Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Result and Discussion

2. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Kresge, C.; Leonowicz, M.; Roth, W.; Vartuli, J.; Beck, J. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid crystal template mechanism. Nature 1992, 359, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazov, M.; Davis, M. ; Catalysis by framework zinc in silica-based molecular sieves. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhou, W.; Li, H.; Ren, L.; Qiao, P.; Li, W.; Fu, H. Synthesis of Particulate Hierarchical Tandem Heterojunctions toward Optimized Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1804282−1804290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.; Pang, S.; Jones, C. Adsorption Micro-calorimetry of CO2 in Confined Amino polymers. Langmuir 2017, 33, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, C.; Jaroniec, M. ; Mesoporous calcium oxide-silica and magnesium oxide-silica composites for CO2 capture at ambient and elevated temperatures. J. Mat. Chem. A 2016, 4, 10914–10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Yang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, B.; Lv, Y.; Xu, C.; Asiri, A.; Zi, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, D. Dual-Pore Mesoporous Carbon@Silica Composite Core−Shell Nanospheres for Multidrug Delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 126, 5470−5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zink, J. Probing the Local Nanoscale Heating Mechanism of a Magnetic Core in Mesoporous Silica Drug-Delivery Nanoparticles Using Fluorescence Depolarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5212–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, D.; Chen, G.; Elzatahry, A.; Pal, M.; Zhu, H.; Wu, L.; Lin, J.; Al-Dahyan, D.; Li, W.; Zhao, D. Mesoporous Silica Thin Membranes with Large Vertical Mesochannels for Nanosize-Based Separation. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Shi, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, S.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, C. Amino-modified hollow mesoporous silica nanospheres-incorporated reverse osmosis membrane with high performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 581, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. Mesoporous Materials for Energy Conversion and Storage Devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16023−16040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kani, K.; Malgras, V.; Jiang, B.; Hossain, M.; Alshehri, S.; Ahamad, T.; Salunkhe, R.; Huang, Z.; Yamauchi, Y. Periodically Arranged Arrays of Dendritic Pt Nanospheres Using Cage-Type Mesoporous Silica as a Hard Template. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirin, D.; Protesescu, L.; Trummer, D.; Kochetygov, I.; Yakunin, S.; Krumeich, F.; Stadie, N.; Kovalenko, M. Harnessing defect-tolerance at the nanoscale: highly luminescent lead halide perovskite nanocrystals in mesoporous silica matrixes. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 5866–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

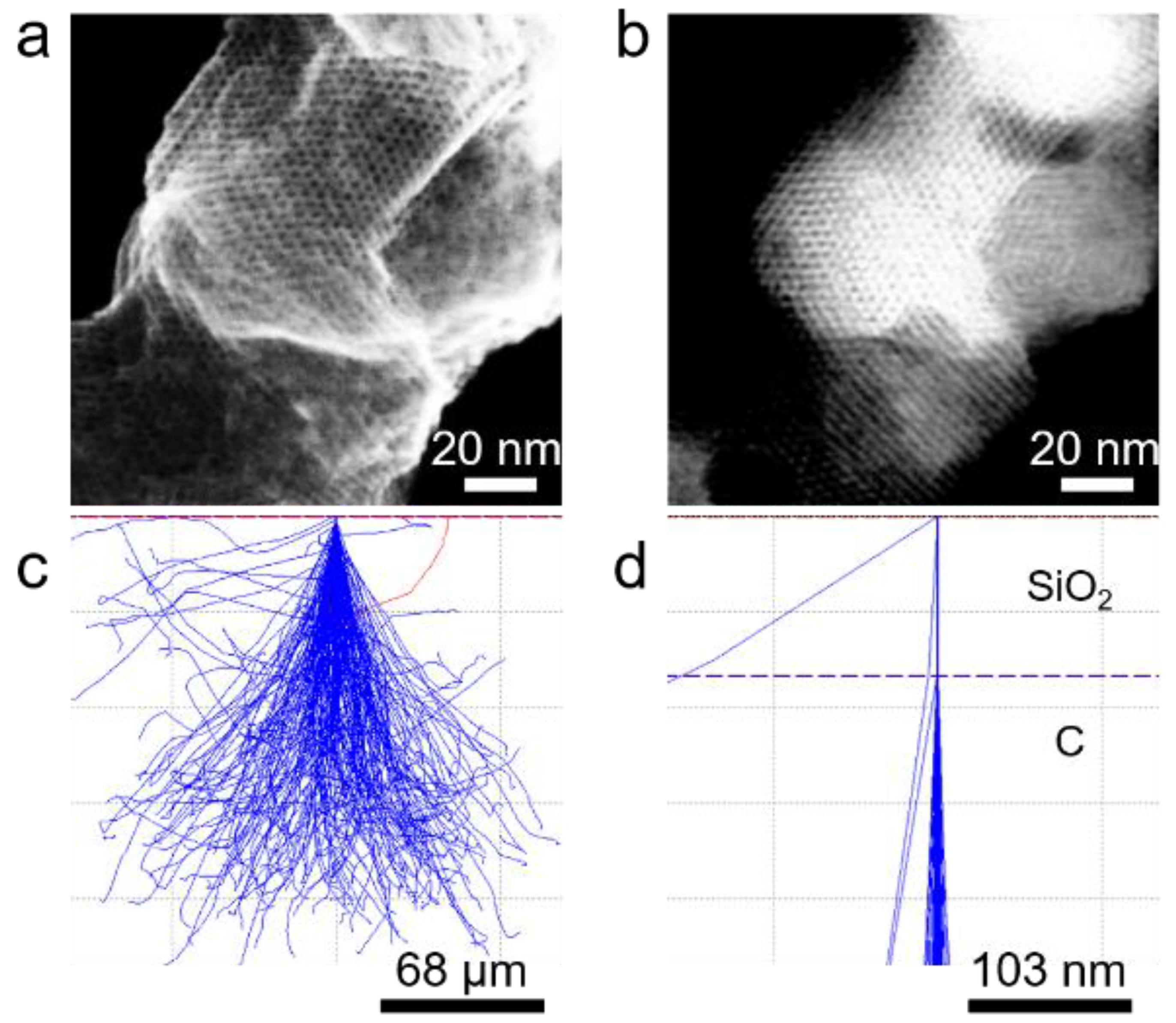

- Carlsson, A.; Kaneda, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Terasaki, O.; Ryoo, R.; Joo, S. The structure of MCM–48 determined by electron crystallography. J. Electron Microsc. 1999, 48, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Kaneda, M.; Terasaki, O.; Zhao, D.; Kim, J.; Stucky, G.; Shin, H.; Ryoo, R. Direct imaging of the pores and cages of three-dimensional mesoporous materials. Nature 2000, 408, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, M.; Tsubakiyama, T.; Carlsson, A.; Sakamoto, Y.; Ohsuna, T.; Terasaki, O.; Joo, S.; Ryoo, R. Structural study of mesoporous MCM-48 and carbon networks synthesized in the spaces of MCM-48 by electron crystallography. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

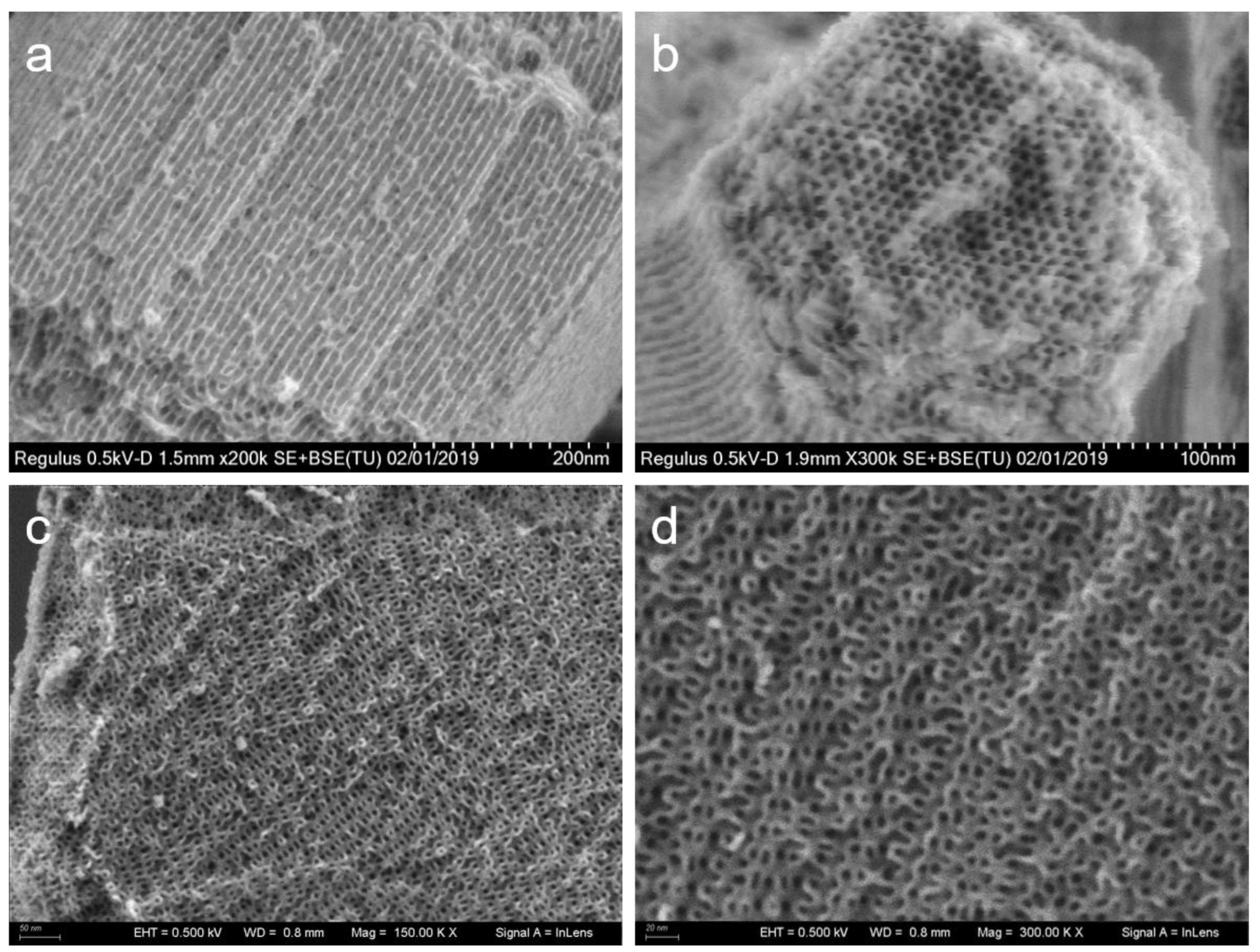

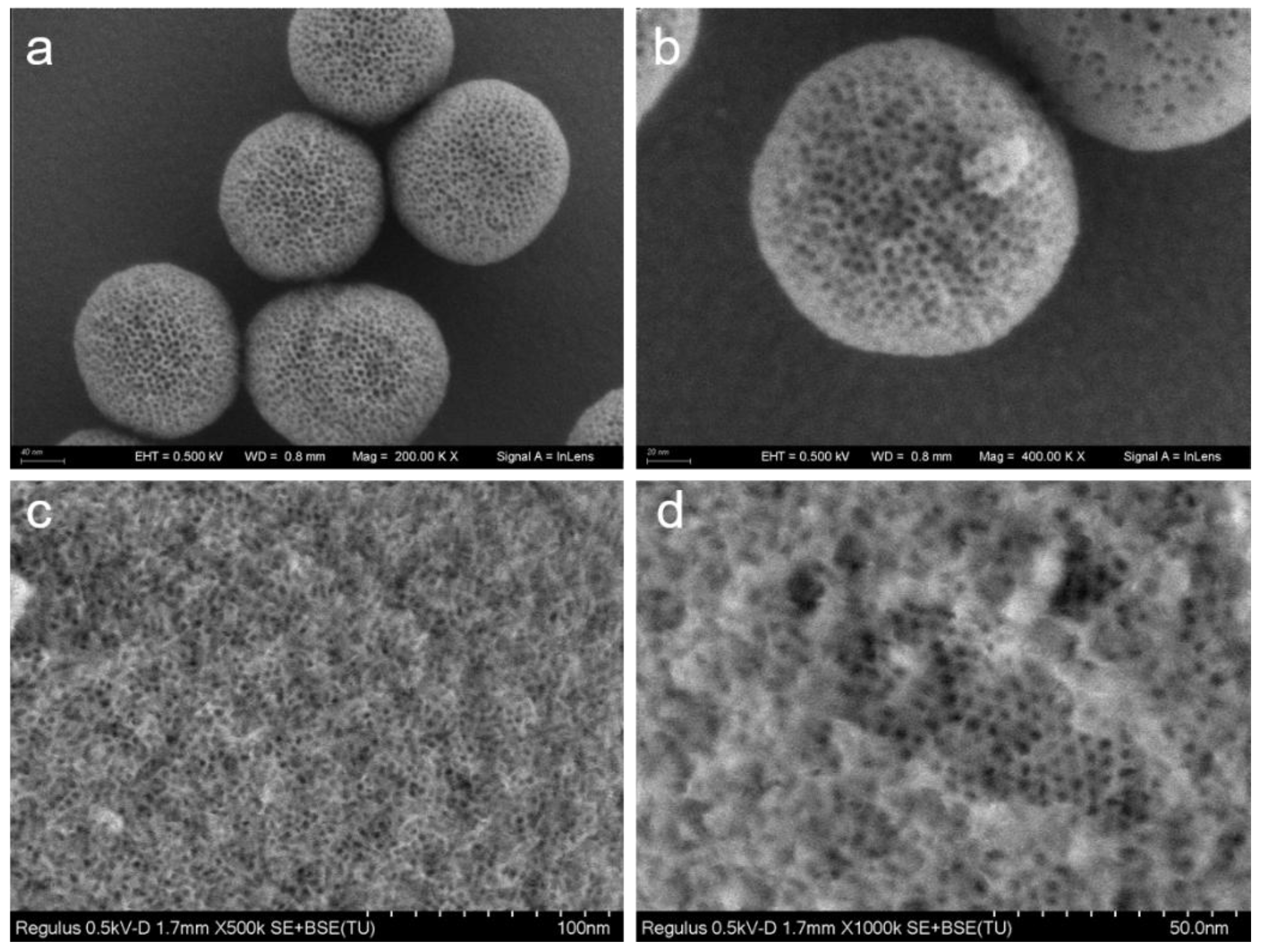

- Asahina, S.; Uno, S.; Suga, M.; Stevens, S.; Klingstedt, M.; Okano, Y.; Kudo, M.; Schüth, F.; Anderson, M.; Adschiri, T.; Terasaki, O. A new HRSEM approach to observe fine structures of novel nanostructured materials. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2011, 146, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cen, X.; Ravichandran, R.; Hughes, L.; Benthem, K. Simultaneous scanning electron microscope imaging of topographical and chemical contrast using in-lens, in-column, and everhart-thornley detector systems. Microscopy and Microanalysis 2016, 22, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, D. Control of charging in low-voltage SEM. Scanning, 1989, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Lund, K.; Tatsumi, T.; Iijima, S.; Joo, S.; Ryoo, R.; Terasaki, O. Direct observation of 3D mesoporous structure by scanning electron microscopy (SEM): SBA-15 silica and CMK-5 carbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 2182–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, D.; Weinberg, G.; Su, D.; Bao, X. Engineered Complex Emulsion System: Toward Modulating the Pore Length and Morphological Architecture of Mesoporous Silicas. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 25908–25915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüysüz, H.; Lehmann, C.; Bongard, H.; Tesche, B.; Schmidt, R.; Schüth, F. Direct Imaging of Surface Topology and Pore System of Ordered Mesoporous Silica (MCM-41, SBA-15, and KIT-6) and Nanocast Metal Oxides by High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11510–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, H.; Su, D.; Egerton, R.; Konno, M.; Wu, L.; Ciston, J.; Wall, J.; Zhu, Y. Atomic imaging using secondary electrons in a scanning transmission electron microscope: Experimental observations and possible mechanisms. Ultramicroscopy 2011, 111, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Grunder, S.; Cordova, K.; Valente, C.; Furukawa, H.; Hmadeh, M.; Gándara, F.; Whalley, A.; Liu, Z.; Asahina, S.; Kazumori, H.; Keeffe, M.; Terasaki, O.; Stoddart, J.; Yaghi, O. Large-Pore Apertures in a Series of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2012, 336, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, R.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, D. Biphase Stratification Approach to Three-Dimensional Dendritic Biodegradable Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayari, A.; Han, B.; Yang, Y. Simple Synthesis Route to Monodispersed SBA-15 Silica Rods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14348–14349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, D.; Bao, X.; Klein-Hoffmann, A.; Weinberg, G.; Su, D.; Schlögl, R. Unusual Mesoporous SBA-15 with Parallel Channels Running along the Short Axis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7440–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Yamada, M.; Kataoka, S.; Sano, T.; Inagi, Y.; Miyaki, A. Direct observation of surface structure of mesoporous silica with low acceleration voltage FE-SEM. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects. 2010, 357, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, S.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kawai, A.; Yamada, M.; Kamimura, Y.; Endo, A. Controlled Formation of Silica Structures Using Siloxane/Block Copolymer Complexes Prepared in Various Solvent Mixtures. Langmuir, 2013, 29, 13562–13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, X.; Yao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, W.; Wu, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X. Zhao, D. Conformal Coating of Co/N-Doped Carbon Layers into Mesoporous Silica for Highly Efficient Catalytic Dehydrogenation-Hydrogenation Tandem Reactions. Small, 2017, 13, 1702243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suga, M.; Asahina, S.; Sakuda, Y.; Kazumori, H.; Nishiyama, H.; Nokuo, T.; Alfredsson, V.; Kjellman, T.; Stevens, S.; Cho, H.; Cho, M.; Han, Lu.; Che, S.; Anderson, M.; Schüth, F.; Deng, H.; Yaghi, O.; Liu, Z.; Jeong, H.; Stein, A.; Sakamoto, K.; Ryoo, R.; Terasaki, O. Recent progress in scanning electron microscopy for the characterization of fine structural details of nano materials. Progress in Solid State Chemistry, 2014, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Xu, F.; Shi, J. Combining scanning electron microscopy and fast Fourier transform for characterizing mesopore and defect structures in mesoporous materials. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2016, 220, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | SBET m2g−1 | VT cm3g−1 | pore size nm | d(100) nm | wall thickness nm |

| SBA-15 | 757 | 0.958442 | 6.67 | 9.78 | 4.29 |

| KIT-6 | 499 | 1.18 | 6.64 | 9.84 | 2.75 |

| MSNSs | 575 | 0.45371 | 3.16 | 5.27 | 2.93 |

| MCM-41 | 1164 | 0.546457 | 2.00 | 3.74 | 1.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).