Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Parameter | ZnO Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) | Hyaluronic acid (HA) | Interfacial/phase Behavior |

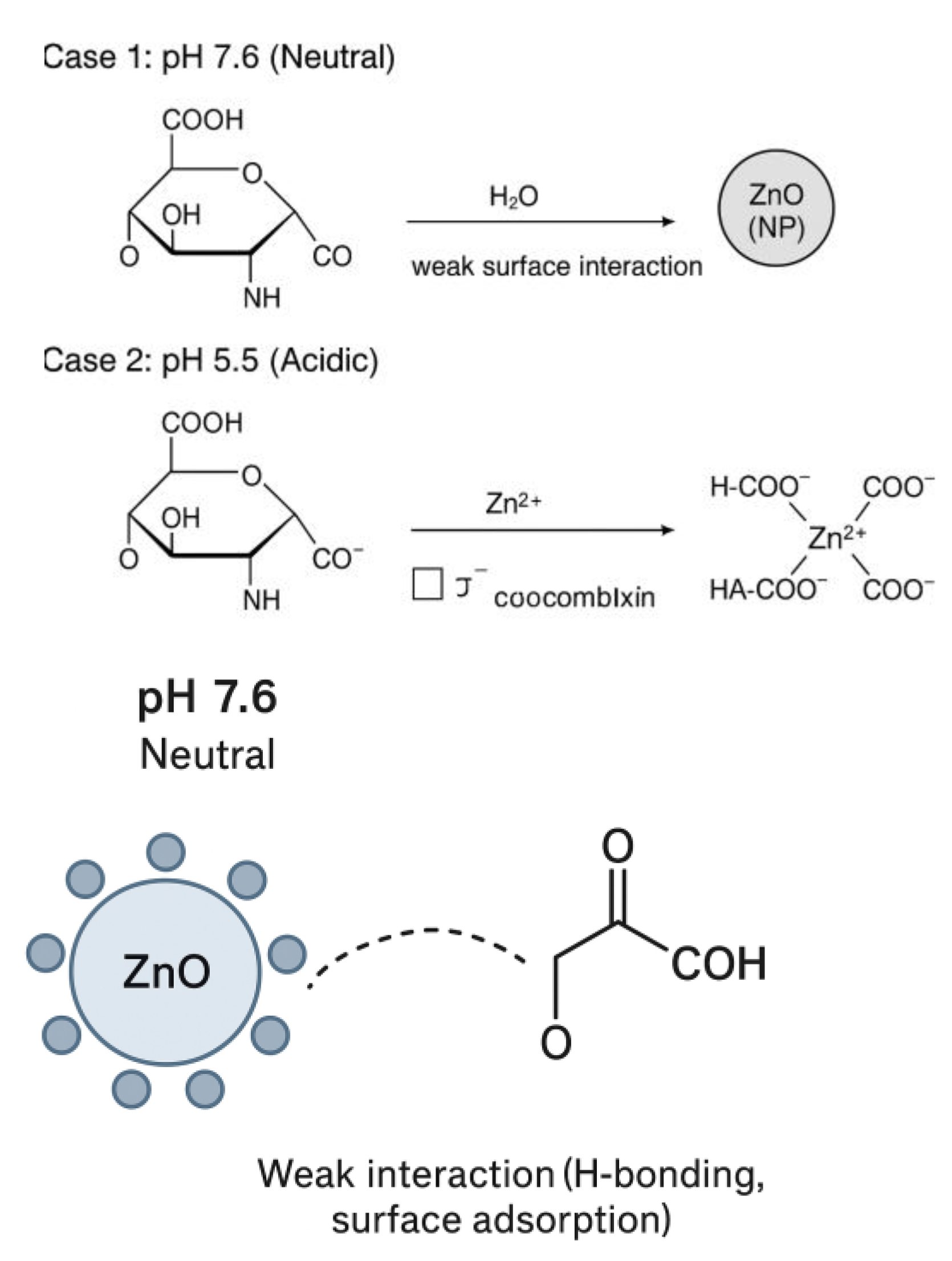

| Surface charge (pH-dependent) | Surface charges varies with pH, becomes positive in acidic and negative in basic media | Naturally negatively charges due to carboxyl and hydroxyl groups | Controlled pH adjustment aligns ZnO with HA, enhancing electrostatic compatibility |

| Dispersion Behavior | Poor dispersion when surface charge is near neutral (aggregation) | Acts as a stabilizing polymeric matrix | Optimal pH yields uniform ZnO dispersion within HA matrix |

| Interparticle Interaction | DVLO forces dominate (van der Waals attraction, electrostatic repulsion) | Adds non DVLO steric and hydration stabilization | Balanced DVLO non DVLO forces suppress aggregation and prevent phase separation |

| Resulting Phase Stability | Instability or phase separation at unadjusted pH | Stable hybrid network when ZnO-HA charge interactions are complementary | pH-modulated charge control leads to improved interfacial compatibility and film uniformity |

2. Methodology and Material

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Composite of HA-ZnO Films

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Atomic Force Microscope (AFM)

2.3.2. Optical Microscopy

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.4. Mechanical Properties (Tensile Strength)

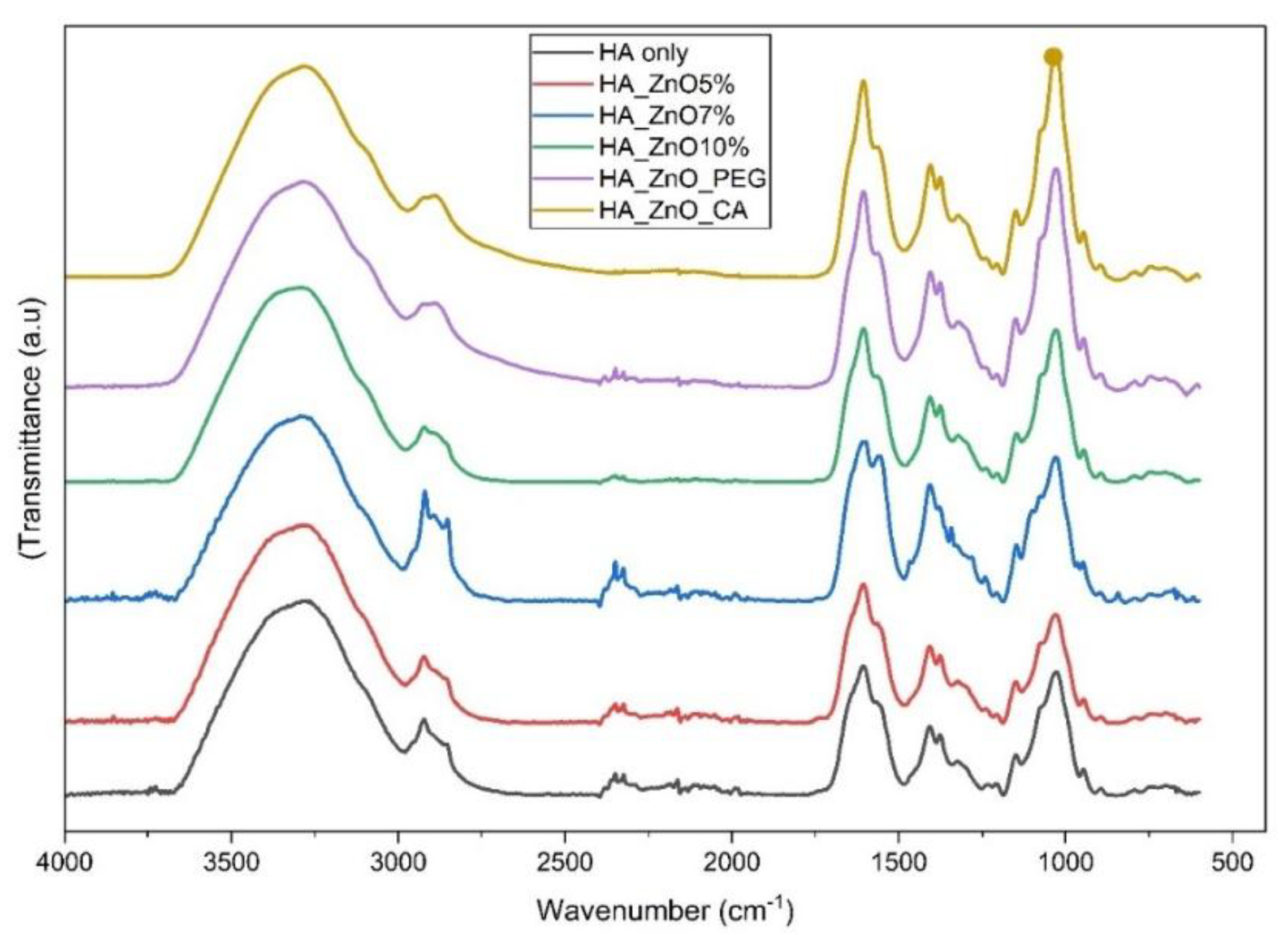

FTIR Analysis

3. Results

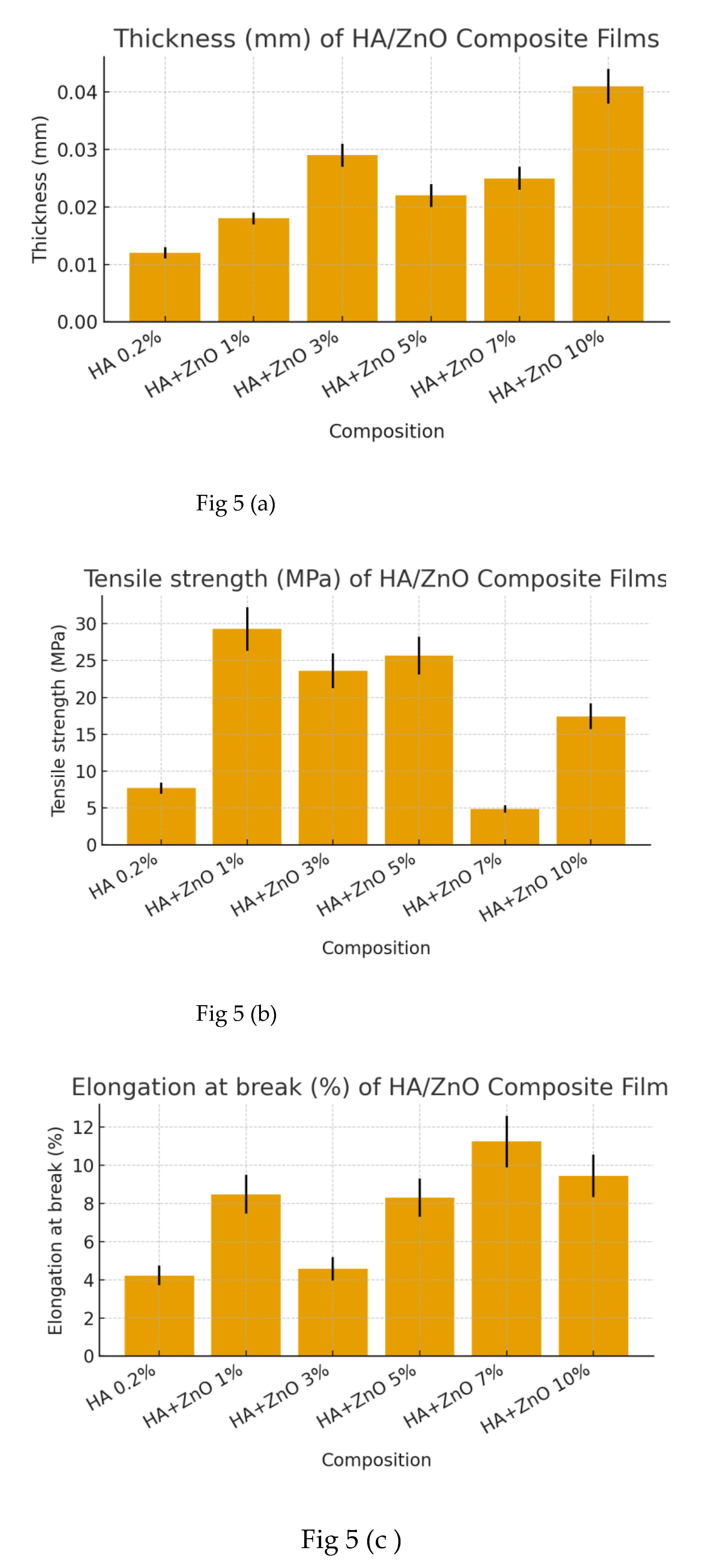

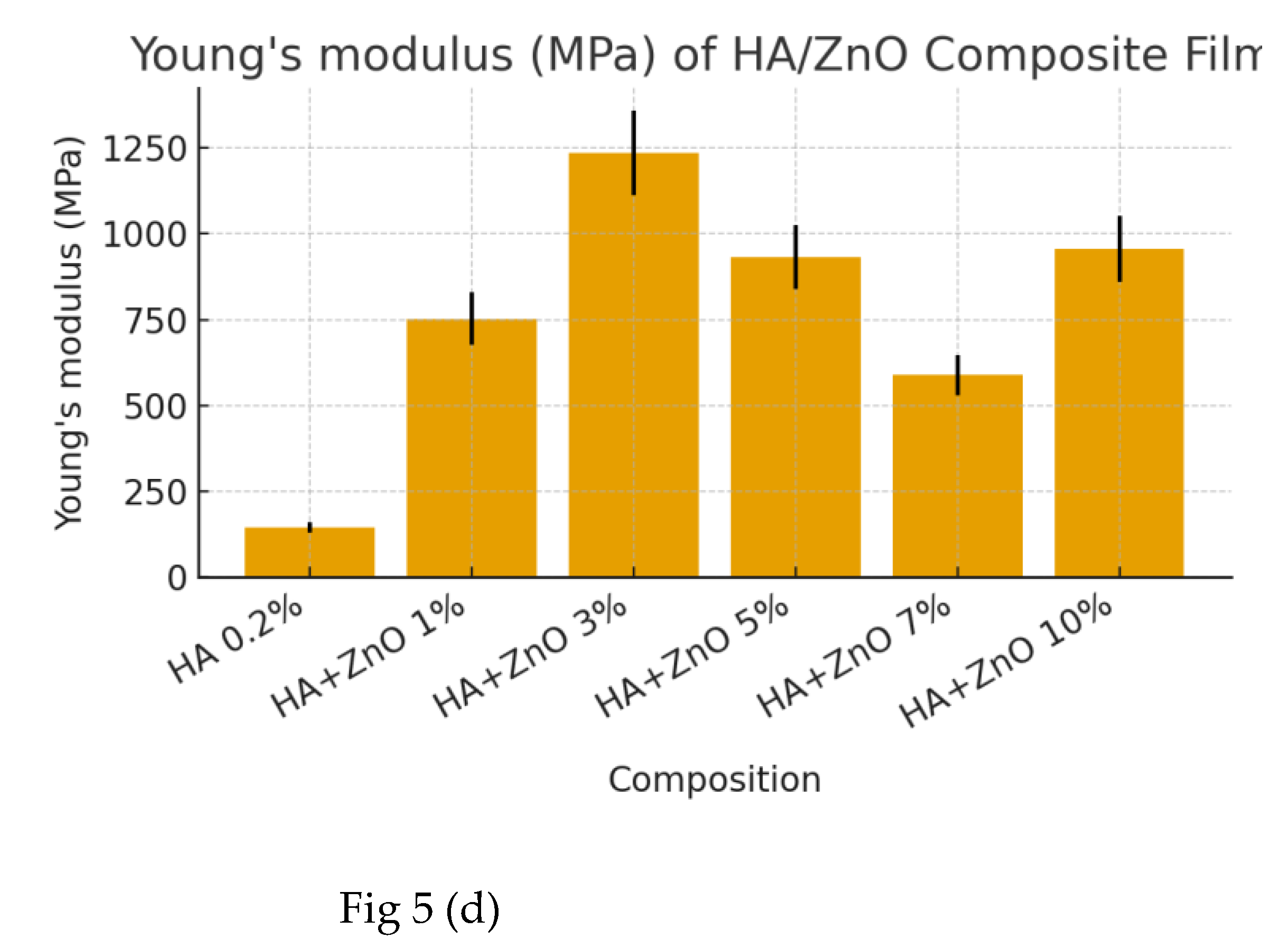

3.1. Optimization of ZnO NPs in HA Composite Film

| Composition | Property | Trial1 | Trial2 | Trial3 | Mean ±SD | ± %Error |

| HA0,2% only | Thickness(mm) | 0,0110 | 0,0120 | 0,0130 | 0,012 ±0,001 | ± 8% |

| Tensile (Mpa) | 6,921 | 7,690 | 8,459 | 7,69 ±0,77 | ± 10% | |

| Elongation (%) | 3,71 | 4,22 | 4,73 | 4,22 ± 0,51 | ± 12 % | |

| Young Modulus (Mpa) | 130,73 | 145,26 | 159,79 | 145,26 ±14,53 | ± 10 % | |

| Composition | Property | Trial1 | Trial2 | Trial3 | Mean ±SD | ± %Error |

| HA+ZnO 1% | Thickness(mm) | 0,0166 | 0,0180 | 0,0194 | 0,018 ±0,001 | ± 8% |

| Tensile (Mpa) | 26,34 | 29,27 | 32,20 | 29,27 ±2,93 | ± 10% | |

| Elongation (%) | 7,46 | 8,47 | 9,48 | 8,47 ± 1,02 | ± 12 % | |

| Young Modulus (Mpa) | 677,70 | 753,00 | 828,30 | 753,00 ±75,30 | ± 10 % | |

| Composition | Property | Trial1 | Trial2 | Trial3 | Mean ±SD | ± %Error |

| HA+ZnO 3% | Thickness(mm) | 0,0267 | 0,0290 | 0,0313 | 0,029 ±0,002 | ± 8% |

| Tensile (Mpa) | 21,26 | 23,62 | 25,98 | 23,62 ±2,36 | ± 10% | |

| Elongation (%) | 4,01 | 4,56 | 5,11 | 4,56 ± 0,61 | ± 12 % | |

| Young Modulus (Mpa) | 1110,42 | 1233,80 | 1357,18 | 1233,80±123,38 | ± 10 % |

| Composition | Property | Trial1 | Trial2 | Trial3 | Mean ±SD | ± %Error |

| HA+ZnO 5% | Thickness(mm) | 0,0202 | 0,0220 | 0,0238 | 0,022 ±0,002 | ± 8% |

| Tensile (Mpa) | 23,09 | 25,66 | 28,23 | 25,66 ±2,57 | ± 10% | |

| Elongation (%) | 7,29 | 8,29 | 9,29 | 8,29 ± 1,00 | ± 12 % | |

| Young Modulus (Mpa) | 838,67 | 931,85 | 1025,04 | 931,85±93,19 | ± 10 % |

| Composition | Property | Trial1 | Trial2 | Trial3 | Mean ±SD | ± %Error |

| HA+ZnO 7% | Thickness(mm) | 0,0230 | 0,0250 | 0,0270 | 0,025 ±0,002 | ± 8% |

| Tensile (Mpa) | 4,41 | 4,90 | 5,39 | 4,90 ±0,49 | ± 10% | |

| Elongation (%) | 9,89 | 11,23 | 12,57 | 11,23 ± 1,34 | ± 12 % | |

| Young Modulus (Mpa) | 529,53 | 588,37 | 647,21 | 588,37±58,84 | ± 10 % | |

| Composition | Property | Trial1 | Trial2 | Trial3 | Mean ±SD | ± %Error |

| HA+ZnO 10% | Thickness(mm) | 0,0377 | 0,0410 | 0,0443 | 0,041 ±0,003 | ± 8% |

| Tensile (Mpa) | 15,17 | 17,44 | 19,18 | 17,44 ±1,74 | ± 10% | |

| Elongation (%) | 8,32 | 9,43 | 10,54 | 9,43 ± 1,11 | ± 12 % | |

| Young Modulus (Mpa) | 859,70 | 955,22 | 1050,74 | 955,22±95,52 | ± 10 % |

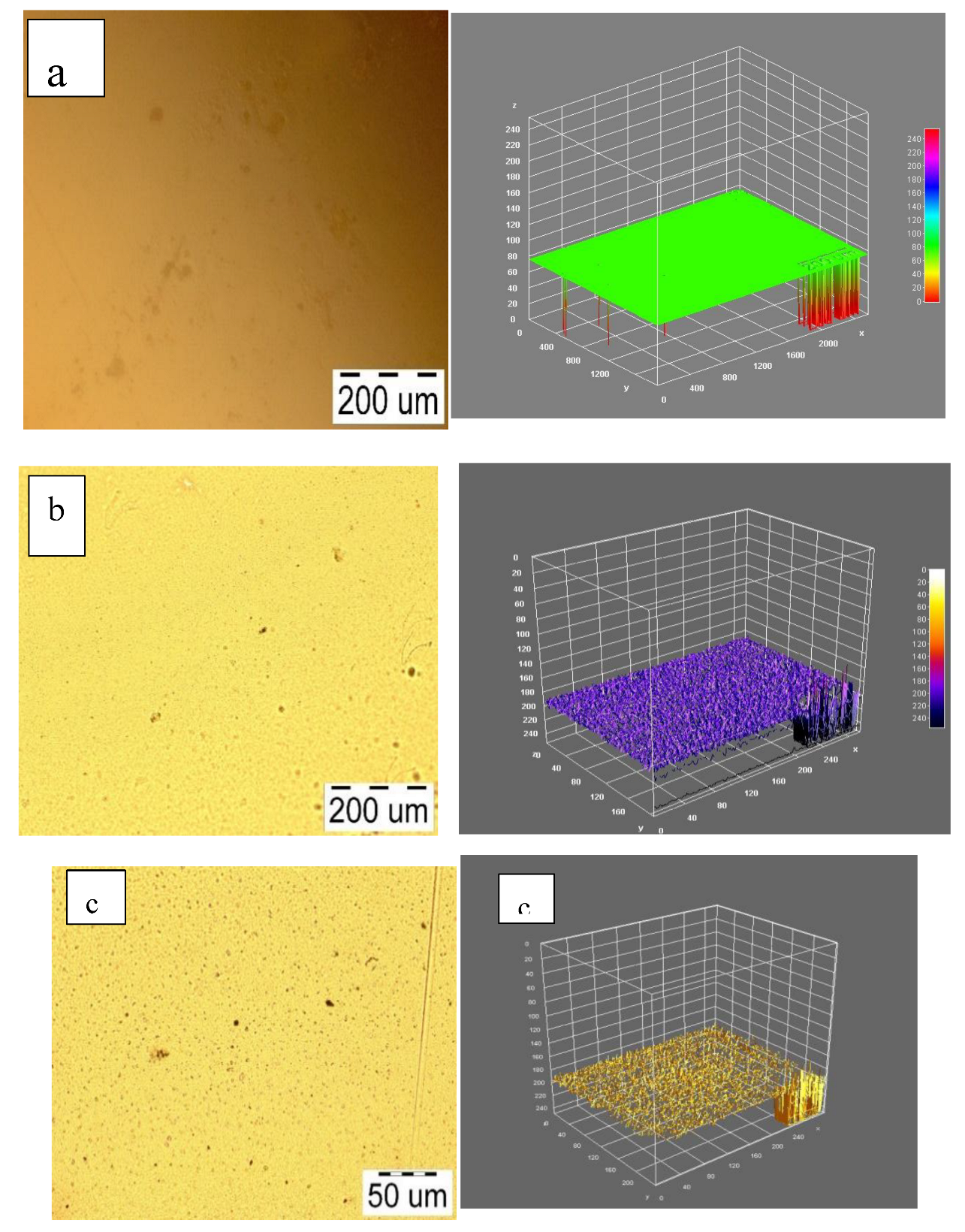

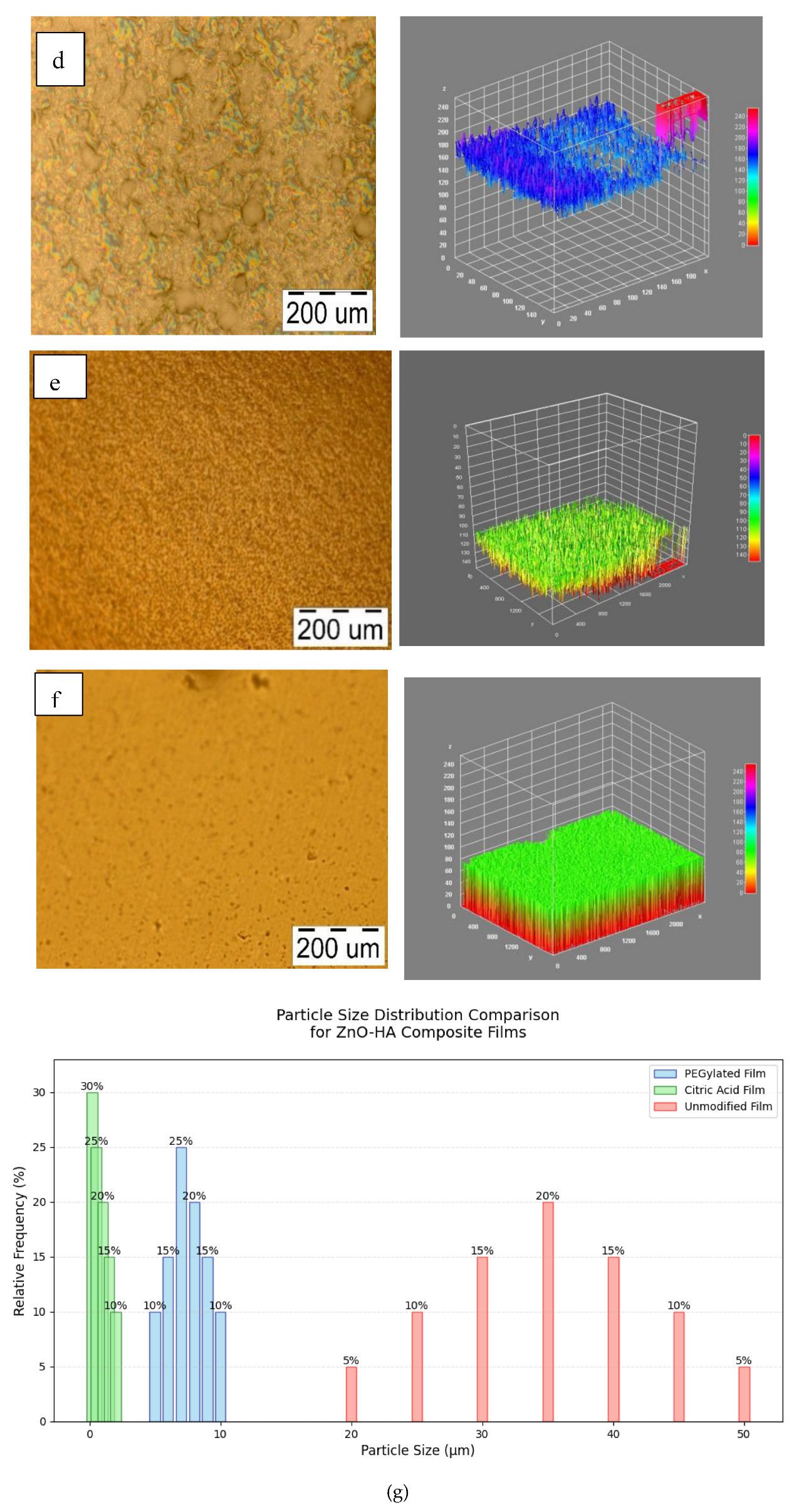

3.2. PEGylation and Chelation on Colloidal Stability and Microstructure

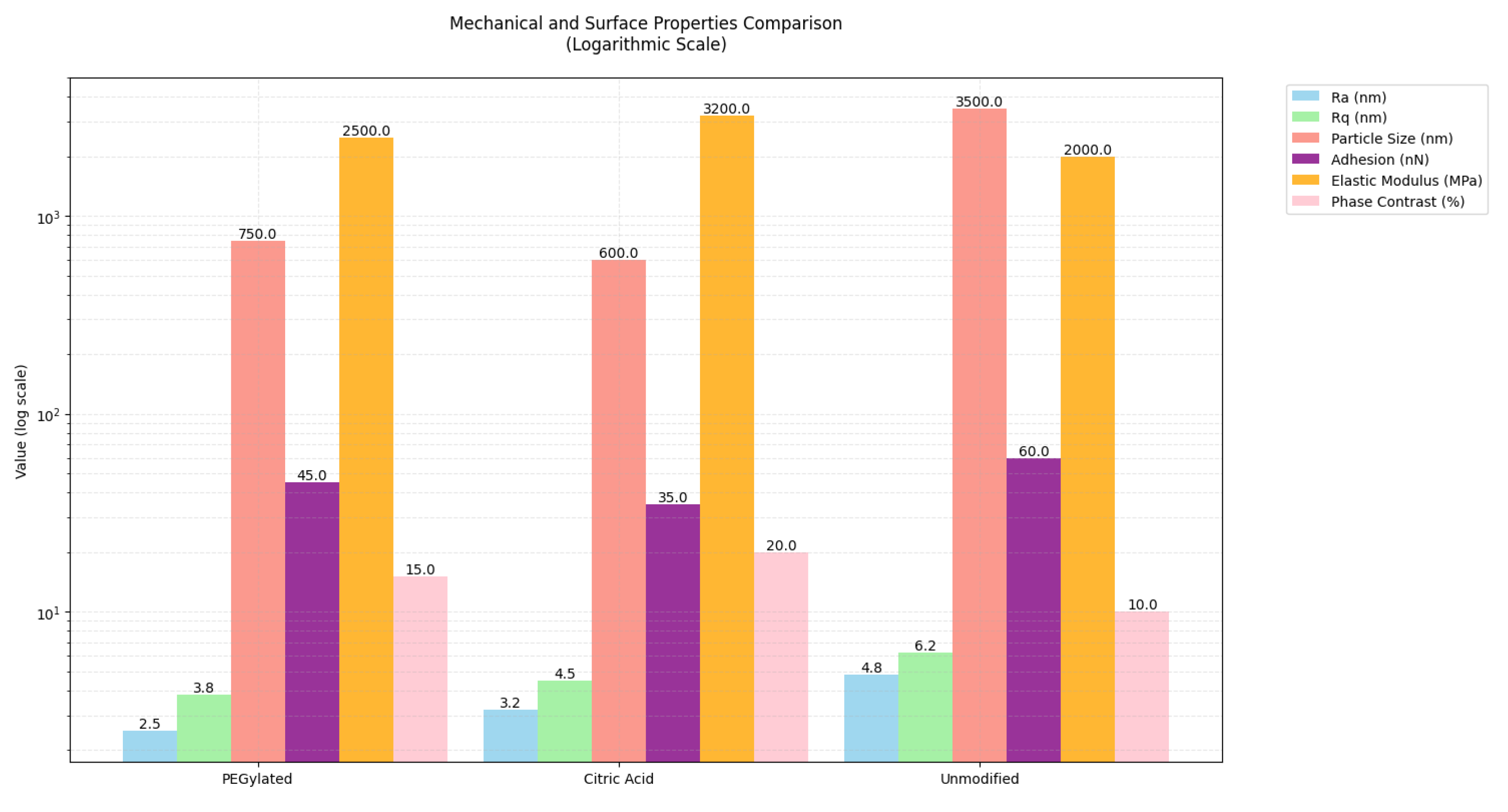

3.3. Microstructure and Mechanical Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. Buckley, E. J. C. Buckley, E. J. Murphy, T. R. Montgomery, and I. Major, “Hyaluronic Acid: A Review of the Drug Delivery Capabilities of This Naturally Occurring Polysaccharide,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 17, p. 3442, Aug. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Yasin, Y. A. Yasin, Y. Ren, J. Li, Y. Sheng, C. Cao, and K. Zhang, “Advances in Hyaluronic Acid for Biomedical Applications,” Front Bioeng Biotechnol, vol. 10, Jul. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. S et al., “Harnessing natural polymers and nanoparticles: Synergistic scaffold design for improved wound healing,” Hybrid Advances, vol. 8, p. 100381, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zare, “Study of nanoparticles aggregation/agglomeration in polymer particulate nanocomposites by mechanical properties,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 84, pp. 20 May; 16. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Nel et al., “Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano–bio interface,” Nat Mater, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 543–557, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Kesler, B. P. D. Kesler, B. P. Ariyawansa, and H. Rathnayake, “Mechanical Properties and Synergistic Interfacial Interactions of ZnO Nanorod-Reinforced Polyamide–Imide Composites,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 6, p. 1522, Mar. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Alipoor, M. R. Alipoor, M. Ayan, M. R. Hamblin, R. Ranjbar, and S. Rashki, “Hyaluronic Acid-Based Nanomaterials as a New Approach to the Treatment and Prevention of Bacterial Infections,” Front Bioeng Biotechnol, vol. 10, Jun. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. N. Bokatyi, N. V. A. N. Bokatyi, N. V. Dubashynskaya, and Y. A. Skorik, “Chemical modification of hyaluronic acid as a strategy for the development of advanced drug delivery systems,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 337, p. 122145, Aug. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Maleki, A. A. Maleki, A. Kjøniksen, and B. Nyström, “Effect of pH on the Behavior of Hyaluronic Acid in Dilute and Semidilute Aqueous Solutions,” Macromol Symp, vol. 274, no. 1, pp. 131–140, Dec. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Fallacara, E. A. Fallacara, E. Baldini, S. Manfredini, and S. Vertuani, “Hyaluronic Acid in the Third Millennium,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 10, no. 7, p. 701, Jun. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. S. Dada, M. V. K. S. Dada, M. V. Uspenskaya, C. N. Elangwe, A. O. Nosova, and R. O. Olekhnovich, “Exploring the influence of mechanical and physical characteristics on transdermal patches: A study on polymeric films composed of hyaluronic acid and zinc oxide nanoparticles,” Proceedings of the Voronezh State University of Engineering Technologies, vol. 86, no. 3, pp. 282–288, Dec. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.-P. Rwei, S.-W. S.-P. Rwei, S.-W. Chen, C.-F. Mao, and H.-W. Fang, “Viscoelasticity and wearability of hyaluronate solutions,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 211–217, Jun. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Sionkowska, M. A. Sionkowska, M. Gadomska, K. Musiał, and J. Piątek, “Hyaluronic Acid as a Component of Natural Polymer Blends for Biomedical Applications: A Review,” Molecules, vol. 25, no. 18, p. 4035, Sep. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Khaleghi, E. M. Khaleghi, E. Ahmadi, M. Khodabandeh Shahraki, F. Aliakbari, and D. Morshedi, “Temperature-dependent formulation of a hydrogel based on Hyaluronic acid-polydimethylsiloxane for biomedical applications,” Heliyon, vol. 6, no. 3, p. e03494, Mar. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Hintze, M. Schnabelrauch, and S. Rother, “Chemical Modification of Hyaluronan and Their Biomedical Applications.,” Front Chem, vol. 10, p. 83 0671, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Petit, Y. J. N. Petit, Y. J. Chang, F. A. Lobianco, T. Hodgkinson, and S. Browne, “Hyaluronic acid as a versatile building block for the development of biofunctional hydrogels: In vitro models and preclinical innovations,” Mater Today Bio, vol. 31, p. 101596, Apr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Khorsand Zak, W. H. A. Khorsand Zak, W. H. Abd. Majid, M. E. Abrishami, and R. Yousefi, “X-ray analysis of ZnO nanoparticles by Williamson–Hall and size–strain plot methods,” Solid State Sci, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 251–256, Jan. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Rohani, N. S. F. R. Rohani, N. S. F. Dzulkharnien, N. H. Harun, and I. A. Ilias, “Green Approaches, Potentials, and Applications of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Surface Coatings and Films,” Bioinorg Chem Appl, vol. 2022, no. 1, Jan. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. N. Zailan, A. S. N. Zailan, A. Bouaissi, N. Mahmed, and M. M. A. B. Abdullah, “Influence of ZnO Nanoparticles on Mechanical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Self-cleaning ZnO-Based Geopolymer Paste,” J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 2007–2016, Jun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. U. H. Khan et al., “Changes in the Aggregation Behaviour of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Influenced by Perfluorooctanoic Acid, Salts, and Humic Acid in Simulated Waters,” Toxics, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 602, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Thipperudrappa, A. S. Thipperudrappa, A. Ullal Kini, and A. Hiremath, “Influence of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the mechanical and thermal responses of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites,” Polym Compos, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 174–181, Jan. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. F. Moghadam and S. Azizian, “Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on the interfacial behavior of anionic surfactant at liquid/liquid interfaces,” Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp, vol. 457, pp. 333–339, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Siddiqi, A. K. S. Siddiqi, A. ur Rahman, Tajuddin, and A. Husen, “Properties of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Activity Against Microbes,” Nanoscale Res Lett, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 141, Dec. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shankar, L.-F. S. Shankar, L.-F. Wang, and J.-W. Rhim, “Incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles improved the mechanical, water vapor barrier, UV-light barrier, and antibacterial properties of PLA-based nanocomposite films,” Materials Science and Engineering: C, vol. 93, pp. 289–298, Dec. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. K. Sharma, S. Shukla, K. K. Sharma, and V. Kumar, “A review on ZnO: Fundamental properties and applications,” Mater Today Proc, vol. 49, pp. 3028– 3035, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Anjum et al., “Recent Advances in Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) for Cancer Diagnosis, Target Drug Delivery, and Treatment.,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 18, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Racca et al., “Zinc Oxide Nanostructures in Biomedicine,” in Smart Nanoparticles for Biomedicine, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 171–187. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Juncan et al., “Advantages of Hyaluronic Acid and Its Combination with Other Bioactive Ingredients in Cosmeceuticals,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 15, p. 4429, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Balogh, J. G. T. Balogh, J. Illés, Z. Székely, E. Forrai, and A. Gere, “Effect of different metal ions on the oxidative damage and antioxidant capacity of hyaluronic acid,” Arch Biochem Biophys, vol. 410, no. 1, pp. 76–82, Feb. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. T. Uthappa, M. U. T. Uthappa, M. Suneetha, K. V Ajeya, and S. M. Ji, “Hyaluronic Acid Modified Metal Nanoparticles and Their Derived Substituents for Cancer Therapy: A Review.,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 6, Jun. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. L. Chia and D. T. Leong, “Reducing ZnO nanoparticles toxicity through silica coating,” Heliyon, vol. 2, no. 10, p. e00177, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Sahoo, S. J. Sahoo, S. Sarkhel, N. Mukherjee, and A. Jaiswal, “Nanomaterial-Based Antimicrobial Coating for Biomedical Implants: New Age Solution for Biofilm-Associated Infections,” ACS Omega, vol. 7, no. 50, pp. 45962–45980, Dec. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Jayaprakash, K. N. Jayaprakash, K. Elumalai, S. Manickam, G. Bakthavatchalam, and P. Tamilselvan, “Carbon nanomaterials: Revolutionizing biomedical applications with promising potential,” Nano Materials Science, Dec. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Cha, S. R. C. Cha, S. R. Shin, N. Annabi, M. R. Dokmeci, and A. Khademhosseini, “Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: Multifunctional Materials for Biomedical Engineering,” ACS Nano, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 2891–2897, Apr. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. S. Dada, M. V. K. S. Dada, M. V. Uspenskaya, C. N. Elangwe, A. O. Nosova, and R. O. Olekhnovich, “Exploring the influence of mechanical and physical characteristics on transdermal patches: A study on polymeric films composed of hyaluronic acid and zinc oxide nanoparticles,” Proceedings of the Voronezh State University of Engineering Technologies, vol. 86, no. 3, pp. 282–288, Dec. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | 0%ZnO(Pure HA) | PEGylated ZnO10% | Chelating agent+ ZnO10% | Unmodified ZnO10% |

| Surface roughness (Ra,nm) | 2,0 ± 0,3 | 2,5 ± 0,3 | 3,2 ± 0,3 | 4,8 ± 0,3 |

| RMS Roughness(Rq,nm) | 3,0 ± 0,4 | 3,8 ± 0,4 | 4,5 ± 0,4 | 6,2 ± 0,4 |

| Particle size (nm) | N/A | 750 ± 12 | 600 ± 12 | 3500 ± 12 |

| Adhesion Force(nN) | 15,0 ± 2,1 | 45,0 ± 2,1 | 35,0 ± 2,1 | 60,0 ± 2,1 |

| Elastic Modulus(Mpa) | 150 ± 15 | 2500 ± 15 | 3200 ± 15 | 2000 ± 15 |

| Phase Contrast δPhase,%) | 8 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 |

| Wavenumber range cm-1 | Functional group | Peak characteristics | Compatibility Evidence | Effect of modification |

| 3500-3550 | O-H stretching | Sharp peaks 0-7%ZnO | Peak broadening at 10%ZnO | Enhanced peak intensity PEG/CA |

| 2850-3000 | C-H stretching | Progressive intensity increases to 7% | Reduced intensity at 10% | Additional absorption bands |

| 17003 | C=O stretching | Max. intensity at 7%ZnO | Peak shift in modified composites | Distinct peak shift in PEG/CA |

| 33001 | N-H stretching | Clear transition at 0-7% | Peak broadening at 10% | Enhanced peak definition |

| 1550-1650 | N-H Bending | Sharp peaks 0-7% | Reduced intensity at 10% | Increased peak intensity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).