1. Notations

Throughout this paper, by we mean the free group on the set of generators for an algebraically closed field . Note that, this notation also could be used in order to present the free associative algebra on n generators.

2. Introduction

Let us start this paper with a quote from Arthur Cayley,

As for everything else, so for a mathematical theory: beauty can be perceived but not explained.

The main purpose of this paper is to study the Cayley graphs, which are named after Arthur Cayley, and are one of the important concepts in mathematics relaiting the group theory with the theory of locally finite regular (di)graphs. In order to have a Cayley graph, one needs a finite group G and a generating set S closed under inverse and .

Cayley graphs are important in order to encode the relevant information about the group, such as its size and the number of generators. But in our opinion, the most important future of the Cayley graphs could be providing us with some very interesting sets of regulated (di)graphs. For example, the free groups on n elements and the associated Cayley graphs could be one of those important examples. Here n goes back to the order of the free group and i indicates the different set of generating sets.

Let G be an arbitrary finite group and S be a generating set of it.

Definition 1.

The Cayley graph is an undirected graph having vertex set and the edge set , meaning that there is a vertex for every element in G, and an edge from g to for every and . (Parallel edges and loops are allowed)

Remark 1.

- (i)

Note that the condition of being undirected goes back to the fact that is invertible.

- (ii)

We mostly are interested in infinite families of Cayley graphs which are expanding as one structure.

- (iii)

As the Cayley graph depends on the chosen generating set, hence it is not unique in most cases.

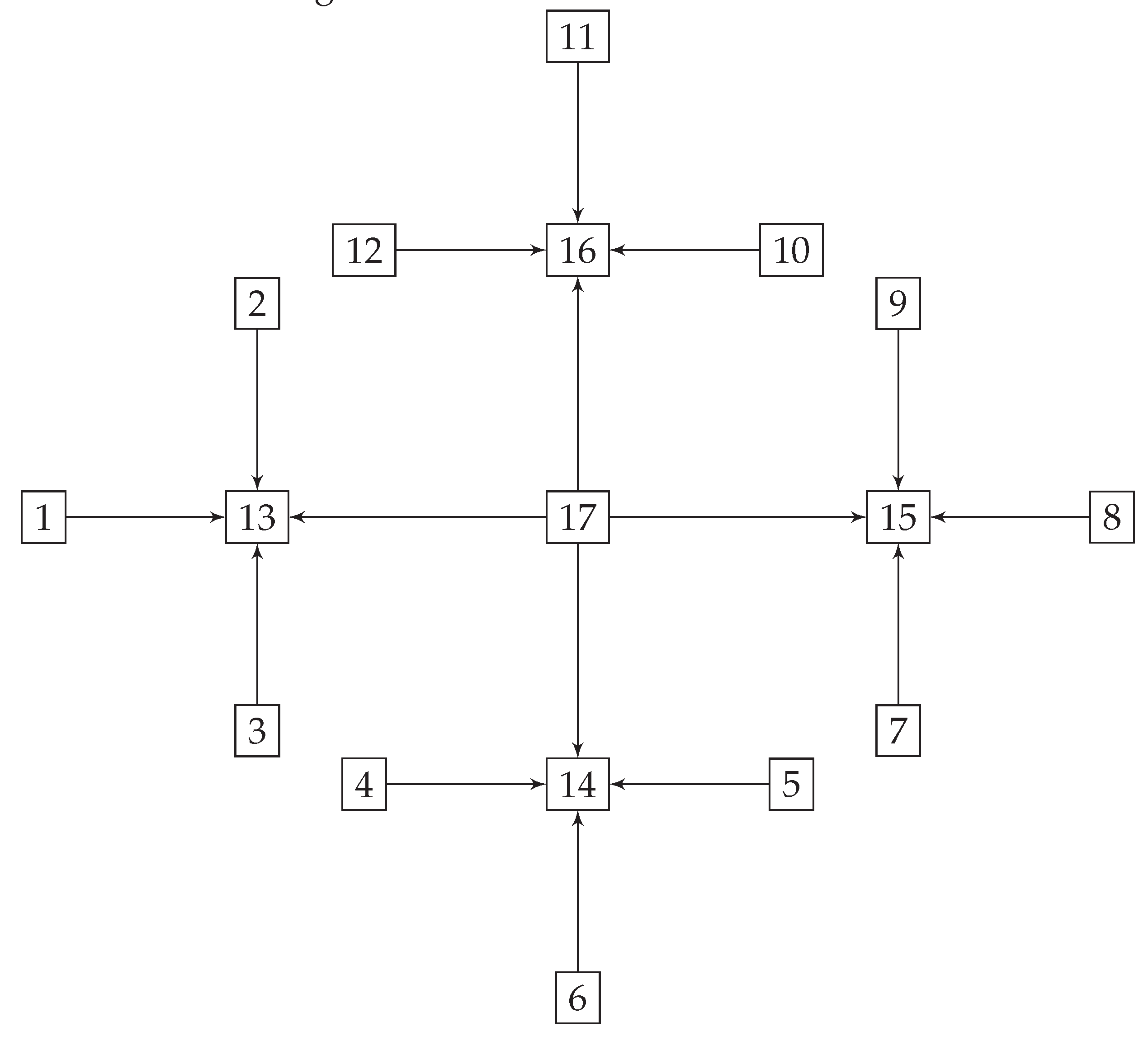

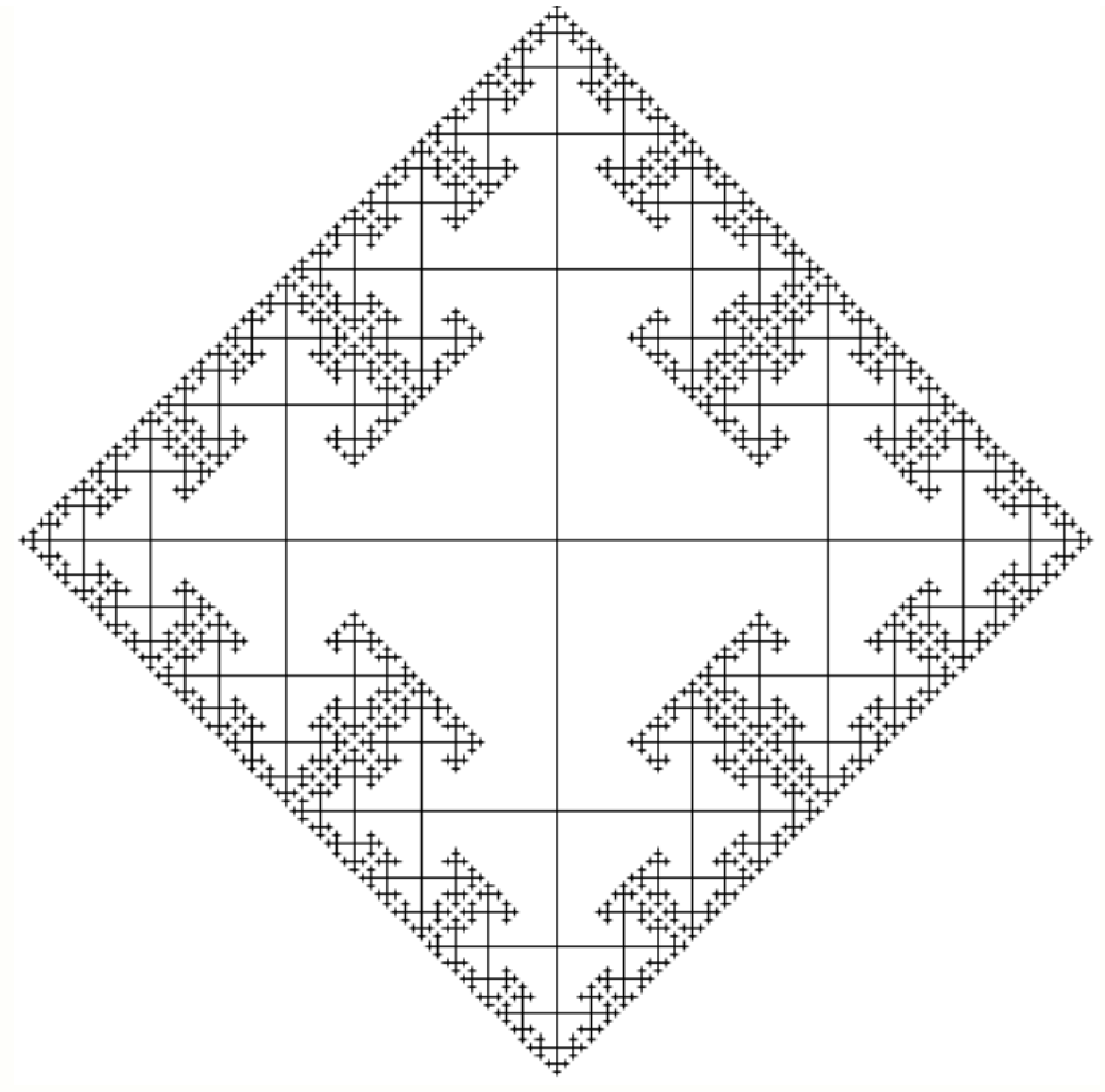

Following Remark 1c, consider the free group and let be a pointwise isomorphism. Let be the generating set. Then we have the following result.

Proposition 1.

The quantum automorphism group is non-trivial.

Proof. To prove this assertion, by following the approach used in our paper [

14], we know that in order to find if

is non-trivial, we have to prove that

possess quantum symmetries, meaning that for the adjacency matrix

there exists a noncommutative projective unitary matrix

, such that

, and to do that, we need to put a reasonable orientation on

in a way that the quantum automorphism group of the non-oriented could be identified with the oriented one!

As stated earlier in this paper, the goal is to work with the infinite Cayley graphs, but to proceed smoothly, let us start with the following.

It is not too difficult to observe that the only noncommutative projective unitary matrix

such that

satisfies, for

the adjacency matrix, will be as follows, for

and

s mutually noncommutative entities.

and for the infinite expandable Cayley graph

associated with

, and illustrated in

Figure 2, the noncommutative projective unitary matrix will be as follows.

where

,

, are Sudoku unitary matrices

, for

s,

, distinct orthogonal projections, meaning that

for any

.

□

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

2.1. n-Dimensional Hyperoctahedral Group

Consider the set of segments , for , and let be the space consisting of symmetries such that each turns and keeps the other segments fixed. Note that elements have order two and commute with each other, and hence they could be considered as the generators of the product of n copies of . Let us call this new non-free group .

On the other hand, the symmetric group

could act on

by permuting the segments, and

could be defined by using this action as the symmetric group of the graph formed by the

n segments

, or in other words the

n-dimensional Hypercube

. Note that as a symmetric group, we have

As in [

10], one may look at the

n-dimensional Hypercube

as the Cayley graph of

with respect to the generating set

consisting of the canonical generators

, where 1 is located in the

ith coordinate, and two vertices in

are connected if and only if their difference belongs to

E.

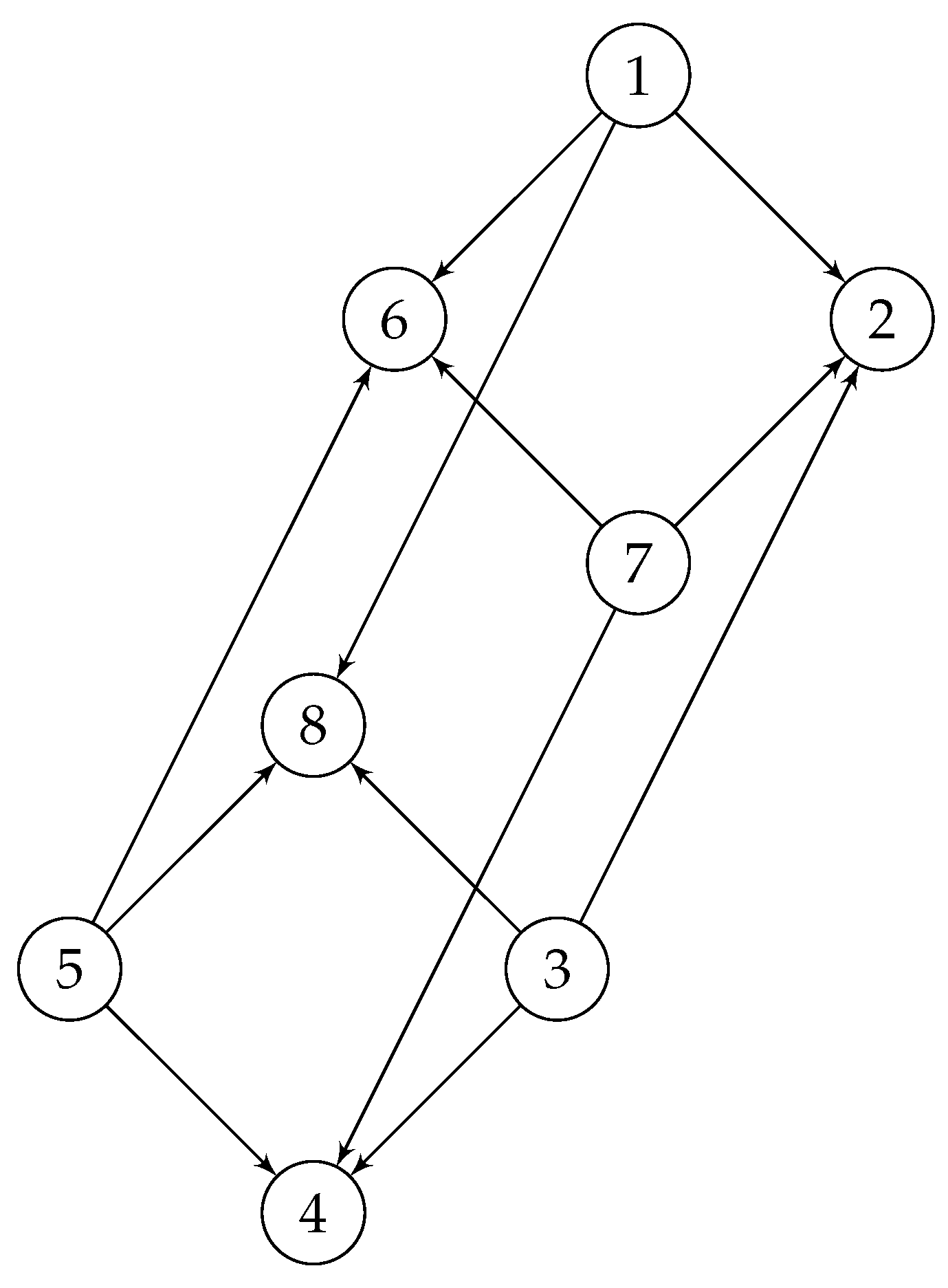

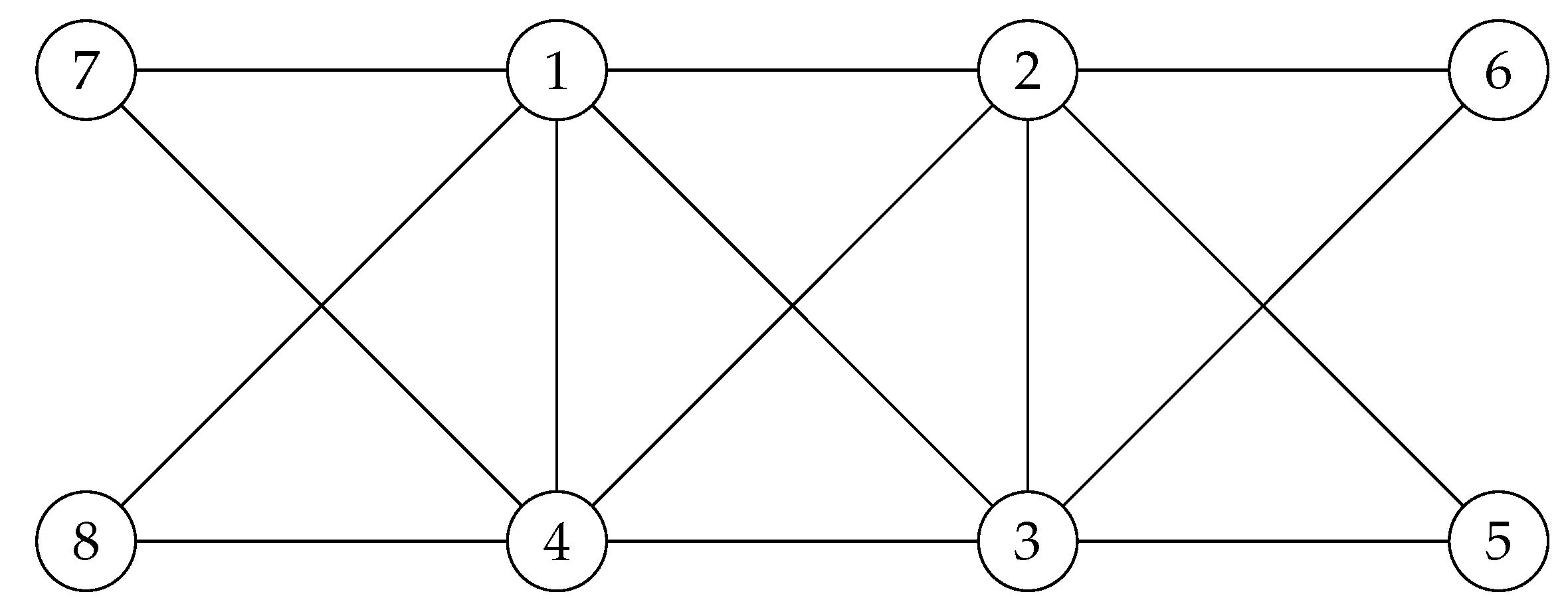

Let us start with the case, which is the usual 3-dimensional cube. Its symmetric group is and we have the following minor result.

Proposition 2.

The quantum automorphism group of is nontrivial.

Proof. To prove this claim, we will follow the steps taken from our previous work [

14] and illustrated in Proposition 1. This means that we try to have a reasonable orientation on

and then we prove that the oriented one has quantum symmetries, such that its quantum automorphism group coincides with the non-oriented one. So let us consider the following oriented version of

.

It is not too difficult to observe that the only noncommutative projective unitary matrix

that could commute with the adjacency matrix

could be formulated as follows, for the orthogonal projections

such that

.

meaning that

possesses quantum symmetry and its quantum automorphism group is non-trivial.

In conclusion, one may check the truthfulness of the relation , resulting in the non-triviality of the quantum automorphism group of . □

In [

15] we studied the actions of

on matrix groups. It is already known that the generators of

are of the form

for

such that

for

.

Hence one might think of

as the free (quantum) group of order

n, generated by

, with the associated Cayley graph studied in the previous section. However, this study is important because of the study conducted in [

4], Theorem 10.1, and the subsequent discussion for the possible generalization to the

n-dimensional Hypercube.

In [

9,

10], it has been shown that the quantum automorphism group of

is the anticommutative orthogonal quantum group

which clearly proves the truthfulness of our result obtained in Proposition 2 for case

.

Remark 2.

Note that the claim stated in Proposition 2 has been thoroughly studied in [5] and, as a result, we know that the quantum automorphism group of the n-dimensional Hypercube is the quantum Hyperoctahedral group seen as a subgroup of [7], and in particular we have . But the advantage of our study is that we will completely clarify the generators of thoroughly, which is important!

The following result has been extensively studied in [

9,

10], but as has been already mentioned, the advantage of our study is studying generators of

in general and

as the special case.

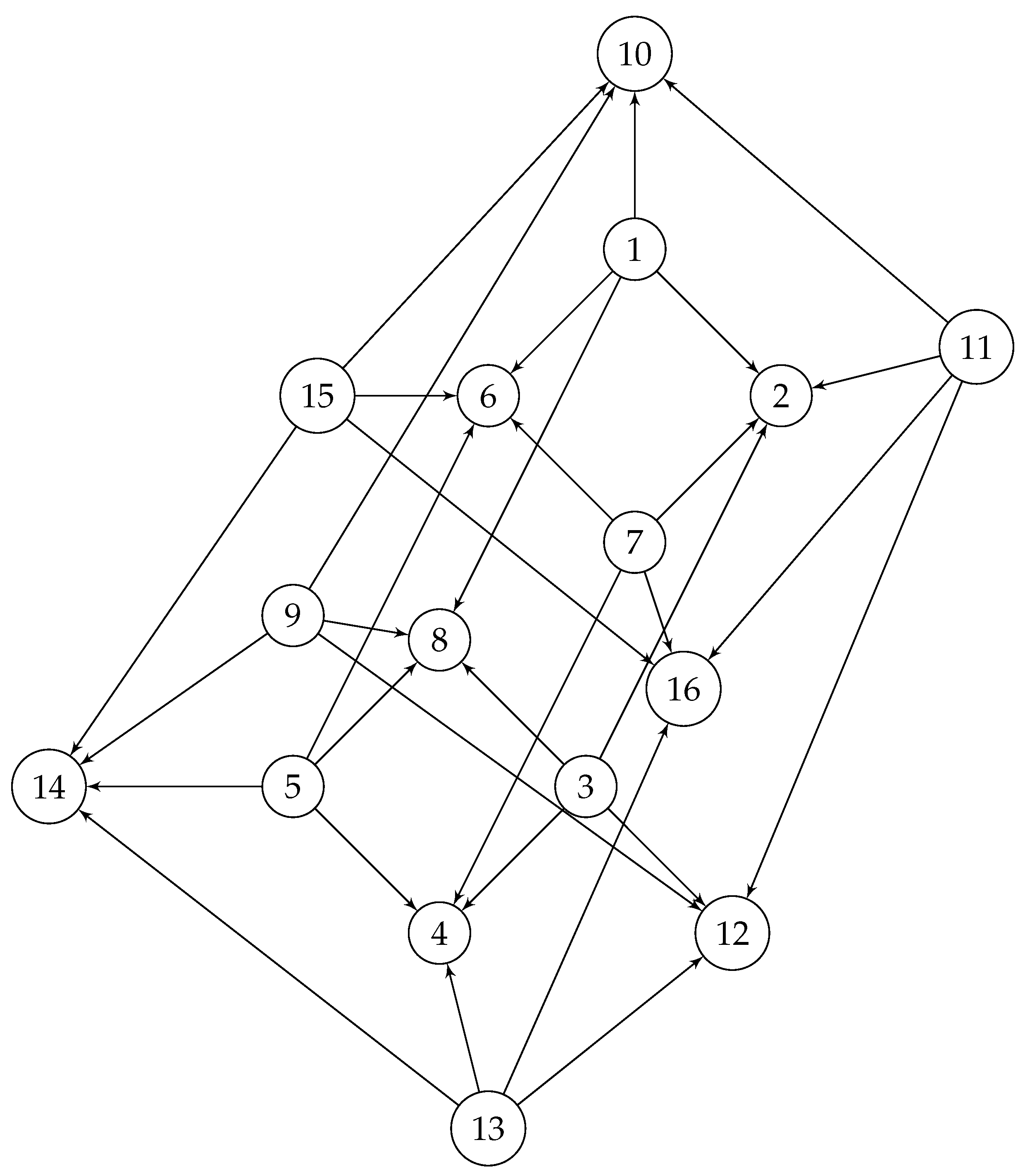

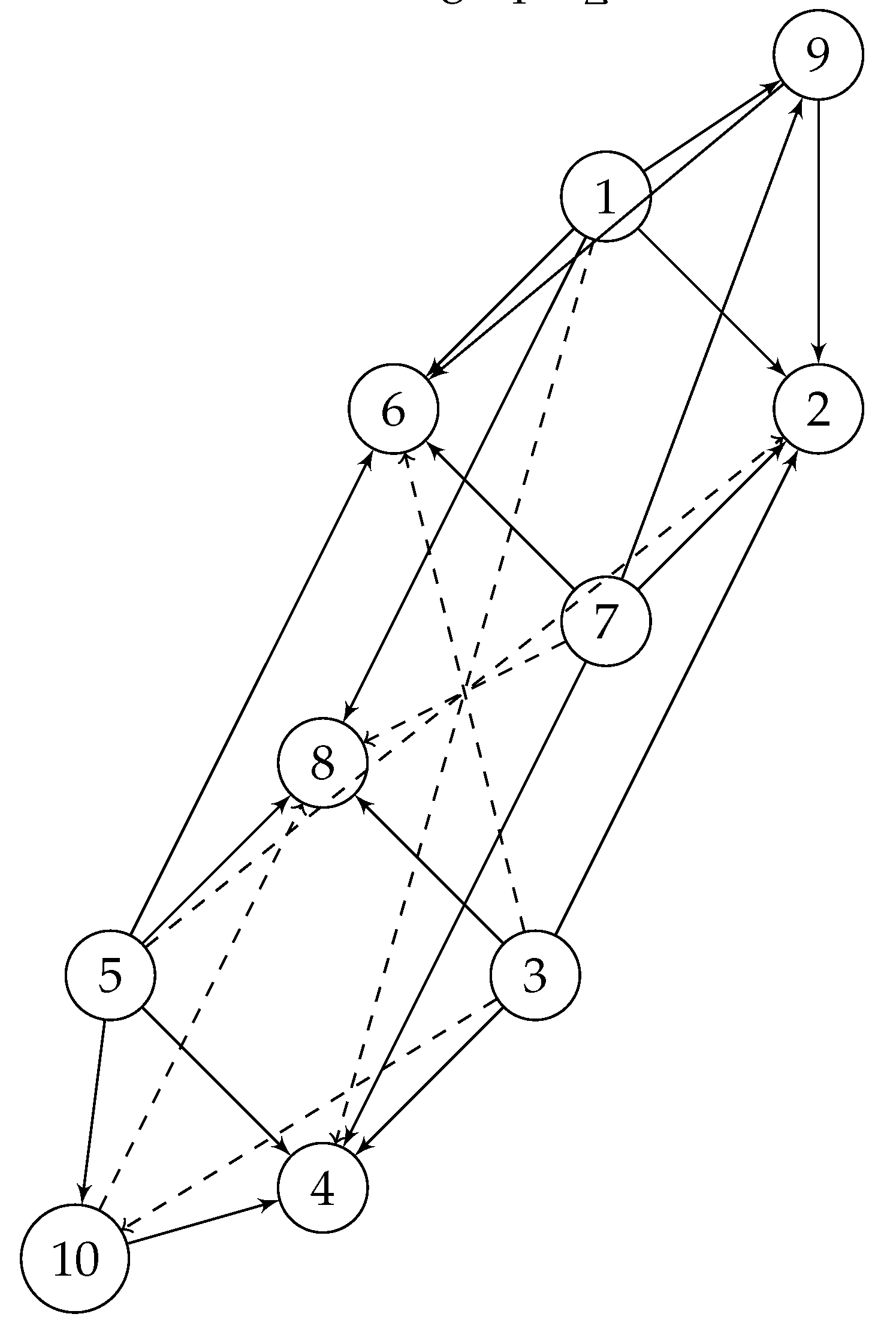

Proposition 3.

The quantum automorphism group of the 4-dimensional Hypercube graph is nontrivial and is equal to .

Proof. The proof will proceed along exactly the same lines as in Propositions 1 and 2.

To do this, we try to have a reasonable orientation on that makes our job a lot easier in finding if possesses quantum symmetries or not! (By the way, we already know that the last statement is true!)

So, consider the orientation imposed in the following way. Note the sink and source vertices!

It is not too difficult to observe that the only projective unitary matrix such that satisfies for the adjacency matrix could be formulated as above, as a generator of the anticommutative quantum group as expected, for and ℓ mutually noncommutative.

In conclusion, one may check the truthfulness of the relation , resulting in the non-triviality of the quantum automorphism group of . □

Remark 3.

- (i)

Note that a one-dimensional Hypercube is a line. A two-dimensional Hypercube is a square. A three-dimensional Hypercube is a cube. A four-dimensional Hypercube is what which is called the Tesseract that consists of two entangled cubes. A five-dimensional Hypercube consists of three entangled cubes and an n-dimensional Hypercube for consists of entangled cubes.

- (ii)

The main generator of the quantum automorphism group of the 3-dimensional Hypercube graph from the Proposition 2 could be identified with the free group generated by , and the main generator of the quantum automorphism group of the 4-dimensional Hypercube graph from the Theorem 3 could be identified with the free group generated by . Following this Alghoritm that has been proven, one may suggest that the main generator of the quantum automorphism group of the 5-dimensional Hypercube graph could be identified with the free group generated by .

- (iii)

For the n-dimensional Hypercube graph , for , we have .

- (iv)

Then one gets that , , and , and the claim is that for we should have .

We can now prove the main result of this section. But before doing so, let us see how one could proceed to as the main generator of the quantum automorphism group of the n-dimensional Hypercube graph .

2.1.1. The Algorithm

In order to generate the generators of or equivalently , we need a process, some sort of an (maybe not exactly) “Algorithm”. We propose the following approach.

Let

be the main generator of the quantum automorphism group of the

n-dimensional Hypercube graph

, that is

Note that the entries of

u belong to the set

for

, and we have

imposed by

u being a projective unitary matrix.

So, starting from the main diagonal of u and the first entry , let , and as we know that there are exactly noncommutative entries for in the associated free group , the process will be as follows.

After

, let

,

,

, and so on till

,

,

, and so on till

,

,

, and we will be done with the diagonal. Then, by using the characteristic

3 one could get the whole matrix. For example, for

we have the following generator of

, for

,

.

which could be quite easily extended to the general case of

for

.

We are almost ready to prove the main theorem of this section that we have already promised.

Theorem 1.

The quantum automorphism group of the i-dimensional Hypercube graph is nontrivial and is equal to for .

Proof. The proof will proceed by induction on i. We have already seen in Propositions 2 and 3 that the induction steps for satisfy. Let us assume that the claim of the Theorem also works for . Then as holds, and we have , then one should easily get the result by employing “the Algorithm”! □

Remark 4.

- (i)

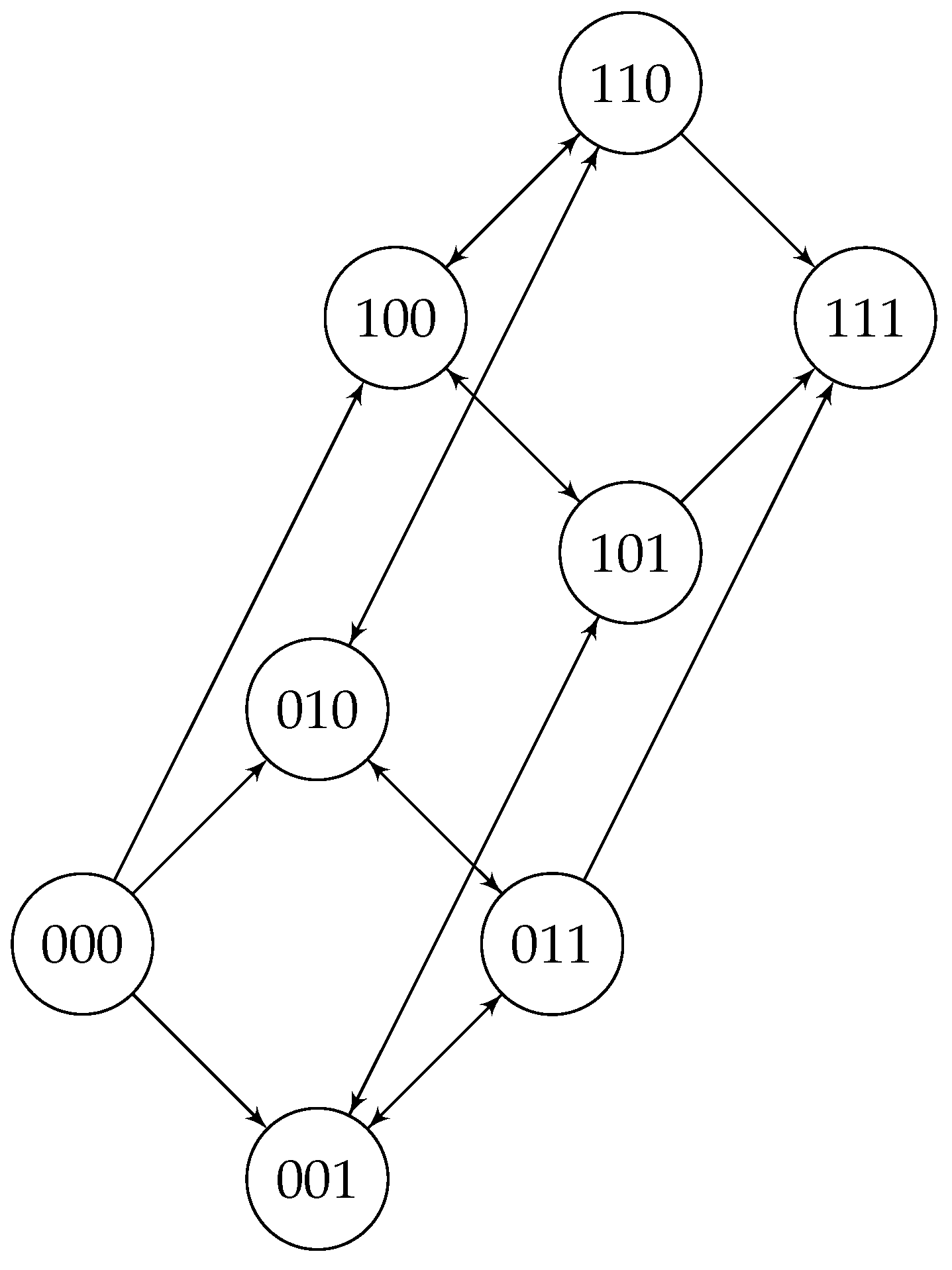

Note that the orientation defined in Section 2.1 is not the only orientation, but somehow it is the best one that suits our purposes for this paper, that is finding out that if the quantum automorphism group of is noncommutative or not. - (ii)

But this orientation is not good for the purposes of the paper [13], because in this case we obtain no Hamiltonian paths, and the paths terminate before reaching the maximum size. - (iii)

-

Let be the set of orthonormal basis of , and in order to fulfill the condition stated in the second part of the current remark b, and as in [17], for let us consider such that and

Definition 2.The orientation on will be defined as follows. Let and be the set consisting of the rest of vertices minus the array with entries all 1, that is .

- (I)

For , if , then the orientation will be .

- (II)

For and , the orientation will be two sided, that is .

- (IIi)

For and as in the statement of Definition 2, the orientation will be .

- (iv)

-

For example in , the orientation will be as follows.

Note that has three distinct Hamiltonian paths.

2.1.2. A Variant of Folded n-Cube Graphs

Cayley graphs associated with

are generally called cubelike graphs as a generalization of the

n-dimensional Hypercube graphs (

n-cube graphs)

for

and

the

standard basis vector of

. In [

12,

17] folded

n-cube graphs

were introduced and studied, which are the

n-hypercube graphs

such that the opposite vertices are connected by an edge.

Definition 3.

For and as above, let be the (not unique) set of generators of . Then the cubelike graph is known as the folded n-cube graph.

Some of the main properties of the folded n-cube graph are listed in the following remark.

Remark 5.

- (i)

is constructed from by connecting the vertices with the maximum distance from each other.

- (ii)

The order of agrees with its degree.

- (iii)

For n an even number, is a bipartite graph and for n an odd number, has vertex chromatic number 4.

- (iv)

is always a distance transitive graph.

The example which we will consider could be set up as a partially folded

n-cube with one face literally less than

. Starting from

. Consider two of its sides opposite to each other, and add equal number of triangles to both of them. This extension could be repeated in many possible steps, say an infinite number and call it

, where

∞ indicates the number of triangles. For example consider

illustrated in

Figure 6.

Lemma 1.

The quantum automorphism group of is noncommutative.

Proof. It is not too difficult to observe that the following matrix is the only noncommutative projective unitary matrix that commutes with the adjacency matrix

of

.

for

. That is

satisfies. □

Claim 5.

The quantum automorphism group of is noncommutative.

Proof. Here we present an idea on how to proceed, and the proof is also a claim!

The claim is that the only noncommutative projective unitary matrix that may commute with the adjacency matrix

has to be the following matrix.

for

. □

Now consider the generalized folded 3-cube graph

, as has been illustrated in

Figure 7.

Remark 6.

- (i)

Note that for , the graphs studied in Claim 5, and their higher orders which will come later, are not exactly the folded n-cube graphs introduced and studied in [12,17], but in some sense could be considered as the generalizations of for . - (ii)

Note that for the folded 3-cube graph , matrix studied in Proposition 2 will also play the role of the main generator of the quantum automorphism group of the folded 3-cube graph .

Proposition 4.

The quantum automorphism group of is noncommutative.

Proof. It is not too difficult to observe that the following matrix is the only noncommutative projective unitary matrix that commutes with the adjacency matrix

of

.

for

as in Proposition 2. That is

satisfies and the quantum automorphism group

is noncommutative. □

Claim 6.

The quantum automorphism group of is noncommutative.

Proof. Here, the same as what we did to present a glimpse of what has to be done in the proof of Claim 5, we once again claim that the only noncommutative projective unitary matrix that may commute with the adjacency matrix

has to be the following matrix.

for

as in the proof of Proposition 2.

□

Claim 7.

Let to be the generalized folded n-cube graph. The claim is that its quantum automorphism group has to be as follows for the adjacency matrix of .

for u defined as in the following noncommutative projective unitary matrix.

for the adjacency matrix of the n-cube graph .

3. Hyperbolic Cayley Graphs

Studying noncommutative properties of (directed) graphs have gained much importance these days, as we observe unpresented progress in the theory of quantum computing, with the story motivated by the following question.[

8]

“What happens when one studies the representation theory of a (directed) graph in a noncommutative algebra?”

The notion of hyperbolicity used in this section is due to Gromov [

11] and is defined as follows.

Definition 4.

[8] For a graph Γ and its set of vertices , let , for , and let

and if for , holds, then define . The hyperbolicity of G, denoted by will be defined as follows.

for d the usual distance metric on a graph.

Remark 7.

- (i)

Graph Γ will be called δ-hyperbolic, for some , if for all , and .

- (ii)

On the other hand, Γ will be called hyperbolic if its hyperbolicity is finite.

- (iii)

Of the graphs with finite hyperbolicity, 0-hyperbolic graphs are of great importance to us, as they are in close relation with block graphs.

Definition 5.

A block graph is a graph all of its blocks are complete graphs.

Remark 8.

- (i)

Almost all trees are considered to be block graphs.

- (ii)

Almost all 0-hyperbolic graphs are considered to be block graphs.

- (iii)

Note that usually, the hyperbolicity of a graph is considered for the non-oriented version.

Example 10.

For example, let us consider the Cayley graph of the free group studied in Proposition 1 and illustrated in Figure 1, that is . But as pointed out in Remark 8c, the hyperbolicity of a graph, mostly studied for the non-oriented versions. However, hopefully, in the case of , the oriented version is also 0-hyperbolic, and it is not too difficult to observe this fact by using the 4-point condition from Definition 4. Note that this coincidence is not an accident. This happened because of the choice of orientation.

Let

and consider the following sets

Remark 9.

Matrices involved in are called cherries! Mono, double, triple cherries, and so on.

Note that

G with its current presentation is not a group, but with some minor changes one might get a group structure. Anyway, instead of doing it so, let us consider the following set

where

A is a block matrix consisting of a

matrix

and a

matrix

. Note that

is a monoid. Now consider

Lemma 2.

For H a subgroup of for , and , consider the following action [15]

Then the claim is that this action keeps unchanged if .

Proof. The proof will follow exactly the approaches used in the proof of Proposition 3.15 from [

15], by getting help from the fact that one may rearrange the main generator

of

using a finite number of elementary row column operators as an element

. □

The main goal of this section is to provide a possible answer to a question raised in [

18], asking “if the unit distance graphs

possess quantum symmetries or not, for

”. However note that our study might not provide a direct answer, but the study could help in reaching to some conclusion!

The plan is to define a (directed) block graph with , meaning that the vertices will be matrices for , and hence we have , and our working space will be infinite dimensional!

Definition 6.

The orientation in will be defined as follows for .

- (i)

For , there will be an oriented edge from B to C or C to B, if or belong to E respectively.

- (ii)

Otherwise there will be no connection between B and C.

Remark 10.

- (i)

Note that by following Definition 6 , we obtain a block graph consisting of disjoint blocks which are n-cube graphs , for , plus an infinite number of isolated vertices!

- (ii)

Note that as stated in [18] and as our method of construction (making these kinds of graphs) presents, n-cubes are considered to be unit distance graphs. - (iii)

In , if we consider the orientation in a way that B and C be connected if , for the identity matrix, then we will obtain a block graph consisting of disjoint union of folded n-cube graphs , for , together with an infinite number of isolated vertices!

- (iv)

-

Also note that the above described process will almost present the nature of quantum permuting and provides us with the sufficient information on how could it be done for an infinite dimensional space by using the structures studied and introduced in [18]!

We will return to this discussion later.

4. Quantum Symmetry Groups of Infinite Dimensional Spaces

We started by looking at the Cayley graph associated with the free group by letting as usual, and by considering the fact that its Cayley graph is a block graph.

Cayley graphs are important because of the bridge they make between group theory and the theory of graphs. Also their importance in our study is providing us with interesting examples in graph theory, on which we call toy examples! However, for the study conducted in this paper, their connection with the n-cube graphs is of immense importance.

Suppose we have given an infinite-dimensional mathematical space. So, it could be the usual Euclidean space , for . Note that for d a complete number for some n, one gets the usual point-wise identification , and likewise for . Hence, it is not far from reality if we consider the initial given space to be the usual matrix space, meaning that to allow matrices to play the role of the points of our space. The plan is to give it a shake, to sit and observe the changes, but as a mathematician!

For finite-dimensional spaces, the trick is to use the (compact) quantum permutation group

. But when our space is no longer finite, there is the so called infinite quantum permutation group

which is a discrete quantum group, studied and introduced in [

18] as the discretization of

.

4.1. Quantum Permutations

Fix a set X. It could be finite or an infinite dimensional set.

For a (locally) compact (quantum) group

G, let

to be the full algebra of the associated functions, and let

be an

matrix with its entries

being orthogonal projections in

, the space of bounded linear operators on

, such that

, called the projective unitary matrix (or the magic unitary matrix). Then one obtains the quantum permutation group

for

, as in [

19].

Definition 7.

The quantum permutation group is the compact quantum group for u a projective unitary matrix, equipped with the usual comultiplication .

Remark 11.

- (i)

Note that is the quantum automorphism group of .

- (ii)

One obtains the injection , and by using the Gelfand spectrum, one gets the corespondent surjection for the Abelianization of .

- (iii)

It is not too difficult to observe that for one obtains , and for , is totally noncommutative.

- (iv)

Note that the noncommutativity of for is examined by observing its main generator , in the case if it is a noncommutative projective unitary matrix.

To continue let us follow the notation used in [

18]. Consider

to be the group of symmetries (permutations) of

X, for

X as before. Note that in [

18] they consider

X to be countable, and the original definition of the projective unitary matrices, stated above, is based on the index set

over the Hilbert space

. So, if one considers an arbitrary set

X and an arbitrary Hilbert space

H, one obtains the quantum permutation of

X defined in [

18] and could be summarized as follows.

Definition 8.

For a set X, its quantum permutation σ is the pair consisting of an underlying Hilbert space and the matrix of projections indexed by X, such that

- (i)

For all , and are pairwise orthogonal projections.

- (ii)

-

satisfies.

Remark 12.

- (i)

The quantum permutation σ defined in definition 8, will also be referred as the magic unitary indexed by X.

- (ii)

When then one obtains the usual magic unitary matrix.

- (iii)

Note that as mentioned before, previously defined magic unitary matrices were known as the projective unitary matrices. But from now on, we will refer to them as the quantum permutation matrices indexed by X, for arbitrary set X.

As stated in [

18], for

X an infinite dimensional set, the free version of

, that is

is a discrete quantum group and one may interpret this statement by saying that

acts discretely. Meaning that in order to study its action on

X, one has to study its action on its set of non-crossing subsets as in Definition 8!

However, to do so, one needs to understand the language of the -tensor categories, which is not included in the goals of this paper. But recall that a -tensor category is a category with Hilbert spaces playing the role of its objects and morphisms are bounded linear maps having a tensor product and a -algebra structure on the morphisms. A -tensor category will be called rigid if each object has a dual.

Remark 13.

Note that there are as many as possible finite dimensional quantum permutations of X as the objects of the rigid -tensor category .

Definition 9.

[18] For X as before, the (discrete) quantum permutation group is obtained from together with its tutological fiber functor via Tannaka-Krein reconstruction.

Remark 14.

Definition 9 could be simplified by phrasing that the underlying -algebra of functions on could be seen as the -direct sum of matrix algebras

over any possible quantum permutation of X.

4.2. Discussion

Following the notations and the constructions from the previous sections, suppose that we are given a set X with a countable number of elements.

Without loss of generality, for simplicity, let us assume that our working space is , meaning that our space consists of points like , for arbitrary matrix and an arbitrary matrix .

Lemma 3.

Following Lemma 2, if we act on , then the following cases might occur.

- (i)

For , and as before, matrices will be kept unchanged.

- (ii)

Let , the null matrix, for . Then matrices will be kept unchanged.

Proof. The proof will follow exactly the same lines as in the proof of [

15]. □

Remark 15.

- (i)

Note that this paper will be mostly concerned with the second case in Lemma 3, since these kinds of block matrices could be easily identified with for . However, the general case will also work!

- (ii)

By using the first part of the current remark, one may extend the orientation defined in Definition 2 in order to obtain a disjoint union of n-cube graphs, for , together with an infinite number of isolated vertices!

4.2.1. A False Attempt, as a Small Portion of Unit Distance Graphs

As mentioned before, there is an open problem raised in [

18] asking if in general, the unit distance graphs

for

possess quantum symmetries. This is an

problem with few known possible examples, from which one may outline the line graph

(the unit distance graph for

), the hypercube graphs, and the cycle graphs. However, the process introduced in this paper might provide a road, almost a paved one, to study this problem, hopefully!

Returning to the main purpose of this paper, which was to study the quantum permutations of , let us use the extended version of the orientation introduced in Definition 2, recalled in Remark 15b, and obtain a set of structures consisting of an infinite number of isolated vertices and a disjoint union of n-cube graphs, for , and let us call it , and to present the disjoint union of n-cube graphs with .

Concerning the following lemma, and the free product between quantum groups, the interested reader is referred to the section 9 of [

16].

Lemma 4.

for the set of isolated vertices, and * the free product.

Proof. Since our space is divided into disjoint union of

n-cube graphs, for

, and an infinite number of isolated vertices, therefore, by following section 5 of [

1], and the results obtained in [

16], we know that for a disjoint union of pairwise non-quantum isomorphic connected graphs

, the quantum automorphism group of the union will be identified by the free product of the quantum automorphism group of the individual participated graphs

.

We also know that the quantum automorphism group of a null graph

with infinite number of isolated vertices will be identified by

which is a (discrete) quantum group, and the quantum automorphism group of disjoint union of

j-cube graphs

, for

, will be the direct free product

for

the associated quantum hyperoctahedral groups as the quantum automorphism group of

i-cube graph

.

In summation the desired result will follow!

□

•Please note that this study still is not completed!

5. Concluding Remarks

As a generalization of compact (matrix) groups in noncommutative geometry, in 1987, compact (matrix) quantum groups (

CQG) came into reality by Woronowicz [

20], and later on in 1988, one of the most important tools in studying

CQGs, that is the monoidal *-category of representations and intertwiners introduced in [

21] as a generalization of the Tannaka-Krein duality. Following Woronowicz’s works and as a result of an attempt in answering a question raised by Connes, asking the possibilites of quantization of the usual permutation groups

in the category of quantum groups, and in search of quantum symmetries, Wang came with a sharp sophisticated answer emphasizing that following the construction from compact (matrix) group

G to compact (matrix) quantum group

by using the coordinate functions

, for

the coordinate algebra generated by

, the quantum permutation group

is the compact (matrix) quantum group

based on the Gelfand-Naimark construction and the Gelfand spectrum.

Later on, as a result of Wang’s construction and the Frucht theorem on the existence of simple finite graph for a given finite group, and its quantum version, quantum symmetries of graphs have been introduced and studied in [

3,

6] as a generalization of the classical symmetric group of graphs as an invariant space.

• But why all of these are important?

Note that, maybe the current paper is a wrong place to look for an answer to the above mentioned question! But however, what we can say is that graphs with quantum symmetries have shown possessing interesting properties. For instance, the quantum automorphism groups of (directed) graphs on

n vertices with quantum symmetries, are noncommutative, and as a quantum subgroup of

, they might provide us with new examples of compact, or discrete quantum groups (discrete for the case where the number of vertices is infinite [

18]).

On the other hand, in our previous works [

13,

14,

15,

16], we have shown that (directed) locally finite graphs with quantum symmetries might provide us with entangled quantum systems as in [

16], where the associated quantum systems with set of directed graphs

for

are entangled! However, the importance of examples like

other than having physical applications is their relation with quantum hyperoctahedral groups as the quantum automorphism group of the

n-cube graphs, which could be studied as Cayley graphs with vertices belonging to

, making a small portion of unit distance graphs; and this was almost the main purpose of this paper!

Summarized, we tried to find out about main generators and the quantum automorphism groups of some certain (directed) Cayley graphs with infinite number of vertices, in order to study the problem concerned with the quantum symmetric group of an infinite dimensional space, also studied in [

18], and the open problem concerning the unit distance graphs, also with the same reference!

However, our study still is not completed as working with disjoint union of graphs cannot provide us with the desired vision!

So, the future plan could be to try to partially answer the following question quoted from [

18].

“Do, in general, unit distance graphs for , possess quantum symmetries?”

Acknowledgments

The author is partially supported by a grant from the Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (IPM), with grant No. 1404140052.

References

- Árnadóttir, Árnbjörg Soffía, Josse van Dobben de Bruyn, Prem Nigam Kar, David E. Roberson, and Peter Zeman. Quantum Sabidussi’s Theorem. 2024; arXiv:2402.12344.

- S. A. Atserias, L. Mančinska, D. Roberson, R. Samal, S. Severini, and A. Varvitsiotis. Quantum and non-signalling graph isomorphisms. Journal of Combinatorial Theory,Series B, 136:289–328, 2019.

- Teodor Banica. Quantum automorphism groups of homogeneous graphs. Journal of Functional Analysis, 224(2):243–280, 2005.

- Banica, Teodor, Julien Bichon, and Benoıt Collins. Quantum permutation groups: a survey. arXiv preprint math/0612724 (2006).

- Banica, Teodor, Julien Bichon, and Benoıt Collins. The hyperoctahedral quantum group. arXiv preprint math/0701859 (2007).

- Julien Bichon. Quantum automorphism groups of finite graphs. Proceedings of the Americal Mathematical Society, 131(3):665–673,2003.

- J. Bichon, Free wreath product by the quantum permutation group, Alg. Rep. Theory 7 (2004), 343–362.

- Freslon, Amaury, Paul Meunier, and Pegah Pournajafi. Noncommutative properties of 0-hyperbolic graphs 2025. arXiv:2504.13808.

- Gromada, Daniel. Presentations of projective quantum groups. Comptes Rendus. Mathématique 360, no. G8 (2022):

899-907

.

- Gromada, Daniel. Quantum symmetries of Cayley graphs of abelian groups. Glasgow Mathematical Journal 65, no. 3 (2023): 655–686.

- M. Gromov. Hyperbolic Groups, pages 75–263. Springer New York, New York, NY, 1987.

- Mančinska, Laura, Irene Pivotto, David E. Roberson, and Gordon F. Royle. Cores of cubelike graphs. European Journal of Combinatorics 87 (2020): 103092.

-

Razavinia, Farrokh.A route to quantum computing through the theory of quantum graphsarXiv preprint arXiv: 2404.13773 (2024).

- Razavinia, Farrokh. C*-Colored graph algebras. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2504.16963.

- <i>Razavinia, F. A Remark on the Actions of C(Sn+). Preprints 2025, 2025081132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- <i>Razavinia, F. Symmetrizable Versus Quantum Symmetrizable Graphs. Preprints 2025, 2025090247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Simon. Quantum automorphisms of folded cube graphs. In Annales de ĺInstitut Fourier, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 949-970. 2020. .

- Voigt, Christian. Infinite quantum permutations. Advances in Mathematics 415 (2023): 108887.

-

Wang, S. Quantum symmetry groups of finite spaces.Commun. Math. Phys., 1998,195:195–211.

-

Woronowicz, S. L. Compact matrix pseudogroups.Commun. Math. Phys., 1987,111:613–665.

-

Stanislaw L. Woronowicz. Tannaka-Krein duality for compact matrix pseudogroups. Twisted SU(N) groups.Inventiones mathematicae, 93(1):35–76,1988.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).