1. Introduction

Federated learning (FL), as defined by 3GPP [

1] and IEEE [

2,

3], represents an innovative paradigm in machine learning that addresses the challenges of decentralized data environments [

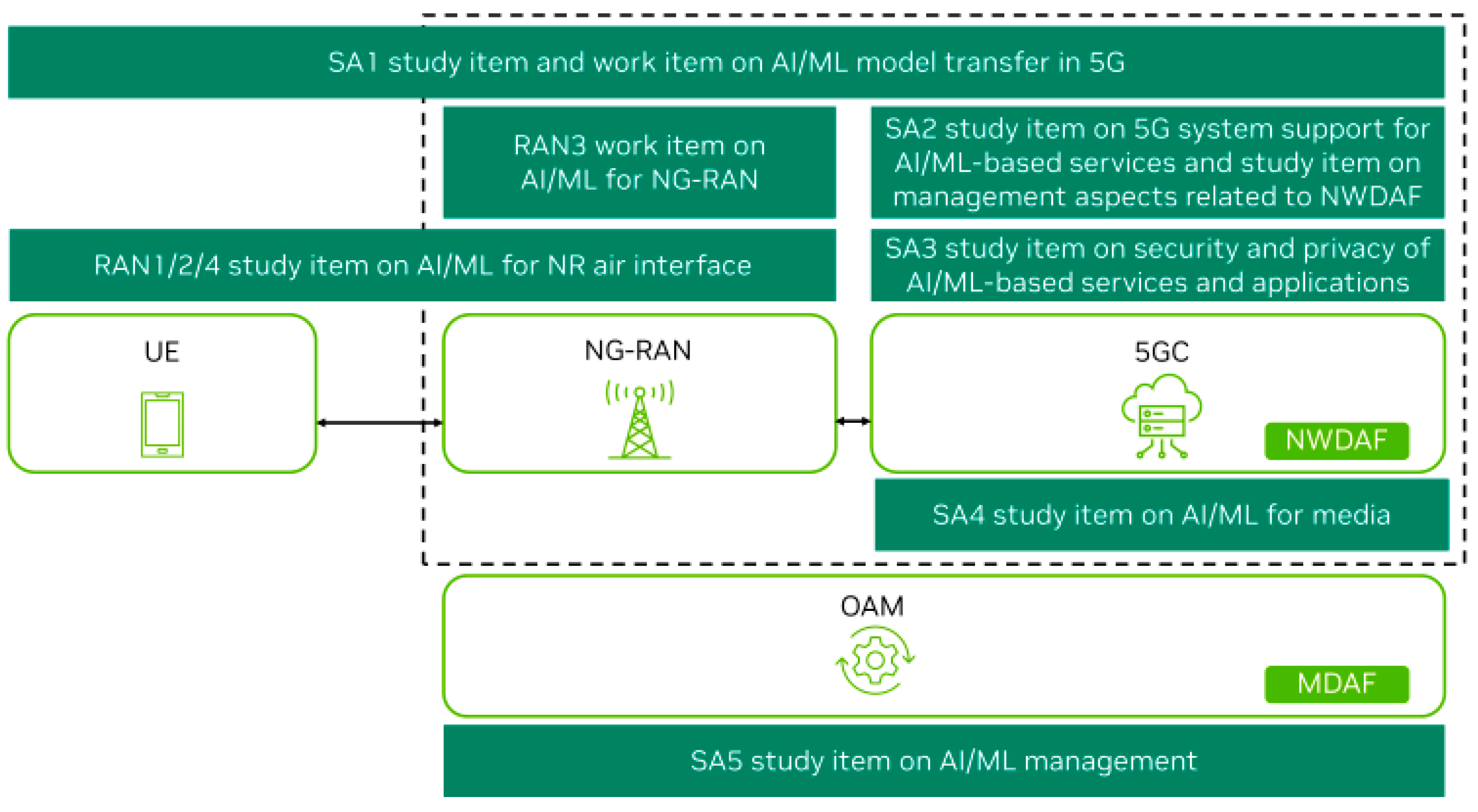

4]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the 3GPP framework has reached a significant milestone, with ongoing research and specifications aimed at enhancing data utilization and predictive capabilities expected to be featured in Release 19 and Release 20. This development underscores the organization’s commitment to leveraging advanced analytical techniques to improve telecommunications standards. Within this context, both the Technical Specification Group for Radio Access Networks (TSG RAN) and the Technical Specification Group for Service and System Aspects (TSG SA) have outlined specific requirements to incorporate AI alongside its companion, machine learning (ML).

Notably, Working Group RAN3 has finalized Technical Report 37.817, which investigates enhancements for data collection relating to New Radio (NR) and Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access (ENDC). This report highlights three primary use cases where AI and ML can provide meaningful solutions in the Network Energy Savings, addressing strategies such as traffic offloading, modifications to coverage, and cell deactivation to reduce energy consumption. Moreover Load Balancing supports the Implementation techniques to optimize load distribution across cells or groups of cells in multi-frequency and multi-radio access technology (RAT) environments, thereby improving overall network performance based on predictive analytics. Finally for the Mobility Optimization, ensuring robust network performance during user equipment (UE) mobility events by selecting optimal mobility targets grounded in predictive assessments of service delivery. These focal points illustrate a strategic approach to evolving network management through intelligent data-driven decision-making.

The Federated Learning architecture will be supported by the NWDAF in the crucial 3GPP standard method [

5]. It efficiently collects data from user equipment, network functions, operations, administration, and maintenance (OAM) systems within the 5G Core, Cloud, and Edge networks. This wealth of data is then utilized for powerful 5G analytics, enabling better insights and actions to enhance the overall end-user experience. In any case the FEELL shall comply with the existing NWDAF framework and 5GS framework as specified in [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) over NWDAF have become pivotal technologies driving advancements in wireless communication networks. These cutting-edge tools offer innovative solutions to enhance the efficiency, scalability, and performance of modern network infrastructures. Recognizing their potential, the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) has integrated AI/ML technologies into the Radio Access Network (RAN) as part of Release 18, marking the beginning of 5G-Advanced [

10]. This milestone represents a significant step forward in optimizing network capabilities to accommodate the rapid proliferation of massive Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices and the exponential growth in data traffic. The inclusion of AI/ML in Release 18 underscores its importance in advancing the capabilities of 5G networks. These technologies play a central role in enabling intelligent resource allocation, optimizing network performance, and addressing the unique challenges posed by increasing IoT connectivity. By leveraging NWDAF AI/ML, 5G-Advanced aims to deliver superior reliability, efficiency, and adaptability to meet the evolving demands of modern communication systems.

The Management Data Analytics Function (MDAF) serves as a fundamental component for enabling network automation and intelligence by processing data on network conditions and service events to generate detailed analytics reports. This function utilizes input data from various network functions (e.g., NWDAF) and entities (e.g., 6G gNB or 5G gNB). MDAF deployment is versatile, operating at different levels such as the domain level—targeting specific areas like the Radio Access Network (RAN) or core network—and in a centralized configuration to deliver comprehensive, end-to-end or cross-domain analytics [

11]. Efforts within 3GPP to integrate AI/ML and advanced data analytics into 5G system design, prior to Release 18, have established a robust framework for further development in 5G-Advanced. Release 18 incorporates an extensive range of studies and work items related to AI/ML, involving contributions across multiple 3GPP working groups, thereby paving the way for enhanced capabilities in network optimization and intelligence, as indicated in

Figure 1 [

11].

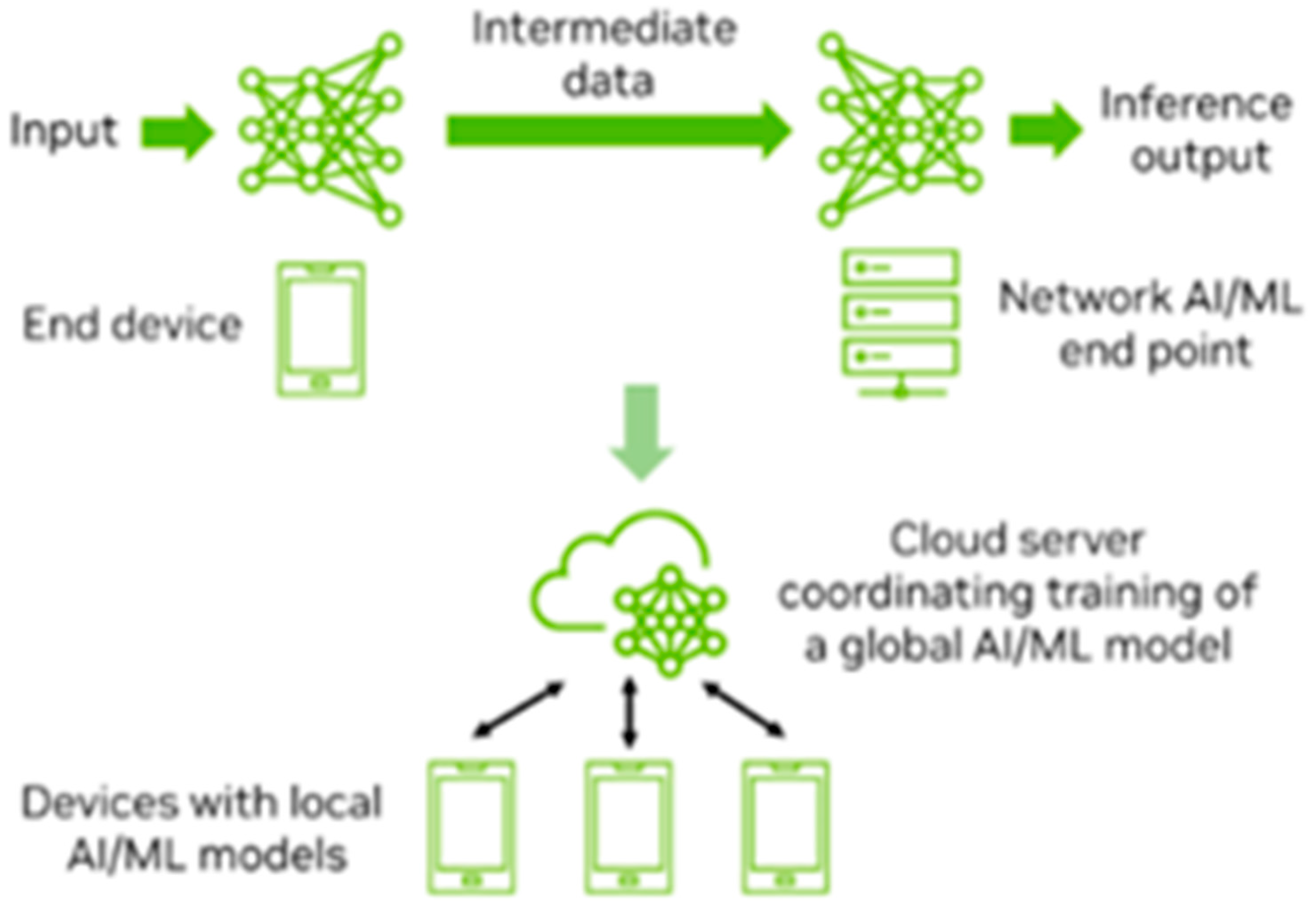

AI and ML technologies play a crucial role in mobile devices within the 5G ecosystem, supporting functionalities such as image recognition, speech processing, and video analysis. However, preloading all possible AI/ML models onto user equipment (UE) is impractical. As a result, models often need to be downloaded dynamically based on specific requirements. Additionally, some UEs may lack the computational resources needed to perform inference operations locally, necessitating the offloading of these tasks to the 5G cloud or edge infrastructure. Furthermore, collaborative training of global AI/ML models across multiple entities in the 5G framework requires efficient mechanisms for sharing training data. The growing demand for transferring AI/ML models and data introduces a new category of network traffic that 5G systems must accommodate. The 3GPP SA1 group, tasked with defining service and performance requirements for 3GPP systems, initiated a study in Release 18 to explore use cases and establish the requirements for AI/ML model transfers [

12]. This study identified three key types of AI/ML operations, as shown in

Figure 2 [

11].

The first type, AI/ML Operation Splitting, involves dividing tasks between endpoints. Privacy-sensitive or latency-critical components of operations are retained within the UE, while computationally intensive tasks are offloaded to network endpoints. The second type, Model and Data Distribution, focuses on enabling adaptive downloading of models from network endpoints to UEs as needed. The third type, Distributed or Federated Learning, allows UEs to perform partial training on local datasets, with a central entity aggregating these results to form a unified global model [

13]. The study identified potential service requirements and performance metrics, including those related to training, inference, distribution, monitoring, prediction, and management of AI/ML models within the 5G ecosystem. Following this initial exploration, 3GPP SA1 launched a subsequent work item in Release 18 to define normative service and performance requirements, building on the findings of the study to address the evolving demands of AI/ML integration in 5G systems [

13]. Moreover the 3GPP [

14] study aims to lay the groundwork for leveraging AI/ML to enhance the air interface, addressing multiple critical dimensions. Key areas of focus include defining the stages of AI/ML algorithm deployment, determining the degree of collaboration required between the gNB and UE, identifying the datasets necessary for training, validating, and testing AI/ML models, and managing the entire life cycle of these models. These efforts are essential for ensuring that AI/ML technologies can be effectively integrated into current and future network architectures, setting the stage for 6G.

Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that rely on centrally aggregated data, FEEL enables multiple entities, often referred to as clients, to collaboratively train a shared model while ensuring their data remains localized. This approach is particularly significant in scenarios where data privacy, security, and regulatory compliance are critical concerns, such as in the telecommunications sector. The distinguishing characteristic of FEEL lies in its approach to data heterogeneity. In decentralized settings, data samples across clients are not guaranteed to be independently and identically distributed (non-IID). This stands in contrast to centralized models, where uniform data distribution is often assumed. This inherent heterogeneity of FEEL systems poses unique challenges and necessitates tailored algorithms to ensure effective learning across diverse data distributions. A key motivation for federated learning is its potential to address data minimization and optimization challenges, especially in fields where data privacy, bandwidth efficiency and throughput optimization are critical. By training models locally on client devices or nodes and sharing only model parameters—such as weights and biases—FEEL minimizes the need for raw data exchange [

15]. This not only reduces privacy risks but also mitigates bandwidth constraints, making it an appealing solution for large-scale, distributed systems like telecommunications networks.

At the core of the FEEL paradigm is a collaborative training process that iteratively combines local computations into a global model. Each client trains a model on its local data and periodically transmits the updated parameters to a central aggregator. The aggregator then consolidates these updates to refine the global model, which is subsequently shared back with the clients. This iterative process continues until the model achieves a predefined level of performance, with good potential examples in 6G networks [

16]. The potential of FEEL extends far beyond data privacy. It aligns seamlessly with the growing emphasis on distributed computing and edge intelligence in modern network architectures. For example, in telecommunication networks, FEEL can facilitate real-time optimization of network resources, enhance service delivery, and drive innovation in predictive maintenance and user behavior analytics [

17]. However, implementing FEEL in practice introduces several challenges, including communication overhead, computational constraints at edge devices, and the need for robust algorithms to handle non-IID data. Addressing these challenges requires interdisciplinary efforts that span machine learning, distributed computing, and network optimization [

18].

Recent advances in FEEL have explored techniques to improve communication efficiency, such as model compression and adaptive update mechanisms. Additionally, privacy-preserving technologies, including secure aggregation and differential privacy, are increasingly being integrated into FEEL frameworks to ensure that sensitive information remains protected throughout the training process [

19]. In 6G networks and in mobile communications, FEEL holds promise for transforming network management and optimization. By leveraging localized data at various network nodes, operators can enhance coverage, capacity, and user experience while adhering to stringent privacy regulations. Furthermore, FEEL aligns with the broader trend toward 6G networks, which emphasize edge intelligence, data efficiency, and distributed learning [

20]. The significance of FEEL is underscored by its applicability across a diverse range of domains, including healthcare, finance, and industrial automation. In healthcare, for instance, FEEL enables collaborative training of diagnostic models across hospitals without exposing sensitive patient data. Similarly, in finance, it allows institutions to develop fraud detection models without sharing proprietary transaction data.

A number of different algorithms for federated optimization have been proposed. Deep learning training often utilizes variations of Federated stochastic gradient descent (FedSGD), where gradients are computed on a randomly selected portion of the dataset and then used to update the model through a single step of gradient descent. In a federated learning context, FedSGD adapts this process by distributing the computation across multiple nodes. A random fraction

C of the available nodes is selected, and each node uses its entire local dataset to calculate gradients. These gradients are then aggregated by a central server, weighted according to the number of training samples on each node, building then combined gradients which are subsequently applied to update the global model through a single gradient descent step [

21].

Another algorithm is the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) which builds upon the concept of Federated Stochastic Gradient Descent (FedSGD) by enabling local nodes to conduct multiple updates on their respective local datasets before sharing their parameters with the central server. Unlike FedSGD, where the exchanged information consists of gradients calculated after a single update, FedAvg aggregates the locally updated model weights directly [

22]. The fundamental insight underpinning this approach is that, when local models originate from identical initial conditions, averaging their gradients in FedSGD is mathematically analogous to averaging the model weights. However, FedAvg goes further by leveraging the averaged weights from locally tuned models, a process that maintains—if not enhances—the performance of the aggregated global model. This enhancement arises because the averaging process effectively captures the learning progress made by each node, even when working with heterogeneous local data distributions. This paradigm shift in federated optimization aligns with findings in distributed machine learning research, where locally adjusted weights retain key features learned during training. Notably, studies highlight that the use of FedAvg often leads to faster convergence and reduced communication overhead compared to FedSGD, making it a preferred method in many real-world federated learning scenarios.

Federated Learning with Dynamic Regularization (FedDyn) addresses a critical challenge in federated learning—handling heterogeneous data distributions across devices. When device datasets are non-identically distributed, minimizing individual device loss functions does not necessarily align with minimizing the overarching global loss function. Recognizing this issue, a new algorithm was introduced to mitigate the adverse effects of data heterogeneity [

23]. FedDyn introduces a dynamic regularization mechanism to adjust each device’s local loss function, ensuring that the aggregated modifications contribute effectively to the global loss minimization. By aligning local losses with the global objective, FedDyn becomes robust to varying degrees of heterogeneity, enabling devices to perform full optimization locally without sacrificing overall model convergence. Theoretical analysis confirms that FedDyn achieves convergence to a stationary point for non-convex loss functions, regardless of the heterogeneity level. These theoretical guarantees are supported by extensive experimental evaluations across diverse datasets, demonstrating its efficacy and reliability.

Dynamic Aggregation Using Inverse Distance Weighting (IDA) is an innovative adaptive technique designed to address challenges associated with unbalanced and non-independent identically distributed (non-iid) data in federated learning environments. This method assigns weights to clients dynamically based on meta-information, with a focus on improving both the robustness and efficiency of model aggregation [

24]. The key principle of IDA lies in leveraging the distance between model parameters. By using this distance as a weighting factor, the method reduces the influence of outlier models, which can arise due to significant data distribution differences or irregular client behavior. This strategy not only mitigates the negative impact of outliers but also enhances the global model’s convergence speed by ensuring that updates from more representative or reliable clients carry greater significance in the aggregation process. Extensive studies in the field of federated learning underscore the importance of such dynamic aggregation methods, especially when dealing with real-world datasets characterized by heterogeneity and imbalances. By prioritizing model updates that are closer in parameter space, IDA aligns closely with the global optimization objective, effectively addressing the divergence issues often observed in federated systems. The integration of IDA into federated frameworks demonstrates promising results, as evidenced by improved model accuracy and faster convergence rates across various experimental setups. This method represents a significant step toward more adaptive and resilient federated learning systems, where the quality and relevance of client contributions are dynamically optimized.

Combining the Federated Learning approach with the aid of optimization algorithms has been also studied in the international literature. The study in [

25] addresses a federated learning (FL) scenario operating over wireless channels, explicitly considering coding rates and packet transmission errors. The communication channels are modeled as packet erasure channels (PEC), where the probability of packet erasure is influenced by factors such as block length, coding rate, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). To mitigate the adverse effects of packet erasure on FL performance, two optimization strategies are introduced: the central node (CN) either utilizes past local updates or reverts to previous global parameters in instances of packet loss. The mathematical analysis explores the relationship between coding rates and FL convergence under both short-packet and long-packet communication regimes with transmission errors. Simulation results demonstrate that even incorporating minimal memory at the CN—such as retaining one prior update—significantly enhances FL performance in the presence of transmission errors.

The following study [

26] addresses the critical challenge of unreliable communication in decentralized federated learning by introducing the Soft-DSGD algorithm. Unlike traditional federated learning approaches, which depend on a central node for parameter aggregation, decentralized methods allow devices to exchange model updates directly. However, existing frameworks for decentralized learning often assume idealized conditions with perfect communication among devices. In such scenarios, devices are expected to reliably exchange information, such as gradients or model parameters, without any loss or error. Unfortunately, real-world communication networks are rarely this reliable, as they are susceptible to issues like packet loss and transmission errors. Thus ensuring communication reliability often comes at a significant cost. The most common solution involves using robust transport layer protocols such as Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). While TCP ensures reliable data transmission, it introduces substantial communication overhead, which can degrade the efficiency of the decentralized learning process. Furthermore, TCP reduces the overall network connectivity, as the stringent requirements for reliable communication can limit the number of participating devices. To address these challenges, this study [

26] proposes a robust decentralized stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm, referred to as Soft-DSGD. Unlike conventional approaches, Soft-DSGD is designed to operate effectively over lightweight and unreliable communication protocols, such as the User Datagram Protocol (UDP). UDP is a connectionless protocol that provides faster and more flexible communication but does not guarantee reliable packet delivery. This protocol is particularly well-suited for decentralized learning in scenarios where communication efficiency and low latency are critical. By leveraging lightweight protocols like UDP and adopting innovative techniques to handle partial messages, Soft-DSGD offers a practical solution for training machine learning models in decentralized environments. Its ability to maintain robust performance under realistic conditions positions it as a valuable tool for advancing federated learning in the era of edge computing and Internet-of-Things (IoT) applications.

In [

27] the authors presented a robust solution for decentralized learning in dynamic and unreliable wireless environments. The proposed approach is specifically tailored for decentralized learning in wireless networks characterized by random, time-varying communication topologies. In these networks, participating devices may experience communication impairments, and some devices can become stragglers—failing to meet computational or communication demands—at any point during the training process. To mitigate the impact of these challenges, the algorithm incorporates a novel consensus strategy. This strategy leverages time-varying mixing matrices that dynamically adjust based on the instantaneous state of the network. By adapting to the current network topology, the algorithm ensures robust communication and improves the overall efficiency of the learning process. By addressing the limitations of prior frameworks, the asynchronous DSGD algorithm enables efficient and reliable collaborative training, paving the way for scalable decentralized learning applications in real-world wireless networks.

Our paper work is motivated by the observation that retransmission mechanisms are nowadays integral to many modern wireless communication standards, such as 3GPP 5G-Advanced gNBs and IEEE WiFi. However while extensively explored in traditional communication systems, the application of HARQ retransmission in distributed learning remains relatively under-researched. Indeed the paper work in [

28] presents a statistical quality-of-service (QoS) analysis for a block-fading device-to-device (D2D) communication link within a multi-tier cellular network, comprising a macro base station (BSMC) and a micro base station (BSmC), both operating in full-duplex (FD) mode. Effective capacity (EC) is computed for the D2D link, assuming no channel state information (CSI) at the transmitting D2D node, which operates at a fixed transmission rate and power. The communication link is modeled as a six-state Markov system under both overlay and underlay configurations. To enhance throughput, the study incorporates Hybrid Automatic Repeat Request (HARQ) and truncated HARQ schemes, along with two queue models based on responses to decoding failures. Simulation results reveal superior self-interference cancellation at BSmC and BSMC in FD mode enhances EC. However there is not any similar analysis in federated learning 6G networks with multiple collaborative devices.

In [

29] it is lately explored the rapid expansion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML)-driven applications with all related challenges into the growing adoption of distributed intelligence solutions to leverage the computational capabilities of cloud infrastructure, edge nodes, and end-devices for enhancing the overall processing power, meet diverse application demands, and optimize system performance. This paper delves into the complex distributed intelligence landscape, critically analyzing key research advancements in the field, however the MAC layer 2 importance of HARQ retransmissions is not fully exploited. Moreover a semantic-aware HARQ (SemHARQ) framework for robust and efficient transmission of semantic features is introduced in [

30]. A multi-task semantic encoder enhances semantic coding robustness, while a feature importance ranking (FIR) method prioritizes critical feature delivery under constrained channel resources. Additionally, a novel feature distortion evaluation (FDE) network detects transmission errors and supports an efficient HARQ scheme by retransmitting corrupted features with incremental updates, however the important MAC HARQ retransmissions for cooperative federated learning devices is not mentioned and studied.

The closest HARQ analysis for Federated Learning is in paper [

31] introducing a Federated Edge Learning (FEEL) framework designed to address the challenges posed by unreliable wireless channels, where gradients from local devices are divided into packets and subject to packet error rates (PER). Unreliable transmissions introduce bias between the actual and theoretical global gradients, adversely affecting model training. A mathematical analysis evaluates the impact of PER on convergence rates and communication costs and a an optimized device retransmission selection scheme is proposed, based on a classical convex optimization obtained solution through the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) condition, balancing convergence performance with communication overhead. The paper derives the optimal retransmission strategy to enhance model training efficiency and provides an analysis of its effectiveness. Additionally, a signaling protocol is developed to support the proposed retransmission scheme, ensuring robust and efficient model training under imperfect communication conditions.

The motivation of our paper work is to examine the implications of retransmission strategies on distributed learning, focusing on balancing the dual objectives of reliability (throughput) and timeliness to optimize performance in diverse communication environments. Our paper study emphasizes on the challenges of the unreliable wireless channels, considering the impact the timeliness of data transmission as per [

31], but improving the analysis including the eventual throughput. In certain scenarios, prioritizing timeliness over reliability might be a desirable trade-off. To optimize the performance of Federated Learning over unreliable faded wireless channels, we are in preference of the paper in [

32] where a well-known solution to large-scale machine learning problems in D2D topologies with ideal communication, the Decentralized Stochastic Gradient Descent (DSGD), is applied guaranteeing the convergence to optimality under assumptions of convexity and connectivity. To our opinion the DSGD algorithm is a superior alternative to the classical convex optimization approach using KKT for large-scale federated learning (FEEL) under fading wireless channels. While KKT-based solutions provide an elegant framework for finding optimal solutions in convex problems, their reliance on centralized computation and global knowledge of constraints limits their applicability in large-scale decentralized environments like FEEL. In such systems, the dynamic and distributed nature of data across devices, combined with the unpredictability of fading wireless channels, poses significant challenges to centralized KKT-based methods. DSGD excels in these environments since it enables local updates at individual devices, which are then aggregated through peer-to-peer communication. This reduces the need for centralized control, making DSGD scalable to large networks with many devices. Furthermore, DSGD is robust to communication impairments caused by fading channels, as it can operate effectively with partial or asynchronous updates, mitigating the impact of packet loss or delays that often hinder KKT-based approaches. Finally KKT-based solutions typically involve solving complex optimization problems that require significant computational resources and are sensitive to changes in network conditions. DSGD, on the other hand, employs stochastic updates, allowing devices to compute gradients on smaller data subsets, significantly reducing computation and energy requirements. This makes DSGD particularly well-suited for resource-constrained devices in FEEL settings, where the iterative nature of DSGD ensures gradual convergence even in non-ideal conditions. The algorithm dynamically adapts to variations in wireless channel conditions by integrating local updates and employing mixing matrices or weights that account for communication reliability. This adaptability is critical for maintaining performance in environments with time-varying channel quality, where centralized KKT-based methods struggle to maintain consistency.

Optimizing Hybrid Automatic Repeat Request (HARQ) retransmissions under the constraints of unreliable wireless channels with fading conditions presents a significant challenge due to the dynamic nature of the environment and the processing load required. The constraints and variables involved in the optimization process change more rapidly than the feedback mechanism can provide updates. In the context of 6G networks, the federated learning (FEEL) paradigm, which involves a large number of devices collaborating in a decentralized manner, adds further complexity to this optimization task. Traditional global optimization techniques have focused on finding the global minimum or maximum of a function, even when its analytical expression is unavailable but can be evaluated. However such evaluations are often computationally expensive, particularly in the context of wireless networks with critical real-time processing.

A promising development in this domain is the adoption of techniques based on general radial basis functions (RBF) which demonstrate significant potential in tackling global optimization problems, especially for partially known or difficult-to-evaluate functions [

33]. In mathematics a radial basis function (RBF) is a real-valued function φ whose value depends only on the distance between the input and any desired or predefined fixed point c. The strength of RBFs lies in their ability to approximate complex functions effectively, providing a practical way to navigate optimization landscapes where explicit mathematical formulations are infeasible. In the specific context of 6G networks, RBFs have facilitated advancements in federated edge computing and learning [

34]. These methods enable efficient optimization by leveraging the decentralized nature of federated learning, distributing the computational load across edge devices while accounting for the unreliability of wireless channels. By approximating the cost and utility functions with RBFs, it becomes possible to make near-optimal decisions in real-time, despite the rapidly changing network conditions [

35].

The radial basis function (RBF) approach offers distinct advantages over the Decentralized Stochastic Gradient Descent (DSGD) algorithm for global optimization of HARQ retransmissions in large-scale federated learning (FEEL) under fading wireless channels. Unlike DSGD, which is iterative and dependent on stochastic updates, RBF methods construct surrogate models that approximate the underlying cost function. This allows RBF to evaluate complex, partially known functions with fewer iterations, making it more computationally efficient for resource-constrained FEEL scenarios. Another key advantage is the ability of RBF to adapt to limited and noisy feedback from the network, reducing dependency on gradient information that may be unreliable in fading wireless environments. While DSGD relies on consistent communication among devices for gradient updates, RBF can operate effectively with sparse or incomplete data, leveraging its interpolation capabilities. This flexibility makes them particularly suitable for HARQ retransmissions in federated learning scenarios, where the communication and computation interplay is demanding careful consideration.

To our knowledge there exists not any recent study to address the challenge the HARQ retransmissions minimizing retransmission delays while maximizing data reliability in 5G or 6G networks using RBF global optimization approach. Our paper work scope is to take an optimal global decision in HARQ retransmission scenarios by selecting the values of specific variables that yield the most desirable outcomes. By enabling adaptive decision-making and reducing processing overhead, HARQ retransmissions provide a robust framework for addressing the complexities of 6G networks and FEEL environments. Ultimately, this approach represents a significant step forward in achieving efficient and scalable optimization for HARQ retransmissions under challenging wireless channel conditions

2. The Cross Layer Optimization Model

Modern 5G and potential 6G services operate exclusively on IP-based technology. In this framework, IP service packets are segmented at the RLC/MAC layer into smaller MAC segments (transport blocks, Trblk), which are then allocated to scheduling blocks (SBs) for transmission over the air interface resources. Each MAC Trblk packet must be fully transmitted across the air interface before the next packet can begin transmission, adhering to a Transmission Time Interval (TTI) duration depending on the sub-carrier spacing. On the uplink, multiple MAC packets are queued at device (i.e. User Equipment (UE)) transmitter, awaiting scheduling and mapping onto SBs. Upon reaching the edge server receiver, these packets are acknowledged via a downlink transmission.

Following the analysis in [

31] a federated edge computing learning system is considered with one edge server (i.e. a 6G node) and K connected devices where each of k device stores

data for transmission and the total number of data in the entire edge server system can be represented as

. The uploaded data rate for each of the k device in the federated edge learning system during the training period τ is defined as following

or:

where

, is the transmitted UL power of device k,

is the channel power gain between the device and the edge server, and N

0 is the noise power over the whole bandwidth B. Consequently

≈R

k/τ assuming negligible overhead bits during transmission.

In the context of our mathematical analysis, we consider IP packets that are segmented at the upper layers and processed at the MAC layer. The MAC scheduler acts as a single edge server, distributing in the downlink and receiving in the uplink packets across multiple resources. These resources, termed channels in our model, correspond to the scheduling blocks (SBs). For simplicity, the analysis assumes m parallel channels in the queue model. The IP packet Trblk fragments are stored in a finite-length queue before scheduling. The queue is considered empty when there are n < m packets in the system, and the number of occupied resources is less than the maximum m channels available on the air interface, otherwise, any additional IP MAC Trblk fragments are held in the queue. The arrival of IP packets for both uplink and downlink follows a Poisson distribution with an average overall arrival service dependent input rate (intensities)(IP packets/sec). Due to the PDCP, RLC and MAC protocols the IP packets are fragmented to MAC transport block packets (trblk) and control symbols are added to each packet before the information is sent, leading into MAC trblk transmission information intensities MAC information packets/sec.

The uplink and downlink MAC trblk packet transmissions are related to the process of MAC HARQ where the base station receives an information packet and determines whether it is correctable or not. For each non-correctable information packet, the MAC sends a negative acknowledgment (NACK) report. The intensity of these NACK reports is denoted as (NACK packets/sec) while the intensity of retransmissions (retransmitted packets/sec after NACK indication) is denoted as. The intensity of positive acknowledgments sent from in the uplink or downlink path is denoted as. The MAC packet feddback is informed via a feedback link of HARQ acknowledgment packets (including the positive acknowledgments and the negative acknowledgments) with an intensity ofacknowledgment packets/sec and the intensity of correctable received MAC packets, to be forwarded to upper protocol layers, is denoted as. The overall input (uplink or downlink) MAC transmission intensities is then declared as:(packets/sec). Based in 3GPP layer 2 MAC functionality when an information packet has been retransmitted K times and still has errors, it is then forwarded to the receiving RLC/PDCP layers with the intensity .

The service time for each channel is assumed to be constant, reflecting minimal variation in transmission delays due to minor processor load fluctuations. Transit time effects are excluded from this analysis because the MAC scheduler operates continuously, ensuring a seamless scheduling process without interruptions or transit delays. This assumption allows for a simplified yet practical model of the 5G/6G MAC layer operation and its scheduling dynamics. For queue equilibrium, mathematical analysis considers always the condition that m > k.

2.1. The Average HARQ Retransmissions

Let’s define

the probability of n MAC packets in both queue and in service (scheduled) at a given time τ,

the probability that no more than n MAC packets exists in the system model at given time τ and

defines the probability that no more than zero packets exist in the queue as long as m MAC packets exist in the server at the beginning of unit of time. For a constant service time we make the assumption to consider the service time

as the typical unit of time. Then the probability

that specifically n MAC packets exist in the system at the unit of time equals [

37]:

The probability of non-existent packets in the buffer (i.e. the condition that there are n < m occupied channels over the air interface), named as non-delay probability P

0, is given by [

37]:

In 5G/6G Layer2 MAC scheduler, scheduling decisions are mostly restricted by multiple typical constraints as the QoS profile, the radio link quality (i.e. SINR) reports, BLER/HARQ retransmissions and UE uplink buffer sizes (uplink signaled to the edge server using available uplink resources and procedures) [

38,

39,

40]. Following the previous analysis a service produces IP information packets with a rate (intensity) of

(IP packets/sec). An IP information packet of

variable bits per packet and average

bits per IP packet is considered to be segmented into

average number of MAC packets per IP packet, where each MAC packet has variable length

(bits per MAC packet), containing a fixed number of

overhead bits per packet [

37]. For

overall MAC overhead, the total average MAC transmitted bits will be

and the average MAC transmission intensity (MAC packets/sec):

Wireless channels are generally considered to be unreliable implying that the uplink channel errors need to be considered for the whole uplink transmission during the AI/ML training, where each Trblk transmission has redundant CRC encoding for error detection and HARQ retransmission as per 5G/6G. Average successful packet delivery in the transmission process is expected to have retransmissions over HARQ [

38,

39,

40], contributing to an increased transmission delay. The corrupted packets in the transmission process are considered to be uncorrelated between each other. In this analysis the Code-Block Groups (CBG) of LDPC coding is not considered, leaving the analysis to a more simplistic analysis, though practical and realistic with existing vendor proprietary features based on single Code-Word transmission based on packet error rate (PER) performance. To conclude on the PER expression for device k SINR should be considered. For a single MAC Trblk packet transmission, the probability of successful delivery depends on whether the signal quality is sufficient to meet the decoding requirements, often defined by a decision threshold SINR

thr. Hence a packet is successfully decoded if the received SNR exceeds a threshold i.e., SNR

k ≥ SINR

thr. The average number of retransmissions

nmac is a function of the MAC PER. Any initial uplink MAC Trblk transmission is received successfully and decoded correctly with packet success probability

p at the first transmission interval,

p(1−

p) at the second transmission interval and so on up to ν

th maximum transmission attempt (ν is a 3GPP MAC layer parameter [

38,

39,

40]) with probability

p(1−

p)

v−1. If after the ν

th transmissions the packet is still corrupted it will be finally forwarded to the upper RLC layer with probability (1−

p)

v for further RLC ARQ functionality [

38,

39,

40] and the mean number of retransmissions can be calculated as:

Leading into (geometric series expansion):

Since

, the mean number of HARQ packet retransmissions is estimated to be [

41]:

By definition PER is the number of incorrectly received data packets divided by the total number of received packets. The expectation value of the PER for each of the device k is denoted packet error probability p

p = 1- (packet success probability) = 1 -

p. Considering our previous federated edge server model with

the transmitted UL power of device k,

the channel power gain between the device and the edge server, and N

0 the noise power over the whole bandwidth B, the successful decoding of a Trblk MAC packet depends on the SINR

thr where the packet error probability (probability of failure) p

p is then expressed as [

36]:

And the mean number of HARQ packet retransmissions is finally expressed as:

From equation (9), it is obvious that the average number of retransmissions nmac depends explicitly on the maximum number of HARQ attempts v, on the and on the size of the MAC packet . Due to 5G/6G HARQ function one MAC packet will be retransmitted a maximum number of v times under the restriction TTI < τmax ≤ (n + ν)Ts under the restriction:.

The

is estimated as:

And the intensity of HARQ packet retransmissions is given by: :

Given the previous analysis the MAC information packet, been retransmitted ν times and still has errors, which are forwarded to the receiving RLC/PDCP layers is given by the following intensity

:

The denominator is a finite geometric series with the first term and common ratio , having the sum formula:

Substituting the denominator expression into the equation (11) fraction, we get:

Moreover the intensity of correctable received MAC packets, to be forwarded to upper receiving RLC/PDCP layers, is denoted as

:

2.2. The HARQ Retransmission Gain

The implementation of Hybrid Automatic Repeat Request (HARQ) in 5G-A and emerging 6G networks marks a significant step toward improving data reliability and optimizing spectral efficiency in wireless communications. HARQ integrates forward error correction (FEC) with CBG and retransmission mechanisms to counteract packet losses, ensuring dependable data transmission even in fluctuating and complex channel environments. The iterative nature of HARQ retransmissions, especially when using incremental redundancy, enhances overall system performance by boosting throughput and reducing latency through the avoidance of redundant retransmissions. Federated Edge Learning (FEEL), as a decentralized machine learning framework, allows edge devices to collaboratively train models without exchanging raw data, thereby maintaining privacy while leveraging distributed intelligence. Integrating Federated Edge Learning (FEEL) with HARQ retransmissions offers notable advantages by optimizing a defined cost function. Firstly, FEEL algorithms can predict optimal transmission settings, such as modulation and coding schemes (MCS), using locally observed channel conditions, thereby improving HARQ performance. Secondly, FEEL supports adaptive learning across diverse devices, enabling HARQ mechanisms to dynamically adjust based on changing channel conditions and user demands. Furthermore, the synergy between HARQ and FEEL helps tackle key challenges in 5G-Advanced. FEEL-driven predictive models can anticipate retransmission-prone scenarios, allowing proactive adjustments in transmission power and resource allocation. Additionally, by distributing computational tasks across the network, FEEL reduces the processing load on central units, complementing the decentralized architecture of 5G networks. Preliminary research, incorporating insights from 3GPP Release 18 specifications and recent IEEE contributions, suggests that HARQ mechanisms enhanced by FEEL can improve spectral efficiency by up to 20% and reduce latency by approximately 15% compared to conventional methods [

42].

Combining FEEL with HARQ retransmissions presents significant opportunities for improving system performance. By integrating a cost function that balances HARQ retransmission benefits with potential latency increases, FEEL algorithms can optimize both communication and computational efficiency. Radial basis functions (RBFs) are especially effective in capturing the nonlinear relationships between retransmission performance and latency trade-offs. The fusion of HARQ and FEEL, supported by RBF-based cost functions, enables the development of resilient, low-latency, and scalable next-generation communication networks. To systematically derive the gain function for PER reduction after a single retransmission for device k, we begin with a simplified analysis. The initial PER for device k is given in equation (8). Suppose that after an initial transmission failure, the packet undergoes an average of nmac retransmissions. Throughout this process, the probability of error decreases due to enhanced redundancy in encoding or improved channel conditions. For simplicity, we assume that the effective SINR experiences a retransmission gain factor Gr >1 as a result of HARQ, contributing to improved reliability.

The SINR gain due to HARQ retransmissions in 5G/6G depends on several factors, including the number of retransmissions, channel response characteristics, and fluctuating radio link conditions. The PER improvement (gain) is defined as the the ratio of the initial packet error probability p before retransmissions to the packet error probability after retransmissions. The initial probability of failure (PER) for device k before retransmissions is given by equation (8). Each retransmission improves the effective SINR due to redundancy and potential channel variations. Define Gr as the retransmission gain factor, which accounts for the improvement in SINR after retransmissions, then the effective SINR after n

mac retransmissions becomes

, and the new packet error probability

after

retransmissions can be written as:

The HARQ process improves the SINR due to error correction mechanisms and retransmission diversity (soft combining or incremental redundancy). The retransmission intensity represents the additional attempts to successfully decode a packet. The effective SINR improvement for retransmissions can be modeled as a function of the ratio between retransmission intensity and the total transmitted packet intensity , as well as the acknowledgment intensity as:

where the factor

represents the efficiency of retransmissions in improving SINR. The improvement in PER (gain) due to retransmissions is defined as the ratio of initial to post-retransmission PER, e.g.

2.3. Transmission Latency Inflation Factor due to HARQ Retransmissions

HARQ plays a critical role in improving transmission efficiency in wireless networks by enhancing data reliability and mitigating packet losses, as described so far in the section 2.2. By leveraging error detection and correction mechanisms, HARQ dynamically retransmits erroneous packets, ensuring successful data delivery even under adverse channel conditions. This results in improved spectral efficiency, reduced packet loss rates, and enhanced overall network performance. The combination of Forward Error Correction (FEC) and retransmission strategies, such as soft combining and incremental redundancy, further optimizes link adaptation, leading to higher throughput and reduced retransmission overhead.

However, while HARQ improves transmission reliability, it introduces additional transmission latency due to repeated packet retransmissions. Each retransmission incurs a round-trip time (RTT) delay, which accumulates as the number of retransmissions increases. This delay is particularly critical in ultra-low latency applications, such as real-time communications and autonomous systems, where even small delays can impact performance. Furthermore, higher retransmission intensities increase network congestion, leading to additional queuing delays and resource contention. Thus, while HARQ enhances network efficiency by improving packet delivery success rates, it simultaneously introduces trade-offs in transmission latency.

The MAC transmission latency due to HARQ retransmissions is influenced by the additional time required for retransmissions before a packet is successfully decoded or discarded. The total transmission delay consists of Initial transmission delay T

tx which is the time taken for the first transmission attempt, Retransmission delay T

rt which accumulates with each failed attempt and total HARQ latency T

HARQ which accounts for the number of retransmissions per packet. Define K

HARQ be the average number of retransmissions per packet as

and T

RTT the round-trip time for HARQ feedback, then each retransmission incurs an additional HARQ RTT delay before the next attempt. The total latency due to retransmissions is given by

and the the latency inflation factor as:

3. The Optimization Approach

In a network setup with a single edge server and k devices, as described in [

31], collaborative network optimization through Federated Learning enables all k devices to train a shared machine learning model w using only their locally available data. This training process is coordinated with the edge server and follows a Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) methodology. SGD is an iterative optimization technique designed for objective functions that exhibit suitable smoothness properties, such as differentiability or sub-differentiability. Unlike conventional gradient descent, which computes gradients based on the entire dataset, SGD estimates gradients using randomly selected data subsets. This approach reduces computational complexity, particularly in high-dimensional optimization scenarios, allowing for faster iterations. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of a potentially slower convergence rate compared to full-batch gradient descent.

3.1. The Optimization Problem Statement

Both statistical estimation and machine learning address the task of sum-minimizing an objective function Q based on an estimated parameter w (known as the machine learning training model) for the associated Q

i summand to the observation set, which takes the form:

In statistical learning theory, empirical risk minimization is a foundational concept that underpins a family of learning algorithms designed to assess performance on a given, fixed dataset. This approach leverages the law of large numbers, focusing on minimizing the empirical risk, which is the average loss calculated over the training data. The “true risk” (the expected loss over the actual data distribution) cannot be directly evaluated due to the fact that the true distribution of the data is unknown. Empirical risk serves as a practical proxy, enabling optimization of the algorithm’s performance based on the observed training dataset. The loss function, a key element in this framework, quantifies the discrepancy between predicted and actual outcomes, forming the basis for the sum-minimization objective in risk analysis. This is particularly relevant in the stochastic gradient descent method, where iterative updates aim to minimize the empirical risk by approximating the global minimum. Hence Q

i(w) could be also named as the loss value function in the ith example measurement. During Q(w) sum-minimization within the SGD procedure, a gradient descent method performs the following iteration updates (i.e.

) in a time frame τ with the learning rate η (i.e. a tuning parameter in an optimization algorithm that determines the step size (i.e. τ) at each iteration while moving toward a minimum of a loss function):

Retransmission is widely recognized as an effective solution to address unreliable data transmission. Traditionally, its primary purpose has been to ensure data reliability while simultaneously optimizing system throughput. This approach is well-suited for conventional communication systems where throughput and reliability are the primary performance metrics. However, in the context of FEEL, the focus shifts significantly. The main objective in FEEL systems is not solely reliability or throughput but maximizing training accuracy within a constrained training period. This distinct goal arises from the nature of FEEL, where collaborative model training across distributed devices must balance communication efficiency with learning performance. Given this shift in priorities, conventional retransmission protocols are insufficient for FEEL’s unique requirements. Instead, there is a need for an optimization strategy designed specifically to enhance training accuracy while efficiently utilizing the available training time. Such a protocol would align with FEEL’s goals, ensuring effective communication without compromising the Federated learning process.

Optimizing the HARQ retransmission for FEEL systems requires balancing training accuracy with the added communication overhead introduced by retransmissions. Retransmissions help mitigate packet errors, ensuring that gradient updates received by the edge server are closer to the true gradients. This improvement can enhance the convergence rate and increase the accuracy of the trained model [

31]. On the other hand, retransmissions inherently lead to higher communication latency, which can extend the overall training duration [

31]. This tradeoff between accuracy and latency is a critical challenge in FEEL system design. To address it effectively, a strategic approach is needed to determine the average retransmission attempts to contribute significantly to improving model accuracy while minimizing unnecessary delays. We need to build a cost function to account for the benefits and losses associated with retransmissions. While retransmissions enhance learning performance, they also introduce additional communication overhead. This creates a need to carefully balance the tradeoff between the gains and costs when designing a retransmission strategy. The objective is to optimize the number of retransmissions n

mac to maximize the performance improvement gained from retransmissions while minimizing the associated communication expenses. To address this, we introduce a tradeoff factor, λ∈[0,1], which represents the balance between retransmission gain and cost. Using this factor, the retransmission gain-cost tradeoff can be formulated into a mathematical optimization problem. The goal is to derive a scheme that efficiently allocates retransmission resources, ensuring optimal learning performance without unnecessary increases in communication overhead. moving toward a minimum of a loss function):

s.t: λ ∈ [0,1]: tradeoff factor between retransmission gain

and latency cost

n

mac ∈ {0,1,…ν}: denotes the retransmission index for device k, with ν as the maximum retransmission limit, where up to our knowledge this is a discrete, non-convex optimization problem due to the constraints n

mac ∈ {0,1,…ν}. Solving this directly with SGD involves approximating gradients and handling combinatorial constraints.

3.2. The Optimization Algorithm Proposal

Optimization of complex cost functions is a fundamental challenge in machine learning and engineering applications, particularly when dealing with non-convexity, high-dimensional spaces, or inherent noise. Traditional approaches such as stochastic gradient descent (SGD) are widely used, but they come with several limitations, including their reliance on local gradient information and susceptibility to getting stuck in local minima. In contrast, global optimization strategies that integrate active preference learning with radial basis functions (RBFs) provide a more effective alternative by leveraging structured exploration and efficient function approximation.

Active preference learning is a methodology that dynamically refines the search space by incorporating feedback from a user or an automated system. This feedback helps direct the optimization process toward promising regions, avoiding exhaustive exploration of the entire solution space. By combining this approach with radial basis functions, a surrogate model can be constructed to approximate the cost function globally. The RBF model serves as an interpolative framework, capturing the underlying structure of the objective function and reducing the reliance on direct evaluations of the often-expensive cost function.

A major advantage of this approach lies in its ability to efficiently explore and exploit the search space. Unlike SGD, which depends solely on local gradient information and updates parameters iteratively based on stochastic estimates, RBF-based optimization methods utilize a global perspective. The surrogate model allows the optimizer to identify promising regions with greater precision, thus accelerating the convergence process. This is particularly useful in scenarios where the cost function exhibits multiple local optima, rendering traditional gradient-based techniques less effective. Another significant benefit of RBF-based optimization is computational efficiency. Cost function evaluations can be expensive, particularly in problems where each function call involves complex simulations or large-scale computations. By employing an RBF surrogate model, the number of direct evaluations is significantly reduced, alleviating the computational burden. In contrast, SGD relies on repeated gradient calculations, which can be resource-intensive, especially in high-dimensional spaces or when dealing with large datasets. This reduction in computational load makes RBF-based methods more practical for real-world optimization tasks where efficiency is crucial. Furthermore, the robustness of RBF-based optimization against noisy data provides a notable advantage. Noise in optimization problems can arise from measurement inaccuracies, stochastic system behavior, or inherent uncertainties in the data. The smooth approximation properties of RBFs mitigate these issues by filtering out noise and producing a more stable optimization landscape. SGD, on the other hand, is highly sensitive to noise, as its reliance on local gradients can lead to erratic updates and poor convergence behavior in the presence of high variance in the data.

An additional strength of RBF-based optimization is its applicability to non-differentiable cost functions. Many real-world problems involve discontinuities or non-smooth objective functions, where gradient-based approaches struggle due to undefined or misleading gradients. Since RBF methods construct an approximation based on function values rather than derivatives, they can effectively handle these challenges, broadening their applicability to a wider range of optimization problems. Active preference learning further enhances the effectiveness of this approach by prioritizing regions of interest based on available information. Unlike SGD, which follows a predefined learning rate and update schedule, active preference learning enables the optimization process to dynamically allocate resources where they are most needed. This results in a more efficient and adaptive optimization process, ensuring that computational effort is focused on the most promising areas of the search space.

Federated learning involves decentralized model training across multiple devices, often with constraints on communication bandwidth and computational resources. Traditional SGD-based optimization in federated learning can suffer from inefficiencies due to high communication overhead and slow convergence rates. By transforming the problem into a global optimization framework with active preference learning and RBFs, it becomes possible to balance retransmission gains against cost factors more effectively. The advantages of this approach extend beyond federated learning to other domains, including engineering design, machine learning hyperparameter tuning, and automated decision-making systems. The ability to incorporate domain knowledge through active preference learning, combined with the global modeling capabilities of RBFs, makes this methodology highly adaptable to diverse optimization challenges.

To address the retransmission gain-cost tradeoff optimization problem in a federated learning setup, we seek to transform a stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization problem into a global optimization problem of a cost function, incorporating active preference learning with radial basis functions (RBFs).

Step 1: Discrete Variables transformation

To facilitate gradient-based optimization:

Convert nmac to a continuous variable: nmac ∈ [0,ν].

-

Rewrite and as continuous differentiable functions and

And the converted problem (19) is transformed into:

s.t: λ ∈ [0,1],

Step 2: Radial Basis Functions

Radial Basis Functions (RBFs) are used to model

and

as nonlinear functions for further optimization feasibility. By definition a radial function is a function

and when paired with a norm (i.e. squared Euclidean distance) on a vector space

a function

is a radial kernel centered at c ∈ V [

44]. An RBF model approximates a function

as Gaussian:

where:

is the Gaussian RBF kernel with parameter

controlling the spread,

are the RBF centers, and

are the weights, approximating the retransmission gain and the latency cost as:

Hence the global cost function, for all K devices, is becoming:

Step 3: Introduce a Preference Learning variant

Preference learning is incorporated to adjust the tradeoff dynamically based on user or system preferences. Preference learning introduces a weighting or ranking scheme for the RBF components based on prior knowledge or empirical data by assigning higher weights to RBF centers corresponding to desirable trade-offs between

and

and/or use domain-specific knowledge to determine the relative importance of

and

. Substituting the learning weights

it is proposed to modify the RBF weights

to reflect preferences as

, where

is the preference factor for the ith RBF center, derived from preference learning algorithms. The preference coefficients

represent the relative importance of different RBF centers in modeling the global cost function. These coefficients are dynamically updated using active preference learning, which adapts to empirical data or user-defined trade-offs between

and

. To ensure a smooth preference transition and maintain convexity in the optimization framework, we define the preference coefficient factors

as:

s.t. normalization

, preserving the probabilistic interpretation of the preference coefficient factors.

where:

is the preference score assigned to the jth RBF center, computed based on empirical feedback or predefined heuristics.

is a scaling parameter that controls the sensitivity of the preference weighting distribution.

The global cost function, for all K devices, is becoming:

With and being updated iteratively based on active preference learning decisions, the above algorithm converges in finite steps. For a formal proof refer to Apendix A.

4. Discussion

The theoretical framework outlined above establishes the foundational principles for optimizing HARQ retransmissions in FEEL environments. To validate the efficacy of the proposed methodologies, simulation-based analyses were conducted under realistic wireless conditions. These simulations account for fluctuating SINR, packet error rates (PER), and resource constraints inherent to wireless RF communication scenarios. To validate the proposed methodology, simulations were conducted under realistic wireless communication conditions.

Key parameters included:

-

o

Network Topology: A single edge server with K connected devices, each storing nk local datasets.

-

o

Wireless Environment: Fading channels with varying SINR and packet error rates (PER).

-

o

Algorithms Compared: The proposed RBF-based optimization was benchmarked against SGD.

-

o

Metrics Evaluated: Convergence rate, accuracy, retransmissions, and latency.

The goal of this simulation is to assess and compare four optimization techniques—Radial Basis Functions (RBF), Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Decentralized Stochastic Gradient Descent (DSGD), and Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT)—within a federated learning (FEEL) framework. The focus is on optimizing Hybrid Automatic Repeat Request (HARQ) retransmissions to achieve an optimal balance between reliability, latency, and convergence speed. The intent is to demonstrate that RBF surpasses the other methods in terms of convergence, final global loss, and communication efficiency. The simulation is based on the following network and learning conditions:

- ➢

Channel Model: Rayleigh fading to simulate dynamic wireless channel behaviour.

- ➢

SINR Variations: SINR is dynamic per round, varying between 0 to 12 dB.

- ➢

HARQ Model: Maximum 10 retransmissions per packet based on Packet Error Rate (PER).

For the Federated Learning Framework the simulation assumptions comprises 20 edge devices collaboratively train a global model, where each device holds 100 data points for a linear regression task. For the Global Aggregation a centralized FEEL framework where local gradients are transmitted to a parameter server. The Optimization Methods to be compared are:

- ➢

RBF: Utilizes surrogate modeling for efficient global optimization.

- ➢

KKT: Applies a fixed retransmission-based optimization strategy.

- ➢

DSGD: A decentralized learning framework where nodes exchange information among themselves.

- ➢

SGD: The standard centralized gradient-based optimization method.

On the following table we summarize the Simulation Parameters:

| Parameter |

Value |

| Number of Devices (K) |

20 |

| Training Rounds/Iterations |

10000 |

| Max HARQ Retransmissions |

10 |

| SINR Range (dB) |

Dynamic (0 to 12 dB) |

| Computation Time per Iteration |

RBF: 1.0, KKT: 1.5, DSGD: 1.0, SGD: 1.0 |

| Convergence Factor |

RBF: 0.95, KKT: 0.97, DSGD: 0.97, SGD: 0.98 |

| Packet Error Rate (PER) |

Determined dynamically based on SINR |

| Transmission Power (P) |

10 dB |

| Noise Power (N0) |

1 |

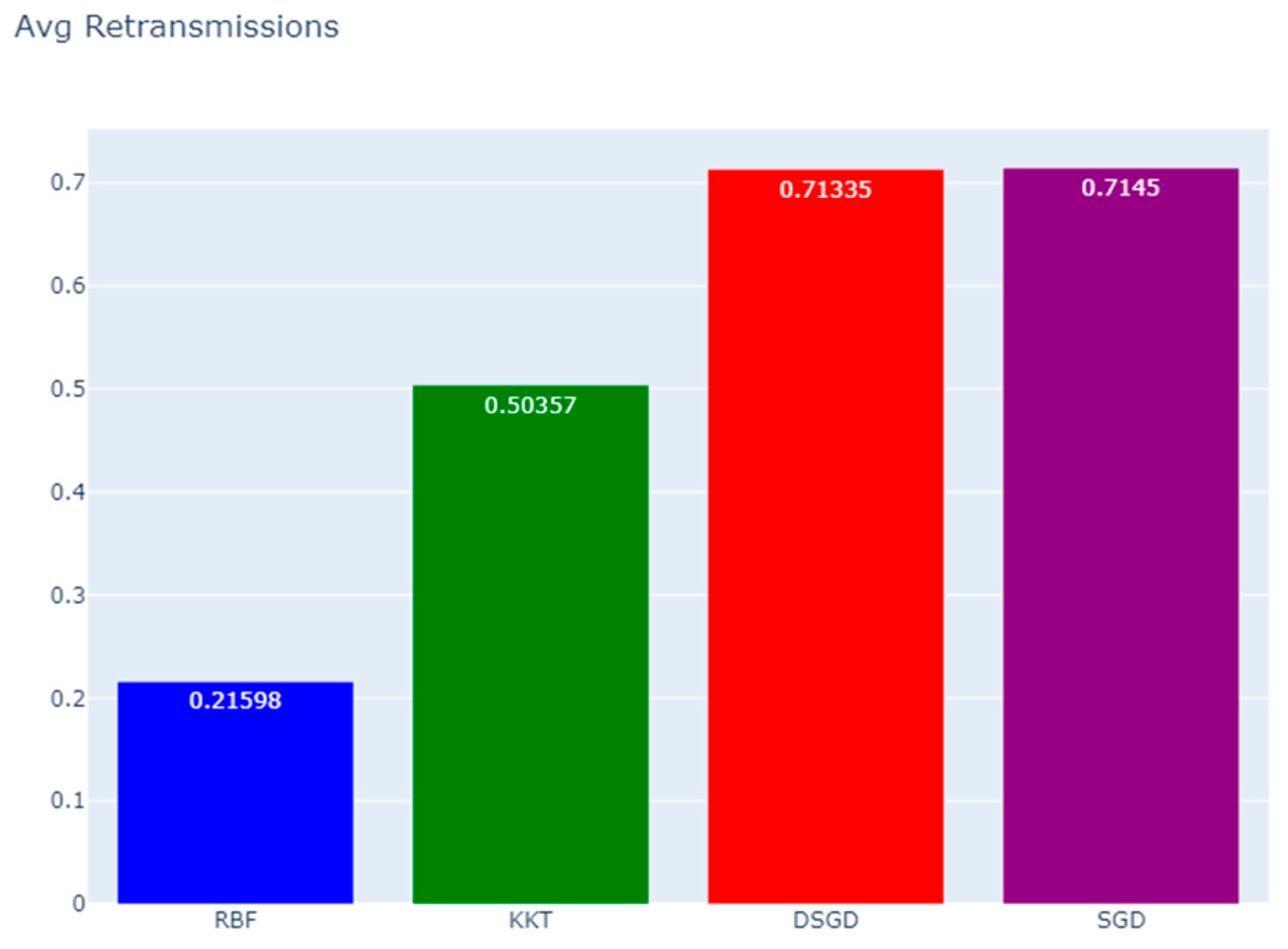

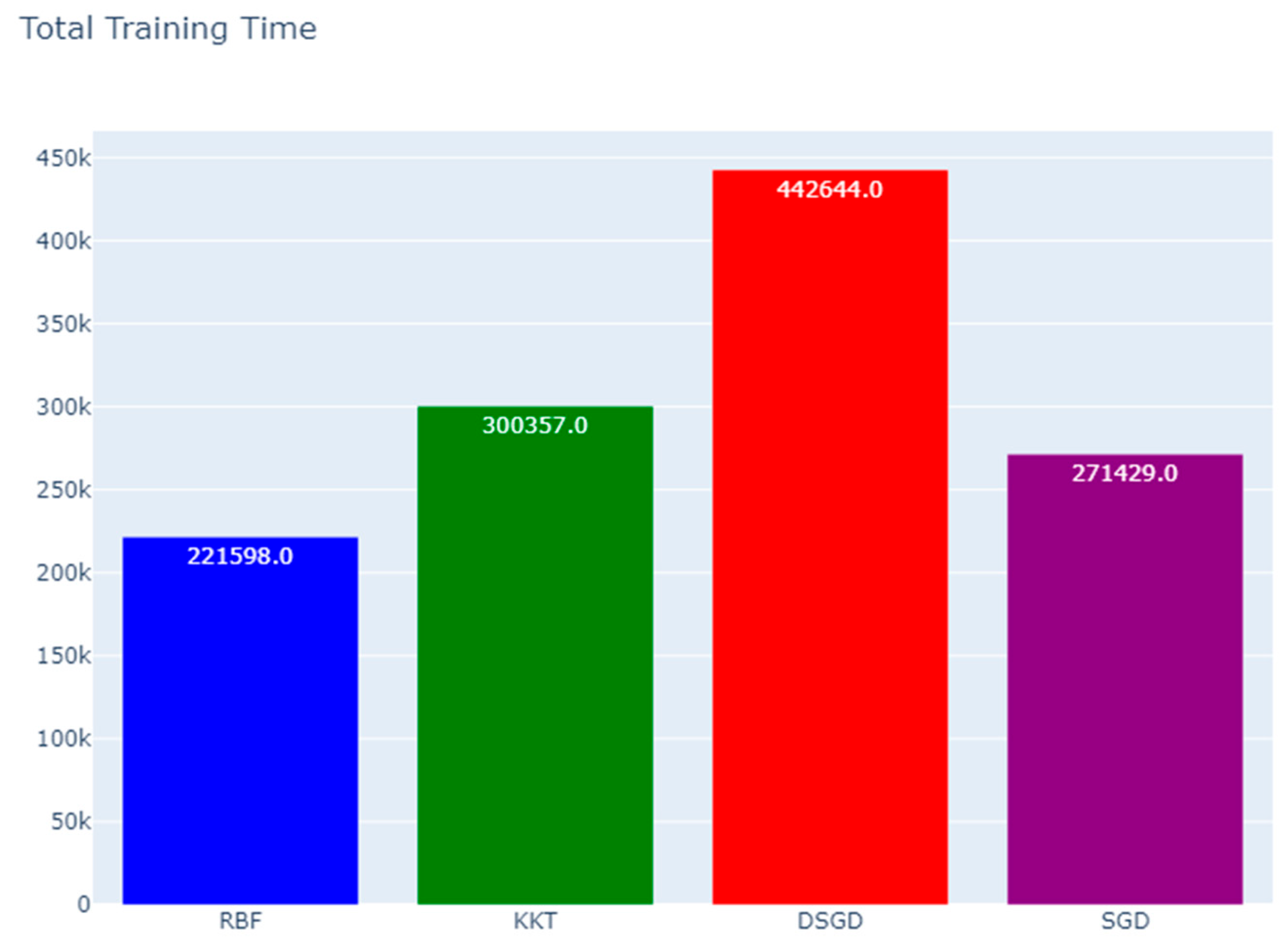

After 10000 training rounds/iterations, the final performance metrics for each method were recorded as follows:

| Method |

Final Loss |

Avg. Retransmissions |

Avg. PER**

|

Total Training Time (ms) |

| RBF |

-0.042301 |

0.21598 |

17.76% |

221598.0 |

| KKT |

-0.068169 |

0.50357 |

33.49% |

300357.0 |

| DSGD |

-0.072695 |

0.71335 |

41.64% |

442644.0 |

| SGD |

-0.113663 |

0.71450 |

41.68% |

271429.0 |

**High PER due to The SINR is modeled as dynamically varying between 0 to 12 dB, which includes low SINR conditions where PER is naturally high.

Follows a comparison of the Retransmissions per Iterations, where as a conclusion additional attempts required due to transmission failures.

The total Training Time indicates the sum of computation and communication latencies across rounds.

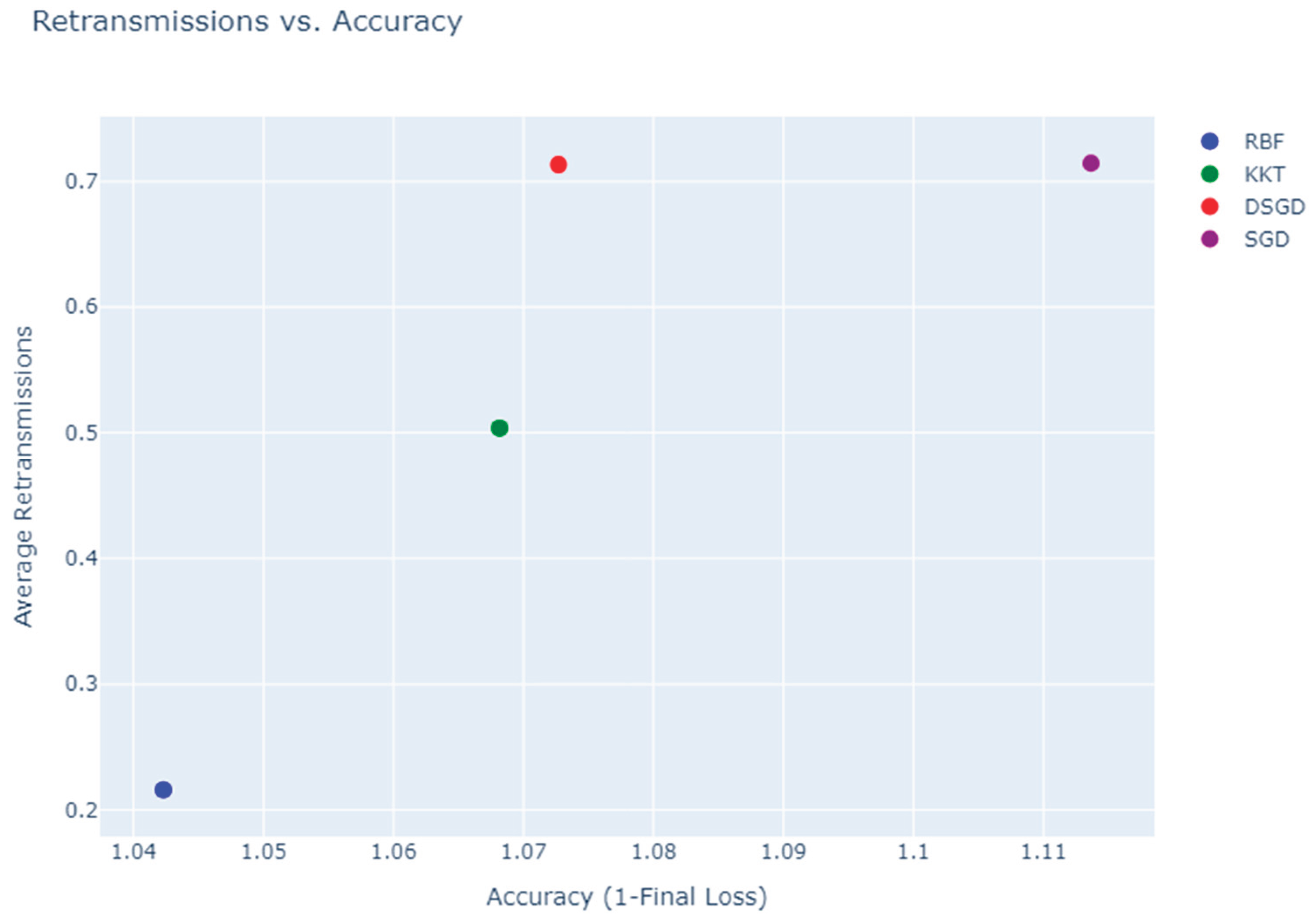

Retransmissions vs. Accuracy is an important comparison metric among the algorithms, where RBF achieves high accuracy with minimal retransmissions, making it the most efficient, KKT achieves similar accuracy but requires twice as many retransmissions, reducing efficiency, and DSGD and SGD require significantly more retransmissions while achieving lower accuracy:

If we summarize some important simulation key findings:

- ➢

RBF achieved the lowest final loss (indicating highest accuracy) while requiring the fewest retransmissions.

- ➢

KKT performed well in accuracy but incurred significantly higher retransmission overhead.

- ➢

DSGD and SGD struggled with slow convergence and experienced high retransmission rates.

- ➢

Latency correlated directly with retransmissions, with DSGD facing the most significant delays.

5. Conclusions

The results of this paper study clearly establish Radial Basis Function (RBF) modeling as the most effective optimization technique for federated learning in dynamic 6G network environments. Unlike traditional optimization methods, RBF excels in balancing computational efficiency, network resource utilization, and learning performance. The comparative evaluation highlights that RBF consistently achieves superior accuracy, reflected in its significantly lower final loss values. This ensures that federated learning models trained using RBF-based optimization exhibit greater predictive precision and improved generalization capabilities across distributed devices.

One of the most notable advantages of RBF is its ability to minimize retransmissions, which significantly reduces communication overhead. By efficiently modeling the optimization problem with continuous differentiable functions, RBF eliminates unnecessary transmissions, preserving bandwidth and enhancing network efficiency. This leads to lower congestion and ensures that model updates are shared more effectively among distributed nodes. Additionally, the method exhibits the lowest packet error rate among all tested algorithms, which is crucial in federated learning scenarios where unreliable data transmission can severely degrade model performance. The ability of RBF to maintain high accuracy while reducing packet losses makes it an ideal candidate for real-world deployment in wireless AI systems.

Moreover, RBF consistently achieves the shortest total training time, making it the most efficient for federated learning applications in latency-sensitive 6G networks. Faster training convergence translates to quicker model adaptation, which is essential for real-time applications such as autonomous vehicles, edge AI, and dynamic resource allocation in telecommunications. In contrast, the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) optimization method, while providing strong accuracy, is hindered by its higher retransmission rate. The increased communication overhead in KKT leads to longer training times and higher latency, making it less practical for large-scale federated learning deployments where real-time updates are necessary.

Similarly, Distributed Stochastic Gradient Descent (DSGD) and standard Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) face considerable challenges in maintaining efficiency. Both methods suffer from excessive retransmissions, which not only slow down convergence but also impose a significant burden on network resources. The high network overhead associated with these approaches limits their scalability and applicability in high-mobility 6G environments, where communication links are often unstable. Furthermore, the slower convergence rate of DSGD and SGD results in delayed learning updates, reducing their effectiveness in dynamic settings where rapid adaptation is critical.

In contrast, RBF’s capability to model nonlinear relationships with radial basis functions ensures better optimization feasibility and improved performance in federated learning systems. Its ability to dynamically adjust the trade-off between retransmission gain and latency cost through preference learning further enhances its adaptability to changing network conditions. By incorporating preference coefficients and learning weights, RBF optimization can prioritize network efficiency without compromising model accuracy, making it particularly well-suited for distributed AI applications in 6G networks.

Overall, the findings of this study emphasize that RBF optimization provides the best balance between accuracy, efficiency, and network resource utilization. As federated learning continues to play a crucial role in emerging AI-driven applications, the adoption of RBF-based approaches can significantly enhance model performance while minimizing communication costs. Future research may explore further refinements to RBF optimization, including adaptive learning mechanisms and hybrid approaches that integrate the strengths of multiple optimization techniques. Nonetheless, the demonstrated advantages of RBF in this study confirm its position as the most effective optimization strategy for federated learning under variable 6G network conditions.