |

| Median Number of Surgical Interventions (ranges) | Risk for second looks | |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 2 (2-6) | 39/202 (19.3%) |

| CoNS | 2 (2-8) | 29/174 (16.7%) |

| Cutibacterium spp | 2 (2-4) | 12/103 (11.7%) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 2 (2-4) | 7/34 (20.6%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 2 (2-2) | 2/9 (22.2%) |

| Other Gram-Positive | 2 (2-2) | 2/10 (20%) |

| Gram-Negative | 2 (2-8) | 29/103 (28.2%) |

| Polymicrobial | 2 (2-5) | 60/283 (21.2%) |

| Culture-Negative | 2 (2-7) | 21/128 (14.1%) |

| Single Debridement | Multiple Procedures | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-Positive infections vs. Gram-Negative infections |

441/532 (82.9%) | 91/532 (17.1%) | |

| .001 | |||

| 74/103 (71.8%) | 29/103 (28.2%) | ||

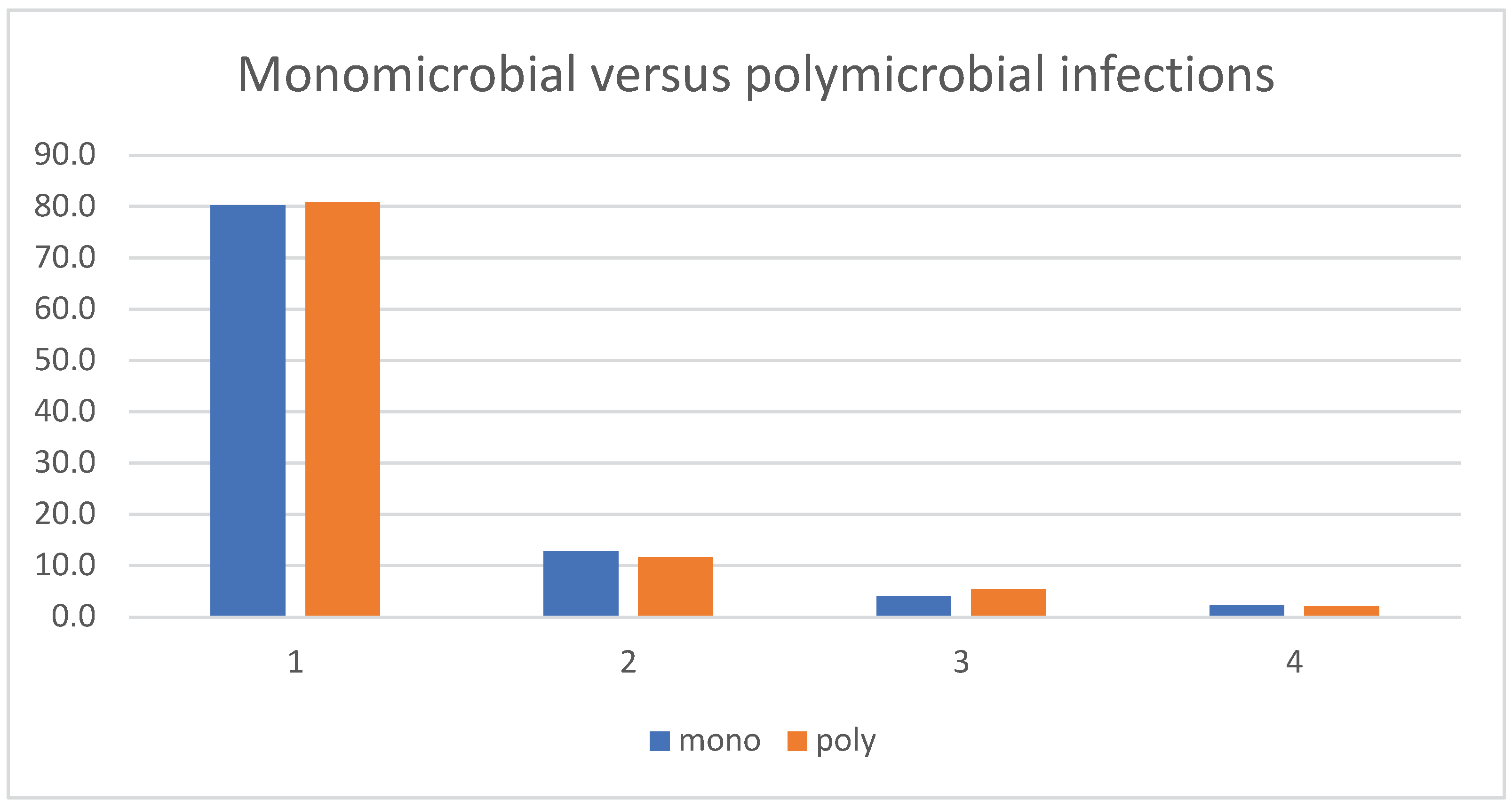

| Monomicrobial vs. Polymicrobial infections |

515/635 (81.1%) | 120/635 (18.9%) | |

| .42 | |||

| 223/283 (78.8%) | 60/283 (21.2%) | ||

|

S. aureus vs. CoNS |

163 /202 (80.7%) | 39/202 (19.3%) | |

| .51 | |||

| 145/ 174 (83.3%) | 29/174 (16.7%) | ||

|

S. aureus vs. Streptococcus spp. |

163 /202 (80.7%) | 39/202 (19.3%) | |

| .86 | |||

| 27/34 (79.4%) | 7/34 (20.6%) | ||

| Implant-related infections vs Native infections |

279/374 (74.6%) | 95/374 (25.4%) | |

| .00001 | |||

| 587/693 (84.7%) | 106/693 (15.3%) |

| Parameter | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implant-related infections | 2.18 | 1.56 - 3.03 | <.001 |

| Cutibacterium spp. | 0.57 | 0.29 - 1.14 | .113 |

| Gram-Negative | 2.04 | 1.20 - 3.47 | .009 |

| S. aureus | 1.38 | 0.86 - 2.20 | .18 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 1.22 | 0.50 - 2.99 | .662 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 1.25 | 0.25 - 6.28 | .79 |

| Polymicrobial | 1.73 | 1.13 - 2.65 | .012 |

| Other Gram-positive | 1.23 | 0.25 - 6.08 | .799 |

| Culture-Negative | 1.22 | 0.24 - 6.27 | .83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).