Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Systematic Review Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy and Databases

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed scientific articles published between 2015 and 2025.

- Experimental, comparative or modeling studies that explicitly report the headspace fraction () or related parameters (pressure, gas volume, CH4 yield).

- Publications that present verifiable data on pressure, temperature, volume or composition of biogas.

- Book reviews or chapters with active DOI and verifiable access.

- Documents without quantitative information related to headspace: absence of (VHS/Vtot), volume/gas phase ratio, measured pressure, or its impact on biogas/methane yield.

- Theses, technical reports or grey literature without peer review or verifiable DOI/URL, or without access to the full text.

- Duplicate records or studies with verifiable inconsistencies between text, tables and/or figures (e.g., discrepancies in (), pressure or units).

- Studies evaluating aerobic digestion, composting, nitrification/denitrification, photofermentative processes, oxy-fermentations, or other non-anaerobic technologies; or anaerobic studies that do not address the measurement or effect of headspace on pressure, gas–liquid equilibrium, or CH4 yield.

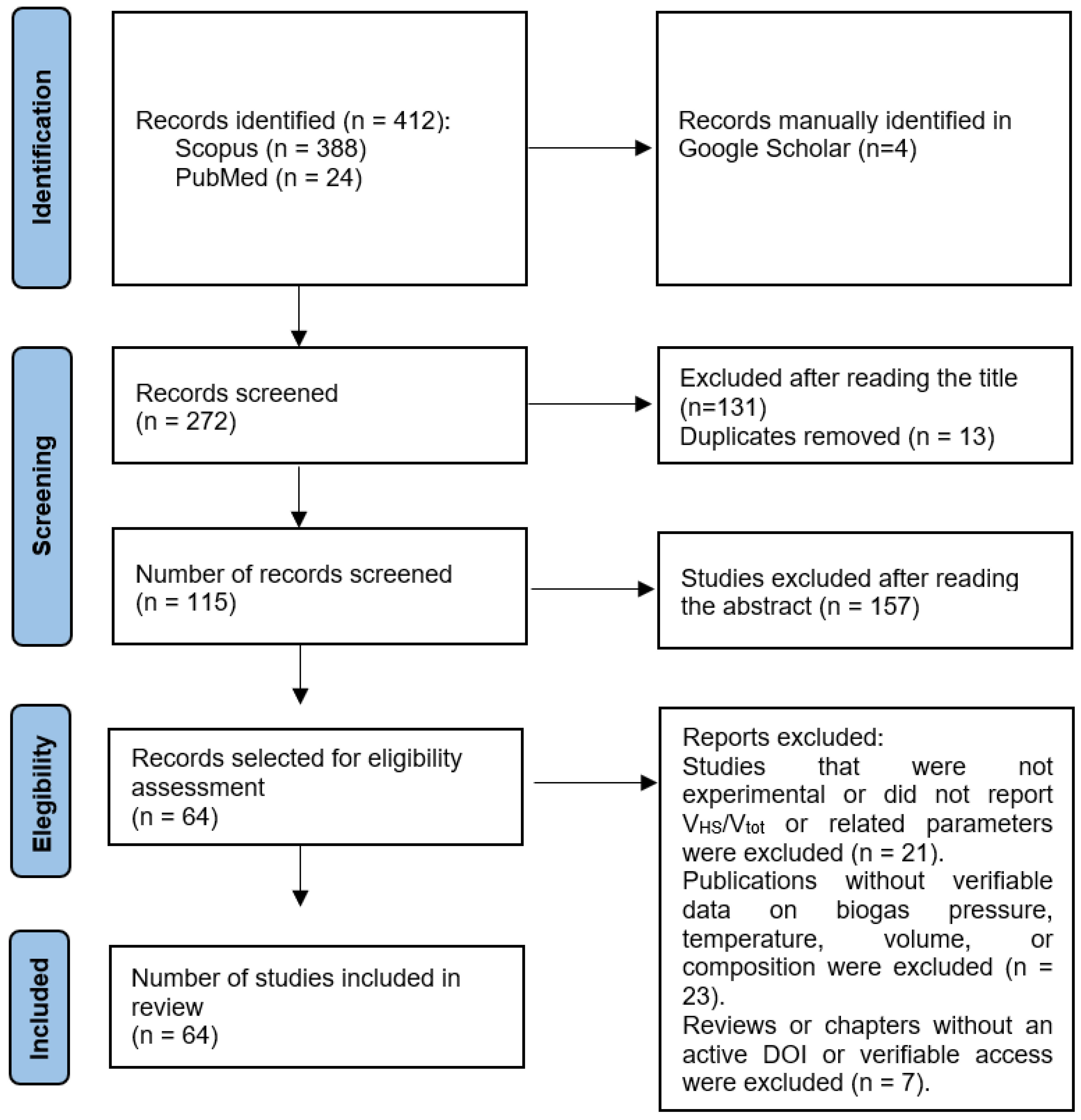

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Validation

- Scale and type of reactor (BMP, laboratory, pilot, industrial).

- Primary substrate type.

- Volumetric fraction of headspace ().

- Operating pressure and temperature.

- Biogas monitoring method (GC, NDIR, flow meters).

- Specific methane production (mL CH₄·g-1 VS or L CH₄·L-1·d-1).

- Reactor material and type of agitation.

2.5. Analysis and Synthesis of Information

2.6. Limitations of the Review

3. Technical Fundamentals of Headspace

4. Influence of Headspace on Process Performance

5. Influence of Headspace According to the Scale of Operation

6. Headspace Design and Operation

7. Predictive Modeling and Quantitative Impact of Headspace on Biodigester Efficiency

8. Conclusions

References

- Albiter, A., & Albiter, A. (2020). Sulfide Stress Cracking Assessment of Carbon Steel Welding with High Content of H2S and CO2 at High Temperature: A Case Study. Engineering, 12(12), 863–885. [CrossRef]

- Alqaralleh, R. M., Kennedy, K., & Delatolla, R. (2018). Improving biogas production from anaerobic co-digestion of Thickened Waste Activated Sludge (TWAS) and fat, oil and grease (FOG) using a dual-stage hyper-thermophilic/thermophilic semi-continuous reactor. Journal of Environmental Management, 217, 416–428. [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I., Treu, L., Tsapekos, P., Luo, G., Campanaro, S., Wenzel, H., & Kougias, P. G. (2018). Biogas upgrading and utilization: Current status and perspectives. Biotechnology Advances, 36(2), 452–466. [CrossRef]

- Aragüés-Aldea, P., Mercader, V. D., Durán, P., Francés, E., Peña, J., & Herguido, J. (2025). Biogas upgrading through CO2 methanation in a multiple-inlet fixed bed reactor: Simulated parametric analysis. Journal of CO2 Utilization, 93, 103038. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M. K., Ganeshan, P., Gohil, N., Kumar, V., Singh, V., Rajendran, K., Harirchi, S., Solanki, M. K., Sindhu, R., Binod, P., Zhang, Z., & Taherzadeh, M. J. (2023). Advanced approaches for resource recovery from wastewater and activated sludge: A review. Bioresource Technology, 384, 129250. [CrossRef]

- Aworanti, O. A., Agbede, O. O., Agarry, S. E., Ajani, A. O., Ogunkunle, O., Laseinde, O. T., Rahman, S. M. A., & Fattah, I. M. R. (2023). Decoding Anaerobic Digestion: A Holistic Analysis of Biomass Waste Technology, Process Kinetics, and Operational Variables. Energies 2023, Vol. 16, Page 3378, 16(8), 3378. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M. Y. U., Alves, I., Del Nery, V., Sakamoto, I. K., Pozzi, E., & Damianovic, M. H. R. Z. (2022). Methane production in a UASB reactor from sugarcane vinasse: shutdown or exchanging substrate for molasses during the off-season? Journal of Water Process Engineering, 47, 102664. [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, P. K., & Sabharwall, P. (2023). Sizing and Selection of Pressure Relief Valves for High-Pressure Thermal–Hydraulic Systems. Processes 2024, Vol. 12, Page 21, 12(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, T. M., & Santos, M. T. (2023). Biochemical Methane Potential Assays for Organic Wastes as an Anaerobic Digestion Feedstock. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 11573, 15(15), 11573. [CrossRef]

- Catenacci, A., Carecci, D., Leva, A., Guerreschi, A., Ferretti, G., & Ficara, E. (2024). Towards maximization of parameters identifiability: Development of the CalOpt tool and its application to the anaerobic digestion model. Chemical Engineering Journal, 499, 155743. [CrossRef]

- Catenacci, A., Santus, A., Malpei, F., & Ferretti, G. (2022). Early prediction of BMP tests: A step response method for estimating first-order model parameters. Renewable Energy, 188, 184–194. [CrossRef]

- Couto, N., Silva, V. B., Bispo, C., & Rouboa, A. (2016). From laboratorial to pilot fluidized bed reactors: Analysis of the scale-up phenomenon. Energy Conversion and Management, 119, 177–186. [CrossRef]

- De Crescenzo, C., Marzocchella, A., Karatza, D., Chianese, S., & Musmarra, D. (2024). Autogenerative high-pressure anaerobic digestion modelling of volatile fatty acids: Effect of pressure variation and substrate composition on volumetric mass transfer coefficients, kinetic parameters, and process performance. Fuel, 358, 130144. [CrossRef]

- De Crescenzo, C., Marzocchella, A., Karatza, D., Molino, A., Ceron-Chafla, P., Lindeboom, R. E. F., van Lier, J. B., Chianese, S., & Musmarra, D. (2022). Modelling of autogenerative high-pressure anaerobic digestion in a batch reactor for the production of pressurised biogas. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 2022 15:1, 15(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Di Leto, Y., Mineo, A., Capri, F. C., Gallo, G., Mannina, G., & Alduina, R. (2024). The effects of headspace volume reactor on the microbial community structure during fermentation processes for volatile fatty acid production. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 31(52), 61781–61794. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Domínguez, E., Rubio, J. Á., Lyng, J., Toro, E., Estévez, F., & García-Morales, J. L. (2025a). Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sewage Sludge and Organic Solid By-Products from Table Olive Processing: Influence of Substrate Mixtures on Overall Process Performance. Energies, 18(14), 3812. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Domínguez, E., Rubio, J. Á., Lyng, J., Toro, E., Estévez, F., & García-Morales, J. L. (2025b). Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sewage Sludge and Organic Solid By-Products from Table Olive Processing: Influence of Substrate Mixtures on Overall Process Performance. Energies, 18(14), 3812. [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M., Andres, Y., & Blel, W. (2022). Modeling of sludge and flax anaerobic co-digestion based on combination of first order and modified Gompertz models: influence of C/N ratio and headspace gas volume. Desalination and Water Treatment, 250, 136–147. [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Arriaga, E. B., Reynoso-Deloya, M. G., Guillén-Garcés, R. A., Falcón-Rojas, A., & García-Sánchez, L. (2021). Enhanced methane production and organic matter removal from tequila vinasses by anaerobic digestion assisted via bioelectrochemical power-to-gas. Bioresource Technology, 320, 124344. [CrossRef]

- Filer, J., Ding, H. H., & Chang, S. (2019). Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Assay Method for Anaerobic Digestion Research. Water 2019, Vol. 11, Page 921, 11(5), 921. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Zhi, Y., Huang, Y., Shi, S., Tan, Q., Wang, C., Han, L., & Yao, J. (2023). Effects of benthic bioturbation on anammox in nitrogen removal at the sediment-water interface in eutrophic surface waters. Water Research, 243, 120287. [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, T., Ghiasirad, H., & Skorek-Osikowska, A. (2024). Life cycle and techno-economic analyses of biofuels production via anaerobic digestion and amine scrubbing CO2 capture. Energy Conversion and Management, 321, 119066. [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S. D., & Astals, S. (2019). Systematic error in manometric measurement of biochemical methane potential: Sources and solutions. Waste Management, 91, 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S. D., de Laclos, H. F., Koch, K., & Holliger, C. (2020). Improving Inter-Laboratory Reproducibility in Measurement of Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP). Water 2020, Vol. 12, Page 1752, 12(6), 1752. [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, J. E., Herrmann, C., Petersen, S. O., Dragoni, F., Amon, T., Belik, V., Ammon, C., & Amon, B. (2023). Assessment of the biochemical methane potential of in-house and outdoor stored pig and dairy cow manure by evaluating chemical composition and storage conditions. Waste Management, 168, 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, H., Voelklein, M. A., Murphy, J. D., Grant, J., & O’Kiely, P. (2017a). Factors controlling headspace pressure in a manual manometric BMP method can be used to produce a methane output comparable to AMPTS. Bioresource Technology, 238, 633–642. [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, H., Voelklein, M. A., Murphy, J. D., Grant, J., & O’Kiely, P. (2017b). Factors controlling headspace pressure in a manual manometric BMP method can be used to produce a methane output comparable to AMPTS. Bioresource Technology, 238, 633–642. [CrossRef]

- Hmaissia, A., Hernández, E. M., Boivin, S., & Vaneeckhaute, C. (2025). Start-Up Strategies for Thermophilic Semi-Continuous Anaerobic Digesters: Assessing the Impact of Inoculum Source and Feed Variability on Efficient Waste-to-Energy Conversion. Sustainability 2025, Vol. 17, Page 5020, 17(11), 5020. [CrossRef]

- Holliger, C., Alves, M., Andrade, D., Angelidaki, I., Astals, S., Baier, U., Bougrier, C., Buffière, P., Carballa, M., De Wilde, V., Ebertseder, F., Fernández, B., Ficara, E., Fotidis, I., Frigon, J. C., De Laclos, H. F., Ghasimi, D. S. M., Hack, G., Hartel, M., … Wierinck, I. (2016). Towards a standardization of biomethane potential tests. Water Science and Technology, 74(11), 2515–2522. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Esparza, J., Ibarra-Esparza, F. E., González-López, M. E., Garcia-Gonzalez, A., & Gradilla-Hernández, M. S. (2025). Instrumentation and Continuous Monitoring for the Anaerobic Digestion Process: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H. M., Choi, Y. K., & Kan, E. (2018). Effects of dairy manure-derived biochar on psychrophilic, mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestions of dairy manure. Bioresource Technology, 250, 927–931. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., Tao, J., Luo, J., Xie, W., Zhou, X., Cheng, B., Guo, G., Ngo, H. H., Guo, W., Cai, H., Ye, Y., Chen, Y., & Pozdnyakov, I. P. (2023). Pilot-scale two-phase anaerobic digestion of deoiled food waste and waste activated sludge: Effects of mixing ratios and functional analysis. Chemosphere, 329, 138653. [CrossRef]

- Karsten, T., Ortiz, A. P., Schomäcker, R., & Repke, J.-U. (2025). Performance Evaluation of Different Reactor Concepts for the Oxidative Coupling of Methane on Miniplant Scale. Methane 2025, Vol. 4, Page 25, 4(4), 25. [CrossRef]

- Katti, S., Willems, B., Meers, E., & Akyol, Ç. (2025). Pilot-scale anaerobic digestion of on-farm agro-residues: Boosting biogas production and digestate quality with thermophilic post-digestion. Waste Management Bulletin, 3(3), 100201. [CrossRef]

- Koch, K., Bajón Fernández, Y., & Drewes, J. E. (2015). Influence of headspace flushing on methane production in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) tests. Bioresource Technology, 186, 173–178. [CrossRef]

- Kouzi, A. I., Puranen, M., & Kontro, M. H. (2020). Evaluation of the factors limiting biogas production in full-scale processes and increasing the biogas production efficiency. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020 27:22, 27(22), 28155–28168. [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, A. A., Mikheeva, E. R., Kovalev, D. A., Katraeva, I. V., Zueva, S., Innocenzi, V., Panchenko, V., Zhuravleva, E. A., & Litti, Y. V. (2022). Feasibility Study of Anaerobic Codigestion of Municipal Organic Waste in Moderately Pressurized Digesters: A Case for the Russian Federation. Applied Sciences 2022, Vol. 12, Page 2933, 12(6), 2933. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Peng, L., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Li, Z., Yan, Y., Zhang, S., Li, M., & Xie, K. (2025). Synergetic mitigation of air pollution and carbon emissions of coal-based energy: A review and recommendations for technology assessment, scenario analysis, and pathway planning. Energy Strategy Reviews, 59, 101698. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., Liang, H., & Li, G. (2025). Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai. Processes 2025, Vol. 13, Page 2979, 13(9), 2979. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Dong, W., Yang, Y., Zhao, W., Zeng, W., Litti, Y., Liu, C., & Yan, B. (2025). The effect of CO2 sparging on high-solid acidogenic fermentation of food waste. Waste Disposal & Sustainable Energy 2025 7:1, 7(1), 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., He, P., Peng, W., Zhang, H., & Lü, F. (2024). Biochemical methane potential database: A public platform. Bioresource Technology, 393, 130111. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wachemo, A. C., Yuan, H. R., & Li, X. J. (2019). Anaerobic digestion performance and microbial community structure of corn stover in three-stage continuously stirred tank reactors. Bioresource Technology, 287, 121339. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Huang, G., Zhang, J., Han, T., Tian, P., Li, G., & Li, Y. (2025). Optimization of Anaerobic Co-Digestion Parameters for Vinegar Residue and Cattle Manure via Orthogonal Experimental Design. Fermentation 2025, Vol. 11, Page 493, 11(9), 493. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M., Zhang, H., Zhou, P., Xiong, Z., Huang, B., Peng, J., Liu, R., Liu, W., & Lai, B. (2022). Efficient activation of ferrate (VI) by colloid manganese dioxide: Comprehensive elucidation of the surface-promoted mechanism. Water Research, 215, 118243. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Guldberg, L. B., Hansen, M. J., Feng, L., & Petersen, S. O. (2023). Frequent export of pig slurry for outside storage reduced methane but not ammonia emissions in cold and warm seasons. Waste Management, 169, 223–231. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi-Eshkaftakia, M., & Mockaitis, G. (2022). Structural optimization of biohydrogen production: Impact of pretreatments on volatile fatty acids and biogas parameters. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 47(11), 7072–7081. [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A., Tsompanidis, C., Velonia, K., & Manios, T. (2023). Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste and Polylactic Acid. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 10944, 15(14), 10944. [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, A., Doosti, M. R., & Zoqi, M. J. (2024). Evaluation of upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) performance in synthetic vinasse treatment. Desalination and Water Treatment, 317, 100069. [CrossRef]

- Mekwichai, P., Chutivisut, P., & Tuntiwiwattanapun, N. (2024). Enhancing biogas production from palm oil mill effluent through the synergistic application of surfactants and iron supplements. Heliyon, 10(8), e29617. [CrossRef]

- Meybodi, M. K., Vazquez, O., Sorbie, K. S., Mackay, E. J., & Jarrahian, K. (2024). Equilibrium Modelling of Interactions in DETPMP-Carbonate System. Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE Oilfield Scale Symposium, OSS 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mihi, M., Ouhammou, B., Aggour, M., Daouchi, B., Naaim, S., El Mers, E. M., & Kousksou, T. (2024). Modeling and forecasting biogas production from anaerobic digestion process for sustainable resource energy recovery. Heliyon, 10(19), e38472. [CrossRef]

- Naji, A., Dujany, A., Guerin Rechdaoui, S., Rocher, V., Pauss, A., & Ribeiro, T. (2024). Optimization of Liquid-State Anaerobic Digestion by Defining the Optimal Composition of a Complex Mixture of Substrates Using a Simplex Centroid Design. Water 2024, Vol. 16, Page 1953, 16(14), 1953. [CrossRef]

- Naji, A., Rechdaoui, S. G., Jabagi, E., Lacroix, C., Azimi, S., & Rocher, V. (2023). Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Wastewater Sludge with Lignocellulosic Waste: A Study of Performance and Limits. Energies 2023, Vol. 16, Page 6595, 16(18), 6595. [CrossRef]

- Neri, A., Hummel, F., Benalia, S., Zimbalatti, G., Gabauer, W., Mihajlovic, I., & Bernardi, B. (2024). Use of Continuous Stirred Tank Reactors for Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Dairy and Meat Industry By-Products for Biogas Production. Sustainability (Switzerland) , 16(11), 4346. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H., Kumar, G., Yun, Y. M., Kwon, J. C., & Kim, S. H. (2018). Effect of feeding mode and dilution on the performance and microbial community population in anaerobic digestion of food waste. Bioresource Technology, 248, 134–140. [CrossRef]

- Pilarski, K., Pilarska, A. A., & Pietrzak, M. B. (2025). Biogas Production in Agriculture: Technological, Environmental, and Socio-Economic Aspects. Energies 2025, Vol. 18, Page 5844, 18(21), 5844. [CrossRef]

- Prata, A. A., Santos, J. M., Timchenko, V., & Stuetz, R. M. (2018). A critical review on liquid-gas mass transfer models for estimating gaseous emissions from passive liquid surfaces in wastewater treatment plants. Water Research, 130, 388–406. [CrossRef]

- Qian, S., Chen, L., Xu, S., Zeng, C., Lian, X., Xia, Z., & Zou, J. (2025). Research on Methane-Rich Biogas Production Technology by Anaerobic Digestion Under Carbon Neutrality: A Review. Sustainability 2025, Vol. 17, Page 1425, 17(4), 1425. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I., Díaz, I., & Fdz-Polanco, M. (2012). The role of the headspace in hydrogen sulfide removal during microaerobic digestion of sludge. Water Science and Technology : A Journal of the International Association on Water Pollution Research, 66(10), 2258–2264. [CrossRef]

- Raposo, F., Borja, R., & Ibelli-Bianco, C. (2020). Predictive regression models for biochemical methane potential tests of biomass samples: Pitfalls and challenges of laboratory measurements. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 127, 109890. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T., Cresson, R., Pommier, S., Preys, S., André, L., Béline, F., Bouchez, T., Bougrier, C., Buffière, P., Cacho, J., Camacho, P., Mazéas, L., Pauss, A., Pouech, P., Rouez, M., & Torrijos, M. (2020). Measurement of Biochemical Methane Potential of Heterogeneous Solid Substrates: Results of a Two-Phase French Inter-Laboratory Study. Water 2020, Vol. 12, Page 2814, 12(10), 2814. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Güiza, M., Peces, M., Asiain-Mira, R., Palatsi, J., & Astals, S. (2023). Microbial assessment of foaming dynamics in full-scale WWTP anaerobic digesters. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 56, 104269. [CrossRef]

- Sander, R. (2015). Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 15(8), 4399–4981. [CrossRef]

- Sani, K., Jariyaboon, R., O-Thong, S., Cheirsilp, B., Kaparaju, P., Wang, Y., & Kongjan, P. (2022). Performance of pilot scale two-stage anaerobic co-digestion of waste activated sludge and greasy sludge under uncontrolled mesophilic temperature. Water Research, 221, 118736. [CrossRef]

- Sapunov, V. N., Saveljev, E. A., Voronov, M. S., Valtiner, M., & Linert, W. (2021). The Basic Theorem of Temperature-Dependent Processes. Thermo 2021, Vol. 1, Pages 45-60, 1(1), 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N., Dallemand, J. F., & Fahl, F. (2018). Biogas: Developments and perspectives in Europe. Renewable Energy, 129, 457–472. [CrossRef]

- Schaffka, F. T. S., Behainne, J. J. R., Parise, M. R., & De Castilho, G. J. (2021). Dynamics of the Pressure Fluctuation in the Riser of a Small Scale Circulating Fluidized Bed: Effect of the Solids Inventory and Fluidization Velocity Under the Absolute Mean Deviation Analysis. Mechanisms and Machine Science, 95, 419–430. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Salhotra, S., Rathour, R. K., Solanki, P., Putatunda, C., Hans, M., Walia, A., & Bhatia, R. K. (2026). Recent developments in separation and storage of lignocellulosic biomass-derived liquid and gaseous biofuels: A comprehensive review. Biomass and Bioenergy, 204, 108417. [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, A., Limonti, C., & Curcio, G. M. (2021). Performance Evaluation of Pressurized Anaerobic Digestion (PDA) of Raw Compost Leachate. Fermentation 2022, Vol. 8, Page 15, 8(1), 15. [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, Y. A., Zhao, Z., Yoshida, A., Abudula, A., & Guan, G. (2020). Small-scale biomass gasification systems for power generation (.

- Song, S., Ginige, M. P., Cheng, K. Y., Qie, T., Peacock, C. S., & Kaksonen, A. H. (2023). Dynamics of gas distribution in batch-scale fermentation experiments: The unpredictive distribution of biogas between headspace and gas collection device. Journal of Cleaner Production, 400, 136641. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Mahdy, A., Hou, Z., Lin, M., Stinner, W., Qiao, W., & Dong, R. (2020). Air Supplement as a Stimulation Approach for the In Situ Desulfurization and Methanization Enhancement of Anaerobic Digestion of Chicken Manure. Energy & Fuels, 34(10), 12606–12615. [CrossRef]

- Stan, C., Collaguazo, G., Streche, C., Apostol, T., & Cocarta, D. M. (2018). Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion of the OFMSW: Improving Biogas Production and Startup. Sustainability 2018, Vol. 10, Page 1939, 10(6), 1939. [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, S., Nistor, M., & Liu, J. (2014). Towards eliminating systematic errors caused by the experimental conditions in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) tests. Waste Management, 34(11), 1939–1948. [CrossRef]

- Su, M. J., Luo, Y., Chu, G. W., Cai, Y., Le, Y., Zhang, L. L., & Chen, J. F. (2020). Dispersion behaviors of droplet impacting on wire mesh and process intensification by surface micro/nano-structure. Chemical Engineering Science, 219, 115593. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z., Chen, Y., Malkawi, A., Liu, Z., & Freeman, R. B. (2016). Energy saving potential of natural ventilation in China: The impact of ambient air pollution. Applied Energy, 179, 660–668. [CrossRef]

- Tran, J. T., Warren, K. J., Wilson, S. A., Muhich, C. L., Musgrave, C. B., & Weimer, A. W. (2024). An updated review and perspective on efficient hydrogen generation via solar thermal water splitting. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment, 13(4), e528. [CrossRef]

- Tzenos, C. A., Kalamaras, S. D., Economou, E. A., Romanos, G. E., Veziri, C. M., Mitsopoulos, A., Menexes, G. C., Sfetsas, T., & Kotsopoulos, T. A. (2023). The Multifunctional Effect of Porous Additives on the Alleviation of Ammonia and Sulfate Co-Inhibition in Anaerobic Digestion. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(13), 9994. [CrossRef]

- Valero, D., Montes, J. A., Rico, J. L., & Rico, C. (2016). Influence of headspace pressure on methane production in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) tests. Waste Management, 48, 193–198. [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, M., Romani, F., & Jiménez, M. (2022). Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Digestion of Pig Manure with Thermal Pretreatment: Stability Monitoring to Improve the Potential for Obtaining Methane. Processes 2022, Vol. 10, Page 1602, 10(8), 1602. [CrossRef]

- Vedat Yılmaz. (2017). Yılmaz / The Effects of Incubation and Operational Conditions on Biogas Production Karaelmas Fen Müh. Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit Üniversitesi, 7(2), 597–601.

- Wang, L., Shen, F., Yuan, H., Zou, D., Liu, Y., Zhu, B., & Li, X. (2014). Anaerobic co-digestion of kitchen waste and fruit/vegetable waste: Lab-scale and pilot-scale studies. Waste Management, 34(12), 2627–2633. [CrossRef]

- Wani, S. S., & Parveez, M. (2025). Synergistic effects of anaerobic digestion for diverse feedstocks: A holistic study on feedstock properties, process efficiency, biogas yield, and economic viability. Energy for Sustainable Development, 87, 101755. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Kovalovszki, A., Pan, J., Lin, C., Liu, H., Duan, N., & Angelidaki, I. (2019). Early warning indicators for mesophilic anaerobic digestion of corn stalk: a combined experimental and simulation approach. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2019 12:1, 12(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Ye, X., Wang, Y., & Wang, L. (2023). Methane Production from Biomass by Thermochemical Conversion: A Review. Catalysts 2023, Vol. 13, Page 771, 13(4), 771. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T., Qiang, F., Liu, G., Liu, C., Liu, Y., Ai, N., & Ma, H. (2023). Soil Quality Evaluation of Typical Vegetation and Their Response to Precipitation in Loess Hilly and Gully Areas. Forests, 14(9), 1909. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S., Gong, D., Deng, Y., Tang, R., Li, L., Zhou, Z., Zheng, J., Yang, L., & Su, L. (2021). Facile one-pot magnetic modification of Enteromorpha prolifera derived biochar: Increased pore accessibility and Fe-loading enhances the removal of butachlor. Bioresource Technology, 337, 125407. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Ma, C., Li, Z., Lu, X., Yang, Z., & Ji, X. (2020). Effect of H2S in Raw Biogas on the Performance of Biogas Upgrading with High Pressure Water Scrubbing. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B. H., Selvam, A., & Wong, J. W. C. (2017). Influence of acidogenic headspace pressure on methane production under schematic of diversion of acidogenic off-gas to methanogenic reactor. Bioresource Technology, 245, Part A, 1000–1007. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Larsen, O. C., Muhayodin, F., Hu, J., Xue, B., & Rotter, V. S. (2024). Review of anaerobic digestion models for organic solid waste treatment with a focus on the fates of C, N, and P. Energy, Ecology and Environment 2024 10:1, 10(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Nuñez, J. J., Urrútia, G., Romero-García, M., & Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [CrossRef]

- Yirong, C., Zhang, W., Heaven, S., & Banks, C. J. (2017). Influence of ammonia in the anaerobic digestion of food waste. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 5(5), 5131–5142. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xiong, W., Liu, W., Chen, X., & Yao, J. (2025). Research on Anaerobic Digestion Characteristics and Biogas Engineering Treatment of Steroidal Pharmaceutical Wastewater. Energies 2025, Vol. 18, Page 5555, 18(21), 5555. [CrossRef]

| Category | Parameter/relationship | Typical value/expression | Technical comment | References |

| Gas status | Equation of state | PVHS = ng RT | Ideal gas equation valid at moderate pressures; it is recommended to correct for water vapor when normalizing dry biogas | (Angelidaki et al., 2018) |

| Gaseous capacitance | Ce = (∂ng /∂ P)T | Ce = VHS/(RT) | Capacitance increases with dome volume; it reduces pressure variation . Flexible domes increase effective capacitance. | (Yang et al., 2024) |

| Partial pressure | Dalton's Law | Pi = yiP | Determine the equilibrium concentration using Henry's Law and the mass transfer driving force | (Su et al., 2020) |

| Henry's constant (CO2) | HCO2 (25 °C) ≈ 29 bar·m3·kmol−1; d(ln H)/d(1/T) ≈ ΔHsol/R. |

It decreases with temperature, increasing "stripping" in thermophilic. | (Sander, 2015) | |

| Henry's constant (H2S) | HH2S (25 °C) ≈ 1.0 bar·m3·kmol−1 | It exhibits high solubility. Speciation depends on pH (H2S/HS⁻ equilibrium). | (Sander, 2015) | |

| Balance | pKa, | pKa ≈ 9.25 (25 °C), decrece con T | The fractionation of free increases with pH and temperature; risk of biological inhibition at high values. | (Yirong et al., 2017) |

| Gas-liquid transfer | Gas-liquid mass transfer flow | Ni=kLa(C−C∗) | kLa ~ 10−3-10−2 s−1 in sludge with solids; intermittent agitation improves but may induce foaming. | (Prata et al., 2018) |

| Carbonate system | pKa1 /pKa2 | pKa1 ≈ 6.35; pKa2 ≈ 10.33 (25 °C) | “Stripping” raises pH and alkalinity; it interacts with the free ammonia balance. | (Sapunov et al., 2021) |

| Ranges VHS/Vtot | Laboratory vs. pilot/farm | BMP: 0.30–0.50; Pilot/farm: 0.10–0.25 | Compromise between metrological safety and structural compactness. | (Hafner et al., 2020) |

| Materials | Chemical compatibility | Stainless steel, GRP, EPDM/PTFE | Materials resistant to H₂S and NH₃; attention to permeability and thermal or UV aging of membranes. | (Pilarski et al., 2025) |

| Security | Relief and venting | Setpoint < Pdesign; non-return valve and torch. | Compliance with NFPA/ATEX regulations; CH₄ and H₂S monitoring; gas line condensate management. | (Luo et al., 2022) |

| Headspace conditions | Relevant results | Comment | Reference |

| BMP bottles: headspace 50, 90 and 180 mL (constant medium 70 mL) | Larger headspace volume means less pressure buildup; better biogas yield; relatively stable methane yield. | Methodological approach for BMP trials, showing free volume effect. | (Himanshu et al., 2017) |

| Tests with coffee residues, cocoa husks and manure; headspace overpressures > 600 mbar | In coffee waste, overpressure >600 mbar reduced methane input; for other substrates there was no adverse effect in the 600-1000 -mbar range. | Evidence that headspace pressure impacts depending on the type of substrate. | (Valero et al., 2016) |

| Headspace pressure: 12.6 psi (~0.87 bar), 6.3 psi (~0.43 bar), 3.3 psi (~0.23 bar) and ambient | Pressure ~3 -6 psi improved COD production ~22 -36%, solubles ~9 -43%, volatile solids reduction ~14 -19% and methane +10 -31% vs control. | It shows that a moderate headspace pressure favors the hydrolytic/acidogenic phase and improves methanogenesis. | (Yan et al., 2017) |

| BMP trials: headspace fraction 0.25 (40 mL in 160 mL bottle) versus 0.75 | Measurement error up to ~24% with headspace fraction 0.25; ~3% with fraction 0.75. Relative error in CH₄ increased with headspace pressure. | Evidence that free volume/headspace fraction has an impact on the accuracy of measurements. | (Hafner & Astals , 2019) |

| Headspace flushing test: N₂, N₂/CO₂ (80/20), without flushing | Flushing with 20% CO₂ increased methane production >20% in inoculum alone compared to pure N₂ flushing . | The effect of gas composition on headspace is more important than volume/pressure. | (Koch et al., 2015a) |

| Study of working volume-headspace ratio in BMP assays | They mention that headspace conditions affect biogas production; not much numerical quantification. | Recognition of the “Headspace Volume Fraction” (HSVF) as a design variable remains limited. | (Elsayed et al., 2022) |

| 225 L reactor: headspace volume 40% versus 60% | At 40% headspace, VFA production is ten times greater than at 60%; changes in microbial community. | Although focused on VFA, it shows the impact of headspace volume on microbiology and performance. | (Di Leto et al., 2024) |

| BMP review: headspace in typical tests 10 mL to 1400 mL; headspace volume fraction % varies widely | It indicates that headspace varies between ~10 to ~76% of the total volume and that this variable should be considered in design. | It reinforces that the literature considers headspace as a variable, but with scattered data. | (Cabrita & Santos, 2023a) |

| Pilot reactor 265 L: headspace volume 50.0 L, 9.5 L, 1.5 L; micro-oxygenation for H₂S removal | H₂S removal of 99% with headspace 50 L or 9.5 L; fell to ≈15% when headspace reduced to 1.5 L. | It shows that the available volume of gas-headspace impacts H₂S transfer and removal. | (Ramos et al., 2012) |

| Test with relative pressure in the range 300-800 mbar (≈0.3-0.8 bar) in biogas/hydrogen | CH₄ > 3.9 mmol/L when relative pressure between 300 and 800 mbar; indirect pressure/headspace contributions. | Although focused on hydrogen, it provides data on the relative pressure of the gas-headspace in digestion. | (Mahmoodi-Eshkaftakia & Mockaitis, 2022) |

| General review: digesting internal pressure, including headspace, is noted as a variable. | It indicates that the solubility of the gases (CO₂/CH₄) increases with pressure, which can increase CH₄ in free gas; but it also warns of negative effects of high pressure. | It supports the physical -and chemical basis of the pressure effect on headspace. | (Aworanti et al., 2023) |

| 500 mL bottles: working volumes 125, 200, 300, 400 mL → corresponding headspace 80%, 60%, 40%, 20% | Reactors with lower working volume (greater headspace) produced a higher percentage of methane (~14-23 -% more than those with greater liquid volume) | It indicates that a larger volume of free gas (greater headspace) favors biogas/methane production in BMP. | (Vedat Yılmaz, 2017) |

| Chicken manure digestion batch ; air injection into the headspace (technique variation) | H₂S removal down to ~1015 ppm and CH₄ increase by 6.4% with air injection into the headspace. | Operational example of how headspace (gas) management improves biogas quality. | (Y. Song et al., 2020) |

| Food waste fermentation bed: headspace conditions T1 (self-generated), T2 (30% CO₂ + 70% N₂), T3 (90% CO₂ + 10% N₂) | T3 (90% CO₂ in headspace) gave a soluble yield of 0.81 g COD/g VS removal, significantly higher than others | Although it does not directly analyze methane, it shows that headspace composition (CO₂) affects acid and biogas yield. | (C. Liu et al., 2025) |

| Full-scale plant review mentions that headspace conditions influence the fermentation process, including headspace volume and pressure. | He points out that, although these effects are recognized, the literature does not quantify them well; he calls for research into the relationship between headspace volume/pressure and biogas production. | It serves as an argument for the research gap on the topic. | (Kouzi et al., 2020) |

| Reactor scale/type | Type of substrate | Typical range VHS /Vtot (-) | Operating pressure (kPa) | T (°C) | Agitation | Monitoring method | CH₄ production (unit) (reported/compiled) | Material | Reference (DOI) |

| BMP (500 mL bottle) | Bovine manure | 0.25-0.35 | 101-120 | 37 | Intermittent | Displacement/manometric | ~129-366 mL CH4.g⁻¹ VS (experimental range reported in BMP literature for cow manure (compiled). | Glass | ( Hilgert et al., 2023) |

| BMP (1 L) | Anaerobic sludge | 0.30-0.40 | 101-130 | 35 | Intermittent | GC–TCD | ~100-230 mL CH₄. g⁻¹ VS (ranges reported in reviews/BMP studies ; compiled). | Plastic/PP | (Díaz-Domínguez et al., 2025a) |

| Laboratory reactor (5 L) | Food waste | 0.20-0.30 | 110-150 | 38 | Continue | NDIR | 0.6-1.2 L CH₄ · L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (experimental ranges on bench-scale) food waste reactors; compiled). | Stainless steel | ( Jiang et al., 2023) |

| Pilot reactor (20 L) | Pig slurry | 0.15-0.25 | 120-160 | 37 | Intermittent | Flow meter + GC | ~0.6-1.3 L CH4.L⁻¹. d⁻¹ (ranges obtained in pilot tests with pig slurry (compiled). | Stainless steel | (Ma et al., 2023) |

| Pilot reactor (50 L) | Plant waste | 0.20-0.35 | 110–140 | 35 | Continuous mechanics | NDIR | 0.7-1.2 L CH4.L⁻¹. d⁻¹ (reported in pilot studies of co-digestion/food waste; compiled). | Stainless steel | (Wang et al., 2014) |

| Semi-industrial reactor (200 L) | Sewage | 0.10-0.20 | 150-180 | 36 | Continue | GC + pressure | 0.5-1.0 L CH4. L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (ranges in semi-industrial plants; compiled). | Carbon steel | ( Sani et al., 2022) |

| Industrial reactor (1000 L) | Mixed substrate | 0.05-0.10 | 160-200 | 37 | Continue | NDIR + H₂S | 0.8-1.6 L CH4. L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (industrial ranges reported in reviews/case studies; compiled). | Stainless steel | ( Alqaralleh et al., 2018) |

| UASB reactor | Urban wastewater | 0.10-0.15 | 120-140 | 35 | Without agitation | Flow meter | 0.2-3.1 L CH4. L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (high variability; maximum values reported under specific conditions as vinasse; reported/compiled). | Coated concrete | (Barbosa et al., 2022) |

| CSTR reactor (2 m³) | Co-digestion | 0.08-0.12 | 150-180 | 38 | Mechanical + recirculation | GC–TCD | 1.0-1.6 L CH4. L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (ranges reported for CSTR co-digestion a pilot) scale (compiled). | Stainless steel | (Neri et al., 2024a) |

| Mesophilic reactor (5 m³) | Poultry manure | 0.10-0.15 | 160-190 | 37 | Mechanics | NDIR + flow meter | 0.9-1.3 L CH4. L⁻¹·d⁻¹ (mesophilic full-scale reports ranges; compiled ). | Fiberglass | (Díaz-Domínguez et al., 2025b) |

| Thermophilic reactor (10 m³) | Agricultural waste | 0.05-0.10 | 180-220 | 55 | Mechanics | GC + P/T | 1.2-2.2 L CH4. L⁻¹·d⁻¹ (best thermophilic performance in several studies; compiled). | Stainless steel | (Park et al., 2018) |

| Industrial reactor (20 m³) | Mixed urban sludge | 0.05-0.08 | 180-240 | 38 | Mechanics | GC + H₂S | 1.0-1.6 L CH4. L⁻¹·d⁻¹ (ranges compiled from plant case studies; compiled). | Stainless steel | ( Sani et al., 2022) |

| Reactor scale/type | Type of substrate | V HS /V tot (-) | Pressure (kPa) | CH₄ production (unit) | References |

| BMP (500 mL ) | Bovine manure | 0.25-0.35 (compiled) | ≈ 101-130 | 129-366 mL CH4.g⁻¹ VS (compiled) | (Hafner & Astals, 2019) |

| BMP (1 L) | Anaerobic sludge | 0.30-0.40 (compiled) | ≈ 101-130 | 140-230 mL CH₄.g⁻¹ VS (compiled) | (Filer et al., 2019) |

| Laboratory (5 L) | Food waste | 0.20-0.30 (reported) | 110-150 | 0.6-1.2 L CH₄.L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (reported) | ( Xiang et al., 2023) |

| Pilot (20 L) | Pig slurry | 0.15-0.25 (reported) | 120-160 | 0.9-1.3 L CH₄.L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (reported) | (Vanegas et al., 2022) |

| Pilot (50 L) | Plant residues | 0.20-0.30 (filled) | 110-140 | 0.7-1.2 L CH₄.L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (compiled) | (Maragkaki et al., 2023) |

| Semi-industrial (200 L) | Aguas residuales | 0.10-0.20 (reported) | 150–180 | 0.5-1.0 L CH₄.L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (reported) | ( Naji et al., 2023) |

| Industrial (1000 L) | Mixed substrate | 0.05-0.10 (filled) | 160-200 | 0.8-1.6 L CH₄.L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (compiled) | (Kovalev et al., 2022) |

| UASB reactor | Wastewater/vinasse | 0.10-0.15 (reported) | 120-140 | 0.2-3.1 L CH₄·L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (reported) | (Estrada-Arriaga et al., 2021) |

| CSTR (2 m³) | Co-digested | 0.08-0.12 (compiled) | 150-180 | 1.0-1.6 L CH₄.L⁻¹.d⁻¹ (compiled) | (Neri et al., 2024b) |

| Thermophilic (10 m³) | Agricultural waste | 0.05-0.10 (compiled) | 180-220 | 1.2-2.2 L CH₄.L-1.d-1 (compiled) | (Y. Liu et al., 2019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).