1. Introduction

Brazil is the world largest producer and exporter of coffee and is renowned for its high-quality coffee produced in different regions (THRODE FILHO et al., 2020). The national production reached 54.79 million processed coffee bags in the 2023 harvest, and the per capita annual consumption of roasted and ground coffee is 4.9 kg. This is the preferred consumption form for 91% of the population (CONAB, 2024; ICO, 2023).

According to the Brazilian Coffee Industry Association (ABIC, 2023), the demand for coffee has grown in recent years, leading to an increase in associated industries, such as processing plants. Consequently, the residues generated during the coffee processing stage, including husks, parchment, mucilage, and wastewater, have significantly increased alongside rising consumption. These residues account for approximately 50% of processed coffee (ALMEIDA et al., 2021). According to Adans and Dougan (1985), for every ton of instant coffee produced in Brazil, 480 kg of waste is generated. The production and preparation of instant coffee generate between 8 and 15 million tons of coffee grounds worldwide annually (HORGAN et al., 2023).

According to Throde Filho et al. (2020), coffee grounds are a potentially polluting by-product. This by-product reduces seed germination and radicle growth in lettuce and cabbage plants while altering soil fauna, leading to a decline in earthworm populations (THRODE FILHO et al., 2017). As a result, this by-product becomes a strong environmental pollutant candidate due to the large amount of waste generated and its high toxicity potential. It increases substrate salinity, raising electrical conductivity and negatively affecting susceptible species such as lettuce. Under cultivation conditions with coffee grounds in the substrate, symptoms of toxicity and difficulty in water uptake are observed (THRODE FILHO et al., 2020).

According to Vidal (2001), Arabica coffee contains between 12% and 18% oils, predominately palmitic and linoleic fatty acids. Additionally, coffee grounds are low in nitrogen but rich in potassium, proteins, fibers, and phenolic compounds. Coffee grounds represent a significant by-product generated in the instant coffee agroindustry and can be considered a potential bio-input for agricultural use. Considering the enormous potential for coffee ground production in Brazil, due to the high volume of coffee produced and the population high consumption, it is essential to develop alternative uses for this by-product.

According to Hechmi et al. (2023), raw coffee grounds improve the biological, chemical, and physical properties of the soil by enhancing microbial activity, increasing organic matter content, improving aggregate stability, and promoting greater water retention. However, for optimal plant growth, vermicompost is recommended, as raw coffee grounds contain toxic polyphenols. Additionally, coffee grounds have significant nutritional value, with substantial concentrations of calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), potassium (K), phosphorus (P), and nitrogen, as well as an electrical conductivity ranging from 2.67 mS cm⁻¹ to 4.5 mS cm⁻¹ (CHRYSARGYRIS et al., 2021; HARDGROVE & LIVESLEY, 2016; LARA-RAMOS et al., 2024; TROUNG et al., 2018).

Coffee grounds are the main residue generated during coffee brewing and are typically discarded as household waste. However, these residues contain various compounds beneficial to society and can be integrated into the production chain (ARAÚJO et al., 2022; BATTISTA et al., 2022). Brazil is one of the largest importers of fertilizers, and using coffee grounds as a bio-input through composting presents a valuable alternative for reducing mineral fertilizer costs (LEITE et al., 2011). Additionally, the presence of lipids enhances the potential of coffee grounds for producing high-value-added energy sources, such as biodiesel (SUPANG et al., 2022).

The Brazilian vegetable market is highly diverse and segmented, with production volume concentrated on six main crops: potato, tomato, watermelon, lettuce, onion, and carrot. Family farming accounts for over half of this production (EMBRAPA, 2024). Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is the leading leafy vegetable produced in the country, both in terms of volume and market value (BRZEZINSKI et al., 2017). It is an excellent source of vitamins and minerals, offering high nutritional value (DEMARTELAERE et al., 2020). Since small-scale farmers widely cultivate lettuce, it is essential to develop techniques that optimize its production (DOS SANTOS FARIAS et al., 2017). Organic residues, such as coffee grounds, could serve as an alternative, as they possess characteristics that may help reduce production costs while increasing crop yield (DA SILVA et al., 2020).

The agroindustry has been generating large amounts of hard-to-degrade waste that contaminates the environment. Some of these residues can be reused in agriculture as biofertilizers, contributing to cost savings on fertilizers while preventing soil and water pollution. Aged coffee grounds, stored for seven to eight months, enhance the growth of tomato and radish plants and exhibit a repellent effect, reducing herbivory (HORGAN et al., 2023). In this context, research efforts are crucial to integrating coffee grounds into a fast-cycling production chain. This approach aligns with sustainable development by repurposing a polluting by-product within intensive food production systems, such as lettuce cultivation. Given this scenario, the present study aimed to identify the effects of coffee grounds on the growth and yield of lettuce plants.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

The study was conducted in a greenhouse covered with transparent plastic and sidewalls made of shade cloth, which intercepted 50% of solar radiation. The greenhouse was located at the Goiás State University (Universidade Estadual de Goiás), South Campus, UnU-Ipameri (17°43’19’’ S, 48°09’35’’ W, and an altitude of 773 m) in Ipameri, Goiás. This region has a tropical climate with dry winters and wet summers (Aw), according to the Köppen classification, with an average temperature of 20°C (ALVARES et al., 2013).

The experiment used 4 kg of substrate in polyethylene containers with a 5 kg capacity, following a completely randomized design in a 2×2 factorial arrangement. The primary treatment consisted of plants grown in two types of substrate: the first containing three parts soil and one part sand (01) and the second containing three parts soil, one part sand and 10% coffee grounds (02). The secondary treatment corresponded to irrigation with water (01) and irrigation with 10% coffee ground extract solution (02). Five replications were used, and the experimental unit consisted of a single pot containing one iceberg lettuce plant.

The coffee grounds used in the study were exclusively from Coffea arabica L. and were subjected to drying under full sun for one day after being spread in 2 cm thick layers. Regarding the primary treatments, a substrate was initially prepared by mixing three parts of soil with one part of washed sand. Coffee grounds were incorporated into the substrate at 10% of the final weight, meaning that for every 900 g of substrate (soil + sand), 100 g of coffee grounds were added. This mixture underwent an incubation process in the greenhouse for six months, during which it was aerated and irrigated monthly.

The methodology proposed by NBR 10.006 (ABNT, 2004b) was adopted for the secondary treatments with modifications. 100 g of coffee grounds was added to 1000 mL of tap water, followed by agitation. The process was modified by incorporating heating to extract the solubilized compounds. The mixture was heated and boiled for 10 minutes, then left to rest for 24 hours. After this period, it was filtered using a membrane filter, and the resulting liquid was used in the experiment. The obtained extract was diluted according to the fertigation treatments, ensuring that each 100 mL of irrigation solution contained 90 mL of tap water mixed with 10 mL of the extracted solution. The control treatment was irrigated with tap water sourced from the local water supply.

The plants were irrigated with water or fertilized with a coffee ground solution for 60 days. The irrigation volume applied was 300 mL per pot, based on the daily evapotranspiration of the lettuce crop. Since the crop coefficient (

Kc) for lettuce has not yet been determined for the Ipameri-GO region, a

Kc value of 1.00 was used, as estimated by FAO 56 (ALLEN et al., 1998). The volume was calculated by determining the reference evapotranspiration and the crop coefficient according to the following equation:

ETc = crop evapotranspiration

Kc = crop coefficient

ETo = reference evapotranspiration

The daily ETo calculation was performed using the Penman-Monteith method, as recommended by the FAO (SMITH et al., 1991). This calculation was based on daily data for maximum and minimum air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed collected from the INMET meteorological station in the municipality of Ipameri, GO. After 60 days of cultivation, the plants were evaluated.

2.2. Growth Variables

The head diameter was measured using a graduated ruler, assessing the lettuce head from one end to the other. The number of leaves was determined by counting all the leaves on the plant. Leaf area analysis was performed using the CI-202 Portable Laser Leaf Area Meter, measuring fully expanded leaves. Fresh mass was obtained by weighing the plant after harvest, while dry mass was determined by weighing the plant after drying for 72 hours in an oven at 70°C.

2.3. Chlorophyll Index

The chlorophyll index was determined using a portable chlorophyll meter, ClorofiLOG model CFL 1030, which provided values for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll, obtained by summing both, expressed in SPAD Chlorophyll Index units.

2.4. Leaf Nutrition

To evaluate leaf nitrogen content, 100 grams of dry mass from each plant were separated, ground, and sent for laboratory analysis to quantify nitrogen content in the plants. The leaf potassium content was measured using a portable potassium meter, HORIBA model LAQUAtwin K-11, which provided the nutrient content for each plant.

2.5. Mycorrhizal Colonization (MC)

To assess mycorrhizal colonization, the finest roots of each lettuce plant were separated, washed in running water, and preserved in 50% alcohol. The method proposed by PHILLIPS and HAYMAN (1970) was used to clarify and stain the roots. Quantification was performed using the grid plate method under a stereomicroscope according to GIOVANNETTI and MOSSE (1980), and the percentage of colonization was determined by the following equation:

Where:

CM: mycorrhizal colonization (%)

sn: number of non-colonized segments

sc: number of colonized segments

Mycorrhizal Spore Density (MSD)

For analysis of mycorrhizal spore density (MSD), the rhizosphere soil of lettuce plants was collected and sieved. From 50 g of soil, the mycorrhizal spores were separated and collected using a combination of the decantation and wet sieving methods (GERDEMANN and NICOLSON 1963) with centrifugation and flotation in sucrose (JENKINS, 1964). Mycorrhizal spore counting was performed using an acrylic plate with concentric rings, under a stereoscopic microscope with 40X magnification.

2.6. Soil Analysis

After collecting 250 g of substrate from each plot, soil chemical analysis and organic matter content were determined. The samples were then sent to a soil analysis laboratory for evaluation using atomic absorption equipment.

2.7. Statistical Procedures

The variables were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Newman-Keuls mean test, following a completely randomized design in a 2×2 factorial scheme with five replications. Multivariate data analysis was conducted using a correlation network approach with the qgraph package, and canonical variable analysis was performed using the candisc package, both executed in the RBio statistical software (BHERING, 2017).

3. Results and Discussion

The results obtained for the number of leaves, fresh mass, leaf area, potassium content in leaves, dry mass, total chlorophyll content, mycorrhizal colonization and mycorrhizal spore density in iceberg lettuce plants irrigated with a coffee ground solution and grown in soil containing coffee ground residue are shown in

Table 1.

The results showed that irrigation with a coffee ground solution and adding incubated coffee grounds to the soil significantly affected the parameters evaluated (

Table 1). However, significant interactions between treatments were observed only for total chlorophyll content, fresh mass, shoot dry mass and mycorrhizal spore density indicating that the effect of one treatment influenced the levels of the other treatment. These findings align with studies reporting that coffee grounds impact plant growth and development depending on the combinations and application rates used (CHRYSARGYRIS et al., 2021; HARDGROVE et al., 2016).

The results presented in

Table 2 refer to the pH, levels of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, the sum of bases, and organic matter in the soil used in the containers containing coffee grounds and irrigated with the coffee grounds solution. Significant interactions between treatments were observed for phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium levels.

It is possible to identify that all variables showed some level of significance, indicating that coffee grounds significantly influence the chemical properties of the soil. Some studies suggest that coffee grounds affect soil chemical characteristics and may impact physical and biological properties, such as aggregate structural stability, water retention, soil hydrophobicity, and microbial diversity (MESMAR et al., 2024). Additionally, according to Cervera-Mata et al. (2019), studies conducted with lettuce showed that composted coffee grounds, when applied in low doses, improved the Mg, Mn, K, and Na levels. This effect was attributed to the increased availability of these elements for plant uptake during composting and caffeine degradation.

The results of the mean test for the variables that did not show significant interaction between treatments are presented in

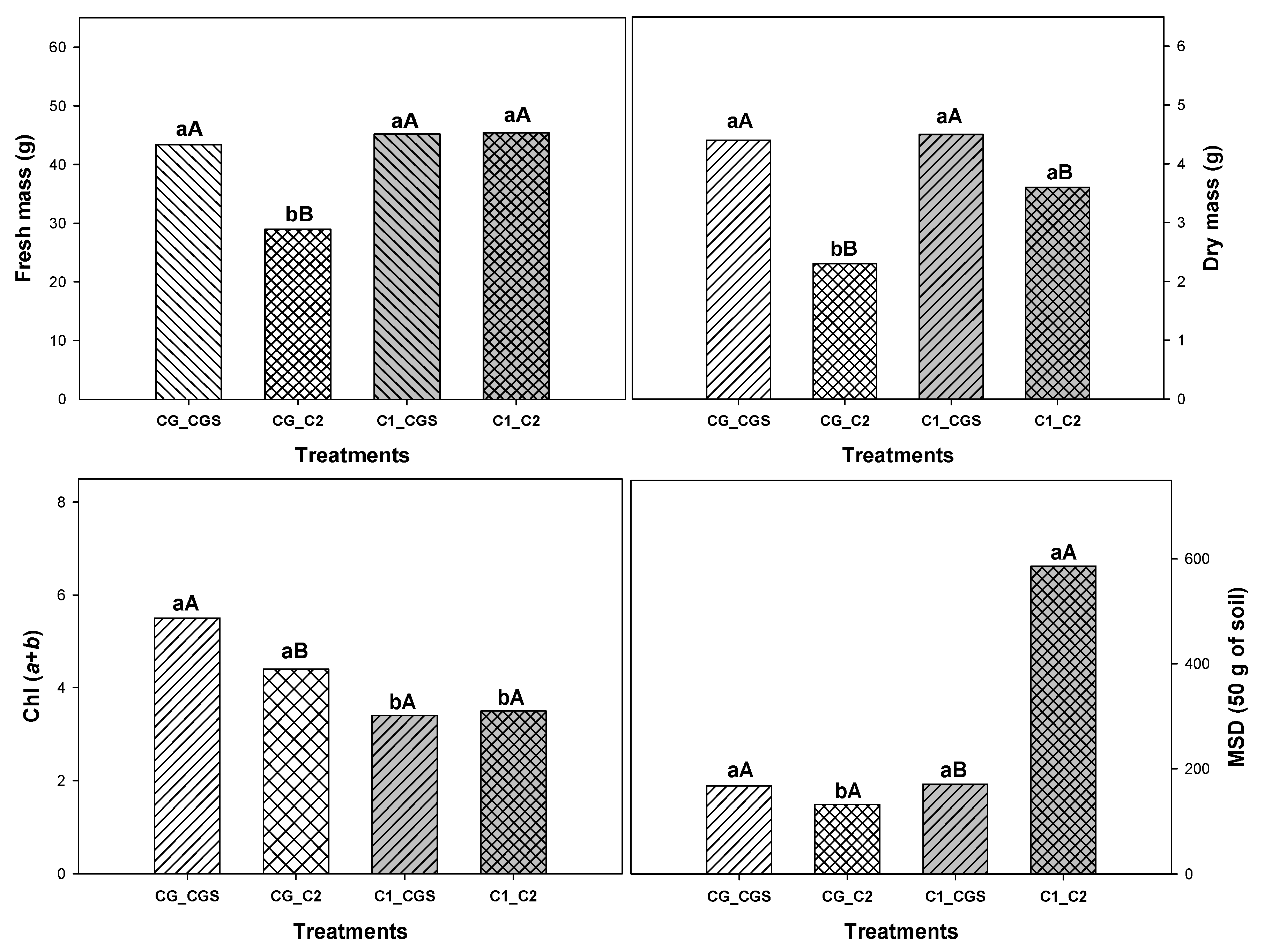

Table 3, including the following variables: number of leaves, leaf area, leaf potassium content, soil pH, base saturation, soil organic matter content and mycorrhizal colonization. The mean test for fresh mass, dry mass, total chlorophyll content and mycorrhizal spore density in lettuce plants is presented in

Figure 1, demonstrating the presence of significant interaction between treatments.

In general, coffee grounds added to the soil and incubated over several months reduced the growth of lettuce plants by decreasing leaf area, shoot fresh mass, shoot dry mass, chlorophyll content and mycorrhizal colonization. These results are likely related to the toxic effects of substances present in coffee grounds, as in all treatments where coffee grounds were incorporated into the soil (even before planting), regardless of whether they were irrigated with water or the coffee grounds solution, the plants exhibited reduced development. According to Hardgrove et al. (2016), the direct application of coffee grounds to the soil drastically reduces plant growth due to the presence of compounds that are toxic to plants.

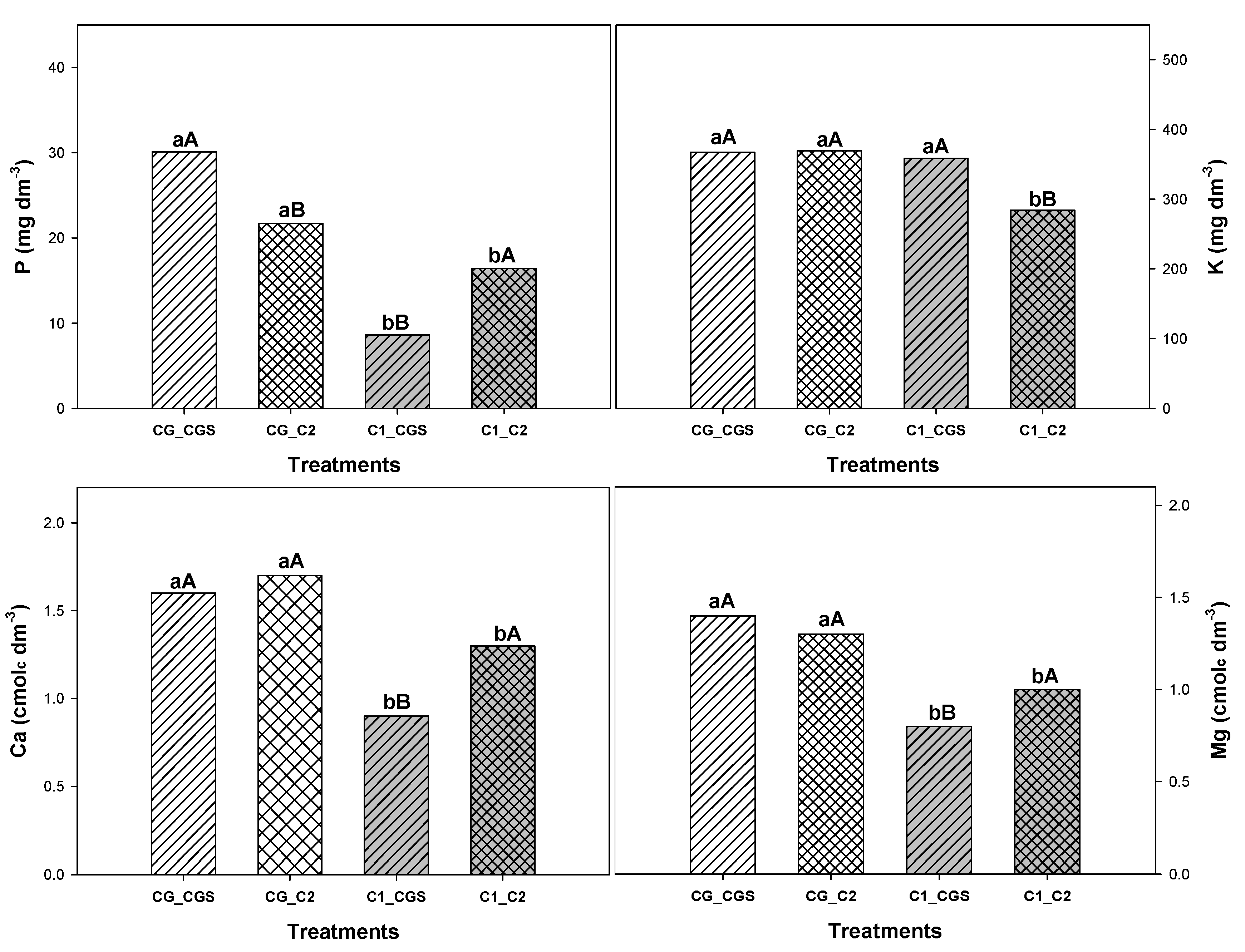

Despite the negative effects on lettuce growth, coffee grounds incorporated into the soil improved the soil and plant nutritional properties by increasing foliar potassium content by 22%, sum of bases by 27%, and organic matter content by 27%, as well as enhancing phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium levels (

Figure 2). These results are consistent with those reported by Comino et al. (2020), who found that incorporating coffee grounds into different soil types increased all organic matter fractions and raised total extractable carbon by approximately 200%. Therefore, it is suggested that coffee grounds act as a solvent when mixed with soil, containing a wide range of organic compounds such as tannic acid, cellulose, hemicellulose, lipids, organic acids, and polyphenols (CIESIELCZUK et al., 2018).

The significant increase in P content when coffee grounds were applied to the soil (Table 5) may explain the significant 22.79% decrease in mycorrhizal colonization of lettuce plants, as the increase in P content may inhibit the mutualistic symbiosis between fungus and plant, as demonstrated by Yazici et al. (2021) when studying the reduction in mycorrhizal colonization of the root, induced by phosphorus fertilization, and cadmium accumulation in wheat crops.

The use of coffee grounds in the irrigation solution proved to be the most promising treatment, as it enhanced plant vigor by promoting greater vegetative growth, evidenced by a 21% increase in the number of leaves, a 13% increase in leaf area, and a 34% increase in dry mass compared to the control treatment. Additionally, it raised leaf potassium content by 37%, although it had little impact on the chemical properties of the soil and the rate of mycorrhizal colonization of lettuce plants (

Table 3). These results indicate that incorporating coffee grounds into the soil and irrigating plants with a coffee grounds solution affect lettuce plant development differently. According to Chrysargyris et al. (2021), coffee grounds can be a biostimulant in plant development. However, the findings contradict those of Cervera-Mata et al. (2018), who reported reduced lettuce growth when using a coffee grounds solution.

The higher chlorophyll content observed in treatments containing coffee grounds, particularly in the treatment where coffee grounds were incorporated into the soil, may be related to the greater nutrient availability in this condition, especially magnesium, which is the central element of the chlorophyll molecule, as highlighted by Matos and Borges (2024).

The phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium levels in the soil used in the treatments are shown in Table 5. The results indicate that when coffee grounds are incorporated into the soil, there are increases of 25% in phosphorus, 23% in potassium, 24% in calcium, and 23% in magnesium levels compared to the control treatment. These findings align with studies showing that coffee grounds improve soil chemical fertility by increasing organic carbon, nitrogen, and potassium levels in the soil, as well as enhancing the absorption of certain macronutrients (Ca, Mg, K) and micronutrients (Co, Cu, Zn) (CERVERA-MATA et al., 2021).

According to Jeon et al. (2024), in a study comparing coffee grounds with NPK fertilizer, coffee grounds outperformed NPK in all evaluated parameters when applied to Japanese fennel. However, its impact on lettuce was adverse, highlighting that coffee grounds can effectively supply nutrients to plants, their application rates must be carefully regulated to avoid toxicity.

Still in relation to Table 4, it is possible to note a significant decrease in the density of mycorrhizal spores when using coffee grounds in the soil and in the irrigation solution. This negative effect can be explained by the fact that coffee residues contain toxic compounds such as tannins (ECKARDT et al., 2022) and chlorogenic acid (GONZÁLEZ-VÁSQUEZ et al., 2023), which have deleterious effects on soil microorganisms (SANCHEZ-HERNANDEZ et al., 2017).

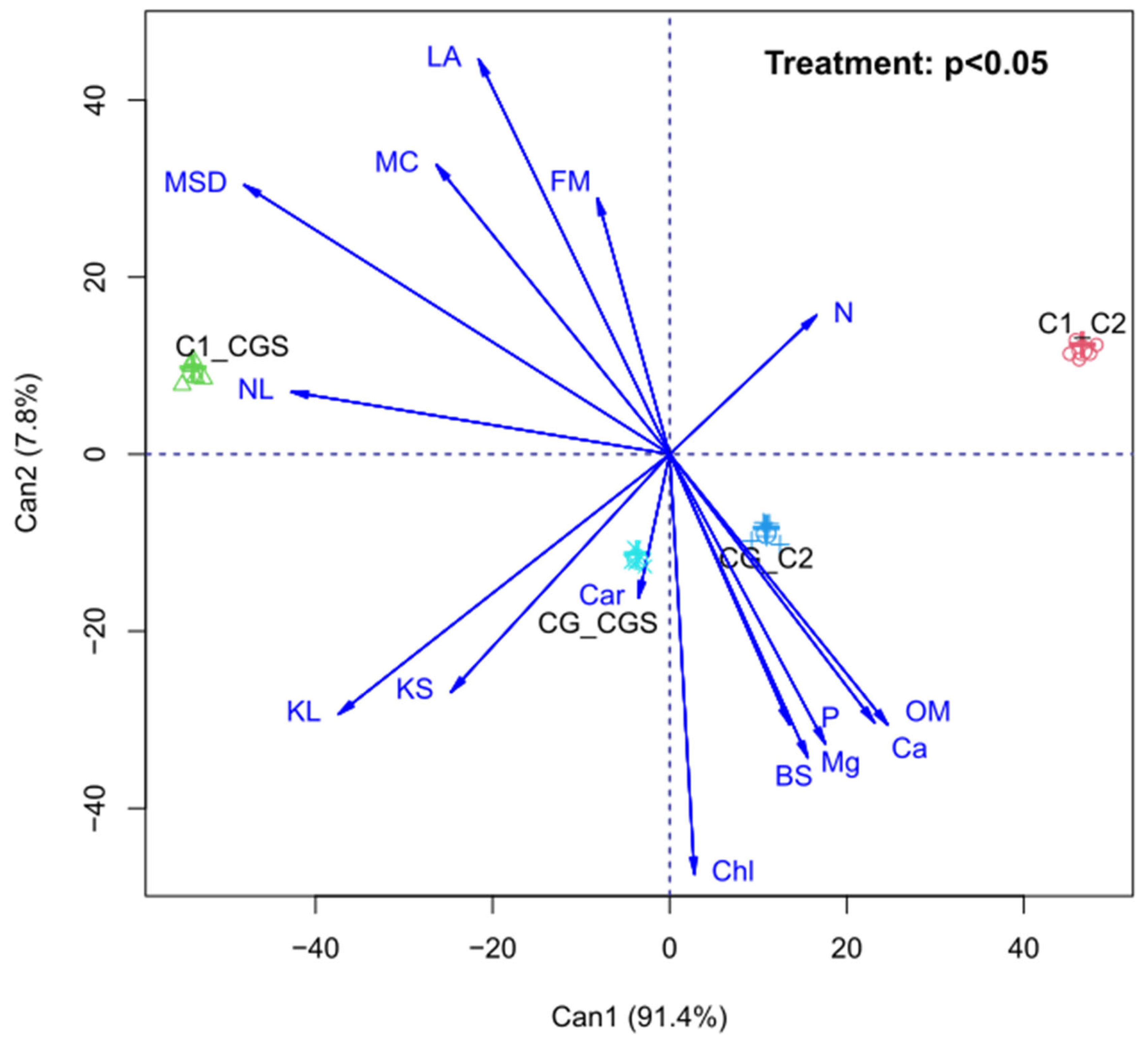

The canonical variable analysis for the ordination of variables along two axes is shown in

Figure 3 and accounts for 99.6% of the data variation. The results demonstrate the grouping of most soil-related variables on the right side of Axis 1, indicating that, regardless of the type of irrigation, the incorporation of coffee grounds into the soil alters its chemical properties. In contrast, plant growth variables are grouped on the left side of Axis 1, demonstrating that irrigation with a coffee grounds solution positively influenced the vegetative development of lettuce. These findings align with those reported by MESMAR et al. (2024), who highlight the improvement in soil fertility and increased crop yield associated with using coffee grounds.

The results indicate that coffee grounds are a promising by-product for agricultural use; however, their application requires careful management to prevent adverse effects on plant development. The use of coffee grounds represents an innovative approach and, when properly managed, functions as a high-quality organic fertilizer. Horticultural crops may achieve greater profitability by benefiting from enhanced growth and development through coffee grounds, a low-cost by-product (HORGAN et al., 2023).

4. Conclusions

Coffee grounds incorporated directly into the soil reduce lettuce growth and should not be used without prior treatment. Nevertheless, soil fertility is improved under this application condition due to increased macronutrients and organic matter.

Irrigation with a coffee grounds solution is a promising approach, as it demonstrates high potential as an agricultural bioinput for lettuce production. This solution enhances the species growth and development, producing vigorous plants with market value.

Using coffee grounds in agriculture alters the coffee production chain by adding value to a by-product with no commercial significance and redirecting it toward a sustainable agricultural practice.

Acknowledgments

To the Goiás State University for providing resources under the Pro-Projects Notice - Bioinputs - Strategic Institutional Project No. 23/2023, PrP protocol: 202303041, Sei Process No. 202200020023146.

References

- ABNT. 2004. NBR 10004. Resíduos Sólidos – Classificação. Brasil. - 2004b. NBR 10006. Procedimento Para Obtenção de Extrato Solubilizado de Resíduos Sólidos. Brasil.

- ADANS, M. R.; DOUGAN, W. Waste products - coffee technology, 1 ed., Londres, Elsevier Applied Science, 1985.

- ALLEN, R. G. et al. Crop evapotranspiration: Guidelines for computing crop water requirements. Rome: FAO, 1998.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DA INDÚSTRIA DO CAFÉ (ABIC). Indicadores da Indústria do Café em 2023. Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Café. Disponível em: <https://estatisticas.abic.com.br/estatisticas/indicadores-da-industria/indicadores-da-industria-de-cafe-2023/> Acessed on october 22, 2024.

- ALMEIDA, R. S et al. Reaproveitamento de resíduos de café em substratos para produção de mudas de Joannesia princeps. Pesquisa Florestal Brasileira, v.41, p.1-7, 2021.

- ARAUJO, M. N et al. A biorefinery approach for spent coffee grounds valorization using pressurized fluid extraction to produce oil and bioproducts: A systematic review. BioresourceTechnology Reports, v.18 p.101-113, 2022.

- ALVARES, C. A. et al. Köppen's climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift. v.22, n. 6, p.711-728, 2013.

- BATTISTA, F et al. The cascade biorefinery approach for the valorization of the spent coffee grounds. Renewable Energy, v.157, p.1203-1211, 2020.

- BHERING, L. L. RBio: A Tool for Biometric and Statistical Analysis Using the R Plataform. Crop Breeding and Applied Biotechnology, v.17, p.187-190, 2017. [CrossRef]

- BRZEZINSKI, C. R et al. Produção de cultivares de alface americana sob dois sistemas de cultivo. Revista Ceres, v.64, n.1, p.83-89, 2017.

- CERVERA-MATA, A et al. Impact of spent coffee grounds as organic amendment on soil fertility and lettuce growth in two Mediterranean agricultural soils. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science, v.64, n.6, p.790-804, 2018.

- CERVERA-MATA, A et al. Sequential effects of spent coffee grounds on the growth and mineral content of Lactuca sativa and chemical fertility of a Mediterranean agricultural soil. In: VIII Congresso Ibérico de las Ciencias del Suelo/VIII Congresso Ibérico de Ciências do Solo., 2021, Donostia-San Sebastián, Anais, 2021, p.110-113.

- CERVERA-MATA, A et al. Spent coffee grounds improve the nutritional value in elements of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) and are an ecological alternative to inorganic fertilizers. Food chemistry, v. 282, p.1-8, 2019.

- CHRYSARGYRIS, A et al. The use of spent coffee grounds in growing media for the production of Brassica seedlings in nurseries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, v.28, p.24279-24290, 2021.

- CIESIELCZUK, T et al. Acute toxicity of experimental fertilizers made of spent coffee grounds. Waste and Biomass Valorization, v.9, p.2157-2164, 2018.

- COMINO, F et al. Short-term impact of spent coffee grounds over soil organic matter composition and stability in two contrasted Mediterranean agricultural soils. Journal of Soils and Sediments, v.20, p.1182-1198, 2020.

- Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento (CONAB). Produção de café de 2024 é estimada em 54,79 milhões de sacas, influenciada por clima. Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. Disponível em: <https://www.conab.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/5740-producao-de-cafe-de-2024-e-estimada-em-54-79-milhoes-de-sacas-influenciada-por-clima> Acessed on october 22, 2024.

- DA SILVA, M. H et al. Cultivo de alface utilizando substratos alternativos. Scientia Naturalis, v.2, n.2, 2020.

- DEMARTELAERE, A. C. F et al. O cultivo hidropônico de alface com água de reuso. Brazilian Journal of Development, v.6, n.11, p.90206-90224, 2020.

- DOS SANTOS F et al. Cobertura do solo e adubação orgânica na produção de alface. Revista de Ciências Agrárias Amazonian Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, v.60, n.2, p.173-176, 2017.

- EMPRESA BRASILEIRA DE PESQUISA AGROPECUÁRIA (EMBRAPA). Resultados e impactos positivos da pesquisa agropecuária na economia, no meio ambiente e na mesa do brasileiro. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. Disponível em: < https://www.embrapa.br/grandes-contribuicoes-para-a-agricultura-brasileira/frutas-e-hortalicas> Acessed on october 22, 2024.

- HARDGROVE et al. Applying spent coffee grounds directly to urban agriculture soils greatly reduces plant growth. Urban For Urban Green, v.18, p.1-8, 2016.

- HECHMI, S et al. Impact of raw and pre-treated spent coffee grounds on soil properties and plant growth: A mini-review. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, v.25, n.9, p. 2831-2843, 2023.

- HORGAN, F.G et al. Spent Coffee Grounds Applied as a Top-Dressing or Incorporated into the Soil Can Improve Plant Growth While Reducing Slug Herbivory. Agriculture, v.13, n.2, p.257, 2023.

- JEON, Y.J et al. Yield, functional properties and nutritional compositions of leafy vegetables with dehydrated food waste and spent coffee grounds. Applied Biological Chemistry, v.67, n.1, p.22, 2024.

- LARA, R. L et al. New Insights into the Use of Spent Coffee Grounds By-products as Zn Bio-chelates for Lettuce Biofortification. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, v.24, n.1, p. 679-683, 2024.

- LEITE, S. T et al. compostagem como alternativa para aproveitamento da borra de café. Enciclopédia Biosfera. v.7, n.13, p.1068-1075, 2011.

- MATOS, F. S.; BORGES, L.P. Folha seca: Introdução à fisiologia vegetal. 2ª ed. Editora Appris, 2024, 200p.

- MESMAR, A. K. et al. The Effect of Recycled Spent Coffee Grounds Fertilizer, Vermicompost, and Chemical Fertilizers on the Growth and Soil Quality of Red Radish (Raphanus sativus) in the United Arab Emirates: A Sustainability Perspective. Foods, v.13, n.13, p.1997, 2024.

- ORGANIZAÇÃO INTERNACIONAL DO CAFÉ (OIC). Relatório sobre o mercado do café em junho de 2023. Nações Unidas, 2023. 14 p. Disponível em: <cmr-0623-p.pdf (icocoffee.org)> Acesso em 22 de agosto de 2023.

- SMITH, M. Report on expert consultation on procedures fro revision of FAO methodologies for crop water requirements. Rome: FAO, 1991.

- SUPANG, W et al. Ethyl acetate as extracting solvent and reactant for producing biodiesel from spent coffee grounds: A catalyst- and glycerol-free process. Journal of Supercritical Fluids, v.186, p.105586, 2022.

- THODE FILHO, S et al. Avaliação do Impacto do Extrato Solubilizado da Borra de Café sobre de Germinação de Sementes de Alface. Fronteiras: Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science. v.9, n.1, p.414-423, 2020.

- THODE FILHO, S et al. Assessment of Associated Impacts the Inappropriate Disposal of Coffee Waste on the Behavior Escape of the Earthworms. Revista Eletrônica Em Gestão, Educação e Tecnologia Ambiental. v.21, p.16-23, 2017.

- TRUONG, T.H.A.; MARSCHNER, P. Respiração, N disponível e N da biomassa microbiana em solo corrigido com misturas de materiais orgânicos diferindo na relação C/N e estágio de decomposição. Geoderma, v.319, p.167–174, 2018.

- VIDAL, H. M. Composição Lipídica e a Qualidade de Bebida Do Café (Coffea Arabica L.) Durante o Armazenamento. 2021. 93p. (Dissertação de mestrado – Pós-graduação em Agroquímica) -Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, 2021.

Figure 1.

Newman-Keuls mean test for fresh mass (FM), dry mass (DM), total chlorophyll content (Chl a+b), and mycorrhizal spore density (MSD) in lettuce plants grown in soil containing coffee grounds (CG) or common substrate (control (C1)) and irrigated with water (control (C2) or coffee grounds solution (CGS). Uppercase letters compare bars with the same internal color (white or gray), indicating the effect of irrigation with coffee grounds solution, while lowercase letters compare bars with the same internal contour and indicate the effect of coffee grounds on the soil. Bars with similar letters do not differ at a 5% probability level, according to the Newman-Keuls test.

Figure 1.

Newman-Keuls mean test for fresh mass (FM), dry mass (DM), total chlorophyll content (Chl a+b), and mycorrhizal spore density (MSD) in lettuce plants grown in soil containing coffee grounds (CG) or common substrate (control (C1)) and irrigated with water (control (C2) or coffee grounds solution (CGS). Uppercase letters compare bars with the same internal color (white or gray), indicating the effect of irrigation with coffee grounds solution, while lowercase letters compare bars with the same internal contour and indicate the effect of coffee grounds on the soil. Bars with similar letters do not differ at a 5% probability level, according to the Newman-Keuls test.

Figure 2.

Newman-Keuls mean test for the levels of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) in soil containing coffee grounds (CG) or common substrate - control (C1) and irrigated with water - control (C2) or coffee grounds solution (CGS). Uppercase letters compare bars with the same internal color (white or gray), indicating the effect of irrigation with coffee grounds solution, while lowercase letters compare bars with the same internal contour and indicate the effect of coffee grounds on the soil. Bars with similar letters do not differ at a 5% probability level, according to the Newman-Keuls test.

Figure 2.

Newman-Keuls mean test for the levels of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) in soil containing coffee grounds (CG) or common substrate - control (C1) and irrigated with water - control (C2) or coffee grounds solution (CGS). Uppercase letters compare bars with the same internal color (white or gray), indicating the effect of irrigation with coffee grounds solution, while lowercase letters compare bars with the same internal contour and indicate the effect of coffee grounds on the soil. Bars with similar letters do not differ at a 5% probability level, according to the Newman-Keuls test.

Figure 3.

Canonical variable analysis of nitrogen (N), leaf area (LA), fresh mass (FM), number of leaves (NL), leaf potassium (KL), soil potassium (KS), total chlorophylls (Chl), phosphorus (P), base saturation (BS), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), carotenoids (Car), mycorrhizal colonization (MC), mycorrhizal spore density (MSD), and organic matter (OM) in soil and lettuce plants grown in soil with coffee grounds or a soil substrate, irrigated with either water or a solution containing coffee grounds.

Figure 3.

Canonical variable analysis of nitrogen (N), leaf area (LA), fresh mass (FM), number of leaves (NL), leaf potassium (KL), soil potassium (KS), total chlorophylls (Chl), phosphorus (P), base saturation (BS), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), carotenoids (Car), mycorrhizal colonization (MC), mycorrhizal spore density (MSD), and organic matter (OM) in soil and lettuce plants grown in soil with coffee grounds or a soil substrate, irrigated with either water or a solution containing coffee grounds.

Table 1.

Summary of the analysis of variance for the number of leaves (NL), fresh mass (FM), leaf area (LA), leaf potassium content (K), dry mass (DM), total chlorophyll content (Chl a+b), mycorrhizal colonization (MC) and mycorrhizal spore density (MSD) in lettuce plants grown in soil containing coffee grounds and subjected to irrigation with a coffee ground solution.

Table 1.

Summary of the analysis of variance for the number of leaves (NL), fresh mass (FM), leaf area (LA), leaf potassium content (K), dry mass (DM), total chlorophyll content (Chl a+b), mycorrhizal colonization (MC) and mycorrhizal spore density (MSD) in lettuce plants grown in soil containing coffee grounds and subjected to irrigation with a coffee ground solution.

| Sources of variation |

|

|

Mean square |

| DF |

NL |

FM |

LA |

K |

DM |

Cl (a+b) |

MC |

MSD |

| Soil (S) |

1 |

5,0ns

|

413,0*

|

35,0*

|

41314*

|

3,0*

|

11.0 |

268.3*

|

262663**

|

| Error 1 |

8 |

1,0 |

25,0 |

0.4 |

4205 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

10.7 |

2241 |

| Irrigation (I) |

1 |

64,0*

|

255,0*

|

8,0*

|

142974*

|

12,0*

|

1.0 |

53.3ns

|

254025**

|

| SxI |

1 |

1,0ns

|

265,0*

|

0,0ns

|

4234ns

|

2,0*

|

2.0 |

69.1ns

|

180500**

|

| Error 2 |

8 |

2,0 |

265,0 |

0.6 |

2741 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

33.13 |

957.27 |

| Total |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CV1 |

6.8 |

12.5 |

7.3 |

17.5 |

8.1 |

13,5 |

11.51 |

17.94 |

| CV2 |

8.5 |

10.9 |

9.2 |

14.2 |

8.8 |

8.5 |

20.21 |

11.72 |

Table 2.

Summary of variance analysis for soil pH (pH), levels of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg), the sum of bases (BS), and organic matter in soil containing coffee grounds and cultivated with lettuce irrigated with a coffee grounds solution.

Table 2.

Summary of variance analysis for soil pH (pH), levels of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg), the sum of bases (BS), and organic matter in soil containing coffee grounds and cultivated with lettuce irrigated with a coffee grounds solution.

| Sources of variation |

Mean square |

| DF |

pH |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

BS |

OM |

| Soil (S) |

1 |

0.0ns

|

897*

|

10951*

|

1.0*

|

1.0*

|

6.0*

|

2.0*

|

| Error 1 |

8 |

0.0 |

6.0 |

389 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

| Irrigation (I) |

1 |

0.1*

|

0.5ns

|

6552*

|

0.3*

|

0.1ns

|

0.3ns

|

0.2ns

|

| SxI |

1 |

0.1ns

|

331*

|

7296*

|

0.2*

|

0.1*

|

0.3ns

|

0.2ns

|

| Error 2 |

8 |

0.0 |

60 |

532 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

| Total |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CV1 % |

3.1 |

13.6 |

5.7 |

14.1 |

16.4 |

13.9 |

14.3 |

| CV2 % |

2.4 |

11.5 |

6.7 |

10.7 |

9.0 |

8.8 |

16.4 |

Table 3.

Newman-Keuls mean test for number of leaves (NL), leaf area (LA), leaf potassium content (K), soil pH (pH), soil base saturation (BS), soil organic matter content (O.M) and mycorrhizal colonization (MC) with coffee grounds (CG) or common substrate - control (C1) and irrigated with water - control (C2) or coffee grounds solution (CGS).

Table 3.

Newman-Keuls mean test for number of leaves (NL), leaf area (LA), leaf potassium content (K), soil pH (pH), soil base saturation (BS), soil organic matter content (O.M) and mycorrhizal colonization (MC) with coffee grounds (CG) or common substrate - control (C1) and irrigated with water - control (C2) or coffee grounds solution (CGS).

| Treatment |

NL

|

LA

(cm2) |

K

(ppm) |

pH

|

BS

(cmolc dm-3) |

O.M

(%) |

MC

(%) |

| Substrate with and without coffee grounds |

| CG |

15.2a |

7.7b |

415.0a |

6.3a |

3.9a |

2.2a |

24.82b |

| C1 |

16.2a |

10.4a |

324.1b |

6.3a |

2.8b |

1.6b |

32.15a |

| Type of irrigation |

| CGS |

17.5a |

9.6a |

454.1a |

6.4a |

3.2a |

1.7a |

30.11a |

| C2 |

13.9b |

8.4b |

285.0b |

6.2b |

3.5a |

2.0a |

26.85a |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).