Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

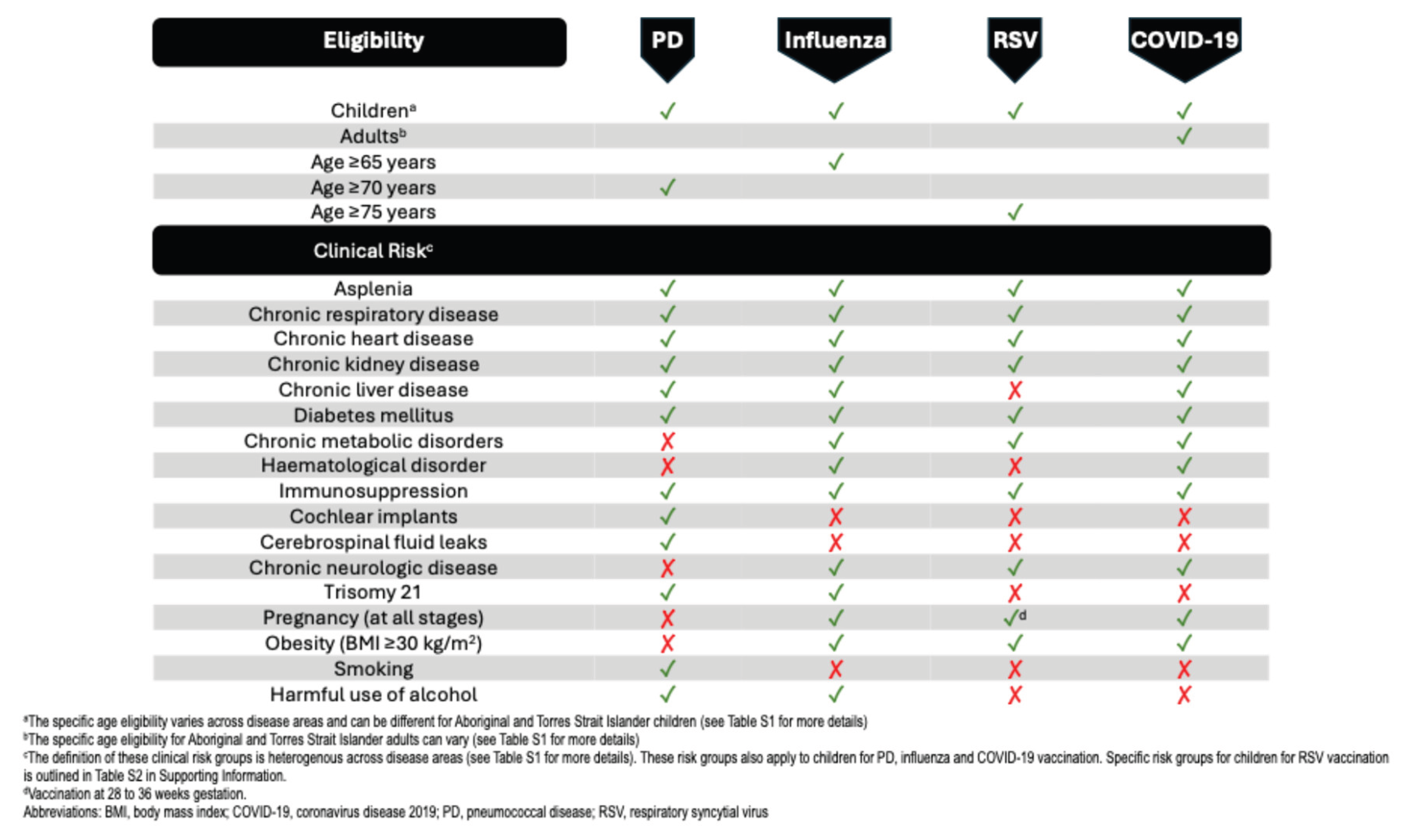

3. Current Australian Respiratory Immunisation Guidance

3.1. Current Australian Vaccination Recommendations

3.1.1. Pneumococcal Disease

3.1.2. Influenza

3.1.3. RSV

3.1.4. COVID-19

4. Expert Opinion

4.1. Gaps in Current Risk Group Definitions and Additional Risk Groups for Consideration

4.1.1. Expanding Age Groups

4.1.2. Cochlear Implants or Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Leaks

4.1.3. Presence of Multiple Risk Factors (Risk Stacking)

4.1.4. Frailty

4.1.5. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

4.1.6. High-Risk Paediatric Groups

4.1.7. High-Risk Adult Groups

4.1.8. People Living with Lung Diseases

4.1.9. Lifestyle Factors

4.1.10. Barriers to Vaccination Uptake

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALRI | Acute lower respiratory infections |

| ATAGI | Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation |

| CAP | Community-acquired pneumonia |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| HSCT | Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| ICER | Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IPD | Invasive pneumococcal disease |

| IRR | Incidence rate ratio |

| LRTD | Lower respiratory tract disease |

| NDIS | National Disability Insurance Scheme |

| NIP | National Immunisation Program |

| NNDSS | National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System |

| OM | Otitis media |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PCS | Post-Covid Syndrome |

| PD | Pneumococcal disease |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted-life-years |

| RSV | Respiratory syncytial virus |

| SOFA | Sequential organ failure assessment |

| TIV | Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine |

| VE | Vaccine effectiveness |

| VPRI | Vaccine preventable respiratory infections |

References

- GBD 2021 Lower Respiratory Infections Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 974–1002.

- Edwards, B. and C. Jenkins, RESPIRATORY INFECTIOUS DISEASE BURDEN IN AUSTRALIA, Edition 1. Vol. 2025. 2007: The Australian Lung Foudation.

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), Australian Immunisation Handbook. 2022, Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

- Toms, C.R. de Kluyver, and Enhanced Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Surveillance Working Group for the Communicable Diseases Network Australia, Invasive pneumococcal disease in Australia, 2011 and 2012. Communicable Disease Intelligence 2016, 40, E267–E284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, V.K. Hentrich, and B. Henriques-Normark, Virus-Induced Changes of the Respiratory Tract Environment Promote Secondary Infections With Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 643326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, C.; et al. Bronchiectasis among Indigenous adults in the Top End of the Northern Territory, 2011-2020: a retrospective cohort study. Med J Aust 2024, 220, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, A.J.; et al. Hearing loss in Australian First Nations children at 6-monthly assessments from age 12 to 36 months: Secondary outcomes from randomised controlled trials of novel pneumococcal conjugate vaccine schedules. PLoS Med 2024, 21, e1004375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contou, D.; et al. Bacterial and viral co-infections in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia admitted to a French ICU. Ann Intensive Care 2020, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, R.; et al. The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity for unravelling the causative association between respiratory viruses and pneumococcus-associated disease in young children: a prospective study. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, K. and S. Williams, Burden of pneumococcal disease in adults aged 65 years and older: an Australian perspective. Pneumonia (Nathan) 2016, 8, 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirmesropian, S.; et al. Pneumonia hospitalisation and case-fatality rates in older Australians with and without risk factors for pneumococcal disease: implications for vaccine policy. Epidemiol Infect 2019, 147, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Centre for Immunisation reserach and surveillence. Significant events in pneumococcal vaccination practice in Australia. 2024. Available online: https://ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2024-05/Pneumococcal_May%202024.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Jayasinghe, S. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in children. Microbiology Australia 2024, 45, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meder, K.N.; et al. Long-term Impact of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines on Invasive Disease and Pneumonia Hospitalizations in Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 70, 2607–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.; et al. Long-term Impact of a “3 + 0” Schedule for 7- and 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines on Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Australia, 2002-2014. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.; et al. Long-term Vaccine Impact on Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Among Children With Significant Comorbidities in a Large Australian Birth Cohort. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019, 38, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming-Dutra, K.E.; et al. Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on vaccine-type nasopharyngeal carriage. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2014. 33 Suppl 2(Suppl 2 Optimum Dosing of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine For Infants 0 A Landscape Analysis of Evidence Supportin g Different Schedules), S152–60.

- Marra, F.; et al. The protective effect of pneumococcal vaccination on cardiovascular disease in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 99, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdrizet, J.; et al. Retrospective Impact Analysis and Cost-Effectiveness of the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Infant Program in Australia. Infect Dis Ther 2021, 10, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyda, A.; et al. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in Australian adults: a systematic review of coverage and factors associated with uptake. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F.B.; et al. Uptake of pneumococcal vaccines in older Australian adults before and after universal public funding of PCV13. Vaccine 2024, 42, 3084–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, B.; et al. Annual Immunisation coverage report 2023. 2024: NCIRS.

- Kim, H., R.G. Webster, and R.J. Webby, Influenza Virus: Dealing with a Drifting and Shifting Pathogen. Viral Immunol. 2018, 31, 174–183.

- Imai, C.; et al. ATAGI Targeted Review 2023: Vaccination for prevention of influenza in Australia. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 2024, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.; et al. Summary of National Surveillance Data on Vaccine Preventable Diseases in Australia, 2016-2018 Final Report. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazareno, A.L.; et al. Modelled estimates of hospitalisations attributable to respiratory syncytial virus and influenza in Australia, 2009-2017. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022, 16, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscatello, D.J.; et al. Influenza-associated mortality in Australia, 2010 through 2019: High modelled estimates in 2017. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7578–7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blyth, C.C.; et al. Influenza Epidemiology, Vaccine Coverage and Vaccine Effectiveness in Children Admitted to Sentinel Australian Hospitals in 2017: Results from the PAEDS-FluCAN Collaboration. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 68, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.; et al. Vaccine Preventable Diseases and Vaccination Coverage in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, Australia, 2016-2019. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, L.; et al. Baseline incidence of adverse birth outcomes and infant influenza and pertussis hospitalisations prior to the introduction of influenza and pertussis vaccination in pregnancy: a data linkage study of 78 382 mother-infant pairs, Northern Territory. Austral. Epidemiol Infect 2019, 147, e233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, D.; et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe influenza infection: an individual participant data meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2019, 19, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufus Ashiedu, P.; et al. Medically-attended respiratory illnesses amongst pregnant women in Brisbane, Australia. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2015, 39, E319–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A.; et al. Influenza hospitalizations in Australian children 2010-2019: The impact of medical comorbidities on outcomes, vaccine coverage, and effectiveness. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022, 16, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Immunisation Reserach and Surveillence. Significant events in influenza vaccination practice in Australia. 2024. Available online: https://ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2024-11/Influenza_November%202024.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Ernst & Young Global Limited, Evaluation of the 2020 Influenza Season and assessment of system readiness for a COVID-19 vaccine. 2021, Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

- Cheng, A.C.; et al. Influenza epidemiology in patients admitted to sentinel Australian hospitals in 2016: the Influenza Complications Alert Network (FluCAN). Commun Dis Intell 2017, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.C.; et al. Influenza epidemiology in patients admitted to sentinel Australian hospitals in 2017: the Influenza Complications Alert Network (FluCAN). Commun Dis Intell 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.C.; et al. Influenza epidemiology in patients admitted to sentinel Australian hospitals in 2018: the Influenza Complications Alert Network (FluCAN). Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.C.; et al. Influenza epidemiology in patients admitted to sentinel Australian hospitals in 2019: the Influenza Complications Alert Network (FluCAN). Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.G.; et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Influenza-associated Hospitalizations During Pregnancy: A Multi-country Retrospective Test Negative Design Study, 2010-2016. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 68, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.Y.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of influenza vaccination among residents of long-term care facilities. Vaccine 2019, 37, 6329–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; et al. Influenza vaccine as a coronary intervention for prevention of myocardial infarction. Heart 2016, 102, 1953–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, J.E.; et al. Influenza and pertussis vaccine coverage in pregnancy in Australia, 2016-2021. Med J Aust 2023, 218, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, B.; et al. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2020. 2021: NCIRS.

- Self, A.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease morbidity in Australian infants aged 0 to 6 months: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D.A.; et al. The Changing Detection Rate of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Adults in Western Australia between 2017 and 2023. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, T.; et al. Prevalence and Incidence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Other Respiratory Viral Infections in Children Aged 6 Months to 10 Years With Influenza-like Illness Enrolled in a Randomized Trial. Clin Infect Dis 2015, 60, e80–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, G.B.; et al. The point prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus in hospital and community-based studies in children from Northern Australia: studies in a ‘high-risk’ population. Rural Remote Health 2019, 19, 5267. [Google Scholar]

- Sarna, M.; et al. Viruses causing lower respiratory symptoms in young children: findings from the ORChID birth cohort. Thorax 2018, 73, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.C.; et al. Assessing the Burden of Laboratory-Confirmed Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in a Population Cohort of Australian Children Through Record Linkage. J Infect Dis 2020, 222, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homaira, N.; et al. High burden of RSV hospitalization in very young children: a data linkage study. Epidemiol Infect 2016, 144, 1612–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanos, G.L.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalisations in Australia, 2006-2015. Med J Aust 2019, 210, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, A.T.; et al. Developing a prediction model to estimate the true burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in hospitalised children in Western Australia. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarna, M.; et al. Determining the true incidence of seasonal respiratory syncytial virus-confirmed hospitalizations in preterm and term infants in Western Australia. Vaccine 2023, 41, 5216–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaira, N.; et al. Risk factors associated with RSV hospitalisation in the first 2 years of life, among different subgroups of children in NSW: a whole-of-population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusco, N.K.; et al. The 2018 annual cost burden for children under five years of age hospitalised with respiratory syncytial virus in Australia. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanos, G.L.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Neurologic Complications in Children: A Systematic Review and Aggregated Case Series. J Pediatr 2021, 239, 39–49.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmle-Ruff, I. and N.W. Crawford, Respiratory syncytial virus prevention is finally here: An overview of safety. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2024, 53, 704–708.

- Papi, A.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Protein Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, M.; et al. Use of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccines in Older Adults: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023, 72, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmann, B.; et al. Bivalent Prefusion F Vaccine in Pregnancy to Prevent RSV Illness in Infants. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lacort, M.; et al. Early estimates of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis effectiveness against hospital admission for respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in infants, Spain, October 2023 to January 2024. Euro Surveill 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moline, H.L.; et al. Early Estimate of Nirsevimab Effectiveness for Prevention of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospitalization Among Infants Entering Their First Respiratory Syncytial Virus Season - New Vaccine Surveillance Network, October 2023-February 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024, 73, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.C.; et al. Effectiveness of Palivizumab against Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Cohort and Case Series Analysis. J Pediatr 2019, 214, 121–127.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazareno, A.L.; et al. Modelling the epidemiological impact of maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccination in Australia. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. In COVID-19; 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/covid-19 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths due to COVID-19, influenza and RSV in Australia - 2022 - May 2024. Acute respiratory disease mortality in Australia; 2024. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/deaths-due-covid-19-influenza-and-rsv-australia-2022-may-2024 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Akhtar, Z.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 and COVID vaccination on cardiovascular outcomes. European Heart Journal Supplements 2023, 25 (Suppl. A), A42–A49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, S.; et al. Assessment of COVID-19 as the Underlying Cause of Death Among Children and Young People Aged 0 to 19 Years in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2253590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; et al. High risk groups for severe COVID-19 in a whole of population cohort in Australia. BMC Infect Dis 2021, 21, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, C. and R. Anderson, The role of co-infections and secondary infections in patients with COVID-19. Pneumonia (Nathan) 2021, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allotey, J.; et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 370, m3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, F.; et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in high compared to low risk pregnancies complicated by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (phase 2): the World Association of Perinatal Medicine working group on coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021, 3, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffee, M.J.; et al. Race and ethnicity in the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium: demographics, treatments, and outcomes, an international observational registry study. Int J Equity Health 2023, 22, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzel, D.; et al. Prospective characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 infections among children presenting to tertiary paediatric hospitals across Australia in 2020: a national cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e054510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, A.L.; et al. Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2-Positive Youths Tested in Emergency Departments: The Global PERN-COVID-19 Study. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2142322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.S.; et al. The Spectrum of Postacute Sequelae of COVID-19 in Children: From MIS-C to Long COVID. Annu Rev Virol 2024, 11, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurdasani, D.; et al. Acute hepatitis of unknown aetiology in children: evidence for and against causal relationships with SARS-CoV-2, HAdv and AAV2. BMJ Paediatr Open 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/345824/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post-COVID-19-condition-Clinical-case-definition-2021.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Sk Abd Razak, R.; et al. Post-COVID syndrome prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalakkannan, A.; et al. Factors associated with general practitioner-led diagnosis of long COVID: an observational study using electronic general practice data from Victoria and New South Wales. Australia. Med J Aust 2024, 221 (Suppl 9), S18–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsampasian, V.; et al. Risk Factors Associated With Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2023, 183, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, V.; et al. The public health and economic burden of long COVID in Australia, 2022-24: a modelling study. Med J Aust 2024, 221, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Aged Care. About the National COVID-19 Vaccine Program; 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/covid-19-vaccines/about-rollout#:~:text=Program%20governance-,About%20the%20program,death%20due%20to%20COVID%2D19 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Department of Health and Aged Care. COVID-19 vaccination for residential aged care workers; 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/covid-19-vaccines/information-for-aged-care-providers-workers-and-residents-about-covid-19-vaccines/residential-aged-care-workers.

- Liu, B.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against COVID-19 specific and all-cause mortality in older Australians: a population based study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2023, 40, 100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; et al. Effectiveness of XBB.1.5 monovalent COVID-19 vaccine against COVID-19 mortality in Australians aged 65 years and older during 23 to February 2024. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, T.; et al. Nosocomial COVID-19 infection in the era of vaccination and antiviral therapy. Intern Med J 2024, 54, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, D.; et al. A prospective observational cohort study of covid-19 epidemiology and vaccine seroconversion in South Western Sydney, Australia, during the 2021-2022 pandemic period. BMC Nephrol 2024, 25, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, M. and J. Shaman, Direct Observation of Repeated Infections With Endemic Coronaviruses. J Infect Dis 2021, 223, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness monitoring in Australia. Microbiology Australia 2024, 45, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institiute of Health and Welfare, The impact of a new disease: COVID-19 from 2020, 2021 and into 2022, in Australia’s Health 2022: data insights. 2022.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. COVID-19 Vaccine Program; 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-12/covid-19-vaccine-rollout-update-12-december-2024.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Department of Health and Aged Care. COVID-19 vaccination rates of aged care residents by facility. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/residential-aged-care-residents-covid-19-vaccination-rates?language=en.

- Chen, C.; et al. The role of timeliness in the cost-effectiveness of older adult vaccination: A case study of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Australia. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.M.; et al. Cost-benefit analysis of a national influenza vaccination program in preventing hospitalisation costs in Australian adults aged 50-64 years old. Vaccine 2019, 37, 5979–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institiute of Health and Welfare. Multimorbidity; 2025. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/multimorbidity# (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Morton, J.B.; et al. Risk stacking of pneumococcal vaccination indications increases mortality in unvaccinated adults with Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. Vaccine 2017, 35, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossfield, S.S.R.; et al. Interplay between demographic, clinical and polygenic risk factors for severe COVID-19. Int J Epidemiol 2022, 51, 1384–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGovern, I.; et al. Number of Influenza Risk Factors Informs an Adult’s Increased Potential of Severe Influenza Outcomes: A Multiseason Cohort Study From 2015 to 2020. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024, 11, ofae203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; et al. Assessing the Impact of Frailty on Infection Risk in Older Adults: Prospective Observational Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2024, 10, e59762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengele, L.; et al. Frailty but not sarcopenia nor malnutrition increases the risk of developing COVID-19 in older community-dwelling adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022, 34, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai-Saito, K.; et al. Association of frailty with influenza and hospitalization due to influenza among independent older adults: a longitudinal study of Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). BMC Geriatr 2023, 23, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branche, A.R.; et al. Residency in Long-Term Care Facilities: An Important Risk Factor for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Hospitalization. J Infect Dis 2024, 230, e1007–e1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, M.J.; et al. Acute lower respiratory infections in Indigenous infants in Australia’s Northern Territory across three eras of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use (2006-15): a population-based cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020, 4, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, A.J.; et al. Otitis media outcomes of a combined 10-valent pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine schedule at 1-2-4-6 months: PREVIX_COMBO, a 3-arm randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 2021, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, A.J.; et al. Immunogenicity, otitis media, hearing impairment, and nasopharyngeal carriage 6-months after 13-valent or ten-valent booster pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, stratified by mixed priming schedules: PREVIX_COMBO and PREVIX_BOOST randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1374–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beissbarth, J.; et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage of otitis media pathogens in infants receiving 10-valent non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10), 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or a mixed primary schedule of both vaccines: A. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2264–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.L.; et al. Vaccine-preventable disease following allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant in Western Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2019, 55, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajkov, D.; et al. A Multiseason Randomized Controlled Trial of Advax-Adjuvanted Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in Participants With Chronic Disease or Older Age. J Infect Dis 2024, 230, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; et al. Equity in disease prevention: Vaccines for the older adults - a national workshop, Australia 2014. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5463–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemben, N.M. and M.L. Berg, Efficacy of inactivated vaccines in patients treated with immunosuppressive drug therapy. Pharmacotherapy 2022, 42, 334–342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lung Foundation Australia, Vital vaccines for Australian adults: improving coverage to reduce the impact of respiratory disease. 2024, Milton: Lung Foundation Australia.

- Jiang, C.Q. Chen, and M. Xie, Smoking increases the risk of infectious diseases: A narrative review. Tob Induc Dis 2020. 18, 60.

- Van Buynder, P.G.; et al. Antigen specific vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2814–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.; et al. Assessment of the first 5 years of pharmacist-administered vaccinations in Australia: learnings to inform expansion of services. Public Health Res Pract 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).