Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. S. aureus Clinical Isolate Identification and Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiling

2.2. Culture Conditions and Preparation of Bacterial Suspension

2.3. Determination of Bacterial Growth Curves Using Optical Density (OD) Readings

2.4. Reduction of Resazurin Fluorometric Kinetic Assay

2.5. Visualization of Biofilms by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

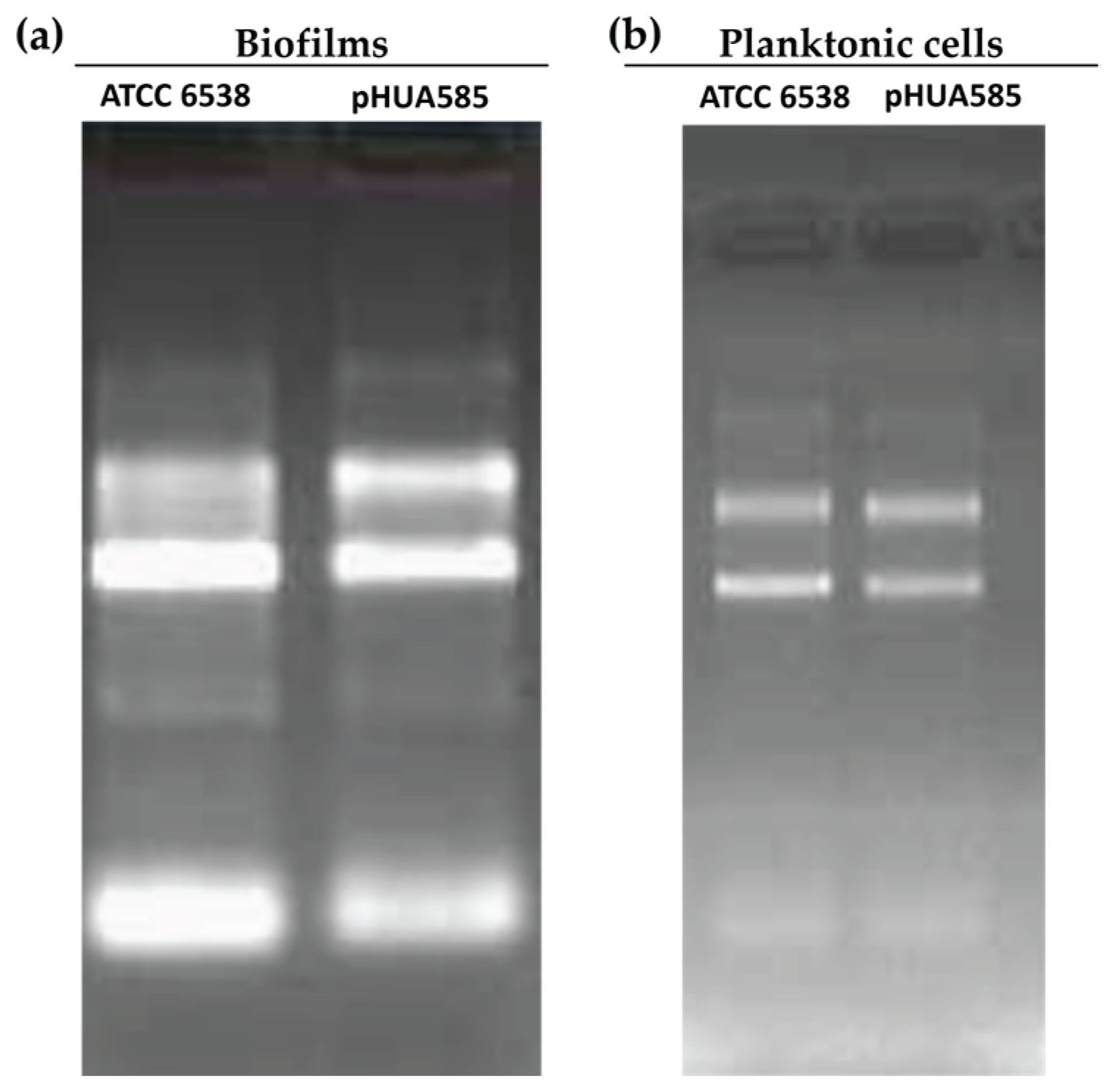

2.6. RNA Extraction Optimization of Planktonic Bacteria and Biofilms

2.7. Removal of Contaminating Genomic DNA

2.8. cDNA Synthesis

2.9. RT-qPCR Calibration Curve

3. Results

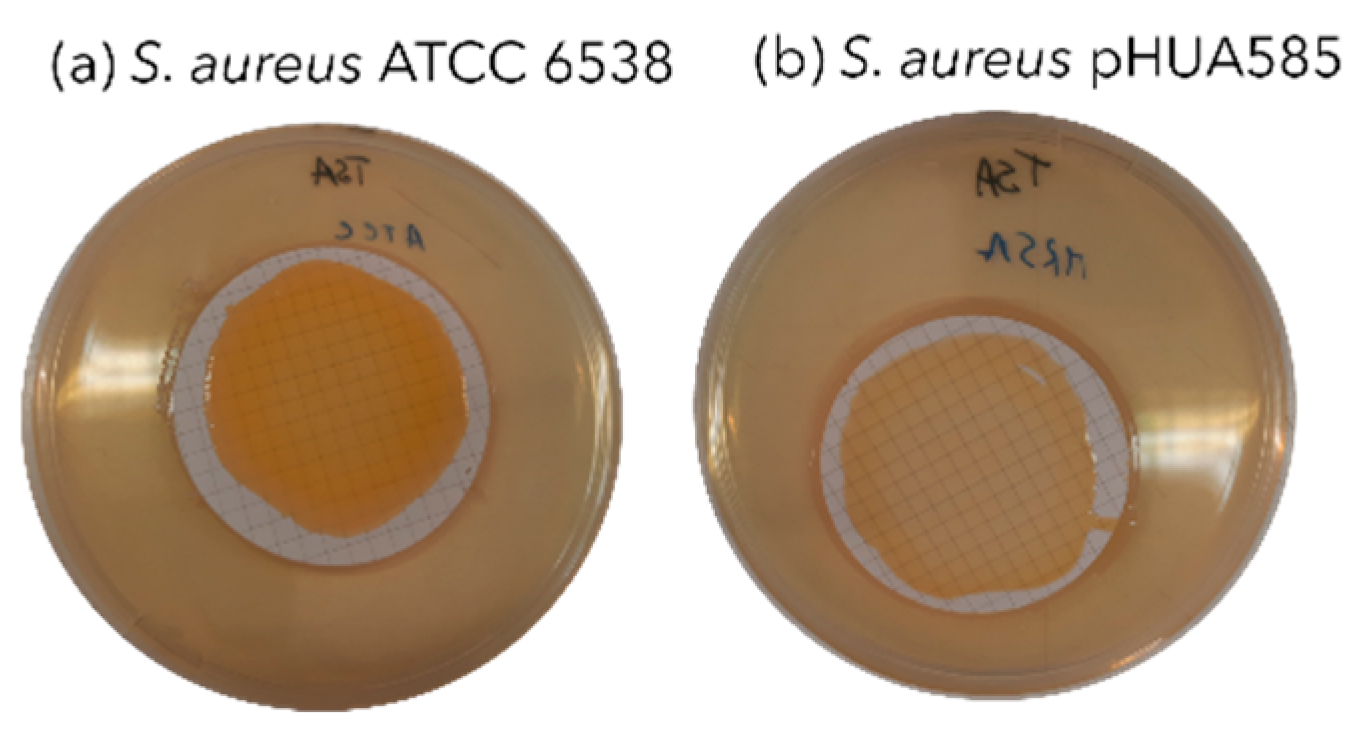

3.1. Clinical Isolate Identification and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

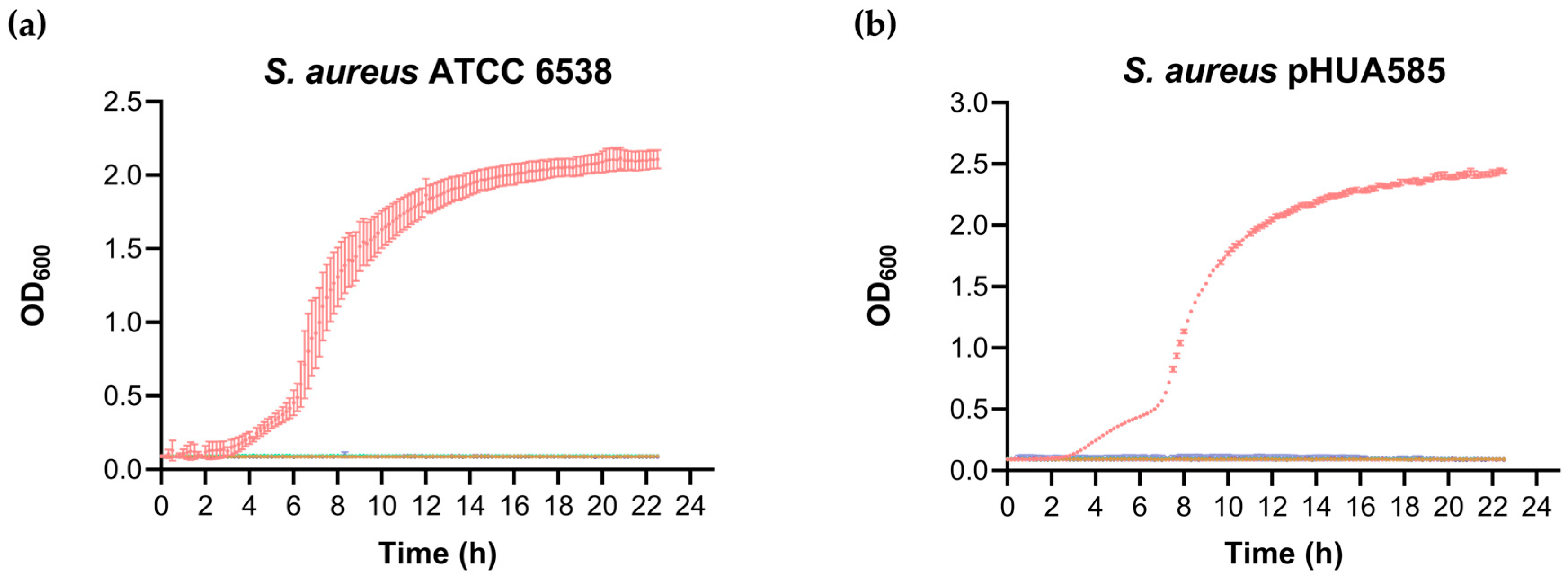

3.2. Effect of Vancomycin on the Growth Curves of Planktonic Cells

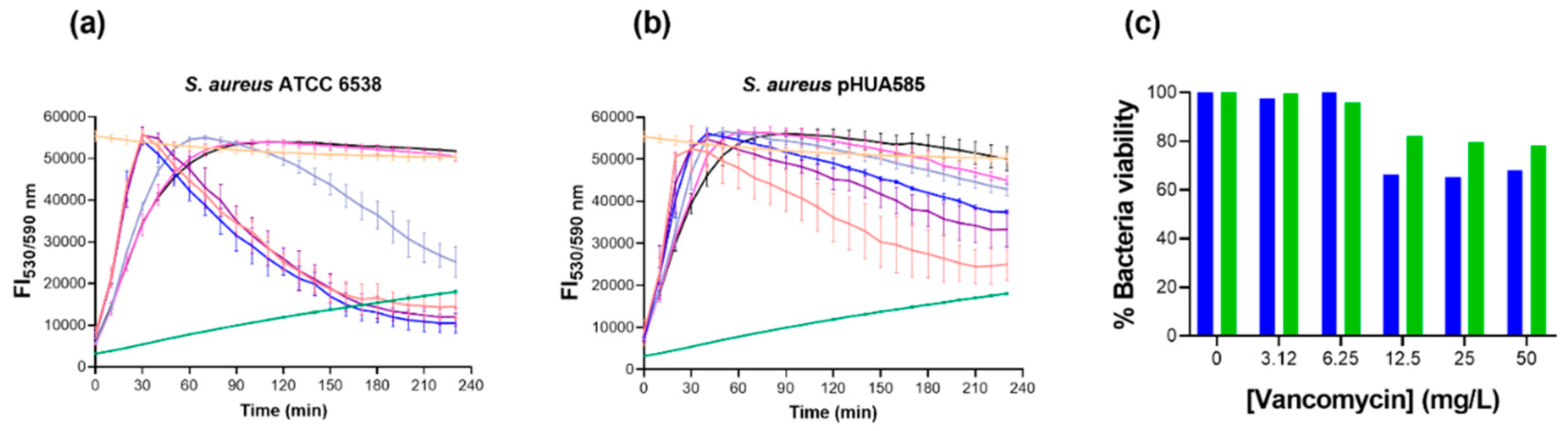

3.4. Effect of Vancomycin in S. aureus Biofilms Using Reduction of Resazurin Fluorometric Kinetic Assay

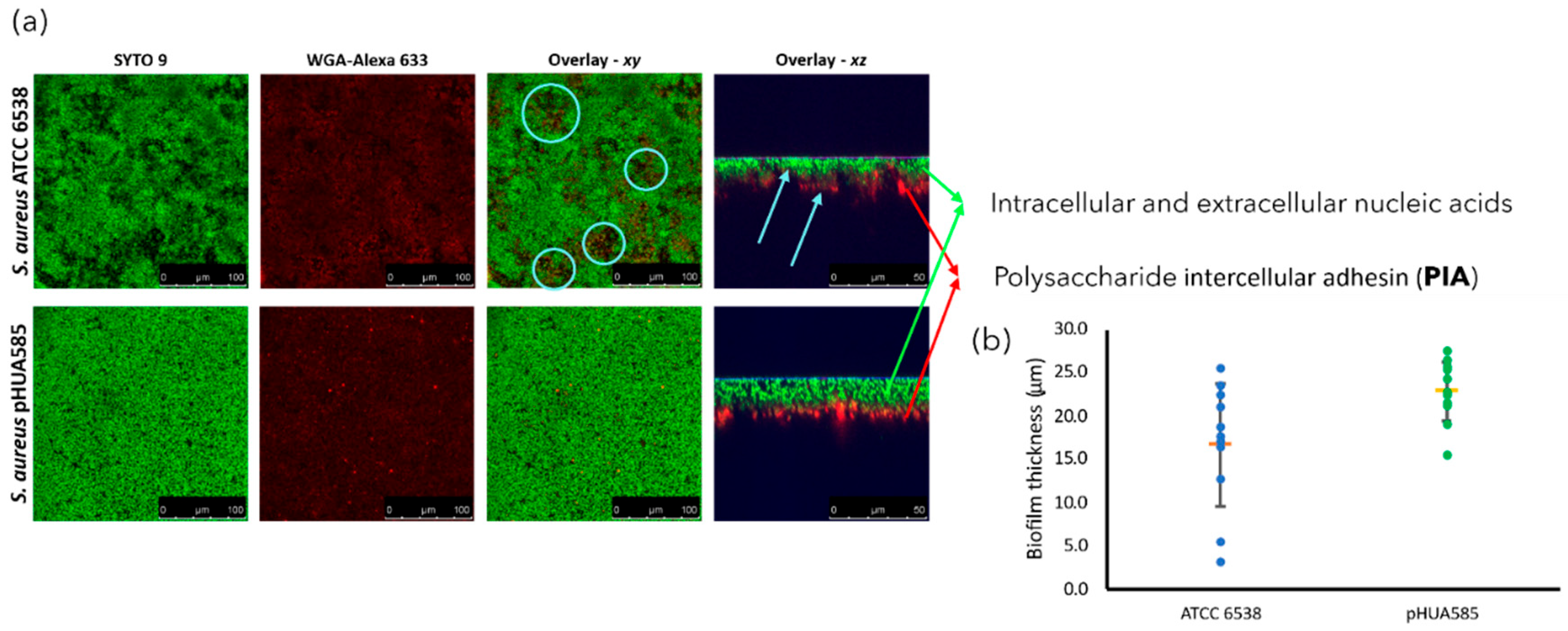

3.3. Visualization of the Biofilms Morphology by CLSM

3.4. RT-qPCR to Confirm icaA Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | antimicrobial resistance |

| BHI | brain heart infusion |

| CLSM | confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EPS | extracellular polymeric substances |

| MALDI-TOF | matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight |

| MRSA | methicillin-resistant |

| MS-CHCA | mass spectrometry α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid |

| MSSA | methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus |

| OD | optical density |

| PIA | polysaccharide intercellular adhesin |

| RPKM | number of reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads |

| sRNAs | small non-coding RNAs |

| TSB | tryptic soy broth |

References

- Wu, H.; Moser, C.; Wang, H.-Z.; Høiby, N.; Song, Z.-J. Strategies for Combating Bacterial Biofilm Infections. Int J Oral Sci 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Mohammad, Z.; Ahmad, J. The Diabetic Foot Infections: Biofilms and Antimicrobial Resistance. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2013, 7, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.; Kaplan, H.B.; Kolter, R. Biofilm Formation as Microbial Development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, N.K.; Mazaitis, M.J.; Costerton, J.W.; Leid, J.G.; Powers, M.E.; Shirtliff, M.E. Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms: Properties, Regulation, and Roles in Human Disease. Virulence 2011, 2, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Wozniak, D.J.; Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Prevention and Treatment of Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2015, 13, 1499–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Stoodley, L.; Stoodley, P.; Kathju, S.; Høiby, N.; Moser, C.; William Costerton, J.; Moter, A.; Bjarnsholt, T. Towards Diagnostic Guidelines for Biofilm-Associated Infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012, 65, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condinho, M.; Carvalho, B.; Cruz, A.; Pinto, S.N.; Arraiano, C.M.; Pobre, V. The Role of RNA Regulators, Quorum Sensing and c--di--GMP in Bacterial Biofilm Formation. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, J.L.; Patel, R. The Challenge of Treating Biofilm-Associated Bacterial Infections. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 82, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costerton, J.W.; Lewandowski, Z.; DeBeer, D.; Caldwell, D.; Korber, D.; James, G. Biofilms, the Customized Microniche. J Bacteriol 1994, 176, 2137–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderl, J.N.; Franklin, M.J.; Stewart, P.S. Role of Antibiotic Penetration Limitation in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Biofilm Resistance to Ampicillin and Ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 1818–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, K.J.; Sabath, L.D. Increased Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations with Anaerobiasis for Tobramycin, Gentamicin, and Amikacin, Compared to Latamoxef, Piperacillin, Chloramphenicol, and Clindamycin. Chemotherapy 1985, 31, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.N.; Dias, S.A.; Cruz, A.F.; Mil-Homens, D.; Fernandes, F.; Valle, J.; Andreu, D.; Prieto, M.; Castanho, M.A.R.B.; Coutinho, A.; et al. The Mechanism of Action of pepR, a Viral-Derived Peptide, against Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2019, 74, 2617–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Pinto, S.N.; Aires-da-Silva, F.; Bettencourt, A.; Aguiar, S.I.; Gaspar, M.M. Liposomes as a Nanoplatform to Improve the Delivery of Antibiotics into Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, K.K.; Goldmann, D.A.; Pier, G.B. Use of Confocal Microscopy To Analyze the Rate of Vancomycin Penetration through Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49, 2467–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, T.-F.C.; O’Toole, G.A. Mechanisms of Biofilm Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents. Trends in Microbiology 2001, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Siala, W.; Tulkens, P.M.; Van Bambeke, F. A Combined Pharmacodynamic Quantitative and Qualitative Model Reveals the Potent Activity of Daptomycin and Delafloxacin against Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 2726–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macia, M.D.; Rojo-Molinero, E.; Oliver, A. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing in Biofilm-Growing Bacteria. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2014, 20, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Young, P.; Traini, D.; Li, M.; Ong, H.X.; Cheng, S. Challenges and Current Advances in in Vitro Biofilm Characterization. Biotechnology Journal 2023, 18, 2300074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnsholt, T.; Alhede, M.; Alhede, M.; Eickhardt-Sørensen, S.R.; Moser, C.; Kühl, M.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N. The in Vivo Biofilm. Trends in Microbiology 2013, 21, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridier, A.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F.; Boubetra, A.; Thomas, V.; Briandet, R. The Biofilm Architecture of Sixty Opportunistic Pathogens Deciphered Using a High Throughput CLSM Method. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2010, 82, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Adults and Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2011, 52, e18–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mil-Homens, D.; Martins, M.; Barbosa, J.; Serafim, G.; Sarmento, M.J.; Pires, R.F.; Rodrigues, V.; Bonifácio, V.D.B.; Pinto, S.N. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clinical Isolates: In Vivo Virulence Assessment in Galleria Mellonella and Potential Therapeutics by Polycationic Oligoethyleneimine. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters.

- Marques, M.; Pobre, V.; Costa, S.S.; Pinto, S.N.; Silveira, H. Pseudomonas Mendocina Isolated from Anopheles Midguts Has a Greater Potential to Build Thick Biofilms than Serratia Marcescens. ACS Omega 2025, acsomega.5c01640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, O.; Merghni, A.; Elargoubi, A.; Rhim, H.; Kadri, Y.; Mastouri, M. Comparative Study of Virulence Factors among Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Clinical Isolates. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.-M.; Zhou, C.; Lindgren, J.K.; Galac, M.R.; Corey, B.; Endres, J.E.; Olson, M.E.; Fey, P.D. Transcriptional Regulation of icaADBC by Both IcaR and TcaR in Staphylococcus Epidermidis. J Bacteriol 2019, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobre, V.; Arraiano, C.M. Next Generation Sequencing Analysis Reveals That the Ribonucleases RNase II, RNase R and PNPase Affect Bacterial Motility and Biofilm Formation in E. Coli. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pobre, V.; Arraiano, C.M. Characterizing the Role of Exoribonucleases in the Control of Microbial Gene Expression: Differential RNA-Seq. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 2018; Vol. 612, pp. 1–24 ISBN 978-0-12-815993-4.

- El--Mahallawy, H.A.; Loutfy, S.A.; El--Wakil, M.; El--Al, A.K.A.; Morcos, H. Clinical Implications of icaA and icaD Genes in Coagulase Negative Staphylococci and Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia in Febrile Neutropenic Pediatric Cancer Patients. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2009, 52, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, Y.M.; Patel, R. Understanding Biofilms and Novel Approaches to the Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Medical Device-Associated Infections. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 2018, 32, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaig, L.F.; McDonald, L.C.; Mandal, S.; Jernigan, D.B. Staphylococcus Aureus –Associated Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in Ambulatory Care. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, D.; Prince, A. Immunopathogenesis of Staphylococcus Aureus Pulmonary Infection. Semin Immunopathol 2012, 34, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.R.W.; Allison, D.G.; Gilbert, P. Resistance of Bacterial Biofilms to Antibiotics a Growth-Rate Related Effect? J Antimicrob Chemother 1988, 22, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D. Understanding Biofilm Resistance to Antibacterial Agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003, 2, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Blanco, A.R.; Ginestra, G.; Nostro, A.; Bisignano, G. Ex Vivo Efficacy of Gemifloxacin in Experimental Keratitis Induced by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2016, 48, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacher--Rodarte, M.D.C.; Trejo--Muñúzuri, T.P.; Montiel--Aguirre, J.F.; Drago--Serrano, M.E.; Gutiérrez--Lucas, R.L.; Castañeda--Sánchez, J.I.; Sainz--Espuñes, T. Antibiotic Resistance and Multidrug--resistant Efflux Pumps Expression in Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Pozol, a Nonalcoholic Mayan Maize Fermented Beverage. Food Science & Nutrition 2016, 4, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, S.; Wenke, C.; Feßler, A.T.; Kacza, J.; Geber, F.; Scholtzek, A.D.; Hanke, D.; Eichhorn, I.; Schwarz, S.; Rosolowski, M.; et al. Borderline Resistance to Oxacillin in Staphylococcus Aureus after Treatment with Sub-Lethal Sodium Hypochlorite Concentrations. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.F.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Seleem, M.N. Evaluation of Short Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides for Treatment of Drug-Resistant and Intracellular Staphylococcus Aureus. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidari, A.; Sabbatini, S.; Schiaroli, E.; Perito, S.; Francisci, D.; Baldelli, F.; Monari, C. Tedizolid-Rifampicin Combination Prevents Rifampicin-Resistance on in Vitro Model of Staphylococcus Aureus Mature Biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, V.P.; Giatpaiboon, S.A.; Uhrig, J.; Orwin, P.; Wiesmann, W.; Baker, S.M.; Townsend, S.M. In Vitro Activity of Novel Glycopolymer against Clinical Isolates of Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-P.; He, H.; Hong, W.D.; Wu, T.-R.; Huang, G.-Y.; Zhong, Y.-Y.; Tu, B.-R.; Gao, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, S.-Q.; et al. The Biological Evaluation of Fusidic Acid and Its Hydrogenation Derivative as Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. IDR 2018, Volume 11, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophel, K.; Schacht, V.J.; Schlüter, M.; Schnell, S.; Stingu, C.-S.; Schaumann, R.; Bunge, M. The Importance of Growth Kinetic Analysis in Determining Bacterial Susceptibility against Antibiotics and Silver Nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.-L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Zhang, L.-J.; Zhang, W.; Jin, Y.-R.; Luo, X.-F.; Li, F.-P.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Bian, Q.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Quinoline Derivatives against Phytopathogenic Bacteria Inspired from Natural Quinine Alkaloids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, acs.jafc.4c05509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Barbosa, J.; Bernardes, N.; Avó, B.; Martinho, N.; Godinho-Santos, A.; Pinto, S.N.; Bonifácio, V.D.B. Designing Anticancer Polyurea Biodendrimers: The Role of Core–Shell Charge/Hydrophobicity Modulation. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 10.1039.D5BM01205H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoe, J.A.T.; Wysome, J.; West, A.P.; Heritage, J.; Wilcox, M.H. Measurement of Ampicillin, Vancomycin, Linezolid and Gentamicin Activity against Enterococcal Biofilms. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2006, 57, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natto, M.J.; Savioli, F.; Quashie, N.B.; Dardonville, C.; Rodenko, B.; De Koning, H.P. Validation of Novel Fluorescence Assays for the Routine Screening of Drug Susceptibilities of Trichomonas Vaginalis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2012, 67, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency Vancomycin Article-31 Referral Annex III (accessed on 29 June 2023). (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Neu, T.R.; Lawrence, J.R. In Situ Characterization of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) in Biofilm Systems. In Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances; Wingender, J., Neu, T.R., Flemming, H.-C., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999; pp. 21–47. ISBN 978-3-642-64277-7. [Google Scholar]

- Neu, T.R.; Lawrence, J.R. [10] Lectin-Binding Analysis in Biofilm Systems. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 1999; Vol. 310, pp. 145–152 ISBN 978-0-12-182211-8.

- Cruz, A.; Condinho, M.; Carvalho, B.; Arraiano, C.M.; Pobre, V.; Pinto, S.N. The Two Weapons against Bacterial Biofilms: Detection and Treatment. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, S.E.; Ulrich, M.; Götz, F.; Döring, G. Anaerobic Conditions Induce Expression of Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin in Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Infect Immun 2001, 69, 4079–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, F.; Humphreys, H.; O’Gara, J.P. Evidence for icaADBC -Independent Biofilm Development Mechanism in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 1973–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmantar, T.; Chaieb, K.; Makni, H.; Miladi, H.; Abdallah, F.B.; Mahdouani, K.; Bakhrouf, A. Detection by PCR of Adhesins Genes and Slime Production in Clinical Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Basic Microbiol. 2008, 48, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gara, J.P. Ica and beyond: Biofilm Mechanisms and Regulation in Staphylococcus Epidermidis and Staphylococcus Aureus. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2007, 270, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kot, B.; Sytykiewicz, H.; Sprawka, I. Expression of the Biofilm-Associated Genes in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Biofilm and Planktonic Conditions. IJMS 2018, 19, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, M.G.; Beyenal, H.; Dong, W.-J. Dual Roles of the Conditional Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms: Promoting and Inhibiting Bacterial Biofilm Growth. Biofilm 2024, 7, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matlock, B. Assessment of Nucleic Acid Purity. 2015.

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial Biofilms: A Common Cause of Persistent Infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toté, K.; Berghe, D.V.; Maes, L.; Cos, P. A New Colorimetric Microtitre Model for the Detection of Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms: New S. Aureus Biofilm Model. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2007, 46, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddi Oubekka, S.; Briandet, R.; Fontaine-Aupart, M.-P.; Steenkeste, K. Correlative Time-Resolved Fluorescence Microscopy To Assess Antibiotic Diffusion-Reaction in Biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 3349–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.G.; O’Toole, G.A. Innate and Induced Resistance Mechanisms of Bacterial Biofilms. In Bacterial Biofilms; Romeo, T., Ed.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008; Vol. 322, pp. 85–105. ISBN 978-3-540-75417-6. [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness, W.A.; Malachowa, N.; DeLeo, F.R. Vancomycin Resistance in Staphylococcus Aureus. Yale J Biol Med 2017, 90, 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Atshan, S.S.; Nor Shamsudin, M.; Sekawi, Z.; Lung, L.T.T.; Hamat, R.A.; Karunanidhi, A.; Mateg Ali, A.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Ghasemzadeh-Moghaddam, H.; Chong Seng, J.S.; et al. Prevalence of Adhesion and Regulation of Biofilm-Related Genes in Different Clones of Staphylococcus Aureus. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2012, 2012, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiefel, P.; Schmidt-Emrich, S.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Ren, Q. Critical Aspects of Using Bacterial Cell Viability Assays with the Fluorophores SYTO9 and Propidium Iodide. BMC Microbiol 2015, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.N.; Mil-Homens, D.; Pires, R.F.; Alves, M.M.; Serafim, G.; Martinho, N.; Melo, M.; Fialho, A.M.; Bonifácio, V.D.B. Core–Shell Polycationic Polyurea Pharmadendrimers: New-Generation of Sustainable Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics and Antifungals. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 5197–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, D.; Fischer, W.; Krokotsch, A.; Leopold, K.; Hartmann, R.; Egge, H.; Laufs, R. The Intercellular Adhesin Involved in Biofilm Accumulation of Staphylococcus Epidermidis Is a Linear Beta-1,6-Linked Glucosaminoglycan: Purification and Structural Analysis. J Bacteriol 1996, 178, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoramian, B.; Jabalameli, F.; Niasari-Naslaji, A.; Taherikalani, M.; Emaneini, M. Comparison of Virulence Factors and Biofilm Formation among Staphylococcus Aureus Strains Isolated from Human and Bovine Infections. Microbial Pathogenesis 2015, 88, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, N.M.; Jefferson, K.K. A Low Molecular Weight Component of Serum Inhibits Biofilm Formation in Staphylococcus Aureus. Microbial Pathogenesis 2010, 49, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathmann, M.; Wingender, J.; Flemming, H.-C. Application of Fluorescently Labelled Lectins for the Visualization and Biochemical Characterization of Polysaccharides in Biofilms of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2002, 50, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogman, M.E.; Vuorela, P.M.; Fallarero, A. Combining Biofilm Matrix Measurements with Biomass and Viability Assays in Susceptibility Assessments of Antimicrobials against Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. J Antibiot 2012, 65, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydorn, A.; Ersbøll, B.; Kato, J.; Hentzer, M.; Parsek, M.R.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S. Statistical Analysis of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Development: Impact of Mutations in Genes Involved in Twitching Motility, Cell-to-Cell Signaling, and Stationary-Phase Sigma Factor Expression. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, J.; Golub, S.; Allan, W.; Simmons, M.J.H.; Overton, T.W. Non-Pathogenic Escherichia Coli Biofilms: Effects of Growth Conditions and Surface Properties on Structure and Curli Gene Expression. Arch Microbiol 2020, 202, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachid, S.; Ohlsen, K.; Witte, W.; Hacker, J.; Ziebuhr, W. Effect of Subinhibitory Antibiotic Concentrations on Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin Expression in Biofilm-Forming Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 3357–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, E.; Pozzi, C.; Houston, P.; Humphreys, H.; Robinson, D.A.; Loughman, A.; Foster, T.J.; O’Gara, J.P. A Novel Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilm Phenotype Mediated by the Fibronectin-Binding Proteins, FnBPA and FnBPB. J Bacteriol 2008, 190, 3835–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, P.; Rowe, S.E.; Pozzi, C.; Waters, E.M.; O’Gara, J.P. Essential Role for the Major Autolysin in the Fibronectin-Binding Protein-Mediated Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilm Phenotype. Infect Immun 2011, 79, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quendera, A.P.; Pinto, S.N.; Pobre, V.; Antunes, W.; Bonifácio, V.D.B.; Arraiano, C.M.; Andrade, J.M. The Ribonuclease PNPase Is a Key Regulator of Biofilm Formation in Listeria Monocytogenes and Affects Invasion of Host Cells. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target gene | Chain | Sequence (5’-3’) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | Forward | 5’ - GTGGAGGGTCATTGGAAACT - 3’ | This work |

| Reverse | 5’ - CACTGGTGTTCCTCCATATCTC - 3’ | ||

| icaA | Forward_1 | 5’ - TTTCGGGTGTCTTCACTCTATTT - 3’ | This work |

| Reverse_1 | 5’ - TGGCAAGCGGTTCATACTT - 3’ | ||

| Forward_2 | 5’ - ACACTTGCTGGCGCAGTCAA - 3’ | [29] | |

| Reverse_2 | 5’ - TCTGGAACCAACATCCAACA - 3’ |

| Antibiotic | ATCC 6538 | pHUA585 |

|---|---|---|

| Benzylpenicillin | S | R |

| Oxacillin | S | R |

| Gentamicin | S | S |

| Levofloxacin | I [35] | R |

| Moxifloxacin | S | R |

| Erythromycin | S [36] | R |

| Clindamycin | R [36] | *R |

| Vancomycin | S | S |

| Teicoplanin | S [37] | S |

| Linezolid | S [38] | S |

| Daptomycin | S [39] | S |

| Tetracycline | S [36] | S |

| Mupirocin | S [40] | S |

| Rifampicin | S | S |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | S | S |

| Fusidic acid | S [41] | S |

| Strain | RNA concentration (ng/µL) | A260/A280 | A260/A230 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilms | ATCC 6538 | 1318.8 | 2.14 | 2.02 |

| pHUA585 | 1005.4 | 2.13 | 1.76 | |

| Planktonic cells | ATCC 6538 | 1349.6 | 2.14 | 2.20 |

| pHUA585 | 1009.0 | 2.22 | 2.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).