1. Introduction

The causative agent of Lyme disease (LD),

Borrelia burgdorferi, was first identified in 1982 [

1,

2]. At that time, a connection between

Borrelia burgdorferi (

Bb) and ticks was discovered, and tick bites were recognized as the primary mode of bacterial transmission [

1,

2,

3]. Shortly afterwards,

Bb was also found to cross the human placenta and infect the fetus [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Thus, the potential for human-to-human transmission of

Bb spirochetes in the absence of a tick vector, specifically in-utero transmission, was acknowledged, although it was considered rare [

11].

In later years, additional reports documented transplacental transmission of the causative agent of LD to the human fetus or baby in both North America and Europe [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In addition to human data, experimental animal studies investigating vertical transmission of

Bb produced mixed results, with some reporting its occurrence [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] while others found no such transmission [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Studies involving naturally infected domestic animals [

27,

28,

29] and wildlife populations [

21,

30,

31,

32,

33] also reported evidence for vertical transmission of

Bb.

Currently, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports approximately half a million LD cases annually in the USA alone [

34]. A revised estimate of LD cases in Europe is almost 850,000 per year [

35]. The risk of in-utero transmission of

Bb is recognized by North American public health related institutions [

36,

37,

38], however, there are no standardized diagnostic guidelines for congenital LD.

In this report we present a case of possible vertical transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi, detected using advanced methods including indirect immunofluorescence, PCR, and live-culture, independently confirmed by geographically distant laboratories.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subjects and Informed Consent

The adult subject (age 39) consented to participate in a research study for LD testing for both herself and her child (age 6). The adult subject provided relevant medical records for this study. Written consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Mount Allison Research Ethics Board 2016-042/101796.

2.2. Culture of Borrelia from Participants Samples

All samples were cultured in Barbour-Stoner-Kelly H (BSK-H) complete medium containing 6% rabbit serum (Dalynn Biologicals) with the addition of the following antibiotics as described by Berthold [

39]: phosphomycin (0.002 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), rifampicin (0.005 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), and amphotericin B (0.25 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were collected from different body fluids and inoculated as follows:

A. Urine: Midstream urine samples were collected in a sterile container and then approximately 1 mL was immediately introduced into BSK-H medium with a sterile pipette by the adult subject.

B. Periodontal/Mouth swab: Periodontal swabs were collected using sterile cotton-tipped swabs which were immediately inoculated into BSK-H medium.

C. Vaginal fluid: Vaginal fluid was self-collected by the adult subject by swabbing the inside of the vagina with a sterile cotton-tipped swab which was immediately introduced into BSK-H medium.

All supplies and instructions were provided to the adult participant by the Canadian research laboratory. Collection and inoculation of culture tubes were performed at the participant’s home and shipped at room temperature to the Canadian laboratory. Cultures were incubated at 34oC for 6 weeks, after which microscopic and molecular analyses were performed. To avoid contamination, all procedures were carried out in a Biological Safety Cabinet (LabGard Class II, Type A2). The Biological Safety Cabinet was thoroughly cleaned with ethanol and sterilized and UV-radiation before each sample was processed. Only one tube was open at a time.

2.3. DNA Extraction and PCR Analyses of Cultured and Uncultured Samples

DNA was extracted from the cultures using the Aquaplasmid kit (MultiTarget Pharmaceuticals, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) or the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (see

Supplementary Materials). Total DNA purified from both cultured and uncultured

Borrelia was used as the template in multiple PCR reactions targeting different genomic loci of

Borrelia spp.:

flaB,

ospA, ospC, 16S-23S ITR,

p13, p66, recG, rplB and

uvrA. Conditions for amplification of each genomic locus are described in the

Supplementary Materials. Specific PCR primers are listed in

Tables S1–S3. DNA extracted from archival placental blocks was amplified using internal primers for part of the gene encoding

flaB (

Supplementary Materials). Amplicons obtained by the Canadian and Czech Republic laboratories were sequenced in both directions using the same primers as for PCR. The amplicons from the USA laboratory were cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector for sequencing (K4560-01, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) [

40].

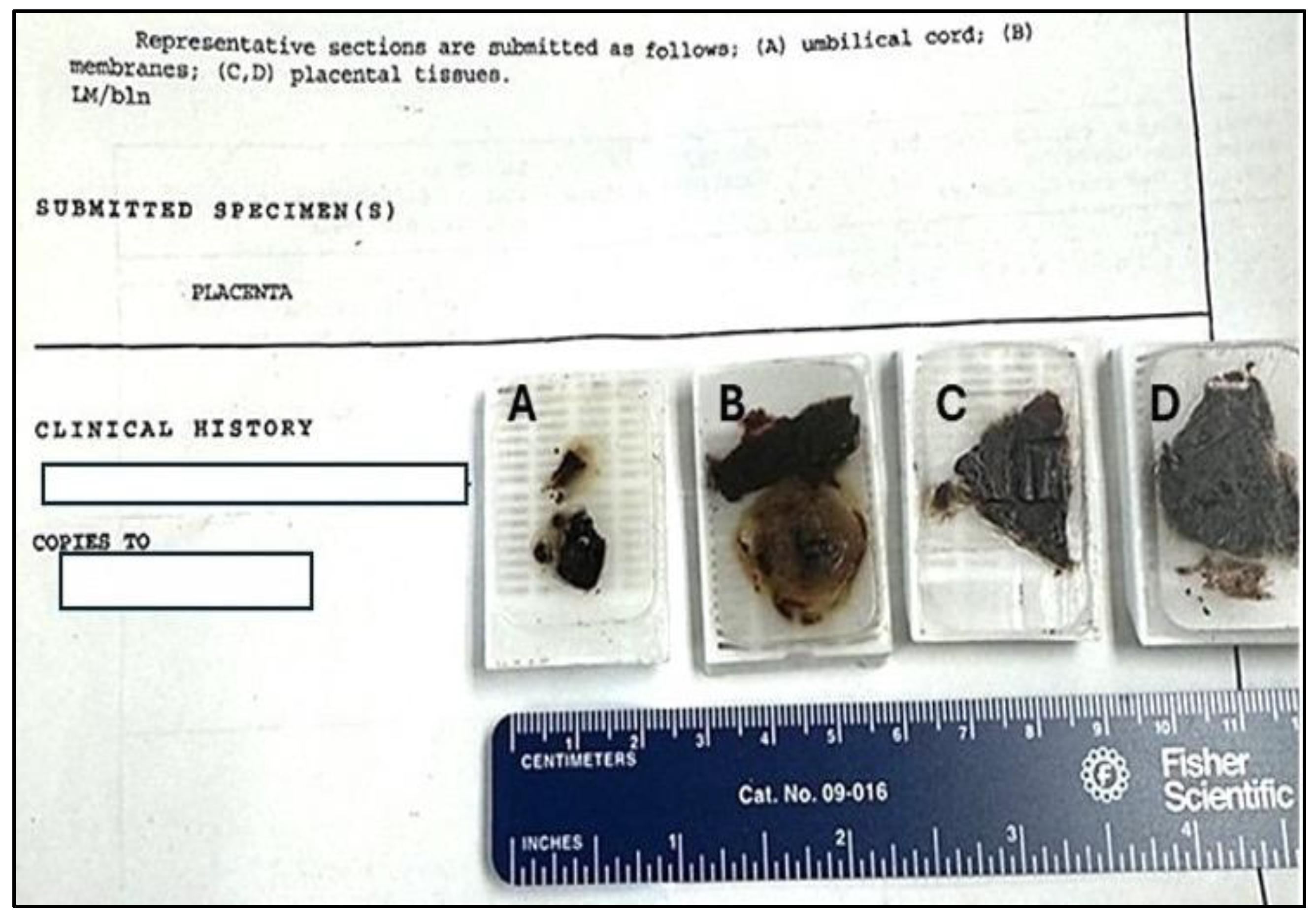

2.4. Multi-Staining and Confocal Imaging of Tissues

Archival tissue blocks were obtained from Trillium Health Partners, Mississauga Hospital, Mississauga, Ontario. One tissue block from the umbilical cord, one from placental membranes and two placental tissue blocks (

Figure 1) were sectioned at 5 microns and staining procedures followed previously described methods [

41]. Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized and incubated with blocking serum (normal donkey 017-000-121, Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), a primary anti-

B. burgdorferi antibody tagged with FITC at 1:100, made in rabbit (MyBiosource, MBS324026, San Diego, CA, USA) and the nuclear dye, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at 3 µmol, (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were mounted in Vectashield Plus Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, H-1900, Newark, CA USA). Images were captured by confocal microscopy.

2.5. PCR Analysis of DNA Extracted from Formalin-Fixed Tissue

The remaining tissue from the imaging experiment was used for further DNA extraction and PCR analyses utilizing the DNA portion of the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Qiagen, No. 80234, Valencia, CA). The brief step-by-step procedure for deparaffinization of embedded tissues is provided in the

Supplementary Materials. Bacterial DNA found in the flow-through after the first spin of the column was used for further PCR analysis (see

Supplementary Materials).

2.6. Processing of Ungrown Borrelia from the Blood Samples

Plasma fractions obtained from blood samples of child and adult subjects in Canada were shipped to the European laboratory. Upon arrival 48 hours later, having been shipped under uncontrolled temperature conditions, the samples were placed at +33

oC to facilitate the growth of live spirochetes. One week after arrival, dark field microscopy was conducted regularly. Contaminated cultures were filtered through a 0.2µm syringe PES filter and the media were replaced. HiMedia 100x Antibiotic Mixture (HiMedia, India) was added to the cultures to achieve final concentrations of 0.002 mg/ml phosphomycin, 0.005 mg/ml rifampicin and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin [

39]. After three week of cultivation the cultures were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 30 minutes and the media were replaced. After a further three weeks of cultivation, when active growth of spirochetes was not apparent, all cultures were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 20 minutes and the pellet was used for total DNA purification (see

Supplementary Materials). PCR analyses were conducted using published PCR primers and strictly followed the conditions established for each primer set (see

Supplementary Materials)[

42,

43].

3. Case Presentation and Results

The adult subject was a resident of a Lyme disease risk area in southern Ontario. She had lived in Singapore, Malaysia, and Kenya. At age 32, during the first trimester of her fourth pregnancy, the mother experienced fever and flu-like symptoms while living in Kenya. Malaria was suspected but excluded through repeated blood smears. At birth, pathological examination of the placenta revealed a term placenta with no significant pathological abnormality, an umbilical cord with three vessels, and no evidence of inflammation. Following the birth, the adult female experienced ongoing and unrelenting fatigue and migratory pain. At age 38, Canadian Public Health Lyme disease serology showed reactivity on the enzyme immunoassay (EIA) but negative Western blots (IgM and IgG). However, a EUROIMMUN Borrelia line blot was positive (NML, Canada). Adult female was diagnosed with Lyme disease by an infectious disease physician in Ontario, Canada and received a ten-week course of intravenous ceftriaxone. Additional tests for Lyme disease showed a positive T-lymphocyte activation assay against Borrelia spp. (Infectolab, Germany) and a CDC-positive Lyme IgM Western blot (IgeneX, USA). In 2023, archived placental samples were requested from the delivery hospital for research purposes.

The child subject was a female resident of a Lyme disease risk area in southern Ontario. She lived continuously in Canada but was in utero in Kenya. She was delivered vaginally at 37 weeks of gestation, weighing 7 Ib 2 oz. She subsequently developed hyperbilirubinemia and was hospitalized overnight for phototherapy. At 11 weeks of age, she developed a high fever and was assessed in the Emergency Department, although routine testing did not identify a cause. Early childhood was characterized by cyclical fevers and cyclical vomiting. At age 4, neurological symptoms of unexplained pain and hypersensitivity to light and sound developed. At that time an IgeneX Lyme IgG western blot revealed positive bands for 31, 34, 39, 41, and 58 kDa, while an IgM western blot revealed band 41 positive and indeterminate band 39 kDa. At age 5, in early winter, following another febrile episode, multiple transient erythematous patches developed. Serological testing for Lyme disease was performed and reported as negative (Public Health Ontario, Canada). At age 5 the child was diagnosed with LD and Bartonella henselae infection by a physician in the USA, and antibiotic treatment was initiated. A Borrelia ELIspot LFA-1 (Arminlabs, Germany) was positive. Serology for Bartonella henselae (IgG) was positive (IGeneX, USA) as well. Later, at the age of 7, a Lyme EIA was positive while Lyme IgG and IgM western blots were negative (Public Health Ontario, Canada). Additional serological testing performed at the National Microbiology Laboratory, Canada against Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii were negative.

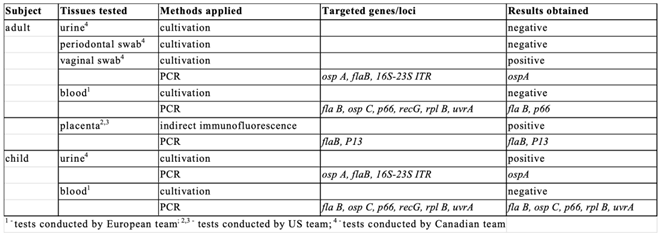

Body fluids were collected from the adult and child subjects (

Table 1) and analyzed in three geographically-distinct laboratories at different times. DNAs extracted from cultured blood samples from both subjects were analyzed in the European laboratory. Cultures were obtained from urine and, for the adult subject, vaginal and periodontal swabs, and were analyzed in the Canadian laboratory. Placental tissues from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) archived samples were analyzed in the USA laboratory.

Multiple sets of primers, targeting the p66, ospC, flaB, recG, rplB and uvrA genes were used (see

Supplementary Materials, Table S2). For the adult subject, fragments of the genes encoding p66 and flaB were obtained. In the case of the child subject samples, amplicons were obtained for the p66, flaB, ospC, rplB and uvrA genes (

Table 1). Alignment of partial sequences of the p66 gene (236 bp) showed 99.58% identity at the DNA level between the adult and child subjects, with a single silent A-G substitution; the identity of the translated sequences was 100% (Supplementary material). Amplification of the partial flaB gene from the adult and child subjects resulted in two identical sequences. Analysis of a partial ospC sequence (620 bp) obtained from the child’s sample revealed 100% identity to the sequences of North American B. burgdorferi s.s. strains belonging to the ospC type A group (

Supplementary Material), the most widely distributed type of ospC gene in the New World. Analyses of partial sequences of the rplB gene (712 bp) and uvr A gene (679 bp) obtained from the child’s sample (

Supplementary Material) confirmed, using the PubMLST database (

www.pubmlst.org), that the B. burgdorferi s.s. strain belonged to the North American B. burgdorferi s.s. group.

These results were all obtained using DNA isolated from spirochetes that had not been grown in BSK-H medium and were presumably alive in the subjects. Although the presence of Borrelia DNA in the blood of both the adult and child subjects was confirmed by amplification of multiple Borrelia genomic loci, cultures of viable Borrelia from this set of samples were negative. Spirochetes were successfully cultured from body fluids of both subjects in BSK-H media that has not been exposed to international shipping. Following culture in the Canadian laboratory, molecular analysis performed on all samples identified Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. For both subjects, amplification of the B. burgdorferi ospA gene was obtained for at least one sample (

Table 1;

Supplementary Material). The amplicon of the expected size, 350 bp, was obtained from vaginal swab-seeded cultures of the adult and urine-seeded cultures for the child. Purified DNA fragments were sequenced and showed 100% identity to the ospA fragments of a wide variety of North American B. burgdorferi s.s. strains (

Supplementary Material). PCR targeting the flaB gene and the 16S - 23S internal transcribed region, using DNA purified from cultured spirochetes as template, did not produce amplicons. The culture results demonstrate live Borrelia in both the mother and child at ages 39 and 5, respectively, when the samples for culture were donated, but do not provide information on when the infection might have occurred.

To gain insight into possible transplacental transmission, four archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples were obtained from the hospital where the child was born. The four samples included a section of the umbilical cord, membranes and two sections of placental tissue (

Figure 1).

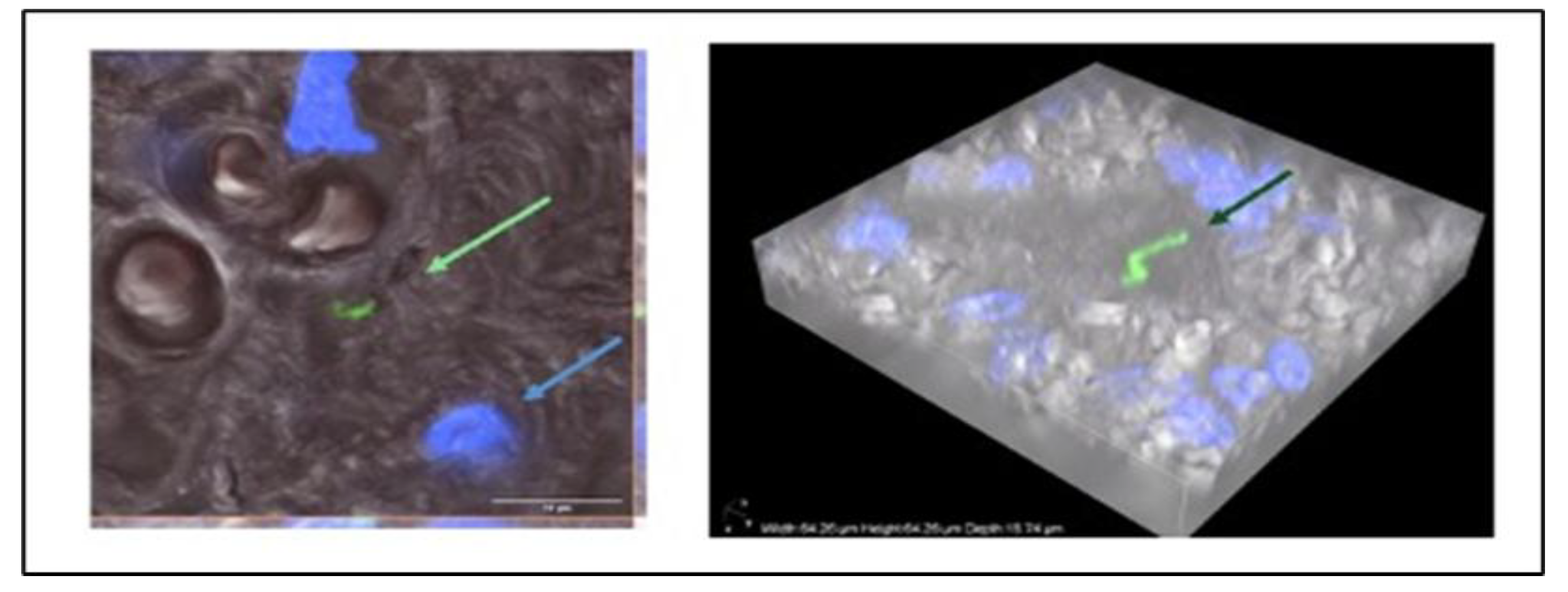

Following deparaffinization and DNA isolation, PCR amplification of partial flaB and p13 genes and sequencing of the amplicons, sequences with high similarity to North American B. burgdorferi s.s. strains were found in two sections of placental tissue. The presence of spirochaetes in the placental tissue was further verified by confocal microscopy of immunoreactive Borrelia burgdorferi in the placental tissue (

Figure 2).

In summary, DNA from a B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain highly similar to the North American group of Lyme disease spirochetes was detected in various samples from adult and child subjects in three independent laboratories. The group of different genomic loci targeted included genes encoding flaB, ospA, ospC, p13, recG, rplB, uvrA and 16S-23S internal transcribed region. Not all amplifications were successful. These findings are supported by direct visualization of an immunostained spirochete in archival placental tissue and the cultivation of viable spirochetes from the body fluids of both subjects.

4. Discussion

We report the detection of morphologically intact Borrelia spirochete in an archival placental tissue sample collected at childbirth, using indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Analysis of DNA extracted from the same archival samples confirmed the presence of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Independent molecular analyses of live spirochetes, which were successfully cultured years later from the mother's vaginal swab and the child's urine, confirmed the identification of the detected spirochetes as Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Additionally, amplification of multiple genomic loci from blood samples of both the adult and child subjects identified the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain specific to North America. The results of multiple molecular and microbiological methods applied by different laboratories, along with the image confirming the presence of immunoreactive Borrelia, verify the existence of the pathogen at birth.

Current diagnostic guidelines for Lyme disease in both North America and Europe recommend an indirect two-tier serological approach that tests for patient antibodies to the pathogen. The first tier is an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), followed by either a different EIA or a western blot. In this case study, the mother tested positive by EIA and negative by western blot for LD; however, a EUROIMMUN Borrelia line blot was later found to be positive. The child was initially negative on both the EIA and western blot for LD, but eventually, the EIA became positive, while the western blot remained negative. Based on serological criteria alone, the child would be considered not to have Lyme disease, yet application of advanced molecular assays and imaging methods allowed direct detection of the pathogen.

Discordance between serology and histopathological findings of

Bb in fetal or placental tissue has previously been reported [

7,

17]. One study described several cases in which maternal LD serology post-partum was negative despite histopathological findings of spirochetes in perinatal autopsy tissues [

7]. Additionally, pathological examination of placentas from sixty asymptomatic women with a positive or equivocal EIA from a LD-endemic area of New York revealed spirochetes by silver stain in three of sixty (5%) placentas, with further PCR confirmation of

B. burgdorferi in two of these three placentas [

17]. Serological testing for LD in the three women with placental spirochetes showed an equivocal ELISA in all three, negative western blots in two, and an indeterminate western blot in one. There was no relationship between the presence of placental spirochetes and serological testing, and based on serological interpretation, two of these women would be considered not to have LD despite placental infection with the spirochete [

17].

A differential diagnosis of congenitally acquired LD was not considered for the child described in this report at the time of birth or in early infancy. Even if LD had been suspected, there are currently no diagnostic criteria or treatment guidelines for congenital LD. Such guidelines do exist for other vector-borne infections known to be transmitted in-utero, such as Zika virus, West Nile virus and Chagas disease [

44,

45,

46]. In general, diagnostic approaches for congenital infections in a newborn infant may include a broad range of both indirect and direct testing methodologies including serological testing and culture and/or detection of pathogen specific nucleic acids from tissues and body fluids [

47,

48].

Historical recommendations for laboratory testing for the diagnosis of congenital Lyme infection were proposed in specialty medical textbooks but never became widely known nor adopted in clinical practice [

49,

50]. In one set of recommendations, major diagnostic criteria to confirm congenital Lyme disease included: 1)

Bb-specific IgM in cord blood or in the patient’s serum immediately following delivery; 2) culture of

Bb from the placenta or the newborn; or 3) histological identification of

Bb in infant tissues utilizing

Bb specific immunofluorescent techniques [

50]. Separate recommendations from an infectious disease pediatrician advised evaluation of any infant with suspected congenital LD with serologic testing for both

Bb IgM and IgG ELISA and IgM and IgG Western blot on paired maternal and cord blood at delivery, along with infant’s blood and preferably cerebrospinal fluid after birth. If possible, culture and PCR testing for

Bb should be performed on these samples [

50]. In addition, a full histopathological examination of any placenta, miscarriage, stillbirth or perinatal death from a pregnancy impacted by LD should be undertaken, which utilizes testing such as silver and

Bb specific antibody stains, culture or PCR [

50].

Several early case reports documenting histopathological findings of

Bb identified in either fetal/infant or placental tissues, revealed a lack of or minimal accompanying inflammation [

4,

6,

7,

9]. A 2011 report from the Czech Republic documented evidence of

Bb detected in placental tissues by PCR, culture and electron microscopy from women who had been treated with penicillin for LD in the first trimester of pregnancy, noting placental inflammation was minimal [

15].

In this study, the child’s infection could be due to either independent vector-borne transmission, congenital transmission, or both. As both mother and child present with the same strain of B. burgdorferi – specifically, the widely distributed species common to their region of residence B. burgdorferi s.s. ospC type A and given the presence of B. burgdorferi identified in the placental tissues through both immunostaining and DNA analysis, vertical transmission is a plausible explanation. The findings in this study support the need for further research into alternative, non-vector routes of Borrelia transmission. This topic deserves attention, as the results heighten the diagnostic complexity of managing Lyme disease if it is both a vector-borne and vertically transmitted disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data curation and validation, N.R., M.E. L.B, and V.L.; formal analysis, M.G., M.H.H.; investigation, M.G., N.R., M.E. L.B., M.H.H and V.L.; resources, V.L., M.E., L.B. and N.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R., L.B, M.E. and V.L.; writing—review and editing, N.R., L.B., M.G., M.H.H., M.E., and V.L.; funding acquisition, N.R., V.L. M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by grant from Czech Science Foundation and grant LUC23151 INTER-COST from Ministry of Education, Youths and Sport of the CR (NR and MG).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Written consent was obtained and the study was approved by the Mount Allison Research Ethics Board 2016-042/ 101796.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Zachary Blankenheim and Andrea Huchthausen for an excellent technical support (University of Minnesota, Duluth, MN, USA). We greatly appreciate discussions with Drs. Charlotte Mao and Elliot Jacobsen that helped to clarify the clinical issues presented in this paper. We are thankful to Sue Faber from LymeHope for manuscript review. We also want to acknowledge Dr. Timothy Cook and Dr. Sarah Keating for their contributions to this case.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LD |

Lyme disease |

| EIA |

enzyme immunoassay |

| BSK |

Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly |

| FFPE |

formalin-fixed paraffin embedded |

References

- Burgdorfer, W.; Barbour, A.G.; Hayes, S.; Benach, J.L.; Grunwaldt, E.; Davis, J.P. Lyme disease-a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 1982, 216, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorfer, W. Lyme borreliosis: ten years after discovery of the etiologic agent, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infection 1991, 19, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steere, A.C. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 321, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, P.A.; Duray, P.H.; Burke, B.A.; Steere, A.C.; Stillman, M.T. Maternal-fetal transmission of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Ann. Intern. Med. 1985, 103, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, A.B. Human fetal borreliosis, toxemia of pregnancy, and fetal death. Zentralbl Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A 1986, 263, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.B.; Benach, J.L.; Burgdorfer, W. Stillbirth following maternal Lyme disease. N. Y State J. Med. 1987, 87, 615–616. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, A.B. Gestational Lyme borreliosis. Implications for the fetus. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1989, 15, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, P.E.; Lattner, B.P.; Duray, P.H.; Barbour, A.G.; Johnson, R.C. Culture Positive Seronegative Transplacental Lyme Borreliosis Infant Mortality A:74. In 51st Annual Meeting, Scientific Abstracts; American Rheumatism Association, 1987; p. S50. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K.; Bratzke, H.J.; Neubert, U.; Wilske, B.; Duray, P.H. Borrelia burgdorferi in a newborn despite oral penicillin for Lyme borreliosis during pregnancy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1988, 7, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duray, P.H.; Steere, A.C. Clinical pathologic correlations of Lyme disease by stage. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1988, 539, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, D.T. Epidemiology. In Lyme Disease. Mosby Year Book; Coyle, P.K., Ed.; 1993; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dattwyler, R.J.; Volkman, D.J.; Luft, B.J. Immunologic aspects of Lyme borreliosis. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1989, 11, S1494–S1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, G.; Stinco, G.; Cinco, M. Neonatal skin lesions due to a spirochetal infection: a case of congenital Lyme borreliosis? Int. J. Dermatol. 1997, 36, 677–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulínská, D.; Votýpka, J.; Vaňousová, D.; et al. Identification of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in patients with erythema migrans. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2009, 54, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulínská, D.; Votýpka, J.; Hořejší, J. Diseminovaná borrelióza a její průkaz v laboratoři [Disseminated Lyme borreliosis and its laboratory diagnosis]. Zprávy Epidemiol. A Mikrobiol. 2011, 20, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hercogová, J.; Vaňousová, D. Syphilis and borreliosis during pregnancy. Dermatol. Ther. 2008, 21, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, R.; Bracero, L.A.; Aguero-Rosenfeld, M.; Beneck, D.; Coleman, J.; Schwartz, I. Confirmation of Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes by polymerase chain reaction in placentas of women with reactive serology for Lyme antibodies. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 1996, 41, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubico-Navas, S. Experimental and Epizootiologic Studies of Lyme Disease. Doctoral Dissertation. PhD, Colorado State University, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, R.M.; Yang, L.; Daynes, R.A.; Branch, D.W.; Salafia, C.M.; Weis, J.J. Fetal outcome in murine Lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaie, S.; Mookherjee, S.; Assian, E.; Al-Taie, F.; Nakeeb, S.; Siddiqui, S. Transplacental Transmission of Bb In a Murine Model. In 10th Annual International Scientific Conference on Lyme Disease & Other Tickborne Disorders; National Institutes of Health, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, J. The in Utero and Seminal Transmission of Borrelia Burgdorferi in Canidae. PhD, The University of Wisconsin Madison, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, J.; Burgess, E.; Wachal, M.; Steinberg, H. Intrauterine transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1993, 54, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S,; Nielsen, S. Experimental infection of the white-footed mouse with Borrelia burgdorferi. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1990, 51, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, K.D.; Barthold, S.W. Relative infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lewis rats by various routes of inoculation. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1991, 44, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, T.; Telford, S.R.; Adler, G.H. Absence of transplacental transmission of Lyme disease spirochetes from reservoir mice (Peromyscus leucopus) to their offspring. J. Infect. Dis. 1991, 164, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrum, J.E.; Oliver, J.H. Investigation of venereal, transplacental, and contact transmission of the lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, in Syrian hamsters. J. Parasitol. 1999, 85, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, E. Borrelia burgdorferi infection in Wisconsin horses and cows. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1988, 539, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, E.; Gendron-Fitzpatrick, A.; Mattison, M. Foal mortality associated with natural infection of pregnant Mares with Borrelia burgdorferi. In 5th Int. Conference Equine Infectious Diseases; Powell, D., Ed.; Press of Kentucky, 1989; pp. 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Leibstein, M.; Khan, M.; Bushmich, S. Evidence for in-utero Transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi from Naturally Infected Cows. J. Spirochetal Tick-Borne Dis. 1998, 5, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.F.; Johnson, R.C.; Magnarelli, L.A. Seasonal prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in natural populations of white-footed mice, Peromyscus leucopus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987, 25, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, E.C.; Wachal, M.D.; Cleven, T.D. Borrelia burgdorferi infection in dairy cows, rodents, and birds from four Wisconsin dairy farms. Vet. Microbiol. 1993, 35, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Hou, X. [Preliminary investigation on reservoir hosts of Borrelia burgdorferi in China]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 1999, 28, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, E.C.; Windberg, L.A. Borrelia sp. infection in coyotes, black-tailed jack rabbits and desert cottontails in southern Texas. J. Wildl. Dis. 1989, 25, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugeler, K.J.; Schwartz, A.M.; Delorey, M.J.; Mead, P.S.; Hinckley, A.F. Estimating the Frequency of Lyme Disease Diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION on Lyme disease (Borreliosis) | B8-0514/2018 | European Parliament. 15 October 2025. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/B-8-2018-0514_EN (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy and Lyme disease. Pregnancy and Lyme Disease. 27 January 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/toolkit/factsheets/Pregnancy-and-Lyme-Disease-508 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lyme disease: For health professionals - Canada.ca. 2025. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/lyme-disease/health-professionals-lyme-disease (accessed on day month year).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. Lyme Disease: The Facts, The Challenge. 2008;(NIH Publication No. 08-7045):1-23. 2008. Available online: https://permanent.fdlp.gov/lps81243/LymeDisease (accessed on day month year).

- Berthold, A.; Faucillion, M.; Nilsson, I.; Golovchenko, M.; Lloyd, V.; Bergström, S.; Rudenko, N. Cultivation methods of spirochetes from Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex and relapsing fever Borrelia. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 189, e64431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, M.E.; Mozayeni, B.R.; Radovsky, L.; Bemis, L.T. Bartonella- and borrelia-related disease presenting as a neurological condition revealing the need for better diagnostics. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Ericson, M.; Maggi, R.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Vasculitis, cerebral infarction and persistent Bartonella henselae infection in a child. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.; Golovchenko, M.; Vancova, M.; Clark, K.; Grubhoffer, L.; Oliver, J. H., Jr. Isolation of live Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato spirochaetes from patients with undefined disorders and symptoms not typical for Lyme borreliosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 267.e9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.; Golovchenko, M.; Lin, T.; Gao, L.; Grubhoffer, L.; Oliver, J.H. Jr. Delineation of a New Species of the Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato Complex, Borrelia americana sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3875–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Considerations for Congenital Chagas Disease | Chagas Disease | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chagas/hcp/considerations/index (accessed on day month year).

- Collecting and Submitting Placental and Fetal Tissue Specimens for Zika Virus Testing | Zika Virus | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/hcp/diagnosis-testing/placental-and-fetal-tissue-specimens (accessed on day month year).

- Interim guidelines for the evaluation of infants born to mothers infected with West Nile virus during pregnancy. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2004, 53, 1436. [CrossRef]

- Ostrander, B.; Bale, J.F. Congenital and perinatal infections. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019, 162, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remington, J.S.; Klein, J.O.; Maldonado, Y.A.; et al. Current Concepts of Infections of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. In Remington and Klein’s Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant, 9th ed.; Maldonado, Y., Nizet, V., Barnett, E., Edwards, K.M., Malley, R., Eds.; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, P.S. Fetal Effects from Lyme Disease. In The Birth Defects Encyclopedia; Buyse, M.L., Ed.; Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1990; pp. 696–697. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, T. Lyme Disease. In Remington and Klein’s Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant, 5th ed.; Remington, J.S., Klen, J.O., Eds.; W.B Saunders Company, 2001; pp. 519–641. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).