Introduction

As AI technologies become more integrated into socially sensitive domains, they are often required to navigate overlapping legal and ethical frameworks [

1]. Conflicts between legal requirements and ethical obligations can occasionally arise, placing AI systems in situations where fulfilling both simultaneously becomes infeasible [

2]. A normative conflict arises when fulfilling one obligation necessarily leads to the violation of another, making it impossible to satisfy both simultaneously [

3]. For example, an autonomous healthcare agent might face a conflict between respecting a patient’s autonomy (an ethical norm) and preventing harm by intervening without consent (a legal or safety requirement). In safety-critical fields like healthcare and law enforcement, resolving normative conflicts between ethics and law is one of the most pressing concerns in responsible AI deployment [

4].

A growing body of work has explored the use of formal knowledge representation and reasoning frameworks to model and resolve normative conflicts [

5]. Within the Semantic Web framework, tools such as OWL and SWRL are commonly used to formally represent normative logic, enabling systems to perform automated reasoning on encoded policies. OWL ontologies serve to formally represent domain-specific elements such as actions, agents, and their interrelations, whereas SWRL rules define the logic of conditional permissions or constraints. OWL and SWRL have seen practical use in supporting automated compliance analysis and reasoning over regulatory and normative frameworks [

6]. However, encoding complex ethical and legal rules directly in OWL/SWRL is challenging for non-technical domain experts, as these languages have limitations in expressiveness and are not very user-friendly for this purpose [

7]. Rule-based frameworks such as SWRL and SHACL are often challenging for non-technical users, due to their low readability and reliance on formal logic representations. As a result, existing semantic tools often present a barrier to participation for ethicists and legal professionals seeking to model normative aspects of AI systems.

In this paper, we propose a domain-specific language (DSL) designed to simplify the representation and resolution of ethical–legal normative conflicts in AI systems. A domain-specific language (DSL) is designed to express concepts and rules within a narrow application area, offering tailored syntax for that specific context. The proposed DSL allows users to define normative rules (ethical and legal norms) and their conflict resolution strategies in a syntax that is more accessible than raw OWL/SWRL code. The DSL is then automatically translated into formal OWL axioms and SWRL rules, combining the DSL’s ease of use with the rigorous reasoning capabilities provided by Semantic Web formalisms (as demonstrated by prior work using OWL for machine-learned knowledge) [

8]. We hypothesize that this approach can improve the precision of conflict representation and make it easier for interdisciplinary stakeholders (such as AI developers, ethicists, and legal scholars) to contribute to the design of norm-aware AI.

To assess the feasibility of our approach, we developed a prototype DSL capable of representing and resolving normative conflicts, and integrated it into a reasoning pipeline based on OWL and SWRL technologies. The system was applied to a healthcare use case, where it modeled a conflict between ethical obligations (e.g., informed consent) and legal exceptions (e.g., emergency data disclosure). We examined the DSL’s expressiveness and usability in comparison to direct SWRL rule coding, and reflected on its practical strengths and current limitations.

Materials and Methods

Theoretical Background

Normative conflicts have been widely discussed in both ethical theory and legal reasoning. In essence, a normative conflict arises when two norms or principles prescribe incompatible actions under the same circumstances. In simple terms, a normative conflict happens when two rules or principles ask for different actions in the same situation. This kind of problem often appears in the field of AI governance. For example, an AI system might be required to respect ethical values and, at the same time, follow legal obligations. To deal with such situations, traditional methods usually try to set an order or ranking between the rules to decide which one should come first. For example, in law, specific statutes may override general ones (lex specialis), and constitutional norms override lower-level regulations (lex superior). In ethics, frameworks like principlism sometimes rank principles (e.g., prioritizing "do no harm" over "autonomy" in life-threatening situations). Researchers have explored various computational methods for handling conflicting norms. For example, one approach uses semantic heuristics (e.g., leveraging background knowledge bases) to detect and resolve norm conflicts [

9]. This underscores the importance of well-defined strategies for norm conflict resolution, as recent research emphasizes the need to integrate strengths of different reasoning techniques into a unified framework for handling normative conflicts [

10].

To formalize normative rules for AI, many have turned to Semantic Web technologies. OWL (Web Ontology Language) is a W3C-standard language for representing knowledge as ontologies of classes, properties, and individuals. SWRL (Semantic Web Rule Language) extends OWL with if–then style rules that can infer new facts based on ontology content. Using OWL, one can model ethical and legal concepts (for example, defining classes for actions that require consent, or properties indicating an emergency situation). SWRL rules can then express the logic of norms and detect conflicts—e.g., a rule could state "if data is requested and consent is not given, then flag a violation." Prior works have applied OWL and related rule languages for compliance checking of regulations and policies. These studies demonstrate that a reasoner (such as Pellet or HermiT) can automatically check if all conditions of obligations are satisfied or if conflicts (violations) arise under given facts.

However, there are significant limitations to using OWL/SWRL directly for normative conflict resolution. OWL employs an open-world assumption (OWA), which means the absence of information is treated as unknown rather than false. This is problematic in normative contexts because we often need a closed-world interpretation (for instance, if a system has no record of patient consent, we want to assume "consent not given" by default). Workarounds, such as explicitly asserting negative facts or using additional rules, are required to handle this mismatch between legal reasoning (usually closed-world) and OWL's semantics. Moreover, writing complex SWRL rules is challenging for those without expertise in formal logic. The syntax of SWRL and OWL is not very accessible to domain specialists in ethics or law, and rules can become verbose. In many cases, rule-based compliance systems are hard to understand for people who are not technical experts. The syntax is not always easy to read, and it can be difficult to see how the system applies rules or handles conflicts. Because of this, professionals like policy analysts or ethicists may find it hard to check if the OWL or SWRL rules truly match the norms they want to represent. Additionally, full SWRL (which allows unrestricted use of OWL expressions in rules) can lead to undecidable reasoning problems, so systems often must restrict to a safer subset. These difficulties show that although the semantic web gives a strong base for working with rules and meanings, it is still not easy for many people to use. To handle situations where different types of rules apply together, we need better tools that are easier to understand and more reliable in expressing complex ideas.

Domain-Specific Language Approach

One solution to bridge the gap is to introduce a domain-specific language specifically for normative conflict representation. A DSL provides tailored syntax and abstractions aligned with the problem domain. In this context, a normative conflict DSL would allow ethicists and lawyers to write rules in terms of their domain concepts (like "ConsentRequired" or "EmergencyException") without needing to understand OWL classes or SWRL syntax. The DSL can offer constructs to declare norms, specify their type (ethical or legal), set priorities, and define conditions under which one norm overrides another. Such a language raises the level of abstraction: users focus on high-level normative concepts, and the DSL implementation handles the low-level translation to OWL/SWRL. This approach follows a trend in software engineering where raising abstraction improves productivity and correctness. By embedding domain rules into the language design, a well-crafted DSL can prevent many logical errors and inconsistencies that might occur in manual rule writing. Several studies in other domains have shown that DSLs empower domain experts to directly contribute formal rules or configurations. We aim to achieve the same in the AI ethics/legal domain: the DSL should be expressive enough to capture complex normative scenarios, yet simple enough that a graduate-level researcher or practitioner in ethics/law could use it after brief training.

Researchers have started to use domain-specific languages (DSLs) to describe rules for how autonomous systems should behave. For example, Getir Yaman and colleagues developed a DSL called SLEEC to formalize social, legal, ethical, empathetic, and cultural requirements for assistive robots [

11]. This language includes features like an "unless" clause, which allows users to define exceptions to general rules—similar to how our DSL manages conflicts between norms. While their work focuses on supporting safe and respectful behavior in caregiving robots, our approach puts more attention on handling conflicts between ethical and legal rules and uses an ontology-based reasoner. Both studies show that using high-level rule languages can help make AI systems easier to control and more transparent.

Cross-Norm Semantic Reasoning Model Design

Before developing the DSL, we established a baseline semantic model to reason about normative conflicts using OWL and SWRL directly. We created an OWL ontology representing the key entities: for example, our healthcare scenario ontology included classes like Patient and DataRequest, and properties such as hasConsent (a boolean property indicating if a patient's consent exists) and emergencySituation (indicating if the patient is in an emergency). We also defined special outcome classes, namely Violation (to mark a norm violation event) and EmergencyAccessAllowed (to mark the special case where the legal exception applies). Using this ontology, we then wrote SWRL rules to capture the interactions between norms.

For instance, one SWRL rule corresponded to the ethical norm by asserting that a Request should be classified as a Violation if the patient has not given consent and there is no emergency (see Code Listing 1).

Code Listing 1. Example SWRL Rule in Pseudo-Logical Form.

if (Patient ?p consentGiven = false) AND (Request ?r relatedTo ?p) AND (emergencySituation ?p = false), then infer (?r is a Violation).

This rule effectively flags a violation whenever the conditions of the ethical norm are broken. While this approach worked for detecting a breach, handling the legal norm's exception within SWRL was less straightforward. We needed to ensure that no violation would be raised in emergency cases; in the OWL/SWRL model, this meant adding an extra condition to the rule (checking that emergencySituation is false) to prevent it from firing during emergencies. Managing such conditional logic with raw SWRL rules becomes cumbersome as scenarios grow in complexity. There is no easy way to represent the notion of one norm overriding another without manually crafting overlapping rules and carefully ordering their conditions.

This exercise in building a cross-norm reasoning model with OWL/SWRL highlighted the limitations discussed earlier. It reinforced the need for a more structured solution. In particular, expressing the "unless emergency" clause via basic rules was error-prone, since omitting or misplacing a single condition could lead to incorrect inferences. We concluded that a dedicated DSL would allow us to explicitly encode normative priorities and exceptions, rather than implicitly handling them through complex rule configurations. The insights from this OWL/SWRL model informed the design of our DSL, ensuring that the language supports all aspects required to represent and resolve the conflict scenarios.

DSL Design and Implementation

There are several goals for the design of the DSL: (1) Readability – the syntax should be easily understood by experts in ethics and law, who may not be programmers; (2) Expressiveness – it must accurately capture key aspects of normative rules, such as the type of norm (ethical vs. legal), priority levels, and conditional exceptions; (3) Usability – writing and modifying rules in the DSL should be more straightforward than editing raw OWL or SWRL, lowering the barrier for domain experts to participate.

To achieve these goals, we defined a custom syntax for the language. Each norm (ethical or legal regulation) is declared with a name and a block containing its properties. For example, as Code Listing 2 shows two norms defined in the DSL.

Code Listing 2. Example DSL Syntax for Defining Cross-Norm Requirements

norm ConsentRequirement {

type ethical;

priority high;

require "informedConsent(patient)";

}

norm DataDisclosure {

type legal;

priority medium;

allow "emergencySituation(patient)";

}

resolve {

ConsentRequirement overrides DataDisclosure if "emergencySituation(patient)";

}

In this example, ConsentRequirement is an ethical norm with highest priority (1), which requires obtaining informedConsent(patient) (meaning a patient's informed consent must be present). The norm DataDisclosure is a legal norm with lower priority (2), which has a condition emergencySituation(patient). We use requires to denote an obligation that must be fulfilled (for ethical norms) and allow to denote a context under which a legal norm is applicable. In plain terms, the ethical norm says "patient consent is required," and the legal norm says "in an emergency situation, data disclosure is allowed (even without consent)." Priority values (1 and 2 here) indicate the default order of importance when norms conflict (smaller number meaning higher priority in this design).

The DSL also provides a construct to explicitly declare how to resolve conflicts between norms. We introduce a conflict resolution rule syntax that specifies which norm should prevail and under what condition. For instance, in the scenario of the two norms above, we can write like Code Listing 3:

Code Listing 3. Example of conflict resolution rule syntax

ConsentRequirement overrides DataDisclosure if "emergencySituation(patient)";

This declaration means that ConsentRequirement takes precedence over DataDisclosure in general, unless the Emergency Situation (patient) is true. In other words, normally the ethical requirement for consent overrides the legal rule, but if the patient is in an emergency situation, then the legal norm (data disclosure without consent) is allowed to override. This compact representation in the DSL corresponds to the intuitive policy: "Ethical consent is paramount, except in emergencies where legal mandates permit bypassing consent."

We developed the domain-specific language (DSL) using Xtext, a language development framework that supports grammar definition and code generation. With Xtext, we defined the DSL grammar, including structures for norms, priority levels, and conflict resolution rules. The grammar was tested inside the Eclipse IDE (see Code Listing. 4), which provides an editor with syntax highlighting and error checking. The DSL compiler reads input scripts written in our DSL and translates them into OWL ontology elements and SWRL rules. After defining the norms and resolution rules in DSL, the compiler generates OWL-compatible representations. These are then loaded into a Semantic Web environment for reasoning.

Code Listing 4. DSL Grammar Structure for Norm Conflict Representation in Xtext

Model:

norms+=Norm*

resolutions+=Resolution*;

Norm:

'norm' name=ID '{'

'type' type=NormType ';'

'priority' priority=PriorityLevel ';'

(requirement=Requirement)?

(condition=Condition)?

'}'

;

enum NormType:

ethical | legal

;

enum PriorityLevel:

low | medium | high | critical

;

Requirement:

'require' description=STRING ';'

;

Condition:

'allow' description=STRING ';'

;

Resolution:

'resolve' '{'

higher=[Norm] 'overrides' lower=[Norm] ('if' condition=STRING)? ';'

'}'

;

For evaluation, we used Protégé, a popular ontology development platform that supports SWRL rules. It also integrates with OWL reasoners such as Pellet and HermiT. These reasoners perform automated reasoning on the OWL file generated from the DSL. They check for norm violations and conflicts based on the formal rules, priorities, and exception conditions defined in the DSL.

Integration into Reasoning System

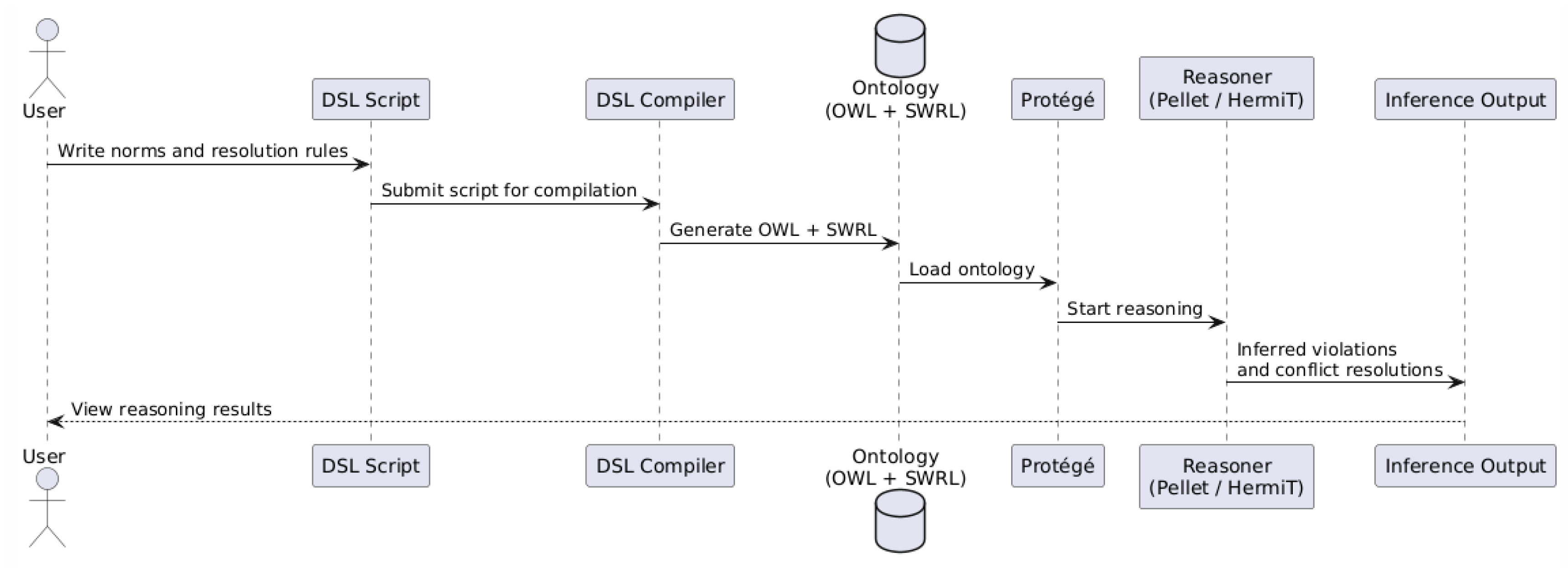

We integrated the DSL-based approach into an existing semantic reasoning workflow (see

Figure 1). The output of the DSL compiler (OWL ontology and SWRL rules) is loaded into a reasoning engine to perform automated conflict detection. In our implementation, we used the Protégé environment to manage the ontology and the Pellet reasoner (a standard OWL DL reasoner) to execute the rules. The reasoner processes the combined knowledge base— including the domain facts and the rules generated from the DSL— to infer when normative conflicts occur and which norm should prevail based on the specified priorities.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the integration. First, the user writes the normative rules using the DSL. Next, the DSL compiler translates these into OWL/SWRL representations. Finally, the OWL reasoner runs with the translated rules to identify any norm violations or exceptions. The reasoner's output can be examined to confirm that the conflict resolution behaves as intended (for example, checking that no violation is reported in an emergency scenario). This integration demonstrates that our DSL can work seamlessly with semantic web tools, allowing for practical deployment in AI systems that rely on ontology-driven decision-making.

Case Study and Evaluation

Given the prevalence of ethical–legal conflicts in healthcare, we chose this domain to demonstrate and examine the DSL’s effectiveness. The scenario involves a medical AI system that must navigate a conflict between an ethical norm and a legal norm. The ethical norm requires obtaining patient consent before accessing or disclosing the patient's data. The legal norm, however, permits data disclosure without consent in an emergency situation (for example, if the patient is unconscious and urgent treatment is needed). This scenario is a realistic example of an ethical vs. legal normative conflict in healthcare. We modeled this scenario using our DSL, as described below.

Scenario Description

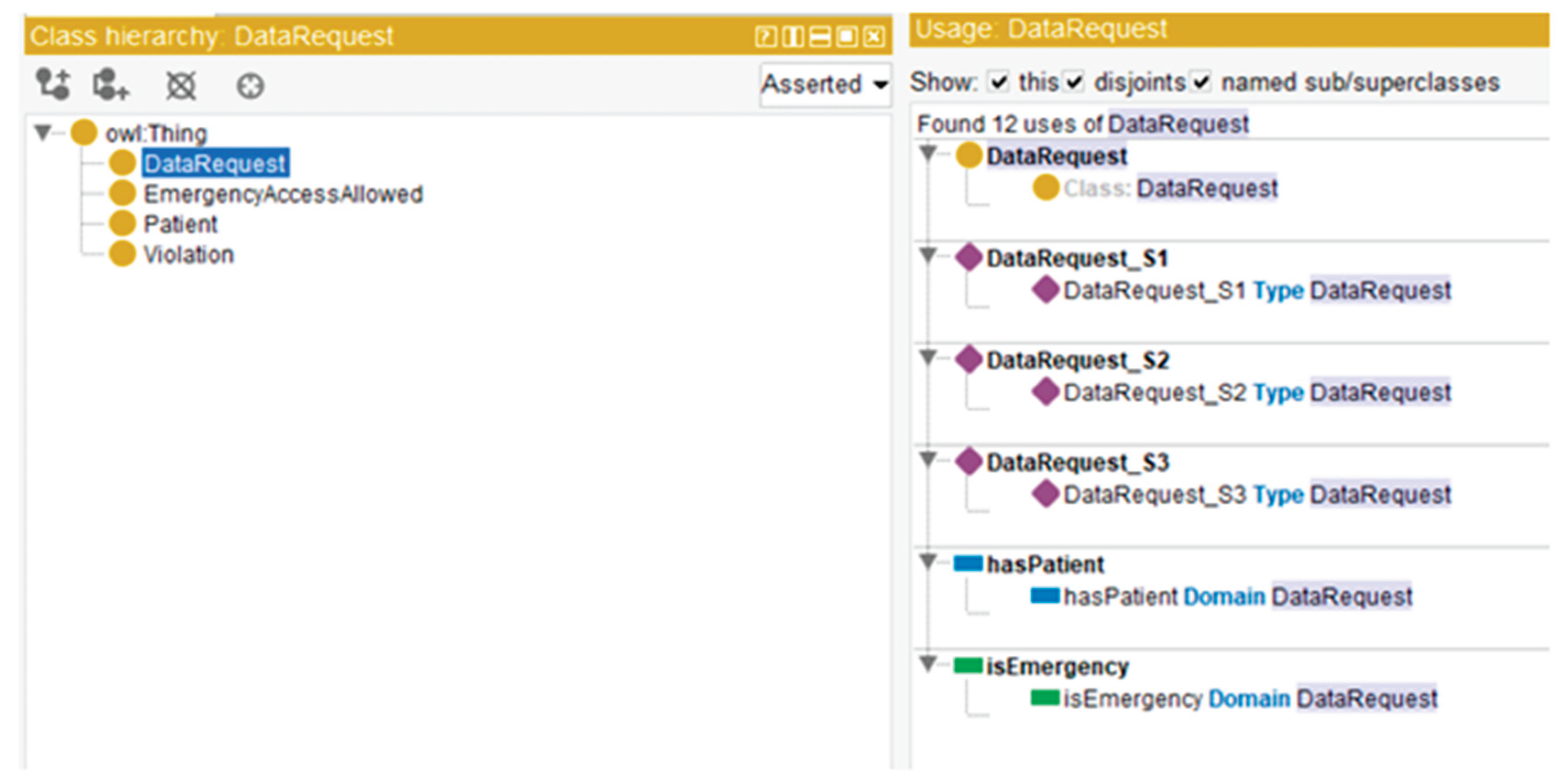

To evaluate the effectiveness of our domain-specific language (DSL) for modeling normative rules, we conducted a case study in the healthcare domain. This case reflects a realistic ethical–legal conflict: a medical AI system needs to decide whether it can access patient data. According to ethical norms, patient consent is always required before accessing sensitive data. However, legal norms often allow exceptions during emergencies—such as when the patient is unconscious and requires urgent treatment. We defined two rules in our DSL. The first is an ethical rule called ConsentRequirement, which states that informed consent is required. The second is a legal rule called DataDisclosure, which allows access in emergencies even if consent is missing. These high-level DSL rules were then translated using our compiler into OWL ontology classes and SWRL rules (

Figure 2). Specifically, we defined the classes Patient and DataRequest, and created two boolean data properties: consentGiven, to indicate whether the patient has given consent, and isEmergency, to indicate whether the situation qualifies as an emergency. To track outcomes, we also defined two output classes: Violation for unethical actions, and EmergencyAccessAllowed for exceptions permitted by law.

We tested the model using three different scenarios, labeled S1, S2, and S3. In each one, we created a Patient and a DataRequest, and assigned appropriate truth values to consentGiven and isEmergency.

In scenario S1, the patient did not give consent, and the situation was not an emergency. According to the ethical rule, access is not allowed in this case, and there is no legal exception (Code Listing 5).

CodeListing 5. Ethical Violation When No Consent and No Emergency

Patient(?p) ^ DataRequest(?req) ^ hasPatient(?req, ?p) ^ consentGiven(?p, "false"^^xsd:boolean) ^ isEmergency(?req, "false"^^xsd:boolean)-> Violation(?req)

This rule tells the reasoner to classify the request as a violation when both consent is missing and no emergency is present. After reasoning, the system correctly inferred that DataRequest_S1 belongs to the Violation class.

In scenario S2, the patient gave consent, and the situation was not an emergency. Here, the ethical requirement is satisfied, and no override condition applies (Code Listing 6).

Code Listing 6. Compliant Access with Consent in Non-Emergency

Patient(?p) ^ DataRequest(?req) ^ hasPatient(?req, ?p) ^ consentGiven(?p, "true"^^xsd:boolean) ^ isEmergency(?req, "false"^^xsd:boolean) -> CompliantRequest(?req)

The system inferred that DataRequest_S2 was compliant with both norms, and no violation was triggered. This outcome serves as a baseline of proper ethical and legal compliance.

In scenario S3, the patient did not give consent, but the request was made in an emergency situation. According to the legal rule, this access is allowed (Code Listing 7).

CodeListing 7. Legal Override in Emergency Without Consent

Patient(?p) ^ DataRequest(?req) ^ hasPatient(?req, ?p) ^ consentGiven(?p, "false"^^xsd:boolean) ^ isEmergency(?req, "true"^^xsd:boolean) -> EmergencyAccessAllowed(?req)

We then tested three representative scenarios (S1, S2, S3) by assigning different truth values to the patient's consent and emergency status.

Table 1 summarizes the conditions and the reasoning outcomes for each scenario, as inferred by the OWL reasoner:

Evaluation of DSL vs. Direct SWRL

We found that using the DSL made it much easier to define and manage the normative rules in our case study. Each scenario could be written in only a few lines of high-level code, which closely followed how a policy expert might naturally describe the situation. Compared to that, writing the same rules directly in OWL and SWRL required much more effort. In the manual approach, we had to explicitly define ontology classes, write formal rule syntax, and handle logic conditions such as exceptions and negations. For example, expressing the “unless emergency” condition in SWRL required careful use of boolean filters and logical structure. In the DSL, this logic was captured more simply using built-in conflict resolution syntax. This saved us time and reduced the chances of making errors.

We also noticed that the DSL improved both readability and maintainability. A domain expert with no background in formal logic could still understand the DSL scripts and follow how different norms interact. If the policy needed to be updated—such as adding a new exception or changing priority between rules—it was much easier to make changes in the DSL than to modify scattered SWRL rules in the ontology. The DSL helps to keep the normative logic centralized and structured.

In terms of performance, our small-scale test showed that the reasoning time was the same whether the rules were written by hand or generated from the DSL. The reasoning engine (HermiT) processed the OWL ontology and SWRL rules without any noticeable difference. The DSL translation step took only a few milliseconds, so there was no delay introduced by using the DSL. This means we gained all the modeling benefits of the DSL without any computational cost.

More importantly, the case study confirmed that the DSL correctly captured the intended behavior. It allowed us to express a situation involving both ethical and legal rules—along with an emergency exception—in a way that was both simple and precise. The reasoning engine correctly inferred violations or exceptions as expected. In short, the DSL made the rule structure easier to write, easier to understand, and just as accurate as hand-coded logic.

Discussion

Our experience developing and testing the DSL revealed several strengths, along with a few limitations. One of the clearest advantages is the DSL’s accessibility for domain experts. Its high-level syntax is close to the way ethicists or legal professionals naturally describe normative rules. This design makes it easier to write rules that are both logically correct and semantically clear, even for users without deep technical backgrounds. Because the DSL is more readable than low-level OWL or SWRL, it helps reduce the risk of misinterpretation. In our tests, each rule's intention was explicitly visible in the DSL code, which made it easier to verify correctness. In addition, the DSL encourages users to think in a structured way: each norm is defined clearly, and conflicts are resolved explicitly using a dedicated resolve block. This improves the internal consistency of the policy specification.

However, like any formal tool, the DSL comes with certain limitations. One challenge is the learning curve. Although the DSL is simpler than traditional semantic web languages, it is still a formal syntax that requires users to learn its grammar and structure. Some training or documentation is necessary for first-time users. In our case study, the DSL scripts were written by researchers familiar with both the domain and the toolchain. But in a real-world deployment, legal professionals or ethicists may need technical support and user-friendly tools to adopt the DSL effectively. This leads to a second concern: maintenance. As laws or organizational norms change over time, the DSL implementation and its supporting toolchain will need updates. Maintaining a custom DSL infrastructure brings an ongoing cost, especially if it is to remain reliable and aligned with new policy requirements.

Another area to consider is integration into real-world AI systems. Our prototype was evaluated on a small, controlled ontology with a limited number of rules. In practical applications, there could be dozens of interrelated norms and a more complex domain ontology. As the number of norms increases, so does the chance of overlapping conflicts. Currently, the DSL handles simple binary conflicts well—cases where one norm overrides another under a specific condition. However, more complex scenarios involving three or more conflicting norms may require additional logic or extensions to the language. There is also a risk of ambiguity if multiple conflict rules apply simultaneously. Without a clear way to define rule precedence, the reasoning outcome may become inconsistent. Ensuring that the DSL compiler and the backend reasoner can handle these situations correctly will be important in future work.

Despite these limitations, we believe the benefits of using a DSL approach outweigh the costs, particularly for domains where normative clarity and correctness are essential. There are also several ways to improve the DSL system further. One promising direction is to develop a graphical interface that allows users to define norms and conflicts visually. For example, a drag-and-drop editor or web-based form could make the DSL easier to adopt, especially for non-technical users. Such a visual interface could help illustrate how different norms relate to each other and how override rules are applied.

Finally, the DSL approach has the potential to be extended to other application domains. Although our work focused on ethical and legal conflicts in healthcare, similar types of normative reasoning appear in other fields. For instance, multi-agent systems often face trade-offs between privacy rules and coordination goals. Organizational policy frameworks may include overlapping procedural, legal, and cultural norms. Adapting the DSL to support new types of norms—such as institutional policies or international regulations—could make it more broadly useful. These directions offer promising opportunities to scale and generalize the DSL framework in future work.

Conclusion

This work introduces a domain-specific language designed to express and resolve normative conflicts that arise at the intersection of ethical values and legal mandates in AI systems. By design, this DSL enables a more direct and intuitive encoding of norms and their priority relationships than was previously possible with raw semantic web languages. The case study in the healthcare domain illustrated that our approach can faithfully capture a realistic ethical–legal conflict (patient consent vs. emergency care) and automatically reason about it to produce outcomes that align with human expectations.

The introduction of the DSL significantly enhances the clarity and precision of cross-norm reasoning. Instead of burying conflict logic in low-level rules, policy designers can articulate the conflict and its resolution in a transparent, high-level manner. The underlying OWL/SWRL reasoning infrastructure then ensures that these specifications are rigorously applied to AI decision-making scenarios. Our evaluation suggests that this approach not only reduces the potential for implementation errors but also makes the normative reasoning process more accessible to interdisciplinary stakeholders. Also, the DSL helps make system updates easier when laws or guidelines change. Instead of rewriting detailed code, we can change the high-level rules, which allows the system to follow new norms without much effort or risk of error.

Although our case study illustrates the DSL's effectiveness in capturing normative logic and simplifying rule authoring, several limitations should be acknowledged. The current evaluation has several limitations. It focuses on a limited set of illustrative examples within a single domain—healthcare—which may constrain the applicability of the results in broader contexts. While a qualitative comparison between DSL and SWRL has been presented, we have not yet conducted quantitative analyses such as measuring rule complexity, development effort, or accuracy. Additionally, the DSL’s usability has not been empirically validated with actual end users from law or ethics domains. Future research should expand the evaluation to include multiple application areas, larger and more diverse rule sets, and structured user studies to assess the system’s practical value and real-world effectiveness.

Overall, our results suggest that a domain-specific language offers a viable solution for handling norm conflicts in AI systems governed by both legal and ethical constraints. It helps connect general ethical and legal ideas with the actual logic that systems can use, by offering a simple and structured way to write those rules. We believe this work can help make AI systems more consistent with both ethical values and legal duties, while also making it easier to manage and update the rules when needed. In the future, we plan to improve the DSL and add more features, so that AI systems can better handle complex situations where many rules apply at the same time.