Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating mental health condition that can develop after exposure to traumatic events such as experiencing or witnessing threatened death, serious injury or violence (American Psychiatric Association[APA],2022; Ozer & Weiss, 2004). Those affected by PTSD experience a range of symptoms, including intrusive re-experiencing of the trauma, avoidance behaviours, negative changes in mood and cognition, and heightened arousal, which greatly affect their well-being and ability to function in daily life, as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistics Manual-5 Text Revision (DSM-5-TR; APA, 2022).

Not everyone who experiences a potentially traumatic event goes on to develop PTSD. In fact, only about 8% of individuals who encounter a potentially traumatic event, will experience ongoing symptoms of PTSD (Bistricky et al., 2017; Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Understanding the factors that contribute to the onset and maintenance of PTSD symptoms is crucial, therefore, for developing effective treatment and prevention strategies. Among many contributing factors, alexithymia and emotional regulation have gathered significant attention in recent research, due to their strong associations with impaired emotional processing, which can exacerbate trauma-related symptoms and hinder recovery (Fang et al., 2020; Kindred et al., 2024; Lilly & Valdez, 2012; Mehta et al., 2024).

Alexithymia is defined as having difficulties in recognising and expressing underlying emotions (Fang et al., 2020). Individuals with alexithymia often struggle to become aware of and label their own emotions (Difficulty Identifying Feelings), leaving them confused or unsure of what they feel. This difficulty extends to verbal expression (Difficulty Describing Feelings), which limits their capacity to communicate emotions to others and can create misunderstandings and a sense of isolation. Additionally, Alexithymics tend to focus on external events or facts (Externally Oriented Thinking) rather than their internal emotional world, adopting a more detached or pragmatic approach to emotions. In this study we examined the relationship between alexithymia and the symptoms of PTSD and considered difficulties in emotional regulation and the influence of a self-compassionate stance toward the self as potential mediators of this relationship.

1. Alexithymia and Symptoms of PTSD

Alexithymia has a clear relationship with each of the four core symptom types of PTSD. The symptoms of re-experiencing trauma include flashbacks, intrusive memories and vivid recollections of traumatic events that force individuals to confront trauma-related emotions. Alexithymia exacerbates these symptoms by interfering with attempts to process such experiences. Thus, individuals higher on alexithymia experience greater emotional dysregulation when faced with recurrent reminders of their trauma (Kooiman et al., 2002). An inability to identify and communicate these intense emotions heightens distress during re-experiencing episodes, as the emotions tied to the traumatic event resurface without the individual being able to manage them effectively (Litz et al., 2002). Alexithymic individuals also exhibit a heightened sensitivity to trauma-related stimuli because they lack the emotional vocabulary and capacity for recognition needed to process these experiences. This exacerbates their psychological impairment (Oglodek, 2022; Putica, 2024).

The second group of PTSD symptoms is focused on avoidance and involves efforts to evade trauma-related thoughts, feelings and reminders. Seeking avoidance intensifies efforts to suppress emotion expression in individuals with alexithymia (Putica et al., 2023). As alexithymic individuals struggle to identify and articulate their emotional states, avoidance reinforces these difficulties, further impairing their emotional awareness (Panayiotou et al., 2020). Hetzel-Riggin and Meads (2016) found that alexithymic individuals more often engaged in avoidant coping mechanisms, perpetuating the cycle of trauma-related emotional dysregulation. This suggests that the relationship between avoidance and alexithymia follows a feedback loop: the more an individual engages in avoidant behaviours, the less they can process their emotional experiences, reinforcing both the avoidance itself and the emotional suppression associated with alexithymia. Thus, avoidance blocks access to the emotional processing necessary for healing (Mehta et al., 2024).

Negative affect is a third type of PTSD symptom linked to alexithymia. These symptoms include persistent feelings of guilt, shame or anger that are often exacerbated in trauma survivors. Alexithymia further intensifies these negative emotional states, because the difficulties in recognising and articulating emotions experienced by alexithymic individuals increases the sense of being overwhelmed by emotion (Fang et al., 2020). This inability to manage negative affect creates a feedback loop whereby unprocessed emotions contribute to greater psychological distress and more severe PTSD symptoms (Fang et al., 2020). For instance, individuals who feel persistent guilt or shame but cannot recognise or express these emotions, can experience chronic emotional dysregulation, leading to further emotional and cognitive difficulties (Fang et al., 2020).

The final group of symptoms of PTSD, hyperarousal symptoms, involve heightened irritability, insomnia and an exaggerated startle response, and are also influenced by alexithymia. Research indicates that individuals with high levels of alexithymia exhibit persistent deficits in emotion regulation, reflected in chronically elevated negative affect that occurs independently of external stressors (Kindred et al., 2024). These individuals demonstrate a mismatch between heightened subjective emotional distress and their autonomic arousal, suggesting a dysregulated physiological-emotional response pattern (Connelly & Denney, 2007). Thus, alexithymia can amplify the physiological dysregulation associated with hyperarousal, making it more difficult for trauma survivors to manage their physical reactions to stressors (Putica et al., 2023). The inability to recognise and process emotions can prolong hyperarousal states, as unrecognised emotional triggers perpetuate these heightened physiological responses (Putica et al., 2023). Over time, this sustained hyperactivation contributes to chronic stress, sleep disturbances and increased psychological impairment, creating additional barriers to recovery (Fang et al., 2020).

2. Self-Compassion and Emotional Regulation as Mediators of the Relationship Between Alexithymia and Symptoms of PTSD

The extreme impairment caused by the symptoms of PTSD and Alexithymia has encouraged investigation of factors that can alleviate that suffering. Self-compassion and emotion regulation have been identified as multidimensional constructs that can reduce the impact of negative views of self and enhance effective coping in PTSD (Braehler & Neff, 2020; Kindred et al., 2024; Winders et al., 2022).

2.1. Self-Compassion, Alexithymia and Symptoms of PTSD

Self-compassion is generally defined as the ability to recognise one’s own suffering combined with a strong commitment to relieve that suffering (Gilbert, 2014). Neff (2003) drew upon aspects of Buddhist philosophy to identify three dimensions of compassionate self-related responding to stressful experiences: (a) invoking self-kindness and understanding rather than critical self-judgement; (b) recognising suffering as part of general human experience rather than feeling isolated; and (c) adopting a balanced approach rather than overidentifying with suffering. Thus, Neff identifies self-compassion as maintaining a delicate balance between increased compassionate and reduced uncompassionate self-responding at times of personal suffering (Neff et al., 2018). Deficits in self-compassion have been identified in relation to alexithymia and to symptoms of PTSD.

An inverse relationship is evident between alexithymia and self-compassion highlighting that the emotional difficulties inherent in alexithymia that restrict emotional awareness can obstruct the ability to engage in self-compassionate behaviours (Lyvers et al., 2020). Moreover, a systematic review by Miethe et al. (2023) established that without emotional insight, alexithymic individuals may experience heightened self-criticism and rumination, both known PTSD risk factors. Conversely, however, research on therapies that promote self-compassion shows that such interventions expand self-understanding and emotional insight and thereby reduce the influence of such alexithymic deficits (Neff, 2023).

Research also shows that self-compassion is a potential buffer against PTSD symptoms (Braehler & Neff, 2020; Zeller et al., 2015). A systematic review by Winders et al. (2022) identified 13 papers that reported correlations between self-compassion and PTSD symptoms using the DSM diagnostic criteria. Of those studies, 11 reported moderate to strong negative correlations and two found moderate negative correlations. Thus, increased self-compassion is strongly associated with lower levels of total symptoms of PTSD.

Eight studies identified by Winders et al. (2022) also examined correlations with symptom subtypes. Here relationships were more varied. Avoidance symptoms were significantly correlated with self-compassion in all studies, although the level of correlation varied from -.16 to -.65. Re-experiencing and hyperarousal symptoms were only significant in five studies (Re-experiencing; r = -.14 to -.43; Hyperarousal, r = -.21 to -.63) using DSM-IV criteria. Whereas the review by Winders et al. (2022) did not include any studies that specifically investigated the negative cognitions and mood symptom cluster of DSM-5, Brier et al. (2023) found that self-compassion was more closely associated with negative symptoms than with re-experiencing and avoidance. Thus, while total self-compassion is consistently related to PTSD symptoms, the relationships of the symptom subtypes with self-compassion are less well understood.

2.2. Emotional Regulation, Alexithymia, Self-Compassion and Symptoms of PTSD

Whereas self-compassion reflects attitudes toward the self in times of stress which serve to motivate the individual to adopt coping strategies, emotion regulation focusses on the neural cognitive and behavioural processes involved in managing emotional experiences (Kindred et al., 2024). The processing of emotions involves selection of specific strategies to influence emotions (e.g., cognitive appraisal, expressive suppression) and is influenced by the person’s capacity to regulate emotions effectively (Seligowski et al., 2015, Tull et al.,2020). Research on emotion regulation in alexithymia and PTSD shows that both alexithymia and PTSD are associated with deficits in emotion regulation.

Alexithymia is connected to disturbed emotional regulation because alexithymic individuals are more likely to employ strategies of disengagement rather than engagement with emotional stimuli (Mehta et al., (2025). Whereas engagement strategies involve further processing of emotional responses (e.g., cognitive reappraisal), disengagement strategies inhibit or divert mental processing of emotions (Scheppes et al., 2014). In alexithymia such disengagement is associated with more frequent use of strategies such as withdrawal, ignoring or denying emotional reactions, behavioural disengagement, or substance abuse (e.g., Preece et al., 2023). Thus, people higher on alexithymia avoid focussing on their negative emotions and do not integrate emotional information into mental models of emotion which would facilitate emotion regulation (Preece et al. (2018).

There is also much evidence for a relationship between disturbed emotional regulation and PTSD symptoms. Effective emotional regulation allows individuals to process traumatic experiences, helping them manage trauma-related emotions without becoming overwhelmed. Dysregulation of negative emotions such as fear, anger and sadness has been associated with the exacerbation of PTSD symptoms including hyperarousal, avoidance and re-experiencing (Kindred et al., 2024). Gratz and Roemer (2004) demonstrated significant correlations between PTSD symptoms and ineffective management of negative emotions due to the individual’s non-acceptance of negative emotional responses; difficulties maintaining goal directed behaviour and impulsivity when distressed; a perceived limited access to emotion regulation strategies; and a lack of clarity about the emotion being experienced.

PTSD symptoms can also be exacerbated by deficits in the capacity to regulate positive emotions. Weiss et al. (2018 ) found that higher levels of PTSD symptoms were evident in people who could not accept feeling positive emotions and who had difficulties implementing goal directed behaviours and controlling impulsive behaviours when experiencing positive emotions. Weiss et al. (2020) suggested that these problems with positive emotions may stem predominantly from a general fear of autonomic arousal originally associated with trauma. Thus, the heightened arousal linked to triggers of trauma can extend to other stimuli which elicit arousal, such as positive emotions, and subsequently elicit symptoms of PTSD.

Deficits in emotional regulation are also closely linked to self-compassion in determining how individuals process and respond to stress and trauma. A systematic review of studies of self-compassion and mental health conditions including trauma which include emotion regulation as a mediator was conducted by Inwood and Ferrari (2018). That review established that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with more effective emotional regulation strategies and in turn contribute to lower symptoms of PTSD and of other symptoms mental disorders including depression and stress. For example, Barlow et al., (2017) found a sequential mediation pattern such that experiences of early childhood abuse predicted higher levels of trauma appraisal which were partially mediated by self-compassion and emotion regulation in predicting symptoms of PTSD. Thus, lower self-compassion predicted greater difficulties in regulating negative emotions and subsequently higher levels of symptoms of PTSD.

3. The Current Study

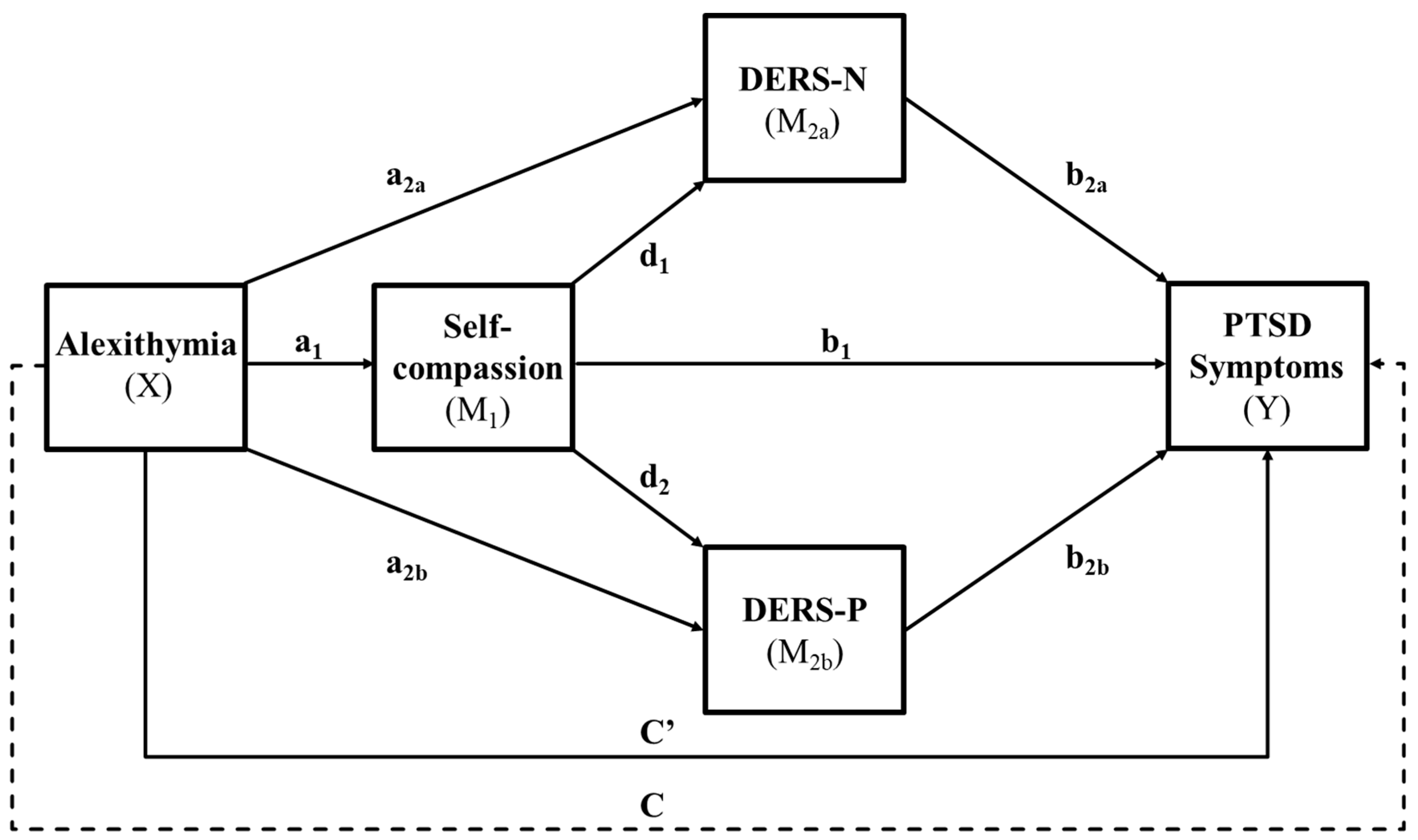

The primary aim of this study was to explore the potential pathways between alexithymia and PTSD symptoms, focusing on the possible mediating roles of self-compassion and emotional regulation, (both positive and negative). As depicted in

Figure 1, Alexithymia was expected to predict lower self-compassion, greater difficulties in regulating both negative and positive emotions and elevated symptoms of PTSD. Consistent with Barlow et al. (2017), the mediators were expected to operate in a sequential pattern with self-compassion predicting lower positive and negative emotion regulation difficulties and lower symptoms of PTSD and both forms of emotion regulation difficulty predicting higher symptoms of PTSD. As an exploratory set of analyses, we also examined how the sequential model applied to the specific PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance, negative affect and hyperarousal.

Three hypotheses and one research question were investigated. The hypotheses were:

Hypothesis 1: Alexithymia would predict higher levels of PTSD symptoms.

Hypothesis 2: Alexithymia would predict lower self-compassion and greater difficulties regulating positive and negative emotions.

Hypothesis 3: Lower self-compassion and higher disturbed emotional regulation (negative and positive) would sequentially mediate the relationship between alexithymia and PTSD symptoms. Specifically, higher levels of alexithymia would lead to lower levels of self-compassion, which in turn, would result in more disturbed negative and positive emotional regulation, ultimately contributing to higher levels of PTSD symptoms.

The research question was :

“Do self-compassion and emotional regulation difficulties (negative and positive), sequentially mediate the relationship between alexithymia and specific PTSD symptoms, including re-experiencing, avoidance, negative affect and hyperarousal?”

4. Method

4.1. Participants and Procedure

This study used a convenience sample comprised of students from Swinburne University of Technology and people from the community. Only individuals over 18 years of age capable of speaking and understanding English participated (

M = 27.2,

SD = 10.5, range 18 to 65). The final sample included 310 participants after removal of 117 people who completed less than 70% of the online questionnaire and 32 multivariate outliers. Of these 293 were Swinburne undergraduate students (75 male, 212 female, 6 non-binary) and 17 were community members (3 male, 11 female, 3 non-binary). Most participants were female (71.9%) and studying full time (65.8%) (see

Table 1). Employment status was diverse, with participants spread across full-time, part-time, casual and unemployed categories. Some reported mental health diagnoses (33.5%) and treatments (31.6%), suggesting several people had experienced substantial symptoms in response to potentially traumatic events.

Participants completed the research questionnaire online in Qualtrics and were asked to complete all tasks on one occasion taking approximately 60 minutes. Participants were recruited from social media platforms (Instagram, Facebook) and Swinburne University’s Research Experience Program (REP). They received the questionnaire link through an advertisement on their respective platforms to voluntarily participate in the study. Swinburne students enrolled in the REP received course credit after completing the survey, while no compensation was offered to community participants.

An information statement at the beginning of the survey detailed the purpose of the study, explained the implied consent process, and provided information about support services available for anyone who might have responded negatively after completing the survey. As part of the survey, participants first completed the demographic items and then were prompted to identify and recall the most potentially traumatic event they had experienced. Following this, they responded to five standardised psychometric scales. Submitting the survey was taken as implied consent from the participants to include their data in the study. Participants could withdraw at any time before submission of their survey by closing the webpage and without penalty. Participants were anonymous and non-identifiable. The project was approved by the Swinburne's Human Research Ethics Committee (#2024-780918121).

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire (PAQ; Preece et al., 2018)

The PAQ is a 24 item self-report questionnaire measuring alexithymia, a personality construct characterised by difficulties in recognising and expressing emotions. Its three subscales: Difficulty Identifying Feelings, Difficulty Describing Feelings and Externally Oriented Thinking, assessed the different facets of alexithymia. Respondents rate each statement on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) where the total score of all items ranges from 24 to 168. Higher scores indicate greater difficulties in identifying and describing emotions, with the added strength of assessing both positive and negative emotional experiences. The psychometric properties of the PAQ are firmly established, with high levels of internal consistency (α = .91), test-retest reliability (r = .84) and discriminant validity (r = .78) demonstrated by Preece et al. (2018).

4.2.2. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013)

Before completing the PCL-5, participants reflected on and described their most traumatic experience and completed the survey with that specific event in mind. The PCL-5 assessed the presence and severity of PTSD symptoms in DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022), encompassing 20 items rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Total scores range from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD symptoms. A threshold score of 33 or above is indicative of probable PTSD. The PCL-5 evaluates core PTSD symptom clusters, including re-experiencing, avoidance, negative affect and hyperarousal. The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, with high internal consistency (α = .94), good test-retest reliability (r = .82) and solid convergent (r = .74 - .85) and discriminant validity (r = .31 - .60) (Hoeboer et al., 2024; Ibrahim et al., 2018).

4.2.3. Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003)

The SCS is a 26-item self-report questionnaire that assesses individuals on six subscales of self-compassion reflecting their typical reactions to difficult experiences or feelings about themselves. These subscales: Self-Kindness, Self-Judgment, Common Humanity, Isolation, Mindfulness and Over-Identification, provide a comprehensive evaluation of self-compassionate attitudes and responses. Thirteen negatively worded items are reverse scored. Respondents rate each statement on a Likert scale 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always) and the total is the average of all 26 items. Higher scores indicated greater self-compassion. The psychometric properties of the self-compassion are robust, with high levels of internal consistency (α = .92), test-retest reliability (r = .88) and discriminant validity (r = .75) demonstrated by Cheung et al. (2024).

4.2.4. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004)

The DERS is a 36-item self-report questionnaire assessing difficulties in regulating negative emotions, with 11 of the items being reverse-scored. It comprises six subscales: Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behaviour, Impulse Control Difficulties, Lack of Emotional Awareness, Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies and Difficulty Modulating Emotions. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always) and total score of all subscales ranged from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating greater difficulties in emotion regulation. Psychometric properties of the DERS are well-established, with high levels of internal consistency (α = .93) and test-retest reliability (r = .88) and discriminant (r = .79) validity demonstrated across multiple studies (Bjureberg et al., 2016; Hallion et al., 2018).

4.2.5. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive (DERS – P; Weiss et al., 2019)

The DERS – P is a 13 item self-report questionnaire adapted from the original DERS (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) to assess difficulties specifically related to regulating positive emotions. It includes three subscales: Nonacceptance of Positive Emotions, Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behaviour When Experiencing Positive Emotions and Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies for Positive Emotions. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), where the total score of all subscales ranges from 13 to 65. Higher scores indicate greater difficulties in regulating positive emotions. The psychometric properties of the DERS-P are robust, with high levels of internal consistency (α = .94), test-retest reliability (r = .87) and discriminant validity (r = .76) has been demonstrated across multiple studies (Hallion et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2019).

4.3. Data Analysis

This study employed a cross-sectional design. Cases with 30% or more missing data were excluded (n=117). As all other participant data showed less than 5% missing, mean substitution was used for any other missing data. A power analysis showed that a total sample size of at least 162 participants was required to attain a power of 0.8 in the Percentile Bootstrap Test under the HH condition (.26), (Fritz & MacKinnon (2007).

The data were screened for univariate and multivariate outliers. Univariate outliers were identified by examining standardised z-scores, with values exceeding ±3.29 deemed extreme and subsequently removed (one outlier was detected and excluded). Multivariate outliers were detected through Mahalanobis distance within SPSS regression analysis, with cases exceeding the chi-square distribution's critical value of 7.815 (for four independent variables at a significance level of .05) also being excluded (32 outliers detected and excluded).

Following the outlier assessment, the data were examined for skewness and kurtosis. Significant deviations from normality were taken to be indicated by skewness and kurtosis values exceeding ±2 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Overall, the data displayed normality, indicating that the distribution of the data points closely followed a normal distribution curve. Therefore, no data transformations were required. Pearson product-moment correlations evaluated the strength and direction of the linear relationships among all measures, with the Pearson correlation coefficient calculated using SPSS. Conducted homoscedasticity checks also appeared satisfactory, as all the scatter plot points randomly and evenly were dispersed around the zero-horizontal line, showing no clear pattern.

A serial mediation analysis using PROCESS Version 4.2 (Model 81) from Hayes (2022) in SPSS was conducted to test direct and indirect effects of a predictor (X - alexithymia) on an outcome variable (Y - PTSD Symptoms) through multiple mediators: self-compassion (M

1) and emotional regulation (Disturbed Negative Emotion Regulation (M

2a) and Disturbed Positive Emotion Regulation (M

2b)) (see

Figure 1, p. 9). The analysis employed 5000 bootstrapped samples and percentile-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to assess the indirect effects of predictor variables on the outcome variable via the mediator variables. Direct effects were deemed significant when the alpha level was below .05, while indirect effects were considered significant if the confidence intervals did not cross zero (Hayes, 2022).

5. Results

The descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the variables are provided in

Table 2.

Table 2 shows that there were significant correlations among all variables and that all measures showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .810 to.957). Higher alexithymia traits were strongly correlated with higher levels of PTSD symptoms, and with lower levels of self-compassion, Participants with high alexithymia traits also experienced more difficulties in regulating both negative and positive emotions.

5.1. Serial Mediation Model for Total PTSD Symptoms

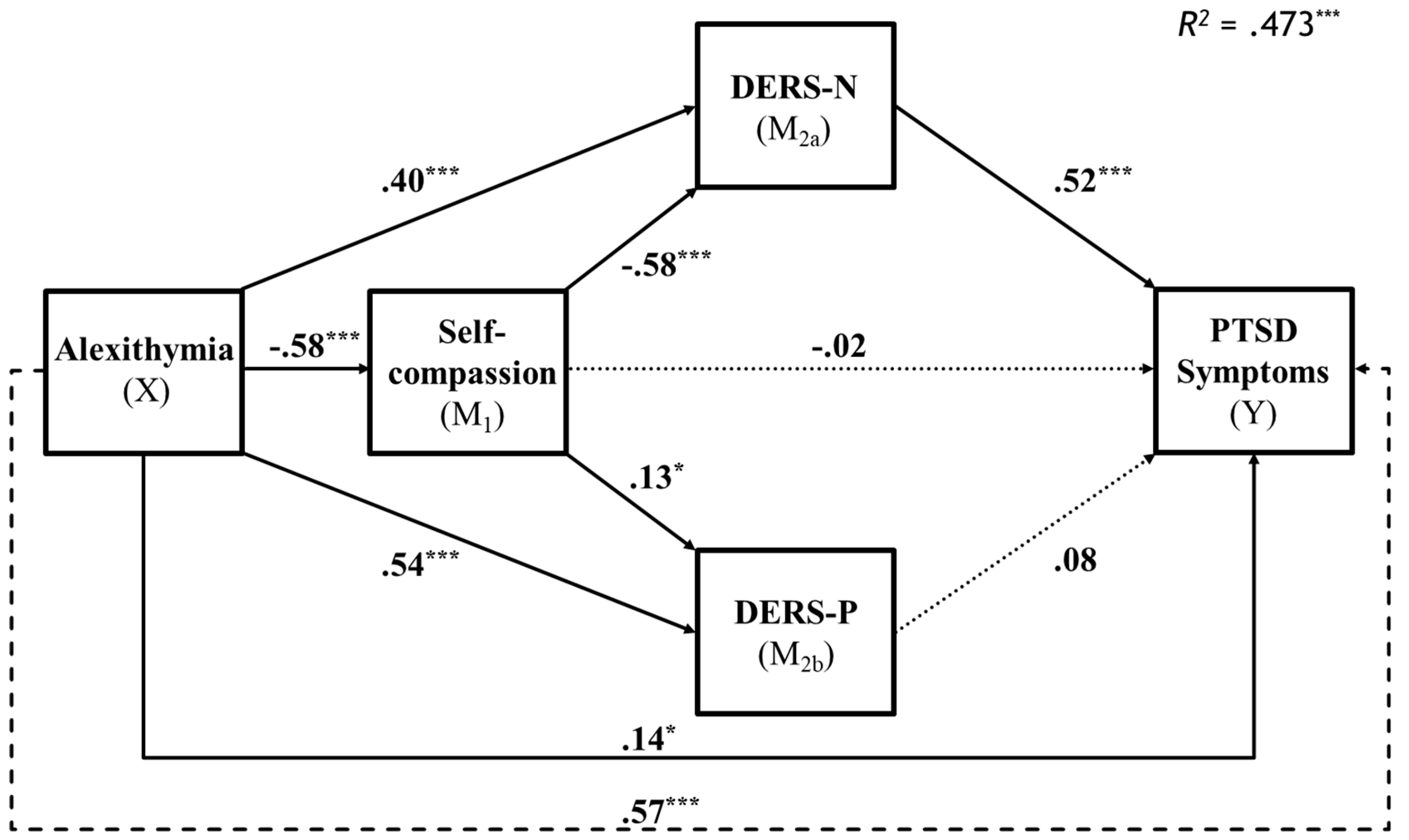

A serial mediation model was performed using PROCESS Version 4.2 (Model 81) from Hayes (2022) in SPSS, with alexithymia as the predictor, self-compassion, emotional regulation (positive and negative) as the mediators and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms as the dependent variable. Results are illustrated in

Figure 2.

The overall model was significant, R = .69, F(4, 305) = 68.38, p < .001, explaining R2 = 47.28% of the variance in PTSD symptoms. Alexithymia directly predicted PTSD symptoms (B = .09, SE = .04, p = .02).

The results supported the first hypothesis, showing a significant positive relationship between alexithymia and PTSD symptoms, with the total effect model indicating a direct effect of alexithymia on PTSD symptoms (B = .14, SE = .04, p = .02), independent of mediators. There was also support for the second hypothesis that alexithymia would significantly predict lower self-compassion (B = -.58, SE = .001, p < .001) and greater difficulties in regulating both negative (B = .40, SE = .03, p < .001) and positive emotions (B = .54, SE = .02, p < .001), demonstrating its strong influence on emotional regulation and self-compassion.

There was partial support the third hypothesis, with the sequential mediation pathway through self-compassion and negative emotion regulation being significant (B = .17, BootSE = .04, BootCI [.11, .25]), indicating that higher alexithymia leads to lower self-compassion, greater negative emotion regulation difficulties and increased PTSD symptoms. However, the pathway through positive emotion regulation was not significant (B = -.01, BootSE = .01, BootCI [-.02, .002]). Additionally, while self-compassion did not show a significant mediating effect, its influence on negative emotional regulation, suggests that negative emotional regulation was the mechanism whereby self-compassion indirectly determines PTSD symptoms.

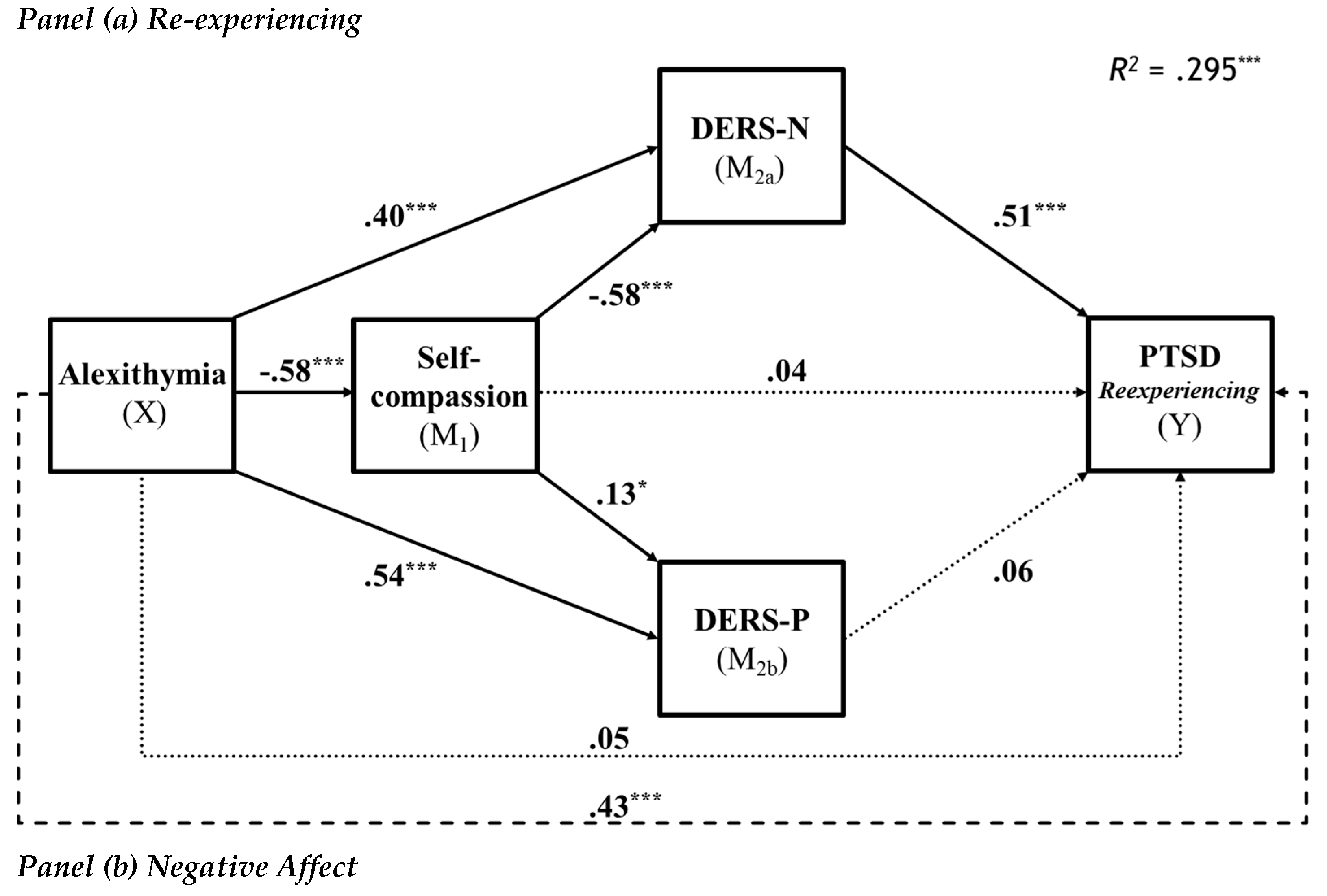

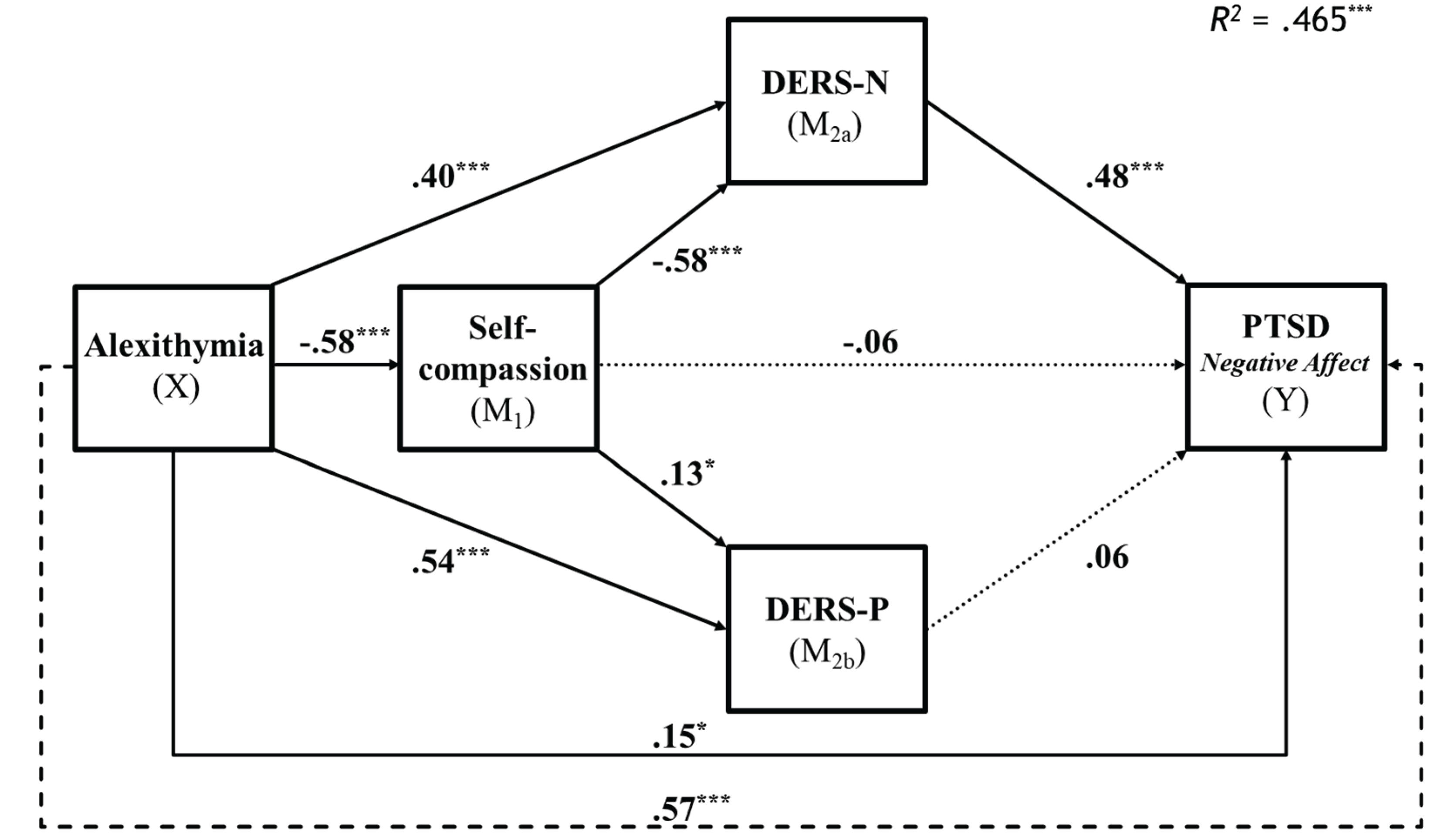

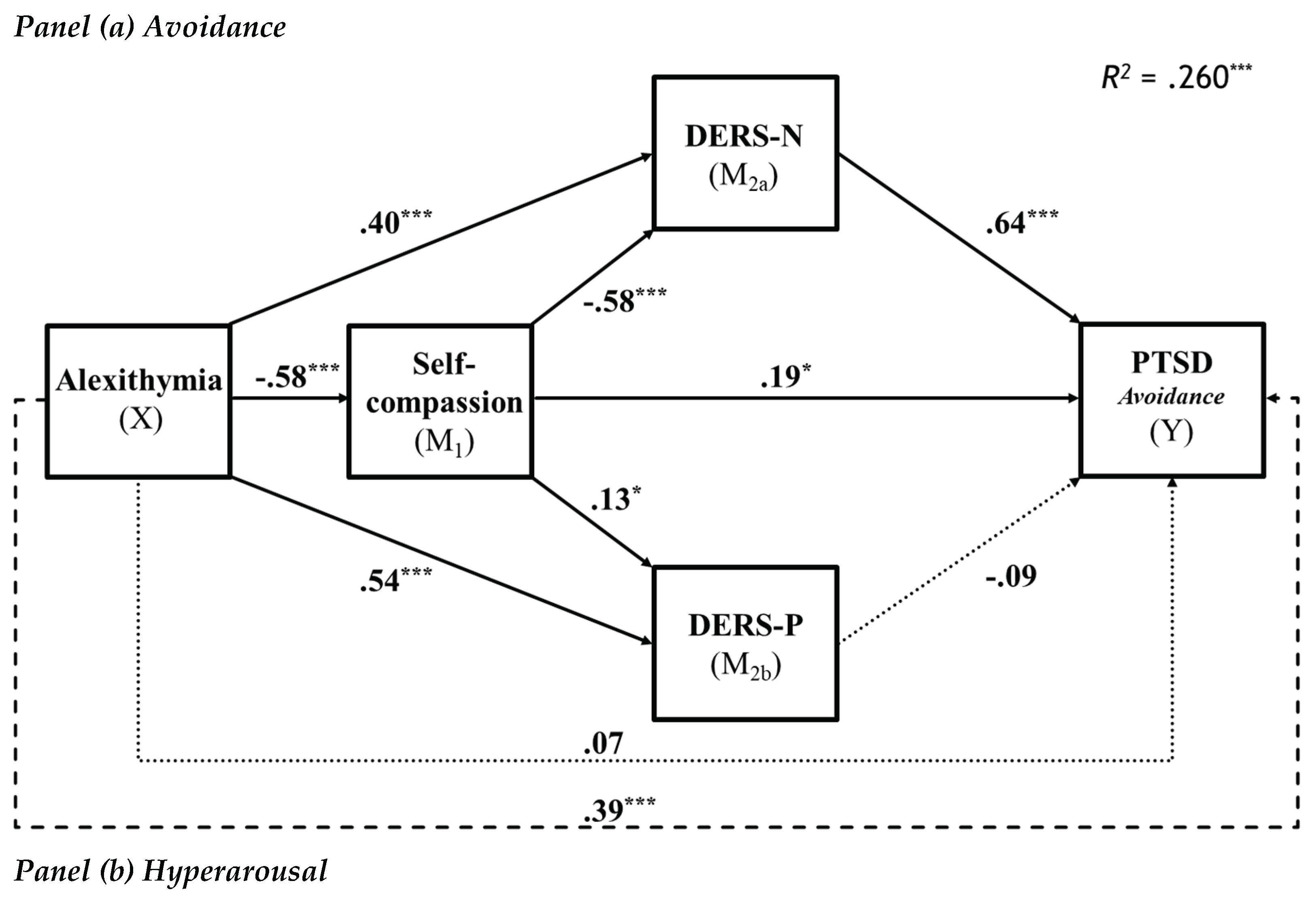

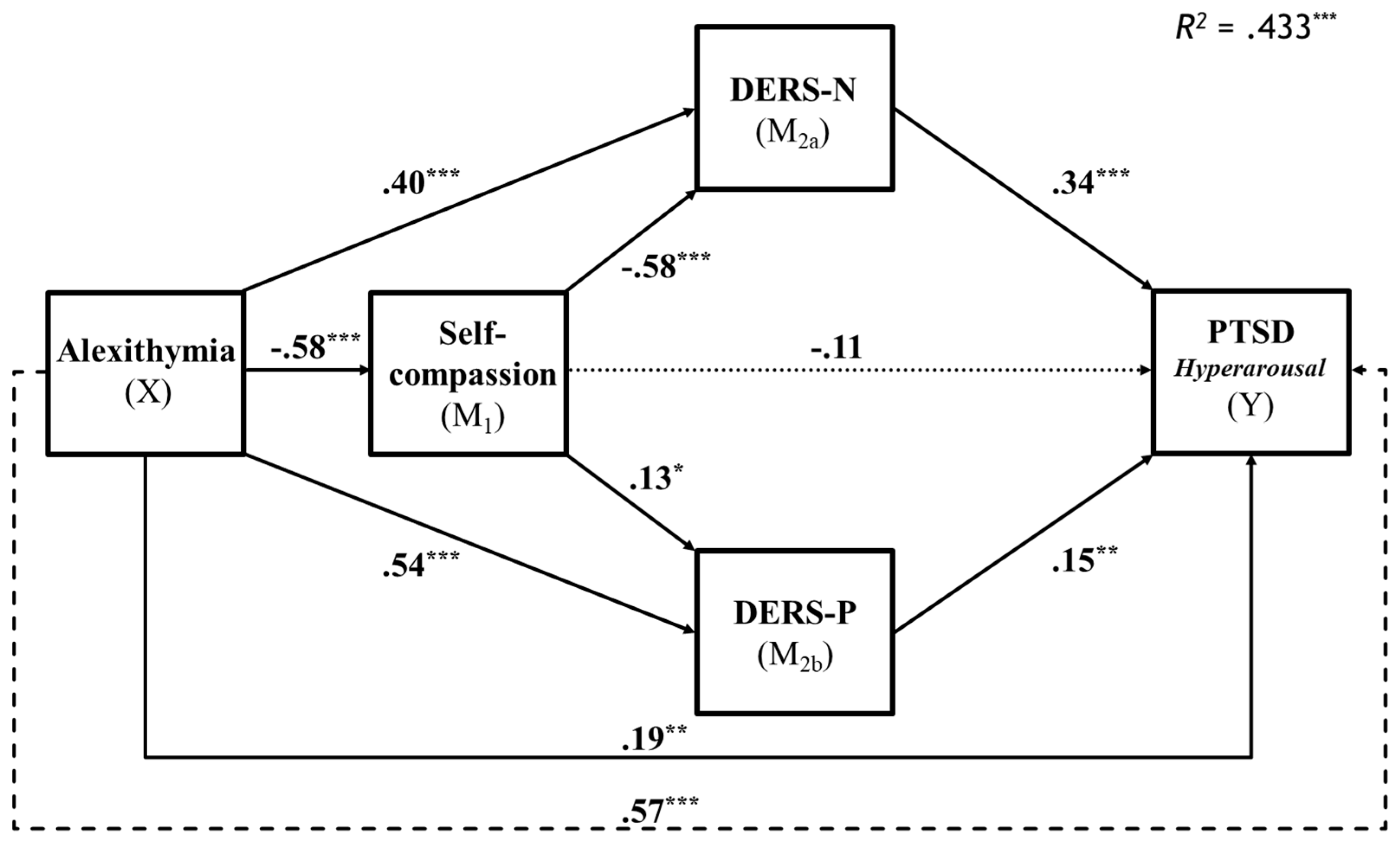

5.2. Serial mediation Analysis of PTSD Specific Symptom Subtypes

To explore the research question, the mediation analysis was repeated for each of the symptom subtypes of re-experiencing, avoidance, negative affect and hyperarousal. Analyses of the specific symptoms showed that Re-experiencing and negative affect showed similar results to those for total PTSD symptoms (see

Figure 3) with the exception that the effect of alexithymia on re-experiencing symptoms was fully rather than partially mediated. However, the PTSD symptoms of avoidance and hyperarousal showed other significant pathways (see

Figure 4).

5.3. Mediation Analyses for Re-Experiencing and Negative Affect

The overall model for re-experiencing was significant, R = .54, F(4, 305) = 31.97, p < .001, explaining R2 = 29.54% of the variance in re-experiencing. Similarly, the overall model predicting negative affect was significant, R = .68, F(4, 305) = 66.26, p < .001, explaining R2 = 46.5% of the variance in negative affect. Alexithymia did not directly predict re-experiencing and so was fully mediated (B = .008, SE = .01, p = .52). In contrast alexithymia remained a significant predictor of negative affect and so was partially mediated(B = .04, SE = .02, p = .02).

5.4. Mediation Analyses for Avoidance and Hyperarousal

The overall model for avoidance was significant, R = .51, F(4, 305) = 26.82, p < .001, explaining R2 = 26.02% of the variance in avoidance. Equally, the overall model predicting hyperarousal was significant, R = .66, F(4, 305) = 58.33, p < .001, explaining R2 = 43.34% of the variance in hyperarousal. Alexithymia did not directly predict avoidance (B = .006, SE = .006, p = .32), however, it was a significant predictor of hyperarousal (B = .04, SE = .01, p = .005). Unlike the results for total PTSD symptoms, and all other symptoms of PTSD, self-compassion had a significant pathway to Avoidance symptoms and thus mediated the effects of alexithymia. Interestingly, this was a positive pathway and so increased self-compassion predicted greater avoidance. As for total PTSD symptoms self-compassion was involved in the same serial mediation pathway through negative emotional regulation in predicting avoidance. In the case of PTSD symptoms of hyperarousal, the general pattern of findings was the same as for total symptoms with the addition of a significant serial mediation pathway through difficulties in regulating positive emotional experiences.

6. Discussion

The study was conducted to investigate a model of the relationship between Alexithymia and symptoms of PTSD and the potential mediating roles of self-compassion and emotion regulation (both positive and negative). As an exploratory investigation, this model was also tested in relation to the four subtypes of PTSD symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal and negative emotion). Our findings were broadly as expected and generally supported the model we developed. Alexithymia was confirmed as a significant predictor of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms, both directly and through various indirect pathways. As hypothesised (hypothesis 1), higher alexithymia directly predicted higher levels of total PTSD symptoms. Also as hypothesised (hypothesis 2), higher alexithymia also predicted lower self-compassion and greater difficulties in regulating negative and positive emotions. In partial support of hypothesis 3, partial sequential mediation was evident for difficulties regulating negative emotions with higher alexithymia predicting lower self-compassion and lower self-compassion predicting greater difficulties with negative emotions which then predicted higher symptoms of PTSD. However, contrary to prediction, sequential mediation was not evident for difficulties with positive emotion regulation as the pathway from difficulties with positive emotions to total PTSD symptoms was non-significant. Further, self-compassion did not directly predict total PTSD symptoms but influenced total PTSD symptoms through its prediction of difficulties in negative emotion regulation. The results thus highlight the importance of self-compassion and negative emotional regulation in translating alexithymia’s effects onto PTSD symptoms.

The exploration of the relationship between alexithymia and different PTSD symptoms subtypes revealed some variability in how emotional regulation difficulties and self-compassion mediated the effects of alexithymia. Whereas the prediction of negative affect symptoms duplicated the pattern of prediction of total symptoms, differences were evident for the other symptom types. For symptoms of re-experiencing and avoidance, alexithymia was fully rather than partially mediated by self-compassion and difficulties regulating negative emotions. For re-experiencing the significant mediation pathways remained the same as for total symptoms. For the prediction of avoidance symptoms, the model also showed full mediation of alexithymia via self-compassion and difficulties in negative emotions. However, in this model an additional individual mediation pattern was significant for self-compassion. Finally, for prediction of hyperarousal, while again there was partial sequential mediation for self-compassion and difficulties regulating negative emotions, sequential mediation was also evident for difficulties regulating positive emotions. In this discussion we consider the theoretical and clinical implications of the findings for total PTSD symptoms and for the four symptom subtypes.

6.1. Alexithymia and PTSD Symptoms

Our findings clearly show that alexithymia is a direct and indirect predictor of PTSD symptoms via self-compassion and difficulties of regulating emotion. However, the analysis of the symptom types showed that it’s direct prediction was confined to negative emotions and hyperarousal symptoms. In contrast for re-experiencing and avoidance symptoms the effects of alexithymia were fully determined by the mediators. This may relate to the persistent nature of the internal distress caused by disturbed negative emotions and hyperarousal (Putica et al., 2021) which contrasts with the more situationally triggered nature of the symptoms of re-experiencing and avoidance (APA, 2022). The difficulties identifying describing and expressing negative emotions and hyperarousal are thus directly involved in exacerbating these symptoms for much of the person’s daily life.

In contrast to negative emotions and hyperarousal, re-experiencing involves intense focused affect linked to the associated traumatic event and avoidance involves behavioural cognitive and emotional attempts to escape that distress. These consciously mediated experiences focused on triggered reminiscence of the traumatic event may be more linked to the specific problems of regulating negative emotions including non-acceptance of the negative emotion and difficulties in maintaining goal directed behaviour when distressed (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Kindred et al., 2024). Similarly, the elements of self-compassion such as overidentification with suffering or keeping a balanced mind (mindfulness) may play an important role in determining the influence of alexithymia on these symptoms. These possibilities clearly warrant further attention in future work.

6.2. Self-Compassion and PTSD Symptoms

Contrary to expectations self-compassion was not found to directly predict total symptoms of PTSD. Instead, its influence on total symptoms of PTSD was indirect, This is surprising given that earlier research shows a predictive relationship between self-compassion and PTSD symptoms (Braehler & Neff, 2020; Winders et al., 2022). It is possible that the lack of a direct relationship may reflect different predictive strengths of PTSD symptoms among the components of self-compassion. MacBeth and Gumley (2012) demonstrated that the components comprising reduced uncompassionate behaviour (self-judgment, isolation and overidentifying with feelings) were more strongly related to symptoms of depression and anxiety than were the compassionate components (self=kindness, common humanity and mindfulness). This also seems to be the case for other symptom types such as social anxiety and thus combining the two forms of symptoms can mask relationships with predictor variables.(McBride et al., 2022). As we used the total score for mindfulness to predict PTSD symptoms it may be that particular aspects of self-compassion may be direct predictors of PTSD symptoms, but that overall self-compassion was non-significant.

The analysis of the PTSD symptom subtypes revealed a surprising finding for self-compassion as a predictor of avoidance symptoms. For all other symptom subtypes self-compassion was a non-significant direct predictor and its influence was indirect through its negative prediction of difficulties in emotion regulation. What was unexpected was that while it was negatively correlated with avoidance in the zero order correlations, self-compassion had a positive predictive relationship on avoidance symptoms. Thus, greater self-compassion predicted more avoidance. Similarly to the earlier discussion, a possibility is that certain components of self-compassion may be the main contributors to this result. For example, it may be that low levels of critical self-judgment and higher self-kindness may allow the person to accept avoidance as a form of self-care. Clearly, further research is needed to fully understand this finding.

6.3. Difficulties of Emotion Regulation and PTSD Symptoms

Difficulties in regulating negative emotions was a strong predictor of all aspects of PTSD and showed significant mediation pathways for alexithymia and self-compassion in all analyses. This aligns with the general pattern of prediction for self-compassion and psychological symptoms reported by Inwood and Ferrari’s (2018). Thus, self-compassion appears to act more as a motivational approach to problem solving (Bates et al., 2021; Finlay-Jones et al., 2015) and this negatively predicts specific problems with emotional regulation (e.g., impulsivity, perceived limited access to strategies). This is also consistent with the tendency for alexithymic people to utilise less effective disengagement strategies in responding to negative emotions (e.g., denial, distraction) and o underutilise effective engagement strategies (e.g., problem solving) identified by Preece et al. (2023). Taken together this suggests that difficulties I regulating negative emotions is an important mechanism that helps determine the effects of alexithymia and self-compassion on symptoms of PTSD.

In contrast to difficulties with negative emotion regulation, difficulties in positive emotional regulation did not significantly mediate the relationship between alexithymia and overall PTSD symptoms or symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance or negative emotions. However, along with difficulties managing negative emotions, difficulties in managing positive emotions significantly predicted hyperarousal symptoms. Moreover, they also acted as an individual and serial mediator of the effects of alexithymia and self-compassion on those symptoms. This finding aligns with the suggestion by Weiss et al. (2020) that problems in accepting positive emotions, and in implementing goal directed behaviours and avoiding impulsive actions when experiencing such emotions relate to a general fear of elevated arousal. In PTSD this fear is heightened when arousal is triggered by traumatic events and is connected to elevated resting arousal experienced through symptoms such as feeling of super alert, jumpy or easily startled states (DSM-5-TR, 2022). Thus, our data suggest that whereas difficulties in regulating negative emotions are involved in the prediction of all PTSD symptom types, difficulties in regulating positive emotions have a unique influence on symptoms of hyperarousal.

6.4. Clinical Implications

The findings of this study have several important clinical implications for the treatment of individuals with symptoms of PTSD. First, the study highlights the critical role of alexithymia in the maintenance of PTSD symptoms and likely in its development. Clinicians should be aware that individuals with alexithymia may have difficulty identifying and expressing emotions, which can impair their ability to process trauma. Therapeutic approaches, such as trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), may need to be adapted to focus more explicitly on emotional awareness and expression, helping clients with alexithymia improve their emotional literacy. Interventions like emotion-focused therapy (EFT) and mindfulness-based therapies may be beneficial in helping clients develop the ability to recognise and name their emotions, which is a critical first step in trauma recovery.

Second, the findings underline the importance of targeting negative emotional regulation difficulties in therapy. Since negative emotion dysregulation is a key mediator between alexithymia and symptoms of PTSD, therapeutic strategies that enhance emotional regulation skills are essential. Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), which emphasises emotional regulation, distress tolerance and acceptance, may be particularly effective for clients with high levels of alexithymia and PTSD symptoms. DBT’s focus on managing negative emotions can help reduce the intensity of trauma-related symptoms, such as re-experiencing and avoidance.

Furthermore, the significant role of self-compassion in the serial mediation pathway suggests that fostering self-compassion could be an effective therapeutic target. Interventions that enhance self-compassion, such as Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT) or Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC), may be beneficial in reducing the emotional dysregulation associated with alexithymia and, subsequently, PTSD symptoms. Increasing self-compassion can help clients become more accepting of their emotional experiences, reducing the negative impact of emotional dysregulation.

Finally, our finding that positive emotional regulation is particularly significant for hyperarousal symptoms suggests a need for clinicians to address both positive and negative emotional regulation in treatment. Techniques such as positive psychology interventions, which encourage clients to identify and appreciate positive emotions, could be incorporated to help manage hyperarousal. Helping clients cultivate positive emotional regulation skills could reduce physiological hyperactivity, leading to better overall trauma recovery.

6.5. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The present study is not without limitations. First, the use of a convenience sample, predominantly comprised of female undergraduate students, limits the generalisability of the results, as this sample may not represent broader populations, particularly those with higher levels of trauma exposure or different demographic backgrounds. Future research is needed to examine the relationships we found in more diverse and representative community samples. Research on clinical samples and occupational groups exposed to traumatic experiences (e.g., health care workers, defence force personnel or police) would also help determine the generalisability of our data.

A second limitation is our use of a cross-sectional design. The present mediation analysis has identified theoretically meaningful patterns of association and mediation amongst the variables. Longitudinal data is required, however, to confirm the causal relationships among alexithymia, emotional regulation difficulties, self-compassion and PTSD symptoms. Treatment outcome studies will also be important in establishing how these variables change over time and contribute to trauma recovery. As some lines of research suggest that increased alexithymia can also be an outcome of PTSD (Kindred et al., 2024) cross lagged analyses would help determine the nature of the reciprocal relationship between alexithymia and PTSD symptoms.

A final limitation of this study relates to our reliance on self-report measures. Although the measures used in this study are well-validated and relatively free of social desirability concerns, they are subject to the limitations of self-report measures. Inclusion of interview measures of PTSD symptoms and physiological assessments would increase confidence in the findings. Qualitative analysis of interview data could also help to elucidate the experience of difficulties in regulating negative and positive emotions and the lived experience of self-compassionate self-responding in the context of alexithymia and PTSD symptoms.

In conclusion, the findings of this study contribute to the growing body of literature that positions alexithymia as a significant predictor of PTSD symptoms, primarily through its impact on emotional regulation. In our study we also found self-compassion plays a critical role in a serial mediation pathway, influencing PTSD symptoms through its effects on emotional regulation difficulties. The data also highlight the complex role of positive emotional regulation, particularly in mitigating hyperarousal symptoms, suggesting that both positive and negative emotional regulation need to be addressed in trauma-focused therapies. The importance of addressing the emotional dysregulation associated with alexithymia in clinical practice is further emphasised, as targeting both emotional regulation and self-compassion could improve therapeutic outcomes for individuals struggling with trauma. By integrating interventions that enhance emotional awareness and self-compassion, clinicians may better address the broad spectrum of trauma-related symptoms, ultimately improving recovery outcomes for alexithymia patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, George Fedorov and Glen William Bates; Methodology, George Fedorov and Glen William Bates; Software, Glen William Bates; Validation, George Fedorov and Glen William Bates; Formal analysis, George Fedorov and Glen William Bates; Investigation, George Fedorov; Resources, Glen William Bates; Data curation, Glen William Bates; Writing – original draft, George Fedorov and Glen William Bates; Writing – review & editing, George Fedorov and Glen William Bates; Supervision, Glen William Bates; Project administration, Glen William Bates.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The project was approved by the Swinburne's Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol code #2024-780918121 and date of approval is 21/03/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. In text rev., 5th ed.; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, M. R.; Turow, R. E. G.; Gerhart, J. Trauma appraisals, emotion regulation difficulties, and self-compassion predict posttraumatic stress symptoms following childhood abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect 2017, 65, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, G. W.; Elphinstone, B.; Whitehead, R. Self-compassion and emotional regulation as predictors of social anxiety. Psychology and Psychotherapy 2021, 94(3), 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bistricky, S. L.; Gallagher, M. W.; Roberts, C. M.; Ferris, L.; Gonzalez, A. J.; Wetterneck, C. T. Frequency of interpersonal trauma types, avoidant attachment, self-compassion, and interpersonal competence: A model of persisting posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2017, 26(6), 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjureberg, J.; Ljótsson, B.; Tull, M. T.; Hedman, E.; Sahlin, H.; Lundh, L. G.; Bjärehed, L.-G.; DiLillo, J.; Messman-Moore, T.; Gratz, K. L. Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: the DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2016, 38, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braehler, C.; Neff, K. Self-compassion in PTSD. In Emotion in posttraumatic stress disorder; Tull, M. T., Kimbrel, N. A., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 567–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brier, Z.M.F.; Burt, K.B.; Legrand, A.C.; Price, M. An examination of the heterogeneity of the relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder, self-compassion and gratitude. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 2023, 30, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W.; Cooper-Thomas, H. D.; Lau, R. S.; Wang, L. C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2024, 41(3), 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, M.; Denney, D. R. Regulation of emotions during experimental stress in alexithymia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2007, 62(6), 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A. N.; Vasco, A. B.; Watson, J. C. Alexithymia and emotional processing: A mediation model. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2017, 73(9), 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Chung, M. C.; Wang, Y. The impact of past trauma on psychological distress: The roles of defence mechanisms and alexithymia. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay-Jones, A. L.; Rees, C. S.; Kane, R. T. Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among Australian psychologists: Testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modeling. PLOS ONE 2015, 10(7), e0133481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M. S.; MacKinnon, D. P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science 2007, 18(3), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2014, 53(1), 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K. L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallion, L. S.; Steinman, S. A.; Tolin, D. F.; Diefenbach, G. J. Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and its short forms in adults with emotional disorders. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzel-Riggin, M. D.; Meads, C. L. Interrelationships among three avoidant coping styles and their relationship to trauma, peritraumatic distress, and posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2016, 204(2), 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeboer, C. M.; Karaban, I.; Karchoud, J. F.; Olff, M.; van Zuiden, M. Validation of the PCL-5 in Dutch trauma-exposed adults. BMC Psychology 2024, 12, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Ertl, V.; Catani, C.; Ismail, A. A.; Neuner, F. The validity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, E.; Ferrari, M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 2018, 10(2), 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D. G.; Resnick, H. S.; Milanak, M. E.; Miller, M. W.; Keyes, K. M.; Friedman, M. J. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2013, 26(5), 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindred, R.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Bates, G. Understanding emotion regulation in PTSD and Complex PTSD. In Understanding Emotional Regulation: New Research; Collins, F., Ed.; Nova; New York, 2024; pp. 47–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, C. G.; Spinhoven, P.; Trijsburg, R. W. The assessment of alexithymia: A critical review of the literature and a psychometric study of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2002, 53(6), 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M. M.; Valdez, C. E. The unique relationship of emotion regulation and alexithymia in predicting somatization versus PTSD symptoms. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2012, 21(7), 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, B. T.; Litz, B. T.; Gray, M. J. Emotional numbing in posttraumatic stress disorder: Current and future research directions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2002, 36(2), 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyvers, M.; Randhawa, A.; Thorberg, F. A. Self-compassion in relation to alexithymia, empathy, and negative mood in young adults. Mindfulness 11 2020, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeth, A.; Gumley, A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review 2012, 32(6), 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, N. L.; Bates, G. W.; Elphinstone, B.; Whitehead, R. Self-compassion and social anxiety: The mediating effect of emotion regulation strategies and the influence of depressed mood. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 2022, 95(4), 1036–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Moeck, E.; Preece, D. A.; Koval, P.; Gross, J. J. Alexithymia and emotion regulation: The role of emotion intensity. Affective Science 2024, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miethe, S.; Wigger, J.; Wartemann, A.; Fuchs, F. O.; Trautmann, S. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and its association with rumination, thought suppression and experiential avoidance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2023, 45(2), 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity 2003, 2(3), 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology 2023, 74(1), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. D.; Long, P.; Knox, M. C.; Davidson, O.; Kuchar, A.; Costigan, A.; Williamson, Z.; Rohleder, N.; Toth-Kiraly, I.; Breines, J. G. The forest and the trees: Examining the association of self-compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self and Identity 2018, 17(6), 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogłodek, E. A. Alexithymia and emotional deficits related to posttraumatic stress disorder: an investigation of content and process disturbances. Case Reports in Psychiatry 2022, 2022(1), 7760988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, E. J.; Weiss, D. S. Who develops posttraumatic stress disorder? Current Directions in Psychological Science 2004, 13(4), 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou, G.; Leonidou, C.; Constantinou, E.; Michaelides, M. P. Self-awareness in alexithymia and associations with social anxiety. Current Psychology 2020, 39, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.; Becerra, R.; Robinson, K.; Dandy, J.; Allan, A. The psychometric assessment of alexithymia: Development and validation of the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences 132 2018, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Mehta, A.; Petrova, K.; Sikka, P.; Becerra, R.; Gross, J. Alexithymia and emotion regulation. Journal of Affective Disorders 324 2023, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putica, A. Examining the role of emotion and alexithymia in cognitive behavioural therapy outcomes for posttraumatic stress disorder: Clinical implications. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist 2024, 17, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putica, A.; Van Dam, N. T.; Steward, T.; Agathos, J.; Felmingham, K.; O'Donnell, M. Alexithymia in post-traumatic stress disorder is not just emotion numbing: Systematic review of neural evidence and clinical implications. Journal of Affective Disorders 278 2021, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putica, A.; O'Donnell, M. L.; Felmingham, K. L.; Van Dam, N. T. Emotion response disconcordance among trauma-exposed adults: the impact of alexithymia. Psychological Medicine 2023, 53(12), 5442–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putica, A.; Van Dam, N. T.; Felmingham, K.; Lawrence-Wood, E.; McFarlane, A.; O’Donnell, M. Interactive relationship between alexithymia, psychological distress and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomology across time. Cognition and Emotion 2024, 38(2), 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheppes, G.; Scheibe, S.; Suri, G.; Radu, P.; Blechert, J.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation choice: A conceptual framework and supporting evidence. Journal of experimental Psychology: General 2014, 143((1)), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligowicki, A.; Miron, L.R.; Ocutt, H.K. Relations among self-compassion, PTSD symptoms and psychological health in a trauma-exposed sample. Mindfulness 6(5) 2015, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G.; Fidell, L. S. Using multivariate statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tull, M. T.; Vidaña, A. G.; Betts, J. E. Emotion regulation difficulties in PTSD. In Emotion in posttraumatic stress disorder: Etiology, assessment, neurobiology, and treatment; Tull, M. T., Kimbrel, N. A., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press, 2020; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W.; Litz, B. T.; Keane, T. M.; Palmieri, P. A.; Marx, B. P.; Schnurr, P. P. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Centre for PTSD. 2013. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weiss, N. H.; Gratz, K. L.; Lavender, J. M. Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification 2015, 39(3), 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N. H.; Dixon-Gordon, K. L.; Peasant, C.; Sullivan, T. P. An examination of the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2018, 31(5), 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N. H.; Darosh, A. G.; Contractor, A. A.; Schick, M. M.; Dixon-Gordon, K. L. Confirmatory validation of the factor structure and psychometric properties of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale-positive. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2019, 75(7), 1267–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N.H.; Forkus, S.R.; Contractor, A.A.; Dixon-Gordon, K.L. The interplay of negative and positive emotion dysregulation on mental health outcomes among trauma exposed community individuals. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research and Policy 12(3) 2020, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winders, S. J.; Murphy, O.; Looney, K.; O'Reilly, G. Self-compassion, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2022, 27(3), 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.; Yuval, K.; Nitzan-Assayag, Y.; Bernstein, A. Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: Longitudinal study of at-risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2015, 43, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).