1. Introduction

The skin plays a pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis within the human body, serving as the primary barrier against pathogenic invasion and thereby preventing the onset of severe diseases [

1]. Effective skin regeneration, particularly in the context of wound healing, necessitates a finely tuned interplay among the extracellular matrix (ECM), fibroblast cells, and biologically active molecules. The advent of synthetic scaffolds has significantly advanced the field of tissue engineering, offering promising avenues for skin repair by emulating the structural and functional characteristics of the ECM [

2]. Scaffold architecture is critical to sustaining regenerative processes, yet a major challenge persists: designing scaffolds that accurately replicate the ECM's complexity. Beyond providing mechanical support, scaffolds must also facilitate cellular behaviors essential for tissue regeneration. Failure to address these biological interactions often results in suboptimal regenerative outcomes [

3]. Traditional tissue engineering techniques frequently fall short in delivering the mechanical integrity and structural fidelity required for dermal regeneration, particularly in cases involving tissue lesions or degeneration. In response, researchers have explored innovative approaches to enhance ECM mimicry, leading to the emergence of electrospinning as a transformative technique. Electrospinning enables the fabrication of nanofibrous polymer scaffolds characterized by a high surface area-to-volume ratio, which promotes cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [

4]. This method effectively reproduces key ECM properties, including support for cell migration and proliferation, and allows for the integration of bioactive molecules tailored to specific tissue requirements. Such versatility has positioned electrospinning as a cornerstone in regenerative medicine.

Historically, electrospun fibers have found applications in wound dressings and air filtration systems [

5]. More recently, biohybrid fibers produced via electrospinning have contributed to sustainable water treatment technologies [

6]. The technique's ability to generate scaffolds with high porosity and tunable mechanical properties closely resembling the ECM has garnered substantial interest in biomedical research. Electrospinning involves a four-step scaffold preparation process, yielding nano- and micro-scale fibers that are difficult to replicate using alternative methods such as freeze-drying [

1]. Among the polymers employed, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) stands out due to its hydrophilicity, mechanical robustness, and biocompatibility [

7]. PVP is a bulky, non-toxic, and nonionic compound with antimicrobial properties [

8]. While chitosan is recognized for its biocompatibility, its application in electrospinning is hindered by poor spinnability and high viscosity. However, its performance can be enhanced through the incorporation of complementary materials. For instance, pectin—a biodegradable natural immunomodulator—has been successfully integrated into scaffold designs to improve functional outcomes [

2]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that electrospun scaffolds support cell infiltration, nutrient diffusion, and microbial activity, making them a preferred choice for tissue regeneration applications [

9,

10]. Optimization of scaffold fabrication parameters—such as needle diameter, flow rate, and polymer concentration—through iterative experimentation is essential for achieving desired regenerative outcomes.

This study explores the development and evaluation of electrospun PVP scaffolds designed for dermal regeneration applications. The research emphasizes critical parameters that affects scaffold fabrication via electrospinning, and structural parameters that influence scaffold efficacy, including fiber diameter and porosity, which affects cellular infiltration and nutrient diffusion; surface morphology, which governs cell attachment and proliferation. Through systematic characterization the current study aims to determine the suitability of PVP-based scaffolds as potential platforms for skin tissue engineering and wound healing therapies.

3. Results and Discussion

Electrospinning parameters must be carefully optimized to produce nano-scale fibrous scaffolds that closely mimic the physical characteristics of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Such structural similarity provides a biomimetic environment conducive to cellular adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation within the human body. The physical properties of electrospun scaffolds are highly sensitive to both material composition and processing conditions, including polymer concentration, solution flow rate, applied voltage, tip-to-collector distance, needle gauge, and ambient factors such as temperature and humidity [

6,

11].

Table 1 summarizes the influence of key processing parameters on the fabrication of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) nanofibrous scaffolds via electrospinning. Scaffolds were produced using 100% ethanol as the solvent while varying polymer concentration and processing parameters, including flow rate, applied voltage, and needle diameter. Electrospinning was unsuccessful at lower PVP concentrations (40–50% w/v), a flow rate of 0.5 mL/h, and voltages below 26 kV. Polymer concentration plays a critical role in determining solution viscosity and surface tension, which govern fiber formation. Adequate chain entanglement is essential for generating a stable and continuous fiber jet; insufficient polymer concentration results in low viscosity and limited chain interactions, causing fiber breakup into droplets before reaching the collector. Conversely, excessively high polymer concentrations lead to elevated viscosity and rapid solidification, which can obstruct the needle outlet and hinder fiber formation [

12,

13,

14,

15].

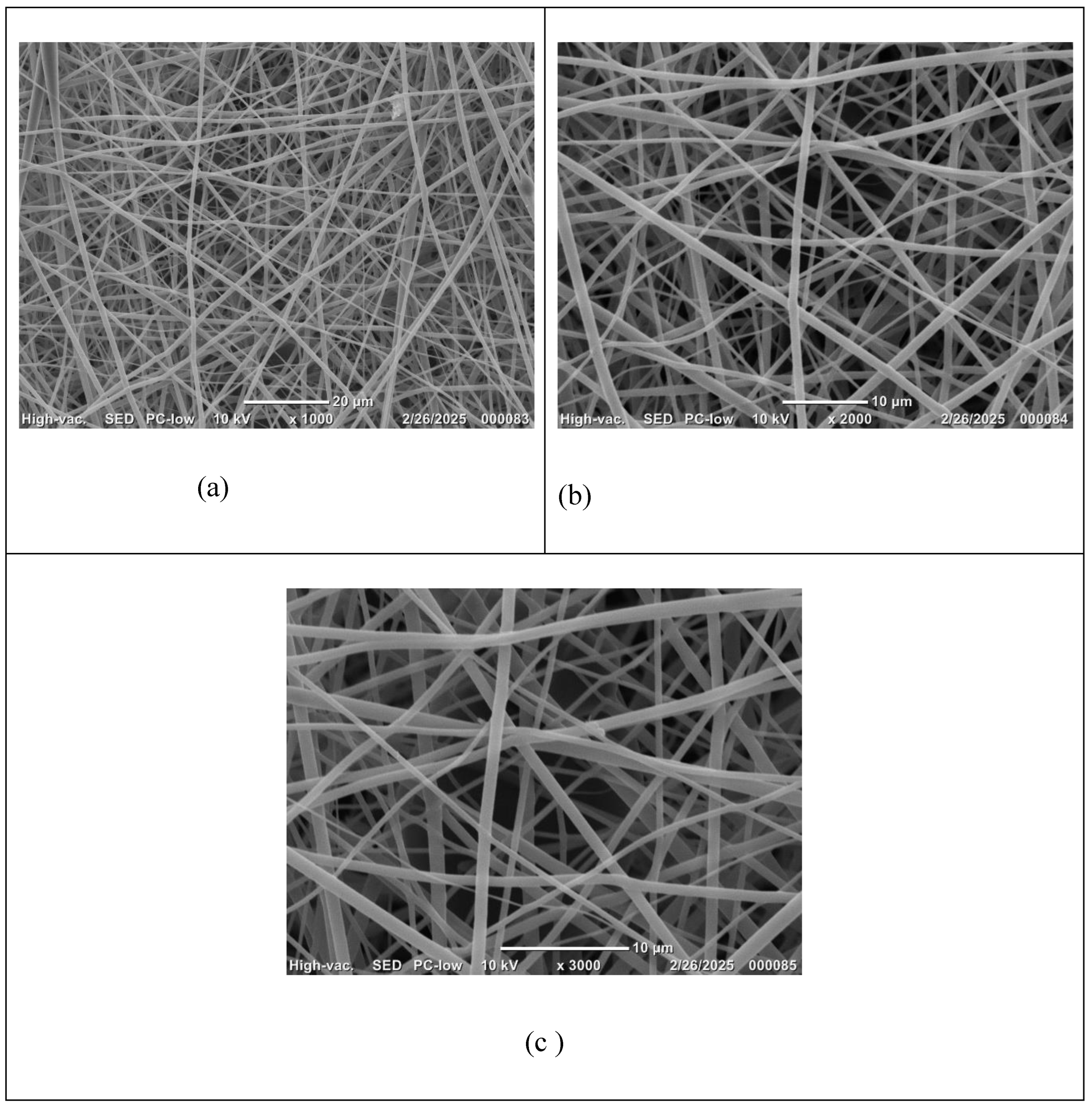

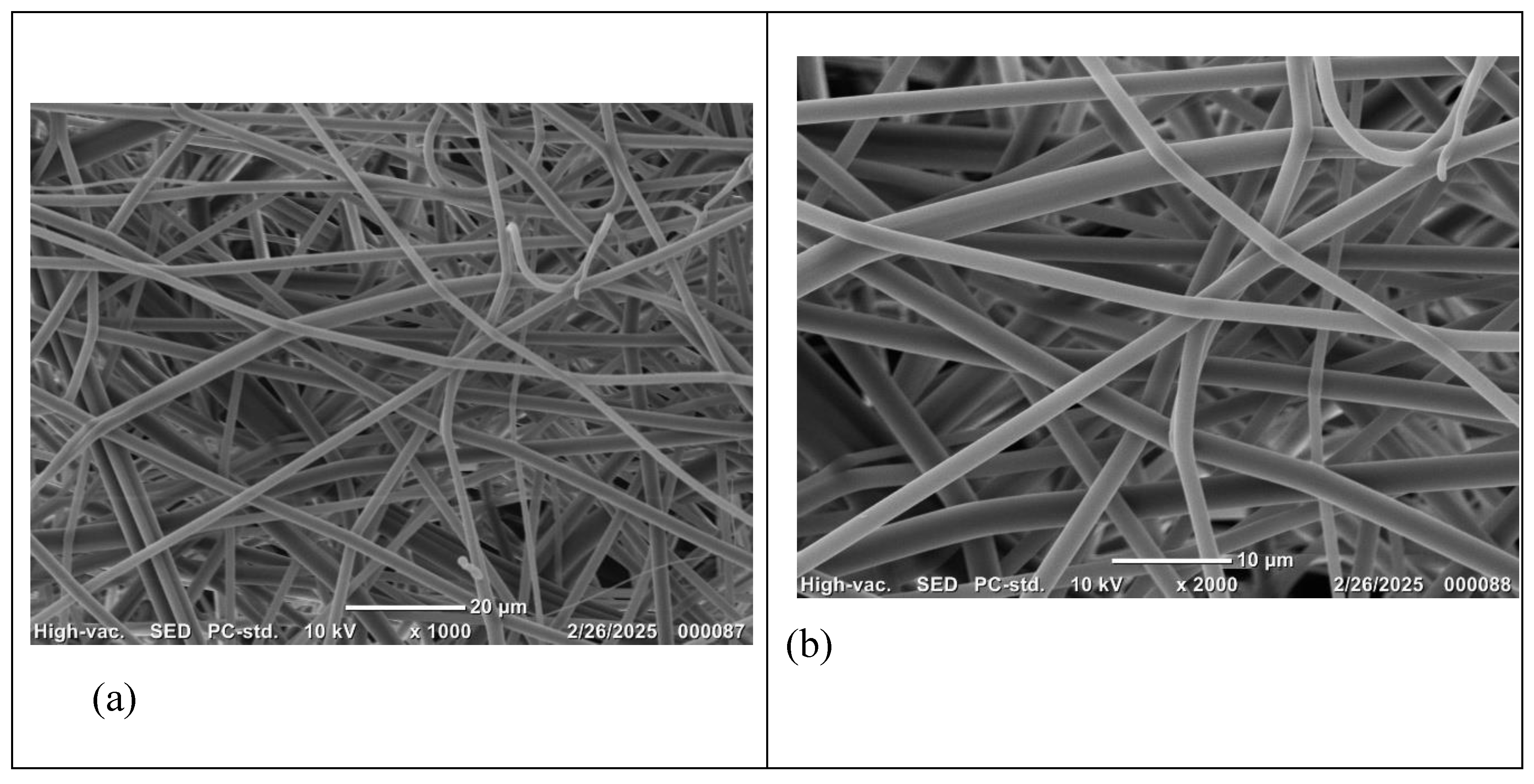

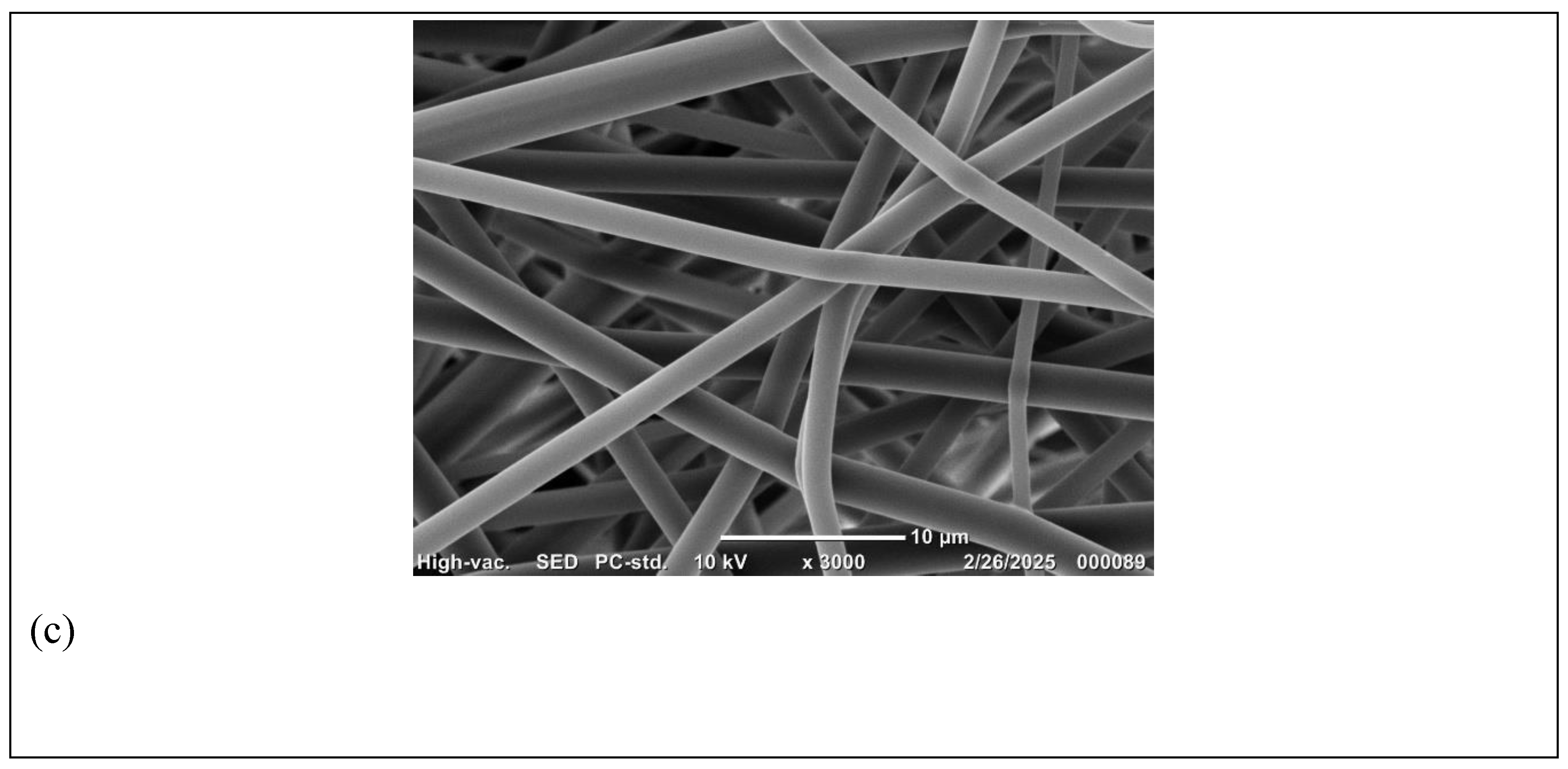

When the PVP concentration was increased to 60% (w/v) with flow rate 1 ml/h and applied voltage 26 kv, the electrospinning was successful using needle diameter 15 G and 18G. Morphological analysis using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and consequently an Image J software showed the average fiber diameter of 1853.90±229 nm when using 15G needle, whereas, 647.52±638 nm when using 18G needle (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). This significant variation between the two samples demonstrates how slight variations in electrospinning parameters, (voltage, polymer concentration, or flow rate), can dramatically affect the formation of fibers and scaffold architecture.

Increasing the PVP concentration to 60% (w/v), combined with a flow rate of 1 mL/h and an applied voltage of 26 kV, enabled successful electrospinning using needle gauges of 15G and 18G. Morphological characterization via scanning electron microscopy (SEM), followed by quantitative analysis using ImageJ, revealed a marked difference in fiber dimensions between the two configurations (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). The average fiber diameter was

1853.90 ± 229 nm for scaffolds fabricated with a 15G needle, whereas fibers produced with an 18G needle exhibited a significantly smaller average diameter of

647.52 ± 638 nm. This substantial variation highlights the critical role of needle diameter in controlling fiber morphology, as it influences the initial jet formation, solution throughput, and electric field distribution during electrospinning.

The observed differences can be attributed to the interplay between solution properties and process parameters. Larger needle diameters (15G) allow higher volumetric flow and reduced shear stress, which, combined with high polymer concentration, promotes the formation of thicker fibers. Conversely, smaller needles (18G) restrict flow and increase elongational forces on the polymer jet, resulting in finer fibers with greater variability. These findings underscore the sensitivity of electrospinning to even minor adjustments in operational settings—such as needle gauge, applied voltage, and polymer concentration, which collectively determine fiber uniformity, porosity, and scaffold architecture [

16,

17]. Such morphological variations are not merely structural; they directly impact scaffold performance by influencing surface area, pore interconnectivity, and mechanical properties, all of which are essential for cell attachment, nutrient diffusion, and tissue integration in regenerative applications.

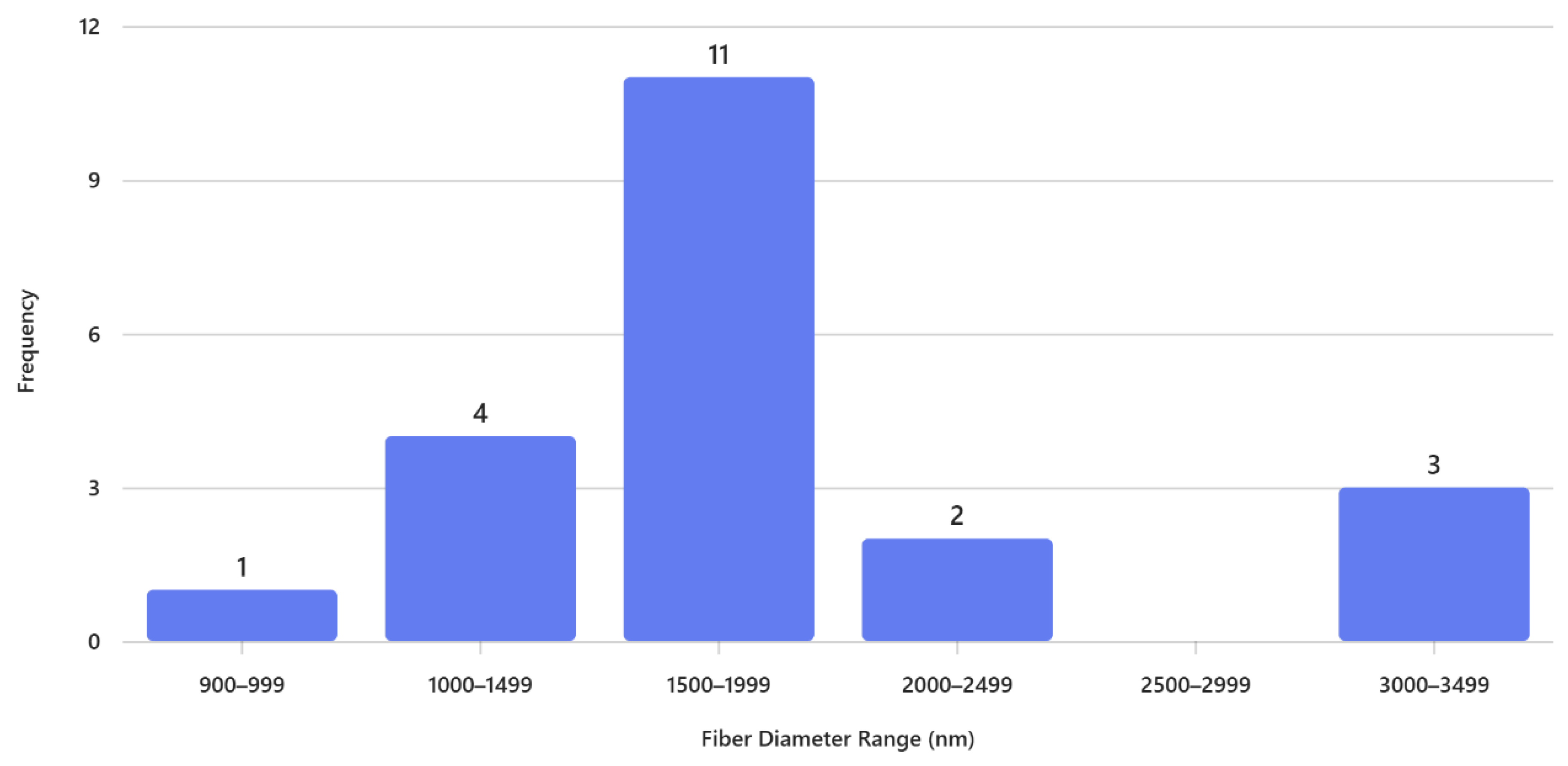

The histogram in

Figure 2 shows that the fiber diameter distribution is strongly centered around

1500–1999 nm, which accounts for the highest frequency (11 fibers), indicating that the electrospinning process predominantly produces fibers in this range. A smaller proportion of fibers fall within

1000–1499 nm (4 fibers) and

3000–3499 nm (3 fibers), while very thin fibers (

900–999 nm) and moderately thick fibers (

2000–2499 nm) are rare, with only 1 and 2 observations respectively. Notably, there are no fibers in the

2500–2999 nm range, creating a gap in the distribution. Overall, the pattern is unimodal and slightly right-skewed, suggesting that the process favors relatively thick fibers, with occasional formation of much thicker fibers, likely due to variations in jet stability or solution properties.

Figure 2.

Distribution of fiber diameters of PVP electrospun nanofibers produced from 15 G needle.

Figure 2.

Distribution of fiber diameters of PVP electrospun nanofibers produced from 15 G needle.

Figure 3.

SEM Micrographs of 60% (w/v) PVP electrospun scaffolds using needle 18G; magnifications (a) X1000; (b) X2000 and (c) X3000.

Figure 3.

SEM Micrographs of 60% (w/v) PVP electrospun scaffolds using needle 18G; magnifications (a) X1000; (b) X2000 and (c) X3000.

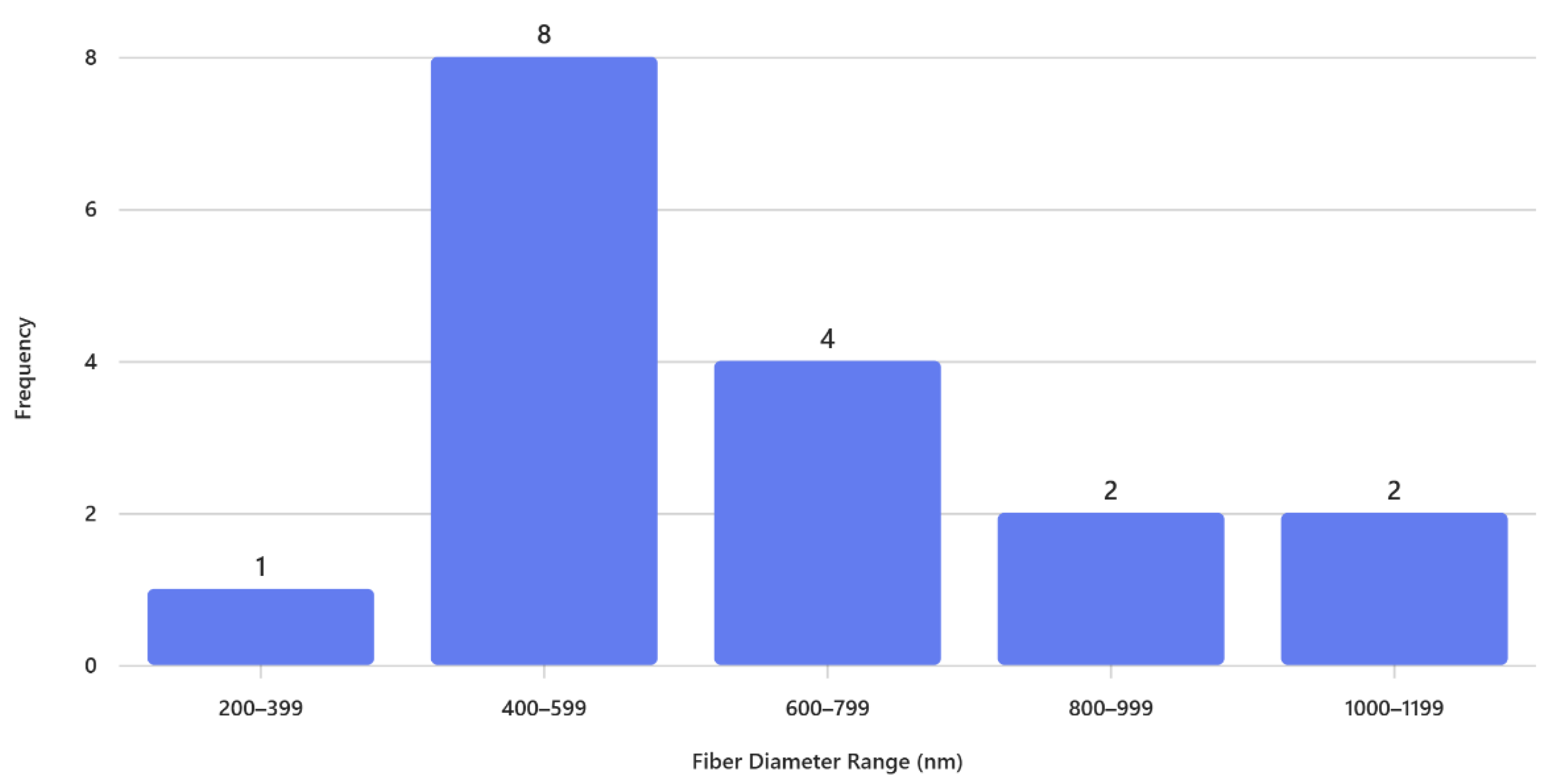

The histogram in

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of fiber diameters for PVP electrospun nanofibers fabricated using an 18-gauge needle. The data reveal a clear predominance of fibers within the

400–599 nm range, which accounts for the highest frequency (8 observations). This suggests that the electrospinning parameters employed favor the formation of fibers in the mid-nanometer scale, likely due to a balance between solution viscosity, applied voltage, and needle gauge that promotes stable jet formation.

Fibers in the 600–799 nm range represent the second most frequent category (4 observations), indicating some variability toward thicker fibers, possibly influenced by localized fluctuations in jet stability or solvent evaporation rate during spinning. In contrast, very thin fibers (200–399 nm) are rare, with only one observation, suggesting that the current processing conditions do not strongly support the formation of ultrafine fibers. Similarly, larger diameters (800–999 nm and 1000–1199 nm) occur infrequently (2 observations each), which may be attributed to occasional bead formation or transient changes in flow rate.

The histogram of

Figure 4 shows a narrow distribution of fiber diameters primarily in the nanometer range, with most fibers between

400–599 nm, indicating finer and more uniform fibers produced using an 18 G needle. In contrast, the histogram of

Figure 2 exhibits a much broader distribution, dominated by fibers in the

1500–1999 nm range and extending up to

3000–3499 nm, reflecting significantly thicker fibers and greater variability using a 15G needle. This difference suggests that the second process involves larger needle gauge, resulting in reduced jet stretching and larger fiber formation. Overall, the comparison highlights how processing conditions strongly influence fiber morphology, with the 18G favoring nanofiber production and the 15G yielding microfibers.

Scaffolds produced under optimized conditions exhibit a consistent fiber distribution with minimal bead formation, which is a critical quality indicator for tissue engineering. Bead-free fibers contribute to an open and interconnected morphology, enhancing surface area and porosity, attributes essential for promoting cell attachment, facilitating nutrient and oxygen diffusion, and supporting overall tissue integration. Furthermore, the absence of structural defects improves mechanical stability and ensures reproducibility, which are vital for clinical translation. Collectively, these considerations underscore the importance of systematic parameter optimization in electrospinning to achieve scaffolds that not only mimic ECM architecture but also meet the functional requirements for regenerative medicine [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the critical influence of electrospinning parameters, particularly polymer concentration, flow rate, applied voltage, and needle diameter, on the successful fabrication and morphological characteristics of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) nanofibrous scaffolds. Electrospinning was unsuccessful at lower polymer concentrations (40–50% w/v) and suboptimal operational settings, primarily due to insufficient viscosity and inadequate chain entanglement, which resulted in fiber breakup and bead formation. Increasing the PVP concentration to 60% (w/v), combined with a flow rate of 1 mL/h and an applied voltage of 26 kV, enabled stable fiber formation using both 15G and 18G needles. However, SEM analysis revealed significant differences in average fiber diameter, 1853.90 ± 229 nm for 15G and 647.52 ± 638 nm for 18G, underscoring the sensitivity of electrospinning to even minor variations in processing conditions. These findings highlight the necessity of systematic parameter optimization to achieve scaffolds with uniform fiber morphology, high porosity, and interconnected architecture, which are essential for tissue engineering applications. The ability to fine-tune electrospinning conditions allows for precise control over scaffold properties, directly impacting cell attachment, nutrient diffusion, and overall tissue integration. Future work focuses on tuning materials properties by blending PVP with chitosan and pectin and investigating the morphological outcomes with biological performance, including cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation, to utilize PVP-based electrospun scaffolds in regenerative medicine.