Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies

2.2. Preparation of Cell Lines

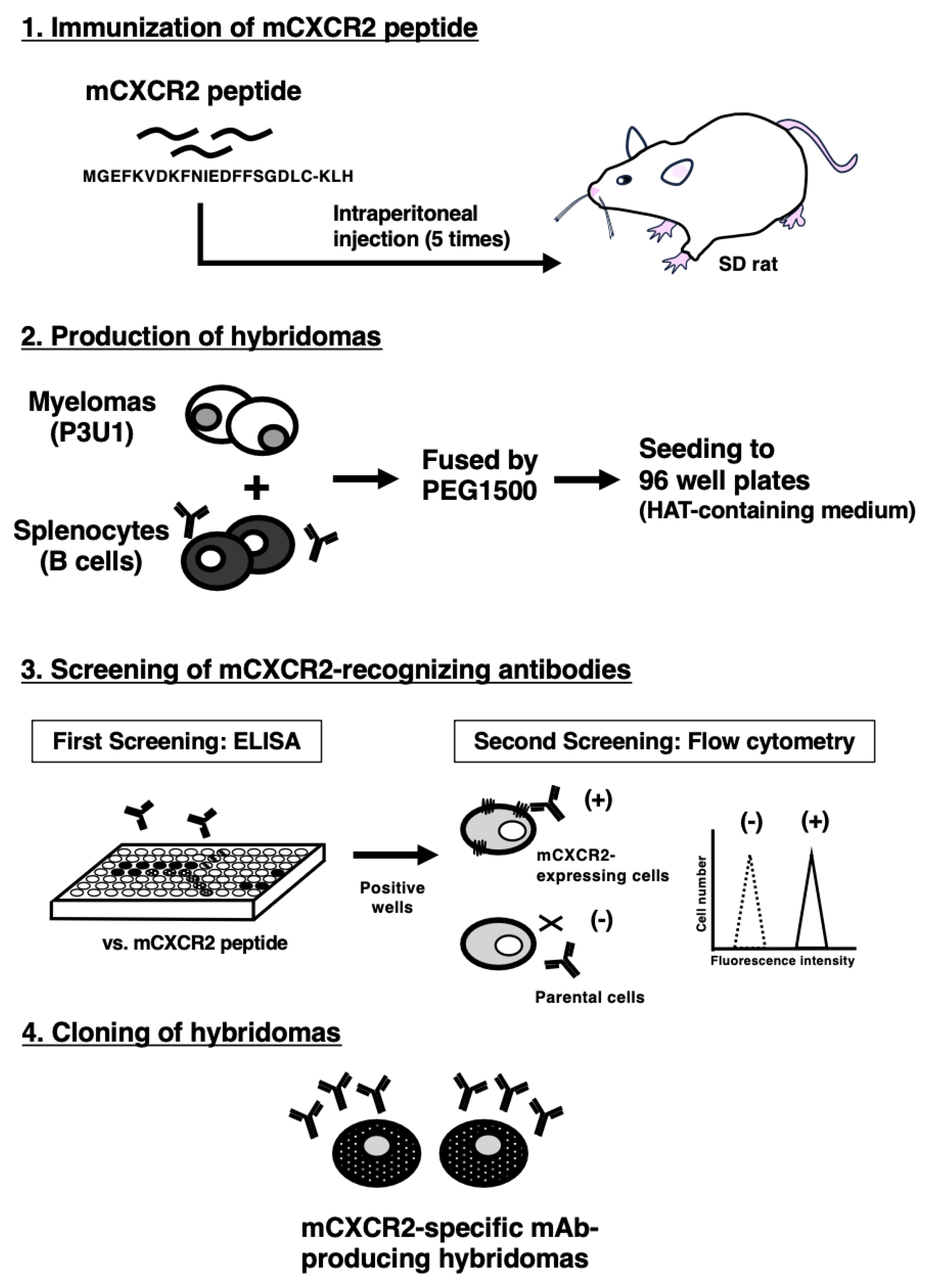

2.3. Production of Hybridomas

2.4. ELISA

2.5. Flow Cytometry

2.6. Determination of the Binding Affinity by Flow Cytometry

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. Immunohistochemical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Development of Anti-mCXCR2 mAbs

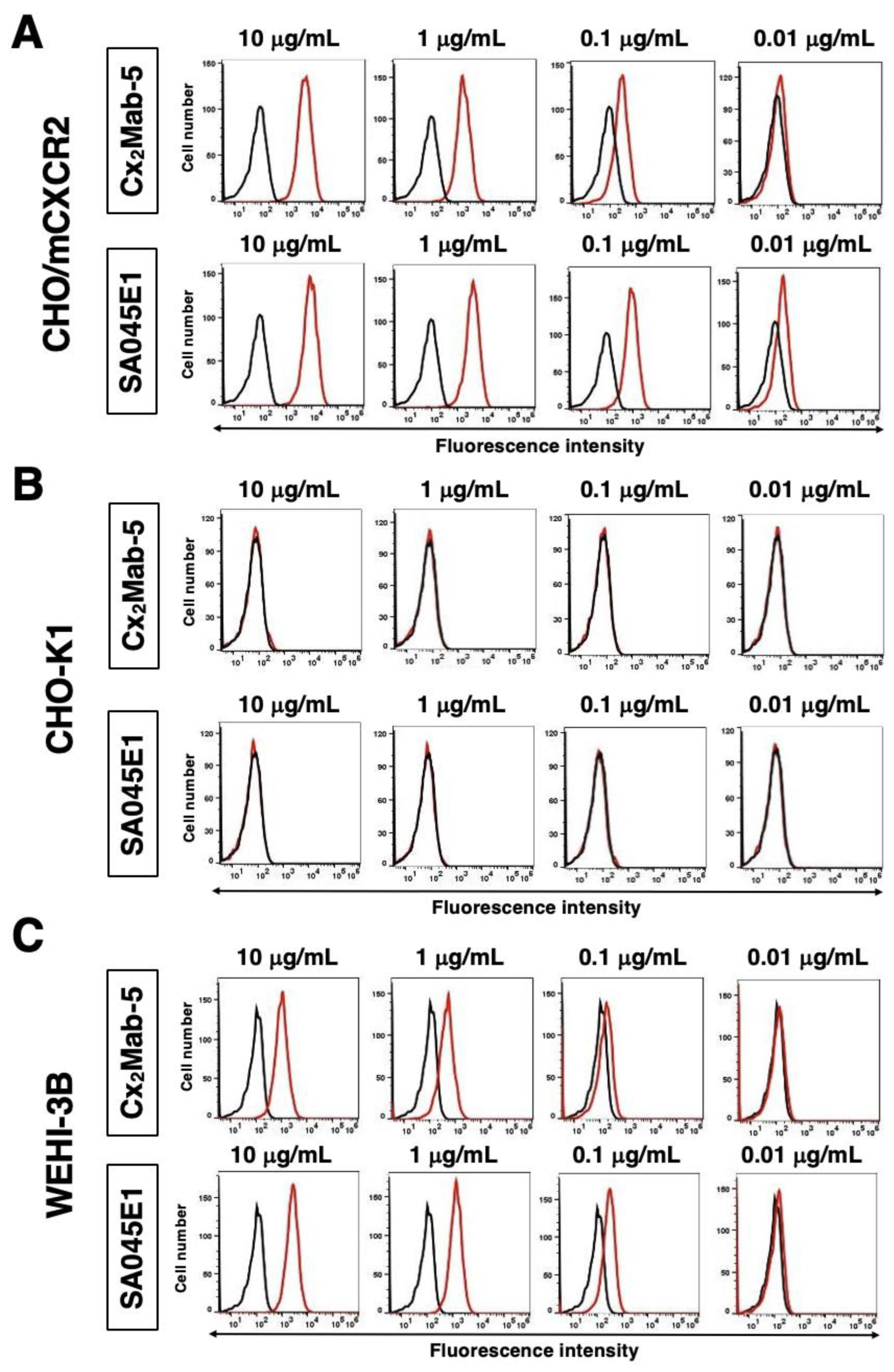

3.2. Flow Cytometry Using Cx2Mab-5

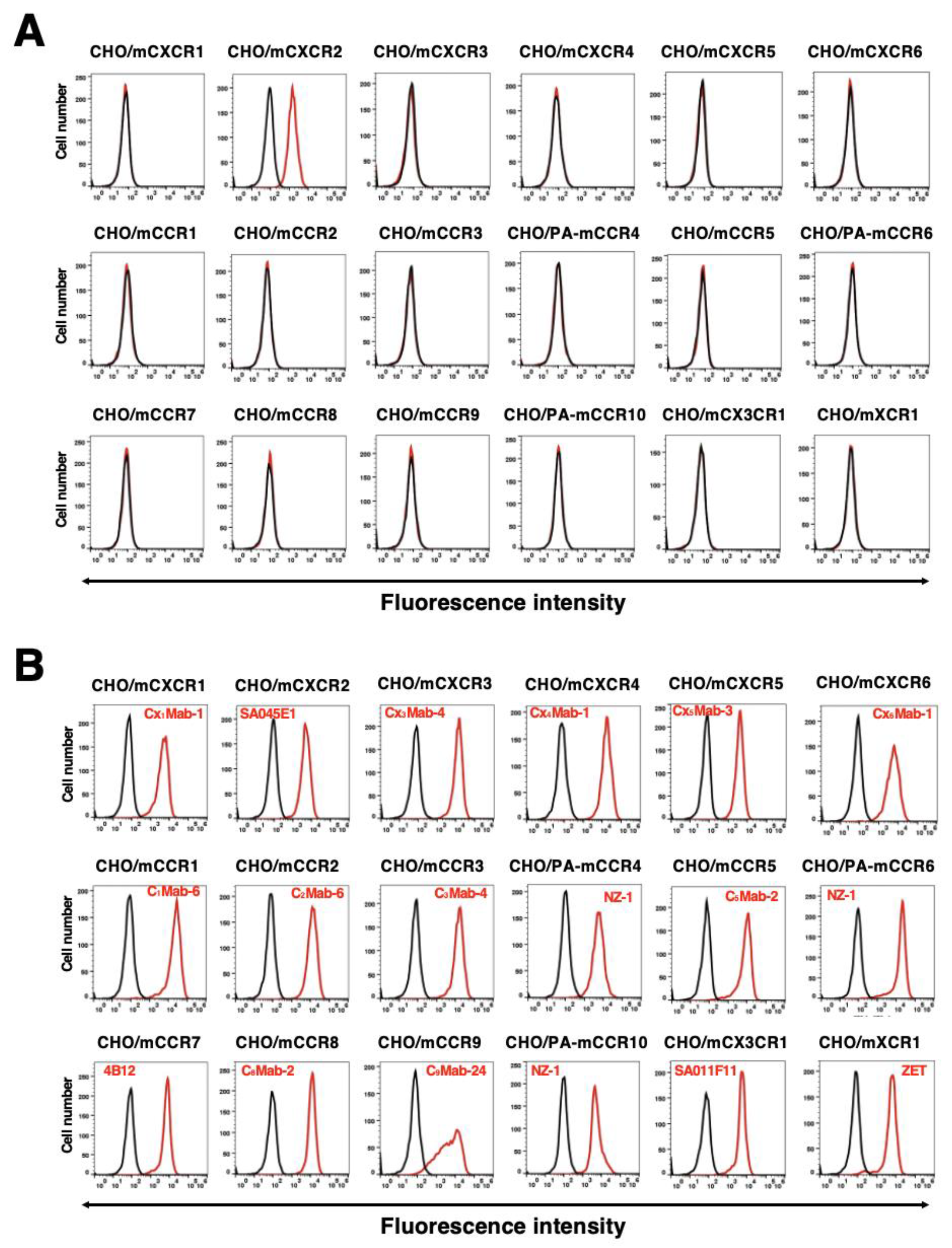

3.3. The Specificity of Cx2Mab-5

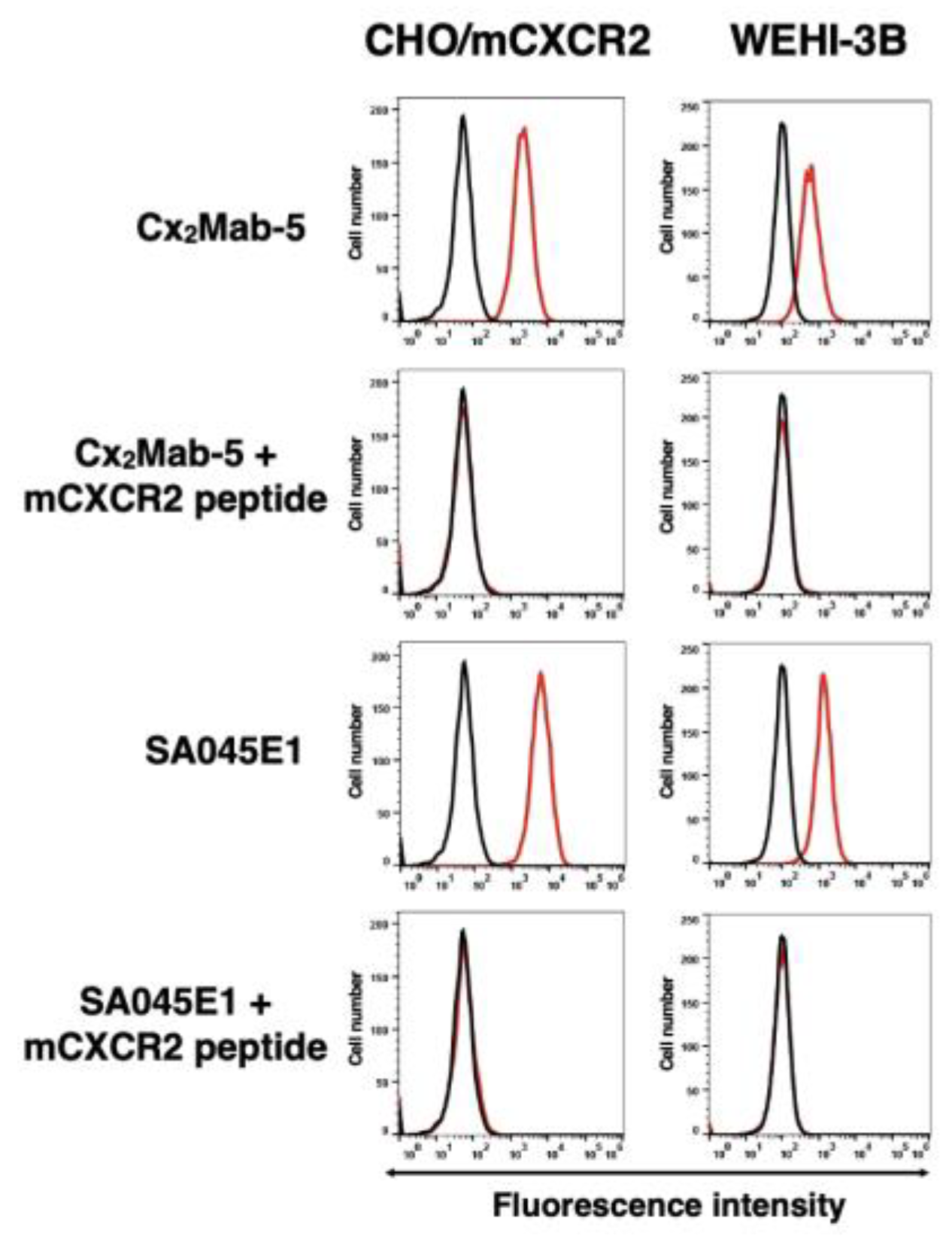

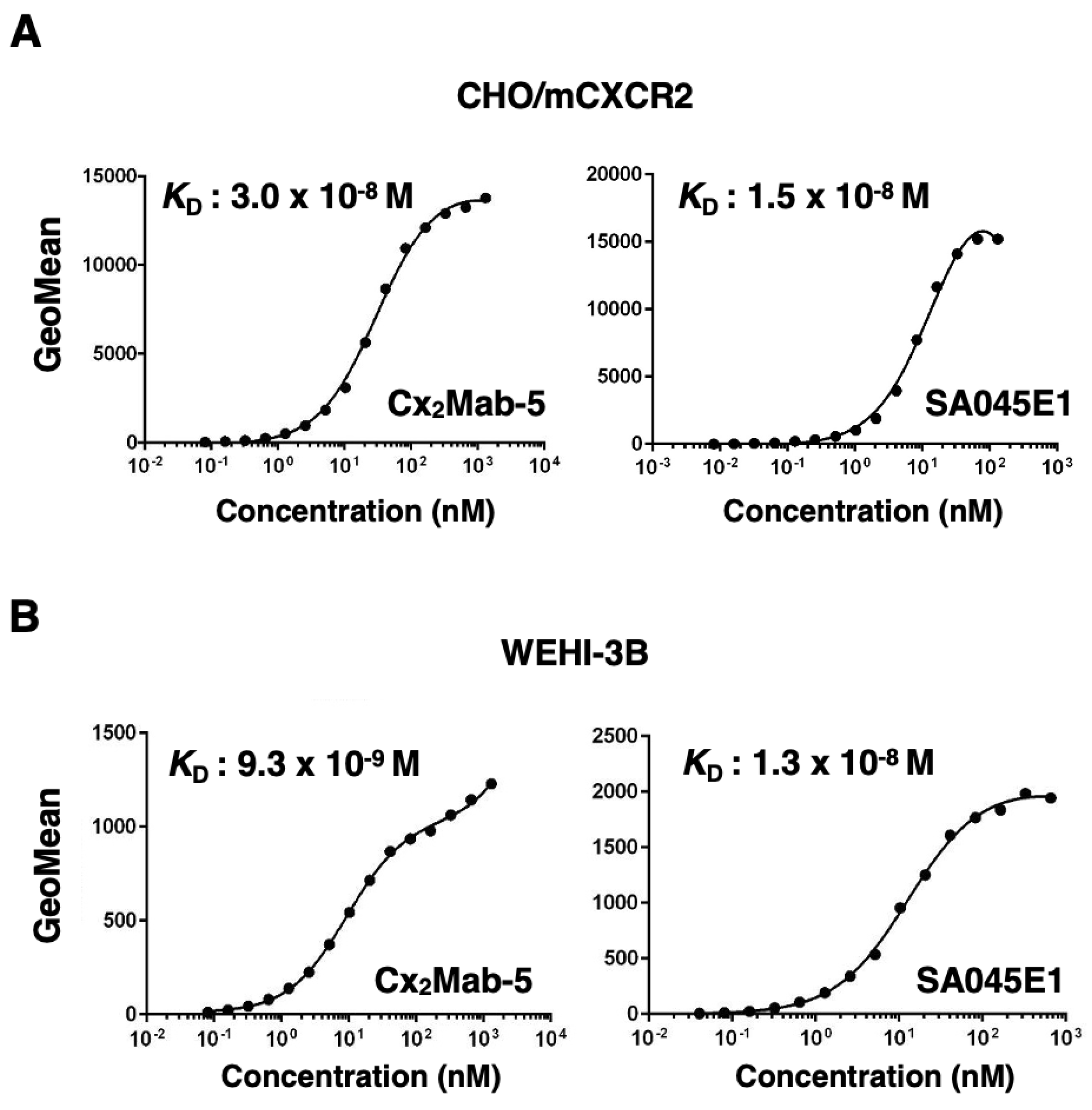

3.4. Determination of the Binding Affinity of Cx2Mab-5

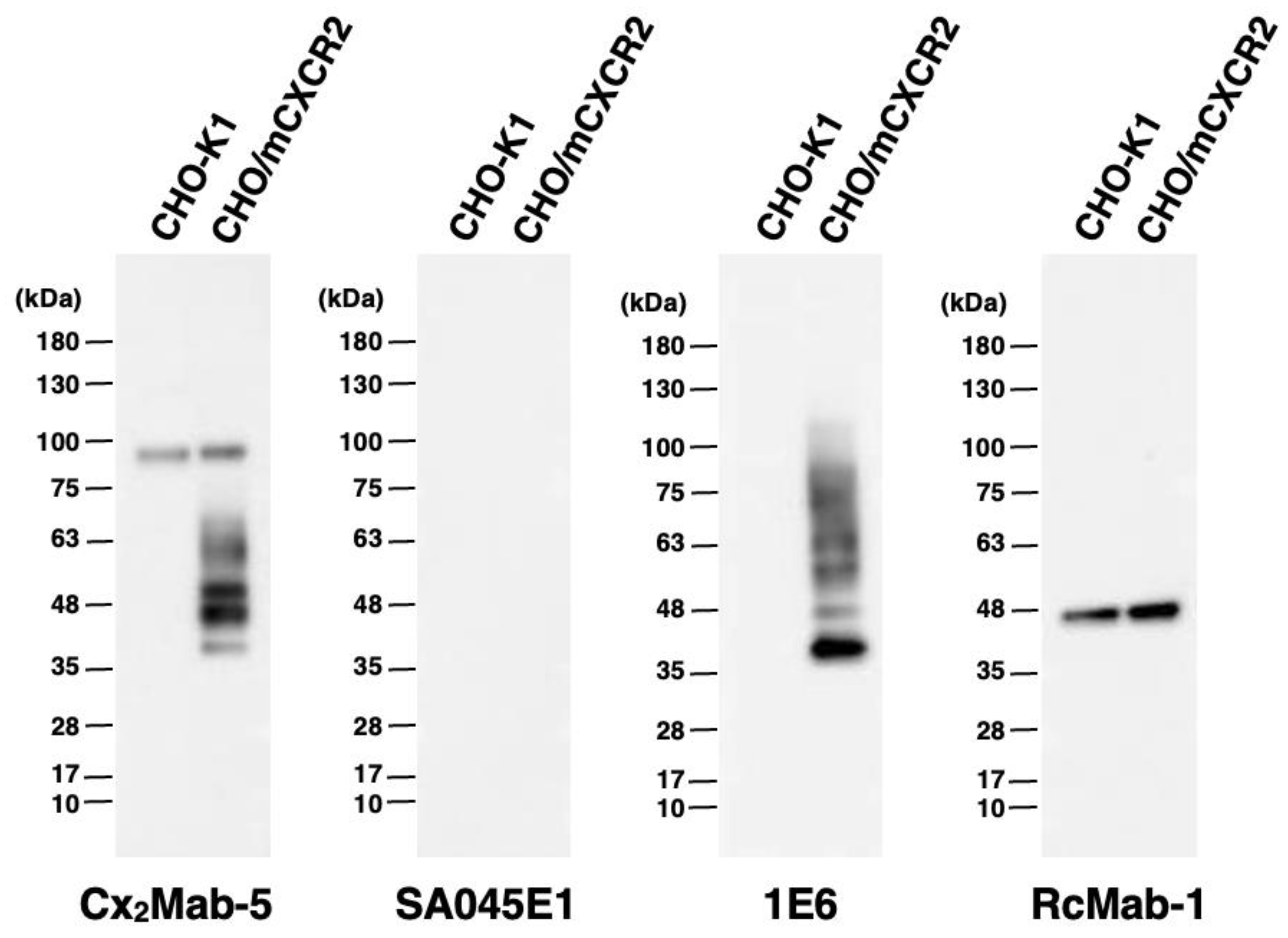

3.5. Western Blot Analyses Using Cx2Mab-5

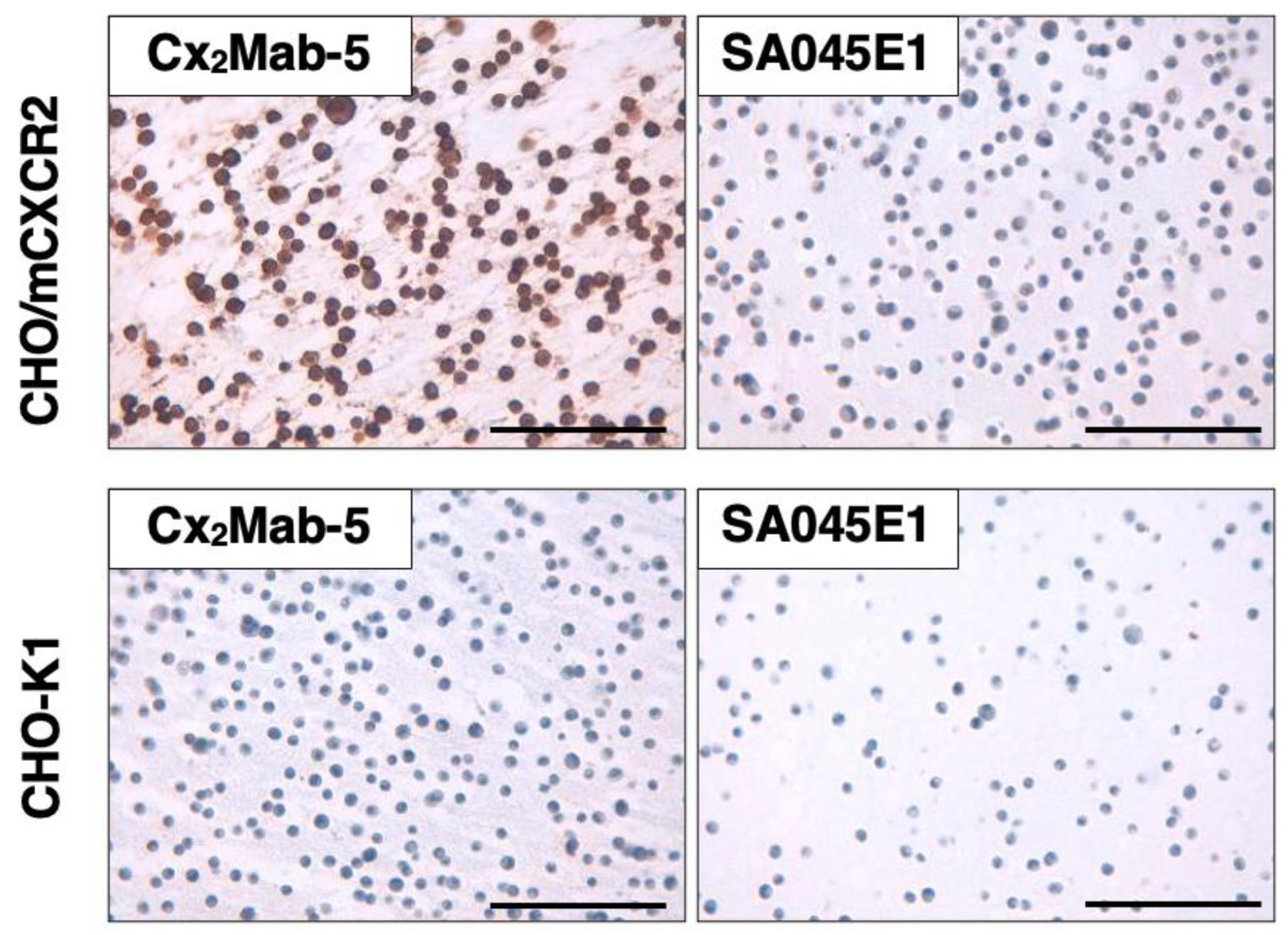

3.6. Immunohistochemistry Using Cx2Mab-5

4. Discussion

Funding

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Cotarelo, P.; Gómez-Moreira, C.; Criado-García, O.; Sánchez, L.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J.L. Beyond Chemoattraction: Multifunctionality of Chemokine Receptors in Leukocytes. Trends in Immunology 2017, 38, 927-941. [CrossRef]

- Nagarsheth, N.; Wicha, M.S.; Zou, W. Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 559-572. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, L.; Rajarathnam, K. Structural basis of chemokine receptor function--a model for binding affinity and ligand selectivity. Biosci Rep 2006, 26, 325-339. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.P. Chemokines, chemokine receptors and allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2001, 124, 423-431. [CrossRef]

- Shachar, I.; Karin, N. The dual roles of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the regulation of autoimmune diseases and their clinical implications. J Leukoc Biol 2013, 93, 51-61. [CrossRef]

- O’Hayre, M.; Salanga, C.L.; Handel, T.M.; Allen, S.J. Chemokines and cancer: migration, intracellular signalling and intercellular communication in the microenvironment. Biochem J 2008, 409, 635-649. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Sano, F.K.; Sharma, S.; Ganguly, M.; Mishra, S.; Dalal, A.; Akasaka, H.; Kobayashi, T.A.; Zaidi, N.; Tiwari, D.; et al. Molecular basis of promiscuous chemokine binding and structural mimicry at the C-X-C chemokine receptor, CXCR2. Mol Cell 2025, 85, 976-988.e979. [CrossRef]

- Lazennec, G.; Rajarathnam, K.; Richmond, A. CXCR2 chemokine receptor - a master regulator in cancer and physiology. Trends Mol Med 2024, 30, 37-55. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Kurth, E.A.; Budean, D.; Momplaisir, N.; Qu, E.; Simien, J.M.; Orellana, G.E.; Brautigam, C.A.; Smrcka, A.V.; Haglund, E. Biophysical characterization of the CXC chemokine receptor 2 ligands. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0298418. [CrossRef]

- Lazennec, G.; Richmond, A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2010, 16, 133-144. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Geng, H.; Yang, X.; Ji, S.; Liu, Z.; Feng, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; et al. Targeting the immune privilege of tumor-initiating cells to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 2064-2081.e2019. [CrossRef]

- Delobel, P.; Ginter, B.; Rubio, E.; Balabanian, K.; Lazennec, G. CXCR2 intrinsically drives the maturation and function of neutrophils in mice. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1005551. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Shi, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhang, X.; Kambara, H.; Su, J.; Yu, H.; Park, S.-Y.; Guo, R.; Ren, Q.; et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and infection. Nature Immunology 2020, 21, 1119-1133. [CrossRef]

- Adrover, J.M.; Del Fresno, C.; Crainiciuc, G.; Cuartero, M.I.; Casanova-Acebes, M.; Weiss, L.A.; Huerga-Encabo, H.; Silvestre-Roig, C.; Rossaint, J.; Cossío, I.; et al. A Neutrophil Timer Coordinates Immune Defense and Vascular Protection. Immunity 2019, 50, 390-402.e310. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Rossaint, J.; Ludwig, N.; Mersmann, S.; Kötting, N.; Grenzheuser, J.; Schemmelmann, L.; Oguama, M.; Margraf, A.; Block, H.; et al. Alveolar epithelial and vascular CXCR2 mediates transcytosis of CXCL1 in inflamed lungs. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 4846. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Li, W.; Li, H. C-X-C motif chemokine receptor type 2 correlates with higher disease stages and predicts worse prognosis, and its downregulation enhances chemotherapy sensitivity in triple-negative breast cancer. Translational Cancer Research 2020, 9, 840-848.

- Zhang, L.; Gu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, T.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L. M2 macrophages promote PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer via secreting CXCL1. Pathol Res Pract 2024, 260, 155458. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, W.; Shi, G.; Hao, M.; Wang, Y.; Yao, M.; Huang, Y.; Du, L.; Zhang, X.; Ye, D.; et al. Targeting HIC1/TGF-β axis-shaped prostate cancer microenvironment restrains its progression. Cell Death & Disease 2022, 13, 624. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, W.; Hao, W.; Gong, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qian, Z.; Xu, K.; Cai, W.; Gao, Y. CXCL3/TGF-β-mediated crosstalk between CAFs and tumor cells augments RCC progression and sunitinib resistance. iScience 2024, 27, 110224. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zheng, R.; Xie, Y.; Wei, X.; Wu, J.; Shen, H.; Ye, M.; et al. IFNα-induced BST2(+) tumor-associated macrophages facilitate immunosuppression and tumor growth in pancreatic cancer by ERK-CXCL7 signaling. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 114088. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X. CXCL6-CXCR2 axis-mediated PD-L2(+) mast cell accumulation shapes the immunosuppressive microenvironment in osteosarcoma. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34290. [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.A.; Woods, E.; Hoffmeyer, E.; Schaller, K.L.; Cruz-Cruz, J.; Fernandez, J.; Tufa, D.; Kooiman, B.; Hall, S.C.; Jones, D.; et al. Directing B7-H3 chimeric antigen receptor T cell homing through IL-8 induces potent antitumor activity against pediatric sarcoma. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Talbot, L.J.; Chabot, A.; Ross, A.B.; Beckett, A.; Nguyen, P.; Fleming, A.; Chockley, P.J.; Shepphard, H.; Wang, J.; Gottschalk, S.; et al. Redirecting B7-H3.CAR T Cells to Chemokines Expressed in Osteosarcoma Enhances Homing and Antitumor Activity in Preclinical Models. Clin Cancer Res 2024, 30, 4434-4449. [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Li, G.; Nanamiya, R.; Tateyama, N.; Isoda, Y.; Okada, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; et al. Development of a Novel Anti-Mouse CCR6 Monoclonal Antibody (C(6)Mab-13) by N-Terminal Peptide Immunization. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 343-349. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, K.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Cx(6)Mab-1: A Novel Anti-Mouse CXCR6 Monoclonal Antibody Established by N-Terminal Peptide Immunization. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 133-141. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tanaka, T.; Ouchida, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Cx(1)Mab-1: A Novel Anti-mouse CXCR1 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 59-66. [CrossRef]

- Ouchida, T.; Isoda, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Tanaka, T.; Handa, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a Novel Anti-Mouse CCR1 Monoclonal Antibody C(1)Mab-6. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Ouchida, T.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Cx(4)Mab-1: A Novel Anti-Mouse CXCR4 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 10-16. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; Asano, T.; Saito, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-Mouse CCR2 Monoclonal Antibody (C(2)Mab-6) by N-Terminal Peptide Immunization. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 80-86. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Nanamiya, R.; Takei, J.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Hosono, H.; Sano, M.; Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of Anti-Mouse CC Chemokine Receptor 8 Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 65-70. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Isoda, Y.; Asano, T.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Handa, S.; Takahashi, N.; Okuno, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; et al. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Human CCR9 Monoclonal Antibody (C(9)Mab-11) by N-Terminal Peptide Immunization. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 303-310. [CrossRef]

- Ikota, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, H.; Kato, Y.; Ishizawa, K.; Hirose, T.; Yokoo, H. Evaluation of IDH1 status in diffusely infiltrating gliomas by immunohistochemistry using anti-mutant and wild type IDH1 antibodies. Brain Tumor Pathol 2015, 32, 237-244. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a high-affinity anti-mouse CXCR5 monoclonal antibody for flow cytometry. MI 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Satofuka, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. C7Mab-2: A novel monoclonal antibody against mouse CCR7 established by immunization of the extracellular loop domain. MI 2025. [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Egan, K.M. Exploring the prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in cancer. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 19673. [CrossRef]

- Valero, C.; Lee, M.; Hoen, D.; Weiss, K.; Kelly, D.W.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Paik, P.K.; Plitas, G.; Ladanyi, M.; Postow, M.A.; et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 729. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sharp, A.; Gurel, B.; Crespo, M.; Figueiredo, I.; Jain, S.; Vogl, U.; Rekowski, J.; Rouhifard, M.; Gallagher, L.; et al. Targeting myeloid chemotaxis to reverse prostate cancer therapy resistance. Nature 2023, 623, 1053-1061. [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Kupnicka, P.; Chlubek, M.; Gorący, J.; Gutowska, I.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. CXCR2 Receptor: Regulation of Expression, Signal Transduction, and Involvement in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Maas, R.R.; Soukup, K.; Fournier, N.; Massara, M.; Galland, S.; Kornete, M.; Wischnewski, V.; Lourenco, J.; Croci, D.; Álvarez-Prado, Á.F.; et al. The local microenvironment drives activation of neutrophils in human brain tumors. Cell 2023, 186, 4546-4566.e4527. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, W.; Cao, P.; Wu, S.; Li, M.; Li, W.; et al. Disease-specific suppressive granulocytes participate in glioma progression. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 115014. [CrossRef]

- Alshetaiwi, H.; Pervolarakis, N.; McIntyre, L.L.; Ma, D.; Nguyen, Q.; Rath, J.A.; Nee, K.; Hernandez, G.; Evans, K.; Torosian, L.; et al. Defining the emergence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer using single-cell transcriptomics. Sci Immunol 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Highfill, S.L.; Cui, Y.; Giles, A.J.; Smith, J.P.; Zhang, H.; Morse, E.; Kaplan, R.N.; Mackall, C.L. Disruption of CXCR2-mediated MDSC tumor trafficking enhances anti-PD1 efficacy. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 237ra267. [CrossRef]

- Nishinakamura, H.; Shinya, S.; Irie, T.; Sakihama, S.; Naito, T.; Watanabe, K.; Sugiyama, D.; Tamiya, M.; Yoshida, T.; Hase, T.; et al. Coactivation of innate immune suppressive cells induces acquired resistance against combined TLR agonism and PD-1 blockade. Sci Transl Med 2025, 17, eadk3160. [CrossRef]

- Banuelos, A.; Zhang, A.; Berouti, H.; Baez, M.; Yılmaz, L.; Georgeos, N.; Marjon, K.D.; Miyanishi, M.; Weissman, I.L. CXCR2 inhibition in G-MDSCs enhances CD47 blockade for melanoma tumor cell clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2318534121. [CrossRef]

- Bazzichetto, C.; Di Martile, M.; Del Bufalo, D.; Milella, M.; Conciatori, F. Induction of cell death by the CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 in colorectal cancer and stromal cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 188, 118203. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, P.; Dos Santos, M.; Sitterle, L.; Tarlet, G.; Lavigne, J.; Liu, W.; Gerbé de Thoré, M.; Clémenson, C.; Meziani, L.; Schott, C.; et al. Non-homogenous intratumor ionizing radiation doses synergize with PD1 and CXCR2 blockade. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8845. [CrossRef]

- Bilusic, M.; Heery, C.R.; Collins, J.M.; Donahue, R.N.; Palena, C.; Madan, R.A.; Karzai, F.; Marté, J.L.; Strauss, J.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; et al. Phase I trial of HuMax-IL8 (BMS-986253), an anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody, in patients with metastatic or unresectable solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 240. [CrossRef]

- Prado, G.N.; Suetomi, K.; Shumate, D.; Maxwell, C.; Ravindran, A.; Rajarathnam, K.; Navarro, J. Chemokine Signaling Specificity: Essential Role for the N-Terminal Domain of Chemokine Receptors. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 8961-8968. [CrossRef]

- Urvas, L.; Kellenberger, E. Structural Insights into Molecular Recognition and Receptor Activation in Chemokine–Chemokine Receptor Complexes. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 66, 7070-7085. [CrossRef]

- Rahimizadeh, P.; Kim, S.; Yoon, B.J.; Jeong, Y.; Lim, S.; Jeon, H.; Lim, H.J.; Park, S.H.; Park, S.I.; Kong, D.H.; et al. Novel CXCR2 antibodies exhibit enhanced anti-tumor activity in pancreatic cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 185, 117966. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.A.; Finney, O.; Annesley, C.; Brakke, H.; Summers, C.; Leger, K.; Bleakley, M.; Brown, C.; Mgebroff, S.; Kelly-Spratt, K.S.; et al. Intent-to-treat leukemia remission by CD19 CAR T cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood 2017, 129, 3322-3331. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Rivière, I.; Gonen, M.; Wang, X.; Sénéchal, B.; Curran, K.J.; Sauter, C.; Wang, Y.; Santomasso, B.; Mead, E.; et al. Long-Term Follow-up of CD19 CAR Therapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 449-459. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Brawley, V.S.; Hegde, M.; Robertson, C.; Ghazi, A.; Gerken, C.; Liu, E.; Dakhova, O.; Ashoori, A.; Corder, A.; et al. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) -Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells for the Immunotherapy of HER2-Positive Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33, 1688-1696. [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Zeng, Q.; Chang, D. Efficiency of CAR-T Therapy for Treatment of Solid Tumor in Clinical Trials: A Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers 2019, 2019, 3425291. [CrossRef]

- Giudice, A.M.; Roth, S.L.; Matlaga, S.; Cresswell-Clay, E.; Mishra, P.; Schürch, P.M.; Boateng-Antwi, K.A.M.; Samanta, M.; Pascual-Pasto, G.; Zecchino, V.; et al. Reprogramming the neuroblastoma tumor immune microenvironment to enhance GPC2 CAR T cells. Mol Ther 2025, 33, 4552-4569. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Zou, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Tasiheng, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Ectopic CXCR2 expression cells improve the anti-tumor efficiency of CAR-T cells and remodel the immune microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2024, 73, 61. [CrossRef]

- Hosking, M.P.; Shirinbak, S.; Omilusik, K.; Chandra, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Gentile, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Shrestha, B.; Grant, J.; Boyett, M.; et al. Preferential tumor targeting of HER2 by iPSC-derived CAR T cells engineered to overcome multiple barriers to solid tumor efficacy. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1087-1101.e1084. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Ling, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. Radiotherapy enhances the anti-tumor effect of CAR-NK cells for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 929. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).