1. Introduction

Urban kampungs in Indonesia, particularly in large cities like Surabaya, represent a unique form of settlement where formal and informal practices intersect. While often broadly categorized as informal settlements or slums, kampungs differ significantly in their historical, cultural, and spatial development trajectories. They are not merely areas of poverty or illegality but are dynamic, adaptive communities characterized by strong social networks, localized governance, and a deep sense of place. However, in the context of rapid urbanization, environmental degradation, and climate change, kampungs are increasingly exposed to a range of multi-dimensional hazards that amplify their vulnerability. In Surabaya, kampungs face overlapping risks that span environmental, infrastructural and social domains. Tidal flooding in low-lying coastal areas, infrastructural hazards such as faulty electrical systems, and social insecurity driven by unemployment and weakened social protection systems are among the most pressing threats. Despite these challenges, kampung residents have developed diverse informal strategies for adaptation and resilience, rooted in collective action and everyday practices. These locally grounded responses, however, often remain underrecognized in top-down urban planning frameworks, which tend to treat risk management as a technocratic exercise, sidelining lived experiences and community agency.

This study adopts a community-based participatory risk analysis (CBPRA) [

1] framework to understand and evaluate multi-hazard vulnerabilities in kampung environments. Building on concepts of social vulnerability [

2] and participatory governance [

3], CBPRA emphasizes the need to integrate local knowledge, adaptive strategies, and community organization into urban risk governance. It challenges the prevailing technocratic approaches by reconceptualizing risk as socially produced and contextually experienced, thereby advocating for more inclusive and place-based strategies in disaster risk management and urban planning.

The research focuses on selected kampungs in Surabaya: Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran, Kampung Kue Rungkut, and Kampung Kota Ketandan-Kebangsren, chosen to reflect a diversity of hazard exposures and socio-spatial conditions. By examining these cases, the study aims to identify and categorize the types of multi-hazard vulnerabilities present, analyze how these vulnerabilities are perceived and addressed by residents, and assess the potential contribution of community-based risk analysis to enhancing urban resilience at the kampung scale. The study is guided by three main research questions: (1) What types of multi-hazard vulnerabilities are present in urban kampungs of Surabaya, and how do they interact? (2) How do kampung residents perceive, experience, and respond to these risks in their daily lives? and (3) What role can community-based risk analysis play in supporting more inclusive and context-sensitive urban risk governance? By addressing these questions, the research seeks to contribute to a deeper understanding of urban vulnerability and resilience in the specific context of Surabaya’s kampungs, with the aim of informing more grounded and effective urban risk management strategies.

1.1. Urban Kampungs and Informal Settlements in Surabaya

A key limitation in research on urban kampungs in Indonesia lies in the challenges of their conceptualization. This complexity is compounded by the diversity of kampungs, which range from thriving, community-driven spaces to areas grappling with poverty and infrastructural inadequacies. Globally, kampungs are often oversimplified and categorized alongside informal settlements such as favelas, villas miseria, and other slum typologies. However, such comparisons risk overlooking the localized adaptations, socio-cultural practices, and spatial dynamics that make kampungs a distinctive form of urban living. In urban studies discourse, kampungs are frequently described as slums [

4], but this characterization does not fully capture their embedded social structures, economic significance, or adaptive capacities.

According to UN-Habitat [

5], informal settlements are defined by characteristics such as insecure land tenure, inadequate access to basic services, and housing that does not comply with formal regulations. While many kampungs in Surabaya exhibit these traits, they also demonstrate forms of resilience and solidarity that challenge deficit-based narratives. Communities within kampungs often engage in collective practices to improve their living environments, underscoring the need for more nuanced interpretations of informality that go beyond infrastructural deficiencies.

In recent years, the development of kampungs in Surabaya has received increased attention, partly due to the city's efforts to balance urban expansion with the preservation of local culture and social wellbeing. As a form of urban informality, kampungs are traditional settlements that resemble rural villages, yet are situated within urban contexts. Although the term "kampung" shares linguistic similarities with "kampong" used in other parts of Southeast Asia, its meaning in Indonesia is uniquely rooted in localized practices of self-help housing, community governance, and social cohesion [

6]. The kampung is not merely a spatial typology but represents a socio-cultural institution where communal relationships and informal governance systems are integral to everyday life.

Kampungs in Indonesia largely embody the principles of self-help housing, where construction and improvements occur incrementally based on the evolving needs and resources of residents. This bottom-up process often involves collaborative labor, flexible design adjustments, and community-organized initiatives to upgrade homes and neighborhood infrastructure. Kampungs provide affordable housing options for low-income groups while simultaneously fostering a sense of belonging and autonomy that is often absent in formal housing developments. They also contribute significantly to the local economy through informal businesses, supporting livelihoods and enhancing neighborhood resilience [

7]. The socio-economic functions and communal identity embedded in kampungs highlight their vital role in urban development beyond conventional planning paradigms.

In Surabaya, kampungs remain a core component of the city’s social and spatial fabric. They serve not only as residential areas but also as centers of cultural preservation and local economic activity. Recognizing their potential, the Surabaya City Government initiated the Kampung Unggulan ("Prominent Kampung") program in 2010, aiming to transform kampungs into hubs for small and medium-sized industries. The program provides facilitation in legalizing micro-enterprises, obtaining trading licenses, and achieving

halal certifications, thereby fostering entrepreneurship while preserving traditional community structures. Successful examples of this initiative include Kampung Kue (Cake Village), Kampung Kerupuk (Cracker Village), and Kampung Tas (Bag Village) [

8]. These programs illustrate how kampungs can evolve into dynamic spaces of innovation and production, reinforcing their role as critical contributors to Surabaya’s economic vitality and urban identity.

1.2. Multi-hazard Urban Vulnerabilities

Urban areas are increasingly exposed to multi-hazard vulnerabilities that intersect environmental, economic, infrastructural and social domains. These vulnerabilities are not isolated but often interact, creating complex risk landscapes that disproportionately affect marginalized populations. In particular, daily risks such as economic instability and insufficient income generation [

9] can compound broader systemic vulnerabilities, entrenching cycles of urban poverty and insecurity.

Natural hazards remain a critical threat to urban systems. Disasters such as earthquakes and floods place substantial pressure on infrastructure and social networks, with the frequency and severity of some of the hazards often exacerbated by climate change. Economic vulnerabilities, including high unemployment rates, income inequality, and limited fiscal resilience, further undermine urban stability. Inflationary pressures and economic downturns increase the susceptibility of urban communities to shocks, making recovery more difficult and prolonging disruption.

Environmental pressures, such as declining green space coverage, urban heat island effects, and pollution of air and water systems, also significantly impact urban resilience [

10]. The lack of ecological buffers not only deteriorates living conditions but also amplifies the effects of natural hazards. Social vulnerabilities are deeply interconnected with these environmental and economic factors. Disruptions in healthcare, education, and public safety systems can cascade across sectors, disproportionately affecting low-income groups, migrants, and single-income households [

11].

Moreover, urban vulnerabilities are dynamic rather than static. Changing patterns of waste management, industrial emissions, and technological risks such as cyber-attacks or infrastructure failures represent evolving threats that require adaptive governance strategies. These dynamic obstacles demand continuous monitoring and policy flexibility to maintain urban resilience in the face of shifting hazards.

Historic urban areas also present unique vulnerability profiles. Aging infrastructure, heritage conservation challenges, and limited retrofitting capabilities increase the physical vulnerability of historic districts. Simultaneously, the social vulnerability of residents, often exacerbated by limited access to resources and preparedness programs, further amplifies disaster risks in these areas [

12]. The strength of local networks and community-based preparedness strategies becomes crucial in mitigating the impacts of hazards on both the built environment and social structures.

In highly exposed urban zones, vulnerability is further influenced by socio-economic status, social identities, and the quality of community support networks. Populations such as the elderly, disabled, and homeless are particularly susceptible due to constrained access to services and institutional support [

13]. The compounding effect of multiple vulnerabilities highlights the need for integrated, multi-sectoral strategies to address urban risk comprehensively.

1.3. Community-based Participatory Risk Analysis Approach

Enhancing urban resilience requires a shift from top-down disaster management models toward more integrated, participatory approaches that engage communities directly in risk assessment and mitigation. Community-based participatory risk analysis (CBPRA) [

1] offers a critical framework for identifying, understanding, and addressing urban vulnerabilities through localized engagement, collective preparedness, and adaptive strategies. By involving residents in decision-making processes, risk management initiatives become more contextually grounded and responsive to the specific conditions and capacities of different communities.

Integrated community services play a vital role in facilitating this approach. Strengthening policy implementation, supporting participatory urban strategies, and investing in sustainable, long-term initiatives are essential to ensure that resilience efforts are not merely reactive but also preventive [

14]. Early interventions, informed by community input, can help mitigate emerging risks before they escalate into crises. CBPRA is most effective when supported by strong institutional frameworks that align with local urban resilience strategies, ensuring that community actions are systematically incorporated into broader governance systems.

Qualitative methods, including in-depth interviews, participatory mapping, and focus group discussions, are particularly valuable in CBPRA. These tools capture nuanced insights into the adaptive capacities of communities and reveal subgroup-specific vulnerabilities that are often invisible in conventional risk assessments ([

13]. Understanding the differentiated needs within communities, such as those of the elderly, migrants, or low-income groups, is essential for designing inclusive strategies that leave no population group behind.

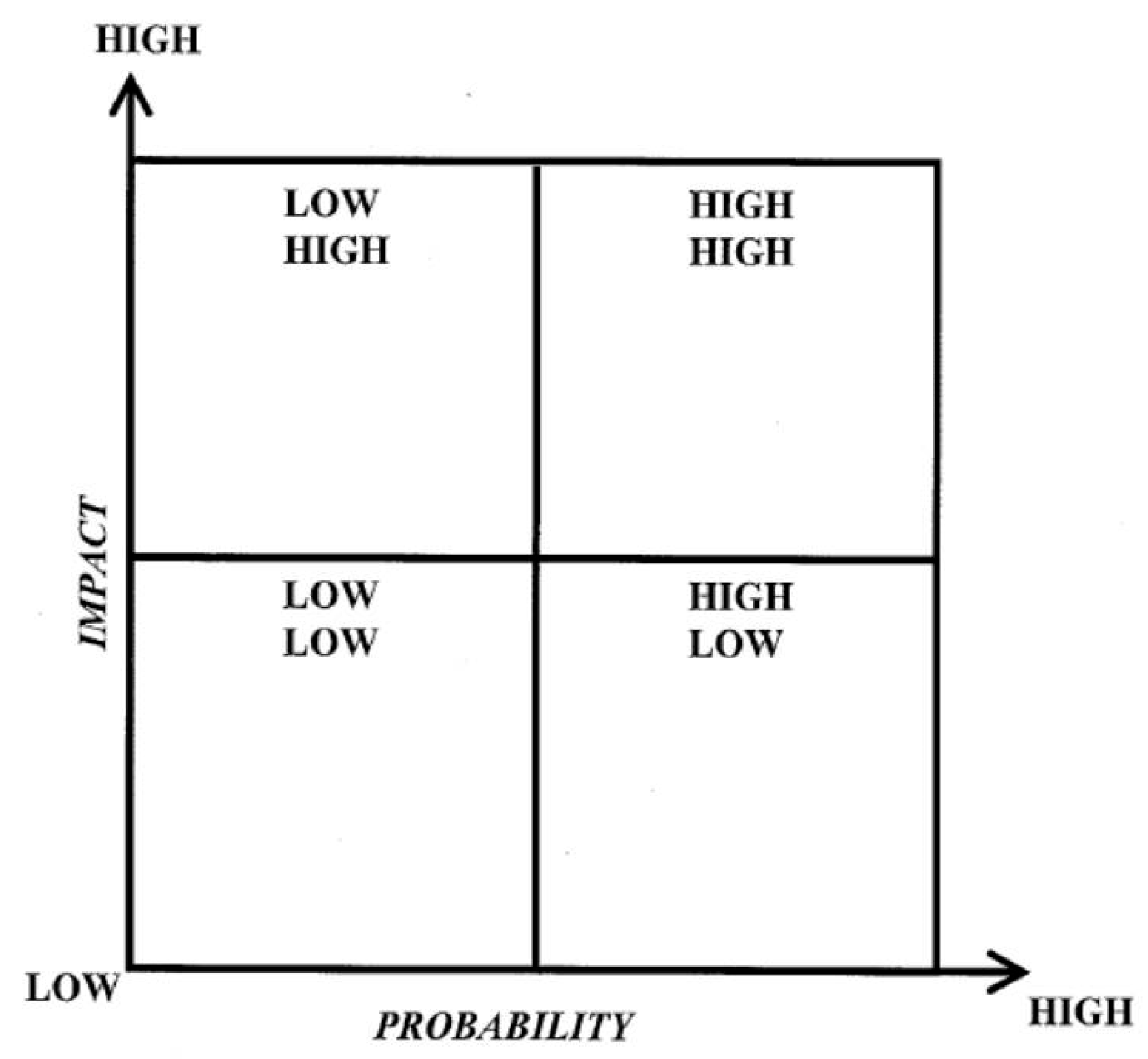

Moreover, CBPRA emphasizes the importance of continuous learning and adaptation. Given the dynamic nature of urban risks, communities must be equipped with the knowledge and resources necessary to monitor hazards, reassess vulnerabilities, and adjust strategies over time. Building local capacities through training programs, workshops, and knowledge-sharing platforms not only strengthens immediate risk responses but also fosters long-term autonomy and resilience. By embedding capacity-building within community structures, CBPRA transforms resilience from a top-down policy objective into a community-driven process, enhancing both the effectiveness and sustainability of urban risk governance. Public perception of risk is crucial to understand in order to design effective, community-based adaptation strategies. The risk quadrant approach, which categorizes risks based on their frequency and impact, enables the identification of risk management priorities from the citizens' perspective [

1].

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a Community-Based Participatory Risk Analysis (CBPRA) approach to investigate multi-hazard vulnerabilities in selected urban kampungs of Surabaya. CBPRA is rooted in the principle that communities are not merely passive recipients of external interventions but are active agents in identifying, assessing, and managing the risks they face. By emphasizing the lived experiences, local knowledge, and adaptive capacities of residents, CBPRA offers a pathway toward building resilience from within the community itself. In contrast to conventional top-down risk assessments, this approach foregrounds participatory engagement as essential to understanding the social construction of vulnerability and enhancing context-specific resilience.

The CBPRA framework employed in this study integrates qualitative methodologies, including participatory workshops, semi-structured interviews, field observations, and the use of the Risk Quadrant Tool to facilitate the prioritization of identified hazards. Through this participatory lens, resilience is conceptualized not simply as the capacity to recover from hazards but as the dynamic ability of communities to anticipate, adapt, and transform in the face of multi-hazard exposures.

The selection of the study areas was informed by preliminary disaster risk assessments conducted by the Center for Disaster Mitigation and Climate Change Studies at ITS (where most of the authors are bas in 2021, which mapped hazard exposure, vulnerabilities, and coping capacities across urban Surabaya. Kampungs exhibiting relatively lower resilience levels, as identified through the Layering Risk Assessment model, were prioritized to capture contexts where community-based strategies would be most critical. Three kampungs were selected: Kenjeran, Kampung Kue, and Kampung Ketandan, each representing a distinct risk profile, namely tidal flooding, infrastructural hazards, and social insecurity, thereby providing a comparative basis for understanding multi-dimensional vulnerabilities.

Primary data collection commenced with participatory workshops conducted within each kampung. These workshops engaged a diverse range of community members, including women, youth, elders, and local leaders, ensuring an inclusive representation of perspectives. Participants collaboratively identified hazards affecting their communities, discussed their perceived impacts, and engaged in hazard prioritization exercises using the Risk Quadrant Tool. This tool guided participants in ranking hazards along two axes, perceived severity of impact and probability of occurrence, enabling a systematic yet accessible method for community-driven risk assessment (see

Figure 1).

To ensure the data collected was statistically reliable, the minimum number of respondents required in each kampung was determined using Slovin's formula, as outlined in

Table 1.

In parallel, semi-structured interviews were carried out with key informants, including long-term residents, community organizers, and representatives from local government institutions. These interviews explored historical experiences with hazards, existing coping mechanisms, and perceptions of institutional support or gaps. Field observations were conducted concurrently to document physical vulnerabilities observable in the built environment, such as the condition of drainage systems, housing structures, public spaces, and critical infrastructures. To complement primary data, a review of secondary sources was undertaken, encompassing urban planning documents, disaster risk reduction strategies, demographic profiles, and prior vulnerability assessments. This secondary data provided a broader contextual background and enabled triangulation of findings from community-based activities.

Data analysis proceeded through thematic coding, identifying recurring patterns related to risk perception, vulnerability-drivers, coping strategies, and collective action. Workshop outputs, interview transcripts, and field notes were systematically analyzed to capture both commonalities and divergences across the three kampungs. In addition, hazard prioritization outputs from the Risk Quadrant exercises were synthesized into localized risk maps, providing a spatial visualization of key vulnerabilities. Comparative analysis across the kampungs allowed for the identification of cross-cutting themes as well as kampung-specific dynamics in vulnerability and resilience-building processes.

3. Key Findings: Multi-hazard Vulnerability Overview

3.1. Risk Prioritization and Distribution Across Kampungs

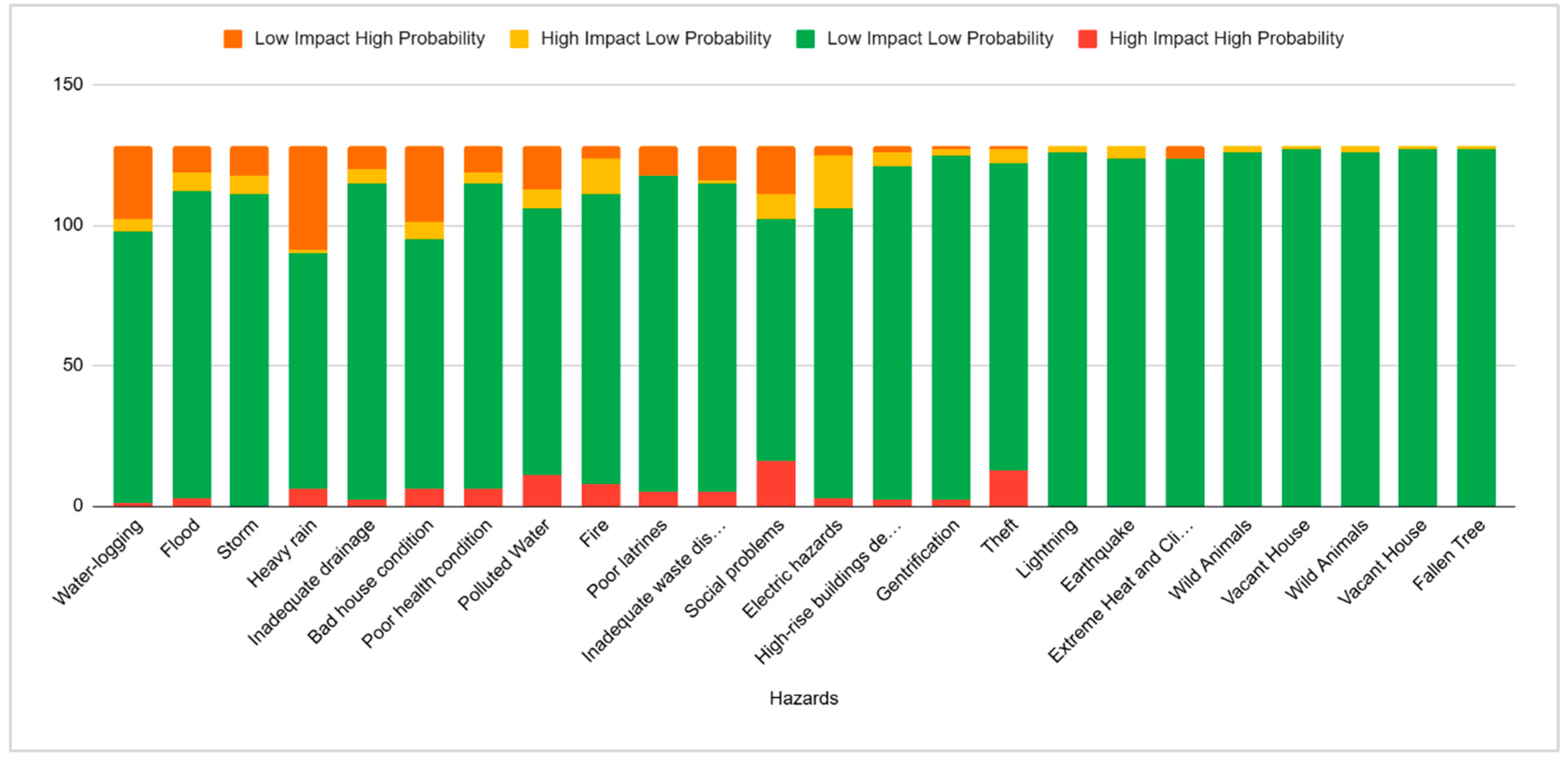

The participatory risk quadrant mapping exercises revealed distinct patterns of hazard prioritization across the three studied kampungs, highlighting how localized environmental conditions, infrastructural capacities, and socio-economic dynamics shape residents' perceptions of risk severity and likelihood. While certain hazards, such as flooding and waterlogging, appeared across all sites, the dominant concerns varied significantly, reflecting the spatial and social diversity of vulnerability landscapes within Surabaya.

In Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran, environmental hazards emerged as the most pressing threats. Participants consistently rated tidal flooding, waterlogging, and heavy rainfall as high-impact, high-probability risks. The kampung’s geographical position near the coastline, combined with the deterioration of natural coastal defenses and inadequate drainage systems, has made it particularly susceptible to recurrent inundation. Workshop narratives emphasized not only the direct damage from flooding but also secondary effects, such as restricted mobility, health risks from stagnant water, and disruption to local economic activities.

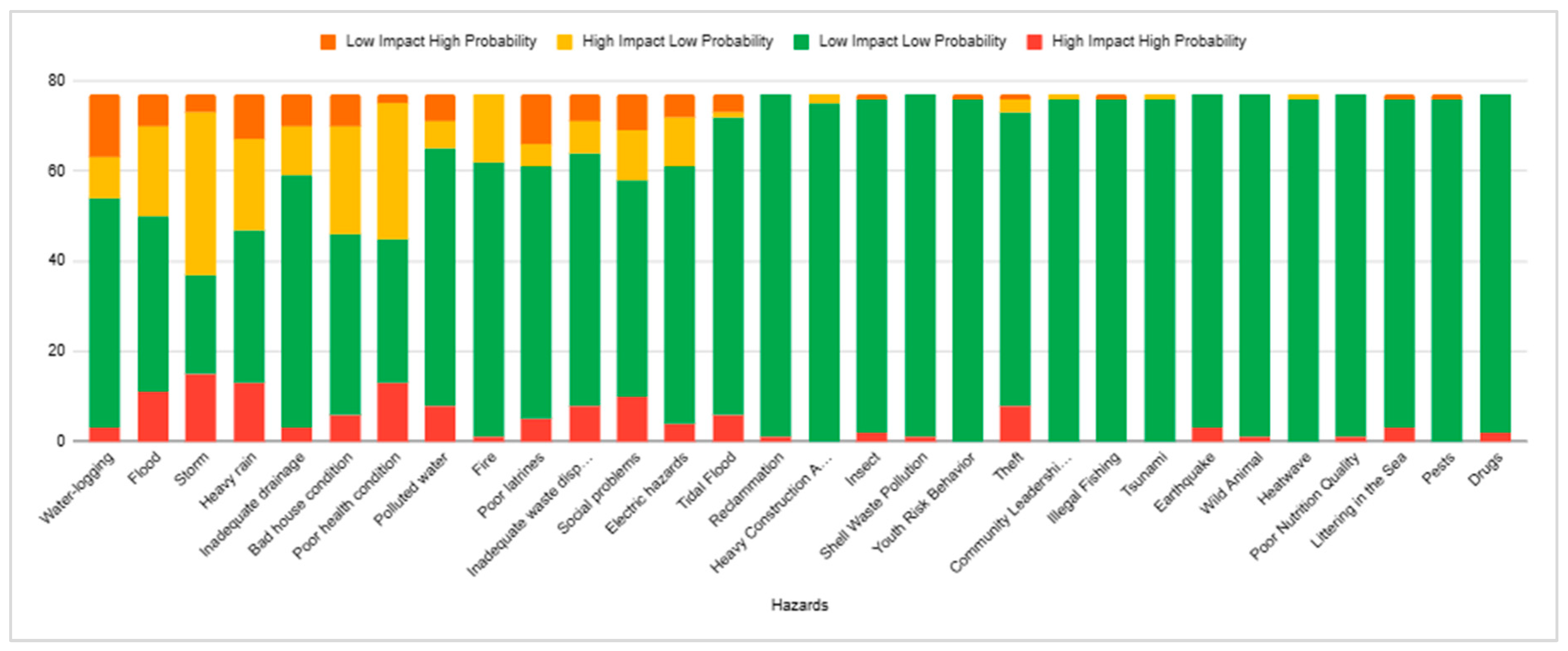

In Kampung Kue Rungkut, infrastructural vulnerabilities dominated the risk landscape. Electrical hazards were the highest prioritized risk, with participants citing frequent short circuits, poorly maintained wiring, and the danger of electrocution during rainy seasons. Additionally, inadequate drainage and deteriorating house conditions were highlighted as significant contributors to everyday risk. Unlike Kenjeran, where natural factors were the primary source of risk, vulnerabilities in Kampung Kue largely stemmed from infrastructural neglect and informal urban development patterns.

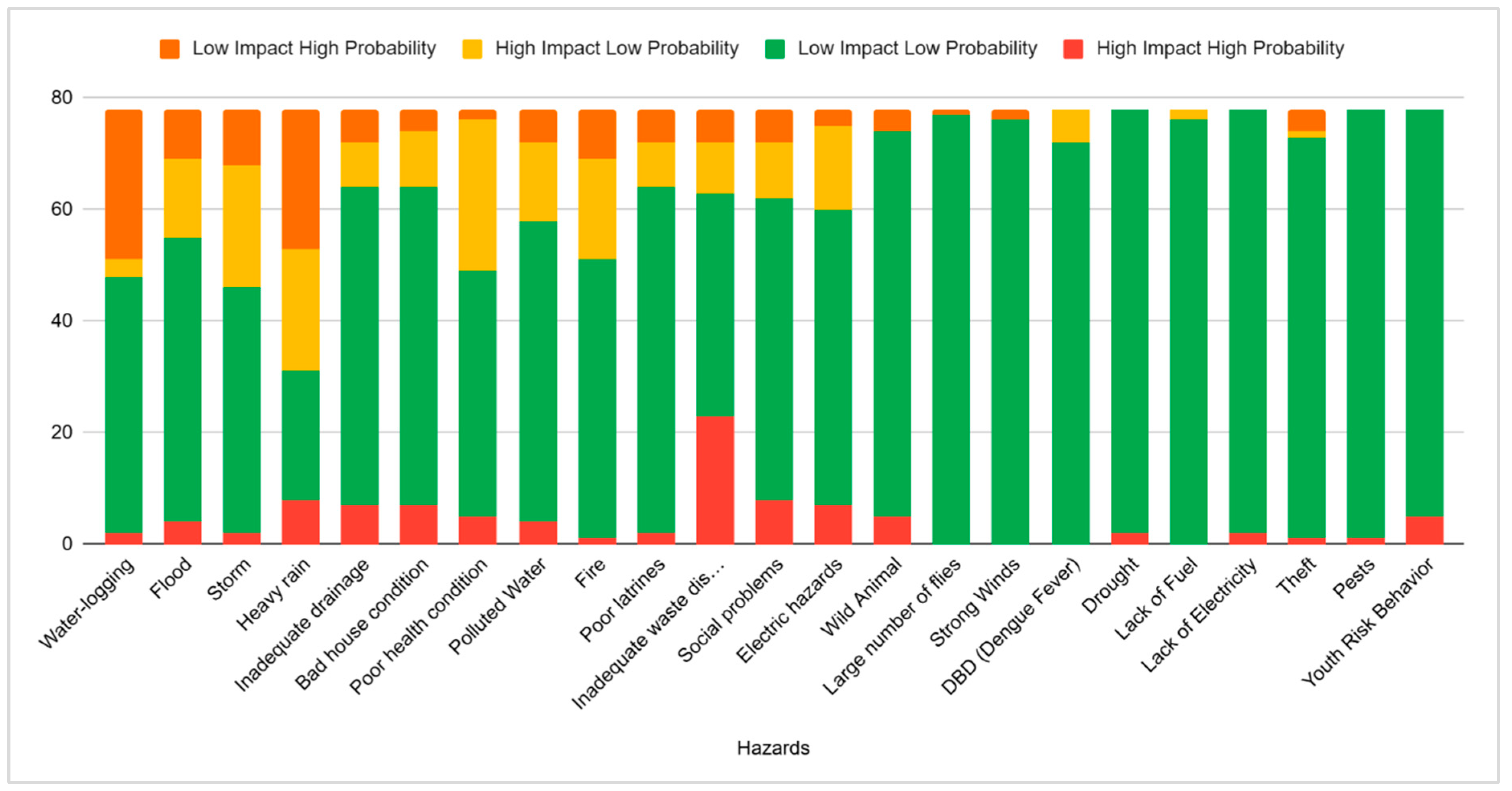

Meanwhile, Kampung Ketandan Kebangsren exhibited a different risk profile, with social hazards surpassing environmental and infrastructural concerns. Issues such as theft, social insecurity, and the pressures of gentrification were repeatedly identified as major threats. Residents linked these risks to the ongoing socio-economic transformation of the area, where rising property values and demographic shifts have strained traditional community networks and created new vulnerabilities related to displacement, social fragmentation, and crime.

The comparative stacked column charts (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) visually illustrate these differentiated patterns, with environmental, infrastructural, and social hazards exhibiting varying degrees of perceived impact and probability across the three kampungs. While all areas remain exposed to multiple hazards simultaneously, the results underscore that vulnerability profiles are not uniform but are deeply shaped by localized socio-spatial conditions.

This differentiated prioritization provides a critical foundation for understanding the complex layering of vulnerabilities in urban kampungs, and it signals the necessity for risk governance approaches that are both place-specific and hazard-integrated. The following sections further examine how vulnerability is differentiated within community groups and how these diverse experiences shape the broader risk landscapes.

3.2. Differentiated Vulnerability Across Community Groups

Beyond the differences observed between kampungs, the study also revealed important variations in vulnerability perceptions across different community groups within each kampung. Risk is not experienced uniformly even within the same spatial context; instead, it is filtered through the lenses of age, gender, social role, and livelihood position, producing stratified patterns of perceived exposure and capacity to adapt. Among women and elderly participants, infrastructural and environmental hazards were consistently ranked as the most significant threats. Issues such as poor drainage, deteriorating house conditions, and heightened risks of disease transmission from stagnant water were particularly emphasized. These groups often framed vulnerability through the lens of daily life disruptions and personal safety concerns, highlighting how limited physical mobility and caregiving responsibilities intensified their exposure to both environmental and infrastructural risks. In contrast, youth participants expressed greater concern over social hazards, particularly theft, gang activities, and the erosion of communal safety. In discussions, youth groups pointed to the changing social fabric of the kampungs, where economic pressures and demographic shifts have weakened traditional community ties, leading to heightened perceptions of insecurity and distrust in public spaces. Community leaders, both formal (RT/RW heads i.e. community leaders) and informal (religious and market leaders), tended to frame risk in more systemic terms. They identified gaps in governance structures, lack of institutional support for infrastructure maintenance, and limited community preparedness for disaster response as key contributors to ongoing vulnerabilities. Rather than isolating individual hazards, leaders often pointed to the interconnectedness of risks, emphasizing how environmental degradation, infrastructural failures, and social disintegration compounded each other to produce complex and persistent vulnerabilities.

These differentiated perceptions across social groups reveal that vulnerability is both socially constructed and relational. What constitutes a major risk for one group may be considered secondary by another, depending on daily practices, social status, and access to coping resources. Understanding these layered vulnerabilities is crucial for designing inclusive risk reduction strategies that respond not only to the physical characteristics of hazards but also to the lived realities of diverse community members. The next section synthesizes these findings into a broader typology of hazards and vulnerabilities, illustrating how multiple dimensions of risk converge within urban kampungs and outlining the emerging multi-hazard landscapes they face.

3.3. Typologies of Hazards and Their Perceived Risks

Synthesizing the findings from the kampung-level hazard prioritization and the differentiated perceptions among community groups, three broad typologies of hazards and vulnerabilities emerge across the studied sites: environmental hazards, infrastructural hazards, and social vulnerabilities. These categories are not mutually exclusive; instead, they often overlap and interact, producing complex multi-hazard landscapes that challenge simplistic or sectoral approaches to risk management.

Environmental hazards such as tidal flooding, waterlogging, heavy rainfall, and storm impacts were most pronounced in coastal and low-lying areas like Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran. These hazards are primarily linked to natural processes, but their severity is compounded by anthropogenic factors such as inadequate drainage systems and coastal reclamation activities. Environmental vulnerabilities tend to be manifested as direct physical risks to property, health, and mobility, especially during seasonal peak events.

Infrastructural hazards were a dominant concern in Kampung Kue Rungkut, where risks related to electrical hazards, drainage failures, and deteriorating housing stock were prioritized. These hazards reflect the cumulative effects of informal urbanization, aging infrastructure, and insufficient maintenance regimes. Unlike environmental hazards, infrastructural vulnerabilities are embedded within everyday routines, making them persistent, normalized, and often less visible to external observers.

Social vulnerabilities, including theft, insecurity, and the pressures of gentrification, were most acutely observed in Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren. As urban redevelopment processes intensify, traditional social networks are eroded, and long-term residents face increasing displacement pressures. These social risks represent a shift in the urban kampung risk landscape, where socio-economic transformations create new forms of exposure and marginalization that are not captured by traditional disaster risk assessments.

Overall, the convergence of these hazard typologies underscores the evolving complexity of urban kampung vulnerability. No single kampung faces risks from only one source; rather, residents navigate overlapping and intersecting hazards that are shaped by their physical environment, infrastructural context, and socio-economic conditions. Recognizing this multi-dimensionality is crucial for moving beyond hazard-specific interventions toward integrated and adaptive risk reduction strategies that align with the realities of kampung life.

4. Results of the Research Investigations

The research investigations and field data collection was carried out through the distribution of questionnaires and structured interviews with initial respondents across the three kampung locations. The resulting dataset was used to conduct a preliminary mapping of the types of hazards faced by the communities, classified into four categories within the Risk Quadrant diagram (see

Figure 1): high impact with high probability, high impact with low probability, low impact with high probability, and low impact with low probability. The following section presents an overview, analysis, and explanation of the results of the investigations in the three kampungs selected as case studies in this research.

4.1. Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran

Fishermen’s settlements in Indonesia’s coastal areas face various environmental risks that affect social, economic, and public health aspects. High building density, poor infrastructure quality, and exposure to climate change contribute to increased vulnerability to coastal hazards and environmental degradation [

15]. Residents who work as fishermen are usually highly dependent on the natural environment in which they live [

16]. To identify and understand the potential hazards faced by the coastal community in Kenjeran Fishermen’s Village (see

Figure 3), a field survey was conducted and analyzed using the Risk Quadrant approach. This approach mapped the likelihood and impact of each potential risk present in the area. The survey results showing the potential hazards in Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran based on the Risk Quadrant can be seen in

Table 2.

4.2. Kampung Kue Rungkut

Kampung Kue Rungkut is a residential area in Surabaya that has unique characteristics and its own set of challenges in facing various hazards and environmental issues. Like many other densely populated settlements, Kampung Kue Rungkut has a high residential density, with diverse building structures and infrastructure conditions that are not yet fully adequate. In Kampung Kue Rungkut, the main challenges include flooding, heavy rainfall, and fire risks caused by intensive use of household electrical appliances. Other domestic risks, such as poor drainage (see

Figure 5) and electrical hazards, also consistently appear in residents’ perceptions. A study conducted with 78 respondents in Kampung Kue presents the findings shown in the table 3.

Table 3.

Hazard risk mapping datasets of Kampung Kue Rungkut.

Table 3.

Hazard risk mapping datasets of Kampung Kue Rungkut.

| Hazards |

High Impact High Probability |

Low Impact Low Probability |

High Impact Low Probability |

Low Impact High Probability |

| Waterlogging |

2 |

46 |

3 |

27 |

| Flood |

4 |

51 |

14 |

9 |

| Storm |

2 |

44 |

22 |

10 |

| Heavy rain |

8 |

23 |

22 |

25 |

| Inadequate drainage |

7 |

57 |

8 |

6 |

| Bad house condition |

7 |

57 |

10 |

4 |

| Poor health condition |

5 |

44 |

27 |

2 |

| Polluted Water |

4 |

54 |

14 |

6 |

| Fire |

1 |

50 |

18 |

9 |

| Poor latrines |

2 |

62 |

8 |

6 |

| Inadequate waste disposal |

23 |

40 |

9 |

6 |

| Social problems |

8 |

54 |

10 |

6 |

| Electric hazards |

7 |

53 |

15 |

3 |

| Hazards based on community perceptions |

| Wild Animals |

5 |

69 |

0 |

4 |

| Large number of flies |

0 |

77 |

0 |

1 |

| Strong Winds |

0 |

76 |

0 |

2 |

| DBD (Dengue Fever) |

0 |

72 |

6 |

0 |

| Drought |

2 |

76 |

0 |

0 |

| Lack of Fuel |

0 |

76 |

2 |

0 |

| Lack of Electricity |

2 |

76 |

0 |

0 |

| Theft |

1 |

72 |

1 |

4 |

| Pests |

1 |

77 |

0 |

0 |

| Youth Risk Behavior |

5 |

73 |

0 |

0 |

A broader survey involving 78 respondents provides further insight into this complexity. In the HIHP category, the most prominent hazard identified was inadequate waste disposal, cited by 23 respondents as both high impact and highly probable. Other significant hazards included heavy rain, bad house conditions, inadequate drainage (see

Figure 5), and electric hazards, each cited by 7 to 8 respondents. These findings reinforce that residents are acutely aware of recurring threats that significantly affect their daily lives and overall well-being.

In the High Impact Low Probability (HILP) category, hazards with potentially severe consequences were included despite their infrequent occurrence. Fire emerged as the top concern, identified by 18 respondents. Flooding was also a major concern with 14 respondents, followed by storm hazards with 22 respondents. Health risks such as dengue fever (DBD) and polluted water were also included in this category, cited by 6 to 14 respondents. Additionally, social problems and electric hazards were mentioned with slightly lower but still notable numbers. These findings indicate that while such hazards may occur less frequently, their impact could be highly detrimental if they do happen.

In the Low Impact High Probability (LIHP) category, residents identified hazards that they frequently experience but perceive to have a relatively minor impact. Waterlogging was the most dominant issue in this category, with 27 respondents reporting frequent experiences, followed by heavy rain (25 respondents) and flood (9 respondents). Inadequate drainage and poor sanitation, such as improper toilets and poor waste management, were also common issues, each reported by 4 to 6 respondents. Bad house conditions and theft were among the frequently occurring hazards as well, mentioned by 1 to 4 respondents. The high frequency of these hazards indicates the need for continuous intervention to improve infrastructure and enhance the community's quality of life.

The Low Impact Low Probability (LILP) category includes hazards that are rarely encountered and perceived to have minimal impact by the community. Wild animals, large number of flies, strong winds, drought, and shortages of electricity or fuel fall into this group. Wild animals were not seen as a threat by 69 respondents; flies and strong winds were dismissed by 77 and 76 respondents respectively. Drought and electricity shortages were also considered low-impact and rare by 76 respondents. Although these hazards were listed, they were not viewed as major concerns by residents, likely due to their low frequency or negligible impact. Additionally, emerging risks such as youth risk behavior were also placed in this category, with 5 respondents mentioning it.

Overall, the situation in Kampung Kue illustrates a complex vulnerability landscape, where physical and social environmental risks intersect. Poor waste management, fire hazards, and lack of proper waste disposal are the primary risks that require immediate attention. Meanwhile, frequent events such as waterlogging, heavy rain, and flooding, though seen as of lower impact, continue to disrupt residents’ activities and health, signaling the need for sustained focus, especially in improving the drainage system. Social issues, including conflict, youth risk behavior, and insecurity, should not be overlooked, as they may further exacerbate the vulnerability of this settlement.

4.3. Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren

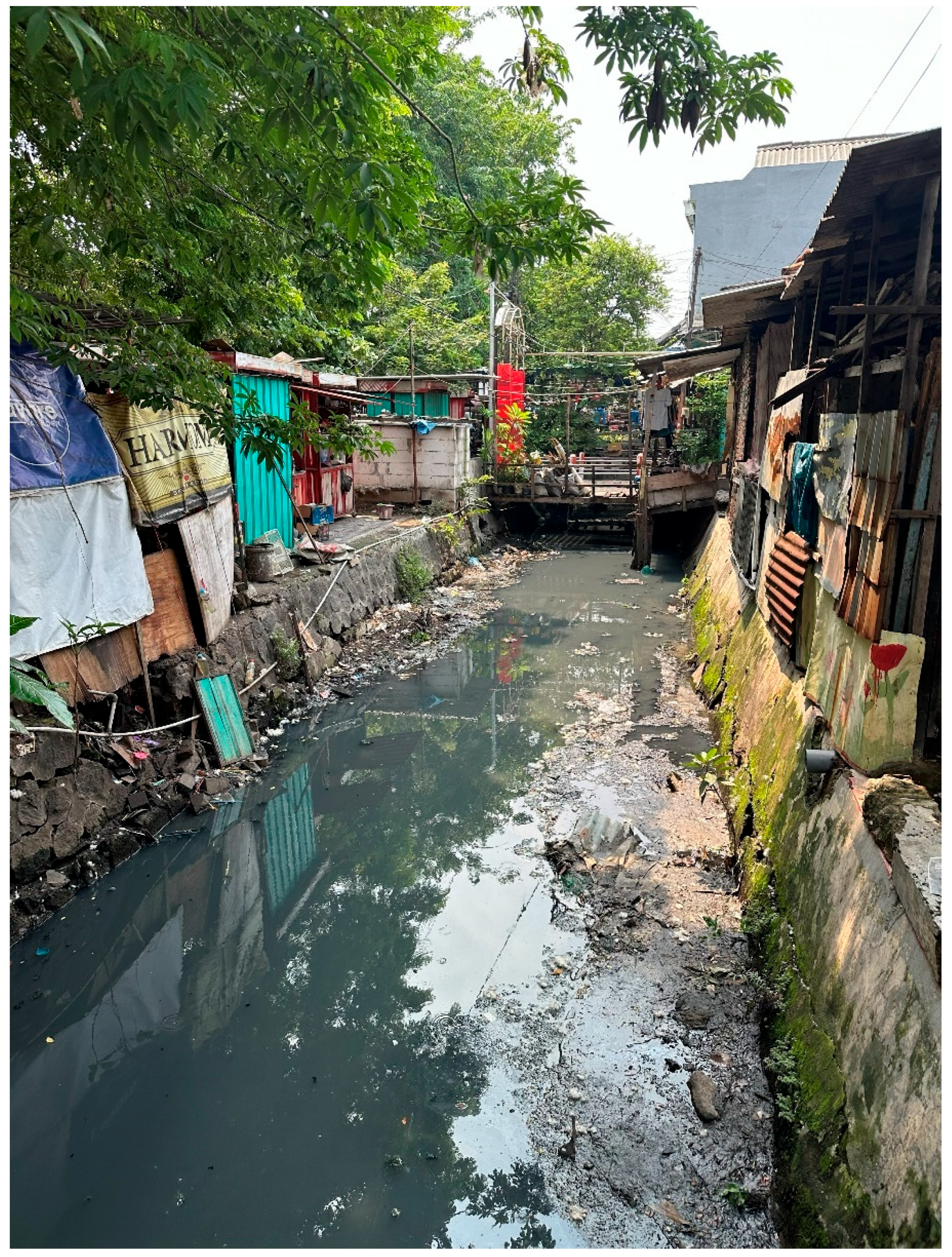

Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren is a densely populated residential areas located in the heart of Surabaya. Its strategic location in the city center makes it highly vulnerable to rapid urbanization and gentrification (see

Figure 7), including environmental, social, and economic pressures. Most of the houses in this kampung were self-built by residents, often without adherence to disaster-resilient construction standards. The research findings from Kampung Ketandan Kebangsren are presented in

Table 4.

Figure 6.

Stacked Column Chart (Risk Quadrant – Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren).

Figure 6.

Stacked Column Chart (Risk Quadrant – Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren).

Figure 7.

A view from Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsten indicating its central city location (photo credit: Author Iftekhar Ahmed).

Figure 7.

A view from Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsten indicating its central city location (photo credit: Author Iftekhar Ahmed).

Based on a survey involving 127 respondents from the local community, various types of hazards were identified and classified according to their level of impact and probability of occurrence. The classification results are divided into four main categories: High Impact High Probability (HIHP), High Impact Low Probability (HILP), Low Impact High Probability (LIHP), and Low Impact Low Probability (LILP).

In the High Impact High Probability (HIHP) category, several major hazards emerged as the most significant and recurring threats in the residents’ daily lives. Social problems such as interpersonal conflicts, insecurity, and community disturbances, ranked the highest with 16 respondents identifying them as high-impact and highly probable. Theft was also a serious concern, noted by 13 respondents. Bad house condition and poor health condition were each considered highly dangerous and frequently experienced, with 6 respondents selecting each. Fire was also significant in this category, with 8 respondents, and electric hazards were identified by 3 respondents. These findings reflect that both physical and social threats are acknowledged by residents and must be addressed together to reduce overall community risk.

The High Impact Low Probability (HILP) category refers to hazards that are infrequent but have the potential for severe consequences. Within this category, fire again received a high level of concern with 13 respondents, followed by electric hazards with 19 respondents. Natural hazards such as flood and storm were each cited by 7 respondents, indicating concerns over environmental risks despite their less frequent occurrence. Polluted water and social problems were also included in this category, mentioned by 7 and 9 respondents respectively.

In the Low Impact High Probability (LIHP) category, the hazards identified are those that occur frequently but are perceived to have relatively low impact. Heavy rain was the most frequently experienced, with 37 respondents stating it as a routine event. Waterlogging was also common, mentioned by 26 respondents, and bad house condition was reported by 27 respondents. Inadequate drainage and poor latrines were each identified by 8 and 10 respondents respectively. Inadequate waste disposal remains a consistent issue, with 12 respondents selecting it. Although the immediate impacts of these hazards are relatively minor, their high frequency leads to chronic issues that degrade living conditions and increase exposure to environment-related diseases such as gastro-intestinal infections and other health problems.

The Low Impact Low Probability (LILP) category includes hazards perceived as both low in impact and low in likelihood. These include wild animals, lightning, earthquake, extreme heat and climate, vacant houses, and fallen trees. Most respondents considered these hazards to have minimal relevance to their daily lives, as reflected in the very low response rates in this category. This indicates that these hazards are perceived as less significant, likely due to their rare occurrence, low intensity, or a general lack of direct experience with them.

Overall, the findings suggest that Kampung Kota Ketandan-Kebangsren faces a complex and interconnected set of multi-hazard vulnerabilities. Physical risks such as fire, poor sanitation (e.g., poor latrines, inadequate drainage, and inadequate waste disposal), and bad house condition are closely linked with social and economic risks such as social problems, theft, and gentrification. The imbalance between hazard frequency and impact poses a challenge in disaster risk reduction planning. Frequent but low-impact hazards like waterlogging and poor sanitation require sustained, long-term interventions to improve community well-being, while high-impact but less frequent hazards like fire and electric hazards demand serious preparedness and technical measures to prevent significant losses.

5. Discussion and the Way Forward

The following discussion addresses the specific issues that occur most frequently and have the greatest impact on the community in each kampung, along with their mitigation strategies.

5.1. Tidal and Localized Floods, and Social Problems in Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran

As is well known, flooding in coastal areas can be caused by heavy rain or tidal floods. Tidal flooding is a type of disaster that is increasingly common in coastal regions. Coastal settlements are the most vulnerable areas to the impacts of tidal floods, with communities affected economically, socially, and health-wise. Tidal flooding is caused by seawater rising and inundating low-lying land areas, especially coastal settlements. This phenomenon results from a combination of sea level rise, land subsidence, and global climate change [

17]. In Indonesia, coastal cities such as Semarang, North Jakarta, and Demak are clear examples of areas severely affected by tidal floods [

18]. In recent years, tidal flooding has begun to occur in the Kampung Nelayan Kenjeran area and its surroundings, somewhat disrupting the daily activities of the community. Interviews with residents confirmed the occurrence of flooding caused by rising sea levels.

From the research conducted, flooding, whether caused by tidal flooding or localized flooding due to heavy rain, has resulted in a decline in the community’s quality of life. This condition impacts the lives and activities of residents, including social problems arising from decreased economic activity. The flooding hampers business activities, reduces productivity due to damaged homes, disrupts daily routines, and causes health issues such as skin diseases and diarrhea due to unhygienic conditions created by persistent waterlogging.

To address these issues, several mitigation strategies can be implemented through structural and non-structural approaches. The Kenjeran community and Surabaya City Government have already undertaken some adaptations to the tidal flooding problem. Structurally, tidal flooding can be managed by building sea dikes, polders, and adequate drainage systems. However, in Kenjeran, these measures have not been fully implemented. The dike constructed alongside the Surabaya Bridge, built around 2015, has somewhat helped mitigate tidal flooding in some directly affected areas. However, the majority of the area remains vulnerable. Additionally, the bridge itself creates access difficulties for local fishermen, affecting their boat movements to and from the sea, a problem not covered in this paper.

Non-structurally, efforts to reduce impact focus on educating the community. For example, constructing houses that meet coastal area standards, planting mangroves, maintaining cleanliness to prevent litter, and ensuring drainage channels remain free of trash. Despite these efforts, house construction that meets standards is sometimes hindered by residents’ financial constraints and builders’ knowledge. Moreover, mangrove planting is currently not feasible in Kenjeran due to geographic conditions, and further study is needed regarding this concept.

From the above explanation, it is clear that this fishing village faces a very high potential for multi-hazard pressure. This multi-hazard pressure results from a combination of disasters that simultaneously influence the occurrence of other hazards. Flooding caused by heavy rain or tidal flooding disrupts community activities. This situation is worsened by poor infrastructure conditions, such as inadequate drainage, poor housing, and mismanaged waste. Poor waste management clogs drainage channels, and many residents still dispose of waste improperly, which exacerbates flooding during rain.

In addition, residents also complain about security disturbances caused by safety threats (gangsters), shell waste pollution, youth risk behaviors, theft, and community leadership gaps. All of these issues stem from social shifts within the community. According to in-depth interviews, this phenomenon began after the construction of the Surabaya Bridge, which caused social changes. Previously, the area was more homogeneous, mainly inhabited by the Madurese ethnic group, whose livelihoods centered around fishing and marine-related activities. Currently, the area is increasingly influenced by other activities, such as marine tourism, with the bridge serving as an iconic tourism landmark. Additionally, to boost local incomes, the Surabaya City Government developed the Bulak Fish Center, attracting many tourists. Around the Fish Center, parks and the Suro-Boyo monument (an icon of Surabaya) have also been built.

Economic growth has naturally attracted outsiders, who have started settling near the fishing settlement. The mingling of various cultures and customs has weakened social bonds in the community. Reduced social cohesion has consequently lowered residents’ care and concern for their neighbors, environment, and each other.

Deviant youth behavior and the influx of external cultures have altered the social fabric. Youths growing up without adequate guidance, coupled with limited roles from family, schools, and community leaders, have formed destructive informal groups such as gangs. If left unchecked, these groups could disrupt public order. Their desire for identity and recognition makes them counterproductive to community harmony. In the long term, the degradation of social cohesion might lead to community fragmentation, inter-neighborhood conflicts, and weakened resilience to external challenges.

Therefore, village officials, community leaders, and religious figures must strengthen social cohesion to effectively counter threats from both internal and external sources.

5.2. Inadequate Waste Disposal in Kampung Kue Rungkut

Kampung Kue Rungkut is a densely populated residential area in Surabaya known not only as a place to live but also as a center for small-scale economic activity, specifically the production of traditional cakes. This home-based industry serves as the main source of income for most residents and is an important part of the local identity and culture. However, the intensive cake production activities also bring certain challenges, particularly related to inadequate waste management. This issue has the potential to cause serious impacts on the environment, public health, and the sustainability of local businesses.

Based on a survey involving 78 respondents, inadequate waste disposal emerged as one of the main issues with high impact and probability. A total of 23 respondents categorized this problem under High Impact High Probability (HIHP), making it the most frequently identified serious and recurring threat. Additionally, 9 respondents placed it in the High Impact Low Probability (HILP) category, 6 respondents in Low Impact High Probability (LIHP), and the remaining 40 respondents in Low Impact Low Probability (LILP). This data shows that although residents’ perceptions vary, the majority recognize the significant potential danger of a suboptimal waste management system.

The main underlying problem causing inadequate waste management in Kampung Kue Rungkut is the lack of infrastructure, such as waste segregation systems and organized disposal routes. Waste from cake production, including leftover food materials, plastic packaging, and domestic wastewater, is often dumped directly without treatment. This leads to pollution and creates an unhealthy environment for residents. In the long term, this can affect public health and the local economy’s sustainability, as Kampung Kue’s product reputation may be impacted by the environmental image.

To address this problem, coordinated intervention is needed involving the city government, environmental agencies, and local communities. Concrete steps such as providing integrated waste management facilities are essential. In addition, training home industry operators on more environmentally friendly production methods can help reduce waste volume and raise collective awareness about the importance of environmental sanitation. A community-based approach involving local leaders and cake producers can facilitate socialization and the implementation of solutions.

With active involvement from all parties, Kampung Kue can achieve a cleaner, healthier environment that supports sustainable economic growth. This effort will not only solve waste problems but also strengthen the overall socio-economic resilience of the community.

5.3. Security Concerns and the Threat of Social Hazards in Kampung Ketandan Kebangsten

Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren is a densely populated residential area that faces not only environmental and physical risks but also various social challenges that significantly impact the safety and comfort of its residents. Based on data obtained from a survey, social problems rank quite high in terms of impact and probability, with 16 respondents rating social problems as a risk with High Impact High Probability (HIHP). Additionally, 86 respondents categorized social problems as Low Impact Low Probability (LILP), and 9 respondents assessed the probability as high despite the impact being low, indicating that social issues are frequent and complex problems in this community.

The range of social problems faced by Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsren includes social conflicts and criminal acts such as theft. Theft also received significant attention in the survey data, with 5 respondents categorizing it as High Impact Low Probability (HILP) and 109 respondents placing it in the Low Impact Low Probability (LILP) category. This indicates that although theft does not occur frequently, its impact on victims is severe, causing both material and psychological harm. This social insecurity poses a major challenge affecting residents’ quality of life and community stability in Kampung Kota Ketandan-Kebangsren.

Moreover, social dynamics are influenced by urban changes such as gentrification and the development of high-rise buildings entering the area. While these changes are considered to have a low probability of occurring in the near term, their potential impact is very large and could drastically alter the community’s social structure. The data also shows that social risks are closely related to poor public health conditions and sanitation, which indirectly exacerbate social tensions. When basic needs such as health and sanitation are inadequately met, frustration and dissatisfaction may increase, contributing to potentially significant social problems.

Addressing security issues and social hazards in Kampung Kota Ketandan requires a comprehensive approach involving multiple stakeholders, including the government, security forces, and the local community itself. A community-based approach is crucial to building trust and facilitating dialogue among residents to resolve conflicts peacefully. Social welfare programs, including improvements in health and sanitation infrastructure, should also be integrated to reduce social problems. Strengthening local security institutions and increasing patrols and surveillance within the residential area can help reduce crime rates, particularly theft, which remains a concern for residents.

Overall, addressing social hazards in Kampung Kota Ketandan-Kebangsren must be an integral part of broader disaster risk reduction strategies, as social factors greatly influence community preparedness and response to various threats.

5.4. Unveiling Risk Landscapes: A Comparative Analysis of the Three Kampungs

Kampungs, or ‘urban villages’, in Indonesia face diverse and complex risks, often compounded by a lack of planning, weak infrastructure, and socio-economic pressures. Understanding the unique ‘risk landscape’ of each settlement is essential for formulating inclusive and resilient urban development strategies.

From the discussion above, it is clear that the three kampungs studied have different hazard vulnerabilities according to their landscape conditions. These three settlements represent different natural settings and landscape challenges. The first kampung is a fishing village located on the coast, with a strong dependence on the coastal landscape. The livelihoods of the residents are related to the sea—whether as fisherfolk or through home-based businesses for processing marine products—making the sea their main source of livelihood. The issues faced by this coastal community are closely tied to its landscape and livelihoods. Periodic tidal flooding, localized floods, and storms disrupt daily activities, affecting both domestic life and income-generating work.

The second kampung is a home-based production village, primarily known for producing traditional cakes. Most households in this village produce cakes that are distributed daily throughout Surabaya. The processing of raw materials into ready-to-eat products also generates a large amount of waste, both organic and non-organic. The significant volume of waste and inadequate waste management make waste a critical problem in this cake village. Additionally, the relatively high electricity use to support their businesses sometimes leads to electrical short circuits, increasing the risk of fires.

The third village is located in a densely populated urban area. The influx of newcomers and the conversion of houses into boarding houses or rental homes have weakened social bonds among the residents. Although many original residents still live there, this situation has led to a decline in community care for the environment. The occurrence of theft and other social problems indicates that social cohesion is deteriorating. These are the main issues faced by this village.

Based on the discussion above in sections 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3, a Comparative Risk Landscape is presented in

Table 5.

Unveiling risk landscapes can be understood as a manifestation of housing inequality in urban areas that depends on the position or location of the landscape. The different landscape settings of the three villages cause them to face varying disaster risks. However, the root problems tend to be similar, revolving around weak infrastructure, unequal access to public services, low socio-economic conditions of the community, and the lack of proper planning during development and expansion. This condition aligns with findings by UN-Habitat [

19], which states that non-inclusive planning leads to high disaster risks in areas that do not receive equitable development access.

One effort to reduce the impact of disaster risks characteristic of these landscapes can be done through technical planning that relies on community participation to engage in disaster risk reduction and to formulate people-centered policies. Communities can be encouraged to secure and prepare themselves for potential disasters in their areas due to the factors revealed by the unveiling of risk landscapes.

Flood and tidal flooding risks can be managed by maintaining clean and well-functioning drainage systems to prevent blockages caused by accumulated waste, building proper and adequate infrastructure so that residents can continue their activities during floods or tidal flooding, installing water gates, and creating barriers to reduce water intrusion into homes during floods or tidal flooding.

For Kampung Kue Rungkut, where waste management and fire caused by electrical short circuits are the main problems, residents can be provided with knowledge and training on the importance of cleanliness and proper waste management, the health hazards involved, and awareness of fire risks due to electrical faults. They should also be educated on safe electrical wiring practices and the use of safe electrical equipment and components designed to handle high electricity loads.

Meanwhile, for Kampung Kota Ketandan Kebangsten, efforts can be made to restore community cohesion and concern for the surrounding environment through informal community organizations such as regular religious study groups (pengajian), women’s groups, youth organizations (karang taruna), mutual work activities (gotong royong), sports, and other social community events.

5. Conclusion

Kampungs in major cities of Indonesia, such as Surabaya, face various multidimensional and contextual risks. From the three kampung case studies, different hazard risks were identified: The coastal kampung faces ecological pressures (storms, floods, and tidal flooding), the production kampung faces environmental risks (waste management and fire hazards), while the dense urban kampung faces social risks (theft and criminal acts).

These differences confirm that resilience strategies cannot be generalized but must consider the specific local context. However, the root causes are very similar, so community-based approaches, improving the quality and quantity of infrastructure as a foundation, and strengthening local institutions are key to reducing risks in densely populated urban village settlements. In conclusion, a cross-sectoral and community-based approach is essential to create resilient and safe kampungs for their residents.

Author Contributions

Authors 1 and 2 conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and finalized writing of the manuscript. Author 3 conducted data collection and analysis. Authors 4 and 5 contributed to the interpretation of results and undertook critical revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Dana ITS Inbound Research Mobility, ITS, Surabaya, Indonesia. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, or in writing the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval for this study was provided by the Directorate of Research and Community Service, ITS, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Informed Consent Statement

Inform consent was received from all the research participants.

Data Availability Statement

Research data of this study can be made available on request on conditions of confidentiality, attribution of intellectual property and permission for reproduction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed, I. ; Building resilience of urban slums in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Proced. Soc. & Behav. Sciens. 2016, 218, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L. ; Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog. Hum. Geog. 1996, 20, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. ; A ladder of citizen participation. Jrnl. Amer. Inst. Plns. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauran, T. ; Beyond the informal settlement: The land tenure situation of urban kampungs in Surabaya, Indonesia. Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 916, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat; The challenge of slums: Global report on human settlements. Nairobi, UN-Habitat, 2003.

- Husin, D. , Komala, O.N.; The rhythm analysis of Kampung Gebang Wetan. Intl. Jrnl. Muldis. & Crnt. Edu. Resrch. 2024, 6, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ernawati, R. , Santosa, H.R., Setijanti, P.; Community initiatives in developing sustainable settlements: Case study kampung in Surabaya, Indonesia. Intl. Jrnl. Engg. Resrch & Tech. 2014, 3, 2242–2245. [Google Scholar]

- Erawati, D. , Santosa, H.R., Kisnarini, R., Septanti, D.; Housing improvement based on gender role in urban kampungs of Surabaya. Intl. Jrnl. Engg. & Scien. 2018, 7, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shirleyana, Hawken, S. , Sunindijo, R.Y., Sanderson, D.; The critical role of community networks in building everyday resilience: Insights from the urban villages of Surabaya. Intl. Jrnl. Disatr. Risk Reduct. 2023, 98, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Shu, J., Yuan, Y.; Navigating urban risks for sustainability: A comprehensive evaluation of urban vulnerability based on a pressure–sensitivity–resilience framework. Sust. Cities & Soc. 2024, 117, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaycıoğlu, M. , Kalaycıoğlu, S., Çelik, K., Christie, R., Filippi, M.E.; An analysis of social vulnerability in a multi-hazard urban context for improving disaster risk reduction policies: The case of Sancaktepe, Istanbul. Intl. Jrnl. Disatr. Risk Reduct. 2023, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Julià, P.B. , Ferreira, T.M.; From single- to multi-hazard vulnerability and risk in historic urban areas: A literature review. Natl. Hazds. 2021, 108, 93–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannewitz, M, Garschagen, M. ; The role of social identities for collective adaptation capacities: General considerations and lessons from Jakarta, Indonesia. Intl. Jrnl. Disatr. Risk Reduct. 2024, 100, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Khotimah, K. , Zakaria, Z., Yendra, Y., Tonggiroh, M. Community services and their role in enhancing urban resilience. Adv. Comm. Servs. Resrch. 2025, 3, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiyono, Y. Aerts, J.C.J.H., Tollenaar, D., Ward, P.J.; River flood risk in Jakarta under scenarios of future change. Nat. Hazards. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 757–774. [CrossRef]

- Septanti, D. , Santoso, E.B., Cahyadini, S., Setyawan, W., Utami, A.S.P.R., Amiroh; Criteria for sustaining coastal communities’ livelihoods. Intl. Review Spat. Plng. & Sust. Dev. D: Plng. Assmt. 2023, 11, 278–293. [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo, A.H. , Kurniawan, T., Farandy, A.R., Apriliani, T., Nurlaili., Imron, M., Sajise, A.J..; Revisiting the climate change adaptation strategy for Jakarta’s coastal communities. Nat. Hazards. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 757–774. [Google Scholar]

- Marfai, M.A. , King, L.; Coastal flood management in Semarang, Indonesia. Environ. Geol. 2008, 55, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat; World cities report 2016: Urbanization and development – emerging futures. Nairobi, UN-Habitat, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).