Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

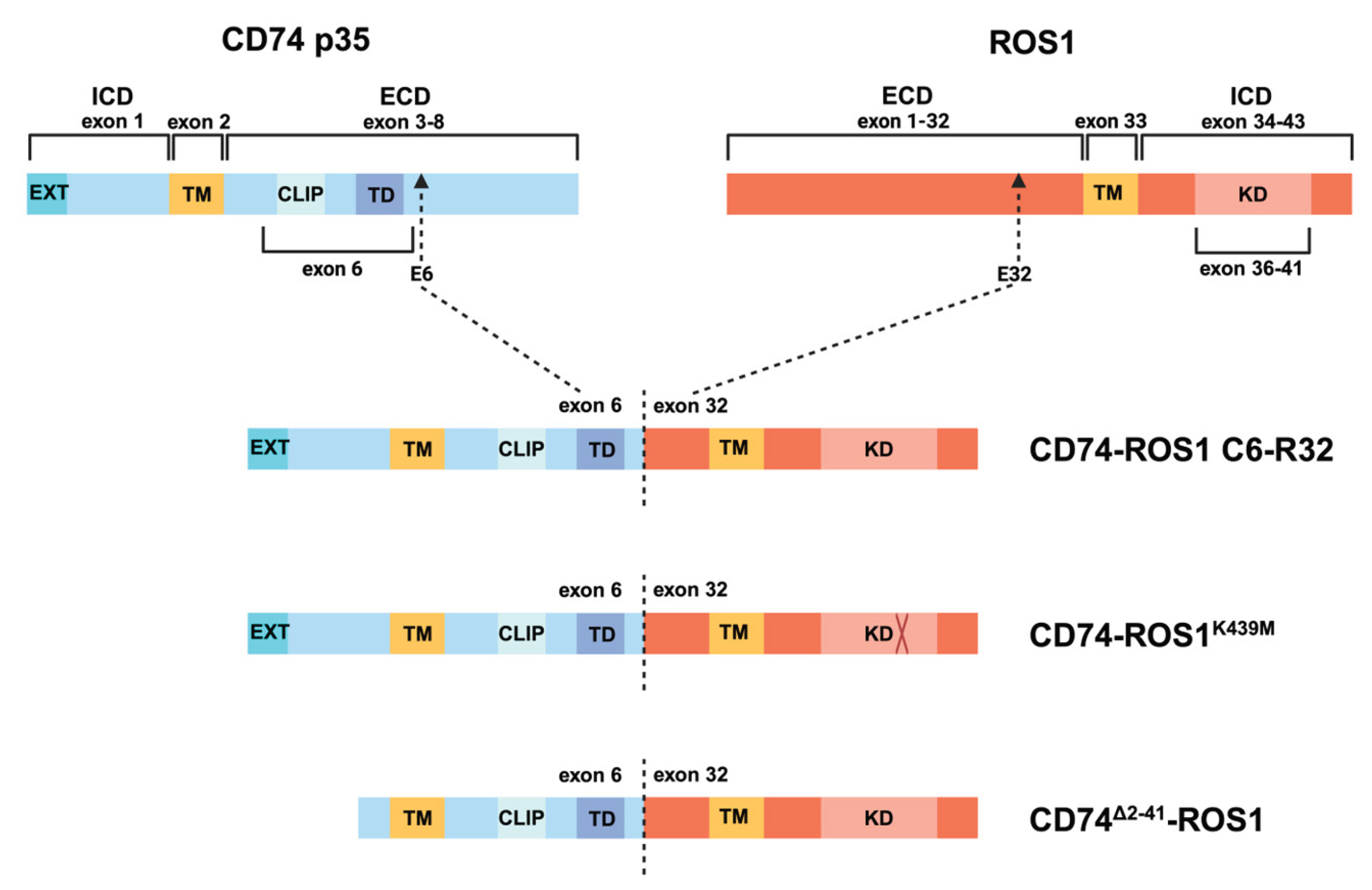

2.1. Justification for the Generation of CD74-ROS1K439M and CD74∆2-41-ROS1 Variants

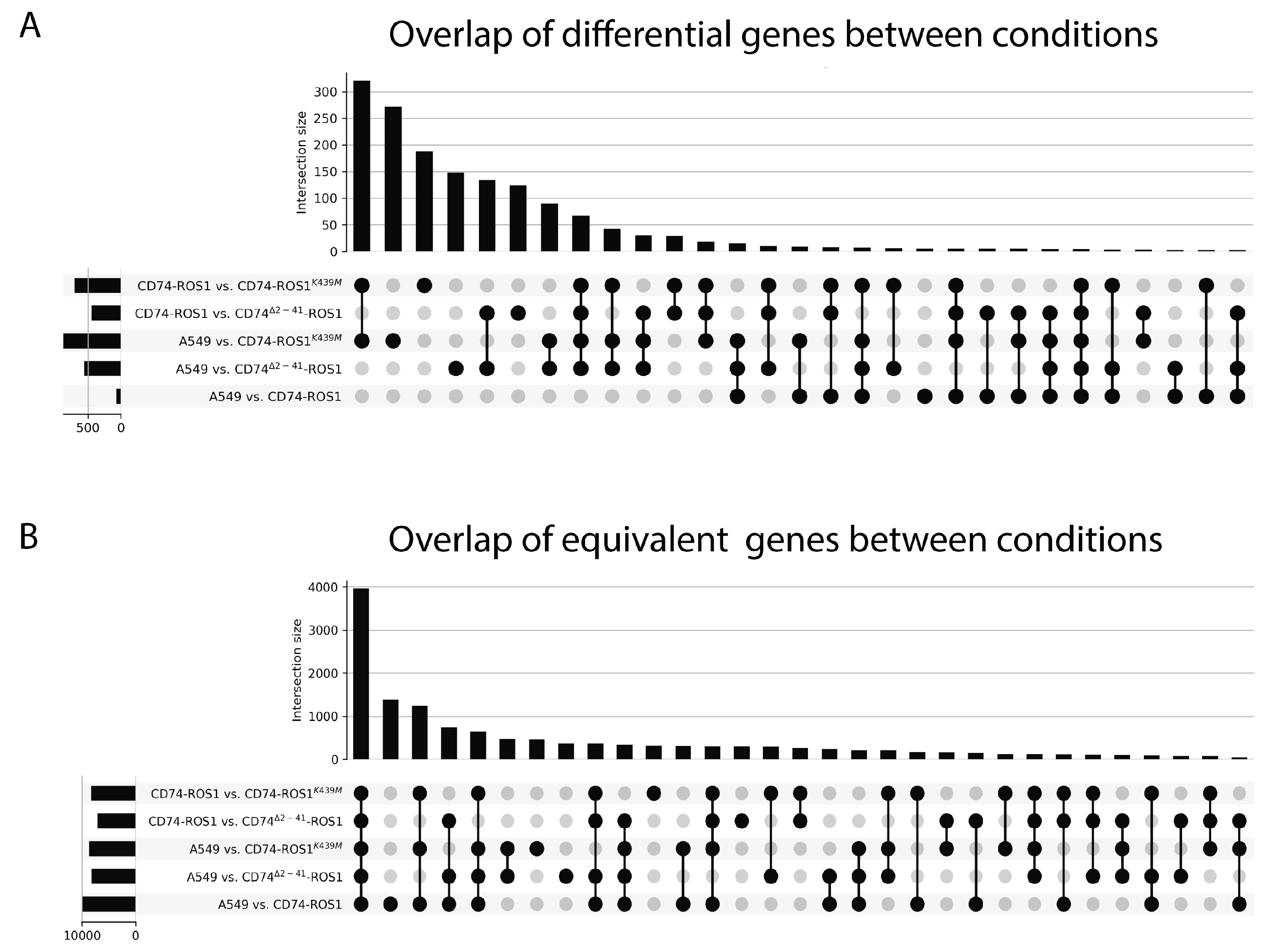

2.2. Global Analysis of the Differential and Equivalent Gene Expression Between A549 and CD74-ROS1 Variants

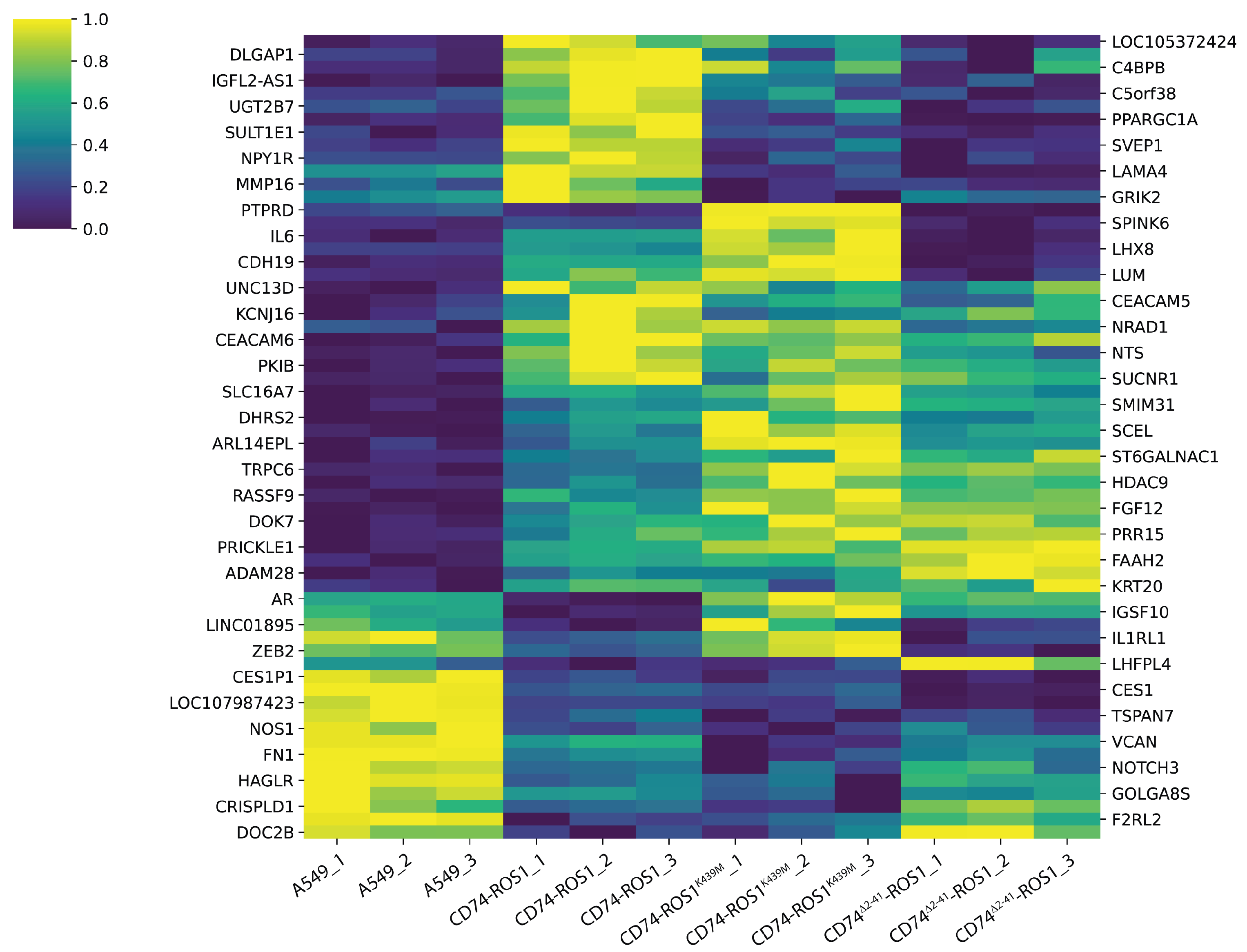

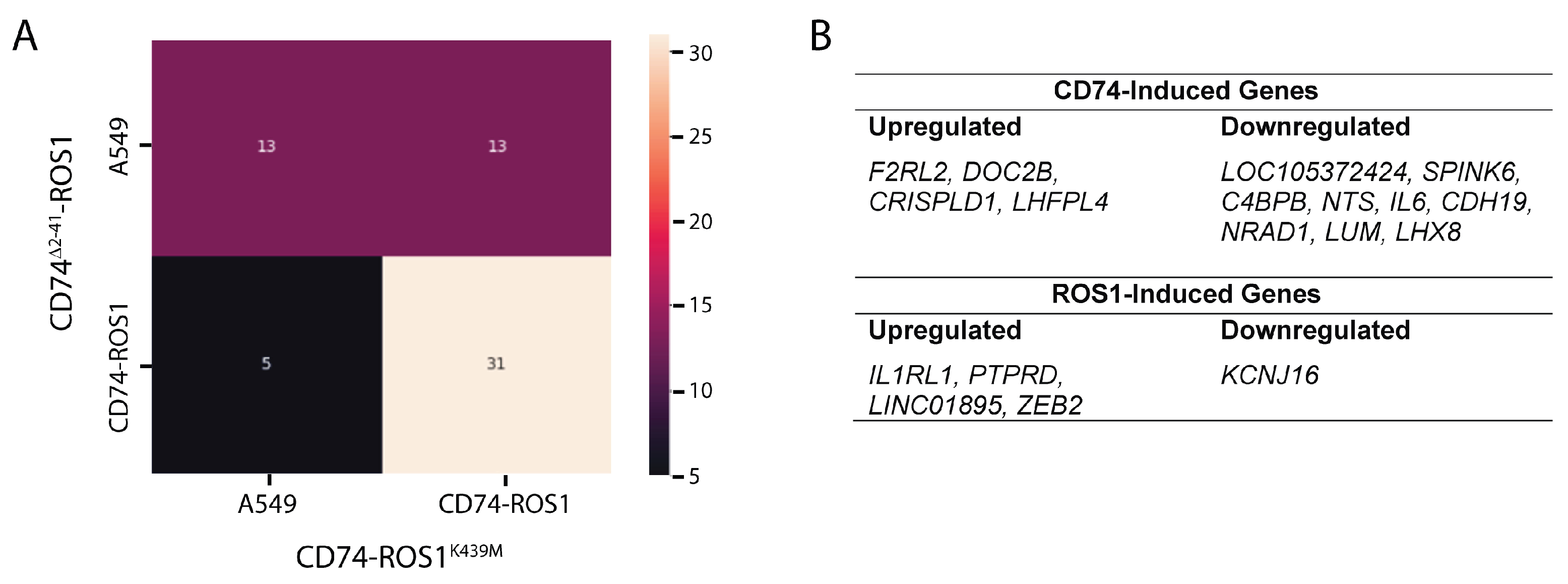

2.3. Multigroup Analysis of the 62 Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Across the Fusion Variants

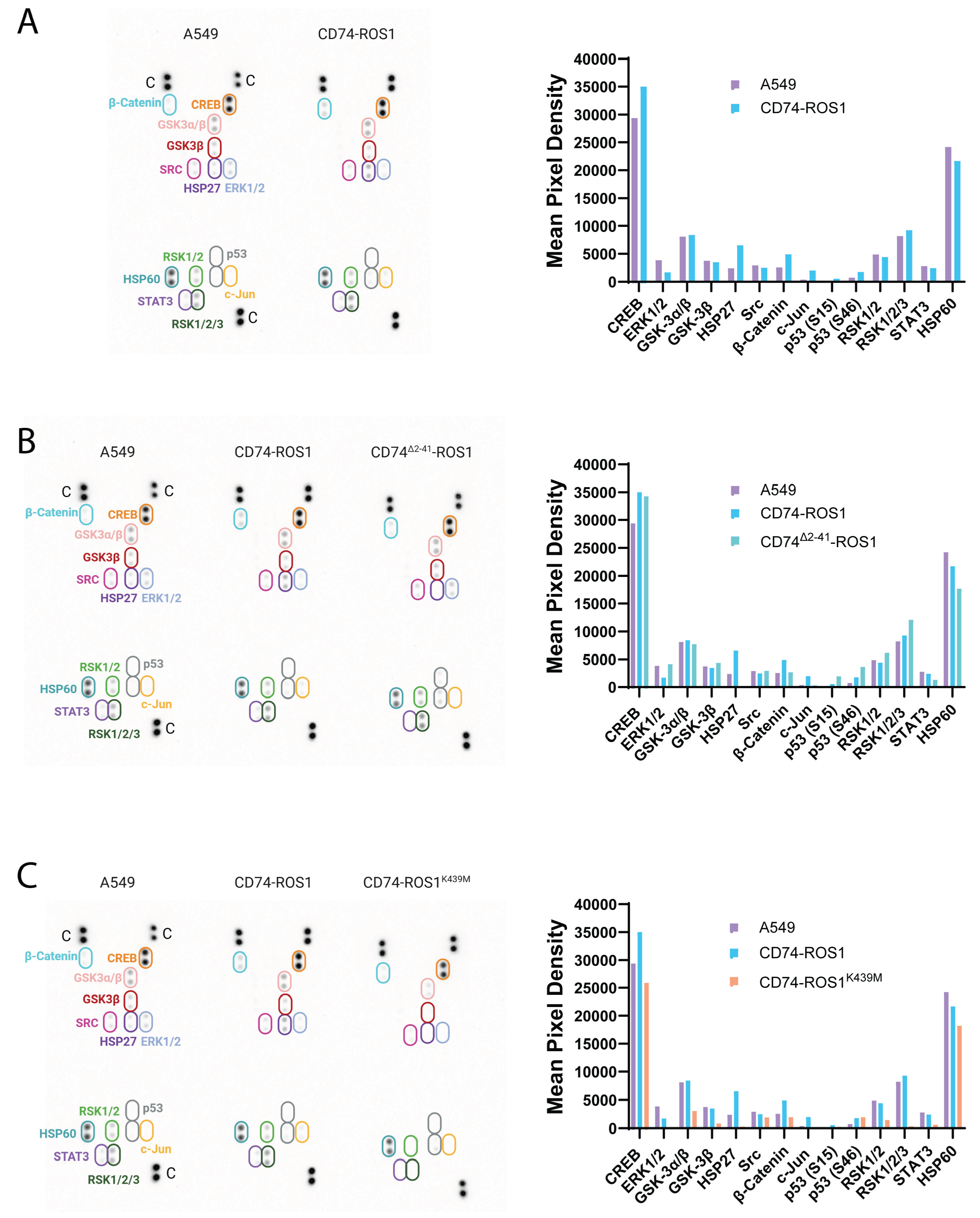

2.4. Exposing the Cellular Signaling of CD74-ROS1 Variants by Phospho-Kinase Analysis

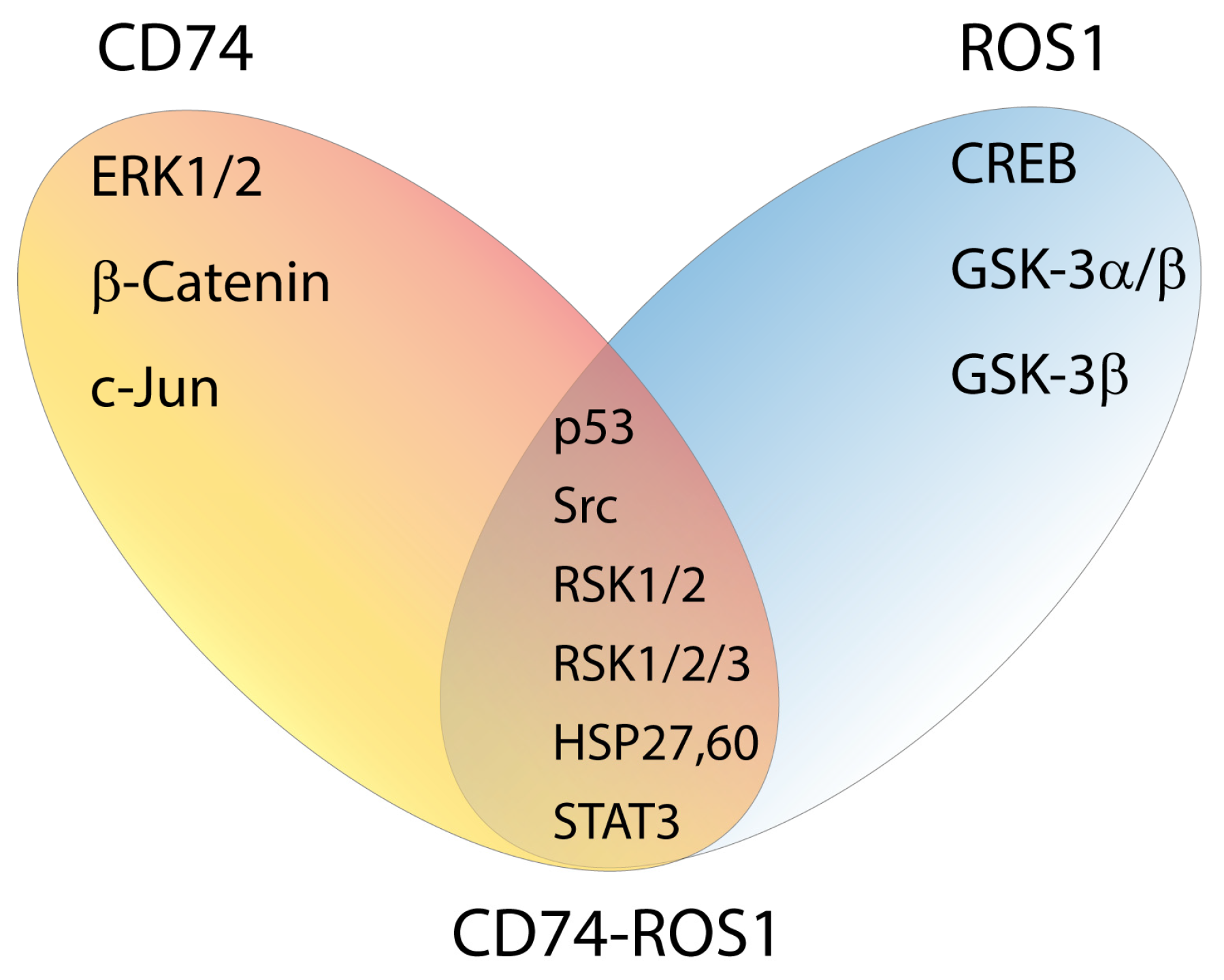

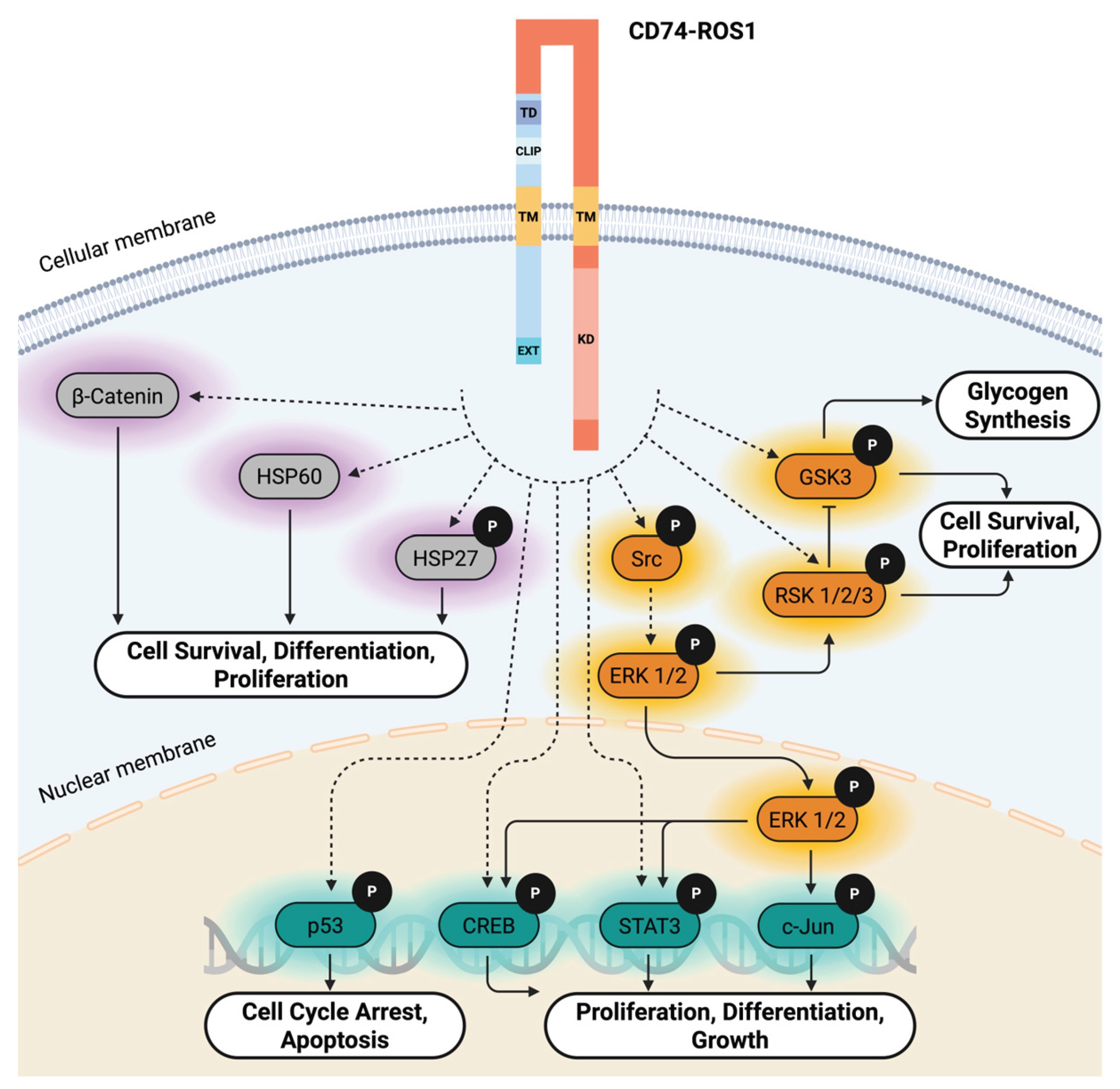

2.5. Functional Insights into CD74-ROS1–Mediated Signaling Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Plasmid Design

4.3. Stable Transfection

4.4. Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction and Sequencing

4.5. RNA Extraction and Complementary DNA (cDNA) Synthesis

4.6. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.7. RNA Sequencing Analysis

4.8. Gene Expression Analysis

- 1.

- That the absolute fold change is less than 1.5 (i.e., |LFC| < 0.585), corresponding to no significant differential expression. This was tested with altHypothesis = “greaterAbs”. Rejecting this null hypothesis corresponds to finding evidence of differential gene expression.

- 2.

- That the absolute fold change is greater than 1.5 (i.e., |LFC| > 0.585), corresponding to equivalent expression. This was tested with altHypothesis = “lessAbs”. Rejecting this null hypothesis corresponds to finding evidence of minimal difference in gene expression.

4.9. Assigning Similarity of Each Mutant Gene

4.10. Phospho-Protein Array Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Z.; Chen, M.; Zheng, W.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, W., Insights into the prognostic value and immunological role of CD74 in pan-cancer. Discov Oncol 2024, 15, (1), 222.

- Schroder, B., The multifaceted roles of the invariant chain CD74--More than just a chaperone. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1863, (6 Pt A), 1269-81.

- Strubin, M.; Berte, C.; Mach, B., Alternative splicing and alternative initiation of translation explain the four forms of the Ia antigen-associated invariant chain. EMBO J 1986, 5, (13), 3483-8.

- Leng, L.; Metz, C. N.; Fang, Y.; Xu, J.; Donnelly, S.; Baugh, J.; Delohery, T.; Chen, Y.; Mitchell, R. A.; Bucala, R., MIF signal transduction initiated by binding to CD74. J Exp Med 2003, 197, (11), 1467-76.

- Merk, M.; Zierow, S.; Leng, L.; Das, R.; Du, X.; Schulte, W.; Fan, J.; Lue, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, H.; Chagnon, F.; Bernhagen, J.; Lolis, E.; Mor, G.; Lesur, O.; Bucala, R., The D-dopachrome tautomerase (DDT) gene product is a cytokine and functional homolog of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, (34), E577-85.

- Shi, X.; Leng, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, W.; Du, X.; Li, J.; McDonald, C.; Chen, Z.; Murphy, J. W.; Lolis, E.; Noble, P.; Knudson, W.; Bucala, R., CD44 is the signaling component of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor-CD74 receptor complex. Immunity 2006, 25, (4), 595-606.

- Bernhagen, J.; Krohn, R.; Lue, H.; Gregory, J. L.; Zernecke, A.; Koenen, R. R.; Dewor, M.; Georgiev, I.; Schober, A.; Leng, L.; Kooistra, T.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Ghezzi, P.; Kleemann, R.; McColl, S. R.; Bucala, R.; Hickey, M. J.; Weber, C., MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nature Medicine 2007, 13, (5), 587-596.

- Schwartz, V.; Lue, H.; Kraemer, S.; Korbiel, J.; Krohn, R.; Ohl, K.; Bucala, R.; Weber, C.; Bernhagen, J., A functional heteromeric MIF receptor formed by CD74 and CXCR4. FEBS Lett 2009, 583, (17), 2749-57.

- Tarnowski, M.; Grymula, K.; Liu, R.; Tarnowska, J.; Drukala, J.; Ratajczak, J.; Mitchell, R. A.; Ratajczak, M. Z.; Kucia, M., Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Is Secreted by Rhabdomyosarcoma Cells, Modulates Tumor Metastasis by Binding to CXCR4 and CXCR7 Receptors and Inhibits Recruitment of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Molecular Cancer Research 2010, 8, (10), 1328-1343.

- Alampour-Rajabi, S.; El Bounkari, O.; Rot, A.; Müller-Newen, G.; Bachelerie, F.; Gawaz, M.; Weber, C.; Schober, A.; Bernhagen, J., MIF interacts with CXCR7 to promote receptor internalization, ERK1/2 and ZAP-70 signaling, and lymphocyte chemotaxis. The FASEB Journal 2015, 29, (11), 4497-4511.

- Lue, H.; Kapurniotu, A.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Roger, T.; Leng, L.; Thiele, M.; Calandra, T.; Bucala, R.; Bernhagen, J., Rapid and transient activation of the ERK MAPK signalling pathway by macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and dependence on JAB1/CSN5 and Src kinase activity. Cell Signal 2006, 18, (5), 688-703.

- Ishimoto, K.; Iwata, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Mizusawa, N.; Tanaka, E.; Yoshimoto, K., D-dopachrome tautomerase promotes IL-6 expression and inhibits adipogenesis in preadipocytes. Cytokine 2012, 60, (3), 772-7.

- Gore, Y.; Starlets, D.; Maharshak, N.; Becker-Herman, S.; Kaneyuki, U.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R.; Shachar, I., Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces B cell survival by activation of a CD74-CD44 receptor complex. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, (5), 2784-92.

- Li, H.; He, B.; Zhang, X.; Hao, H.; Yang, T.; Sun, C.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y., D-dopachrome tautomerase drives astroglial inflammation via NF-κB signaling following spinal cord injury. Cell & Bioscience 2022, 12, (1), 128.

- Lue, H.; Thiele, M.; Franz, J.; Dahl, E.; Speckgens, S.; Leng, L.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Bucala, R.; Luscher, B.; Bernhagen, J., Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) promotes cell survival by activation of the Akt pathway and role for CSN5/JAB1 in the control of autocrine MIF activity. Oncogene 2007, 26, (35), 5046-59.

- Lue, H.; Dewor, M.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R.; Bernhagen, J., Activation of the JNK signalling pathway by macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and dependence on CXCR4 and CD74. Cell Signal 2011, 23, (1), 135-44.

- Qi, D.; Atsina, K.; Qu, L.; Hu, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, B.; Piecychna, M.; Leng, L.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Zhang, J.; Bucala, R.; Young, L. H., The vestigial enzyme D-dopachrome tautomerase protects the heart against ischemic injury. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2014, 124, (8), 3540-3550.

- Ji, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; He, B.; Yang, T.; Sun, C.; Hao, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, A.; Guo, A.; Wang, Y., D-dopachrome tautomerase activates COX2/PGE2 pathway of astrocytes to mediate inflammation following spinal cord injury. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, (1), 130.

- Gil-Yarom, N.; Radomir, L.; Sever, L.; Kramer, M. P.; Lewinsky, H.; Bornstein, C.; Blecher-Gonen, R.; Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Mirkin, V.; Friedlander, G.; Shvidel, L.; Herishanu, Y.; Lolis, E. J.; Becker-Herman, S.; Amit, I.; Shachar, I., CD74 is a novel transcription regulator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, (3), 562-567.

- Acquaviva, J.; Wong, R.; Charest, A., The multifaceted roles of the receptor tyrosine kinase ROS in development and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1795, (1), 37-52.

- Birchmeier, C.; O’Neill, K.; Riggs, M.; Wigler, M., Characterization of ROS1 cDNA from a human glioblastoma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990, 87, (12), 4799-803.

- Drilon, A.; Jenkins, C.; Iyer, S.; Schoenfeld, A.; Keddy, C.; Davare, M. A., ROS1-dependent cancers - biology, diagnostics and therapeutics. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, (1), 35-55.

- Cerutti, G.; Arias, R.; Bahna, F.; Mannepalli, S.; Katsamba, P. S.; Ahlsen, G.; Kloss, B.; Bruni, R.; Tomlinson, A.; Shapiro, L., Structures and pH-dependent dimerization of the sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell 2024, 84, (23), 4677-4690.e6.

- Jones, K.; Keddy, C.; Jenkins, C.; Nicholson, K.; Shinde, U.; Davare, M. A., Novel insight into mechanisms of ROS1 catalytic activation via loss of the extracellular domain. Sci Rep 2024, 14, (1), 22191.

- Ou, S. I.; Nagasaka, M., A Catalog of 5’ Fusion Partners in ROS1-Positive NSCLC Circa 2020. JTO Clin Res Rep 2020, 1, (3), 100048.

- Birchmeier, C.; Sharma, S.; Wigler, M., Expression and rearrangement of the ROS1 gene in human glioblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987, 84, (24), 9270-4.

- Charest, A.; Lane, K.; McMahon, K.; Park, J.; Preisinger, E.; Conroy, H.; Housman, D., Fusion of FIG to the receptor tyrosine kinase ROS in a glioblastoma with an interstitial del(6)(q21q21). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2003, 37, (1), 58-71.

- Bergethon, K.; Shaw, A. T.; Ou, S.-H. I.; Katayama, R.; Lovly, C. M.; McDonald, N. T.; Massion, P. P.; Siwak-Tapp, C.; Gonzalez, A.; Fang, R.; Mark, E. J.; Batten, J. M.; Chen, H.; Wilner, K. D.; Kwak, E. L.; Clark, J. W.; Carbone, D. P.; Ji, H.; Engelman, J. A.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Pao, W.; Iafrate, A. J., ROS1 Rearrangements Define a Unique Molecular Class of Lung Cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012, 30, (8), 863-870.

- Charest, A.; Wilker, E. W.; McLaughlin, M. E.; Lane, K.; Gowda, R.; Coven, S.; McMahon, K.; Kovach, S.; Feng, Y.; Yaffe, M. B.; Jacks, T.; Housman, D., ROS Fusion Tyrosine Kinase Activates a SH2 Domain–Containing Phosphatase-2/Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling Axis to Form Glioblastoma in Mice. Cancer Research 2006, 66, (15), 7473-7481.

- Sato, H.; Schoenfeld, A. J.; Siau, E.; Lu, Y. C.; Tai, H.; Suzawa, K.; Kubota, D.; Lui, A. J. W.; Qeriqi, B.; Mattar, M.; Offin, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Toyooka, S.; Drilon, A.; Rosen, N. X.; Kris, M. G.; Solit, D.; De Stanchina, E.; Davare, M. A.; Riely, G. J.; Ladanyi, M.; Somwar, R., MAPK Pathway Alterations Correlate with Poor Survival and Drive Resistance to Therapy in Patients with Lung Cancers Driven by ROS1 Fusions. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, (12), 2932-2945.

- Nguyen, K. T.; Zong, C. S.; Uttamsingh, S.; Sachdev, P.; Bhanot, M.; Le, M.-T.; Chan, J. L. K.; Wang, L.-H., The Role of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, Rho Family GTPases, and STAT3 in Ros-induced Cell Transformation*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, (13), 11107-11115.

- Zong, C. S.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Sadowski, H. B.; Wang, L.-H., Stat3 Plays an Important Role in Oncogenic Ros- and Insulin-like Growth Factor I Receptor-induced Anchorage-independent Growth*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, (43), 28065-28072.

- Zeng, L.; Sachdev, P.; Yan, L.; Chan, J. L.; Trenkle, T.; McClelland, M.; Welsh, J.; Wang, L. H., Vav3 mediates receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling, regulates GTPase activity, modulates cell morphology, and induces cell transformation. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20, (24), 9212-24.

- Vargas, J.; Pantouris, G., Analysis of CD74 Occurrence in Oncogenic Fusion Proteins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, (21), 15981.

- Esteban-Villarrubia, J.; Soto-Castillo, J. J.; Pozas, J.; San Román-Gil, M.; Orejana-Martín, I.; Torres-Jiménez, J.; Carrato, A.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Molina-Cerrillo, J., Tyrosine Kinase Receptors in Oncology. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (22).

- Shaw, A. T.; Ou, S. H.; Bang, Y. J.; Camidge, D. R.; Solomon, B. J.; Salgia, R.; Riely, G. J.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Shapiro, G. I.; Costa, D. B.; Doebele, R. C.; Le, L. P.; Zheng, Z.; Tan, W.; Stephenson, P.; Shreeve, S. M.; Tye, L. M.; Christensen, J. G.; Wilner, K. D.; Clark, J. W.; Iafrate, A. J., Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, (21), 1963-71.

- Drilon, A.; Siena, S.; Dziadziuszko, R.; Barlesi, F.; Krebs, M. G.; Shaw, A. T.; de Braud, F.; Rolfo, C.; Ahn, M. J.; Wolf, J.; Seto, T.; Cho, B. C.; Patel, M. R.; Chiu, C. H.; John, T.; Goto, K.; Karapetis, C. S.; Arkenau, H. T.; Kim, S. W.; Ohe, Y.; Li, Y. C.; Chae, Y. K.; Chung, C. H.; Otterson, G. A.; Murakami, H.; Lin, C. C.; Tan, D. S. W.; Prenen, H.; Riehl, T.; Chow-Maneval, E.; Simmons, B.; Cui, N.; Johnson, A.; Eng, S.; Wilson, T. R.; Doebele, R. C., Entrectinib in ROS1 fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, (2), 261-270.

- Drilon, A.; Camidge, D. R.; Lin Jessica, J.; Kim, S.-W.; Solomon Benjamin, J.; Dziadziuszko, R.; Besse, B.; Goto, K.; de Langen Adrianus, J.; Wolf, J.; Lee Ki, H.; Popat, S.; Springfeld, C.; Nagasaka, M.; Felip, E.; Yang, N.; Velcheti, V.; Lu, S.; Kao, S.; Dooms, C.; Krebs Matthew, G.; Yao, W.; Beg Muhammad, S.; Hu, X.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Cheema, P.; Stopatschinskaja, S.; Mehta, M.; Trone, D.; Graber, A.; Sims, G.; Yuan, Y.; Cho Byoung, C., Repotrectinib in ROS1 Fusion–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, (2), 118-131.

- Li, W.; Fei, K.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Shu, C.; Wang, J.; Ying, J., CD74/SLC34A2-ROS1 Fusion Variants Involving the Transmembrane Region Predict Poor Response to Crizotinib in NSCLC Independent of TP53 Mutations. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2024, 19, (4), 613-625.

- Takeuchi, K.; Soda, M.; Togashi, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Sakata, S.; Hatano, S.; Asaka, R.; Hamanaka, W.; Ninomiya, H.; Uehara, H.; Lim Choi, Y.; Satoh, Y.; Okumura, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Mano, H.; Ishikawa, Y., RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med 2012, 18, (3), 378-81.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, C.; Liao, C.; Wang, S.; Cao, R.; Ma, T.; Wang, K., Case report: A novel reciprocal ROS1-CD74 fusion in a NSCLC patient partially benefited from sequential tyrosine kinase inhibitors treatment. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1021342.

- Cai, W.; Li, X.; Su, C.; Fan, L.; Zheng, L.; Fei, K.; Zhou, C.; Manegold, C.; Schmid-Bindert, G., ROS1 fusions in Chinese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2013, 24, (7), 1822-1827.

- Chen, Y. F.; Hsieh, M. S.; Wu, S. G.; Chang, Y. L.; Shih, J. Y.; Liu, Y. N.; Tsai, M. F.; Tsai, T. H.; Yu, C. J.; Yang, J. C.; Yang, P. C., Clinical and the prognostic characteristics of lung adenocarcinoma patients with ROS1 fusion in comparison with other driver mutations in East Asian populations. J Thorac Oncol 2014, 9, (8), 1171-9.

- Giménez-Capitán, A.; Sánchez-Herrero, E.; Robado de Lope, L.; Aguilar-Hernández, A.; Sullivan, I.; Calvo, V.; Moya-Horno, I.; Viteri, S.; Cabrera, C.; Aguado, C.; Armiger, N.; Valarezo, J.; Mayo-de-las-Casas, C.; Reguart, N.; Rosell, R.; Provencio, M.; Romero, A.; Molina-Vila, M. A., Detecting ALK, ROS1, and RET fusions and the METΔex14 splicing variant in liquid biopsies of non-small-cell lung cancer patients using RNA-based techniques. Molecular Oncology 2023, 17, (9), 1884-1897.

- Arai, Y.; Totoki, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Nakamura, H.; Hama, N.; Kohno, T.; Tsuta, K.; Yoshida, A.; Asamura, H.; Mutoh, M.; Hosoda, F.; Tsuda, H.; Shibata, T., Mouse model for ROS1-rearranged lung cancer. PLoS One 2013, 8, (2), e56010.

- Nakano, Y.; Tomiyama, A.; Kohno, T.; Yoshida, A.; Yamasaki, K.; Ozawa, T.; Fukuoka, K.; Fukushima, H.; Inoue, T.; Hara, J.; Sakamoto, H.; Ichimura, K., Identification of a novel KLC1–ROS1 fusion in a case of pediatric low-grade localized glioma. Brain Tumor Pathology 2019, 36, (1), 14-19.

- Puno, M. R.; Lima, C. D., Structural basis for RNA surveillance by the human nuclear exosome targeting (NEXT) complex. Cell 2022, 185, (12), 2132-2147.e26.

- Iyer, S. R.; Nusser, K.; Jones, K.; Shinde, P.; Keddy, C.; Beach, C. Z.; Aguero, E.; Force, J.; Shinde, U.; Davare, M. A., Discovery of oncogenic ROS1 missense mutations with sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. EMBO Mol Med 2023, 15, (10), e17367.

- Roskoski, R., Jr., ROS1 protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of ROS1 fusion protein-driven non-small cell lung cancers. Pharmacol Res 2017, 121, 202-212.

- Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, R.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Zuo, D.; Wu, Y., CD74–ROS1 L2026M mutant enhances autophagy through the MEK/ERK pathway to promote invasion, metastasis and crizotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells. The FEBS Journal 2024, 291, (6), 1199-1219.

- Gou, W.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Shen, J.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhai, X.; Zuo, D.; Wu, Y., CD74-ROS1 G2032R mutation transcriptionally up-regulates Twist1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells leading to increased migration, invasion, and resistance to crizotinib. Cancer Letters 2018, 422, 19-28.

- Sun, R.; Meng, Y.; Xu, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Zuo, D., Construction of crizotinib resistant models with CD74-ROS1 D2033N and CD74-ROS1 S1986F point mutations to explore resistance mechanism and treatment strategy. Cellular Signalling 2023, 101, 110497.

- Hong, W. C.; Lee, D. E.; Kang, H. W.; Kim, M. J.; Kim, M.; Kim, J. H.; Fang, S.; Kim, H. J.; Park, J. S., CD74 Promotes a Pro-Inflammatory Tumor Microenvironment by Inducing S100A8 and S100A9 Secretion in Pancreatic Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, (16), 12993.

- Tanese, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Berkova, Z.; Wang, Y.; Samaniego, F.; Lee, J. E.; Ekmekcioglu, S.; Grimm, E. A., Cell Surface CD74-MIF Interactions Drive Melanoma Survival in Response to Interferon-γ. J Invest Dermatol 2015, 135, (11), 2775-2784.

- Li, J.; Lan, T.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, C.; Hou, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, B., Reciprocal activation between IL-6/STAT3 and NOX4/Akt signalings promotes proliferation and survival of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, (2), 1031-48.

- Ranganathan, V.; Ciccia, F.; Zeng, F.; Sari, I.; Guggino, G.; Muralitharan, J.; Gracey, E.; Haroon, N., Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Induces Inflammation and Predicts Spinal Progression in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017, 69, (9), 1796-1806.

- Gu, Y.; Mohammad, I. S.; Liu, Z., Overview of the STAT-3 signaling pathway in cancer and the development of specific inhibitors. Oncol Lett 2020, 19, (4), 2585-2594.

- Braicu, C.; Buse, M.; Busuioc, C.; Drula, R.; Gulei, D.; Raduly, L.; Rusu, A.; Irimie, A.; Atanasov, A. G.; Slaby, O.; Ionescu, C.; Berindan-Neagoe, I., A Comprehensive Review on MAPK: A Promising Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, (10).

- Jun, H. J.; Johnson, H.; Bronson, R. T.; de Feraudy, S.; White, F.; Charest, A., The oncogenic lung cancer fusion kinase CD74-ROS activates a novel invasiveness pathway through E-Syt1 phosphorylation. Cancer Res 2012, 72, (15), 3764-74.

- Chaturvedi, L. S.; Marsh, H. M.; Basson, M. D., Src and focal adhesion kinase mediate mechanical strain-induced proliferation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in human H441 pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007, 292, (5), C1701-13.

- De Kock, L.; Freson, K., The (Patho)Biology of SRC Kinase in Platelets and Megakaryocytes. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020, 56, (12).

- Yang, W. S.; Caliva, M. J.; Khadka, V. S.; Tiirikainen, M.; Matter, M. L.; Deng, Y.; Ramos, J. W., RSK1 and RSK2 serine/threonine kinases regulate different transcription programs in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 1015665.

- Hu, C.; Yang, J.; Qi, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, B.; Zou, F.; Mei, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q., Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm (2020) 2022, 3, (3), e161.

- Pedone, E.; Marucci, L., Role of β-Catenin Activation Levels and Fluctuations in Controlling Cell Fate. Genes 2019, 10, (2), 176.

- Shang, S.; Hua, F.; Hu, Z. W., The regulation of β-catenin activity and function in cancer: therapeutic opportunities. Oncotarget 2017, 8, (20), 33972-33989.

- Wisdom, R.; Johnson, R. S.; Moore, C., c--Jun regulates cell cycle progression and apoptosis by distinct mechanisms. The EMBO Journal 1999, 18, (1), 188-197.

- Jun, H. J.; Roy, J.; Smith, T. B.; Wood, L. B.; Lane, K.; Woolfenden, S.; Punko, D.; Bronson, R. T.; Haigis, K. M.; Breton, S.; Charest, A., ROS1 signaling regulates epithelial differentiation in the epididymis. Endocrinology 2014, 155, (9), 3661-73.

- Steven, A.; Seliger, B., Control of CREB expression in tumors: from molecular mechanisms and signal transduction pathways to therapeutic target. Oncotarget 2016, 7, (23), 35454-65.

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Di, L. J., Glycogen synthesis and beyond, a comprehensive review of GSK3 as a key regulator of metabolic pathways and a therapeutic target for treating metabolic diseases. Med Res Rev 2022, 42, (2), 946-982.

- Piazzi, M.; Bavelloni, A.; Faenza, I.; Blalock, W., Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 and the double-strand RNA-dependent kinase, PKR: When two kinases for the common good turn bad. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2020, 1867, (10), 118769.

- Qu, Z.; Sun, F.; Zhou, J.; Li, L.; Shapiro, S. D.; Xiao, G., Interleukin-6 Prevents the Initiation but Enhances the Progression of Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 2015, 75, (16), 3209-15.

- Neel, D. S.; Allegakoen, D. V.; Olivas, V.; Mayekar, M. K.; Hemmati, G.; Chatterjee, N.; Blakely, C. M.; McCoach, C. E.; Rotow, J. K.; Le, A.; Karachaliou, N.; Rosell, R.; Riess, J. W.; Nichols, R.; Doebele, R. C.; Bivona, T. G., Differential Subcellular Localization Regulates Oncogenic Signaling by ROS1 Kinase Fusion Proteins. Cancer Res 2019, 79, (3), 546-556.

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T. L., Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 134.

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L., Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012, 9, (4), 357-9.

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G. K.; Shi, W., featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, (7), 923-30.

- Simon, A., FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Version 0.10 2010, 1.

- Love, M. I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S., Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, (12), 550.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V., Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 2011, 12, 2825-2830.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).