1. Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI), encompassing traumatic brain injury (TBI), cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), and brain tumors (BT), remains one of the major causes of long-term disability worldwide. It has a profound impact on patients’ visual, cognitive, and motor functions [

1,

2].

People affected by ABI frequently present a broad spectrum of neurological sequelae, including emotional disturbances such as anxiety and depression, along with cognitive, behavioral, physical, and motor impairments. These limitations reduce autonomy and social participation, making multidisciplinary rehabilitation a long and essential process [

1,

2].

Around half of all patients with ABI experience some form of visual disturbance. Common manifestations include visual fatigue, blurred vision, and difficulty performing visually demanding tasks like reading. Visual field defects (e.g., hemianopia or quadrantanopia), loss of three-dimensional vision, photophobia, and oculomotor disorders such as strabismus or nystagmus are also frequent [

3,

4,

5]. These problems are among the most disabling consequences of ABI, affecting mobility, reading ability, and daily functioning [

6].

Stroke, in particular—the second leading cause of death and the third cause of disability globally—results in oculomotor dysfunction in up to 85% of cases. Despite this high prevalence, visual problems are often overlooked during post-stroke rehabilitation, even though nearly nine out of ten patients present some degree of visual impairment [

7].

The visual pathway may be compromised at any level, from the retina to the visual cortex. Lesions of the optic nerve produce specific visual field defects reflecting the topographic arrangement of retinal fibers, whereas retrochiasmatic damage-involving the optic tract, lateral geniculate nucleus, optic radiations, or visual cortex-usually leads to homonymous hemianopia or quadrantanopia, often with macular sparing [

8].

Neuroplasticity allows a certain degree of visual recovery during the first weeks or months after cortical injury. In later stages, visual rehabilitation programs can improve depth perception, eye movements, and spatial orientation [

9,

10]. The mechanisms underlying oculomotor dysfunctions after brain injury, however, are not fully understood; they often worsen under high cognitive load, indicating the involvement of attentional and executive cortical networks [

11].

Oculomotor disorders are therefore common in ABI and can limit functional visual field performance. Within this framework, vision therapy (VT) aimed at improving oculomotor control may offer an effective strategy to optimize the remaining visual function rather than to regenerate damaged areas. Based on the principles of neuroplasticity, these programs seek to improve saccadic efficiency, reduce compensatory head movements, and enhance eye–hand coordination through structured, task-oriented exercises [

12].

Despite the clinical relevance of these interventions, few studies have assessed their outcomes in ABI, and access to specific visual rehabilitation programs remains limited [

3,

4,

5]. In recent years, virtual reality (VR)-based technologies have emerged as promising tools in this field, providing immersive, multisensory, and individualized environments. Devices such as Dicopt Home and Dicopt Pro deliver dichoptic and oculomotor training adapted to the patient’s residual visual field, potentially facilitating neuronal reorganization and functional recovery [

13,

14].

Nevertheless, current evidence on the use of VR-based visual rehabilitation in ABI is still scarce. The present study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a virtual reality–based vision therapy program (Dicopt Home) in individuals with acquired brain injury, combining objective visual field assessment with patient-reported visual symptom measures to explore both functional and perceptual outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The study included 52 participants with a confirmed diagnosis of acquired brain injury (ABI) (either stroke (CVA), brain tumor (BT), or traumatic brain injury (TBI)) who had achieved clinical stability for at least six months. Participants were recruited from the Neuro-ophthalmology Department at Gregorio Marañón Hospital and from several brain injury foundations and associations in the Madrid region, including the Spanish Brain Injury Federation (FEDACE), Daño Cerebral Invisible, and Freno al Ictus.

All procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain; reference 23/614-E, October 18, 2023). Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Visual examinations were conducted at the Optometry and Vision Clinic of the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM). Data were recorded on standardized collection sheets and subsequently transferred to a computer database. For subjective symptom assessment, responses were gathered using digital forms created on the Google Forms platform.

Exclusion criteria included the absence of binocular vision, a time since brain injury of less than six months, or failure to provide signed informed consent. Participants were assigned to the control or therapy groups using a balanced allocation procedure without randomization.

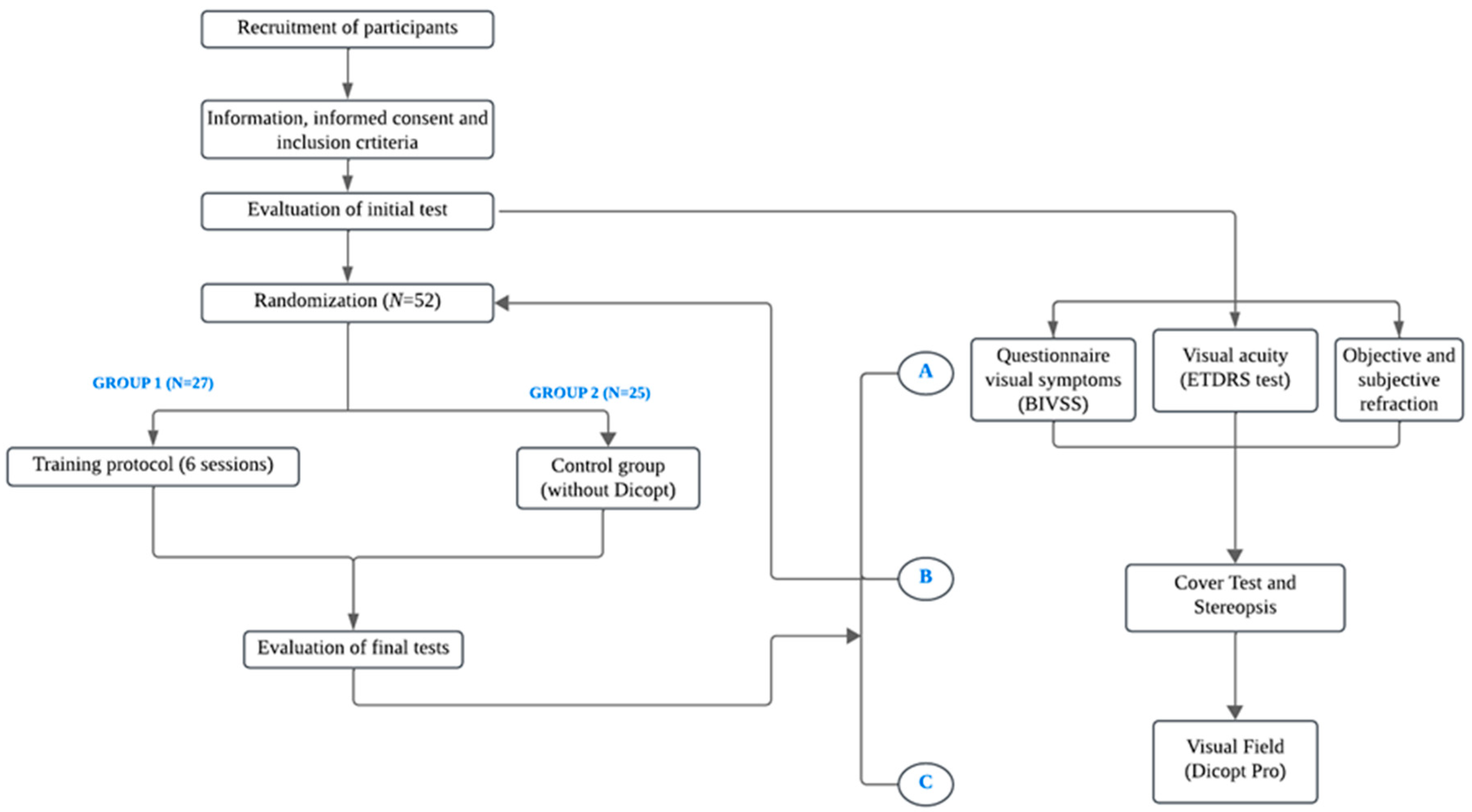

2.2. Experimental Protocol

At the first visit, participants completed the Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS) questionnaire (15), a validated instrument for quantifying visual symptoms such as blur, double vision, photophobia, and reading difficulties in patients with acquired brain injury. A detailed anamnesis was then performed, followed by measurements of best-corrected visual acuity (VA), stereopsis, and ocular deviations using the cover test (CT). Finally, functional visual field (VF) testing was carried out using the Dicopt Pro virtual reality (VR) device, recording the following parameters:

After baseline assessment, participants were assigned to two groups following a controlled parallel-group design with balanced allocation. Group 1 underwent six sessions of Dicopt Home vision therapy (VT), lasting 15 minutes each, while Group 2 served as the control group and received no treatment. Control participants were unable or unwilling to participate in therapy sessions. The dataset was divided according to an experimental design, with 27 participants assigned to the training group and 25 to the control group, ensuring balanced allocation.

The six VT sessions were organized into three game modules, each targeting different visual skills. Their order was randomized for each participant:

Module 1: “Monster Game”- oculomotor training (2 sessions),

Module 2: “Runner”- binocular vision training (2 sessions),

Module 3: “Double Space”- vergence training (2 sessions).

At the final visit, all baseline measurements were repeated in both groups to evaluate changes over time. A schematic flowchart of the experimental design is shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Materials

Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS): Visual symptoms were assessed using the validated Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS) questionnaire (Laukkanen et al., 2017(15)), composed of 28 items addressing blur, double vision, glare, photophobia, eye discomfort, dryness, depth perception, peripheral awareness, and reading difficulties. Each item was rated according to symptom frequency, providing an overall score that reflects the perceived visual impact in patients with acquired brain injury.

Visual Acuity (VA): Best-corrected VA was measured monocularly and binocularly using a standard ETDRS logMAR chart (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study) at 4 m for distance and 40 cm for near vision. The smallest line correctly identified by the participant was recorded as the final VA score.

Cover Test (CT): The CT was performed for both distance and near fixation to identify and quantify ocular misalignments using prism bars. Base-in (BI) prisms were applied for exodeviations and base-out (BO) prisms for esodeviations. The fixation target corresponded to two lines below the VA of the worse eye.

Stereopsis: Depth perception was evaluated at 40 cm using the Titmus stereo test with polarized glasses. The smallest measurable disparity in seconds of arc was recorded as the stereopsis threshold.

Visual Field (VF): Binocular VF (120°) was evaluated using the Dicopt Pro virtual reality (VR) device, which integrates an eye-tracking system. After calibration, participants fixated on a central red cross and pressed a trigger each time they detected a peripheral stimulus. The test automatically paused if fixation was lost. A “seen/not seen” strategy was applied to assess the functional VF across quadrants, and results were automatically generated and exported for analysis (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Functional visual field test using the Dicopt Pro virtual reality device.

Figure 2.

Functional visual field test using the Dicopt Pro virtual reality device.

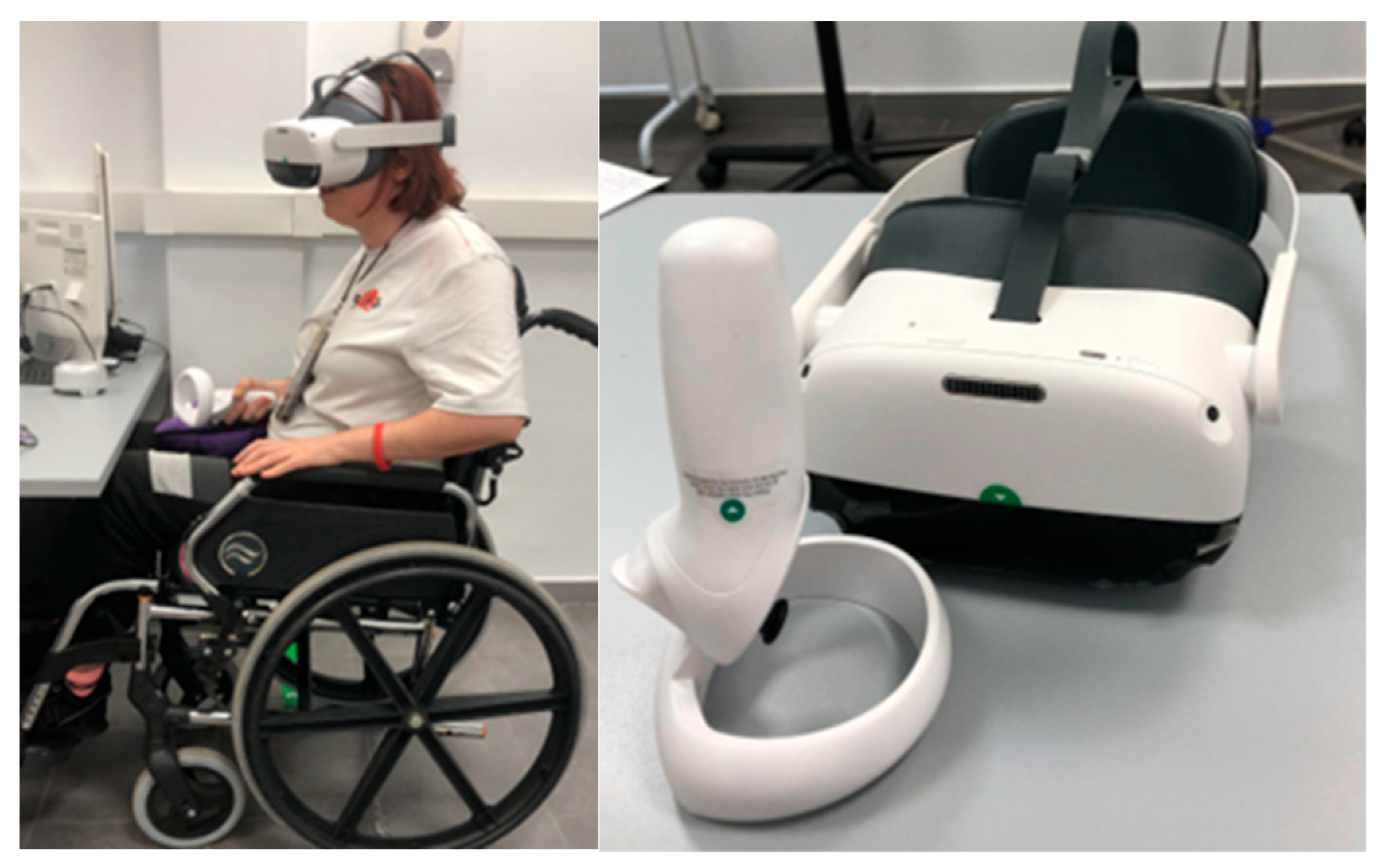

Dicopt Home Vision Therapy: The intervention was carried out using the Dicopt Home mobile application, a VR-based tool that allows patients to perform vision therapy (VT) either in a clinical or home-based setting. The system is designed to enhance binocular vision, accommodation, and oculomotor control by presenting distinct stimuli to each eye, thus promoting binocular integration.

A VR headset and joystick controller were required (

Figure 3). The smartphone was placed inside the headset, allowing adjustment of interpupillary distance (IPD) and focus. Participants interacted with various game-based exercises following on-screen instructions. All sessions were conducted under direct supervision by an optometrist to ensure proper task execution and patient safety. No adverse effects such as dizziness or nausea were reported.

The software was developed by V-Vision S.L. (Spain) and certified with CE marking for medical use.

The therapy included three interactive games:

Monster Game: oculomotor training; participants aim and shoot only at the monster matching the central reference image (

Figure 4a).

Runner: binocular coordination training; the goal is to avoid obstacles and collect coins by pressing the “X” button to jump (

Figure 4b).

Double Space: vergence training; participants control two spaceships—blue (left joystick) and red (right joystick)—to avoid asteroids and collect stars of the corresponding color (

Figure 4c).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v30 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive and non-parametric statistics were applied, as the data did not meet normality assumptions (Shapiro–Wilk test, n < 50). Between-group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and within-group comparisons using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A mixed ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in the top-right visual field quadrant. Although non-parametric tests were used for group comparisons, a mixed ANOVA was performed as an exploratory analysis to identify potential time × group interactions. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

The main outcome variables were the percentage of detected visual stimuli and the reaction time (RT). Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding values of 0.847 for detection percentage and 0.937 for RT, indicating excellent reliability.

3. Results

A total of 52 participants were included (27 in the training group and 25 in the control group), with a balanced sex distribution (51.9% male and 48.1% female). The control group included 40% CVA, 40% BT, and 20% TBI cases, whereas the therapy group comprised 70.4% CVA, 14.8% BT, and 14.8% TBI, ensuring a balanced allocation of etiologies between groups. The main etiologies overall were cerebrovascular accident (CVA) in 55.8% of cases, brain tumor (BT) in 26.9%, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) in 17.3%. Descriptive characteristics by etiology are presented in

Table 1.

At baseline, participants with BT were older and showed lower stereopsis (median 1976 arc sec, IQR 100–3552), while those with TBI presented greater near exodeviation (median –14 Δ, IQR –17 to –3). Participants with TBI also reported fewer visual symptoms in the BIVSS questionnaire (median 27, IQR 16.5–46.0) compared with those with BT (median 48.5, IQR 34.5–58.0).

After the intervention, a statistically significant increase was observed only in the top-right visual-field quadrant for the percentage of detected stimuli (median values increased from 79% [IQR 50.25–94.00] to 85% [IQR 53.00–94.00]; p < 0.001). No significant differences were found in the remaining quadrants or in reaction time (RT). Baseline comparisons between groups showed differences in distance cover test (p = 0.047) and stereopsis (p = 0.003), so these variables were not included in the analysis of change. For visual-field outcomes, between-group differences in pre–post change were not significant (all p > 0.05), as summarized in

Table 2.

Both groups showed a slight improvement in the top-right quadrant, with a median gain of 8% in the therapy group versus 2% in controls. Reaction time tended to increase in the control group and decrease in the therapy group, although with wide interquartile variability. A mixed ANOVA for the top-right quadrant revealed a main effect of time (p = 0.02), reflecting a general improvement across participants, but no group × time interaction (p = 0.069), indicating a similar trend of improvement in both groups.

When stratified by etiology, no significant between-group differences were observed in participants with CVA or BT in either the percentage of detected stimuli or reaction time, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In the TBI subgroup (n = 9), however, a significant difference was found in the top-left visual-field quadrant (p = 0.040), with a greater increase in the therapy group (median +5%, IQR 3–7.09) than in controls (median +2%, IQR –2–2). This finding should be interpreted with caution given the small subgroup size and the heterogeneity of lesion locations among TBI participants. Reaction-time changes were not significant in any subgroup.

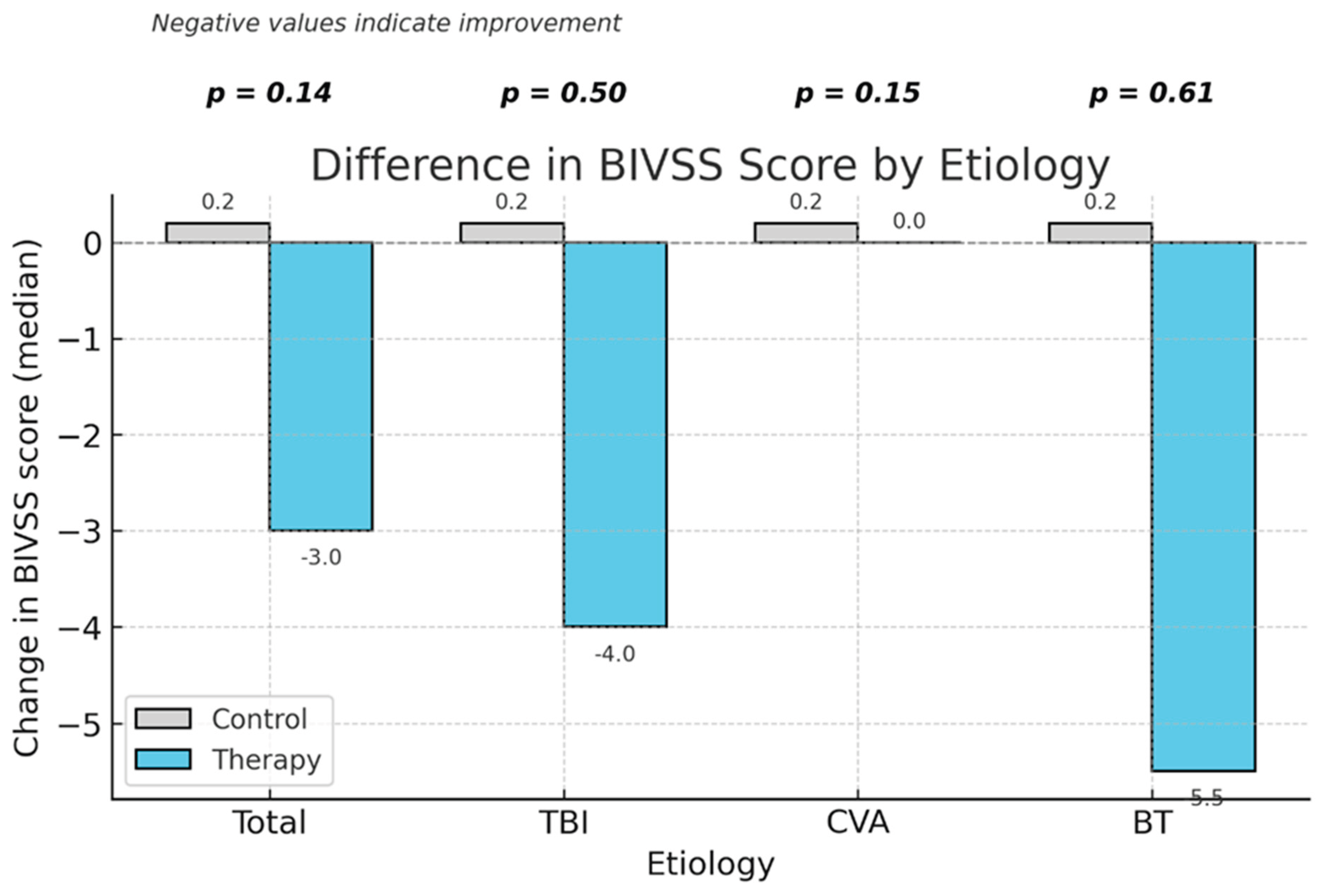

Regarding patient-reported outcomes, the BIVSS total score ranges from 0 to 100, with lower values indicating fewer visual symptoms. Scores decreased in the therapy group after intervention, indicating an improvement in perceived visual comfort. A significant within-group improvement was found only in the therapy group (median change –3 points, IQR –8 to 0; p = 0.015), while the control group remained stable (p = 0.202). The between-group comparison of BIVSS change was not significant (p = 0.144).

When analyzed by etiology, no significant differences were found between groups; however, the therapy group showed a tendency toward lower post-intervention BIVSS scores—indicating reduced visual symptoms—in participants with TBI and BT, as illustrated in

Figure 5. Overall, these findings suggest that the virtual reality–based vision therapy did not produce differential effects on visual field performance between groups, although individual improvements in visual perception were observed.

4. Discussion

The sample showed a balanced sex distribution and a median age of 51 years, representing a typical profile of adult patients with acquired brain injury (ABI). The binocular vision alterations observed, such as deviation in the cover test or reduced stereopsis, reflect the functional impact of ABI on the visual system, consistent with previous clinical reports [

12,

16].

In this study, most cases were associated with stroke, followed by cranial trauma (CT) and traumatic brain injury (TBI), a distribution that aligns with prior prevalence data (16). This etiological diversity highlights the need to tailor therapeutic strategies to the underlying cause and clinical profile of each patient, as different lesion mechanisms may result in distinct visual patterns and rehabilitation responses. Lee YJ et al. [

17] compared visual field defects in stroke and TBI patients, reporting that both groups exhibited alterations, although with different topographic characteristics. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive visual evaluations and individualized rehabilitation protocols as part of the overall management of ABI patients.

In our study, no significant relationship was found between visual therapy (VT) and objective gains in the perimetric visual field (p > 0.05), except for a slight improvement in the top Rightt quadrant, where the experimental group showed a higher percentage increase. Reaction time measures also showed no relevant differences between groups. These results are consistent with numerous studies reporting limited or no perimetric recovery following rehabilitation [

18,

19,

20]. Matteo et al. [

18] emphasized the variability of rehabilitative effects on visual function, which may stem from heterogeneity in therapy protocols, treatment duration, and the targeted functional domains.

On the other hand, studies such as that by Smaakjær et al. [

21] demonstrated that oculomotor-based VT improves fixation stability, reading efficiency, and visual attention, even without measurable expansion of the visual field. This supports the notion that functional improvement after ABI often results from compensatory mechanisms—such as enhanced scanning strategies or optimized saccadic control—rather than structural recovery of the damaged visual field. Similarly, Aimola et al. [

19] and Hazelton et al. [

20] reported significant functional improvements in daily activities following oculomotor training, despite the absence of perimetric changes, supporting the hypothesis of cortical reorganization or behavioral compensation rather than anatomical restoration.

The results from Mena-García et al. [

22] also point in this direction: their compensatory saccadic training program for patients with hemianopia led to improvements in visual processing and functional independence, without measurable recovery of the visual field. Taken together, these findings—and our own results—reinforce the idea that visual rehabilitation in ABI enhances visual function and quality of life, even when structural restoration is not achieved.

Neuroimaging studies provide complementary evidence supporting these mechanisms. Nelles et al. [

23] demonstrated that oculomotor training in post-stroke hemianopia induces cortical activation changes indicative of neuroplasticity. Kerkhoff et al. [

24] and Willis et al. [25] reported increases in visual field size and perceptual performance after intensive training, suggesting that repeated stimulation may drive functional reorganization in visual areas. However, such benefits appear dependent on treatment duration and intensity—variables that, in our study (six sessions), may have been insufficient to produce measurable field changes.

Roth et al. [26] found that saccadic training improved reaction times and visual exploration efficiency, reinforcing the importance of extending the number or frequency of sessions to maximize functional outcomes. Future studies should therefore explore longer, more intensive interventions and include longitudinal follow-up to assess persistence of effects.

An important aspect of our study concerns the influence of etiology on therapeutic response. Prior evidence indicates that patients with TBI may show greater neuroplastic potential and better oculomotor rehabilitation outcomes compared to those with stroke. Ciuffreda et al. [

6,

7] reported a 90% success rate in symptom improvement among TBI patients, while Kapoor and found significant gains in the Developmental Eye Movement (DEM) test in the same population (p < 0.035). In line with these reports, our study also found a significant improvement in the top-left quadrant among TBI patients (p = 0.04), suggesting a higher capacity for functional recovery in this group.

Rowe et al. [

16] and Rasdall et al. [27] similarly observed that TBI-related visual field defects tend to be more scattered and heterogeneous than those caused by stroke, possibly allowing greater compensatory adaptation. This variability in lesion type and extent likely accounts for some of the differences in VT response observed across studies.

Another contribution of this study lies in demonstrating the effectiveness of dichoptic visual therapy for reducing self-reported visual symptoms. Although no significant perimetric improvement was observed, the BIVSS scores showed a positive trend, consistent with previous studies using subjective symptom questionnaires [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, few investigations have assessed the BIVSS in pre–post intervention designs or in conjunction with virtual reality (VR)–based therapies, underscoring its potential value as a complementary outcome measure in visual rehabilitation research.

The use of VR in neuro-visual rehabilitation is a promising and expanding field. Vilageliu-Jordà et al. [

13] highlighted the effectiveness of immersive VR in cognitive rehabilitation after ABI, noting improvements in motivation and treatment adherence. Likewise, Martino-Cinnera et al. [

14] demonstrated that immersive VR combined with eye-tracking biofeedback can enhance spatial attention and visual exploration, suggesting that integrating VT with immersive environments may amplify neuroplastic and perceptual gains.

Although no peer-reviewed clinical trials have yet evaluated the Dicopt system in individuals with ABI, previous studies of VR-based dichoptic therapy in amblyopia populations have reported significant improvements in stereoacuity and visual acuity [28,29]. This suggests that dichoptic stimulation in virtual reality environments may enhance binocular cooperation and oculomotor control, supporting the rationale for its use in ABI rehabilitation. Furthermore, the Dicopt system has obtained CE marking as a medical device in the European Union, reinforcing its technical and safety validation.

A key limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may have reduced the statistical power to detect subtle functional differences between groups. Future studies including larger and more homogeneous cohorts are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Overall, our findings align with current evidence indicating that visual rehabilitation in ABI patients (especially when incorporating dichoptic or immersive approaches) can reduce visual symptoms and improve functional outcomes, even if anatomical restoration of the visual field remains limited.

Future research should include larger samples, extended training programs, and multimodal assessment (e.g., fMRI, EEG) to better understand the neural mechanisms underlying recovery and to optimize therapeutic protocols.

5. Conclusions

Virtual reality–based dichoptic vision therapy did not produce significant changes in the functional visual field but improved self-reported visual symptoms. These results suggest an optimization of the intact visual function rather than structural recovery of the damaged area. The therapeutic response appeared to vary by etiology, with greater functional gains in TBI cases. Future studies should include longer training protocols and combined objective and subjective measures to comprehensively assess the efficacy of these interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O.-C. and F.J.P.-M.; methodology, C.O.-C., R.B.-V., J.E.C.-S., and F.J.P.-M.; software, R.B.-V.; validation, C.O.-C., F.J.P.-M., and J.E.C.-S.; formal analysis, C.O.-C. and F.J.P.-M.; investigation, C.O.-C., R.B.-V., J.E.C.-S., and F.J.P.-M.; resources, F.J.P.-M. and P.R.; data curation, C.O.-C. and R.G.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.O.-C. and F.J.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.B.-V., J.E.C.-S., and F.J.P.-M.; visualization, G.M.-F. and C.O.-C.; supervision, F.J.P.-M. and P.R.; project administration, F.J.P.-M.; funding acquisition, F.J.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Medicinal Products of the San Carlos Clinical Hospital (Madrid, Spain; reference 23/614-E, October 18, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical and privacy restrictions, the data are not publicly accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The VR systems (Dicopt Home and Dicopt Pro) were provided by V-Vision S.L., which had no role in study design, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABI |

Acquired Brain Injury |

| BI |

Base-In (prism) |

| BIVSS |

Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey |

| BO |

Base-Out (prism) |

| BT |

Brain Tumor |

| CT |

Cover Test |

| CVA |

Cerebrovascular Accident |

| DEM |

Developmental Eye Movement Test |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| IPD |

Interpupillary Distance |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| PPS |

Percentage of Points Seen |

| RT |

Reaction Time |

| TBI |

Traumatic Brain Injury |

| VA |

Visual Acuity |

| VF |

Visual Field |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| VT |

Vision Therapy |

References

- De Dios Perez, B.; Morris, R.P.G.; Craven, K.; Radford, K.A. Peer mentoring for people with acquired brain injury—A systematic review. Brain Inj. 2024, 38, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, K.; Sui, X.; Yi, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, K.; et al. The effect of web-based telerehabilitation programs on children and adolescents with brain injury: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e46957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold Lindstedt, M.; Johansson, J.; Ygge, J.; Borg, K. Vision-related symptoms after acquired brain injury and the association with mental fatigue, anxiety and depression. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, F.J.; Hanna, K.; Evans, J.R.; Noonan, C.P.; Garcia-Finana, M.; Dodridge, C.S.; et al. Interventions for eye movement disorders due to acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, CD011290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, P.Y.; Scott, K.; Myszak, F.; Mamann, S.; Labelle, A.; Holmes, M.; et al. Interventions addressing vision and visual-perceptual impairments following acquired brain injury: A cross-sectional survey. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 87, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda, K.J.; Rutner, D.; Kapoor, N.; Suchoff, I.B.; Craig, S.; Han, M.E. Vision therapy for oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain injury: A retrospective analysis. Optometry 2008, 79, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda, K.J.; Kapoor, N.; Rutner, D.; Suchoff, I.B.; Han, M.E.; Craig, S. Occurrence of oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain injury: A retrospective analysis. Optometry 2007, 78, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, H. Effects of cortical damage on binocular depth perception. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, I.; Gall, C.; Kasten, E.; Sabel, B.A. Long-term learning of visual functions in patients after brain damage. Behav. Brain Res. 2008, 191, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouget, M.C.; Lévy-Bencheton, D.; Prost, M.; Tilikete, C.; Husain, M.; Jacquin-Courtois, S. Acquired visual field defects rehabilitation: Critical review and perspectives. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 55, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.A.; Tayebi, M.; McGeown, J.P.; Kwon, E.E.; Holdsworth, S.J.; Danesh-Meyer, H.V. A window into eye movement dysfunction following mTBI: A scoping review of magnetic resonance imaging and eye-tracking findings. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, J.; Berthold Lindstedt, M.; Borg, K. Vision therapy as part of neurorehabilitation after acquired brain injury—A clinical study in an outpatient setting. Brain Inj. 2021, 35, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilageliu-Jordà, E.; Enseñat-Cantallops, A.; García-Molina, A. Use of immersive virtual reality for cognitive rehabilitation of patients with brain injury. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 74, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino Cinnera, A.; Verna, V.; Marucci, M.; Tavernese, A.; Magnotti, L.; Matano, A.; et al. Immersive virtual reality for treatment of unilateral spatial neglect via eye-tracking biofeedback: RCT protocol and usability testing. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, H.; Scheiman, M.; Hayes, J.R. Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS) questionnaire. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2017, 94, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, F.J.; WRightt, D.; Brand, D.; Jackson, C.; Harrison, S.; Maan, T.; et al. A prospective profile of visual field loss following stroke: Prevalence, type, rehabilitation, and outcome. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 719096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Lee, S.C.; Wy, S.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Lee, W.H.; et al. Ocular manifestations, visual field pattern, and visual field test performance in traumatic brain injury and stroke. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2022, 1703806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matteo, B.M.; Viganò, B.; Cerri, C.G.; Perin, C. Visual field restorative rehabilitation after brain injury. J. Vis. 2016, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimola, L.; Lane, A.R.; Smith, D.T.; Kerkhoff, G.; Ford, G.A.; Schenk, T. Efficacy and feasibility of home-based training for individuals with homonymous visual field defects. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2014, 28, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelton, C.; Todhunter-Brown, A.; Dixon, D.; Taylor, A.; Davis, B.; Walsh, G.; et al. The feasibility and effects of eye movement training for visual field loss after stroke: A mixed methods study. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 84, 030802262093605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaakjær, P.; Wachner, L.G.; Rasmussen, R.S. Vision therapy improves binocular visual dysfunction in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Res. 2022, 44, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Garcia, L.; Pastor-Jimeno, J.C.; Maldonado, M.J.; Coco-Martin, M.B.; Fernandez, I.; Arenillas, J.F. Multitasking compensatory saccadic training program for hemianopia patients: A new approach with 3-dimensional real-world objects. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelles, G.; Pscherer, A.; de Greiff, A.; Gerhard, H.; Forsting, M.; Esser, J.; et al. Eye-movement training-induced changes of visual field representation in patients with post-stroke hemianopia. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 1832–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhoff, G.; Münssinger, U.; Meier, E.K. Neurovisual rehabilitation in cerebral blindness. Arch. Neurol. 1994, 51, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).