Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Forecasting ILI values based on monthly and annual data sources [18];

- Identifying the limitations of using annual average Non-Revenue Water (NRW) values, particularly due to the masking effects of consumption fluctuations and network upgrades [19];

- Estimating the ILI through methodologies based on the analysis and measurement of Minimum Night Flow (MNF) [20];

- Determining the ILI using the Geographic Information System (GIS) tools to support strategic decision-making, spatial identification of leakage hotspots, and realistic estimation of potential financial recovery from leakage control interventions [21];

- Applying environmental valuation frameworks to determine the Economic Level of Leakage (ELL) under arid conditions, as demonstrated in the Al-Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. The model assumes the reduction of real losses to the Unavoidable Real Losses (URL) threshold, equivalent to an ILI value of 1 [22];

- Assessing the impact of pressure management implementation on the ILI as a key performance indicator for water loss control [23];

- Developing robust methodologies for ILI estimation in large-scale, non-homogeneous water distribution systems, incorporating the variability of service connection lengths and average operating pressures, along with conducting sensitivity analyses of the contributing parameters [24].

- Hourly water balance calculations within DMAs [26];

- Real-time water consumption monitoring systems at an individual user level, enabling rapid leak detection and prompt operational response within the water distribution network [27];

- Assessment of water losses in distribution networks where the AMI systems enable synchronous readings, i.e., measurements taken simultaneously from all water meters [32];

- Identification of leaks at the customer level [33].

- Can the analysis of the Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) at a District Metered Area (DMA) level serve as a useful tool for assessing current water losses and supporting operational management?

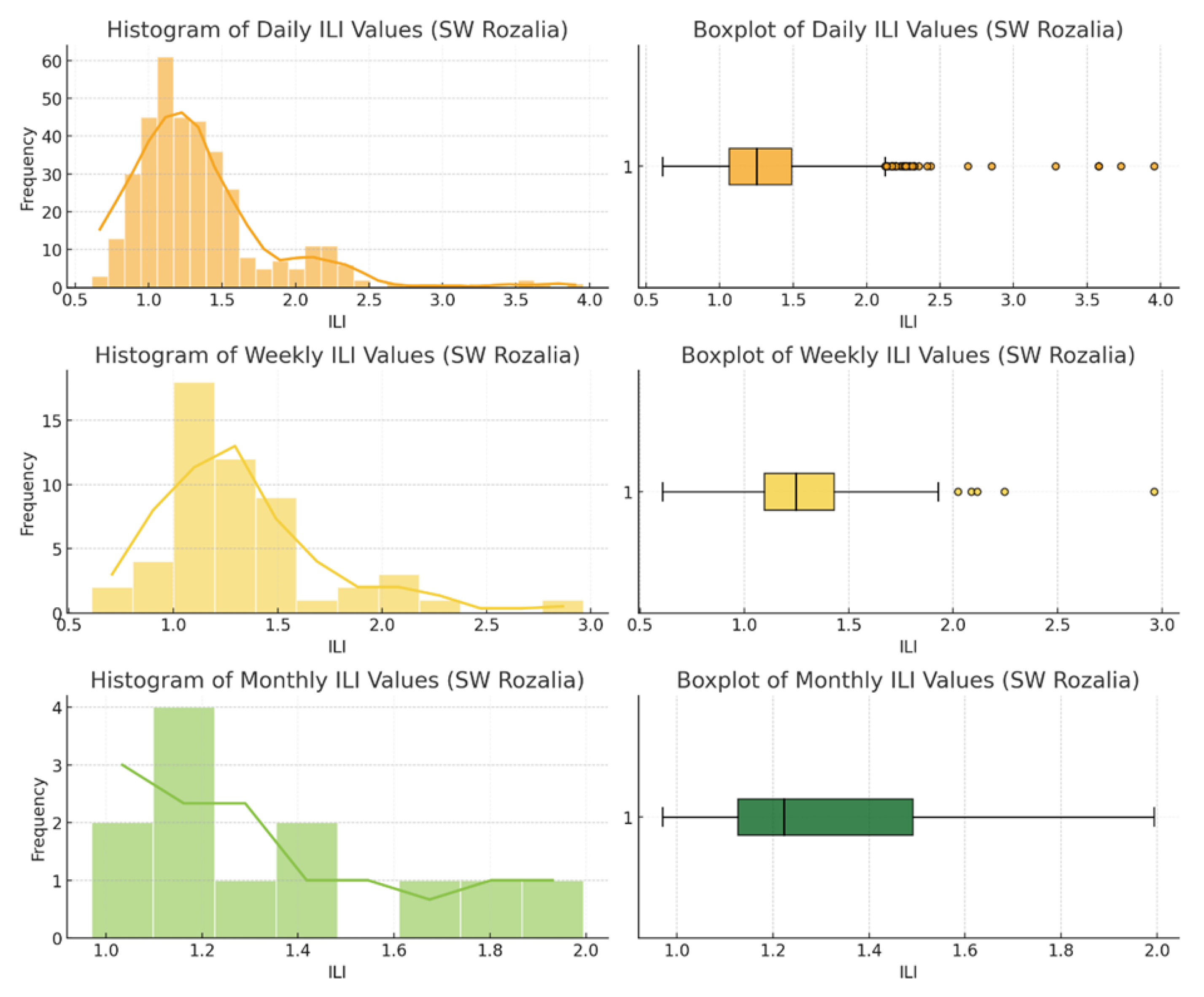

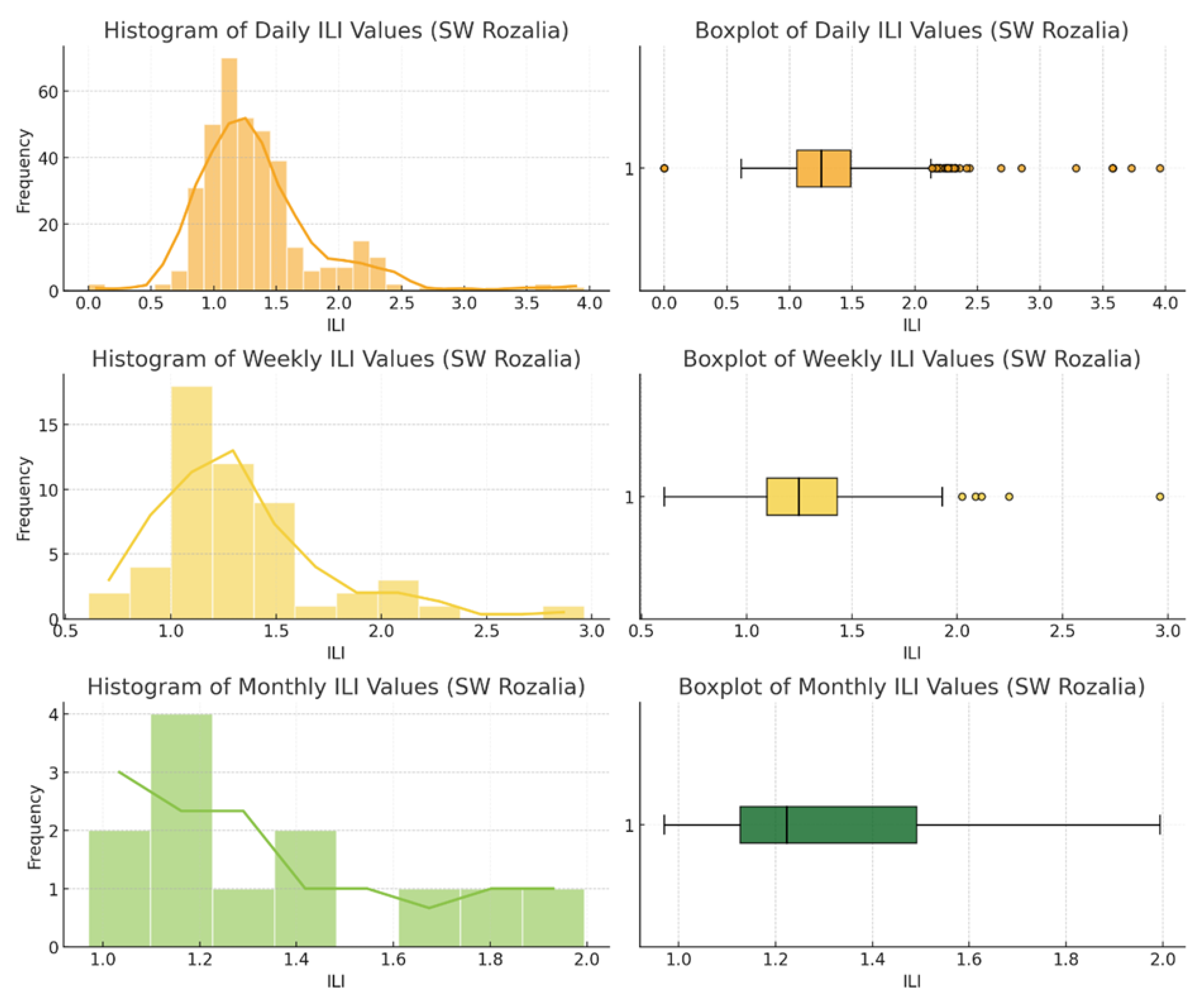

- What is the variability of ILI values when calculated on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis?

- Does the analysis of the ILI at daily, weekly, and monthly resolutions enhance the effectiveness of operational response?

- Do variability parameters of the ILI (calculated for each day, week, and month) differ significantly between DMAs?

- What factors influence the variability of ILI values?

- What new insights can be gained from a daily-resolution ILI analysis, and can this approach be effectively utilized in water loss management?

- For what purposes can the ILI, determined at different temporal intervals, be applied?

- What level of real (physical) water losses corresponds to the calculated ILI values?

2. Materials and Methods

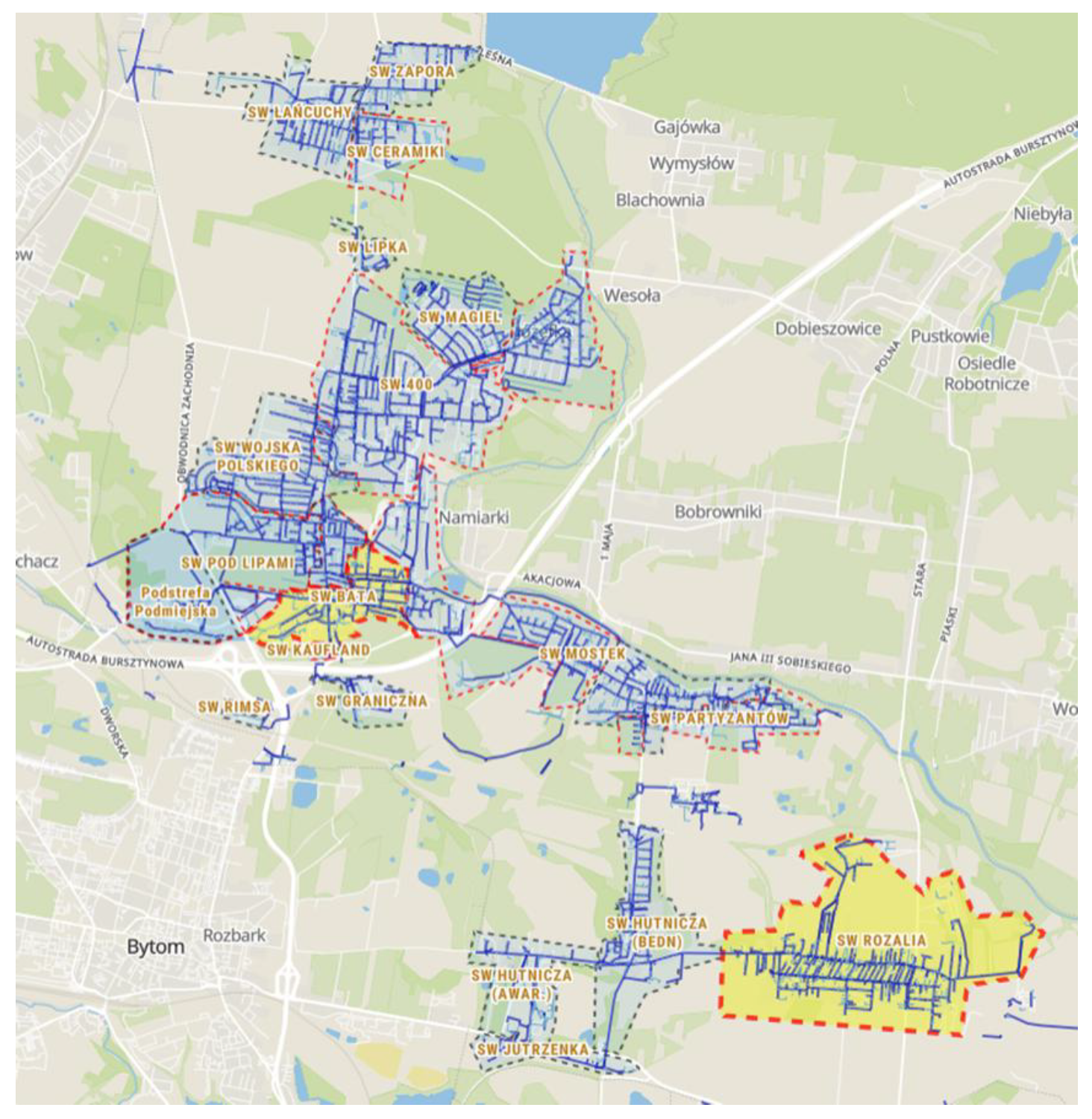

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

- Estimation of ILI values for the analyzed DMAs based on hourly data for each day, week, and month throughout the year of 2024. The Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) values were calculated using high-resolution hourly data, including flow measurements from the inlet points supplying the respective zones and hourly water consumption data from all customers assigned to each DMA.

- 2.

- Analysis of the variability of the calculated ILI values using statistical methods for the studied water distribution zones.

- 3.

- Comparative analysis of the variability indicators derived from the analyzed zones.

- 4.

- Assessment of the usefulness of ILI values calculated on daily, weekly, and monthly intervals for operational management of water distribution systems at the DMA level.

- 5.

- Identification and characterization of atypical operating conditions within the DMAs that significantly influence ILI variability or hinder the accurate determination of its value.

3. Results

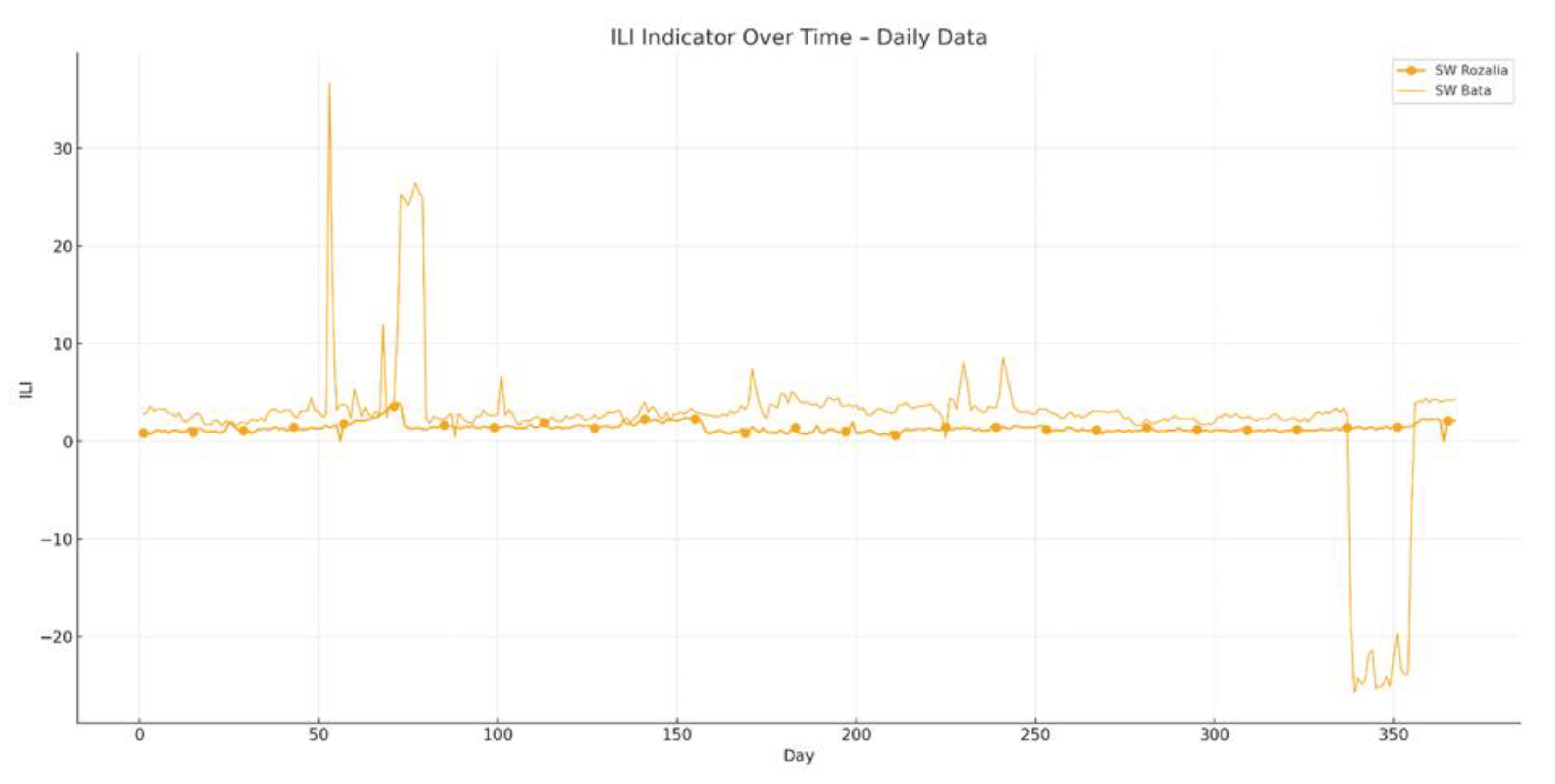

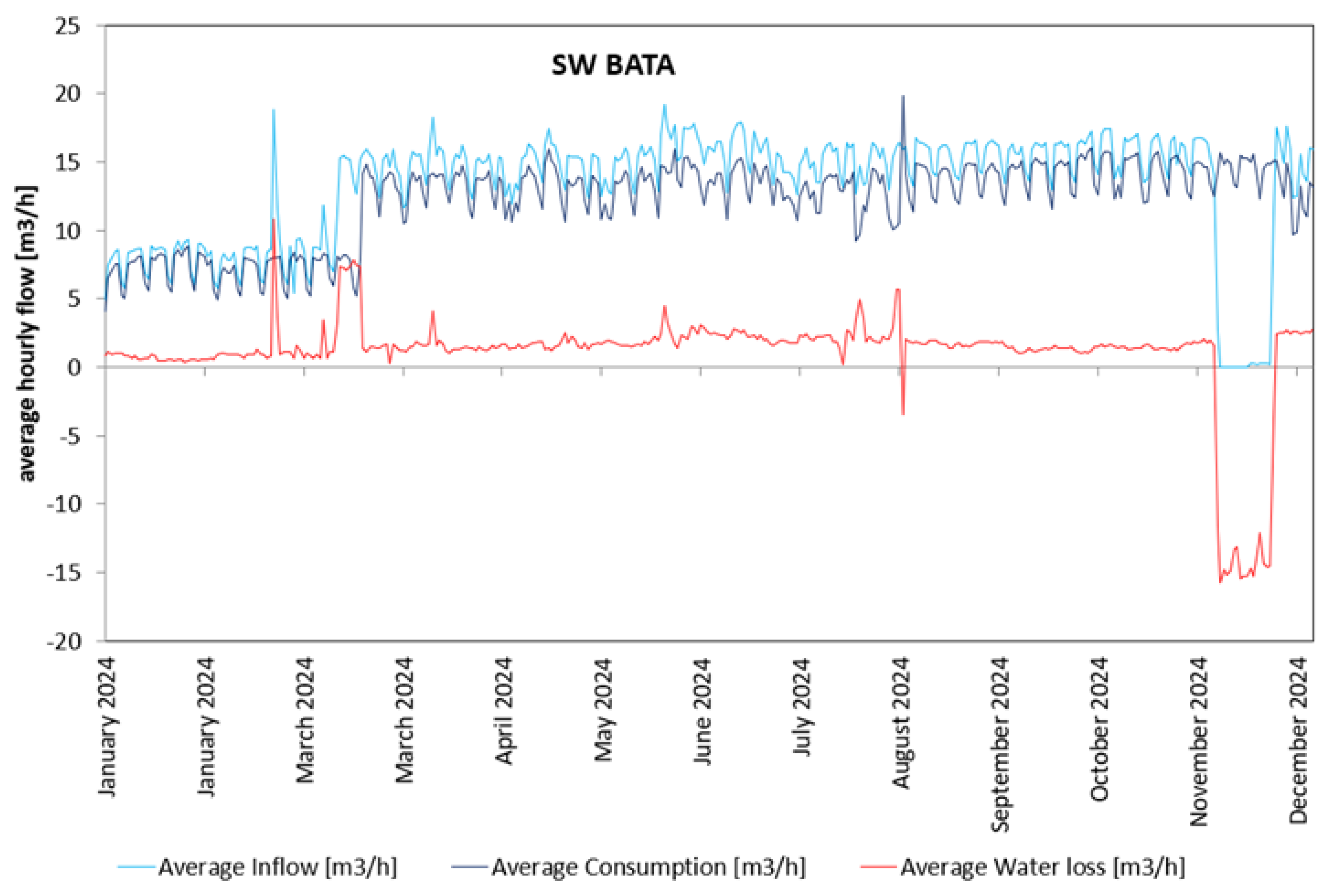

- February 21, 2024 – SW Bata has taken over the water supply for the entire SW Janty zone.

- March 7, 2024 – SW Bata has taken over the water supply for the entire SW Janty zone.

- March 16, 2024 – Extension of the zone to include part of the consumers from SW Janty, without adjusting/assigning their consumption to SW Bata.

- April 9, 2024 – Connection of the SW Bata with the SW Pod Lipami Górka.

- June 18, 2024 – Probable water main failure.

- August 16, 2024 – Missing consumption data from a large water user.

- December 3, 2024 – A failure occurred in the supplier’s network, as a result of which MPWiK interconnected several zones into one, supplied from multiple points, thus making an analysis impossible.

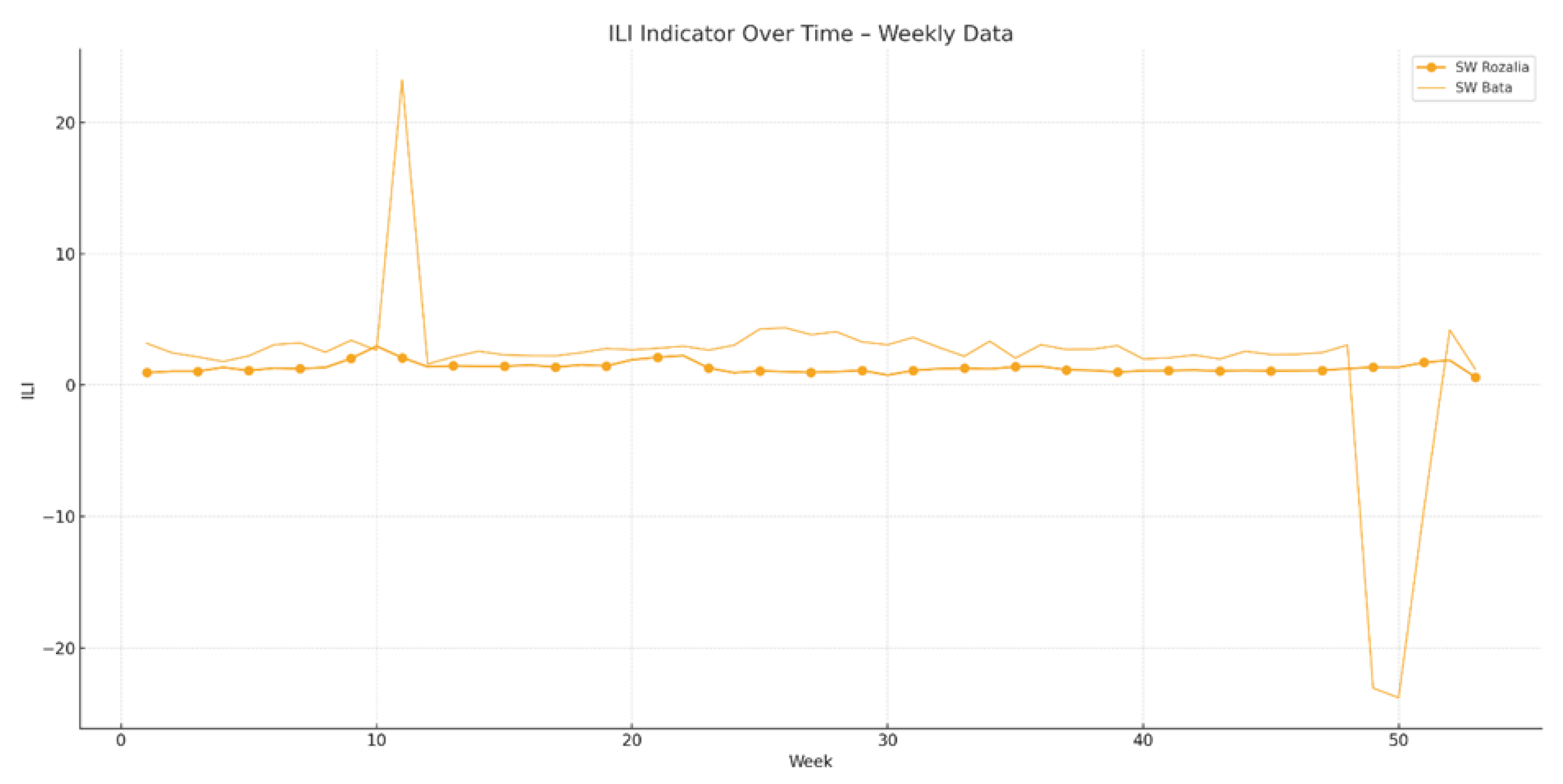

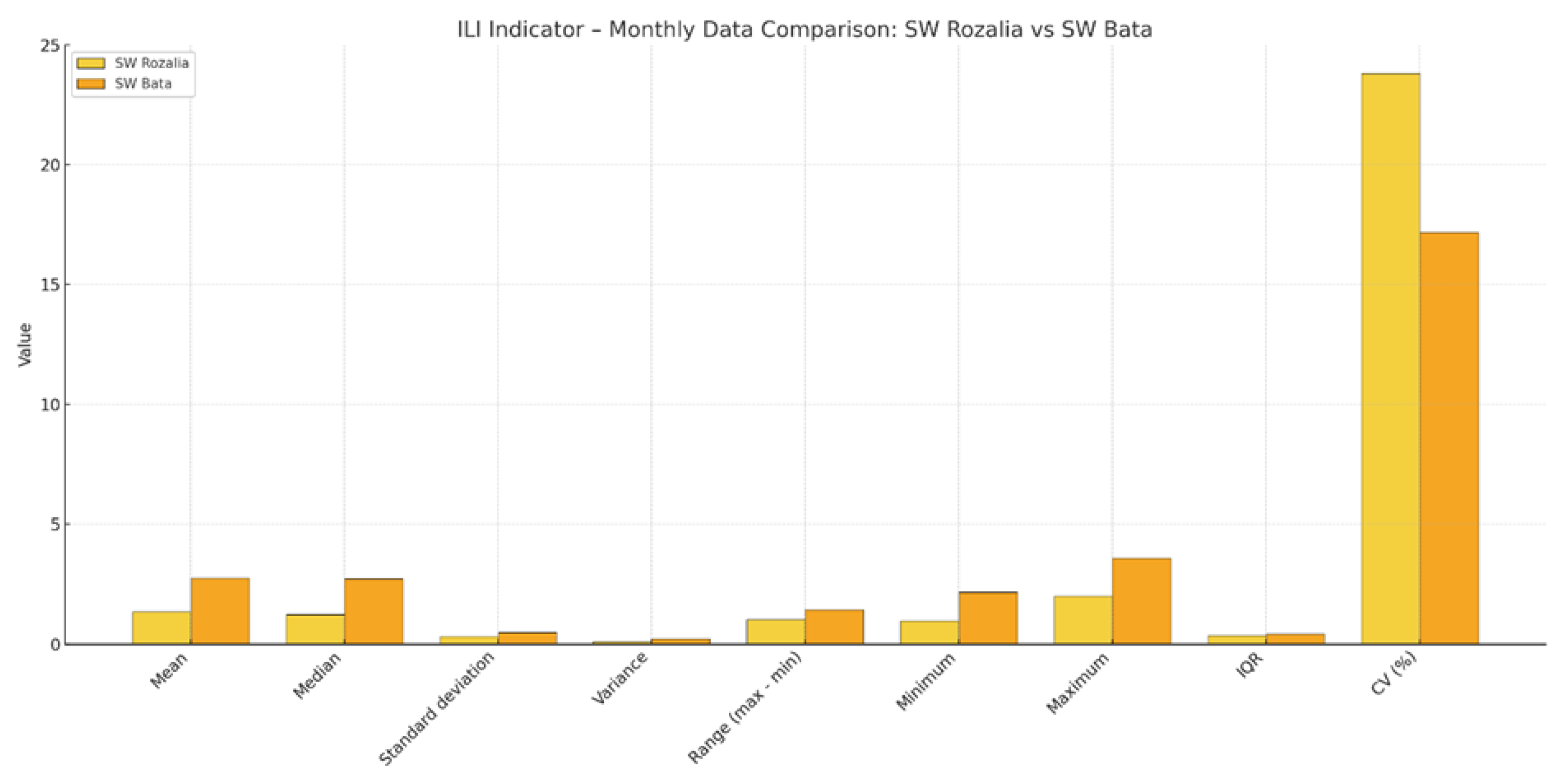

- Daily CV = 27.76% – moderate variability; some sensitivity to short-term events;

- Weekly CV = 24.95% – lower variability; more stable than daily data;

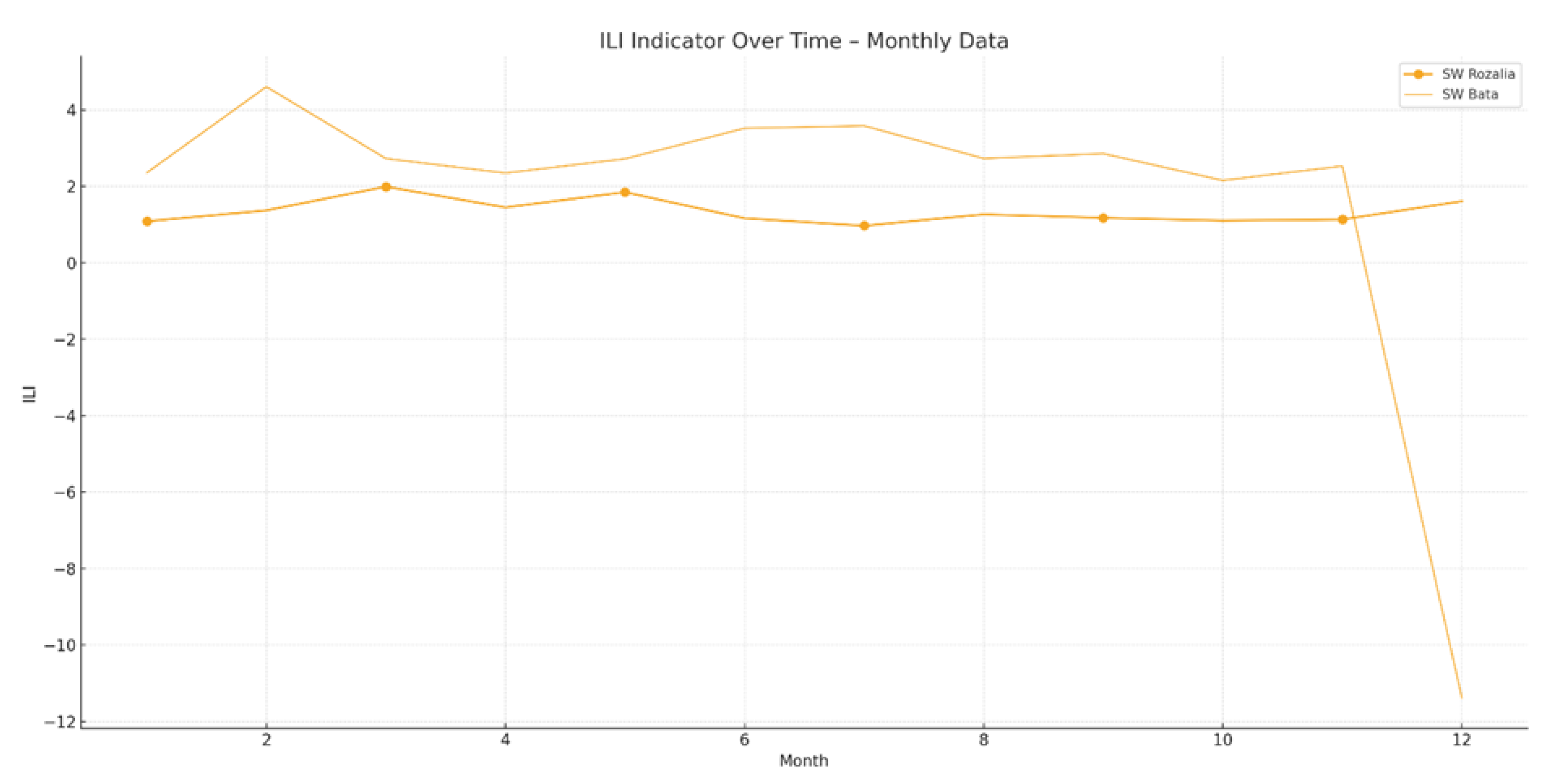

- Monthly CV = 17.19% – relatively low variability; well suited for reporting and performance tracking.

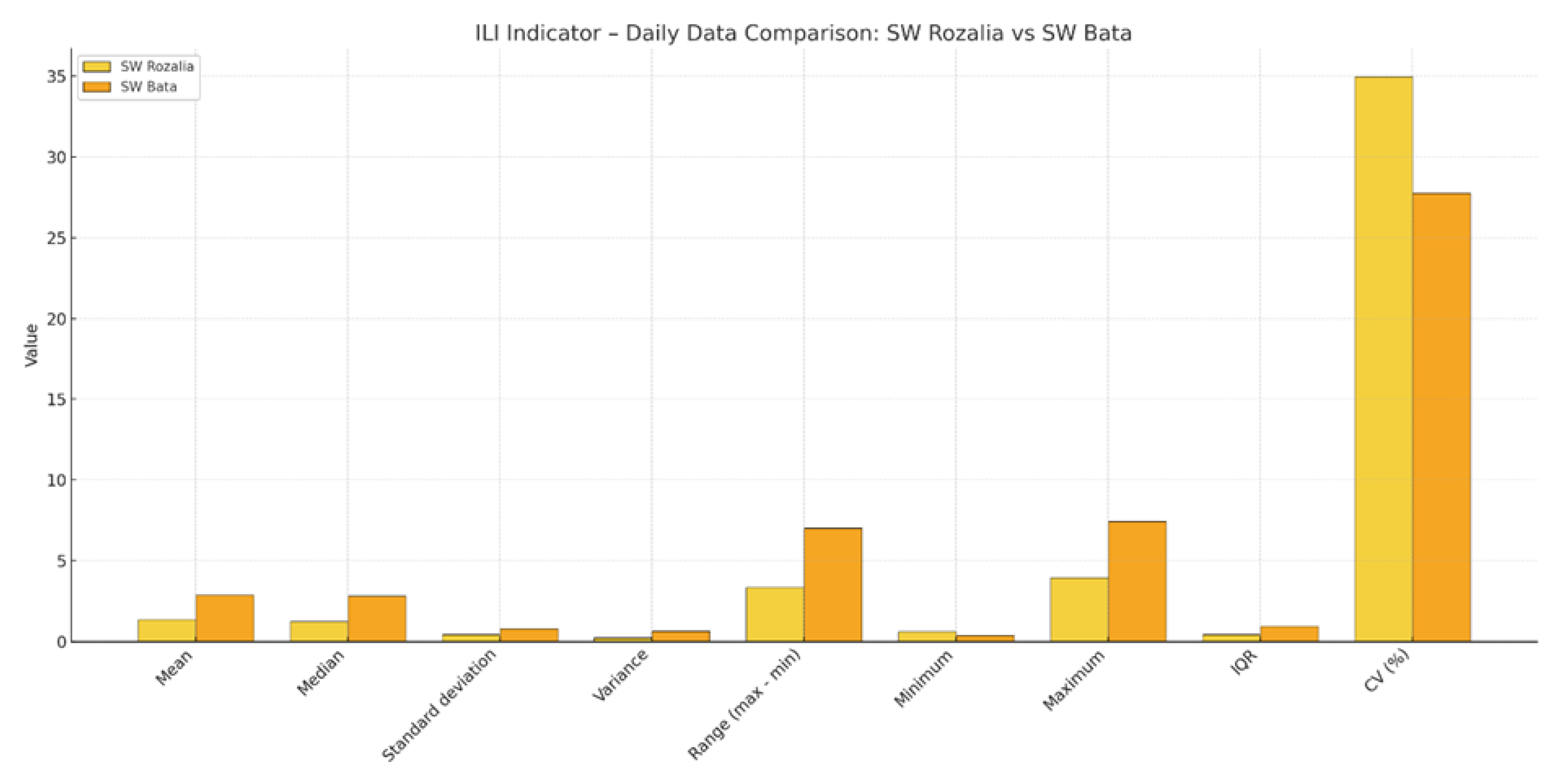

- Daily data – SW Bata shows a much higher ILI level (mean/median ≈ 2 × SW Rozalia) and a wider absolute spread (higher SD, range, IQR). Relative variability is lower in SW Bata (CV ≈ 28%) than in SW Rozalia (≈ 35%), i.e., higher losses but proportionally more stable day-to-day behavior.

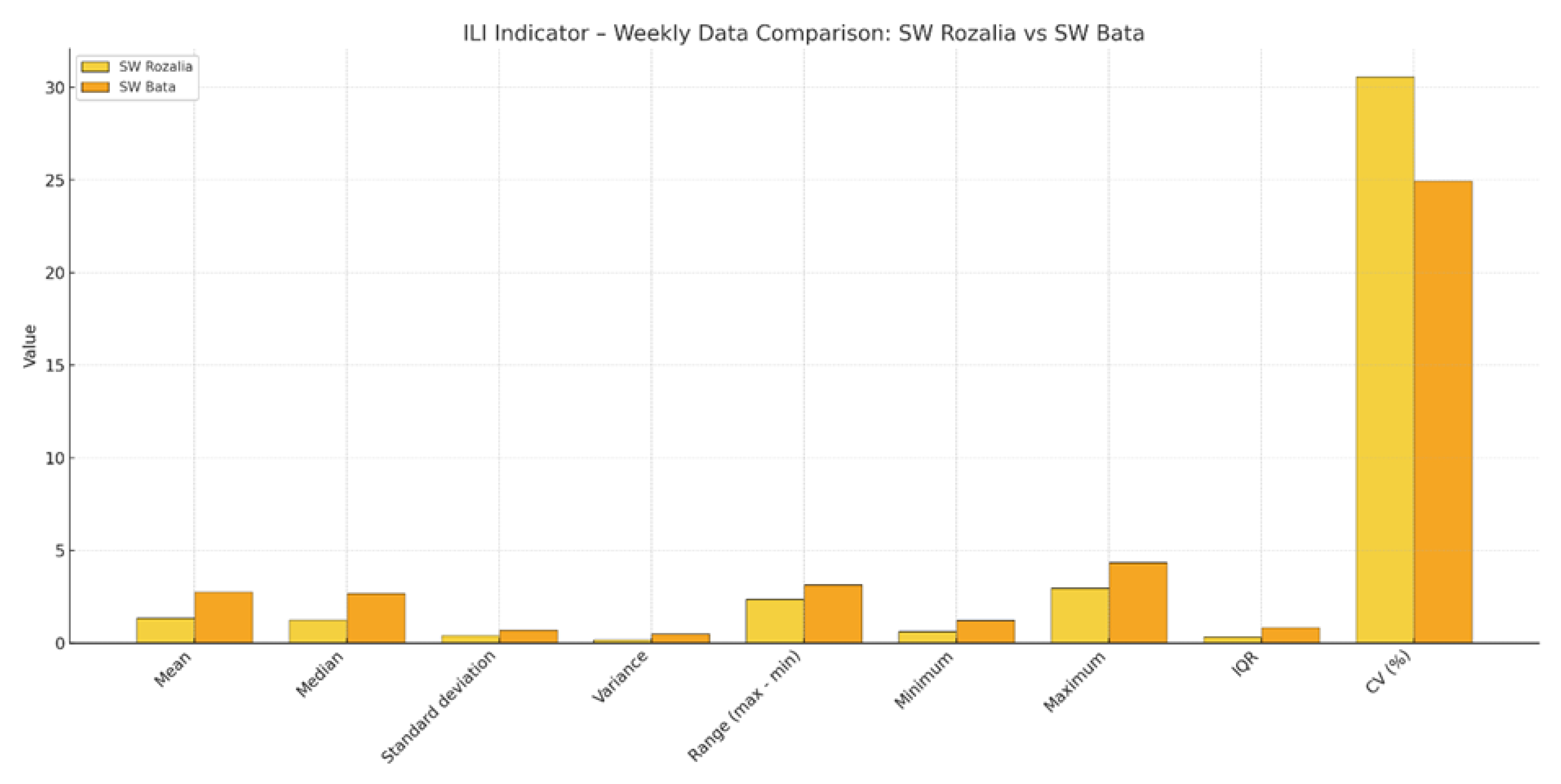

- Weekly data – The pattern persists: higher ILI level and larger absolute dispersion in SW Bata, with lower CV than SW Rozalia (≈ 25% vs ≈ 31%). Weekly aggregation smooths the short-term noise in both zones.

- Monthly data – Aggregation further reduces variability. SW Bata retains a higher average ILI than SW Rozalia, while CV remains lower in SW Bata (≈ 17% vs ≈ 24%), indicating a higher baseline of real losses but relatively steady month-to-month behavior.

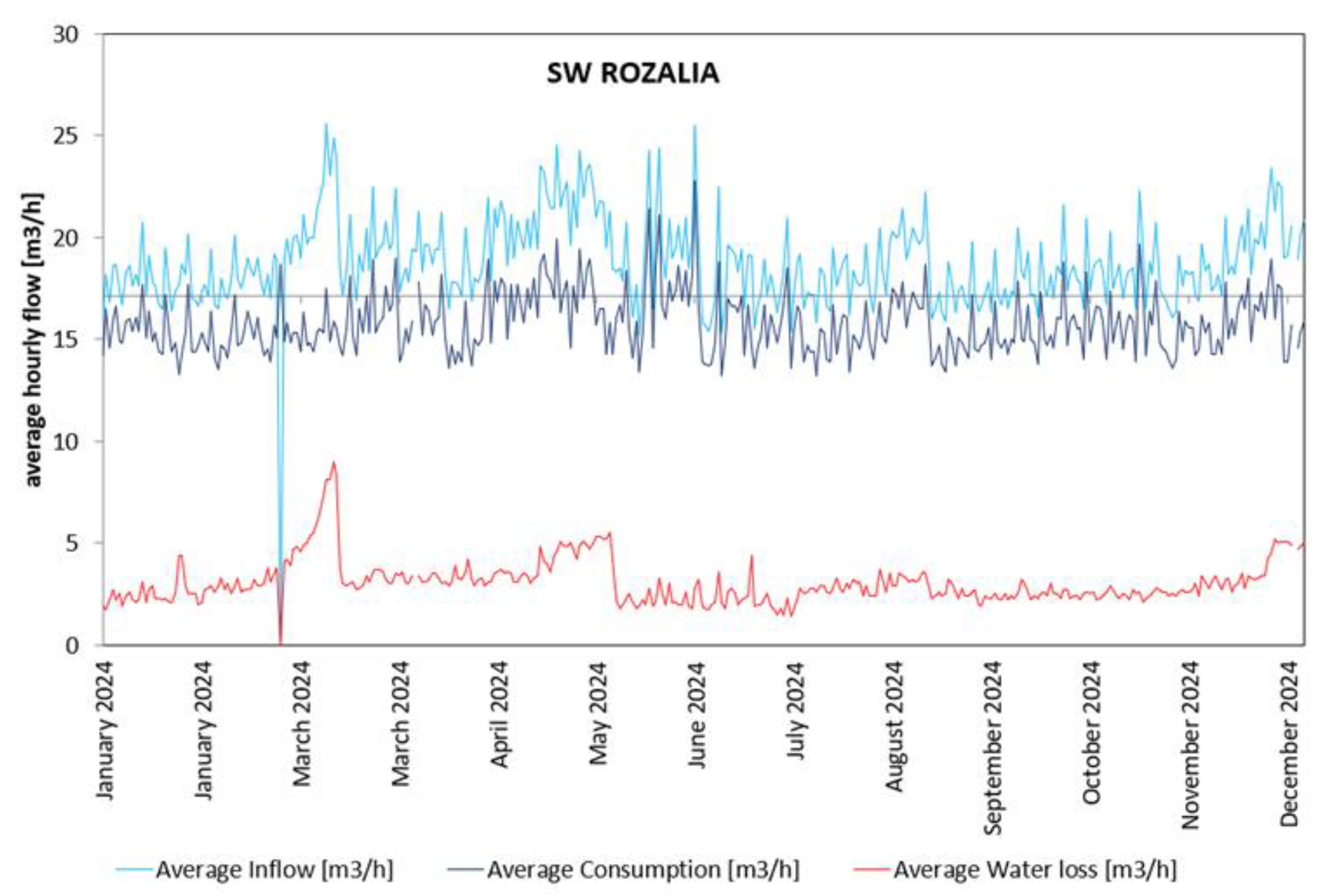

Analysis of Hourly Water Balance Components for SW Bata and SW Rozalia in 2024

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI | Advanced Metering Infrastructure |

| AOP | average operating pressure in the network |

| CARL | Current Annual Real Losses |

| DMA | District Metered Areas |

| ELL | Economic Level of Leakage |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| ILI | Infrastructure Leakage Index |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| MPWiK | Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Wodociągów i Kanalizacji Sp. z o.o. w Piekarach Śląskich, Poland (Water and Wastewater Utility in Piekary Śląskie, Poland) |

| PMA | Pressure Management Area |

| SCF | System Factor Coefficient |

| UARL | Unavoidable Annual Real Losses |

References

- Lambert, A.O., Brown, T.G., Takizawa, M., Weimer, D. A Review of Performance Indicators for Real Losses from Water Supply Systems. AQUA 1999, 48(6), pp. 227–237. [CrossRef]

- Hirner, W., Lambert, A. Losses from water supply systems: standard terminology and recommended performance measures, IWA the Blue Pages 2000.

- Winarni, W. Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) as Water Losses Indicator. Civ. Eng. Dimens. 2009, 11(2), pp. 126–134. https://doi.org/10.9744/ced.11.2.pp.%20126-134.

- Yilmaz, S., Firat, M., Özdemir, Ö. Using the Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) indicator for effective and sustainable leakage management: importance, advantages and challenges. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2022, 40(4), pp. 715–723. [CrossRef]

- Ahopelto, S., Vahala, R. Which Water Loss Indicator is Best for Inter-Utility Comparison and Leakage-Target Setting? SSRN Electron. J. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mazzolani, G., Ciliberti, F.G., Berardi, L., Giustolisi, O. Assessing Water Performance Indicators for Leakage Reduction and Asset Management in Water Supply Systems, arXiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Offermann, M., Sosa Solano, B.R., Juschak, M. Study on the Application of the Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) in Germany – Calculation Methodology, Analysis, Recommendations, DVGW Research Project W 202310, 2024.

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj/eng (Accessed on 27th May 2025).

- American Water Works Association. Manual M36: Water Audits and Loss Control Programs, 4th ed.; Denver, USA, 2016.

- Texas Water Loss Audit Program. Available online: https://www.twdb.texas.gov/conservation/Municipal/waterloss/index.asp (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- Senate Bill No. 555 (California). Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202320240SB555 (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- National Performance Report (Australia). Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/water/npr/framework-review (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- Water New Zealand. Water Loss Guidelines. Available online: https://www.waternz.org.nz/Article?Action=View&Article_id=2542 (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- The No Drop Programme. Driving Water Use Efficiency in the South African Water Sector. Available online: https://www.swpn.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/No-Drop-Programme-Final.pdf (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- The City of Guelph. Available from: https://guelph.ca/living/environment/water/ (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- Standards set by Superintendencia de Servicios Sanitarios – SISS. Available online: https://cl.boell.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/SERVICIOS%20SANITARIOS.pdf (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- The National Water Utility Mekorot. Available online: https://www.mekorot-int.com/ (Accessed 27th May 2025).

- Kızılöz, B., Şişman, E., Oruç, H.N. Predicting a water infrastructure leakage index via machine learning, Util. Policy 2022, 75, 101357. [CrossRef]

- Pathirane, A., Kazama, S., Takizawa, S. Dynamic analysis of non-revenue water in district metered areas under varying water consumption conditions owing to COVID-19, Heliyon 2024, 10(1), e23516. [CrossRef]

- Polachova, M., Tuhovcak, L. Determination of Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) Using Analyses of Minimum Night Flows, Eng. Proc. 2024, 69(1), 211. [CrossRef]

- Nahwani, A., Husin, A.E. Water Network Improvement Using Infrastructure Leakage Index and Geographic Information System, J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9(3), 909–914, pp. 909–914. [CrossRef]

- Haider, H. Environmental Valuation for Appraising the Economic Level of Leakage in Arid Environments: A Case of Qassim, Saudi Arabia. In Water Resources Management and Sustainability: Solutions for Arid Regions, Sefelnasr, A., Sherif, M., Singh, V.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2025, pp. 473–493. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S., Firat, M., Ateş, A., Özdemir, Ö. Analyzing the Effect of Pressure Management on Infrastructure Leakage Index in Distribution Systems based on Field Data, Research Square 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, C., Bragalli, C., Bolognesi, A., Fortini, M. Infrastructure Leakage Index Assessment in Large Water Systems, Procedia Eng. 2014, 70, pp. 1017–1026. [CrossRef]

- Hingmire, S., Paygude, P., Gayakwad, M., Devale, P. Probing to Reduce Operational Losses in NRW by using IoT, SSRG-IJEEE 2023, 10(6), pp. 28–38. [CrossRef]

- Luciani, C., Casellato, F., Alvisi, S., Franchini, M. Green Smart Technology for Water (GST4Water): Water Loss Identification at User Level by Using Smart Metering Systems, Water 2019, 11(3), 405. [CrossRef]

- Alvisi, S., Luciani, C., Franchini, M. Using water consumption smart metering for water loss assessment in a DMA: a case study, Urban Water J. 2019, 16(1), pp. 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Luciani, C., Casellato, F., Alvisi, S., Franchini, M. From Water Consumption Smart Metering to Leakage Characterization at District and User Level: The GST4Water Project, Proceedings 2018, 2(11), 675. [CrossRef]

- Bragalli, C., Neri, M., Toth, E. Effectiveness of smart meter-based urban water loss assessment in a real network with synchronous and incomplete readings, Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 112, pp. 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Koral W. Analiza danych z systemu stacjonarnego odczytu wodomierzy dla średniej wielkości miasta, INSTAL 2022, 12, pp. 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Gil, B., Koral, W. Analiza krzywych godzinowego zużycia wody na podstawie danych z systemu stacjonarnego odczytu wodomierzy, INSTAL 2021, 12, pp. 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Khaki, M., Mortazavi, N. Water Consumption Demand Pattern Analysis using Uncertain Smart Water Meter Data. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence 3–5 February 2022, 3, pp. 436–443. [CrossRef]

- Randall, T., Koech, R. Smart Water Metering Technology for Water Management in Urban Areas, Water e-Journal 2019, 4(1), pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Dzimińska, P., Stańczyk, J., Drzewiecki, S., Licznar, P. Wykorzystanie systemu rejestracji danych z dużą częstotliwością do analizy nierównomierności zużycia wody, INSTAL 2022, 1, pp. 24–30. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | SW Rozalia | SW Bata |

|---|---|---|

| Customer characteristics | mainly single-family housing, low-rise multi-family buildings (up to 4 floors), school, kindergarten, clinics, small services | hospital, public offices, commerce, education, sports fields (and irrigation), multi-family buildings (up to 4 floors) |

| Number of water customers (main meters) | 1208 | 357 |

| Length of water distribution network (km) | 25 | 4.4 |

| Length of water connections (km) | 12.1 | 2.1 |

| Number of water connections | 1012 | 109 |

| Average pressure (mH2O) | 36.0 | 36.6 before March 7, 2024 and 40.0 after |

| Reading effectiveness of customer meters in 2024 (%) | 92.2% | 87.63% |

| Number of customers with no meter data in 2024 | 21 | 1 |

| SCF Factor | 0.56 but 0.88 was adopted for further calculations* | 0.55 but 0.88 was adopted for further calculations* |

| ILI (2024) | 1.35 | 2.75 |

| SW Rozalia | SW Bata | |||||

| ILI daily | ILI weekly | ILI monthly | ILI daily | ILI weekly | ILI monthly | |

| Mean | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.35 | 2.88 | 2.74 | 2.75 |

| Median | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 2.81 | 2.67 | 2.73 |

| Standard deviation | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.47 |

| Variance | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.22 |

| Range (max − min) | 3.35 | 2.36 | 1.02 | 7.01 | 3.14 | 1.43 |

| Minimum | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 0.36 | 1.21 | 2.16 |

| Maximum | 3.96 | 2.96 | 1.99 | 7.43 | 4.35 | 3.59 |

| IQR | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.42 |

| CV (%) | 34.97 | 30.57 | 23.81 | 27.76 | 24.95 | 17.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).