1. Introduction

District heating (DH) offers a unique opportunity to effectively drive the energy transition, as it facilitates the integration of renewable energy sources and waste heat (RESWH) in urban areas while providing notable flexibility to the electricity grid [

1].

The central role of DH in future urban energy systems is anticipated because of three primary potential benefits. First, DH enables the utilisation of low-grade heat from cogeneration, heat from renewable sources [

2,

3], and waste energy [

4,

5] for the heating of urban houses, and it is able to do so even when these houses are located in different areas. Second, DH supports the use of high-efficiency technologies such as heat pumps (HP) [

6,

7] and combined heat and power (CHP) plants [

8] for space heating. Third, it serves as a source of flexibility for the electricity network by enabling low-cost storage of heat and cold in pipelines as well as thermal storage units, evading what would otherwise be high costs associated with electricity storage [

9].

To support the energy transition, DH systems require a fundamental shift in their design and operation. The scientific community agrees that three key changes are necessary. The first change is the use of distributed generation to integrate heat sources of different natures (e.g., waste heat, renewable, HPs, CHPs) [

10]. The second change is the adoption of a low operating temperature, since heat sources of different natures provide heat at temperatures lower than 100°C [

11,

12]. The third change is demand-side flexibility [

13] to ensure that the demand meets the production evolution [

14].

In this context, a main challenge concerns the transition of DH systems that are already installed into systems supplied primarily by renewable heat and waste heat. Currently, DH systems are supplied completely or primarily by fossil fuel. The urgency of this transition has been reinforced by the European Commission, which, in the 2023 Energy Efficiency Directive, introduced progressive targets for DH and cooling efficiency. From 2028, efficient DH systems must include one of the following: at least 50% renewable energy sources (RES) and waste heat (WH), 80% of heat from high-efficiency CHP (HECHP), or a combination of these sources with a minimum 5% share of RES or WH and a total share of RES, WH, and HECHP of at least 50%. Over time, the thresholds become more ambitious, with progressive targets for 2035 and 2040. By 2045 and 2050, the aim for DH systems is to be supplied by 75–100% RES and/or WH, leading the sector towards full decarbonisation. Meeting these targets implies three major transformations for existing networks.

First, current networks require new sources of heat that can exploit RES such as thermal panels, photovoltaics (PV), or wind turbines associated with HPs or WH. An interesting opportunity, then, concerns the possibility of transforming consumers into producers, buying or selling energy depending on the conditions. An example is a consumer that, having installed a solar panel or PV with HP, can sell the excess heat when such heat is available or buy heat from DH when the auto-production is not sufficient to cover its own demand. New studies in the literature are analysing how to address these needs with the design of proper bidirectional substations [

15,

16].

Second, existing DH networks are designed to operate with high supply temperatures, often exceeding 100°C. However, integrating RESWH requires a reduction in supply temperatures, since these energy sources are often available at lower levels. This transition poses significant challenges. For example, older pipelines may have insufficient diameters to maintain proper flow rates, leading to pressure drops and inefficient heat distribution. Furthermore, substations might have heat exchangers with limited surface areas, making it difficult to ensure adequate heating at reduced temperatures. Since infrastructure upgrades are essential to addressing these issues effectively, recent studies are focused on overcoming issues deriving from limitations due to unsuitable pipelines [

17] and substation [

18].

A third transition concerns the fact that in DH supplied by RES and WH, demand response is crucial for balancing supply fluctuations and maximising the adoption of carbon neutral sources. Adaptive consumption patterns help match heat availability with demand, thereby enhancing system efficiency and reducing energy waste. For this reason, current studies are focused on the adoption of demand response not only in electrical grids but also in thermal grids.

Existing studies on the transition to renewable DH systems are primarily focused on technical aspects, such as system design or temperature optimisation, and there is a research gap on a multidisciplinary analysis that include economic, social, and regulatory perspectives. Addressing this gap could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities in modernising DH networks for sustainable energy transition – highlighting how public perception, social acceptance, economic incentives, and user behaviour interact with technological and policy choices.

On this basis, the article is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the theoretical background of the article which includes studies on public perceptions of DH and studies on heating decarbonisation.

Section 3 explains the methodology that is adopted in the study.

Section 4 focuses on the analysis relative to three levels: the perception of household heating technologies and decarbonised heating options, social acceptance of renewables, and social acceptance of flexibility. Section 5 draws conclusions and policy recommendations.

2. Theoretical Background

The theoretical background of our paper is constructed by studies on public perceptions of DH, on the one hand, and by emerging literature on public perceptions of heating decarbonisation, on the other hand.

Regarding the first stream of literature of note is the study by [

19] on European households’ perceptions of DH. According to the authors, European citizens, in general, seem to have positive perceptions of DH and this is especially the case for Italians. Moreover, statistically significant differences can be observed for two socio-demographic variables, namely, age and education. Results show that older respondents perceive DH much more positively than younger respondents. People with higher education, similarly, have much more positive perceptions of DH. In addition, ecological awareness plays a role. Respondents with higher eco-awareness have a significantly more positive perception of DH. The same applies to respondents with a higher affinity for technology, when compared to respondents who do not share this affinity. However, the largest differences can be observed between respondents with greater trust in policymakers (good perception) and respondents with less trust in policymakers (worse perception of DH). In general, attitudes seem to have a stronger influence on the perception of DH than do socio-demographic factors. Finally, the study considers variables relating to the characteristics of the network and DH regulation. In particular, the study finds that respondents from countries without mandatory connection show a more positive perception of and higher level of satisfaction with DH. Moreover, respondents from countries with more liberalised price regulation show a more positive perception. Finally, respondents from countries with mainly public ownership of DH show a more positive perception.

[

20] also analyse, through both focus groups and questionnaires, the public preferences for local DH in the case of Germany. From the analysis, it emerges that costs were a main driver for acceptance of DH. The relation of costs to different energy sources was mentioned. In particular, participants welcomed the fact that DH can make use of RES and thus operate in a manner that is environmentally friendly. However, not all the respondents were prepared to pay a higher price for the protection of the environment. Accordingly, dramatic changes were highlighted in preferences for the source of energy when additional expenses were introduced.

In addition to these studies, there is emerging research on public perception of heat decarbonisation. DH is usually considered among the technological options to foster low carbon heating.

[

21] analyse public perceptions of heat decarbonisation in the UK. The review shows that there is generally low awareness amongst the general population regarding the need to decarbonise heating as well as the low-carbon heating alternatives. Indeed, the study suggests that there is high satisfaction among the public with gas central heating. This confirms other studies [

22], showing that people tend to opt for the most up-to-date version of their current system and do not consider alternatives. [

21] stress that people tend to place importance on the fact that DH can be cheaper for households as well as more efficient and effective. The downsides were perceived to be the loss of individual control, and it may also be expensive to implement. The authors suggest that any changes to DH, therefore, need to be as good as the existing heating system and require minimal changes to routines.

[

23] similarly focuses on the UK. Through an online survey, 2,226 individuals’ attitudes to three decarbonised heating technologies – namely, HPs, hydrogen heating, and DH networks – are analysed. Findings indicate that the majority of respondents had an ambivalent position. They were aware of and supportive towards decarbonised heating, especially towards HPs. However, knowledge of the different technologies was limited. Accordingly, respondents’ willingness to adopt decarbonised heating technologies appeared resistant to change. Among the variables of influence is the “social circle”, relating to the number of individuals in a respondent’s immediate social environment (e.g., family, friends) who use decarbonised heating systems. The role of tenure when considering support for decarbonised heating also emerged as a consideration. In particular, unlike owners, renters ‘may experience increased precarity, as decarbonised heating introduces uncertainties regarding disruption to living spaces and changes to existing bills or rent’([

23], p.10).

[

24] – through a comparative assessment of five original and representative national surveys in Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom – explore public attitudes towards household heat decarbonisation in Europe. The results again stress a high satisfaction with existing, often fossil fuel-based, heating systems. Householders are reluctant to change their heating systems in the near future, an obstinacy that is, in part, driven by low familiarity with and knowledge of alternative systems. Moreover, the finding emerges that the quality of their heating experiences (e. g., how warm and comfortable they can get, how convenient this is, what it costs) is more important than the type of heating system or source of energy. This is also confirmed by other studies ([

25]; [

26]). Ultimately, the value-action gap becomes clear: respondents profess to highly value environmental protection for future heating systems, but this does not translate into changed heating practices or a readiness to adopt low-carbon heating systems.

These results seem to be confirmed by qualitative studies. For example, [

27] analyse qualitative data from deliberative workshops with members of the public in the UK concerning perceptions of heat decarbonisation. Public awareness in the UK regarding the need to decarbonise heat, and the potential impacts of doing so, remains low. Cost also plays a crucial role in influencing public perceptions.

From this literature review, it can be concluded that public attitudes towards decarbonised DH remain under-researched. Our contribution aims to address this gap, drawing from a survey on the case study of the city of Turin in Northwest Italy.

In addition, our study will contribute to research on flexibility of energy demand. Indeed, heating decarbonisation is closely connected to the still understudied issue of flexibility, since the transition towards low-carbon DH entails not only the further expansion of renewable energy but also the development of smart grids. Flexibility requires consumers to develop the capacity to alter their usual electricity consumption (or production) patterns in time and space, either implicitly in response to price signals or market incentives or explicitly in reaction to specific demands aggregators ([

28]). Most of the literature on this issue has adopted an economic lens ([

29]; [

30]; [

31]; [

32]), emphasising behavioural change and focusing on the role of price incentives such as time-of-use pricing (e.g., peak and off-peak hours) to shift public perceptions and consumption patterns. However, recent sociological research (e.g., [

33]; [

34]) has stressed the need for a more complex understanding of flexibility as influenced by a wide variety of social factors including social practices, household composition, culture, life stage, wealth, etc. In particular, the issue of flexibility capital ([

35]) has been advanced to stress the role of social variables and social inequality in the participation of energy demand management initiatives ([

36]; [

37]). This will also be considered in our study.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodology of our study is based on a survey of 1,200 respondents (N = 1200) who were recruited among the citizens of Turin. Half of the surveys were conducted through online questionnaires and half were conducted through telephone interviews. Located in the Northwest Italy, Turin is one of the largest cities in the country with a population of about 800,000 inhabitants. Almost half of the population is connected to a DH system, mostly based on fossil fuel. The network is operated by a mixed public-private company (Iren) in a system of liberalised prices.

The features of the sample are the following: 48.8 % males, 50.9% females; 27% between 25 and 39 years old, 72.9% between 40 and 74 years old; 51.5% hold an undergraduate degree, 37.8% hold a university degree and of these 23.7% a scientific degree; 13.9 % has a family unit composed of only one person, 34. 5% of 2 persons, 51.6% of 3 persons or more; 36.4% have one or more children under 18 years old; 78.8% own their house, 20.2% rent their house, 0.9% live in social housing; regarding the average net family income, 25.3% have an income going from 500 to 2,000, 37.4% have an income between 2,000 and 4,000, and 37.3% have an income over 4,000.

The questionnaire was made of 21 questions. Key issues investigated through the questionnaire included:

a) Public perceptions of different decarbonised heating options: Here, questions aimed to evaluate respondents’ experiences with different types of heating in the main home and in the secondary home. Included in such considerations were their perceptions of different qualities – especially comfort, cost, and control – of the different heating technologies; their level of knowledge in relation to different low-carbon heating technologies (DH; DH with renewables; hydrogen; HP); their perceptions of DH and its association to issues like nature of the energy source (renewable vs. fossil), control vs. freedom of energy use, energy efficiency, energy saving, and elite enrichment.

b) Social acceptance of renewables: Here, questions aimed to evaluate public perceptions regarding the adoption of renewables in their home to produce heating (thermal PV and HPs) with respect to different ownership and managing structures; their willingness to pay to have a DH 100% from renewables; types of incentives that would convince the respondent to shift to a DH 100% from renewables; their willingness to pay to have a renewable energy technology on the roof of the house (e.g., thermal PV).

c) Social acceptance of flexibility of energy demand: Here, questions aimed to evaluate public perceptions regarding demand response and the types of guarantees/incentives needed to accept a modification of heating timing by the energy provider.

Like [

19] but with a focus on decarbonisation, in order to identify possible relationships between perceptions of DH and socio-economic influencing factors, we consider a number of variables in our survey. First, socio-demographic factors such as gender, age, and education were collected. In addition, housing tenure and family composition were considered. Furthermore, the attitudes and practices of respondents in terms of eco-awareness, technology affinity, trust in public institutions, and intermediate organisations were included.

Eco-awareness: To capture this attitude, participants were asked to answer the following question: “Think about the last month, how often did you adopt the following behaviours?” An additive index was created by summing up how many times in the last month the respondent has engaged in the following behaviours: (1) used public transport or a bicycle; (2) consumed organic or zero-mileage food; or (3) used a water bottle instead of disposable plastic bottles when out of the house. For each item, the possible answers ranged from 0 = never to 3 = six times or more. An index was built summing up all the answers. The index ranged between 0 (no ecological behaviour in the last month) and 9 (highest ecological behaviour), with a mean of 5.0. A principal component analysis confirmed the index’s unidimensionality, showing that the first component explained 48.6% of the variance.

Trust: To capture this attitude, participants were asked to express their level of trust in various institutions and organisations. An additive index was then obtained by considering the degree of trust (measured as 0 = not at all; 1 = a little; 2 = quite a lot; 3 = a lot) in the following institutions: the media; banks; energy companies; parties; the EU; national government; and local government. The sum of the answers for each item resulted in an index with values ranging from 0 (no trust) to 21 (highest trust), with a mean of 8.1. A principal component analysis confirmed the unidimensionality of this index, showing that the first component explained 51.1% of the variance.

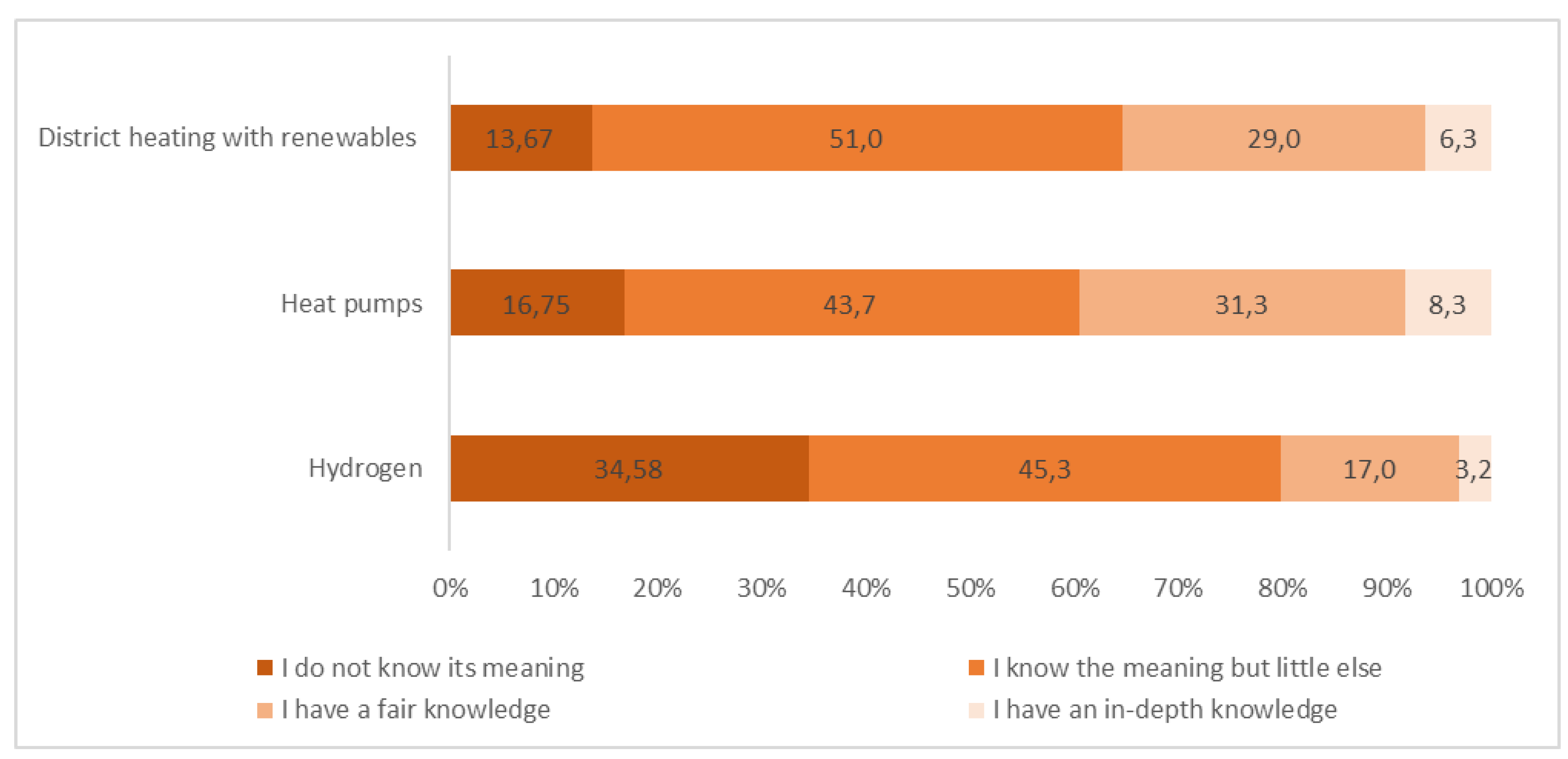

Technology affinity: An additive index was created considering the question: ‘How well do you think you know the functioning of the following systems or technologies?’. The technologies to assess were (1) hydrogen, (2) a HP, (3) a DH network powered by renewable sources, and (4) a DH network. The possible answers ranged from 0 (I do not know the meaning) to 3 (I have in-depth knowledge). The sum of the answers given to each item made it possible to construct an index with values ranging from 0 (no knowledge) to 12 (maximum knowledge), with a mean of 5.0. The unidimensionality of this concept was checked with a principal component analysis, which showed that the first component explains 64.9% of the variance.

Finally, two further additive indices were created. The first, called economic guarantees for heating flexibility index, measures the guarantees required by the respondent to accept a change in the heating switching times by the energy service provider. The measure was built by adding up the answers to the following items: (1) guarantee of no increase in consumption and costs in the bill; (2) a fixed monthly/daily economic reward; and (3) A reduction in the price of energy per kWh. As the possible answers were 0 = no and 1 = yes, the values of the additive index vary between 0 (no guarantee required) and 3 (all guarantees required), with a mean of 1.2. The unidimensionality of the index was confirmed by a principal component analysis, which showed that the first component explains 53.8% of the variance.

The second relates to the propensity to install solar thermal on one’s home index. This index measures the willingness to install a solar thermal system on the roof of one’s home and was created by adding up the answers given to the items of this question: ‘For the same price, how much would you personally favour the following installations at your home?’. The items to be assessed were: (1) solar thermal on the roof (for hot water production) owned by the condominium owners; (2) solar thermal on the roof owned by the company providing DH; (3) solar thermal on the roof owned by the company providing DH and with the municipality as guarantor; and (4) solar thermal on the roof managed according to a community approach (energy community type). For each item, the possible answers were 0 = not at all favourable; 1 = not very favourable; 2 = quite favourable; 3 = very favourable. Summing up the answers of all items resulted in an index with values between 0 (never favourable) and 12 (always very favourable), with a mean of 7.1. The unidimensionality of the index was checked with a principal component analysis, which showed that the first component explained 65.0% of the variance.

To analyse the data, the following techniques were used: analysis of variance (ANOVA), bivariate correlation, and multiple regression. ANOVA is a statistical technique that compares the mean of a numerical variable across categorical variables. Multiple regression, on the other hand, is a type of regression that allows the development of a predictive model where a dependent variable (in our case, the variables concerning the willingness to install RES or to switch to DH) is expressed as a result of its simultaneous relationship with several independent variables. In the present research, we considered sociographic dimensions, attitudes, and other orientations concerning energy sources as independent variables.

4. Results

4.1. Perceptions of Household Heating Technologies and Decarbonised Heating Options

The majority of the sample use fossil fuel-based technology to heat their home with either DH (45.8%) or an oil/gas boiler (42.3%). Only 5% have a HP, 2.9% have electric heating, and 2% have a wood or pellet stove.

In light of citizens’ knowledge on the three low carbon alternatives (

Figure 1) – namely, hydrogen, HPs, and DH with renewables – the technology which the public appears to know less about is hydrogen, with only 20% of the sample attesting to average or in-depth knowledge. The public appears more knowledgeable in relation to DH with renewable sources, with 35.3% of the sample attesting to average or in-depth knowledge. Further, the public appears most informed about HPs , with almost 40% of the sample attesting to average or in-depth knowledge. Still, it is evident how, in relation to all three technologies, there is a problem of information with the public. This much is clear by, for example, a percentage that goes from 60% to 80% of the public saying that it is completely unaware of the technological option suggested in the question or that it knows only the meaning and nothing more.

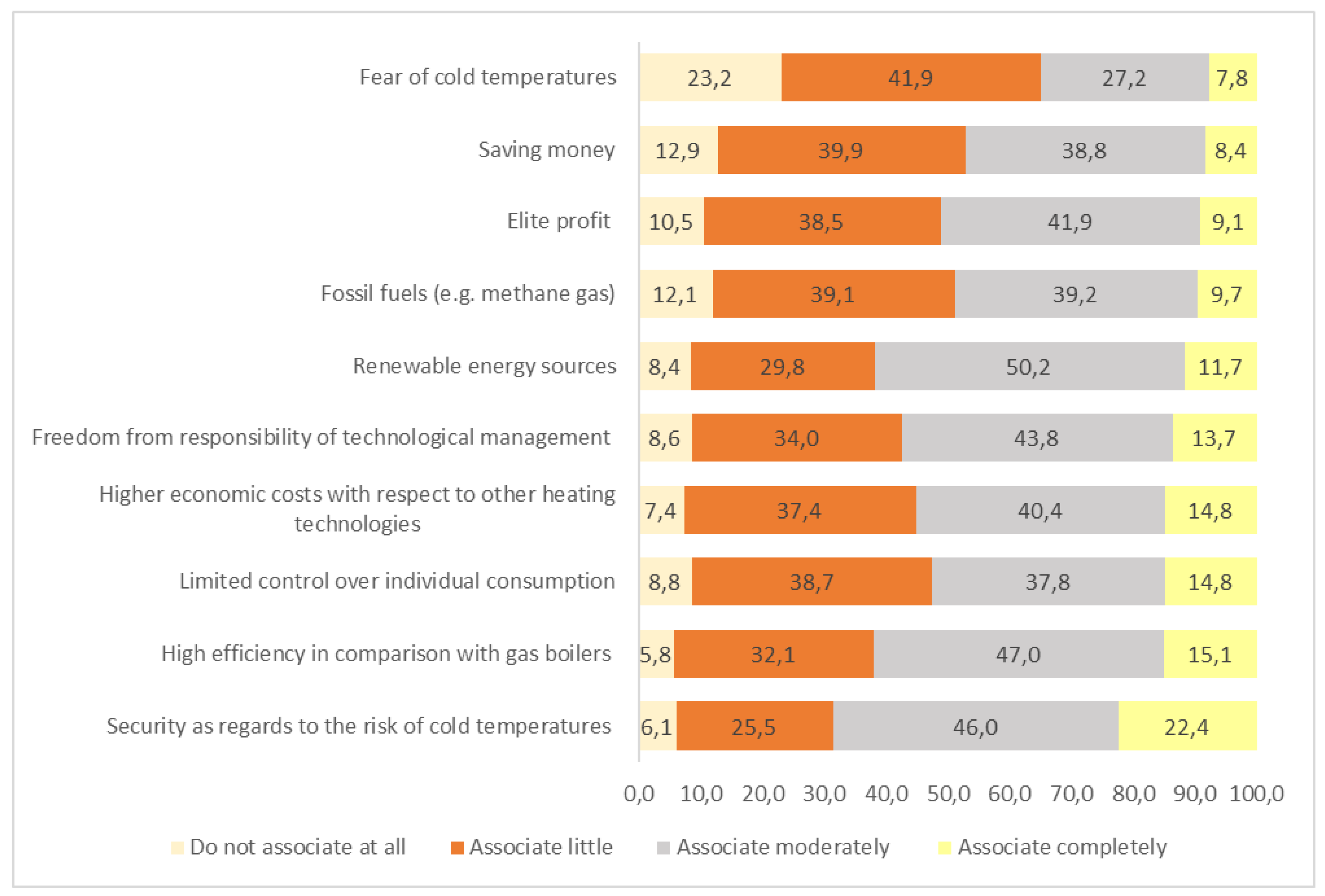

Concerning DH, as it emerges from

Figure 2, it is interesting to note that 60% of the sample associates DH with renewables (sum of those who associate it moderately and those who associate it completely). Other positive qualities which are strongly associated with DH are high efficiency in comparison with gas boilers (62.1%), security regarding the risk of cold temperatures (68.4%), and freedom from responsibility of technological management (57.4%). DH is instead quite divisive in relation to the associated economic costs: 55% of the sample associate DH with higher economic costs relative to other heating technologies, 51% associate it with elite profit, and 52.6% with limited control over individual consumption.

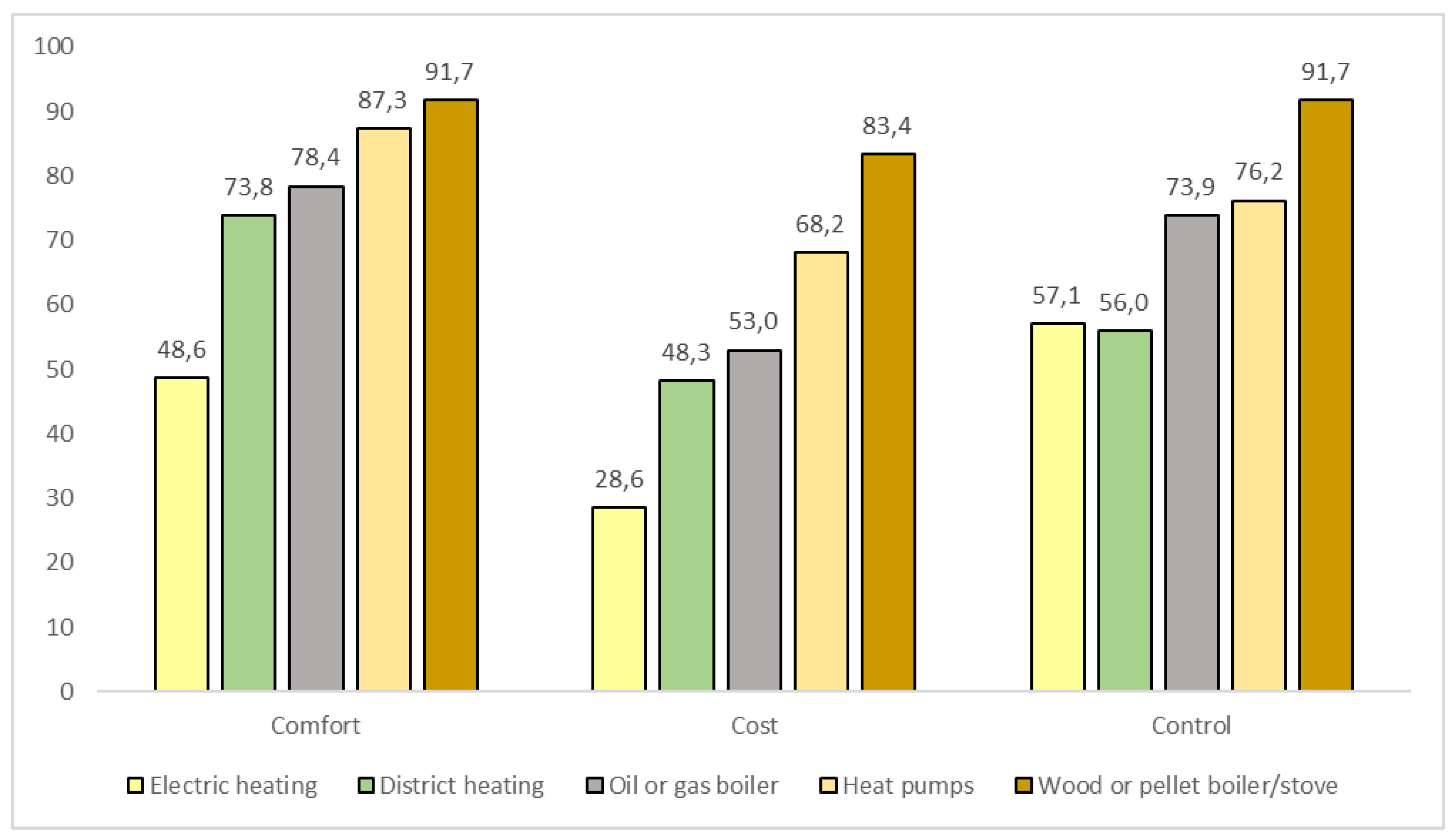

These results seem to be confirmed by

Figure 3, comparing the different heating technologies in relation to the features of comfort, cost, and control. Here, DH rates quite well in relation to the issue of comfort, with 73.8% of the sample giving an evaluation of good and optimum regarding this item. By contrast, but regarding the associated costs of this technology, a good or optimum evaluation was given by less than the half of the sample (48.3%). Regarding the feature of control, the sample is divided, with 56% giving a good or optimum evaluation. Ultimately, among the technologies which have the highest evaluations (sum of those who gave an evaluation of good and optimum) in relation to all three qualities, there is a low carbon option like HPs.

Social Acceptance of Renewables

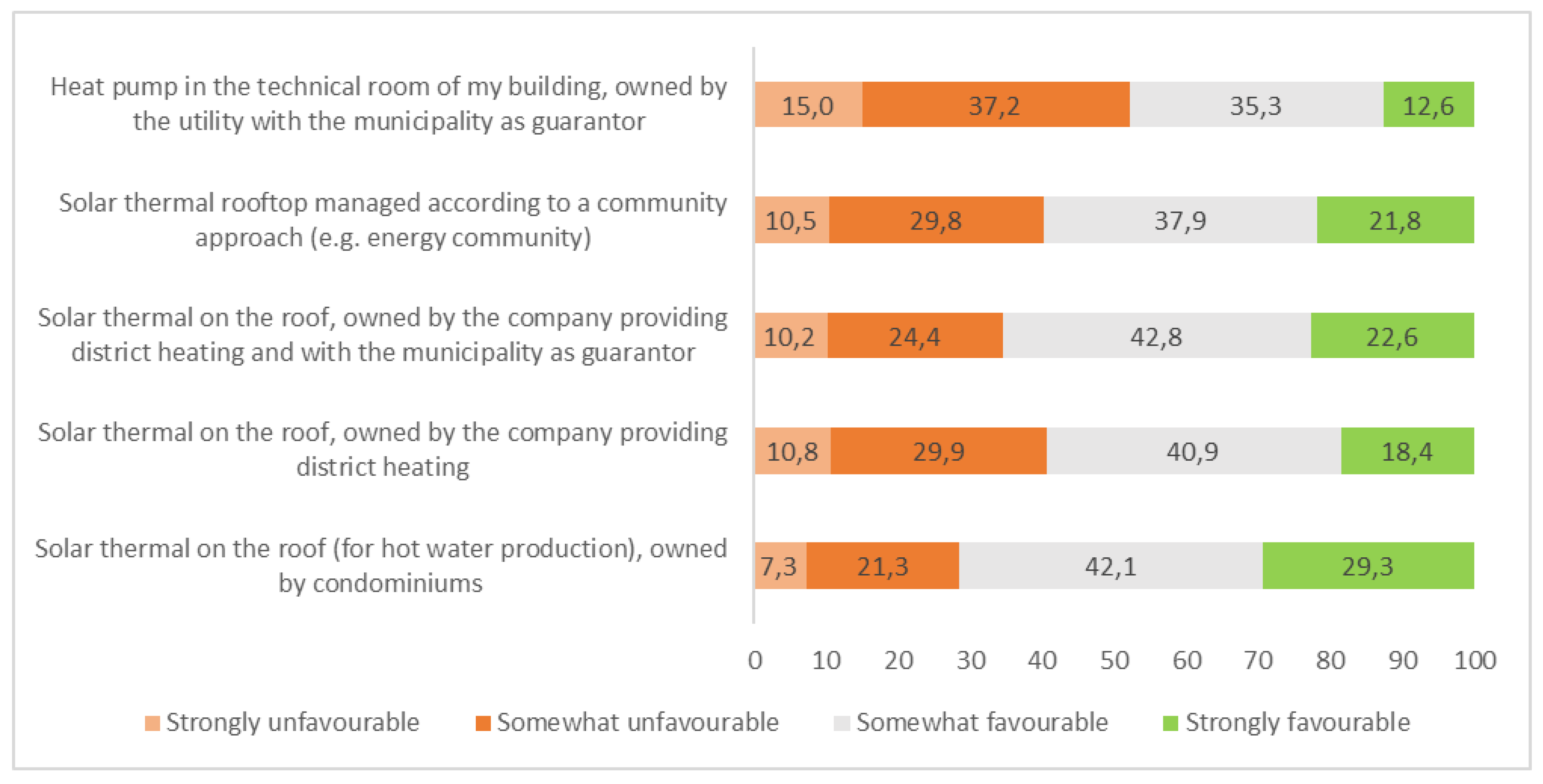

For decarbonised heating systems to diffuse, it is crucial that we address public acceptance of renewables. To evaluate respondents’ social acceptance of renewables integration in housing heating systems, the results of three key questions were analysed. The first question aimed to evaluate the degree to which the respondent felt favourably towards installing thermal PV of HPs in their home. In this question, different ownership and management structures of the technological installations were considered. The results analysed in

Figure 4 show that the most acceptable technological solutions are either thermal PV on the roof owned by the inhabitants of the building with 71.4% of respondents judging as much or quite favourable, or thermal PV on the roof owned by the utility who provides the DH and with the local municipality as guarantor. These results seem to line up with research on renewable energy communities, which shows how collective forms of energy prosumerism improve acceptability of renewable energy facilities [

38] The less accepted option in

Figure 4 is HP in the condominium technical room owned by the utility and with the local municipality as guarantor. This seems to confirm literature stressing that, on the one hand, public perceptions of HPs are, in general, low[39], while on the other hand, HPs are potentially difficult to adopt as a technology because they may require a significant change in heating practices compared with gas boilers.

A second key question is the respondents’ willingness to pay for the shift to a DH system based on renewables. The willingness to pay for low carbon heating of the sampled citizens appears extremely low. More than half of the sample – 52.2% – say that they are not willing to pay anything and 34.1% say they would pay 10% more as the maximum.

Those who are not willing to pay more for a DH system based on renewables tend to be female rather than male (54% female), older (61% between 55 and 65), low educated (74. 7% has an elementary or middle school diploma), have a family with small children (68.2% have 3 or more children under 18 years old), have low income (63.7% have an average family income between 500 and 2,000 euros), and have a more precarious housing tenure (58.9% do not own their house).

The ANOVA of the results of this question confirms these conclusions and allows us to identify a more complete profile of the citizens who are less available to adopt a DH system based on renewables. Of note, those who are not willing to pay any additional cost have an average age of 51 years versus those who are willing to pay more than 20% have an average age of 39 years. Concerning the index of technology affinity, those who are not willing to pay any additional cost have the lowest average score – 4.61 – versus a value of 6.35 for those who are willing to pay more than 20%. We can observe a linear relation relative to the trust index. Those who are not willing to pay any additional cost tend to have a lower trust towards institutions at the local, national, and European level as well as towards the media and energy utilities (average score of 7). By contrast, those who are willing to pay more than 20% have the highest average score on trust (10.27). Finally, we tested the environmental awareness index. Here, those who are not willing to pay any additional cost are those who show the lowest level of environmental awareness, with an average score of 4.68, versus an average score of 6 for those who are willing to pay more than 20%.

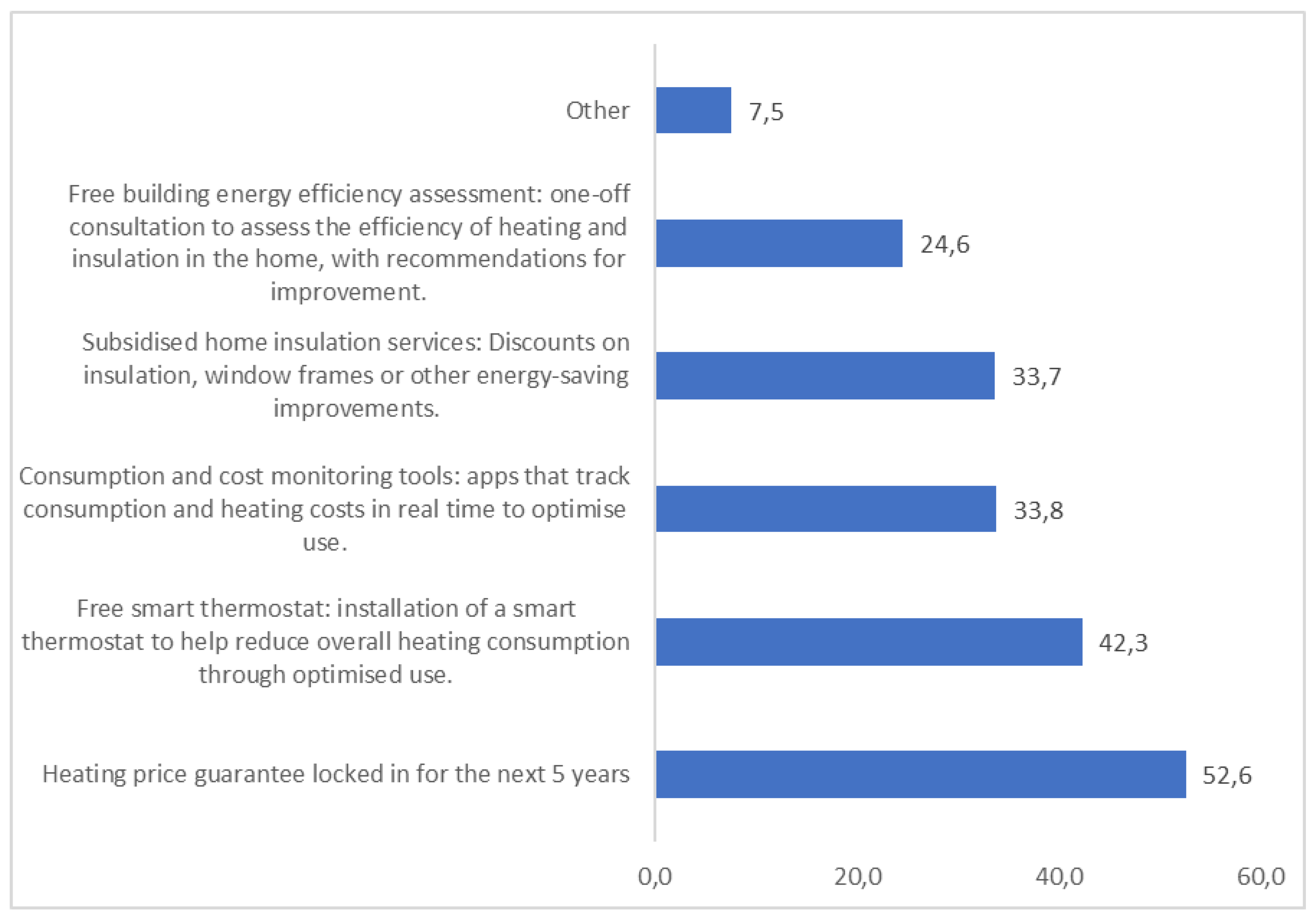

A third question concerns the types of incentives that would convince the respondent to shift to a DH system 100% from renewables. From

Figure 5, it emerges that the economic incentive is of paramount importance. Indeed, more than half of the sample (52.6%) would consider shifting to a DH system based on renewables with a 10% increase in costs if they were guaranteed fixed DH prices for the next 5 years. In addition, the free installation of a smart thermostat to optimise energy consumption patterns is positively considered by a significant part of the sample (42.3%).

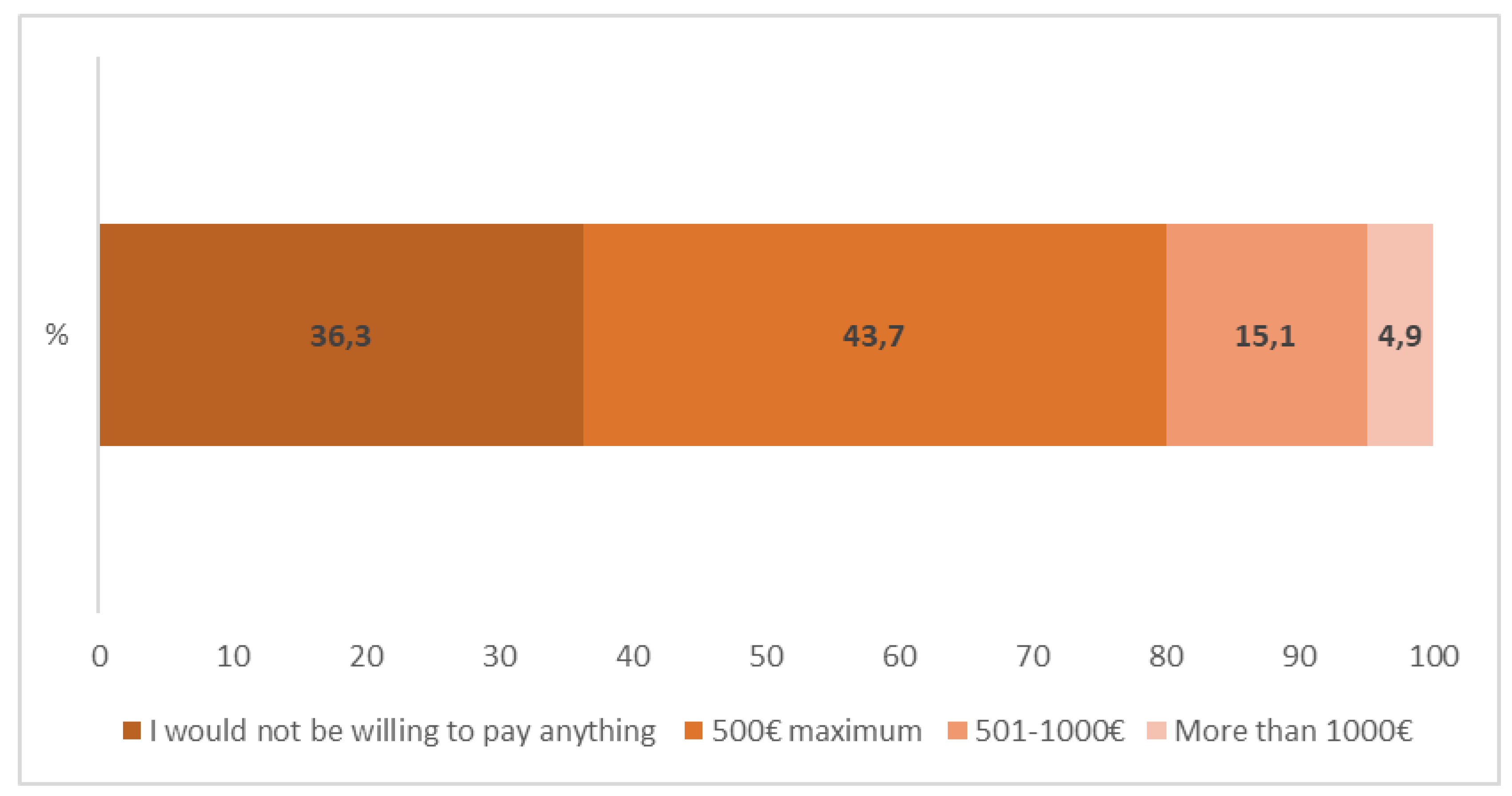

A fourth question concerns the respondents’ willingness to pay (how much they would be available to pay) for the installation of the roof on the house of a renewable energy technology (e.g., thermal PV). This would reduce the heating costs by 10%.

Figure 6 shows how, in comparison with the previous question on decarbonised DH, in this case the percentage of those who are not available to adopt the new technology at all decreases to 36.3% (persons not willing to pay anything more), while the majority of the sample (43.7%) shows a limited availability to spend (maximum 500 euros). These data show a very low acceptance of renewables as well as a very low availability to integrate them in the housing heating system.

In this case, those who are not willing to pay for renewables on their roof tend to be female rather than male (39.8% female vs. 32.9% male), older (45.6% older than 66 years of age), low educated (61.1% have an elementary or middle school diploma), low income (51.5% have an average family income between 500 and 2,000 euros vs. 25.1 more than 3,000 euros), and have a more precarious housing tenure (45.5% do not own their house vs. 33.9 who own it).

The ANOVA confirms the profile of the citizens who are less interested in renewables, and this information emerged in the question about decarbonised DH. In this case, but in addition to the citizens who are less available to integrate renewable heating technologies in their house, respondents are middle-aged (average age of 52 years), have the lowest average score relative to the index of technology affinity (score of 4.31) which shows a limited knowledge of renewable heating technologies, have the lowest score relative to the index of trust towards institutions, the media, and energy utilities (average score of 7.25), and show the lowest level of environmental awareness (average score of 4.39).

These results are confirmed by bivariate correlation and multiple regression. The bivariate correlation shows that the willingness to pay for the installation on the roof of the house of a renewable energy technology is highly and positively correlated with the following variables: education, number of children below 18 years of age, trust towards institutions, intermediate organisations, energy utilities, technological affinity, eco-awareness, and house ownership (

Table 1). Interestingly, the correlation between average family income and willingness to pay, though positive, is less strong than the other variables. The willingness to pay for renewable technologies is instead strongly and negatively correlated with age.

A multiple regression was undertaken in relation to the question regarding the willingness to pay for a 100% renewable energy DH system and the question regarding the willingness to pay for renewable energy technology (

Table 2). With respect to the first question, the model explains 32% of the variance of the dependent variable. The statistically and positively correlated variables are education (the more educated, the more available) and trust in institutions (greater trust, more willingness). As expected, the willingness to pay for the installation of a renewable energy source has the highest effect – 0.38 – confirming the model’s internal consistency. The statistically and negatively correlated variables are age (young people are more willing to pay) and financial guarantees for demand flexibility (people who tend to accept flexibility without requiring much in guarantees are also more willing to pay).

Regarding the latter question, the model explains 34% of the variance of the dependent variable. As shown by

Table 3, the significantly and positively correlated variables are the following: income (the richest are the most willing), home ownership (those who own their house are more available), ecologism (those who have more ecological), the annual cost of heating (the more the cost of the heating the more willing one is), and, as expected, the willingness to pay for DH from renewable sources in addition to the propensity to install solar thermal. This last result confirms the internal consistency of the model. The statistically and negatively correlated variables are age (younger people are more willing) and gender (males are more willing).

4.3. Social Acceptance of Flexibility of Demand (Demand Response)

As discussed above, the flexibility of demand and the acceptance of demand response appear crucial to fostering decarbonised heating systems which integrate intermittent renewable sources. To investigate this issue, a first question concerned the availability to give the energy utility the freedom to modify, within a specific range defined contractually, the morning switch-on time of the heating system to reduce the environmental impacts (

Table 4). Here, the majority of the citizens in the sample (57.2%) appear to be in favour of this introduction of flexibility measures, 23.8% are contrary, and 19.1% do not express an opinion.

Those who oppose this measure tend to be older (31% over 66 years of age, 27.4% between 55 and 65 years of age) and have low-middle income (45% have an average family income between 500 and 3,000 euros). However, differences related to sex, education, number of household members, and house tenure are not significant.

A second question concerned the guarantees or incentives that the citizens would like to receive from the energy service manager to agree to changing the switch-on times of the heating. Here again, the centrality of economic concerns and motivations to adopt low carbon solutions is confirmed. Indeed, the options which received the most support were the guarantee of not having an increase in costs on the energy bill (48.2%) and the incentive of a reduction in the price of energy per kWh (46.8% of responses).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of complementing technical innovations in DH systems with a deeper understanding of socio-economic factors that shape public perceptions and behaviours. While DH is generally perceived positively in terms of comfort and efficiency, widespread scepticism remains concerning costs, control, and fairness – particularly among older, lower-income, and less tech-savvy populations.

Our findings underscore a clear gap between citizens’ environmental values and their willingness to invest in renewable DH. Moreover, social acceptance of flexibility in energy demand emerges as a complex issue, influenced not only by cost-related guarantees but also by structural inequalities and lifestyle constraints.

Accordingly, the results of this study highlight the critical role of economic incentives in shaping public acceptance of renewable district heating systems. While many respondents recognize the environmental and technical benefits of such systems, their willingness to pay remains strongly conditioned by socio-economic status, trust in institutions, and perceived financial risk. This underscores the need for policy frameworks that address affordability through targeted measures. Fixed pricing schemes, income-sensitive subsidies, and installation grants for renewable-compatible technologies (such as heat pumps and smart meters) could significantly lower the perceived entry barrier, particularly for renters, low-income households, and large families—groups consistently less willing or able to bear additional costs.

Beyond affordability, economic instruments should be designed to foster active engagement and flexibility among consumers. The positive response to guaranteed incentives for demand-side management, combined with the observed willingness to participate in collective renewable initiatives, suggests strong potential for integrating economic rewards with behavioural nudges. Energy policies that support community ownership models, reward prosumers through net-billing schemes, and link financial incentives with transparency and trust-building requirements could enhance participation and legitimacy. In this regard, economic policy tools must be conceived not merely as a tool for cost recovery or market correction, but as a means of cultivating social inclusion, institutional trust, and sustained behavioural change necessary for a just and effective energy transition.

In conclusion, what emerges from our analysis is that addressing the current barriers to adoption of renewable DH solutions requires a multidimensional approach: one that integrates affordability, trust-building, technological literacy, and inclusive governance. Such an approach would complement ongoing regulatory efforts, including the European Commission’s 2023 Energy Efficiency Directive, which introduces progressive targets to increase the share of RESs, WH, and high-efficiency cogeneration in DH systems, thereby providing a clear framework that guides the sector’s transition towards decarbonisation. Policy interventions that ignore these social factors risk falling short, even when technically sound. As Italy and other countries strive for low carbon heating solutions, aligning technological advancement with social realities will be essential to ensuring a just and effective energy transition.

While this study provides some novel and valuable insights into the socio-economic drivers of public perception around renewable DH in Italy, it has some limitations. First, the analysis is geographically focused on a single urban case study – Turin – which, despite being a relevant site due to its large and mature DH network, may not fully represent the diversity of regional, rural, or socio-cultural contexts across the country. Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases related to social desirability and knowledge gaps among respondents. Third, while several socio-demographic and attitudinal factors were explored, other influential dimensions such as political orientation, cultural values, or historical energy experiences were not included.

Future research could extend this investigation to other Italian cities or regions with different DH penetration rates and socio-economic profiles as well as to rural areas where decentralised or community-based heating models might be more relevant. Longitudinal studies would be valuable to assess how public perceptions evolve over time as decarbonisation policies and technologies are implemented. Finally, integrating further qualitative methods – such as focus groups or ethnographic approaches – could deepen understanding of how everyday practices, values, and structural constraints shape engagement with low-carbon heating systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.; methodology, N.M. and E.L.; validation, E.L.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, N.M., C.R., F.M., M.C., E.G.; data curation, E.L..; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.,C.R., F.M., M.C., E.G., supervision, N.M.; funding acquisition, E.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU, in the context of PRIN 2022, project ReveDH: Holistic approach for energy transition. Challenge on REVolutionary changE to 100% renewable District Heating"

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DH |

District Heating |

| RES |

Renewable Energy Sources |

| RESWH |

Renewable Energy Sources and Waste Heat |

| HP |

Heat Pumps |

| CHP |

Combined Heat and Power |

| WH |

Waste Heat |

| HECHP |

High-Efficiency CHP |

| PV |

Photovoltaics |

References

- Connolly, D., Lund, H., Mathiesen, B. V., Werner, S., Möller, B., Persson, U., Boermans, T., Trier, D., P. A. Østergaard, & Nielsen, S. (2014). Heat Roadmap Europe: Combining district heating with heat savings to decarbonise the EU energy system. Energy Policy, 65, 475–489. [CrossRef]

- Seyboth, K., Beurskens, L., Langniss, O., & Sims, R. E. (2008). Recognising the potential for renewable energy heating and cooling. Energy Policy, 36(7), 2460–2463. [CrossRef]

- Madlener, R. (2007). Innovation diffusion, public policy, and local initiative: The case of wood-fuelled district heating systems in Austria. Energy Policy, 35(3), 1992–2008. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H., Xia, J., & Jiang, Y. (2015). Key issues and solutions in a district heating system using low-grade industrial waste heat. Energy, 86, 589–602. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B., Liu, H., Wang, R. Z., Li, H., Zhang, Z., & Wang, S. (2017). A high-efficient centrifugal heat pump with industrial waste heat recovery for district heating. Appl. Therm. Engineering, 125, 359–365. [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, P. A., & Andersen, A. N. (2018). Economic feasibility of booster heat pumps in heat pumpbased district heating systems. Energy, 155, 921–929.

- Capone, M., Guelpa, E., & Verda, V. (2023). Optimal installation of heat pumps in large district heating networks. Energies, 16(3), 1448. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F., Fu, L., Sun, J., & Zhang, S. (2014). A new waste heat district heating system with combined heat and power (CHP) based on ejector heat exchangers and absorption heat pumps. Energy, 69, 516–524. [CrossRef]

- Guelpa, E., Bischi, A., Verda, V., Chertkov, M., & Lund, H. (2019). Towards future infrastructures for sustainable multi-energy systems: A review. Energy, 184, 2–21. [CrossRef]

- Lund, H., Østergaard, P. A., Chang, M., Werner, S., Svendsen, S., Sorknæs, P., Thorsen, J. E., Hvelplund, F., Mortensen, B. O. G., Vad Mathiesen, B., Bojesen, C., Duic, N., Zhang, X., & Möller, B. (2018). The status of 4th generation district heating: Research and results. Energy, 164, 147–159. [CrossRef]

- Averfalk, H., Benakopoulos, T., Best, I., Dammel, F., Engel, C., Geyer, R., Gedmundsson, O., Lygnerud, K., Nord, N., Oltmanns, J., Ponweiser, K., Schmidt, D., Schrammel, H., Skaarup Østergaard, D., Svendsen, S., Tunzi, M., & Werner, S. (2021). Low-temperature district heating implementation guidebook: Final report of IEA DHC annex TS2. Implementation of low-temperature district heating systems. Fraunhofer IRB Verlag.

- Guelpa, E., Capone, M., Sciacovelli, A., Vasset, N., Baviere, R., & Verda, V. (2023). Reduction of supply temperature in existing district heating: A review of strategies and implementations. Energy, 262, 125363. [CrossRef]

- Guelpa, E., & Verda, V. (2021). Demand response and other demand side management techniques for district heating: A review. Energy, 219, 119440. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. K., Jokisalo, J., Kosonen, R., Kinnunen, T., Ekkerhaugen, M., Ihasalo, H., & Martin, K. (2019). Demand response events in district heating: Results from field tests in a university building. Sustainable Cities and Society, 47, 101481. [CrossRef]

- Pipiciello, M., Trentin, F., Soppelsa, A., Menegon, D., Fedrizzi, R., Ricci, M., Di Pietra, B., & Sdringola, P. (2024). The bidirectional substation for district heating users: Experimental performance assessment with operational profiles of prosumer loads and distributed generation. Energy and Buildings, 305, 113872. [CrossRef]

- Pipiciello, M., Caldera, M., Cozzini, M., Ancona, M. A., Melino, F., & Di Pietra, B. (2021). Experimental characterization of a prototype of bidirectional substation for district heating with thermal prosumers. Energy, 223, 120036. [CrossRef]

- Capone, M., Guelpa, E., & Verda, V. (2024). Exploring opportunities for temperature reduction in existing district heating infrastructures. Energy, 302, 131871. [CrossRef]

- Capone, M., Guelpa, E., & Verda, V. (2023). Potential for supply temperature reduction of existing district heating substations. Energy, 285, 128597. [CrossRef]

- Billerbeck, A., Breitschopf, B., Preuß, S., Winkler, J., Ragwitz, M., & Keles, D. (2024). Perception of district heating in Europe: A deep dive into influencing factors and the role of regulation. Energy Policy, 184, 113860. [CrossRef]

- Zaunbrecher, B. S., Arning, K., Falke, T., & Ziefle, M. (2016). No pipes in my backyard?: Preferences for local district heating network design in Germany. Energy Res. & Soc. Science, 14, 90–101.

- Ipsos MORI and The Energy saving Trust (2013). Homeowners' willingness to take up more efficient heating systems. Department of Energy & Climate Change, UK.

- Smith, W., Demski, C., & Pidgeon, N. (2025). Public perceptions of heat decarbonisation in Great Britain: Awareness, values and the social circle effect. Energy Res. & Soc. Science, 119, 103844. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B. K., Demski, C., & Noel, L. (2021). Beyond climate, culture and comfort in European preferences for low-carbon heat. Glob. Environmental Change, 66, 102200. [CrossRef]

- Mallaband, B., & Lipson, M. (2020). From health to harmony: Uncovering the range of heating needs in British households. Energy Res. & Soc. Science, 69, 101590. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B. K., & Martiskainen, M. (2020). Hot transformations: Governing rapid and deep household heating transitions in China, Denmark, Finland and the United Kingdom. Energy Policy, 139, 111330. [CrossRef]

- Shirani, F., Thomas, G. H., Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (2024). Going backwards? A temporal perspective of what constitutes improvement in domestic heating transitions. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 20(1), 2347075. [CrossRef]

- Freire-Barceló, T., Martín-Martínez, F., & Sánchez-Miralles, Á. (2022). A literature review of Explicit Demand Flexibility providing energy services. Electric Power Systems Research, 209, 107953. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P., Coke, A., & Leach, M. (2016). Financial incentive approaches for reducing peak electricity demand, experience from pilot trials with a UK energy provider. Energy Policy, 98, 108–120. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, P., & Winzer, C. (2022). Tariff menus to avoid rebound peaks: Results from a discrete choice experiment with Swiss customers. Energies, 15(17), 6354. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, R. (2018). Follow the price signal: People’s willingness to shift household practices in a dynamic time-of-use tariff trial in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. & Soc. Science, 46, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, A., Honkapuro, S., Ruiz, F., Stoklasa, J., Annala, S., Wolff, A., & Rautiainen, A. (2023). Residential consumer preferences to demand response: Analysis of different motivators to enroll in direct load control demand response. Energy Policy, 173, Article 113420. [CrossRef]

- Powells, G., & Fell, M. J. (2019). Flexibility capital and flexibility justice in smart energy systems. Energy Res & Soc. Science, 54, 56–59. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G., Demski, C., & Pidgeon, N. (2020). Energy justice discourses in citizen deliberations on systems flexibility in the United Kingdom: Vulnerability, compensation and empowerment. Energy Res. & Soc. Science, 66, 101494. [CrossRef]

- Powells, G., Bulkeley, H., Bell, S., & Judson, E. (2014). Peak electricity demand and the flexibility of everyday life. Geoforum, 55, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Savelli, I., & Morstyn, T. (2023). The energy flexibility divide: An analysis of whether energy flexibility could help reduce deprivation in Great Britain. Energy Res. & Soc. Science, 100, 103083. [CrossRef]

- Wyse, S. M., Das, R. R., Hoicka, C. E., Zhao, Y., & McMaster, M. L. (2021). Investigating energy justice in demand-side low-carbon innovations in Ontario. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3, 633122.

- Magnani, N. & Carrosio, G. (2021). Understanding the Energy Transition. Civil society, territory and inequality in Italy. Cham: Palgrave macmillan.

- Becker, S., Demski, C., Smith, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2023). Public perceptions of heat decarbonization in Great Britain. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment, 12(6), e492. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).