Submitted:

08 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Description

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temperature Forecast Accuracy

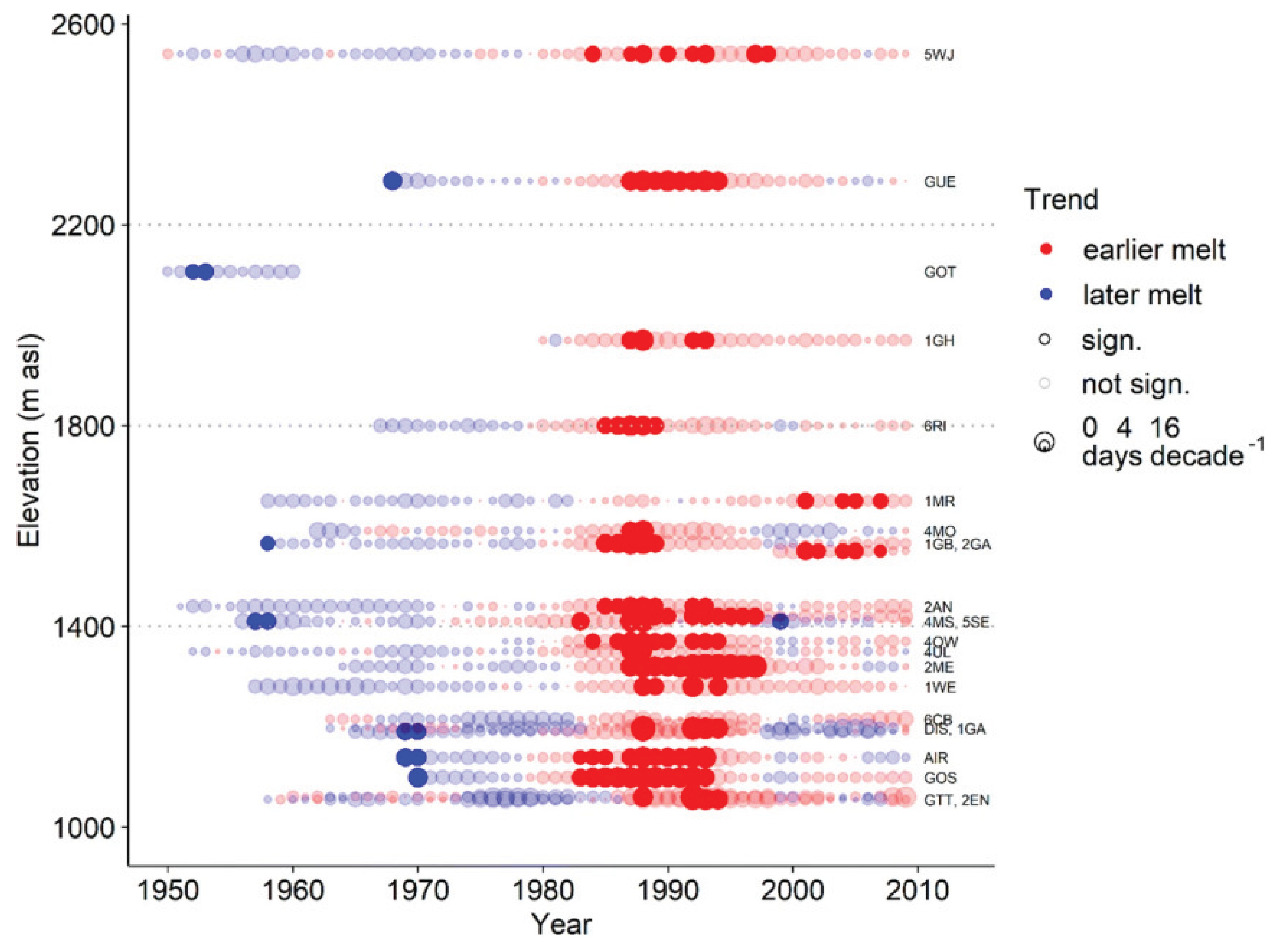

3.2. Snowmelt Dynamics

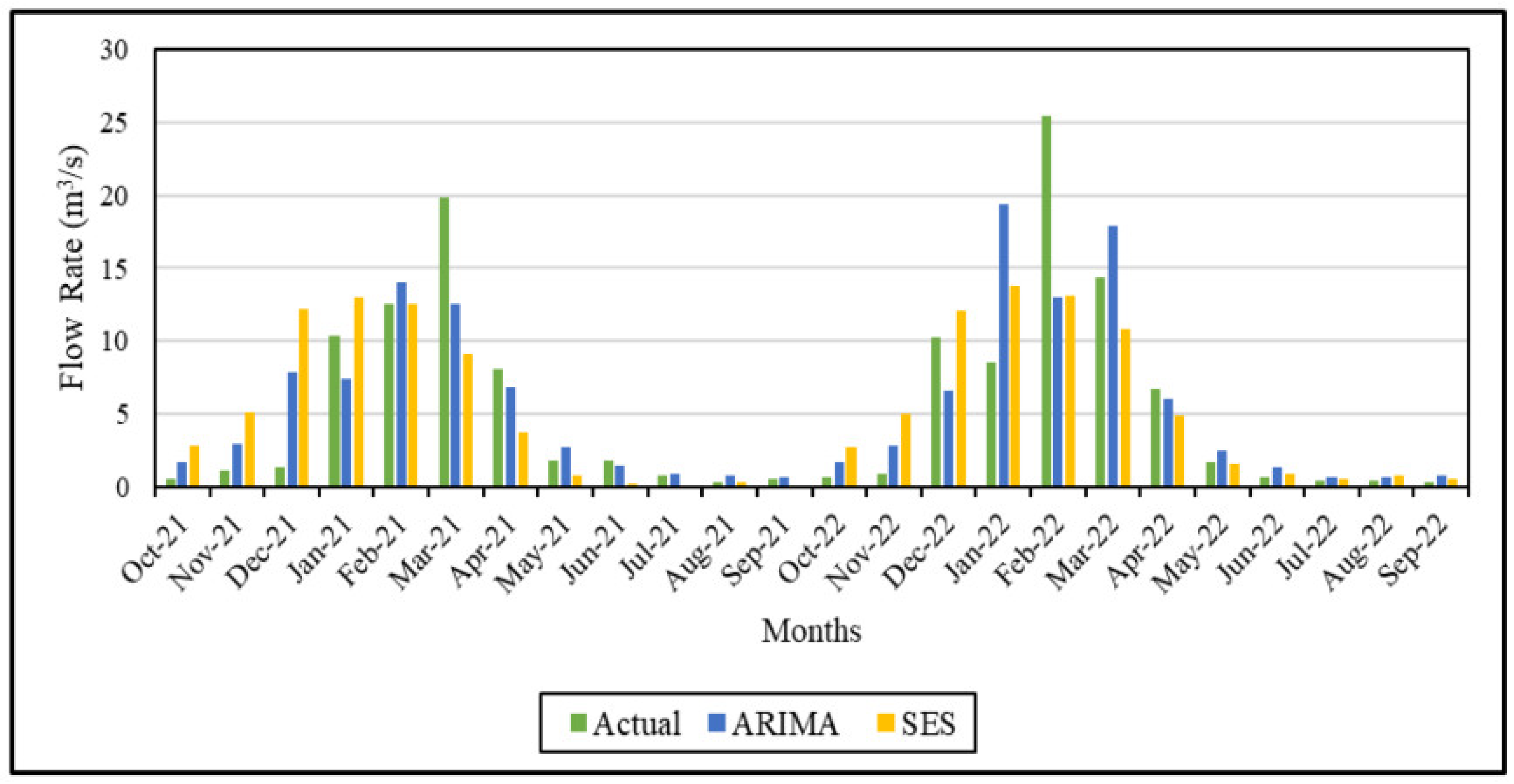

3.3. Streamflow and Reservoir Storage

3.4. Broader Implications and Future Trends

4. Conclusion

References

- Sun, X., Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Tyson, C., Longyang, Q., Neilson, B. T., Zeng, R., & Xu, T. (2023). Effects of meteorological forcing uncertainty on high-resolution snow modeling and streamflow prediction in a mountainous karst watershed. Journal of Hydrology, 619, 129304. [CrossRef]

- Colman, B., Cook, K., & Snyder, B. J. (2012). Numerical weather prediction and weather forecasting in complex terrain. In Mountain Weather Research and Forecasting: Recent Progress and Current Challenges (pp. 655-692). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Williams, R. M. (2016). Statistical methods for post-processing ensemble weather forecasts. University of Exeter (United Kingdom).

- Lerch, S., & Thorarinsdottir, T. L. (2013). Comparison of non-homogeneous regression models for probabilistic wind speed forecasting. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography, 65(1), 21206. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wen, Y., Wu, X., Wang, L., & Cai, H. (2025). Assessing the Role of Adaptive Digital Platforms in Personalized Nutrition and Chronic Disease Management. [CrossRef]

- Eckel, F. A., & Delle Monache, L. (2016). A hybrid NWP–analog ensemble. Monthly Weather Review, 144(3), 897-911.

- Owens, M. J., Riley, P., & Horbury, T. S. (2017). Probabilistic solar wind and geomagnetic forecasting using an analogue ensemble or “similar day” approach. Solar Physics, 292(5), 69. [CrossRef]

- Hemri, S., & Klein, B. (2017). Analog-based postprocessing of navigation-related hydrological ensemble forecasts. Water Resources Research, 53(11), 9059-9077. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., & Villarini, G. (2019). Examining the capability of reanalyses in capturing the temporal clustering of heavy precipitation across Europe. Climate Dynamics, 53(3), 1845-1857. [CrossRef]

- Woldemeskel, F., McInerney, D., Lerat, J., Thyer, M., Kavetski, D., Shin, D., ... & Kuczera, G. (2018). Evaluating post-processing approaches for monthly and seasonal streamflow forecasts. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(12), 6257-6278. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. J., Dettinger, M. D., Gehrke, F., McIntire, T. J., & Hufford, G. L. (2004). Hydrologic scales, cloud variability, remote sensing, and models: Implications for forecasting snowmelt and streamflow. Weather and forecasting, 19(2), 251-276. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Chakrapani, V. (2023). Photocatalytic generation of reactive oxygen species on Fe and Mn oxide minerals: mechanistic pathways and influence of semiconducting properties. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 127(48), 23189-23198. [CrossRef]

- Gorooh, V. A., Sengupta, A., Roj, S., Weihs, R., Kawzenuk, B., Monache, L. D., & Ralph, F. M. (2025). Enhancing Deterministic Freezing Level Predictions in the Northern Sierra Nevada Through Deep Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.11560.

- Eccel, E. M. A. N. U. E. L. E., Ghielmi, L. U. C. A., Granitto, P., Barbiero, R., Grazzini, F., & Cesari, D. (2007). Prediction of minimum temperatures in an alpine region by linear and non-linear post-processing of meteorological models. Nonlinear processes in geophysics, 14(3), 211-222. [CrossRef]

- He, C., & Hu, D. (2025). Informing Disaster Recovery Through Predictive Relocation Modeling. Computers, 14(6), 240. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Li, Y., Harper, D., Clarke, I., & Li, J. (2025). Macro Financial Prediction of Cross Border Real Estate Returns Using XGBoost LSTM Models. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Information, 2, 113-118.

- Muerth, M. J., Gauvin St-Denis, B., Ricard, S., Velázquez, J. A., Schmid, J., Minville, M., ... & Turcotte, R. (2013). On the need for bias correction in regional climate scenarios to assess climate change impacts on river runoff. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17(3), 1189-1204. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K., Lu, Y., Hou, S., Liu, K., Du, Y., Huang, M., ... & Sun, X. (2024). Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nature Communications, 15(1), 8223. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).