1. Introduction

Particular hydrological and environmental characteristics of cold climates and mountainous regions affect hydrologic processes and seasonal pattern. Climate change may alter the timing of peak river flows, causing a shift towards winter and early spring due to earlier snowmelt where poses significant challenges to communities residing downstream (Vuille et al. 2018; Dehban et al., 2025, Akbari et al. 2025). Additionally, in areas with low temperatures, rather than observing the formation of ice on lakes and rivers, four processes including snow, permafrost, freeze-thaw cycles, and glaciers have been comprehensively recognized and evaluated in mountainous regions (Hock et al. 2019; Baniya et al. 2024). However, not all these processes can be fully addressed in available hydrological models. Therefore, it is necessary to simplify the complication level of watershed systems and corresponding processes. On the other side, there are growing appeals for having an accurate representation of the physical reality in a watershed where it makes the research challenging with simplified models. In the past several years, advancements in snow data collection techniques have partially solved data shortage and assisted for simulating snow processes in cold climates and mountainous regions (Swalih and Kahya 2022). This field is maturing and in parallel, ongoing research have been dealing with the improvement of predictions in hydrologic models to overcome less accuracy in results due to simplification in analytical methodologies.

Hydrological models are distinguished into stochastic and deterministic models depending on their modeling techniques (Wang et al. 2021). Stochastic models rely on statistical regressions of observed data, using a series of input parameters. In contrast, deterministic models operate by representing the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy within a framework of partial differential equations and water budget balances in a system (Singh et al. 2002). In recent decades, various collaborative hydrological simulation frameworks have been developed to simulate hydrological processes within different climate and terrains (Devia et al. 2015; Panchanthan et al. 2024), sometimes includes water management tools, such as the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) (Arnold et al. 2002). SWAT is a watershed-scale, physically-based, semi-distributed model that enables different time series from daily, monthly, and annual. As a distributed hydrological model for river basins, the SWAT model has become an essential and effective tool for water resource management and environmental protection strategies (Li et al., 2021). SWAT is consisted of several modules with varying functions, offering great flexibility and versatility to adapt to different hydrological components and conditions (Wang et al. 2023).

The application of SWAT has been widely adopted in numerous studies including ones in cold regions. Jiang et al. (2020) investigated how climate change affects seasonal and annual streamflow in the Nicolet River watershed in Southern Quebec. This research revealed a 13% increase in streamflow peak each year, which was linked to the unexpected snowmelt occurred in early spring. Wu et al., (2018a&b) applied SWAT to investigate the impact of snowmelt on soil erosion in an upland watershed at mid-high latitudes. Their research was conducted in the Abujiao River Basin in Heilongjiang Province, China, and examined how temperature and precipitation influenced soil erosion patterns in a freeze-thaw watershed. These findings showed that runoff and snowmelt significantly impacted seasonal soil erosion. Cold temperatures and high rainfall can increase soil erosion in regions with freeze-thaw cycles. One of the major topics to be investigated in SWAT is model calibration in snow-dominated region that has been typically performed with using data over a year (Zhao et al. 2022; Qi et al. 2016; Meng et al. 2015), that has not given satisfactory results.

As can be seen in studies, SWAT model has weakness in calibration in cold climate and mountainous regions. Zhao et al. (2022) based on this weakness, introduced total radiation to the temperature index method to enhance the simulation of snowmelt runoff incorporating Remote Sensing data. Results showed enhanced simulation of snowmelt runoff but this study indicated limitations such uncertainties in the process of determining the snowmelt threshold, snowmelt factor, as well as in the data derived from remote sensing, which needs to be fully examined and studied. In other study, Myers et al. (2021) incorporated a simple, energy-balance ROS model into the SWAT for improved SWAT calibration and simulations of Hydrologic Extremes. This study demonstrated that by adding a ROS model to SWAT, results improved. However, the study did not explore potential challenges or limitations related to the scalability of the ROS model when applied to smaller basins or more localized hydrological contexts. In the same way, Peker et al. (2021) investigated an application of SWAT in the cold and mountainous regions in Turkey. This study showed that SWAT had inadequate performance on high-elevated catchments. A sequential calibration process was implemented. A consistent trend was observed between the continuous model and discrete point snow measurements throughout the snow season, although certain point observations deviated from their respective elevation bands during specific periods. This limitation requires collecting additional manual data points or, preferably, establishing automatic stations to continuously measure SWE or snow depth. Based on this status Liu et al. (2020) in a study assessed modification of SWAT in simulating of runoff in an alpine region in China. For improve SWAT in this study, parameters for snowmelt timing and factors which are tailored to North American conditions, were localized. simulations revealed improved daily runoff accuracy with the adjusted model. However, the results indicated that values are still lower than the actual values during the snowmelt runoff. This inconsistency is probably because only the temperature factor is considered in the degree-day factor model.

A review of existing studies suggests that cold climates and other factors, such as snowmelt, shape hydrological parameters in cold regions. These changes are critical for hydrological trends and water resource management, underscoring the importance of modeling hydrological processes and assessing models in cold climates. Overall, this research aims to first apply and evaluate the performance of the SWAT model in the cold climates as the Azna-Aligoudarz Basin in western Iran. Then, the introduced approach by the authors of this research as called with “warm period” for model calibration have been assessed in detail increase result’s accuracy, and finally, the modification for snow-melting process with identified temperature threshold has also been evaluated within the available dataset.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, after meeting the modeling requirements, the observed runoff at the outlet station was compared with the model-generated runoff for the corresponding sub-basin.

Figure 6 shows trends in precipitation, observed runoff, and model output runoff, revealing that the model contains errors in simulating runoff at the outlet station. These differentiations are noticeable in difference between Dashed line and solid line.

To calibrate the model, the observed discharge from hydrometric stations was first compared to the simulated discharge. According to calibration theory, the key parameters that are present in SWAT model for calibration, are known at the beginning, which allows for efficient model calibration.

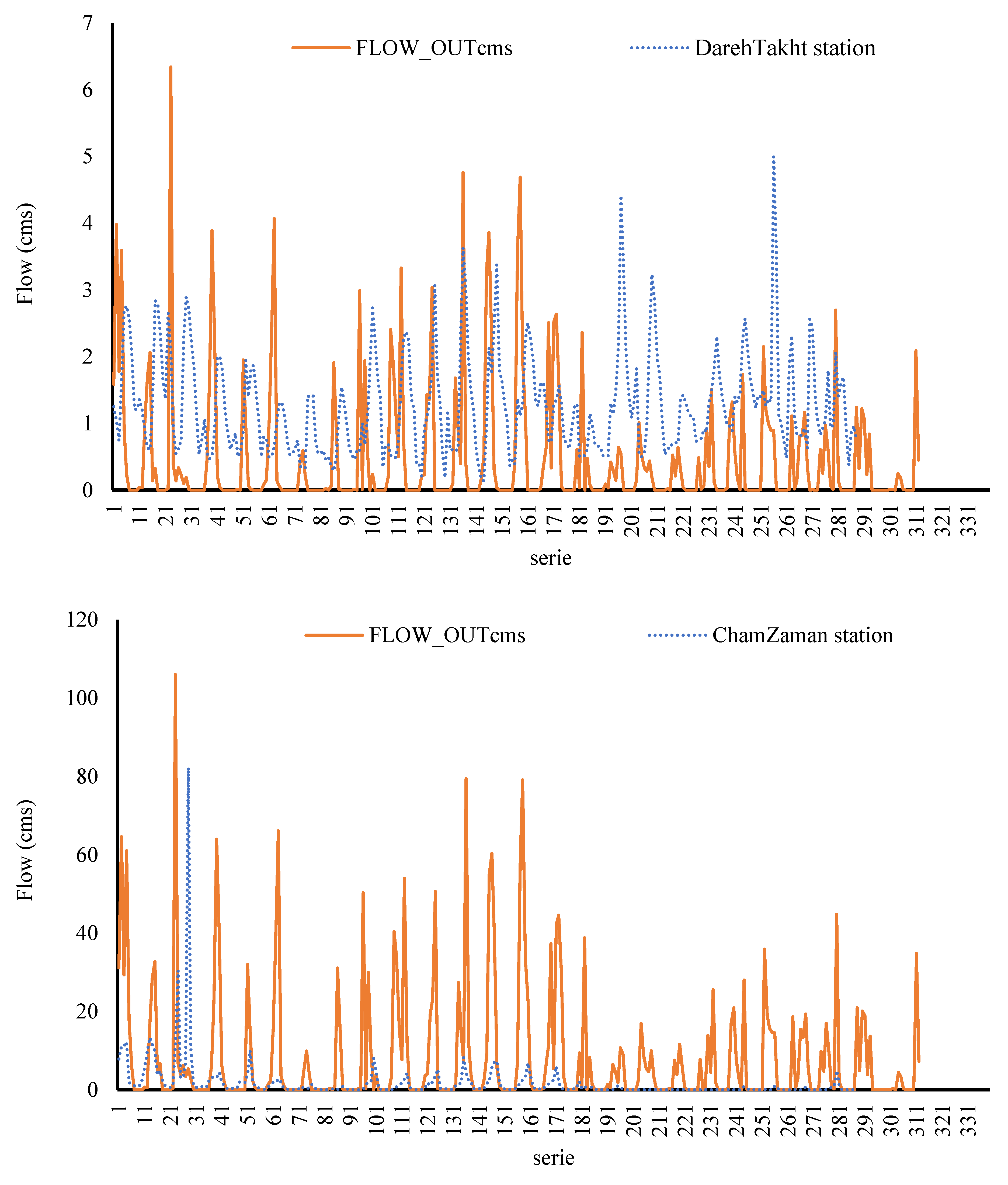

Figure 7 shows observed flow rate changes over time at four hydrometric stations: Dareh Takht, Cham Zaman, Kamandan, and Marbare, compared with the model’s simulations for each sub-basin. These graphs highlight a significant discrepancy between observed and simulated values, showing low base flow and high surface runoff in simulated values. Consequently, parameters related to infiltration, interflow, and base flow recession have been calibrated at first in the SWAT-CUP model.

At this point, the calibration stage of model was done. Despite running the model approximately 120 times with 500 simulations and conducting sensitivity analyses on various parameters, the calibration results remained unsatisfactory. The best results achieved were NS = 0.28 and R² = 0.32 (

Table 6).

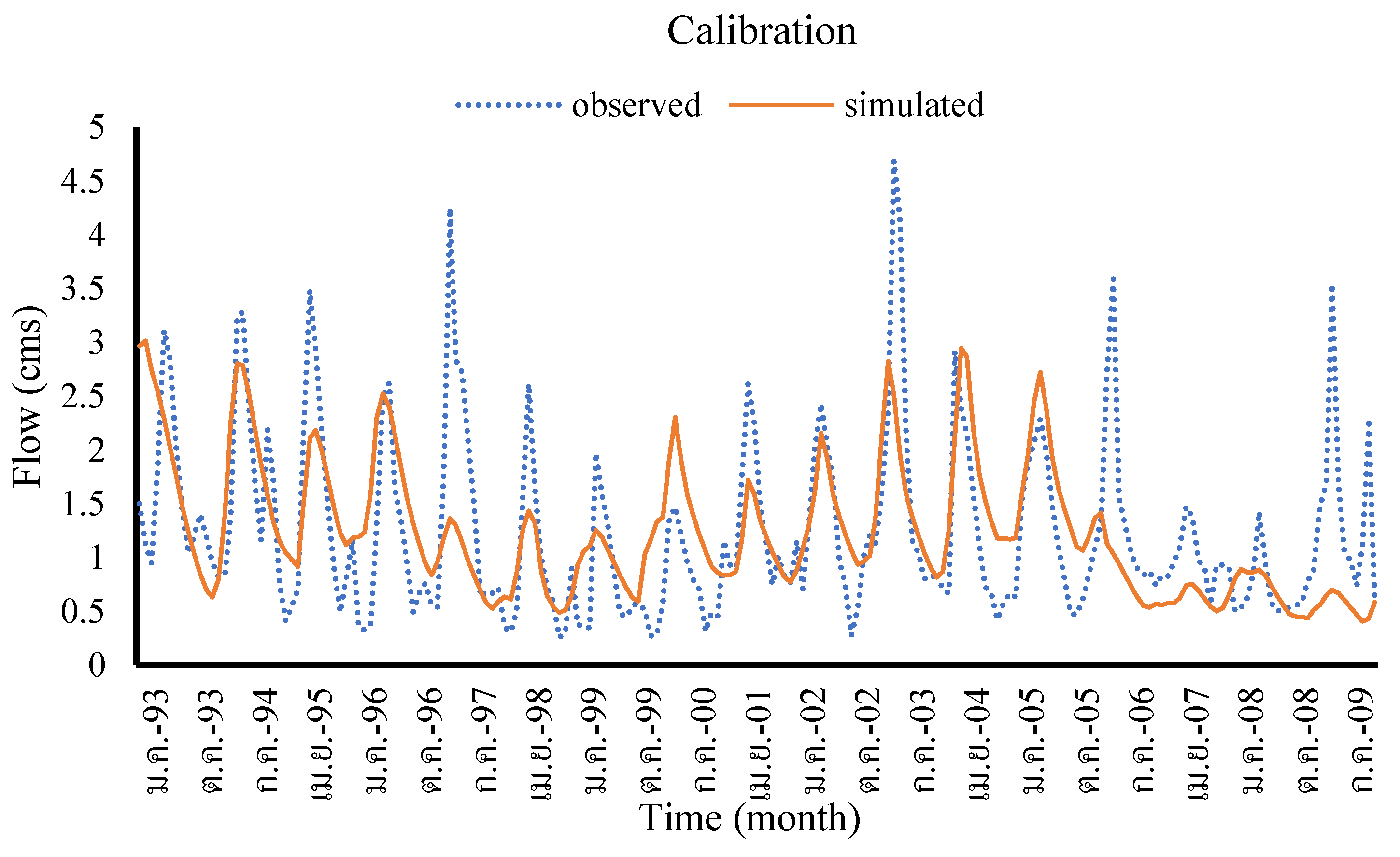

Figure 8 illustrates the calibration results for the 1993-2009 period, where the model struggled to accurately predict observed flow rate changes in most areas.

Following the unsuccessful calibration, available data including temperature, precipitation, and discharge have been analyzed to find the relationships between these variables and further investigate reasons of failure. Results showed that observed values from four hydrometric stations alongside corresponding sub-basin data. This analysis revealed instances where, despite rainfall, negative temperatures indicated snowfall. Meteorological data from the synoptic station also confirmed these snow events. During such periods, discharge from the hydrometric stations did not increase, reflecting the impact of snowfall. Over time, however, discharge rose as runoff from snowmelt occurred. Analysis of the modeled data showed that in snow-affected areas, the model incorrectly converted all precipitation into runoff, treating it as rain and failing to account for snow. Further analysis of the aquifer and underground streams revealed no impact on surface water during the event. Hence, the model’s inability to simulate runoff from snowmelt was identified as the primary source of error.

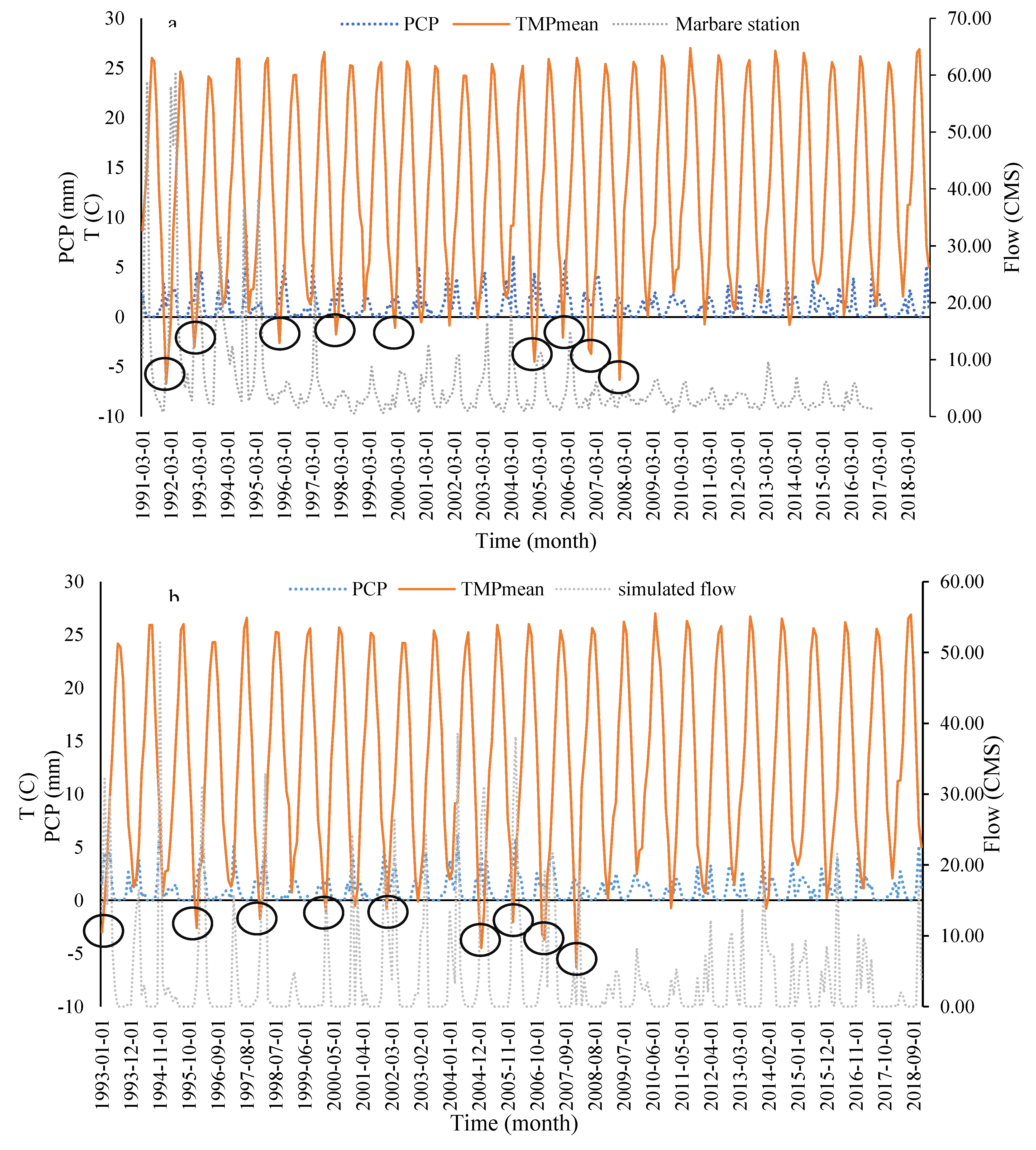

To support this argument,

Figure 9a shows observed rainfall, temperature, and discharge at the Marbare station, representative of the four study stations.

Figure 9b shows the model’s calculated values. At Marbare (the basin outlet), the model overestimated flow during high rainfall periods and underestimated flow during medium and low rainfall periods. Overestimated flow occurred between November and April (late autumn to early spring), while underestimation mainly occurred in summer. The model’s overestimation was linked to high precipitation and its assumption that all precipitation directly becomes runoff, neglecting snow effects, particularly from the snow-covered Oshtorankouh mountains. On the other hand, underestimation during low rainfall periods resulted from the model’s inability to predict runoff from snowmelt at the end of the rainy season. Zhao et al. (2022) in their study that evaluated SWAT in simulating of runoff in a cold region, resulted that in low flow regimes, the snowmelt runoff is largely underestimated by the SWAT model setting for both the calibration and validation periods. This shows weakness of SWAT in snowmelt runoff simulation specially in small snowmelt runoffs. Myers et al. (2021) in a study that used SWAT in runoff simulating for a cold climate, resulted that SWAT model simulated almost no snowmelt in December through February. Also, SWAT model tended to have later peak mean monthly snowmelt timing in April and May. While based on observational data of region, April and May have less snowmelt than the SWAT since its snowpack has already been melted. Liu et al. (2020) in a study for improve SWAT for snowmelt runoff simulation, showed that the model has underestimation of maximum runoff values and lag in the simulated compared to observed time series, specially, during the snowmelt runoff period from March to April, the daily runoff simulation value is relatively low, and sometimes no runoff is generated at all. As can be seen, these results confirm this study result in weakness of SWAT in cold climate regions and SWAT simulate peaks lower and has delay in periodical runoff trend. So, give approaches to improve the model is required.

For further analysis, data was divided into warm (no snow) and cold (with snow) seasons by identifying the snowfall and snowmelt threshold temperatures. This was achieved by analyzing minimum and maximum temperatures, precipitation, and snowfall occurrences at the synoptic station for the study period from 1991 to 2023. A threshold temperature of 3.6°C for snowfall (based on minimum temperature) and a 0°C threshold for snowmelt temperature based on maximum temperature, were established for potential improvement in the accuracy of simulations during calibration process.

According to the above-mentioned finding, observed data have been categorized into cold (with snowfall) and warm (without snow) seasons. The model calibration continued using only warm-season data. Initially, the 3.6°C threshold temperature was used to attribute months to relevant seasons. It was observed that temperatures dropped below this threshold in multiple months, attributing November to May as the cold season. Snowmelt events, based on maximum temperature, also occurred during this period, particularly in March and April. This further justified the classification into seven cold months (November-May) and five warm months (June-October). Calibration proceeded using only warm-season data, with a total of 500 simulations, sensitivity analysis, and testing of various parameters. Ultimately, 22 parameters were selected, with TLAPS and SMFMN having the greatest impact on runoff. Chanda et al. (2025) in a study simulated streamflow in a mountainous region in India, and resulted that 22 hydrological parameter are effective on streamflow and TLAPS has the most impact. The minimum, maximum, variable type (include multiply which multiply the previous value by the suggested number which is less than 1, and replace which before value replaced by suggested value), and optimal values for these parameters are reported in

Table 5.

Using the optimal parameters and statistical criteria established for the SWAT model in this research, the calibration of monthly runoff data from 1993 to 2016 resulted in R² and NSE values of 0.61 and 0.60, respectively (

Table 6). Additionally, this table shows that the R² and NSE values for the validation stage were 0.78 and 0.56, respectively, where have been greatly improved in comparison with using complete dataset for the whole period in year. These values show a 91% improvement in R

2 and More than twice improvement in NSE for calibration stage of both scenarios. Zhao et al. (2022) adding solar radiation to degree day factor of SWAT in a cold region, showed 0.07% and 0.16% improvement in R

2 and NSE, respectively. Myers et al. (2021) incorporated an energy-balance Rain-On-Snow model into the SWAT for improve snowmelt runoff simulation in a snow dominated area, and showed that adding Rain-On-Snow model helped the SWAT to simulate snowmelt runoff more than unmodified SWAT and improved the monthly delay of peak snowmelt runoff. Liu et al. (2020) localized snowmelt date and snowmelt factor parameters in SWAT that are set according to the North American values. Their results showed better accuracy but this improvement is not large because it still demonstrates a low runoff simulation value.

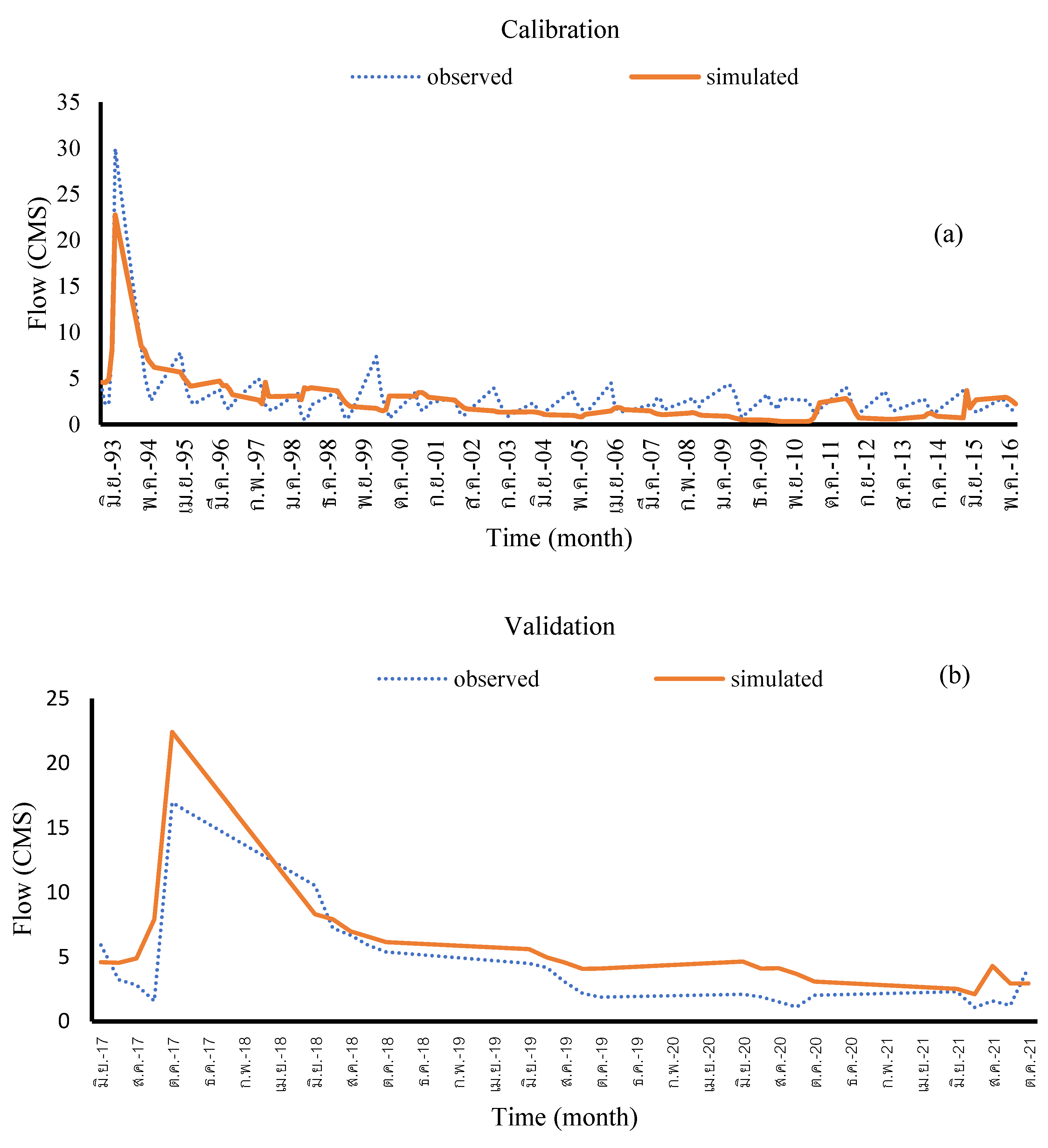

Figure 10a illustrates the calibration process for the period 1993 to 2016, while

Figure 10b shows the validation process for 2017 to 2021. These Figures indicate that the SWAT model produced satisfactory results in both stages, with a relatively good agreement between simulated runoff and observed values. In some parts of the simulation period, the rising and falling limbs of the simulated hydrographs closely match the observed values. However, in other sections, the model overestimated runoff in most months, with the slopes of the simulated rising and falling limbs being less steep than the observed values. Similarly, Das and Santra (2013) simulated monthly runoff in India’s Chilika basin using the SWAT model, achieving accuracy coefficients of R² = 0.72 and NSE = 0.54 for calibration, and R² = 0.88 and NSE = 0.61 for validation.

Table 6.

Accuracy of the model in the calibration and validation in scenario A (Calibrated based on complete dataset and Scenario B (Calibrated based on only warm period dataset).

Table 6.

Accuracy of the model in the calibration and validation in scenario A (Calibrated based on complete dataset and Scenario B (Calibrated based on only warm period dataset).

| Scenarios |

Calibration |

Validation |

| p-factor |

r-factor |

NS |

R2

|

p-factor |

r-factor |

NS |

R2

|

| A |

0.14 |

0 |

0.28 |

0.32 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| B |

0.13 |

0.07 |

0.6 |

0.61 |

0.12 |

0.06 |

0.56 |

0.78 |

Based on the statistical indicators obtained in this study and using warm-period data for model calibration, it was found that the SWAT hydrological model effectively simulated runoff in the studied locality of the Karun watershed with satisfactory accuracy. Nevertheless, the evaluation of SWAT modeling in this region highlighted some weaknesses, particularly related to the area’s mountainous and cold climate, as well as snowmelt events. Of the results obtained from this study and findings from calibration and validation of model, it can be concluded that while the model performs well in dry and non-mountainous climates, its performance is weaker in cold and mountainous regions since snow have dominated the hydrology behavior of a regions. (Zhang et al., 2015),

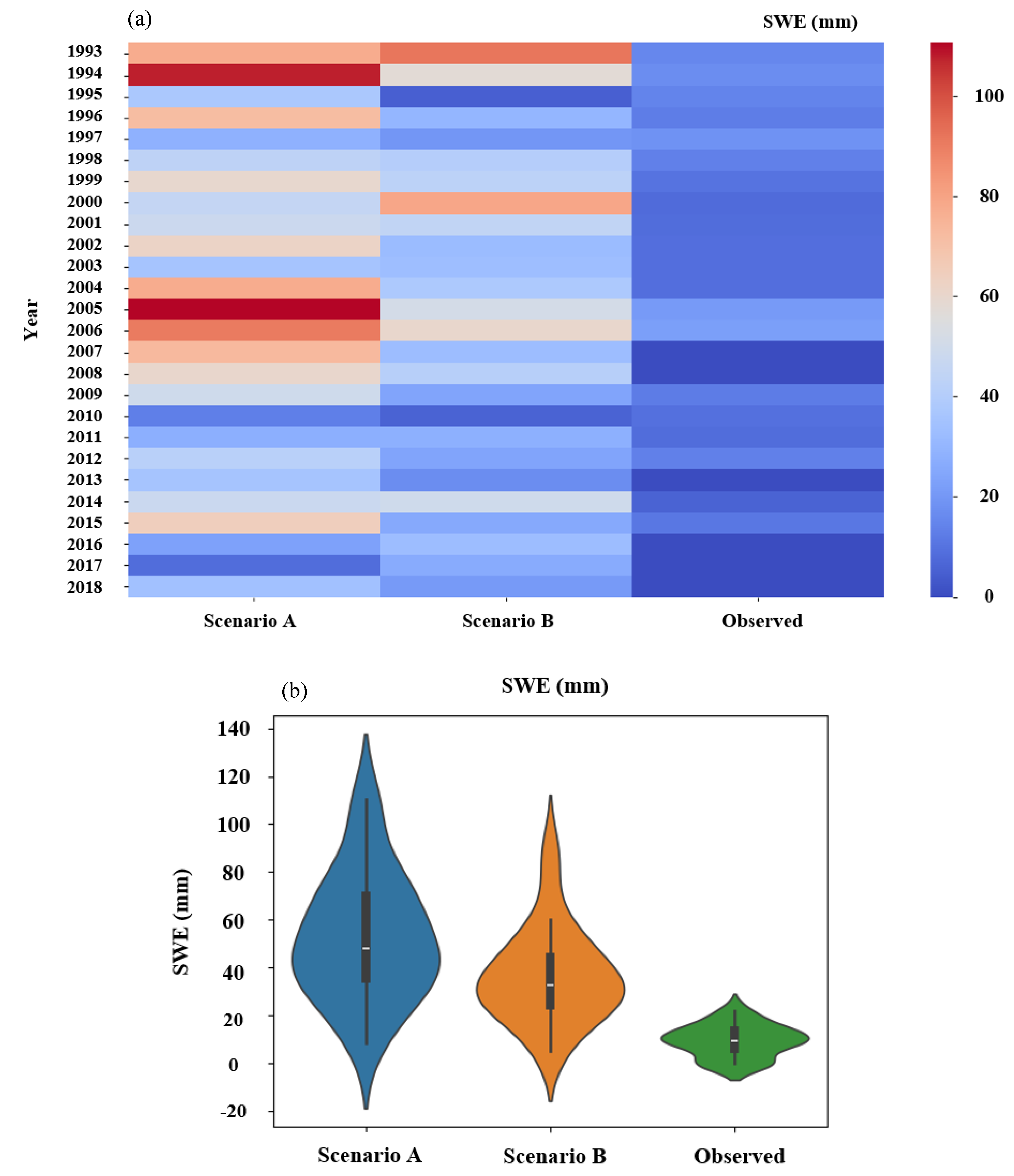

To compare the performance of the model and highlight the importance of considering snow-related processes in runoff simulation, the simulated snowmelt and snowpack values in two calibration scenarios (scenario A: calibration using complete information in the year and scenario B: calibration using only warm season data) in the outlet sub-basin of the basin were compared with the observed data at the station located at the outlet of the basin. The heat map (

Figure 11) shows the snowpack values of the two calibration scenarios and observed data at the basin outlet. Based on

Figure 11a, scenario A predicted values of more than 110 mm, which significantly differs with the range in the observed values of snowpack. The performance of model is improved in scenario B, where the simulated snowpack is closer to the actual snowpack of the basin.

To statistically examine the series of observational and simulated snowpack data under the two calibration scenarios, the violin plot of this parameter is also presented in three cases (

Figure 11b). According to this figure, the actual snowpack at the observatory station in outlet of basin, varied from a maximum of 0 to 22 mm, with the most frequent values between 5 and15. In scenario A, the snowpack had a wider range of values, with a maximum of 110 and a minimum of 8.5 mm, with values of 10-90 being the most frequent, while in scenario B, the values varied from 5 to 91 mm, with values of 5-45 being the most frequent in the series.

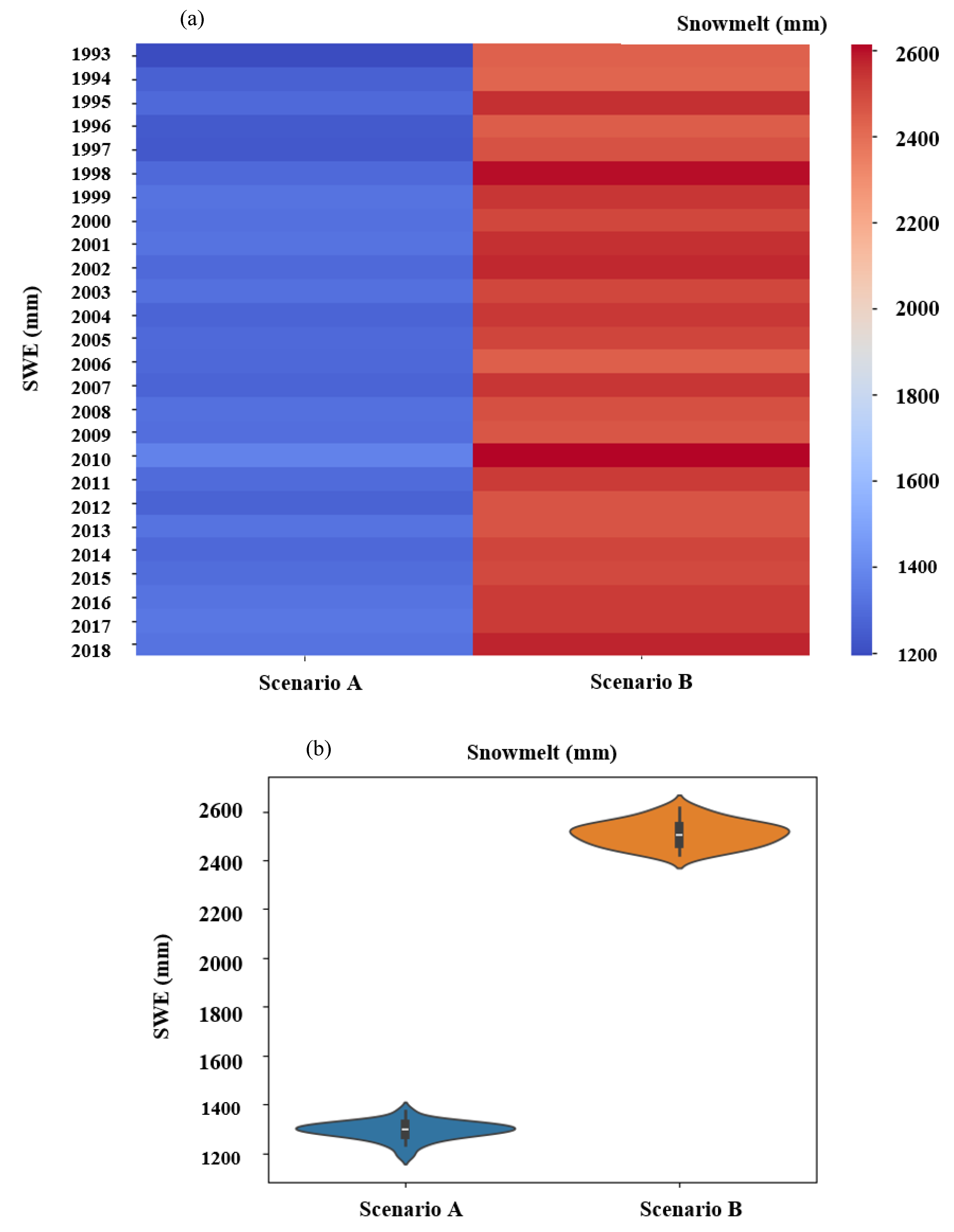

The same analysis was conducted for the simulated snowmelt in Scenario A and B (

Figure 12a). The simulated snowmelt values in scenario A are lower than those in scenario B. The model underestimated snowmelt when the entire dataset was used in Scenario A.

Figure 12b shows the probability distribution of the snowmelt under two scenarios. The values of the snowmelt in scenario B fluctuated around 2500 mm, while in scenario A the values fluctuated around 1300 mm.

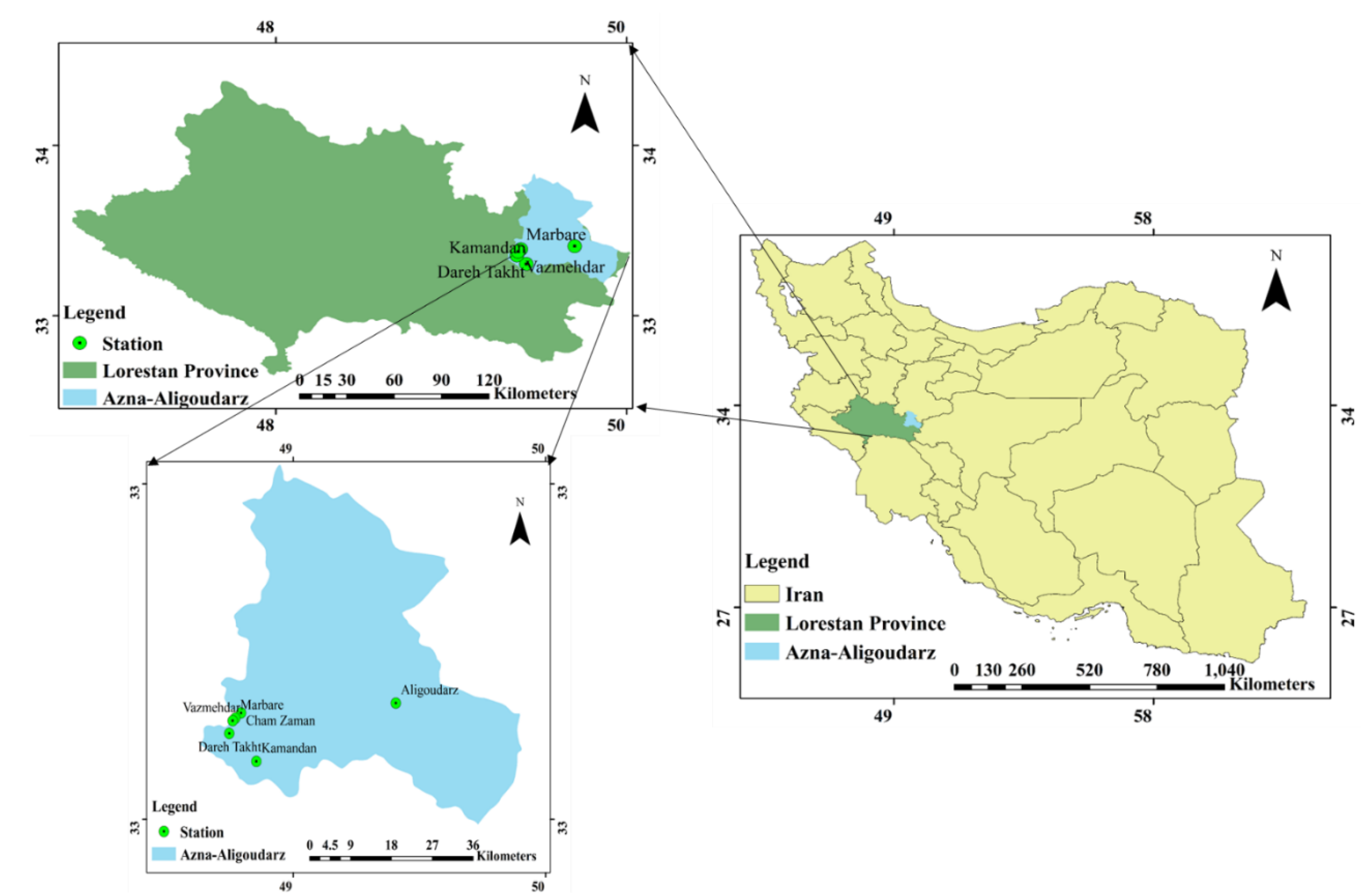

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Azna-Aligoudarz basin in Iran.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Azna-Aligoudarz basin in Iran.

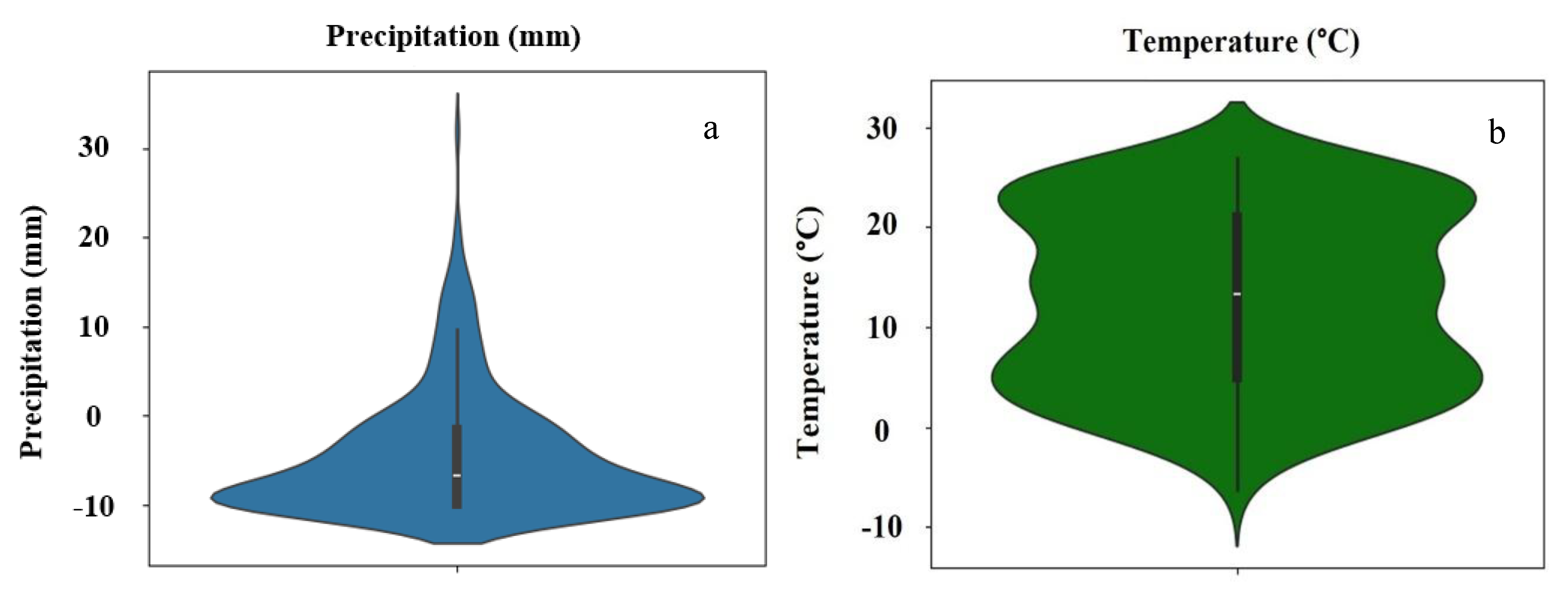

Figure 2.

(a) Monthly average precipitation distribution, (b) Monthly average temperature distribution in the period from 1993 to 2023.

Figure 2.

(a) Monthly average precipitation distribution, (b) Monthly average temperature distribution in the period from 1993 to 2023.

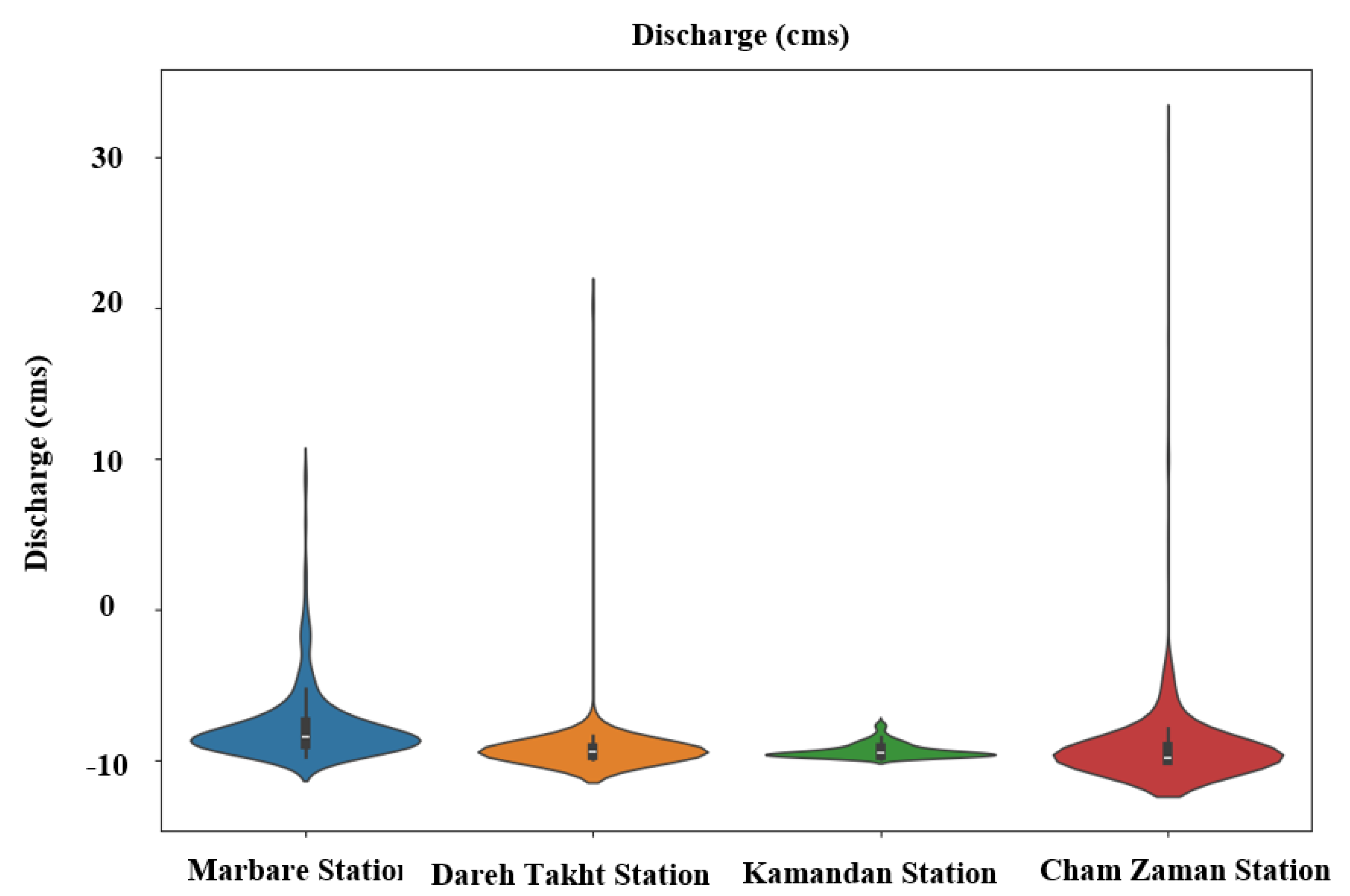

Figure 3.

Discharge distribution of hydrometric stations in the period from 1993 to 2023.

Figure 3.

Discharge distribution of hydrometric stations in the period from 1993 to 2023.

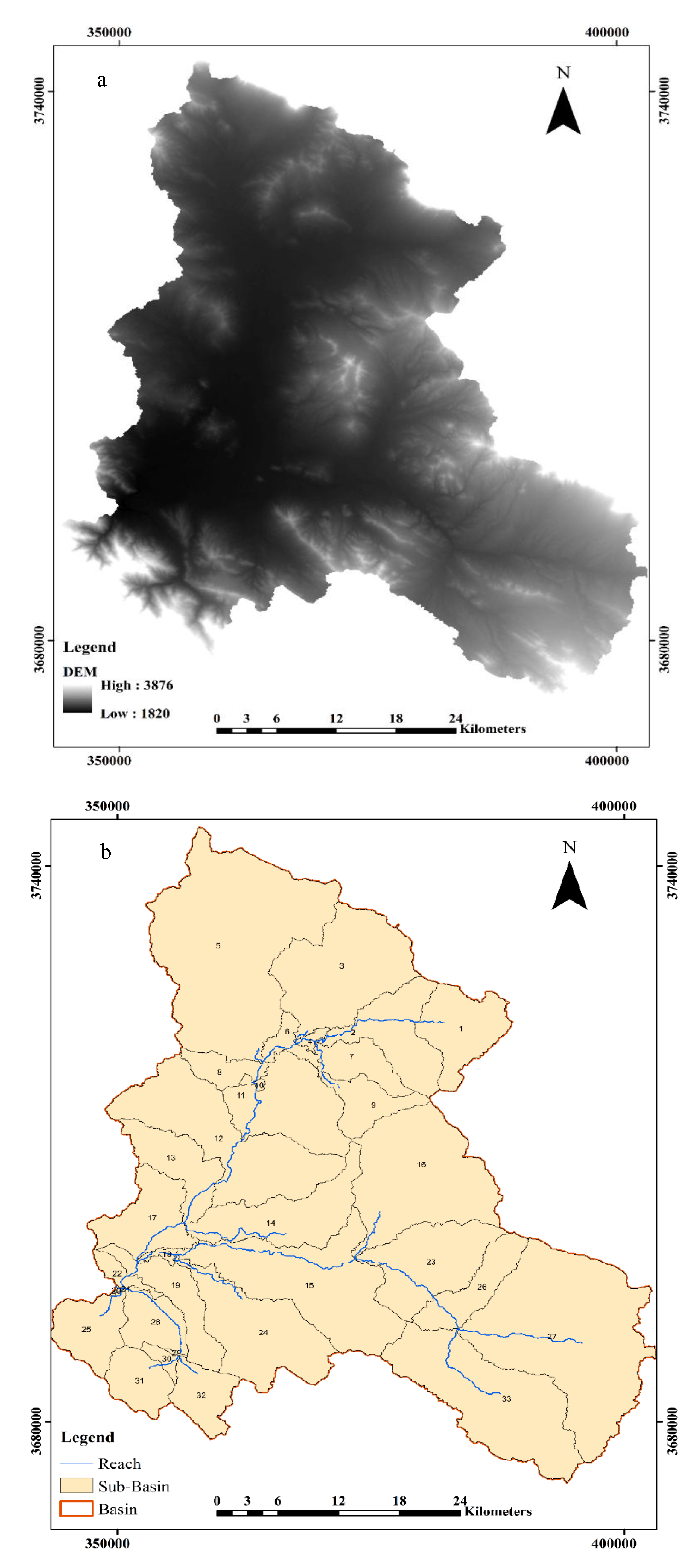

Figure 4.

Input maps of (a) digital elevation map, (b) Division of sub-basins.

Figure 4.

Input maps of (a) digital elevation map, (b) Division of sub-basins.

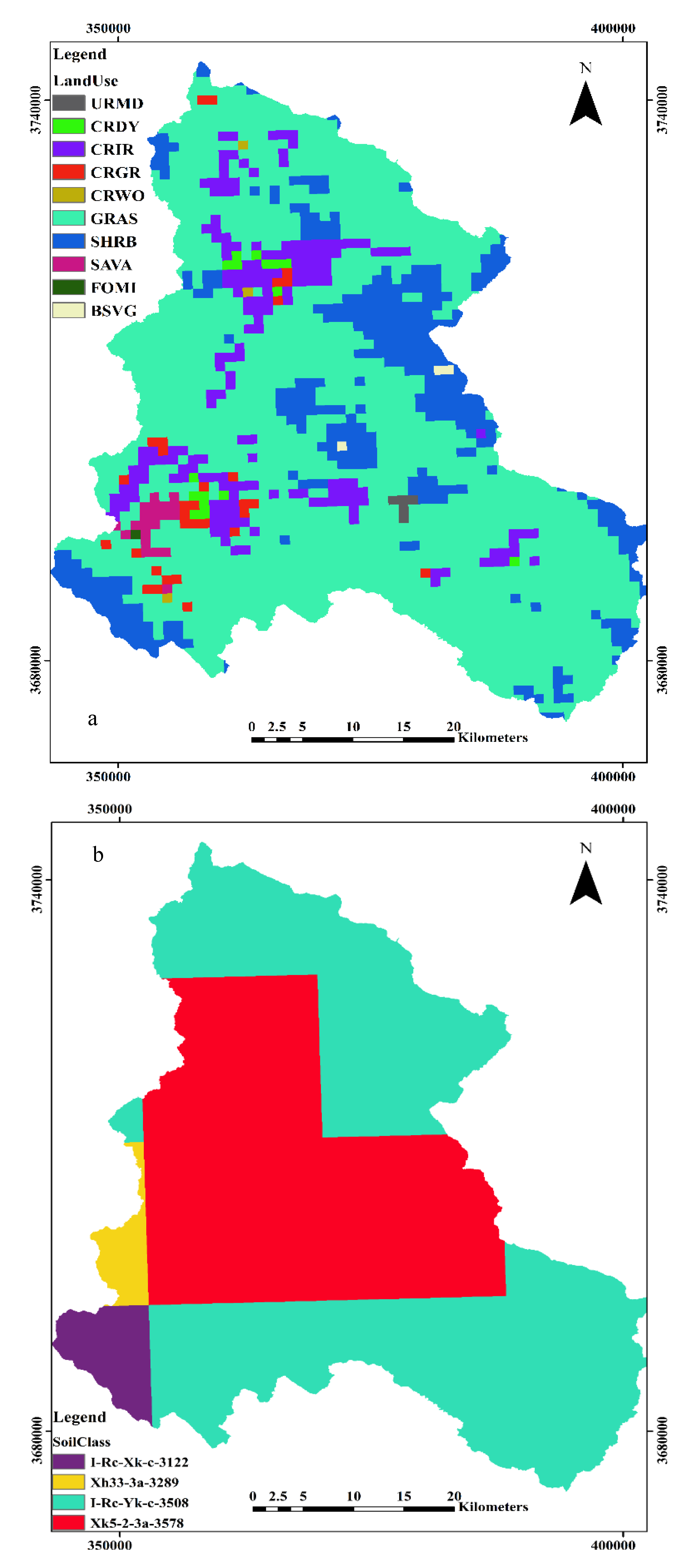

Figure 5.

Input maps of (a) Land use, (b) Soil class, (c) Slope of the study area.

Figure 5.

Input maps of (a) Land use, (b) Soil class, (c) Slope of the study area.

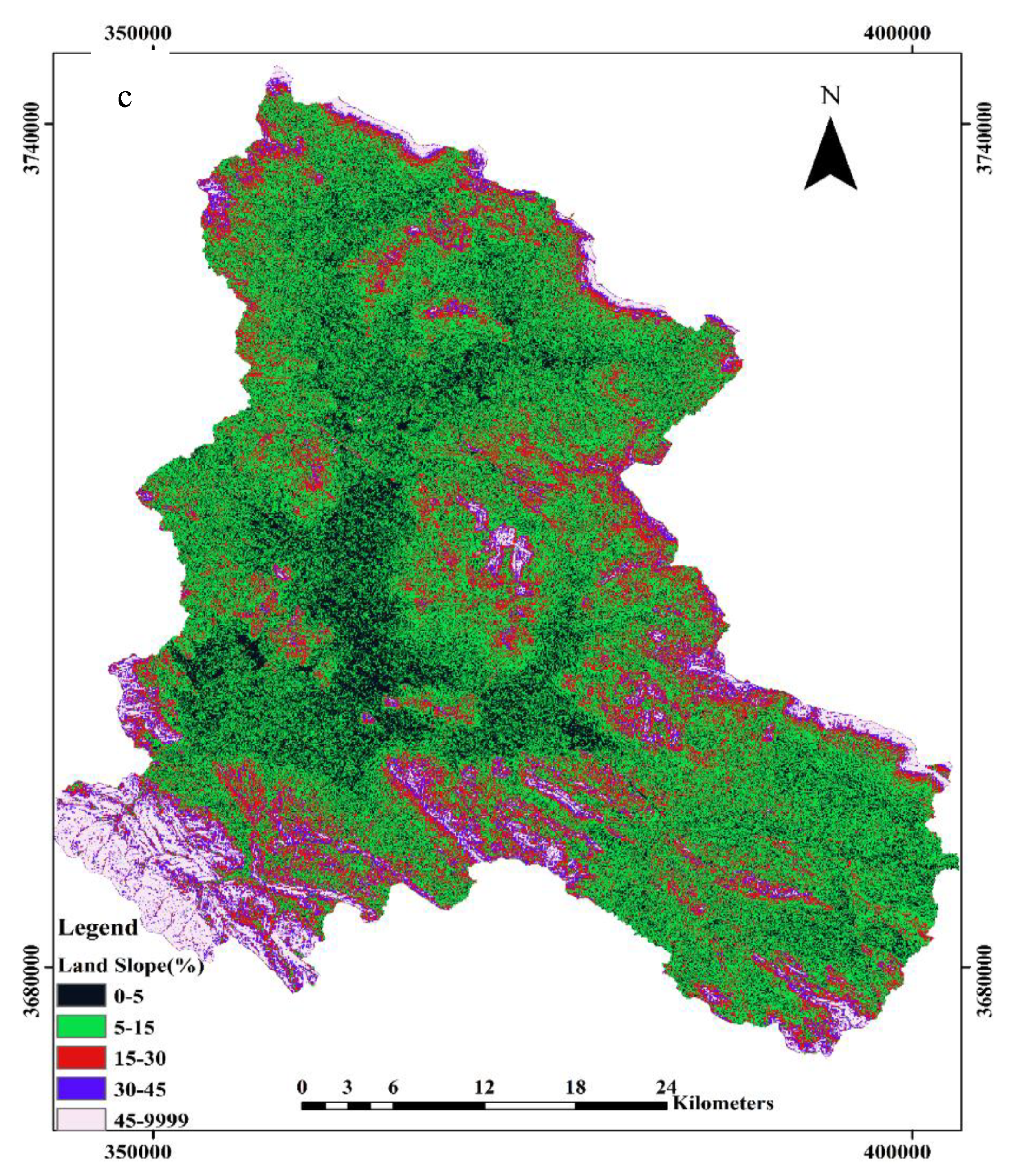

Figure 6.

Diagram of time changes of simulated runoff and observed runoff in the study area.

Figure 6.

Diagram of time changes of simulated runoff and observed runoff in the study area.

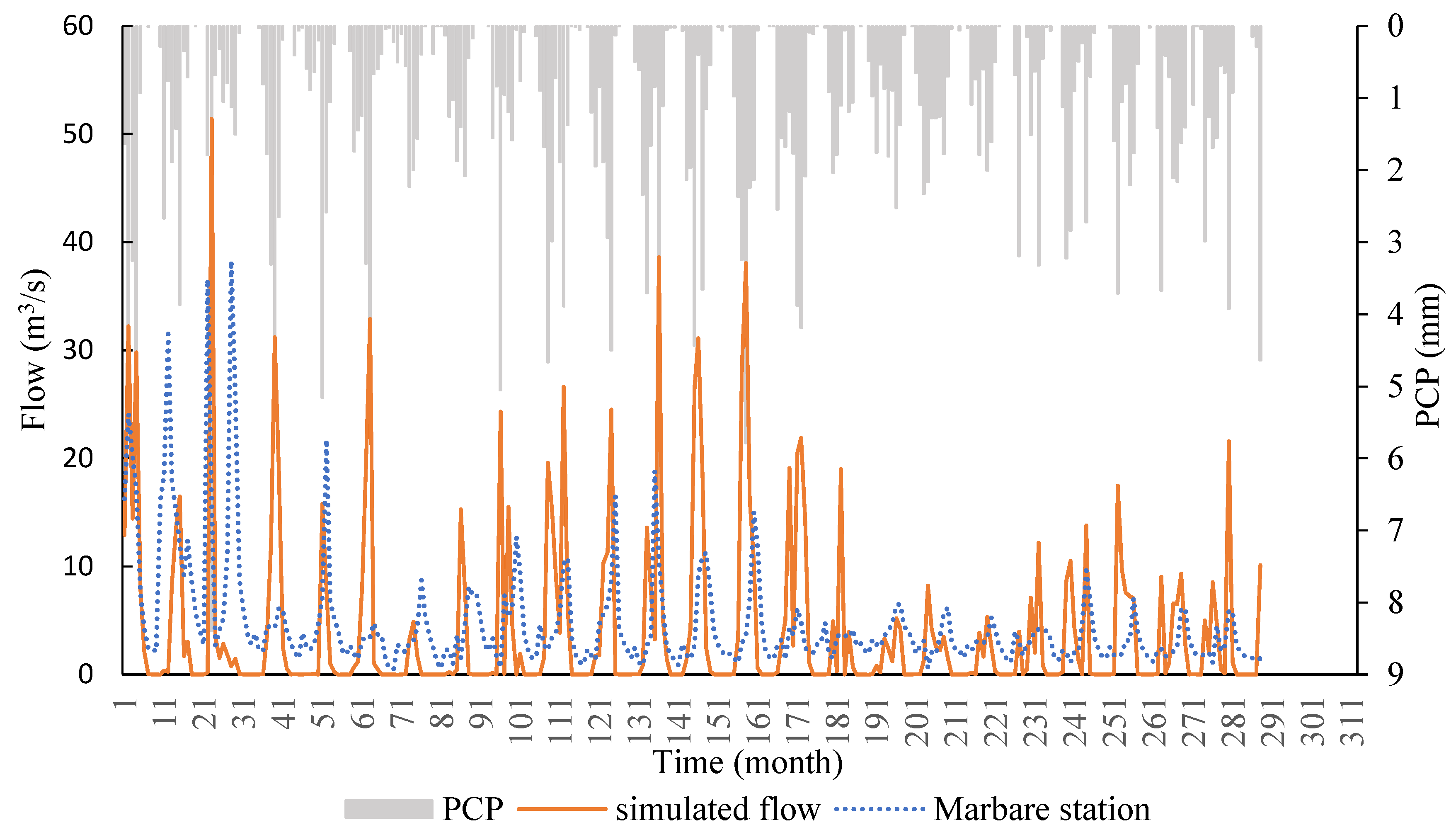

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis between simulated discharge and observed values for four stations in the studied area.

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis between simulated discharge and observed values for four stations in the studied area.

Figure 8.

Variations in observed and simulated runoff the studied area within time span 1993-2009 using full dataset.

Figure 8.

Variations in observed and simulated runoff the studied area within time span 1993-2009 using full dataset.

Figure 9.

Variations in observed precipitation, temperature and discharge at Marbare station (a), and in simulated discharge (b).

Figure 9.

Variations in observed precipitation, temperature and discharge at Marbare station (a), and in simulated discharge (b).

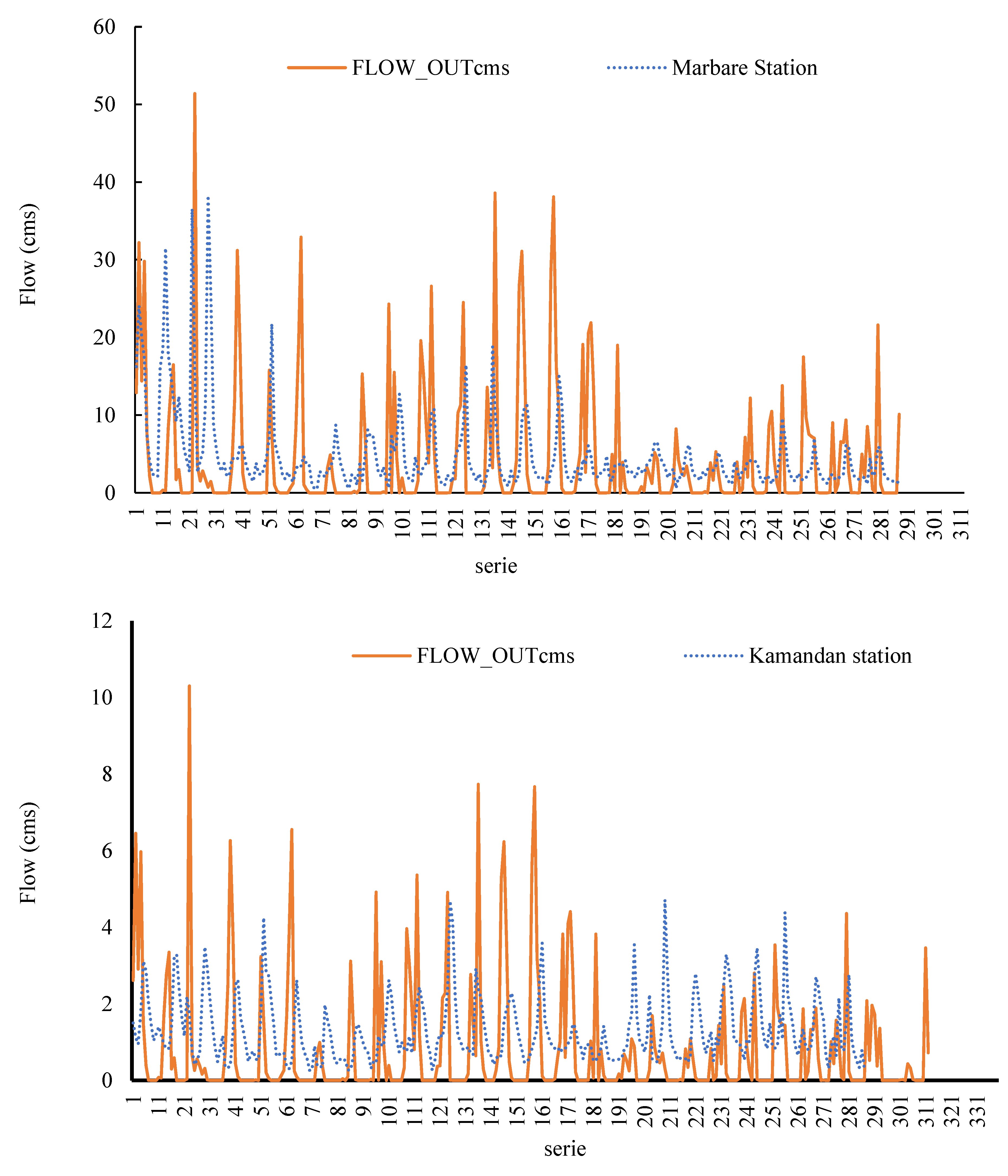

Figure 10.

Comparison of observed and simulated values of flow at (a) calibration, (b) validation phases.

Figure 10.

Comparison of observed and simulated values of flow at (a) calibration, (b) validation phases.

Figure 11.

Graphical depict of snowpack values (a) and its distribution (b) at the outlet station for both Scenarios A and B.

Figure 11.

Graphical depict of snowpack values (a) and its distribution (b) at the outlet station for both Scenarios A and B.

Figure 12.

Graphical depict of snowmelt parameters (a) Snowmelt distribution (b at the outlet station for both Scenarios A and B.

Figure 12.

Graphical depict of snowmelt parameters (a) Snowmelt distribution (b at the outlet station for both Scenarios A and B.

Table 1.

Climatic information of a Aligoudarz synoptic station.

Table 1.

Climatic information of a Aligoudarz synoptic station.

| Station |

Frost (day) |

Sun. (hour) |

Evap. (mm/day) |

Max. rainfall (24 hr) |

Rainfal (mm) |

Avg. humidity (٪) |

Avg. Temp. (°C) |

Climatic division |

| Aligoudarz |

99 |

2749.7 |

2048.2 |

70.4 |

387.3 |

40 |

12.4 |

Semi-humid

Mild summer

Very cold winter |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the hydrometry stations located in studied area.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the hydrometry stations located in studied area.

| Station |

Station’s type |

Establishment |

Altitude(m) |

Latitude |

Longitude |

| Aligoudarz |

Synoptic |

1985 |

1980 |

°33 ’24 |

°49 ’42 |

| Kamandan |

Rain Gauge Hydrometry |

1967 |

2050 |

“14’18 °33 |

°49’25“36 |

| Dareh Takht |

Rain Gauge Hydrometry |

1955 |

1940 |

“14’21 °33 |

°49’22 “23 |

| Marbare |

Hydrometry |

1958 |

1820 |

“52’22 °33 |

°49’24 “6 |

| ChamZaman |

Hydrometry |

1961 |

1870 |

“36’23 °33 |

°49’23 “27 |

| Vazmehdar |

Snow Gauge |

1974 |

1912 |

“35’22 °33 |

°49’22 “47 |

Table 3.

Land use coverage in studied area.

Table 3.

Land use coverage in studied area.

| Land use type |

Abbreviations |

Area (%) |

Area (Km2)

|

| Grassland |

GRAS |

72.5 |

1588.5 |

| Shrubland |

SHRB |

15.7 |

343.8 |

| Irrigated cropland and pasture |

CRIR |

8.2 |

179.5 |

| Cropland/grassland mosaic |

CRGR |

1.3 |

30.1 |

| Cropland/woodland mosaic |

CRWO |

0.1 |

2.9 |

| Baren or sparsely vegetated |

BSVG |

0.1 |

2.9 |

| Savanna |

SAVA |

0.9 |

19.8 |

| Dryland cropland and pasture |

CRDY |

0.7 |

15.5 |

| Residential-medium density |

URMD |

0.2 |

4.8 |

| Mixed forest |

FOMI |

0.04 |

0.9 |

Table 4.

Soil classes in studied area.

Table 4.

Soil classes in studied area.

| Soil texture type |

Abbreviations |

|

Area (%) |

Area (Km2) |

| Loam |

I-Rc-Yk-c-3508 |

|

53.813 |

1178.3 |

| Clay_loam |

Xk5-2-3a-3578 |

|

40.3 |

881.8 |

| Loam |

I-Rc-Xk-c-3122 |

|

3.8 |

82.5 |

| Clay_loam |

Xh33-3a-3289 |

|

2.1 |

46.3 |

Table 5.

Effective parameters and their optimal values in model calibration.

Table 5.

Effective parameters and their optimal values in model calibration.

| Parameter |

Opt. |

Max. Min. |

Var. type |

Description |

| CN2.mgt |

-0.49 |

-0.48 |

-0.5 |

Multiply |

SCS runoff curve number (-) |

| ALPHA_BF.gw |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

Replace |

Base flow alpha factor (1/days) |

| GW_DELAY.gw |

306.1 |

310.14 |

305.68 |

Replace |

Groundwater delay time (days) |

| GWQMN.gw |

0.92 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

Replace |

Threshold depth in shallow aquifer for return flow (mm) |

| GW_REVAP.gw |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

Replace |

Coefficient for groundwater revap (days) |

| CH_K2.rte |

103.56 |

103.64 |

103.49 |

Replace |

Effective hydraulic conductivity in main channel alluvium |

| SOL_AWC(..).sol |

0.88 |

0.89 |

0.88 |

Multiply |

Available water capacity of the soil layer (mmH2O/mm soil) |

| SOL_K(..).sol |

0.26 |

0.26 |

0.26 |

Multiply |

Saturated hydraulic conductivity (mm/hr) |

| REVAPMN.gw |

1.02 |

1.02 |

1.02 |

Replace |

Threshold depth in shallow aquifer for revap/percolation (mm) |

| OV_N.hru |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

Multiply |

Manning’s “n” value for overland flow (-) |

| SLSUBBSN.hru |

0.21 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

Multiply |

Average slope length (m) |

| PLAPS.sub |

-13.34 |

-13.34 |

-13.34 |

Replace |

Precipitation laps rate |

| SURLAG.bsn |

14.75 |

14.75 |

14.75 |

Replace |

Surface runoff lag time |

| TLAPS.sub |

-9.72 |

-9.72 |

-9.72 |

Replace |

Temperature laps rate |

| SFTMP.bsn |

10.47 |

10.47 |

10.46 |

Replace |

Snowfall temperature |

| SMTMP.bsn |

-9.89 |

-9.89 |

-9.89 |

Replace |

Snowmelt base temperature |

| SMFMX.bsn |

4.58 |

4.59 |

4.58 |

Replace |

Maximum melt rate for snow during year |

| SMFMN.bsn |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.87 |

Multiply |

Minimum melt rate for snow during the year |

| SNOEB(..).sub |

310.65 |

310.66 |

310.64 |

Replace |

Initial snow water content in elevation bands |

| SNOCOVMX.bsn |

-35.24 |

-35.23 |

-35.45 |

Replace |

Snow water content that corresponds to 100% snow cover |

| ALPHA_BNK.rte |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

Replace |

Baseflow alpha factor for bank storage (day) |

| SOL_BD(..).sol |

-0.52 |

-0.51 |

-0.52 |

Multiply |

Moist bulk density |