1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of intensifying global climate change and resource-environmental constraints, advancing sustainable development has become a paramount global mission. In this context, governments worldwide are actively exploring and implementing diverse environmental policies to steer enterprises toward green transformation and sustainable development. To further advance high-quality development goals for a comprehensive green transition of the economy and society, the Chinese government has proposed a coordinated approach. Guided by the “Dual Carbon Goals” (carbon peaking and carbon neutrality)-a cornerstone of its national sustainability strategy—this approach synergizes carbon emissions reduction, pollution control, green initiatives expansion, and economic growth. This approach entails deepening institutional reforms for ecological civilization and strengthening green, low-carbon development mechanisms. As primary actors in the market economy and key contributors to sustainable value creation, enterprises represent the core driving force for achieving high-quality development in a modernized economic system. Simultaneously, enterprises are key stakeholders in realizing pollution and carbon reduction targets. Stringent environmental regulations, while designed to promote environmental sustainability, compel firms to internalize the externalities of environmental pollution, inevitably increasing their operational costs and posing challenges to their economic sustainability.

Common environmental regulations mainly include command-and-control environmental regulations and market-based environmental policies. While carbon trading policies—focused on end-of-pipe emission reduction—are advancing vigorously, the Energy-Use Rights Trading (EURT) policy—targeting front-end energy conservation as a more fundamental approach to sustainable resource use—is being piloted systematically across China. Since 2016, provinces including Zhejiang, Fujian, and Henan have pioneered the pilot implementation of the EURT system. This institutional innovation marks a major shift in China’s front-end energy conservation policies from traditional command-and-control models (e.g., the dual-control targets for energy consumption) toward market-based emission reduction instruments. It aims to resolve the dual dilemma of “energy constraints vs. economic growth” through market mechanisms, seeking a sustainable pathway that harmonizes ecological preservation with economic vitality. Earnings management refers to corporate profit manipulation through accounting policy choices and estimation adjustments, driven by profit maximization or market value management objectives. It primarily encompasses accrual-based manipulation and real-activities manipulation. Such practices directly undermine corporate governance transparency and financial integrity, which are pillars of long-term economic sustainability and investor confidence. The core of the EURT policy lies in front-end control of corporate energy consumption. Within the framework of “rational quota allocation—standardized trading and strict compliance mechanisms,” enterprises may buy or sell energy-use rights quotas to conserve energy or generate revenue. In this process, highly energy-efficiency enterprises may generate surplus quotas, allowing them to sell these for additional income. Enterprises with insufficient quotas must purchase others’ quotas to meet production needs or enhance energy efficiency through innovation and production line upgrades, which may strain short-term financial sustainability. The EURT policy may incentivize R&D investment but simultaneously increases costs (e.g., for avoiding over-consumption penalties), thereby creating motives for earnings management. Such managerial behavior could harm stakeholders’ interests and state tax revenues, while undermining the integrity of corporate sustainability reporting and long-term enterprise value. A critical question arises: While market-based environmental regulations like EURT achieve ecological protection, they also burden enterprises—do firms resort to earnings management in response, thereby compromising governance and economic dimensions of sustainability? Consequently, examining the impact of EURT on corporate earnings management holds significant practical relevance for designing holistic sustainability policies that avoid detrimental side effects.

Existing research primarily focuses on the positive impacts of market-based environmental policies (e.g., EURT and carbon emissions trading (CET)) on macro-level environmental performance—such as reducing regional carbon emission intensity and optimizing energy structures [

1,

2,

3]—to corporate environmental behavior like enhanced green innovation and improved green total-factor energy efficiency [

4,

5,

6]. These studies affirm the instrumental role of such policies in advancing environmental sustainability. However, the impact of environmental policies on sustainability at the micro-enterprise level exhibit complexity and multifaceted dimensions. Rising compliance costs, technological upgrading demands, and potential penalty risks induced by policy implementation may profoundly impact corporate financial conditions and operational decisions, thereby triggering trade-offs between environmental, economic, and governance sustainability.

Notably, how environmental policies—as major external institutional shocks—affect corporate accounting information quality, particularly earnings management behavior, which is a critical aspect of corporate governance (the ‘G’ in ESG) and has not been fully explored. Enterprises’ internal and external environments—such as governmental reforms [

7], green density [

8], the role of independent directors [

9] and debt covenant pressure [

10]—are critical factors influencing their earnings management incentives. Against pervasive information asymmetry and agency conflicts, management may engage in earnings management for diverse motives (e.g., financing needs, risk avoidance). The cost pressures, investment requirements, and compliance risks introduced by the EURT policy are likely to significantly alter firms’ financial incentives and constraints, thereby influencing their motivations and capacity for earnings management. For instance, financing constraints, exacerbated by cost shocks or fund green investments, or the elevated financial risks arising from policy uncertainty, may prompt management to manipulate earnings to embellish financial statements, secure external financing, or circumvent financial distress. This creates a tension between the policy’s environmental objectives and its potential negative on corporate financial transparency.

This study rigorously examines the impact of China’s pilot EURT policy on corporate earnings management and its underlying mechanisms, situating the analysis within the broader discourse on sustainable policy design. Using micro-level data from China’s A-share listed companies, our empirical findings reveal that: (1) following the implementation of the EURT policy, earnings management intensity is significantly higher in pilot-region firms than in non-pilot firms. (2) this effect is more pronounced in private enterprises, non-Big Four-audited firms, firms in highly concentrated industries, and firms located in regions with lower environmental fiscal expenditure and weaker waste gas treatment capacity, highlighting how heterogeneous corporate governance structures and regional institutional capacities influence the sustainability policy outcomes. (3) environmental governance pressure amplifies the policy’s positive effect on earnings management, whereas a high proportion of environmental investment significantly mitigates it, suggesting potential levers for achieving better synergy between environmental and economic sustainability. (4) mechanism analysis confirms that the policy elevates earnings management through dual channels: by intensifying financing constraints and increasing financial risk.

The marginal contributions of this study are threefold: First, it provides innovative research perspectives. Existing literature predominantly focuses on the economic and environmental effects of environmental policies while overlooking their potential impact on accounting information quality. By examining the EURT policy as a significant external shock influencing corporate earnings management, this research enriches the interdisciplinary field that bridges the economic consequences of environmental regulations and micro-level accounting behavior, while also introducing a governance dimension to the assessment of sustainability policies. Second, it provides in-depth mechanistic insights. This study meticulously dissects the specific pathways through which energy-use rights trading induces earnings management, explicitly identifying that the policy intensifies financing constraints and elevates financial risk for firms, thereby significantly altering management’s financial incentives and constraints. This dual effect reinforces their motivation and capacity to engage in earnings management to embellish financial statements, secure financing, or avoid financial distress, revealing the micro-level channels through which sustainability policies can inadvertently strain corporate economic resilience and reporting integrity. Third, it provides rigorous empirical validation. Based on a robust empirical framework, the study offers compelling empirical evidence supporting the theoretical mechanisms above, thereby offering valuable insights for policymakers aiming to refine sustainability instruments to foster truly integrated and robust sustainable development.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Accounting Information Quality and Earnings Management

Corporate accounting information quality plays a crucial role in the efficient functioning of capital markets [

11]. However, moral hazard and information asymmetry inherent in principal-agent relationships create opportunities for management to engage in earnings management [

12]. Earnings management refers to managerial actions that utilize accounting methods or real-activity arrangements to influence financial reporting for specific objectives. Extensive research has identified diverse motivations for earnings management, including: mitigating operating loss pressures [

13], alleviating financing constraint [

14], meeting executive compensation targets [

15], avoiding debt covenant violations [

10], preserving corporate or managerial reputation [

16], and complying with regulatory requirements [

17]. Concurrently, studies demonstrate that high-quality internal control [

18] and effective corporate governance mechanisms [

19], typically curb earnings management and enhance accounting information reliability. Notably, although earnings management may improve reported performance in the short term, it often sacrifices long-term growth potential and undermines shareholder interests [

10], thereby posing a threat to corporate economic sustainability and the integrity of sustainability reporting.

2.2. Environmental Policies and Firm Behavior

As a critical external institutional force affecting corporate operations, environmental policies significantly influence firm behavior. Traditionally, command-and-control environmental regulations dominated policy making. Recently, market-based environmental policies—such as pollution rights trading, CET, and EURT—have gained prominence due to superior economic efficiency. These policies internalize environmental externalities by setting caps on caps and introducing trading mechanisms, incentivizing firms to achieve emission reduction or energy conservation goals through technological innovation, industrial upgrading, or market transactions.

Substantial literature examines the positive impacts of market-based environmental policies on corporate environmental performance and innovation. Well-designed policies like pollution rights trading can spur technological innovation, achieving economic-environmental win_win outcomes and demonstrating the Porter effect in China [

20]. While EURT delivers aggregate Porter effects at the macro level [

21], its firm-level impacts remain uncertain. EURT and CET significantly reduce regional carbon intensity or industrial emissions by optimizing energy structures, upgrading industries, and promoting green innovation [

2]. Specifically, At the firm level, evidence from empirical studies demonstrates that the EURT effectively improves enterprises’ energy efficiency, achieving a dual benefit of economic growth and energy conservation and thereby validating its role in promoting high-quality economic development [

22]. CET primarily stimulates green innovation by providing innovation resources and strengthening incentives [

4], though effects are moderated by local government actions, industry traits, and firm resources. Collectively, these studies depict a positive landscape for market-based policies in advancing corporate green transformation and contributing to environmental sustainability goals.

Beyond environmental outcomes, extant literature also explores how environmental regulations affect earnings management, revealing complex and instrument-dependent effects: command-and-control regulations exhibit divergent effects; and market-incentive regulations generally induce manipulation, as seen with pollution fees [

23], and environmental taxes [

24]. Contrasting this narrative of straightforward inducement, a seminal study on China’s carbon peaking pressure offers a more dynamic perspective, uncovering a significant time-varying effect. This research demonstrates that while regulatory pressure initially increases earnings management due to compliance costs, it fundamentally reverses after a lag, ultimately curbing it as innovation and digital transformation take effect [

25]. This complexity is further echoed in findings that even voluntary regulations can trigger mixed manipulation [

26].

In summary, existing research extensively examines how command-and-control, punitive market-based (e.g., pollution fees/taxes), and voluntary regulations affect earnings management, highlighting the complexity of regulatory tools and mechanisms. However, research focusing on EURT—a novel policy blending market incentives with property rights trading—remains absent. By establishing a tradable energy quota market, EURT offers firms flexible compliance options, fundamentally differing from traditional command-control or punitive instruments. Therefore, investigating EURT’s impact on earnings management not only deepens understanding of environmental regulations’ economic consequences but also extends the micro-level analysis of market-incentive policies to innovative regulatory tools, offering critical insights into the challenges of aligning environmental sustainability with corporate governance integrity.

2.3. Research Gap and Theoretical Linkage

The implementation of environmental policies inherently entails cost burdens. To comply with regulatory requirements, firms must invest resources in technological upgrades, quota purchases, or penalty payments—actions that directly increase operational costs, capital expenditures, and uncertainty. Woerdman et al. (2009) analyze the EU Emissions Trading System, noted potential windfall profits from free quota allocation but implicitly acknowledged that policy costs ultimately shape corporate decisions [

27]. Song and Dong (2024) further demonstrated that environmental policy uncertainty suppresses green investment, an effect amplified by financing constraints [

28]. Collectively, these costs and uncertainties exert material pressure on corporate financial health and short-term economic sustainability.

Although emerging studies have begun to examine the non-environmental impacts of environmental policies—such as Dai and He’s (2025) exploration of carbon trading effects on ESG performance mediated by financing constraints—research directly investigating EURT’s influence on earnings management remains scarce[

5]. Crucially, studies dissecting the transmission mechanisms of financing constraints and financial risk in this process are notably absent.

Building on prior literature, we establish the theoretical linkage: As a binding market-based regulation, EURT’s core mechanism requires firms to bear real or opportunity costs (e.g., purchasing quotas) for energy consumption (especially excess usage) while facing non-compliance penalties (e.g., fines, mandatory quota surrenders). These signals heightened environmental regulatory pressure on management.

Cost Pressure and Financing Constraints: EURT-induced compliance costs (technological upgrades, quota purchases) directly strain operational cash flows, while potentially spurring new green investment needs. Firms may thus increase reliance on external financing to alleviate these pressures [

29]. However, policy uncertainty and risks can simultaneously tighten credit access, exacerbating financing constraints [

25]. Given that financing pressure is a key driver of earnings management [

14], constrained firms have strong incentives to embellish financial statements via earnings manipulation—signaling strength to investors to reduce financing costs or secure funding [

30].

Uncertainty and Financial Risk: EURT introduces new rules (quota allocation, trading, and compliance) and penalties, amplifying operational uncertainty. Fluctuations in compliance costs, quota prices, and potential fines or reputational damage elevate financial risk. Heightened risk may trigger debt covenant clauses, destabilize stock prices, or increase bankruptcy risk. To conceal risk exposure, meet regulatory thresholds, or preserve market confidence, management is incentivized to engage in earnings management to smooth profits or hit financial targets [

31].

Consequently, under dual pressures of performance commitments (e.g., profit targets) and rising compliance costs, managers may exploit accounting discretions or real-activity arrangements to create an illusion of “compliant growth.” This reveals a potential conflict between the immediate pressures of a sustainability policy and the long-term transparency required for sustainable corporate governance. We thus propose:

Hypothesis 1: Following EURT implementation, pilot-region firms exhibit significantly higher earnings management intensity than non-pilot firms.

Hypothesis 2: EURT exacerbates earnings management by intensifying financing constraints.

Hypothesis 3: EURT exacerbates earnings management by elevating financial risk.

3. Research Design

3.1. Baseline Regression Model Specification

To examine the impact of the EURT system on corporate earnings management, we employ a difference-in-differences (DID) approach with the following baseline regression model:

(1)

In the model: represents the level of earnings management for firm in year ;Subscripts denote: subscripts i, j, p, t denote firm, industry, region, and year, respectively. The core variable is defined as , where: equals 1 if firm i is located in region p within an EURT pilot zone, and 0 otherwise; equals 1 for the year of EURT policy implementation (2016) and all subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. denotes a vector of control variables, including firm-level controls and province-level controls where the firm is registered.

3.2. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study utilizes data from China’s A-share listed companies spanning 2010–2022. Sample data are sourced from the CSMAR Database and Wind Financial Terminal, while province-level macroeconomic controls originate from the China Statistical Yearbook and Marketization Index Report of China’s Provinces. To mitigate the influence of outliers, the following data treatments are applied: (1) all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles, (2) firms with negative net assets are excluded, (3) drop financially distressed firms (labeled ST or *ST), (4) financial sector firms are removed, (5) pre-IPO observations are eliminated, (6) samples with missing values for the key variables are dropped. The final sample comprises 22,110 firm-year observations. Descriptive statistics for key variables are presented in

Table 1.

Dependent Variable: Earnings management (

ABS_ACC), measured as nonlinear accrual-based earnings management, calculated following Ball and Shivakumar’s (2005) [

32] approach to estimate discretionary accruals, whose larger absolute value indicates greater earnings manipulation and lower accounting information quality.

(2)

In the model (2), represents the difference between operating profit and net cash flow from operating activities. , and denote firm i’s net operating cash flow in periods , , , respectively. is a dummy variable that equals 1 if , and 0 otherwise. denotes the regression residual (i.e., discretionary accruals), where a larger absolute value indicates greater earnings management and lower accounting information quality. All variables are deflated by lagged total assets to mitigate scale effects.

The policy variable is the core term defined as , where equals 1 if firm is located in region within the EURT pilot zone, and 0 otherwise; equals 1 for the year of EURT implementation (2016) and all subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. According to the Pilot Implementation Plan for the Paid Use and Trading System of Energy-Use Rights issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in 2016, the EURT pilot policy was implemented in Zhejiang, Fujian, Henan, and Sichuan provinces.

Control variables encompass firm-level and province-level factors influencing earnings management. Firm-level controls include: (1) management characteristics (ChairHoldR), (2) ownership concentration (Top10), (3) equity multiplier (EM), (4) debt level (REC), (5) investment level (Invest), (6) corporate tax burden (ITR); Province-level controls include: economic development (GDP) and marketization level (Market).

Table 1 outlines the definitions of the variable. And

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the primary variables. The maximum value of enterprises’ earnings management is 1.69, the minimum value is 0.00, the average value is 0.05, and the standard deviation is 0.056.

4. Empirical Results and Analyses

4.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

Table 3 presents the baseline regression results of Model (1), with firm and year fixed effects controlled in all columns. Column (1) reports estimates excluding control variables and without region/industry fixed effects, Column (2) includes control variables but omits region/industry fixed effects, Column (3) incorporates region and industry fixed effects without control variables, and Column (4) provides the full specification with control variables and region/industry fixed effects. The results consistently exhibit positive and statistically significant coefficients across all specifications, indicating that the EURT system exacerbates corporate financial manipulation. This validates Hypothesis 1: EURT implementation results in significantly higher earnings management intensity in pilot-region firms compared with non-pilot firms. This finding highlights a critical tension, suggesting that while the policy aims to advance environmental sustainability, it may inadvertently trigger challenges in corporate governance. Column (4) is adopted as the baseline result for assessing EURT’s impact on earnings management.

4.2. Robustness Check

4.2.1. Parallel Trends Test

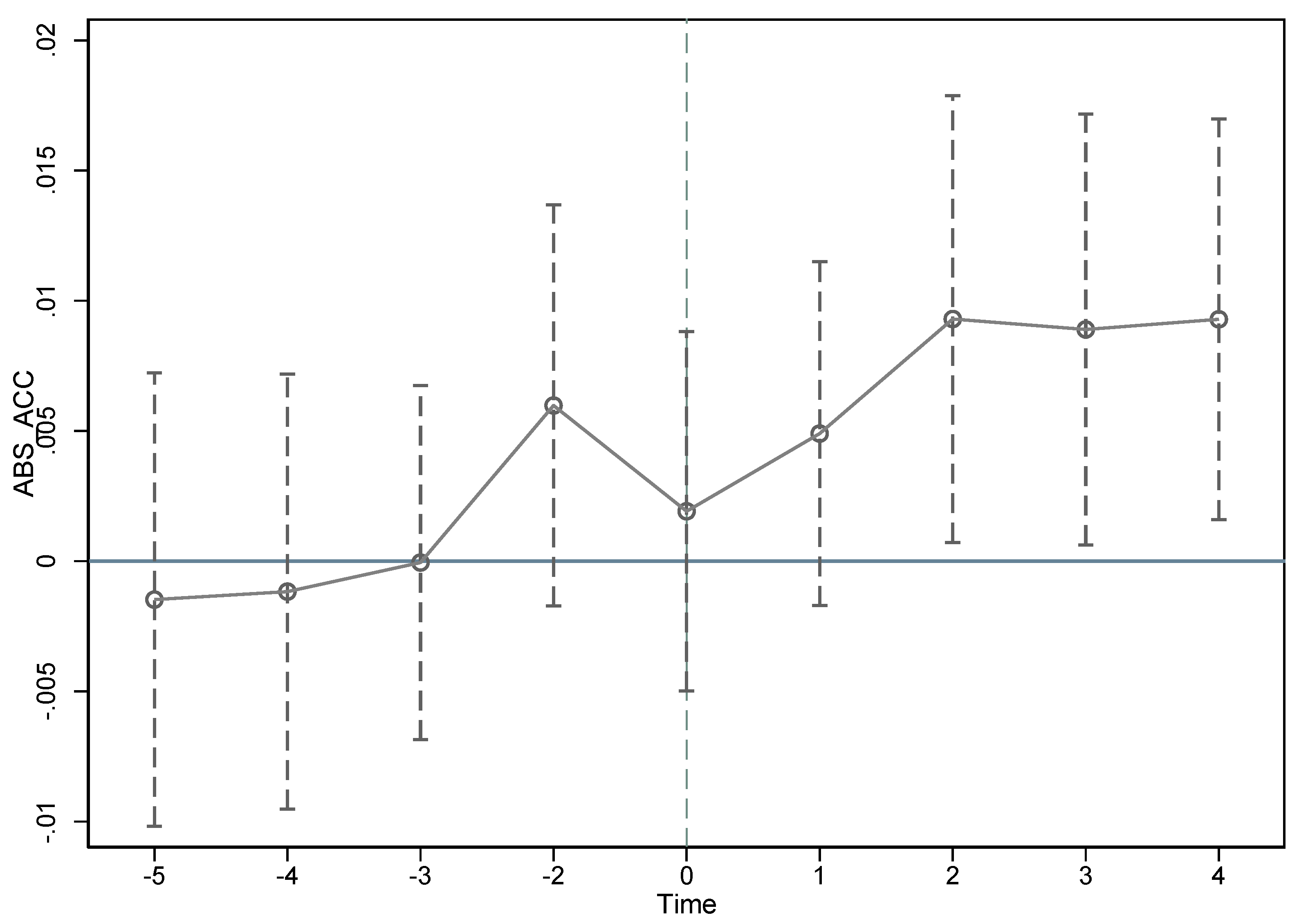

To evaluate the average treatment effect of the EURT policy on corporate earnings management using the DID approach, we rely on the pre-treatment parallel trends assumption. We employ an event-study specification to regress policy effects around the pilot implementation period, explicitly testing whether earnings management trends between pilot and non-pilot firms satisfy parallel trends before policy enactment. Specifically, we estimate the following regression model:

(3)

In this specification, if a firm in pilot region is observed in year t+ω denotes event-time relative to policy implementation, the variable is set to 1 for that year, and 0 otherwise. Here, m and n denote the number of periods before and after the policy implementation year, respectively. Control variables remain identical to those in the baseline regression.

Figure 1 demonstrates that confidence intervals encompass zero and coefficient estimates are statistically insignificant during the pre-policy period, indicating no significant divergence in earnings management trends between pilot and non-pilot firms prior to EURT implementation, thereby validating the parallel trends assumption. Post-policy shock, earnings management behavior among pilot-region firms exhibits a persistently and significantly elevated level starting from the second period onward.

4.2.2. Placebo Test

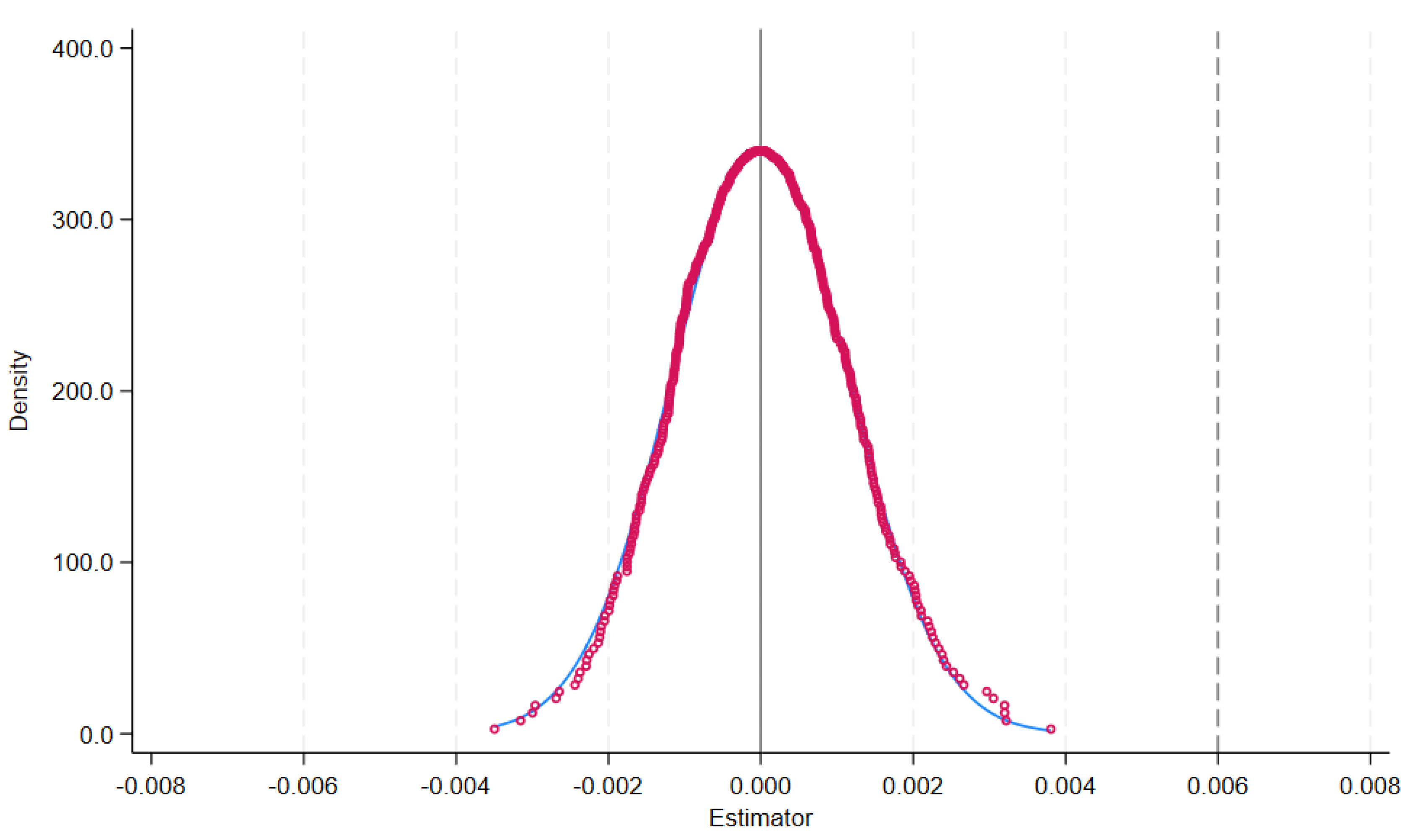

To rule out confounding effects from random policy shocks, we conduct a placebo test by constructing 500 randomized quasi-natural experiments, randomly selecting pilot industries and implementation years for repeated regression analyses.

Figure 2 displays the distribution of the resulting coefficients. The estimates cluster around zero, while the baseline coefficient of 0.006 lies far outside this distribution, confirming that the benchmark result is not coincidental. This placebo test excludes spurious effects from random factors, demonstrating the robustness of our conclusion regarding EURT’s impact on corporate earnings management.

4.2.3. PSM-DID Test

To address potential sample selection bias, we conduct robustness checks using the PSM-DID (propensity score matching-difference in differences) method. Employing kernel matching with control variables as covariates to re-select matched samples, the regression results in Column (1) of

Table 4 show a positive and statistically significant coefficient, closely aligning with the baseline regression findings.

4.2.4. Substitution of the Explanatory Variable (SEV)

To address potential measurement bias in earnings management proxies, we replace the dependent variable with DD_EM—an accruals-based measure following Dechow and Dichev (2002) [

33]. This model regresses working capital accruals against operating cash flows over three consecutive periods, where larger absolute residuals indicate greater earnings manipulation and poorer accounting information quality. Column (2) of

Table 4 confirms the robustness of our results under this alternative specification.

(4)

represents the change in working capital, calculated as: between years and . To mitigate scale effects, all regression variables are deflated by lagged total assets.

4.2.5. Policy Sensitivity

To account for intra-industry correlations, Column (3) of

Table 4 reports results with two-way clustering at industry and firm levels, while Column (4) uses industry-level clustering only. Both specifications yield significantly positive coefficients, consistent with the baseline regression.

4.2.6. Excluding CET Interference

To mitigate confounding effects from parallel CET pilots during the sample period, observations from CET pilot regions (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Hubei, Guangdong, Shenzhen) were excluded. As shown in Column (5) of

Table 4, results remain robustly positive and significant.

4.2.7. DDML Method

To address potential endogeneity and model misspecification, we implement double-debiased machine learning (DDML). Using a partially linear model, control variables are nonparametrically estimated via lasso regression, with core parameters debiased through nine-fold cross-validation. Column (6) of

Table 4 confirms a positive and significant treatment effect, reinforcing baseline reliability.

4.2.8. Oster (2019) Method

To address potential omitted variable bias, we conduct sensitivity analysis following Oster (2019) [

34], calculating the δ-value required to drive the treatment effect β to zero when the R-squared increases to 1.3 times its original value. As reported in

Table 5, δ = −5.19114, indicating that unobservables would need to be 5.19114 times stronger than observables

with opposite sign to nullify the coefficient, confirming robustness. We also compute β’s bounding range under δ=1: the derived β=0.00919 falls within the 99.5% confidence interval of the baseline estimate and excludes zero, demonstrating coefficient stability against omitted variable threats.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Heterogeneity of Business Types

To investigate heterogeneity across firm types, we note systematic differences in environmental compliance costs, regulatory pressure, policy sensitivity, and adjustment capacity between firms with varying pollution intensities.

China’s unique institutional context implies systematic differences between SOEs and non-SOEs in resource access, objective functions, and policy responsiveness. Grouping firms by ownership type (Columns 1–2,

Table 6), we find that EURT induces significantly stronger earnings management in non-SOEs. This stems from SOEs facing stricter audit scrutiny, while non-SOEs resort to “strategic” financial reporting under policy pressure rather than substantive efficiency improvements.

External audit quality—a key governance mechanism—may moderate policy effects [

35]. The “Big Four” auditors (PwC, Deloitte, EY, KPMG) deliver higher-quality audits through superior expertise and independence [

36]. Firms audited by Big Four exhibit greater reporting transparency and face higher violation costs [

36]. We thus partition the sample by Big Four vs. non-Big Four auditors. Columns (3)– (4) in

Table 6 show significantly amplified earnings management effects in non-Big Four-audited firms. Weaker external oversight enables managers to exploit policy-induced opportunities (e.g., trading revenue uncertainty, valuation complexity, subsidy/punishment avoidance) for earnings manipulation. Conversely, the Big Four’s stringent monitoring raises the cost and difficulty of such behavior. Their independence, expertise, and reputational constraints effectively curb opportunistic earnings management, thereby mitigating EURT’s stimulative effect.

Collectively, these findings underscore that the unintended consequence of the sustainability policy is not uniform but is critically mediated by the quality of a firm’s internal and external governance structures. The heightened response observed in non-SOEs and non-Big Four audited firms highlights specific vulnerabilities within the corporate ecosystem that can undermine the policy’s overall effectiveness and the integrity of sustainable development outcomes.

4.3.2. Heterogeneity of Business Types

To examine heterogeneity in industry positioning, we acknowledge that firms operate under vastly different market structures and competitive environments, where uniform policy effects may mask heterogeneous responses. Particularly between firms in industries with varying concentration levels, systematic differences exist in market power, cost-pass-through capability, and strategies for coping with policy pressures. Thus, using the median Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) as the threshold, we split the sample into high-concentration and low-concentration industry groups for subgroup analysis. Columns (1)– (2) in

Table 7 reveal a significantly stronger stimulative effect on earnings management in high-concentration industries. This effect likely occurs because firms in concentrated markets, leveraging greater market power and bargaining power, can more easily circumvent policy costs—thereby increasing earnings management incentives—whereas firms in competitive industries face compressed manipulation space due to resource constraints and competitive pressure. This finding reveals an important nuance loophole: market structures that reduce competitive pressure can inadvertently weaken the substantive effectiveness of sustainability policies by enabling strategic financial reporting instead of genuine green innovation, thereby hindering the necessary transition towards sustainable industrial production.

4.3.3. Regional Heterogeneity

To deepen our understanding of the heterogeneous impact of the EURT policy on corporate earnings management and explore underlying mechanisms, we further examine regional heterogeneity in environmental governance characteristics. First, considering how local governments’ varying emphasis on environmental governance and resource allocation shape policy effectiveness, we proxy regional environmental investment intensity using the ratio of provincial environmental protection expenditure to general public budget expenditure. Splitting the sample at the median into “high environmental expenditure regions” and “low environmental expenditure regions,” Columns (1)– (2) in

Table 8 reveal a significantly stronger stimulative effect on earnings management in low-expenditure regions. This finding occurs because governments in these regions face constrained regulatory capacity, leading to laxer oversight of corporate environmental behavior. Consequently, firms gain greater latitude to engage in earnings management to circumvent EURT-induced costs or embellish performance. Conversely, stricter monitoring in high-expenditure regions suppresses such manipulation.

Second, to identify boundary conditions and mechanisms, we investigate heterogeneity in regional waste treatment infrastructure capacity, a key indicator of regulatory enforcement efficiency and end-of-pipe governance capability. Using the number of provincial waste treatment facilities as a proxy, we partition the sample into “low-capacity regions” and “high-capacity regions” (median split). Columns (3)– (4) in

Table 8 demonstrate a significant increase in earnings management only for firms in low-capacity regions. Scarce treatment resources reduce the credibility of enforcement and implementation efficacy. Firms perceive lower violation costs and greater operational flexibility, making earnings management a “low-cost, low-risk” strategic response to EURT compliance pressures, thereby channeling policy costs into accounting manipulation incentives.

These regional disparities underscore that the efficacy of a national sustainability strategy is not solely determined by its design but is critically contingent on local institutional capacity and financial commitment. Weak regional governance ecosystems can inadvertently subvert the policy’s intent, allowing financial manipulation to supplant substantive environmental compliance.

5. Further Research

5.1. EURT Policy, Environmental Governance Pressure, and Earnings Management

To examine the role of firm-perceived environmental governance pressure (pressure), we introduce an interaction term policy_enpressure (EURT policy × environmental pressure) into the regression model. Environmental pressure is derived from listed firms’ financial reports using text analysis. Column (1) of

Table 9 shows positive coefficients for policy and policy_pressure, indicating that higher environmental governance pressure significantly amplifies EURT’s stimulative effect on earnings management. When firms face heightened pressure (e.g., stringent regulations, public scrutiny, or penalty risks), compliance burdens and operational costs increase. Superimposed with EURT, this “dual regulatory burden” incentivizes earnings management to mitigate financial strain, avoid profit declines, or stock volatility. Environmental pressure reflects stronger societal expectations, prompting firms to prioritize short-term financial “compliance” over sustainable improvements. Although EURT provides direct financial incentives, environmental pressure magnifies motives to evade substantive energy conservation. This “dual regulatory burden” highlights a significant friction within the sustainability transition: well-intentioned but overlapping pressures can force firms to prioritize short-term financial survival over long-term, substantive environmental improvements.

5.2. EURT Policy, Environmental Investment, and Earnings Management

As shown in the baseline regression, EURT implementation significantly increases earnings management—confirming unintended negative incentives alongside emission reduction goals. To investigate how environmental investment mediates this process, we introduce an interaction term policy_eninvest (EURT policy × environmental investment ratio), where eninvest is measured as environmental asset investment divided by total assets.

Column (2) of

Table 9 reveals a significantly negative coefficient for policy_eninvest, demonstrating that post-EURT environmental investment suppresses the policy’s positive effect on earnings management. This contrasts sharply with the standalone positive effect of policy, highlighting environmental investment’s role as a negative moderator that buffers adverse policy impacts. Environmental investment enables substantive emission reduction (e.g., upgrading equipment, adopting clean technology), allowing firms to directly meet EURT requirements, reduce the need for additional quotas, generate revenue by selling surplus quotas, and diminish incentives for earnings management to window-dress performance or offset compliance costs. By providing an authentic compliance pathway, environmental investment lowers violation risks (fines, reputational loss) through efficient energy management; generates long-term cost savings/new revenue, alleviating short-term financial pressure; and signals sustainability commitment to stakeholders, enhancing reputation and reducing motives for short-term manipulation.

Column (2) of

Table 9 reveals a significantly negative coefficient for policy_eninvest, clearly indicating that post-EURT environmental investment significantly weakens the policy’s positive stimulative effect on earnings management. This finding contrasts sharply with the standalone positive effect of policy in the baseline regression, demonstrating that environmental investment acts not merely as a correlated outcome but as a key negative moderator, buffering or suppressing the policy’s adverse impact on earnings management. Environmental investment represents substantive emission-reduction actions (e.g., upgrading energy-efficient equipment, optimizing production processes, adopting clean technologies). By achieving real energy savings, firms can more directly comply with EURT requirements, reducing the need to purchase additional quotas or generating revenue from surplus quota sales. This reduction fundamentally diminishes incentives and the necessity for earnings management aimed at window-dressing financial performance to offset compliance costs or maintain market image. Environmental investment provides an “authentic compliance pathway”—enabling firms to meet regulations while enhancing value.

Such investment helps firms manage energy consumption more effectively, directly lowering risks of fines, penalties, or reputational damage from quota violations (i.e., compliance pressure). Though environmental investment incurs costs, effective initiatives yield long-term energy cost savings (e.g., reduced consumption) or new revenue streams (e.g., surplus quota sales), alleviating short-term financial pressure. As earnings management typically serves as a short-term coping mechanism, its appeal naturally diminishes with increased substantive investment. Furthermore, proactive environmental investment signals corporate commitment to sustainability to stakeholders (investors, regulators, consumers), enhancing reputation and long-term value. This reduces motives for short-term financial manipulation to sustain stock prices or profits, steering management toward strategies focused on genuine long-term value. This finding is pivotal, as it identifies environmental investment not merely as a cost, but as a strategic lever that can resolve the tension between environmental mandates and financial integrity. It demonstrates a viable mechanism for achieving the “win-win” scenario of simultaneous environmental and economic sustainability, which is the cornerstone of effective green governance.

5.3. EURT Policy, Financing Constraints, and Earnings Management

The baseline results confirm that EURT significantly increases earnings management. To investigate underlying transmission mechanisms, we examine the critical role of financing constraints. Using the SA index [

37] as a proxy (higher absolute values indicate tighter constraints), we first assess EURT’s direct impact on financing constraints. Column (1) of

Table 10 shows that the policy significantly intensifies financing constraints, confirming that compliance costs or regulatory risks worsen firms’ external financing conditions. Further incorporating financing constraints into the baseline model (Column 2), results verify that “tightened financing constraints” mediate EURT’s effect on earnings management. Theoretically, EURT-induced costs (quota purchases, green investments) or regulatory signals heighten investor concerns about operational risks, elevating financing costs. Firms facing such constraints resort to earnings management to embellish statements, reduce information asymmetry, or meet financing thresholds. This pathway underscores a critical challenge for sustainable transitions: policies aimed at environmental goals can inadvertently strain a firm’s financial viability, creating a trade-off where economic pressures undermine governance integrity. Thus, alleviating policy-driven financing constraints may mitigate its adverse effects.

5.4. EURT Policy, Financial Risk, and Earnings Management

EURT’s positive stimulative effect on earnings management suggests firms adjust reporting strategies in response to this new regulatory pressure. Theoretically, EURT imposes additional quota costs or energy-saving investments, increasing operational burdens and cash flow pressures. Heightened financial risk amplifies earnings management incentives. Following MinhNguyen et al. (2024) and Ohlson (1980) [

38,

39], we measure financial risk using the OScore (higher values indicate greater risk). Column (3) of

Table 10 confirms that EURT significantly elevates financial risk because compliance costs and investment pressures translate into tangible financial burdens. Column (4) demonstrates that rising financial risk drives earnings management, as pressured firms manipulate earnings to mitigate distress. This mechanism highlights how the financial instability induced by environmental compliance can compromise the transparency and accountability that underpin sustainable corporate governance. Thus, financial risk constitutes a key transmission channel, indicating that market-based environmental policies, if poorly designed, may unintentionally distort financial reporting by exacerbating corporate financial strain.

6. Conclusions

Empirical analysis of the EURT policy’s impact reveals that it significantly stimulates corporate earnings management. This effect is markedly pronounced in private enterprises, non-Big Four-audited firms, firms operating in highly concentrated industries, and firms located in regions with lower environmental fiscal expenditure or weaker waste treatment capacity. While heightened environmental governance pressure amplifies the policy’s stimulative effect on earnings management, substantive environmental investment mitigates it. Further, the policy exacerbates financing constraints and elevates financial risk for pilot-region firms, with both channels mediating its impact on earnings management. These findings offer critical policy insights for designing more robust and sustainable environmental governance systems:

First, when implementing market-based environmental policies like EURT, policymakers must vigilantly address potential unintended financial behaviors (e.g., earnings management), particularly among firms with weak corporate governance and external oversight. Strengthening external monitoring mechanisms—especially enhancing audit quality—is essential not only for policy efficacy but also for upholding the integrity of corporate sustainability reporting and ensuring market fairness. Regulators should incentivize or mandate high-energy or high-emission firms to engage premium auditors and intensify scrutiny of audit processes to minimize moral hazard and opportunistic behavior.

Second, the deployment of EURT must account for its direct financial impact on firms. Complementary measures—such as optimizing quota allocation, providing transitional financial support, or introducing risk mitigation tools—should be implemented to alleviate corporate financial strain. This approach helps secure a firm’s economic sustainability through the green transition, ensuring that resources are channeled into genuine energy-saving innovation rather than financial manipulation.

Ultimately, this study underscores that the success of a sustainability policy hinges on its ability to harmonize environmental objectives with economic and governance realities. A holistic policy design that integrates environmental targets with supports for financial resilience and governance integrity is crucial for achieving truly sustainable outcomes.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Jingjing Zhang; software, Jingjing Zhang; validation, Jingjing Zhang; formal analysis, Jingjing Zhang and Senping Yang; writing—original draft preparation, Jingjing Zhang and Qingjun Liu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Y.; Zhong, B.; Guo, B. Does energy-consuming right trading policy achieve a low-carbon transition of the energy structure? A quasi-natural experiment from China. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Lin, P.; Hou, C.; Jia, S. Study of the Effect of China’s Emissions Trading Scheme on Promoting Regional Industrial Carbon Emission Reduction. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Bao, X. Corporate financing constraints and environmental information disclosure hype. International Review of Economics & Finance 2025, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wan, Z.; Zeng, H.; Wu, Q. How Does Low-Carbon Financial Policy Affect Corporate Green Innovation?—Re-Examination of Institutional Characteristics, Influence Mechanisms, and Local Government Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; He, R. The Impact of Carbon Emissions Trading Policy on the ESG Performance of Heavy-Polluting Enterprises: The Mediating Role of Green Technological Innovation and Financing Constraints. Sustainability 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, P.; Hao, Y.; Dagestani, A.A. Tax incentives and green innovation-The mediating role of financing constraints and the moderating role of subsidies. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, R.; Coronella, L.; Mechelli, A. Governmental reforms and earnings management: examining their influence during a crisis. Management Decision 2025, 63, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, H.; Karim, M.A.; Sarkar, S.; Spieler, A.C. Green density and spillover effects on earnings management. International Review of Economics and Finance 2025, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-T.; Lee, C.-F.; Lin, C.-Y.; Tang, N. Lead independent director and earnings management. European Financial Management 2024, 30, 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyreng, S.D.; Hillegeist, S.A.; Penalva, F. Earnings Management to Avoid Debt Covenant Violations and Future Performance. European Accounting Review 2022, 31, 311–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting & Economics 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, R.G.; Sohn, M.; Tanner, C.; Wagner, A.F. Earnings Management and the Role of Moral Values in Investing. European Accounting Review 2025, 34, 841–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carla; Hayn. The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Kurt, A.C. How Do Financial Constraints Relate to Financial Reporting Quality? Evidence from Seasoned Equity Offerings. European Accounting Review 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B. Executive compensation and earnings management under moral hazard. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 2014, 41, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, S. Experienced Executives’ Views of the Effects of R&D Capitalization on Reputation-Driven Real Earnings Management: A Replication of Survey Data from Seybert (2010). Behavioral Research in Accounting 2016, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Tian, G.; Wu, Y. Does Media Tone Influence Pre-IPO Earnings Management? Evidence from IPO Approval Regulation in China. Abacus 2024, 61, 377–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Han, Y. Supervisory board, internal control quality, and earnings management. Finance Research Letters 2025, 77, 107083–107083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, B.; Gulati, R. Quality of financial reporting in the Indian insurance industry: Does corporate governance matter? Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance (Wiley) 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, C.; Xie, R. Structural, Innovation and Efficiency Effects of Environmental Regulation: Evidence from China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot. Environmental & Resource Economics 2020, 75, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BingnanGuo; PeijiHu. Investigating the relationship between energy-consuming rights trading and urban innovation quality. Sustainable Development 2023, 32, 3248–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaobo, Z.; Yuankun, L.; Chaoyu, W. Can the energy-consuming right transaction system improve energy efficiency of enterprises? New insights from China. Energy Efficiency 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Qu, X.; Yin, S. How does carbon emissions trading policy affect accrued earnings management in corporations? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Yuan, J.; Xiao, D.; Chen, Z.; Yang, G. Research on environmental regulation, environmental protection tax, and earnings management. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 2023; Volume 11 - 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, J. Carbon peaking pressure and corporate earnings management. International Review of Economics and Finance 2025, 103, 104503–104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tian, Y. The Unintended Consequence of Environmental Regulations on Earnings Management: Evidence from Emissions Trading Scheme in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7092–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerdman, E.; Couwenberg, O.; Nentjes, A. Energy prices and emissions trading: windfall profits from grandfathering? European Journal of Law and Economics 2009, 28, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Dong, J. Impact of climate policy uncertainty on corporate green investment: examining the moderating role of financing constraints. Frontiers in Marine Science 2024, 11, 1456079–1456079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Dang, V.; NingGao; TianchengYu. Environmental Regulation and Access to Credit. British Journal of Management 2024, 36, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Alam, N.; Uddin, M.R.; Jones, S. Real earnings management and debt choice. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money 2024, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jintao, Z.; Taoyong, S.; Li, M. Corporate earnings management strategy under environmental regulation: Evidence from China. International Review of Economics and Finance 2024, 90, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAY, B.; LAKSHMANAN, S. The Role of Accruals in Asymmetrically Timely Gain and Loss Recognition:loss recognition role of accruals. Journal of Accounting Research 2006, 44, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.M.; Dichev, I.D. The Quality of Accruals and Earnings: The Role of Accrual Estimation Errors. The Accounting Review 2002, 77, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadab, M.; Clacher, I. The impact of audit quality on real and accrual earnings management around IPOs. The British Accounting Review 2018, 50, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.R.; Yu, M.D. Big 4 Office Size and Audit Quality. The Accounting Review 2009, 84, 1521–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New Evidence on Measuring Financial Constraints: Moving Beyond the KZ Index. Review of Financial Studies 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MinhNguyen; BangNguyen; LýLiêu, M. Corporate financial distress prediction in a transition economy. Journal of Forecasting 2024, 43, 3128–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OHLSON, J.A. Financial Ratios and the Probabilistic Prediction of Bankruptcy. Journal of Accounting Research 1980, 18, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).