Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Human Erythrocytes

4.3. Plant Seeds

4.4. Protein Extraction of Phaseolus acutifolius Seeds (TBE)

4.5. Antinutritional Compounds

4.5.1. Lectins Assay

4.5.2. Trypsin Inhibitors Determination

4.5.3. Tannins Determination

4.5.4. Saponins Determination

4.6. Lethal Median Dose (LD50)

4.7. Evaluation of the Genotoxic Capacity of TBE by the Micronucleus Assay and Cytotoxicity to Bone Marrow

4.8. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay in Rat Intestinal Epithelial Cells

4.9. Epithelial Cell Assay

3. Results

2.1. Protein Extract and Antinutritional Compounds

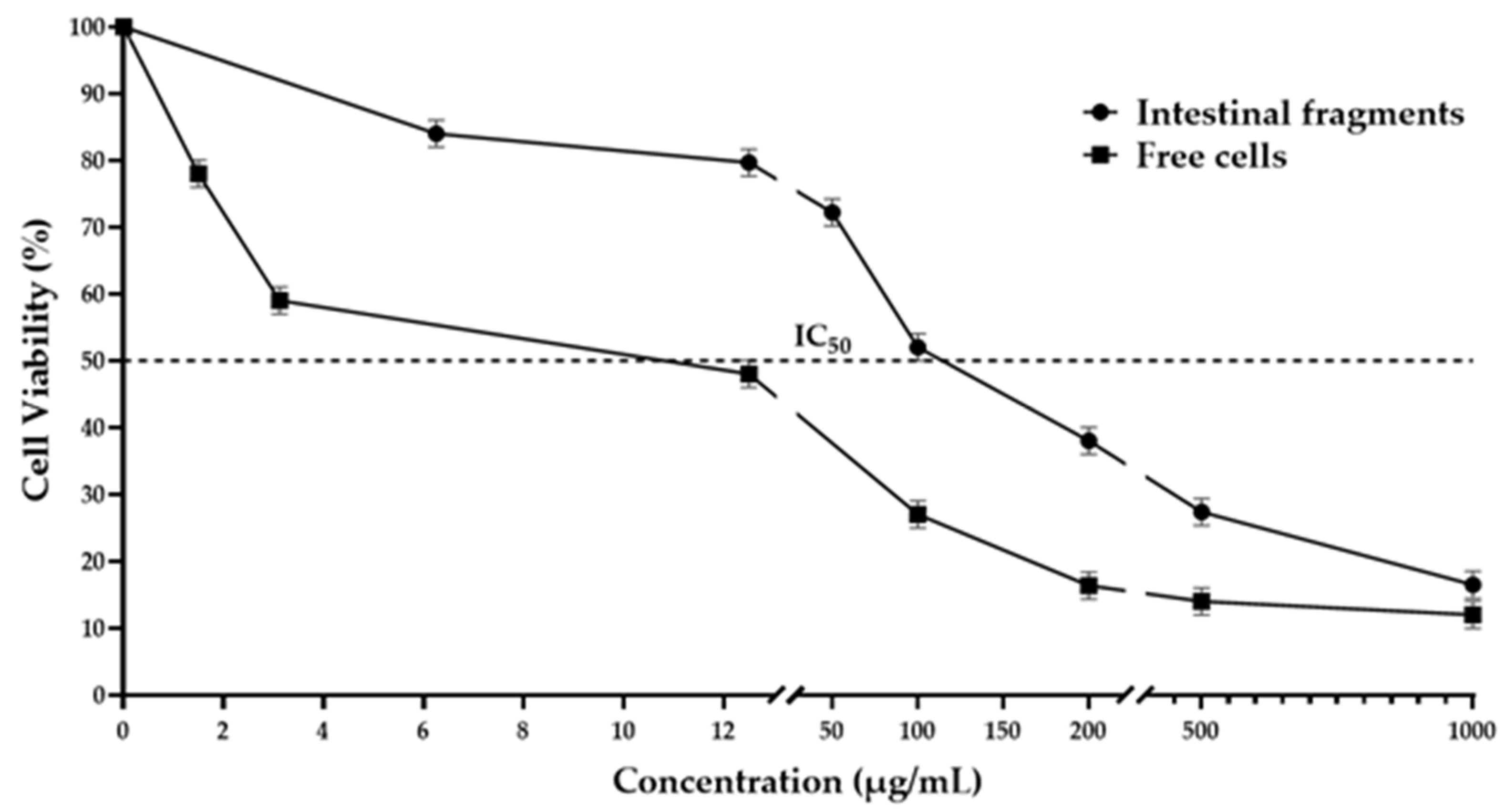

2.2. Epithelial Cell Cytotoxicity

2.2.1. Smear Assay

2.2.2. Free Epithelial Cells

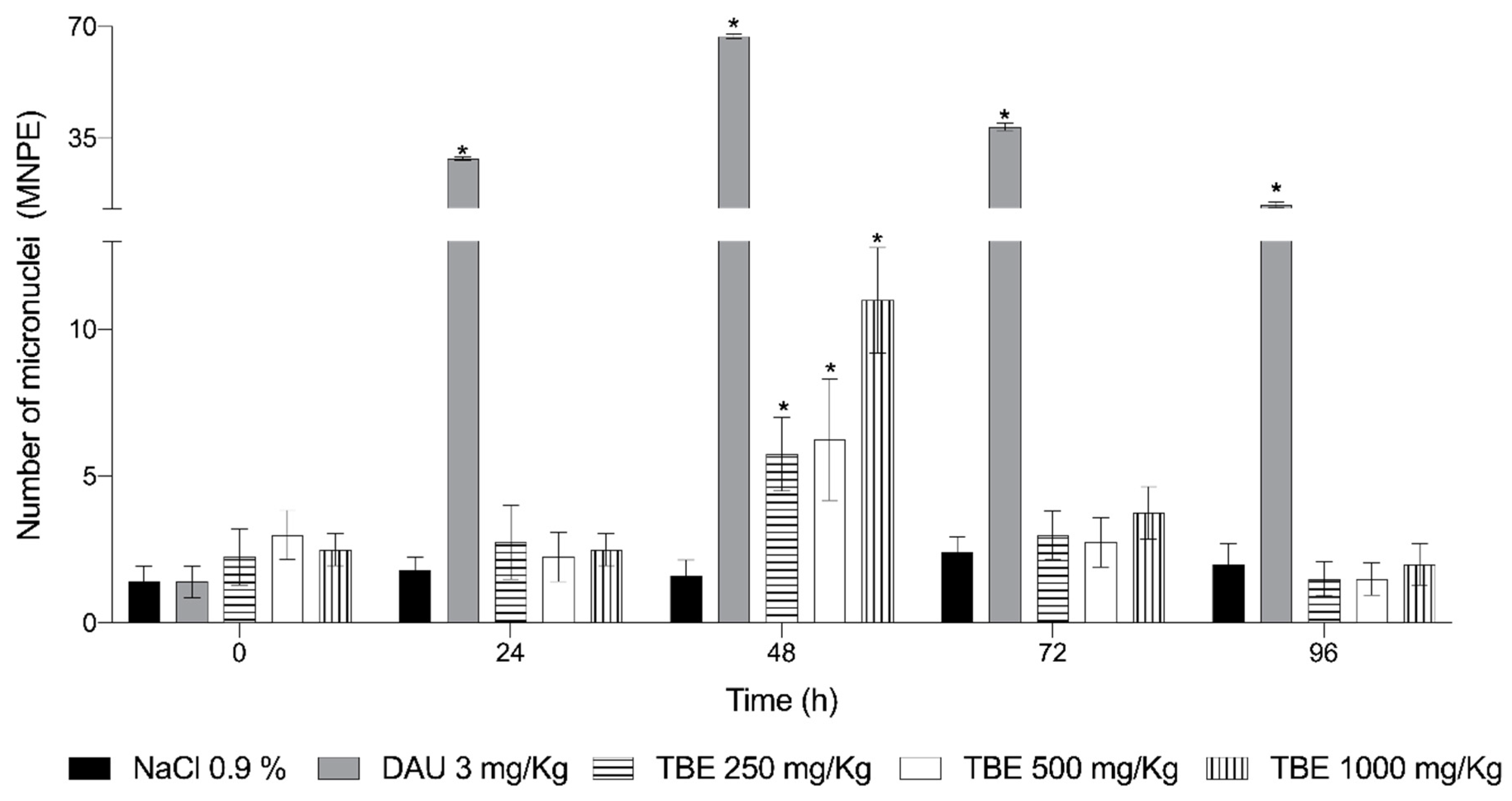

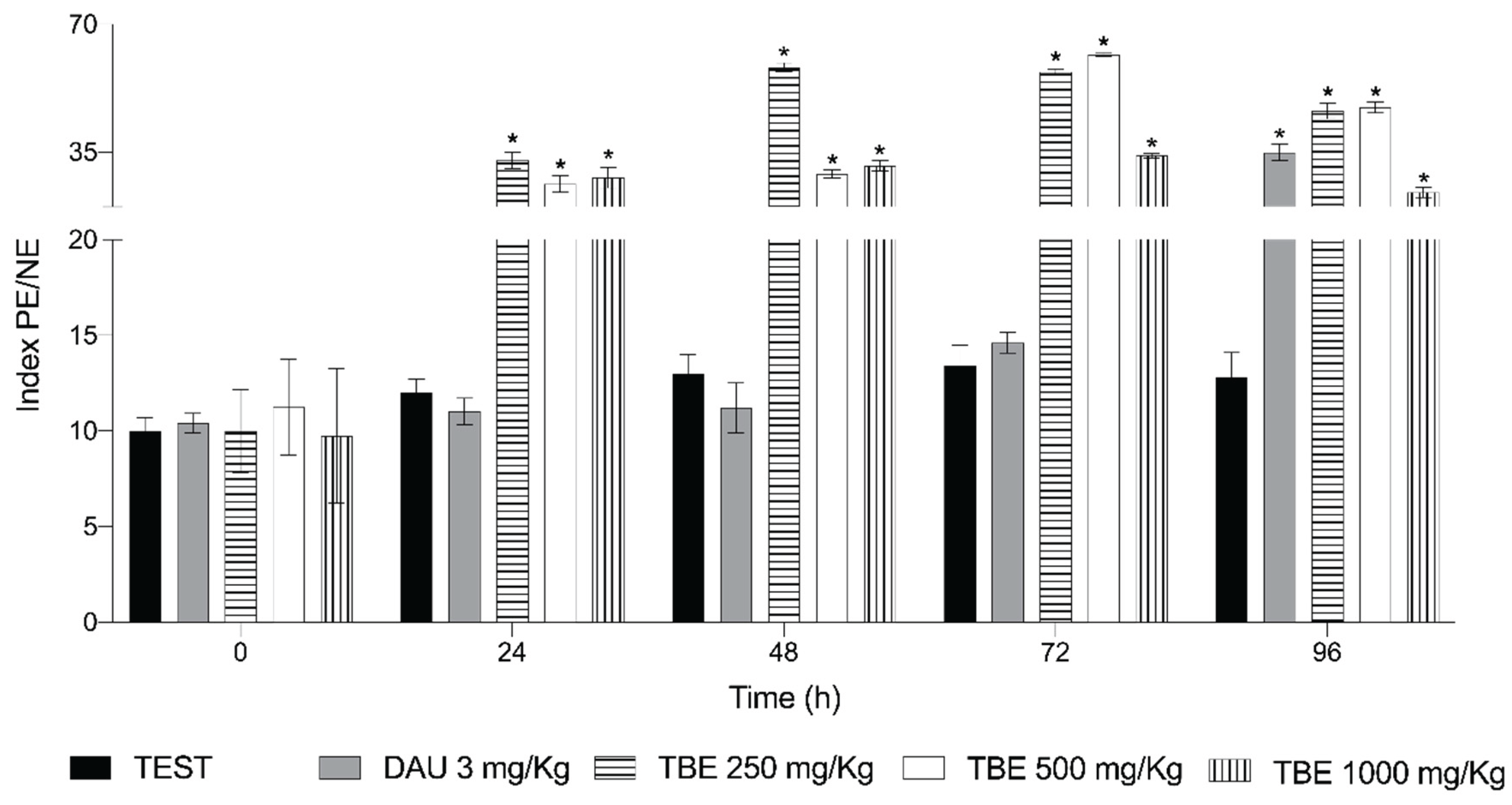

2.4. Evaluation of the Genotoxic Capacity of TBE by the Micronucleus Assay and Cytotoxicity to Bone Marrow

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Vikas, R.; Kalamvrezos, N.D. The Global Economy of pulses. Knowledge and Power in the Global Economy: The Effects of School Reform in a Neoliberal/Neoconservative Age: Second Edition. 2019. 91–99 p.

- Panorama Agroalimentario frijol 2016. Panorama Agroalimentario. México; 2016 Nov. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/200638/Panorama_Agroalimentario_Frijol_2016. 27 February 2025.

- Scheerens, J.C.; Tinsley, A.M; Abbas, I.R.; Weber, C.W. The Nutritional Significance of Tepary Bean Consumption. Desert Plants. 1983;5(1):11–4 y 50–6. https://repository.arizona. 1015. [Google Scholar]

- De Mejia, E.G.; Valadez-Vega, M.D.C.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Loarca-Pina, G. Tannins, Trypsin Inhibitors and Lectin Cytotoxicity in Tepary (Phaseolus acutifolius) and Common (Phaseolus vulgaris) Beans. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2005, 60, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-López, F.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Milán-Carrillo, J.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Canizalez-Roman, V.A.; León-Sicairos C., R.; Reyes-Moreno, C. Nutritional and antioxidant potential of a desert underutilized legume - tepary bean (Phaseolus acutifolius). Optimization of germination bioprocess. Food Sci. Technol (Brazil). 2018;38:254–62. https://www.scielo.br/j/cta/a/XYLNRcWKDM4vkhnBTM4DjKz/?

- Michaels T.E. Grain Legumes and Their Dietary Impact: Overview [Internet]. 2nd ed. Reference Module in Food Science. Elsevier.; 2016. 1–8 p. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.00040-8.

- Tharanathan, R.; Mahadevamma, S. Grain legumes—a boon to human nutrition. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 14, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, G.S.; Xiao, C.W.; Cockell, K.A. Impact of Antinutritional Factors in Food Proteins on the Digestibility of Protein and the Bioavailability of Amino Acids and on Protein Quality. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S315–S332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominelli, E.; Sparvoli, F.; Lisciani, S.; Forti, C.; Camilli, E.; Ferrari, M.; Le Donne, C.; Marconi, S.; Vorster, B.J.; Botha, A.-M.; et al. Antinutritional factors, nutritional improvement, and future food use of common beans: A perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 992169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, G.S.; A Cockell, K.; Sepehr, E. Effects of Antinutritional Factors on Protein Digestibility and Amino Acid Availability in Foods. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Guzmán, N.; Gallegos-Infante, J.; González-Laredo, R.; Castillo-Antonio, P.; Delgado-Licon, E.; Ibarra-Pérez, F. Functional properties of three common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cultivars stored under accelerated conditions followed by extrusion. LWT 2006, 39, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, G.; More, L.J.; McKenzie, N.H.; Pusztai, A. The effect of heating on the haemagglutinating activity and nutritional properties of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) seeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1982, 33, 1324–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arija, I.; Centeno, C.; Viveros, A.; Brenes, A.; Marzo, F.; Illera, J.C.; Silvan, G. Nutritional Evaluation of Raw and Extruded Kidney Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. var. Pinto) in Chicken Diets. Poult. Sci. 2006, 85, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Chang, S.K.C.; Liu, Z.; Xu, B. Elimination of Trypsin Inhibitor Activity and Beany Flavor in Soy Milk by Consecutive Blanching and Ultrahigh-Temperature (UHT) Processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7957–7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, K.A.; Prudêncio, S.H.; Fernandes, K.F. Changes in the Functional Properties and Antinutritional Factors of Extruded Hard-to-Cook Common Beans ( Phaseolus vulgaris, L. ). J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C286–C290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, K.A.; Prudêncio, S.H.; Fernandes, K.F. Changes in the Functional Properties and Antinutritional Factors of Extruded Hard-to-Cook Common Beans ( Phaseolus vulgaris, L. ). J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C286–C290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, C.; Cordoba-Diaz, D.; Cordoba-Diaz, M.; Girbés, T.; Jiménez, P. Effects of temperature, pH and sugar binding on the structures of lectins ebulin f and SELfd. Food Chem. 2017, 220, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demma, J.; Engidawork, E.; Hellman, B. Potential genotoxicity of plant extracts used in Ethiopian traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, W. The micronucleus test. Mutat. Res. Mutagen. Relat. Subj. 1975, 31, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alice, C.; Vargas, V.; Silva, G.; de Siqueira, N.; Schapoval, E.; Gleye, J.; Henriques, J.; Henriques, A. Screening of plants used in south Brazilian folk medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 35, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Hayashi, M. In vivo rodent micronucleus assay: protocol, conduct and data interpretation. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2000, 455, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-González, G.; Gómez-Meda, B.; Zamora-Perez, A.; Ramos-Ibarra, M.; Batista-González, C.; Espinoza-Jiménez, S.; Gallegos-Arreola, M.; Álvarez-Moya, C.; Torres-Bugarín, O. Induction of micronuclei in proestrus vaginal cells from colchicine- and cyclophosphamide-treated rats. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2003, 42, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Meda, B.C.; Zúñiga-González, G.M.; Zamora-Perez, A.; Ramos-Ibarra, M.L.; Batista-González, C.M.; Torres-Mendoza, B.M. Folate supplementation of cyclophosphamide-treated mothers diminishes micronucleated erythrocytes in peripheral blood of newborn rats. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2004, 44, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Perez, A.L.; Lazalde-Ramos, B.P.; Sosa-Macías, M.G.; Gómez-Meda, B.C.; Torres-Bugarín, O.; Zúñiga-González, G.M. Methylphenidate lacks genotoxic effects in mouse peripheral blood erythrocytes. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 34, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teniente-Martínez, G.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Valadez-Vega, M.d.C.; Montañez-Soto, J.L.; Acosta-García, G.; González-Cruz, L. Cytotoxic and genotoxic activity of protein isolate of ayocote beans and anticancer activity of their protein fractions. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringe, M.L.; Love, M.H. Kinetics of Protein Quality Change in an Extruded Cowpea-Corn Flour Blend under Varied Steady-State Storage Conditions. J Food Sci. 1988;53(2):584–8. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vioque, R.; Clemente, A.; Vioque, J.; Bautista, J.; Millán, F. Protein isolates from chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): chemical composition, functional properties and protein characterization. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lqari, H.; Vioque, J.; Pedroche, J.; Millán, F. Lupinus angustifolius protein isolates: chemical composition, functional properties and protein characterization. Food Chem. 2002, 76, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horax, R.; Hettiarachchy, N.S.; Chen, P.; Jalaluddin, M. Preparation and Characterization of Protein Isolate from Cowpea ( Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.). J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, fct114–fct118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, J.C.M.; Vázquez-Mata, N.; Torres, N.; Gil-Zenteno, L.; Bressani, R. Preparation and Characterization of Protein Isolate from Fresh and Hardened Beans ( Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, C96–C102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, J.C.M.; Vázquez-Mata, N.; Torres, N.; Gil-Zenteno, L.; Bressani, R. Preparation and Characterization of Protein Isolate from Fresh and Hardened Beans ( Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, C96–C102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Morales-González, J.A.; Delgado-Olivares, L.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; López-Contreras, L.; Bautista, M.; Velázquez-González, C. Phytochemical, cytotoxic, and genotoxic evaluation of protein extract ofAmaranthus hypochondriacusseeds. CyTA - J. Food 2021, 19, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado del Frijol situación y prospectiva. Mercado del frijol, situación y prospectiva. Palacio Legislativo de San Lázaro, Ciudad de México. Febrero 2020. Available from: http://www.cedrssa.gob. 22 January 2025.

- Feeny, P. Inhibitory effect of oak leaf tannins on the hydrolysis of proteins by trypsin. Phytochemistry 1969, 8, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.; Bautista, M.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A.; González-Amaro, R.M.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Morales-González, J.A.; González-Cruz, L. Effects of Germination and Popping on the Anti-Nutritional Compounds and the Digestibility of Amaranthus hypochondriacus Seeds. Foods 2022, 11, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgarbieri, V.C.; Galeazzi, M.A.M. QUANTIFICATION AND SOME CHEMICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF NITROGENOUS SUBSTANCES FROM VARIETIES OF COMMON BEANS (PHASEOLUS VULGARIS, L.). J. Food Biochem. 1990, 14, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Tabtabaei, S.; Marsolais, F.; Legge, R.L. Physicochemical characterization of a navy bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) protein fraction produced using a solvent-free method. Food Chem. 2016, 208, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.B.; Aleem, S.; Khan, M.R.; Ashraf, S.; Busquets, R. Quantitative Estimation of Protein in Sprouts of Vigna radiate (Mung Beans), Lens culinaris (Lentils), and Cicer arietinum (Chickpeas) by Kjeldahl and Lowry Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Albores, F.; de la Fuente, G.; Agundis, C.; Córdoba, F. Purification and Characterization of A Lectin from Phaseolus Acu-Tifolius Var. Latifolius. Prep. Biochem. 1987, 17, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Guzmán-Partida, A.M.; Soto-Cordova, F.J.; Álvarez-Manilla, G.; Morales-González, J.A.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Villagómez-Ibarra, J.R.; Zúñiga-Pérez, C.; Gutiérrez-Salinas, J.; Becerril-Flores, M.A. Purification, Biochemical Characterization, and Bioactive Properties of a Lectin Purified from the Seeds of White Tepary Bean (Phaseolus Acutifolius Variety Latifolius). Molecules 2011, 16, 2561–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilés-Gaxiola, S.; Chuck-Hernández, C.; Saldívar, S.O.S. Inactivation Methods of Trypsin Inhibitor in Legumes: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2017, 83, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, P.; Daelemans, L.; Selis, L.; Raes, K.; Vermeir, P.; Eeckhout, M.; Van Bockstaele, F. Comparison of the Chemical and Technological Characteristics of Wholemeal Flours Obtained from Amaranth (Amaranthus sp.), Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) and Buckwheat (Fagopyrum sp.) Seeds. Foods 2021, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkowicz, K.; Sosulski, F.W. Antinutritive Factors in Eleven Legumes and Their Air-classified Protein and Starch Fractions. J. Food Sci. 1982, 47, 1301–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olloqui, E.J.; Castañeda-Ovando, A.; Evangelista-Lozano, S.; Alanís-García, E.; Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Añorve-Morga, J. Measurement of nutrients and minor components of a non-toxic variety of Jatropha curcas. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 16, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.; Bautista, M.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A.; González-Amaro, R.M.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Morales-González, J.A.; González-Cruz, L. Effects of Germination and Popping on the Anti-Nutritional Compounds and the Digestibility of Amaranthus hypochondriacus Seeds. Foods 2022, 11, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cruz, L.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Juárez-Goiz, J.M.S.; Flores-Martínez, N.L.; Montañez-Soto, J.L.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A. Partial Purification and Characterization of the Lectins of Two Varieties of Phaseolus coccineus (Ayocote Bean). Agronomy 2022, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Villagómez-Ibarra, J.R. Partial Characterization of Lectins Purified from the Surco and Vara (Furrow and Rod) Varieties of Black Phaseolus vulgaris. Molecules 2022, 27, 8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Celis, U.; López-Martínez, J.; Blanco-Labra, A.; Cervantes-Jiménez, R.; Estrada-Martínez, L.E.; García-Pascalin, A.E.; Guerrero-Carrillo, M.D.J.; Rodríguez-Méndez, A.J.; Mejía, C.; Ferríz-Martínez, R.A.; et al. Phaseolus acutifolius Lectin Fractions Exhibit Apoptotic Effects on Colon Cancer: Preclinical Studies Using Dimethilhydrazine or Azoxi-Methane as Cancer Induction Agents. Molecules 2017, 22, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chel-Guerrero, L.; Gallegos-Tintoré, S.; Martínez-Ayala, A.; Castellanos-Ruelas, A.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Functional Properties of Proteins from Lima Bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) Seeds. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2011, 17, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inthachat, W.; Suttisansanee, U.; Kruawan, K.; On-Nom, N.; Chupeerach, C.; Temviriyanukul, P. Evaluation of Mutagenicity and Anti-Mutagenicity of Various Bean Milks Using Drosophila with High Bioactivation. Foods 2022, 11, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.; Pusztai, A.; Clarke, E. Kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) lectin-induced lesions in rat small intestine: 1. Light microscope studies. J. Comp. Pathol. 1980, 90, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.; Sotelo, A.; González-Garza, M.T. Differential cytotoxicity of the isolated protein fraction of Escumite bean (Phaseolus acutifolius). Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1982, 31, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.d.A.; Ainouz, I.L.; de Oliveira, J.T.A.; Cavada, B.S. Plant lectins, chemical and biological aspects. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1991, 86, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramoto, K. Lectins as Bioactive Proteins in Foods and Feeds. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2017, 23, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, F.; Pusztai, A. Toxicity of Kidney Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) in Rats: Changes in Intestinal Permeability. Digestion 1985, 32, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Simpson, B.K.; Sun, H.; Ngadi, M.O.; Ma, Y.; Huang, T. Phaseolus vulgaris lectins: A systematic review of characteristics and health implications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.; Levy-Benshimol, A.; Carmona, A. Effect of Phaseolus vulgaris lectins on glucose absorption, transport, and metabolism in rat everted intestinal sacs. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1993, 4, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar-Valle, M.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Mojica, L.; Morales-Hernández, N.; Reyes-Ramírez, H.; Enríquez-Vara, J.N.; García-Morales, S. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity, and Antinutritional Content of Legumes: A Comparison between Four Phaseolus Species. Molecules 2020, 25, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafont, J.; Rouanet, J.; Gabrion, J.; Assouad, J.; Infante, Z.; Besançon, P. Duodenal Toxicity of Dietary Phaseolus vulgaris Lectins in the Rat: An Integrative Assay. Digestion 1988, 41, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nciri, N.; Cho, N. New research highlights: Impact of chronic ingestion of white kidney beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L. var. Beldia) on small-intestinal disaccharidase activity in Wistar rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotelo, A.; Arteaga, M.E.; Frías, M.I.; González-Garza, M.T. Cytotoxic effect of two legumes in epithelial cells of the small intestine. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1980, 30, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J.; Van Der Poel, A.F.B.; Mouwen, J.M.V.M.; Weerden, J.M.V.M. Effect of variable protein contents in diets containing Phaseolus vulgaris beans on performance, organ weights and blood variables in piglets, rats and chickens. Br. J. Nutr. 1990, 64, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardocz, S.; Grant, G.; Ewen, S.W.; Duguid, T.J.; Brown, D.S.; Englyst, K.; Pusztai, A. Reversible effect of phytohaemagglutinin on the growth and metabolism of rat gastrointestinal tract. Gut 1995, 37, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Villanueva, A.; Caballero-Ortega, H.; Abdullaev-Jafarova, F.; Garfias, Y.; Jiménez-Martínez, M.d.C.; Bouquelet, S.; Martínez, G.; Mendoza-Hernández, G.; Zenteno, E. Lectin fromPhaseolus acutifoliusvar. escumite: Chemical Characterization, Sugar Specificity, and Effect on Human T-Lymphocytes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5781–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Alvarez-Manilla, G.; Riverón-Negrete, L.; García-Carrancá, A.; Morales-González, J.A.; Zuñiga-Pérez, C.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Esquivel-Soto, J.; Esquivel-Chirino, C.; Villagómez-Ibarra, R.; et al. Detection of Cytotoxic Activity of Lectin on Human Colon Adenocarcinoma (Sw480) and Epithelial Cervical Carcinoma (C33-A). Molecules 2011, 16, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, L.; Gomes, J.; Stringheta, P.; Gontijo, Á.; Padovani, C.; Ribeiro, L.; Salvadori, D. Black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as a protective agent against DNA damage in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-T.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-F.; Peng, F.-C.; Liu, S.-H. Genotoxicity and 28-day oral toxicity studies of a functional food mixture containing maltodextrin, white kidney bean extract, mulberry leaf extract, and niacin-bound chromium complex. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 92, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassinetti, S.; Gabriele, M.; Caltavuturo, L.; Longo, V.; Pucci, L. Antimutagenic and Antioxidant Activity of a Selected Lectin-free Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Two Cell-based Models. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2015, 70, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.L.S.; Marcussi, S.; Sátiro, L.C.; Pereira, C.A.; Andrade, L.F.; Davide, L.C.; dos Santos, C.D. Application of Comet assay to assess the effects of white bean meal on DNA of human lymphocytes. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 48, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanding, O.J.; Abdullah, N.; Noor, Z.M.; Hashim, N.; Saari, N.; Yahya, M.F.Z.; Abdullah, M.F.F. Genotoxicity and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Winged Bean (Psophocarpus Tetragonolobus) Protein Hydrolysate. Malaysian Applied Biology. 2015;44(3):6–11.ttps://www.academia. 1698. [Google Scholar]

- Lylo, V.; Karpova, I.; Kotsarenko, K.; Macewicz, L.; Ruban, T.; Lukash, L. LECTINS OF SAMBUCUS NIGRA IN REGULATION OF CELLULAR DNA-PROTECTIVE MECHANISMS. Acta Hortic. 2015, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-González, I.; Vázquez-Sánchez, J.; Chamorro-Cevallos, G.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E. Effect of Spirulina maxima and Its Protein Extract on Micronuclei Induction by Hydroxyurea in Pregnant Mice and Their Fetuses. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisenando, H.A.A.A.C.N.; Macedo, M.F.S.; Saturnino, A.C.R.D.; Coelho, L.C.B.B.; de Medeiros, S.R.B. Evaluation of the genotoxic potential of Bauhinia monandra leaf lectin (BmoLL). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, G.D.B.; Aiub, C.A.F.; Felzenszwalb, I.; Dantas, E.K.C.; Araújo-Lima, C.F.; Júnior, C.L.S. In vitro biochemical characterization and genotoxicity assessment of Sapindus saponaria seed extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 276, 114170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, G.C.; de Oliveira, A.M.; Machado, J.C.B.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; de Medeiros, P.L.; Soares, L.A.L.; de Souza, I.A.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Napoleão, T.H. Toxicity assessment of saline extract and lectin-rich fraction from Microgramma vacciniifolia rhizome. Toxicon 2020, 187, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpova, I.; Lylo, V.; Macewicz, L.; Kotsarenko, K.; Palchykovska, L.; Ruban, T.; Lukash, L. LECTINS OF SAMBUCUS NIGRA AS BIOLOGICALLY ACTIVE AND DNA-PROTECTIVE SUBSTANCES. Acta Hortic. 2015, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Lyu, S. The Antimutagenic Effect of Mistletoe Lectin (Viscum album L. var. coloratum agglutinin). Phytotherapy Res. 2011, 26, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoessli, D.C.; Ahmad, I. Mistletoe Lectins: Carbohydrate-Specific Apoptosis Inducers and Immunomodulators. Curr. Org. Chem. 2008, 12, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H.S. Nandini, N.; Prabhudas, A. V. M. H.S. Nandini, N.; Prabhudas, A. V. M.; Krutty P.R.K.; P.K. Partial characterization, cytotoxic and genotoxic properties of glycoproteins from Syzygium cumini Lam. Skeel (Black plum). Int J of Pharmaceutical Sci and Res. 2020;1(12):6333–41. [CrossRef]

- De Barros, M.C.; Videres, L.C.C.d.A.; Batista, A.M.; Guerra, M.M.P.; Coelho, L.C.B.B.; Da Silva, T.G.; Napoleão, T.H.; Paiva, P.M.G. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assessment of the extract and lectins from Moringa oleifera Lam. Seeds / Avaliação da citotoxicidade e genotoxicidade do extrato e lectinas das sementes de Moringa oleifera Lam. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 94854–94869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nagae, Y.; Li, J.; Sakaba, H.; Mozawa, K.; Takahashi, A.; Shimizu, H. The micronucleus test and erythropoiesis. Effects of erythropoietin and a mutagen on the ratio of polychromatic to normochromatic erythrocytes (P/N ratio). Mutagenesis 1989, 4, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Sung, J.H.; Ji, J.H.; Song, K.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, C.S.; Yu, I.J. In vivo Genotoxicity of Silver Nanoparticles after 90-day Silver Nanoparticle Inhalation Exposure. Saf. Heal. Work. 2011, 2, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Espino, D.I.; Zamora-Perez, A.L.; Zúñiga-González, G.M.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, R.; Morales-Velazquez, G.; Lazalde-Ramos, B.P. Genotoxic and cytotoxic evaluation of Jatropha dioica Sessé ex Cerv. by the micronucleus test in mouse peripheral blood. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 86, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, R.O.; Froseth, J.A.; Coon, C.N. Protein Utilization and Toxic Effects of Raw Beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris) for Young Pigs2. J. Anim. Sci. 1982, 55, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A.E.; Reaidi, G.B. Toxicity of Kidney Beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris) With Particular Reference to Lectins. J. Plant Foods 1982, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, A.K.; Das, M.; Jain, S.; Dwivedi, P.D. Clinical complications of kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) consumption. Nutrition 2013, 29, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nciri, N.; Cho, N.; Bergaoui, N.; El Mhamdi, F.; Ben Ammar, A.; Trabelsi, N.; Zekri, S.; Guémira, F.; Ben Mansour, A.; Sassi, F.H.; et al. Effect of White Kidney Beans (Phaseolus vulgarisL. var. Beldia) on Small Intestine Morphology and Function in Wistar Rats. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 1387–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nciri, N.; Cho, N.; El Mhamdi, F.; Ben Ismail, H.; Ben Mansour, A.; Sassi, F.H.; Ben Aissa-Fennira, F. Toxicity Assessment of Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgarisL.) Widely Consumed by Tunisian Population. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Vital, D.A.; de Mejía, E.G.; Loarca-Piña, G. Dietary Peptides from Phaseolus vulgaris L. Reduced AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colon Carcinogenesis in Balb/c Mice. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nciri, N.; Cho, N. New research highlights: Impact of chronic ingestion of white kidney beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L. var. Beldia) on small-intestinal disaccharidase activity in Wistar rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Cytotoxicity evaluation of the whole protein extract from Bar-transgenic rice on Mus musculus lymphocytes. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idouraine, A.; Sathe, S.K.; Weber, C.W. Biological evaluation of flour and protein extract of tepary bean (Phaseolus acutifolius). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 1856–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambre M.; Montagu M Van.; Angenon G.; Terryn N. Tepary Beans (Phaseolus acutifolius). Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;343:407–14.

- Osman, M.A.; Reis, P.M.; Weber, C.W. The Effect of Feeding Tepary Bean (Phaseolus acutifolius) Proteinase Inhibitors on the Growth and Pancreas of Young Mice. Pak.J. Nutr. 2003;2(3):111–5. https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=pjn.2003.111.

- Sharon, N. Lectins: past, present and future1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008, 36, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme E.J.M; Rouge P, Peumans W.J. 3.26 plant lectins. In 2007. p. 563–99.

- Wati, R.K.; Theppakorn, T.; Benjakul, S.; Rawdkuen, S. Trypsin Inhibitor from 3 Legume Seeds: Fractionation and Proteolytic Inhibition Study. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C223–C228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheina-Martins, G.V.; da Silveira, A.L.; Ramos, M.V.; Marques-Santos, L.F.; Araujo, D.A.M. Influence of fetal bovine serum on cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of lectins in MCF-7 cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2011, 25, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Shi, J.; Kakuda, Y.; Kim, D.; Xue, S.J.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, Y. Phytohemagglutinin isolectins extracted and purified from red kidney beans and its cytotoxicity on human H9 lymphoma cell line. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Wong, J.H.; Lin, P.; Chan, Y.S.; Ng, T.B. Purification and Characterization of a Lectin from the Indian Cultivar of French Bean Seeds. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010, 17, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Singh, G.; Mahajan, V.; Gupta, H.S. Variability of Nutritional and Cooking Quality in Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L) as a Function of Genotype. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2009, 64, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.A. Ynalves L.M.F.; C.V Sanchez. Comparison and Temperature Study of Lectin Activities in Texas Live Oak (Quercus fusiformis) Crude Extract. J Plant Sci. 2011;6(3):124–34. https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=jps.2011.124.

- Shi, L.; Mu, K.; Arntfield, S.D.; Nickerson, M.T. Changes in levels of enzyme inhibitors during soaking and cooking for pulses available in Canada. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, I.; Wafula, E.; Sila, D.; Kyomugasho, C.; Grauwet, T.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Thermal treatment of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): Factors determining cooking time and its consequences for sensory and nutritional quality. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3690–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.; Bautista, M.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A.; González-Amaro, R.M.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Morales-González, J.A.; González-Cruz, L. Effects of Germination and Popping on the Anti-Nutritional Compounds and the Digestibility of Amaranthus hypochondriacus Seeds. Foods 2022, 11, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterborg, J.H.; Matthews, H.R. Method for Quantitation. Protein Protocols Handbook. 1984;1(173):7–9. [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Villagómez-Ibarra, J.R. Partial Characterization of Lectins Purified from the Surco and Vara (Furrow and Rod) Varieties of Black Phaseolus vulgaris. Molecules 2022, 27, 8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorke, D. A new approach to practical acute toxicity testing. Arch. Toxicol. 1983, 54, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Álvarez-González, I.; Márquez-Márquez, R.; Velázquez-Guadarrama, N.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E. Inhibitory Effect of Mannan on the Toxicity Produced in Mice Fed Aflatoxin B1 Contaminated Corn. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 53, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lectins (HAU/mg) | Tripsin Inhibitors (TIU/mg) | Taninns (mg eq Cat/g) | Saponins (HU/mg) |

| 2701.85±0.0 | 6.86±0.55 | 0.1757±0.0002 | 20.16±0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).