1. Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a genetic disorder that is inherited from parents and is characterized by the development of tumors in nerve tissues, including the skin, spinal cord, and cranial nerves. Its diagnosis is based on clinical criteria established by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), which require a thorough clinical evaluation of various signs and symptoms. Research on pediatric cancer survivors has shown that they are at high risk of experiencing long-term complications, including impairments in physical, motor, and cognitive functioning [

1]. Treatment-related factors have been specifically linked to deficits in EF among survivors [

2,

3]. In line with these findings, studies on children with NF1 have examined their executive functions, particularly focusing on difficulties in planning and inhibitory control [

4].

NF1 is the most common variant of this disease and represents one of the most prevalent hereditary syndromes that predispose individuals to cancer in the nervous system. It is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene, which is responsible for encoding the tumor suppressor protein neurofibromin, an essential regulatory component of the RAS signaling pathway. Once the function of neurofibromin is lost, cells multiply uncontrollably and tumors arise [

5,

6]. NF1 exhibits high clinical heterogeneity, even among family members, which complicates diagnosis and the implementation of effective treatments [

7].

Clinically, NF1 manifests in a multisystemic manner. Axillary or inguinal freckling, café-au-lait spots, typical bone lesions (such as scoliosis), neurofibromas, optic gliomas, and iris hamartomas are some of the common features [

8]. Other systems affected include cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal. Patients also present an increased risk of learning difficulties, intellectual disability, autism spectrum symptoms, aqueductal stenosis, pheochromocytoma, vascular dysplasia, and cancer [

9].

Clinical expression is age-dependent, making it necessary to provide tailored follow-up from childhood to adulthood to identify and manage complications such as optic pathway gliomas and plexiform neurofibromas [

10].

Spinal manifestations are particularly relevant, potentially including severe bone deformities, neuropathic pain, and motor or sensory deficits arising from neurogenic tumors or soft tissue abnormalities [

11]. In patients with a high tumor burden, evaluation using advanced imaging techniques, such as volumetric tumor quantification and whole-body MRI, is essential. In terms of therapy, biological agents targeting the hyperactive RAS pathway are under investigation, while surgery remains a core component for managing tumors and deformities, requiring careful evaluation by a specialized multidisciplinary team [

11].

Molecular and genetic advances have improved understanding of NF1 pathophysiology, identifying factors that explain clinical variability, including tissue- and region-specific effects, sex differences, and germline genomic contributions [

6]. The availability of NF1 animal models, human pluripotent stem cells, and collaborative clinical trial networks offers robust opportunities for the development of targeted therapies. Additionally, NF1 serves as a model for studying molecular mechanisms associated with cognitive deficits and autism spectrum symptoms, allowing the identification of potential therapeutic targets and guiding preclinical and clinical pharmacological studies [

9].

Diagnosis has improved with updated clinical criteria, genetic testing, and detection of choroidal anomalies, enabling earlier intervention [

5] . In cases of mosaic NF[

1], comprehensive physical examination, blood and skin genetic testing, genetic counseling, and clinical surveillance are recommended (García-Romero et al., 2015) [

12]. Overall, NF1 is a complex, multisystemic disorder whose understanding and management have benefited from recent advances in molecular biology, diagnostics, and targeted therapies, offering promising prospects for comprehensive patient care.

NF1 is a genetic condition that causes tumors to develop on nerves and has a significant impact on the quality of life of both the patient and the caregiver [

13]. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is the most common variant, followed by NF2 and non-NF2 schwannomatosis (SWN); the latter two have specific symptoms such as neuropathic pain or hearing loss. Although there is currently no cure, targeted therapies and surgery can help alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life. [

13]. NF1 is currently recognized as a neurodevelopmental disorder with early onset, typically in childhood, characterized by cutaneous neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and skeletal abnormalities. In addition to its physical manifestations, NF1 is associated with long-term cognitive and behavioral consequences. These include deficits in visuospatial processing, executive function, and general cognition, as well as specific learning difficulties affecting mathematics, writing, and reading. [

2]. In addition, children with NF1 show a high prevalence of ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, and anxiety, along with an increased risk of depression and other psychiatric conditions. These alterations significantly impair academic achievement, social adaptation, and emotional development. Physical quality of life is related to disease severity, according to recent evidence. On the other hand, visible symptoms negatively affect the social and physical domains. Parents perceive that disease severity is associated with lower academic performance in their children [

14]. Given these challenges, the CABIN Task Force underscores the importance of defining NF1-specific neurobehavioral phenotypes, adapting and standardizing assessment tools, and conducting longitudinal natural history studies to identify optimal periods for early detection, risk assessment, and the prevention or mitigation of cognitive and behavioral delays [

15]. In this context, the early recognition of neurodevelopmental difficulties is essential to initiate personalized interventions that foster comprehensive development and improve the quality of life of children with NF1 and their families [

2,

14].

Deficits in EF constitute a core feature in children with NF1, regardless of other cognitive or clinical variables, as consistently demonstrated by scientific evidence. The systematic review and meta-analysis by [

16], based on a sample of 805 children with NF1 and 667 controls, confirms that EF impairments are significant in this population, with greater difficulties in working memory and planning, and milder deficits in inhibition and cognitive flexibility. These problems tend to worsen with age, regardless of intellectual level or the presence of ADHD. Complementarily, [

17], in their evaluation of 42 children with NF1 compared to typically developing peers and children with ASD, observed that although IQ and autistic symptoms influence EF, the difficulties identified cannot be explained solely by these variables, reinforcing their intrinsic nature to NF1.

As a neurodevelopmental disorder, NF1 entails a high risk of cognitive difficulties, learning problems, attentional deficits, social impairments, and psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression. Its manifestations frequently overlap with ADHD and ASD. Although extensive research has addressed cognitive and behavioral difficulties in NF1, studies in preschool populations remain scarce. Along these lines, [

16] reported significant impairments in working memory and planning, with milder problems in inhibition and flexibility, which tend to worsen with age and are largely independent of variables such as IQ, ADHD status, or assessment type. Similarly, Torres Nupan et al. [

18] identified broad deficits in language, reading, visuospatial and motor skills, EF, attention, behavior, emotions, and social functioning, along with a high prevalence of ADHD and autistic traits. Moreover, brain MRI abnormalities were associated with lower cognitive performance and showed predictive value for these difficulties.

Although current EF assessments often focus on behavioral symptoms, some authors emphasize the importance of addressing the neurobiological underpinnings. Smith, Kaczorowski, and Acosta [

19] propose a multidimensional approach integrating genetic, clinical, and behavioral data, while Huijbregts et al. [

20] highlight the relevance of cortical and subcortical regions in relation to attention problems, social limitations, and autism-like behaviors.

The correlation between academic performance and EF is also well established. According to Weiss and Raber (2023) [

21], between 50% and 70% of children with NF1 exhibit behavioral and cognitive problems, including deficits in EF, even in the absence of structural brain abnormalities or tumors. Likewise, Payne et al. [

22] demonstrated that both NF1 children with and without ADHD show deficits in spatial working memory and response inhibition, confirming that EF impairments are inherent to NF1 and not dependent on ADHD comorbidity.

Finally, several studies document the persistence of EF difficulties into adulthood. Wang et al. [

23] identified deficits in the executive control network, while the alerting and orienting networks remained intact, suggesting that attention problems in NF1 are primarily underpinned by deficits in executive control across the lifespan.

The literature generally emphasizes the importance of early detection and targeted intervention on EF to reduce its impact on learning, social adaptation, and quality of life in individuals with NF1. EF impairment is common in children with NF1 and may be a risk factor for developing executive dysfunction, as well as for presenting with ADHD and ASD.

Although NF1 is frequently associated with comorbidities such as ADHD and ASD, executive deficits constitute a transversal marker present in multiple neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., ADHD, ASD, learning disorders, SLI/DLD, FASD) and in adulthood (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, dementias, Parkinson’s, substance use disorders) [

24]

As Elliott [

25] emphasizes, executive functions are complex cognitive processes requiring the coordination of several subprocesses, closely linked to frontal cortex functioning. Executive dysfunction appears in a wide range of neurological and psychiatric conditions, generally associated with frontal pathology. Neuroimaging studies (PET, fMRI) have confirmed this relationship, although they have not succeeded in localizing specific executive functions to isolated prefrontal regions. Instead, executive functioning appears to depend on dynamic and flexible brain networks, which explains both the clinical variability of executive deficits and the possibility of partial recovery after brain injury, due to functional reorganization within these networks. Research on executive functions highlights the importance of examining and addressing these abilities in real-life situations, particularly in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders or brain injuries. In this context, the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) has become a key tool for ecological assessment, as it measures how executive functions impact daily life and supports the planning of targeted interventions. Following Mark Ylvisaker’s approach [

26], executive function assessment should be pragmatic, context-sensitive, and focused on real-world performance, offering a more accurate picture of a child’s difficulties than traditional neuropsychological tests.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the BRIEF’s utility across various clinical populations. Andersen et al. (2024) [

27] examined adolescents with ADHD receiving medication and identified substantial executive function deficits through parent, teacher, and self-reports, with notable differences in agreement among informants. Teachers reported the highest levels of difficulty, while adolescents self-reported fewer deficits, underscoring the importance of tailoring interventions to observed challenges and considering the child’s insight into their own difficulties. Similarly, [

28] found that an equine-assisted occupational therapy program (STABLE-OT) significantly enhanced executive function in children with ADHD, as reflected in both the global and metacognitive indices of the BRIEF, as well as improvements in daily functioning and occupational satisfaction.

Mohamed et al. (2018) compared parental BRIEF reports with formal neuropsychological assessments (D-KEFS) in children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Their findings indicated that both approaches detected executive function deficits, but each captured different aspects of executive functioning in clinical versus everyday settings, highlighting the complementary role of these measures in obtaining a holistic understanding of a child’s difficulties.

Research in NF1 further supports the relevance of the BRIEF. Remaud et al. [

29] assessed executive function in 64 children with NF1 aged 7–16 using both the CEF-B battery and BRIEF questionnaires, identifying significant deficits across all domains in objective tests and parent/teacher ratings. Although ADHD did not affect performance on objective tests, it influenced adult perceptions, emphasizing the value of combining objective and contextual assessments. Doser et al. [

30] reported similar findings, confirming that NF1 has a profound impact on executive function and that evaluations should integrate multiple sources for a comprehensive understanding.

This body of evidence underscores the BRIEF’s value as a reliable, ecologically valid instrument for evaluating executive functions, informing individualized interventions, and improving daily functioning in children and adolescents across diverse neurodevelopmental and clinical contexts.

The BRIEF-P (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Preschool Version) [

31] is a questionnaire used to assess executive functions in children aged 2 to 5 years and 11 months. It is administered through reports from parents, teachers, or caregivers who have been in contact with the child for at least six months. Derived from the original BRIEF [

32], it is based on models that conceptualize executive functions as an interconnected set of processes responsible for directing behavior and cognitive activity toward specific goals, with a particular focus on self-regulation. This instrument is sensitive to the neuropsychological developmental plasticity of early childhood and is intended for children with executive function impairments of various etiologies, such as language disorders, ADHD with and without hyperactivity, low birth weight, NF1, specific language impairment, Down syndrome, hearing impairment, and type 1 glutamic acid disorder [

8,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]

The BRIEF-P consists of 63 items organized into five clinical scales—Inhibition, Flexibility, Emotional Control, Working Memory, and Planning/Organization—three composite indices—Inhibitory Self-Control, Flexibility, and Emerging Metacognition—one Global Executive Composite, and two validity scales (Negativity and Inconsistency). Assessment uses a three-point Likert scale (never, sometimes, often) in response to the question, “How often have these behaviors been a problem compared to other children of the same age?” Administration takes approximately 10 to 15 minutes, making it a brief, structured, and easy-to-administer instrument with high ecological validity, as it allows observation of behaviors in the child’s natural contexts, such as home and school.

Studies employing the BRIEF-P demonstrate its utility in detecting executive function difficulties across diverse pediatric populations. For example, Maiman et al. [

43] found that in preschool children with epilepsy, the most frequently impaired indices were Emerging Metacognition (59%) and the Global Executive Composite (43%), highlighting problems in working memory, inhibition, and planning/organization. Similarly, Garon, Piccinin, and Smith [

44] showed that parent ratings on the BRIEF-P significantly correlated with direct laboratory measures of executive functions, supporting its validity as an early detection tool. Additionally, Likhitweerawong et al. [

45] reported that difficulties in inhibition and working memory assessed with the BRIEF-P were associated with a higher risk of overweight or obesity in preschool children, underscoring the relevance of these executive functions for child health. Overall, this evidence highlights that the BRIEF-P is a reliable and clinically relevant instrument for assessing and monitoring executive functions in early childhood, useful for both research and clinical practice.

Research on EF in children with NF1 highlights the importance of assessing these skills from an early age using complementary approaches. Beaussart-Corbat et al. [

46] evaluated EF in children aged 3 to 5 years through performance-based tests and BRIEF-P questionnaires, finding deficits in five out of seven tasks and elevated concerns reported by parents and teachers. The weak correlation between test and questionnaire results underscores the need to combine both methods from the earliest stages of development. Consistently, Gilboa et al. [

47] demonstrated that children with NF1 perform worse on EF tasks and that executive functions can predict academic success, reinforcing the importance of early and targeted interventions for this population. Overall, these findings emphasize that comprehensive assessment of EF, integrating both objective and contextual measures, is essential for identifying difficulties and guiding educational and cognitive support strategies from childhood.

Simmons, Schmidt, Lancaster, and Van Allen [

48] examined the role of executive function in the relationship between future-oriented thinking and exercise intention in adolescents. Using a sample of 101 participants aged 11 to 17, self-report questionnaires were administered to assess consideration of future consequences, exercise intention, and executive function (BRIEF-2) [

49]. The results indicated that executive function significantly mediated the relationship between future-oriented thinking and exercise intention, even when controlling for age and subjective socioeconomic status. These findings suggest that, in addition to promoting future-oriented thinking, interventions aimed at improving executive function could enhance motivation for physical activity during adolescence.

Research on adult executive functions highlights the utility of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult Version (BRIEF-A) [

50] for identifying and understanding deficits in real-world contexts across different populations. Biederman et al. [

51] examined BRIEF-A in a sample of 1,090 adults aged 18 to 55 with ADHD, using the Global Executive Composite (GEC) with a cutoff ≥70 to classify EF. They found that 44% of adults with ADHD met criteria for EF, displaying more severe ADHD symptoms, higher psychopathology, emotional dysregulation, greater mind wandering, more autistic traits, and poorer quality of life than those without EF. No significant differences were found by age, sex, or race, highlighting BRIEF-A’s utility in identifying a clinically meaningful subgroup of adults with ADHD whose executive deficits contribute significantly to disability beyond the core diagnosis.

Similarly, Kim et al. [

52] used the BRIEF-A to examine self-reported executive function difficulties in adults born very low birthweight (VLBW, <1500 g) at ages 23 and 28, compared with full-term controls. Adults born VLBW showed persistent impairments in behavioral regulation, metacognition, and global executive functioning. These deficits were associated with lower socioeconomic status and reduced likelihood of home ownership, even after controlling for sex, ethnicity, and parental socioeconomic background, indicating that executive function difficulties have long-term implications for life outcomes.

Olsson, Arvidsson, and Blom Johansson [

53] explored the interpretation of BRIEF-A items by informants of adults with severe aphasia. Cognitive interviews revealed that responses often varied in interpretation, influenced by expectations and observable performance rather than actual executive ability. This study underscores that BRIEF-A results should be interpreted cautiously in populations where communication impairments may confound ratings.

Finally, Adler et al. [

54] evaluated the effects of atomoxetine on executive function in young adults with ADHD using the BRIEF-A in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Participants receiving atomoxetine showed significant improvements in the Global Executive Composite (GEC), Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI), Metacognition Index (MI), and several subscales including inhibition, self-monitoring, working memory, planning/organization, and task monitoring, demonstrating BRIEF-A’s sensitivity to treatment-related changes in executive function.

Together, these studies support the BRIEF-A as a reliable, ecologically valid tool for assessing executive function in adults, capturing both deficits and treatment effects, while emphasizing the need to consider context, informant perspective, and population-specific factors when interpreting results.

The purpose of our research was to determine the level of executive function impairment in individuals diagnosed with NF1, focusing on studies that used the various versions of the BRIEF to assess this cognitive domain [

32,

50,

55]. We focused on executive functioning because multiple studies have identified deficits in this area as one of the most consistent and relevant neuropsychological characteristics in patients with NF1, with direct implications for their academic performance and daily functioning. The use of the BRIEF is justified because it provides standardized and ecologically valid assessments of executive functioning in everyday contexts [

26], allowing for the comparison of studies and the extraction of homogeneous data for a more robust meta-analysis. This methodological approach facilitates quantifying the magnitude of executive function deficits and synthesizing the existing evidence accurately . It is important to emphasize that the choice of the BRIEF is based solely on scientific and methodological criteria, ensuring the validity and comparability of the results.

2. Materials and Methods

Assessment of executive function in individuals with NF1, according to the method defined by the principles of the PRISMA statement. [

56]. This protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO under the number 2025 CRD420251107406. The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) to ensure that the entire review process maintained transparency and methodological rigor.

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/myprospero

The protocol includes detailed information on the review objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategy, databases consulted, study selection and data extraction methods, risk of bias assessment, and plans for data synthesis. Prospective registration minimizes the risk of post hoc modifications influenced by results and enhances the reproducibility of the research.

BRIEF: Versions (BRIEF-P, BRIEF-2, and BRIEF-A) and Characteristics

The original BRIEF [

57] included eight scales, organized into two indices: (i) Behavior Regulation Index: Inhibition, Shift, Emotional Control. (ii) Metacognition Index: Initiate, Working Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, and Monitor.

The BRIEF-P [

31] is a 63-item form to be completed by parents or teachers to assess the executive functions (EF) of preschool children as manifested in everyday behavior. It consists of the following clinical scales: Inhibition, Emotional Control, Plan/Organize, Shift, and Working Memory. These clinical scales are grouped into three broad indices: (i) Inhibitory Self-Control (Inhibition and Emotional Control). (ii) Flexibility (Shift and Emotional Control). (iii) Emergent Metacognition (Plan/Organize and Working Memory).

A revision of the BRIEF was published in 2015 (BRIEF-2; [

49]) as a result of a study by [

58], which revealed a new internal factor structure. Instead of two indices, Gioia et al.’s [

58] study found that BRIEF data better fit a three-factor structure, defined by three indices that include nine subdomains: (i) Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI): Inhibit, Self-Monitor. (ii) Emotional Regulation Index (ERI): Shift, Emotional Control. (iii) Cognitive Regulation Index (CRI): Initiate, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, Task-Monitor. These changes are reflected in the BRIEF-2 [

49].

BRIEF-A (Roth et al., 2005) [

59] includes composite scores that group different subscales: (i) Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI): Inhibit, Shift, Self-Monitor, and Emotional Control. (ii) Metacognition Index (MI): Initiate, Plan/Organize, Working Memory, Organization of Materials, and Task-Monitor.

In addition, all versions include a Global Executive Composite (GEC) that encompasses all the clinical scales. To identify participants with executive functioning impairment, a cutoff score of T ≥ 65 on the Global Executive Composite was used.

Previous validation studies of the BRIEF have shown that the self-report and informant-report versions do not always yield significantly similar scores [

27,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64] Although both formats are designed to assess the same executive function domains, self-reports typically reflect the individual’s subjective perception of their own functioning, whereas parent or teacher reports capture observable behaviors in everyday contexts. Consequently, discrepancies between the two sources are common and, rather than being interchangeable, they provide complementary information (Gioia et al., 2000; Roth et al., 2005).

A comparison between the structures of BRIEF, BRIEF-P, BRIEF-2, and BRIEF-A is presented in

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria of the Studies and Selection Process

The PICOS strategy (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes, Study design) was used [

65]. This protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO with the reference 2025 CRD420251107406. To ensure that the review process maintained transparency and methodological rigor, the review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews):

(i) Participants: Children and adolescents (under 18 years of age) who are survivors of and/or affected by a pediatric brain tumor and/or who were exposed to oncological treatments during the fetal period.

(ii) Exposure: Individuals who have been exposed to a brain tumor during childhood and/or to oncological treatments in the fetal period.

(iii) Comparison: Deficits in executive functioning compared to individuals who were not exposed to a brain tumor in childhood and/or oncological treatment in the fetal period.

(iv) Outcomes: Executive functioning profile assessed using the BRIEF scales (self-report and/or informant report), including BRIEF, BRIEF-P, and BRIEF-2.

(v) Studies: Descriptive studies (pediatric brain tumor survivor group) and comparative-causal studies (control group versus pediatric brain tumor survivor group).

For this systematic review, studies were selected based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure relevance to the research question and methodological consistency. Research focused on individuals under 18 years of age, both male and female, who had been exposed to a brain tumor during childhood or to oncological treatments during the fetal stage was included.

Only studies that assessed executive functioning using the BRIEF scales, in any of their versions or translations, were considered. The choice of the BRIEF is based on its ability to provide standardized and ecologically valid assessments of executive function in everyday contexts, facilitating comparisons across studies and the extraction of homogeneous data for analysis. This decision is based exclusively on methodological and scientific criteria, ensuring the validity, comparability of results, and robustness of the meta-analysis, without any commercial interests. In summary, this approach allows for precise quantification of executive function deficits and reliable synthesis of the available evidence, thereby fulfilling the study’s stated objectives.

Eligible study designs were ex post facto investigations, including descriptive and comparative-causal studies. Studies involving adults, individuals exposed to tumors unrelated to the brain or central nervous system, assessments of executive functioning using instruments other than the BRIEF, and single case reports were excluded. In the development of this review, inclusion and exclusion criteria were established, as summarized in

Table 2:

Search Strategy

Following the guidelines established by the PRISMA statement [

56]. To this end, the databases PubMed, Springer Link, and Scopus were consulted, selecting articles published from 2010 to March 2024. The search strategy used is included in

Appendix A.

A bibliographic search was carried out in the first phase using the English terms “cancer,” “tumor,” and “executive function.” Afterwards, the studies were classified according to tumor type, and those with an NF1 diagnosis were selected for the meta-analysis. A total of 78.933 articles were retrieved, allowing for tracking the evolution of research on the topic. In the second stage, specific filters unique to each database were applied: full text, empirical studies, English or Spanish language, and open access. Studies were limited to open access to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and data availability, although this may exclude relevant paid research.

The study selection process was conducted in two stages. First, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified records to assess potential eligibility. Subsequently, the full texts of selected studies were reviewed to determine final inclusion based on the predefined criteria.

Data collection was carried out using a data extraction form that had been previously designed and pilot-tested. Two reviewers independently obtained the relevant data from each included study. The extracted data covered study characteristics (author, year, country, design), participant information, interventions, comparators, measured outcomes, and the quantitative data required for the meta-analysis. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or, when necessary, by consulting a third reviewer.

Included Studies

A total of 48 studies were selected as the basis for the present review. Among these, studies with an NF1 diagnosis were selected [

22,

36,

46,

66,

67,

68]. The included studies are presented in

Appendix B.

The six reviewed studies included approximately 4.488 children with NF1 and 2.922 controls (unaffected siblings or healthy children from the community), covering an age range from 3 to 16 years. NF1 diagnoses were established in all cases according to NIH criteria (1987/1988) and confirmed by specialized geneticists or neurologists. Control groups were carefully selected to ensure comparability, using healthy volunteers, schoolchildren, and, in the larger studies, unaffected siblings, which allowed for controlling the influence of family and socioeconomic factors. Common exclusion criteria included the presence of other neurological or psychiatric conditions, severe sensory deficits, intellectual disability, use of stimulant medication (particularly in cases of ADHD), and insufficient proficiency in the assessment language. Some studies reported relevant cognitive differences, such as significantly lower IQ in children with NF1. In the studies by Gilboa et al. [

47] and Payne et al. [

22], a significant percentage of children with NF1 were found to have ADHD (17.25% and 7.9%, respectively, although the latter may underestimate the true prevalence due to exclusions for medication).

A brief descriptive summary of the six studies included in the meta-analysis is provided.

(i) The study by Beaussart-Corbat et al. [

46], published in the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, was conducted in France and evaluated a group of children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) (n=33) and a control group (n=52) between 3 and 5 years of age, with mean ages of 56.67 ± 11.27 months for the NF1 group and 55.75 ± 10.37 months for the control group. The sex distribution was 17/16 male/female in the NF1 group and 27/25 in the control group. The study methodology causally compared the differences between the two groups, using BRIEF-P and Intellectual Competence assessed with the WPPSI-IV as dependent variables. The BRIEF-P was completed by both parents and teachers. The specific results indicated that, according to parents, differences were observed in flexibility and inhibition, whereas according to teachers, differences were found in global executive functioning, inhibition, and emotional control. The study was included in a meta-analysis, and both parents and teachers served as informants.

(ii) The study by Casnar and Klein-Tasman [

66], published in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology, was conducted in Wisconsin, USA, and included a group of children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) (n=26) and a control group (n=37). The mean age of participants was 4.53 ± 0.87 years for the NF1 group and 4.51 ± 0.89 years for the control group. The sex distribution in the NF1 group was 17 males (65%) and 9 females (34%), while in the control group it was 23 males (62%) and 14 females (38%). The methodology followed a comparative-causal design, considering group (NF1 vs. control) as the independent variable and executive functioning, assessed with the BRIEF-P, as the dependent variable. The results showed differences in executive functioning among children with NF1. The instruments used were BRIEF-P questionnaires completed by parents, who served as the primary informants. The study was included in a meta-analysis.

(iii) The study by Gilboa et al. [

47], published in Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, was conducted in Israel and included a group of children with Neurofibromatosis Type I (NF1) (n=29) and a control group (n=27). The mean age was 12.3 ± 2.6 years for the NF1 group and 12.4 ± 2.5 years for the control group. The sex distribution in the NF1 group was 8 males and 21 females, while in the control group it was 8 males and 19 females. The methodology followed a comparative-causal design, considering group (NF1 vs. control) as the independent variable and executive functioning assessed through BADS-C, BRIEF completed by parents, and ACES Teacher as dependent variables. The results indicated that executive functioning assessed by parents acted as a predictor of academic performance. The instruments included BRIEF-Parents, with parents serving as the main informants. The study was included in a meta-analysis.

(iv) The study by Lorenzo et al. [

36], published in The Journal of Pediatrics, was conducted in Australia and included a group of children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) (n=43) and a control group (n=43). The mean age of participants was 40.23 ± 0.72 months for the NF1 group and 40.16 ± 0.48 months for the control group. The sex distribution was identical in both groups: 32 males (74%) and 11 females (26%). The methodology followed a comparative-causal design, considering group (NF1 vs. control) as the independent variable and BASC-II, BRIEF-P, and CADS-P as dependent variables. The specific results from the BRIEF-P completed by parents allowed for the evaluation of the cognitive and executive profile of preschoolers. Parents were the main informants. The study was included in a meta-analysis.

(v) The study by Maier et al. [

69], published in Child Neuropsychology, was conducted in Australia and included a control group (n=55) and a group of children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) (n=191), subdivided into NF1 Typical (n=41), NF1 Borderline (n=30), and NF1 Impaired (n=120). The mean age was 11.81 ± 2.61 years for the control group, 10.38 ± 2.36 years for the total NF1 group, 11.61 ± 2.75 years for the NF1 Typical subgroup, 9.98 ± 2.29 years for NF1 Borderline, and 10.06 ± 2.11 years for NF1 Impaired. The sex distribution was as follows: control group 22 males (40%), total NF1 group 104 males (54.45%), NF1 Typical 27 males (65.85%), NF1 Borderline 13 males (56.67%), and NF1 Impaired 64 males (53.33%). The methodology followed a comparative-causal design, considering group (NF1 vs. control) as the independent variable and RCFT, IQ, visuospatial abilities, BRIEF, Tower of London, and The Conners ADHD DSM-IV Scales (CDAS) as dependent variables. The results from the BRIEF completed by parents allowed for the evaluation of global executive functioning in children with NF1. Parents served as the main informants, and the study was included in a meta-analysis.

(vi) The study by Payne et al. [

22], published in Child Neuropsychology, was conducted in Australia and included a group of children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) (n=168) and a control group (n=55), with ages ranging from 6 to 16 years. The mean age was 10.62 ± 2.28 years for the NF1 group and 11.24 years for the control group. In the NF1 group, the sex distribution was 108 males and 91 females, while for the control group these values were not specified. The methodology followed a comparative-causal design, considering group (NF1 vs. control) as the independent variable and the evaluation of executive functioning and attention through BRIEF, Conners’ ADHD DSM-IV Scales (CADS), and the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children–Third or Fourth Edition (WISC-III/WISC-IV) as dependent variables. The BRIEF instruments completed by parents and teachers indicated significant differences in attention. The study was included in a meta-analysis, and both parents and teachers served as informants.

Data Items

Data were collected on executive functions assessed using the BRIEF (including versions such as BRIEF-P, BRIEF-2, and forms completed by parents, teachers, preschoolers, or by the individuals themselves)

The meta-analysis was conducted using the available and published data from the six studies analyzed and described in the manuscript. The scores obtained from the clinical scales and indices were used exactly as published by the authors in the cited publications.

The data were collected on executive functions assessed using the BRIEF, specifically the preschool (BRIEF-P) versions, completed by parents and teachers as appropriate. The adult version (BRIEF-A) was not included, as it is specifically designed for adult populations.

Key outcomes included the Global Executive Composite (GEC), Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI), Metacognition Index (MI), and specific subscales (e.g., inhibition, working memory, cognitive flexibility). Only T-scores were included to ensure comparability across studies. Means and standard deviations per domain were extracted when these were provided by the original authors in the publications.

Data were collected on: (i) Participants: age at diagnosis or assessment, sex; (ii) Studies: country, study design, and methodology; (iii) Instrument: version of the BRIEF used, source of the report (parent, teacher, self-report), language and validation in the study population; (iv) Meta-analysis: sample size, group means and standard deviations, and alternative statistics (e.g., Cohen’s d).In cases of missing data, it was assumed that the informant was a parent if the BRIEF was administered in a home setting, or a professional if administered in a clinical context.

Bias assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale tool was chosen. [

70]. The selected articles present a low risk of bias (see

Table 3).

Effect Measures

For each outcome assessed (BRIEF indices and subscales), the effect measure used in the synthesis was the Standardized Mean Difference (SMD). This measure allows for comparison of effect size between groups (patients with NF1 vs. controls). When available, 95% confidence intervals were reported for each estimate.

Eligible studies for the meta-analysis were selected based on comparisons between NF1 and healthy control groups, and inclusion of BRIEF T-scores with measures of dispersion. Data were standardized using only T-scores and organized by BRIEF domains (GEC, BRI, MI, and subscales).

Synthesis Methods

Study results were summarized in tables and visualized through forest plots. A random-effects meta-analysis was performed using Standardized Mean Differences (SMD), with heterogeneity assessed via the I² statistic.

Subgroup analyses were considered to explore heterogeneity (e.g., BRIEF version, informant type, Clinical scales and indices). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of findings by excluding high-bias studies of extreme samples.

A meta-analysis was conducted using the SPSS program (Meta-analysis module) (version 29.0.2.0).

For quantitative variables, mean differences were used.

Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).

A Cohen’s d effect size in the range of [0.2 – 0.35] was considered small, [0.35 – 0.65] moderate, and > 0.65 large. Statistical inferences were based on the analysis of 95% confidence intervals (CI). A random-effects model was chosen, assuming that effects are not the same across all studies.

We conducted the meta-analysis despite the limited number of studies (N = 6) and the high heterogeneity, given the clinical significance of executive function deficits in NF1. This approach allows for a quantitative synthesis of the existing evidence and facilitates comparisons across studies using different versions of the BRIEF. The random-effects model was deemed appropriate, as it accounts for true variability between studies rather than mere sampling error, enabling the identification of consistent patterns in executive function deficits.

The risk of publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots generated for outcomes with at least 10 studies. In addition, Egger’s test was applied to detect asymmetry in the plots, which may indicate the presence of publication bias or bias due to missing results.

The certainty of the evidence for the main outcomes can be rated as moderate, primarily due to limitations related to risk of bias and imprecision in the data. Nevertheless, the findings provide a solid and clinically meaningful foundation for interpreting the results and guiding future research.

3. Results

The studies were screened by first reading the titles and eliminating those unrelated to the research objective. Subsequently, a second screening was conducted by reading the abstracts to assess their suitability according to the previously established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

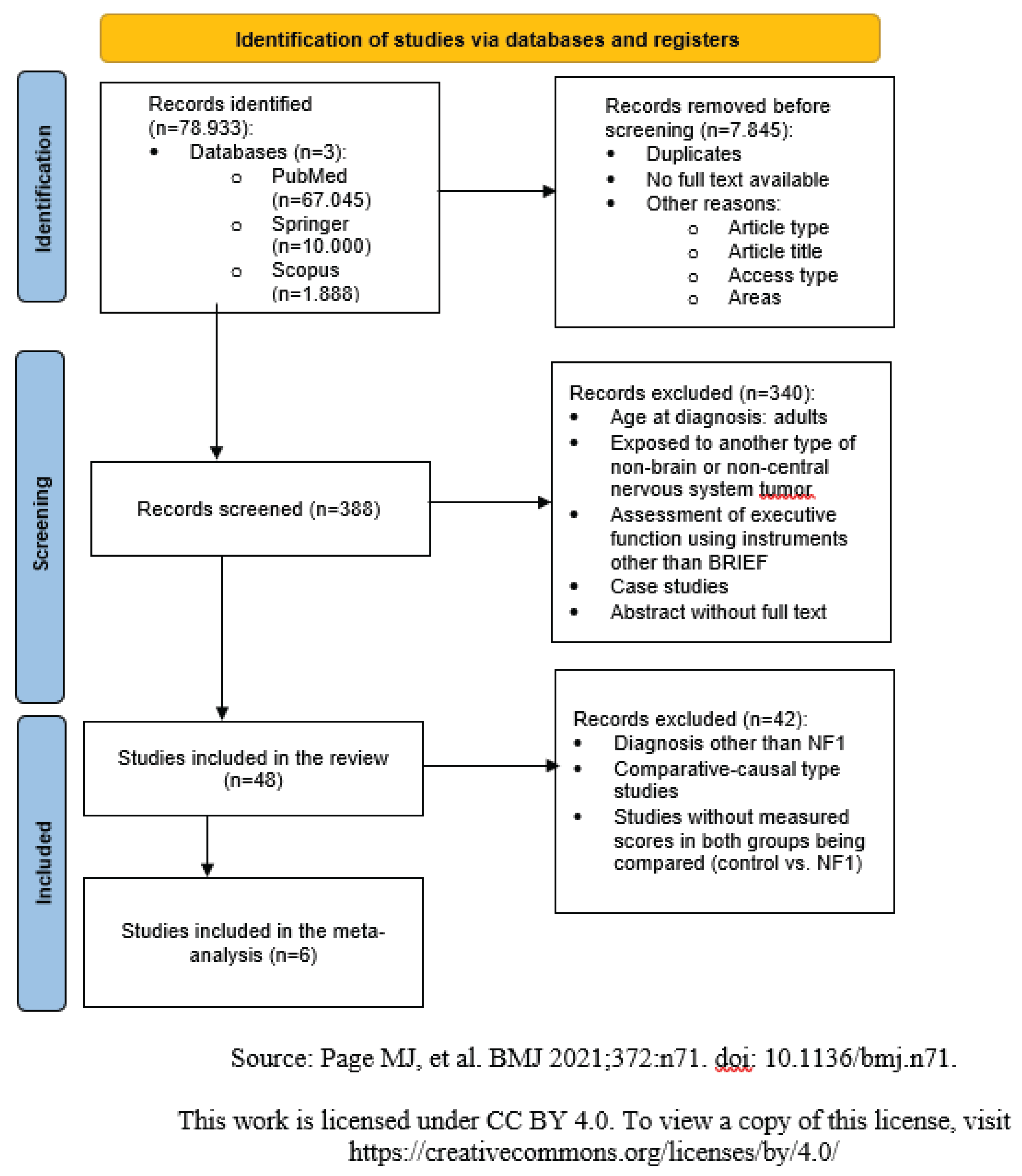

Figure 1 shows the study screening process, starting from 78.993 studies, with 6 studies selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

In the identification phase, a total of 78.933 records were retrieved from three databases: PubMed (67.045), Springer (10.000), and Scopus (1.888). Before proceeding to the selection, 7.845 records were removed for various reasons, including duplicates, lack of full-text access, article type, access type, and subject area.

In the screening phase, 388 records were assessed, of which 340 were excluded due to reasons such as adult age at diagnosis, presence of tumors not related to the central nervous system, use of instruments other than the BRIEF for executive function assessment, case studies, or lack of full-text access.

In the review inclusion stage, 48 studies remained. However, 42 records were subsequently excluded due to diagnoses other than NF1, study designs different from comparative-causal, or absence of data that allowed comparison between groups (controls vs. NF1).

Finally, in the quantitative synthesis phase, 6 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Effect Measures

Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated from data of 6 studies that used the BRIEF (in different versions) in 4.488 NF1 patients and 2.922 controls.

Table 4 presents the detailed meta-analysis results for subgroups based on the different clinical scales and indices, informant, and BRIEF version.

Individuals with NF1 showed overall moderate executive deficits compared to the community sample (d = 0.606; p = 0.000; 95% CI 0.513 – 0.699).

An analysis of the different clinical scales and indices shows that the significant executive deficits vary:

(I) Small but significant executive deficits compared to the community sample in: (i) Emotional Control (d = 0.314; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.127 – 0.501); (ii) Inhibitory Self-Control Index (d = 0.264; p = 0.039; 95% CI 0.014 – 0.514).

(II) Moderate significant deficits compared to the community sample in: (i) Inhibition (d = 0.498; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.310 – 0.687); (ii) Global Executive Functioning (d = 0.575; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.222 – 0.927); (iii) Organization of Materials (d = 0.521; p = 0.000; 95% CI 0.254 – 0.788).

(III) Large significant deficits compared to the community sample in: (i) Self-Monitoring (d = 1.031; p = 0.000; 95% CI 0.712 – 1.350); (ii) Metacognition Index (d = 0.949; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.681 – 1.218); (iii) Emerging Metacognition Index (d = 0.658; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.422 – 0.893); (iv) Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI) (d = 0.691; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.380 – 1.002); (v) Initiative (d = 0.750; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.479 – 1.020); (vi) Working Memory (d = 0.968; p = 0.000; 95% CI 0.803 – 1.132); (vii) Monitoring (d = 0.848; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.444 – 1.251); (viii) Planning/Organization (d = 0.715; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.501 – 0.929).

No significant deficit was found in the clinical Flexibility scale (d = 0.325) or Flexibility Index (d = 0.081).

(IV) An analysis of the different clinical scales and indices shows moderate significant executive deficits compared to the community sample when evaluated by: (i) Parents (d = 0.625; p = 0.000; 95% CI 0.527 – 0.724); (ii) Teachers (d = 0.494; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.218 – 0.771).

(V) An analysis of the different clinical scales and indices shows large significant executive deficits compared to the community sample when evaluated by BRIEF (d = 0.815; p = 0.000; 95% CI 0.715 – 0.915) and moderate deficits when evaluated by BRIEF-P (d = 0.381; p = 0.001; 95% CI 0.268 – 0.494).

Homogeneity and Heterogeneity

The heterogeneity test and the chi-square test were performed. Significant heterogeneity greater than 40% suggests the presence of heterogeneity [

71]. The presence and amount of statistical heterogeneity were assessed using the I² statistic, with significance set at

p < .10 [

17] (see

Table 5).

Heterogeneity was driven in the clinical scales and indices by: Flexibility (χ²₄ = 15.193; p = .004) (I² = 70.4%) and Global Executive Functioning Index (χ²₄ = 14.681; p = .005) (I² = 71.3%).

Heterogeneity was driven by: Parents (χ²₅₂ = 1635.862; p = .001) (I² = 68.4%) and Teachers (χ²₈ = 27.631; p = .001) (I² = 71.0%).

Heterogeneity was observed in the studies, driven by both the BRIEF (χ²₃₀ = 67.367; p = .001; I² = 56.2%) and the BRIEF-P (χ²₈ = 56.560; p = .002; I² = 47.2%). The overall model also showed significant heterogeneity (χ²₆₁ = 197.594; p = .001; I² = 69%).

The subgroup homogeneity test was significant for clinical scales and indices and for the different versions of BRIEF, indicating that the studies have heterogeneous results.

When examining the global clinical scales and indices, heterogeneity was significant (χ²₁₄ = 77.267; p = .001). In contrast, for the global informant scores, heterogeneity was not significant (χ²₁ = 0.770; p = .380). Finally, heterogeneity was significant when analyzing the global versions (χ²₁ = 31.759; p = .001).

This meta-analysis included effect sizes from 6 studies using the effect size index (Cohen’s d).

In the different forest plots, the mean (overall) effect size and its 95% confidence interval are shown at the bottom (d = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.51–0.70).

With a Cohen’s d of 0.61, according to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, this effect size reflects a moderate relevance (close to 0.61).

The homogeneity statistic reached statistical significance [Q(61) = 197.59, p = .000].

The subgroup homogeneity test for clinical scales and indices was significant [Q(14) = 77.27, p = 0.000].

The subgroup homogeneity test for informants was significant [Q(1) = 0.77, p = 0.038].

The subgroup homogeneity test for the different versions of BRIEF was significant [Q(1) = 31.76, p = 0.000].

The I² index was high, I² = 69% (considered substantial heterogeneity), and the between-study variance reached [τ² = 0.09 (τ = 0.3)].

Global Effect Size Test

The global effect test [z = 12.78, p = 0.00] is below 0.05. There are statistically significant differences in executive functioning between patients with NF1 and the community sample, with a clear trend of executive deficits in the NF1 participant group.

Publication Bias

It is reported that, to address potential publication bias, funnel plots have been included in the

Supplementary Materials at both the group and individual levels. However, the Egger test was not performed, since, according to the literature, this test is not recommended when the number of included studies is small, as is the case in our meta-analysis [

72]. As described in the literature on publication bias, although funnel plots allow for a visual assessment of bias, more objective methods such as Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s linear regression test may be unreliable when the number of studies is limited, potentially leading to misleading interpretations.

An Egger’s test of publication bias was conducted and was significant (Egger’s intercept=1.586;

p<.001). There are several possible explanations for funnel plot asymmetry such as the heterogeneity between studies [

73].

The results of Egger's test should be interpreted with caution, as smaller studies may be overestimating the reported effects.

The presented funnel plot (see Figures 3 and 4) allows for a visual assessment of the potential presence of publication bias in the analyzed studies, using effect size (Cohen’s d) as the main metric.

The distribution of the points around the estimated overall effect size (central line) suggests that: most studies cluster near the center, indicating a reasonable consistency in the reported effect sizes. No marked asymmetry is observed, which is a good indication that there is no evident publication bias. Studies with a larger standard error (i.e., smaller sample size) tend to be more dispersed, as expected, but without a systematic skew toward positive or negative effects.

Overall, the plot suggests that the observed effect sizes are moderate to large across several categories, and that the evidence does not indicate significant distortion due to publication bias. This reinforces the validity of the findings and the robustness of the estimated overall effect.

In this case, the points represent individual studies classified by different dimensions of executive functioning and self-regulation, such as Self-Monitoring, Emotional Control, Flexibility, Metacognition, among others.

The distribution of the points around the estimated overall effect size (central line) suggests that most studies cluster near the center, indicating a reasonable consistency in the reported effect sizes. No marked asymmetry is observed, which is a good indication that there is no evident publication bias. Studies with a larger standard error (i.e., smaller sample size) tend to be more dispersed, as expected, but without a systematic skew toward positive or negative effects.

Overall, the plot suggests that the observed effect sizes are moderate to large across several categories, and that the evidence does not point to significant distortion due to publication bias. This reinforces the validity of the findings and the robustness of the estimated overall effect.

4. Discussion

This meta-analytic review examines executive functioning in individuals with NF1 who were assessed using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF).

It is important to highlight from the outset that the choice of the BRIEF is based exclusively on scientific and methodological criteria, which ensures the validity and comparability of the results. The use of the BRIEF is justified because it provides standardized and ecologically valid assessments of executive function in everyday life contexts [

26], allowing for comparisons across studies and the extraction of homogeneous data for a more robust meta-analysis.

The present meta-analysis aimed to investigate the magnitude of executive function deficits in individuals diagnosed with NF1, focusing exclusively on studies that used the BRIEF in its various versions with children, school-aged populations, and adolescents. This methodological choice allowed us to ensure data homogeneity and obtain an ecologically valid assessment of executive function in everyday contexts (school vs. family environment). Six studies were analyzed, including 4.488 individuals diagnosed with NF1 and 2.922 individuals belonging to control groups.

The results of the meta-analysis confirm that patients with NF1 present significant impairments across multiple domains of executive function, with deficits of moderate to high magnitude, except in the case of flexibility, where no significant differences were observed compared to controls. These findings provide solid and quantified evidence of one of the most consistent neuropsychological features of NF1, with direct implications for the academic and daily functioning of affected individuals. At the same time, these results underscore the relevance of considering assessment tools such as the BRIEF to guide future research and the design of clinical interventions.

The findings support the need to incorporate the assessment of executive functions (EF) as an essential component in clinical characterization and in the design of specific interventions, in line with the recommendations of Smith et al. [

74].

These results emphasize the importance of early assessment of executive functioning in patients with NF1, as suggested by Ferner et al. [

75], to detect the first signs of executive dysfunction.

Identifying executive deficits in individuals with NF1 at an early stage and providing educational and neuropsychological support is crucial to prevent them from significantly affecting academic performance, as well as personal and professional life. Moreover, better executive functioning is associated, for instance, with greater engagement in health-protective behaviors and lower involvement in risk-taking behaviors typical of adolescence [

76].

We focused on the study of executive functioning because multiple studies [

22,

74,

77,

78] have identified deficits in this area as one of the most consistent and relevant neuropsychological features in patients with NF1, with direct implications for their academic performance and daily functioning.

The results of this meta-analysis, in general terms, are consistent with the findings observed in previous research regarding the magnitude of executive deficits [

46]. Nonetheless, our most significant finding was a non-significant deficit in flexibility in individuals with NF1 compared to controls, which differs notably from the existing literature [

74].

Small but significant deficits were identified in emotional control and inhibitory self-control, indicating that these areas are affected, although their impact is relatively limited.

Moderate deficits were observed in inhibition, overall executive functioning, and organization of materials, suggesting that these functions have a more consistent impact on daily life and on academic or organizational performance [

79,

80].

The most pronounced deficits were found in self-control/self-monitoring, metacognition, behavioral regulation, initiative, working memory, monitoring, and planning/organization. Difficulties in NF1 are mainly concentrated in planning, self-regulation, working memory, and metacognitive skills—areas that can significantly affect autonomy, academic performance [

81], quality of life [

82], and adaptive behavior [

83,

84,

85].

Finally, no significant deficits were found in cognitive flexibility, indicating that the ability to adapt to changes or new strategies remains relatively preserved in this group. [

74] note that cognitive flexibility in individuals with NF1 is affected, although deficits are of small magnitude. Working memory and inhibitory control contribute to this ability, which enables task-switching, adopting different perspectives, and applying diverse approaches to problem-solving.

The findings on flexibility, although unexpected, should not be interpreted as contradictory to previous studies, since they are based on a meta-analysis of the existing literature.

The executive deficits exhibited by individuals with NF1 confirm the diversity of executive functioning profiles and their magnitude depending on the domains assessed, reflecting clinical variability and the need for an individualized diagnostic and therapeutic approach. These results are consistent with the study by Rabinovici, Stephens, and Possin [

86].

The brain networks involved in executive functioning extend beyond the frontal lobe, which is typically altered in neurodegenerative, neurological, psychiatric, and systemic disorders. This helps explain why not all executive dimensions are equally affected. Hoffmann [

87] suggests understanding the dysexecutive syndrome within the broader framework of frontal network syndromes (FNS), emphasizing that they are not confined to the frontal lobe but may originate in multiple brain regions due to their extensive connectivity.

Executive function impairments can be considered a transdiagnostic marker present across multiple disorders (Bausela, in press). For example, studies [

88,

89,

90,

91] suggest that ASD is associated with deficits in cognitive flexibility and ADHD with deficits in response inhibition, although findings are mixed.

The biological hypothesis of atypical development of fronto-subcortical circuits in childhood with NF1, in which the prefrontal cortex and its connections are fundamental, is supported by the results of the meta-analysis. These findings are in line with those reported by Beaussart-Corbat et al. [

46] and underscore the need for early assessment as well as further exploration of these circuits through neurophysiological studies.

The executive function difficulties observed in individuals diagnosed with NF1 have a transversal impact on academic, motor, and social performance [

46,

74].

Children with NF1 have difficulties in several areas of EF, as demonstrated by [

22,

78]. These deficits are observed both in their daily functioning and in performance on laboratory-based tests.

Executive dysfunction requires specific, ecological clinical and neuropsychological assessment, and its management must focus on the underlying cause with personalized interventions [

86].

To our knowledge, this is the first review and meta-analysis focused exclusively on studies using a single instrument; only studies that employed the BRIEF [

57] in its various versions to assess executive function in individuals with NF1 were included. The reason for including only BRIEF studies was to enable an ecologically valid assessment of executive functions, thereby ensuring homogeneity across the studies.

Regarding the BRIEF versions, this meta-analysis analyzed two versions: the original version and the preschool version, depending on the age range of the study sample. The results show that the BRIEF [

57] questionnaire demonstrates a large, reliable, and generalizable effect size, indicating clear and statistically significant differences in the variable analyzed. In contrast, the preschool version (BRIEF-P) [

31] shows a modest, weak, and less consistent effect, which limits its generalizability and increases the likelihood of null results in other contexts. Overall, the combined estimate suggests a moderate and significant effect, although the wide prediction interval reflects high variability across contexts and some uncertainty regarding replicability.

The results of the meta-analysis according to the BRIEF [

57] version used (BRIEF or BRIEF-P) show that executive deficits in individuals with NF1 vary depending on the assessment tool. Using the BRIEF[

57], large deficits were observed, whereas with the BRIEF-P deficits were moderate. This indicates that although the perceived severity of difficulties may depend on the version (preschool vs. school), executive function impairments are consistent and significant, highlighting the presence of meaningful difficulties in the daily and academic life of individuals with NF1.

The differences between BRIEF versions can be explained in light of the Miyake et al. [

92] model, since the development of executive functions progresses from a global and immature profile in preschoolers (less sensitivity in BRIEF-P) to a more differentiated and stable profile in school-aged children and adolescents (greater sensitivity and generalizability in the original BRIEF). These results are consistent with the developmental analysis of executive function trajectories conducted by Best and Miller [

93]. Best and Miller [

93] examined the development of executive functions from childhood through adolescence, highlighting three main components. Inhibition shows rapid improvements in early childhood and continues progressively into adolescence, associated with brain maturation and the development of metacognition. Working memory improves linearly from preschool through adolescence, supported by progressive and regressive changes in the frontoparietal circuit, especially in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Cognitive flexibility shows a prolonged developmental trajectory, progressing from simple shifts in preschool age to more complex shifts in adolescence, reaching adult-like levels by mid-adolescence.

According to the findings of this meta-analysis, we can assert that the BRIEF enables the assessment of the executive function profile in children and adolescents with NF1, as it provides data on specific areas such as cognitive flexibility, planning, inhibitory control, and working memory. The results obtained in early life can be corroborated through longitudinal studies conducted in adulthood using the BRIEF-A [

50]. Evidence suggests that executive function deficits in NF1 persist throughout life, being moderate in working memory and planning/problem-solving, and somewhat smaller in inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility [

74].

This pattern underscores the need for continuous interventions adapted to each stage of development, aimed at strengthening executive skills and supporting academic and daily adaptation in individuals with NF1.

Regarding informants, the results of the meta-analysis show that both parents and teachers consistently perceive moderate difficulties in executive functions in individuals with NF1. This convergence across different contexts strengthens the findings, as it reflects that the deficits are not specific to a single situation or type of relationship with the child, but rather manifest transversally and consistently in daily life.

The fact that effect sizes are moderate in both cases indicates that the difficulties are clinically relevant, with sufficient impact to affect both family dynamics (organization, self-regulation, behavior management) and academic performance (planning, working memory, inhibitory control).

Overall, the results indicate that executive deficits associated with NF1 are a stable and widespread feature, consistently present in various settings, such as school and home. This pattern highlights the importance of coordinated efforts between home and school, aimed at strengthening the development of executive functions across different contexts. Research emphasizes that the development of executive functions depends on multiple environmental contexts throughout life, ranging from family stimulation in early childhood to the quality of the school environment in adolescence, with each exerting a different impact. For instance, Obradović et al. [

94] show that cognitive stimulation at home and maternal scaffolding are fundamental for the early development of EF, even in disadvantaged contexts, and that maternal cognitive abilities modulate these effects.

Discrepancies between self-reports and informants on the BRIEF can be explained by multiple reasons and have been the subject of various studies [

27,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

94,

95,

96]. First, children may have limited awareness of their own executive difficulties, leading to underestimation in self-reports, while parents or teachers—by observing them in different contexts—perceive these difficulties more clearly. In addition, third-party reports reflect behavior in structured environments, such as school or home, where executive demands are more evident, whereas self-reports reflect the child’s subjective experience in situations where they may feel more competent. Emotional and motivational factors, such as social desirability, may also bias self-reports, while third parties may be influenced by expectations or comparisons with other children. Finally, since executive functions involve internal processes that are difficult to observe directly, third parties may detect deficits that the child does not perceive.

Taken together, these differences underscore the importance of combining both types of reports to obtain a more complete and accurate profile of executive functioning.

From a methodological perspective, the number of studies included in this meta-analysis was relatively small, particularly for the clinical scales Self-Monitoring and Organization of Materials and for the Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI).

Only two studies were included - Gilboa et al. [

67] regarding the Organization of Materials clinical scale, and Payne et al. [

22]- which included the Self-Monitoring and Organization of Materials clinical scales as well as the Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI). Therefore, the effect of these clinical scales and index needs to be further explored in future research with a greater number of studies, as there is a gap in these dimensions within the present meta-analysis.

The analysis revealed heterogeneity in the findings, without identifying any relevant moderating effects. Since this cannot be attributed to a single variable, these conclusions should be applied with caution, not assumed to be universal, and should continue to be refined through further investigation.

Limitations

This review process has several limitations.

First, the literature search was restricted to publications in English and Spanish, which may have excluded relevant studies published in other languages. Second, some included studies lacked detailed reporting of their methods or outcomes, limiting the ability to assess risk of bias. Additionally, due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity among the studies (e.g., differences in age groups, diagnostic criteria, and outcome measures), broad inclusion criteria were necessary, which may have affected the consistency of the syntheses. Lastly, access to individual participant data was not available, so certain analyses relied solely on the information reported by study authors.

The presence of neurodevelopmental disorders in samples of individuals with NF1 may have influenced the obtained results [

19,

97,

98]. Chisholm et al. [

99] , in their systematic review and meta-analysis on social functioning and autism spectrum disorder in children and adults with NF1, highlight that observed social difficulties may be modulated by neuropsychiatric comorbidities, including ADHD and ASD. Although not all studies included in our review specify whether participants with NF1 had diagnoses of these neurodevelopmental disorders, this limitation has been considered in the present version of the study. Therefore, future research should explicitly control for these comorbidities in order to clarify the specificity of findings related to executive functioning associated with NF1.

A notable limitation of the present meta-analyses is the restricted availability of data across the included studies. Only six published studies provided usable data, and complete data were not accessible for all scales and indices in every study. This limitation constrains the generalizability of the findings and has been explicitly acknowledged in the revised version of this work.

Additionally, some meta-analyses were conducted with as few as two studies per specific subscale. While this approach was guided by the clinical and theoretical relevance of the constructs and the methodological consistency among studies, the limited number of studies inherently reduces statistical power and may increase the risk of heterogeneity. Despite these constraints, the available data offered a valuable opportunity to examine preliminary trends, which can inform hypotheses and design for future research.

Given these limitations, the conclusions should be interpreted with caution, and further studies with broader data access are needed to strengthen the robustness and reliability of the findings. One limitation of the current review and meta-analysis is that the relationship between executive function and its impact on quality of life has not been assessed. A previous meta-analysis highlighted the importance of considering this association [

46].

Future Perspectives

For future research, we plan to: (i) Develop a review of neurophysiological studies on executive functions in order to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of executive functioning. (ii) Compare executive function profiles in NF1, ADHD, and ASD to identify both shared vulnerabilities and distinct traits. (iii) Analyze variables related to quality of life alongside executive function assessments to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how executive performance translates into real-world outcomes. (iv) Incorporate the assessment of executive functions into phenotypic characterization to enable more accurate diagnoses and the design of tailored, personalized interventions.