Active learning strategies have increasingly been recognized as vital for improving student engagement and motivation in science education. In zoology classrooms, where theoretical knowledge often dominates instruction, students may struggle to maintain interest and connect concepts to real-world biological processes. Hands-on activities such as dissections, model construction, and experiments provide tangible experiences that promote curiosity and deeper understanding. Freeman et al. (2014) emphasize that these approaches can enhance participation and conceptual retention by linking theory to practice. Similarly, Prince (2004) noted that active learning enhances cognitive participation and helps students retain complex scientific information through direct interaction with materials and peers.

Motivation plays a central role in learning outcomes, influencing attention, effort, and persistence (Ryan & Deci, 2017). When students are actively involved in constructing knowledge through experiential tasks, they are more likely to develop intrinsic motivation and report higher academic satisfaction, as discussed by Biggs et al. (2022). In Pakistan, traditional lecture-based methods remain prevalent in zoology instruction, limiting opportunities for inquiry-based exploration. For example, Sukkurwalla et al. (2024) found that medical educators in Karachi reported reliance on teacher-centred pedagogies and highlighted the need for student-centred, interactive approaches.

This study aims to explore the impact of hands-on activities on student engagement and motivation in zoology classes within a private college in Karachi. By comparing students’ engagement and motivation before and after the implementation of practical activities, the research seeks to determine whether such interventions enhance learning experiences and foster positive attitudes toward zoology. The findings may contribute to developing evidence-based pedagogical strategies that make zoology more engaging, relatable, and effective in the Pakistani educational context.

Problem Statement

Traditional zoology instruction in Pakistani colleges relies heavily on lectures and textbook-based teaching, which often leads to low student engagement and motivation. Although a few studies have explored active learning in science classrooms, most have focused on cognitive achievement rather than affective factors such as engagement and motivation. As a result, there is a lack of experimental evidence examining how hands-on, inquiry-based activities influence students’ behavioral and emotional involvement in zoology. This study therefore seeks to determine whether implementing practical zoology activities can meaningfully enhance student engagement and motivation in the college context.

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of hands-on zoology activities on students’ engagement and motivation.

To compare pre- and post-intervention scores and triangulate findings with observational and qualitative data.

Research Questions

Does the implementation of hands-on zoology activities significantly enhance student engagement?

Does participation in hands-on zoology tasks lead to greater student motivation compared to traditional instruction?

Hypothesis

H0 (Null Hypothesis): There is no significant difference between pre-test and post-test scores of engagement and motivation after the hands-on activities.

H1 (Alternative Hypothesis): There is a significant increase in engagement and motivation scores following the hands-on activities.

Literature Review

Introduction

Hands-on learning in biology including dissections, model-building, microscopy, and simple experiments is widely recognized for enhancing engagement, motivation, and conceptual understanding. Syntheses indicate that well-designed practical inquiry yields both cognitive (conceptual and procedural) and affective (motivational and emotional) gains, though benefits depend on task clarity, scaffolding, teacher proficiency, and context (Oliveira & Bonito, 2023). This review (2016–2025) examines the effects of hands-on activities in biology and zoology education, critiques methodological strengths and weaknesses, and highlights implications for a private-college zoology classroom in Karachi.

Empirical Evidence: Cognitive Gains, Engagement, and Motivation

Multiple quasi-experimental studies report that structured hands-on experiences improve conceptual understanding and procedural skills (Yoon et al., 2024), though most are small-sample classroom trials rather than randomized designs, which restrict causal inference. Meta-analytic evidence shows moderate effect sizes when tasks are clearly aligned with learning goals and include reflection (Lazonder & Harmsen, 2016), representing one of the more robust and generalizable sources of evidence in this domain. However, some studies find that virtual simulations can produce comparable conceptual gains, suggesting that the design quality of the activity rather than physical manipulation per se determines learning outcomes (Yun et al., 2024).

Affective outcomes consistently show greater interest, enjoyment, and persistence after hands-on interventions (Wang et al., 2019), although many rely on short-term self-report data without behavioral validation. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory, activities that support autonomy, competence, and relatedness enhance intrinsic motivation and sustained engagement (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Studies using combined self-report, observation, and performance measures report stronger, more credible engagement gains (Rosen & Kelly, 2023), indicating higher methodological rigor and ecological validity.

Across these studies, evidence strength varies considerably. Meta-analyses and large-scale reviews (e.g., Lazonder & Harmsen, 2016) provide more robust conclusions about general effectiveness, whereas small quasi-experimental or classroom-based studies (e.g., Yoon et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2019) illustrate context-specific patterns but have limited external validity. Recognizing these distinctions clarifies that reported gains should be interpreted as moderate and conditional rather than universally generalizable.

Mechanisms Linking Hands-On Work to Engagement

Four mechanisms explain these outcomes:

Embodied Sense-Making

Direct interaction with specimens or models reduces abstraction and strengthens mental representation (Mansour et al., 2024), a primarily cognitive mechanism supported mainly by qualitative or small-scale studies rather than controlled trials.

Perceived Relevance and Autonomy

Inquiry and decision-making foster ownership and intrinsic motivation (Marley et al., 2022), though sustained effects beyond the short term remain underexplored.

Social Scaffolding

Collaborative labs encourage peer questioning and active learning, enhancing both engagement and understanding (Oliveira & Bonito, 2023), with most supporting data derived from observational rather than experimental designs.

Confidence Through Practice

Repeated procedural experience builds self-efficacy and procedural fluency (Al Gharibi et al., 2021), though generalization across topics and cohorts is uncertain due to limited replication.

Critical Limitations and Methodological Gaps

The evidence base remains dominated by small-sample and quasi-experimental studies, limiting generalizability. Randomized controlled trials are rare, leaving room for maturation and expectancy biases (Tindan & Anaba, 2024). Engagement and motivation are measured inconsistently across studies, using diverse scales with varying reliability (Johar et al., 2023). Reporting of Cronbach’s alpha and triangulated methods remains uneven, reducing comparability. Few studies explicitly test mediating variables like teacher scaffolding or resource quality, which could clarify causation. Resource availability serves as a moderating factor, with well-equipped settings consistently outperforming under-resourced ones (Islam et al., 2024).

Ethical and Logistical Constraints: Dissection and Alternatives

While dissection supports anatomical learning (a cognitive gain), it raises ethical and affective concerns among students (Comer, 2022; Kalınkara, 2024). Virtual and 3D alternatives can yield similar conceptual understanding and minimize distress (Emadzadeh et al., 2023), though comparative evidence remains limited in sample diversity and duration. Best practice involves informed consent, emotional preparation, and optional participation where feasible (Yun et al., 2024).

Measurement Reliability and Reporting

Recent studies emphasize transparent reporting of reliability, effect sizes, and triangulated data. Appropriate use of paired-sample t-tests, Cohen’s d, and Cronbach’s alpha strengthens interpretability and replication (Taber, 2018). When such metrics are omitted, findings lose validity and cannot be meaningfully compared (López-Nicolás et al., 2022). Overall, methodological transparency remains uneven across studies, underscoring the need for standardized reporting frameworks.

Implications for a Private-College Zoology Class in Karachi

Align practical tasks with explicit cognitive and affective learning outcomes supported by structured reflection.

Offer multiple modalities—model-building, microscopy, and virtual alternatives—to balance resource constraints with engagement.

Use mixed evaluation methods combining validated scales and observation for reliability.

Provide teacher training in inquiry pedagogy, safety, and ethical handling of specimens.

Adopt cost-effective substitutes such as plastinated specimens and digital tools for sustainability.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Local quasi-experimental research in Pakistan remains scarce; pre-registered, longitudinal designs are needed (Alam & Rahman Forhad, 2023). Future work should explore whether motivational gains translate into sustained academic or career interest and examine the mediating role of teacher scaffolding (Acosta-Gonzaga & Ramirez-Arellano, 2022). Despite substantial international evidence linking hands-on learning to improved engagement and motivation, there remains a distinct gap in context-specific empirical research within Pakistani Intermediate zoology classrooms. No prior studies have systematically measured both cognitive and affective outcomes of dissection-based and model-building activities using validated engagement and motivation scales. Given logistical and ethical constraints in educational settings, a quasi-experimental repeated-measures design represents the most appropriate and feasible minimum standard; it allows comparison of pre- and post-intervention data within the same group, controlling for intergroup variability without requiring random assignment. This study further contributes to the literature by incorporating a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative survey data with structured classroom observations. Observer triangulation strengthens internal validity, ensuring that reported engagement gains reflect genuine behavioral and motivational change rather than self-report bias.

Conclusion

Since 2016, research has shown that hands-on activities can enhance engagement, motivation, and understanding in biology provided implementation is well-scaffolded, ethically sensitive, and properly evaluated. For Karachi’s private colleges, integrating low-cost practical work, clear learning alignment, and multiple modalities offers a feasible pathway to replicating these positive outcomes.

Methodology

The research adopted quasi-experimental action research design approach employing a quasi-experimental pre-test and post-test design. Action research was chosen because it enables the teacher-researcher to systematically reflect on and improve classroom practices through active intervention (Kemmis at al., 2014). Participants were selected using purposive sampling from two sections of the same college. A group of 40 students participated to evaluate changes in engagement and motivation following a series of hands-on zoology activities. To strengthen the design and allow comparative analysis, a non-equivalent control group was also included. The control group (n = 40) consisted of students from a parallel section of the same private college, following the same zoology syllabus but taught through conventional lecture-based methods without the intervention. The experimental group (n = 40) participated in the hands-on learning intervention, while the control group received identical instructional time and assessment schedules. Both groups were comparable in academic background and prior achievement, enabling reliable between-group comparisons of engagement and motivation.

A 20-item Likert-scale questionnaire was used to measure students’ engagement and motivation. The instrument was adapted from prior active learning and Self-Determination Theory frameworks. The scale comprised two subscales: engagement (14 items) and motivation (6 items), each designed to capture distinct behavioral and affective components. Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Baseline classroom observations were also conducted by the researcher, who served as the teacher-observer, using a structured Observation Checklist. Content validity was established through expert review by two senior biology teachers and one education specialist, who confirmed alignment with engagement constructs used in prior studies. The checklist assessed five behavioral dimensions, each rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very low occurrence, 5 = very high occurrence):

Attentiveness: level of focus during explanations and demonstrations.

Participation: frequency and quality of verbal or practical contribution during tasks.

Questioning Behavior: initiative in asking relevant or exploratory questions.

Peer Collaboration: degree of cooperation, sharing, and joint problem-solving.

Confidence and Independence: ability to perform tasks with minimal teacher assistance.

Each observation session recorded average ratings across these criteria to track behavioral engagement over time.

Weeks 2-3 involved dissection activities, where students performed frog and cockroach dissections under guided supervision. Observations during these sessions focused on teamwork, independence, and procedural accuracy. Weeks 4-5 were devoted to experimental activities, particularly identifying blood groups using anti-sera, emphasizing curiosity, precision, and safety skills. Weeks 6-7 centered on model-building, with students constructing and analyzing structural models of the human skeleton, heart, and kidney to promote conceptual understanding and creative engagement. Finally, in Week 8, the post-assessment was administered using the same 20-item questionnaire to measure changes in engagement and motivation. Observations were conducted by teacher, co-teacher and laboratory assistant throughout all phases (pre, during, and post) to capture behavioral growth over time.

Fidelity of Implementation

To ensure consistency, the researcher followed a structured activity plan with identical instructions, duration, and assessment rubrics across all groups. Each session was monitored for timing, task completion, and student participation. Reflective field notes were maintained after every activity to document instructional adjustments and student responses. Though each phase lasted roughly two weeks, activities were implemented twice weekly to ensure sufficient exposure and practice.

Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected through two main instruments:

Self-developed Likert-scale questionnaire, which included items such as “I feel excited to attend zoology class” and “I actively participate in class activities,” designed to capture both affective and behavioral dimensions of learning.

Observation checklist, which recorded indicators of engagement, curiosity, confidence, and peer interaction during each session.

Instrument Development and Validation

The 20-item Engagement and Motivation Questionnaire was adapted from established student engagement frameworks (Fredricks et al., 2004; Reeve & Tseng, 2011) and contextualized for zoology practical learning. Items were generated to represent four theoretically grounded domains: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement, and motivation. To ensure content validity, the initial draft was reviewed by two experienced biology teachers and one educational measurement specialist, who rated item clarity and relevance. Minor wording adjustments were made based on their feedback. The refined version was pilot-tested with 10 students from a similar class to confirm clarity and response consistency. Although no exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis (EFA/CFA) was performed due to sample size limitations, internal consistency reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha for engagement and motivation subscales.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS (Version 26). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) summarized the pre- and post-assessment scores. A paired-sample t-test determined whether the changes between pre- and post-scores were statistically significant. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to estimate the magnitude of improvement, while Cronbach’s alpha assessed internal reliability of the questionnaire. Qualitative data from observation notes and student reflections were analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns related to participation, enthusiasm, and collaboration.

In addition to paired-sample t-tests comparing pre- and post-test scores within the experimental group, independent-sample t-tests were conducted to compare post-test outcomes between the experimental and control groups. This approach allowed assessment of whether the hands-on intervention led to significantly higher engagement and motivation relative to a non-intervention group. All assumptions for t-tests, including normality and homogeneity of variances, were checked prior to analysis.

To ensure objectivity in observational data, inter-rater reliability for the Classroom Observation Checklist was assessed. Three independent observers (the teacher, co-teacher, and laboratory assistant) rated student engagement behaviors during the pre-, during-, and post-activity phases. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was computed using a two-way random-effects model with absolute agreement. The resulting ICC (2,3) = .988, 95% CI [.963, .997], indicated excellent agreement among raters (Koo & Li, 2016), confirming the reliability of the observational measures.

Open-ended feedback (Section C) and observation notes were analyzed thematically using inductive coding. Responses were coded by two raters independently and reconciled through discussion. Coding continued until no new themes emerged (theme saturation reached at the 28th response). A summary of major codes, representative quotes, and saturation criteria is provided in

Appendix B.

Limitations of the Design

As an action research study without a control group, the design is vulnerable to the Hawthorne effect and maturation effects. Although triangulation of data strengthened credibility, future studies could employ a non-equivalent control group or randomized design to enhance causal inference. Despite these constraints, the repeated-measures approach and consistent implementation across sessions provided sufficient internal validity for interpreting within-group changes.

Triangulation and Validity

Triangulation across quantitative scores, qualitative observations, and student reflections allowed for a comprehensive understanding of engagement and motivation. Cross-validation between self-report and observed behavior increased the reliability of conclusions regarding the effectiveness of hands-on learning strategies in zoology education.

Ethical Considerations

The dissection activities in this study were carried out as part of the officially prescribed Zoology practical curriculum under the Board of Intermediate Education, Karachi. As dissections constitute a mandated component of the Intermediate syllabus, no separate ethical approval was required. Nevertheless, all activities were conducted in accordance with standard laboratory safety and ethical guidelines. Students were instructed on specimen handling, responsible disposal practices, and the educational purpose of dissections. Written consent was also obtained from all participating students prior to collecting reflection responses. Participation in reflections was voluntary, and students were informed that their feedback would be anonymized and used solely for academic improvement and research reporting.

Results

Table 1 indicates that both engagement and motivation significantly increased in the experimental group following the hands-on learning intervention,

t (39) = 4.70,

p < 0.001, and

t (39) = 3.79,

p = 0.001, respectively. Although the control group also showed a statistically significant but small increase in engagement (

t (39) = 5.23,

p < 0.001), the change in motivation was not significant (

p = 0.119). Together, these results suggest that hands-on learning meaningfully improved both behavioral and emotional engagement in zoology, beyond what occurred in traditional instruction.

Table 2 shows that between-group analysis confirmed that improvements in engagement and motivation were

significantly greater for students in the hands-on learning condition.

Two related dependent variables (engagement and motivation) were analyzed using separate paired-sample t-tests. Because only two primary outcomes were tested and both were theoretically grounded and pre-specified, no formal correction for multiple comparisons was applied.

In

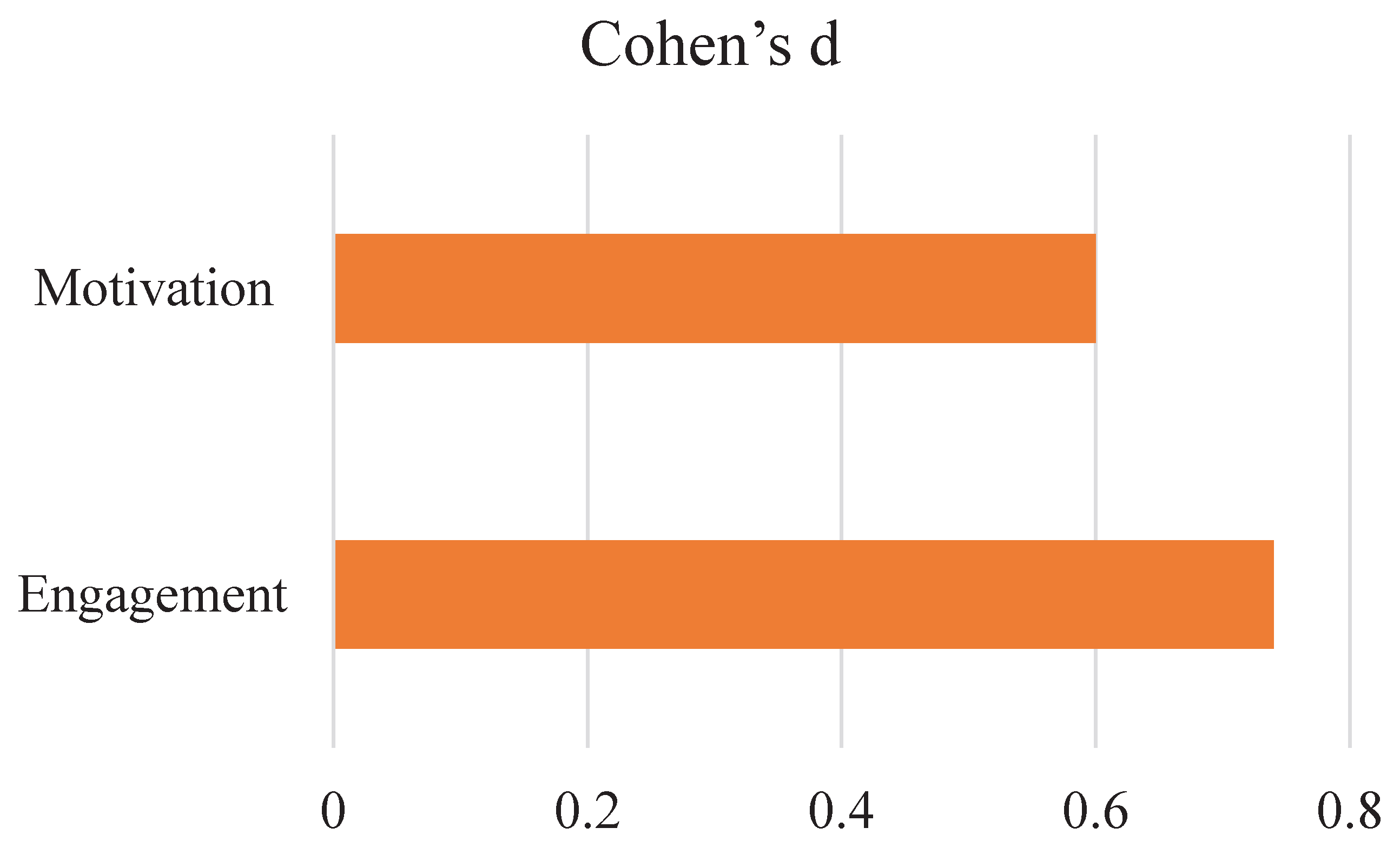

Figure 1 the large effect sizes indicate that the intervention produced substantial educational gains. These results show that hands-on learning not only improved observable classroom engagement but also boosted students’ internal motivation toward zoology.

Internal consistency for both subscales was acceptable to excellent, with α values ranging from 0.802 to 0.851. These coefficients indicate that the engagement (14 items) and motivation (6 items) scales reliably measured the intended constructs across both pre- and post-tests.

Table 3.

Internal Consistency Reliability of Engagement and Motivation Scales (Pre and Post).

Table 3.

Internal Consistency Reliability of Engagement and Motivation Scales (Pre and Post).

| Scale |

Number of items |

α (Pre) |

α (Post) |

| Engagement |

14 |

0.847 |

0.812 |

| Motivation |

06 |

0.802 |

0.851 |

Observation and Qualitative Analysis

Observation data were collected collaboratively by three observers; the teacher-researcher, a laboratory assistant, and a co-teacher to minimize observer bias and enhance reliability. Observers used a structured checklist rating behaviors (1-5) on specific indicators such as attentiveness, participation, curiosity, confidence, and peer interaction.

Open-ended responses were analyzed using thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework. Two researchers (the primary investigator and one peer reviewer familiar with biology education) independently reviewed all responses to ensure interpretive consistency.

Coding process: Initial open coding was performed to identify recurring ideas related to engagement, motivation, and perceptions of hands-on activities. Codes were then grouped into broader categories (e.g., Enjoyment and curiosity, Active participation, Improved understanding, Practical challenges). Through iterative refinement and discussion, a final codebook was developed.

Reliability: Disagreements in coding were discussed until consensus was reached. Inter-coder agreement for major categories was approximately 85%.

Software and output: Coding was conducted manually using Microsoft Excel (no specialized software).

Illustrative quotes: Representative student quotations were included in the Results section to support each major theme.

Theme saturation: Saturation was achieved when no new themes emerged after the first 35 of 40 responses.

Table 4 illustrates that observation scores rose markedly during hands-on sessions, especially in the experiment and dissection phases. Students were more attentive, collaborated actively, and showed enthusiasm through gestures and verbal engagement. The slight decline in the post-phase likely reflects the return to regular instruction, yet levels remained above baseline.

Table 5 shows inter-rater reliability which was examined using a two-way random-effects model of absolute agreement among the three observers (teacher, co-teacher, and lab assistant). The analysis yielded an ICC (2, 3) of 0

.988 (95% CI [.963, .997]) for average measures, indicating excellent agreement across raters. The single-measure ICC was 0

.965 (95% CI [0.897, 0.991]), reflecting high reliability even for individual raters. These results confirm the consistency and dependability of the observation ratings throughout all phases of the intervention.

Table 5.

Inter-rater reliability for Classroom Observation Checklist using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC).

Table 5.

Inter-rater reliability for Classroom Observation Checklist using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC).

| ICC Type |

Intra-class Correlation |

95% Confidence interval |

| Single Measures |

0.965 |

0.897-0.991 |

| Average Measures |

0.988 |

0.963-0.997 |

Table 6.

Qualitative Summary of Key Behavioral and Affective Themes Observed During Activities.

Table 6.

Qualitative Summary of Key Behavioral and Affective Themes Observed During Activities.

| Theme |

Evidence from Observations |

| Active Participation |

Students increasingly followed instructions independently and stayed focused (“We can do this ourselves now”) |

| Peer Collaboration |

Cooperative learning strengthened; peers shared materials and offered guidance (“You try holding it this way”) |

| Curiosity & Questioning |

Students displayed greater exploratory behavior, asking questions like “What happens if we add more drops?” |

| Confidence & Independence |

Many began checking instructions and handling specimens confidently without assistance. |

| Positive Emotions |

Smiles, laughter, and comments such as “This is fun!” indicated emotional engagement and satisfaction |

Table 7.

Triangulation of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings.

Table 7.

Triangulation of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings.

| Data source |

Key Finding |

Convergent Evidence |

| Survey (Quantitative) |

Large increase in engagement (d = 0.743) and motivation (d = 0.600) |

Confirms behavioral and emotional gains |

| Observations (Qualitative) |

Higher attentiveness, participation, and curiosity |

Matches quantitative rise in engagement |

| Student Reflections |

Reported “better understanding” and “fun learning” |

Supports affective (motivation) increase |

Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative evidence in

Table 8 confirmed strong convergence across data sources. Quantitative increases in engagement and motivation were supported by observational and reflective data, reinforcing the conclusion that hands-on zoology activities substantially enhanced both behavioral and emotional learning outcomes.

Conclusion

The findings provide strong empirical evidence that hands-on learning through dissections, experiments, and model-building substantially enhances student engagement and motivation in zoology education. Quantitative results demonstrated significant pre- to post-test gains for the experimental group, while the control group showed only minor or nonsignificant changes. The large effect sizes for engagement (d = 0.74) and motivation (d = 0.60) indicate that the intervention produced both statistically and educationally meaningful improvements. The consistently high internal reliability of the engagement (α = 0.847-0.812) and motivation (α = 0.802-0.851) subscales confirms that the instruments used were psychometrically sound and stable across measurement points.

Observation and qualitative data further validated these quantitative outcomes. Students in the experimental group demonstrated higher levels of attentiveness, curiosity, and collaboration, with visible increases in confidence and enjoyment during practical sessions. The inter-rater reliability of the observation checklist was excellent (ICC = .988), ensuring that improvements in observed behaviors were consistently identified by all observers. Thematic analysis revealed recurring patterns of active participation, peer support, and emotional engagement, aligning closely with survey trends.

Triangulation of data sources confirmed strong convergence between numerical and narrative evidence. Survey results, classroom observations, and student reflections collectively pointed to meaningful behavioral and affective gains driven by experiential learning. The slight ceiling effect observed in the model-building phase suggests that engagement levels were already high prior to the intervention, potentially limiting detectable post-phase increases. This highlights the need for more sensitive rating scales or expanded behavioral indicators in future research.

Overall, this study reinforces the pedagogical value of experiential and student-centered approaches in science education. By transforming passive instruction into participatory exploration, hands-on zoology activities foster sustained curiosity, self-confidence, and conceptual understanding. These findings are consistent with international research (Freeman et al., 2014; Prince, 2004) and contribute locally relevant evidence from Pakistan’s secondary education context. Future studies should investigate the long-term persistence of these motivational gains and their influence on continued interest or achievement in the biological sciences.

Author Contributions

Muhammad Zeeshan Rub is a Biology teacher in Karachi with over a decade of experience. He holds a Master’s in Physiology and a Post-Graduate Diploma in Educational Leadership and Management. His research interests include adolescent and mental health, educational leadership, management, and educational technology.

Funding

This study was conducted independently. No funding was received, and the author declares no conflicts of interest. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Appendix A

Research Instruments and Validation Process

Student Engagement and Motivation Questionnaire (20 items)

Section A – Demographics

Roll No. / ID: ___________

-

Age:

-

Gender:

Class/Program: ___________

-

Previous Biology Grade (last term):

Have you done dissections or lab activities before this unit? □ Yes □ No

Section B - Engagement & Motivation (Likert Scale)

Instruction: For each statement, circle one option:

1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree.

Behavioral Engagement

B1. I paid attention during zoology lessons.

B2. I actively took part in class activities and discussions.

B3. I completed class tasks on time.

B4. I collaborated with my classmates during activities.

B5. I asked questions when I didn’t understand something.

B6. I stayed on task during hands-on work.

Emotional/Affective Engagement

B7. I enjoyed zoology classes.

B8. I felt excited to come to zoology class.

B9. The hands-on activities made the class more interesting.

B10. I felt connected with what we were learning.

Cognitive Engagement (effort/strategy)

B11. I tried to relate new zoology ideas to what I already know.

B12. I put effort into understanding difficult concepts.

B13. I reviewed my work to check my understanding.

B14. I used evidence/observations to support my answers.

Motivation (value, interest, self-efficacy)

B15. Learning zoology is valuable for me.

B16. The activities helped me understand zoology better.

B17. I feel confident I can do well in zoology.

B18. I want to learn more about animal structure and function.

B19. I would choose similar hands-on activities again.

B20. I am motivated to study zoology outside class time.

Rubrics/ Scoring & Subscales (for analysis)

Total Engagement = mean of B1–B14; Total Motivation = mean of B15–B20.

Appendix B

Table 8.

Thematic Codes and Illustrative Quotes.

Table 8.

Thematic Codes and Illustrative Quotes.

| Theme |

Code |

Definition |

Example Student Quote |

Evidence Source |

Saturation Notes |

| Increased engagement |

Active participation |

Student describes hands-on involvement or focus during practical work |

“I stayed focused during the dissection and wanted to see how the organs connect.” |

Feedback C2 / Observation note |

Emerged in first 10 responses; stable by 20 |

| Enjoyment and motivation |

Enjoyment/excitement |

Expressions of enjoyment, curiosity, or eagerness |

“The model-building was fun—I didn’t even notice time passing.” |

Feedback C1, C2 |

Repeated across 70% responses |

| Conceptual understanding |

Improved understanding |

Mentions of learning or understanding anatomy better through activity |

“I finally understood how the heart chambers work after seeing the specimen. |

Feedback C4 |

Emerged early; saturated by 25th |

| Collaboration |

Peer cooperation |

References to teamwork, group support, or shared tasks |

“We divided the steps and helped each other.” |

Observation checklist B4–B5 |

Consistent across activities |

| Challenges |

Difficulty/confusion |

Mentions of discomfort, difficulty, or lack of clarity |

“The smell of the specimen was disturbing,” or “I wasn’t sure how to label structures. |

Feedback C3 |

Minor, saturated by 30th |

Suggestions for improvement

|

Improvement ideas |

Student suggests changes in materials or time |

“We needed more time to finish the experiment.” |

Feedback C5–C6 |

New ideas stopped by 35th |

Appendix C

Classroom Observation Checklist

Purpose: Track observable engagement behaviors before (baseline) and during the intervention, and at post-test.

Rating scale (class-level tallies):

1 = Not observed, 2 = Rarely (<25%), 3 = Sometimes (25–50%), 4 = Often (51–75%), 5 = Very Often (>75%)

A. Attentiveness

1. Orients to task/instructions promptly (looks at specimen/model, follows steps).

2. Maintains focus during activity segments (minimal off-task talk).

3. Follows lab safety and procedural cues without repeated reminders.

B. Participation

4. Handles materials/equipment appropriately (tools, specimens, models).

5. Contributes to group work (shares roles, helps peers).

6. Volunteers responses during Q\&A or shares findings during plenary.

7. Completes activity steps within allotted time.

C. Question-Asking & Inquiry

8. Asks clarification questions about procedures or concepts.

9. Poses exploratory questions/hypotheses (e.g., “What if we…?”).

10. Uses evidence/observations to justify claims during discussion.

D. Persistence & Self-Regulation

11. Persists when tasks are challenging (tries another approach before asking for help).

12. Checks instructions/protocols independently.

13. Records observations/data carefully (labels, measurements, sketches).

E. Affective Indicators

14. Displays curiosity/enthusiasm (tone, expressions, eagerness to participate).

15. Expresses enjoyment/satisfaction after completing task.

Observation Sheet Template (repeat for each session)

Date: ___________ Period: ___________

Activity:

- ☐

Dissection

- ☐

Model-building

Experiment Observer: ___________ Class size present: ___________

Ratings (1-5):

A1 ___________ A2 ___________ A3 ___________

B4 ___________ B5 ___________ B6 ___________ B7 ___________

C8 ___________ C9 ___________ C10 ___________

D11 ___________ D12 ___________ D13 ___________

E14 ___________ E15 ___________

Notes/Evidence (short quotes/behaviors)

_______________________________________________________

Safety/Logistics Issues (if any)

_______________________________________________________

Rubrics / Scoring & Use

Compute mean score per indicator and domain averages (A–E).

Compare Baseline vs Intervention vs Post.

Appendix D

Expert Validation Process

To ensure content validity, all instruments underwent expert review by two senior biology teachers (each with over 10 years of experience) and one educational measurement specialist. They evaluated each item for clarity, relevance, and alignment with the constructs of engagement and motivation using a 4-point relevance scale (1 = not relevant to 4 = highly relevant). Items with a content validity index (I-CVI) below 0.75 were revised for clarity. Observational indicators were also verified for feasibility and behavioral clarity within school laboratory settings. Minor linguistic refinements were made before pilot testing.

Recommendations

- 1.

Integrate structured practical activities such as dissections, model-building, and experiments regularly to sustain engagement and motivation.

- 2.

Provide teacher training on inquiry-based pedagogy to maximize the educational impact of hands-on learning.

- 3.

Use triangulated assessment methods (surveys, observations, and reflections) to continually evaluate engagement and motivation levels in zoology classes

References

- Acosta-Gonzaga, E.; Ramirez-Arellano, A. Scaffolding matters? Investigating its role in motivation, engagement and learning achievements in higher education. Sustainability 2022, 14(20), 13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Gharibi, K. A.; Schmidt, N.; Arulappan, J. Effect of repeated simulation experience on perceived self-efficacy among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today 106 2021, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hor, M.; Almahdi, H.; Al-Theyab, M.; Mustafa, A. G.; Seed Ahmed, M.; Zaqout, S. Exploring student perceptions on virtual reality in anatomy education: Insights on enjoyment, effectiveness, and preferences. BMC Medical Education 24 2024, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G. M.; Rahman Forhad, M. A. The impact of accessing education via smartphone technology on education disparity-A sustainable education perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15(14), 10979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C.; Kennedy, G. Teaching for quality learning at university, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education/ Open University Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, A. R. The evolving ethics of anatomy: Dissecting an unethical past in order to prepare for a future of ethical anatomical practice. The Anatomical Record 2022, 305(4), 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, A.; EidiBaygi, H.; Mohammadi, S.; Etezadpour, M.; Yavari, M.; Mastour, H. Virtual dissection: An educational technology to enrich medical students’ learning environment in gastrointestinal anatomy course. Medical Science Educator 2023, 33(5), 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredricks, J. A.; Blumenfeld, P. C.; Paris, A. H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research 2004, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S. L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M. K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M. P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, N. A.; Kew, S. N.; Tasir, Z.; Koh, E. Learning analytics on student engagement to enhance students’ learning performance: A systematic review. Sustainability 2023, 15(10), 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalınkara, Y. The role of artificial intelligence in the ethical relationship of virtual cadavers. Experimental and Applied Medical Science 2024, 5(5), 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research; Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T. K.; Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2016, 15(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazonder, A. W.; Harmsen, R. Meta-analysis of inquiry-based learning: Effects of guidance. Review of Educational Research 2016, 86(3), 681–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nicolás, R.; López-López, J. A.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Sánchez-Meca, J. A meta-review of transparency and reproducibility-related reporting practices in published meta-analyses on clinical psychological interventions (2000-2020). Behaviour Research Methods 2022, 54(1), 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, N.; Aras, C.; Kleine Staarman, J.; Alotaibi, S. B. M. Embodied learning of science concepts through augmented reality technology. Education and Information Technologies 30 2024, 8245–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Bonito, J. Practical work in science education: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Education 8 2023, 1151641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M. J. Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education 2004, 93(3), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Tseng, C. M. Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2011, 36(4), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.; Kelly, A. M. Mixed-methods study of student participation and self-efficacy in remote asynchronous undergraduate physics laboratories: Contributors, lurkers, and outsiders. International Journal of STEM Education 10 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sukkurwalla, A.; Zaidi, S. J. A.; Taqi, M.; Waqar, Z.; Qureshi, A. Exploring medical educators’ perspectives on teaching effectiveness and student learning. BMC Medical Education 24 2024, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education 48 2018, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindan, T. N.; Anaba, C. A. Scientific hands-on activities and its impact on academic success of students: A systematic literature review. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education 2024, 14(6), 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. K. J.; Liu, W. C.; Kee, Y. H.; Chian, L. K. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: Understanding students’ motivational processes using self-determination theory. Heliyon 2019, 5(7), e01983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Lee, E.; Kim, C.-J.; Shin, Y. Virtual reality simulation-based clinical procedure skills training for nursing college students: A quasi-experimental study. Healthcare 2024, 12(11), 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y. H.; Kwon, H. Y.; Jeon, S. K.; Jon, Y. M.; Park, M. J.; Shin, D. H.; Choi, H. J. Effectiveness and satisfaction with virtual and donor dissections: A randomized controlled trial. Scientific Reports 14 2024, 16388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).