Introduction

The MELK gene is a part of the Snf1/AMPK of serine/threonine kinase family. MELK cDNA was initially cloned in 1997

, and was initially recognized through its expression among several early embryonic cellular stages [

1,

2]. This initial finding implicated MELK in essential developmental processes, including embryogenesis and cell cycle regulation [

3]. Additionally, it serves as a multifunctional kinase, participating in various biological and cellular processes. These functions include the stringent regulation of cell cycle progression [

4], enhancement of cell proliferation [

3], enhancement of mitosis [

5], modulation of apoptosis [

3,

6], promotion of cell migration [

7], and support for cell renewal [

4]. Furthermore, MELK plays a role in the cancer cells ' survival, growth, invasion, metastasis, and the regulation of the tumor microenvironment[

5]. The extensive body of research has reported elevated MELK levels across various cancer types, with MELK overexpression frequently correlating with unfavorable prognostic outcomes and promoting tumorigenesis by inhibiting apoptosis[

6,

7]. Therefore, one can envision that MELK knockdown or inhibition may induce apoptosis and disrupt cancer cell proliferation [

8]. Indeed, it has been shown that the knockdown of MELK enhances the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiotherapy[

8,

9,[8,9,]. However, few studies have opposed the findings regarding the MELK gene's involvement in cancer [

10,

11,

12].

Therefore, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of MELK's role in key functions, including proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, and oncogenesis, as well as the role and therapeutic implications of MELK inhibitors. Finally, the contrasting viewpoints concerning MELK's involvement in cancer proliferation and the potential of MELK inhibitors to impede cancer cell growth.

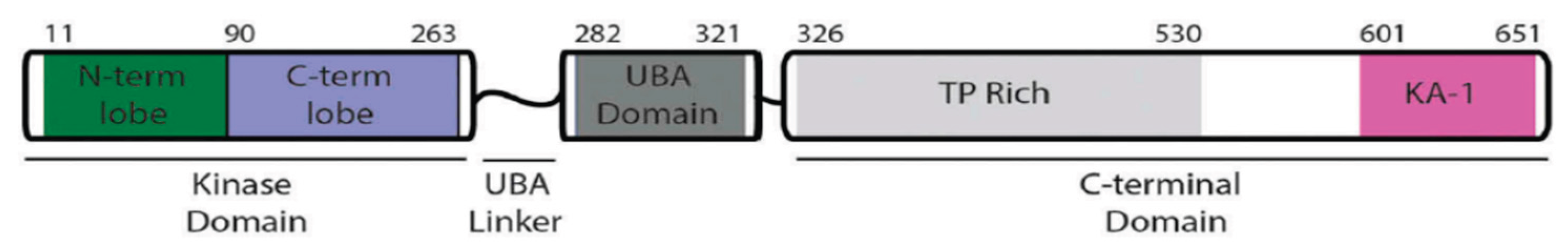

Structure of MELK

MELK is located on chromosome 9p13.2. The gene sequence comprises 2,501 base pairs and includes 22 exons, encoding 651 amino acids that result in a 70 kDa protein [

1,

2]. MELK is very similar across species, from humans to

C. elegans, and the crystal structure of a human MELK fragment comprises three distinct domains (

Figure 1). The N-terminal Ser/Thr kinase domain, ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain, and C-terminal regulatory region [

1,

13]. The N-terminal Ser/Thr kinase domain is a catalytic domain with kinase activity and phosphorylates target proteins at their serine or threonine residues, then modifies different cellular processes[

1,

14]. The C-terminal regulatory domain serves as a regulatory domain, and the structure consists of a segment rich in proline and threonine (TP-rich) and a kinase-associated segment (KA1)[

1,

13]. The C-terminal KA1 domain has been identified as auto-inhibitory, capable of interacting and controlling the N-terminal of the AMPK-related kinases[

1]. Furthermore, it has a function in membrane association by binding to acidic phospholipids like phosphatidylserine, and this placement lets kinases interact with substrates or signaling complexes that are also in the membrane[

15,

16]. The Ubiquitin-Associated (UBA) domain of MELK is a key regulatory part that is positioned right next to the N-terminal Ser/Thr kinase domain. It is known that classical UBA domains bind to ubiquitin; however, the UBA domain in MELK (and other AMPK-related kinases) lacks this property and does not bind to ubiquitin very well. Instead, its main job is to control the kinase domain's catalytic activity and make sure it is in the right shape[

13,

17]. Additionally, it is shown that eliminating the UBA domain from MELK makes the enzyme inactive. This indicates that the UBA domain is not just a regulatory element; it is also essential for MELK's catalytic activity to be expressed[

1].

Role of MELK in the Cell Cycle and Apoptosis

MELK is expressed in several types of tissues through different mechanisms [

19]. Mostly in proliferative cells, like in developing embryos, spermatogonia, and oocytes [

20,

21]. During these stages, MELK expression is tightly regulated, indicating its critical role in determining cell fate and differentiation[

22]. The expression of MELK is significantly associated with the cell cycle. Throughout the cell cycle, there are fluctuations in the level of MELK mRNA and protein. Levels peak during the G2/M phases and subsequently decrease upon cell division[

9]. The expression of MELK is strongly associated with mitotic activity in human cancers, which indicates that it is an indirect marker of rapid cell division. This correlation is much stronger because its expression is low in organs that don't grow and high in dividing tissues, and it is also linked to well-known proliferation markers, like MKI67 (a nuclear protein widely used as an indication of cell proliferation)[

12].

MELK serves a crucial role in cellular proliferation by promoting the G1/S transition in the cell cycle[

23]. This is achieved through the regulation of gene transcription, which is essential for the cell cycle, particularly those involved in the transition from G1 to S phase. Excessive MELK has been demonstrated to increase the production of cyclin D1 and CDK4, which are essential for the cell's transition from the G1 phase to the S phase and the initiation of DNA replication. Conversely, inhibiting MELK prevents cell division and transitions from G1 to S phase by decreasing the levels of cyclin E1 and cyclin D1[

23,

24]. Furthermore, MELK similarly influences the ATM/CHK2/p53 pathway during the G1/S transition. MELK inhibition activates this pathway, resulting in the cessation of the cell cycle at the G1/S phase. Regulation of the MELK can activate p53 and p21 downstream, thus effectively inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity and transcription factors (E2Fs), which are essential for DNA replication during the G1/S phase[

23]. However, the interaction between MELK and p53 is complicated. MELK is reported to phosphorylate Ser15 in the amino-terminal transactivation domain of p53, thus inhibiting the G1/S phase transition. This phosphorylation enhances the stability and activity of p53, potentially leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, depending on the p53 status[

5]. This apparent contradiction suggests that MELK's role in regulating p53 is context-dependent. In certain cancer situations or when cells are under significant stress, MELK may activate p53 to induce apoptosis or halt the cell cycle as a protective mechanism. However, in other cases, such as when MELK is overexpressed, which frequently occurs in various malignancies, its primary function may shift towards promoting growth and facilitating the G1/S transition. This shift can occur by bypassing p53-mediated checkpoints or by engaging alternative pathways that counteract the effects of p53[

3,

5,

25]. This illustrates the complexity of MELK's signaling network; the effect of this factor on promoting or inhibiting is an ongoing area of research, with evidence supporting both functions. This demands further investigation into its role in apoptosis.

Additionally, MELK is pivotal in activating Forkhead Box M1 (FOXM1), a critical transcriptional and carcinogenic factor that controls the expression of numerous mitotic transcription factors[

3,

26]. Expression of FOXM1 is upregulated in various cancer types, including breast, liver, prostate, brain, lung, colon, and pancreatic cancers[

26,

27]. The activation of the MELK-FOXM1 axis increases the transcription of EZH2, which in turn inhibits the transcription of differentiation genes, thereby promoting cancer cells in preserving their stem-like properties[

28]. Additionally, MELK interacts with other critical transcription factors, including c-JUN[

19], E2F1[

29], protein tyrosine phosphatase(CDC25B)[

30], zinc finger protein analog (ZPR9), nuclear inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatase-1 (NIPP1), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), signal transduction Smad protein, apoptosis signal-regulated kinase 1 (ASK1), and pro-apoptotic gene Bcl-G[

31].

Role of MELK in Tumors

Breast Cancer

The second-highest mortality of female cancer patients is breast cancer, which also happens to be the most frequently diagnosed malignancy overall among females [

32] According to gene expression profiling, conventional breast cancer classifications, which relied on pathological evaluation, have been reorganized into HER2, basal-like, luminal A, and luminal B subtypes [

33]. The "Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)" and the "Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)" research studies identified multiple critical genes, one of which is MELK, contributing to breast cancer susceptibility [

34,

35]. Breast cancer tissue consistently exhibits elevated MELK expression levels relative to normal mammary gland tissue [

18]. MELK is usually expressed in mammary glands; however, its activity is significantly heightened in dividing cells and those exhibiting characteristics of mammary progenitors [

36]. In cancer, however, its expression becomes dysregulated and significantly increases, particularly in poorly differentiated and aggressive forms of the cancer. Research has repeatedly demonstrated that MELK mRNA levels are elevated in malignant tissues compared to normal tissues. In samples of breast, colon, ovarian, and lung tumors, levels were observed to be 5 to 50 times elevated[

18,

36].

MELK demonstrates a notable and distinct increase in specific subtypes of breast cancer. In Basal-like Breast Cancer (BLBC) and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), expression levels are notably elevated [

37,

38]. MELK mRNA expression is consistently elevated in BLBC compared to luminal or other breast tumor subtypes, identifying it as the primary molecular subtype of TNBC and BLBC [

9,

37]. Additionally, a poor prognosis in breast cancer is correlated with increased MELK expression, which is also linked to cancer spread, tumor angiogenesis, and cancer cell resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy[

9,

30,

39]. In patients with TNBC, elevated MELK expression correlates with an unfavorable prognosis and resistance to radiotherapy, both

in vitro and

in vivo. Furthermore, the deletion of MELK markedly suppresses the growth of TNBC[

40,

41,

42]. MELK knockdown by (sh)RNA interference preferentially reduced BLBC cell proliferation and induced apoptosis [

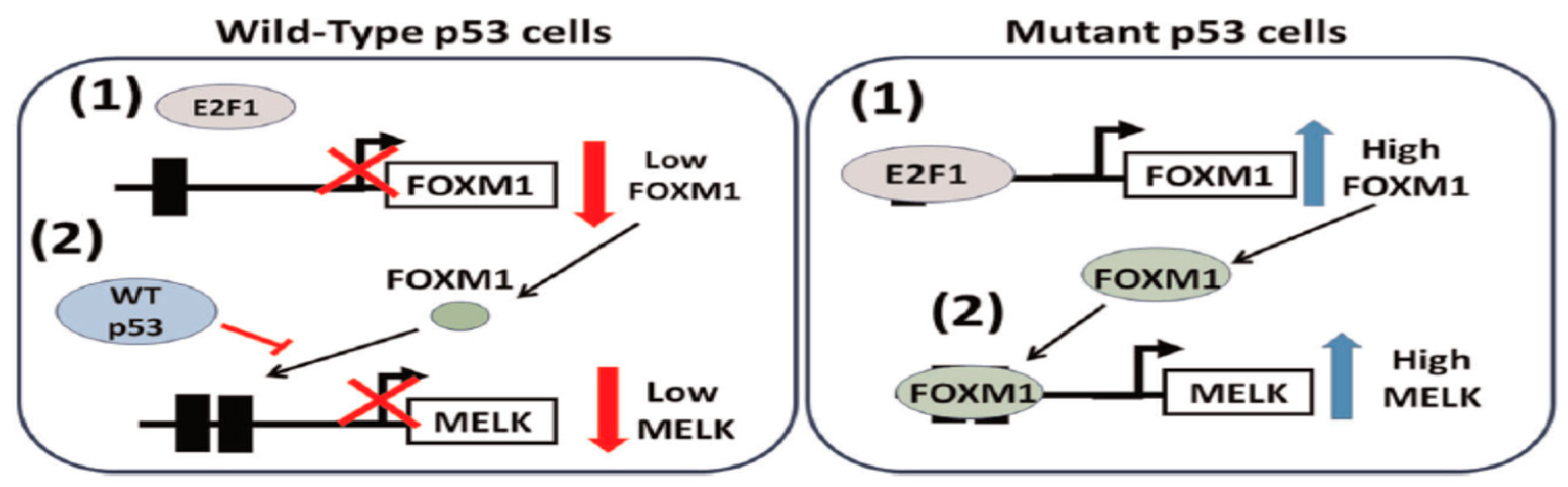

9]. Furthermore, the functional state of the tumor suppressor protein p53 is crucial for regulating MELK. The lack of wild-type p53 activity leads to an increase in MELK levels in p53-mutant breast tumors. Under typical physiological settings, wild-type p53 inhibits MELK expression by inhibiting the E2F1A-dependent transcription of FOXM1, thereby suppressing MELK expression(

Figure 2)[

43]. Nevertheless, Mutated p53 failed to inhibit the expression of FOXM1 and MELK, thereby promoting tumor development in TNBCs. This suggests that mutant p53 is responsible for inducing MELK expression, which coincides with the growth of TNBC[

9]. Therefore, OTSSP167 is employed to decrease the expression level of mutant p53 in TNBC cells, resulting in decreased MELK expression [

44]. This evidence indicates that various breast cancer subtypes are characterized by elevated MELK expression and establishes a foundation for its suggested application as a possible biomarker. Furthermore, it offers a promising alternative to traditional breast cancer treatments.

Glioma

Glioma is the predominant malignant primary brain tumor in adults. In the WHO classification of 2016, Glioma is classified histologically from grade I to grade IV[

45]. The expression of MELK is crucial for regulating the survival and maintenance of the stem cell phenotype in glioma stem cells (GSCs)[

19]. Glioma provoked by MELK activates various critical signaling pathways and proteins through multiple mechanisms. MELK interacts with and phosphorylates FOXM1, a transcription factor essential for cell growth, thus activating FOXM1 in GSCs[

46,

47]. In glioma cells, MELK-FOXM1 interaction promotes the expression of mitotic regulatory genes, thus enhancing mitosis and rapid proliferation of GSCs[

48]. Another signaling mechanism involves the development of a complex between MELK and the oncoprotein c-JUN in GSCs, which is absent in normal cells[

49]. Furthermore, MELK/EZH2/NFκB axis sustaining GSC stemness, MELK activates phosphorylation of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), which affects the differentiation and proliferation of GSCs via the methylation of NF-κB[

4]. Post-radiotherapy, GBM cells exhibit increased MELK expression levels. FOXM1 exhibits increased binding affinity and phosphorylation when MELK levels are elevated, which modulates EZH2 and contributes to radioresistance in GSCs[

50]. Thus, MELK is essential for the survival of GSCs by inhibiting radiation-induced apoptosis, making it a possible target for glioblastoma (GBM) treatment [

4,

27]. The GSCs' sensitivity to radiotherapy can be improved via MELK knockdown using siRNA or shRNA, leading to apoptosis of GSCs and a reduction in tumor formation [

19], or treatment with the MELK inhibitor (OTSSP167), thereby enhancing their therapeutic response [

4,

51]. These findings demonstrate that MELK is crucial for the growth of brain malignancies. MELK has generated considerable interest due to its role in preserving the stem-like characteristics of gliomas, providing further evidence that MELK serves as an emerging biomarker and potential therapy option for brain malignancies.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer has been classified as one of the most prevalent forms of cancer globally[

32]. Lung cancer can be grouped into two main types: small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)[

52]. NSCLCs are classified as lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), squamous cell lung carcinoma (LUSC), and large cell lung carcinoma (LULC)[

53]. Primary lung cancer tissues exhibit significantly elevated levels of MELK mRNA and protein expression compared to normal lung tissues [

21]. According to an analysis conducted by Oncomine and TCGA, MELK was overexpressed in the tissues of NSCLC, and a direct correlation was found between MELK expression and the poor malignant progression of NSCLC [

54,

55]. And MELK may be used as a diagnostic biomarker and treatment target for LUAD [

56]. MELK inhibition interrupts the cell cycle of lung cancer cells at the G2/M phase through the PLK1-CDC25C-CDK1 pathway, subsequently inducing apoptosis-mediated pyroptosis. It also prevented NSCLC from invading and spreading through the Focal adhesion kinase 1 (FAK1) signaling axis [

57,

58]. In addition, in NSCLC, the expression of MELK is upregulated, and its elevated levels are correlated with increased proliferation and rapid disease progression[

59]. SiRNA-mediated MELK knockdown suppressed and inhibited the growth of the NSCLC. In addition, inhibition of MELK by OTS167 led to a reduction in the proliferation of NSCLC, which in turn resulted in a decrease in FOXM1 activity and AKT expression, and consequently induced apoptosis, reduced tumor stemness, and improved survival in patients with NSCLC[

60]. These results reveal that MELK promotes lung cancer malignancy, providing an excellent basis for finding a new lung cancer therapy target.

Gastric Cancer

Gastric cancer (GC) serves as a highly prevalent and lethal malignancy globally, especially in older male populations. It is classified as the second most prevalent cause of cancer-related mortality in men, with approximately one million cases diagnosed annually[

61]. The overexpression of MELK mRNA and protein is markedly increased in primary GCs, enhancing cell proliferation and invasiveness through the inhibition of apoptosis, and elevated levels of MELK are associated with chemoresistant tissues and poorer clinical outcomes. Downregulating MELK expression or inhibiting its activity prevents gastric cancer cells from proliferating, invading, metastasizing, and inducing apoptosis, as well as arresting the cell cycle at the G2/M phase[

62,

63]. Furthermore, Increased expression of MELK resulted in macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype through the CSF-1/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, which increased Chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)[

63]. Meanwhile, the MELK Knockdown increases chemosensitivity to 5-FU and decreases proliferation, migration, and invasion of GC in both in vitro and in vivo contexts[

63,

64]. According to these studies, the overexpression of MELK promotes metastasis in gastric cancer, suggesting that MELK inhibition could serve as a novel therapeutic approach for GC.

Colorectal Cancer

In 2020, the incidence rate of colorectal cancer (CRC) was 10%; Consequently, it ranks among the most common types of cancer worldwide. It predicts that there will be 1.93 million new cases of CRC and 0.94 million deaths associated with CRC[

65]. The expression of MELK is elevated in CRC cells and tissues, indicating its significant role in regulating CRC (66,67). Additionally, MELK may be considered an oncogenic factor that accelerates CRC development by inducing AKT phosphorylation through the FAK/Src signaling pathway. Furthermore, the elevated expression of MELK enhances cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, while MELK knockdown reduces the phosphorylation level of AKT, thereby inactivating the FAK/Src pathways [

66]. Furthermore, the application of MELK treatment with shRNA resulted in a significant decrease in the proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC. Consequently, MELK may be examined as a novel therapeutic target, and reducing MELK expression could be utilized as a potential approach for treating colorectal cancer [

66]. These results reveal that MELK is significantly implicated in the initiation and progression of CRC. Furthermore, MELK can potentially be a viable clinical target for treating CRC.

Melanoma

Malignant neoplasms in melanocytes are referred to as melanoma. Over the past few decades, melanoma incidence has increased globally and differs by ethnicity and geographic region[

67]. 80% of skin cancer deaths are caused by melanoma[

68] Melanoma samples obtained from patients exhibited an overexpression of MELK compared to normal skin samples. Furthermore, patients with malignant melanoma exhibited elevated expression levels of MELK mRNA compared to those with primary melanoma. In melanoma cells, the MAPK pathway induces the expression of E2F1, which subsequently triggers the transcription of MELK by directly binding to the MELK promoter[

29]. MELK regulates the NF-κB pathway, which partially modulates MELK's ability to promote melanoma. Additionally, MELK significantly influences the regulation of melanoma proliferation through the MAPK pathway. Furthermore, MELK stimulates NF-kB transcription by phosphorylating the SQSTM1 protein, promoting melanoma cell proliferation. The MELK knockdown and treatment with small molecule inhibitors OTSSP167 and MELK-8a affect melanoma cells by inhibiting their proliferation and survival[

29]. In addition, the CRO15 compound inhibits MELK kinase activity through the downregulation of the NF-κB pathway. Which would ultimately reduce mitosis and melanoma cell development[

69]. The findings indicate that MELK is essential for the activation and progression of melanoma. Moreover, MELK shows potential as a viable therapeutic target for treating melanoma.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [

70]. In various studies on different liver cancers, MELK has been shown to be a crucial gene in controlling HCC. The elevated expression of the MELK protein is significantly associated with HCV and HBV virus infections, tumor quantity, tumor size, and vascular invasion[

5]. Furthermore, in normal healthy liver tissue, MELK is absent or expressed at minimal levels; however, its mRNA exhibits high expression in established cell lines of HCC, including HepG2, Huh7, and Li7, as well as in malignant patient tissues[

3]. Additionally, the expression level of MELK has been elevated, which is associated with high alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, advanced clinical stages, topographic stages, and histological grades in HCC. Additionally, patients with high MELK expression have been shown to have a significantly shorter median overall survival (48.95 ± 8.56 months) compared to those with low expression (80.68 ± 11.86 months) [

71]. In HCC, MELK overexpression is significantly correlated with the upregulation of FoxM1, a key regulator of the cell cycle, mitosis, and cell division [

70,

72]. Another pathway influenced by MELK is the PI3K/mTOR pathway. MELK augments the activity of this pathway, which is essential for cellular growth, proliferation, and survival, thereby actively facilitating HCC advancement [

71,

72]. Knockdown of MELK in liver cancer cells triggers apoptosis and prevents cell division, thereby decreasing HCC cell proliferation, invasion, stemness, and tumorigenicity [

70,

72]. Additionally, inhibition of MELK by OTS167 has been shown to significantly hinder the growth and progression of HCC and to provide an enhanced antitumor effect when used in conjunction with radiation [

73]. Thereby, MELK may act as a carcinogenic trigger for HCC and could represent a novel therapeutic strategy for its treatment.

Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer (BCa) is a prevalent form of urinary tumor that is distinguished by a significant degree of biological and clinical heterogeneity[

74,

75]. An early diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is related to a favorable prognosis, whereas a subsequent diagnosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is associated with a poor prognosis. MELK demonstrates markedly elevated expression levels in BCa cells obtained from patient tissues compared to normal tissues. MELK expression continues to increase in tandem with tumor progression. Remarkably, a correlation exists between increases in MELK expression in BCa cells and cell proliferation and migration. MELK promotes the growth of BCa by inhibiting the cell cycle and enhancing cell viability via the inhibition of the ATM/CHK2/p53 pathway. Furthermore, Inhibition of MELK using siRNA/shRNA or OTSSP167 therapy significantly decreased the proliferation of bladder cancer cells, and as a consequence, the cell cycle was stopped at the G1/S phase[

23]. The findings indicate that MELK is crucial for initiating and advancing BCa. Additionally, MELK represents a potential target for the treatment of BCa.

Kidney Cancer

Kidney cancer is a common urological malignancy, classified as the ninth most prevalent cancer in males and the fourteenth in females[

76]. Data from Oncomine and TCGA demonstrate that T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) and MELK show elevated expression in renal carcinoma [

5,

77]. Elevated MELK expression was identified in renal cancer cells and tissues, correlating with unfavorable prognosis and TNM stage. In contrast, the proliferation and metastasis of kidney carcinoma cells were reduced when MELK was suppressed[

78,

79]. Additionally, a significant correlation existed between MELK expression levels and FOXM1, a transcription factor and the principal regulator of mitosis at the level of cancer stem cells, and reduced overall survival. Blocking either of these kinases, MELK or TOPK, dramatically reduced FOXM1 activity and reduced the proliferation of kidney cancer cells[

3,

37,

77]. In addition, the use of the TOPK inhibitor (OTS514) and the MELK inhibitor (OTSSP167) resulted in a significant reduction in the proliferation of kidney cancer cells [

77,

80]. The data suggest that TOPK and MELK may serve as valuable targets in the treatment of kidney cancer. Additionally, the combination inhibition of OTS514 and OTS167 could lead to synergistic anti-tumor effects with minimal adverse side effects [

77]. These studies demonstrate that MELK plays a significant role in regulating renal cancer, suggesting that MELK may serve as a viable target for clinical therapy in kidney cancer.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer represents a prevalent malignancy impacting the young female reproductive system, but for women between the ages of 20 and 39, cervical cancer consistently ranks as the second most common malignancy to cause mortality[

32,

81]. In cervical cancer, the MELK protein showed oncogenic characteristics, and based on the TCGA data, MELK mRNA expression levels were significantly elevated in cervical cancer tissues relative to normal cervical tissues[

81,

82,

83]. Furthermore, a correlation is observed between MELK expression and the histological grading of the cervix, which includes normal cervical tissue, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia I, II, and III (CIN), and cervical cancer, 0%, 8.33%, 26.67%, 44.44%, and 56.92%, respectively[

81,

82]. Nevertheless, no correlation was observed between MELK expression and both the stages and survival rate of cervical cancer in individuals. This implies that the overexpression of MELK may occur early in the development of cervical cancer[

84]. Additionally, in cervical cancer, MELK overexpression promotes an immunosuppressive microenvironment by disrupting the Th1/Th2 balance, thereby favoring a Th2-dominated state. This establishes an immune microenvironment that is less proficient in generating an effective anti-tumor response. Reduced MELK expression alters the Th1/Th2 balance in cervical tumors in mice, promoting a Th1 bias and indicating an enhanced anti-tumor immune response[

84]. Furthermore, MELK knockdown inhibits the proliferation of cells, induces apoptosis, and provokes DNA damage, thus reducing cervical cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenicity

in vivo [

5,

81,

82]. Besides that, MELK-8A and OTSSP167, which are MELK inhibitors, effectively induce cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase and promote apoptosis, suppressing cervical cancer proliferation, growth, and tumorigenicity[

81,

82]. As a result, MELK has the potential to serve as a novel biomarker for predicting the unfavorable outlook of cervical cancer and indicating that MELK could be a potential target for therapy of cervical cancer.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the sixth most prevalent malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in postmenopausal women[

85]. Ovarian cancer survival rates are still mainly affected by the disease's clinical stage. The prognosis for early-stage ovarian cancer is generally favorable; however, extremely low survival rates are associated with high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC)[

7]. MELK is significantly more expressed in serous ovarian cancer (SOC) than in normal ovarian tissue. This increased expression of MELK correlates with a more aggressive histological grading of SOC and a more rapid decline in overall survival[

86,

87]. MELK levels in the normal ovarian surface epithelium are typically low. While mucinous and endometrioid borderline tumors exhibit a slightly elevated incidence. In samples of primary and metastatic ovarian cancer of various histotypes, including serous ovarian cancer, they are present at elevated levels[

87]. This pattern suggests that MELK expression increases progressively as the disease advances and the cancer stage becomes more severe. Elevated MELK mRNA levels were detected exclusively in patients with advanced-stage disease, positive ascites cytology, and increased residual tumor size[

86]. Knockdown of MELK via shRNA-mediated reduction of MELK protein induces apoptosis and inhibits neoplastic progression in epithelial ovarian cancer cells [

87]. Furthermore, the expression of MELK mRNA was considerably more significant in tumors collected before chemotherapy than in those collected after chemotherapy [

86]. The use of MELK inhibitor OTSSP167 for treatment significantly suppressed ovarian cancer growth, unrelated to the histological subtype. Additionally, it enhanced the sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to carboplatin by regulating the cell cycle, tumor cell stemness, and apoptosis [

86,

87]. According to the findings of the studies, the MELK protein serves as a potential target for the treatment and a prognostic indicator in ovarian cancer prevention.

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer (EC) ranks as the sixth most prevalent cancer among women, and in 2020, it is projected that there will be 417,000 new cases globally[

88,

89]. The global incidence of cases is increasing, attributed to demographic shifts such as an aging population and a rise in obesity-related illnesses[

90]. It is noted that increased MELK expression correlated with higher grade (grade 3), advanced stages (III and IV), and serous EC relative to non-tumor tissues[

83,

91,

92]. Investigations of large public databases such as The TCGA and GEO, along with immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses of clinical samples, have consistently validated this increase[

93]. Furthermore, elevated MELK expression in EC is correlated with poor overall survival, disease-free survival, and unfavorable survival outcomes. In EC, high MELK expression is caused by the transcription factor E2F1, by directly binds to MELK[

93]. A primary mechanism by which MELK promotes EC development is the stimulation of the mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling pathways by direct binding with MLST8, a component of the mTOR complexes[

93]. MELK expression in uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) was significantly elevated compared to uterine leiomyoma (ULM) and myometrium. Moreover, increased levels of MELK expression were noted in severe cases, and MELK was demonstrated as an unfavorable prognostic indicator for aggressive ULMS[

94]. By using HECA1 cells in a xenograft mouse model, it was observed that high MELK expression enhances both proliferation and metastasis, indicating that MELK has tumorigenic potential in HECA1 cells. Furthermore, similar to other types of cancer, MELK Knockdown decreases the proliferation of HEC1A cells and brings about an arrest in the cell cycle at the G2/M phase[

93]. Treatment with doxorubicin or OTSSP167 alone has the potential to significantly inhibit the growth of tumors, whereas combination treatment significantly decreases tumor size and tumor weight[

94]. The new evidence indicates that MELK may function as a biomarker and therapeutic target for endometrial cancer.

Prostate Cancer

In 2020, approximately 1,414,000 new cases of prostate cancer (PC) were reported, alongside 375,304 deaths. This positions PC as the second most prevalent cancer diagnosis and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men worldwide [

95]. Increased expression of MELK was observed in high-grade PC tissue, which was related to cell proliferation and continued cell cycle progression[

96,

97]. Additionally, MELK expression is associated with tumor progression and enhances the survival of PC cells [

97]. On the other hand, MELK serves as a significant upstream regulator of the E2F8 transcription factor, and E2F8 promotes cancerous characteristics; its expression increases as the progression of PC advances. Patients with PC who had high levels of E2F8 expression had a poor prognosis. Additionally, the inhibition of either E2F8 or MELK significantly inhibits PC cells' proliferation and colony formation. This suggests the presence of a direct regulatory axis that facilitates tumor growth [

98]. The expression of the MELK gene has been shown to have a strong correlation with genes that are involved in the cell cycle, including DNA topoisomerase II alpha (TOP2A), Aurora Kinase B (AURKB), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 C (UBE2C), and Cyclin B2 (CCNB2), indicating the involving of MELK in the progress of the cell cycle in PC cells[

96]. Additionally, siRNA knockdown of MELK expression inhibits both colony formation and cell proliferation [

97,

98]. Treatment with OTSSP167 inhibits MELK, induces apoptosis, and efficiently inhibits the growth of xenograft tumors and PC cells by lowering stathmin phosphorylation and disrupting the formation of the mitotic spindle [

97,

99]. Research shows that MELK serves as a promising biomarker and therapeutic target for prostate cancer.

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma (OS) remains the most prevalent primary bone cancer, accounting for 2% of all childhood cancers[

32]. MELK is significantly more expressed in OS than in normal tissue. Additionally, OS proliferation and worse prognosis were associated with increased MELK expression. MELK enhances OS proliferation and metastasis through the regulation of PCNA (Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen) and MMP9 (Matrix Metalloproteinase-9) via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway[

100]. Knocking down MELK expression in OS cell lines via siRNA or inhibition with the MELK inhibitor OTSSP167 results in reduced cell proliferation, metastatic development, and a decrease in tumor volume. Likewise, Cell cycle progression in osteosarcoma is also suppressed after MELK is knocked down[

100,

101]. Furthermore, MELK knockdown by RNAi or inhibition by OTSSP167 resulted in a significant decrease in the expression levels of p-PI3K, p-AKT, p-mTOR, PCNA, and MMP-9[

100]. Therefore, MELK can act as an oncogenic stimulant for osteosarcoma and might be considered as an innovative therapeutic strategy for its treatment.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common form of leukemia in adults, which is biologically and clinically diverse. Moreover, the main characteristics of CLL include resistance to apoptosis, uncontrolled cellular proliferation, incurability, and prolonged survival post-diagnosis, which can vary from months to decades [

102,

103,

104]. Elevated MELK expression at both the mRNA and protein levels was detected in primary CLL cells and CLL cell lines (EHEB and MEC1) in comparison to normal B-cells[

105,

106]. Furthermore, MELK enhanced CLL cell survival by reducing apoptosis and facilitating the transition from the G2/M phase[

106]. Likewise, a substantial correlation existed between elevated MELK expression and increased white blood cell count, increased lactate dehydrogenase concentration, and increased β2-microglobulin levels[

105]. In addition, MELK may have contributed to the development of CLL tumors by modulating multiple oncogenic signaling pathways. Knockdown of MELK in CLL cells resulted in an impairment in the G2/M phase[

106]. Besides knockdown by siRNA, the MELK Knockout mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 promoted apoptosis and suppressed proliferation in CLL cells. On the other hand, the FoxM1-cyclin B1/CDK1 signaling pathway is down-regulated by MELK inhibition. Furthermore, treatment of CLL cells with OTSSP167 resulted in the suppression of cell survival, progression through the cell cycle, migration, and chemoresistance, thereby demonstrating the anti-tumor efficacy of OTSSP167 [

106]. As a result, high levels of MELK expression are responsible for stimulating the proliferation of CLL cells; consequently, targeting MELK could be an innovative therapeutic strategy for treating CLL.

Acute myeloid leukemia

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is an aggressive form of hematologic malignancy defined by the pathological proliferation of immature myeloid blast cells in the bone marrow and peripheral blood[

107]. The expression of MELK was higher in CD34+ blast cells of AML than CD34- blast cells, with significantly greater levels observed in undifferentiated stem blast cells relative to more differentiated cells[

99,

108,

109]. MELK expression varies across AML subsets; however, MELK expression was comparatively elevated in AML cases with multifaceted karyotypes, t(6;9), and del(5q)/-5, which are related to cancers that exhibit chemotherapy resistance and poorer clinical outcomes[

109]. In addition, increased MELK expression activates FOXM1. In patients with AML, FOXM1 and its target, such as Cyclin B1, have been shown to be involved in the process of promoting proliferation through the regulation of cell cycle progression. The overexpression of FOXM1 in cancer cells and AML-derived leukemic blasts accelerates their proliferation[

108,

109]. Inhibition of MELK expression through siRNA or the inhibition of MELK kinase activity via OTS167 significantly inhibits the proliferation of AML cells. Additionally, inhibiting MELK led to a downregulation of FOXM1 activity[

99,

108,

109]. In addition to inducing myeloid differentiation and apoptosis, OTS167 inhibited the growth of AML cells. Moreover, MELK may serve as a significant, unique target for treatment in AML, necessitating further examination of the clinical development of OTS167 in this context[

109]. The conclusions of these studies indicate that elevated MELK expression enhances the proliferation of AML cells. Targeting MELK may offer a novel therapeutic strategy for AML.

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma (MM) ranks as the second most prevalent hematologic malignancy. It is classified as a clonal disorder involving the proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow microenvironment, characterized by the aberrant synthesis of monoclonal immunoglobulin and organ failure [

110,

111]

. MELK is significantly overexpressed in MM, indicating an inverse relationship between MELK expression and survival rates. On the other hand, MELK overexpression in plasma cell leukemia (PCL) relative to MM indicates a stronger correlation between MELK expression and aggressive disease. Furthermore, an increase in MELK expression after treatment compared to baseline in MM patients suggests a correlation between MELK overexpression and drug resistance[

110]. In addition, MELK overexpression correlates with increased expression of cell cycle regulation genes, including FOXM1, AURKA, KIF11, BUB1B, CDK1, CCNB1, and CCNB2[

110,

112]. Furthermore, targeting MELK and FOXM1 with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) significantly inhibited the growth of MM cells[

110,

112]. Inhibition of MELK through OTSSP167 resulted in reduced myeloma cell proliferation and survival. In myeloma cells, inhibiting MELK results in the downregulation of PLK1, CCNB1, and AURKA, leading to G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [

110,

112,

113]. Furthermore, OTSSP167 exhibits significant synergistic activity when combined with lenalidomide/pomalidomide and dexamethasone. This confirms the efficacy and benefits of OTSSP167 when used in conjunction with established anti-myeloma therapies[

110]. These findings indicate a strong correlation between MELK and the proliferation of high-risk myeloma, suggesting that MELK may serve as a viable target for clinical therapy in MM.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) belong to a heterogeneous type of lymphoid malignancies. The most aggressive subtypes in NHL are Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), which includes 7% of NHL, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is representative of 30–40% of all NHL[

114,

115,

116]. MCL is distinguished by a genetic anomaly caused by chromosome translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32)[

117]. This translocation causes continuous overexpression of proteins involved in the cell cycle, such as cyclin D1, which is crucial in pathogenesis by facilitating the transition from G1 to S phase, thus promoting unregulated cellular proliferation[

118]. Compared to normal B cell samples, MELK expression was considerably greater in all subtypes of DLBCL and MCL[

6,

119]. Furthermore, Patients with DLBCL exhibiting elevated MELK expression demonstrated a significantly poorer prognosis and survival outcomes[

6]. Additionally, MELK activates the PI3K/mTOR pathway. MELK augments the activity of this pathway, which is essential for cellular growth, proliferation, survival, and resistance to immunotherapy and chemotherapy in cancer cells[

71,

72]. The activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway plays a crucial role in the survival, development, and treatment resistance of DLBCL and MCL cells[

118,

120]. Another pathway persistently activated and facilitates cell proliferation and survival in DLBCL and MCL is the NF-κB pathway, which MELK activates through Sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1). [

121]. In the case of lymphoma, reducing cell viability can be achieved by inhibiting MELK expression via treatment with siRNA or inhibiting MELK kinase activity by OTS167 treatment, which induces apoptosis via caspase-3 and significantly enhances overall survival rates. Furthermore, OTS167 demonstrates a strong synergistic effect with venetoclax treatment, augmenting the effectiveness of MELK inhibitors in all evaluated cell line[

6]. Based on these findings, MELK may serve as a promising novel target for aggressive B-cell leukemias.

MELK inhibitors

Chemotherapy has served as the most fundamental and prevalent treatment approach in the fight against cancer in recent decades[

5,

7,[5,7,]. Recent studies have focused on the MELK gene inhibitors using small molecules, such as OTS167 [

13], Cyclosporine A [

122], MELK 8a, MELK 8b [

123], HCTMPPK [

122], MELK-T1 [

17], and Phillygenin (PHI) [

123].

OTS167 (OTSSP167)

OTSSP167 also known as OTS167 is composed of a "((1,5-naphthyridine core that contains methylketone at the 3-position, trans-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)) cyclohexylamino at the 4-position, and 3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl at the 6-position))"[

108]. OTSSP167, with an IC50 of 0.41 nM, is a novel inhibitor that specifically targets MELK, efficiently suppressing the development and progression of various types of cancer. OTSSP167 has shown promising results in phase I and II clinical trials in AML and breast cancer, making it the only MELK inhibitor presently available[

31,

106]. It is achievable for OTSSP167 to inhibit the phosphorylation of MELK substrates, thus ultimately resulting in the suppression of tumor cell proliferation[

69]. Moreover, OTSSP167 suppresses cellular growth and invasion through the obstruction of the AKT signaling pathway activation[

27]. Additionally, OTSSP167 has the effect of reducing the expression of FoxM1, causing cessation of cell cycle progression[

124]. Alternatively, new evidence suggests that OTSSP167 can inhibit cell proliferation via a non-target-specific mechanism since the tumor was still responsive to the compound even after the Melk knockout[

11]. The ambiguity surrounding the primary therapeutic target of a potent compound poses a significant challenge in drug development, despite its advancement in clinical trials.

Accumulated research conducted over the last decade has demonstrated the impact of OTSSP167 on inhibiting the proliferation of several types of tumor cell lines by targeting MELK in a dose-dependent manner, including NSCLC, SCLC[

60,

99], TNBC[

9], colorectal cancer[

125], kidney cancer[

77], cervical cancer [

81], ovarian cancer[

86,

87], prostate cancer[

99], osteosarcoma[

100], CLL[

106], AML[

109], and Multiple myeloma[

126]. Additionally, OTS167 demonstrated a substantial

in vivo inhibitory effect on tumor growth across various human cancer xenograft mouse models[

60], the effect demonstrated in prostate cancer[

97], endometrial carcinoma[

92], neuroblastoma[

127], TNBC, lung cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer[

99], adrenocortical cancer[

128], and gastric cancer[

62].

Furthermore, OTSSP167 has been combined with other compounds to enhance the inhibitory effect on MELK. The combination of OTSSP167 with bortezomib results in more potent inhibition of the proliferation of breast cancer cells[

129]. Likewise, the OTSSP167 and cyclin-dependent inhibitor (RGB-286638) combination was used in adrenocortical cancer treatment. This synergism yielded a markedly greater antiproliferative impact, increased caspase-dependent apoptosis, and downregulated MELK expression[

128]. The research suggests that OTSSP167 is a novel and effective compound, warranting further testing for cancer treatment in vivo and in clinical trials.

Cyclosporine A

Due to its high efficacy, the immunosuppressant medicine cyclosporine A (CsA) has found widespread application in organ transplantation[

130]. In addition, CsA demonstrates antineoplastic effects against various cancer types, including prostate cancer[

98,

131]. In prostate cancer, a critical transcription factor E2F8 promotes cancerous characteristics and influences poor prognosis. Furthermore, the MELK-E2F8 signaling axis is integral to the biology of prostate cancer. Additionally, CsA significantly decreased the expression of E2F8. Therefore, in cases of prostate cancer, E2F8 is a potential target for therapeutic intervention, and MELK is a crucial component in regulating the expression of E2F8. Thus, inhibiting either E2F8 or MELK improves the sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to androgen receptor-blocking treatment [

98].

Tetramethyl Pyrazine Chalcone Hybrid-HCTMPPK

Tetramethyl pyrazine (TMP), often known as ligustrazine, is a potent alkaloid monomer with very effective bioactive components. Extensive studies have conclusively shown that TMP and its derivatives have significantly inhibited the growth of various cancer cells, including those in liver cancer[

132,

133], lung cancer[

134], colorectal cancer[

135], and breast cancer[

136]. HCTMPPK (a derivative of TMP) was subjected to molecular docking with the MELK, AURKA, and JUN proteins. The interaction between HCTMPPK and MELK genes significantly reduced MELK expression and hindered the progression of NSCLC. Although HCTMPPK has been proven to inhibit MELK expression, the exact mechanisms involved remain unclear[

122]. These studies indicate that HCTMPPK may act as an effective anti-tumor chemotherapeutic agent.

MELK 8a, 8b

The compound MELK 8a, 8b is alternatively referred to as "((1-methyl-4-[4-[4-[3-(piperidin-4 ylmethoxy) pyridin-4-yl] pyrazol-1-yl] phenyl] piperazine))", also known as Novartis MELK inhibitor 8a (NVS-MELK8a) and (NVS-MELK8b). The compounds inhibit cell proliferation and cell cycle in MELK-dependent MDA-MB-468 cells[

137]. Furthermore, MELK 8a demonstrates high selectivity as a MELK inhibitor, representing the first dependable alternative to OTSSP167 for functional studies of MELK. Additionally, MELK 8a reduces the viability of and diminishes the growth of TNBC cell lines[

138]. Besides, it has high selectivity as a MELK inhibitor; this inhibition results in a postponement of the mitotic entrance, which is consistent with a transient G2 arrest state[

138]. Furthermore, MELK 8a decreased SQSTM1 phosphorylation and inhibited the NF-κB pathway, consequently suppressing the proliferation of melanoma cells[

5,

29]. These studies indicate that MELK 8a and 8b inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells with high MELK expression; therefore, additional research is necessary to clarify the mechanisms of this inhibition.

MELK-T1

The compound MELK-T1 is alternatively referred to as "2-methoxy-4-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-N-(2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepin-7-yl) benzamide))". MELK-T1 demonstrates significant and selective inhibition of the MELK kinase domain, rapidly decreasing endogenous MELK levels by causing it to break down through a process that depends on the proteasome, and inhibiting the growth of MCF-7, a breast adenocarcinoma cell line. On the other hand, MELK-T1 is classified as a type I ATP-mimetic inhibitor, binds to MELK, and activates the degradation of the MELK protein by stabilizing the ATP-bound conformation[

17]. Furthermore, MELK-T1 affects various mechanisms, significantly inducing p53 phosphorylation, prolonging the upregulation of p21, and downregulating FOXM1 and its target genes. This is consistent with the previously reported effects of OTSSP167 on AML cell lines [

17,

99]. The inhibition and depletion of MELK protein through MELK-T1 treatment could allow cancer cells to recognize and respond to DNA damage once again, thereby enhancing tumor sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [

17]. Ultimately, the dual mechanism of inhibiting enzyme function while reducing its cellular abundance may yield a more effective and lasting therapeutic outcome compared to inhibitors that exclusively target catalytic activity.

The Controversy: The Crucial Role of MELK in Cancer Growth (RNAi vs. CRISPR/Cas9 Methods)

As previously noted, the use of RNAi and small molecule inhibitors demonstrated MELK's crucial role as a vital therapeutic target due to the issue of overexpression in various cancers and its association with severe disease phenotypes, chemotherapy resistance, cancer stem cell renewal, and overall cancer proliferation, resulting in the progression of MELK inhibitors to clinical trials. Nonetheless, the definitive role of MELK in cancer cell proliferation remains a topic of significant debate within the scientific community, characterized by inconsistent results from various experimental methodologies. The variance can be attributed to the researchers' utilization of a CRISPR/Cas9 methodology, which completely knocked out MELK.

However, few research studies have emerged that contradict the findings of prior investigations. Wang Y. et al. (2014) concluded that the proliferation of BLBC cells requires MELK kinase activity, whereas luminal breast cancer cell proliferation does not. In addition, post-MELK knockdown via RNAi has shown that Exogenous WT MELK expression can rescue the growth effects in both cells and tumors. Moreover, the author posed a question and left it open for discussion: What is the reason for MELK's selective requirement in cell division within BBC cells, whereas it is not required in other breast cancer types or normal cells?[

57] Later, Lin A et al. (2017) used a different technology, CRISPR/Cas9, to generate frameshift mutations in the MELK gene, aiming to investigate the impact of MELK knockout on cancerous cell lines. Pooled MELK-null, seven triple-negative breast cancer cell lines, were created using gRNAs. These lines were compared with the negative control Rosa26 deletion control cells, and the proliferative activity of MELK cell lines, whether they were wild-type or mutant, remained unchanged. Based on these findings, MELK expression is not essential for TNBC, and it does promote cancer cell proliferation[

11]. These findings prompt us to reconsider whether MELK inhibitor OTS167 can prevent cancer cell proliferation. If the MELK inhibitors stop tumor cell proliferation and tumor cells are not MELK-dependent, then OTS167 is successful in inhibiting tumor cell proliferation or its cellular target genes, other than MELK. This may lead us to the conclusion that OTS167's anti-proliferative actions are not due to its suppression of MELK[

11].

In a different study in 2017, Huang H et al. used integrated chemical and genetic modifications. Researchers have employed a novel method for protein degradation that utilizes chemical agents, CRISPR, and RNAi to investigate MELK as a potential therapeutic target for BBC therapy. Also, slight molecule inhibition, gene deletion, or MELK exhaustion under standard culture conditions did not significantly affect cellular proliferation. Both gene editing and pharmaceutical suppression of MELK in breast cancer cell lines failed to inhibit cell proliferation in vitro[

10]. The study's discrepancy with previous research prompted researchers to investigate the selection effects of OTSSP167 and the potential off-target consequences of short hairpins targeting MELK. Regarding this issue, researchers compared the sensitivity to selective MELK inhibitors and OTSSP167 in wild-type (WT) and MELK knockout (MELK−/−) cells. Their conclusion indicated that after treatment with OTSSP167, there are no differences in cell viability, demonstrating that the effect of OTSSP167 on the viability of MDA-MB-468 cells is not attributable to MELK inhibition and that its target is different from MELK. The findings indicate that under typical culture conditions, suppressing or depleting MELK alone has no adverse effect on BBC cell line proliferation[

10].

In a 2018 study, Giuliano et al. observed that the overexpression of MELK alone was insufficient to induce transformation in immortalized cell lines. The findings indicate that MELK is not essential for cancer cell proliferation, both in vivo and in vitro, and indicate that the immediate absence of MELK does not result in any notable impairment of cell viability, proliferation, or drug resistance. Furthermore, the results show that MELK knockout cells have not developed mutations that make cells more tolerant to the lack of MELK[

12,

139].

Research utilizing CRISPR technology indicates that MELK does not play a significant role in the proliferation of cancer cells and is not a viable therapeutic target. These findings, which show no proliferation after MELK knockout with CRISPR, do not conclusively support these claims. Even though these studies have conclusively shown that MELK is not essential for the proliferation of cancer cells, no actions have been taken by them to argue against the findings that MELK knockdown by RNAi can be rescued by exogenous WT MELK expression, indicating that MELK is essential for proliferation and that the therapeutic potential of decreasing MELK should not be disregarded at this time, especially when used in combination with other chemotherapeutic medications[

40].

Conclusion

Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase (MELK) is recognized as a crucial oncogenic factor and overexpressed in many types of human cancers. Higher MELK levels are often correlated with unfavorable prognosis, aggressive tumor manifestations, resistance to treatment, and stem-like tumor morphologies. These correlations indicate that MELK serves as a clinically significant biomarker for tumor proliferation and malignancy.

Functional studies employing RNA interference and pharmacological inhibitors, such as OTSSP167, indicate that MELK plays a crucial oncogenic role, with MELK inhibition leading to decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, and heightened sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, more recent CRISPR/Cas9 knockout studies have questioned MELK’s essentiality for cancer cell survival, raising the possibility that MELK may be dispensable in certain contexts, or that functional redundancy allows cancer cells to adapt to its loss. Moreover, the anti-tumor activity of OTSSP167 appears to involve off-target mechanisms, further complicating the interpretation of MELK’s role as a direct therapeutic driver.

Taken together MELK may not be regarded as a universal therapeutic target. Its primary and most robust function is to serve as a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker indicating tumor aggressiveness. Despite this, MELK inhibition may retain therapeutic potential in certain cancer types, especially when combined with other therapies or in cancers where MELK-driven pathways are essential for tumor maintenance. Further research is necessary to resolve the controversy surrounding MELK dependency and to refine therapeutic strategies that exploit its biological functions.

Abbreviations:

MELK: Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase, KA1: Kinase-associated segment, FOXM1: Forkhead box M1, ZPR9: Zinc finger protein analog, NIPP1: Nuclear inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatase-1, TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β, ASK1: Signal-regulated kinase 1, GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus, TCGA: Cancer Genome Atlas, BLBC: Basal-like breast cancer, TNBC: Triple-negative breast cancer, GSCs: Glioma stem cells, EZH2: Enhancer of zeste homolog 2, GBM: Glioblastoma, SCLC: Small cell lung cancer, NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer, LUAD: Lung adenocarcinoma, LUSC: Squamous cell lung carcinoma, LULC: Large cell lung carcinoma, FAK1: Focal adhesion kinase 1, GC: Gastric cancer, CRC: Colorectal cancer, HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma, AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein, BCa: bladder cancer, NMIBC: Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, MIBC: Muscle-invasive bladder cancer, TOPK: T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase, HGSOC: High-grade serous ovarian cancer, SOC: Serous ovarian cancer, EC: Endometrial cancer, IHC: Immunohistochemistry, ULMS: Uterine leiomyosarcoma, ULM: Uterine leiomyoma, PC: Prostate cancer, TOP2A: Topoisomerase II alpha, AURKB: Aurora kinase B, UBE2C: Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 C, CCNB2: Cyclin B2, OS: Osteosarcoma, PCNA: Proliferating cell nuclear antigen, MMP9: Matrix metalloproteinase-9, CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, AML: Acute myeloid leukemia, MM: Multiple myeloma, PCL: Plasma cell leukemia, shRNA: Short hairpin RNA, NHLs: Non-Hodgkin lymphomas, MCL: Mantle cell lymphoma, DLBCL: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, SQSTM1: Sequestosome 1, CsA: Cyclosporine A, TMP: Tetramethyl pyrazine,

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M.Z. and S.A.; Writing—original draft: A.M.Z.; Writing—review and editing: A.M.Z. and S.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

Data sharing does not apply to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participation not applicable (review study).

Abbreviations

| AFP |

Alpha-fetoprotein |

| AML |

Acute myeloid leukemia |

| ASK1 |

Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 |

| AURKB |

Aurora kinase B |

| BCa |

Bladder cancer |

| BLBC |

Basal-like breast cancer |

| CCNB2 |

Cyclin B2 |

| CLL |

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CRC |

Colorectal cancer |

| CsA |

Cyclosporine A |

| DLBCL |

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma |

| EC |

Endometrial cancer |

| EZH2 |

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 |

| FAK1 |

Focal adhesion kinase 1 |

| FOXM1 |

Forkhead box M1 |

| GBM |

Glioblastoma |

| GC |

Gastric cancer |

| GEO |

Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GSCs |

Glioma stem cells |

| HCC |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HGSOC |

High-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| KA1 |

Kinase-associated segment |

| LUAD |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

| LULC |

Large cell lung carcinoma |

| LUSC |

Squamous cell lung carcinoma |

| MCL |

Mantle cell lymphoma |

| MELK |

Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase |

| MIBC |

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| MM |

Multiple myeloma |

| MMP9 |

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| NHLs |

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas |

| NMIBC |

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| NIPP1 |

Nuclear inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatase-1 |

| NSCLC |

Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OS |

Osteosarcoma |

| PC |

Prostate cancer |

| PCNA |

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| PCL |

Plasma cell leukemia |

| SCLC |

Small cell lung cancer |

| shRNA |

Short hairpin RNA |

| SOC |

Serous ovarian cancer |

| SQSTM1 |

Sequestosome 1 |

| TCGA |

Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TGF-β |

Transforming growth factor-β |

| TMP |

Tetramethyl pyrazine |

| TNBC |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TOP2A |

Topoisomerase II alpha |

| TOPK |

T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase |

| UBE2C |

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 C |

| ULM |

Uterine leiomyoma |

| ULMS |

Uterine leiomyosarcoma |

| ZPR9 |

Zinc finger protein analog |

References

- Beullens, M.; Vancauwenbergh, S.; Morrice, N.; Derua, R.; Ceulemans, H.; Waelkens, E.; Bollen, M. Substrate Specificity and Activity Regulation of Protein Kinase MELK. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 40003–40011. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Seong, H.-A.; Ha, H. Murine Protein Serine/Threonine Kinase 38 Activates Apoptosis Signal-regulating Kinase 1 via Thr838 Phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 34541–34553. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.; Mohyeldin, A.; Thiel, J.; Kornblum, H.I.; Beullens, M.; Nakano, I. MELK—a conserved kinase: functions, signaling, cancer, and controversy. Clinical & Translational Med 2015, 4, e11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Qi, X.; Gordon, R.E.; O’Brien, J.A.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Song, Y.; et al. EZH2 Phosphorylation Promotes Self-Renewal of Glioma Stem-Like Cells Through NF-κB Methylation. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 641. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.-F.; Yan, R.-C.; Wang, S.-W.; Zeng, Z.-C.; Du, S.-S. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase in tumor cells and tumor microenvironment: An emerging player and promising therapeutic opportunity. Cancer Letters 2023, 560, 216126. [CrossRef]

- Maes, A.; Maes, K.; Vlummens, P.; De Raeve, H.; Devin, J.; Szablewski, V.; De Veirman, K.; Menu, E.; Moreaux, J.; Vanderkerken, K.; et al. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase is a novel target for diffuse large B cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2019, 9, 87. [CrossRef]

- Thangaraj, K.; Ponnusamy, L.; Natarajan, S.R.; Manoharan, R. MELK/MPK38 in cancer: from mechanistic aspects to therapeutic strategies. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25, 2161–2173. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ku, J.-L. Resistance of colorectal cancer cells to radiation and 5-FU is associated with MELK expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2011, 412, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lee, Y.-M.; Baitsch, L.; Huang, A.; Xiang, Y.; Tong, H.; Lako, A.; Von, T.; Choi, C.; Lim, E.; et al. MELK is an oncogenic kinase essential for mitotic progression in basal-like breast cancer cells. eLife 2014, 3, e01763. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-T.; Seo, H.-S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Li, Q.; Buckley, D.L.; Nabet, B.; Roberts, J.M.; Paulk, J.; et al. MELK is not necessary for the proliferation of basal-like breast cancer cells. eLife 2017, 6, e26693. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Giuliano, C.J.; Sayles, N.M.; Sheltzer, J.M. CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis invalidates a putative cancer dependency targeted in on-going clinical trials. eLife 2017, 6, e24179. [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, C.J.; Lin, A.; Smith, J.C.; Palladino, A.C.; Sheltzer, J.M. MELK expression correlates with tumor mitotic activity but is not required for cancer growth. eLife 2018, 7, e32838. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.-S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, Z.-X.; Wu, J.-W. Structural Basis for the Regulation of Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70031. [CrossRef]

- Seong, H.-A.; Manoharan, R.; Ha, H. Zinc finger protein ZPR9 functions as an activator of AMPK-related serine/threonine kinase MPK38/MELK involved in ASK1/TGF-β/p53 signaling pathways. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42502. [CrossRef]

- Emptage, R.P.; Schoenberger, M.J.; Ferguson, K.M.; Marmorstein, R. Intramolecular autoinhibition of checkpoint kinase 1 is mediated by conserved basic motifs of the C-terminal kinase–associated 1 domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292, 19024–19033. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Liu, S.-T. Spatiotemporal regulation of MELK during mitosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1406940. [CrossRef]

- Beke, L.; Kig, C.; Linders, J.T.M.; Boens, S.; Boeckx, A.; Van Heerde, E.; Parade, M.; De Bondt, A.; Van Den Wyngaert, I.; Bashir, T.; et al. MELK-T1, a small-molecule inhibitor of protein kinase MELK, decreases DNA-damage tolerance in proliferating cancer cells. Bioscience Reports 2015, 35, e00267. [CrossRef]

- Pitner, M.K.; Taliaferro, J.M.; Dalby, K.N.; Bartholomeusz, C. MELK: a potential novel therapeutic target for TNBC and other aggressive malignancies. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 2017, 21, 849–859. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.; Hong, C.S.; Smith, L.G.F.; Kornblum, H.I.; Nakano, I. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase: Key Kinase for Stem Cell Phenotype in Glioma and Other Cancers. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2014, 13, 1393–1398. [CrossRef]

- Baddourah, R.; Baddourah, D.; Alsweedan, D.; Al Sheyyab, M.; Nimri, O.F.; Alsweedan, S. Incidence, distribution, and patient characteristics of childhood cancer in Jordan: an updated population-based study. Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy 2024, 17, 233–238. [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.; Jubb, A.M.; Hogue, D.; Dowd, P.; Kljavin, N.; Yi, S.; Bai, W.; Frantz, G.; Zhang, Z.; Koeppen, H.; et al. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase/Murine Protein Serine-Threonine Kinase 38 Is a Promising Therapeutic Target for Multiple Cancers. Cancer Research 2005, 65, 9751–9761. [CrossRef]

- Chartrain, I.; Le Page, Y.; Hatte, G.; Körner, R.; Kubiak, J.Z.; Tassan, J.-P. Cell-cycle dependent localization of MELK and its new partner RACK1 in epithelial versus mesenchyme-like cells in Xenopus embryo. Biology Open 2013, 2, 1037–1048. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Q.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, M.; Ju, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X. Inhibition of MELK produces potential anti-tumour effects in bladder cancer by inducing G1/S cell cycle arrest via the ATM/CHK2/p53 pathway. J Cellular Molecular Medi 2020, 24, 1804–1821. [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; Beach, D.; Shapiro, G.I. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: From Discovery to Therapy. Cancer Discovery 2016, 6, 353–367. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Zhang, D. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase (MELK): A Novel Regulator in Cell Cycle Control, Embryonic Development, and Cancer. IJMS 2013, 14, 21551–21560. [CrossRef]

- Zona, S.; Bella, L.; Burton, M.J.; Nestal De Moraes, G.; Lam, E.W.-F. FOXM1: An emerging master regulator of DNA damage response and genotoxic agent resistance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2014, 1839, 1316–1322. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Wu, R.; Liang, J.; Yu, R.; Liu, X. MELK Inhibition Effectively Suppresses Growth of Glioblastoma and Cancer Stem-Like Cells by Blocking AKT and FOXM1 Pathways. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 608082. [CrossRef]

- Cigliano, A.; Pilo, M.G.; Mela, M.; Ribback, S.; Dombrowski, F.; Pes, G.M.; Cossu, A.; Evert, M.; Calvisi, D.F.; Utpatel, K. Inhibition of MELK Protooncogene as an Innovative Treatment for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Medicina 2019, 56, 1. [CrossRef]

- Janostiak, R.; Rauniyar, N.; Lam, T.T.; Ou, J.; Zhu, L.J.; Green, M.R.; Wajapeyee, N. MELK Promotes Melanoma Growth by Stimulating the NF-κB Pathway. Cell Reports 2017, 21, 2829–2841. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chauhan, G.B.; Edupuganti, R.; Kogawa, T.; Park, J.; Tacam, M.; Tan, A.W.; Mughees, M.; Vidhu, F.; Liu, D.D.; et al. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase is Associated with Metastasis in Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Research Communications 2023, 3, 1078–1092. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Dong, G.; Li, X. Structural classification of MELK inhibitors and prospects for the treatment of tumor resistance: A review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 156, 113965. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2023, 73, 17–48. [CrossRef]

- Cho, N. Molecular subtypes and imaging phenotypes of breast cancer. Ultrasonography 2016, 35, 281–288. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Sharma, A.; Dube, P.; Shaikh, S.; Vaghasia, H.; Rawal, R.M. Identification of crucial hub genes and potential molecular mechanisms in breast cancer by integrated bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 149, 106036. [CrossRef]

- Malvia, S.; Bagadi, S.A.R.; Pradhan, D.; Chintamani, C.; Bhatnagar, A.; Arora, D.; Sarin, R.; Saxena, S. Study of Gene Expression Profiles of Breast Cancers in Indian Women. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10018. [CrossRef]

- Hebbard, L.W.; Maurer, J.; Miller, A.; Lesperance, J.; Hassell, J.; Oshima, R.G.; Terskikh, A.V. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase Is Upregulated and Required in Mammary Tumor-Initiating Cells In vivo. Cancer Research 2010, 70, 8863–8873. [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, A.A.; Han, Y.J.; Grushko, T.A.; Mueller, J.; Gomez, M.J.; Zheng, Y.; Olopade, O.I. Subtype-specific expression of MELK is partly due to copy number alterations in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268693. [CrossRef]

- McBean, B.; Abou Zeidane, R.; Lichtman-Mikol, S.; Hauk, B.; Speers, J.; Tidmore, S.; Flores, C.L.; Rana, P.S.; Pisano, C.; Liu, M.; et al. MELK as a Mediator of Stemness and Metastasis in Aggressive Subtypes of Breast Cancer. IJMS 2025, 26, 2245. [CrossRef]

- Pickard, M.R.; Green, A.R.; Ellis, I.O.; Caldas, C.; Hedge, V.L.; Mourtada-Maarabouni, M.; Williams, G.T. Dysregulated expression of Fau and MELK is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2009, 11, R60. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I.M.; Graves, L.M. Enigmatic MELK: The controversy surrounding its complex role in cancer. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295, 8195–8203. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yang, M.; Zuo, L.; Wang, M. MELK as a potential target to control cell proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Oncol Lett 2018. [CrossRef]

- Speers, C.; Zhao, S.G.; Kothari, V.; Santola, A.; Liu, M.; Wilder-Romans, K.; Evans, J.; Batra, N.; Bartelink, H.; Hayes, D.F.; et al. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase (MELK) as a Novel Mediator and Biomarker of Radioresistance in Human Breast Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2016, 22, 5864–5875. [CrossRef]

- Bollu, L.R.; Shepherd, J.; Zhao, D.; Ma, Y.; Tahaney, W.; Speers, C.; Mazumdar, A.; Mills, G.B.; Brown, P.H. Mutant P53 induces MELK expression by release of wild-type P53-dependent suppression of FOXM1. npj Breast Cancer 2020, 6, 2. [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Mesmar, F.; Helguero, L.; Williams, C. Genome-wide effects of MELK-inhibitor in triple-negative breast cancer cells indicate context-dependent response with p53 as a key determinant. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172832. [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 131, 803–820. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, K.; Jarrett, R.F. The molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin lymphoma: Molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin lymphoma. Histopathology 2011, 58, 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Tabnak, P.; Hasanzade Bashkandi, A.; Ebrahimnezhad, M.; Soleimani, M. Forkhead box transcription factors (FOXOs and FOXM1) in glioma: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 238. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Banasavadi-Siddegowda, Y.; Mo, X.; Kim, S.-H.; Mao, P.; Kig, C.; Nardini, D.; Sobol, R.W.; Chow, L.M.L.; Kornblum, H.I.; et al. MELK-Dependent FOXM1 Phosphorylation is Essential for Proliferation of Glioma Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1051–1063. [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Banasavadi-Siddegowda, Y.K.; Joshi, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Kurt, H.; Gupta, S.; Nakano, I. Tumor-Specific Activation of the C-JUN/MELK Pathway Regulates Glioma Stem Cell Growth in a p53-Dependent Manner. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 870–881. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Joshi, K.; Ezhilarasan, R.; Myers, T.R.; Siu, J.; Gu, C.; Nakano-Okuno, M.; Taylor, D.; Minata, M.; Sulman, E.P.; et al. EZH2 Protects Glioma Stem Cells from Radiation-Induced Cell Death in a MELK/FOXM1-Dependent Manner. Stem Cell Reports 2015, 4, 226–238. [CrossRef]

- Minata, M.; Gu, C.; Joshi, K.; Nakano-Okuno, M.; Hong, C.; Nguyen, C.-H.; Kornblum, H.I.; Molla, A.; Nakano, I. Multi-Kinase Inhibitor C1 Triggers Mitotic Catastrophe of Glioma Stem Cells Mainly through MELK Kinase Inhibition. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92546. [CrossRef]

- Khurram, S.A.; Graham, S.; Shaban, M.; Qaiser, T.; Rajpoot, N.M. Classification of lung cancer histology images using patch-level summary statistics. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2018: Digital Pathology; Gurcan, M.N., Tomaszewski, J.E., Eds.; SPIE: Houston, United States, 2018; p. 44.

- Paez, J.G.; Jänne, P.A.; Lee, J.C.; Tracy, S.; Greulich, H.; Gabriel, S.; Herman, P.; Kaye, F.J.; Lindeman, N.; Boggon, T.J.; et al. EGFR Mutations in Lung Cancer: Correlation with Clinical Response to Gefitinib Therapy. Science 2004, 304, 1497–1500. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Yu, A.; He, X.; Xuan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Shi, M.; Wang, T. Bioinformatics analysis to determine the prognostic value and prospective pathway signaling of miR-126 in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1639–1639. [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Qian, C.; Ruan, Y.; Xie, J.; Luo, T.; Xu, B.; Jiang, J. Higher Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase Mrna Expression Level Is A Poor Prognostic Factor in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma Patients. Biomark. Med. 2019, 13, 1349–1361. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, B.; Lin, H.; Zhan, N.; Ren, J.; Song, W.; Han, R.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, M.; et al. AURKA, TOP2A and MELK are the key genes identified by WGCNA for the pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett 2023, 25, 238. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Li, W.; Zheng, X.; Ren, L.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Du, G. MELK is an oncogenic kinase essential for metastasis, mitotic progression, and programmed death in lung carcinoma. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 279. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, C.; An, J.; Hao, D.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Jiang, J. KLF5-induced BBOX1-AS1 contributes to cell malignant phenotypes in non-small cell lung cancer via sponging miR-27a-5p to up-regulate MELK and activate FAK signaling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021, 40, 148. [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, K.; Mataki, H.; Arai, T.; Okato, A.; Kamikawaji, K.; Kumamoto, T.; Hiraki, T.; Hatanaka, K.; Inoue, H.; Seki, N. The microRNA expression signature of small cell lung cancer: tumor suppressors of miR-27a-5p and miR-34b-3p and their targeted oncogenes. J Hum Genet 2017, 62, 671–678. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Kato, T.; Olugbile, S.; Tamura, K.; Chung, S.; Miyamoto, T.; Matsuo, Y.; Salgia, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Park, J.-H. Effective growth-suppressive activity of maternal embryonic leucine-zipper kinase (MELK) inhibitor against small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 13621–13633. [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention. pg 2019, 14, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, T.; Xing, X.-F.; Cheng, X.; Du, H.; Wen, X.-Z.; Ji, J.-F. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase serves as a poor prognosis marker and therapeutic target in gastric cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 6266–6280. [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, M.; Cao, C.; Kang, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J. Upregulation of MELK promotes chemoresistance and induces macrophage M2 polarization via CSF-1/JAK2/STAT3 pathway in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell Int 2024, 24, 287. [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Qu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Su, L.; Zhou, Q.; Yan, M.; Li, C.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, B. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase enhances gastric cancer progression via the FAK/Paxillin pathway. Mol Cancer 2014, 13, 100. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Translational Oncology 2021, 14, 101174. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhan, W.; Guo, W.; Hu, F.; Qin, J.; Li, R.; Liao, X. MELK Accelerates the Progression of Colorectal Cancer via Activating the FAK/Src Pathway. Biochem Genet 2020, 58, 771–782. [CrossRef]

- Ward, W.H.; Farma, J.M. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy; Codon Publications Copyright © 2017 Codon Publicatio, 2017.

- Miller, A.J.; Mihm Jr, M.C. Melanoma. NEJM 2006, 355, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Jaune, E.; Cavazza, E.; Ronco, C.; Grytsai, O.; Abbe, P.; Tekaya, N.; Zerhouni, M.; Beranger, G.; Kaminski, L.; Bost, F.; et al. Discovery of a new molecule inducing melanoma cell death: dual AMPK/MELK targeting for novel melanoma therapies. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 64. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Kong, S.N.; Chen, J.; Shi, M.; Sekar, K.; Seshachalam, V.P.; Rajasekaran, M.; Goh, B.K.P.; Ooi, L.L.; Hui, K.M. MELK is an oncogenic kinase essential for early hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Cancer Letters 2016, 383, 85–93. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, Z. Comprehensive analysis to identify noncoding RNAs mediated upregulation of maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) correlated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging 2022, 14, 3973–3988. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhai, X.; Gao, L.; Yang, M.; An, B.; Xia, T.; Du, G.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; et al. MELK promotes HCC carcinogenesis through modulating cuproptosis-related gene DLAT-mediated mitochondrial function. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 733. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Zhu, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, B.; Fang, S.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Qiu, R.; et al. Tumor cell-intrinsic MELK enhanced CCL2-dependent immunosuppression to exacerbate hepatocarcinogenesis and confer resistance of HCC to radiotherapy. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 137. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA CANCER J CLIN 2022, 72, 409–436.

- Antoni, S.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Znaor, A. Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Overview and Recent Trends. European urology 2017, 71, 69–108. [CrossRef]

- Mahdavifar, N.; MOHAMMADIAN, M.; GHONCHEH, M.; SALEHINIYA, H. Incidence, Mortality and Risk Factors of Kidney Cancer in the World. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1013.