Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Perform flow simulations around the concept using RANS methodology at Mach numbers , , and , and zero angle of attack;

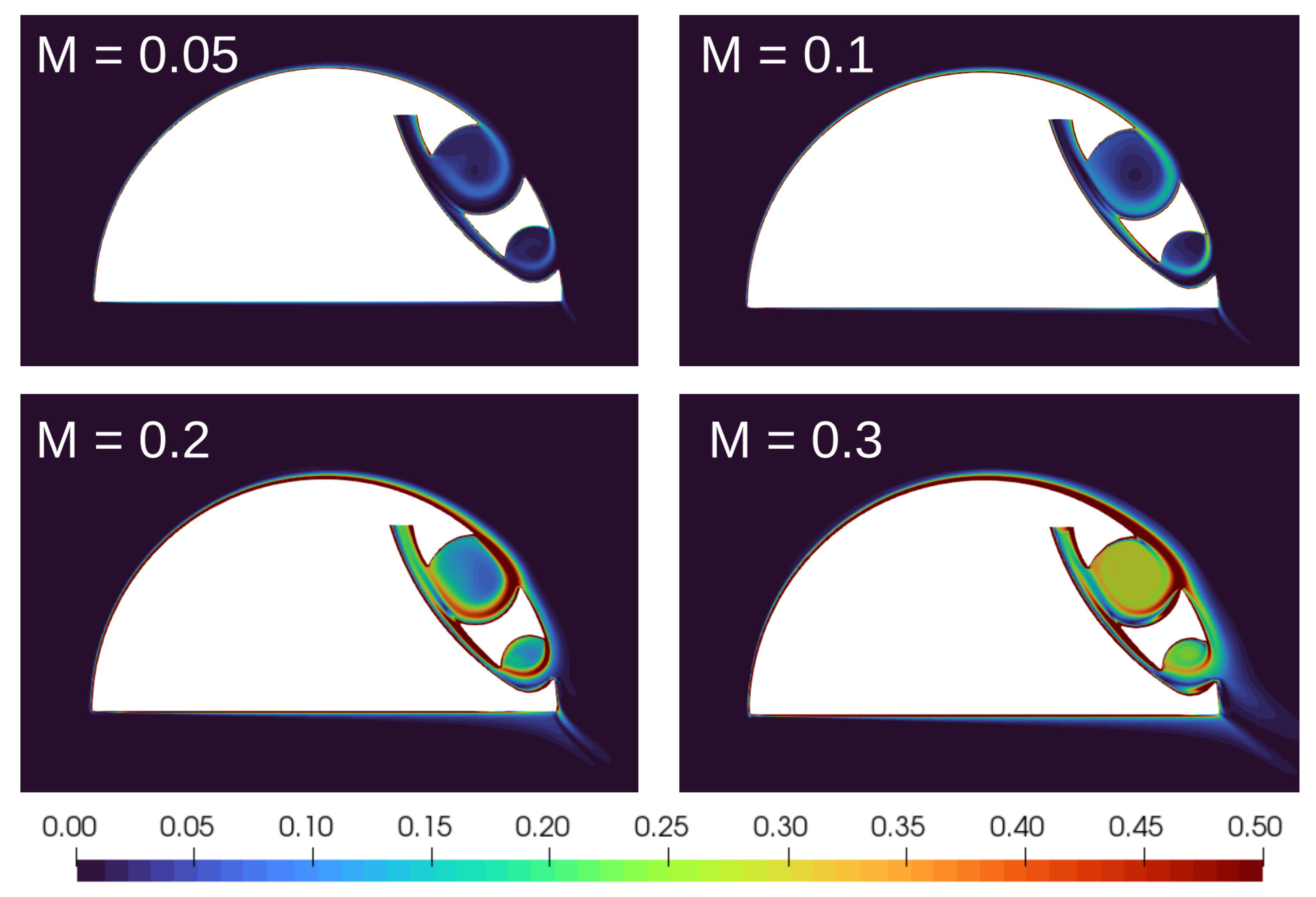

- Conduct cross-platform validation for the limiting case at , when the flow over airfoil’s upper surface becomes locally transonic, by comparing different numerical solvers for the compressible Navier-Stokes equations – specifically pressure-based, density-based, and hybrid approaches;

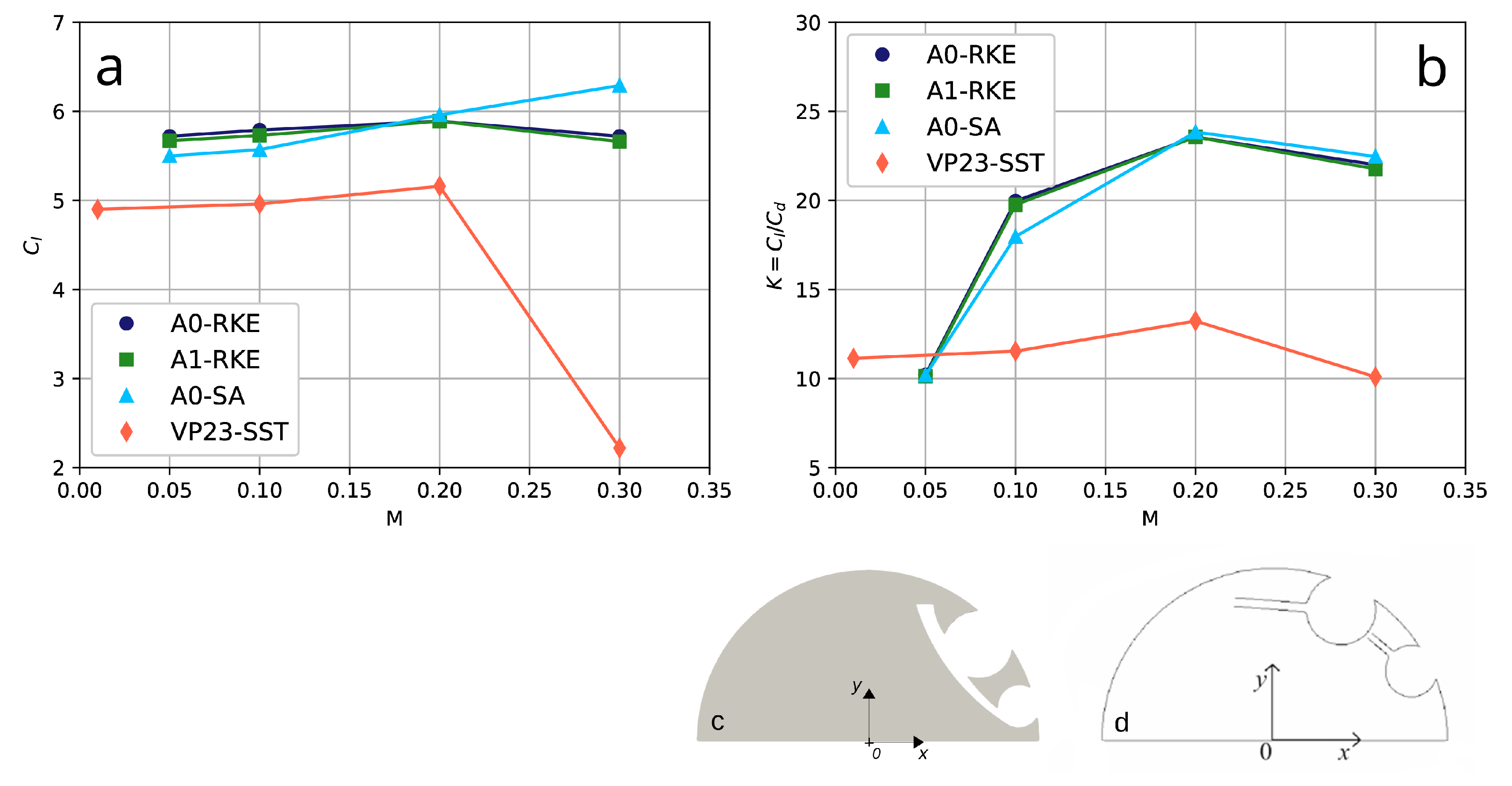

- Assess the impact of turbulence modeling by comparing Spalart-Allmaras (SA) and Realizable k- (RKE) models across the selected Mach number range; analyze the limiting case assuming the fluid inviscid.

- Highlight the significance of accurately specifying thermodynamic properties of air, such as viscosity, heat capacity, and thermal conductivity, and their influence on integral aerodynamic characteristics;

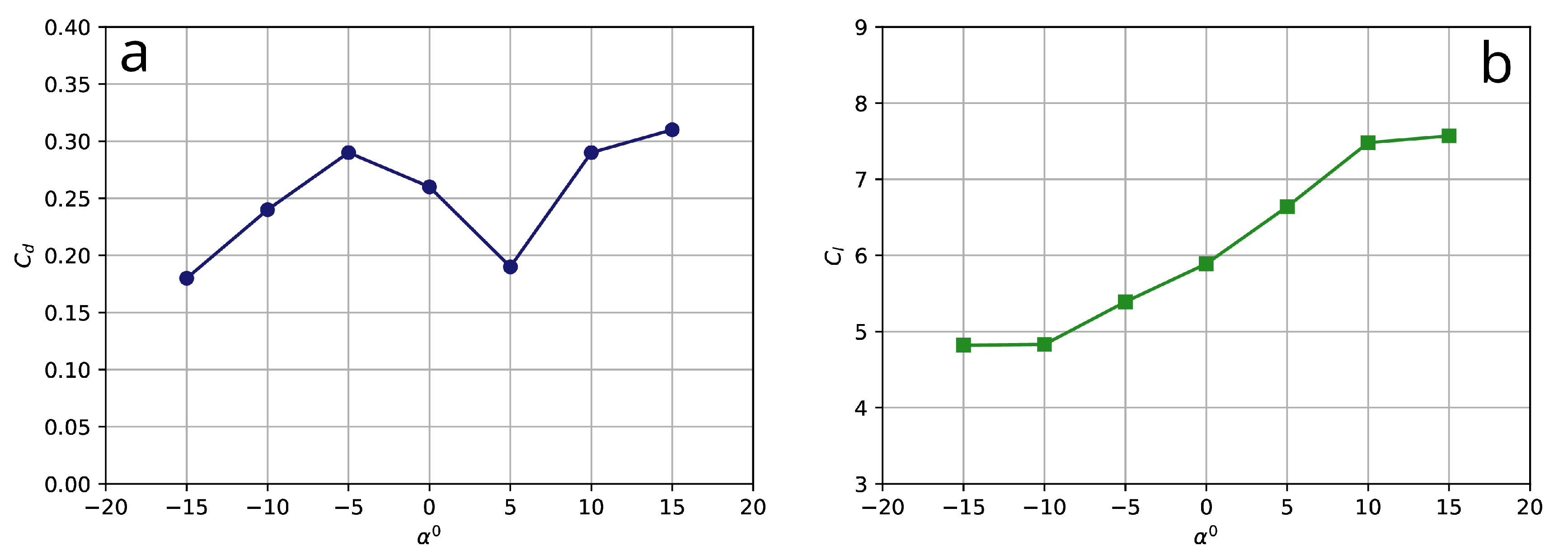

- Analyze the aerodynamic performance of the system at various angles of attack within the range of ;

- Ultimately, the study revealed that the aerodynamic performance of the system remains largely unaffected by Mach numbers up to , consistently maintaining the fully unseparated flow. Under cruise conditions at , this behavior is associated with a high lift coefficient of , which corresponds to approximately of the theoretical maximum value of . The resulting lift-to-drag ratio is around 24.

2. Problem Statement and Theoretical Considerations

2.1. Overview of the Aerodynamic Flow Control Concept Based on the Trapped Vortex Cells

2.2. Basic Governing Equations

2.3. The Spalart-Allmaras Turbulence Model

2.4. The Realizable k- Turbulence Model

2.5. Basic Governing Equations in Conservative Form

3. Brief Aspects of Numerical Simulations

3.1. Overview of the Numerical Methodology

- Pressure-based approach belongs to a general class of methods called the projection method [20,21], where the continuity of the velocity filed is achieved by solving pressure-correction equation. The pressure-based solver is implemented as a finite volume method (FVM) utilizing a second-order upwind scheme (SOU) for all convective terms and an implicit Euler method (bounded BDF-2) for time integration [22]. The time integration step is chosen to ensure that the local Courant number is less than ten, . The so-called pressure-based coupled algorithm is used, which solves a coupled systems of equations comprising the momentum and pressure-based continuity equations. The system of linear algebraic equations is solved using the algebraic multigrid method (AMG) accompanied by the additive correction strategy [23] and the classical iterative Gauss-Seidel procedure.

- Density-based approach is a Godunov-type FVM solver. In his classical paper of 1959, Godunov [24] presented a conservative extension of the first–order upwind scheme to non-linear systems of hyperbolic conservation laws. The key ingredient of the scheme is the solution of the Riemann problem [25], which is approximated by the advection upstream splitting method (AUSM) [26] in the present study. Other numerical aspects like time integration, discretization schemes and linear solvers were set up in the same spirit as for the pressure-based approach.

- Hybrid approach is alternative method to integrate the mass, momentum and energy conservative equations by coupling the PIMPLE (combination of PISO/SIMPLE) algorithm [27] with a corresponding Kurganov-Noelle-Petrova scheme (KNP) [28] for non-oscillating discretization of the convective and diffusive terms. The hybrid method based on the coupled PIMPLE algorithm and KNP scheme meets the requirements on monotonicity and allows to simulate turbulent flows in a wide range of a Mach number, . The hybrid approach was implemented as a so-called `pimpleCentralFoam’ solver based on FVM supported by the OpenFOAM platform [19] with specific details provided by Krpaposhin et al. [29]. A stabilized preconditioned (bi)-conjugate gradients method (PBiCGStab) accompanied by the diagonal incomplete-LU preconditioner was used to solve the linear systems of the algebraic equations with the absolute tolerance of . A limited advection scheme, so called `vanLeer’ [30], which belong to a family of TVD schemes, was utilized to approximate convective and diffusive fluxes computed by KNP. Integration in time was handled by the first-order implicit Euler method with a restriction of .

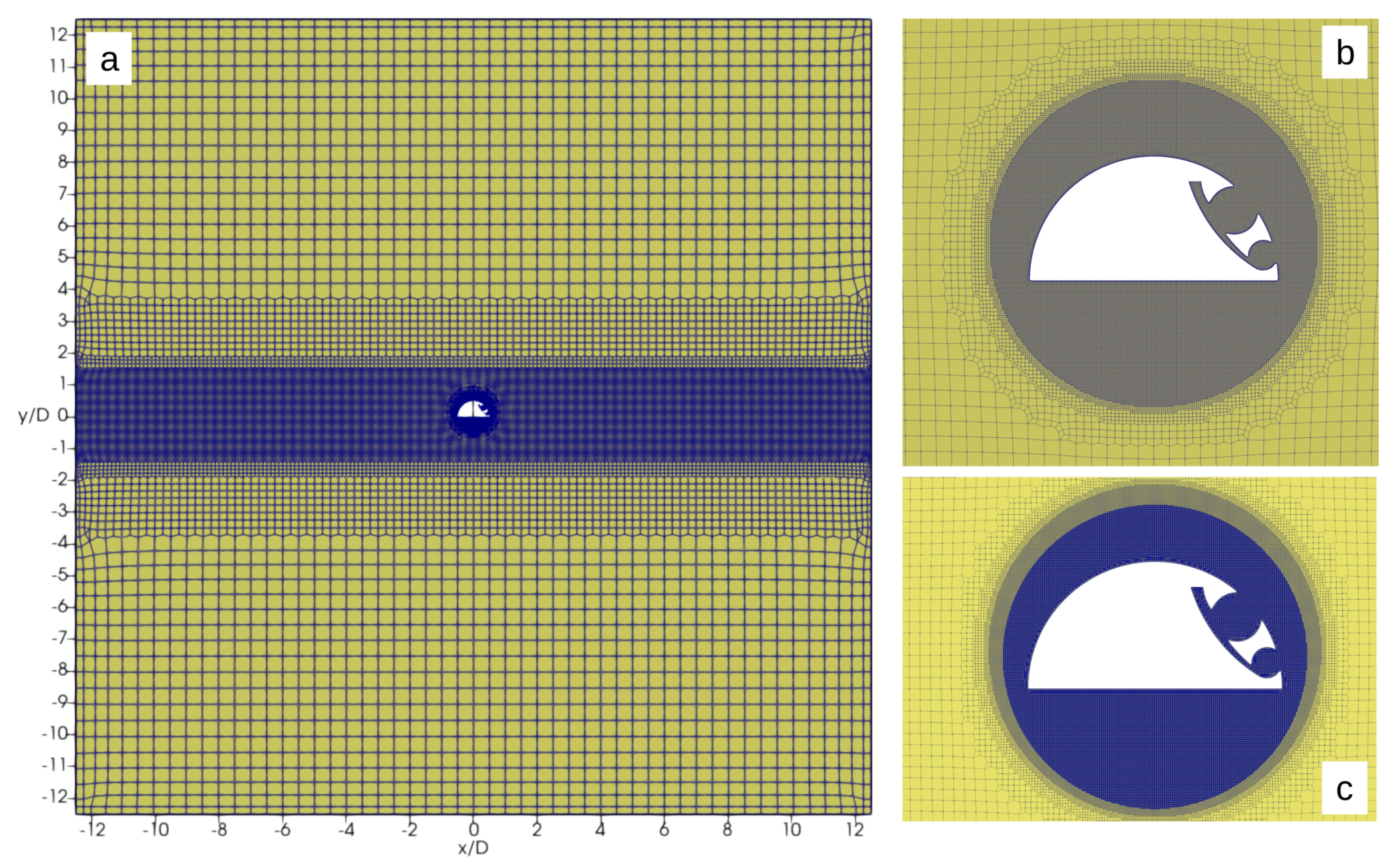

3.2. Computational Grids

3.3. A Near-Wall Modeling Treatment

3.4. Boundary and Initial Conditions

3.5. Critical Remark on RANS Methodology Validation and Verification

- Isaev et al. [36,37] examined the lid-driven cavity flow using an incompressible formulation. The analogy to trapped vortex cells (TVCs) is evident, as the primary vortex core can be considered inviscid with constant vorticity, closely linked to boundary layer development along channel walls. Additionally, assuming a steady-state flow regime is reasonable for moderate to high Reynolds numbers in this configuration.

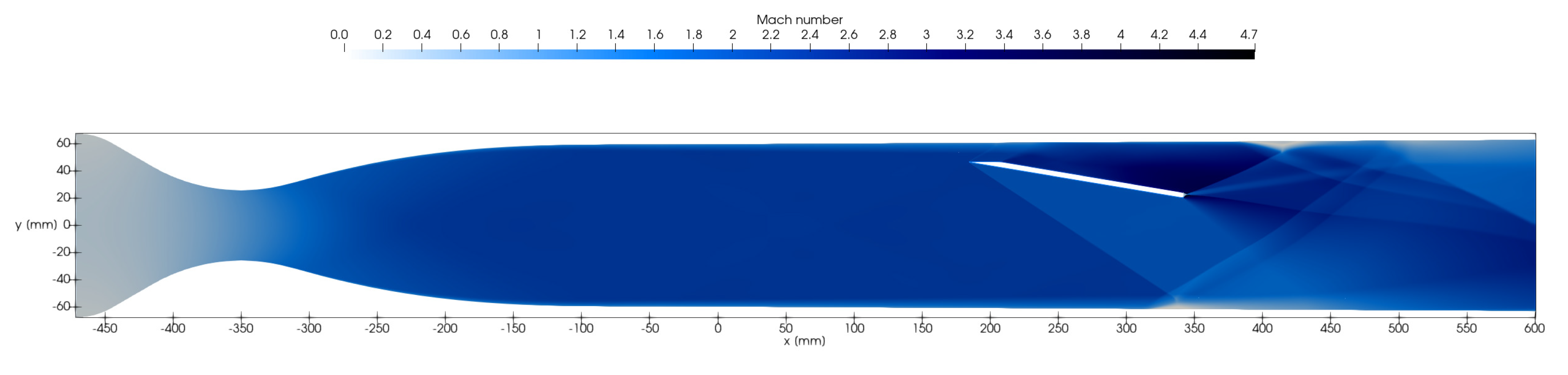

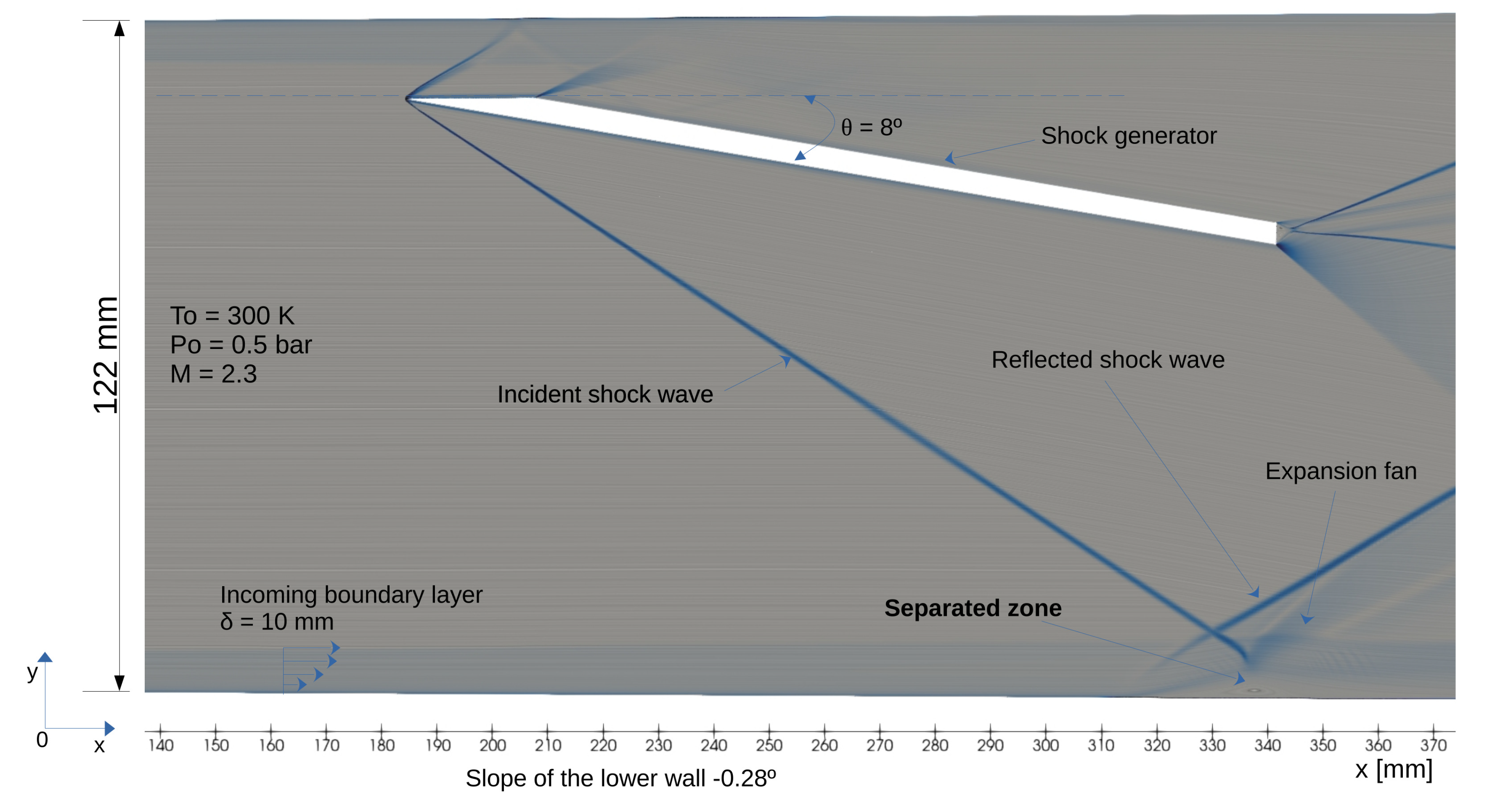

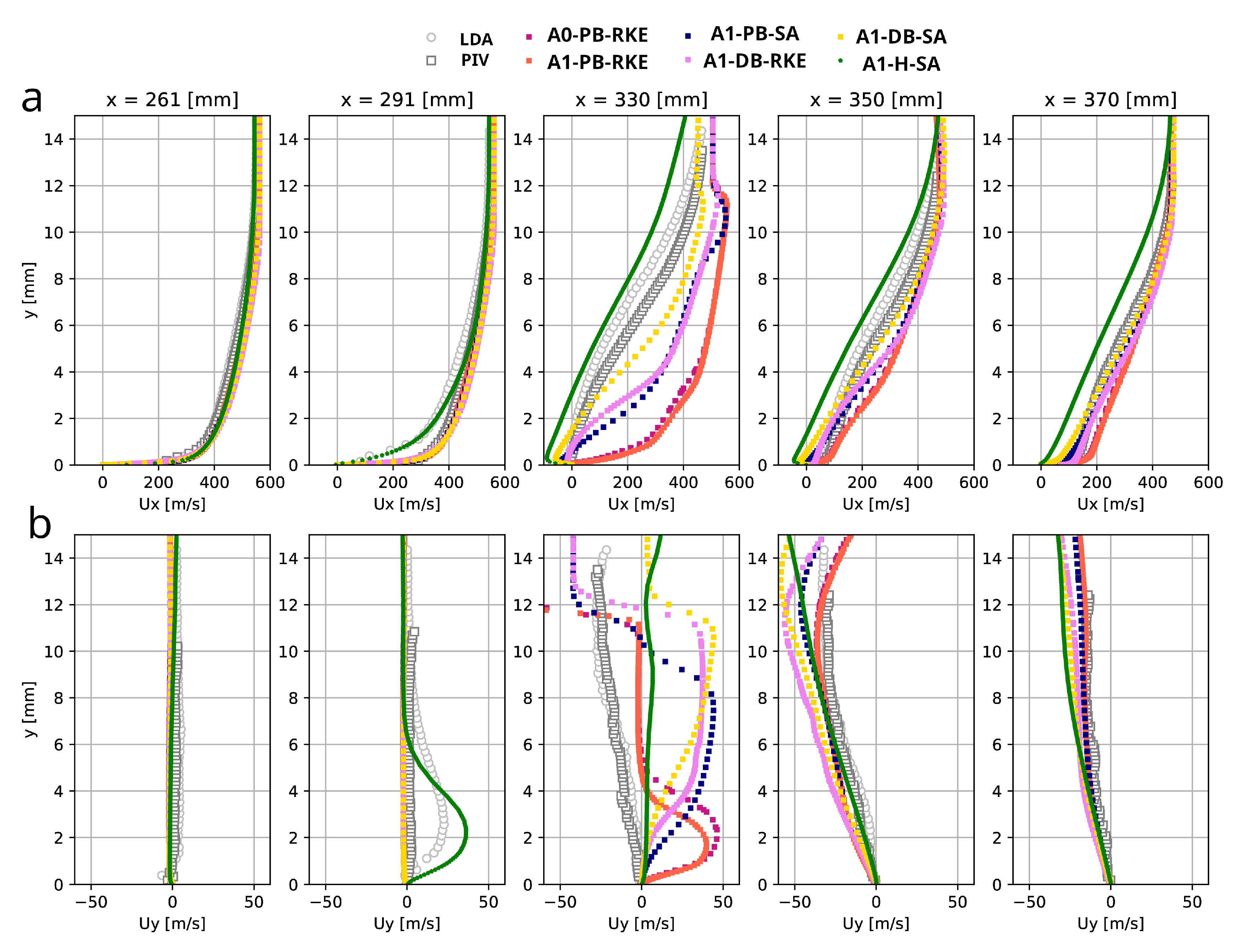

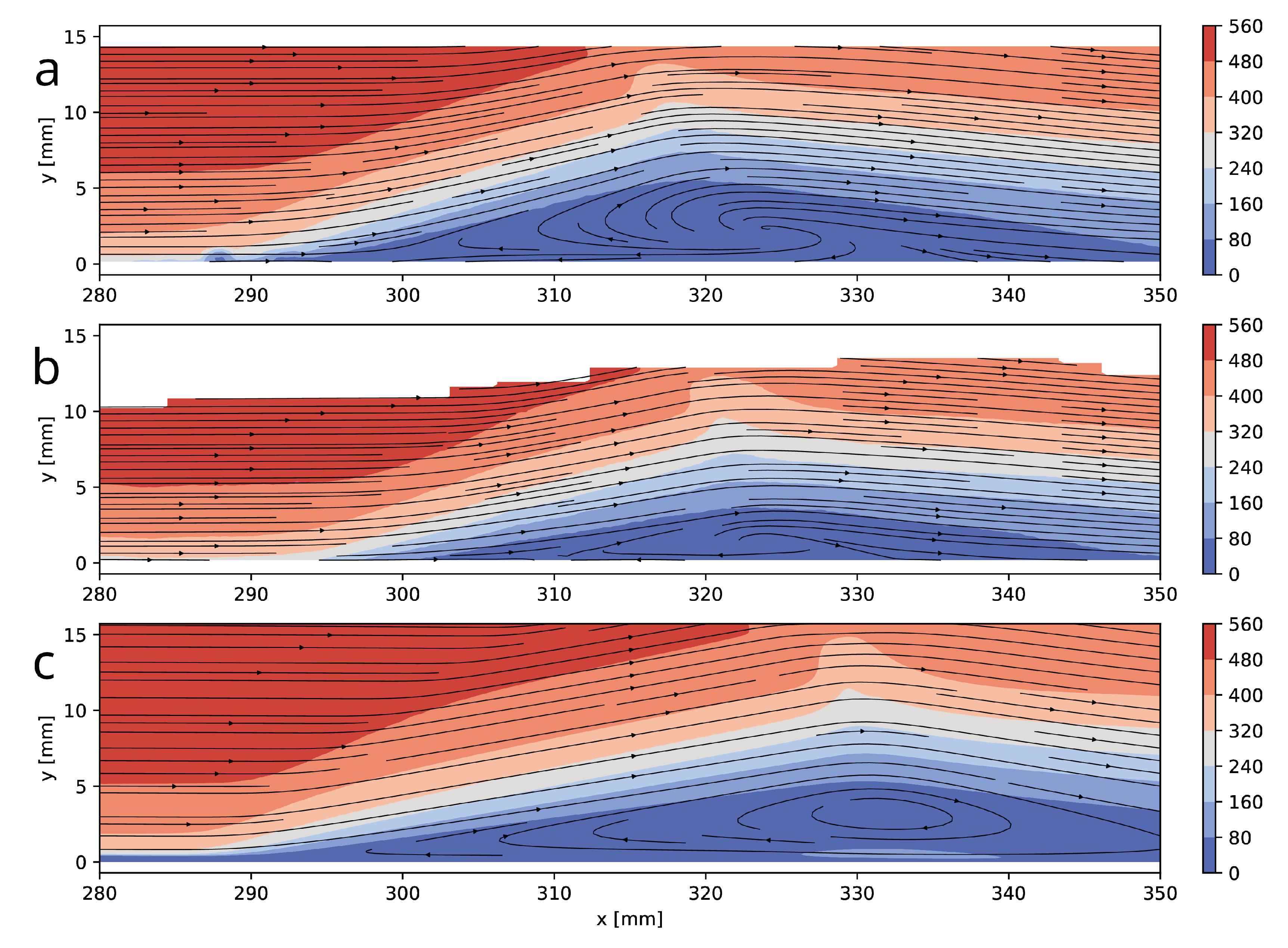

- Shock-boundary layer interaction (SBLI): Verification was performed using the well-documented experiment by Garnier [44], conducted in a supersonic wind tunnel at a nominal Mach number of . An oblique shock is generated by a deflector mounted on the upper wall of the tunnel at a flow deflection angle of , which reflects off the lower wall. At this deflection angle, boundary layer separation is observed.

4. Results

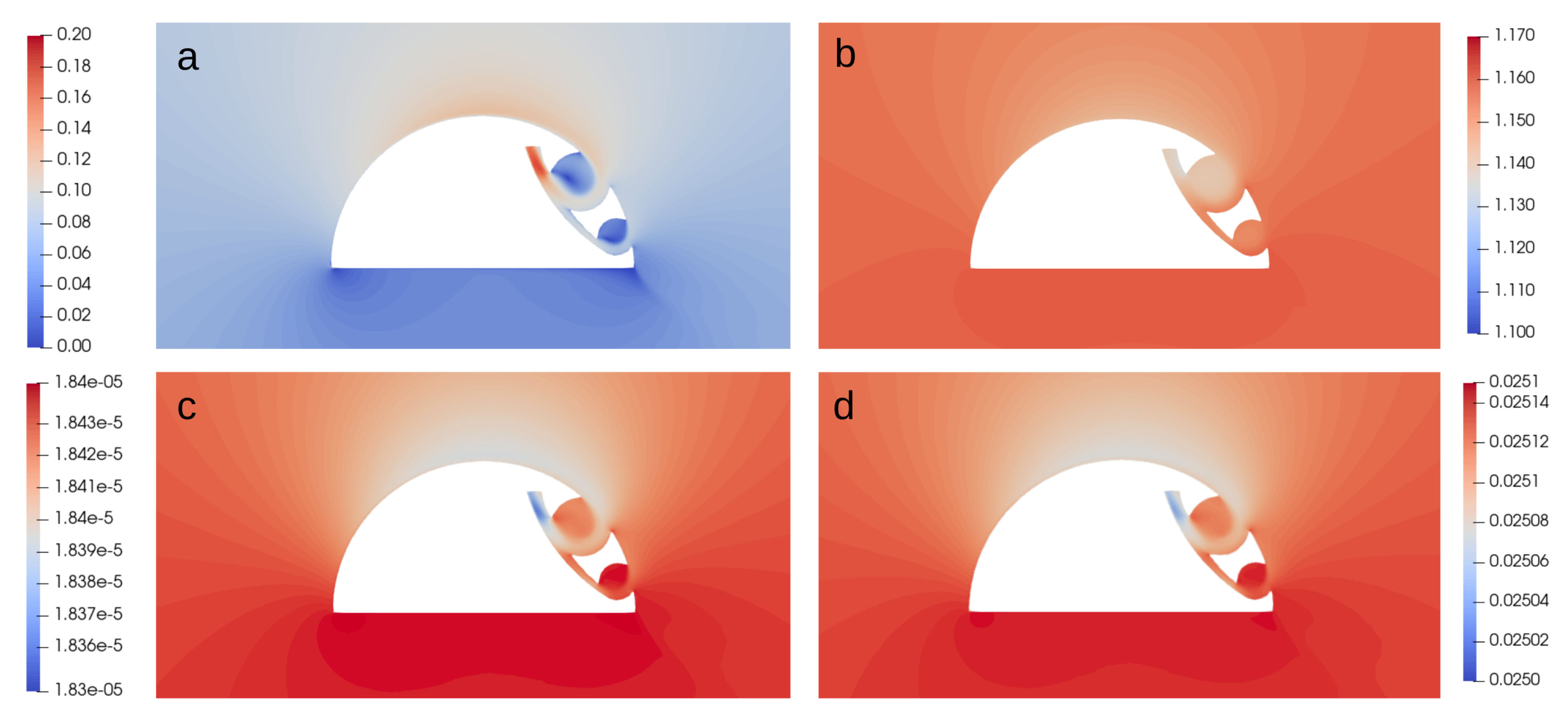

4.1. Critical Remark on modeling Aspects of Thermodynamical Properties

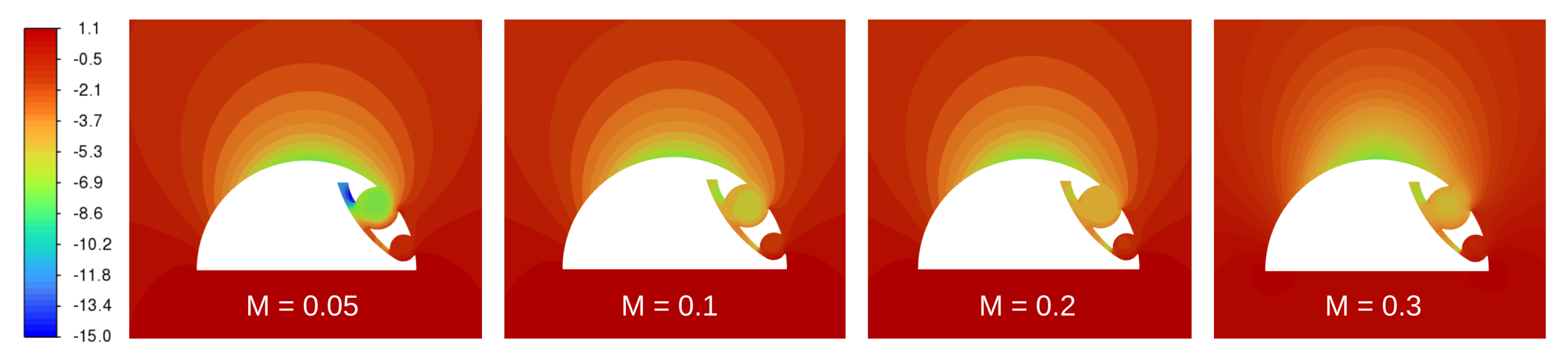

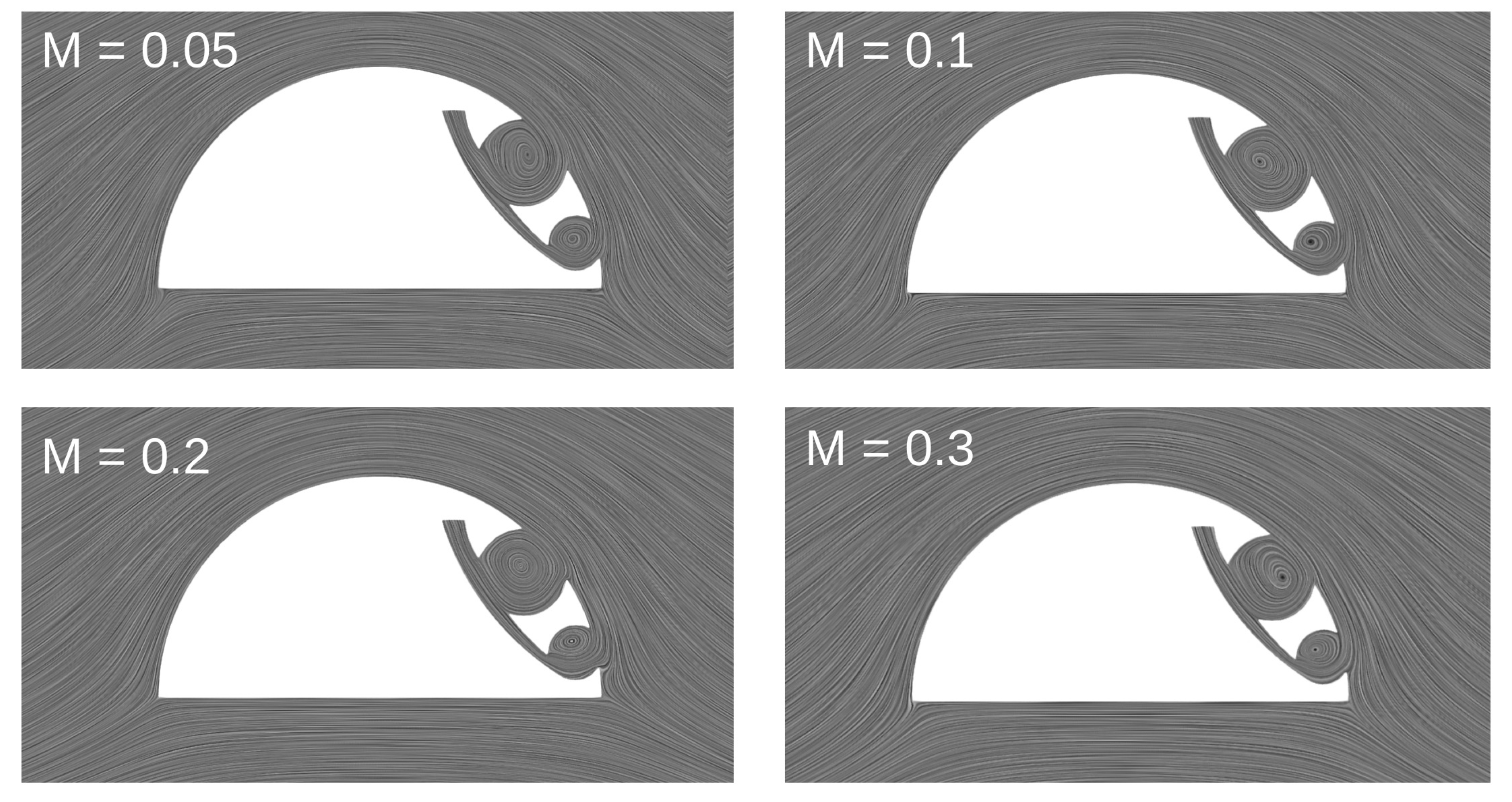

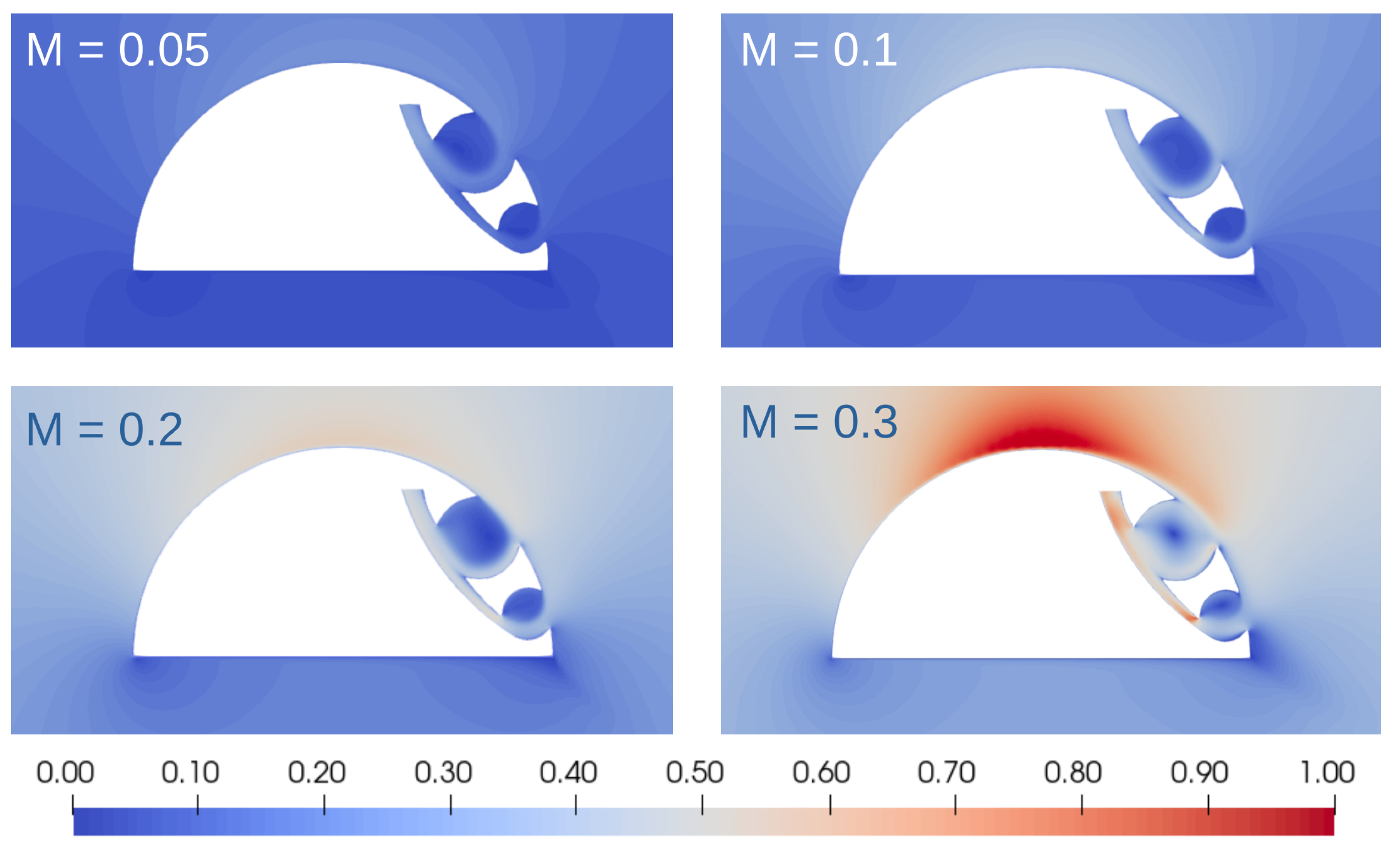

4.2. Effects of the Mach Number

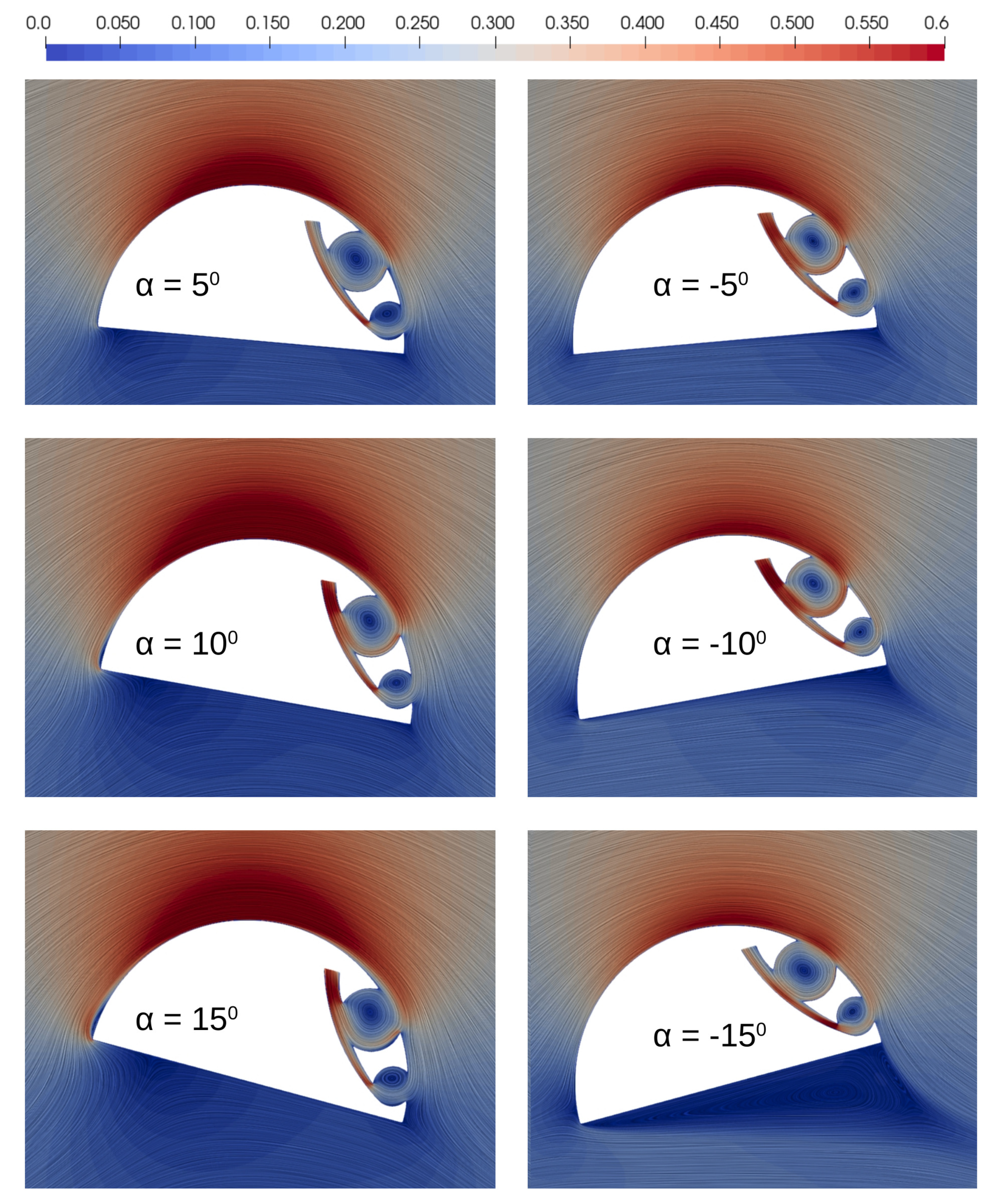

4.3. Effects of Angle of Attack

5. Discussion

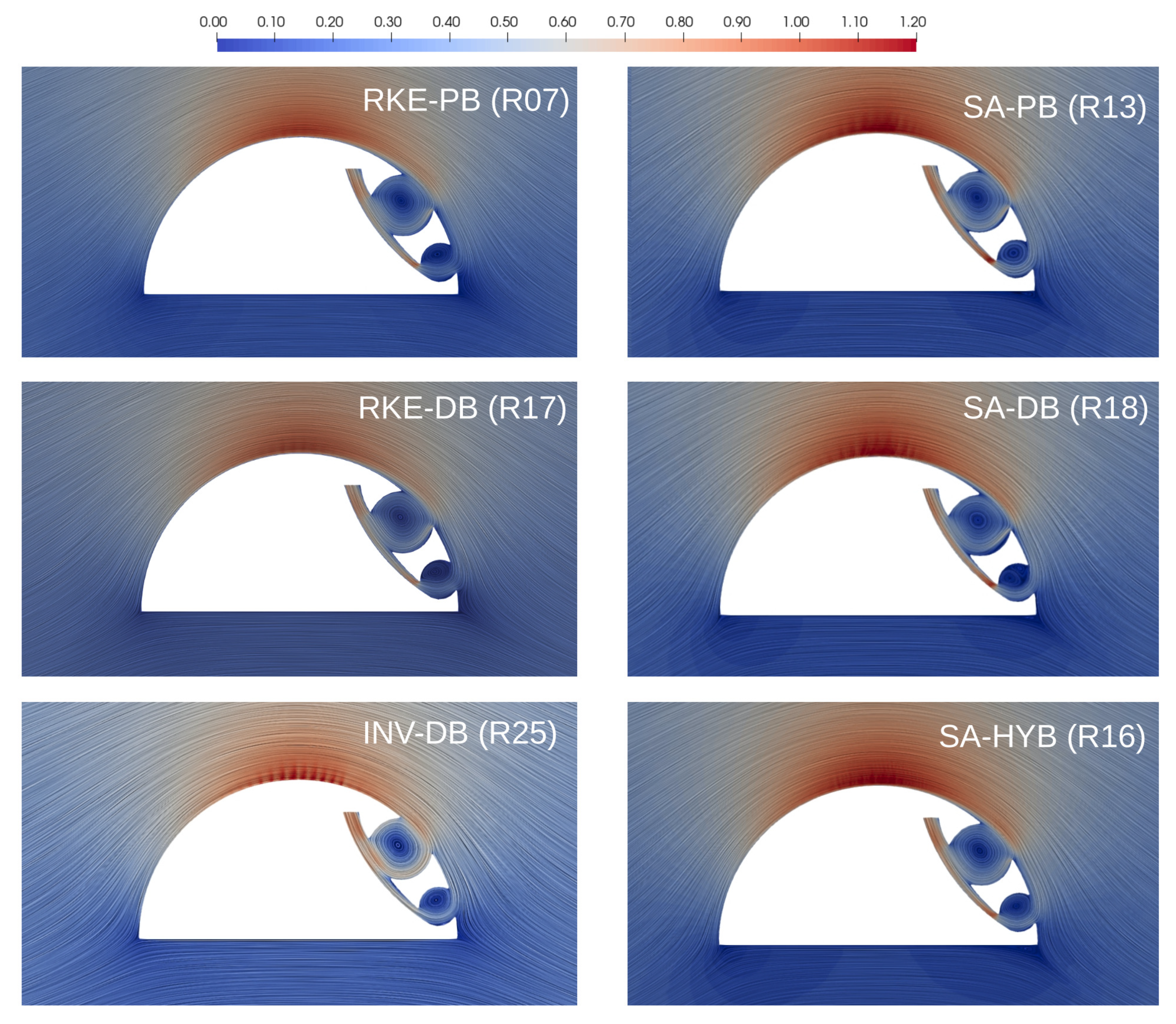

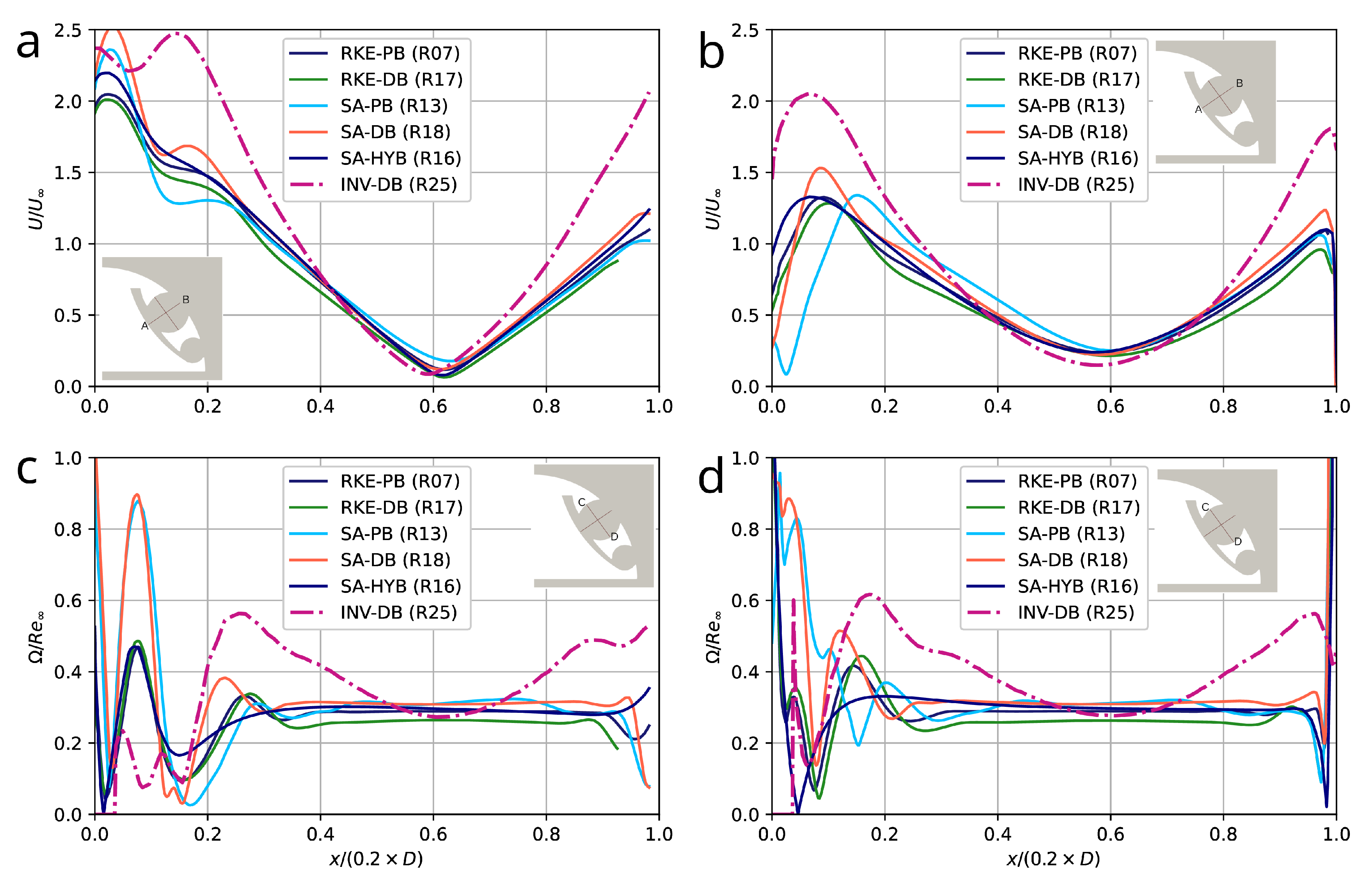

5.1. Impact of Numerical Methods and Turbulence Models

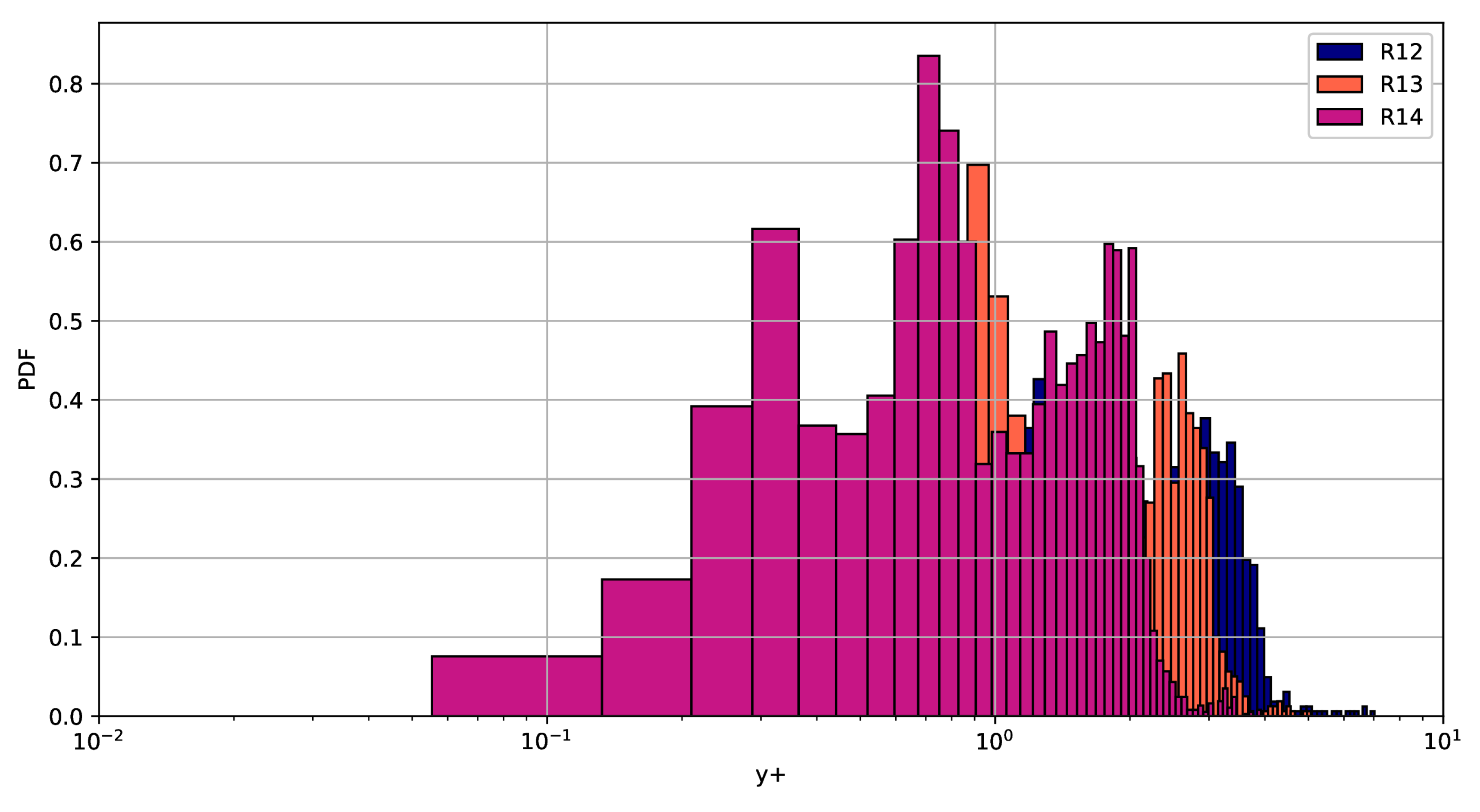

5.2. Remark on the Grid Independence Study

5.3. Comparison of Present Results with an Alternative Configuration

6. Conclusions

- Further validation of the large-eddy simulations for flow regimes at Mach numbers of and ;

- Preliminary conceptual design of an aircraft featuring aerodynamic boundary layer control, integrating the fuselage with the thick airfoil (bluff-body) and AFC system.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADCs | Aerodynamic characteristics |

| AF | Ansys Fluent |

| AFC | Aerodynamic Flow Control |

| AMG | Algebraic Multigrid Method |

| AUSM | Advection Upstream Splitting Method |

| BB | Bluff-Body |

| BDF | Backward Differencing Formula |

| CC | Circular Cylinder |

| CDS | Central Differencing Scheme |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CFL | Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy |

| ERCOFTAC | European Research Community on Flow, Turbulence and Combustion |

| FVM | Finite Volume Method |

| GAMG | Geometric Multigrid Method |

| HC | Semi-circular Cylinder |

| KNP | Kurganov-Noelle-Petrova |

| LDV | Laser Doppler Velocimetry |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| LIC | Line Integral Convolution |

| LU | Lower unitriangular and Upper triangular |

| OF | OpenFOAM |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PBiCGStab | Stabilized Preconditioned (Bi)-Conjugate Gradients Method |

| Probability Density Distribution | |

| PIMPLE | PISO Merged with SIMPLE |

| PISO | Pressure-Implicit with Splitting of Operators |

| PIV | Particle Image Velocimetry |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes |

| RKE | Realizable k- |

| SA | Spalart-Allmaras |

| SBLI | Shock Wave/Boundary Layer Interaction |

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations |

| SOU | Second-order Upwind Scheme |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport |

| TVC | Trapped Vortex Cell |

| TVD | Total Variation Diminishing |

| VP2/3 | Velocity-Pressure 2D/3D |

Appendix A. Turbulent Shock Wave/Boundary Layer Interaction

Appendix A.1. Brief Description of the Wind Tunnel and Experimental Conditions

Appendix A.2. Brief Description of the Computational Grids, Boundary Condition and Run Matrix for Numerical Exercises

| id | Method | Mesh | TM |

|---|---|---|---|

| A0-PB-RKE | pressure-based | A0 | RKE |

| A1-PB-RKE | pressure-based | A1 | RKE |

| A1-PB-SA | pressure-based | A0 | SA |

| A1-DB-RKE | density-based | A1 | RKE |

| A1-DB-SA | density-based | A1 | SA |

| A1-H-SA | hybrid | A1 | SA |

Appendix A.3. Results and Discussion

References

- Sedda, S., Sardu, C., Lasagna, D., Iuso, G., Donelli, R.S., Gregorio, F. De., Trapped vortex cell for aeronautical applications: flow analysis through PIV and Wavelet transform tools, 10th Pacific Symposium on Flow Visualization and Image Processing, Naples, Italy (2015).

- Lysenko, D.A., Donskov, M., Ertesvåg, I.S., Large-eddy simulations of the flow past a bluff-body with active flow control based on trapped vortex cells at Re = 50000, Ocean Eng, 280, 114496 (2023).

- Ringleb, F.O., Separation control by trapped vortices. In: Boundary Layer and Flow Control, Ed. Lachmann G.V., Pergamon Press (1961).

- Kasper, W., Aircraft wing with vortex generation, US Patent No. 3831885 (1974).

- Kruppa, E.W., A Wind Tunnel Investigation of the Kasper Vortex Concept, AIAA, 77-310 (1977).

- Savitsky, A.I., Schukin, L.N., Karelin, V.G., Mass, A.M., Pushkin, R.M., Shibamov, A.P., Schukin, I.L., Fischenko, S.V., Method for controlling boundary layer on an aerodynamic surface of a flying vehicle, US Patent No. 5417391 (1995).

- Ermishin, A.V., Isaev, S.A., Flow control past bodies with Vortex Cells applied to a blended wing-body aircraft (Numerical and Physical Modeling)(In Russian). St.Petersburg University of Civil Aviation, Saint-Petersburg, Moscow.

- Donelli, R., Gregorio, F. De, Iannelli, P., Flow separation control by trapped vortex, AIAA 2010-1409 (2010).

- Isaev, S.A., Aerodynamics of thickened bodies with vortex cells (Numerical and Physical Modeling)(In Russian). St.Petersburg Polytechnic University, Saint-Petersburg. (2016).

- Lysenko D.A., On numerical simulations of turbulent flows over a bluff body with aerodynamic flow control based on trapped vortex cells: viscous effects, Fluids. 2025; 10(5):120. [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Donskov, M., Ertesvåg, I.S., Large-eddy simulations of the flow over a semi-circular cylinder at Re = 50000, Comput Fluids, 228 (2021) 10505.

- Chase, M., NIST-JANAF Thermochemical tables, 4th Ed., J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, Monographs and Supplements, 9 (1998).

- McBride, B.J., Zehe, M.J., Gordon, S., NASA Glenn coefficients for calculating thermodynamic properties of individual species. Technical Report NASA/TP-2002-211556, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2002) URL: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20020085330.

- Spalart, P. and S. Allmaras, S., A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows, Technical Report AIAA-92-0439 (1992).

- Shih, T.H., Liou, W., Shabbir, A., Yang, Z., Zhu, J. A new k eddy-viscosity model for high Reynolds number turbulent flows - model development and validation, J Comput Fluids 24(3), 227-38 (1995).

- Dacles-Mariani, J., Zilliac, G.G., Chow, J.S., Bradshaw, P., Numerical/Experimental study of a wingtip vortex in the near field, AIAA Jl, 33(9), 1561-1568 (1995).

- Sarkar, S, Balakrishnan, L., Application of a Reynolds-stress turbulence model to the compressible shear layer, ICASE Report 90-18, NASA CR 182002 (1990).

- ANSYS FLUENT 2021SRb. Theory guide. Tech. rep., Ansys Inc. (2021).

- Weller, H.G., Tabor, G., Jasak, H., Fureby, C., A tensorial approach to computational continuum mechanics using object-oriented techniques, J Comput Phys, 12(6), 620-631 (1998).

- Chorin, A.J., Numerical Solution of the Navier-Stokes Equations, Math Comput., 22(104), 745-762 (1968).

- Issa, R., Solution of the implicitly discretized fluid flow equations by operator splitting, J Comput Phys, 62, 40-65 (1986).

- Geurts, B, Elements of direct and large-eddy simulation, R.T.Edwards, Philadelphia (2004).

- Hutchinson B, Raithby G. A multigrid method based on the additive correction strategy, J Numer Heat Transfer, 9, 511-37 (1986).

- Godunov, S.K., I. Bohachevsky, I., Finite difference method for numerical computation of discontinuous solutions of the equations of fluid dynamics, Matematičeskij sbornik, 47(89) (3), 271-306 (1959).

- Toro, E.F., Riemann Solvers and Numerical Methods for Fluid Dynamics, 3rd Edition, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (2009).

- Liou, M.-S., Steffen, C., A new flux splitting scheme, J Comput Phys, 107, 23-39 (1993).

- Ferziger, J.H., Peric, M., Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamics // 3rd edition, Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Tokyo: Springer, (2002).

- Kurganov, A., Noelle, S., Petrova, G., Semi-discrete central-upwind schemes for hyperbolic conservation laws and Hamilton–Jacobi equations, SIAM J Sci Computing, 23m 707-740 (2001).

- Kraposhin, M., Bovtrikova, A., Strijhak, S., Adaptation of Kurganov-Tadmor numerical scheme for applying in combination with the PISO method in numerical simulation of flows in a wide range of Mach numbers, Procedia Computer Science, 66, 43-52 (2015).

- Van Leer, B., Towards the ultimate conservative difference scheme. II. Monotonicity and conservation combined in a second-order scheme. J Comput Physics, 14, 361-370 (1974).

- Wolfshtein, M., The velocity and temperature distribution of one-dimension flow with turbulence augmentation and pressure gradient, I J Heat Mass Transfer, 12, 301-318 (1969).

- Chen, H.C., Patel, V.C., Near-wall turbulence models for complex flows including separation, AIAA J, 26(6), 641-648 (1988).

- Jongen, T., Simulation and modeling of turbulent incompressible flows, PjD thesis, EPF Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland (1992).

- Menter, F., Ferreira, J.C., Esch, T., Konno, B., The SST turbulence model with improved wall treatment for heat transfer predictions in gas turbines. Proceedings of the International Gas Turbine Congress, 2-7 (2003).

- Lysenko, D.A. Large-eddy simulation of the flow past a circular cylinder at Re = 130,000: Effects of numerical platforms and single- and double-precision arithmetic, Fluids, 10, 4 (2025).

- Isaev, S.A., Baranov, P.A., Kudryavtsev, N.A., Lysenko, D.A., Usachov, A.E., Complex analysis of turbulence models, algorithms, and grid structures at the computation of recirculating flow in a cavity by means of VP2/3 and FLUENT packages. Part 2. Estimation of models adequacy, Thermophysics and Aeromechanics, 13(1), 55-65 (2006).

- Isaev, S.A., Baranov, P.A., Kudryavtsev, N.A., Lysenko, D.A., Usachov, A.E., Complex analysis of turbulence models, algorithms, and grid structures at the computation of recirculating flow in a cavity by means of VP2/3 and FLUENT packages. Part 1. Scheme factors influence, Thermophysics and Aeromechanics, 12(4), 549-569 (2005).

- Isaev, S.A., Baranov, P.A., Kudryavtsev, N.A., Lysenko, D.A., Usachov, A.E., Comparative analysis of the calculation data on an unsteady flow around a circular cylinder obtained using the VP2/3 and FLUENT packages and the Spalart-Allmaras and Menter turbulence models, J Engineering Physics and Thermophysics, 78(6), 1199-1213 (2005).

- Isaev S , Baranov P , Popov I , Sudakov A , Usachov A , Guvernyuk S , et al. Numerical simulation and experiments on turbulent air flow around the semi-circular profile at zero angle of attack and moderate Reynolds number, Comput Fluids, 188:1-17 (2019).

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Modeling of turbulent separated flows using OpenFOAM, Comput. Fluids, 80, 408-422 (2013).

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Towards simulation of far-field aerodynamic sound from a circular cylinder using OpenFOAM, I J Aeroacoustics, 13(1), 141-168 (2014).

- Isaev, S.A. and Lysenko, D.A., Testing of the FLUENT package in calculation of supersonic flow in a step channel, J Engineering Physics and Thermophysics, 78(4), 857-860 (2004).

- Isaev, S.A. and Lysenko, D.A., Testing of numerical methods, convective schemes, algorithms for approximation of flows, and grid structures by the example of a supersonic flow in a step-shaped channel with the use of the CFX and FLUENT packages, J Engineering Physics and Thermophysics, 82(2) 321-326 (2009).

- Garnier, E., Stimulated detached eddy simulation of three-dimensional shock/boundary layer interaction, Shock Waves 19(6), 479-486 (2009).

- Lysenko, D.A. and Isaev, S.A., Calculation of unsteady flow past a cube on the wall of a narrow channel using URANS and the Spalart-Allmaras turbulence model, J Engineering Physics and Thermophysics, 82(3) 488-495 (2009).

- Isaev, S.A., Nikushchenko, D.V., Sudakov, A.G., Yunakov, L.P., Tryaskin, N.V., Control of subsonic flow around a semicircular airfoil with the use of slot suction in vortex cells, J Eng Physics Thermophysics, 98(5) (2025).

- Isaev, S., Nikushchenko, D., Sudakov, A., Tryaskin, N., Egorova, A., Iunakov, L., Usachov, A., Kharchenko, V., Standard and modified SST models with the consideration of the streamline curvature for separated flow calculation in a narrow channel with a conical dimple on the heated wall, Energies, 14, 5038, 1-23 (2021).

- Dussauge J.P., Piponniau S., Shock boundary layer interactions: possible sources of unsteadiness, J Fluids Structures, 24(8), 1166-75 (2008 ).

- The ERCOFTAC Knowledge Base Wiki, https://www.kbwiki.ercoftac.org/w/index.php?title=Abstr:UFR_3-32.

| h [m] | [kg/m3] | [Pa] | [K] | [m/s] | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.16 | 100,000 | 300 | 17 | 0.05 |

| 1,000 | 1.14 | 89,800 | 281 | 35 | 0.1 |

| 5,000 | 0.74 | 54,500 | 255 | 65 | 0.2 |

| 10,000 | 0.42 | 26,500 | 222 | 90 | 0.3 |

| Run | G | NM | TM | M | [kPa] | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFC-RANS-A1 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.05 | 0.82 | 4.86 | 6.00 | -2 | [10] | |

| R00 | A0 | PB | RKE | 0.05 | 0.56 | 5.72 | 10 | -2 | ||

| R01 | A0 | PB | RKE | 0.1 | 0.29 | 5.79 | 20 | -4 | ||

| R02 | A0 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.25 | 5.89 | 24 | -8 | ||

| R03 | A0 | PB | RKE | 0.3 | 0.26 | 5.72 | 22 | -10 | ||

| R04 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.05 | 0.57 | 5.67 | 10 | -2 | ||

| R05 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.1 | 0.33 | 5.73 | 17 | -4 | ||

| R06 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.26 | 5.89 | 23 | -8 | ||

| R07 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.3 | 0.26 | 5.66 | 22 | -10 | ||

| R08 | A2 | PB | RKE | 0.3 | 0.25 | 5.66 | 23 | -10 | ||

| R09 | A0 | PB | SA | 0.05 | 0.54 | 5.5 | 10 | -2 | ||

| R10 | A0 | PB | SA | 0.1 | 0.31 | 5.57 | 18 | -4 | ||

| R11 | A0 | PB | SA | 0.2 | 0.25 | 5.96 | 24 | -8 | ||

| R12 | A0 | PB | SA | 0.3 | 0.28 | 6.29 | 23 | -10 | ||

| R13 | A1 | PB | SA | 0.3 | 0.27 | 6.21 | 23 | -10 | ||

| R14 | A2 | PB | SA | 0.3 | 0.26 | 6.2 | 24 | -10 | ||

| R15 | A0 | HB | SA | 0.3 | 0.28 | 6.27 | 23 | -10 | ||

| R16 | A1 | HB | SA | 0.3 | 0.27 | 6.34 | 24 | -10 | ||

| R17 | A1 | DB | RKE | 0.3 | 0.25 | 5.59 | 22 | -10 | ||

| R18 | A1 | DB | SA | 0.3 | 0.24 | 6.17 | 28 | -10 | ||

| R19 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.18 | 4.82 | 27 | -11 | ||

| R20 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.24 | 4.83 | 20 | -11 | ||

| R21 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.29 | 5.39 | 19 | -11 | ||

| R22 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.19 | 6.64 | 35 | -10 | ||

| R23 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.29 | 7.48 | 26 | -10 | ||

| R24 | A1 | PB | RKE | 0.2 | 0.31 | 7.57 | 24 | -10 | ||

| R25 | A1 | DB | INV | 0.3 | 0.31 | 5.32 | 17 | -10 | ||

| VP2/3 | SST | 0.01 | 0.44 | 4.9 | 11 | [46] | ||||

| VP2/3 | SST | 0.1 | 0.43 | 4.96 | 12 | [46] | ||||

| VP2/3 | SST | 0.2 | 0.39 | 5.16 | 13 | [46] | ||||

| VP2/3 | SST | 0.3 | 0.22 | 2.22 | 10 | [46] |

| Run | Mesh | TM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R06 | A0 | RKE | 2.36 | 0.31 |

| R07 | A1 | RKE | 1.78 | 0.30 |

| R08 | A2 | RKE | 1.31 | 0.29 |

| R12 | A0 | SA | 2.14 | 0.31 |

| R13 | A1 | SA | 1.65 | 0.29 |

| R14 | A2 | SA | 1.17 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).