1. Introduction

The use of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-expressing T cells (CAR-T cells) generated a paradigm change in cancer therapy, particularly for hematologic malignancies, where CAR-T cells have demonstrated remarkable success [

1]. However, the efficacy of CAR-T cells in solid tumors [

2,

3] has been limited by several critical barriers, such as poor infiltration into the tumor microenvironment, exhaustion of T-cells and the immunosuppressive microenvironment of solid tumors [

4,

5].

To address these limitations, the technology of macrophages engineered to express a Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR-M) allowing to target solid tumors has recently been developed [

6]. This might secure a novel cellular therapy platform that leverages the phagocytic capacity, antigen presentation capability and pro-inflammatory plasticity of macrophages, thus playing a critical role in the therapy of solid tumors [

6].

Thus, CAR macrophages represent a new class of engineered immune cells designed to overcome the physical and immunological barriers that limit traditional CAR therapies in solid tumors. Unlike T-cells, macrophages possess innate tumor-homing abilities and can penetrate and survive within the dense, immunosuppressive stroma. When engineered to express a CAR construct, they not only recognize and phagocytose tumor cells in an antigen-specific manner, but also serve as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that activate endogenous T-cell responses. bringing a novel potential of cancer “vaccination” [

7]. Like CAR-T cells, novel “Second generation” CAR-Ms have also been generated and have led to remarkable results using double intracellular-activation domains [

8].

After design of the first preclinical model of CAR-macrophages in 2020 [

7], the first-in-human Phase I clinical trial [

9] data from 14 patients with HER2-overexpressing advanced solid tumors confirmed the feasibility of manufacturing high quantity and quality of autologous macrophages maintaining elevated levels of CAR expression.

Here, we have developed a novel CAR-Macrophage model specifically targeting mutated EGFR

VIII which is a major cancer driver in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

10] and glioblastoma [

11]. The CAR construct was strategically engineered to enhance the macrophage’s inherent ability to phagocytose non-self-pathogens and malignant cells. This was achieved by incorporating the intracellular domain of the MEGF10 protein, which potentates i-macrophage’s phagocytic function [

12]. The concept was applied on THP-1 human monocyte cell lines for targeting DKMG-EGFR

VIII glioblastoma cells lines. The specificity and efficacy of this CAR-Macrophage are the focal points of the present investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

The THP-1, a human monocytic cell line purchased from ATCC (Cat#: TIB-202) was used to generate monocyte-derived macrophages. Cells were cultured with RPMI supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Cat#: A5256701), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco™ Cat#: 15140122) and 1 X Glutamax (Gibco, Cat#: 35050061).

U-87 MG (ATCC, Cat#: HTB-14) is a glioblastoma (GBM) cell line without EGFRVIII - mutation. It was cultured in MEM alpha medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Cat#: A5256701), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco™- Cat#: 15140122).

Another GBM cell line, DK-MG-EGFRVIII (Amsbio, Cat#: CL 01008-CLTH) expressing mutated EGFRVIII was cultured with RPMI supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Cat#: A5256701), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco™ Cat#: 15140122). The presence of EGFRVIII in DKMG cells was confirmed by flow cytometry and sequencing (data not shown).

2.2. CAR and MOCK Constructs

A Chimeric Antigen Receptor construct mostly efficient in macrophages (CAR-M) was engineered to optimize phagocytic activity. The CAR construct incorporates the intracellular domain of the MEGF10 protein (amino acids 879-1147) and is followed by the hinge and transmembrane regions of human CD8α (amino acids 183-206). The extracellular component of the CAR protein comprises an anti-EGFRVIII single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from the 139 scFv nucleotide sequence (Supp. Figure 4). CAR-EGFRVIII and transduction control (Mock) constructs without the CAR were synthesized and subcloned into lentiviruses (EF1α-CAR-CMV-eGFP) by VectorBuilder (Chicago,USA).

2.3. Lentivirus-Mediated CAR-EGFRVIII and MOCK Transduction in THP1 Cells

7.5x105 THP-1 cells / well were seeded into a 24-well plate with 10µg/ml of polybrene. Cells were spinoculated with lentivirus (MOI=5) for 90 min at 1200 g and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. 24h after cell transduction, 50% of the total volume of the wells was removed and replaced by fresh media. At +48h, a total media change was performed. Cell culture was performed for 2 weeks and the media was replaced every 3 days.

2.4. Selection of CAR-Expressing Cells

At 3 weeks of culture, THP-1 cells were sorted according to levels of GFP expression by using BD FACSAria™ III Cell Sorter. After a first round of cell sorting of GFP-positive cells, EGFRVIII-CAR expressing cells in the GFP positive population were selected by using EGFRVIII-PE protein (Accro Biosystems, Cat#: EGI-HP2H6).

2.5. Generation of Macrophages from THP1 Cell Line

To differentiate THP-1 monocytes into macrophages, 1.5x106 monocytes /well were plated in a 6-well plate with RPMI supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Cat#: A5256701), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco™ Cat#: 15140122) and 10ng/ml PMA (Thermo Fisher, Cat#: 356150010) for 24h at 37oC and 5% CO2. After 24h of incubation the culture medium was replaced by RPMI supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Cat#: A5256701), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco™ Cat#: 15140122). 48h after seeding cell culture medium was replaced by RPMI complete medium supplemented with 20ng/ml IFNγ+100ng/ml LPS and the cells were incubated for 48h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Adherent cells were detached using StemPro™ Accutase™ (Gibco, Cat#: A1110501) for 10 min and analyzed by FACS to evaluate the phenotypic markers of M1 or M2 macrophages.

2.6. Immunophenotyping of Monocytes and Macrophages

Flow cytometry was performed by using classical myeloid markers such as CD11b (Miltenyi Biotec Cat#: 130-110-558), HLA-DR(MHC-II) (Miltenyi Biotec Cat#: 130-111-795) as well as M1 and M2 specific markers CD80(Miltenyi Biotec Cat#: 130-117-719), CD86(Miltenyi Biotec Cat#: 130-116-164), CD206(Miltenyi Biotec Cat#: 130-133-375) and CD163(Miltenyi Biotec Cat#: 130-112-129). All antibodies were obtained from Miltenyi Biotech and used at a dilution following the manufacturer’s instructions. M1 macrophages were detached with StemPro™ Accutase™ (Gibco, Cat#: A1110501) for 10 min, then centrifuged at 1200g for 5 min. Cells were then counted and 105 cells were used for each FACS tube for analysis. Antibodies were used at 1/100 dilution in 200µl volume PBS-BSA (CORNING, Cat#: 21-040-CV) and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Tubes were then centrifuged at 1200g for 5 min and washed 2 times with PBS-BSA before analysis. Flow cytometry was performed on BD LSR Fortessa™ X-20 cell analyzer. FACS data was processed using FlowJo V.10.

2.7. Phagocytosis Assays

After induction of differentiation towards an M1 phenotype, macrophages were detached with StemPro™ Accutase™ (Gibco, Cat#: A1110501) for 10 min., then centrifuged at 1200g for 5 min. and seeded into µ-Dish 35 mm Quad culture plates (Ibidi Cat#:80416 ibi treated) at a concentration of 150.000 Macrophages with 15.000 target cells at an E:T ratio of 10:1 for 40h.

2.8. Detection of Phagocytosis by THP-1 Derived CAR-M

Glioma DK-MG (EGFRVIII+) and U87 cells (EGFRVIII-) were used as target and control cell lines, respectively. Both cell types were stained with CellTracker™ Red CMTPX dye (10 μM; Invitrogen, C34552) for 20 minutes at 37°C to enable fluorescent identification. CAR-engineered THP-1-derived macrophages (CAR-Ms), constitutively expressing GFP, and wild-type M1-polarized macrophages (WT-M1s), stained with CellTracker™ Green, were co-cultured with either DK-MG-EGFRVIII or U87 cells at an optimized effector-to-target (E: T) ratio of 10:1. Co-cultures were maintained for 40 hours at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Following incubation, phagocytic interactions were assessed using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope, and images were acquired with LAS AF software (v3.2). Image analysis and quantification were performed using Fiji (ImageJ). Phagocytic efficiency was determined by calculating the ratio of GFP+ macrophages containing intracellular red fluorescent stains (representing engulfed tumor cells) to the total number of macrophages per field.

2.9. Video Microscopy Analyses

A commercial HIS-SIM was used to acquire and reconstruct the cell images. To further improve the resolution and contrast in reconstructed images, sparse deconvolution was used. Live-cell imaging was performed by their commercial super-resolution microscope (Confocal LSM 980 Airyscan2 NLO) located at Jacques Monod institute, Imago-Seine, Paris, France image acquisition and treatment was achieved using Fiji (ImageJ).

2.10. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release-Based Cytotoxicity Assay

Co-culture experiments were performed using DK-MG (EGFRVIII+) and U87 (EGFRVIII-negative) glioma cells as target populations. CAR-engineered THP-1-derived M1 macrophages (CAR-M1) and wild-type M1 macrophages (WT-M1) were seeded at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 10:1 and incubated with target cells for 40 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

After the co-culture period, supernatants were harvested and subjected to cytotoxicity analysis using the Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH, Roche, Cat#: 11644793001) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured at 485 nm, with a reference wavelength above 600 nm, using a calibrated microplate reader. Supernatants from monocultures of CAR-Ms and WT-Ms served as background controls to correct for spontaneous LDH release from effector cells following the formula Sample OD - BG OD= True OD. The percentage of specific cytotoxicity was calculated using the formula provided by the manufacturer’s kit, incorporating appropriate background subtraction. Data were graphically compared using non-parametric T-test (Mann-Whitney) on GraphPad Prism8, p-value≤0.05 marked as *.

2.11. Assessment of Cytokine Levels by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Culture media was collected from co-cultures (40h) and cytokine levels were measured using IL-6, IL-12, TNF-alpha and IL-1β Elisa kit (Elabscience Cat#: E-EL-H6156, E-EL-H0150, E-EL-H0149, E-EL-H0109) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were measured at 490 nm with a microplate reader Modulus II (Turner Biosystems, INSERM U1310, Villejuif, France). Measurements were calculated after subtracting the median value of each sample OD with the median zero standard optical density.

2.12. Transcriptome Analyses

The molecular analyses were performed in CD14+ macrophages expressing CAR-EGFRVIII or MOCK constructs, after co-culture with EGFRVIII-mutated or unmutated GBM cells. 106 cells were used for RNA extraction in triplicate (Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit 50 Cat#: 74104) before transcriptome analysis performed in using Illumina at Institut Cochin-Genom’ic Facility (Paris, France).

For bioinformatics analyses, Illumina paired end fastq files were assessed to be of good quality with fastqc version 0.12.1. Reads were aligned on human genome version HG38 with STAR algorithm version 2.7.11a [

13]. Transcriptome was mapped with feature file: Goldenpath ensembl gene GTF, available on UCSC website [

14]. Genecounts was down on reverse strand with with STAR algorithm

xiii. Gene symbol annotation was performed with Ensembl Biomart human database version 113 [

15]. Downstream RNAsequencing preprocessing was performed in R software environment version 4.4.2. Raw counts were normalized with scale factor correction in EdgeR version 4.4.2 [

16]. After positive filtration, normalized data were voom transformed with limma version 3.62.2 [

17,

18]. After densityplot assessment of data distribution, quantile normalization was applied to the data (Supplemental Figure 1A) with preprocessCore R-package version 1.68.0 [

19]. Analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed with transpipe15 R-package available at the following address:

https://github.com/cdesterke/transpipe15 (accessed on 2025, April 14th).

Functional enrichment on gene lists was performed with cluster Profiler R package version 4.14.6 [

20,

21] with Gene Ontology database [

22,

23]. Bigwig files of bam coverage were inspected with integrative genomics viewer version 2.17.4 [

24].

2.13. Statistical Analyses

The statistical relevance of phagocytosis of different macrophage conditions as well as the comparison of MFI from FACS data were calculated using non-parametric T-test (Mann-Whitney) on GraphPad Prism8, p-value≤0.05 marked as *.

3. Results

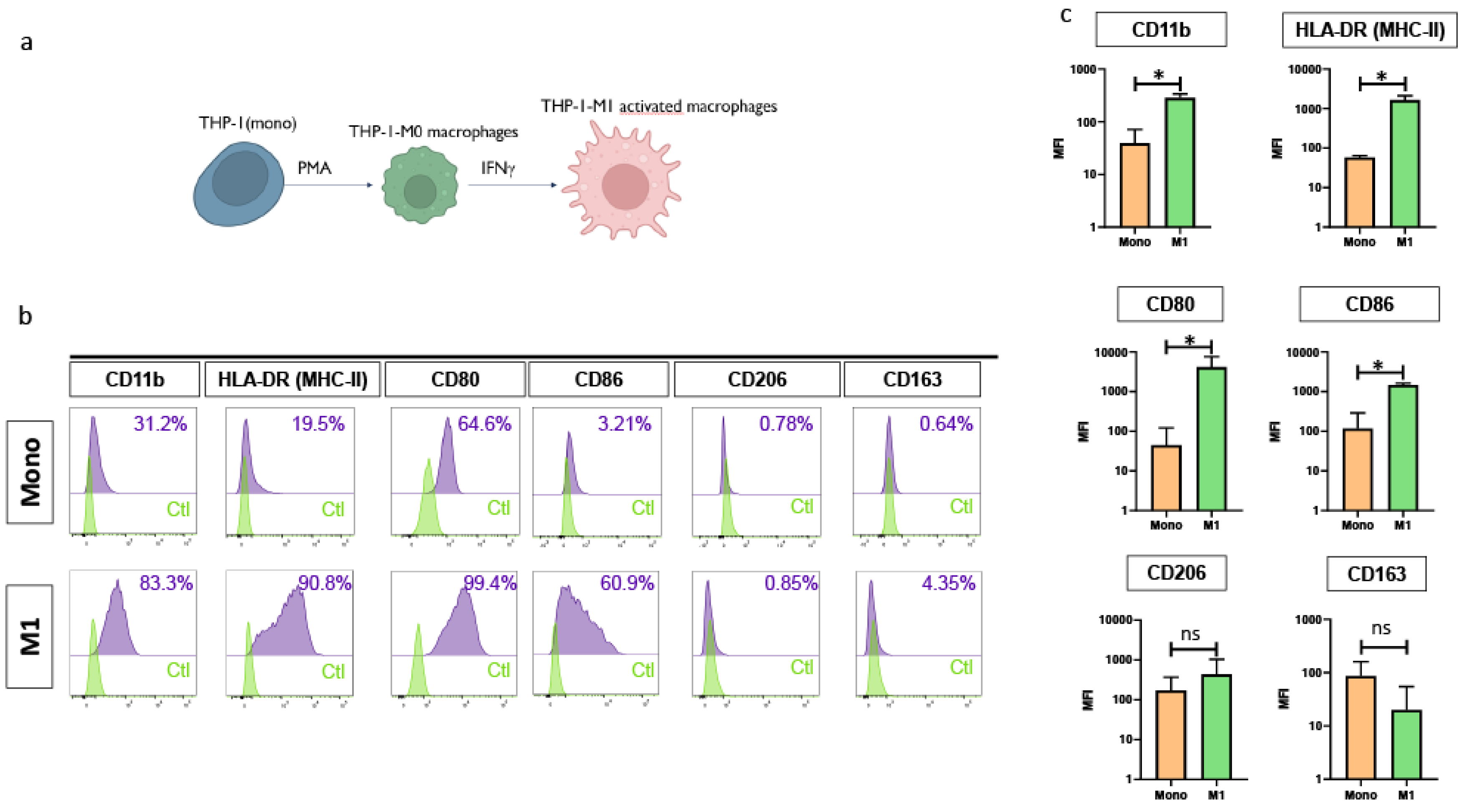

3.1. Differentiation of THP-1 Monocytes into Functionally Polarized M1 Macrophages

To establish a preliminary model, we used the human monocytic THP-1 cell line to evaluate the possibility to produce functional pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. Initial differentiation was induced by treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), resulting in a population of unpolarized, non-activated (M0) macrophages. These cells were subsequently polarized toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype through stimulation with interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), as illustrated in

Figure 1A.

Following the differentiation process, a substantial upregulation of classical macrophage activation markers was observed, indicating a successful transition from monocytes to M1 macrophages. Specifically, the expression of HLA-DR increased from 19.5% to 91 %, CD11b from 31.2% to 83.3%, CD 80 from 52.4% to 99.4%, and CD-86 from 3.21% to 55.0%, respectively. In contrast, surface expression levels of markers typically associated with the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype remained low and showed minimal variation, with CD206 increasing only marginally from 0.78% to 0.85% and CD163 from 1.4 % to 4.35% (

Figure 1B,

Figure 1C). Thus, these results suggested strongly the “pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype of the macrophages generated from THP-1 cell line.

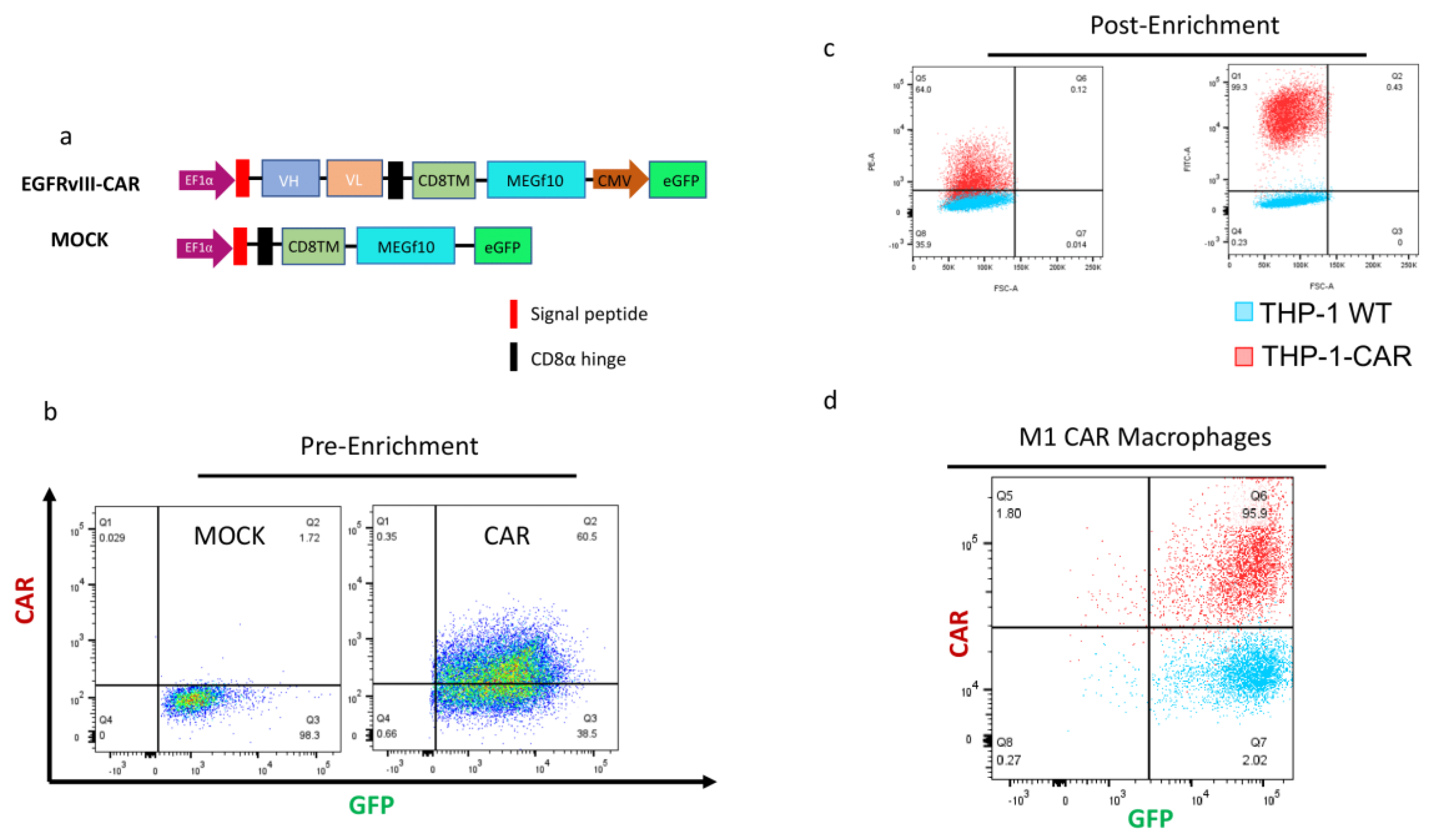

3.2. Lentivirus Mediated Transduction of THP1 Cells with CAR-EGFRVIII Constructs

We engineered a novel CAR-M construct based on a previous study incorporating the intracellular domain of MEGF10 [

12], coupled with a tumor-targeting single-chain variable fragment (scFv) to enable antigen-specific uptake and clearance. The resulting construct is thus tailored to mediate highly specific phagocytosis of tumor cells expressing the corresponding antigen (

Figure 2A). An EGFR

VIII-targeting scFv was incorporated as the extracellular binding domain of the CAR.

To control transduction and expression specificity, we also designed a Mock vector, lacking the scFv and intracellular signaling components but containing the same backbone and reporter features. Both CAR-M and Mock constructs were cloned into lentiviral vectors and used to transduce THP-1 monocytes via spinoculation at an MOI of 5.

After lentiviral transduction, THP-1 cells were expanded and subjected to GFP-based FACS sorting to isolate a pure population of successfully transduced cells (

Figure 2B). Further enrichment of the CAR+ population was achieved by sorting eGFP+ cells that also stained positively with PE-labeled EGFR

VIII protein, confirming surface expression and proper folding of the CAR (

Figure 2C). This resulted in a highly pure CAR-M population, characterized by robust GFP expression and strong PE signal, indicating high CAR density on the cell surface in both monocyte and macrophage states (

Figure 2C,

Figure 2D). Both CAR and Mock-transduced THP-1 cells exhibited complete (100%) GFP positivity, and CAR-expressing cells achieved CAR expression levels exceeding 60% (

Figure 2C).

3.3. CAR Expression Does Not Alter the M1 Differentiation Potential of THP1-Derived Macrophages

The successful generation of EGFR

VIII-specific CAR THP-1 monocytes enabled us to proceed with the induction of their differentiation towards CAR-M1 macrophages. Following differentiation, CAR-M1 macrophages retained high expression levels of both GFP (reporter) and CAR surface protein (

Figure 2D), indicating stable transgene expression throughout the differentiation process. To investigate whether CAR expression impacted the phenotypic profile of the cells in either their monocytic or macrophage states, we performed flow cytometric analysis targeting a panel of canonical myeloid and macrophage polarization markers. The analysis was conducted along two differentiation stages including undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes and M1-polarized macrophages. We first assessed classical myeloid markers, CD11b and HLA-DR (MHC class II), followed by a set of markers associated with macrophage polarization states, specifically CD80, CD86 (M1-associated) and CD206, CD163 (M2-associated). As illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1, no significant differences were detected in the expression of these markers between CAR-transduced and wild-type (WT) THP-1 monocytes, suggesting that lentiviral CAR integration does not overtly alter the basal phenotypic identity of the monocytic population.

A similar comparative approach was applied to the M1-polarized macrophages. As expected, cells displayed an upregulation of proinflammatory surface markers relative to their monocytic precursors, confirming successful polarization. However, no notable phenotypic discrepancies were observed between the CAR-M1 macrophages and their WT counterparts, indicating that CAR expression does not substantially affect M1 polarization or surface marker profiles under the conditions tested.

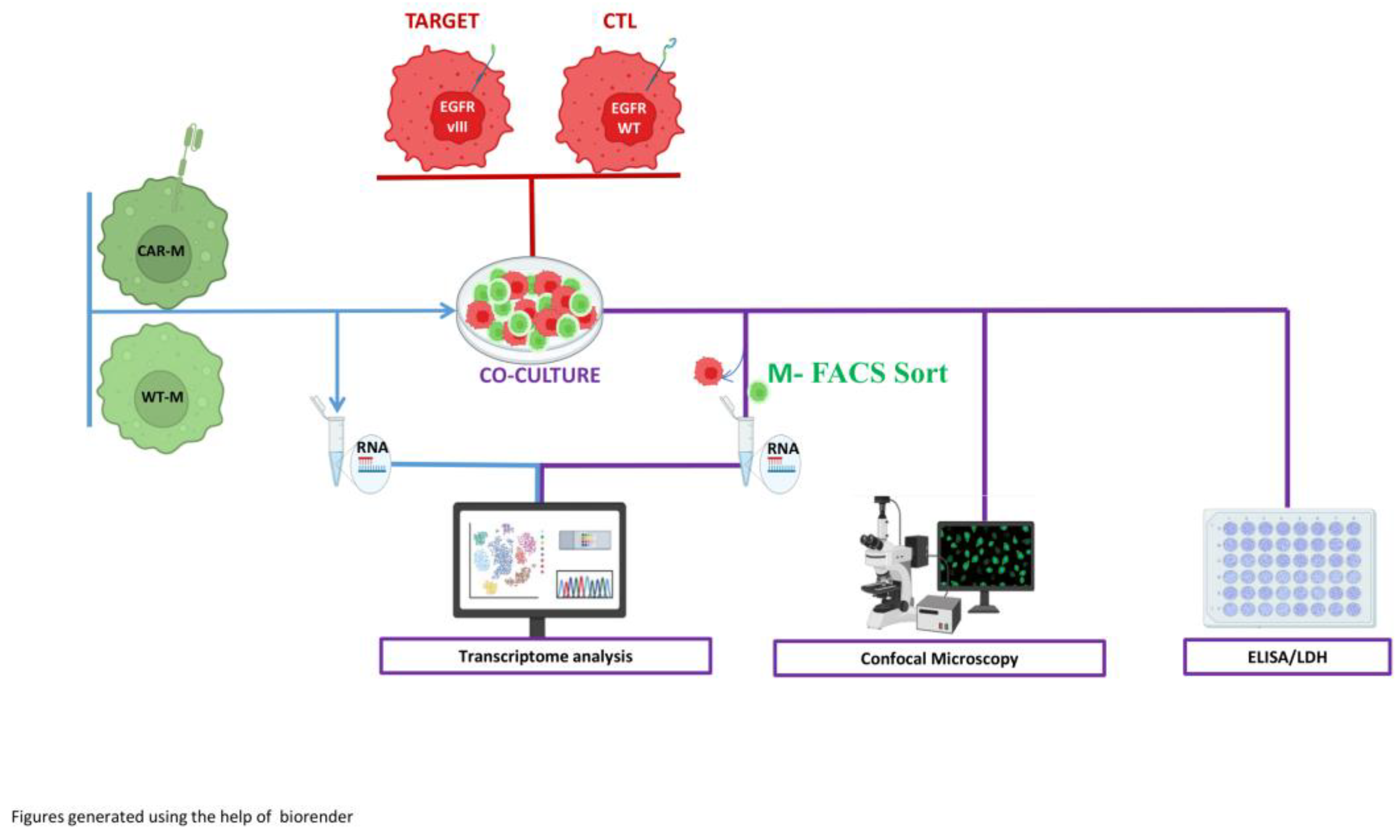

3.4. Establishment of Phagocytosis Assays

Following the successful differentiation of THP-1 CAR-monocytes into EGFR

VIII-directed CAR macrophages and their phenotypic validation, we organized a series of phagocytosis assays to comprehensively evaluate both the specificity and efficacy of CAR-Ms relative to their wild-type (WT) counterparts. Phagocytic activity was assessed over a 40-hour co-culture period at an optimized effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 10:1, which was determined through preliminary testing to yield maximal phagocytic responses in our system (

Figure 3).

For these assays, CAR-expressing and WT M1 macrophages were co-cultured with: (a) DK-MG, a glioma cell line expressing the EGFRVIII mutation and serving as the specific CAR target; and (b) U87 glioma cells, which lacks EGFRVIII expression and were used as non-target controls. The study employed a multi-tiered approach to characterize the interaction between effector macrophages and their target or non-target tumor cells.

To functionally characterize the antigen-specific activity of EGFRVIII-directed CAR macrophages (CAR-Ms) in comparison to their wild-type (WT) counterparts, we established a comprehensive experimental pipeline based on a 40-hour co-culture system with glioblastoma- cell lines.

Phagocytic capacity was first evaluated using both confocal microscopy and live-cell video microscopy to enable direct visualization of tumor cell internalization by macrophages. In this context, macrophages were GFP+ and the target cells were stained by mCherry, allowing to quantify in different sections of the slides the numbers of macrophages presenting m-Cherry expressing target cells in their cytoplasm. These approaches provided quantitative and qualitative data on the specificity and extent of phagocytosis under different target conditions. In parallel, cytotoxic potential was assessed via measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in the co-culture supernatants, serving as a biochemical readout for tumor cell membrane disruption.

To determine the immunological consequences of CAR engagement, we next analyzed the cytokine milieu using ELISA, quantifying levels of key inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 as well as IL1-β, IL-12. This allowed us to discern antigen-specific alterations in macrophage activation profiles and to probe the inflammatory dynamics of the co-culture environment. Finally, to capture the transcriptional evolution associated with antigen recognition and internalization, macrophages were isolated firstly after differentiation and then after co-culture by fluorescence-activated cell sorting to ensure effector cell purity, followed by bulk RNA sequencing. Comparative transcriptomic profiling between CAR-Ms and WT macrophages under both target-positive and target-negative conditions revealed gene expression signatures associated with CAR activation and effector polarization, providing mechanistic insight into the downstream consequences of antigen-specific signaling.

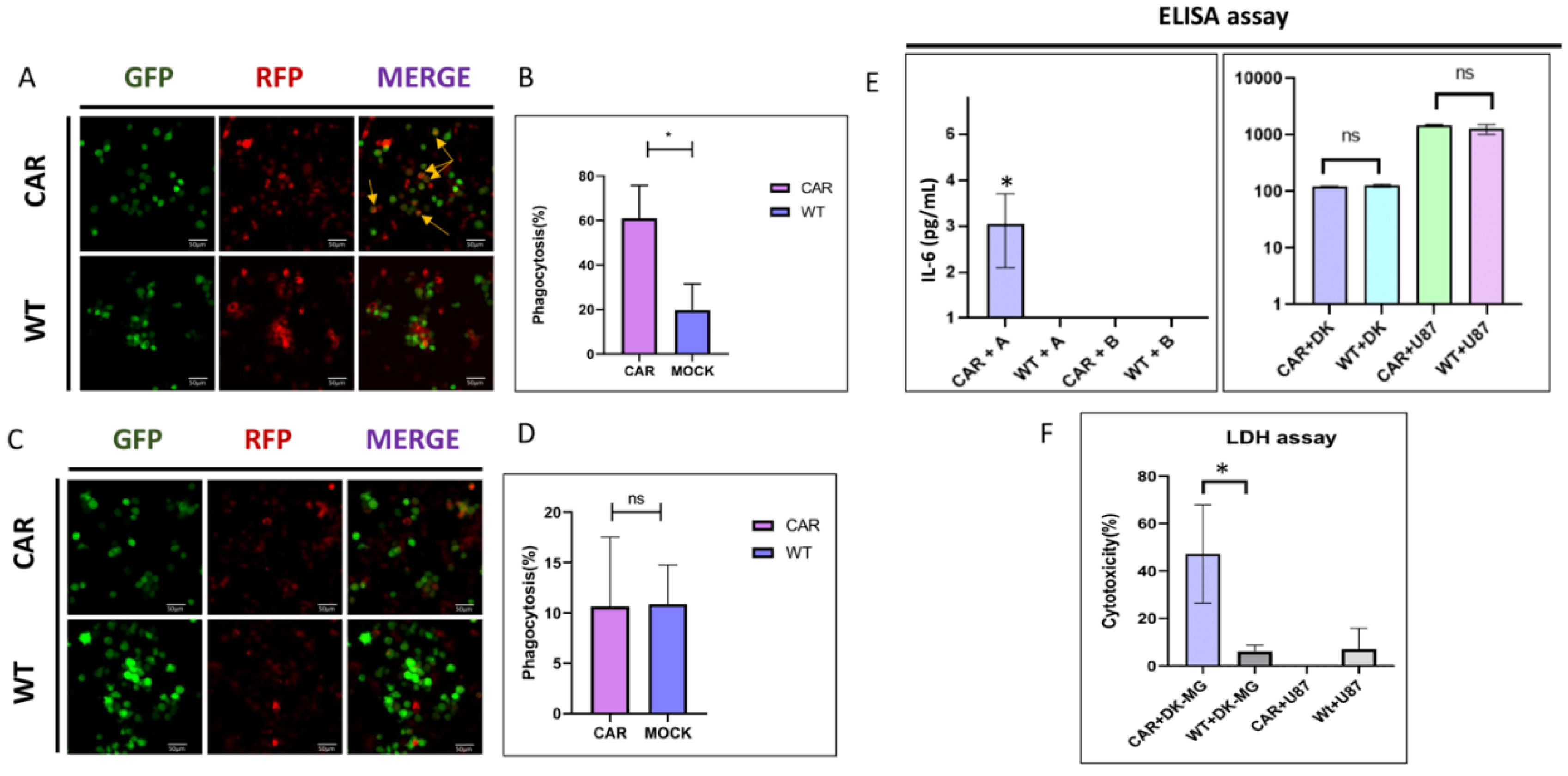

3.5. Induction of Selective Cytotoxicity of CAR-MACs in DK-MG Glioma Cells via Antigen-Specific Recognition

We next evaluated the specificity, cytotoxic efficacy and potential off-target effects of our EGFR

VIII-targeting CAR-Macrophages (CAR-Ms). Wild-type (WT) M1-polarized macrophages and CAR-M1 macrophages were co-cultured, as described earlier, with either DK-MG-EGFR

VIII cells (target-positive glioma line) or U87 cells (EGFR

VIII-

negative glioblastoma line) (

Figure 4A). Co-cultures were maintained for 40 hours at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 10:1, after which multiple complementary assays were conducted to evaluate macrophage effector function (Supplementary Video 1-4).

Confocal microscopy enabled direct visualization of phagocytic activity. As shown in

Figure 4 (A-B), Macrophages Expressing EGFR

VIII-CAR exhibited robust phagocytosis (>65%) when co-cultured with DK-MG-EGFR

VIII cells, whereas WT macrophages showed limited phagocytic engagement with either DK-MG or U87 cells (~10% and ~15%, respectively) (

Figure 4A). In contrast, CAR-Ms co-cultured with U87 cells displayed minimal phagocytosis (<5%), a rate comparable to WT controls, thereby confirming the high antigen specificity of the CAR-M construct (

Figure 4B). To further validate these findings, we extended the analysis to an additional non-neural, EGFR

VIII-negative tumor cell line, A549 (lung adenocarcinoma). The same experimental design was employed, and phagocytosis rates remained low and comparable to U87 co-cultures, with residual uptake not exceeding 15–20%, indicating minimal off-target internalization (Supplementary Figure 2).

3.6. Detection of Inflammatory Cytokines and Selective Cytotoxicity

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays were performed to quantify cytotoxicity (

Figure 4D). Consistent with the phagocytosis data, we observed significative cytotoxicity (>70%) in CAR-Ms co-cultured with DK-MG-EGFR

VIII cells, whereas LDH levels in other conditions remained near baseline, further supporting antigen-dependent activation and target cell killing.

To characterize the inflammatory milieu of the co-cultures, we measured the levels of key pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-6) via ELISA after 40 hours. Among these, IL-6 was particularly elevated in the CAR-M + DK-MG condition (2.56 pg/mL), indicating a proinflammatory response correlated with antigen engagement (

Figure 4C).

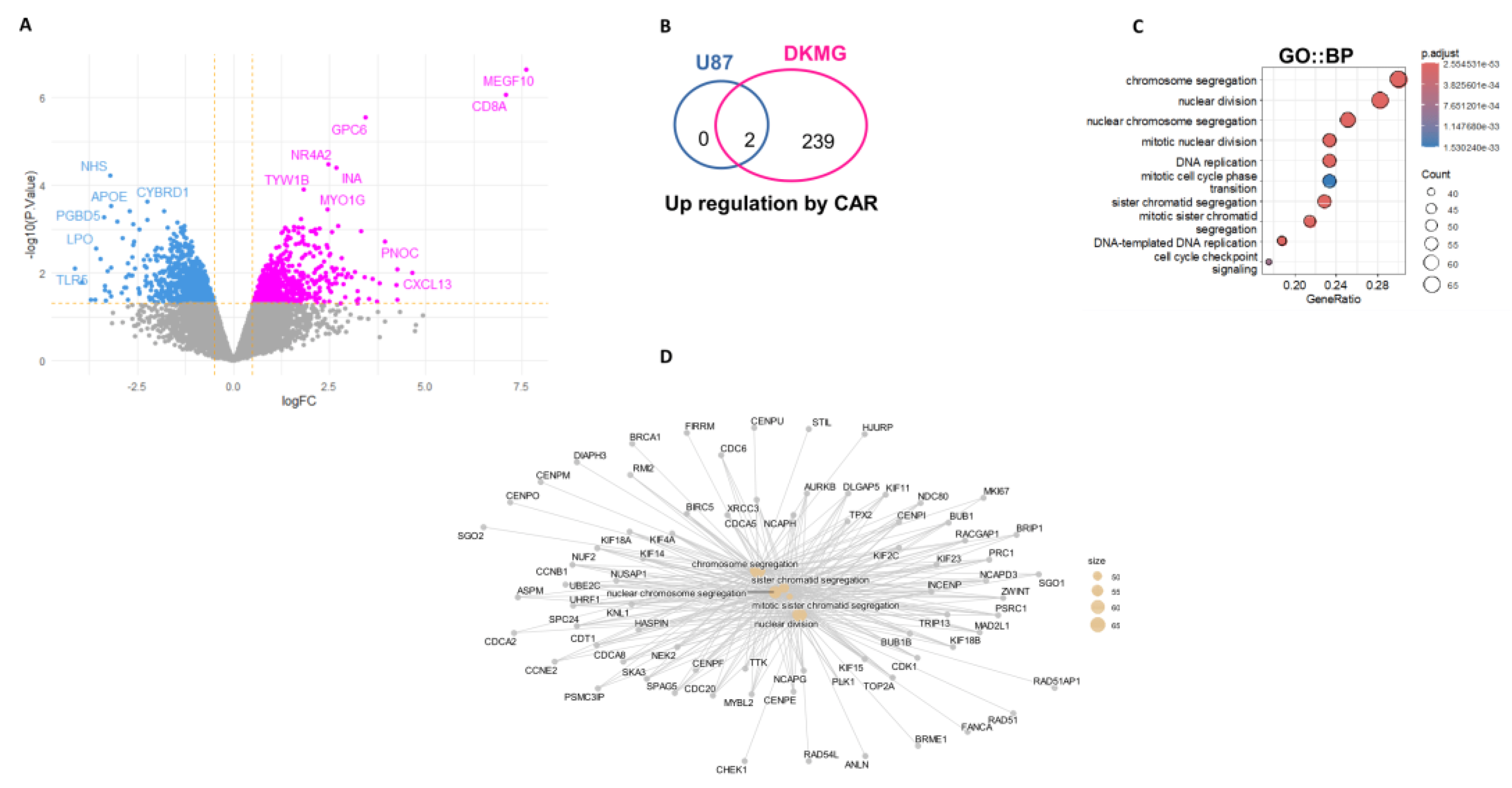

3.7. Transcriptome Analyses of CAR-Macrophages Purified After Co-Culture with U87 and DKMG Cells

Transcriptome analyses were performed on EGFR

VIII et MOCK CAR-macrophage before and after co-culture with target cells. Differential expression analysis was performed between the two experimental conditions (

Figure 5A). This analysis revealed great over expression of CD8A(signal peptide) and MEGF10 in specific CAR-macrophage conditions versus its MOCK control. Increase of last exon expression in MEGF10 was confirmed in CAR-macrophage as compared to its MOCK control by inspection of bigwig files obtained by bam-coverage after RNA-sequencing alignment (Supplemental Figure 3B). RNA-sequencing performed on MOCK or CAR sorted macrophages after coculture with cancer cells with or without EGFR

VIII mutation confirmed overexpression of CD8A and MEGF10 (

Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 3C). Similar exploration of EGFR

VIII CAR effect against DK-MG GBM (EGFR

VIII target) has shown specific over expression of 239 genes (

Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 3D, supplemental Table 1). After functional enrichment performed on Gene Ontology Biological Process database, it was observed that these molecules are mainly implicated in chromosome segregation, nuclear division, mitotic process as well as DNA replication (

Figure 5C and

Figure 5D). In opposite, 100 genes were found to be specifically repressed in CAR EGFR

VIII after coculture with DK-MG (Supplemental Figure 5E and Supplemental Table 1). After functional enrichment of these repressed genes on Gene Ontology Cellular component database, some of them were found to be implicated in presynaptic active zone (Supplemental Figure 3F and Figure 3G). These results suggested the presence of proliferative genomic GBM targets internalized in CAR-EGFR

VIII macrophages detected by transcriptome analysis.

4. Discussion

In this work we report the use of an original CAR-mediated tumor targeting strategy using macrophages. Chimeric antigen receptor expressing macrophages (CAR-Ms) have rapidly emerged as a compelling alternative to CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies for targeting solid tumors. Early CAR-M constructs leveraged intracellular signaling domains from immune activators such as CD3ζ or FcRγ, and more advanced “second generation” versions incorporated co stimulatory motifs alongside CD3ζ to boost macrophage activation [

7]. To overcome the potential risks of uncontrolled pro-inflammatory cytokine production due to an alteration of the pro-inflammatory mechanism of macrophages, we hypothesized that harnessing macrophages’ endogenous phagocytic pathways could yield CAR-Ms that maintain effector competence while avoiding hyperinflammation and preserving immune homeostasis. This approach supports both direct effector engagement (phagocytosis) and indirect antigen-presentation functions, maximizing tumor-targeted responses with minimized side effects. Among phagocytosis-linked receptors, Multiple EGF-like-domains 10 (MEGF10) was identified as an optimal signal domain. Earlier studies have shown that MEGF10 significantly enhances phagocytic capacity in multiple myeloid models [

26]. Accordingly, we engineered a MEGF10-based CAR macrophage targeting EGFR

VIII, a mutated form of the epidermal growth factor receptor frequently overexpressed in solid tumors (NSCLC, breast cancer, glioblastoma, and ovarian cancer). This antigen selection capitalizes on EGFR

VIII’s oncogenic exclusivity and expression in EGFR

VIII-high tumors, ensuring both specificity and strong clinical relevance [

27].

To determine the functional effects of this strategy, we have used macrophages generated from the THP-line which was successfully transduced with our CAR-EGFRVIII construct. The availability of this cell line allowed reproducible generation of monocytes and macrophages. We have thus produced in vitro CAR-Ms able to target GBM tumor cells with EGFRVIII mutations. Using confocal and videomicroscopy analyses, we have shown the specificity and higher avidity of our CAR-M macrophages targeting EGFRVIII-mutated GBM cell lines as compared to non-mutated GBM cell line. To determine the immunological consequences of CAR engagement, the cytotoxic potential was also assessed via measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in the co-culture supernatants, serving as a biochemical readout for tumor cell membrane disruption. We therefore analyzed by ELISA levels of key inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 as well as IL-1β and IL-12. This allowed us to discern antigen-specific alterations in macrophage activation profiles and to probe the inflammatory dynamics of the co-culture environment. To capture the transcriptional reprogramming associated with antigen recognition, macrophages were isolated post co-culture by fluorescence-activated cell sorting to ensure effector cell purity, followed by bulk RNA sequencing. Comparative transcriptomic profiling between CAR-Ms and WT macrophages under both target-positive and target-negative conditions revealed gene expression signatures associated with CAR activation and effector polarization, providing mechanistic insight into the downstream consequences of antigen-specific signaling. As shown in this work, our CAR-M only interacted with its target which resulted in the enrichment of DNA-segregation and cell replication signature genes. Demonstrating that our CAR-M could phagocyte successfully DK-MG-EGFRVIII cells either in steady state and during their own replication. Since macrophages are a definitive form of differentiation of monocytes uncapable of proliferating, the cell division signature found using purified-macrophage transcriptome could belong for a large part to glioblastoma cell line.

These data are encouraging and strengthen the evidences that CAR-M therapy offers several inherent benefits over CAR-T and CAR-NK approaches. Macrophages naturally infiltrate solid tumors and overcome physical stromal barriers that typically limit CAR-T efficacy. CAR Macs also exert multimodal anti-tumor effects: direct phagocytosis, pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, antigen presentation, re-education of tumor-associated macrophages (M2 → M1), and induction of epitope spreading—together addressing tumor heterogeneity and immune resistance. Their localized mode of action also minimizes systemic toxicities such as cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity.

Klichinsky et al. [

8] conducted a pivotal role towards a better knowledge and characterization of the effects of CAR-Ms in preclinical solid tumor models. This work demonstrated that HER2-specific CAR-macrophages can reprogram the TME toward a pro-inflammatory (M1-like) phenotype, stimulating T cell recruitment and suppressing tumor growth. Recently, the feasibility of clinical use of CAR-M has been shown by the HER2-targeted CAR-phase I CT-0508 trial demonstrates the feasibility of this modality

In this clinical trial including HER2 overexpressing solid tumors refractory to HER2-targeted therapies, an adenoviral vector was used to generate autologous HER2-targeting CAR-Ms. Early clinical results of this trial indicate safety, persistence of CAR Ms and enrichment of T-cells in biopsy samples but no tumor regression was observed.

Importantly, CAR macrophages have been shown to successfully avoid common pitfalls associated with CAR T cells, such as cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity, thus offering a safer therapeutic alternative. Furthermore, CAR macrophages show synergistic potential when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors [

28] overcoming suppressive signals in the TME and broadening the scope of immune activation. Comparative studies have demonstrated their superiority in tumor penetration, antigen presentation, and TME reprogramming when compared to CAR-T and CAR-NK cells, particularly in solid tumors like glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer. The development of CAR-M-based therapies represents an important evolution in adoptive cell therapy, addressing the limitations of current CAR-based treatments. Their ability to overcome the immune suppression and physical barriers of solid tumors makes them a promising option for future cancer therapies, particularly in tumors where traditional CAR-T cells have struggled to achieve meaningful efficacy.

Despite these advances, critical challenges remain. One major issue, is the sustainability of an autologous CAR-M strategies in large population of cancer patients. As macrophages are not circulating cells, their administration in vivo is problematic especially in tumors with difficult locations such as pancreas cancer. Long-term durability and maintenance of effector phenotype in the context of immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments represent additional challenges that need to be addressed. Antigen selection and off tumor toxicity risk require careful validation, potentially through the use of transient or inducible CAR platforms. Manufacturing scalability is another key consideration: development of GMP-compliant protocols and exploration of non-viral gene transfer methods could streamline production. Combining CAR-Ms with modalities such as checkpoint blockade, metabolic reprogramming agents, or stromal targeting drugs may synergize to enhance both efficacy and TME remodeling [

28]. For these reasons, the use of an off-the shelf CAR-bearing iPSC-derived macrophages could be of major interest. With regard to the difficulties of macrophage administration, the use of CAR-IPSC-derived monocytes could be an alternative.

In our strategy, preliminary results show the feasibility of our EGFRVIII-directed, MEGF10-based CAR macrophages offer a potent and precise alternative to existing CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies in the context of solid tumors, delivering efficient, antigen-specific phagocytosis while mitigating pro-inflammatory toxicity. This macrophage-centered strategy exploits innate tumor tropism and immunomodulatory capacity, and is supported by encouraging clinical translation of HER2 CAR-Ms. Future efforts will focus on the translation of this approach for iPSC-derived macrophages.