1. Introduction

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic neuropathic pain disorder characterized by disproportionate pain, sensory disturbances, vasomotor changes, and functional impairment following tissue injury or surgery. (1). The underlying mechanisms involve peripheral inflammation, sympathetic dysregulation, and maladaptive neuroplasticity, leading to persistent pain and functional impairment.

Pediatric and adolescent CRPS, though less common than adult presentations, can be particularly disabling due to central sensitization and psychosocial vulnerability. (2). The condition may significantly impact physical function, academic participation, and emotional well-being. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach are critical for successful recovery.

Traditional management emphasizes exercise therapy, desensitization, and behavioral interventions. Exercise therapy and functional rehabilitation remain the cornerstone of treatment, as early mobilization can reverse sympathetic and cortical changes that perpetuate pain (3). However, there is a subset of patients who present with severe symptomatology or fail to respond to initial conservative measures and require pharmacologic or interventional therapy to achieve desensitization and functional restoration.

Diagnostic clarity has improved through the use of the Budapest criteria, which provide a standardized clinical framework for identifying CRPS. (4). Pharmacologic options such as gabapentinoids, antidepressants, and NMDA receptor antagonists are often used to modulate neuropathic pain pathways. Ketamine has gained increasing use as an NMDA receptor antagonist that interrupts central sensitization and “wind-up” mechanisms. (5).

Regional techniques provide targeted interruption of peripheral nociceptive input and sympathetically mediated pain via sustained local anesthetic delivery to the brachial plexus.(6). Continuous peripheral nerve blocks reduce afferent nociception, allow normalization of skin perfusion and temperature, and facilitate early active rehabilitation by providing reliable analgesia without the systemic adverse effects of high-dose opioids.When tunneled and managed according to established safety protocols, ambulatory continuous catheters enable prolonged regional analgesia, supporting progressive, graded exposure and desensitization in pediatric patients with refractory CRPS.Recent safety reports and case series in children demonstrate that prolonged catheter techniques can be performed without an increased risk of infectious or neurologic complications when careful aseptic technique and close outpatient follow-up are employed.(6,7)

This report presents an adolescent case of post-traumatic CRPS Type I effectively treated with a combination of subanesthetic ketamine infusion, gabapentin, and a tunneled supraclavicular continuous nerve catheter.

This article adheres to the guidelines laid by the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) network. Written informed consent for publication and presentation of this case, including the use of clinical images and video material, was obtained from the patient’s parents.

2. Case Description

A 15-year-old right-hand dominant female athlete, 71.7 kg, ASA 1, sustained an oblique fracture of the left third metacarpal while performing a gymnastics routine. Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning were performed the following day under general anesthesia, and immobilization was maintained in a short-arm mitten cast. Radiographs at four weeks demonstrated adequate alignment and callus formation, and pins were removed at six weeks.

Approximately three months after surgery, she presented to the hand surgery clinic with a history of persistent, intense burning hand pain accompanied by temperature asymmetry, swelling, and hypersensitivity to light touch since her last clinic visit. She had tried over-the-counter medications and “toughed it out” but did not have relief. She described the pain as continuous, sharp, and aggravated by movement or cold exposure. Examination revealed marked allodynia over the dorsum of the hand, mild coolness compared with the contralateral side, and guarding with active and passive motion. Distal perfusion and strength were preserved, and radiographs confirmed fracture union. The findings fulfilled clinical criteria for CRPS Type I.

Initial outpatient management included occupational therapy focused on graded desensitization, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen as needed. After six weeks, pain persisted at 7/10 on the numeric rating scale, and she continued to experience severe tactile hypersensitivity and limited finger flexion.

The patient was admitted approximately five months after surgery for escalation of care, and the pain service was consulted for managing her pain. On admission, she rated her resting pain 7/10 and exhibited hyperalgesia to light pressure without trophic skin changes or weakness. She reported episodes of excruciating pain, like someone was taking a saw and chopping her fingers off one by one. She was able to flex her fingers at the distal phalanges slightly, but was unable to make a fist due to her pain.

A subanesthetic ketamine infusion was initiated at 7 mg per hour with patient-controlled boluses of 3 mg every 15 minutes. Acetaminophen 1000 mg and ibuprofen 600 mg were administered orally every 6 hours. Gabapentin was started at 300 mg three times daily, and increased to 400 mg three times daily the next day. After 12 hours, pain decreased modestly to 5/10, though allodynia persisted, and she could not use her left hand.

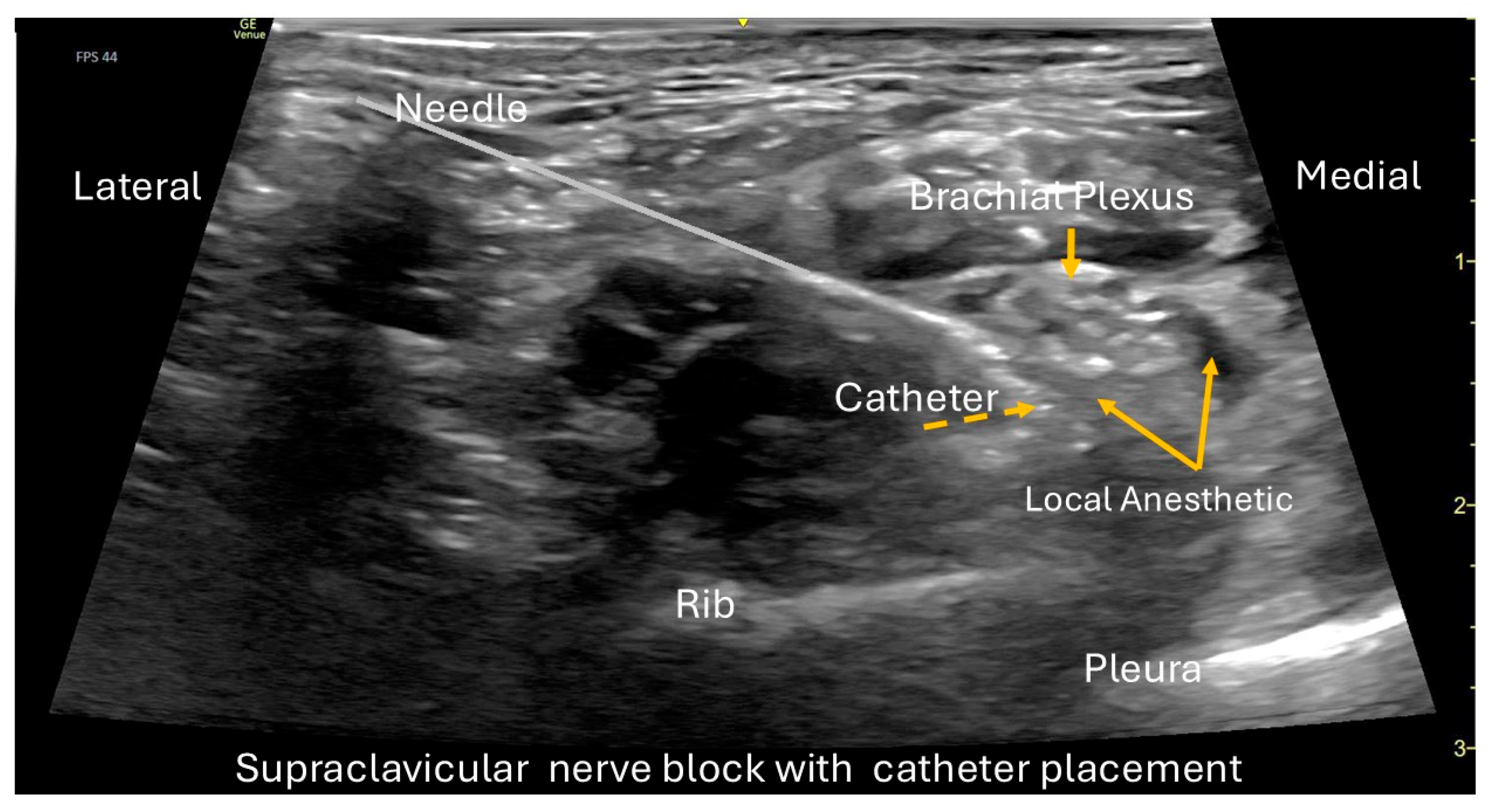

On hospital day 2, a left supraclavicular continuous peripheral nerve catheter was placed under ultrasound guidance, while the patient was sedated with ketamine, midazolam, and dexmedetomidine. The procedure was performed under full aseptic precautions and ultrasound guidance using a GE Venue Go system with a high-frequency linear transducer (L4-20t, GE XDclear) to optimize visualization of the brachial plexus cluster in the supraclavicular fossa (

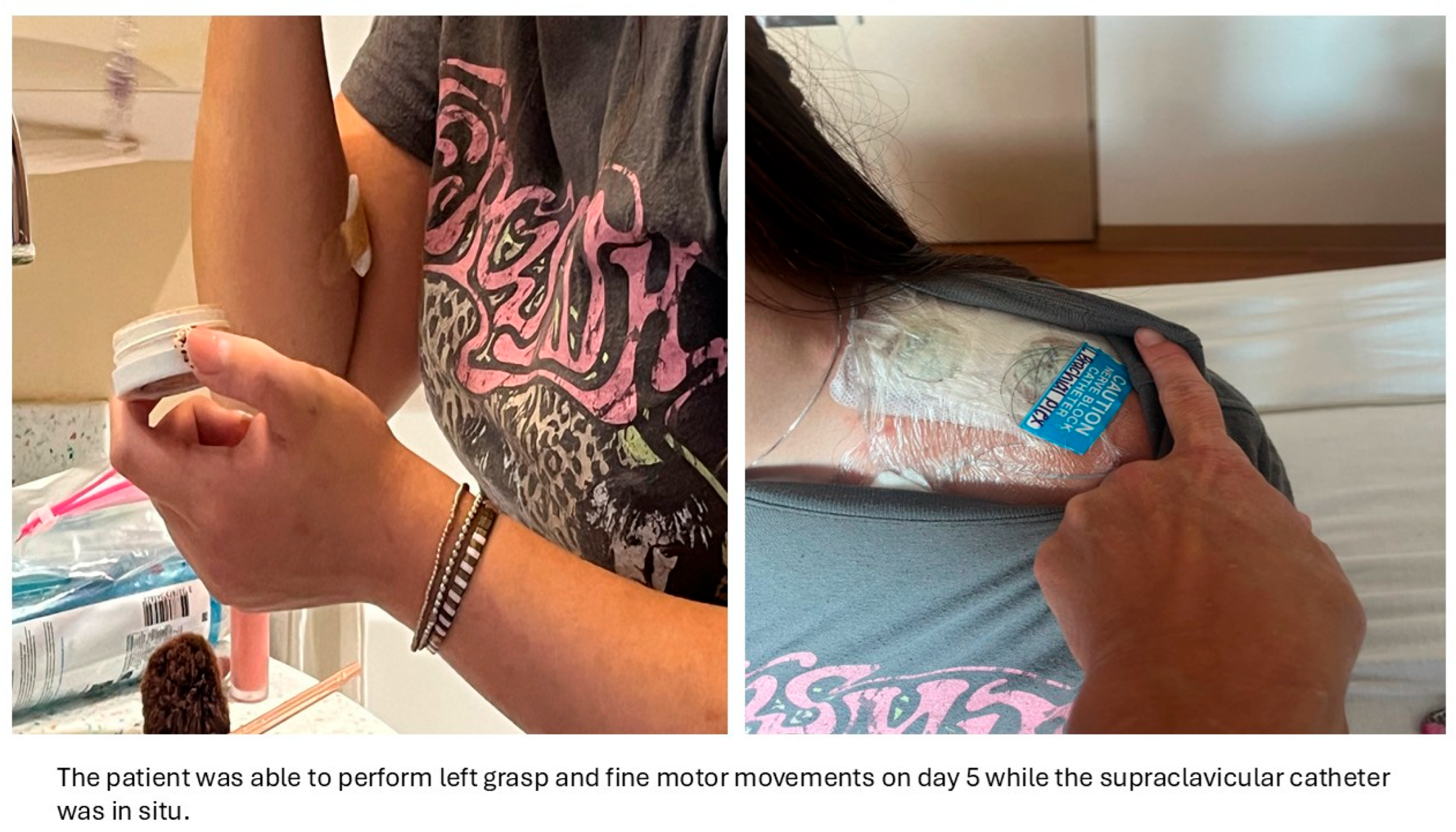

Figure 1). After standard sterile preparation and local skin infiltration, an 18-gauge Tuohy-type echogenic needle (Pajunk TuohySono, 18 G × 50 mm) was advanced in-plane from lateral to medial toward the plexus while real-time imaging confirmed correct needle position. After negative aspiration, 1–2 mL of normal saline was injected to confirm perineural spread and to hydro-dissect the plane. A bolus of 0.5% ropivacaine (20 mL) was then administered incrementally, with careful aspiration between aliquots. A 20-gauge flexible catheter (polyamide epidural style catheter, Perifix/B. Braun 20 Ga thread assist guide) was threaded approximately 3 cm beyond the needle tip and confirmed in the correct location. The catheter was tunneled subcutaneously to reduce dislodgement and secured with two chlorhexidine biopatches and a sterile occlusive dressing (

Figure 2). Shortly after the placement, the patient experienced complete motor and sensory block in the brachial plexus distribution. Continuous infusion of ropivacaine 0.2% was initiated on the floor at 7 mL/hour with automated 3 mL boluses every 4 hours. The catheter placement was uncomplicated, except for a mild, transient Horner-type effect that resolved on the first day after placement.

Within 24 hours of catheter placement, her pain reduced to 2/10, and by 48 hours it was 0/10 at rest. The hand was warm, well-perfused, and could move freely without discomfort. She reported appropriate analgesia. The patient did not require any additional medication administration, and the ketamine infusion was tapered to 3 mg per hour continuous and discontinued on POD (Post Operative Day) 4.

On hospital day 4, she began active physiotherapy, completing grasp and fine motor exercises without recurrence of pain. The continuous block remained effective, and she tolerated oral intake and ambulation normally.

| Hospital/follow-up Day |

Pain Score (0–10) |

Ketamine Infusion (mg/hr) |

Ropivacaine Infusion (mL/hr) |

Functional Milestones/Clinical Notes |

| Admission (Day 1) |

7 |

7 mg/hr continuous + 3 mg bolus every 15 min |

– |

Severe pain, allodynia, limited movement |

| Post-block (Day 2) |

2 |

7 mg/hr |

7 mL/hr + 3 mL every 4hr bolus |

Marked relief, improved perfusion; No additional boluses of ketamine used |

| Day 3 |

0–1 |

5 mg/hr |

7 mL/hr + 3 mL every 4hr bolus |

Pain-free, began hand therapy

No additional boluses of ketamine and ropivacaine were used |

| Day 4 |

0 |

3 mg/hr |

7 mL/hr + 3 mL every 4hr bolus |

Active range of motion

No additional boluses of ketamine and ropivacaine were used |

| Discharge (Day 5) |

0 |

Discontinued |

6 mL/hr +3 ml demand every hour

ambulatory pump |

Independent activities of daily living. Discharged home |

| Day 9 (catheter removal) |

0 |

– |

– |

Catheter removed, no pain or deficit. |

| 2 weeks post-discharge |

0 |

– |

– |

Full range of motion, back to school |

| 6 weeks post-discharge |

0 |

– |

– |

Returned to sports, full recovery |

Ambulatory Phase and Follow-up

The patient was discharged on hospital day 5 with the catheter in place, connected to an ambulatory infusion pump delivering ropivacaine 0.2 percent at 6 mL per hour with optional 2 mL boluses every hour, and gabapentin 400 mg three times daily.

She went to school for the next four days and was able to resume some of her daily sports activities. The Acute Pain Service conducted daily telephone follow-up. She was pain-free and did not require any additional ropivacaine administration via the pump. She reported adequate numbness in the brachial plexus distribution, and occasionally she reported left-sided Horner syndrome. The catheter remained in place for nine days, and the family removed it at home without complications.

After catheter removal, the numbness and Horner syndrome resolved quickly. Gabapentin was continued for one week, then tapered over two weeks.

At the two-week follow-up, she was completely pain-free with normal color, temperature, and strength, and she started occupational therapy. At one month, she resumed light athletic activity and remained asymptomatic. At six weeks, she had a full return to sports and all extracurricular activities without any recurrence of symptoms. The patient and the family express high satisfaction with the pain control.

3. Discussion

This case illustrates the effective use of pharmacologic, interventional, and rehabilitative strategies to achieve rapid remission of adolescent CRPS Type I. The primary goals were adequate pain control, sympathetic modulation, and early restoration of functional hand use. Meeting these goals enabled the patient to participate fully in hand therapy, return to school, and resume light sports soon after discharge.

CRPS arises from abnormal neuroinflammatory signaling, central sensitization, and sympathetic hyperactivity, which together produce severe pain and autonomic changes disproportionate to the initial injury (1). Pediatric CRPS involves the same mechanisms but is further influenced by psychosocial factors and greater neuroplastic adaptability. (2). The primary therapeutic priority is functional restoration through pain desensitization and graded physical activity. (3).

When conservative management fails, multimodal approaches can target several pain-processing pathways. Ketamine interrupts central sensitization and cortical wind-up by blocking NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory transmission. (5).Gabapentin provides complementary analgesia by modulating calcium-channel activity and decreasing presynaptic neurotransmitter release (1). Continuous peripheral nerve block provides sustained regional analgesia and sympathetic blockade, minimizing nociceptive input and promoting desensitization. (6,7).

Although multidisciplinary rehabilitation remains the foundation of pediatric CRPS care, interventional modalities are increasingly important for refractory cases. (2,8). Intensive inpatient rehabilitation has been associated with significant functional improvement, but some patients require additional pain-modulating interventions. (8). Current literature supports the safe use of prolonged peripheral nerve catheters in children when proper monitoring is in place (6,7).

In this case, the combination of systemic (ketamine, gabapentin) and regional (supraclavicular nerve block) therapies provided rapid pain relief, enabling early mobilization and facilitating a faster functional reintegration. Similar multimodal strategies in the literature have shown accelerated recovery when pain control allows active participation in physical and occupational therapy. These findings support considering multimodal desensitization as an early adjunct rather than a last-line intervention in refractory CRPS (5,8,9).

Mosquera-Moscoso and colleagues recently reviewed pediatric interventional pain strategies, reporting that ketamine infusions and continuous peripheral nerve catheters are promising adjuncts for CRPS unresponsive to standard therapy. Subanesthetic ketamine use in adolescents has shown favorable analgesic effects with minimal psychomimetic or cardiovascular adverse events when administered with appropriate monitoring (5).

The combined use of systemic and regional techniques may offer synergistic desensitization: ketamine and gabapentin reduce central excitatory signaling, while regional blockade interrupts peripheral nociceptive input, facilitating cortical reorganization and restoration of normal sensorimotor function(10).

Limitations and Future Directions

This single-patient report cannot establish causal relationships or determine optimal dosing. Pediatric CRPS may remit spontaneously, and controlled data in this population remain limited. Even so, the temporal association between the targeted multimodal interventions and the patient’s complete remission suggests a plausible mechanistic benefit.

Future research should focus on establishing prospective pediatric CRPS registries and developing standardized protocols that integrate pharmacologic and interventional treatments. Defining the optimal duration of continuous nerve blocks, ketamine dosing regimens, and long-term functional outcomes would strengthen evidence for broader clinical application.

4. Conclusions

A coordinated multimodal regimen using subanesthetic ketamine infusion, gabapentin, and a prolonged supraclavicular continuous nerve catheter resulted in rapid and sustained remission of refractory adolescent CRPS Type I. Integrating central and peripheral desensitization strategies can facilitate early rehabilitation and support durable functional recovery.

Early, aggressive, and coordinated intervention between surgeons, anesthesiologists, rehabilitation specialists, and pediatric pain services can prevent chronic disability and help children regain independence and quality of life. This case illustrates the effectiveness of well-planned multimodal therapy in safely reducing disease duration and optimizing long-term functional outcomes in pediatric CRPS, thereby adding to the growing evidence supporting multimodal interventional strategies in pediatric CRPS.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5 for grammar correction. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. and M.V.; methodology, H.M, and M.V.; software, H.M and M.V.; validation, H.M., M.V. and A.D; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, M.V and A.D.; resources, M.V; data curation, M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M and M.V.; writing—review and editing, H.M, M.V and A.D.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, M.V.; project administration, H.M and M.V.; funding acquisition, M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient and parent to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Low AK, Ward K, Wines AP. Pediatric complex regional pain syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(5):567–72.

- Weissmann R, Uziel Y. Pediatric complex regional pain syndrome: a review. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2016 Dec;14(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Sherry DD, Wallace CA, Kelley C, Kidder M, Sapp L. Short-and long-term outcomes of children with complex regional pain syndrome type I treated with exercise therapy. Clin J Pain. 1999;15(3):218–23. [CrossRef]

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, Wilson PR. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):326–31. [CrossRef]

- Sheehy KA, Muller EA, Lippold C, Nouraie M, Finkel JC, Quezado ZMN. Subanesthetic ketamine infusions for the treatment of children and adolescents with chronic pain: a longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr. 2015 Dec;15(1):198. [CrossRef]

- Visoiu M, Joy LN, Grudziak JS, Chelly JE. The effectiveness of ambulatory continuous peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative pain management in children and adolescents. Lonnqvist P, editor. Pediatr Anesth. 2014 Nov;24(11):1141–8. [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia N, Praslick A, Visoiu M. Safety assessment of prolonged nerve catheters in pediatric trauma patients: a case series study. Children. 2024;11(2):251. [CrossRef]

- Brooke V, Janselewitz S. Outcomes of children with complex regional pain syndrome after intensive inpatient rehabilitation. PM&R. 2012;4(5):349–54. [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Moscoso J, Eldrige J, Encalada S, de Mendonca LFP, Hallo-Carrasco A, Shan A, et al. Interventional pain management of CRPS in the pediatric population: A literature review. Interv Pain Med. 2024;3(4):100532. [CrossRef]

- Mesaroli G, Hundert A, Birnie KA, Campbell F, Stinson J. Screening and diagnostic tools for complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic review. Pain. 2021;162(5):1295–304. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).