Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

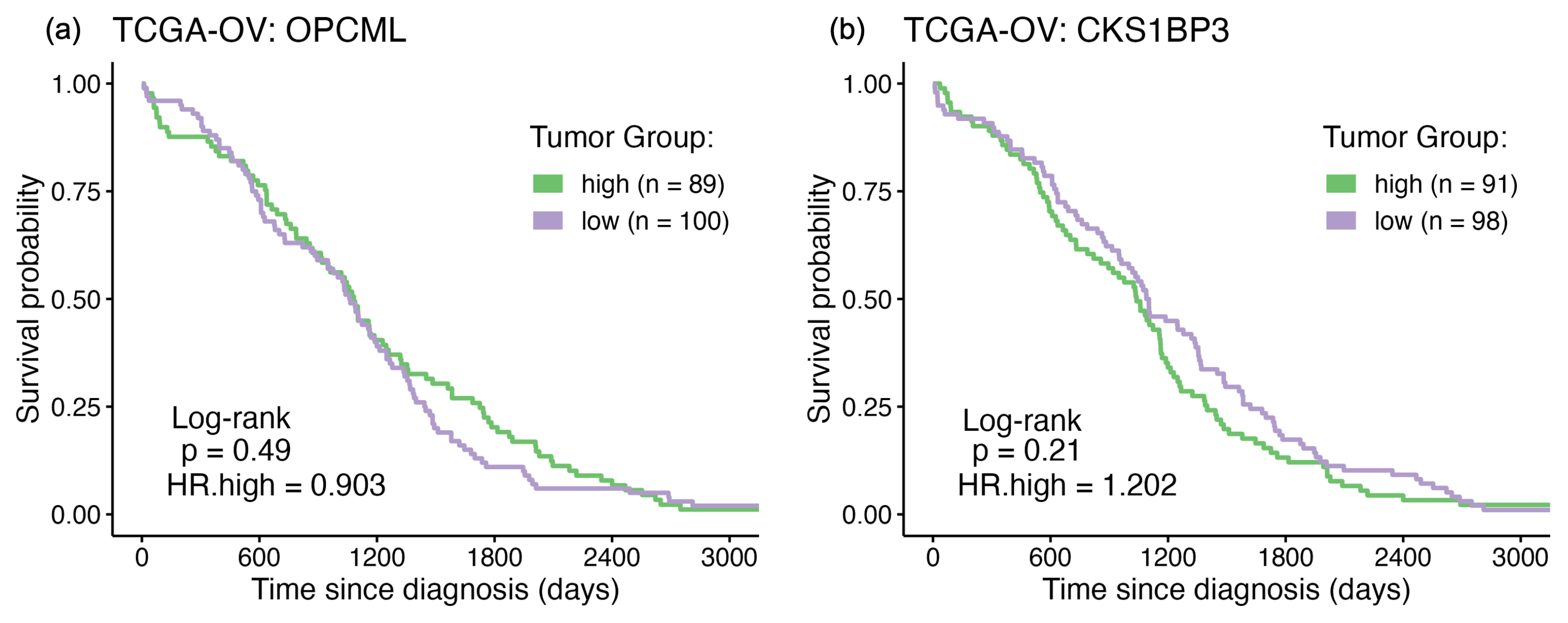

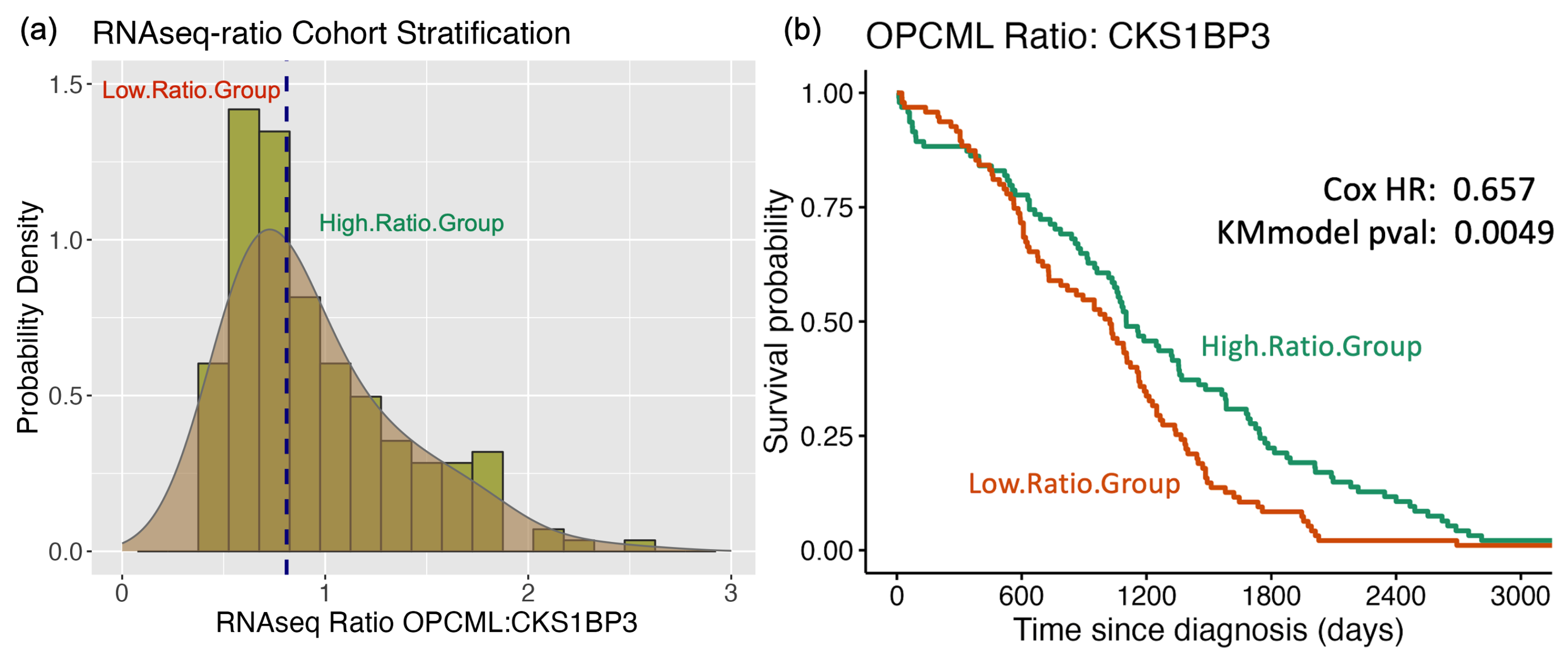

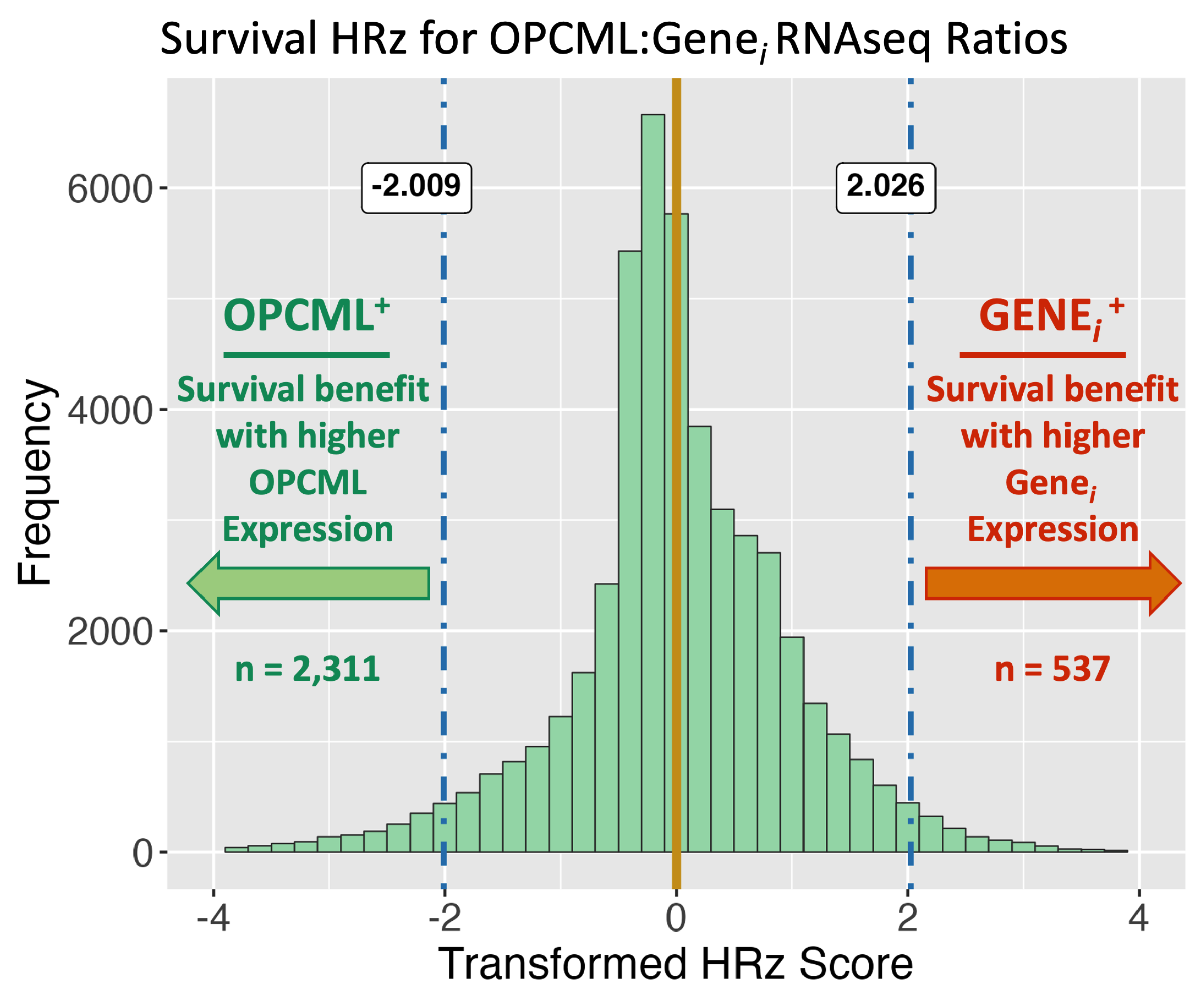

3.1. Survival Curve HR Analyses

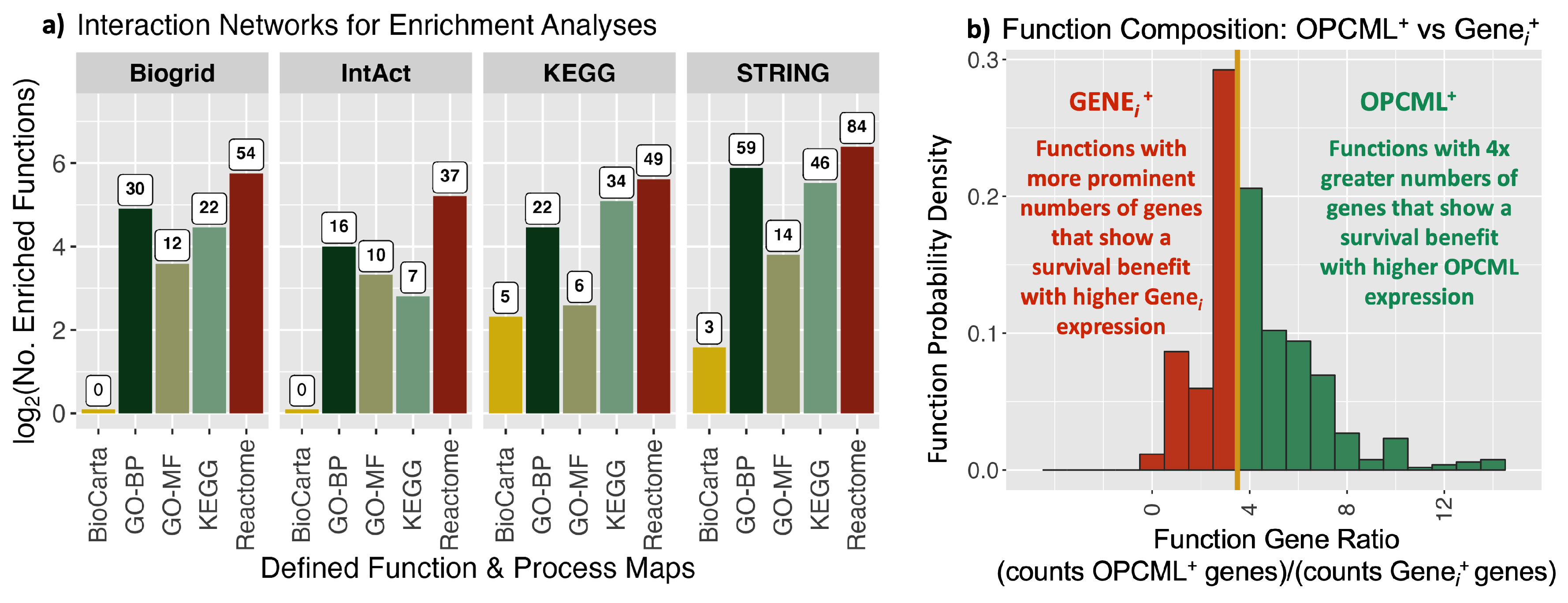

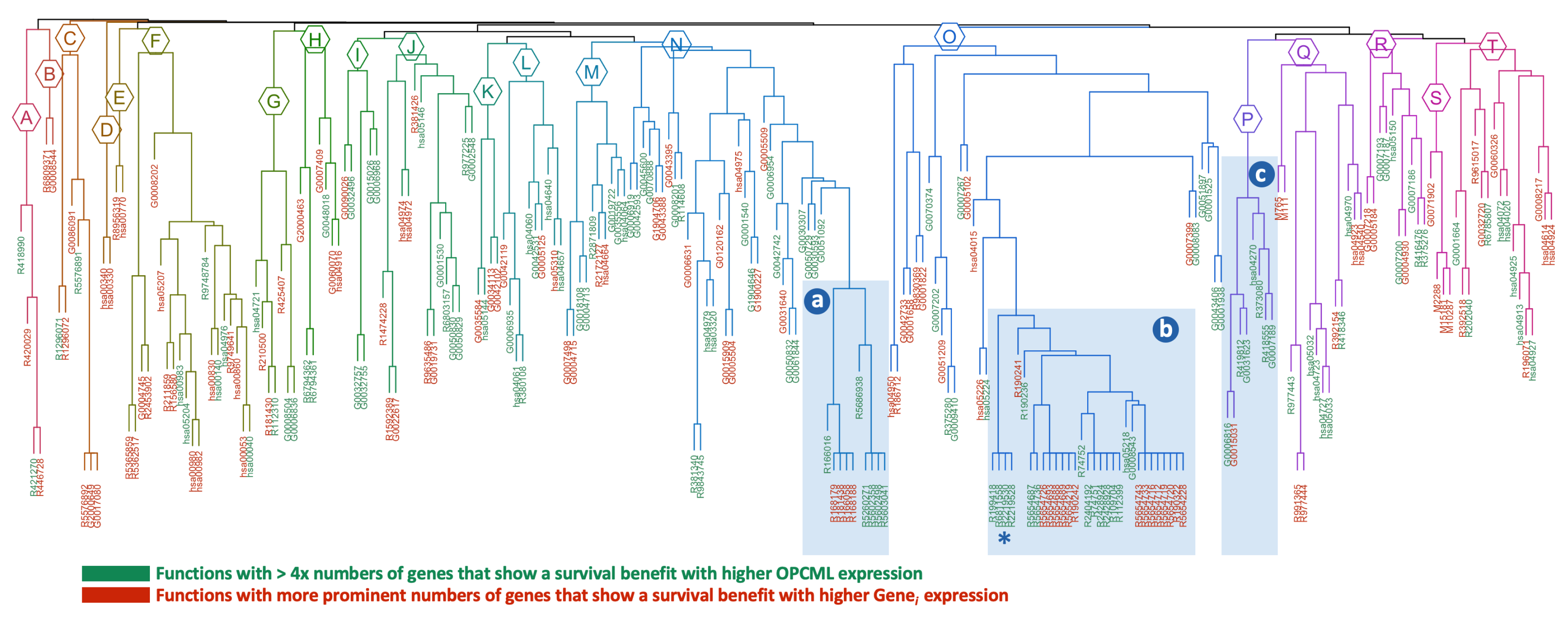

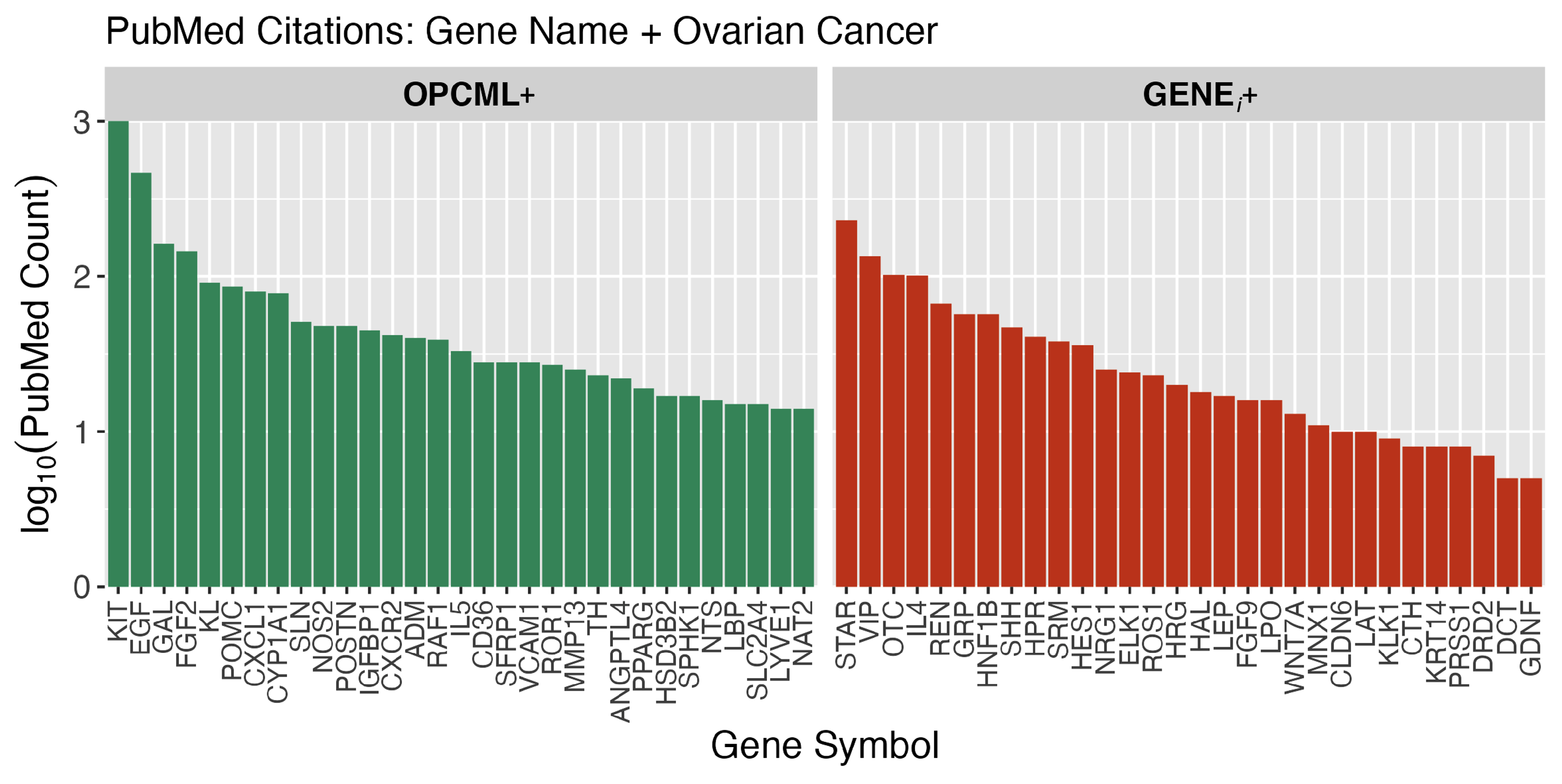

3.2. Functional Enrichment Analyses

4. Discussion

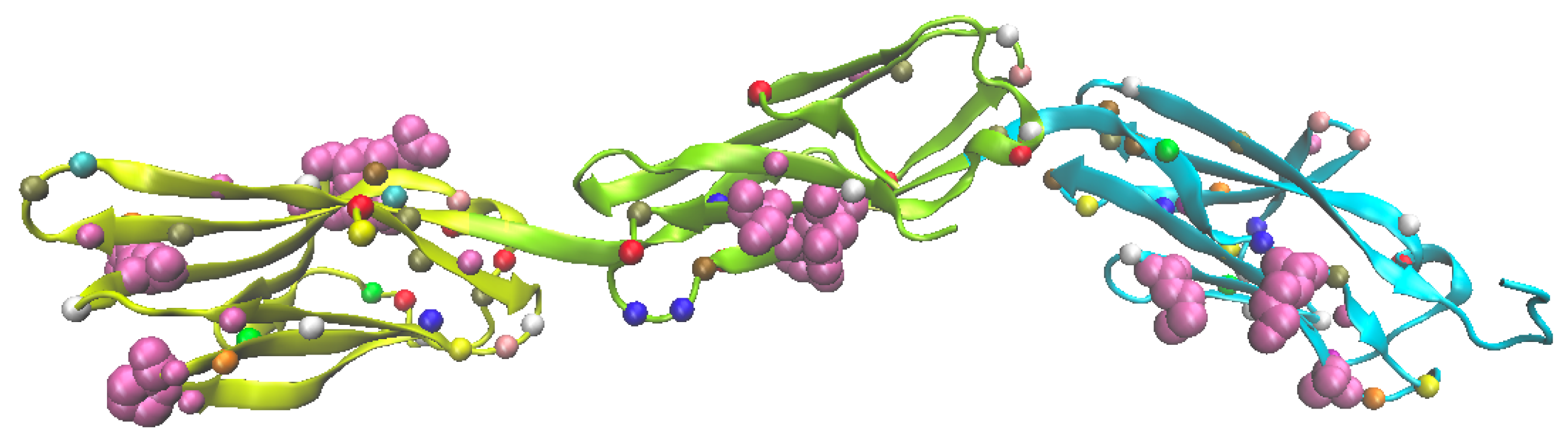

4.1. OPCML & IgLON Family Protein Structure

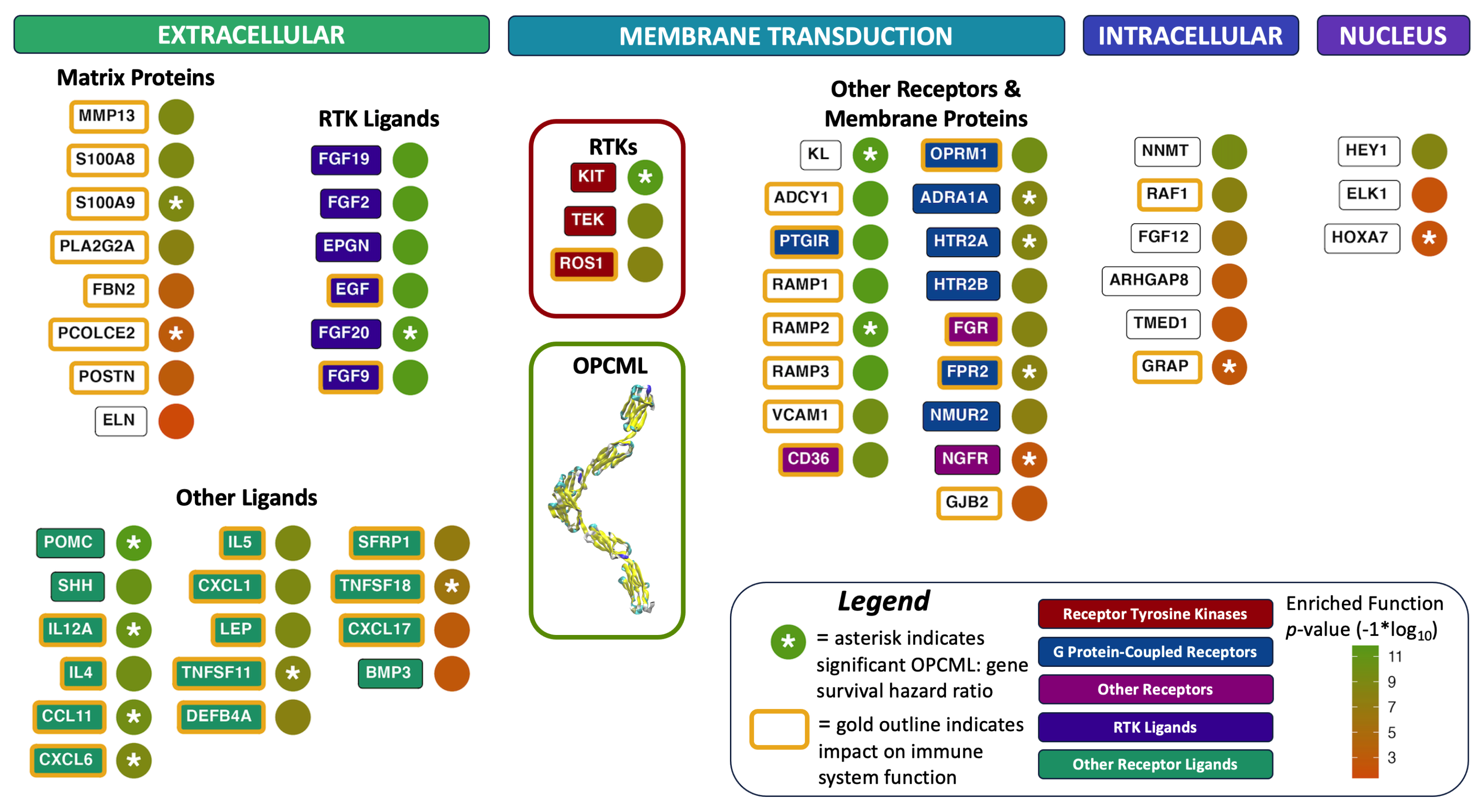

4.2. RTKs, Ligands & Signaling

4.3. OPCML: Tumor Suppressor “Sphere of Influence”

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TSG | Tumor Suppressor Gene |

| OPCML | Opioid Binding and Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| OV | ovarian cancer |

| HR | Cox Hazard Ratios |

| HRz | Z-score transformed Hazard Ratios |

| Ig | Immunoglobin binding domain |

| GO | Gene Ontology Database |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Database |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| RTK | Receptor Tyrosine Kinase signaling pathways |

References

- Wilson, D.; Kim, D.; Clarke, G.; MarshallClarke, S.; Moss, D. A family of glycoproteins (GP55), which inhibit neurite outgrowth, are members of the Ig superfamily and are related to OBCAM, neurotrimin, LAMP and CEPU-1. JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 1996, 109, 3129–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, K.; Gooley, A.; Jeffrey, P. AvGp50, a predominantly axonally expressed glycoprotein, is a member of the IgLON’s subfamily of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). MOLECULAR BRAIN RESEARCH 1997, 44, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellar, G.; Watt, K.; Rabiasz, G.; Stronach, E.; Li, L.; Miller, E.; Massie, C.; Miller, J.; Contreras-Moreira, B.; Scott, D.; et al. OPCML at 11q25 is epigenetically inactivated and has tumor-suppressor function in epithelial ovarian cancer. NATURE GENETICS 2003, 34, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiasz, G.; Scott, D.; Miller, E.; Stronach, E.; Taylor, K.; Ntougkos, E.; Gabra, H.; Smyth, J.; Sellar, G. Microarray analysis of OPCML tumour suppressor function in the SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cell line. BRITISH JOURNAL OF CANCER 2004, 91, S54. [Google Scholar]

- Ntougkos, E.; Rush, R.; Scott, D.; Frankenberg, T.; Gabra, H.; Smyth, J.; Sellar, G. The IgLON family in epithelial ovarian cancer: Expression profiles and clinicopathologic correlates. CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH 2005, 11, 5764–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodoridis, J.; Hall, J.; Marsh, S.; Kannall, H.; Smyth, C.; Curto, J.; Siddiqui, N.; Gabra, H.; McLeod, H.; Strathdee, G.; et al. CpG island methylation of DNA damage response genes in advanced ovarian cancer. CANCER RESEARCH 2005, 65, 8961–8967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, F.; Young, T.; Liu, J.; Cheng, X. RAS-mediated epigenetic inactivation of OPCML in oncogenic transformation of human ovarian surface epithelial cells. FASEB JOURNAL 2005, 19, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y.; Sood, A.K. New Roles Opined for OPCML. CANCER DISCOVERY 2012, 2, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, E.; Louis, L.S.; Antony, J.; Karali, E.; Okon, I.S.; Mckie, A.B.; Vaughan, S.; El-Bahrawy, M.; Stebbing, J.; Recchi, C.; et al. The Tumor-Suppressor Protein OPCML Potentiates Anti-EGFR- and Anti-HER2-Targeted Therapy in HER2-Positive Ovarian and Breast Cancer. MOLECULAR CANCER THERAPEUTICS 2017, 16, 2246–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, J.; Zanini, E.; Kelly, Z.; Tan, T.Z.; Karali, E.; Alomary, M.; Jung, Y.; Nixon, K.; Cunnea, P.; Fotopoulou, C.; et al. The tumour suppressor OPCML promotes AXL inactivation by the phosphatase PTPRG in ovarian cancer. EMBO REPORTS 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtley, J.R.; Alomary, M.; Zanini, E.; Antony, J.; Maben, Z.; Weaver, G.C.; Von Arx, C.; Mura, M.; Marinho, A.T.; Lu, H.; et al. Inactivating mutations and X-ray crystal structure of the tumor suppressor OPCML reveal cancer-associated functions. NATURE COMMUNICATIONS 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simovic, I.; Castano-Rodriguez, N.; Kaakoush, N.O. OPCML: A Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Avenue. TRENDS IN CANCER 2019, 5, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, J.; Zanini, E.; Birtley, J.R.; Gabra, H.; Recchi, C. Emerging roles for the GPI-anchored tumor suppressor OPCML in cancers. CANCER GENE THERAPY 2021, 28, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaprico, A.; Silva, T.C.; Olsen, C.; Garofano, L.; Cava, C.; Garolini, D.; Sabedot, T.S.; Malta, T.M.; Pagnotta, S.M.; Castiglioni, I.; et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. NUCLEIC ACIDS RESEARCH 2016, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounir, M.; Lucchetta, M.; Silva, T.C.; Olsen, C.; Bontempi, G.; Chen, X.; Noushmehr, H.; Colaprico, A.; Papaleo, E. New functionalities in the TCGAbiolinks package for the study and integration of cancer data from GDC and GTEx. PLOS COMPUTATIONAL BIOLOGY 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mubeen, S.; Hoyt, C.T.; Gemuend, A.; Hofmann-Apitius, M.; Froehlich, H.; Domingo-Fernandez, D. The Impact of Pathway Database Choice on Statistical Enrichment Analysis and Predictive Modeling. FRONTIERS IN GENETICS 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; He, Q.Y. ReactomePA: an R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. MOLECULAR BIOSYSTEMS 2016, 12, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulgen, E.; Ozisik, O.; Sezerman, O.U. pathfindR: An R Package for Comprehensive Identification of Enriched Pathways in Omics Data Through Active Subnetworks. FRONTIERS IN GENETICS 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. Gene Ontology Semantic Similarity Analysis Using GOSemSim. In STEM CELL TRANSCRIPTIONAL NETWORKS: METHODS AND PROTOCOLS, 2ND EDITION; Kidder, B., Ed.; Humana, New York, NY, 2020; Vol. 2117, Methods in Molecular Biology, pp. 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. INNOVATION 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oughtred, R.; Rust, J.; Chang, C.; Breitkreutz, B.J.; Stark, C.; Willems, A.; Boucher, L.; Leung, G.; Kolas, N.; Zhang, F.; et al. The BioGRID database: A comprehensive biomedical resource of curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions. PROTEIN SCIENCE 2021, 30, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, S.; Quader, S.; Ono, R.; Cabral, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Hirose, A.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Molecular Network Profiling in Intestinal- and Diffuse-Type Gastric Cancer. CANCERS 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKie, A.B.; Vaughan, S.; Zanini, E.; Okon, I.S.; Louis, L.; de Sousa, C.; Greene, M.I.; Wang, Q.; Agarwal, R.; Shaposhnikov, D.; et al. The OPCML Tumor Suppressor Functions as a Cell Surface Repressor-Adaptor, Negatively Regulating Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. CANCER DISCOVERY 2012, 2, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhuang, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chai, Y.; Zhou, Q. miR-122/NEGR1 axis contributes colorectal cancer liver metastasis by PI3K/AKT pathway and macrophage modulation. JOURNAL OF TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | P-value | xFold | Group | Description |

| a: cluster 16 (n=10) | ||||

| R5602498 | 1.51E-09 | 6.48 | OPCML+ | MyD88 deficiency (TLR2/4) |

| R5603041 | 1.51E-09 | 6.07 | OPCML+ | IRAK4 deficiency (TLR2/4) |

| R5686938 | 3.58E-09 | 4.86 | OPCML+ | Regulation of TLR by endogenous ligand |

| R166016 | 1.18E-08 | 1.71 | OPCML+ | Toll Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Cascade |

| R5602358 | 1.64E-08 | 3.24 | OPCML+ | Diseases associated with the TLR signaling cascade |

| R5260271 | 1.64E-08 | 3.24 | OPCML+ | Diseases of Immune System |

| R181438 | 9.19E-08 | 1.74 | GENE+ | Toll Like Receptor 2 (TLR2) Cascade |

| R168179 | 9.19E-08 | 1.74 | GENE+ | Toll Like Receptor TLR1:TLR2 Cascade |

| R166058 | 9.19E-08 | 1.78 | GENE+ | MyD88:MAL(TIRAP) cascade initiated on plasma membrane |

| R168188 | 9.19E-08 | 1.78 | GENE+ | Toll Like Receptor TLR6:TLR2 Cascade |

| b: cluster 1 (n=31; top 10 shown) | ||||

| R2219530 | 1.41E-12 | 2.52 | OPCML+ | Constitutive Signaling by Aberrant PI3K in Cancer |

| R2219528 | 4.14E-12 | 1.87 | OPCML+ | PI3K/AKT Signaling in Cancer |

| R6811558 | 4.14E-12 | 1.87 | OPCML+ | PI5P, PP2A and IER3 Regulate PI3K/AKT Signaling |

| R199418 | 4.96E-12 | 1.75 | OPCML+ | Negative regulation of the PI3K/AKT network |

| R109704 | 5.83E-12 | 2.76 | OPCML+ | PI3K Cascade |

| R112399 | 8.44E-12 | 2.53 | OPCML+ | IRS-mediated signalling |

| R5654219 | 9.69E-12 | 6.07 | GENE+ | Phospholipase C-mediated cascade: FGFR1 |

| R2428928 | 9.69E-12 | 2.34 | OPCML+ | IRS-related events triggered by IGF1R |

| R2428924 | 9.69E-12 | 2.29 | OPCML+ | IGF1R signaling cascade |

| R74751 | 9.69E-12 | 2.25 | OPCML+ | Insulin receptor signalling cascade |

| c: cluster 6 (n=8) | ||||

| R418555 | 1.69E-12 | 2.35 | OPCML+ | G alpha (s) signalling events |

| R419812 | 1.84E-12 | 16.2 | OPCML+ | Calcitonin-like ligand receptors |

| R373080 | 2.96E-11 | 4.0 | OPCML+ | Class B/2 (Secretin family receptors) |

| hsa04270 | 8.68E-09 | 3.04 | OPCML+ | Vascular smooth muscle contraction |

| G0007189 | 1.49E-08 | 4.77 | OPCML+ | adenylate cyclase-activating G protein-coupled receptor |

| G0031623 | 8.13E-06 | 3.74 | OPCML+ | receptor internalization |

| G0015031 | 0.0007 | 5.28 | GENE+ | external membrane protein transport |

| G0006816 | 0.0106 | 2.31 | OPCML+ | calcium ion transport |

| ID | P-value | xFold | OVca | Top 3 | Top 3 | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2219530 | 1.41E-12 | 2.52 | 323.3 | KIT, EGF, FGF2 | FGF9 | Constitutive Signaling by Aberrant PI3K in Cancer |

| R2219528 | 4.14E-12 | 1.87 | 323.3 | KIT, EGF, FGF2 | FGF9 | PI3K/AKT Signaling in Cancer |

| R6811558 | 4.14E-12 | 1.87 | 323.3 | KIT, EGF, FGF2 | FGF9 | PI5P, PP2A and IER3 Regulate PI3K/AKT Signaling |

| R199418 | 4.96E-12 | 1.75 | 323.3 | KIT, EGF, FGF2 | FGF9 | Negative regulation of the PI3K/AKT network |

| hsa04640 | 1.69E-05 | 1.91 | 271.0 | KIT, IL5, CD36 | IL4 | Hematopoietic cell lineage |

| R6785807 | 1.42E-10 | 3.01 | 257.5 | FGF2, POMC, NOS2 | IL4 | Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 signaling |

| hsa04072 | 0.0029 | 1.76 | 255.9 | KIT, EGF, CXCR2 | DGKK, GRM6 | Phospholipase D signaling pathway |

| G0051897 | 1.74E-05 | 2.31 | 221.8 | KIT, EGF, FGF2 | LEP, ERFE | Positive regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B signal transduction |

| hsa04913 | 0.0001 | 1.98 | 201.9 | STAR, CYP1A1, HSD3B2 | Ovarian steroidogenesis | |

| G0006954 | 1.49E-05 | 1.87 | 197.3 | KIT, CXCR2, ADM | Inflammatory response | |

| R375276 | 1.86E-08 | 2.69 | 173.1 | GAL, POMC, CXCL1 | GRP, GPR37L1, PENK | Peptide ligand-binding receptors |

| hsa04927 | 1.10E-06 | 2.25 | 150.8 | STAR, POMC, HSD3B2 | Cortisol synthesis and secretion | |

| hsa04657 | 1.07E-09 | 1.99 | 150.7 | CXCL1, IL5, MMP13 | IL4 | IL-17 signaling pathway |

| G0001938 | 1.74E-05 | 2.64 | 127.9 | EGF, FGF2, CCL11 | Positive regulation of endothelial cell proliferation | |

| hsa04020 | 2.58E-08 | 2.44 | 122.9 | EGF, FGF2, SLN | FGF9, GDNF, SMIM6 | Calcium signaling pathway |

| G0042531 | 0.0002 | 3.28 | 122.6 | KIT, HES1, IL12A | IL4 | Positive regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT protein |

| hsa04060 | 0.0016 | 1.77 | 109.1 | CXCL1, CXCR2, IL5 | IL4, LEP | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction |

| G0043406 | 0.0017 | 2.92 | 96.7 | EGF, FGF2, TNFSF11 | Positive regulation of MAP kinase activity | |

| hsa04979 | 0.0002 | 1.98 | 95.6 | STAR, CD36, ANGPTL4 | Cholesterol metabolism | |

| R114608 | 0.0077 | 1.74 | 93.8 | EGF, CD36, SELP | HRG | Platelet degranulation |

| hsa04064 | 0.0001 | 2.0 | 91.9 | CXCL1, VCAM1, LBP | LAT | NF-kappa B signaling pathway |

| G0048018 | 0.0133 | 2.92 | 88.6 | EGF, NTS, CCL11 | WNT7A | Receptor ligand activity |

| G0006935 | 1.01E-08 | 2.74 | 85.2 | FGF2, CXCL1, CXCR2 | Chemotaxis | |

| R381340 | 1.24E-09 | 2.13 | 84.0 | CD36, ANGPTL4, PPARG | LEP | Transcriptional regulation of white adipocyte differentiation |

| R9843745 | 3.30E-09 | 1.85 | 84.0 | CD36, ANGPTL4, PPARG | LEP | Adipogenesis |

| G0051092 | 6.92E-07 | 2.28 | 83.6 | ROR1, SPHK1, NTS | CRNN | Positive regulation of NF-kappaB transcription factor activity |

| G0001525 | 0.0058 | 2.43 | 77.5 | EGF, HEY1, HOXA7 | LEP | Angiogenesis |

| G0008201 | 0.0009 | 3.99 | 76.2 | POSTN, SFRP1, LTF | HRG, AOC1 | Heparin binding |

| hsa04925 | 3.56E-08 | 3.34 | 75.7 | STAR, POMC, HSD3B2 | CAMK1G, NPPA | Aldosterone synthesis and secretion |

| G0004713 | 5.10E-09 | 2.81 | 75.3 | KIT, FGR, BTK | ROS1 | Protein tyrosine kinase activity |

| R373080 | 2.96E-11 | 4.0 | 70.9 | VIP, ADM, DHH | SHH, WNT7A | Class B/2 (Secretin family receptors) |

| hsa04061 | 6.41E-09 | 1.98 | 69.4 | CXCL1, CXCR2, CCL11 | Viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor | |

| R380108 | 5.00E-07 | 1.8 | 69.4 | CXCL1, CXCR2, CCL11 | Chemokine receptors bind chemokines | |

| hsa03320 | 5.91E-08 | 2.0 | 61.5 | CD36, ANGPTL4, PPARG | HMGCS2 | PPAR signaling pathway |

| G0019722 | 0.0003 | 6.75 | 59.2 | POMC, SPHK1, TNFSF11 | LAT | Calcium-mediated signaling |

| R166016 | 1.18E-08 | 1.71 | 59.1 | CD36, LBP, S100A9 | DUSP4, MAP3K8 | Toll Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Cascade |

| G0070374 | 0.0008 | 2.54 | 59.0 | FGF2, CD36, TNFSF11 | ARHGAP8 | Positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade |

| G0031623 | 8.13E-06 | 3.74 | 58.9 | CXCR2, ADM, CD36 | Receptor internalization | |

| G0042742 | 3.53E-06 | 3.0 | 58.4 | NOS2, S100A9, S100A8 | LPO | Defense response to bacterium |

| G0007186 | 0.0029 | 1.81 | 58.3 | VIP, CXCL1, AKR1C2 | GPR17 | G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway |

| ID | P-value | xFold | OVca | Top 3 OPCML+ | Top 3 | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0005184 | 0.0001 | 8.1 | 192.2 | GAL, CALCB | GRP, PENK, NPPA | Neuropeptide hormone activity |

| hsa04015 | 9.10E-10 | 1.74 | 179.2 | KIT, EGF, FGF2 | FGF9, LAT, DRD2 | Rap1 signaling pathway |

| hsa05207 | 4.52E-06 | 1.89 | 178.3 | EGF, FGF2, CYP1A1 | FGF9, KPNA7, UGT2B15 | Chemical carcinogenesis - receptor activation |

| G0005102 | 0.0017 | 1.89 | 171.7 | POMC, CXCL1, IGFBP1 | REN, HRG, WNT7A | Signaling receptor binding |

| G0005125 | 3.09E-06 | 2.74 | 164.1 | FGF2, IL5, TNFSF11 | IL4, WNT7A | Cytokine activity |

| hsa05226 | 1.82E-07 | 1.77 | 149.3 | EGF, FGF2, FGF19 | SHH, FGF9, WNT7A | Gastric cancer |

| G0008217 | 0.0027 | 3.64 | 143.5 | POMC, PPARG, RAMP2 | REN, NPPA | Regulation of blood pressure |

| R5654219 | 9.69E-12 | 6.07 | 134.2 | FGF2, KL, FGF20 | FGF9 | Phospholipase C-mediated cascade: FGFR1 |

| R190242 | 1.39E-11 | 5.4 | 134.2 | FGF2, KL, FGF20 | FGF9 | FGFR1 ligand binding and activation |

| hsa04916 | 6.75E-05 | 2.02 | 132.6 | KIT, POMC, RAF1 | WNT7A, DCT | Melanogenesis |

| hsa04664 | 0.0021 | 1.7 | 132.4 | RAF1, IL5, BTK | IL4, LAT | Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway |

| G0120162 | 0.0063 | 1.79 | 125.1 | SLN, CD36, FABP5 | IL4, LEP, ESRRG | Positive regulation of cold-induced thermogenesis |

| R9615017 | 0.0002 | 2.51 | 124.4 | POMC, IGFBP1, PLXNA4 | FOXO-mediated transcription of oxidative stress, metabolic and neuronal genes | |

| R196071 | 1.40E-06 | 2.94 | 96.3 | STAR, POMC, HSD3B2 | TSPOAP1 | Metabolism of steroid hormones |

| G0060326 | 0.0491 | 2.21 | 93.3 | KIT, AGTR1, HOXB9 | Cell chemotaxis | |

| R186712 | 0.0269 | 2.28 | 87.3 | HES1, NR5A2, MAFA | HNF1B | Regulation of beta-cell development |

| M765 | 0.0056 | 3.01 | 85.7 | RAF1, SLC2A4 | ELK1 | BIOCARTA-INSULIN-PATHWAY |

| hsa00330 | 0.0002 | 2.48 | 85.4 | NOS2, SRM, CKM | AOC1, CARNS1 | Arginine and proline metabolism |

| G0032720 | 0.0017 | 2.07 | 76.0 | POMC, LBP, BPI | IL4 | Negative regulation of tumor necrosis factor production |

| R181438 | 9.19E-08 | 1.74 | 71.7 | CD36, S100A9, BTK | DUSP4, MAP3K8 | Toll Like Receptor 2 (TLR2) Cascade |

| R168179 | 9.19E-08 | 1.74 | 71.7 | CD36, S100A9, BTK | DUSP4, MAP3K8 | Toll Like Receptor TLR1:TLR2 Cascade |

| G0001658 | 0.0162 | 5.72 | 71.5 | FGF2 | SHH, GDNF, SALL1 | Branching involved in ureteric bud morphogenesis |

| G0006631 | 0.002 | 2.88 | 70.7 | CYP1A1, CD36, LPL | Fatty acid metabolic process | |

| hsa04540 | 0.0081 | 1.92 | 69.3 | EGF, PRKG1, HTR2A | DRD2, TUBA8 | Gap junction |

| G0005509 | 0.0082 | 2.5 | 66.1 | MMP13, S100A9, S100A8 | SHH, S100A16, SNCB | Calcium ion binding |

| G0001822 | 0.0064 | 2.88 | 64.8 | AGTR1, SIX2 | REN, HNF1B, SALL1 | Kidney development |

| G0043388 | 0.0173 | 4.29 | 62.1 | EGF, PPARG, PRKN | Positive regulation of DNA binding | |

| R211859 | 3.37E-10 | 1.84 | 61.6 | POMC, CYP1A1, NAT2 | ACSM1, ADH4, AOC1 | Biological oxidations |

| R9830369 | 0.007 | 3.85 | 60.0 | FGF2, OSR1, HOXA6 | HNF1B, GDNF, SALL1 | Kidney development |

| G0042102 | 0.0001 | 3.28 | 59.6 | VCAM1, CD1D, NCKAP1L | IL4, LEP | Positive regulation of T cell proliferation |

| hsa04950 | 0.007 | 4.42 | 58.8 | NR5A2, MAFA | HNF1B, MNX1 | Maturity onset diabetes of the young |

| M2288 | 0.0011 | 2.07 | 53.4 | FGF2, CAMK1 | CAMK1G, NPPA | BIOCARTA-NFAT-PATHWAY |

| R166058 | 9.19E-08 | 1.78 | 53.3 | CD36, S100A9, BTK | DUSP4, MAP3K8 | MyD88:MAL(TIRAP) cascade initiated on plasma membrane |

| R168188 | 9.19E-08 | 1.78 | 53.3 | CD36, S100A9, BTK | DUSP4, MAP3K8 | Toll Like Receptor TLR6:TLR2 Cascade |

| hsa05310 | 2.84E-05 | 4.86 | 52.6 | IL5, CCL11, RNASE3 | IL4, PRG2 | Asthma |

| hsa04614 | 0.0003 | 4.63 | 46.1 | AGTR1, CTSG | REN, KLK1 | Renin-angiotensin system |

| M111 | 0.0052 | 4.52 | 43.3 | RAF1, FGR, ADCY1 | BIOCARTA-BARRESTIN-SRC-PATHWAY | |

| R9635486 | 0.0348 | 2.45 | 39.2 | NOS2, LTF, CTSG | Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis | |

| G0015909 | 2.44E-05 | 7.29 | 38.6 | CD36, PPARG, FABP5 | Long-chain fatty acid transport | |

| G0042733 | 0.0215 | 4.56 | 36.7 | SHH, WNT7A, SALL1 | Embryonic digit morphogenesis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).