1. Introduction

The therapeutic landscape for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has markedly evolved with the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) combinations and ICI–tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) regimens, which now constitute established first-line standards. Pivotal phase III trials, including CheckMate 214 (nivolumab plus ipilimumab) [

1], KEYNOTE-426 (pembrolizumab plus axitinib) [

2], JAVELIN Renal 101 (avelumab plus axitinib) [

3], and CLEAR (lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab) [

4], demonstrated superior overall survival or progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes compared with control-arm therapy, thereby establishing ICI-based combinations as standard first-line options. In addition, the CheckMate 9ER trial confirmed the efficacy of nivolumab plus cabozantinib (Cabo) as a first-line regimen [

5], further extending the clinical utility of Cabo across treatment sequences.

Notably, Cabo had originally been validated as a post-TKI therapy in the METEOR trial [

6], a phase III randomized controlled study that demonstrated its superiority over everolimus in patients previously treated with one or more TKIs. Given its multitargeted inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase (MET), and AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL) pathways, Cabo has become a key agent in both post-TKI and post-ICI settings. However, reliable on-treatment biomarkers that dynamically reflect host–tumor interactions during Cabo therapy remain limited, particularly in the post-ICI era.

In the current treatment paradigm, Cabo remains a widely utilized subsequent-line therapy following progression on ICI-based regimens. Multiple real-world studies have confirmed its sustained clinical efficacy in the post-ICI setting, with median progression-free survival (PFS) ranging from approximately 6 to 10 months and objective response rates (ORRs) around 20–30% [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Nevertheless, substantial response heterogeneity persists, and the absence of robust predictive biomarkers continues to limit individualized treatment optimization.

Systemic inflammation– and nutrition-related indices such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), serum albumin (Alb), and systemic immune–inflammation index (SII) have been associated with survival outcomes in mRCC [

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, most studies have relied solely on baseline measurements, which fail to capture the dynamic biological changes induced by Cabo treatment—such as alterations in tumor–immune interaction, cytokine milieu, and metabolic balance. Given Cabo’s pleiotropic effects on the tumor microenvironment, on-treatment temporal changes (Δ) in host inflammatory and nutritional markers may better reflect treatment response dynamics than static baseline values. Yet, evidence evaluating such early Δ-based biomarkers during Cabo therapy remains scarce.

To address this gap, the present study investigated the prognostic utility of an integrated ΔAlb + ΔSII composite score that incorporates early changes in nutritional (serum albumin) and inflammatory (systemic immune–inflammation index) status during Cabo therapy in patients with mRCC previously treated with ICI-based regimens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

This retrospective observational study included patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) who received Cabo therapy at Kanazawa University Hospital between September 2020 and April 2025. Eligible patients met all of the following criteria: (1) histologically confirmed RCC; (2) received Cabo as second- or later-line therapy; (3) availability of laboratory data on serum albumin (Alb) and SII both at baseline and at 6 weeks after treatment initiation; and (4) evaluable PFS data.

Patients without post-treatment Alb or SII data were excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Kanazawa University (approval number 114944-1). Because of its retrospective design, the need for individual informed consent was waived. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Clinical and Laboratory Data Collection

Demographic and clinicopathological variables included age, sex, histology, International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) risk group, treatment line, and metastatic sites. The IMDC risk group was determined according to the established criteria, classifying patients as favorable, intermediate, or poor risk based on six prognostic factors (Karnofsky performance status < 80%, time from diagnosis to systemic therapy < 1 year, anemia, hypercalcemia, neutrophilia, and thrombocytosis) [

15]. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was inconsistently documented at Cabo initiation and was therefore excluded from the analyses to avoid selection bias.

Laboratory parameters were collected at baseline and at 6 weeks after Cabo initiation, including serum albumin (Alb), C-reactive protein (CRP), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

The SII was calculated as platelet count × neutrophil count/lymphocyte count using peripheral blood data. Relative changes were calculated as (value6w/value0w − 1) × 100 for both Alb (ΔAlb) and SII (ΔSII).

Baseline CRP levels were used in multivariable analyses, as shown in

Table 2. The relative dose intensity (RDI all time,%) of Cabo was defined as the ratio of the total delivered to the planned total dose throughout the entire treatment course.

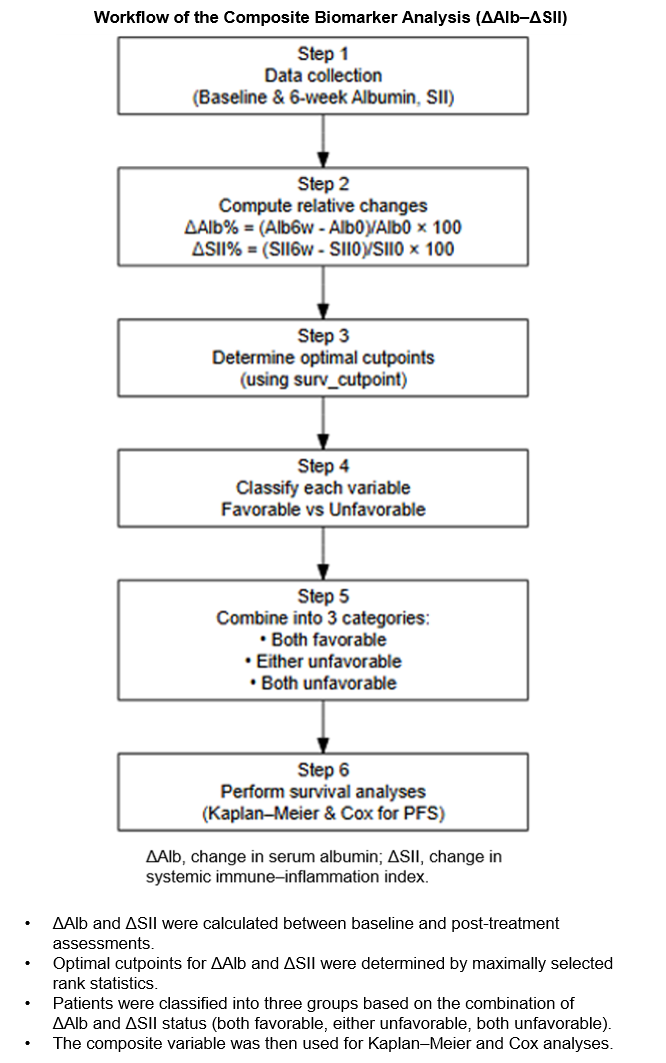

2.3. Derivation of ΔAlb and ΔSII Composite Score

For each patient, relative changes in Alb and SII were dichotomized using their respective median values as cut-offs (unfavorable: ΔAlb below the median; ΔSII above the median). A composite score (ΔAlb + ΔSII composite) was then derived as the sum of these indicators: 0 = both favorable, 1 = either unfavorable, and 2 = both unfavorable.

This median-based classification was prespecified and applied consistently across analyses to ensure reproducibility. The derivation process is detailed in the

Supplementary Materials.

Relative changes in other inflammation-related markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), were also explored as described in the

Supplementary Materials. However, both ΔCRP and ΔNLR showed limited dynamic ranges and weak correlations with treatment outcomes, and were therefore not included in the composite model.

2.4. Assessment of Treatment-Related Adverse Events (TRAEs)

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Events were categorized as early (occurring within 6 weeks after Cabo initiation) or total (occurring at any time during treatment). Grade ≥ 3 events were also identified separately. The detailed distribution of early and total TRAEs is summarized in the

Supplementary Materials.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The primary endpoint was PFS, defined as the interval from Cabo initiation to radiographic progression or death from any cause. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to explore associations between each clinical variable and PFS.

Variables with p < 0.1 in univariate analyses were entered into a multivariate Cox regression model, which included the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite, IMDC risk group, and relative dose intensity (RDI all time) as covariates.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated according to the composite score, and differences among the three categories (“both favorable,” “either unfavorable,” and “both unfavorable”) were tested using the log-rank trend test. The proportional hazards assumption was examined using scaled Schoenfeld residuals.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to confirm robustness of the findings:

(1) in patients who had received prior immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy only (Prior ICI = 1);

(2) by testing the interaction between composite and Prior ICI; and

(3) by excluding the single ICI-naïve patient.

Analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and the survival, survminer, and ggplot2 packages, and two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 40 patients with advanced RCC who received Cabo between September 2020 and April 2025 were included in this study. The median age at treatment initiation was 68.0 years (interquartile range [IQR], 59.8–73.3), and 34 patients (85%) were male. Most patients had clear cell histology, and the distribution of IMDC risk groups was as follows: 13 (32.5%) favorable, 22 (55.0%) intermediate, and 5 (12.5%) poor.

Cabo was mainly used as second- or later-line therapy. The median relative dose intensity (RDI all time) was 31.6% (IQR, 22.5–33.5). At baseline, the median serum albumin (Alb) was 3.80 g/dL (IQR, 3.20–4.00), C-reactive protein (CRP) was 0.96 mg/dL (IQR, 0.21–5.76), and the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) was 1352 (IQR, 678–2170).

ECOG performance status was inconsistently recorded at Cabo initiation and was therefore excluded from the analyses to avoid potential selection bias.

The distribution of the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite score (composite) was as follows: composite = 0 (n = 11), composite = 1 (n = 21), and composite = 2 (n = 6), with two cases missing. Detailed laboratory parameter transitions are summarized in

Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 40).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 40).

| Variable |

n (%) |

| Age at cabozantinib initiation, years |

68.00 [59.75–73.25] * |

| Sex |

|

| Male |

34(85.0) |

| Female |

6 (15.0) |

| Histology |

|

| Clear cell |

36 (90.0) |

| Non-clear cell |

4 (10.0) |

| IMDC risk group |

|

| Favorable |

13 (32.5) |

| Intermediate |

22 (55.0) |

| Poor |

5 (12.5) |

| Treatment line of cabozantinib |

|

| Second line |

12 (30.0) |

| ≥ Third line |

28 (70.0) |

| Prior nephrectomy |

33 (82.5) |

| Prior ICI exposure |

39 (97.5) |

| Prior TKI exposure |

36 (87.5) |

| **Metastatic sites |

|

| Lung |

31 (77.5) |

| Lymph node |

19 (47.5) |

| Liver |

16 (40.0) |

| Bone |

11 (27.5) |

| Pancreas |

3 (7.5) |

| Pleura |

2 (5.0) |

| Brain |

1 (2.5) |

| Baseline serum albumin (g/dL) |

3.80 [3.20–4.00] * |

| Baseline CRP (mg/dL) |

0.96 [0.21–5.76] * |

| Baseline NLR |

4.60 [3.25–6.82] * |

| Baseline SII |

1352 [678–2170] * |

| ***Baseline LDH (U/L) |

189 [135–252] * |

| RDI all time |

31.59 [22.49–33.47] * |

| Starting dose of cabozantinib (mg/day) |

20 [20–40] * |

| Dose reduction within 6 weeks |

20 (50.0) |

| Progression-free survival (months) |

8.4 [4.0–12.9] * |

3.2. Changes in Alb and SII After 6 Weeks

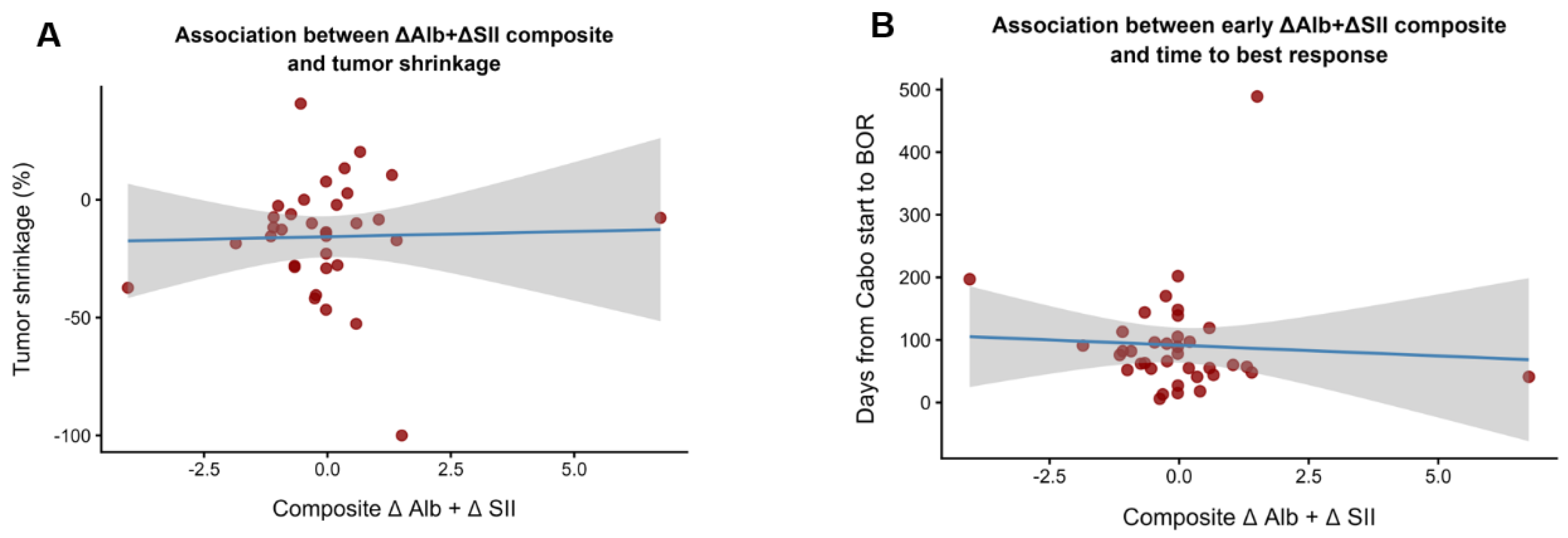

At 6 weeks after Cabo initiation, Alb levels decreased in most patients, whereas the SII generally increased compared with baseline values. The relative change (ΔAlb, ΔSII) demonstrated an inverse relationship between nutritional status and systemic inflammation.

As illustrated in

Figure 1A, a greater decline in Alb was associated with less tumor shrinkage, suggesting a link between early nutritional deterioration and limited antitumor efficacy. Similarly,

Figure 1B shows that patients with both unfavorable changes (ΔAlb below and ΔSII above the median) tended to reach their best overall response earlier, indicating rapid progression rather than durable disease control.

Overall, these early dynamics in Alb and SII reflect the biological divergence between patients with favorable versus unfavorable systemic inflammatory responses to Cabo therapy.

3.3. Progression-Free Survival According to ΔAlb + ΔSII Composite Score

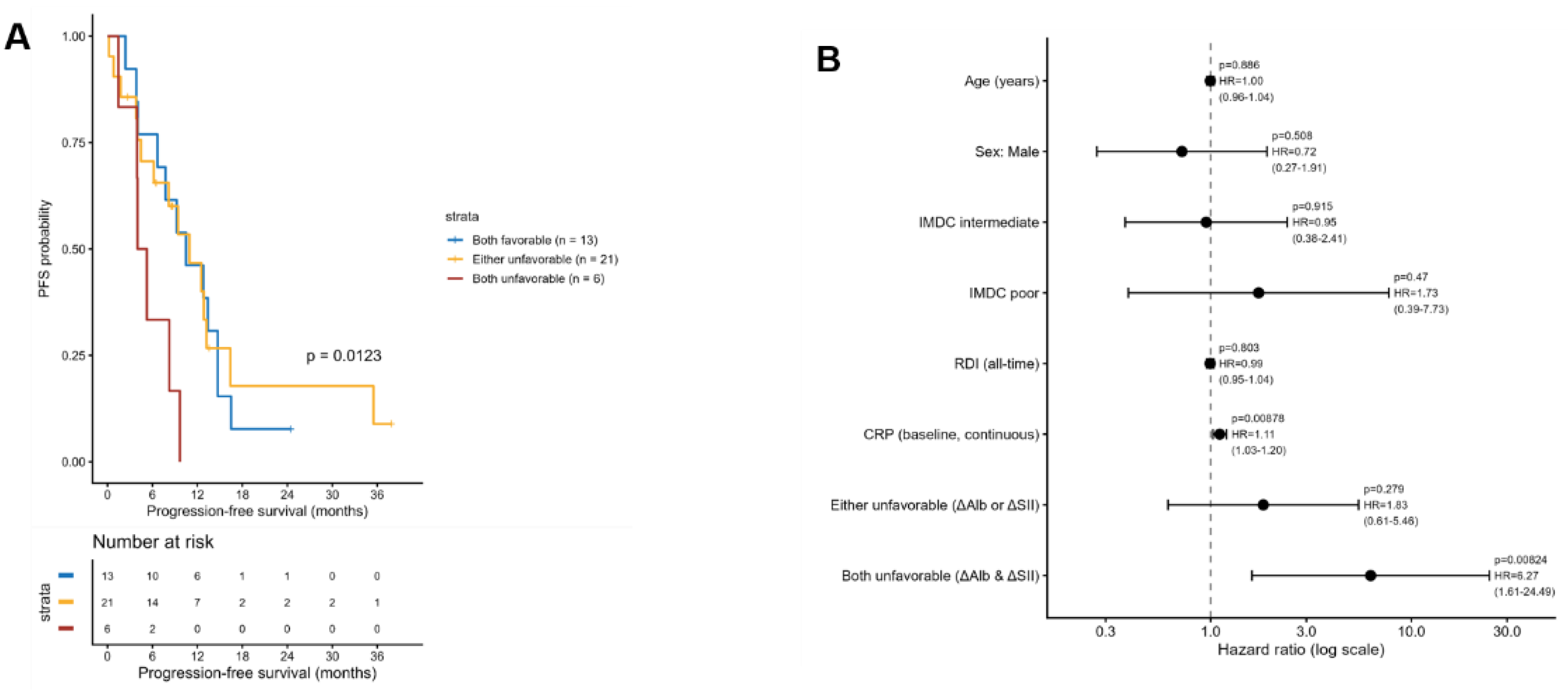

Progression-free survival (PFS) differed markedly according to the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite score.

As shown in

Figure 2A, patients with both favorable changes (composite = 0) achieved the longest median PFS, whereas those with both unfavorable changes (composite = 2) experienced the shortest. The PFS trend across the three categories (“both favorable,” “either unfavorable,” and “both unfavorable”) was statistically significant (log-rank test for trend, p = 0.0123).

In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (

Figure 2A &

Table 2), the composite score remained an independent prognostic factor for PFS after adjustment for age, sex, IMDC risk group, RDI all time, and baseline CRP. Compared with the reference group (both favorable), the adjusted hazard ratios were 1.83 (95% CI, 0.61–5.46; p = 0.279) for the “either unfavorable” group and 6.27 (95% CI, 1.61–24.49; p = 0.008) for the “both unfavorable” group.

Exploratory analyses of other inflammation-related markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), are shown in the

Supplementary Materials (

Supplementary Figure S2). Both ΔCRP and ΔNLR exhibited minimal variability and were therefore not incorporated into the composite model. Because NLR is mathematically included within the SII formula, it was also excluded from the multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis to avoid collinearity.

Other covariates, including Age, Sex, IMDC risk group, and RDI, were not significantly associated with PFS. The proportional hazards assumption was not violated (global PH test, p = 0.587;

Supplementary Figure S4).

3.4. Sensitivity and Exploratory Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the findings.

First, when restricted to patients who had received prior immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy (n = 39), the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite score remained significantly associated with progression-free survival (

Supplementary Table S3).

Second, the interaction term between the composite score and prior ICI exposure (composite × Prior ICI) was not statistically significant, indicating that the prognostic effect of the composite was independent of prior ICI therapy.

Third, exclusion of the single ICI-naïve case did not materially alter the results.

Additionally, an exploratory analysis was conducted to evaluate the internal consistency of albumin change metrics (

Supplementary Figure S5 and Table S4). The relative (ΔAlb%) and absolute (ΔAlb g/dL) changes were highly correlated. Among the 38 evaluable patients, 9 met both the relative (≤ –4%) and absolute (≤ –0.2 g/dL) decrease thresholds, 2 met either, and 29 met neither.

These results confirm the internal validity and robustness of ΔAlb-based classification within the composite index.

3.5. Treatment-Related Adverse Events

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were common during Cabo therapy and are summarized in

Supplementary Figure S3A & S3B. Early TRAEs (≤6 weeks after treatment initiation) were observed in 32 of 40 patients (80%), and any-grade events during the total treatment course occurred in 36 patients (90%).

The most frequent early TRAEs were decreased appetite (42.5%), fatigue (35.0%), and diarrhea (30.0%), which largely overlapped with events occurring over the entire treatment period. Grade ≥3 events occurred in 6 patients (15%) within the first 6 weeks and in 10 patients (25%) overall. The most common severe events were fatigue, hypertension, and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia.

No treatment-related deaths occurred. Most TRAEs were manageable with dose reductions or temporary treatment interruptions, and no unexpected safety signals were identified compared with previous clinical experience with Cabo.

3.6. Internal Validation by Bootstrap Resampling

To evaluate the internal validity and potential overfitting of the multivariable Cox model, bootstrap resampling was performed with 1,000 iterations. The calibration curve comparing the predicted and observed 12-month progression-free survival (PFS) probabilities demonstrated good agreement (

Supplementary Figure S6).

The bootstrap-corrected calibration line closely approximated the ideal diagonal, indicating minimal optimism in model performance. The apparent and bias-corrected estimates showed only minor deviation, suggesting that the model retained stable predictive accuracy after internal validation.

These results support the robustness and generalizability of the multivariable Cox model for predicting PFS based on early changes in albumin and systemic immune-inflammation index during Cabo therapy.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated early dynamic changes in serum albumin (ΔAlb) and the systemic immune–inflammation index (ΔSII) during cabozantinib(Cabo) therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) previously treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Univariate and multivariable Cox regression analyses showed that the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite score was associated with progression-free survival (PFS), remaining significant after adjustment for age, sex, IMDC risk group, relative dose intensity (RDI), and baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) (HR for both unfavorable vs. both favorable = 6.27, 95% CI 1.61–24.49). Although survival differences were most pronounced between the extreme categories, a consistent risk gradient was observed across the three groups (p for trend = 0.012).

Previous studies have reported the prognostic value of baseline inflammatory and nutritional markers such as NLR, SII, and albumin in mRCC treated with TKIs or ICIs [

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, few have explored early on-treatment dynamics or integrated composite changes in these parameters. To our knowledge, this is among the first studies to incorporate ΔAlb and ΔSII into a unified prognostic framework in the post-ICI Cabo setting.

Biologically, the SII integrates neutrophil and platelet counts relative to lymphocytes, reflecting the balance between pro-tumor inflammation and anti-tumor immunity—components that overlap with IMDC prognostic factors (neutrophilia, thrombocytosis). Cabo, a multitarget TKI, has been shown to reduce myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), normalize tumor vasculature, and enhance effector T-cell trafficking [

16,

17,

18,

19]. A decline in SII during treatment may therefore reflect immunomodulatory effects, though this remains a hypothesis requiring direct validation. Similarly, early declines in albumin may capture tumor-driven catabolic stress or impaired host resilience, but causality cannot be inferred from this observational study.

The ΔAlb + ΔSII composite relies solely on routine laboratory parameters—serum albumin and complete blood counts—enabling early on-treatment assessment at 6 weeks. Treatment-related adverse events were comparable across composite categories (

Supplementary Figure S3), suggesting that early deteriorations in Alb or SII likely reflect disease biology rather than treatment toxicity.

Exploratory internal validation using bootstrap resampling (B = 1000) yielded an optimism-corrected concordance index (C-index) of 0.61, indicating limited but above-random predictive discrimination despite the small sample size (n = 38) (

Figure 2A & 2B). This preliminary performance does not support immediate clinical application but justifies further investigation in larger, prospective cohorts to assess reproducibility and clinical utility.

From a translational perspective, concordant unfavorable changes in Alb and SII may represent tumor-driven systemic stress and immune suppression, whereas favorable dynamics could suggest preserved host integrity. Exploratory analyses also showed high correlation between relative and absolute albumin changes (

Supplementary Figures S5–S6), supporting the robustness of ΔAlb as a continuous marker.

Systemic inflammatory indices like SII and NLR have been reported to dynamically reflect immune restoration during effective therapy in mRCC and other cancers [

20,

21]. Hypoalbuminemia, beyond nutritional depletion, reflects tumor-induced acute-phase responses mediated by proinflammatory cytokines [

22,

23]. Integrating ΔAlb and ΔSII thus provides a composite view of host–tumor metabolic and immunologic interplay, offering a mechanistically plausible—though not yet validated—framework for monitoring treatment adaptation.

In summary, this small retrospective analysis suggests that early combined changes in albumin and SII are associated with PFS during Cabo therapy after ICI therapy. The ΔAlb + ΔSII composite is simple, low-cost, and derived from routine blood tests, with preliminary evidence of prognostic discrimination (C-index = 0.61 after bootstrap correction). Prospective validation in independent, larger cohorts is essential before considering any role in risk stratification or treatment decision-making.

5. Conclusions

Early on-treatment changes in serum albumin and the systemic immune–inflammation index (ΔAlb + ΔSII composite) were associated with progression-free survival in ICI-pretreated mRCC patients receiving Cabo, with a significant risk gradient across composite categories (p for trend = 0.012). Exploratory internal validation yielded an optimism-corrected C-index of 0.61, indicating limited but above-random discrimination. This simple, laboratory-based composite shows preliminary promise as a dynamic prognostic tool but requires prospective validation in larger cohorts before clinical consideration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: Derivation of ΔAlb + ΔSII composite score; Figure S2: Distribution of ΔCRP_rel and ΔNLR_rel in the study cohort; Figure S3: Treatment-related adverse events; Figure S4: Proportional hazards (PH) assumption test for the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite model; Figure S5: Relationship between relative and absolute changes in serum albumin (ΔAlb); Figure S6: Bootstrap-based internal validation of the ΔAlb + ΔSII composite model; Table S1: Laboratory parameter changes from baseline to 6 weeks; Table S2: Univariate Cox proportional hazard model; Table S3: Sensitivity analysis of PFS according to ΔAlb + ΔSII composite (Prior ICI only vs. all patients); Table S4: Concordance between relative and absolute albumin decrease criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rikushi Fujimura, Tomoyuki Makino, Suguru Kadomoto, and Hiroshi Yaegashi; methodology, Hiroshi Yaegashi; data curation, Rikushi Fujimura, Hiroshi Yaegashi, Ryunosuke Nakagawa, Taiki Kamijima, Hiroshi Kano, Renato Naito, Hiroaki Iwamoto, Kazuyoshi Shigehara, Takahiro Nohara and Kouji Izumi; writing—original draft preparation, Rikushi Fujimura and Hiroshi Yaegashi; writing—review and editing, Hiroshi Yaegashi; supervision, Kouji Izumi and Atsushi Mizokami. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kanazawa University Institutional Review Board (approval number 114944-1, 20 August 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

The need for written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for language refinement and editorial assistance (e.g., improving clarity, conciseness, and grammatical accuracy of manuscript text). The authors reviewed and edited all output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Alb |

Serum albumin |

| AXL |

AXL receptor tyrosine kinase |

| BOR |

Best overall response |

| Cabo |

Cabozantinib |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| Δ |

Change from baseline |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| ICI |

Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IMDC |

International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium |

| KM |

Kaplan–Meier |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

| mRCC |

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma |

| NLR |

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| RDI |

Relative dose intensity |

| SII |

Systemic immune–inflammation index |

| TKI |

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| TRAE |

Treatment-related adverse event |

References

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Aren Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthelemy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulieres, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Penkov, K.; Haanen, J.; Rini, B.; Albiges, L.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Negrier, S.; Uemura, M.; et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grunwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Kopyltsov, E.; Mendez-Vidal, M.J.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Zurawski, B.; Oyervides Juarez, V.M.; Hsieh, J.J.; Basso, U.; Shah, A.Y.; et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Escudier, B.; Powles, T.; Mainwaring, P.N.; Rini, B.I.; Donskov, F.; Hammers, H.; Hutson, T.E.; Lee, J.L.; Peltola, K.; et al. Cabozantinib versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovelli, R.; Ciccarese, C.; Facchini, G.; Milella, M.; Urbano, F.; Basso, U.; De Giorgi, U.; Sabbatini, R.; Santini, D.; Berardi, R.; et al. Cabozantinib After a Previous Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Multi-Institutional Analysis. Target Oncol 2020, 15, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, V.; Boegemann, M.; Rafiyan, M.-R.; Niegisch, G.; Schnabel, M.J.; Flörcken, A.; Maasberg, M.; Maintz, C.; Zahn, M.-O.; Wortmann, A.; et al. Final analysis of a non-interventional study on cabozantinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma after prior checkpoint inhibitor therapy (CaboCHECK). Journal of Clinical Oncology 40. [CrossRef]

- Sazuka, T.; Matsushita, Y.; Sato, H.; Osawa, T.; Hinata, N.; Hatakeyama, S.; Numakura, K.; Ueda, K.; Kimura, T.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of second-line cabozantinib after immuno-oncology combination therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma: Japanese multicenter retrospective study. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 20629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, H.; Nemoto, Y.; Tachibana, H.; Fukuda, H.; Yoshida, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Iizuka, J.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kondo, T.; Takagi, T. Real-world efficacy and safety of cabozantinib following immune checkpoint inhibitor failure in Japanese patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2023, 53, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A.J.; Knox, J.J.; Lin, X.; Simantov, R.; Xie, W.; Lawrence, N.; Broom, R.; Fay, A.P.; Rini, B.; Donskov, F.; et al. Change in Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio in Response to Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma as a Prognosticator and Biomarker of Efficacy. Eur Urol 2016, 70, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Fu, G.; Zu, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.T.; D'Souza, A.; Tulpule, V.; Quinn, D.I.; Bhowmick, N.A.; Weisenberger, D.J.; et al. Albumin levels predict prognosis in advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol 2022, 40, 12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuhler, V.; Herrmann, L.; Rausch, S.; Stenzl, A.; Bedke, J. Role of the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated with First-Line Ipilimumab plus Nivolumab. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, H.; Takagi, T.; Kondo, T.; Shimizu, S.; Tanabe, K. Predictive value of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with cytoreductive nephrectomy. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 14296–14305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, D.Y.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Warren, M.A.; Golshayan, A.R.; Sahi, C.; Eigl, B.J.; Ruether, J.D.; Cheng, T.; North, S.; et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 5794–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Fan, R.Y.; Zhang, S.R.; Li, C.Y.; Shen, L.Z.; Wei, P.; He, Z.H.; He, M.F. A systematical comparison of anti-angiogenesis and anti-cancer efficacy of ramucirumab, apatinib, regorafenib and cabozantinib in zebrafish model. Life Sci 2020, 247, 117402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Swanson, K.D.; Csizmadia, E.; Solanki, A.; Landon-Brace, N.; Gehring, M.P.; Helenius, K.; Olson, B.M.; Pyzer, A.R.; Wang, L.C.; et al. Cabozantinib Eradicates Advanced Murine Prostate Cancer by Activating Antitumor Innate Immunity. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki Bakhtiarvand, V.; Ramezani-Ali Akbari, K.; Amir Jalali, S.; Hojjat-Farsangi, M.; Jeddi-Tehrani, M.; Shokri, F.; Shabani, M. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) depletion by cabozantinib improves the efficacy of anti-HER2 antibody-based immunotherapy in a 4T1-HER2 murine breast cancer model. Int Immunopharmacol 2022, 113, 109470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, E.; Chaudhury, N.; Nasim, F. Novel therapeutic strategies targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cell immunosuppressive mechanisms for cancer treatment. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 2024, 5, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Li, Y.; Tan, S.; Cheng, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with immunotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader Marta, G.; Isaacsson Velho, P.; Bonadio, R.R.C.; Nardo, M.; Faraj, S.F.; de Azevedo Souza, M.C.L.; Muniz, D.Q.B.; Bastos, D.A.; Dzik, C. Prognostic Value of Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res 2020, 26, 2489–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulhar, R.; Ashraf, M.A.; Jialal, I. Reactants. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Muhammad Ashraf declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Ishwarlal Jialal declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Almasaudi, A.S.; Dolan, R.D.; Edwards, C.A.; McMillan, D.C. Hypoalbuminemia Reflects Nutritional Risk, Body Composition and Systemic Inflammation and Is Independently Associated with Survival in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).