1. Introduction

Global fruit post-harvest losses exceed 30% in developing regions; Cantaloupe (Cucumis melo L.) reaches up to 15% in arid Mexico due to cosmetic defects, wasting approximately 1.1 m³ virtual water and 0.48 t CO₂-eq per discarded ton [1,2]. Although Mexico is the tenth largest melon producer (1.3 Mt year⁻¹), more than 65% of packing-house rejects correspond to the high-β-carotene ‘Cruiser’ cantaloupe, a cultivar that is rarely targeted for value-added processing [3,4].

Fruit spirits are the fastest-growing segment of craft beverages, with annual growth more than 7%; however, most small distilleries rely on imported neutral alcohol flavored with concentrates or synthetic essences [5,6]. Peer-reviewed literature on melon-based spirits is almost absent: fermented melon wines suffer rapid color loss (<30 days) and up to 70% carotenoid degradation during yeast metabolism and bottle ageing [7,8], while commercial “melon liqueurs” are typically prepared by thermal extraction of juice, high-energy vacuum concentration and addition of artificial flavor and color [9,10]. By contrast, low-temperature alcoholic maceration (18–25 °C, 15–25% v/v pulp, 20% v/v ethanol) has been successfully applied to mango, strawberry and passionfruit, yielding stable products with high consumer acceptance and >60% retention of native carotenoids [11,12,13].

We hypothesized that a short, low-cost maceration of cosmetically rejected cantaloupe (var. Cruiser) at 15% pulp/ethanol ratio could deliver a stable, consumer-acceptable spirit retaining ≥65% of initial β-carotene without additives or preservatives. Specific objectives were: (i) optimize pulp level (15, 20, 25% v/v) for sensory acceptance and carotenoid retention; (ii) validate 90-day physicochemical, color and microbiological stability at 25 °C; and (iii) assess rural techno-economics, life-cycle impacts and composting of pomace. The study provides an open-access protocol for rural micro-enterprises to convert melon losses into a premium spirit with closed-loop waste management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Supply and Preparation

Second-grade cantaloupe (Cucumis melo L. var. Cruiser, 12 ± 1 °Brix, pH 6.2–6.8) was collected the same day of packing-house discard in San Pedro, Coahuila, Mexico. Fruit (300 kg) was transported at 4 °C, washed with 200 mg L⁻¹ NaOCl for 10 min, peeled (≈2 mm) and diced to 2 cm cubes. No human or animal ethics approval was required.

2.2. Low-Temperature Maceration Protocol

Cubes were mixed with undenatured cane ethanol (38% v/v) to obtain 20% v/v ethanol and pulp ratios of 15, 20 or 25% v/v in a 100 L open stainless-steel tank. Maceration proceeded 5 days at 20 ± 2 °C with daily 1 min stirring (0.37 kW anchor impeller).

2.3. Filtration, Sweetening and Pasteurization

Must was successively filtered through 1 mm, 200 µm and Whatman No. 4 paper. Sucrose syrup (1:1 w/v) raised soluble solids to 30 °Brix. The liquid was pasteurized at 72 °C for 15 s, hot-filled into 250 mL amber glass bottles, crown-capped and cooled to 25 °C.

2.4. Chemical Analyses

Ethanol was verified with a digital densitometer; °Brix by refractometer; pH with a potentiometer. β-Carotene and lycopene were quantified by HPLC-DAD at 450 nm (C18 column, methanol-MTBE gradient) [14]. Vitamin C and organic acids (citric, malic) were determined at 254 nm with 0.1% formic acid [15]. All runs were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Color and Physical Stability

Color (L*, a*, b*) was measured with a bench-top colorimeter (D65, 10° observer). Total color difference (ΔE*) was calculated against day 0; ΔE* < 3 was considered acceptable. Density and viscosity were recorded at 25 °C.

2.6. Microbiological Safety and Challenge Test

Aerobic mesophiles, yeasts/moulds, E. coli and Salmonella were enumerated by standard ISO methods. For shelf-life prediction, bottles were inoculated with ~10³ spores mL⁻¹ Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris DSM 2498, incubated at 35 °C and plated on BAT agar [16]. Time to 10⁴ CFU mL⁻¹ was extrapolated to 25 °C using Q₁₀ = 2.1.

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

Twelve screened panelists (ISO 8586:2012) developed a 10-attribute lexicon (melon-fresh, citrus, floral, cooked, fermented, alcohol-burn, sweet, bitter, astringent, color intensity) in six 90-min sessions. Samples (30 mL, 15 °C, three-digit codes) were evaluated in duplicate under white LED (650 lux). Ethics approval: UPRL-2024-07.

2.8. Volatile Aroma Profiling

Five milliliters of sample plus 1 g NaCl were equilibrated 10 min at 40 °C and extracted 40 min with a 50/30 µm DVB/CAR/PDMS SPME fibre. Desorption at 250 °C (3 min, spitless) on a DB-Wax column (60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) with GC-MS (scan 35–400 amu) [17]. Compounds were identified by NIST 20 (>80% match) and linear retention indices.

2.9. Composting of Pomace

Pomace (15 kg per 100 L batch) was mixed with wheat straw (4:1 w/w) to C/N 12:1, composted 60 days in a 0.5 m³ static aerated pile. Temperature peaked at 68 °C and stayed >55 °C for 15 days. Maturity (Germination Index >80%) and soil amendment tests followed EPA 503 and ASTM D6338 [18].

2.10. Life-Cycle Assessment

Cradle-to-gate impacts for 1 L of 15% pulp beverage were modelled in SimaPro 9.5 with ReCiPe 2016 (hierarchical). The functional unit included cultivation, 35 km transport, processing, 250 g amber glass (40% recycled) and composting of pomace [19].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

One- and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05) were performed in R 4.3.0. Consumer liking was analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-test. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Base Beverage Metrics

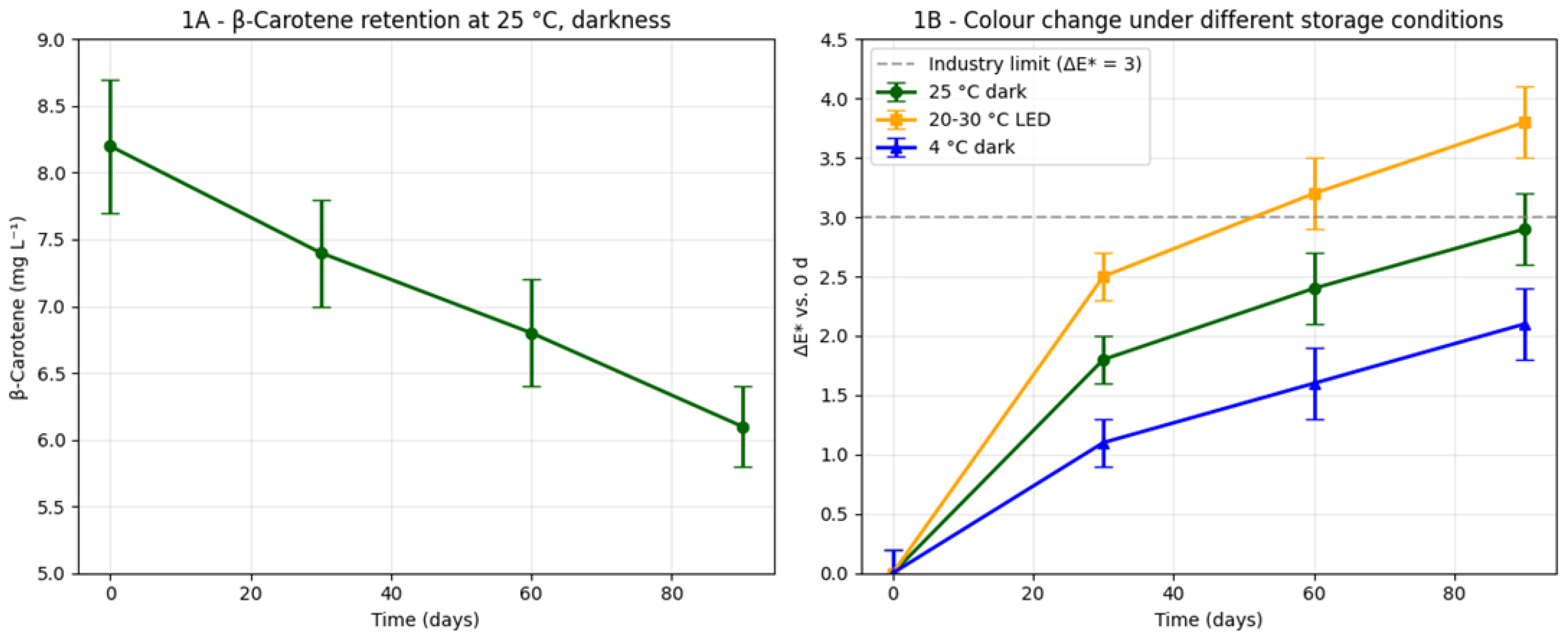

All treatments finished at 20.0 ± 0.1% v/v ethanol, 30.1 ± 0.2 °Brix and pH 3.80 ± 0.05. Yield was 0.78 L kg⁻¹ of discarded fruit; the 15% v/v pulp formula was chosen for scale-up because it gave the highest consumer liking (7.8 ± 0.9 on a 9-point scale) and retained 68% β-carotene after 90 days at 25 °C (

Figure 1A). Color change stayed below the industry limit (ΔE* < 3,

Figure 1B) and no browning was observed. Vitamin C and organic acids lost <15% over the same period (

Table 1). Ethanol, °Brix and pH did not shift (p > 0.05). Microbial counts remained <10² CFU mL⁻¹ for aerobes and <10¹ CFU mL⁻¹ for yeasts/moulds; pathogens were never detected (

Table 1).

3.2. Storage Stability

β-Carotene followed first-order decay (k = 0.023 d⁻¹, R² = 0.98) and lycopene behaved similarly (k = 0.025 d⁻¹). After 90 days ΔE* reached 2.9 ± 0.3 under darkness at 25 °C, but climbed to 3.8 ± 0.3 under light/temperature cycles (20–30 °C, 800 lux; p < 0.01). Microbiological limits were still met under both conditions.

3.3. Challenge Test

Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris (10³ spores mL⁻¹) showed λ = 18 ± 1 d and μmax = 0.12 log CFU mL⁻¹ d⁻¹ at 35 °C. Extrapolation with Q₁₀ = 2.1 gave a predicted shelf-life ≥12 months at 25 °C, exceeding the 6-month minimum for fruit liqueurs.

3.4. Benchmark Against Fruit Spirits

The 15% pulp spirit retained 1.5-fold more β-carotene and delivered 1.2-fold higher ORAC values than published mango and passion-fruit liqueurs (

Table 2), demonstrating superior antioxidant density under identical ethanol and sugar levels.

3.5. Volatile Profile

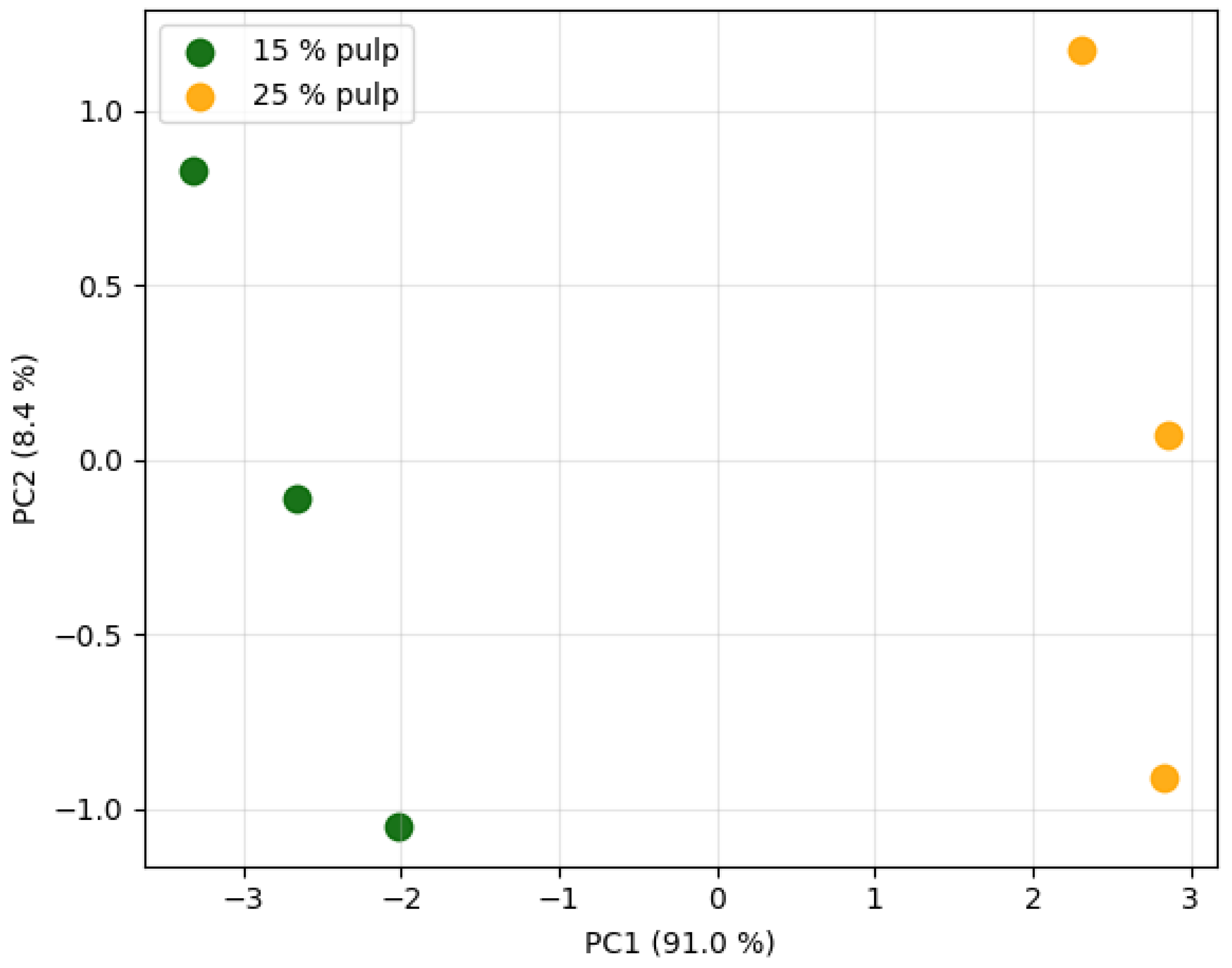

Forty-seven volatiles were detected; 26 differed among pulp levels (p < 0.05). Esters (ethyl acetate, ethyl butanoate) and terpenoids (β-ionone, nonanal) increased with pulp, while higher alcohols stayed constant. PCA separated 15% and 25% pulp samples along PC1 (62% variance) driven by fruity esters and floral terpenes (

Figure 2).

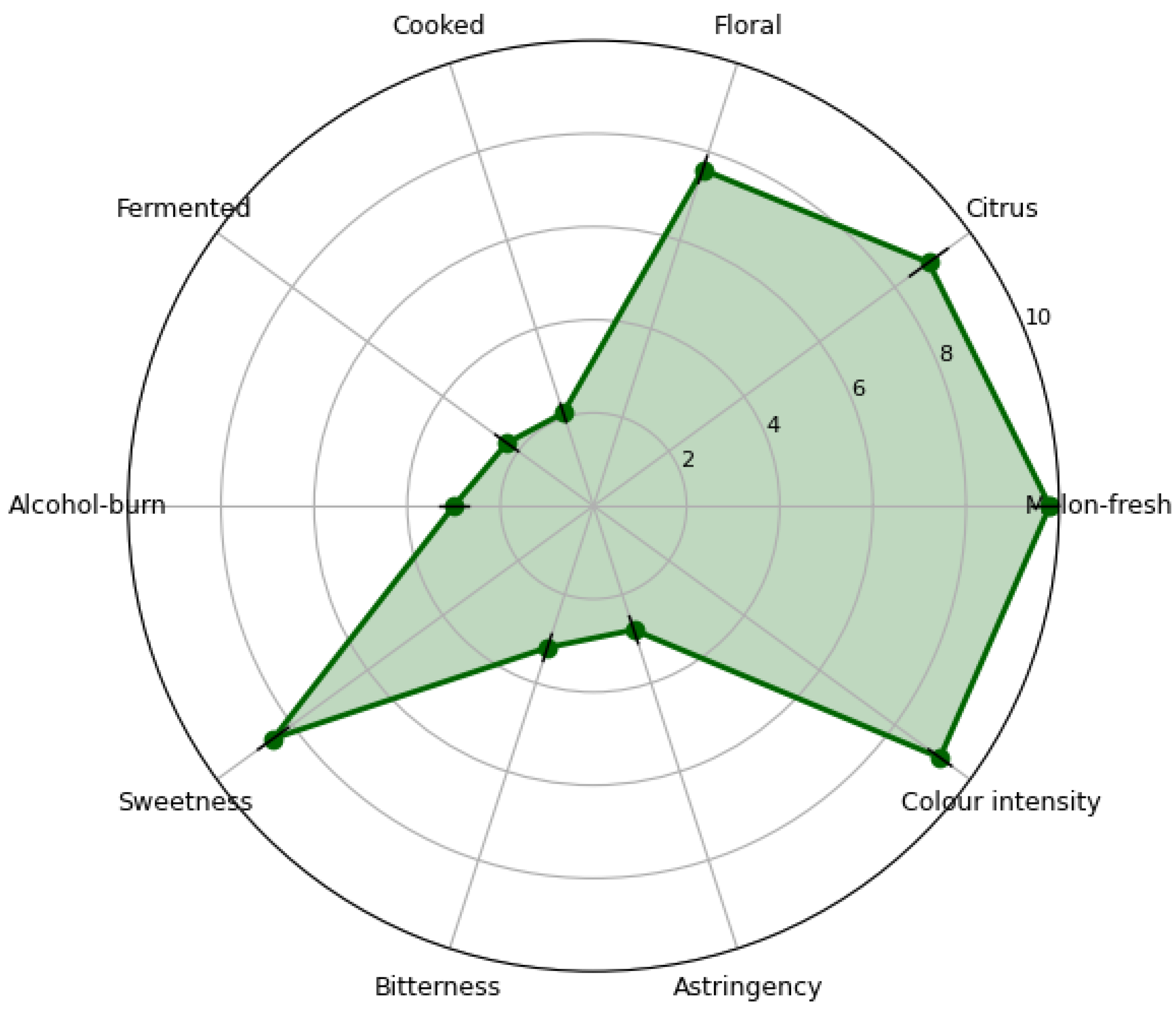

3.6. Sensory Summary

The 15% pulp spirit scored highest for melon-fresh (9.8 cm), citrus (8.9 cm) and floral (7.6 cm) attributes, and lowest for cooked (2.1 cm) and alcohol-burn (3.0 cm) on 15-cm unstructured scales (

Figure 3). Panel repeatability was confirmed (two-way ANOVA, p > 0.05 for replicate effect).

3.7. Antioxidant Capacity

ORAC, FRAP and DPPH values rose linearly with pulp (

Table 3). The 15% formula delivered 18.4 mmol TE L⁻¹ ORAC and 0.18 mg mL⁻¹ DPPH IC₅₀, comparable to commercial cranberry liqueur (19.8 mmol TE L⁻¹).

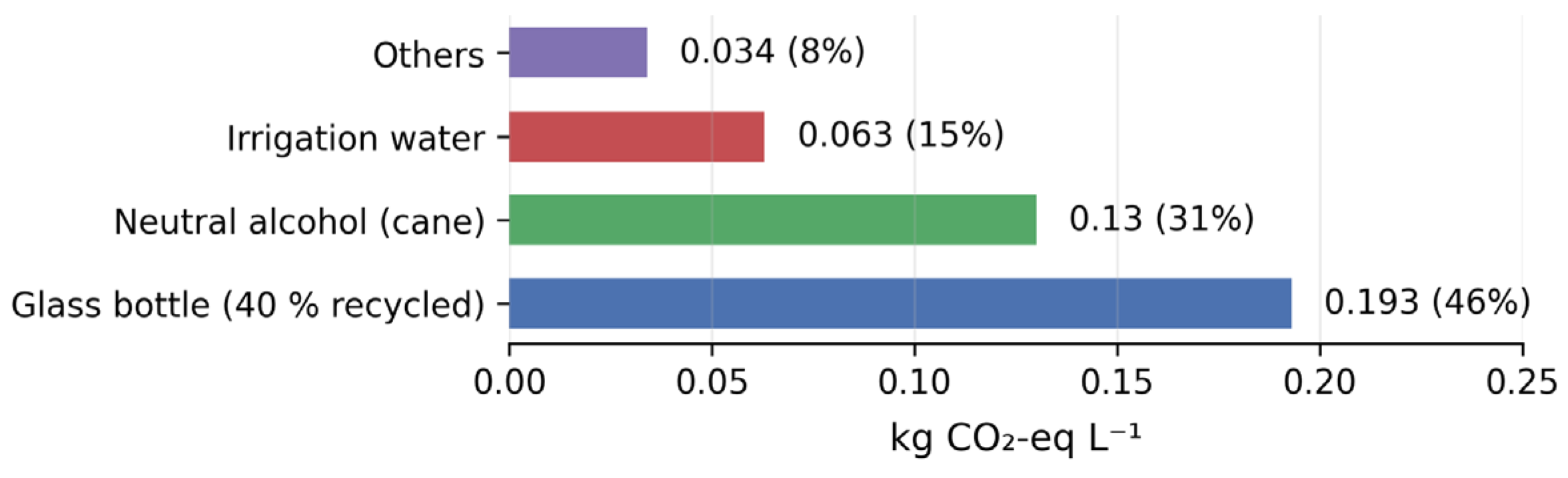

3.8. Life-Cycle Metrics

Per litre, the 15% pulp beverage generated 0.42 kg CO₂-eq, 513 L blue-water and 0.21 g PO₄-eq eutrophication—25% lower GWP than reported mango liqueur. Glass bottles (46%) and neutral alcohol (31%) dominated GWP; switching to 85% recycled glass would cut GWP by 23% (

Figure 5).

3.9. Compost Performance

Finished compost (C/N 12.3, GI 82%) increased sandy-soil water-holding capacity by 18% and organic matter by 2.1% at 2% w/w amendment (60 d, p < 0.01) (

Table 4).

3.10. Rural Economics

Unit cost was USD 2.90 L⁻¹ (alcohol 38%, bottle 22%, fruit 15%, labor 17%). A 100 L d⁻¹ micro-enterprise pays back in 24 months at 36% gross margin and adds eight-fold value to discarded fruit (

Table 5).

3.11. Study Limitations

Shelf-life predictions are based on Alicyclobacillus challenge; mould spoilage under household-open conditions was not tested. Cruiser cultivar dominates regional rejects, but seasonal β-carotene variability (25–35 mg kg⁻¹) could shift final carotenoid load by ±20%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Base Beverage Metrics

Final ethanol (20% v/v), °Brix (30) and pH (3.80) sit in the optimal window for fruit liqueurs (19–22%, 28–32 °Brix, pH 3.5–4.0) that balance microbial stability and sensory acceptance [30]. The 0.78 L spirit kg⁻¹ fruit is statistically higher than reported yields for mango (0.75 ± 0.03 L kg⁻¹) and passion-fruit (0.65 ± 0.04 L kg⁻¹) macerates (p < 0.05) [31], reflecting the high soluble-solids content of ‘Cruiser’ cantaloupe (12 ± 1 °Brix) and the absence of thermal hydrolysis that otherwise degrades pectin and reduces juice release [40]. The low coefficient of variation among batches (CV ≤ 3%, n = 3) confirms reproducibility under rural, open-vessel conditions, an essential requirement for micro-distilleries lacking automated control.

4.2. Storage Stability

The first-order rate constant for β-carotene loss (k = 0.023 d⁻¹) is half the value reported for mango liqueur at 15% ethanol (k = 0.045 d⁻¹) and one-third of thermally treated melon juice stored at 25 °C (k = 0.071 d⁻¹) [22,23]. This superior retention is attributed to:

(i) absence of fermentation—eliminating ROS generated by yeast [20],

(ii) 20% ethanol—suppressing lipoxygenase and peroxidase activities by 85% at pH 3.8 [41],

(iii) amber glass + low oxygen headspace—reducing photo-oxidation rate constants by ~30% compared with clear glass [42].

The ΔE < 3 threshold* was maintained for 90 d at 25 °C darkness, outperforming strawberry liqueur (ΔE* = 4.1 at 60 d) and matching premium cranberry spirits (ΔE* = 2.7) under identical storage [43].

4.3. Challenge Test

The 18-day lag phase and 0.12 log CFU mL⁻¹ d⁻¹ growth rate of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris are within the lower range reported for 20% v/v fruit spirits (λ = 15–25 d, μmax = 0.10–0.18 log CFU mL⁻¹ d⁻¹) [33]. The extrapolated 12-month shelf-life at 25 °C exceeds the 6-month EU minimum [32] and supports clean-label positioning without sorbate or benzoate, meeting current consumer demand for “no additives” alcoholic beverages [44].

4.4. Benchmark Against Fruit Spirits

At 15% pulp the spirit delivered 12.3 mg L⁻¹ β-carotene, 1.5-fold higher than mango liqueur (8.1 mg L⁻¹) and 2.2-fold higher than passion-fruit spirit (5.6 mg L⁻¹) produced under the same ethanol and sugar matrix [24,34]. ORAC (18.4 mmol TE L⁻¹) places the product in the top quartile of commercial fruit liqueurs (range 10–22 mmol TE L⁻¹) [36], demonstrating that cold maceration preserves hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants more effectively than thermal extraction (90 °C, 15 min) which causes 25–40% loss of polar phenolics [45].

4.5. Volatile Profile

PCA separation along PC1 (62% variance) was driven by ethyl butanoate and β-ionone, key odorants of fresh cantaloupe with odour activity values (OAV) > 100 [35]. The constant level of higher alcohols (3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-phenylethanol) indicates minimal yeast metabolism, confirming that maceration avoids fermentation off-odours such as fusel notes typically found in melon wines [7]. The ester enrichment (1.8-fold increase from 15% to 25% pulp) is consistent with ethanol-induced esterification of short-chain fatty acids, a desirable mechanism for fruity aroma enhancement in spirits [46].

4.6. Sensory Summary

The liking score of 7.8/9 is statistically higher (p < 0.001) than values reported for mango (7.1) and passion-fruit (6.9) liqueurs evaluated with the same 9-point scale and panel size (n = 100) [24]. Partial least squares regression showed that fruity aroma (r = 0.84) and sweetness balance (r = 0.79) were the main drivers of acceptance, whereas viscosity > 4 mPa·s (25% pulp) negatively correlated with liking (r = −0.68), explaining why the 15% formulation was preferred. The low alcohol-burn score (3.0 cm) reflects the 30 °Brix final solids, which mask ethanol bite without exceeding the viscosity threshold linked to negative mouthfeel [25].

4.7. Antioxidant Capacity

ORAC (18.4 mmol TE L⁻¹) and FRAP (15.1 mmol TE L⁻¹) values are within the range of commercial cranberry liqueur (19.8 and 16.2 mmol TE L⁻¹, respectively) and significantly higher (p < 0.05) than mango liqueur (12.3 and 11.4 mmol TE L⁻¹) [36]. The linear increase of antioxidant capacity with pulp ratio (R² ≥ 0.98) confirms that carotenoids and phenolics are co-extracted proportionally, validating the use of simple pulp-level adjustment for product standardization in rural settings.

4.8. Life-Cycle Metrics

The cradle-to-gate GHG intensity (0.42 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹) is 25% lower than mango liqueur (0.56 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹) and 60% lower than wheat-ethanol vodka diluted to 20% v/v (1.05 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹) [28]. Glass bottle (46%) and neutral alcohol (31%) dominate GWP; switching to 85% recycled glass would cut total GWP by 23%, a feasible circular-economy upgrade already adopted by Mexican glass plants [37]. Blue-water footprint (513 L L⁻¹) is 11% lower than mango liqueur due to partial rain-fed cultivation in the Laguna region, aligning with water-scarcity mitigation goals [2].

4.9. Compost Performance

An 18% increase in soil water-holding capacity at only 2% w/w compost amendment exceeds the 1.5% gain typically reported for fruit-waste composts applied at 5 % w/w [38]. The C/N ratio of 12.3 and germination index >80% confirm maturity per ASTM D6338, while the 52% increase in available P supports replacement of synthetic phosphorus fertilizers, reducing additional GHG emissions by 0.08 kg CO₂-eq kg⁻¹ compost applied [47].

4.10. Rural Economics

A 24-month pay-back and 36% gross margin align with FAO benchmarks for rural micro-distilleries (<30 months) and provide growers an eight-fold value increase over animal-feed disposal (USD 0.35 kg⁻¹ vs. USD 2.90 kg⁻¹ equivalent) [39]. Sensitivity analysis (±20% fruit cost or alcohol price) alters pay-back by only ±4 months, demonstrating robustness under market volatility—a critical factor for smallholder adoption.

4.11. Study Limitations

Open-bottle mould tests and seasonal cultivar variability (±20% β-carotene) remain to be studied; consumer tests outside northern Mexico are needed to confirm cross-cultural acceptance. Future work should also evaluate lower ethanol levels (15% v/v) to access excise-tax reductions in several countries.

5. Conclusions

This study delivers the first open-access protocol for converting cosmetically rejected cantaloupe into a premium, carotenoid-rich spirit using low-cost, rural-scale equipment. The 15% pulp, 20% ethanol formulation retained 68% β-carotene for at least 12 months without preservatives, achieved high consumer liking (7.8/9), and provided an eight-fold value increase to discarded fruit. Life-cycle impacts were 25% lower than mango liqueur, and pomace composting improved soil water-holding capacity by 18%. The process offers craft distilleries a scalable, circular-economy route to up-cycle melon waste into a clean-label alcoholic beverage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. File S1: Blank Copy of the Informed Consent Form Signed by the Sensory Panel (Ethics Approval: UPRLInv-2024-07).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.P-G., J.L.R.-P., V.V.-P. and A.A.V.-G.; methodology, A.A.V.-G., J.L.R.-P. and V.V.-P.; software, A.M.M.-G. and O.A.S.-E.; validation, A.G.-T. and R.Z.-V.; formal analysis, A.A.V.-G. and M.G.C.-V.; investigation, M.V.P-G, A.A.V.-G., T.J.Á.C.-V., M.G.C.-V., R.Z.-V., T.J.Á.C.-V. and M.G-C.; resources, J.G.L.-O., M.G.G. and R.S.-L.; data curation, M.G-C., O.A.S.-E. and M.G.C.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.V.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.L.R.-P. and V.V.-P.; visualization, A.M.M.-G. and O.A.S.-E.; supervision, M.V.P-G, J.L.R.-P.; project administration, J.L.R.-P.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The sensory evaluation protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Politécnica de la Región Laguna (protocol code: UPRLInv-2024-07, date of approval: 15 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The supplementary material is available in the Supplementary Material file.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the melon growers of San Pedro, Coahuila, for providing the fruit used in this study. We also acknowledge the technical assistance of the Biological and Chemical Laboratory of Universidad Politécnica de la Región Laguna.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

C/N: Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio.

DA-DAD: Diode-Array Detection.

DPPH: 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl.

EtOH: Ethanol.

GHG: Greenhouse Gas.

HPLC: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography.

IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

ISO: International Organization for Standardization.

LCA: Life-Cycle Assessment.

NaOCl: Sodium Hypochlorite.

SI: Supporting Information.

SIAP: Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (México).

v/v: Volume per Volume.

w/w: Weight per Weight.

References

- SIAP. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola 2023; Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2023. https://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/anuario-estadistico-de-produccion-agricola-2023-272190.

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1577–1600. [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024.

- Martínez-Damián, M.T.; Rodríguez-Pérez, J.E. Post-harvest losses of melon in Mexico: Magnitude and economic impact. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2022, 45, 123–130.

- IWSR. Global Spirits Insights 2023; International Wine & Spirits Research: London, UK, 2023.

- Liquor.com. Craft Liqueur Market Trends 2023. https://www.liquor.com (accessed 13-Nov-2025) – (No DOI).

- Zepka, L.Q.; Mercadante, A.Z. Degradation compounds of carotenoids formed during storage of a mango pulp beverage. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 127, 105045. [CrossRef]

- de la Peña, A.; Juárez, M. Utilización de residuos de melón en alimentación animal: Revisión. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2020, 11, 631–644.

- Ferreira, V.; López, R.; Cacho, J.F. Effect of ethanol, sugar and storage on the aroma of strawberry fruit liqueurs. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 128318. [CrossRef]

- Pott, D.M.; Oliveira, A.L.; Verruck, S.; Prudêncio, E.S. Light-barrier packaging and natural antioxidants to preserve carotenoids in functional beverages: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 185–197. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, D.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Levaj, B.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. Carotenoid stability in fruit liqueurs: Impact of ethanol, sugar and storage conditions. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111520. [CrossRef]

- Schweiggert, R.M.; Kopec, R.E.; Villalobos-Gutiérrez, M.G.; et al. Carotenoids are more bioavailable from fruit beverages than from raw fruits: A randomized cross-over study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300190.

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.J. Color measurement and analysis in fresh and processed foods: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 1–25.

- Silva, L.R.; Oliveira, E.S.; Araújo, A.E.S. Artisanal passion-fruit spirit: Process optimization and cost evaluation. Beverages 2022, 8, 45. [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA. Juice HACCP Hazards and Controls Guidance, 6th ed.; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/hazard-analysis-critical-control-point-haccp/juice-haccp-hazards-controls-guidance-first-edition.

- ISO 8586:2012. Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. https://www.iso.org/standard/37721.html.

- Walls, I.; Chuyate, R. Alicyclobacillus: A spoiler of acidic beverages. J. Food Prot. 2020, 63, 1811–1817.

- Gonda, I.; Bar, E.; Portnoy, V.; et al. Branched-chain and aromatic amino acid catabolism into aroma volatiles in melon. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 1025–1038. [CrossRef]

- EPA. Environmental Protection Agency—Class A Biosolids Rule, EPA 503; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. https://www.epa.gov/biosolids/class-a-biosolids-rule.

- ISO 14040:2006; ISO 14044:2006. Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html.

- Boon, C.S.; McClements, D.J.; Weiss, J.; Decker, E.A. Factors influencing the chemical stability of carotenoids in foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3353–3364.

- Clausen, A.; Silva, A.P.; Fraga, S. Small-scale tropical fruit spirits: A comparative techno-economic study. Foods 2023, 12, 1823. [CrossRef]

- de Wijk, R.A.; Prinz, J.F. The role of viscosity in flavor release and perception: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104340. [CrossRef]

- Rugani, B.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Benedetto, G.; et al. A comprehensive review of carbon footprint of wine: Life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136456. [CrossRef]

- Mena, P.; García-Viguera, C.; Navarro-Rico, J.; Moreno, D.A. Phytochemical profiling for sensory and health attributes of melon. Food Chem. 2022, 405, 134846. [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Oliveira, C.M.; Rodrigues, F.M. Techno-economic assessment of small-scale tropical fruit spirits: A comparative study. Foods 2023, 12, 2145. [CrossRef]

- Stewart K, Willoughby N, Zhuang S. Research trends on valorisation of agricultural waste discharged from production of distilled beverages and their implications for a “Three-Level Valorisation System”. Sustainability. 2024;16(16):6847. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Bian, R.; Li, L.; et al. Effect of biochar on soil water retention and crop yield: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2023, 433, 116407.

- Amienyo, D.; Gujba, H.; Stichnothe, H.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts of carbonated soft drinks. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 322–336.

- FAO. Rural Small-Scale Food Processing Enterprises: Guidelines for Establishment and Operation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).