Introduction

Tapirira guianensis, a non-endemic tree belonging to the Anacardiaceae family and the genus Tapirira, also known in Brazil as ‘pau-pombo’ or ‘peito-de-pombo’, is from the Amazon rainforest and present in humid soils [

1]. This fruit has been traditionally used for its medicinal properties and economic importance, even though its chemical and biological potential remains underexplored [

2]. Indeed, few studies have identified the presence of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, carotenoids, anthocyanins, and other bioactive metabolites in

T. guianensis bark and seed extracts, and juice, suggesting its potential as a source of antioxidant, and antimalarial chemical entities [

2,

3,

4]. None of these studies reported the cytotoxic effects of

T. guianensis seed extracts on normal and cancerous cells or the antioxidant protection of human red blood cells (erythrocytes).

Oxidative stress, driven by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant defenses, is a critical factor in the pathogenesis of these chronic diseases [

5,

6]. The growing global health burden of oxidative stress-related disorders, and infectious diseases such as malaria, and cancer remain leading causes of morbidity and mortality, driving the need for novel therapeutic strategies [

7]. Malaria remains an urgent public health challenge, with approximately 241 million cases and over 600,000 deaths reported annually, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa [

8]. The emergence of drug-resistant strains of

Plasmodium falciparum has significantly undermined the efficacy of existing antimalarial therapies, highlighting the need for new targeted chemical compounds [

9,

10]. Historically plants have served as a source of antimalarial drugs, exemplified by quinine and artemisinin, derived from traditional medicine [

11].

In this sense, natural products, particularly those rich in phenolic compounds, have gained attention for mitigating oxidative damage and modulating key biological pathways, offering safer and potentially more effective alternatives to synthetic drugs [

12]. The cultivation of

T. guianensis remains relatively limited at present; however, its potential applications, including the development of colorless cosmetics and dietary supplements, present promising opportunities for future advancements [

2].

Given the pressing need for new natural sources of bioactive compounds to combat or prevent diseases such as malaria and cancer, and explore the socioeconomic and functional potential of T. guianensis mostly using different fruit by-products, this study aimed to explore the chemical composition of T. guianensis seed extracts using advanced analytical techniques such as UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. By building on existing knowledge of the plant's bioactive compounds, we sought to evaluate its potential as a source of therapeutic agents, contributing to the search for innovative and effective treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents and Cell Lines

Sobutanol, and ascorbic acid (Vetec, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), ethanol, sodium hydroxide, aluminum chloride hexahydrate, vanillin (Dinâmica, Indaiatuba, Brazil), Folin-Ciocalteu (Biotec, Curitiba, Brazil), ferric chloride hexahydrate, 2,4,6-tripyridyl-1,3,4-triazine (TPTZ), quercetin, gallic acid, (+)-catechin, chlorogenic acid, sodium nitrite, 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrilhidrazyl (DPPH), (Sigma Aldrich, São Paulo, Brazil), 98% sulfuric acid, 37% hydrochloric acid (Fmaia, Indaiatuba, Brazil), iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate, hydrogen peroxide (Synth, Diadema, Brazil), anhydrous sodium acetate (Anidrol, São Paulo, Brazil) and Sodium molybdate (Reatec, Colombo, Brazil). HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, and Formic acid were acquired from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Leucine enkephalin reference solution was purchased from Waters Co (Manchester, UK). Other reagents and solvents were of analytical grade and commercially available. Albumax I, RPMI-1640, and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (DMEM) were acquired from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). 2',7'-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), penicillin, Triton X-100, SYBER Gold (S11494), EDTA (disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate), were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (São Paulo, Brazil).

HCT-8 (human colon carcinoma cells), A549 (lung adenocarcinoma cell line), and HUVEC (normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells) cell lines were obtained from Rio de Janeiro Cell Bank (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

2.2. Plant Source and Ultrasound-Assisted Solvent Extraction

The fruits of

T. guianensis were collected from the Manaquiri region (BR319, Km 150) in the Brazilian state of Amazonas, on 14 December 2022. For sample preparation, the fruits were cleaned with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution and the seeds were separated from the fruits for subsequent freeze-drying, resulting in 45 g of sample mass. The bioactive compounds were extracted from the seeds by ultrasound-assisted solvent extraction using a sonicator at 40 Hz and 70 W for 30 min (room temperature) [

13]. For each extract, 10 g of dried samples were weighed and processed in a solvent ratio of 1:10 (m/v), in triplicate. To higher yield, the extraction process was repeated twice, and hydroethanolic, with 50% (HE50) and 80% (HE80) of ethanol, aqueous (AE100), and ethanolic (EE100) extracts were obtained. The extracts were dried and stored at -20 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Chemical Profile and Antioxidant Capacity

2.3.1. Phenolic Compounds

The total phenolic content (TPC) of

T. guianensis seed extracts was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay, and results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent per gram of sample (mg GAE/g). Different dilutions of

T. guianensis seed extracts were added to a 96-well plate (25 µL/well), followed by 200 µL of distilled water and 25 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1:3, v/v). After 5 minutes, 25 µL of 10% sodium carbonate was added, and the absorbance was measured at 725 nm after 1h reaction. A calibration curve (10-80 mg/L, R² = 0.998) was created using gallic acid to compare the absorbance values [

14].

The total flavonoid content (TFC) of extracts was estimated using the colorimetric method based on the complexation of aluminum with flavonoids and the results were expressed as mg of catechin equivalent per g of extract (mg CE/g). Using quercetin as the standard, the total flavonols content was quantified, and the results were expressed as mg of quercetin equivalent per g of extract (mg QE/g). The

ortho-diphenols were measured using a colorimetric method based on the formation of a metallic complex between sodium molybdate dihydrate and

ortho-diphenols. The results were expressed as mg of chlorogenic acid equivalent per g of extract (mg CAE/g) [

15,

16].

2.3.2. Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-QToF/MS) Analyses

The dry extracts (EE100, HE50, HE80, and AE100) were dissolved in methanol and filtered through a PVDF membrane (13 mm × 0.22 μm, WHATMAN) to a chromatographic vial (1.5 mL). Filtered samples were sonicated to remove air bubbles for analysis using HPLC and UPLC-QToF/MS analyses. The analyses were performed on a Waters Xevo® G2-XS QTof mass spectrometer (Waters Co. Manchester, UK) coupled to an Acquity HClass UPLC and monitored with MassLynx® software (v. 4.1). Separation of the metabolites was achieved on an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 with reverse phase column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d, 1.7 μm particle size) at 40°C (± 2 °C) and eluted with a gradient system of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, using the following linear gradient elution program (A:B, in %: 0–15 min (98:2), 15–20 min (80:20), 20–25 min (60:40), 25–27 min (2:98) 27–27.10 min (98:2), 27.10–30 (98:2). The injection volume was 10 μL. The analyses were performed on a Waters Xevo® G2-XS QTof mass spectrometer (Waters Co. Manchester, UK) coupled to an Acquity HClass UPLC and monitored with MassLynx® software (v. 4.1).

Separation of the metabolites was achieved on an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 with reverse phase column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d, 1.7 μm particle size) at 40°C (± 2 °C) and eluted with a gradient system of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, using the following linear gradient elution program (A:B, in %: 0–15 min (98:2), 15–20 min (80:20), 20–25 min (60:40), 25–27 min (2:98) 27–27.10 min (98:2), 27.10–30 (98:2). The injection volume was 10 μL. The nebulization process operated in negative mode, with a mass range between 100 and 1500 amu, and a scan time of 0.2 s. The ESI source parameters were capillary voltage of 3.0 kV, desolvation temperature of 250 °C; source temperature of 100 °C; cone voltage of 30 V; and cone gas flow of 50 L/h. The desolvation gas flow for negative polarity is 700 L/h. Both low (MS1, 6 eV) and high (MS2, ramped from 20 to 35 eV) collision energy data were recorded by employing MSE continuum mode, acquisition time 0 to 30 min and mass correction during acquisition by an external reference (LockSprayTM), Leucine enkephalin (m/z 554.2615 [M-H]- and 556.2771 [M+H]+) was used as the lock mass calibrant [

17,

18].

2.3.3. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Analysis

The dry extract (5 mg) was dissolved in 530 μL of CD3OD containing TMS (≥ 99.0% purity) as the internal reference (0.0 ppm). This solution was transferred to a 5 mm NMR tube. NMR analyses (1H, 13C, DEPT135, 1H-1H COSY, HSQC and HMBC) were performed on a 11.7 T spectrometer (Bruker® Avance III HD 500.13 MHz for 1H and 125.8 MHz for 13C, BBFO Plus SmartProbeTM, New York, NY, USA) at 298 K [

17,

18].

2.3.4. Chemical Antioxidant Capacity

The antioxidant activity of

T. guianensis seed extracts was evaluated using the following assays: The free-radical scavenging activity against the DPPH radical and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (HRSA) were assessed following the method proposed by Mohammadi et al. [

19]. Results were expressed as milligrams of ascorbic acid equivalent per gram (mg AAE/g DM) and mg of gallic acid equivalent per gram (mg GAE/g DM), respectively. The ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of the extracts was quantified according to Granato et al. [

16], with data expressed as mg of ascorbic acid equivalent per gram of extract (AAE/g DM).

2.3.5. Protection Against Lipoperoxidation

Thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS) method was used to evaluate the lipoperoxidation levels in egg yolk, with oxidative stress induced by FeSO

4 4 mmol/L solution at 37 ºC for 45 min, following the proposed by Fidelis et al. [

20]. The samples were tested at 50 to 250 µg/mL, and the lipoperoxidation inhibition capacity was according to the following equation,

where A

Sample was the absorbance at λ = 532 nm of the samples and A

Control was the absorbance at λ = 532 nm of the control. All the results were compared with the efficacy of quercetin (5 µg/mL).

2.4. Cell Culture: Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant Activity

2.4.1. Cell Viability Assessment

The cytotoxicity of the

T. guianensis seed extracts was evaluated on HCT8, A549, and HUVEC cell lines. The cells were cultured in Ham-F12 medium, supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 100 μg/mL of penicillin. The cytotoxic activity of samples was observed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay [

14]. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 1 × 10

4 cells/well (HCT8 and A549) and 6 × 10

3 (HUVEC), 100 μL/well. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO

2 for cell adhesion. After that, the cells were treated with serial concentrations of 10 to 300 μg GAE/mL of extracts and incubated for 48 h. Following the treatment, 10 μL of MTT reagent (0.5 mg /mL) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The formazan crystals were dissolved with 100 μL of DMSO. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm and the 50% cell viability inhibition (IC

50) was calculated, following the equation:

where, T = number of cells after 48 h treatment; C = control cells at 48 h. The Selectivity Index (SI) value was calculated by SI = IC

50 normal cells/IC

50 tumor cells.

2.4.2. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was assessed using the DCFH-DA (2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate) assay [

16]. Normal (HUVEC) and cancer (A549 and HCT8) cells were placed in a 96-well plate (5 × 10⁴ cells/well) and treated with different concentrations of

T. guianensis seed extracts (10, 25, 50 μg GAE/mL), which were diluted in DCFH-DA solution (25 mmol/L). The cells were only treated with culture medium for the negative control, and for the positive control, the cells were treated with 15 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in the dark. Following the treatment, the plates were washed with PBS, and a HANKS solution with H₂O₂ (15 μmol/L) was added to the wells. The fluorescence intensity (λ emission = 538 nm and λ excitation = 485 nm) was measured, and the data was expressed as the percentage of fluorescence intensity relative to the negative control group.

2.4.3. Protection Against Chromosomal Aberration

The

in vitro chromosomal aberration test is used to evaluate the protection or genotoxic effect of substances. The selection of the cell line should mainly concern the culture's growth ability. A549 cell line and the highest dosages of 50% hydroethanolic extract of

T. guianensis seed extract were used, based on the results of cytotoxicity assay. The cells were seeded in 25 cm

2 flasks at 5 × 10

5 cells/flask. The positive control was treated with 4 μM cisplatin, a drug that induces chromosomal aberrations, and the negative control received culture medium [

21]. The treatment groups received different concentrations of HE50 (5, 10, and 20 μg GAE/mL) in combination with cisplatin (4 μM). Two treatments were prepared to investigate whether the sample can generate genotoxicity independently (20 μg GAE/mL and 50 μg GAE/mL). The flasks were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, 200 μL of colchicine solution (0.0016%) was added to each group for 6 h, and slides were prepared after fixation and staining of the material. For the analysis, the chromosomal breakage criteria were used, and the chromosomal aberration rate (%) was calculated as the percentage of chromosome breaks observed per total chromosome.

2.4.4. Erythrocyte Cellular Antioxidant Activity and Protection

To access the interaction of

T. guianensis and human erythrocytes, the oxidation was induced by 2,2'-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH), and hemolysis and intracellular ROS generation were evaluated, according to described by Cruz et al. [

22]. First, fresh blood (O

+) was obtained from a female volunteer and collected in heparinized tubes after the informed consent form was assigned (Federal University of Alfenas - Ethics approval n° 6.910.474). The blood was washed with PBS until reached 20% hematocrit and mixed with

T. guianensis seeds extracts (5 to 30 µg GAE/mL) or PBS (negative control) for 20 minutes of incubation (37 ºC, 100 RPM). Then, AAPH (200 mmol/L) was added, allowed to react for 2 h (37 °C, 100 RPM) to complete the oxidation, and centrifuged at 1200 RPM for 10 min.

The hemolysis rate (%) was accessed using 100 µL of supernatant, mixed with 200 µL of PBS in a 96-well microplate, and recorded at 523 nm in a microplate reader. Regarding intracellular ROS generation, 400 µL of DCFH-DA solution (10 µmol/L) was mixed with the precipitate, incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in the dark, and transferred to a 96-well microplate to determine the fluorescence intensity at 485 and 520 nm for excitation and emission, respectively.

2.5. In Vitro Antimalarial Properties

The

in vitro antimalarial effect of

T. guianensis seed extracts was evaluated against W2 (chloroquine-resistant) and 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) strains.

P. falciparum strains were cultivated in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 10% Albumax II and 4% hematocrit. The plates were incubated at 37 °C using the candle jar method [

23]. The culture medium was replaced three times a week, and parasitemia was monitored using Panoptic fast-stained smears. Parasite synchronization at ring stages was performed with a 5% (w/v) D-sorbitol solution [

24].

To perform the assay, the parasites were diluted to a solution with 1% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit and incubated on 96-well plates with different concentrations of

T. guianensis seed extracts (0.2 to 12 μg GAE/mL) or with culture medium as a positive control. A 2% hematocrit solution was used as the negative control. After 48 h, 100 μL of parasite culture was added to a 96-well cell plate containing 100 μL of SYBR Gold at 1/10,000 (v/v) in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 5 mM EDTA; 0.008% saponin (w/v); 0.08% Triton X-100 (v/v)]. The microplates were read using a microplate reader (excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm). The selective index (SI) was calculated by the ratio between the IC

50 normal cell (HUVEC) and the IC

50 of each

P. falciparum strain (3D7 and W2) [

25].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were performed in quadruplicate with results expressed as average ± SD. The dose-response analysis was determined by nonlinear regression (curve fit). The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey was performed to investigate the differences among groups. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism® software (version 8.0, USA). Results with a p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Profile

Analyzing our samples, we found that the TPC of the seed extracts varied between 14 and 53 mg GAE/g DM, and the equivolumetric mixture obtained with a water-ethanol extract (HE50) exhibited the greatest phenolic content (

Table 1). The result of phenolic content is similar for mango seed extracts obtained by ultrasound extraction (varied from 31.2 to 121.66 ± 18 mg GAE/g DM) with the highest value related to a mixture of ethanol and water [

26]. Interestingly, the lower content of phenolics is relative to the ethanolic extraction, and the same behavior is observed in flavonoid content (

Table 1), where the ethanolic extract (EE100) presented the lowest content of TFC (32 ± 4 mg CE/g DM) compared to the hydroethanolic extract (HE50, 158 ± 11 mg CE/g DM).

Regarding the total flavonols content (4-16 mg QE/g DM), there was no difference between the amounts presented by EE100, AE100, and HE80 extracts, while HE50 exhibited a greater content. It was also noted in the

ortho-diphenols quantification, that as much as HE50 (33 mg CAE/g DM) showed a greater content than the others (7-15 mg CAE/g DM). These findings align with studies on hydroethanolic mixtures as optimal solvents for extracting phenolic compounds [

21,

27]. Castañeda-Valbuena et al. [

26] suggest that the lower the concentration of ethanol (<80%), the higher the content of polyphenols in the samples, confirming our findings.

Overall, parameters such as the temperature, solvent, contact area, time, molecular structure of the matrix, and the part of the plant used, affect the phenolic content in extraction [

21]. Generally, hydroethanolic mixtures improve the efficiency of compounds' extraction playing a fundamental role in their solubilization, due to the ability of water to cause a swelling of the raw material facilitating the entry of ethanol into the cell. In contrast, protic ethanol lowers the polarity and enhances the solubilization of polyphenolic compounds, improving the extraction efficiency yields of hydrophilic and hydrophobic phenolics [

26,

28].

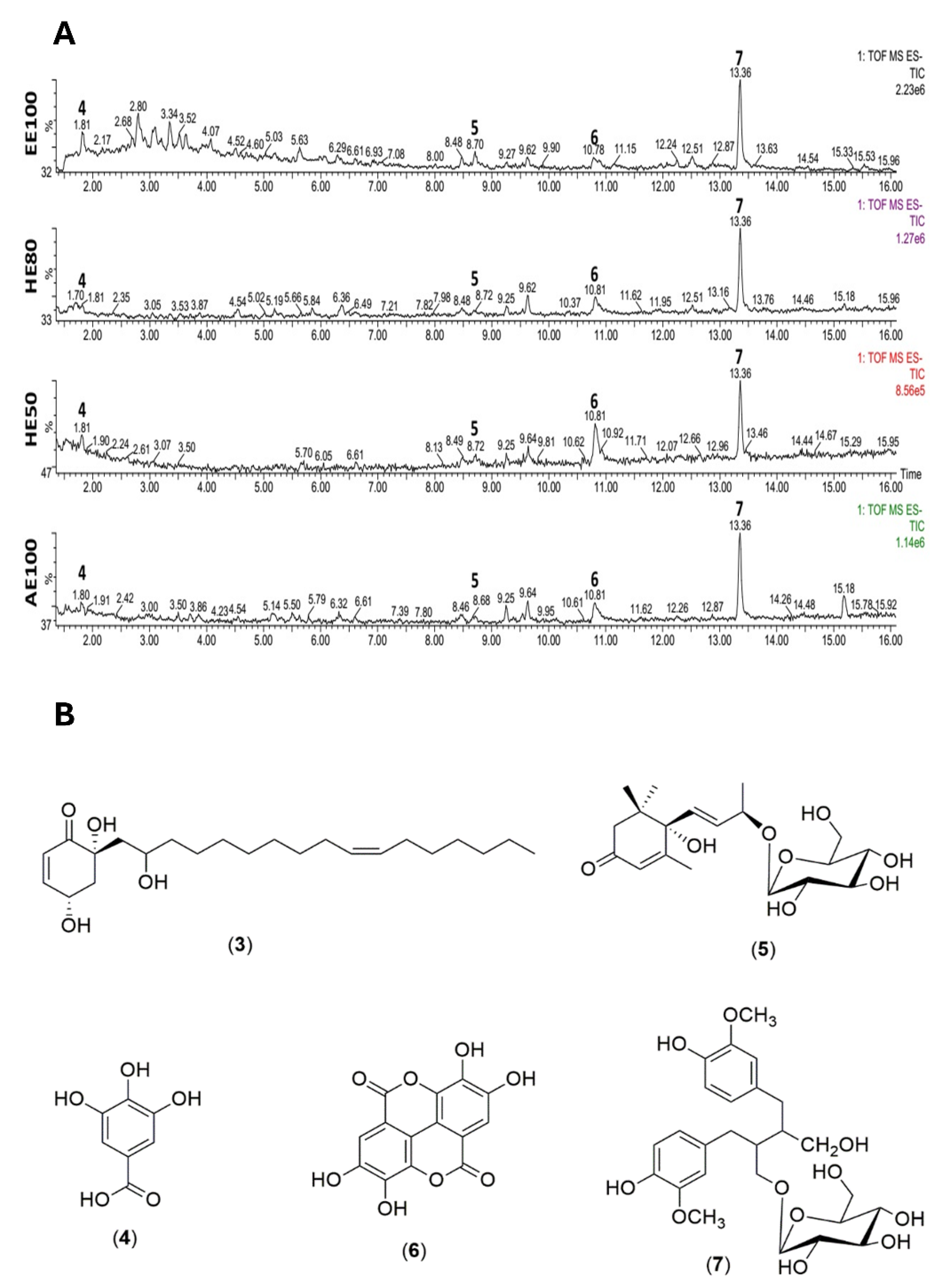

The chemical composition of the

T. guianensis seed extract was further explored using the UPLC-QTOF/MS system for the determination of qualitative differences in composition between the four extracts.

Figure 1A presents the similarity among the chromatographic profile of extracts, where a peak at 13.36 min is identified in all samples as the majority one, followed by a peak at 12.82 min. The identification of the constituents was confirmed based on 1D and 2D NMR data in comparison with literature data (

Table 2).

Additionally, compound (

4), proposed as Gallic Acid, RT at 1.8 min, exhibited a [M-H]

- ion at

m/z 169 and, upon fragmentation (MS

2), an intense [M-H-CO

2]¯ ion at

m/z 125 due to the loss of a carbon dioxide moiety. Compound (

5), showed ion at

m/z 431 relative to a [M+Formic Acid-H]

- adduct, a fragmentation at m/z 223 due to the loss of hexose moiety, [M-H-162]¯ ion and

m/z 205 concerned to [M-H-162-18]¯ ion, with loss of water molecules. Compound (

6), suggested as Ellagic acid, C

14H

5O

8, eluted at 10.8 min, presented a [M-H]

- ion at m/z 300.99. The fragments (MS

2) were m/z 283 ([M−H−OH]

−), 229 ([M−H−CO

2−CO]

−), and 185 ([M−H−2CO

2−CO]

−). The observed fragmentation was similar to the reported by Ma et al. [

29]. Compound (

7), eluted at 13.3 min, presented

m/z 523 (100% intensity, [M−H]

– ion),

m/z 361.1647 ([M−glucose−H]

− ion) are consistent with the literature values previously reported for secoisolariciresinol monoglucoside (SMG) [

30]. In addition, 1D and 2D NMR analyses allowed the detection of signals consistent with carbohydrates α- e β-Glucose (

1,

2), 4,6,2’-trihydroxi-6-[10’(Z)-heptadecenyl]-1-cyclohexene-2-one (

3), Gallic acid (

4), (6

S,7

E,9

S)-6,9-dihydroxy-megastigma-4,7-dien-3-one 9-O-β-glucopyranoside (

5), Ellagic acid (

6) e (−)-Secoisolariciresinol-9’-

O-β-

d-glucopyranoside (

7) (

Figure 1B and

Table 2).

In the analysis of the ¹H NMR spectral profile, higher signal intensities were observed at δ 7.53 (s) and δ 6.63 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), corresponding to constituents

(6) and

(7), respectively. This result corroborates the findings of the LC analysis, which identified these as major constituents. Furthermore, compounds

(3),

(4),

(5), and

(6) have been previously reported in extracts of

T. guianensis [

4,

31,

32]. This is the first report of the identification of

(7) in this species.

3.2. Chemical Antioxidant Capacity

In the current research, the antioxidant capacity of the four extracts was assessed using the following assays: DPPH, FRAP, and Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, as shown in

Table 1. Regarding the DPPH scavenging antioxidant potential, the results indicate that AE100 (119 mg AAE/g DM) exhibited better activity, followed by HE50 (103 mg AAE/g DM). Similar behavior was observed in the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, in which the aqueous extract (53 mg GAE/g) was notably higher than other extracts.

HE50 and HE80 showed FRAP greater than EE100 and AE100, also indicating the role of an equivolumetric mixture of solvents in facilitating the extraction of bioactive compounds, as mentioned before. These results are comparable to the obtained by Do Carmo et al. [

21] for

Myrciaria dubia (Camu-Camu) seed extracts, who also demonstrated a greater activity in hydroethanolic extracts than ethanolic and aqueous. Moreover, HE50 and HE80 presented the greatest TPC, TFC, flavonols, and

ortho-diphenols content, compounds that are known to have antioxidant capacity [

19].

The FRAP assay operates primarily through an electron transfer mechanism, measuring the ability of antioxidants to reduce ferric (Fe³⁺) to ferrous (Fe²⁺) ions. The hydroxyl radical scavenging assay, on the other hand, evaluates the capacity of antioxidants to neutralize hydroxyl radicals (•OH) via proton transfer, a critical mechanism for mitigating oxidative damage caused by ROS. In contrast, the DPPH assay is versatile, as it can measure antioxidant activity through both mechanisms, depending on the chemical structure of the bioactive compounds present in the sample [

33]. Herein, the aqueous extract demonstrated superior performance in the DPPH and hydroxyl radical assays, likely due to its content of hydrophilic antioxidants such as phenolic acids (ellagic acid and gallic acid) which excel in these specific mechanisms. Conversely, HE50 showed greater efficacy in the FRAP assay, suggesting it contains bioactive compounds with strong electron-donating capacities, possibly due to the presence of moderately polar phenolic compounds.

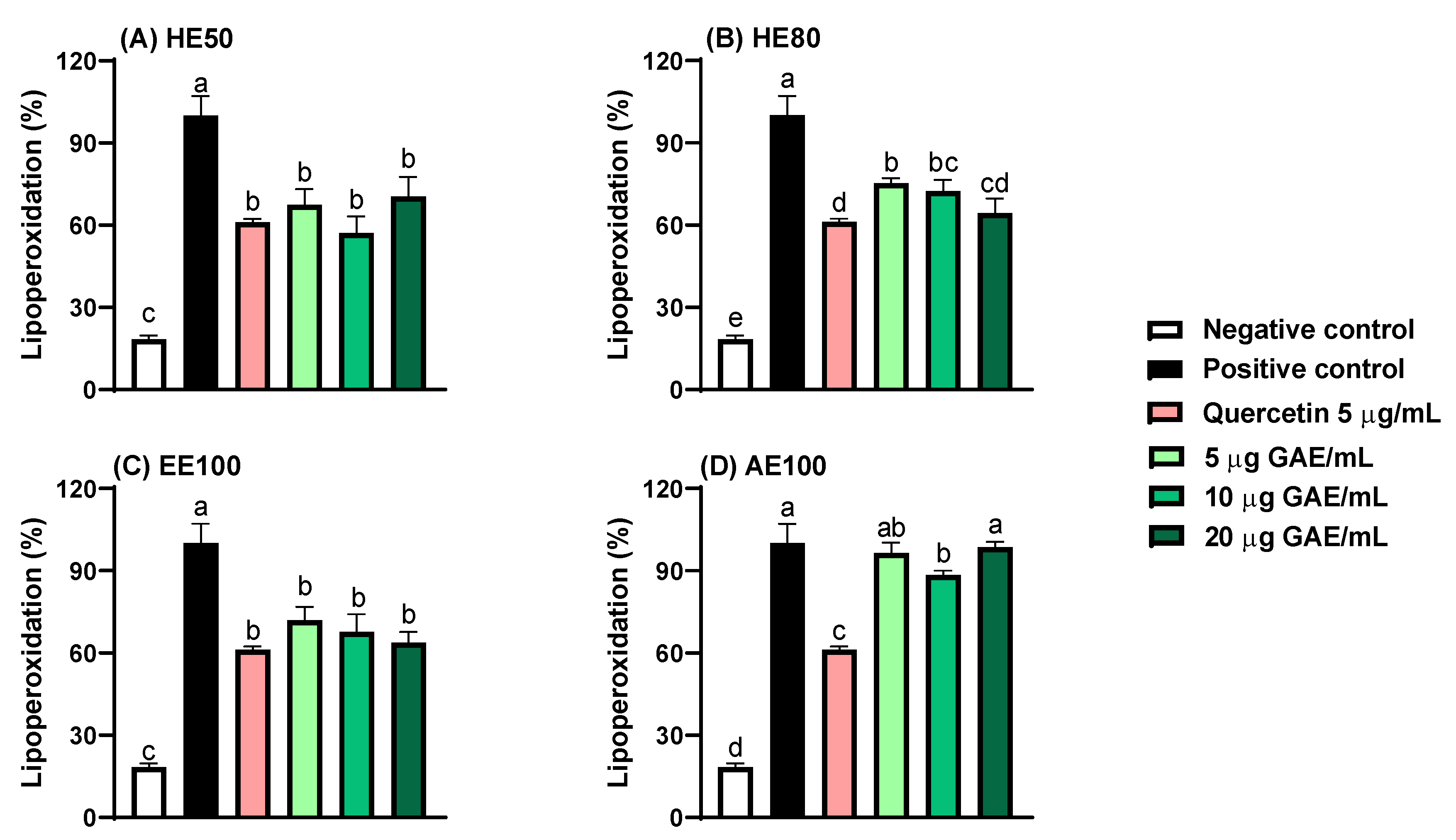

3.2. Protection Against Lipoperoxidation

The lipoperoxidation rates were diminished by HE50, HE80, and EE100 at every tested concentration (5, 10, and 20 μg GAE/mL) (

Figure 2). While HE50 and EE100 protected the lipids at the three tested concentrations with the same efficiency as quercetin, HE80 only equated with the standard effectiveness at 20 μg GAE/mL. Curiously, AE100 only effectively reduced the lipoperoxidation rate when concentrated at 10 μg GAE/mL, despite being less efficient than the other samples. It may occur due to the sample polarity, since extracts obtained with ethanol-rich solvents usually present compounds with adequate interaction with the lipids in order to protect them from oxidative stress, whilst the high polarity of the aqueous extract may prevent it from reducing the lipoperoxidation rate [

27]. Formerly, camu-camu (

Myrciaria dubia) hydroethanolic seed extracts were reported to inhibit 24-86% of lipoperoxidation [

15], while jabuticaba (

M. cauliflora) seed-optimized extracts constrained 71-86% of lipid peroxidation [

20], confirming the results found.

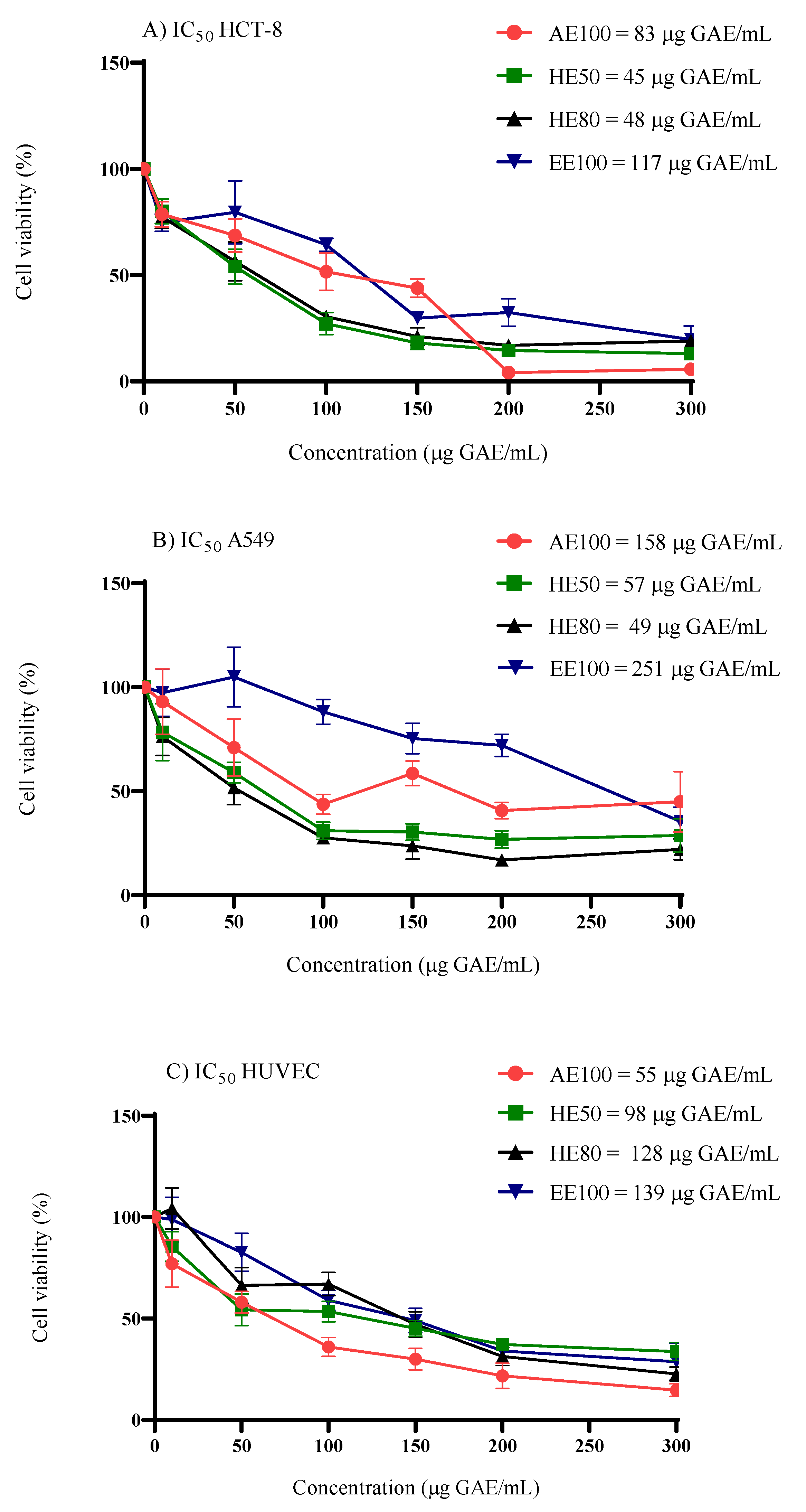

3.3. Cytotoxicity Activity in Cell Culture

The relative cytotoxic potential of

T. guianensis seed extracts was evaluated in non-cancerous cells (HUVEC) and compared to cancer cells (A549 and HCT-8). The results indicated that all extracts exhibited cytotoxic activity against the tested cell lines (

Figure 3). Among the cancer cell lines tested, A549 cells exhibited the greatest resistance to EE100 and AE100, with IC₅₀ values of 251 and 158 μg GAE/mL, respectively. These values are approximately twice as high as those observed in HCT-8 cells (IC₅₀ = 117 and 83 μg GAE/mL). Similar behavior was observed in a study where potent activity was found in the extract of the inner bark of

T. guianensis against CACO-2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma), PANC-1 (carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas) and CALU-6 (lung adenocarcinoma) cells, with lower sensitivity in A549 cells [

34]. Considering that the SI value higher than 3 [

16] indicates selectivity of the extract to the cancer cells, the

T. guianensis samples had no selectivity over cancer cells once the SI values ranged from 0.3 to 2.7 (

Table 3).

Among the samples, the 50% and 80% hydroethanolic extracts of

T. guianensis exhibited the greatest sensitivity towards cancer cells. Supporting our findings, Silva-Oliveira et al. [

35] reported that the hydroethanolic fraction of the

T. guianensis leaf extract displayed greater cytotoxic activity against three head and neck cancer cell lines compared to other fractions.

Interestingly, a similar pattern was observed in a study on camu-camu (

Myrciaria dubia) seeds, where a 50% hydroethanolic extract demonstrated high cytotoxicity and selectivity against A549 cells [

21]. Overall, the polarity of the solvents is particularly critical, as it significantly determines the compositional profile and antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds. Solvents with medium and low polarities can extract compounds with a greater ability to permeate cell membranes and exert effects on cells [

28,

36]. This may explain the differing cytotoxicity results observed between the extracts.

According to the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), which classifies potential antiproliferative agents based on cytotoxic activity, the extract of

T. guianensis seeds can be classified as moderately active (IC

50 = 21–200 μg/mL), except for EE100 (A549), which is classified as weakly active (IC

50 = 201–500 μg/mL) [

14]. The presence of gallic acid and ellagic acid in all seed extracts of

T. guianensis may account for the observed cytotoxicity against the evaluated cell lines. Studies suggest that ellagic acid inhibits the phosphorylation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway, triggering cell apoptosis through increased levels of p21, Bax, cytochrome c, caspase-3, and caspase-9, as well as decreased levels of Bcl-2 and cyclin D1 in A549 cells [

37,

38]. Similarly, gallic acid has been reported to suppress the PI3K/Akt pathway and promote apoptosis by upregulating pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and caspase-3 [

39]. Together, these findings suggest that both ellagic and gallic acids exert cytotoxic effects by targeting key signaling pathways involved in cell survival and apoptosis, as primarily observed with HE50 and HE80 in A549 cells.

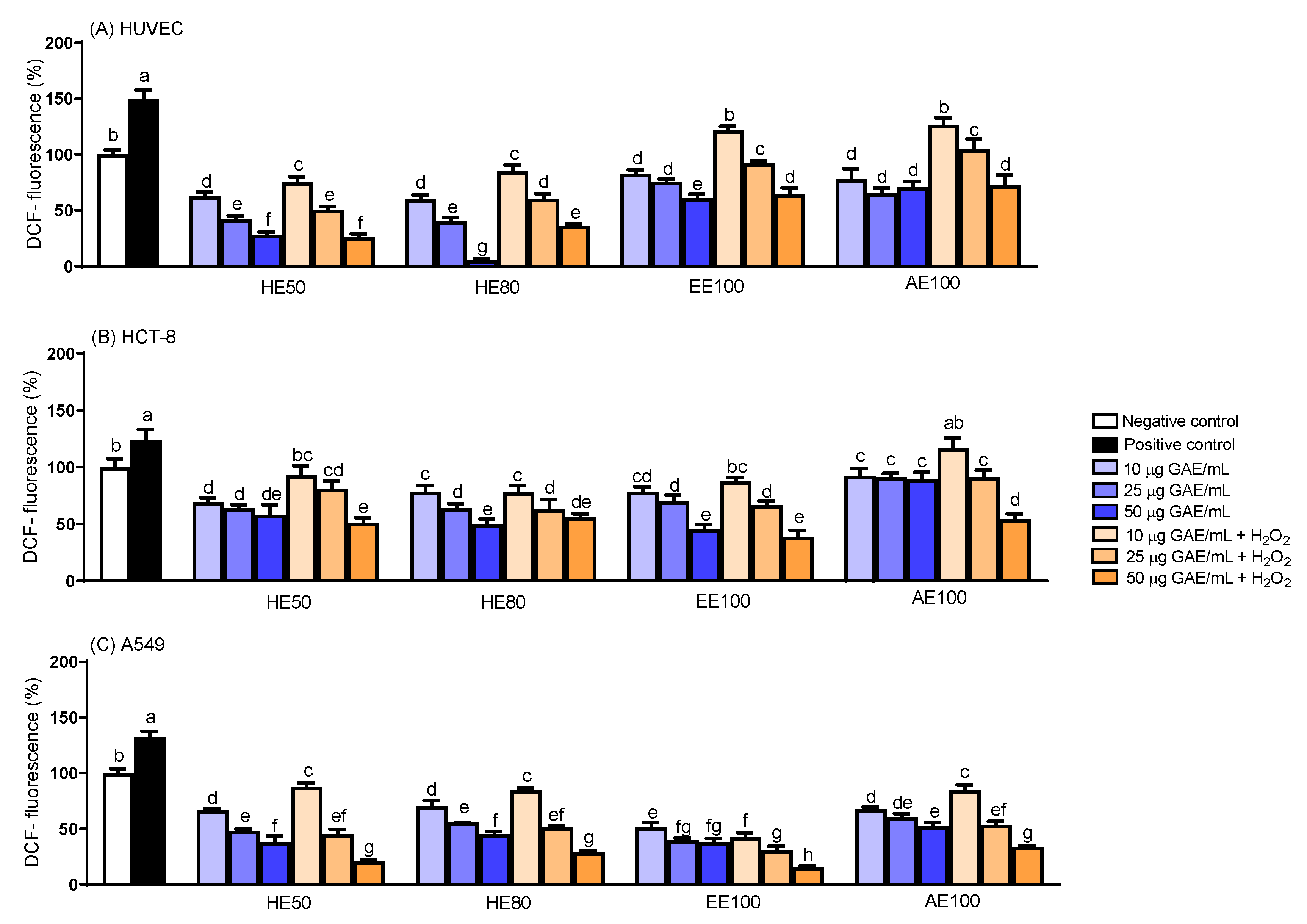

3.4. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

In this study, DCFH-DA was used to assess the ROS produced in cell lines exposed to various concentrations (10, 25, and 50 μg GAE/mL) of

T. guianensis seed extracts. In the presence of H

2O

2, our results showed that all the extracts decreased ROS generation in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating cytoprotective activity in cancer and non-cancer cells (

Figure 4). Interestingly, our extracts reduced basal ROS production in non-cancerous cells (HUVEC) under treatments without H₂O₂, particularly HE50, and HE80 at a concentration of 50 μg GAE/mL, which decreased ROS levels by 70% and 95%, respectively. Although the pronounced reduction in ROS could lead to disruption of cell signaling, resulting in the loss of homeostasis control in normal cells [

12], herein no detectable effect on cell proliferation was observed at these concentrations, suggesting that the observed ROS reduction is likely a localized antioxidant activity.

The ROS assay showed that HE80 and EE100, at a concentration of 50 μg GAE/mL without H₂O₂, reduced ROS production in A549 cells by 55% and 58%, respectively. However, despite the similar reduction in ROS, A549 cells exhibited greater sensitivity to the HE80 extract in terms of cell viability. Thus, our results suggest that the concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation, as observed in the cell viability test, may involve mechanisms unrelated to ROS generation, as discussed in section 3.2. Similar behavior was observed in studies with

Vitis vinifera and

Myrciaria dubia seed extracts, where the cytotoxic effects in cancer cells did not correlate with ROS reduction [

21,

40].

The mitigation of oxidative stress reduction observed in the cells, both with and without H₂O₂ induction, is closely associated with the phenolic compounds present in T. guianensis seed extracts. This antioxidative effect can be particularly linked to SMG (Secoisolariciresinol-9´-O-β-D-glucopyranoside), a diphenolic nonsteroidal phytoestrogen belonging to the lignan family [

41], which has been identified as the predominant compound in all

T. guianensis extracts (HE50, HE80, EE100, AE100). The antioxidant properties of SMG are attributed to the presence of hydroxyl groups in the para positions of its phenolic rings [

42], underscoring its potential as a key compound for further investigation into antioxidant-related benefits.

Overall, an antioxidant effect was observed on cancer and non-cancer cell lines evaluated. Under physiological conditions, ROS are produced during a wide variety of cellular processes and play vital roles in stimulating signaling pathways, such as intracellular signal transduction, metabolism, proliferation, and apoptosis in normal cells and also play an important role in immune system regulation and maintenance of the redox balance [

43,

44]. On the other hand, when there is an imbalance between antioxidants and oxidants, high concentrations of ROS can cause DNA mutations and induce malignant cell transformation. [

45,

46]. Thus, evaluating the antioxidant potential of

T. guianensis seed extracts highlights their potential protective effects against oxidative damage in all evaluated cell lines.

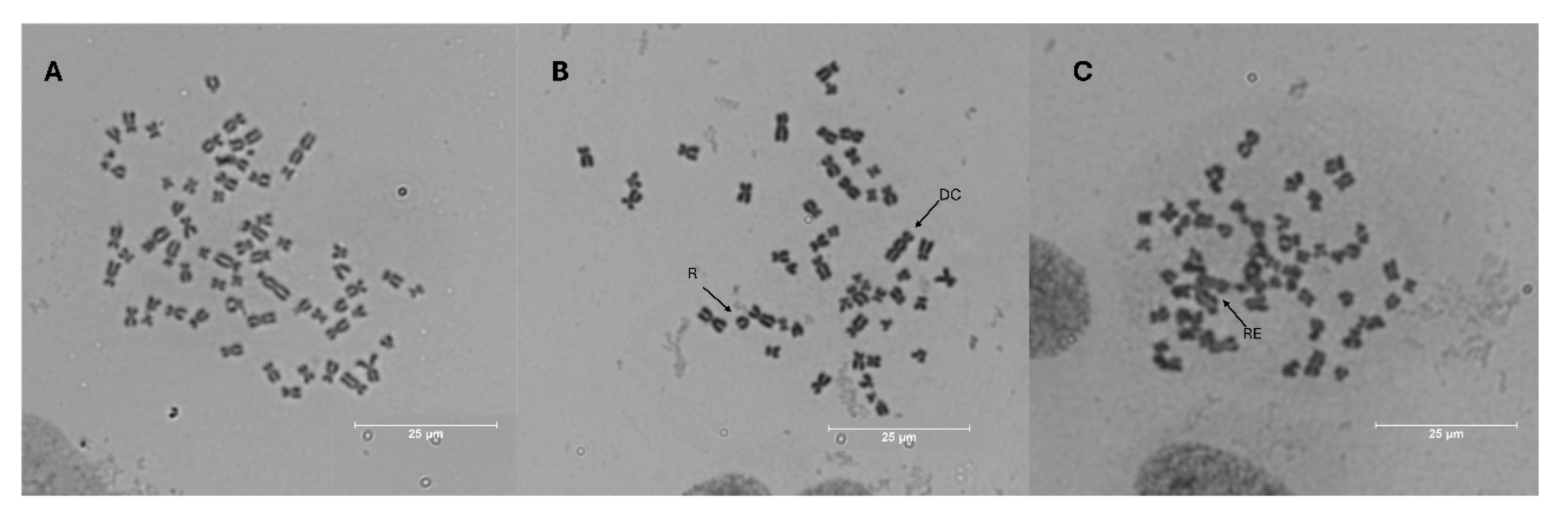

3.5. Chromosomal Aberration

The therapeutic potential of plant-derived extracts has been increasingly explored in cancer research, particularly for their ability to mitigate genotoxic damage induced by chemotherapeutic agents [

47]. The HE50 extract was chosen for the chromosomal aberration tests due to its chemical composition rich in phenolic compounds, flavonoids, flavonoids, flavonoids, flavonoids, flavonols, and ortho-diphenols, recognized for their antioxidants and cytoprotective properties [

48,

49]. To induce chromosomal aberration a known alkylating agent (cisplatin) was used [

21]. Cisplatin triggers blockage in cell division and leads to apoptosis in cancer cells by selective binding to 1,2-intra and interstrand crosslinking with purine bases on DNA, disrupting its repair and replication. Also, it involves intrinsic and extrinsic mitochondrial pathways such as p53 signaling and cell cycle arrest, upregulating pro-apoptotic genes and proteins [

43,

47].

Herein,

Table 4 shows that the HE50 solely did not induce chromosomal aberrations in the A549 cell line even at 20 µg GAE/ mL, and it was able to reduce the chromosomal damage lower than basal levels by 50% at 50 µg GAE/mL. Furthermore, the concentrations of 5, 10, and 20 µg GAE/ mL of the extract were able to reduce by 32%, 43%, and 45% the chromosomal aberrations caused by cisplatin, respectively. Similarly, another study observed that camu-camu seed extract presented protective action by decreasing 37% of the chromosomal breaks index, attenuating cisplatin-induced mutagenic damage [

21]. It has been shown that cisplatin generates lipid peroxidation and ROS generation directly or indirectly through mitochondria resulting in the impairment of the synthesis of electron transport chain proteins [

43,

47]. Taking into account, the combination of reduced lipoperoxidation rate, ROS generation, and viability of the A549 cell line, suggests that the ability of our extract to inhibit chromosomal aberrations indicates a protective effect against cisplatin-induced oxidative damage, likely linked to its antioxidant and cytotoxic properties [

21], as demonstrated in the previous sections.

Additionally, compared to basal events (

Figure 5A), the types of chromosomal aberrations found in high frequency in our study, such as dicentric chromosome (CD), rearrangement (RE), and ring (R) are demonstrated in

Figure 5B-C. According to Bonassi et al. [

50], a great number of rearrangements could be indicative of intense genomic damage, and its presence is often associated with severe genotoxicity and chromosomal instability, suggesting that cisplatin has caused profound damage. In this sense, as demonstrated by

Table 4, our extract reduced the rearrangement events by more than 50% and protected A549 cells against cisplatin damage, acting as an antimutagenic agent.

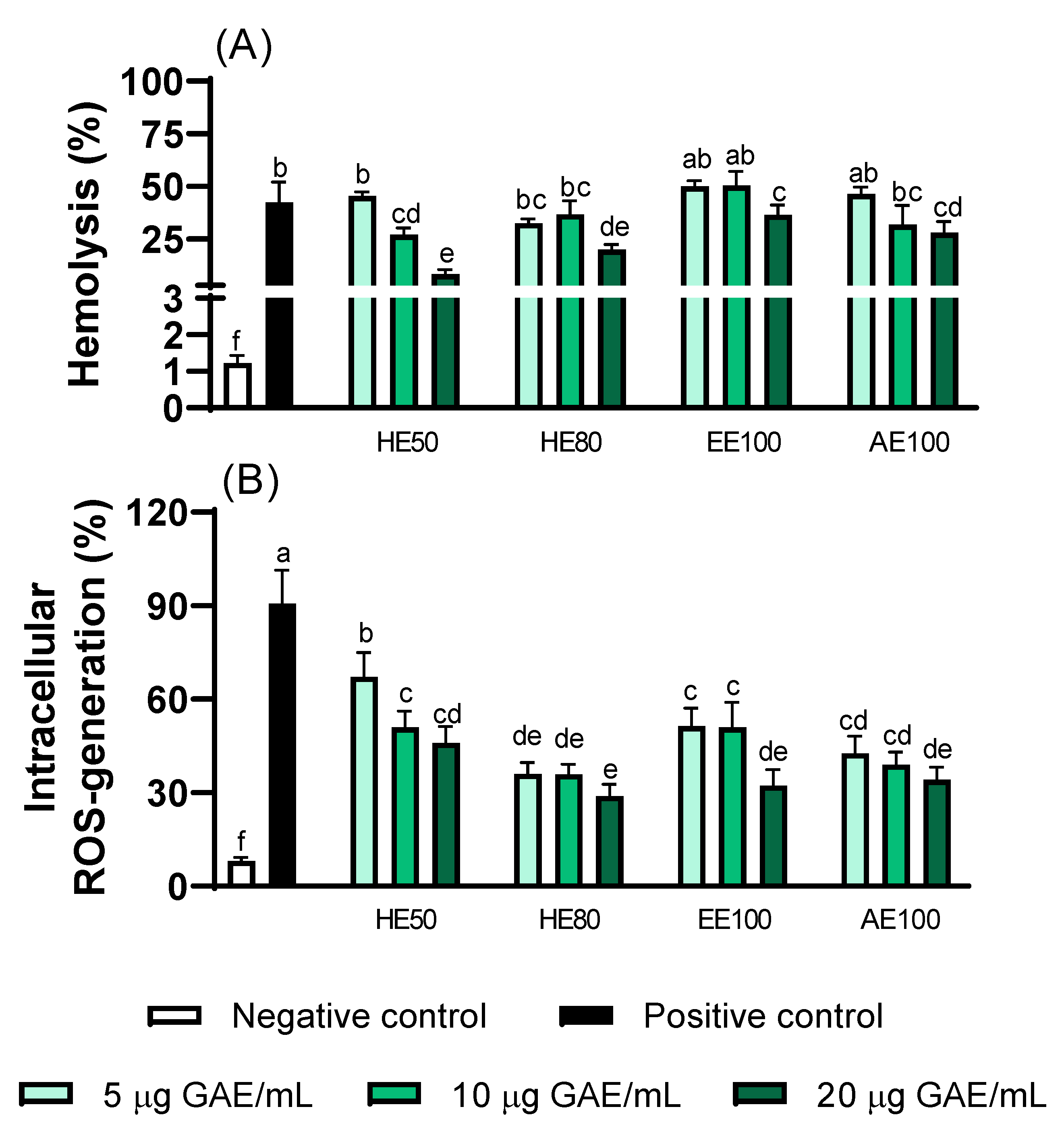

3.6. Effects of T. guianensis Extracts on Erythrocyte Protection

The ability of

T. guianensis extracts to protect the red blood cells (RBCs) from AAPH-induced oxidative stress was evaluated by measuring hemolysis rate (%) and intracellular ROS (

Figure 6). Considering that RBCs are vulnerable to oxidative damage due to their involvement in hemoglobin redox reactions [

22], extracts with higher concentrations of phenolic compounds could present various degrees of antioxidant activity, reflecting in ROS reduction and lower oxidant environment [

12]. Our results show that hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80) exhibited greater antioxidant protection in erythrocytes among all the extracts.

In terms of protecting the erythrocyte membrane from lysis, all the extracts presented antihemolytic activity (

Figure 6A). HE50 extract demonstrated a significant reduction in hemolytic response against AAPH-induced stress in a dose-dependent manner, while HE80, EE100, and AE100 provide lower levels of hemolysis at higher concentrations. The same behavior is reflected regarding intracellular ROS with the greatest protection against oxidation by AAPH from the HE80 extract (67% reduction at 20 µg GAE/mL), and in a dose-dependent manner in the HE50 and AE100 extracts (

Figure 6B). These findings are consistent with previous studies that certain polyphenol-rich natural extracts perform antioxidant activity in reducing the levels of intracellular ROS and hemolysis in RBCs [

14,

22].

Reports in the literature using natural extracts proved that this membrane protection and responses are mainly attributed to the extraction type and phenolic content, as demonstrated in our chemical analysis, suggesting that this relationship is well established [

19,

22]. Also, considering the extraction type, as shown in our results with HE50 and HE80, the balance of hydrophilic and lipophilic polyphenols extracted demonstrates that the effective extraction of the compounds promotes ROS suppression and membrane stabilization without excessive disruption [

19].

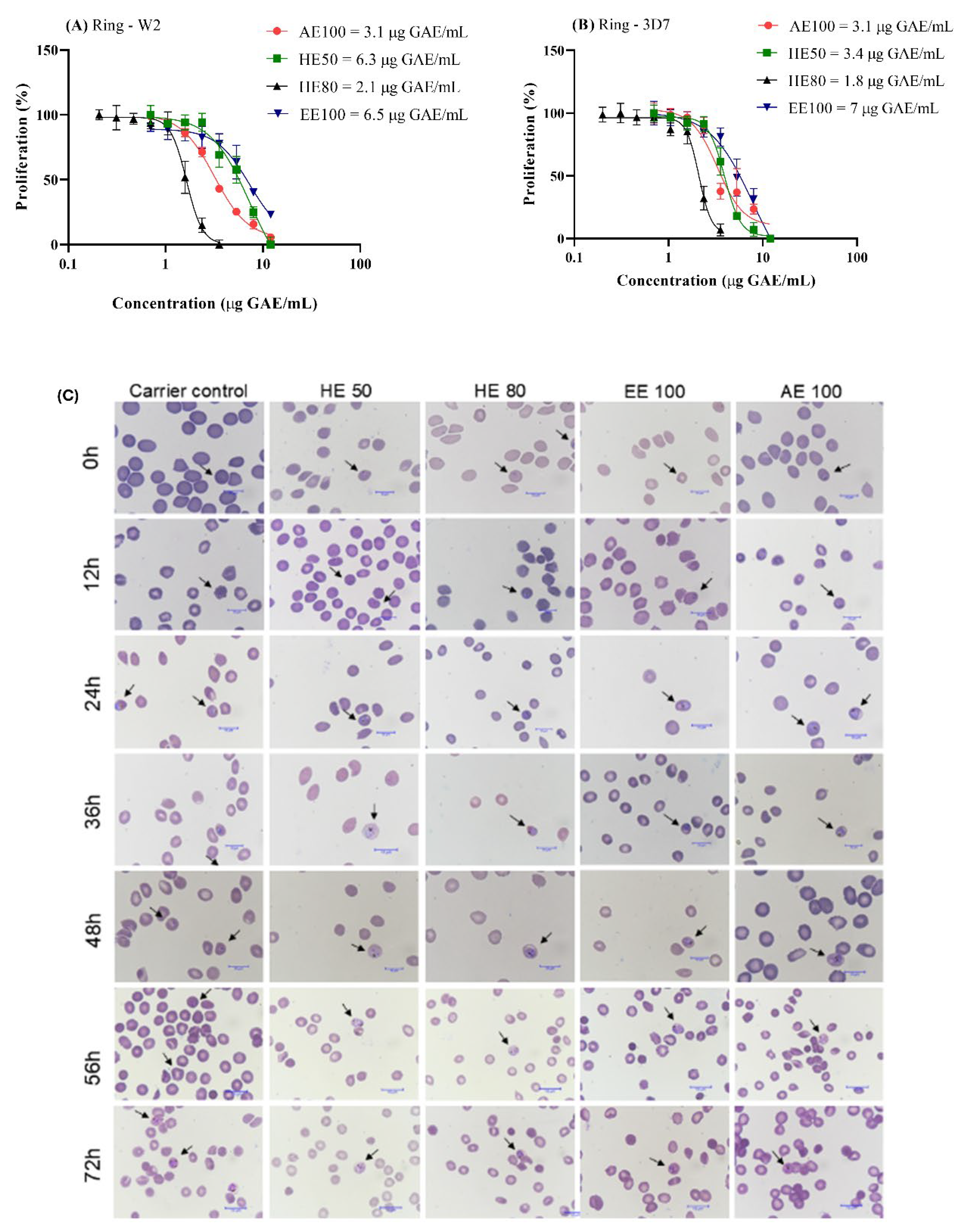

3.7. T. guianensis Extracts Present Antimalarial Activity Against P. falciparum

The efficacy of antimalarial drugs acting against the blood stage of infection has been increasingly threatened, since the spread of chloroquine resistance in

Plasmodium falciparum in 1960 [

51,

52]. This widespread resistance underscores the urgency to identify new antimalarial agents capable of acting against both chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains, ensuring global applicability and effectiveness.

In this context, the antiplasmodial activity of

T. guianensis seed extracts was assessed against both the 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant) strains of

P. falciparum. Remarkably, both strains exhibited high sensitivity to all tested extracts (

Figure 7A-B). Considering the antiparasitic activity classification by Jansen et al. [

53], HE80 and AE100 needed the lowest concentration to reach the IC50, displaying a high antimalarial activity in both strains (IC50 ≤ 5 μg/mL), while HE50 and EE100 demonstrated promising activity (5 μg/mL < IC50 ≤ 15 μg/mL). This highlights the potential of

T. guianensis extracts to overcome the challenges posed by chloroquine resistance, which is now prevalent in many endemic regions [

54,

55].

In a study conducted by Roumy et al. [

4], the antiplasmodial activity of the dichloromethanolic extract of

T. guianensis bark and its isolated fractions was evaluated. The activity of the mixture of 4,6,20-trihydroxy-6-[100(Z)-heptadecenyl]-2-cyclohexenone and 1,4,6-trihydroxy-1,20-epoxy-6-[100(Z)-heptadecenyl]-2-cyclohexene against chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains produced IC50 values that were 4 to 5 times lower compared to the dichloromethanolic extract. This promising activity against

P. falciparum was attributed to the compound 4,6,20-trihydroxy-6-[100(Z)-heptadecenyl]-2-cyclohexanone, which contains a conjugated ketone, a feature often associated with pharmacological activity. The same compound was found in the extracts of

T. guianensis seeds, which could serve as an accessible therapeutic alternative for further investigation as an antiplasmodial drug.

Evaluating the SI value is crucial for considering a promising antimalarial agent non-toxic and safe. Values higher than 10 are considered indicative of a lack of toxicity in cells compared to the

P. falciparum [

25,

56]. This parameter is especially important for ensuring that a treatment selectively targets the parasite while preserving human cells. In this study, the SI obtained for all the extracts and both strains were higher than 10 (SI from 15.5 to 70.5), mainly HE80, indicating that

T. guianensis seed extract was more toxic to

P. falciparum than to HUVEC normal cells.

To determine how

T. guianensis seed extracts act against

Plasmodium falciparum, we investigated which stage of the parasite's intraerythrocytic cycle is affected. A Panoptic fast-stained preparation was made using infected erythrocytes at 1% parasitemia (3D7 strain) and 2% hematocrit, following the addition of the IC

50 concentrations of all the extracts to investigate which stage of the parasite's intraerythrocytic lifecycle is inhibited by

T. guianensis seed extracts over 72 hours.

Figure 7C shows that the

T. guianensis extracts affect the first intracellular developmental cycle (IDC), preventing parasite growth beyond the schizont stage, indicating inhibition of schizont segmentation and erythrocyte rupture. This effect on the first IDC aligns with recommendations from the World Health Organization [

8], as it mirrors the action of artemisinin, the reference drug in antimalarial treatment.

Additionally, this effect is superior to antimalarial drugs like clindamycin, doxycycline, and atovaquone, which exhibit delayed death effects by targeting apicoplast replication [

57] or ubiquinone metabolism [

58] in later IDCs. On the other hand, drugs that affect essential apicoplast pathways, such as fatty acid or isoprenoid biosynthesis, are particularly valuable as they can inhibit the parasite in the first IDC [

59,

60]. The ability of the

T. guianensis seed extract to kill

P. falciparum in the first IDC suggests the presence of bioactive compounds with antimalarial potential that may target similar pathways or act on complementary mechanisms to those of fast-acting drugs, like artemisinin. Future studies could investigate whether any components of the

T. guianensis extract act as inhibitors of these metabolic pathways, providing new insights into its mechanism of action and potential as a source of novel targeted antimalarial agents.

Fast-acting drugs, such as artemisinin derivatives, play a critical role in malaria treatment by rapidly reducing parasitemia and preventing disease progression, especially in severe cases. The fact that the extract demonstrates comparable effects is highly relevant given: (i) the limited number of antimalarials capable of rapid action and (ii) the increasing need for new drugs to address resistance and treatment efficacy. Additionally, the development of compounds with complementary or synergistic targets to fast-acting drugs could enhance therapeutic efficacy and delay resistance emergence [

8]. This reinforces the necessity of characterizing the active constituents of

T. guianensis and elucidating their mechanisms of action.

Conclusions

In this work, T. guianensis seed extracts show promising therapeutic potential due to their selective activities in various biological systems. The cytoprotective, antiproliferative, and antimalarial activities of hydroethanolic extracts were demonstrated to reinforce the value of T. guianensis as a potential source of bioactive compounds, as demonstrated in chemical profile and antioxidant capacity. In cellular assays, the HE50 and HE80 extracts showed cytotoxicity for cancer cells compared to normal cells, reinforcing their potential as selective antiproliferative agents. In addition, the extracts exhibited robust antioxidant properties, reducing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cancer and normal cells, while protecting erythrocytes against oxidative damage. HE50's ability to mitigate cisplatin-induced chromosomal aberrations highlights its cytoprotective and antimutagenic potential, supporting its application as a complementary agent in chemotherapy. Similarly, the HE80 extract stood out for its selectivity indices, especially in the antimalarial tests, showing SI values of 70 for the chloroquine-sensitive strain of Plasmodium falciparum (3D7) and 60 for the chloroquine-resistant strain (W2), indicating significant specific toxicity for the parasites. These results highlight the therapeutic relevance of phenolic compounds extracted from T. guianensis seeds, especially when extracted with hydroethanolic solvents, and pave the way for future in vivo studies to confirm their safety and efficacy.

Authorship contribution statement

Thaise Caputo Silva and Marcell Crispim: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Nathália Alves Bento: Formal analysis, Methodology. Amanda dos Santos Lima, Thiago Mendanha Cruz, Yasmin Stelle, and Laura da Silva Cruz: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Josiana Moreira Mar, Daniel de Queiroz Rocha: Formal analysis. Luciana Azevedo and Jaqueline de Araújo Bezerra: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Data curation, Writing – review, and editing.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Ethics Statements

All experiments and procedures involving biological samples were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and approved by the Federal University of Alfenas committee - Ethics approval n° 6.910.474.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support provided by the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG) [APQ-04299-22; APQ-02221-24], the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) [grant number 422096-2021-0; 306799/2021-9] and the analytical support from SAMSUNG SRBR WTS Laboratory (Industrial District, Manaus/AM). Canva is also acknowledged as the icon used in the graphical abstract.

References

- Silva E, David J, David JP, Garcia G, Silva M. Chemical composition of biological active extracts of Tapirira guianensis (Anacardiaceae). Quim Nova 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mar JM, Corrêa RF, Ramos A da S, Kinupp VF, Sanches EA, Campelo PH; et al. Enhancing Bioactive Compound Bioaccessibility in Tapirira guianensis Juices through Ultrasound-Assisted Applications. Processes 2023, 11, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva E, David J, David JP, Garcia G, Silva M. CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF BIOLOGICAL ACTIVE EXTRACTS OF Tapirira guianensis (ANACARDIACEAE). Quim Nova 2020. [CrossRef]

- Roumy V, Fabre N, Portet B, Bourdy G, Acebey L, Vigor C; et al. Four anti-protozoal and anti-bacterial compounds from Tapirira guianensis. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 305–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Tsao R. Dietary polyphenols, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Curr Opin Food Sci 2016, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, mechanism, and applications of phenolic antioxidants in foods. J Food Biochem 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2020 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization 2022.

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2024: Addressing Inequity in the Global Malaria Response; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024 (accessed on 12/12/2024).

- Rosenthal, PJ. The interplay between drug resistance and fitness in malaria parasites. Mol Microbiol 2013, 89, 1025–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar K, Bhattacharjee S, Safeukui I. Drug resistance in Plasmodium. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 156–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2013, 1830, 3670–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo M, Granato D, Azevedo L. Antioxidant/pro-oxidant and antiproliferative activities of phenolic-rich foods and extracts: A cell-based point of view. Adv Food Nutr Res. 1st ed., Elsevier Inc.; 2021, p. 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Wen C, Zhang J, Zhang H, Dzah CS, Zandile M, Duan Y; et al. Advances in ultrasound assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from cash crops – A review. Ultrason Sonochem 2018, 48, 538–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima A dos S, de Oliveira Pedreira FR, Bento NA, Novaes RD, dos Santos EG, de Almeida Lima GD; et al. Digested galactoglucomannan mitigates oxidative stress in human cells, restores gut bacterial diversity, and provides chemopreventive protection against colon cancer in rats. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 277, 133986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo MAV, Fidelis M, Sanchez CA, Castro AP, Camps I, Colombo FA; et al. Camu-camu (Myrciaria dubia) seeds as a novel source of bioactive compounds with promising antimalarial and antischistosomicidal properties. Food Research International 2020, 136, 109334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato D, Reshamwala D, Korpinen R, Azevedo L, Vieira do Carmo MA, Cruz TM; et al. From the forest to the plate – Hemicelluloses, galactoglucomannan, glucuronoxylan, and phenolic-rich extracts from unconventional sources as functional food ingredients. Food Chem 2022, 381, 132284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Athayde AE, de Araujo CES, Sandjo LP, Biavatti MW. Metabolomic analysis among ten traditional “Arnica” (Asteraceae) from Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 265, 113149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu L, Liu Y, Wu H, Zhou A. Rapid identification of absorbed components and metabolites of Gandou decoction in rat plasma and liver by UPLC-Q-TOF-MSE. Journal of Chromatography B 2020, 1137, 121934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi N, Dos Santos Lima A, Azevedo L, Granato D. Bridging the gap in antioxidant activity of flavonoids: Correlating the oxidation of human plasma with chemical and cellular assays. Curr Res Food Sci 2024,8. [CrossRef]

- Fidelis M, Vieira do Carmo MA, Azevedo L, Cruz TM, Marques MB, Myoda T; et al. Response surface optimization of phenolic compounds from jabuticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora [Mart.] O.Berg) seeds: Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihyperglycemic, antihypertensive and cytotoxic assessments. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2020, 142, 111439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo MAV, Fidelis M, Pressete CG, Marques MJ, Castro-Gamero AM, Myoda T; et al. Hydroalcoholic Myrciaria dubia (camu-camu) seed extracts prevent chromosome damage and act as antioxidant and cytotoxic agents. Food Research International 2019, 125, 108551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz TM, Lima A dos S, Silva AO, Mohammadi N, Zhang L, Azevedo L; et al. High-throughput synchronous erythrocyte cellular antioxidant activity and protection screening of phenolic-rich extracts: Protocol validation and applications. Food Chem 2024, 440, 138281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trager W, Jensen JB. Human Malaria Parasites in Continuous Culture. Science (1979) 1976, 193, 673–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocytic Stages in Culture. J Parasitol 1979, 65, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves UV, Jardim e Silva E, dos Santos JG, Santos LO, Lanna E, de Souza Pinto AC; et al. Potent and selective antiplasmodial activity of marine sponges from Bahia state, Brazil. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2021, 17, 80–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Valbuena D, Ayora-Talavera T, Luján-Hidalgo C, Álvarez-Gutiérrez P, Martínez-Galero N, Meza-Gordillo R. Ultrasound extraction conditions effect on antioxidant capacity of mango by-product extracts. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2021, 127, 212–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz TM, Santos JS, do Carmo MAV, Hellström J, Pihlava J-M, Azevedo L; et al. Extraction optimization of bioactive compounds from ora-pro-nobis (Pereskia aculeata Miller) leaves and their in vitro antioxidant and antihemolytic activities. Food Chem 2021, 361, 130078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martín E, Forbes-Hernández T, Romero A, Cianciosi D, Giampieri F, Battino M. Influence of the extraction method on the recovery of bioactive phenolic compounds from food industry by-products. Food Chem 2022, 378, 131918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma J-Y, Zhou X, Fu J, He C-Y, Feng R, Huang M; et al. In Vivo Metabolite Profiling of a Purified Ellagitannin Isolated from Polygonum capitatum in Rats. Molecules 2016, 21, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubrow GA, Tello E, Schwartz E, Forero DP, Peterson DG. Identification of non-volatile compounds that impact consumer liking of strawberry preserves: Untargeted LC–MS analysis. Food Chem 2022, 378, 132042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia S de J, DavidI JM, Silva EP da, David JP, Lopes LMX, Guedes MLS. Flavonóides, norisoprenóides e outros terpenos das folhas de Tapirira guianensis. Quim Nova 2008, 31, 2056–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira ESC, Pontes FLD, Acho LDR, do Rosário AS, da Silva BJP, de A. Bezerra J; et al. qNMR quantification of phenolic compounds in dry extract of Myrcia multiflora leaves and its antioxidant, anti-AGE, and enzymatic inhibition activities. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2021, 201, 114109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao F, Xu T, Lu B, Liu R. Guidelines for antioxidant assays for food components. Food Front 2020, 1, 60–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor PG, Cesari IM, Arsenak M, Ballen D, Abad MJ, Fernández A; et al. Evaluation of Venezuelan Medicinal Plant Extracts for Antitumor and Antiprotease Activities. Pharm Biol 2006, 44, 349–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Oliveira R, Lopes G, Camargos L, Ribeiro A, Santos F, Severino R; et al. Tapirira guianensis Aubl. Extracts Inhibit Proliferation and Migration of Oral Cancer Cells Lines. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato NN, Stavis VK, Boaretto AG, Castro DTH, Alves FM, de Picoli Souza K; et al. Application of the metabolomics approach to the discovery of active compounds from Brazilian trees against resistant human melanoma cells. Phytochemical Analysis 2021, 32, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein-Al-Ali SH, Al-Qubaisi M, Rasedee A, Hussein MZ. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Effect of Ellagic Acid Nanocomposite in Lung Cancer A549 Cell Line and RAW 264.9 Cells. Journal of Bionanoscience 2017, 11, 578–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Liang X, Niu C, Wang X. Ellagic acid promotes A549 cell apoptosis via regulating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. Exp Ther Med 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ko E-B, Jang Y-G, Kim C-W, Go R-E, Lee HK, Choi K-C. Gallic Acid Hindered Lung Cancer Progression by Inducing Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in A549 Lung Cancer Cells via PI3K/Akt Pathway. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2022, 30, 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsantila EM, Esslinger N, Christou M, Papageorgis P, Neophytou CM. Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity of Vitis vinifera Extracts in Breast Cell Lines. Life 2024, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose K, Selvaraj K, McCallum J, Kirby CW, Sweeney-Nixon M, Cloutier SJ; et al. Identification and functional characterization of a flax UDP-glycosyltransferase glucosylating secoisolariciresinol (SECO) into secoisolariciresinol monoglucoside (SMG) and diglucoside (SDG). BMC Plant Biol 2014, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat Kose L, Gulcin İ. Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antiradical Properties of Some Phyto and Mammalian Lignans. Molecules 2021, 26, 7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura H, Takada K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci 2021, 112, 3945–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira V, Hay N. Molecular Pathways: Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis in Cancer Cells and Implications for Cancer Therapy. Clinical Cancer Research 2013, 19, 4309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez-Andrade M, Quezada-Maldonado EM, Rivera-Pineda A, Chirino YI, García-Cuellar CM, Sánchez-Pérez Y. The Road to Malignant Cell Transformation after Particulate Matter Exposure: From Oxidative Stress to Genotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: Concept and Some Practical Aspects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou PB, Dasari S, Noubissi FK, Ray P, Kumar S. Advances in Our Understanding of the Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Cisplatin in Cancer Therapy. J Exp Pharmacol 2021, 13, 303–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazafa A, Rehman KU, Jahan N, Jabeen Z. The Role of Polyphenol (Flavonoids) Compounds in the Treatment of Cancer Cells. Nutr Cancer 2020, 72, 386–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Carmo MAV, Pressete CG, Marques MJ, Granato D, Azevedo L. Polyphenols as potential antiproliferative agents: Scientific trends. Curr Opin Food Sci 2018, 24, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonassi S, Norppa H, Ceppi M, Stromberg U, Vermeulen R, Znaor A; et al. Chromosomal aberration frequency in lymphocytes predicts the risk of cancer: Results from a pooled cohort study of 22 358 subjects in 11 countries. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 1178–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen C, Alonso P, Ringwald P. Current and emerging strategies to combat antimalarial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2022, 20, 353–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal W, Castro W, González S, Madamet M, Amalvict R, Pradines B; et al. Copper (I)-Chloroquine Complexes: Interactions with DNA and Ferriprotoporphyrin, Inhibition of β-Hematin Formation and Relation to Antimalarial Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen O, Tits M, Angenot L, Nicolas J-P, De Mol P, Nikiema J-B; et al. Anti-plasmodial activity of Dicoma tomentosa (Asteraceae) and identification of urospermal A-15-O-acetate as the main active compound. Malar J 2012, 11, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed WSA, Yasin K, Mahgoub NS, Abdel Hamid MM. Cross sectional study to determine chloroquine resistance among Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from Khartoum, Sudan. F1000Res 2018, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foguim FT, Bogreau H, Gendrot M, Mosnier J, Fonta I, Benoit N; et al. Prevalence of mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter, PfCRT, and association with ex vivo susceptibility to common anti-malarial drugs against African Plasmodium falciparum isolates. Malar J 2020, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali AH, Agustar HK, Hassan NI, Latip J, Embi N, Sidek HM. Data on antiplasmodial and stage-specific inhibitory effects of Aromatic (Ar)-Turmerone against Plasmodium falciparum 3D7. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy L, Sandhu JK, Harper ME, Cuperlovic-culf M. Role of glutathione in cancer: From mechanisms to therapies. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter HJ, Morrisey JM, Vaidya AB. Mitochondrial Electron Transport Inhibition and Viability of Intraerythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 5281–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminake MN, Schoof S, Sologub L, Leubner M, Kirschner M, Arndt H-D; et al. Thiostrepton and Derivatives Exhibit Antimalarial and Gametocytocidal Activity by Dually Targeting Parasite Proteasome and Apicoplast. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 1338–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biosca A, Ramírez M, Gomez-Gomez A, Lafuente A, Iglesias V, Pozo OJ; et al. Characterization of Domiphen Bromide as a New Fast-Acting Antiplasmodial Agent Inhibiting the Apicoplastidic Methyl Erythritol Phosphate Pathway. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira ESC, Pontes FLD, Acho LDR; et al. NMR and multivariate methods: Identification of chemical markers in extracts of pedra-ume-caá and their antiglycation, antioxidant, and enzymatic inhibition activities. Phytochem Anal. 2024, 35, 552–566 https://. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira ZC, Cruz JMA, Castro DRG; et al. Passiflora nitida Kunth fruit: Chemical analysis, antioxidant capacity, and cytotoxicity. Food Science and Technology, v. 44, p. 1–8, 2024. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(A) UPLC-QToF/MS (negative mode) TIC chromatographic profile of the four extracts and (B) Chemical structures of some substances identified in the T. guianensis seeds, where (3) 4,6,2’-trihydroxi-6-[10’(Z)-heptadecenyl]-1-cyclohexene-2-one; (4) Gallic acid; (5) (6S,7E,9S)-6,9-dihydroxy-megastigma-4,7-dien-3-one 9-O-β-glucopyranoside; (6) Ellagic acid and (7) e (−)-Secoisolariciresinol-9’-O-β-d-glucopyranoside.

Figure 1.

(A) UPLC-QToF/MS (negative mode) TIC chromatographic profile of the four extracts and (B) Chemical structures of some substances identified in the T. guianensis seeds, where (3) 4,6,2’-trihydroxi-6-[10’(Z)-heptadecenyl]-1-cyclohexene-2-one; (4) Gallic acid; (5) (6S,7E,9S)-6,9-dihydroxy-megastigma-4,7-dien-3-one 9-O-β-glucopyranoside; (6) Ellagic acid and (7) e (−)-Secoisolariciresinol-9’-O-β-d-glucopyranoside.

Figure 2.

Effect of T. guianensis seed extracts on the Fe2+-induced lipoperoxidation rates observed in egg yolk. Different letters in the same graph represent statistically different results (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of T. guianensis seed extracts on the Fe2+-induced lipoperoxidation rates observed in egg yolk. Different letters in the same graph represent statistically different results (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Cell viability and evaluation of the concentration-dependent effect after 48 h exposure to hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80), ethanolic extract (EE100) and aqueous extract (AE100) of T. guianensis seeds extract in (A) HCT-8, (B) A549 and (C) HUVEC cell lines. IC50 (concentration of the agent that inhibits cell growth by 50%). Concentrations are expressed in μg GAE/mL of extract.

Figure 3.

Cell viability and evaluation of the concentration-dependent effect after 48 h exposure to hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80), ethanolic extract (EE100) and aqueous extract (AE100) of T. guianensis seeds extract in (A) HCT-8, (B) A549 and (C) HUVEC cell lines. IC50 (concentration of the agent that inhibits cell growth by 50%). Concentrations are expressed in μg GAE/mL of extract.

Figure 4.

Results of intracellular ROS measurement in (A) HUVEC, (B) HCT-8, and (C) A549 cells by spectrofluorimetric method, treated with hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80), ethanolic extract (EE100) and aqueous extract (AE100) of T. guianensis seeds at 10-25 μg GAE/mL. Quantitative data is the mean ± SD (n = 5). Different letters represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Results of intracellular ROS measurement in (A) HUVEC, (B) HCT-8, and (C) A549 cells by spectrofluorimetric method, treated with hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80), ethanolic extract (EE100) and aqueous extract (AE100) of T. guianensis seeds at 10-25 μg GAE/mL. Quantitative data is the mean ± SD (n = 5). Different letters represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs (1000×) of metaphase plate of A549 cells: (A) Negative control, (B) 4 μM cisplatin and (C) 20 µg GAE/ mL group. Different kinds of chromosomal aberrations were observed, such as ring (R), dicentric chromosome (DC) and rearrangement (RE).

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs (1000×) of metaphase plate of A549 cells: (A) Negative control, (B) 4 μM cisplatin and (C) 20 µg GAE/ mL group. Different kinds of chromosomal aberrations were observed, such as ring (R), dicentric chromosome (DC) and rearrangement (RE).

Figure 6.

AAPH-induced hemolysis (A) and intracellular ROS generation (B) in human erythrocytes. Different letters represent significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 6.

AAPH-induced hemolysis (A) and intracellular ROS generation (B) in human erythrocytes. Different letters represent significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 7.

Antimalarial activity of hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80), ethanolic extract (EE100), and aqueous extract (AE100) of T. guianensis seed on the (A) W2-chloroquine-resistant strain and (B) 3D7-chloroquine-sensitive strain. (C) Microscopy panoptic fast-stained smears of tightly synchronized P. falciparum. Effects of T. guianensis on parasite development at different intervals in the presence of RPMI culture medium with 10% Albumax II (as a control) and the extracts. The arrows indicate intraerythrocytic structures of P. falciparum 3D7 strain. Concentrations are expressed in μg GAE/mL of seed extract.

Figure 7.

Antimalarial activity of hydroethanolic extracts (HE50 and HE80), ethanolic extract (EE100), and aqueous extract (AE100) of T. guianensis seed on the (A) W2-chloroquine-resistant strain and (B) 3D7-chloroquine-sensitive strain. (C) Microscopy panoptic fast-stained smears of tightly synchronized P. falciparum. Effects of T. guianensis on parasite development at different intervals in the presence of RPMI culture medium with 10% Albumax II (as a control) and the extracts. The arrows indicate intraerythrocytic structures of P. falciparum 3D7 strain. Concentrations are expressed in μg GAE/mL of seed extract.

Table 1.

Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity per gram of dried T. guianensis seed extracts.

Table 1.

Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity per gram of dried T. guianensis seed extracts.

| Compounds |

HE50 |

HE80 |

EE100 |

AE100 |

| TPC (mg GAE/g) |

53 ± 1a

|

23 ± 1c

|

14 ± 0.6d

|

32 ± 0.7b

|

| TFC (mg CE/g) |

158 ± 11a

|

113 ± 2c

|

32 ± 4d

|

132 ± 2b

|

| Total flavonol content |

16 ± 1a

|

4 ± 0.3b

|

6 ± 0.7b

|

5 ± 1b

|

| (mg QE/g) |

Ortho-diphenols

(mg CAE/g) |

33 ± 1a

|

15 ± 0.5b

|

7 ± 0.4c

|

15 ± 1b

|

| Antioxidant activity |

| DPPH (mg AAE/g) |

103 ± 3b

|

78 ± 1c

|

27 ± 2d

|

119 ± 1a

|

| FRAP (mg AAE/g) |

87 ± 2a

|

54 ± 1b

|

24 ± 1d

|

50 ± 0.3c

|

| Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (mg GAE/g) |

16 ± 0.4d

|

44 ± 1b

|

23 ± 0.5c

|

53 ± 2a

|

Table 2.

Compounds identified in the dried T. guianensis seed extracts by using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS (negative mode) and 1D and 2D NMR.

Table 2.

Compounds identified in the dried T. guianensis seed extracts by using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS (negative mode) and 1D and 2D NMR.

| No |

RT (min) |

Adduct |

m/z |

Identified

mass |

Calculated mass |

Fragmentations

(m/z)

|

Compound

(Empirical formula, error in ppm) |

δ 1H in ppm (J, Hz) |

δ 13C in ppm |

References |

| 1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

α-glucose |

δ 5.08 (d; J=3.7 Hz, H-1) |

93.8 (C-1), 71.8 (C-2), 73.5 (C3). |

[62] |

| 2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

β-glucose |

δ 4.45 (d; J=7.7 Hz, H-1)

δ 3.31 (dd; J=9.2; 7.8 Hz, H-3) |

98.0 (C-1), 77.8 (C-3), 70.3 (C-4). |

[62] |

| 3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4,6,2’-trihydroxi-6-[10’(Z)-heptadecenyl]-1-cyclohexene-2-one

(C23H40O4) |

5.88 (dd, J = 10.2; 2.0 Hz, H-2); 6.92 (m, H-3); 1.90 (m, H-1’), 4.02 (m, H-2’); 5.31 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, H-10’, H-11’); 2.0 (m, H-12’), 0.88 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, H-17’). |

126.2 (C-2), 153.6 (C-3), 64.7 (C-4), 43.3 (C-1’), 70.7 (C-2’), 130.5 (C10’, C11’), 27.8 (C12’), 14.0 (C-17’). |

[4] |

| 4 |

1.8 |

[M-H]-

|

169.0133 |

170.0211 |

170.0215 |

125.0245 |

Gallic acid

(C7H5O5, -2.35) |

7.03 (s, H-2,6) |

108.8 (C-2, 6), 145.0 (C-3,5),

138.5 (C-4), 168.8 (C-7). |

[1,61] |

| 5 |

8.7 |

[M+Formic Acid-H]-

|

385.1892 |

386,1970 |

386.1940 |

431.1931

223.1338

205.1258 |

(6S,7E,9S)-6,9-dihydroxy-megastigma-4,7-dien-3-one 9-O-β-glucopyranoside

(C19H30O8, 7.77) |

2.44 (m, H-2ax)

2.56 (m, H-2eq) |

50.5 (C-2), 200.0 (C-3), 131.3 (C-7), 71.8 (C-4’). |

[31] |

| 6 |

10.8 |

[M-H]-

|

300.9990 |

302.00683 |

302.00626 |

283.9960

229.0141 185.0220 |

Ellagic acid

(C14H5O8, 1.88) |

7.53 (s, H-5’, H-5’). |

113.0 (C-1, C-1’), 139.7 (C-3, C-3’), 148.0 (C-4, C-4’), 110.5 (C5, C-5’), 108.1 (C6, C-6’), 160.0 (C-7, C-7’). |

[29,61] |

| 7 |

13.3 |

[M-H]-

|

523.2188 |

524.2266 |

524.2257 |

361.1647 |

(−)-Secoisolariciresinol-9’-O-β-d-glucopyranoside

(C26H36O11, 1.71) |

6.56 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-2);

6.63 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6); 3.49 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, H-9); 2.49 – 2.54 (m, H-7, H-7’); 1.91 (m, H-8); 6.58 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-2’); 6.63 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5’);

6.53 (m, H-6’); 4.20 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-1’’); 3.84 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-6’’); 3.63 (m, H-6’’); 3.82 (m, OCH3-3);

3.71 (s, OCH3-3’). |

113.3 (C-2), 147.2 (C-4), 122.4 (C-6), 61.1 (C9), 36.5 (C-7, C-7’); 43.5 (C-8), 132.7 (C-1’), 115.8 (C-2’), 147.4 (C-3’), 144.2 (C-4’), 115.5 (C-5’), 122.4 (C-6’), 104.3 (C-1’’)

62.5 (C-6”), 56.4 (OCH3-3)

56.0 (OCH3-3’) |

[30] |

Table 3.

Selectivity index for P. falciparum strains 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant), as well as A549 and HCT-8 cancer cell lines.

Table 3.

Selectivity index for P. falciparum strains 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant), as well as A549 and HCT-8 cancer cell lines.

| Extracts |

|

HUVEC / P. falciparum

|

|

HUVEC / Cancer cells |

| |

|

3D7 |

W2 |

|

A549 |

HCT-8 |

| HE50 |

|

28.4 |

15.5 |

|

1.7 |

2.2 |

| HE80 |

|

70.5 |

60.2 |

|

2.6 |

2.7 |

| EE100 |

|

20 |

21.3 |

|

0.6 |

1.2 |

| AE100 |

|

17.6 |

18 |

|

0.3 |

0.7 |

Table 4.

Results of the chromosome aberrations test in A549 cells treated with HE50 extract in vitro.

Table 4.

Results of the chromosome aberrations test in A549 cells treated with HE50 extract in vitro.

HE50

Dosage (µg GAE/mL) |

CIS |

TC |

Aberrant Type |

TNCA |

CA rate (%) |

| R |

DC |

FR |

CB |

CEB |

TC |

QC |

RE |

| NC |

|

4315 |

2 |

31 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

42b

|

1 |

| PC |

4 μM |

5239 |

8 |

40 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

22 |

78a

|

1.5 |

| 20 |

|

4343 |

3 |

19 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

9 |

40b

|

1 |

| 50 |

|

4367 |

0 |

15 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

21c

|

0.5 |

| 5 |

4 μM |

4045 |

7 |

29 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

2 |

6 |

41b

|

1 |

| 10 |

4 μM |

4038 |

5 |

22 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

34b

|

1 |

| 20 |

4 μM |

4269 |

3 |

30 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

35bc

|

1 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).