Submitted:

08 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Peeters et al. [15] (p. 22), defining overtourism as “… a state that is tightly linked to a situation in which tourism impacts, at certain times and in certain locations, exceed physical, ecological, social, economic, psychological, and/or political capacity thresholds”, associated with the large volume of visitors.

- Mihalic [18], perceiving overtourism as the rapid escalation and growth of tourism supply and demand, which result in the excessive use of destinations' natural resources and the destruction of their cultural attractions, while also negatively affecting the local socioeconomic environment in the long run.

- UNWTO [1], stressing the social dimension and perceiving overtourism on the ground of the impacts of tourism on a destination, or parts thereof that are excessively influencing perceived quality of life of citizens and/or quality of visitors' experiences in a negative way.

- Vourdoubas [23], featuring overtourism as a phenomenon occurring mainly in popular tourism destinations and being mostly expressed by the large number of tourists – a “tourism storm” or “tourism invasion” – that overwhelms the destination and results in negative impacts on the local communities, the environment, and the visitors’ experience.

- Milano et al. [24] and García-Buades et al. [25], stating that overtourism is a state of an excessive growth of visitors, which leads to overcrowding in specific areas, while, in turn, renders residents the ‘victims’ of the impacts of tourist peaks that cause permanent changes to their lifestyles, limit their access to amenities and damage in general their well-being.

- Saveriades [26], highlighting also the social dimension and claiming that overtourism is associated with the maximum level of use (in terms of numbers and activities) that can be absorbed by a destination so that an acceptable decline in the quality of experience of visitors and acceptable adverse impact on the host community to be ensured.

- Goessling et al. [22], conceptualizing overtourism as a psychological reaction to tourist pressure, being the result of the damage of ‘place-residents’ interrelationships, which cause the shift of residents’ attitudes towards tourism.

- Capocchi et al. [9], pointing out the subjective nature of overtourism, where locals, tourists or both realize a destination as having that number of tourists that is: changing its character, affecting its authenticity, and leading to irritation and annoyance.

- Milano et al. [11], suggesting that overtourism can be grasped as a multifaceted and self-perpetuating system, placing priority to economic growth through mass tourism and gradually mobilizing a ‘visitor economy’ that leads to economic restructuring at the destination level.

- Alsharif et al. [27], pointing out that overtourism does not purely refer to the number of tourists in a certain destination, but actually features a destination’s state where a certain mismatch between tourist flows and the destination’s ecological, social, psychological, political or perceptual capacity is noticed.

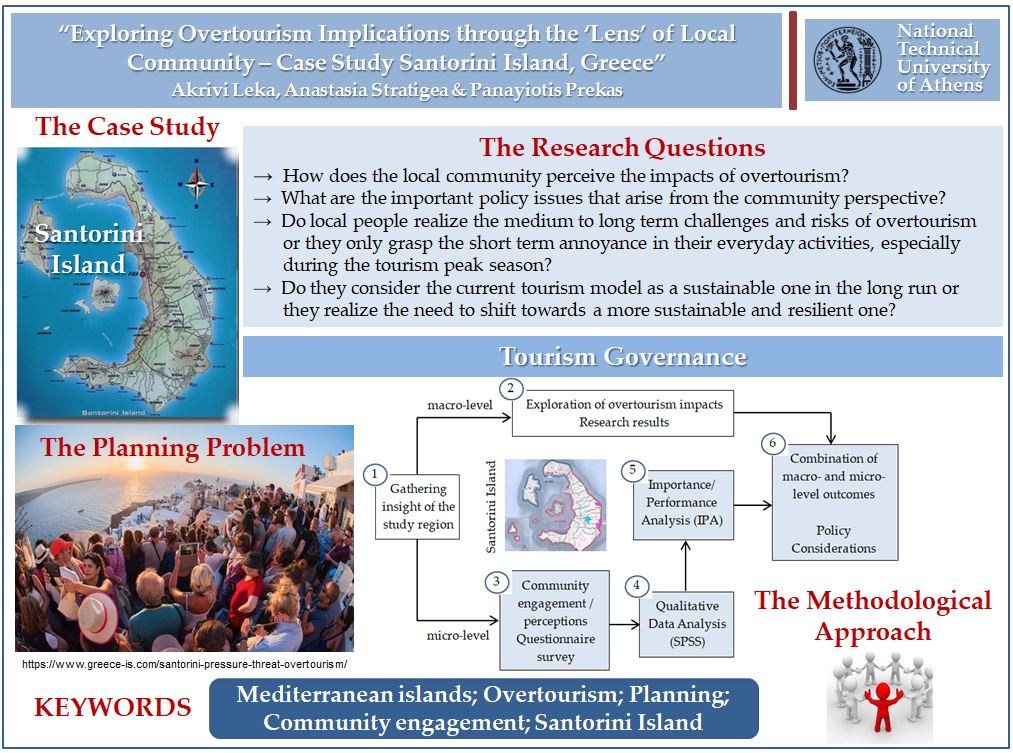

2. Materials and Methods

- How does the local community – micro-level – perceive the issue of overtourism and its impacts on the study area?

- What are the important policy issues that arise from the community perspective?

- Do local people realize the medium to long term challenges and risks of overtourism, as these are unveiled at the macro level or they grasp only the short term annoyance in their everyday activities, especially during the tourism peak season?

- Do they consider the current tourism model as a sustainable one in the long run or they realize the need to shift towards a more sustainable and resilient one?

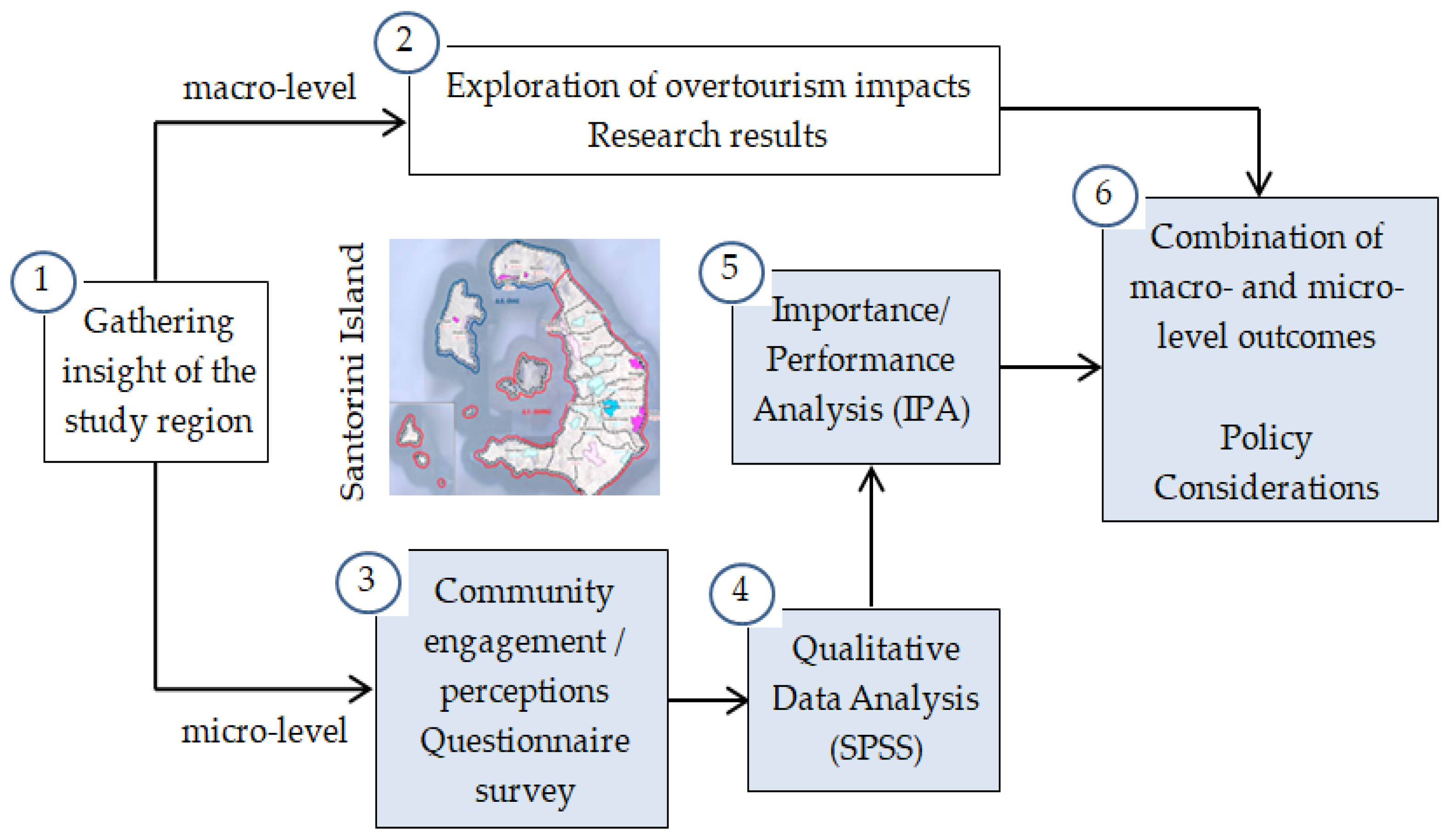

- The first step aims at gathering insights into the study region –macro-level – in order for the ground of research (environmental, cultural, economic, social, etc.) to be fully grasped (box 1).

- The second step relates to the assessment of overtourism impacts in environmental, economic, social, and spatial terms –macro-level – that is accomplished by use of a range of literature well-established indicators (box 2). Information related to this step is provided by previous work of authors on the topic [17] and features long term implications of overtourism at the island’s level.

- The third and fourth step aim at illuminating the impacts of overtourism, the way these are identified through the lens of the local community – micro-level. A questionnaire survey is carried out in this respect, while qualitative data collected are elaborated by use of the SPSS software (boxes 3 and 4).

- The fifth step is an effort to classify/prioritize overtourism repercussions as well as potential options for the future tourism profile of Santorini Island, as these were stated through the lens of questionnaire respondents – micro-level (box 5). Towards this end, an Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) is conducted.

- Finally, in the last step (box 6), an attempt to combine work carried out at the macro- and the micro-level is undertaken. Such an effort aimed at highlighting issues that need to be placed in the policy discourse, thus resulting in more evidence-based policy action for attaining mitigation of overtourism impacts in Santorini Island.

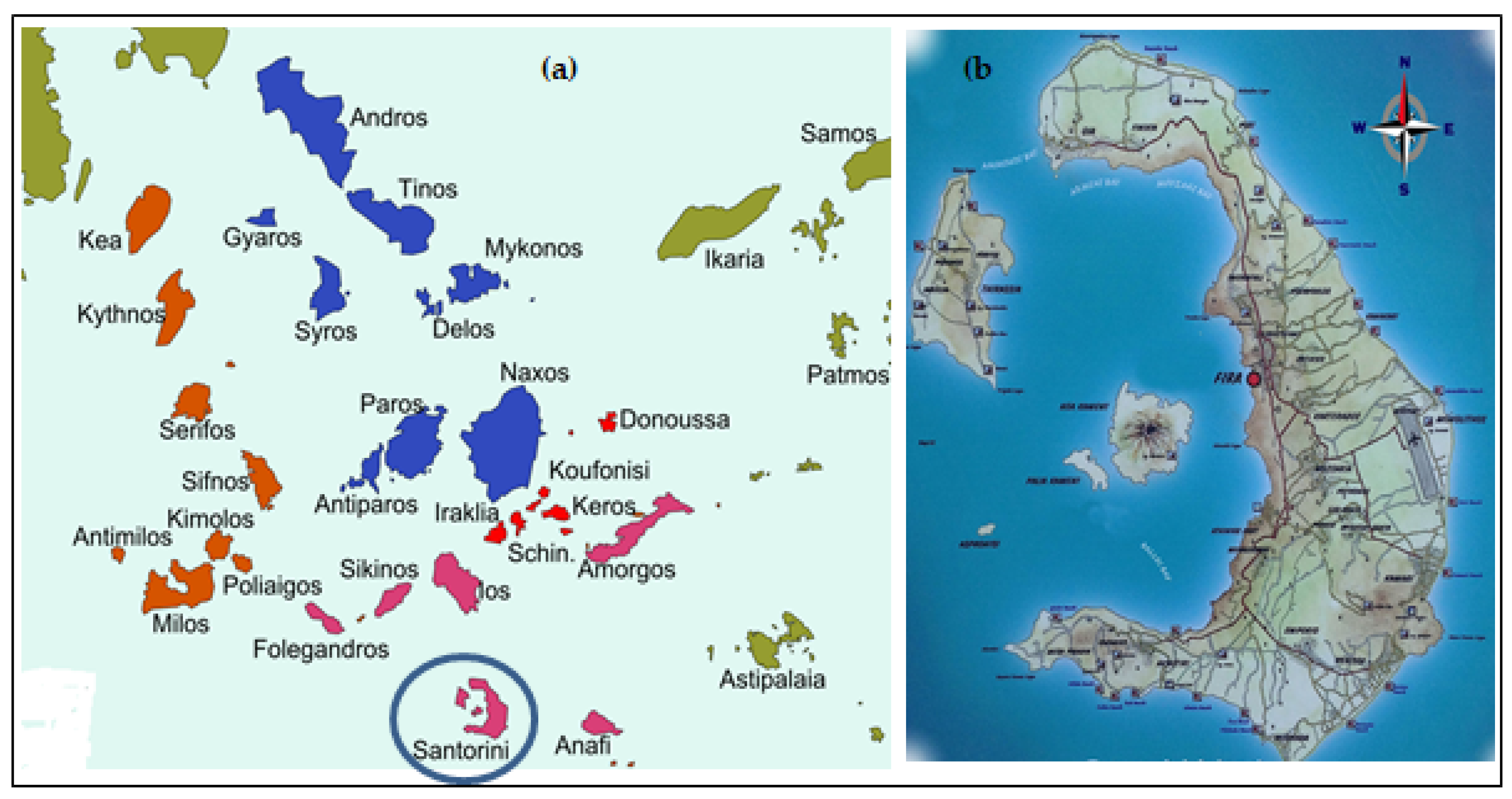

3. The Study Region

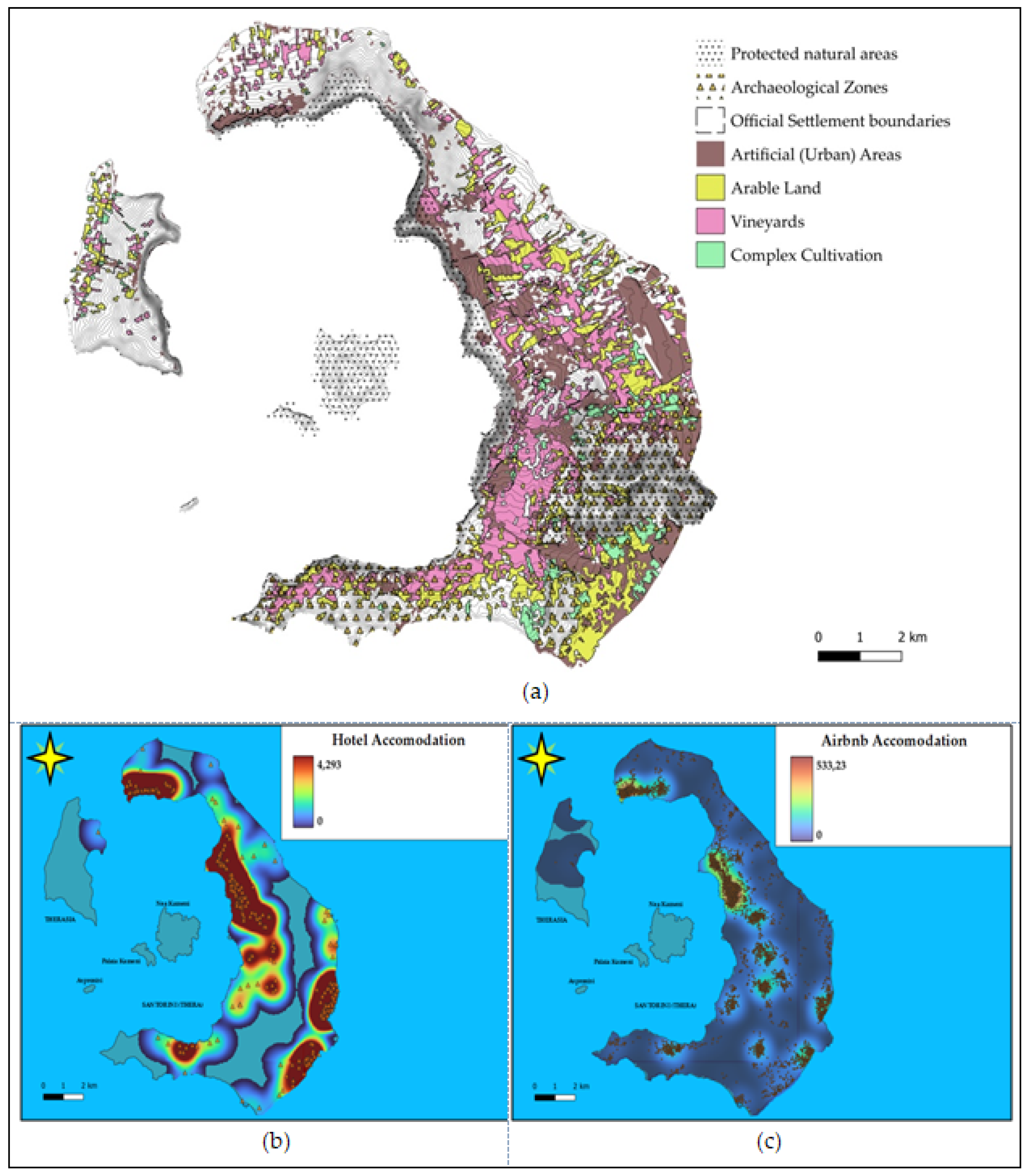

- Gradual shift of the local production identity from an agrarian society to a thriving service-oriented economy, mainly a ‘visitor economy’. This is due to the gradual prevalence of the tourism sector in the local economic profile; and is largely witnessed by the employment share of the tertiary sector that has shifted from 68.77% in 2001 to 90.66% in 2021, with the primary and secondary sectors demonstrating quite visible downturn signs through time. Taking into account the high vulnerability of the tourism sector, such a rather monocultural economic profile places medium to long term sustainability objectives and flourishing of the island at stake.

- Vegetation health and coverage, as captured by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), is rapidly decreasing, with a more rapid decrease pace being displayed in the central and southern part of the island. This part is also characterized by the shrinkage of agricultural land over the past three decades, and a significant percentage of wider agricultural zones being currently left uncultivated. Decrease in vegetation coverage in the central and southern part is interpreted by the fact that this constitutes the most heavily impacted island’s part by construction (artificial land, Figure 3a), followed by the northern part. In addition, large scale tourism infrastructure – i.e., 4* and 5* hotels of significant bed capacity, pools and other auxiliary spaces – covering large plots are located in the central and northern part of the island (Figure 3b and 3c).

- Vegetation degradation and loss. This, as close inspection of the NDVI loss shows, is considerably affecting the vineyards (Figure 3a), i.e. a very important primary resource for the production of the famous local wine of Santorini – a PDO product – and a milestone of the local agricultural tradition. This degradation is interpreted as a combined effect of climate change and drought, coupled with the sprawling of new constructions (or relevant preparatory works) taking place since 2017 in such fields. According to the results presented by Leka et al. [17], the central part of Santorini Island is very heavily affected by built-up areas, while significant pressure is currently identified in both the northern (Oia settlement) and the southern part and particularly the outstanding archaeological space of Akrotiri (Figure 3b and 3c).

- Quite noticeable loss of housing affordability. This is a critical overtourism repercussion, definitely affecting various groups of local population, while creating hostile feelings against the tourism phenomenon in the island. In quantitative terms, the mean rental price and the mean price for sale in Santorini Island is 56% and 100% higher respectively than the average for Cyclades and Attika Region.

- Airbnb accommodation expansion. The tourism supply in the Municipality of Thera in general and Santorini Island in particular is also further enriched by the rapid increase of Airbnb accommodation. In 2023, the number of Airbnb accommodations rises to 4783 units and 10750 beds [38], which sounds to be a quite large number, taking into consideration that the Athens metropolitan capital disposes 11314 Airbnb beds.

4. Overtourism Repercussions Through the Lens of the Locals – Methodology and Results

“… while Santorini’s white and blue cliff sides are undeniably picturesque, the experience is less enjoyable when visitors are forced to fight crowds at popular viewpoints” [39]

4.1. Structure of the Questionnaire Research

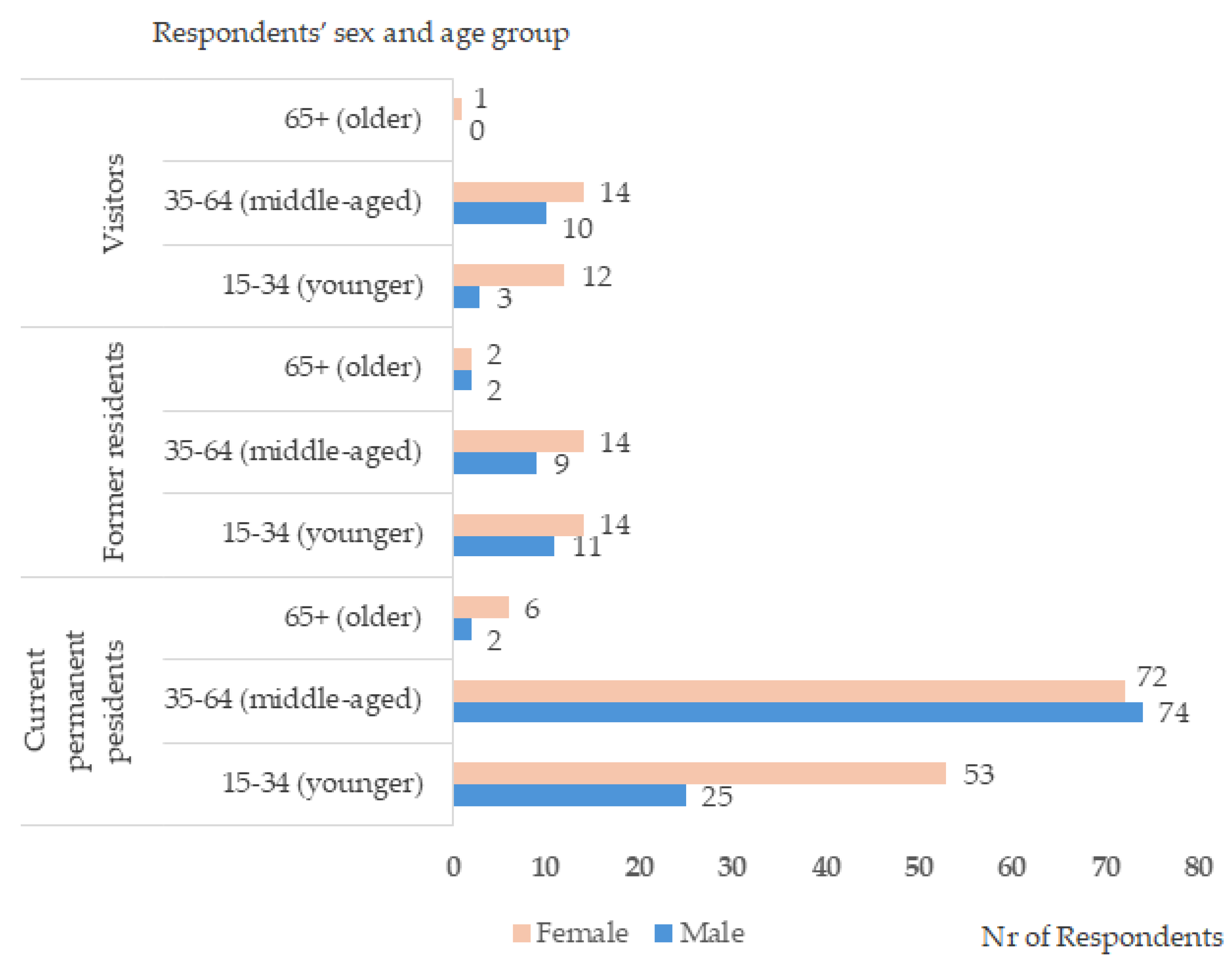

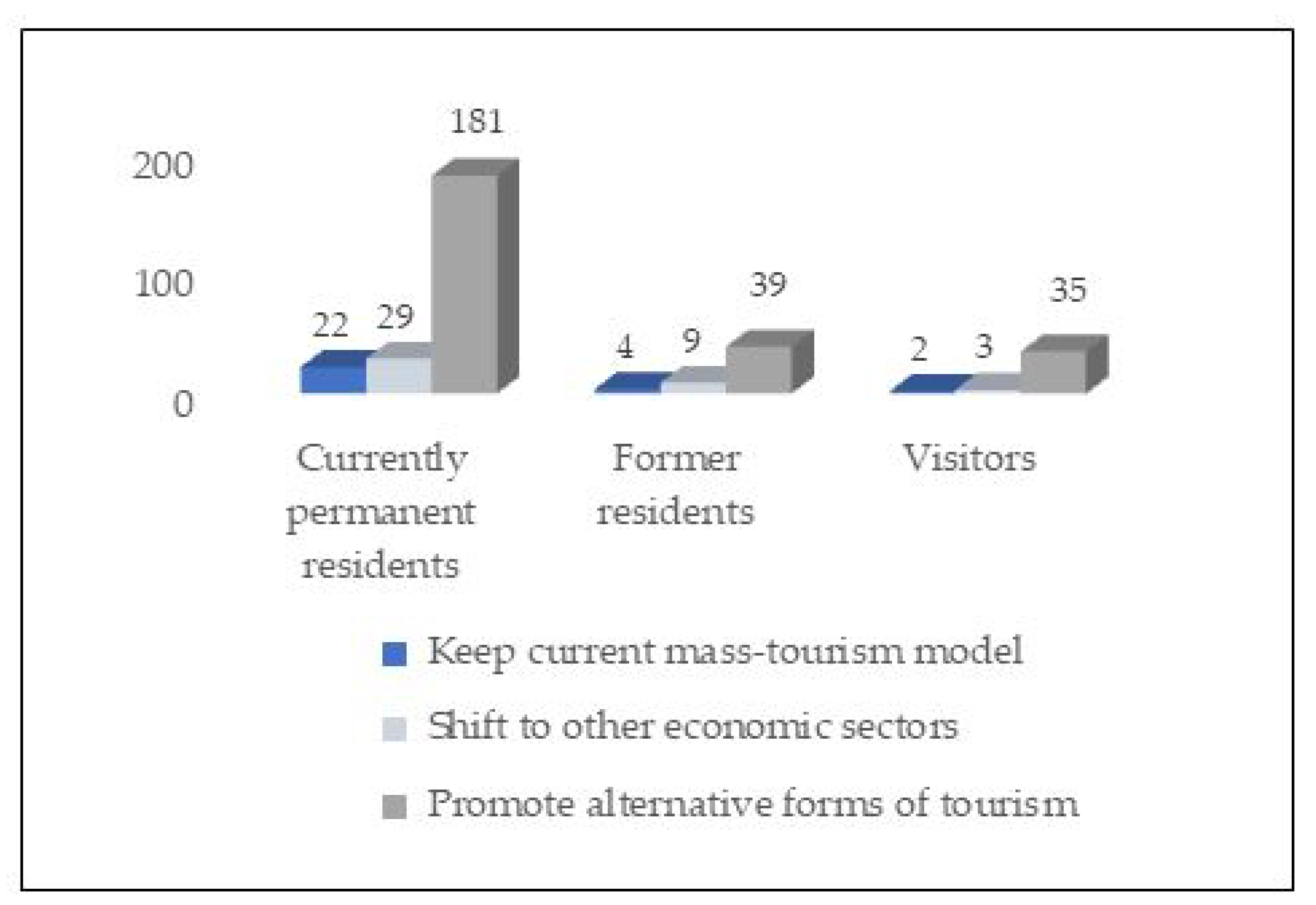

- 232 respondents (71,6%) were currently permanent municipal residents;

- 52 respondents (16,04%) were former residents, residing in the municipality of Thira for several years; and

- 40 respondents (12,34%) fall into the visitors’ group (tourists).

4.2. Statistical Analysis of Questionnaire Data

- Descriptive statistics: Frequencies and percentages were calculated for key demographic and contextual variables, including sex, age group, occupation, residency status (municipal zone and length of residence), as well as frequency of visit (for visitors).

- Comparative analysis: Cross-tabulations were performed to compare responses of the main subgroups (e.g., residents vs visitors; respondents related or non-related to tourism; sex and age groups).

- Visualization: Graphical representations were deployed to facilitate interpretation.

4.3. Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA)

- Importance was inferred from the number of times each item was selected (i.e., an issue ticked by many respondents was treated as more important) or, stated differently, it was defined as the proportion of respondents who identified a given attribute as a pressure or burden (in Question 16) or selected an attribute as important (in Question 18) [48,52].

- Performance reflects the current level of functioning of each attribute, whether based on respondents’ perceptions or emerging by system-generated evidence. In combination with Importance, it enables prioritization of management interventions. In the present study, the Performance scores were obtained from system-based measurements, capturing the observed operational performance of each attribute. These measures were standardized and rescaled to a continuous [0,1] interval to ensure comparability, allowing thus the paired analysis of Importance and Performance to highlight areas requiring management attention [45,47].

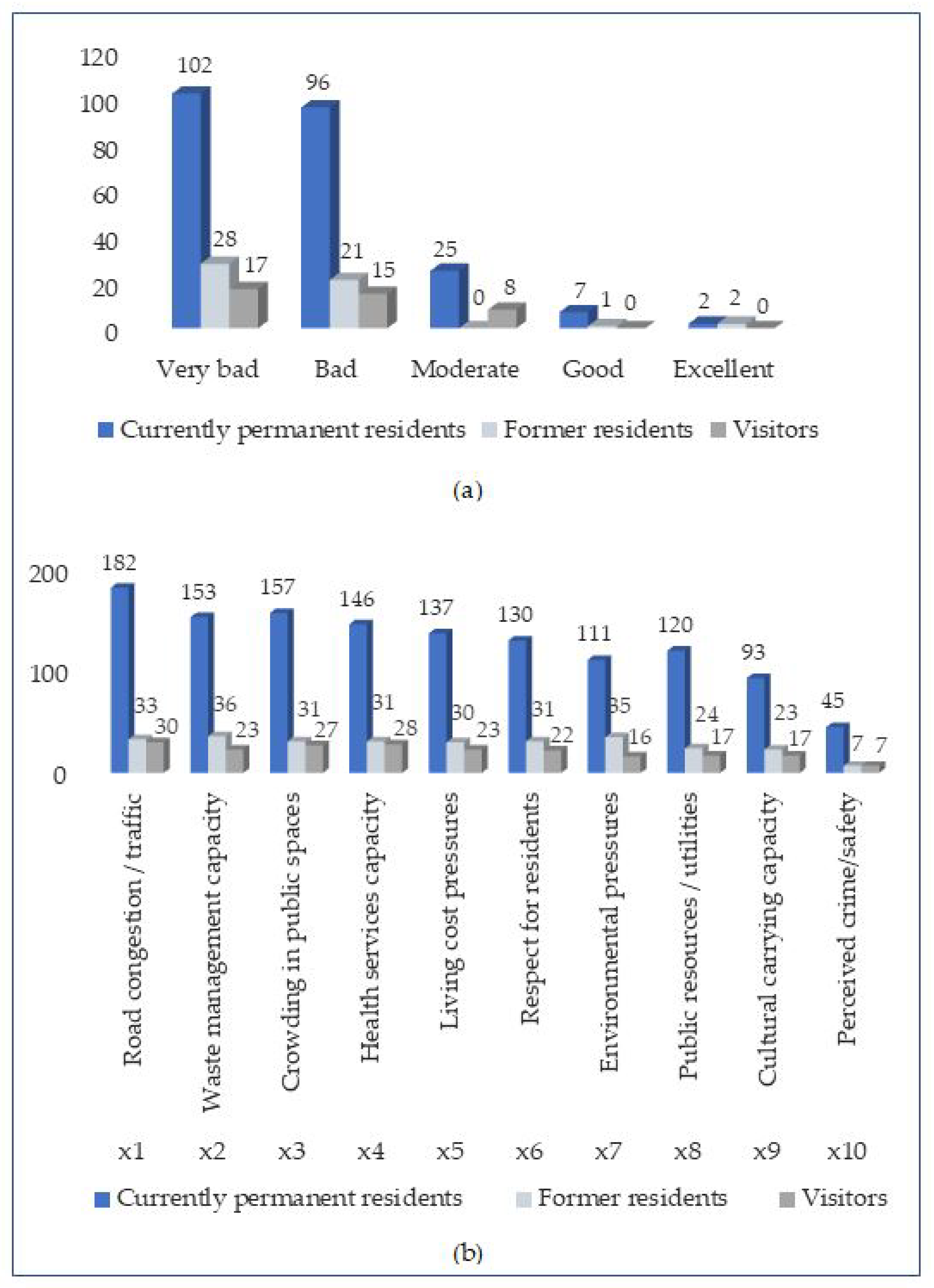

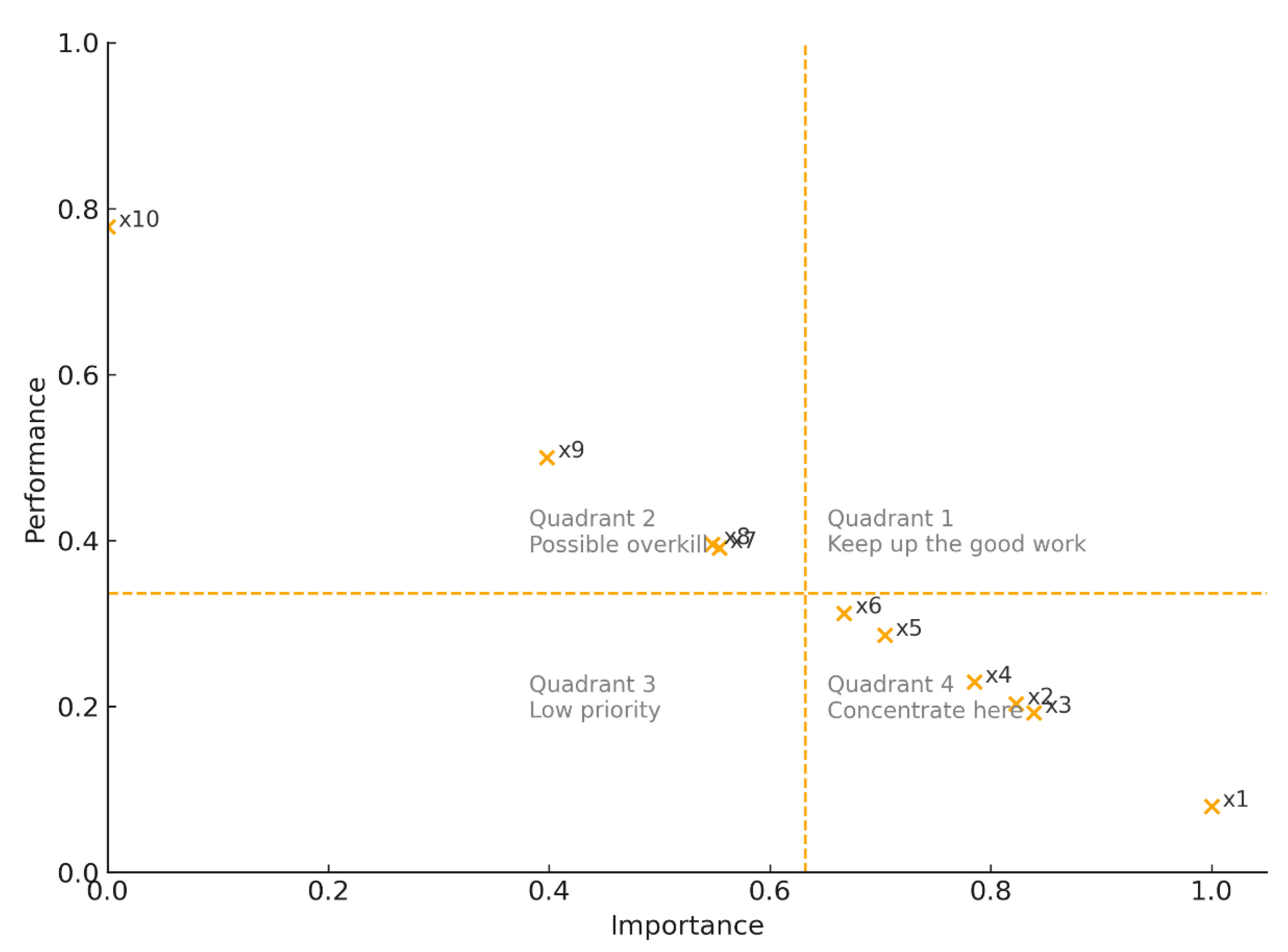

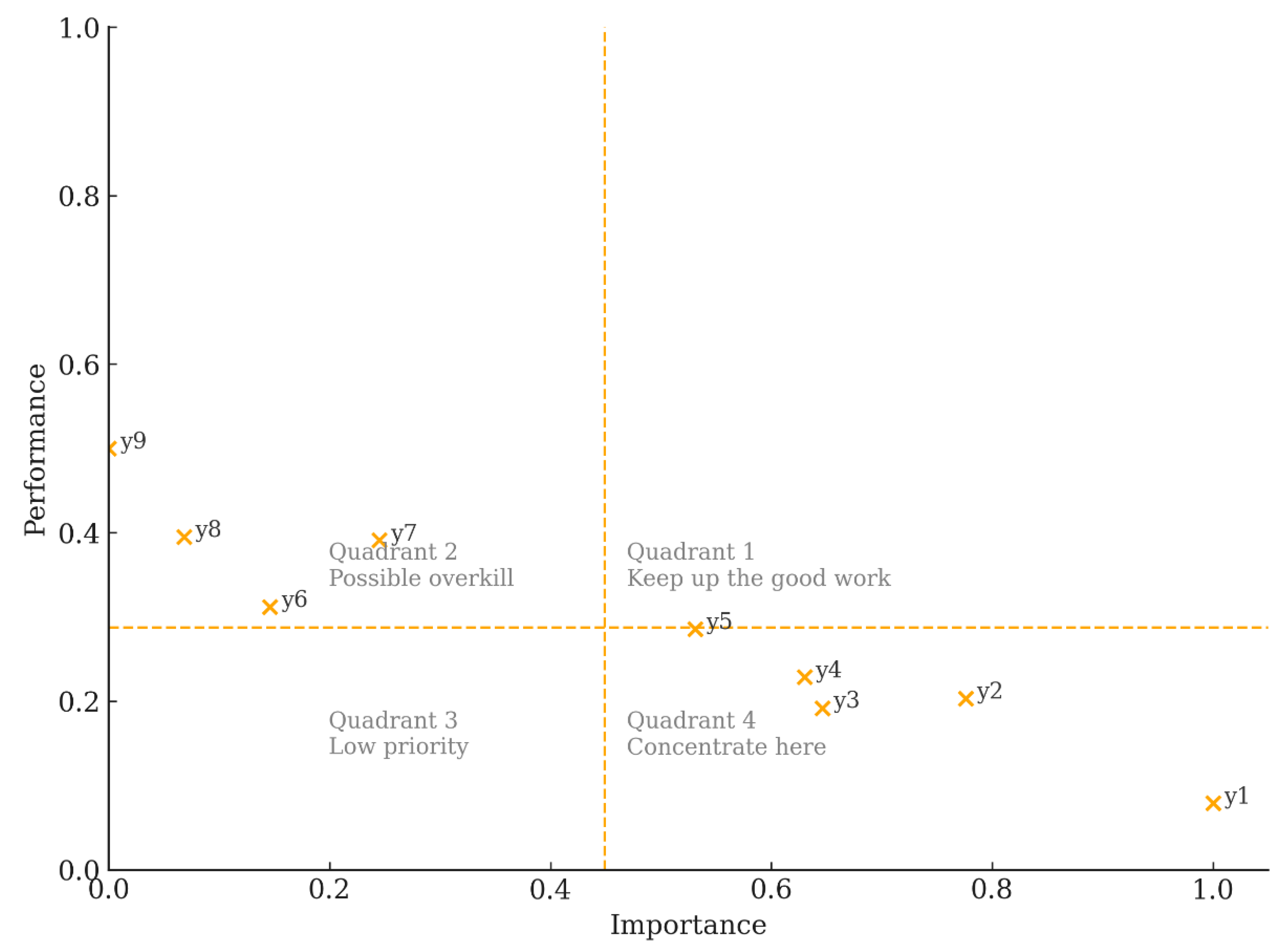

- Quadrant 4 (Concentrate here): As far as the impacts of overtourism are concerned (Question 16), this quadrant contains attributes that are rated high in importance. As such are considered the: ‘road congestion/traffic’, ‘waste management’, ‘crowding in public spaces’, ‘capacity of health services’, ‘pressure on living costs’ and ‘respect for residents’ (x1-x6 in Table 3) (Figure 10). This result is in alignment with findings at the macro level [17], where a rapid expansion of the built up environment in specific island’s spots is identified, establishing thus overcrowded and congested urban slots. In addition, work at the macro-level displayed that the costs of renting or buying a house are far more high that the ones in the rest of the Cyclades Island’ complex and the Athens metropolitan area. This pressure in the real estate market is also rated high in importance by the respondents. Speaking of the options available for featuring the future of tourism in Santorini Island (Question 18), the most preferable alternative tourism forms that are grounded in the abundance of the island’s local assets are ‘Volcano/Caldera geotourism’, ‘natural scenery’, ‘history/museum’s, and ‘local products/gastronomy’ (y1-y4 in Table 4) (Figure 11). Worth noticing is that in both cases (Questions 16 and 18) attributes that are rated as highly important by respondents are at the same time underperforming (i.e., display a low performance). This, in turn, highlights policy fields for action in order for a better performance to be attained.

- Quadrant 2 (Possible overkill): With respect to the impacts of overtourism (Question 16), this quadrant contains the attributes ‘environmental pressure’, ‘public resources / utilities’, ‘cultural carrying capacity’ and ‘perceived crime/safety’ (x7-x10) (Figure 10). Importance of all four attributes is rated rather lower by respondents, while these seem to be better performing. On the contrary, results at the macro-level stress the deterioration of environmental parameters and landscape quality through time due to the expansion of the built up space and tourism infrastructure. An effort to interpret this contradiction leads to the conclusion that lower priority attached to these attributes by respondents (micro-level) is the outcome of the lack of knowledge as to the long term environmental implications of the rising in intensity mass tourism model that are already taking place in Santorini Island as a whole (macro-level). Speaking of the key drivers of the tourism model in Question 18, ‘entertainment/nightlife’, ‘cruise-related offer’ and ‘sea/sun & beaches’ (y7-y9) (Figure 11) are gaining low importance by respondents. However, they display higher performance gains, being mainly the outcome of the emphasis placed on the mass tourism model, having at its heart the aforementioned attributes. Taking into consideration results at the macro-level, demonstrating that overestimation of these attributes in Santorini’s tourism model has led to violation of carrying capacity, further exploitation of these attributes in Santorini’s tourist model needs to be restrained.

- Quadrant 3 (Low priority): None of the x and y attributes (Table 3 and Table 4) falls into the category of attribute marked by both low importance and low performance. This implies that even the least important tourism pressures (Q16) and offerings (Q18) are performing at or above the estimated mean values for each one of the studied data sets.

5. Discussion

- Santorini Island as a whole is marked by significant environmental vulnerability, maximized in the archaeological zone of Akrotiri Thematic Area. However, building within protected areas currently reaches up to 12.7% of land.

- Vegetation health and coverage, as captured by NDVI, is recently rapidly decreasing, actually in a more rapid pace in the island’s Central and Southern part.

- Agricultural land, as captured by Corine Land Cover, is rapidly shrinking over the past three decades, rising to a 25% at the island’s level and above 40% in the Northern part as well as the Therasia land. Furthermore, a considerable part of the remaining agricultural land is currently left uncultivated, especially in the Central and Southern part.

- Large scale tourism infrastructure (4* and 5* hotels of large bed capacity, pools and other auxiliary spaces, covering large plots) is estimated to a significant coverage of total artificial land (12-18%), mainly located in the Northern and Central part. Such infrastructure is also dominant in the Akrotiri Thematic Area.

- Santorini Island overall presents a remarkable example of significant loss of housing affordability, where mean rental price and mean price for sale is 56% and 100% higher respectively than the average price for Cyclades and the Attika Region.

- Spatial redistribution of visitor flows and deployment of smart-tourism tools for effectively managing demand and mitigating congestion.

- Investments in critical infrastructure, particularly in waste management and health service provision, to safeguard the well-being of both residents and visitors, while reducing environmental and social strain.

- Rebalance of resource allocation by shifting part of resources dedicated to the promotion of over-performing attractions to interventions addressing systemic pressures, such as overcrowding and environmental stress.

- Monitor cultural integrity and cost-of-living trends to ensure that tourism growth does not erode local identity, community cohesion or housing affordability of local population.

6. Conclusions

“…. Of course, the answer is not to attack tourism. Everyone is a tourist at some point in his/her life. Rather, we have to regulate the sector, return to the traditions of local urban planning, and put the rights of residents before those of big businesses”.Ada Colau, Mayor of Barcelona 2015-2023 [59]

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO “Overtourism”? Understanding and managing urban tourism growth beyond perceptions. United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain; 2018, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284420070 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- UN Tourism (n.d.) Tourism in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development/small-islands-developing-states (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Leka, A.; Lagarias, A.; Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Development of a Tourism Carrying Capacity Index (TCCI) for sustainable management of coastal areas in Mediterranean Islands – Case Study Naxos, Greece. Ocean & Coastal Management 2022, 216, 105978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S.; Dodds, R. Sustainable Tourism in Island Destinations; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Coppin, F.; Guichard, V. Tourism as a tool for social and territorial cohesion - Exploring the innovative solutions developed by INCULTUM pilots. In Innovative Cultural Tourism in European Peripheries; Borowiecki, K. J., A. Fresa and Martín Civantos, J.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, B. A.; Falk, M. Residents’ perception of cultural heritage in terms of job creation and overtourism in Europe. Tourism Economics 2021, 27(6), 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clorruble, C. (2021), Overtourism and the policy agenda: from destinations to the European Union - Balancing growth and sustainability. College of Europe, Department of European Political and Governance Studies, Bruges Political Research Papers, 83 / 2021, https://www.coleurope.eu/sites/default/files/research-paper/wp83_corruble_0.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Santos-Rojo, C.; Llopis-Amorós, M.; García-García, J.M. Overtourism and sustainability: A bibliometric study (2018–2021). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 188, 122285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11(12), 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10(12), 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Russo, A.P. Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tourism Geographies 2024, 26(8), 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Stettler, J.; Crameri, U.; Eggli, F. Measuring overtourism. Indicators for overtourism: Challenges and opportunities. Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Hochschule Luzern, Institut für Tourismus Wirtschaft, ISBN: 978-3-033-07773-7, 2020, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344282239_Measuring_Overtourism_Indicators_for_overtourism_Challenges_and_opportunities (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Wall, G. From carrying capacity to overtourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review 2020, 75(1), 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemla, M. Overtourism and local political debate: Is the over-touristification of cities being observed through a broken lens? Entrepreneurship – Education 2024, 20(1), 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; Mitas, O.; Moretti, S.; Nawijn, J.; Papp, B.; Postma, A. Research for TRAN Committee - Overtourism: Impact and possible policy responses, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, 2018, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/629184/IPOL_STU(2018)629184_EN.pdf (accessed on 26 SJuly2025).

- Buitrago, E.M.; Yñiguez, R. Measuring overtourism: A necessary tool for landscape planning. Land 2021, 10(9), 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, A., Lagarias, A., Stratigea, A., Prekas, P. A methodological framework for assessing overtourism in insular territories—Case study of Santorini Island, Greece. In A. Skopeliti, A. Stratigea, V. Krassanakis, A. Lagarias (Eds.), Geographic Information Systems and Cartography for a Sustainable World, Special Issue, International Journal of Geo-Information 2025, 14, 106, https://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/14/3/106.

- Mihalic, T. Conceptualizing overtourism: A sustainability approach. Annals of Tourism Research 2020, 84, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar, V. G.; Thanh, T. V. Between overtourism and under- tourism: Impacts, implications, and probable solutions. In Overtourism: Causes, Implications and Solutions; Séraphin, H., Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T.; Kuščer, K. Can overtourism be managed? Destination management factors affecting residents’ irritation and quality of life. Tourism Review 2021, 77(1), 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B. A.; Falk, M. Residents’ perception of cultural heritage in terms of job creation and overtourism in Europe. Tourism Economics 2021, 27(6), 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessling, S.; McCabe, S.; Chen, N. A socio-psychological conceptualisation of overtourism. Annals of Tourism Research 2020, 84, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vourdoubas, J. Evaluation of overtourism in the island of Crete, Greece. European Journal of Applied Science, Engineering and Technology 2024, 2(6), 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J. M.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: an evolving phenomenon. In Overtourism: Excesses, discontents and measures in travel and tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J. M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- García-Buades, M. E.; García-Sastre, M. A.; Alemany-Hormaeche, M. Effects of overtourism, local government, and tourist behavior on residents’ perceptions in Alcúdia (Majorca, Spain). Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2022, 39, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveriades, A. Establishing the social tourism carrying capacity for the tourist resorts of the east coast of the Republic of Cyprus. Tourism Management 2000, 21(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Mohd Isa, S.; Md Salleh, N.Z.; Abd Aziz, N.; Abdul Murad, S.M. Exploring the nexus of over-tourism: Causes, consequences, and mitigation strategies. J. Tour. Serv. 2025, 16, 99–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B. A. , Falk, M., & Savioli, M. Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Europe. Current Issues in Tourism 2020, 23, 1737–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is ‘overtourism’ a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23(18), 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Overtourism: Causes, symptoms and treatment. Tourismus Wissen – Quarterly 2019, 110–114, https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/TWG16-Goodwin.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Caro-Carretero, R., & Monroy-Rodríguez, S. Residents’ perceptions of tourism and sustainable tourism management: Planning to prevent future problems in destination management - The case of Cáceres, Spain. Cogent Social Sciences 2025, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cordero, E.; Maldonado-Lopez, B.; Ledesma-Chaves, P. Metaverse and overtourism: Positive and negative impacts of tourism development on local residents. Journal of Management Development 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaprak, B.; Okkiran, S.; Vezali, E. Reframing Sustainability in the Context of Overtourism: A Comparative Five-Dimensional Resident-Centered Model in Athens and Istanbul. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N. The major holiday hotspots cracking down on overtourism. Independent 2025, Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/sustainable-travel/overtourism-countries-tax-where-b2747853.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Forbes platform Beautiful Greek Santorini Island, Another European Paradise Confronting Overtourism in Photos. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ceciliarodriguez/2024/09/01/beautiful-greek-santorini-island-another-european-paradise-lost-to-overtourism-in-photos/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Airbnb accommodation. Available online: https://bfortune.opendatasoft.com/explore/dataset/Airbnb-listings/export/?disjunctive.neighbourhood&disjunctive.column_10&disjunctive.city&q=santorini (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Brajcich, K. What is overtourism and why is it a problem? Sustainable Travel International, 2024, https://sustainabletravel.org/what-is-overtourism/.

- Alrwajfah, M.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R. Residents’ perceptions and satisfaction toward tourism development: A case study of Petra region, Jordan. Sustainability 2019, 11(7), 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Tourism governance for reaching sustainability objectives in insular territories – Case study Dodecanese Islands’ complex, Greece. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2023, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Part VII, Vol. 14110; Gervasi, O. et al., Eds.; Springer, Cham, Print ISBN 978-3-031-37122-6, 2023; pp. 289–306. [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, J.; Hernández, A. Citizen engagement versus tourism-phobia: The role of citizens in a country’s brand. Mexico, 2017, Special Report, https://ideas.llorenteycuenca.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/09/170905_DI_Informe_Marca_Pa%C3%ADs_ENG.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Bateman, J. Santorini under pressure: The threat of overtourism, 2019, Available online: https://www.greece-is.com/santorini-pressure-threat-overtourism/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- O'Toole, L. Beautiful European Island under pressure where even tourists complain about the tourists, Daily Express, 2024, Available online: https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1910789/santorini-greece-overtourism-tourists-news (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Martilla, J. A.; James, J. C. Importance–Performance Analysis. Journal of Marketing 1977, 41(1), 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalo, J.; Varela, J.; Manzano, V. Importance values for Importance–Performance Analysis: A formula for spreading out values derived from preference rankings. Journal of Business Research 2007, 60(2), 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, I. Importance–Performance Analysis: A valid management tool? Tourism Management 2015, 48, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H. Revisiting importance–performance analysis. Tourism Management 2001, 22(6), 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J., & Prebežac, D. Rethinking the importance grid as a research tool for quality managers. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 1006, 22(9), 993–1006. [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J., Prebežac, D., & Dabić, M. Importance-performance analysis: Common misuse of a popular technique. International Journal of Market Research 2016, 58(6), 775–778. [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, E.; Nash, R. A critical evaluation of importance–performance analysis. Tourism Management 2013, 35, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I. K. W.; Hitchcock, M.; Yang, T. Importance–performance analysis in tourism: A framework for researchers. Tourism Management 2015, 48, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresserras, J.J. (n.d.). Tourism in the Mediterranean: Trends and Perspectives. Economy and Territory / Productive Structure and Labour Market, European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMed), https://www.iemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Tourism-in-the-Mediterranean-Trends-and-Perspectives.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Lagarias, A.; Stratigea, A.; Theodora, Y. Overtourism as an emerging threat for sustainable island communities – Exploring indicative examples from the South Aegean Region, Greece. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2023 Workshops. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Part VII, Vol. 14110; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha. A. M. A. C., Garau, Ch., Scorza, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 404–421. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Egger, R. Tourist experiences at overcrowded attractions: A text analytics approach. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, Proceedings of the ENTER 2021 eTourism Conference, Virtual Conference, January 19–22; Wörndl, W., Koo, C., Stienmetz, L.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 231–243. [CrossRef]

- Donaire, A.J.; Galí, N.; Coromina, L. Evaluating tourism scenarios within the limit of acceptable change framework in Barcelona. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2024, 5(2), 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, N. and Serrat, R. A methodological proposal for public responses to overtourism and its integration in urban destinations’ policies. In Sostenibilidad Turística: overtourism vs undertourism; Pons, G.X., Blanco-Romero, A., Navalón-García, R, Troitiño-Torralba, L., Blázquez-Salom, M., Eds.; Mon. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears 2020, 31, 265–281, https://bshnb.shnb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Sostenibilidad-Turistica-TOT.pdf,.

- Responsible tourism, https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/overtourism-solutions/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M.; Cañada, E.; Murray Mas, I.; Sekulova, F. Pathways to post-capitalist tourism. Tourism Geographies 2021, 25(2–3), 707–728. [CrossRef]

- Windegger, F. Addressing the Limits to Growth in Tourism - A Degrowth Perspective. In From Overtourism to Sustainability Governance - A New Tourism Era; Pechlaner, H., Innerhofer, E., Philipp, J., Eds.; pp. 137–153, Routledge, London, UK, 2024; eBook. ISBN 9781003365815.

- Dale, G. The growth paradigm: A critique. International Socialism – A quarterly review of socialist theory 2012, 134, 2, https://isj.org.uk/the-growth-paradigm-a-critique/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Asara, V.; Otero, I.; Demaria, F.; Corbera, E. Socially sustainable degrowth as a social-ecological transformation: Repoliticizing sustainability. Sustainability Science 2015, 10, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Milano, C. Urban tourism studies: A transversal research agenda. Tourism, Culture & Communication 2024, 24(4), 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, D.; Koens, K. Don't write cheques you cannot cash - Challenges and struggles with participatory governance. In From Overtourism to Sustainability Governance - A New Tourism Era; Pechlaner, H., Innerhofer, E. and Philipp, J., Eds.; Routledge, London, UK, 2024; pp. 227–240.

| Thematic Groups | Questions | Type of data collected |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics / Profiling of Respondents | Q1–Q10 | Sex and age group; occupation; residency status (currently permanent and former residents); residency length (currently permanent and former residents); frequency of visit (visitors); municipal zone of residence (permanent residents); relation to the tourism-sector (employee or owner of tourism business). |

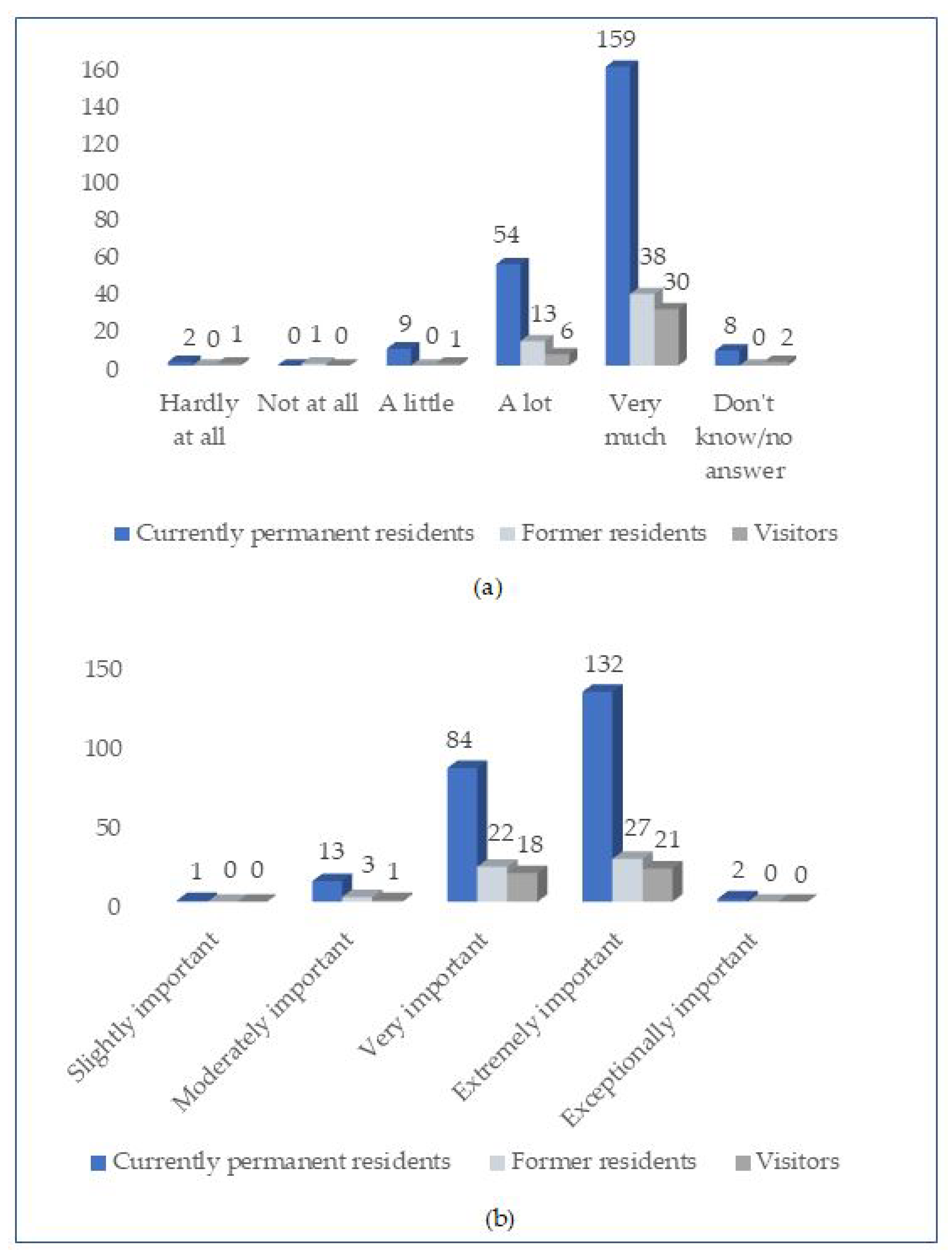

| Tourism Intensity & Seasonality | Q11–Q13 | Perceived change in tourism activity over the last decade; preferred time to visit; season preference. |

| Developmental Profile & Daily Life | Q14–Q15 | Perceived importance of tourism in the developmental profile of Santorini Island; quality of everyday life during peak tourist season. |

| Pressures/Problems that are due to (over)tourism | Q16 | Residents: congestion; waste management capacity; crowding; health infrastructure; living costs; environmental stress; concern for local identity; |

| Q17 | Tourists: intention to visit (tourist experience / attractiveness of destination). | |

| Policy priorities towards a sustainable tourist model | Q18 | Geotourism (Volcano/Caldera); natural tourism; heritage/archaeological tourism; gastronomy tourism; architectural tourism; religious tourism; entertainment/nightlife; maritime / cruise tourism. |

| Governance & Participation | Q19–Q20 | Views on current mass-tourism model vs. alternative/low-impact forms; willingness to participate in local decision-making. |

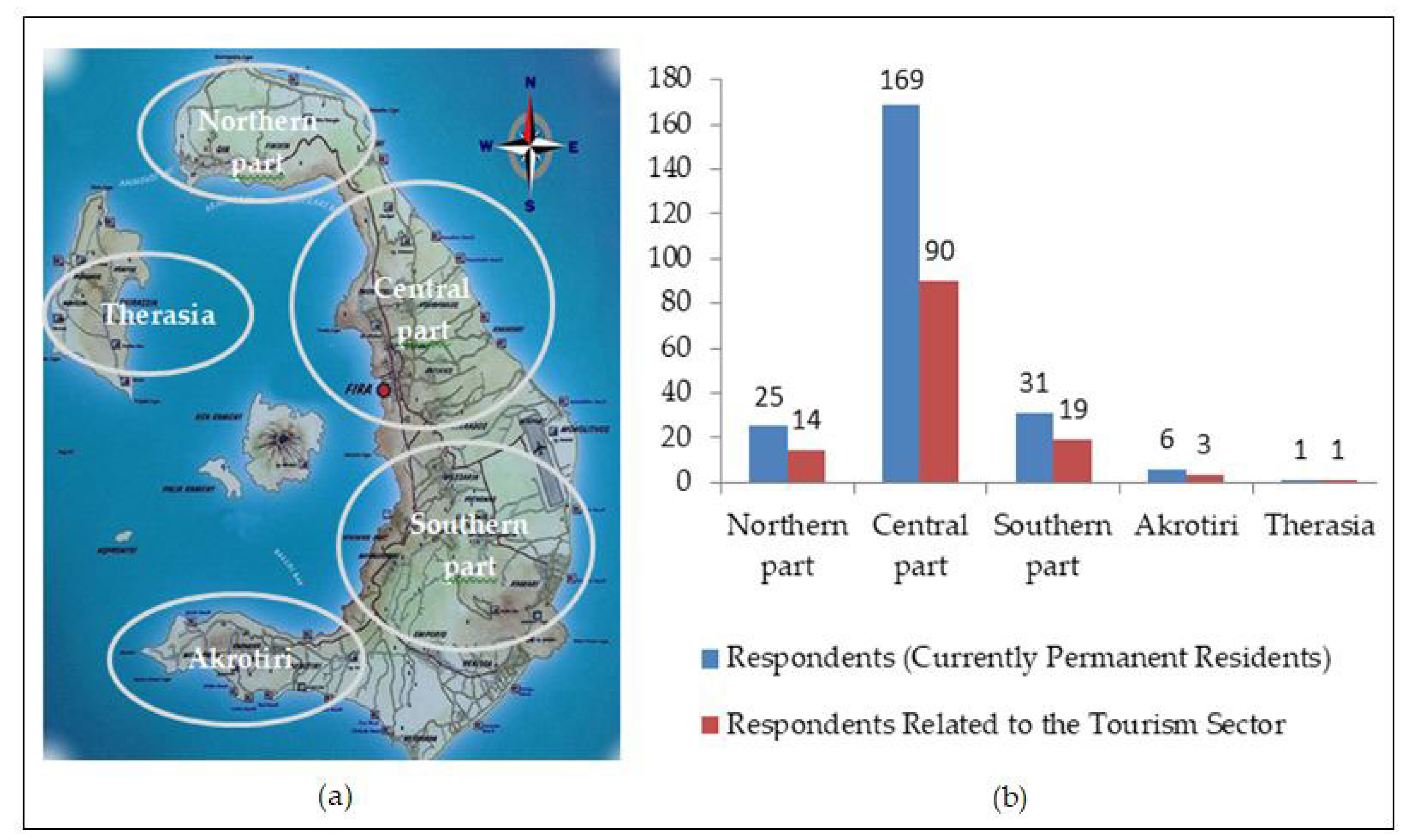

| Thematic Area | Municipal Zone | Spatial distribution of permanent residents * Nr / (%) |

Spatial distribution of permanent residents related to the tourism sector ** Nr / (%) |

| Northern part | Oia, Imrovigli, Vourvoulos | 25 / (10.8) | 14 / (11.0) |

| Central part | Messaria, Thira, Karterados, Pyrgos,Vothonas, Exo Gonia, Episkopi Gonias | 169 / (72.8) | 90 / (70.9) |

| Southern part | Emporeio, Megalochori | 31 / (13.4) | 19 / (15.0) |

| Akrotiri | Akrotiri | 6 / (2.6) | 3 / (2.4) |

| Therasia | Therasia | 1 / (0.4) | 1 / (0.7) |

| Attribute | Label | Mean Importance | Mean Performance |

| x1 | Road congestion / traffic | 1 | 0.079 |

| x2 | Waste management capacity | 0.823 | 0.203 |

| x3 | Crowding in public spaces | 0.839 | 0.192 |

| x4 | Health services capacity | 0.785 | 0.229 |

| x5 | Living cost pressures | 0.704 | 0.286 |

| x6 | Respect for residents | 0.667 | 0.312 |

| x7 | Environmental pressures | 0.554 | 0.391 |

| x8 | Public resources / utilities | 0.548 | 0.395 |

| x9 | Cultural carrying capacity | 0.398 | 0.5 |

| x10 | Perceived crime/safety | 0 | 0.778 |

| Attribute | Label | Mean Importance | Mean Performance |

| y1 | Volcano/Caldera geotourism | 1 | 0.079 |

| y2 | Natural Scenery | 0.776 | 0.203 |

| y3 | History/museums | 0.646 | 0.192 |

| y4 | Local products/gastronomy | 0.63 | 0.229 |

| y5 | Architecture/settlements | 0.531 | 0.286 |

| y6 | Churches/monasteries | 0.146 | 0.312 |

| y7 | Entertainment/nightlife | 0.245 | 0.391 |

| y8 | Cruise-related offer | 0.068 | 0.395 |

| y9 | Sea/sun & beaches | 0 | 0.500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).