1. Introduction

Numerous pollutants are released into the atmosphere, water bodies, and soil everyday as a result of uncontrolled human activities. Among these pollutants, nitrophenols (NPs) and its various derivatives constitute an important environmental problem because they are highly toxic for humans and many other animal and plant species. Consequently, soils and water of seas, lakes, streams and underground currents contaminated by these compounds have negative effects on all ecosystems directly or indirectly related to them [

1]; they are substances phytotoxic to the planet [

2].

They have a high stability and solubility in water, so they can reduce the concentration of dissolved oxygen in natural waters, affecting aquatic ecosystems [

3]. Moreover, they are not biodegradable and have a high presence as a result of their use by various industries (drugs, dyes, explosives, plasticizers, pesticides, artificial colors and petrochemicals), as well as because they are produced by the degradation of fungicides and insecticides used in agriculture, such as parathion and nitrofen [

2,

3,

4], by the burning of biomass and by traffic emissions, among others daily activities [

5]. Due to their relative volatility, NPs are distributed in gaseous form and are present in urban, suburban, rural, coastal and mountainous areas. Furthermore, they can be formed in the atmosphere by oxidation of phenol in the presence of OH and NO₂ radicals during the day or at night in the presence of NO₂ and NO₃ [

5]. A study carried out in 2012 by the University of Chile revealed that, for the period between august and October, 4-nitrophenol was present in 72.7% of the cases when dew droplets were analysed. Currently, there are no similar studies, but this percentage is expected to have increased because its production has been continuous and, as previously indicated, this compound is not biodegradable [

6].

As a consequence of their biotoxicity, these noxious pollutants cause damage to different organs in animals and humans. In the latter case, NPs can cause mutagenic effects and cancer [

7,

8]; even at very low concentrations [

1], are potential teratogens and mutagens [

4], and can affect the central nervous system, blood cells and organs such as the kidney and liver [

2]. Symptoms of acute intake include nausea, cyanosis, dizziness, skin irritation, methemoglobinemia, drowsiness, and severe headaches [

4]. In particular, 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) has been classified by the USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) as high-priority hazardous pollutant being prohibited its use [

9]. It is associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis in different tissues [

10] and cancer [

11].

Some techniques have been proposed to recognize and remove NPs from contaminated water, air or soil. These include detection using an electrochemical sensor [

12]; selective separation and enrichment of nitrophenols with a printed monolith [

13]; formation of an inclusion complex with bis-8-hydroxyquinolinium zinc-2,6-pyridinedicarboxylate [

14]; and a spray tower plasma-reactor in a spatial post-discharge configuration for remote pollutant treatment [

15], among others. Macrocycles have also been used for this purpose. For example, phthalocyanines [

16,

17], tetrapyrrolic macrocycles [

18] and cobalt-porphyrin complexes have been tested [

19], among others.

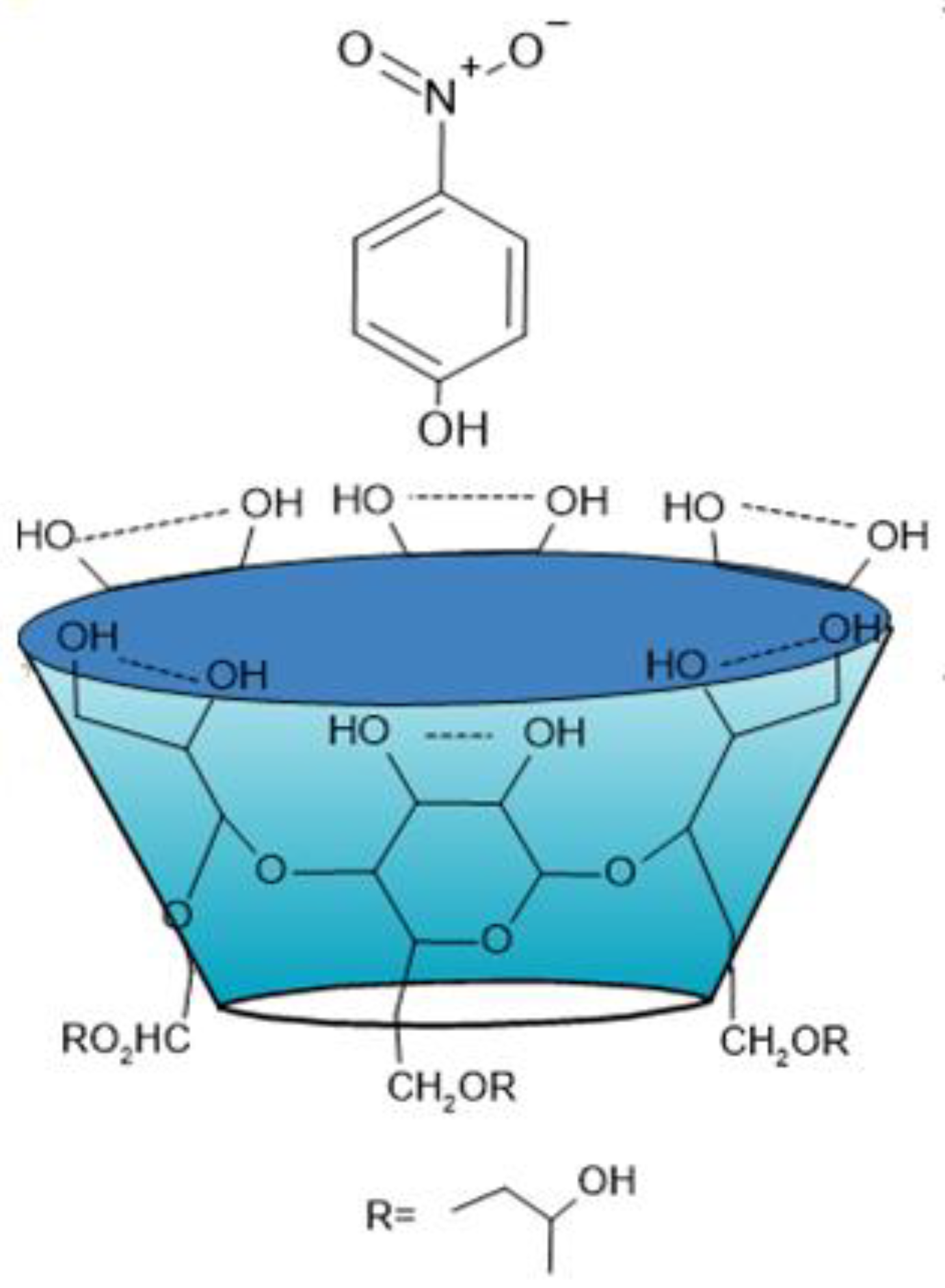

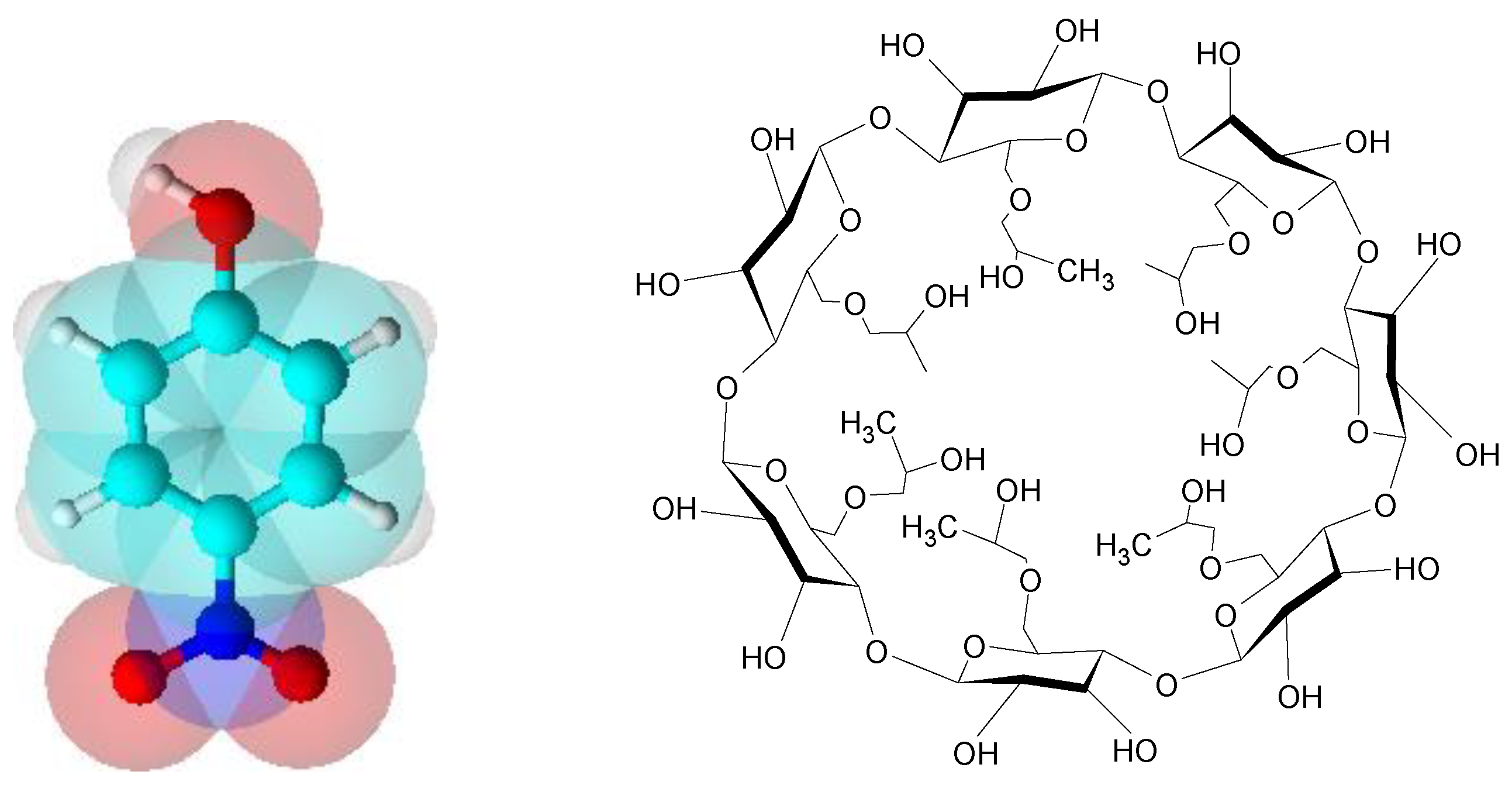

Continuing this line, this research shows the findings made in the recognition of (4-NP) (

Figure 1a) with 2-hydroxypropyl-

β-cyclodextrin (2-HP-

β-CD) at 298.15 K. This cyclodextrin has the advantage of being water-soluble [

20], having low toxicity, not being hygroscopic, chemically stable and easily separable. All these properties favor its use in the chemical, pharmaceutical [

21], food, agricultural and environmental industries [

22,

23].

(2-HP-

β-CD) is a cyclic oligosaccharide containing seven D-glucopyranose units linked by (1,4)-glycosidic bonds. It has a hydrophobic inner cavity where water-insoluble molecules can be accommodated. The exterior of this macrocycle is hydrophilic (

Figure 1b). This structure facilitates the formation of inclusion complexes with different hydrophobic guests which, thus, enhance their solubility [

24].

The objective of this work is to find an alternative and effective method to complex 4-NP in water, in order to isolate and inactivate it. For this purpose, the host-guest-type complex {(2-HP-β-CD)/(4-NP)} was obtained and its structural characteristics evaluated by using NMR, FT-IR, masses and UV-Vis spectroscopies. In addition, apparent molar volumes and isentropic compressibilities of this complex were determined in aqueous solutions, at different concentrations of both components, and analyzed with respect to the values corresponding to the isolated components, (4-NP) and (2-HP-β-CD). All the experiments were carried out at 298.15 K.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Spectroscopic Studies

As mentioned above, the interaction between 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) and 2-hydroxypropyl-

β-cyclodextrin (2-HP-

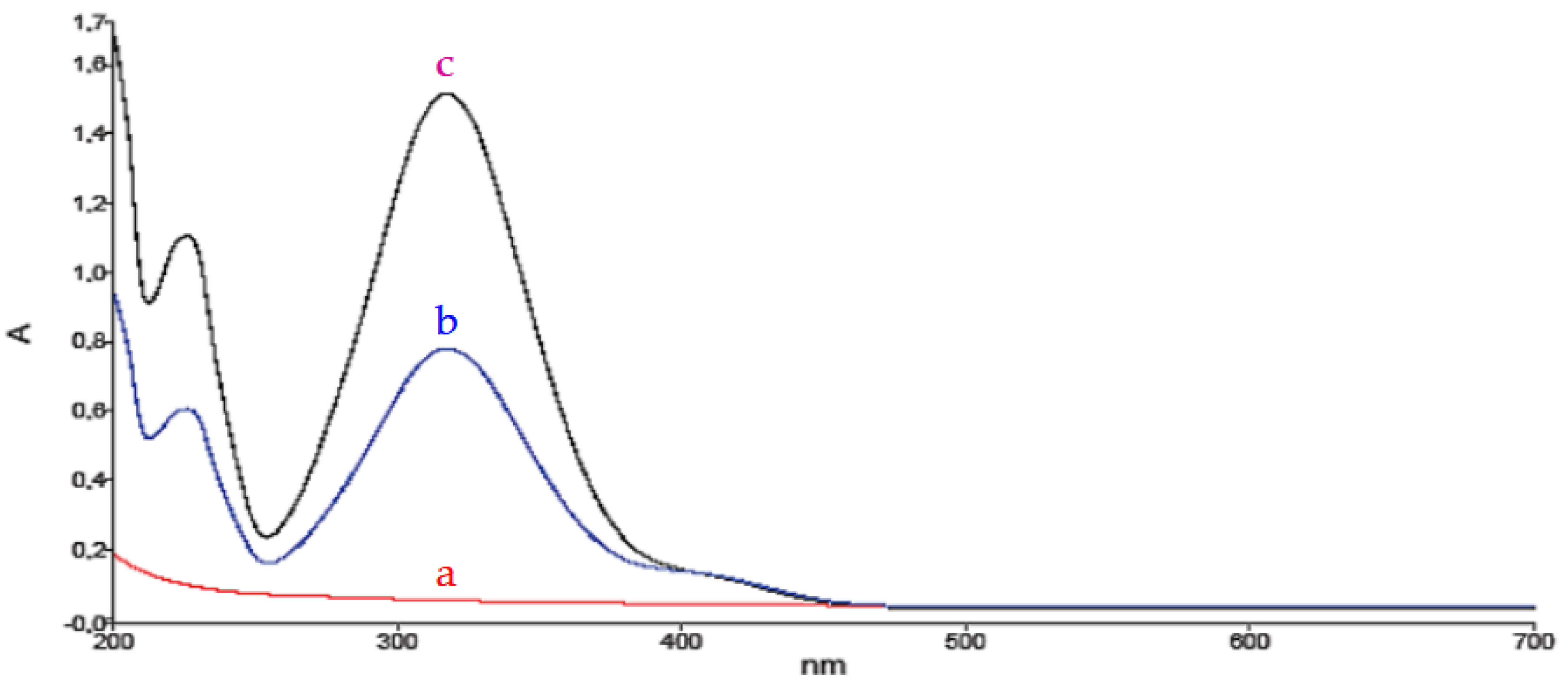

β-CD) in water was investigated by spectroscopic techniques. As a preliminary test, the molecular interaction was studied by UV-Vis spectroscopy. First, the spectrum of 4-NP in aqueous solution was analysed (line b in

Figure 2), which showed a main absorption band at a wavelength at 325 nm and another secondary absorption band at 420 nm. Subsequently, the spectrum of an equimolar mixture of {(4-NP) + (2-HP-

β-CD)} in aqueous solution was analysed (line c in

Figure 2), observing a hyperchromic effect of the 4-nitrophenol band at 420 nm. It is worth nothing that this cyclodextrin does not exhibit absorption in this region of the UV-Visible spectrum (line a in

Figure 2), so the aforementioned hyperchromatic effect must be due to the interaction of (4-NP) with the cyclodextrin. Thus, this behavior, resulting from the mixture of the two components, indicates the existence of a clear interaction between them, possibly by the formation of a host-guest type inclusion complex.

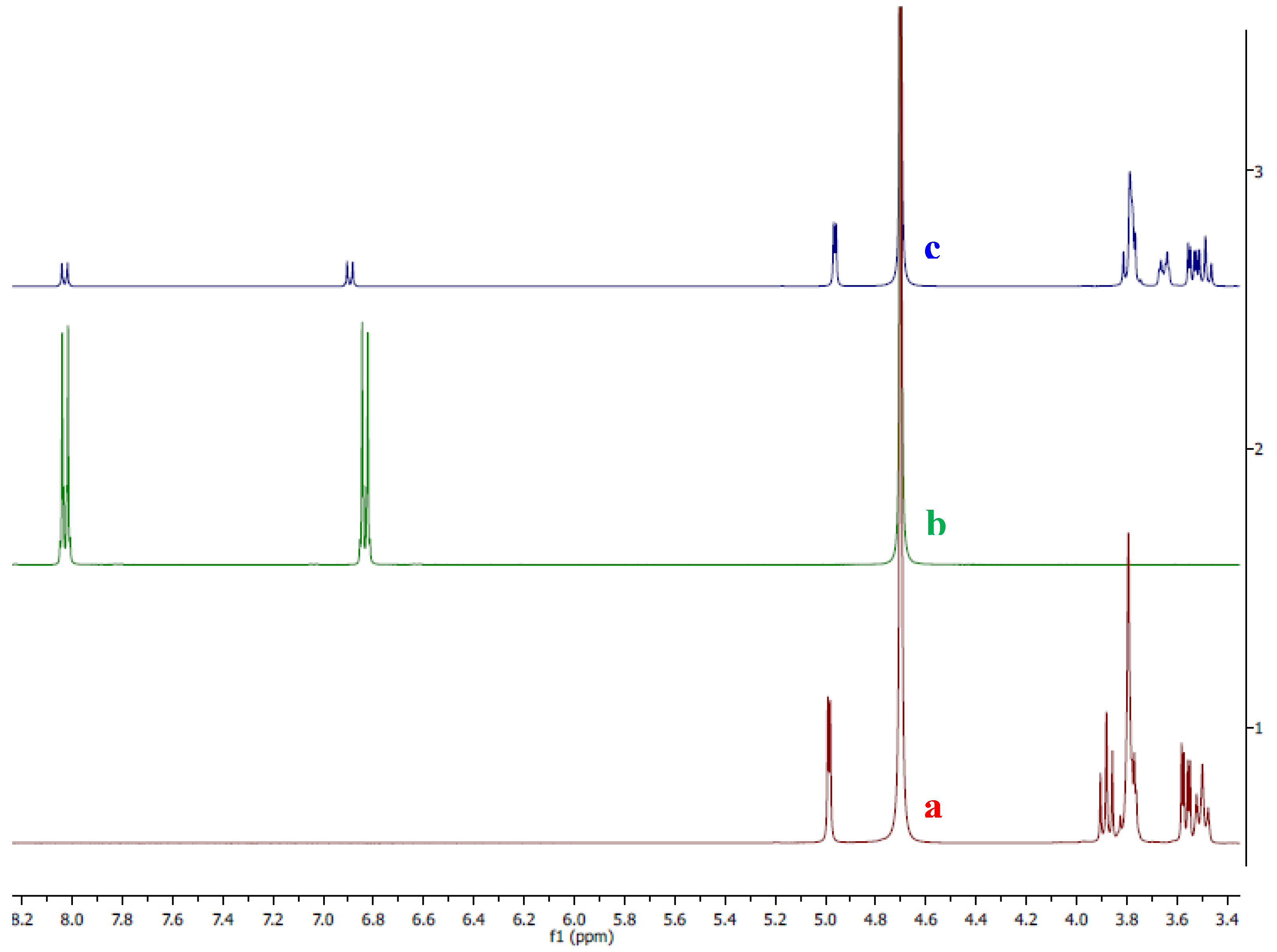

To confirm the interaction between (4-NP) and (2-HP-

β-CD), it was decided to study the system using the NMR technique. For this purpose, individual

1H-NMR spectra of both (4-NP) and (2-HP-

β-CD) were obtained in deuterated water. The

1H-NMR spectrum of (4-NP) in D

2O (green line in

Figure 3) shows two characteristic signals: the first signal, corresponding to the protons in the

ortho position with respect to the nitro group, at 8.03 ppm, and the second signal, corresponding to the protons in the

meta position with respect to the nitro group, at 6.83 ppm. Once the characteristic signals of (4-NP) were established, the spectrum of the equimolar mixture of this with (2-HP-

β-CD) was analyzed (blue line in

Figure 3). This spectrum shows a shift in the signal of the protons from the

meta position with respect to the nitro group, which appears at 6.90 ppm, while the protons in the

ortho position do not show an appreciable shift.

Another interesting aspect is the observed shift in the (2-HP-β-CD) signals (red line), specifically the triplet signal at 3.90 ppm. As it can be seen in the spectrum of the mixture (blue line), this signal undergoes a notable change; first, it shows a shift to 3.83 ppm, and also its multiplicity is significantly affected. These results suggest that the molecular interaction occurs between the OH functional group of (4-NP) and the polar cavity of (2-HP-β-CD), possibly through hydrogen-bonding interactions. It is important to note that when the same experiments were performed on a mixture with a higher stoichiometric ratio between (4-NP) and the CD (1:2 or 2:1), the same results were observed, allowing us to conclude that the host-guest complex is formed and, furthermore, that it has a 1:1 stoichimetry.

2.2. Analysis of Volumetric Properties

2.2.1. Binary Solutions

For binary solutions (solute + solvent), the apparent partial molar volume of the solute was obtained from experimental density data using equation (1):

where

ρ and

ρ0 represent the densities (in g·cm

-3) of the solution and the solvent, respectively,

M2 is the molar mass (in g·mol

-1) of the solute, and

m is its molal concentration (mol·kg

-1). The apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility,

κϕ, was calculated by using the following expression:

where

and

(in Pa

-1) correspond to the isentropic compressibility of the solvent and the solution, respectively, which were calculated from the Newton-Laplace equation:

υ (in m·s

-1) being the speed of sound of the solvent or solution, as appropriate. Solvation numbers at infinitesimal ionic strength were obtained from

and

using the Pasynski equation [

25]:

2.2.1.1. 4-Nitrophenol Aqueous Solutions

The values for

Vϕ,

βs,

κϕ and

nh for aqueous solutions of (4-NP) at 298.15 K are shown in

Table 1. The uncertainties in

Vϕ,

βs,

κϕ and

nh were calculated in accordance with the propagation uncertainty law.

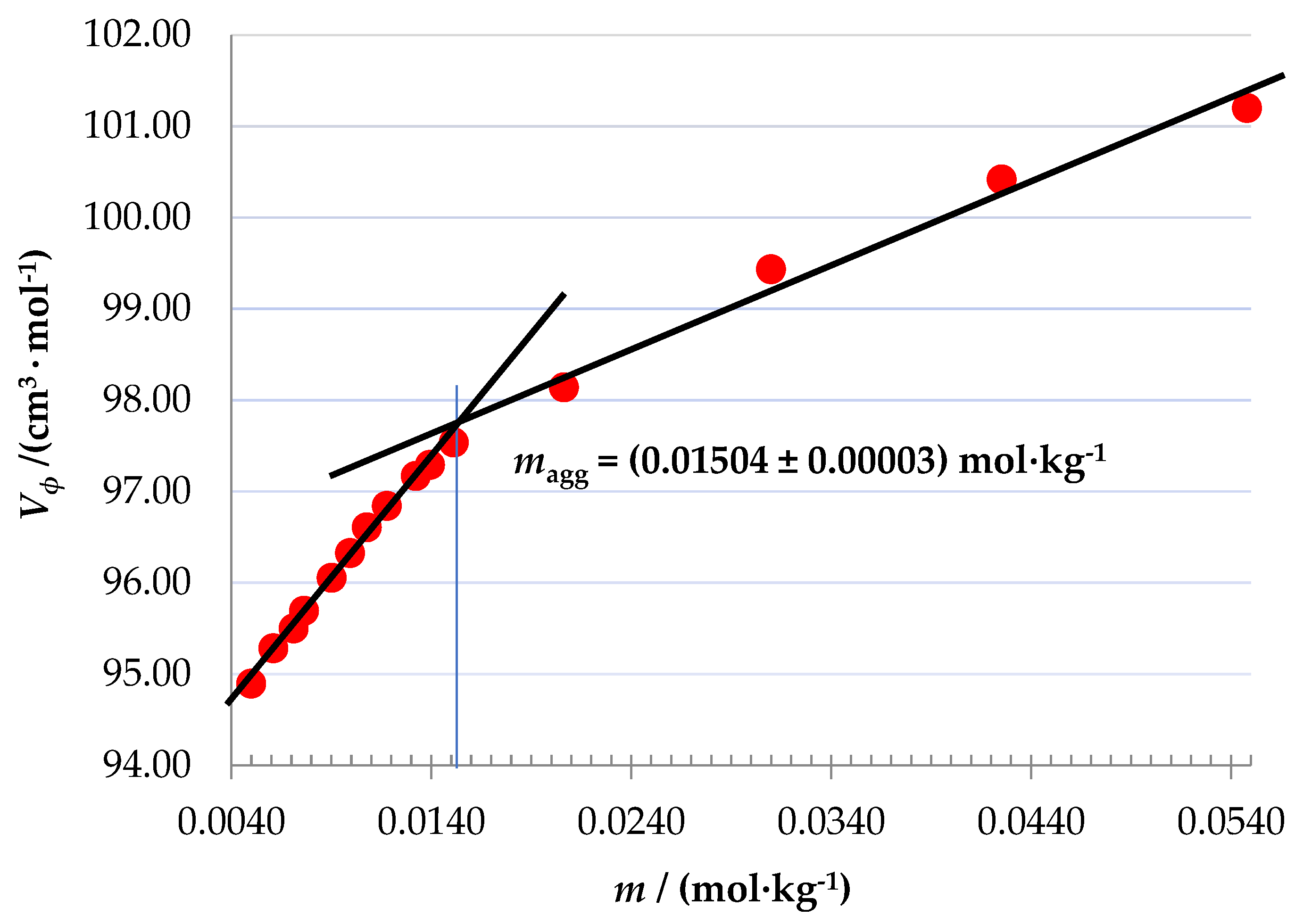

In

Figure 4 the values of

Vϕ for (4-NP) are plotted against its molal concentration. As it can be seen, two regions with quite different slopes are observed. This type of change in slope has been associated, in the case of hydrophobic solutes, with the formation of micellar aggregates [

26]. In our case, this magg concentration may be associated with the formation of some type of aggregates from it. This concentration was determined using the Phillips method, based on the principle of searching for the concentration at which an abrupt change in a concentration-dependent property X occurs (i.e.,

d3X/

dm3 = 0). In this case, the three properties,

X = {

Vϕ,

κϕ and

nh}, were used [

27,

28] finding a mean value

magg = 0.01504 ± 0.00003 mol∙kg

-1. The plots of

κϕ and

nh vs the molal concentration are shown in

Figures S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials.

The dependence of

Vϕ on

m, in both intervals, was analyzed by linear weighted regression to a Redlich type equation [

29], whose application to non-electrolyte solutions has been shown to be effective:

being

the limiting value at infinite dilution (which can be identified to the standard partial molar volume of the solute,

) and

SV an empirical parameter. The values found are collected in

Table 2.

It can be seen that

SV values are positive in both concentration regions (before and after

magg), which means that the apparent partial molal volume of (4-NP) increases as its concentration in the solution increases. Since

SV is a measure of the solute-solute interactions taking place in the solution, these positive values indicate the presence of strong solute-solute interactions that are highest before the

magg concentration is reached; this would justify the stabilization of complex solute-solute aggregation structures, with the resulting destructive overlap between their hydration spheres [

30], leading to a decrease in the solvent structure around the solute molecules involved and, consequently producing a positive volume change.

On the other hand, in

Table 1 it can be seen that the isentropic compressibility of the solution,

βs, slighly decreases with the 4-NP concentration; i.e., that the compaction, under isentropic conditions, of the hydration spheres of the solute molecules becomes more difficult as the solute concentration increases and, therefore, the relative change in volume of the solution becomes more difficult.

In addition, in

Table 1 and

Figure S1, in the Supplementary Materials, it can be ascertain that the apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility,

κϕ, decreases strongly with the concentration of (4-NP), even reaching negative values, in the pre-aggregation region (

m <

magg). This behaviour, together with what was observed for the apparent partial molal volume and for the isentropic compressibility, leads to the conclusion that in this area of low 4-NP concentrations the solute-solute interaction is strong enough for aggregation structures (4-NP/4-NP) to appear, with the consequent destructive overlapping of the hydration shells, which leads to a loss of compressibility of the hydration spheres and, consequently, that the compaction capacity of the solution when pressure is applied is diminished. In the post-aggregation region (

m >

magg), the increase in the concentration of 4-NP leads to the structure-breaking effect of this solute on water structure, to build the corresponding hydration shell, managing to balance this effect, justifying the increasing of the apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility observed when the 4-NP concentration increases [

30].

The analysis of the variation of the apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility with the concentration, to obtain the standard value,

, was carried out by fitting, using weighted least squares linear regression, the experimental values of

to the following equation:

where

is the limiting value at infinite dilution (which can be identified to the standard molar adiabatic compressibility,

) and

SK is the empirical slope. The values found are collected in

Table 2.

With respect to solvation numbers, these increase with the concentration of 4-NP in the pre-aggregation region (

m <

magg) while they decrease in the post-aggregation region (

m >

magg) (

Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials). The dependence of the hydration numbers on the 4-NP concentration was analyzed through the linear equation:

where

is the hydration number at infinite dilution and

bn is an experimental parameter. The values obtained are also shown in

Table 2.

2.2.1.2. 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Aqueous Solutions

The values for

Vϕ,

βs,

κϕ and

nh for aqueous solutions of (2-HP-

β-CD) at 298.15 K are shown in

Table 3. The uncertainties in

Vϕ,

βs,

κϕ and

nh were calculated according to the propagation uncertainty law.

It is worth highlighting the high values obtained for the apparent partial molar volumes of this cyclodextrin, which is consistent with what would be expected given that it is an organic compound with a high molar mass [

31]. Furthermore, this apparent partial molar volume increases significantly with increasing solution concentration. Such increase in molal volume with increasing solute concentration in the solution has been associated with the existence of hydrophobic hydration of the solute [

32,

33] and in the case of apolar solutes (such as CDs), also to the existence of a strong solute-solute interactions which would favor the formation of dimeric structures of this cyclodextrin [

34,

35].

The dependence of

Vϕ on

m was studied using the Redlich linear model:

being the standard molar volume of (2-HP-

β-CD) and

is the slope.

This concentration dependence of

Vϕ on

m is shown in

Figure S3 of the Supplementary Materials. As can be seen, a linear behavior is perfectly defined (R

2 = 0.9995). The values found are also collected in

Table 2. Looking at these values in

Table 2, it can be seen that the one found for

SV is much higher than that of

. If we take into account that

corresponds to the limiting value at infinitesimal concentration, where practically only the solute-solvent interactions are felt, while

SV gives a measure of the solute-solute interactions, it can be inferred that for this solution the CD-CD interaction is more intense than the CD-water interaction [

36,

37], reinforcing what was stated before.

Regarding the apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility,

, it is observed that it increases linearly with the concentration of the cyclodextrin in the solution (see

Figure S4 in Supplementary Materials). Consequently, these experimental values were fitted to the linear equation (6) using a least squares regression, yielding a good correlation value (R

2 = 0.99). The values obtained for this fit are also shown in

Table 2.

As it can be seen, the limiting value

is negative. Considering that the molar compressibility is related to the structural changes that occur in the solvent as a result of the presence of the solute, negative values of

are associated with a higher resistance of the solution against compression, compared to the pure solvent [

33]. This increase in the adiabatic compressibility with increasing concentration can be justified by taking into account that (2-HP-

β-CD) has hydroxypropyl groups on the outside of its molecule that enhance its hydrophilic character (being easy points of union with the surrounding water molecules) thus increasing its solubility in water; consequently, this cyclodextrin has a breaking effect on the structure of water.

The analysis of the dependence of the hydration number on the cyclodextrin concentration was performed using the linear equation (7). The values found are also shown in

Table 2, and their behavior is shown in

Figure S5 in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2.2. Ternary Aqueous Solutions

The ternary systems in solution (two solutes + solvent) were analyzed considering them as pseudo-binary systems; that is, as one solute (4-NP) dissolved in a mixed solvent (2HP-β-CD + water). However, the molalities of both solutes, 4-NP and 2-HP-β-CD, in the ternary solution are referred to the total amount of water present in said solution.

The apparent partial molar volumes, Vϕ,mix, were determined by using equation (1). In this case, ρ and ρ0 denote the density values (in g·cm-3) of the ternary solution (4-NP + 2HP-β-CD + water) and of the mixed solvent (2HP-β-CD + water) at the corresponding cyclodextrin concentration, respectively. The other variables, M2 and m, are the molar mass (in g·mol-1) and the molal concentration (in mol·kg-1) of the 4-NP solution in the mixed solvent (2HP-β-CD + water).

In the same way, the apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility values of the ternary solution, κϕ,mix , were calculated by means of the equation (2), being and (in Pa-1) the isentropic compressibility of the ternary solution (4-NP + 2HP-β-CD + water) and the mixed solvent (2HP-β-CD + water), respectively, calculated from equation (3). The rest of the variables have their usual meaning.

Finally, solvation numbers of 4-NP in these mixed solvent (2HP-β-CD + water) were determined from equation (4), and analysed as a function of the concentration.

The values found for

Vϕ,mix,

βs,mix,

κϕ,mix and

nh for the {(4-NP)+(2-HP-

β-CD)} aqueous system are shown in

Table 4. The corresponding uncertainties were obtained from the propagation uncertainty law.

Looking at

Table 4 it can be seen that the value of

Vϕ,mix increases with the increase in the concentration of 4-NP, said increase being linear in the concentration range analyzed (

Figure S6 in Supplementary Materials). This behaviour was analyzed by using the Redlich linear model (equation 8). The values found are given in

Table 2.

As it can be seen, the Sv value is positive, indicating that the solute-solute interaction becomes increasingly stronger as the concentrations of the 4-NP and 2-HP-β-CD are higher as well. On the other hand, it can also be seen that these Sv values are quite high, although somewhat lower than the value presented by the pure cyclodextrin, which indicates that in these media the interactions between the solutes is more intense than with water.

On the other hand, the apparent partial molal adiabatic compressibility,

, also increases linearly with the concentration of 4-NP in the solution (see

Figure S7 in the Supplementary Materials). This increase indicates that the solution becomes more compressible as the concentration of 4-NP increases, and its apparent molal volume also increases, indicating a breaking character on the water structure by 4-NP. Finally, the fact that the solvation numbers decrease with concentration

(bn < 0) (see

Figure S8 in the Supplementary Materials) reinforces the idea that there is a structure-breaking effect on water, possibly favored by the destructive overlap between the solvation spheres of the solutes present [

38].

2.2.2.1. Partial Molar Volumes of Transfer

Partial molar volumes of transfer, Δ

Vϕ, for 4-NP from water to the different (2-HP-

β-CD + water) mixed solvents were calculated from the equation:

where the volume values are those collected in

Table 4 and

Table 1, respectively. The values found are shown in

Table 5.

It is observed that these transfer volumes are always positive and increase linearly with the concentration of the solutes (4-NP and 2-HP-

β-CD) (see

Figure S9 in the Supplementary Materials). This behavior can be explained by using the Friedman and Krishnan model [

38] of overlap of solute hydration spheres. According to this model, the superposition of the hydration spheres causes a decrease in the number of water molecules surrounding the solutes, which leads to their partial dehydration and, consequently, an increase in their apparent partial molar volume. This effect is greater as the concentration of both solutes increases. Positive values of the transfer volume indicate a predominance of hydrophilic interactions (between the -OH groups of the CD surface and the -OH and -NO₂ groups of 4-NP) over hydrophobic interactions (between the nonpolar -CH₂- groups of the CD and the 4-NP ring), which intensify as the concentration of 4-NP in the solution increases [

34].

In the infinite dilution situation, the limiting value found, , is also positive (= 10.99 cm3 mol-1). Remembering that at infinitesimal concentration the interactions between the solute molecules are practically non-existent, the observed transfer volume is the result of the interactions between the solute and the solvent molecules. The fact that this transfer volume has a positive value means that the hydrogen bond interactions between the hydrophilic groups of 4-NP and the water dipoles (which contribute to an increase in said volume) are predominant.

2.2.2.2. Interaction Volumes and Intrinsic Volumes

The process of dissolving a solute in a solvent can be considered to occur in two stages: a first in which a cavity of sufficient size is opened in the solvent for the solute molecule to enter, and a second one in which the solute enters this cavity and solute-solvent interactions are established. On this basis, the standard molar volume can be expressed as the sum of several contributions, as shown in the following equation [

39]:

where

Vintr is the intrinsic volume of the solute,

VT is a contribution related to the effects of packaging (corresponding to the empty space surrounding the solute molecule, caused by the thermal motion of solute and solvent molecules),

Vinter is the interaction volume related to the solute-solvent interactions, while in the last term

κT0 is the isothermal compressibility of the solvent,

R is the universal gas constant and

T is the temperature in Kelvin. This last term is related to the volume effects of molecular motions [

39] and since its contribution is small compared to the other terms, it can usually be ignored [

40]. Since the terms

VT +

Vinter both depend on the solute-solvent interactions, it is possible to group them into a single term

VI. Finally,

Vintr of solute can be identified with the Van der Waals volume

VW. According to the above, equation (10) can be reduced to:

If this equation is applied to the systems (4-NP + water) and (2-HP-

β-CD + water), since the

values are known and

VW values can be estimated theoretically, it is possible to calculate the

VI values. For this purpose, the

VW values for (4-NP) and (2-HP-

β-CD) were calculated using Winmostar, after geometry optimization by MOPAC using a semi-empirical method. In the case of the complexes formed, the data obtained by H

1 NMR allow to know which protons are being affected and how the guest enters the host cavity. In this way, the architecture of the complex can be proposed, and the host-guest interactions analyzed.

Table 6 shows the values of

,

VW and

VI for (4-NP+water) and (2-HP-

β-CD+water) systems:

For 4-NP in water the interactions that can be expected are due to the hydrogen bond between its hydroxyl group and the water molecules. The nitro group is a weak hydrogen bond acceptor because the N-O bond is non polar enough. However, these interactions are sufficient to make this molecule moderately soluble in water, which contributes to its problematic nature [

41]. Meanwhile, for 2-HP-

β-cyclodextrin in water, it is possible to think about the formation of hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl groups on the outside of the cyclodextrin, which is hydrophilic, not with its inside because its cavity is hydrophobic. Water can form hydrogen bonds with the cyclodextrin either through the upper rim of the cone, with the secondary hydroxyl groups, or through the lower rim of the cone, with the primary hydroxyl groups of the cyclodextrin. The interactions that can be expected for the complex in water when the 4-NP is placed inside the hydrophobic cavity of the cyclodextrin can be due to hydrophobic interactions between the aromatic ring of the phenol and the hydrophobic inside of the cyclodextrin (H-C, C-C and glycosidic bonds) and Van Der Waals interactions. Both at the bottom and top of the cyclodextrin, interactions with the hydroxyl group of the phenol can be expected (depending on how it enters, see NMR). While outside the complex there may be hydrogen bonding interactions between the hydroxyl groups of the cyclodextrins and water, this is what increases the solubility of (4-NP) complexed with the cyclodextrin compared to the solubility of (4-NP) when it is alone in water. Some of these interactions were confirmed by

1H-NMR, which revealed that strong interactions occurs between the OH functional group of (4-NP) and the polar cavity of (2-HP-

β-CD), possibly through hydrogen-bonding interactions.

Figure 5 schematizes the complex formed.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

2-hydroxypropyl-

β-cyclodextrin (2-HP-

β-CD; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany; average molar mass M ≈ 1380 g mol

-1, mass fraction purity ≥ 0.98, water content of 10.3% mass fraction, by Karl-Fisher analysis reported by the supplier) and 4-nitrophenol (4-NP; Panreac Química S.L.U., Castellar del Vallès, Spain; molar mass M = 139.11 g mol

-1, purity 99%) were used as received. These chemicals were stored in a desiccator over silica gel. Milli Q

® grade water (from EQ 7000 Ultrapure Water Purification System-Merck Millipore, Darmsdadt, Germany; κ = 5.6 × 10

−8 S cm

−1) was used as solvent; it was degassed before use (

Table 7). Solutions were prepared by direct weighing of their components by using a Sartorius analytical balance (Sartorius AG, Gottingen, Germany) with an accuracy of 1 × 10

−5 g in the range of interest. Both the purity and the water content of the chemicals used were taken into consideration to calculate the molal concentration of the solutions. The solution was degassed before the experiment was run.

3.2. UV-Visible Analysis

UV-Visible analyses were carried out on a Lambda 365 Perkin-Elmer spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). Detection was performed in the range of 200-800 nm. UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured in water. Stock solutions, 1 mM of (2-HP-β-CD) and 10 mM of (4-NP), were prepared in H2O.

3.3. 1H-NMR Analysis

1H-NMR spectra were recorded in D2O at 400 MHz using a Bruker Avance 400 instrument (Bruker Scientific Instruments, Billerica, MA, USA). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm, using the residual solvent signal (D2O) as a reference. A total of seven samples of mixtures of (4-NP) and (2-HP-β-CD) were prepared using a fixed amount of (2-HP-β-CD), (20 mg in 600 μL), and a solution of (4-NP) (0.3 M) until a 1:1 molar ratio was reached. The total volume of solution prepared was, in all cases, 700 μL. After each addition, the 1H-NMR spectrum was recorded. The concentrations of the guest and host in the solution were corrected for each addition.

3.4. Density and Speed of Sound Measurements

Densities and speed of sound were measured with an Anton Paar DMA 5000 densimeter (Anton Paar Spain S.L.U., Madrid, Spain). The functioning of this instrument is based on the vibration, at a frequency of 3 MHz, of a U-tube containing the solution under study. The sensitivity of this equipment is 1 × 10–6 g∙cm–3, with a reproducibility of ±5 × 10–6 g∙cm–3, for density measurements, and 1 × 10–2 m∙s–1, with a reproducibility of ±3 × 10–2 m∙s–1, for measurements of the speed of sound through the working solution. This densitometer is equipped with a Peltier temperature control system that allows a stability better than ±0.005 degrees, over a temperature range of (0 to 90) °C and pressure range of (0-1.0) MPa. The instrument was verified, at the beginning and the end of each measurement session, using dry air and degassed ultrapure water (Milli-Q quality) at 293.15 K, according to the recommendations of the supplier.

The reported density data are the average of at least three independent measurements that were reproducible within 1× 10

-3 kg m

-3, with an uncertainty of 0.150 kg m

-3, according to NIST [

42].

4. Conclusions

Based on the analysis of UV-Vis spectra, as well as the results of FT-IR and 1H-NMR spectroscopy, the complexing capacity of (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin with 4-nitrophenol was determined. Specifically, the results observed by 1H-NMR suggested that the hydroxyl group of 4-nitrophenol could enter the cyclodextrin cavity and possibly be stabilized inside by hydrogen bond-type interactions.

On the other hand, based on experimental measurements of density and speed of sound, values of the apparent partial molar volume, Vϕ, and the apparent partial molar adiabatic compressibility, κϕ, were obtained for aqueous solutions of (4-NP), (2-HP-β-CD) and of the complex {(4-NP) + (2-HP-β-CD)} and their behavior analyzed as a function of the concentration, at 298.15 K.

Furthermore, partial molar volumes of transfer, ΔVϕ, for 4-NP from water to the different (2-HP-β-CD + water) mixed solvents were calculated, along with the value corresponding to the infinite dilution condition. The positive value found for this limiting transfer parameter confirms that hydrogen bonding interactions between the hydrophilic groups of 4-NP and the water dipoles are predominant.

Finally, from the standard molar volume values found, both the interaction and the intrinsic volumes were estimated and interpreted in terms of the different hydrogen bonds that can be established between the hydroxyl group of 4-NP, the hydroxyl groups of the cyclodextrin and the water molecules.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and M.A.E; methodology, ESE, DMG and MM; software, ESE and MAE; validation, MAE and CMR.; formal analysis, M.M., CMR and M.A.E. ; investigation, MAE, ESE, MM, CMR and DMG; resources, M.M.; data curation, MM, ESE and DMG; writing—original draft preparation, MM, ESE and DMG; writing—review and editing, M.M., CMR and M.A.E.; supervision, M.M. and M.A.E.; project administration, MAE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data obtained is presented in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Bogotá and the Catholic University of Ávila, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruzgar, A.; Karatas, Y.; Gülcan, M. Synthesis and characterization of Pd nanoparticles supported over hydroxyapatite nanospheres for potential application as a promising catalyst for nitrophenol reduction. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rika, Y.; Cantik, C. D.; Devi, A.; Achmad, B.; Aminah, U.; Adid, D.; Jeong-Myeong, H. Comparison study of the effects of different synthesis methods towards Ag2O/TiO2 nanowires morphology and catalytic activity on the 4-nitrophenol reduction reaction. Nano-structures & nano-objects 2023, 36, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Tyagi, I.; Karri, R.R.; Gaur, R.; Javadian, H.; Verma, M. Photocatalytic degradation of noxious p-nitrophenol using hydrothermally synthesized stannous and zinc oxide catalysts, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 2024, 133, 10351. [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Singh, A.; Mahadeva, R.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Gupta, V.; Arya, S. A reduced graphene oxide-based electrochemical sensing and eco-friendly 4-nitrophenol degradation. Diamond & related materials 2024, 141, 110554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hu, X.; Sun, W.; Peng, X.; Fu, Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, F.; Meng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Peng, P.; Bi, X. Mixing state and influence factors controlling diurnal variation of particulate nitrophenol compounds at a suburban area in northern China, Environmental pollution 2024, 123368. [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Zeng, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, J.; Yao, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, J.; Li, K.; He, Q. An efficient electrochemical sensor based on multi-walled carbon nanotubes functionalized with polyethylenimine for simultaneous determination of o-nitrophenol and p-nitrophenol. Microchemical Journal 2023, 186, 108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, K.K.; Rabha, B.; Pati, S. , Choudhury, B.K.; Sarkar, T.; Godoi, S.K.; Kakati, N.; Baishya, D.; Kari, Z.A.; Edinur, H.A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using diospyros malabarica fruit extrac and assessment of their antimicrobial, anticancer and catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP). Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.A.E.; Antony, R.; Jebakumar, D.S.I. Synergistic effect of silver nanoparticle-embedded calcite-rich biochar derived from Tamarindus indica bark on 4-nitrophenol reduction. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karri, R.R.; Ravindran, G.; Dehghani, M.H. Wastewater—Sources, Toxicity, and Their Consequences to Human Health. Soft Computing Techniques in Solid Waste and Wastewater Management 1 (2021) 3-33. [CrossRef]

- Yarmohammadi, F.; Karimi; G. 4-Nitrophenol. Encyclopedia of toxicology (fourth edition) 2024, 6, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giribabu, K.; Haldorai, Y.; Rethinasabapathy, M. ; Jang, S-Ch.; Ranganathan Suresh, R.; Cho, W-S.; Han, Y-K.; Roh, Ch.; Huh, Y.S.; Narayanan, V. Glassy carbon electrode modified with poly(methyl orange) as an electrochemical platform for the determination of 4-nitrophenol at nanomolar levels. Current Applied Physics 2017, 17 (8), 1114-1119. [CrossRef]

- Hryniewicz, B.; Orth, E.; Vidotti, M. Enzymeless PEDOT-based electrochemical sensor for the detection of nitrophenols and organophosphates. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 257, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, X. Preparation of an imprinted monolith for field simultaneously selective separation and enrichment of nitrophenols and lead (II) ion in water samples. Separation and Purification Technology 2024, 337, 126109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Shankar, K.; Baruah, J. Study on the interactions of nitrophenols with bis-8-hydroxyquinolinium zinc-2,6-pyridinedicarboxylate. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2019, 489, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhat, M.F.; Ghezzar, M.R.; Smail, B.; Guyon, C.; Ognier, S.; Addou, A. Conception of a novel spray tower plasma-reactor in a spatial post-discharge configuration: Pollutans remote treatment. J. Hazardous Materials 2017, 321, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugba, E.; Tekintas, K.; Bekircan, O.; Biyiklioglu, Z. Enhancing the photocatalytic performance of Co(II) and Cu (II) phthalocyanine by containing 1,3,4 thiadiazole groups in 4-nitrophenol oxidation reaction. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2023, 547, 121342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjan, V.; Aralekallu, S.; Nemakal, M.; Palanna, M.; Keshavananda, P.; Koodlur, L. Nanomolar detection of 4-nitrophenol using Schiff-base phthalocyanine. Microchemical Journal 2021, 164, 105980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, P.; Donzello, M. P.; Ercolani, C.; Monacelli, F.; Moretii, G. Tetrakis-2,3-[5,6-di-(2-pyridyl)-pyrazino] porphyrazine, and its Cu(II) complex as sensitizers in the TiO2-based photo -degradation of 4-nitrophenol. J. Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2011; 220, 77-83. [CrossRef]

- Guergueb, M.; Nasri, S.; Brahmi, J.; Al-Ghemdi, Y.; Loiseau, F.; Molton, F.; Roisnel, T.; Guerineau, V.; Nasri, H. Spectroscopic characterization, X-ray molecular structures and cyclic voltammetry study of two (piperazine) cobalt (II) meso-arylporphyin complexes. Application as a catalyst for the degradation of 4-nitrophenol. Polyhedron 2021, 209, 115468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindres, D.M.; Espitia-Galindo, N.; Valente, A.J.M.; Sofio, S.P.C.; Rodrigo, M.M.; Cabral, A.M.T.D.P.V.; Esteso, M.A.; Zapata-Rivera, J.; Vargas, E.F.; Ribeiro, A.C.F. Interactions of Sodium Salicylate with β-Cyclodextrin and an Anionic Resorcin[4]arene: Mutual Diffusion Coefficients and Computational Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yu, P.; Sun, P.; Kang, Y.; Niu, Y.; She, Y.; Zhao, D. Inclusion complexes of β-cyclodextrin with isomeric ester aroma compounds: Preparation, characterization, mechanism study, and controlled release. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 333, 121977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, F.M.; Lis, M.J.; Firmino, H.B.; Dias da Silva, J.G.; Valle, R.C.S.C.; Valle, J.A.B.; Scacchetti, F.A.P.; Tessaro, A.L. The Role Of β-Cyclodextrin In The Textile Industry—Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, N.; Benjakul, S. Use of beta cyclodextrin to remove cholesterol and increase astaxanthin content in shrimp oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2019, 122, 1900242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Gupta, U.; Kumar, R.; Munagalasetty, S.; Prasad, H.; Nair, R.; Mahajan, S.; Maji, I.; Aalhate, M.; Bhandary, V.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, P. Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes of Palbociclib: Physicochemical characterization, solubility enhancement, in silicio studies, in vitro assessment in MDA-MB-231 cell line. J. Mol. Liquids 2024, 399, 124458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakowski A., J. Glinski. Hydratation munbers of nonelectrolytes from acoustic methods, Chem. Rev. 112 (2012) 2059-2081. [CrossRef]

- Vass, S.; Töröc, T.; Jákli, G.; Berecz, E. Sodium Akyl Sulfate Apparent Molar Volumes in Normal and Heavy Water: Connection with Micellar Structure, J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 6553–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodriguez, M.; Prieto, G.; Carlos, C.; Varela, L. M.; Sarmiento, F.; Mosquera, V. A comparative Study of the Determination of the Critical Micelle Concentration by Conductivity and Dielectric Constant Measurements. Langmuir 1998, 14, 4422–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaroglu, G.; Genc, L. Determination of micelle formation of ketorolac tromethamine in aqueous media by acoustic measurements. Thermochimica Acta 2013, 552, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, O. Molal volumes of solute, IV. J. Phys. Chem. 1940, 44, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.P.; Shaikh, V.R.; Patil, P.D.; Borse, A.U.; Patil, K.J. Volumetric, isentropic compressibility and viscosity coefficient studies of binary solutions involving amides as a solute in aqueous and CCl4 solvent systems at 298.15 K. J. Mol. Liquids 2018, 264, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahagirdar, D.V.; Arbad, B.R.; Walvekar, A.A.; Shankarwar, A.G. Studies in partial molar volumes, partial molar compressibilities and viscosity B-coefficients of caffeine in water at four temperatures. J. Mol. Liquids 2000, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, O.; Ayranci, E. Apparent molar volumes and isentropic compressibilities of benzyltrialkylammonium chlorides in water at (293. 15, 303.15, 313.15, 323.15 and 333.15) K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2009, 41, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.H.; Salamanca, Y.P.; Vargas, E.F. Apparent molal volumes and expansibilities of Tetraalkylammonium Bromide in dilute aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2008, 53, 2770–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C. I.A.V.; Teijeiro, C.; Ribeiro, A. C.F.; Rodrigues, D. F.S.L.; Romero, C. M.; Esteso, M. A. Drug delivery systems: Study of inclusion complex formation for ternary caffeine–β-cyclodextrin–water mixtures from apparent molar volume values at 298.15 K and 310.15 K. J. Mol. Liquids 2016, 223, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Pandit, B.K.; Acharjee, K.; Sinha, B. Volumetric and Viscometric Behavior of Ferrous Sulfate in Aqueous Lactose Solutions at Different Temperatures. Indian J. Advances in Chemical Science 2015, 3, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Desnoyers, J.E. Structural effects in aqueous solutions: a thermodynamic approach. Pure Appl. Chem. 1982, 54, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shahjahan, S. Volumetric, viscometric and refractive index behavior of some α-amino acids in aqueous tetrapropylammonium bromide at different temperatures. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2006, 3, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H. L.; Krishnan, C. V. (1973). Thermodynamics of Ionic Hydration. In: Franks, F. (ed.) Water: A Comprehensive Treatise, Vol. 3. Aqueous Solutions of Simple Electrolytes. Plenum Press, New York. Chp. 1, pp. 1–118. [CrossRef]

- Likhodi, O.; Chalikian, T.V. Partial molar volumes and adiabatic compressibilities of a series of aliphatic amino acids and oligoglycines in D2O, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros, D.C.; Hefter, G.; Vargas, E. F. Thermodynamic evidence for nano-heterogeneity in solutions of the macrocycle C-butylresorcin[4]arene in non-aqueous solvents. J. Chem. Thermodynamics 2018, 125, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badamasi, H.; Naeem, Z.; Antoniolli, G.; Praveen, A.; Ademola, A.; Shina, I.; Duriminiya, N.; Salman, M. A review of recent advances in green abd sustainable technologies for removing 4-nitrophenol from the water and wastewater. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 43, 10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.N.; Kuyatt, C.E. Guidelines for Evaluating and Expressing the Uncertainty of NIST Measurement Results; NIST Technical Note 1297; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1994.

Figure 1.

a) 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) structure; b) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (2-HP-β-CD) structure.

Figure 1.

a) 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) structure; b) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (2-HP-β-CD) structure.

Figure 2.

UV-visible spectra of: a) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (red line

), b) 4-nitrophenol (blue line

) and c) the equimolar mixture of both components (purple line

).

Figure 2.

UV-visible spectra of: a) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (red line

), b) 4-nitrophenol (blue line

) and c) the equimolar mixture of both components (purple line

).

Figure 3.

Comparative 1H-NMR in D2O: a) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (red line), b) 4-nitrophenol (green line) and c) the complex {(4-NP) + (2-HP-β-CD)} (blue line)

Figure 3.

Comparative 1H-NMR in D2O: a) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (red line), b) 4-nitrophenol (green line) and c) the complex {(4-NP) + (2-HP-β-CD)} (blue line)

Figure 4.

Apparent partial molal volume of 4-nitrophenol vs molal concentration in aqueous solution at T = 298.15K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Figure 4.

Apparent partial molal volume of 4-nitrophenol vs molal concentration in aqueous solution at T = 298.15K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Figure 5.

Scheme of the entry of (4-NP) into the cavity of (2-HP-β-CD).

Figure 5.

Scheme of the entry of (4-NP) into the cavity of (2-HP-β-CD).

Table 1.

Values of Vϕ, βs, κϕ and nh of (4-NP) in water at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Table 1.

Values of Vϕ, βs, κϕ and nh of (4-NP) in water at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

m (4-NP)

/(mol·kg-1) |

Vϕ(a)

/(cm3·mol-1) |

βs (b)

/(10-10 Pa-1) |

κϕ

/(10-9 cm3·mol-1·GPa-1) |

|

| 0.0049840 |

95.91 |

4.475 |

25.81 |

2.1 |

|

| 0.0060976 |

96.11 |

4.474 |

15.72 |

3.3 |

|

| 0.0071112 |

96.21 |

4.473 |

8.49 |

4.2 |

|

| 0.0076254 |

96.35 |

4.473 |

4.93 |

4.7 |

|

| 0.0090101 |

96.61 |

4.472 |

1.41 |

5.1 |

|

| 0.0099300 |

96.83 |

4.471 |

0.0798 |

5.3 |

|

| 0.010770 |

97.07 |

4.471 |

-2.27 |

5.6 |

|

| 0.011775 |

97.27 |

4.470 |

-2.87 |

5.7 |

|

| 0.013223 |

97.55 |

4.469 |

-3.69 |

5.8 |

|

| 0.013929 |

97.65 |

4.469 |

-3.87 |

5.8 |

|

| 0.015116 |

97.87 |

4.468 |

-4.58 |

5.9 |

|

| 0.020631 |

98.39 |

4.466 |

-3.73 |

5.8 |

|

| 0.030985 |

99.60 |

4.461 |

-1.54 |

5.6 |

|

| 0.042524 |

100.54 |

4.457 |

0.340 |

5.4 |

|

| 0.054795 |

101.29 |

4.452 |

2.07 |

5.3 |

|

Table 2.

Standard molar volumes, , standard molar adiabatic compressibilities, , and hydration numbers at infinite dilution, , together with the corresponding parameters of equations (5, 6 and 7), for aqueous solutions of (4-NP), (2-HP-β-CD) and the complex {(4-NP) + (2-HP-β-CD)}, at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Table 2.

Standard molar volumes, , standard molar adiabatic compressibilities, , and hydration numbers at infinite dilution, , together with the corresponding parameters of equations (5, 6 and 7), for aqueous solutions of (4-NP), (2-HP-β-CD) and the complex {(4-NP) + (2-HP-β-CD)}, at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

| System |

/(cm3·mol-1) |

/(cm3·kg· mol-2) |

/(10-9 cm3·

mol-1·GPa-1) |

/(10-9 cm3·

kg·mol-2 ·GPa-1) |

|

/(kg·mol-1) |

| 4-NP (m < magg) |

94.83 |

204.26 |

3.30 |

-521.29 |

4.8 |

73.09 |

| 4-NP (m > magg) |

96.54 |

90.61 |

-7.10 |

170.97 |

6.2 |

-16.63 |

| 2-HP-β-CD |

849.44 |

1420.6 |

-0.90 |

1025.3 |

41.4 |

-82.67 |

| {(4-NP)+(2-HP-β-CD)} complex |

105.82 |

1316.7 |

23.32 |

1559.8 |

3.0 |

-122.8 |

Table 3.

Values of Vϕ, βs, κϕ and nh of (2-HP-β-CD) in water at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Table 3.

Values of Vϕ, βs, κϕ and nh of (2-HP-β-CD) in water at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

m (2-HP-β-CD)/

(mol·kg-1) |

Vϕ(a)

/ (cm3 · mol-1) |

βs (b)

/(10-10 Pa-1) |

κϕ

/(10-9 cm3·mol-1·GPa-1) |

|

| 0.0036602 |

854.69 |

4.462 |

3.45 |

41.1 |

| 0.0043890 |

855.66 |

4.459 |

3.48 |

41.1 |

| 0.0051441 |

856.73 |

4.456 |

4.58 |

41.0 |

| 0.0059457 |

857.97 |

4.453 |

4.93 |

41.0 |

| 0.0066518 |

858.78 |

4.451 |

5.71 |

40.9 |

| 0.0073679 |

859.94 |

4.448 |

6.20 |

40.9 |

| 0.0081319 |

860.91 |

4.445 |

7.48 |

40.7 |

| 0.0088565 |

861.98 |

4.442 |

8.15 |

40.7 |

| 0.0096982 |

863.23 |

4.439 |

8.93 |

40.6 |

| 0.0103320 |

864.27 |

4.437 |

10.1 |

40.5 |

| 0.0112429 |

865.35 |

4.434 |

10.7 |

40.5 |

Table 4.

Values of Vϕ,mix, βs,mix, κϕ,mix and nh of (4-NP) in {(2-HP-β-CD) + water} mixed solvents at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Table 4.

Values of Vϕ,mix, βs,mix, κϕ,mix and nh of (4-NP) in {(2-HP-β-CD) + water} mixed solvents at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

m(4-NP)/

(mol·kg-1) |

Vϕ,mix /

(cm3·mol-1) |

βs,mix /

(10-10 Pa-1) |

κϕ,mix /

(10-9 cm3·mol-1 GPa-1) |

nh |

| 0.0050504 |

112.45 |

4.461 |

31.16 |

2.3 |

| 0.0061101 |

113.95 |

4.458 |

32.72 |

2.2 |

| 0.0070596 |

115.03 |

4.455 |

34.61 |

2.1 |

| 0.0082791 |

116.97 |

4.452 |

36.49 |

1.9 |

| 0.0091986 |

117.95 |

4.449 |

37.94 |

1.8 |

| 0.010200 |

119.20 |

4.446 |

38.98 |

1.7 |

| 0.011245 |

120.28 |

4.444 |

40.43 |

1.6 |

| 0.012276 |

121.81 |

4.441 |

42.18 |

1.5 |

| 0.013487 |

123.66 |

4.438 |

44.22 |

1.3 |

| 0.014388 |

124.99 |

4.436 |

46.05 |

1.2 |

| 0.015680 |

126.46 |

4.432 |

47.99 |

1.0 |

Table 5.

Partial molar volumes of transfer, ΔVϕ, for 4-NP from water to the different (2-HP-β-CD + water) mixed solvents at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Table 5.

Partial molar volumes of transfer, ΔVϕ, for 4-NP from water to the different (2-HP-β-CD + water) mixed solvents at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

m(4-NP)(a)

/ (mol·kg-1) |

m(2-HP-β-CD)(a)

/ (mol·kg-1) |

Vϕ,mix

/ (cm3·mol-1) |

Vϕ,water (b)

/ (cm3·mol-1) |

ΔVϕ

/ (cm3 · mol-1) |

| 0 |

0 |

105.82 |

94.83 |

10.99 |

| 0.0050504 |

0.0036602 |

112.45 |

95.86 |

16.59 |

| 0.0061101 |

0.0043890 |

113.95 |

96.08 |

17.87 |

| 0.0070596 |

0.0051441 |

115.03 |

96.27 |

18.76 |

| 0.0082791 |

0.0059457 |

116.97 |

96.52 |

20.45 |

| 0.0091986 |

0.0066518 |

117.95 |

96.71 |

21.24 |

| 0.010200 |

0.0073679 |

119.20 |

96.92 |

22.28 |

| 0.011245 |

0.0081319 |

120.28 |

97.12 |

23.16 |

| 0.012276 |

0.0088565 |

121.81 |

97.34 |

24.47 |

| 0.013487 |

0.0096982 |

123.66 |

97.58 |

26.08 |

| 0.014388 |

0.0103320 |

124.99 |

97.76 |

27.23 |

| 0.015680 |

0.0112429 |

126.46 |

98.03 |

28.43 |

Table 6.

Values of , VW and VI for the systems (4-NP + water) and (2-HP-β-CD + water) at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

Table 6.

Values of , VW and VI for the systems (4-NP + water) and (2-HP-β-CD + water) at T = 298.15 K and P = 101.3 kPa.

| |

/ (cm3·mol-1) |

VW

/ (cm3·mol-1) |

VI

/ (cm3 · mol-1) |

| 4-nitrophenol |

94.83 |

67.35 |

27.48 |

| 2-HP-β-cyclodextrin |

849.44 |

719.39 |

130.05 |

Table 7.

Sample description.

Table 7.

Sample description.

| Chemical Name |

Source |

CAS Number |

Mass Fraction Purity 1

|

| 2-HP-β-CD |

Sigma-Aldrich (water content 10.3 % mass fraction)2

|

128446-35-5 |

>0.98 |

| 4-NP |

Panreac Química S.L.U |

100-02-7 |

0.99 |

| Water |

Millipore-Q water (κ = 5.6 × 10−8 S cm−1) |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

), b) 4-nitrophenol (blue line

), b) 4-nitrophenol (blue line  ) and c) the equimolar mixture of both components (purple line

) and c) the equimolar mixture of both components (purple line  ).

).

), b) 4-nitrophenol (blue line

), b) 4-nitrophenol (blue line  ) and c) the equimolar mixture of both components (purple line

) and c) the equimolar mixture of both components (purple line  ).

).