Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Reporting

2.2. Research Question and Framework

- Population (P): Patients receiving dental implants, or implant models used in in vitro studies.

- Concept (C): Use of PEEK (polyetheretherketone) ISBs for digital impression procedures and intraoral scanning.

- Context (C): Implant dentistry workflows, including in vitro studies, clinical studies (prospective or retrospective), and technical reports.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

-

Inclusion criteria:

- ○

- Studies evaluating PEEK ISBs in dental implantology.

- ○

- Study types include in vitro studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies (both prospective and retrospective), and technical reports.

- ○

- Publications from peer-reviewed journals.

- ○

- Language: English.

- ○

- Publication period: 2010–present.

-

Exclusion criteria:

- ○

- Studies focusing exclusively on ISBs made of other materials (e.g., titanium, resin, hybrid) without including PEEK.

- ○

- Case reports, reviews, editorials, expert opinions, and conference abstracts without full text.

- ○

- Animal studies.

2.4. Search Strategy

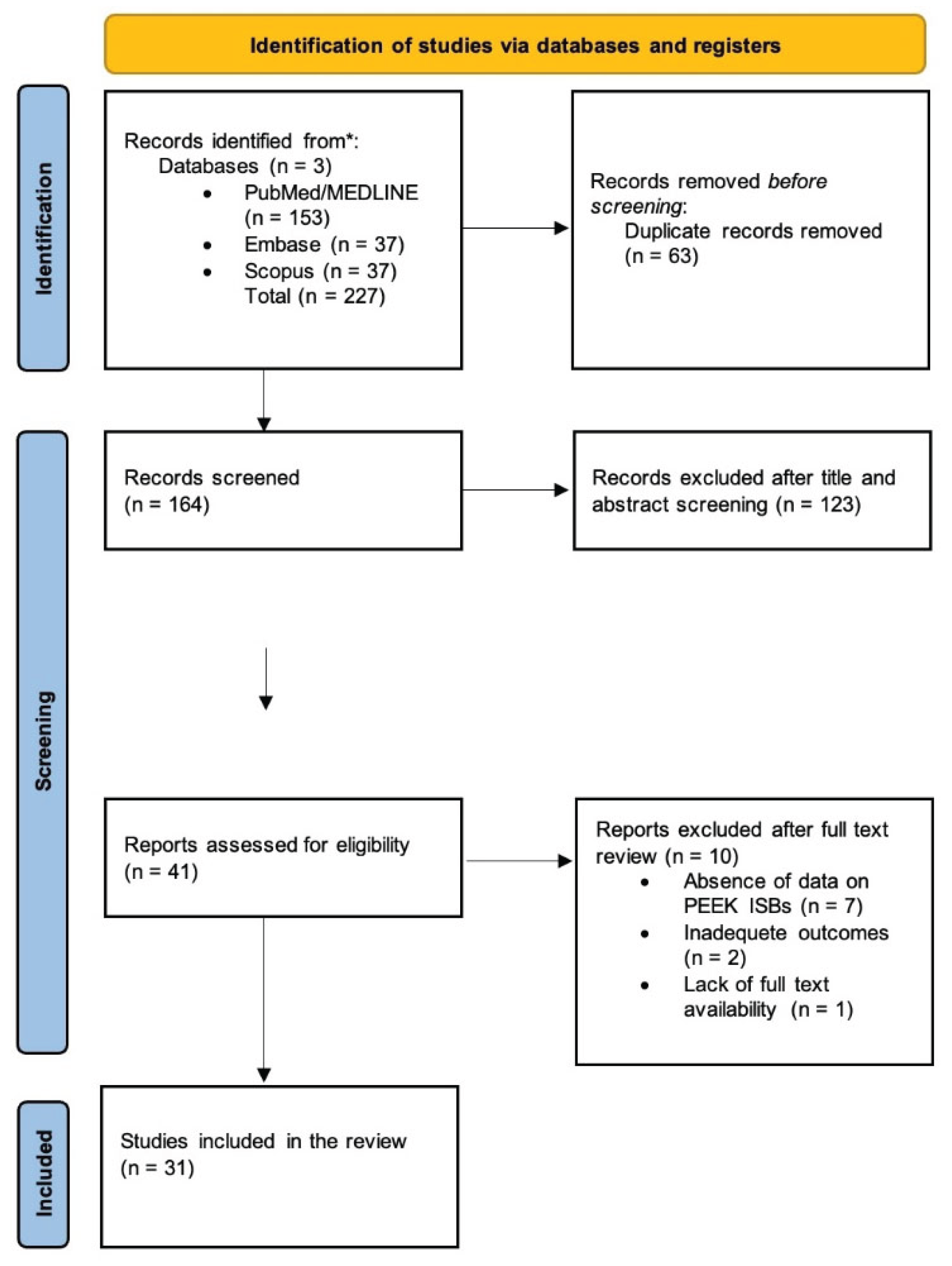

2.5. Selection Process

- Stage 1: Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (IR, AP).

- Stage 2: Full-texts of potentially relevant articles were assessed against eligibility criteria.

- Disagreements: Resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (CR).

2.6. Data Extraction

- Author(s)

- Year

- Study design (in vitro, RCT, observational study)

- Jaw/Region

- Type of edentulism

- No of implants

- Implant system/connection

- Scan body material

- Control group

- Type of intraoral/lab scanner used

- Metrics

- Measurement method for accuracy (e.g., trueness, precision, superimposition analysis)

- Key outcomes related to PEEK scan bodies

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

| Author | Study type | Sample/Jaw/Region | Type of Edentulism | No of implants | Scan body material(s) |

Method | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32] Stimmelmayr, et al, 2012 | In vitro | Mandibular polymer model, stone cast | Full | 4 implants | PEEK | STL superimposition; discrepancies measured at 21 points on each scan body; | Mean discrepancy of scanbodies: 39 μm (±58) on original implants vs. 11 μm (±17) on lab analogues (statistically significant, p < 0.05) Systematic error is lower for stone models (5 μm) than polymer models (13 μm) |

| 33] Giménez-Gonzalez, et al, 2015 | In vitro | Maxilla model | Full | 6 implants | PEEK | CMM reference, superimposition analysis, | PEEK scan bodies provided deviations within acceptable limits (<70 μm). Accuracy was influenced by scanbody visibility Implant angulation had no effect. |

| [34] Papaspyridakos, et al, 2015 | In vitro | Mandible | Full, | 5 implants | PEEK | STL superimposition with best-fit alignment | Digital impressions were as accurate as splinted conventional impressions and more accurate than non-splinted ones. Implant angulation up to 15° did not affect accuracy. |

| [35] Amin, et al, 2016 | In vitro | Mandible | Full | 5 implant analogs | PEEK SB | STL superimposition | Digital impressions were more accurate than conventional impressions. |

| [19] Arcuri, et al, 2020 | In vitro | Maxillary PMMA model | Full | 6 implant analogs | PEEK, Ti, PEEK–Ti base | Superimposition with Geomagic Studio; | PEEK scan bodies provided the highest accuracy (DASS ≈ 55 μm; angular deviation ≈ 0.64°). Titanium performed moderately (≈99 μm). The PEEK–titanium hybrid showed the worst accuracy (≈approximately 196 μm). Implant position influenced deviations; operator had no effect. |

| [36] Arcuri, et al, 2022 |

In vitro | Mandibular PMMA model | Full | 4 implant analogs | PEEK | Alignment of STL test files to reference (Geomagic Studio 12); deviations analyzed with HyperCAD-S; | ISB wear negatively influenced accuracy, particularly for the angulated implant at position 3.6 (17° distal) (p < 0.0001) Primary deviation sources were Y-axis (lateral) and X-axis (longitudinal) shifts |

| [37] Azevedo, et al, 2024 | In vitro | Mandibular gypsum cast | Full | 6 implant analogs | PEEK, Plasma-coated medical titanium | STL superimposition with Geomagic Control X (best-fit alignment, ISBs cut at scan region); | Significant interaction between ISB material and IOS. Plasma-coated titanium ISBs generally had higher trueness (33 ± 6 µm) and precision (32 ± 9 µm) than PEEK ISBs (trueness 47 ± 27 µm; precision 40 ± 15 µm). Primescan showed the highest accuracy regardless of ISB material. TRIOS 4 had the lowest accuracy with PEEK ISBs, while Virtuo Vivo had the lowest accuracy with titanium ISBs. Both materials produced deviations < 120 µm, within clinical acceptability |

| [38] Costa Santos, et al, 2025 | In vitro | Two 3d printed mandibular models | Full | 10 implant analogs each | PEEK, Titanium | SBs subjected to autoclave cycles (134°C, 40 min) with 10 Ncm torque screwing; STL superimposition (Geomagic Control) for surface deviations; qualitative marginal fit under optical microscope (40×) at 4 surfaces; | PEEK SBs showed greater deformation than titanium SBs, especially at the implant level after 100 cycles (≈50 µm vs ≈20 µm), Despite deformation, all deviations remained <50 µm (clinically acceptable). Implant-level SBs are more affected than abutment-level. Microscopic analysis: 100% of SB faces classified as “clinically adapted”, even after 100 cycles |

| [39] Diker, et al, 2023 | In vitro | Epoxy resin sleeves | Not applicable | 2 implants | PEEK, Titanium | Torque applied at 5 → 10 → 15 Ncm using digital torque device; displacements measured via 3D DIC before and after 25 autoclave sterilization cycles; | PEEK SBs displaced more than Ti SBs on all axes (p < 0.05), especially at 15 Ncm and after sterilization. Sterilization generally increased PEEK SB displacement (e.g., x-axis: 40–71 µm after autoclaving vs. 14–39 µm before). Ti SBs showed minimal changes (<5 µm) regardless of torque/sterilization Recommend ≤10 Ncm torque for PEEK SBs, avoid multiple sterilizations, and consider Ti SBs for greater stability |

| [40] Grande, et al, 2025 | In vitro | Maxillary titanium model | Full | No implants, only multi-unit | ISB sandblasted titanium, PEEK body with titanium base | Two scan strategies—Zig-zag (ZZ) and One-shot (OS); superimposition by fiducials; automatic centroid/axis computation (MATLAB); | ISB-AQ (Ti) showed the highest trueness, outperforming One-shot (Ti) and PEEK/Ti-base. TRIOS had the best accuracy overall; scan strategy did not affect trueness generally (except Primescan, where OS > ZZ). PEEK/Ti-base produced the most significant deviations among the three ISBs. |

| [41] Hashemi, et al, 2023 | In vitro | 2 acrylic resin maxillary models | Partial | 2 implant analogs | Titanium PEEK scan | Each scan body type was attached (10 Ncm torque), scanned, removed, and autoclaved nine times at 134°C for 10 min. STL files analyzed in GOM software (ATOS Core 80); scans superimposed with best-fit alignment; reference cube defined 3D coordinates. | Inter-implant distance variation was significantly greater in titanium scan bodies (0.032 ± 0.016 mm) than PEEK (0.011 ± 0.012 mm) (p = 0.006). Diameter change was greater in PEEK (0.066 ± 0.014 mm) than titanium (0.029 ± 0.020 mm). No significant difference in ΔR (0.069 ± 0.052 mm vs 0.080 ± 0.044 mm; ). PEEK scan bodies performed better after 10 reuse/sterilization cycles, maintaining more stable inter-implant distances. |

| [42] Kato, et al, 2022 | In vitro | 2 stone casts | Not applicable | 2 implant bodies and 2 implant analogs | PEEK scan bodies | Autoclave at 135°C for 3 min; torque 15 Ncm; 10 repeated connection/disconnection cycles; STL analysis using PolyWorks Inspector (InnovMetric, Canada); SEM for surface texture; | Autoclave treatment caused small but significant deformation in distance and angle for tissue-level and bone-level PEEK scan bodies (up to ~31 µm and 0.33°). Repeated tightening or combined autoclave plus tightening did not cause significant changes. SEM showed minor grooves after initial connection, but no progressive surface damage. PEEK scan bodies can be reused under proper sterilization without clinically relevant deformation. |

| [43] Kim, et al, 2020 | In vitro | Implants in auto polymerized resin (Orthodontic Resin) | Not applicable | 1 implant fixture | 4 scan body types: 3 made of PEEK: 1 whose base made of titanium: |

Each scan body was tightened by hand (mean 15.7 ± 1.3 Ncm), at 5 Ncm, and at 10 Ncm. Five scans were recorded per torque condition, totaling N = 45 scans. STL files were analyzed in Geomagic Control X and compared to reference CAD models. Statistical analysis: ANOVA and Tukey HSD (α = .05). | Straumann (PEEK) and Myfit Metal (titanium) scan bodies showed the lowest 3D and vertical displacements, while Dentium and Myfit (PEEK) showed higher deviations. Vertical displacement exceeded 100 µm for PEEK scan bodies under hand tightening but remained below 100 µm at 5 and 10 Ncm. Horizontal displacement was below 10 µm for all groups. PEEK scan bodies were more susceptible to deformation, particularly under hand-tightening. |

| [44] Lawand, et al, 2024 | In vitro | 1 maxillary stone cast | Full | 4 implant analogs | PEEK/TAN monolithic ISBs | 15 consecutive scans per group (NM, SM, AM) under controlled ambient conditions; reference best-fit alignment on a gingival region; measurements in Geomagic Control X | Significant differences among groups. Additionally, modified ISBs showed the highest 3D RMS error (overall ≈0.266 ± 0.030 mm) and worse trueness. subtractive modified ISBs yielded the lowest mean angular deviation (global ≈0.993 ± 0.062°) and generally better linear/angular trueness than NM and AM; Scanning time did not differ significantly among groups (≈approximately 1:30–1:40). |

| [18] Lee, et al, 2021 | In vitro | 3 mandibular modes | Full | 6 groups | PEEK and titanium (Myfit, Daegu, South Korea) | Each group scanned 10 times with each intraoral scanner (total 180 scans); best-fit superimposition to reference scan; | Both implant angulation and scan body material significantly affected trueness (p < .001). Titanium scan bodies showed better trueness (median RMS 222.1 µm) but lower within-tolerance percentage (65.7%) than PEEK (RMS 349.9 µm; within-tolerance 72.4%). Mesially tilted implants produced the best trueness (RMS 150.5–264 µm). TRIOS3 exhibited the best accuracy among scanners. Titanium scan bodies yield more accurate but less tolerant scans, and mesial angulation enhances scan trueness. |

| [45] Baranowski, et al, 2025 | In vitro | Metal mandibular cast | Full | 9 implants | PEEK titanium | Seven prototype subgroups scanned 10 times each under two mucosal thicknesses. Reference model digitized with 3Shape E3 desktop scanner (trueness 10–20 µm). Deviations analyzed in GOM Inspect (Zeiss) relative to fixed reference points (middle cross and first scan body). | Material significantly affected trueness: titanium ISBs (80 ± 72 µm polished; 89 ± 86 µm blasted) were more accurate than PEEK (149 ± 131 µm). Shorter ISBs (172 ± 143 µm) showed the highest angular deviation (0.64 ± 0.70°). Longer ISBs (248 ± 39 s) increased scanning time but did not improve accuracy. Larger screw-hole ISBs improved usability without compromising accuracy. Concave top ISBs enhanced trueness in deeper implants. Titanium blasted ISBs provided the best balance of accuracy and scanning efficiency. Stitching errors were the primary source of depth inaccuracies in full-arch scans. |

| [46] Althubaitiy, et al, 2022 | In vitro | Mandibular stone cast | Partial, missing premolars and first molar | 4 implant analogs | Titanium scan bodies and PEEK scan bodies | Each scanner performed 11 scans per condition (no ISB, titanium ISB, PEEK ISB); total 66 scans. Reference scan (S1) compared to 10 test scans (S2–S11). 3D superimposition performed in Geomagic Control X (best-fit alignment using teeth as reference). | Use of ISBs reduced overall scan precision compared to the cast without ISBs. EOS overall precision: no ISB 15.96 µm, titanium 21.68 µm, PEEK 57.57 µm. IOS overall precision: no ISB 56.87 µm, titanium 113.05 µm, PEEK 76.16 µm. EOS specific precision (best to worst): RD Ti > ND Ti > RD PEEK > ND PEEK. IOS specific precision followed the reverse order: ND PEEK > RD PEEK > ND Ti > RD Ti. EOS generally provided higher precision than IOS. |

| [47] Meneghetti, et al, 2023 | In vitro | 3d printed mandibular model | Full | 6 implants | SB1 PEEK with metal connection); SB4 3D-printed ; SB7 PEEK | STL exports aligned to the reference model using 3Shape Convince software; deviations analyzed in Blender (Blender Foundation, Amsterdam, Netherlands) with custom Python script; | Significant differences between intraoral scanners and scanbody designs (p < .001). Primescan showed the lowest median 3D deviation (110.6 µm), followed by TRIOS 4 (122.4 µm), TRIOS 3 (130.6 µm), and Omnicam (worst). The most accurate scan bodies were SB2 (Neodent PEEK, 72.3 µm) and SB7 (S.I.N. PEEK, 93.3 µm). Prototype 3D-printed resin scan bodies (SB4–SB6) exhibited the highest deviations. Linear distance deviations favored Primescan and selected PEEK scan bodies, confirming that shorter, cylindrical PEEK designs with a beveled face enhance scanning accuracy. |

| [48] Morita, et al, 2025 | In vitro | Cuboid laminated bone model | Not applicable | 1 implant | PEEK scan body (and titanium scan body | Components were tightened to 10 Ncm and 35 Ncm using a digital torque wrench (iSD900, JMM, Osaka, Japan). STL data superimposed in PolyWorks Inspector (v18.9.6181, InnovMetric, Quebec City, Canada) with bone block planes as reference. Vertical displacement measured at the top surface of each component; | All groups showed greater vertical displacement at 35 Ncm (p < 0.01). Median displacement: PEEK scan body −16.0 µm, titanium scan body −19.0 µm, titanium abutment −19.0 µm. There is no significant difference between titanium scan body and abutment, but both differed significantly from PEEK (p < 0.01). |

| [49] Nagata, et al, 2021 | Prospective clinical study | 30 patients | Partial | 50 implants | PEEK scan body | STL files from digital and conventional impressions superimposed in Geomagic Control (3D Systems, USA) after manual alignment and best-fit registration; misfit measured by averaging three points on each scan body; | Mean scan body misfit (µm): A (single implant) 40.5 ± 18.9; B1 (two-unit mesial free-end) 45.4 ± 13.4; B2 (two-unit distal free-end) 56.5 ± 9.6; C1 (three-unit mesial free-end) 50.7 ± 14.9; C2 (three-unit distal free-end) 80.3 ± 12.4. Accuracy decreased with longer spans and greater distance from adjacent teeth. |

| [50] Pan, et al, 2020 | In vitro | Maxillary resin model (Nobel Biocare), duplicated in gypsum | Full | 6 implants | PEEK scan bodies | Ten scans per condition: (1) control scan (CMM reference), (2) scan without removing scan bodies (C), (3) scan with scan bodies removed and reinserted in the same positions (CR), and (4) scan with scan bodies removed and randomly repositioned (RR). STL data analyzed in Geomagic Control 2014 (Geomagic, Morrisville, USA | Mean linear distortion: C = 16.6 µm, CR = 27.6 µm, RR = 34.2 µm. Angular deviation showed no significant differences among groups. Repositioning scan bodies significantly reduced distance precision, especially in anterior and cross-arch regions. Despite this, all deviations remained within clinically acceptable limits. |

| [51] Pan, et al, 2025 | In vitro | PEEK blocks | Not applicable | No implants, 15 Scan bodies bonded on PEEK blocks | PEEK scan bodies at different widths | Each scan body was measured three times with CMM and ten times with the lab scanner; STL data was analyzed in Geomagic Control X (Geomagic, Morrisville, USA) to calculate Euclidean distance and angular deviation. | Shape and size significantly influenced scan accuracy. Cylindrical scan bodies showed superior linear accuracy (9.5 ± 6.2 µm) compared with cuboidal (17.7 ± 8.1 µm) and spherical (12.5 ± 6.5 µm). Cuboidal scan bodies demonstrated higher angular trueness (0.050 ± 0.009°) than cylindrical (0.065 ± 0.040°). Within the cylindrical group, narrower designs (Ø4.8 mm) showed inferior accuracy, while wider (Ø5.5 mm and Ø6.5 mm) and taller (12 mm) designs achieved significantly better angular trueness (p < 0.001). Spherical scan bodies could not transfer implant angulation and were unsuitable as standalone scan bodies. |

| [52] Park, et al, 2024 | In vitro | Two identical epoxy resin mandibular reference casts | Partial | 6 implants, 3 in each cast | PEEK scan bodies | A coordinate measuring machine and digital inspection software program were used to measure the implant platform centroids (x, y, z) and projection angles (θXY, θYZ, θZX) of implant long axes in the reference and digital casts, respectively. | Significant differences were noted in all linear displacement variables among the 4 digital cast groups, except for Δx in the left premolar implant. The experimental scan bodies with a vertical stop demonstrated significantly smaller linear displacements in the 11-degree ICCIs. |

| [53] Pozzi, et al, 2022 | In vitro randomized trial | Mandibular PMMA model | Full | 4 implants | PEEK scan bodies | 60 scans (30 ISS+, 30 ISS−) taken by a single experienced operator; reference model digitized using ATOS Compact Scan 5M (GOM GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany); deviations measured via Geomagic Studio 12 and HyperCAD S; | Implant position significantly affected linear and angular deviations (p<0.0001). Posterior implants (especially those with 3.6 and 4.7 mm) showed higher deviations. Scan body splinting (ISS+) reduced linear error at position 4.7 (−60.3 µm; p=0.0188) and angular error at 3.6 (−0.2406°; p<0.0001). The splinted scan body technique improved complete-arch scanning accuracy, particularly in posterior regions. |

| [54] Qasim, et al, 2024 | In vitro | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Four types of scan bodies—PEEK bone-level | Each scan body underwent three autoclave cycles (134 °C, 20 min, 210–230 kPa). FTIR and XPS were used to assess chemical changes, while optical profilometry measured roughness at 16 standardized points per scan body. | PEEK TL and Ti BL showed significant surface roughness reduction after three sterilization cycles (p < 0.05). PEEK TL demonstrated the most notable Ra decrease (3.52 → 1.95 µm) and highest volume loss (56% after two cycles). FTIR revealed chain cleavage and ether bond degradation in PEEK (loss of diphenyl ether peak at 1185 cm⁻¹), while Ti spectra showed minimal change. XPS confirmed small increases in oxygen and decreases in carbon content after repeated autoclaving, indicating mild oxidation. |

| [55] Ren, et al, 2021 | In vitro | 48 customized mandibular 3D-printed resin models | Partial | 48 implants | PEEK short scan body and PEEK long scan body | STL files of the test datasets were superimposed onto the master reference model using Geomagic Control X (3D Systems, Rock Hill, USA); | Direct digital impressions (PEEK SSB and LSB) showed significantly higher accuracy for proximal and occlusal contacts than conventional impression methods (CPC and PUC) (p < 0.001). No significant difference between SSB and LSB (p = 0.964). Occlusal contact accuracy was lower than proximal contact in the IOS groups. Length of the scan body did not affect accuracy. |

| [56] Revilla-León, et al, 2020 | In vitro | Maxillary typodont (Hard gingiva jaw model MIS2009-U-HD-M-32; Nissin) | Partial | 3 implant replicas | Three systems for the AM subgroups: | Typodont scanned with the lab scanner using each system’s scan body to generate STL files; AM casts fabricated simultaneously with identical settings; implant replica positions on all casts measured by CMM and compared to the typodont reference via best-fit in CAD (Geomagic) | AM groups showed lower overall 3D discrepancy than conventional stone casts. Dynamic Abutment had significantly better mesiodistal and buccolingual accuracy than conventional abutments, while conventional abutments had better apicocoronal (z-axis) accuracy. Differences among AM systems mainly affected angular accuracy; linear differences among AM systems were limited. |

| [57] Sami, et al, 2020 | In vitro | Mandibular polymer model | Full | 6 implant analogs | Hexagonal PEEK scan bodies | Each scanner performed five scans (n=20 STL files). Files were imported into Geomagic Control X (3D Systems, USA), superimposed on the reference model using the “Best Fit Scenario,” and analyzed for 3D deviations with tolerance limits set at ±0.01 mm and ±0.05 mm. | None of the scanners achieved more than 10% of points within the ±0.01 mm tolerance (Emerald <5%). All scanners showed similar trueness and precision, with no statistically or clinically significant differences found. Increasing tolerance (±0.05 mm) increased the apparent accuracy but masked deviation details. 3D color maps were the most effective method for visualizing deviation patterns. |

| [58] Shely, et al, 2021 | In vitro | 3D-printed mandibular resin model (V-Print, SolFlex 650 × 350 printer, VOCO GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) | Partial | 1 implant analog | scan abutment — titanium, (PEEK body + titanium base) — one-piece PEEK, | Each scan abutment type was scanned 30 times with each scanner. STL files were superimposed using best-fit alignment (PolyWorks Inspector, InnovMetric, Canada). Deviations between lab and intraoral scans were calculated along all axes and angles. | All scan abutments showed some rotational deviation between intraoral and lab scans. The AB (PEEK + titanium) scan abutment had the largest rotational deviation (1.04°), whereas MIS (titanium) and ZZ (PEEK) abutments showed about half that (≈0.5°). The ZZ one-piece PEEK abutment demonstrated the smallest absolute displacement (D = 46 µm < 50 µm). The MIS titanium abutment showed no statistically significant displacement in X and Z axes. Differences are likely due to geometry, material, and one- vs two-piece design. |

| [59] Tawfik, et al, 2024 | In vitro | Six 3D-printed mandibular resin models (PROSHAPE MODEL 3D PRINTING 405 nm UV resin; Creality HALOT, UK) | Full | 24 implants, 4 implants per cast | PEEK ISBs and titanium ISBs | Each cast scanned under four conditions per material: dry/wet and 2 mm/4 mm exposure (total 8 scans per cast → 48 scans overall). Interimplant distances measured in Medit Design 3.1.0; | Longer ISBs (greater exposure) produced smaller differences (higher accuracy). Wet conditions increased discrepancies vs dry. Material effect was partly position-dependent: several distances showed significantly better results for titanium versus PEEK, while some (e.g., CD, AD) were not significant. Overall, authors concluded saliva worsens accuracy, longer ISBs improve it, and titanium ISBs tended to be more precise than PEEK under the tested conditions. |

| [60] Soltan et al, 2025 | In vitro | 3D-printed maxillary model covered by 2 mm silicone artificial gingiva to simulate clinical conditions. | Full | 4 implants | Titanium ISBs and PEEK ISBs | 4 × 2 factorial design — 4 IOS × 4 ISB configurations (Ti 0°, Ti 30°, PEEK 0°, PEEK 30°); n = 10 scans per group → 160 datasets. Scans aligned in Geomagic Control X using ICP algorithm. | ISB configuration, angulation, and IOS type significantly affected accuracy (P < 0.001). PEEK ISBs achieved higher trueness (mean RMS 0.019–0.060 mm) and precision (0.019–0.045 mm) than titanium (0.037–0.092 mm and 0.024–0.064 mm). PEEK 30° provided the best trueness, while PEEK 0° yielded the best precision. Angulation improved trueness for PEEK but not for titanium. Primescan and Trios 3 outperformed Aoralscan 3 and Fussen S6000. |

3.2. Accuracy of PEEK Scan Bodies

3.3. Effect of Scan Body Material

3.4. Influence of Sterilization, Reuse, and Wear

3.5. Effect of Torque and Mechanical Stability

3.6. Effect of Implant Angulation, Span Length, and Position

3.7. Effect of Intraoral Scanner Type and Scan Strategy

3.8. Effect of Scan Body Design and Geometry

| Influencing Factor | Main Findings | Clinical/Technical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Material type (PEEK vs titanium) | PEEK shows comparable or slightly superior optical performance but lower mechanical rigidity. Titanium often exhibits higher trueness in controlled conditions. | Material choice should consider scanning environment: PEEK for optical scanning ease; titanium for mechanical stability. |

| Sterilization and reuse | Minor dimensional changes occur after multiple autoclave cycles (≤10–50); accuracy generally within clinically acceptable limits (<100 µm). Excessive cycles increase surface wear and base deformation. | Limit PEEK ISB reuse to ≤10 cycles; inspect for deformation before each use. |

| Torque and seating | High torque (>10 Ncm) causes vertical displacement and deformation in PEEK ISBs; optimal torque range is 5–10 Ncm. | Standardized torque control is critical to maintain reproducible seating accuracy. |

| Implant angulation and span length | Minimal impact for short spans and aligned implants; deviations increase with long spans, posterior sites, or >25° angulation. | Use caution in multi-unit or full-arch cases; favor splinting or calibrated scanning protocols. |

| Scanner type and scanning strategy | Scanner model strongly affects accuracy (Primescan, TRIOS, Medit i700 perform best). Zig-zag or segmental scanning reduces stitching error. | Select high-performance IOS systems; optimize scanning path for long spans. |

| Geometry and height of scan body | Simple cylindrical designs and flat surfaces enhance trueness; excessive height or complex shapes may reduce accuracy. | Prefer geometrically simple, well-indexed designs with adequate supragingival exposure. |

| Environmental conditions | Light intensity, color temperature, and saliva presence influence optical detection, particularly in full-arch scans. | Control illumination and moisture during scanning to reduce data noise and stitching errors. |

| Connection type and interface stability | Instability at ISB–implant interface (especially in hybrid PEEK–titanium models) contributes to positional errors. | Ensure precise fit and avoid mixed-material ISBs where possible. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Material and Reuse-Related Aspects

4.2. Geometry and Height/Exposure

4.3. Accuracy of PEEK Scan Bodies in Intraoral Scanning Workflows

4.4. Clinical Implications and Recommendations

- Select ISBs with sufficient exposure height so that the body is well above soft tissue level and accessible to the scanner tip. This enhances signal capture and reduces distortion.

- Ensure firm, repeatable seating and tightening of the ISB using the manufacturer’s torque specification, to reduce micro-motion or mis-seating.

- Avoid excessive reuse or sterilisation cycles of PEEK scan bodies beyond documented wear thresholds. Consider inspection or replacement after a defined number of cycles.

- Control the scanning environment: dryness, limited saliva pooling, good access, minimal angulation and spacing, adequate operator training. These factors continue to influence accuracy significantly.

- Limit span and complexity when possible: For long-span or complete-arch implant cases, or angulated implants, the risk of cumulative stitching error and ISB-related distortion increases; in these scenarios, the choice of scan body material is only one of many risk factors, and the workflow should be optimised.

4.5. Research Gaps and Future Directions

- There is a lack of well-designed clinical studies that compare PEEK vs titanium (or other materials) scan bodies in actual patient workflows, since the majority of current studies are in vitro.

- Longitudinal data linking scan body material to prosthetic outcomes (fit, misfit, mechanical complications, biological peri-implant responses) are essentially lacking.

- Studies investigating clinical reuse protocols of PEEK scan bodies under real-world conditions are limited.

- Standardisation of reporting metrics for trueness/precision (e.g., consistent units, reference models, exposure heights, reuse cycles) would enable future meta-analysis and more robust evidence synthesis.

4.6. Strengths of This Review

4.7. Limitations of This Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISB | Intraoral Scan Body |

Appendix A. Detailed Search Strategies

- PubMed (MEDLINE):

- Embase:

- Scopus:

Appendix B. Characteristics of the Studies

| Author | Implant system/Connection | Control group | Scanner | Metrics |

| [32] Stimmelmayr, et al | Screwline Promote ø4.3/13 mm; Camlog Biotechnologies, Wimsheim, Germany, Directly on implant |

First scan (baseline) served as reference in both models (original implants vs. lab analogues) | Lab scanner Everest Scan Pro; KaVo, Biberach, Germany | Scanbody discrepancy (linear deviations in μm); systematic error quantified for polymer and stone models |

| [33] Giménez-Gonzalez, et al | diameter 4.1 mm, length 11 mm; Biomet 3i, Palm Beach Gardens, FL Directly on implants |

Reference obtained with coordinate measuring machine (CMM) | 3M True Definition | Linear and angular deviations |

| [34] Papaspyridakos, et al | Bone Level RC, Straumann, Basel, Switzerland, Directly on implants |

Reference extraoral scanner (Imetric IScan D103i, precision 6 μm) | TRIOS (3Shape, Denmark) | 3D deviations (trueness and precision) |

| [35] Amin, et al | bone-level implant analogs RC, Straumann, Basel, Switzerland, Directly on implant analogs |

Reference scanner (Activity 880, Smart Optics, 10 μm precision) | CEREC Omnicam (Sirona) and 3M True Definition | RMS error (3D deviation) |

| [19] Arcuri, et al | Not specified, Directly on implant analogs |

Reference scan from industrial 3D optical scanner (ATOS Compact Scan 5M, GOM GmbH) | TRIOS 3 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Linear deviations (DX, DY, DZ), Angular deviation (DANGLE), global linear error (DASS) |

| [36] Arcuri, et al |

NobelParallel RP 4.3 (Nobel Biocare, Kloten, Switzerland), | Reference scan with industrial structured blue light scanner (ATOS Compact Scan 5M, GOM GmbH) | TRIOS 3 (3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Linear deviations (∆X, ∆Y, ∆Z), Angular deviation (∆ANGLE), Euclidean distance (∆EUC) |

| [37] Azevedo, et al | Tissue-level Straumann implant analogs, Straumann, Basel, Switzerland, Directly on implant analogs |

Reference scan of master cast with desktop scanner (IScan4D LS3i, Imetric 4D, <5 µm accuracy) | TRIOS 4 (3Shape), Virtuo Vivo (Dental Wings), Medit i700 (Medit), iTero 5D (Align), Primescan (Dentsply Sirona) | Trueness (RMS error, µm), Precision (SD of RMS, µm) |

| [38] Costa Santos, et al | Neodent GM (Curitiba, Brazil) One cast implant-level junctions, One abutment-level junctions (Multi-Unit) |

Baseline scan (T0, new SBs, no autoclaving) | InEOS X5 bench scanner (Dentsply Sirona) | Trueness (RMS surface deviation, µm) per ISO 5275-4 (2020); qualitative marginal fit (adapted/misfit) |

| [39] Diker, et al | Zimmer TSV, Zimmer Dental Screwed directly on implants |

Baseline condition (before sterilization at 5, 10, 15 Ncm torque) | No IOS used – Digital Image Correlation (DIC) system with dual cameras (Vic-3D software) | Linear displacements (µm) along x, y, z axes under different torque and sterilization conditions |

| [40] Grande, et al | Nobel Biocare 6 multi-unit abutments |

Metrology-grade reference STL from Renishaw Incise (for MUA positions) + 3Shape E4 (remaining cast); test scans aligned via three fiducial spheres to this reference | TRIOS 3 POD (3shape) Medit i700 (Medit) iTero 5D (Itero) Primescan (Dentsply Sirona) |

3D linear deviation (Euclidean distance at MUA–ISB connection, µm) Angular deviations (mediolateral & anteroposterior, degrees) Interimplant distance discrepancies at connection (µm) Scanning time (s) |

| [41] Hashemi, et al | Implant analogs (4.3mm diameter×11mm length) (Replace Select, Nobel Biocare) Directly on implant analogs |

First (initial) scan for each type used as reference; subsequent 9 scans after autoclaving compared to baseline | TRIOS (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Inter-implant distance variation (mm); diameter change (mm); 3D linear displacement (ΔR, mm) |

| [42] Kato, et al | For TL, a Straumann Standard Plus Regular Neck (RN) ϕ4.1 × 10 mm implant body (Straumann, Basel, Switzer- land) and an RN SynOcta implant analog (Straumann) were placed in improved dental stone (New Fujirock Improved Dental Stone Golden Brown, GC, Tokyo, Japan). For BL, a Straumann BL Regular CrossFit (RC) ϕ4.1 × 10 mm (Straumann) and an RC implant analog (Straumann) were placed in an improved dental stone (GC) Scan bodies directly on implants |

Baseline (pre-sterilization) scans | TRIOS 3 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Autoclave at 135°C for 3 min; torque 15 Ncm; 10 repeated connection/disconnection cycles; STL analysis using PolyWorks Inspector (InnovMetric, Canada); SEM for surface texture; statistical tests with t-test and Tukey (p < 0.05) |

| [43] Kim, et al | Internal hexagon implant fixture Scan bodies directly on implants |

Myfit Metal (titanium scan body) used as reference | E1 laboratory scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | 3D, vertical, and horizontal displacements (µm) based on root mean square (RMS) deviation |

| [44] Lawand, et al | Implant analogs (RC Bone Level Implant Analog; Institut Straumann AG) scan bodies directly on analogs |

Desktop reference scan of the same cast with ISBs (3Shape E3) used as the metrology reference STL | TRIOS 3 (3Shape) | 3D surface deviation (RMS, mm) on the ISB’s upper geometric bevel; linear centroid distance discrepancies between ISBs (mm); angular deviations between ISB axes (degrees); scanning time (min) |

| [18] Lee, et al | Implant system: Bone level, IS-III active, Neobiotech Co., Seoul, South Korea Directly on implants |

Reference scan from a desktop scanner (Identica T500, Medit, Korea) | CS3600 (Carestream Dental), TRIOS 3 (3Shape), and Primescan (Sirona Dental Systems) | Trueness (RMS deviation, µm) and percentage within ±0.1 mm tolerance |

| [45] Baranowski, et al | Implants Nobel Replace, Nobel Biocare (Zurich, Switzerland) Scan bodies directly on implants |

Commercial PEEK scan body (ELOS Accurate IO-2A-B); each IOS scan was followed by digitization with a 3Shape E3 desktop scanner to establish a baseline reference. | NeoScan1000 intraoral scanner (Neoss, Gothenburg, Sweden) | Depth deviation (µm), angular deviation (°), rotational deviation (°), and scanning time (s) |

| [46] Althubaitiy, et al | Straumann Bone Level analogs (2 Narrow CrossFit and 2 Regular CrossFit) Scan bodies directly on implants |

In each condition (no SB, titanium SB, PEEK SB), the first scan (S1) served as the reference; scans S2–S11 were superimposed onto S1 to assess precision. | Extraoral scanner (E1; 3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) and intraoral scanner (TRIOS 3; 3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Root mean square (RMS) deviation (µm) for overall and specific precision |

| [47] Meneghetti, et al | Implants 4.1 × 10 mm (S.I.N. Implant System, São Paulo, Brazil) Scan bodies screwed on multi-unit abutments (S.I.N. Implant System, São Paulo, Brazil) |

Desktop reference scans with 3Shape D2000 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) of the master model and of the model with each SB set | Primescan (Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) Omnicam (Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) TRIOS 3 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) TRIOS 4 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) |

3D trueness deviation (µm), angular deviation (degrees), and linear distance deviation between implants #3 and #14 |

| [48] Morita, et al | Bone Level Implant Ø4.1 × 10 mm; Straumann, Basel, Switzerland Scan body directly on implant |

Model scanned with components tightened at 10 Ncm used as the reference (S1) | E4 laboratory scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Vertical displacement (µm) along the implant axis |

| [49] Nagata, et al | Straumann Bone Level implants (Ø4.1 mm, Basel, Switzerland) Scan bodies directly on implants |

Conventional silicone impressions made with an open tray; plaster models scanned with a Ceramill Map400 desktop scanner (Amann Girrbach, Vienna, Austria) used as the reference | TRIOS 3 intraoral scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Scan body misfit (µm) |

| [50] Pan, et al | NobelActive, internal RP Ø4.3 × 13 mm (Nobel Biocare AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) with MUA Plus (Nobel Biocare AB) Scan bodies on multi-unit |

The reference dataset of the gypsum model was obtained using a coordinate measuring machine (CMM; ZEISS Contura G2 RDS, Oberkochen, Germany) | Zfx Evolution plus+ laboratory scanner (Zimmer Biomet, USA) | Linear and angular trueness (µm, degrees) and precision of inter-implant measurements |

| [51] Pan, et al | Not applicable | Reference measurements obtained using a coordinate measuring machine (CMM; ZEISS Contura G2 RDS, Oberkochen, Germany) | D2000 laboratory scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Linear trueness (µm), linear precision (µm), angular trueness (°), angular precision (°) |

| [52] Park, et al | FIT 4310 (7° internal conical connection implant) and FIU 4510 (11° internal conical connection implant), Ø4.3×10 mmWarantec Co., Seoul, South Korea. | |||

| [53] Pozzi, et al | Internal conical connection implant analogs, NobelParallel RP 4.3, Nobel Biocare, Kloten, Switzerland. Scan bodies directly on implants |

Scans performed without splinting the scan bodies (ISS−) served as the control, The master model was digitized with a coordinate measuring machine (ATOS Compact Scan 5M; GOM GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) | TRIOS 3 (3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Linear deviations (ΔX, ΔY, ΔZ) and angular deviations (ΔANGLE); combined linear absolute error (ΔASS) |

| [54] Qasim, et al | Not applicable | Baseline (pristine, unsterilized) scan bodies served as reference for chemical and surface comparison | FTIR (Tensor 27, Bruker Optics, Germany), XPS (ESCA Lab250xi, Thermo Scientific, USA), and optical profilometer (DCM8, Leica Microsystems, Germany). | Surface roughness (Ra, µm), volume loss (%), FTIR peak shifts, and elemental composition (atomic %). |

| [55] Ren, et al | TSIII SA, Osstem, Seoul, South Korea (bone-level conical, 4.0 × 10 mm), Scan bodies screwed directly on implants |

Reference dataset (master model) obtained by scanning the resin model with a laboratory scanner (E1 scanner; 3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark). | CS3600 (Carestream Dental, Atlanta, USA) intraoral scanner for direct data capture; E1 (3Shape, Denmark) laboratory scanner for reference and indirect data capture. | Mesial, distal, and occlusal distances (µm) between test datasets and master reference model. |

| [56] Revilla-León, et al | Brånemark system RP implant replicas (Nobel Biocare) Scan bodies directly on implants |

Positions of implant replicas on the original typodont measured with a coordinate-measuring machine (CMM Contura G2; Carl Zeiss); these CMM coordinates served as the reference to compare all casts (CNV and AM) | E3 laboratory scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) used to digitize the typodont for AM workflows E3 laboratory scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) used to digitize the typodont for AM workflows | Linear discrepancies on x, y, z axes and combined 3D discrepancy (√[x²+y²+z²]); angular discrepancies on XZ and YZ projections; non-parametric statistics (Kruskal–Wallis, Mann–Whitney with Bonferroni) |

| [57] Sami, et al | Ritter Implants, 1A-3.75 Scan bodies directly on implants |

Reference scan obtained using a high-accuracy industrial laser line probe (Edge ScanArm HD; FARO Technologies, USA) | Four intraoral scanners tested — True Definition (3M ESPE, USA, software v5.2.1) TRIOS (3Shape A/S, Denmark, software v1.4.7.5) CEREC Omnicam (Dentsply Sirona, Germany, software v4.5.0) Emerald Scanner (Planmeca, Finland, software v4.6.0) |

Trueness and precision (root mean square [RMS], arithmetic average [AA], within-tolerance % at ±0.01 mm and ±0.05 mm). |

| [58] Shely, et al | MIS internal hex implant analog (3.75 × 11.5 mm; MIS Implants Technologies, Israel) Scan body directly on implant |

The laboratory scanner dataset (TRIOS E2, 3Shape, Denmark) served as the gold standard reference for evaluating the accuracy of the IOS | Omnicam (CEREC AC, Dentsply Sirona, Milford, DE, USA) intraoral scanner. | Linear displacement (X, Y, Z axes, absolute distance D) and angular deviations (rotational and longitudinal angles). |

| [59] Tawfik, et al | C-TECH implants 4.3 × 9 mm (Bologna, Italy) Scan bodies directly on implants |

Coordinate measuring machine (CMM; stated accuracy 0.0001 mm) provided reference 3D coordinates of implant centers | Medit i700 intraoral scanner (Medit Corp., Seoul, South Korea) | Six interimplant distances measured in micrometers — AB (canine–first premolar right), BC (first premolar–first molar right), CD (first molar right–first molar left), AD (canine right–first molar left), AC (canine right–first molar right), and BD (first premolar right–first molar left) — calculated as mean deviations from the CMM reference model. |

| [60] Soltan et al | Nobel Biocare RP implants (Zurich, Switzerland) Scan bodies directly on implants |

High-resolution desktop scanner E3 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) | Primescan (Dentsply Sirona, USA) Trios 3 (3Shape, Denmark) Aoralscan 3 (Shining 3D, China) Fussen S6000 (Fussen Technology Co., China). |

Trueness (RMS deviation vs. reference model) and precision (RMS deviation among repeated scans). |

References

- Rhee, Y.K.; Huh, Y.H.; Cho, L.R.; Park, C.J. Comparison of intraoral scanning and conventional impression techniques using 3-dimensional superimposition. J Adv Prosthodont. 2015;7(6):460-467. [CrossRef]

- Albanchez-González, M.I.; Brinkmann, J.C.; Peláez-Rico, J.; López-Suárez, C.; Rodríguez-Alonso, V.; Suárez-García, M.J. Accuracy of Digital Dental Implants Impression Taking with Intraoral Scanners Compared with Conventional Impression Techniques: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2026. Published 2022 Feb 11. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.S. Mechanical complications of dental implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2000;11 Suppl 1:156-158. [CrossRef]

- Abduo, J.; Judge, R.B. Implications of implant framework misfit: a systematic review of biomechanical sequelae. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29(3):608-621. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.D.; Wei, D.H.; Di, P.; Lin, Y. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;54(10):707-711. [CrossRef]

- Blatz, M.B.; Conejo, J. The Current State of Chairside Digital Dentistry and Materials. Dent Clin North Am. 2019;63(2):175-197. [CrossRef]

- Michelinakis, G.; Apostolakis, D.; Kamposiora, P.; Papavasiliou, G.; Özcan, M. The direct digital workflow in fixed implant prosthodontics: a narrative review. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):37. Published 2021 Jan 21. [CrossRef]

- M Mangano, F.G.; Hauschild, U.; Veronesi, G.; Imburgia, M.; Mangano, C.; Admakin, O. Trueness and precision of 5 intraoral scanners in the impressions of single and multiple implants: a comparative in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):101. Published 2019 Jun 6. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, R.; Galli, M.; Chen, Z. et al. Intraoral scanning reduces procedure time and improves patient comfort in fixed prosthodontics and implant dentistry: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(12):6517-6531. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Alshehri, Y.F.A.; Kruger, E.; Villata L. Accuracy of digital versus conventional implant impressions in partially dentate patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2025;160:105918. [CrossRef]

- Alfaraj, A.; Alqudaihi, F.; Khurshid, Z.; Qadiri, O.; Lin, W.S. Comparative analyses of accuracy between digital and conventional impressions for complete-arch implant-supported fixed dental prostheses-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthodont. Published online July 14, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.S.; Harris, B.T.; Morton, D. The use of a scannable impression coping and digital impression technique to fabricate a customized anatomic abutment and zirconia restoration in the esthetic zone. J Prosthet Dent. 2013;109(3):187-191. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.R.; Seo, K.Y.; Kim, S. Conventional open-tray impression versus intraoral digital scan for implant-level complete-arch impression. J Prosthet Dent. 2019;122(6):543-549. [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.; Lerner, H.; Margiani, B.; Solop, I.; Latuta, N.; Admakin, O. Congruence between Meshes and Library Files of Implant Scanbodies: An In Vitro Study Comparing Five Intraoral Scanners. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7):2174. Published 2020 Jul 9. [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, C.D.; Ritter, R.G. Utilization of digital technologies for fabrication of definitive implant-supported restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(5):299-308. [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, R.M.; Yilmaz, B. Intraoral scan bodies in implant dentistry: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2018;120(3):343-352. [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Gómez-Polo, M.; Rutkunas, V.; Ntovas, P.; Kois, J.C. Classification of Complete-Arch Implant Scanning Techniques Recorded by Using Intraoral Scanners. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2025;37(1):236-243. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Bae, J.H.; Lee, S.Y. Trueness of digital implant impressions based on implant angulation and scan body materials. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21892. Published 2021 Nov 8. [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, L.; Pozzi, A.; Lio, F.; Rompen, E.; Zechner, W.; Nardi, A. Influence of implant scanbody material, position and operator on the accuracy of digital impression for complete-arch: A randomized in vitro trial. J Prosthodont Res. 2020;64(2):128-136. [CrossRef]

- Pachiou, A.; Zervou, E.; Tsirogiannis, P.; Sykaras, N.; Tortopidis, D.; Kourtis, S. Characteristics of intraoral scan bodies and their influence on impression accuracy: A systematic review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023;35(8):1205-1217. [CrossRef]

- Karthhik, R.; Raj, B. Karthikeyan BV. Role of scan body material and shape on the accuracy of complete arch implant digitalization. J Oral Res Rev. 2022;14(2):114. [CrossRef]

- Panayotov, I.V.; Orti, V.; Cuisinier, F.; Yachouh, J. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) for medical applications. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2016;27(7):118. [CrossRef]

- Skirbutis. G.; Dzingutė, A.; Masiliūnaitė, V.; Šulcaitė, G.; Žilinskas, J. PEEK polymer's properties and its use in prosthodontics. A review. Stomatologija. 2018;20(2):54-58.

- Papathanasiou, I.; Kamposiora, P.; Papavasiliou, G.; Ferrari, M. The use of PEEK in digital prosthodontics: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):217. Published 2020 Aug 2. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Limpuangthip, N.; Hlaing, N.H.M.M.; Hahn, S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.J. Enhancing scanning accuracy of digital implant scans: A systematic review on application methods of scan bodies. J Prosthet Dent. 2024;132(5):898.e1-898.e9. [CrossRef]

- Grande, F.; Nuytens, P.; Zahabiyoun, S.; Iocca, O.; Catapano, S.; Mijiritsky, E. Factors influencing the intraoral implant scan accuracy: a review of the literature. J Dent. 2025;161:105973. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, P.; Rashidpour, M.; Sader, R.; Weigl, P. A systematic review of factors impacting intraoral scanning accuracy in implant dentistry with emphasis on scan bodies. Int J Implant Dent. 2024;10(1):20. Published 2024 May 1. [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, R.; Djalalinia, S.; Alikhasi, M. The Effects of Scan Body Geometry on the Precision and the Trueness of Implant Impressions Using Intraoral Scanners: A Systematic Review. Dent J (Basel). 2025;13(6):252. Published 2025 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Fratila, A.M.; Saceleanu, A.; Arcas, V.C.; Fratila, N.; Earar, K. Enhancing Intraoral Scanning Accuracy: From the Influencing Factors to a Procedural Guideline. J Clin Med. 2025;14(10):3562. Published 2025 May 20. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, P.S.; Gangurde, A.P.; Chauhan, M.R.; Jaiswal, N.V.; Salian, P.R.; Singh, V. Accuracy of the digital implant impression with splinted and non-splinted intraoral scan bodies: A systematic review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2025;25(1):3-12. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M. et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. Published 2021 Mar 29. [CrossRef]

- Stimmelmayr, M.; Güth, J.F.; Erdelt, K.; Edelhoff, D.; Beuer, F. Digital evaluation of the reproducibility of implant scanbody fit--an in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16(3):851-856. [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Gonzalez, B.; Hassan, B.; Özcan, M.; Pradíes, G. An In Vitro Study of Factors Influencing the Performance of Digital Intraoral Impressions Operating on Active Wavefront Sampling Technology with Multiple Implants in the Edentulous Maxilla. J Prosthodont. 2017;26(8):650-655. [CrossRef]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Gallucci, G.O.; Chen, C.J.; Hanssen, S.; Naert, I.; Vandenberghe, B. Digital versus conventional implant impressions for edentulous patients: accuracy outcomes. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(4):465-472. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Weber, H.P.; Finkelman, M.; El Rafie, K.; Kudara, Y.; Papaspyridakos, P. Digital vs. conventional full-arch implant impressions: a comparative study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(11):1360-1367. [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, L.; Lio, F.; Campana, V.; et al. Influence of Implant Scanbody Wear on the Accuracy of Digital Impression for Complete-Arch: A Randomized In Vitro Trial. Materials (Basel). 2022;15(3):927. Published 2022 Jan 25. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, L.; Marques, T.; Karasan, D.; et al. Influence of Implant ScanBody Material and Intraoral Scanners on the Accuracy of Complete-Arch Digital Implant Impressions. Int J Prosthodont. 2024;37(5):575-582. [CrossRef]

- Costa Santos, F.H.P.; de Melo, P.S.; Borella, P.S.; Neves, F.D.D.; Zancope, K. Effect of autoclaving process on trueness and qualitative marginal fit of intraoral scan body manufactured from two materials: An in vitro study. PLoS One. 2025;20(6):e0325068. Published 2025 Jun 23. [CrossRef]

- Diker, E.; Terzioglu, H.; Gouveia, D.N.M.; Donmez, M.B.; Seidt, J.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of material type, torque value, and sterilization on linear displacements of a scan body: An in vitro study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2023;25(2):419-425. [CrossRef]

- Grande, F.; Mosca Balma, A.; Mussano, F.; Catapano, S. Effect of Implant Scan Body type, Intraoral scanner and Scan Strategy on the accuracy and scanning time of a maxillary complete arch implant scans: an in vitro study. J Dent. 2025;159:105782. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud Hashemi, A.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Payaminia, L.; Alikhasi, M. Effect of Repeated Use of Different Types of Scan Bodies on Transfer Accuracy of Implant Position. J Dent (Shiraz). 2023;24(4):410-416. Published 2023 Dec 1. [CrossRef]

- EKato, T.; Yasunami, N.; Furuhashi, A.; Sanda, K.; Ayukawa, Y. Effects of Autoclave Sterilization and Multiple Use on Implant Scanbody Deformation In Vitro. Materials (Basel). 2022;15(21):7717. Published 2022 Nov 2. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Son, K.; Lee, K.B. Displacement of scan body during screw tightening: A comparative in vitro study. J Adv Prosthodont. 2020;12(5):307-315. [CrossRef]

- Lawand, G.; Ismail, Y.; Revilla-León, M.; Tohme, H. Effect of implant scan body geometric modifications on the trueness and scanning time of complete arch intraoral implant digital scans: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2024;131(6):1189-1197. [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, J.H.; Stenport, V.F.; Braian, M.; Wennerberg, A. Effects of scan body material, length and top design on digital implant impression accuracy and usability: an in vitro study. J Adv Prosthodont. 2025;17(3):125-136. [CrossRef]

- Althubaitiy, R.; Sambrook, R.; Weisbloom, M.; Petridis, H. The Accuracy of Digital Implant Impressions when Using and Varying the Material and Diameter of the Dental Implant Scan Bodies. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2022;30(4):305-313. Published 2022 Nov 30. [CrossRef]

- Meneghetti, P.C.; Li, J.; Borella, P.S.; Mendonça, G.; Burnett, L.H. Jr. Influence of scanbody design and intraoral scanner on the trueness of complete arch implant digital impressions: An in vitro study. PLoS One. 2023;18(12):e0295790. Published 2023 Dec 19. [CrossRef]

- Morita, D.; Matsuzaki, T.; Sakai, N.; Ogino, Y.; Atsuta, I.; Ayukawa, Y. Influence of material and tightening torque on the subsidence of implant scan bodies. J Prosthodont Res. Published online April 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Fuchigami, K.; Okuhama, Y.; et al. Comparison of digital and silicone impressions for single-tooth implants and two- and three-unit implants for a free-end edentulous saddle. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):464. Published 2021 Sep 23. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Tam, J.M.Y.; Tsoi, J.K.H.; Lam, W.Y.H.; Pow, E.H.N. Reproducibility of laboratory scanning of multiple implants in complete edentulous arch: Effect of scan bodies. J Dent. 2020;96:103329. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Dai, X.; Tsoi, J.K.; Lam, W.Y.; Pow, E.H. Effect of shape and size of implant scan body on scanning accuracy: An in vitro study. J Dent. 2025;152:105498. [CrossRef]

- Park, G.S.; Chang, J.; Pyo, S.W.; Kim, S. Effect of scan body designs and internal conical angles on the 3-dimensional accuracy of implant digital scans. J Prosthet Dent. 2024;132(1):190.e1-190.e7. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, A.; Arcuri, L.; Lio, F.; Papa, A.; Nardi, A.; Londono, J. Accuracy of complete-arch digital implant impression with or without scanbody splinting: An in vitro study. J Dent. 2022;119:104072. [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.S.B.; Akbar, A.A.; Sadeqi, H.A.; Baig, M.R. Surface Characterization of Bone-Level and Tissue-Level PEEK and Titanium Dental Implant Scan Bodies After Repeated Autoclave Sterilization Cycles. Dent J (Basel). 2024;12(12):392. Published 2024 Dec 3. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Son, K.; Lee, K.B. Accuracy of Proximal and Occlusal Contacts of Single Implant Crowns Fabricated Using Different Digital Scan Methods: An In Vitro Study. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(11):2843. Published 2021 May 26. [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Fogarty, R.; Barrington, J.J.; Zandinejad, A.; Özcan, M. Influence of scan body design and digital implant analogs on implant replica position in additively manufactured casts. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;124(2):202-210. [CrossRef]

- An iSami, T.; Goldstein, G.; Vafiadis, D.; Absher, T. An in vitro 3D evaluation of the accuracy of 4 intraoral optical scanners on a 6-implant model. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;124(6):748-754. [CrossRef]

- Shely, A.; Lugassy, D.; Rosner, O.; et al. The Influence of Laboratory Scanner versus Intra-Oral Scanner on Determining Axes and Distances between Three Implants in a Straight Line by Using Two Different Intraoral Scan Bodies: A Pilot In Vitro Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(20):6644. Published 2023 Oct 20. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, M.H.A.; El Torky, I.R.; El Sheikh, M.M. Effect of saliva on accuracy of digital dental implant transfer using two different materials of intraoral scan bodies with different exposed lengths. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):1428. Published 2024 Nov 23. [CrossRef]

- Soltan, H.; Mai, X.; Ramdan, A.S.; Saleh, M.Q.; Ashour, S.H.; Xie, W. Impact of implant scan body material and angulation on the trueness and precision of digital implant impressions using four intraoral scanners-an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2025;25(1):1288. Published 2025 Jul 31. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, L.; Wen, C. Effects of inter-implant tooth loss and scan body material on digital impression accuracy: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2025;25(1):1502. Published 2025 Sep 29. [CrossRef]

- Aktas, A.; Manav, T.Y.; Zortuk, M. Effect of reusing impression posts and scan bodies on recording accuracy. J Prosthet Dent. 2025;133(5):1324.e1-1324.e7. [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Lazcano, A.; Anitua, B.; Eguia, A.; Alkhraisat, M.H. Influence of scan body geometry on the trueness of intraoral scanning. BDJ Open. 2025;11(1):83. Published 2025 Oct 18. [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, E.; Lagreca, G.; Papaspyridakos, P., et al. Effect of supramucosal height of a scan body and implant angulation on the accuracy of intraoral scanning: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2024;131(6):1126-1134. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jo, J.S.; Lee, S.Y. Digital impression accuracy for bone-level and tissue-level implants using scan bodies of different heights. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):37367. Published 2025 Oct 27. [CrossRef]

- InChen, Z.; Yu, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.L.; Li, J. Influence of scan aid surface color on accuracy of calibrated intraoral scan protocol in complete arch implant digital scans. J Prosthet Dent. Published online October 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Biadsee, A.; Yusef, R.; Melamed, G.; Ormianer, Z. Scan Body Discrepancies in Bone- and Tissue-Level Implants: In Vitro Study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. Published online October 28, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Karakuzu, M.; Öztürk, C.; Karakuzu, Z.B.; Zortuk, M. The effects of different lighting conditions on the accuracy of intraoral scanning. J Adv Prosthodont. 2024;16(5):311-318. [CrossRef]

- Thanasrisuebwong, P.; Kulchotirat, T.; Anunmana, C. Effects of inter-implant distance on the accuracy of intraoral scanner: An in vitro study. J Adv Prosthodont. 2021;13(2):107-116. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).