1. Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and motility. About 20 RTK classes have been identified. The Eph receptor family is the largest group of RTKs [

1]. The Eph/Ephrin system plays a vital role in normal development [

2,

3] and diseases such as cancer [

4,

5,

6]. EphB receptors bind to membrane-bound ephrin B ligands, which mediate bi-directional signaling and regulate homeostasis. [

7]. In the normal intestine, EphB expression shows a gradient, with the highest levels located at the crypt base [

8]. In contrast, the ephrin B ligands display an opposite gradient, with their highest expression at the villus tip [

8]. In EphB3-deficient mice, Paneth cells are improperly positioned, being spread along the crypt–villus axis instead of being confined to the crypts [

8].

In the crypt base of the normal intestine, Wnt signaling plays essential roles in maintaining stem cells [

9]. Wnt activation causes β-catenin to move to the nucleus and activates β-catenin/TCF target genes like

MYC and

EPHB3 [

10]. Additionally, the ubiquitin ligase Mule promotes the ubiquitination of EphB3 and its degradation via proteasomal and/or lysosomal pathways to limit proliferation and maintain a proper EphB3 gradient [

11].

The constitutive activation of Wnt signaling causes intestinal adenoma development in APC

min mice [

12]. Loss of Mule exacerbates the APC

min phenotype, suggesting that Mule serves as a tumor suppressor in the intestine through maintenance of proper EphB3 gradient [

11]. During colorectal cancer (CRC) progression, EphB3 shows initial overexpression in early adenoma [

13]. EphB3 forward signaling can suppress CRC migration and invasion by inhibiting AKT [

14]. EphB3 exhibits progressive downregulation in advanced tumors, especially at invasive fronts [

15]. The downregulation of EphB3 precedes the loss of E-cadherin, indicating its role in initiating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [

16,

17]. Clinically, high EphB3 expression is associated with well-differentiated early-stage tumors, whereas its absence in metastatic CRC links to poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, and advanced TNM stages [

15]. Therefore, the development of anti-EphB3 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is crucial for investigating stem cell functions and diagnosing tumors.

We have utilized the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method to develop mAbs targeting various membrane proteins. The CBIS method involves using cells that overexpress the target antigen as immunogens and screening hybridoma supernatants with flow cytometry. To date, we have successfully generated mAbs against transmembrane proteins, including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family [

18,

19], Eph family [

20,

21,

22], and epithelial cell adhesion molecule family [

23,

24] using the CBIS method. In this study, we generated anti-EphB3 mAbs using the CBIS method and assessed their potential for various applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies

An anti-human EphB3 mAb (clone 647354, mouse IgG1, kappa) was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). An anti-β-actin mAb (clone AC-15) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Cell Lines

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1, LN229 glioblastoma, P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1) myeloma, and human colorectal (LS174T) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The EphB3 complementary DNA (Catalog No.: HGX039581, RIKEN BRC, Ibaraki, JAPAN) was subcloned into a pCAG-Ble vector (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Plasmid transfection into CHO-K1 and LN229 cells was performed using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Stable transfectants (CHO/EphB3 and LN229/EphB3) were then selected with a cell sorter (SH800, Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using an anti-hEphB3 monoclonal antibody (clone 647354). After sorting, cells were cultured in medium containing 0.5 mg/mL Zeocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). EphB3-knockout LS174T (BINDS-61) was generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system with EphB3-specific guide RNA (TTCCAGCGCCCGGCAGCCGG). These cells and other Eph receptor-expressing CHO-K1 cells (e.g., CHO/EphA2) were cultured as previously described [

20]

2.3. Production of Hybridomas

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) and conducted in accordance with the NIH (National Research Council) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. To develop anti-EphB3 mAbs, two 5-week-old female BALB/cAJcl mice (CLEA Tokyo, Japan) were immunized intraperitoneally with LN229/EphB3 (1 × 108 cells/mouse) starting at 6 weeks of age. Alhydrogel adjuvant 2% (InvivoGen) was added to the immunogen cells during the first immunization. Subsequently, three weekly intraperitoneal injections of LN229/EphB3 (1 × 108 cells/mouse) were administered without adjuvant. A final booster injection of 1 × 108 LN229/EphB3 cells was given two days before harvesting spleen cells from the mice. Cell fusion was performed between harvested splenocytes and P3U1 myeloma cells. The resulting hybridoma supernatants were screened by flow cytometry using CHO/EphB3 and parental CHO-K1 cells. Anti-EphB3 mAbs were purified from the hybridoma supernatants using Ab-Capcher (ProteNova, Kagawa, Japan).

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cells were harvested using 2.5 g/L-Trypsin/1 mmol/L-EDTA solution with phenol red (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) and incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes at 4 °C. Subsequently, they were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse (diluted 1:2000) or FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG (diluted 1:2000) before being analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp.).

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant (KD) by Flow Cytometry

CHO/EphB3 and LS174T were suspended in 100 μL of serially diluted Eb3Mab-5, Eb3Mab-11, or 647354, then treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (dilution 1:200). Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer, and the dissociation constant (KD) was analyzed by fitting the binding isotherms into the built-in one-site binding model in GraphPad PRISM 10 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), then proteins were separated on 5%-20% polyacrylamide gels (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Merck KGaA). After blocking with 4% skim milk (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, membranes were incubated with 5 μg/mL of Eb3Mab-11, 1 μg/mL of 647354, or 1 μg/mL of anti-β-actin mAb (clone AC-15). Then, they were incubated again with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulins (diluted 1:1000; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, protein bands were detected using ImmunoStar LD (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) with a Sayaca-Imager (DRC Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) CHO/EphB3 and CHO-K1 blocks were prepared using iPGell (Genostaff Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The FFPE cell sections were stained with Eb3Mab-11 (5 μg/mL) and 647354 (5 μg/mL) using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit or ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit, respectively (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of Anti-EphB3 mAbs, Eb3Mab-5 and Eb3Mab-11, Using the CBIS Method

To develop mAbs of anti-EphB3, we employed the CBIS method using EphB3-overexpressed LN229 cells as an antigen. LN229/EphB3 were injected intraperitoneally into female BALB/cAJcl mice (

Figure 1A). The splenocytes were harvested from mice and fused with P3U1 cells (

Figure 1B). After the formation of hybridomas, the supernatants were screened by flow cytometry to identify the CHO/EphB3-reactive supernatants (

Figure 1C). Afterward, we performed limiting dilution of the hybridomas and established clones of anti-EphB3 mAbs (

Figure 1D). We finally established 17 clones and selected Eb

3Mab-5 (IgG

1, κ) and Eb

3Mab-11 (IgG

1, κ) for their applications including flow cytometry, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry.

After purification of Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11, we conducted flow cytometry to determine the specificity using Eph receptor-overexpressed CHO-K1. As shown in

Figure 2, Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11 recognized CHO/EphB3, but not other 13 Eph receptors (EphA1 to A8, A10, B1, B2, B4, and B6) (

Figure 2). These results indicated that Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11 can specifically detect EphB3 in flow cytometry.

3.2. Validation of Anti-EphB3 mAb Reactivity Using Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was performed using Eb

3Mab-5, Eb

3Mab-11, and a commercially available anti-EphB3 mAb (clone 647354) on CHO-K1, CHO/EphB3, LS174T, and EphB3-knockout LS174T (BINDS-61) cells. Results showed that Eb

3Mab-5, Eb

3Mab-11, and 647354 recognized CHO/EphB3 in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3A), but not parental CHO-K1 cells (

Figure 3B). Both Eb

3Mab-5, Eb

3Mab-11, and 647354 also recognized LS174T cells in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 4A), but not BINDS-61 cells (

Figure 4B). Eb

3Mab-11 exhibited lower reactivity compared to Eb

3Mab-5 and 647354. These results indicate that Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11 can detect endogenous and exogenous EphB3 in flow cytometry.

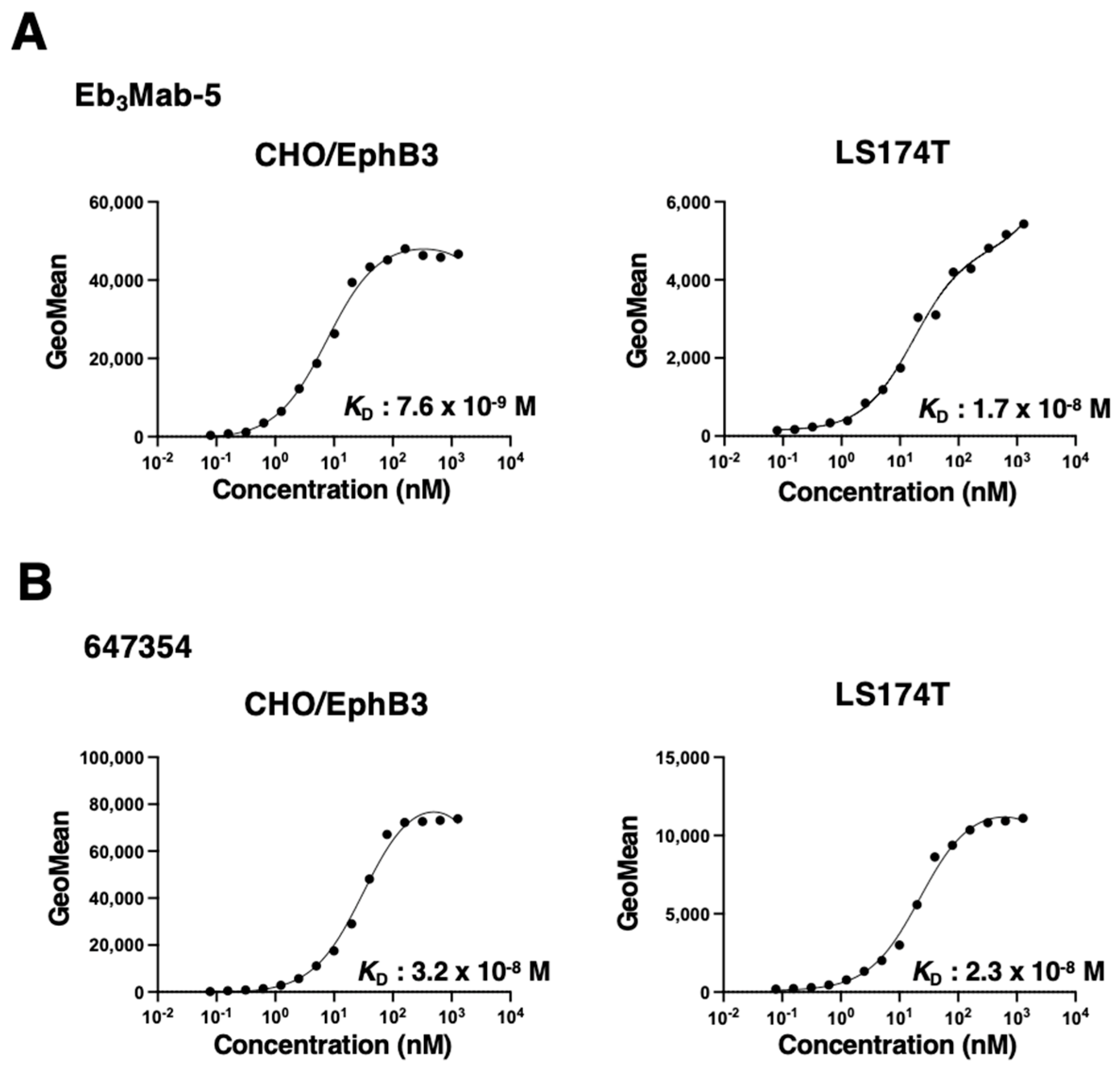

3.3. Assessment of Binding Affinity Using Anti-EphB3 mAb

The binding affinity of anti-EphB3 mAbs was assessed with CHO/EphB3 and LS174T cells using flow cytometry. The results showed that the

KD values of Eb

3Mab-5 for CHO/EphB3 and LS174T were 7.6 ×10

-9 M, 1.7 ×10

-8 M, respectively (

Figure 5A). In contrast, the

KD values of 647354 for CHO/EphB3 and LS174T were 3.2 × 10

-8 M and 2.3 × 10

-8 M, respectively (

Figure 5B). These results indicate that Eb

3Mab-5 possesses a higher binding affinity for EphB3-positive cells compared to 647354. In contrast, the binding curves of Eb

3Mab-11 did not reach a plateau, suggesting lower affinities for those cells (

Supplementary Figure S1).

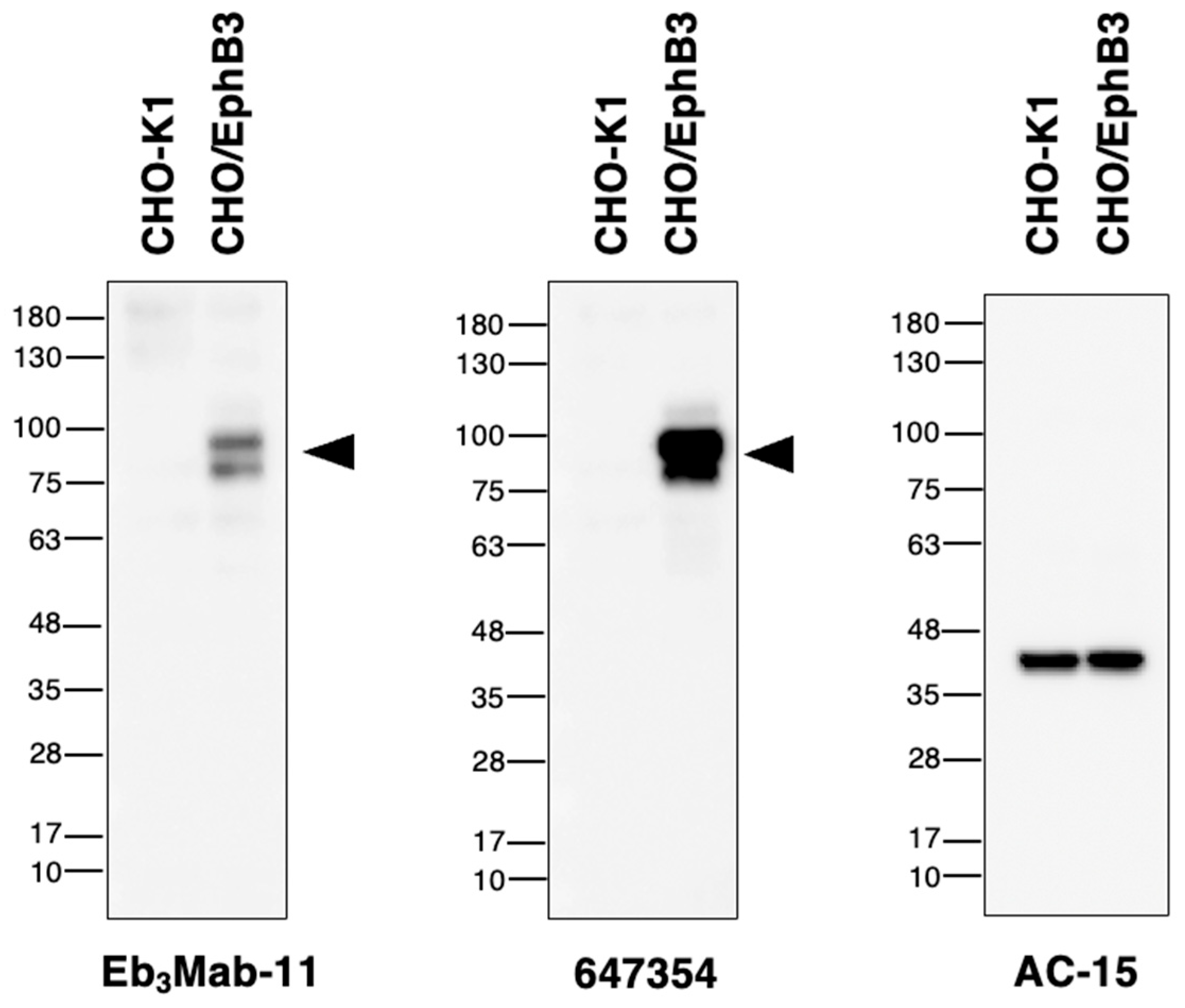

3.4. Western Blot Analysis Using Anti-EphB3 mAbs

Western blot analysis was performed to assess the availability of Eb

3Mab-11, as preliminary analysis using supernatant from Eb

3Mabs revealed that only Eb

3Mab-11 was suitable for western blot analysis. Eb

3Mab-11 and 647354 detected the ~100 kDa band of EphB3 in lysates from CHO/EphB3 (

Figure 6), whereas this band was not present in lysates from CHO-K1. The results indicate that E

b3Mab-11 can detect EphB3 in western blot analysis.

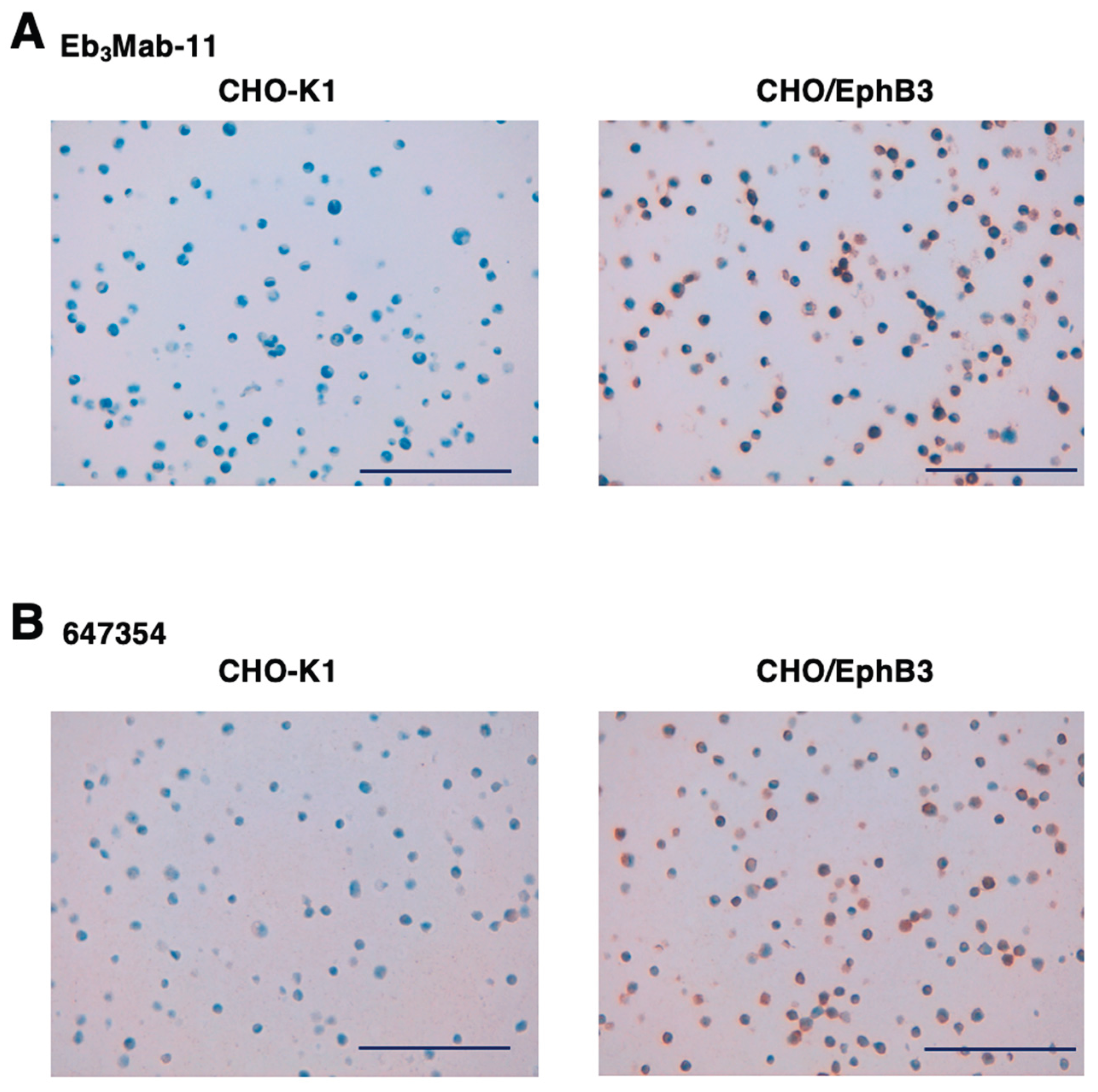

3.5. IHC Using Anti-EphB3 mAbs

Eb

3Mab-11 was assessed for IHC by staining FFPE CHO-K1 and CHO/EphB3 sections. Both Eb

3Mab-11 (

Figure 7A) and 647354 (

Figure 7B) demonstrated membranous staining in CHO/EphB3 but not in CHO-K1, confirming their availability for IHC to identify EphB3-positive cells in FFPE cell blocks.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed anti-human EphB3 mAbs, Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11, using the CIBS method (

Figure 1). We demonstrated that both anti-EphB3 mAbs specifically recognize EphB3 in CHO/EphB3 and LS174T cells but not in CHO-K1 or BINDS-61 cells in flow cytometry (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Additionally, they do not recognize other Eph-receptor-overexpressing CHO-K1 cells (

Figure 2). Eb

3Mab-5 has a higher binding affinity for CHO/EphB3 and LS174T (

Figure 5) compared to Eb

3Mab-11. Conversely, Eb

3Mab-11 is a versatile mAb for detecting EphB3 in flow cytometry, western blot, and IHC. (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Among 17 clones of Eb

3Mabs, Eb

3Mab-11 is the only mAb suitable for multiple applications, and Eb

3Mab-5 showed the highest reactivity to CHO/EphB3 in flow cytometry. The information has been updated on our website “Antibody bank (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm).”

We investigated EphB3 expression in several colorectal cancer cell lines using 647354 and found that LS174T exhibited the highest level of EphB3 (

Figure 5). Since we previously confirmed that LS174T can make a tumor xenograft in nude mice [

25], the antitumor efficacy of Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11 could be evaluated in the model. To evaluate the antitumor efficacy of the Eb

3Mabs, cloning of cDNA and production of class-switched recombinant mAbs are required. We have previously generated mouse IgG

2a-type, human IgG

1-type, and humanized recombinant mAbs to confer the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity [

25]. Using these mAbs, antitumor activities were evaluated using mouse xenograft models [

24,

25]. We have initiated cloning of the cDNA of Eb

3Mab-5 and Eb

3Mab-11 and will evaluate their antitumor efficacy using class-switched (mouse IgG

2a or human IgG

1) mAbs.

A major challenge in CRC treatment is disease relapse caused by drug resistance [

26]. In most CRC cases, patients eventually become resistant to anticancer agents [

26]. Cetuximab has antitumor effects by preventing EGF from attaching to the extracellular part of EGFR, which stops ligand-driven EGFR signaling [

27]. Cetuximab is linked to fewer side effects and has been demonstrated to extend survival in patients with metastatic CRC [

28]. Although cetuximab resistance is also observed clinically, the molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Microarray analysis of cetuximab-resistant cells identified EphB3 as involved in resistance through complex formation with EGFR [

29]. The EphB3-EGFR complex mediates STAT3 activation induced by EGF and cetuximab treatment in cetuximab-resistant CRC cells [

29]. Combination therapy of cetuximab with an EphB3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (LDN-211904 [

30]) showed a potent antitumor efficacy through inhibition of STAT3-activation in the cetuximab-resistant CRC xenograft [

29]. Anti-EphB3 mAbs, which inhibit the EphB3-EGFR complex formation, may overcome cetuximab resistance. Therefore, analyses of the binding epitope and biological activity of Eb

3Mabs are necessary. Additionally, a class-switched mAb derived from Eb

3Mabs might enhance therapy for cetuximab-resistant CRC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Guanjie Li: Investigation; Hiroyuki Suzuki: Investigation, Writing – original draft; Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization; Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP25am0521010 (to Y.K.), JP25ama121008 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221339 (to Y.K.), and JP25bm1123027 (to Y.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant no. 25K10553 (to Y.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2024, 24, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Su, S.A.; Shen, J.; Ma, H.; Le, J.; Xie, Y.; Xiang, M. Recent advances of the Ephrin and Eph family in cardiovascular development and pathologies. iScience 2024, 27, 110556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasewicz, J.; Yu, W.M. Eph and ephrin signaling in the development of the central auditory system. Dev Dyn 2023, 252, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarini, J.F.; Gonçalves, M.W.A.; de Lima-Souza, R.A.; Lavareze, L.; de Carvalho Kimura, T.; Yang, C.C.; Altemani, A.; Mariano, F.V.; Soares, H.P.; Fillmore, G.C.; et al. Potential role of the Eph/ephrin system in colorectal cancer: emerging druggable molecular targets. Front Oncol 2024, 14, 1275330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Scott, A.M.; Janes, P.W. Eph Receptors in Cancer. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakos, S.P.; Petrogiannopoulos, L.; Pergaris, A.; Theocharis, S. The EPH/Ephrin System in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling complexes in the plasma membrane. Trends Biochem Sci 2024, 49, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E.; Henderson, J.T.; Beghtel, H.; van den Born, M.M.; Sancho, E.; Huls, G.; Meeldijk, J.; Robertson, J.; van de Wetering, M.; Pawson, T.; et al. Beta-catenin and TCF mediate cell positioning in the intestinal epithelium by controlling the expression of EphB/ephrinB. Cell 2002, 111, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, J.; Clevers, H. Cell fate specification and differentiation in the adult mammalian intestine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevers, H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 2006, 127, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Brauer, C.; Hao, Z.; Elia, A.J.; Fortin, J.M.; Nechanitzky, R.; Brauer, P.M.; Sheng, Y.; Mana, M.D.; Chio, I.I.C.; Haight, J.; et al. Mule Regulates the Intestinal Stem Cell Niche via the Wnt Pathway and Targets EphB3 for Proteasomal and Lysosomal Degradation. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.K.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B.; Preisinger, A.C.; Moser, A.R.; Luongo, C.; Gould, K.A.; Dove, W.F. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science 1992, 256, 668–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H.; Batlle, E. EphB/EphrinB receptors and Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekera, P.; Perfetto, M.; Lu, C.; Zhuo, M.; Bahudhanapati, H.; Li, J.; Chen, W.C.; Kulkarni, P.; Christian, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Metalloprotease ADAM9 cleaves ephrin-B ligands and differentially regulates Wnt and mTOR signaling downstream of Akt kinase in colorectal cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.G.; Kim, H.S.; Bae, J.M.; Kim, W.H.; Hyun, C.L.; Kang, G.H. Expression Profile and Prognostic Significance of EPHB3 in Colorectal Cancer. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamet, L.; Hawkins, K.; Ward, C.M. Loss of function of e-cadherin in embryonic stem cells and the relevance to models of tumorigenesis. J Oncol 2011, 2011, 352616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theys, J.; Jutten, B.; Habets, R.; Paesmans, K.; Groot, A.J.; Lambin, P.; Wouters, B.G.; Lammering, G.; Vooijs, M. E-Cadherin loss associated with EMT promotes radioresistance in human tumor cells. Radiother Oncol 2011, 99, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Yamada, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Chang, Y.W.; Harada, H.; Kato, Y. Establishment of EMab-134, a Sensitive and Specific Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody for Detecting Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells of the Oral Cavity. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Yamada, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Saidoh, N.; Chang, Y.W.; Handa, S.; Takahashi, M.; et al. H(2)Mab-77 is a Sensitive and Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody Against Breast Cancer. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Hirose, M.; Satofuka, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a highly sensitive and specific anti-EphB2 monoclonal antibody (Eb2Mab-12) for flow cytometry. Microbes & Immunity 2025, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-human EphA2 monoclonal antibody Ea2Mab-7 for multiple applications. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Hirose, M.; Shinoda, K.; Nakamura, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a specific anti-human EphA3 monoclonal antibody, Ea3Mab-20, for flow cytometry. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 43, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Suzuki, H.; Asano, T.; Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-EpCAM Monoclonal Antibody for Various Applications. Antibodies (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Ohishi, T.; Asano, T.; Takei, J.; Nanamiya, R.; Hosono, H.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Kawada, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. An anti-TROP2 monoclonal antibody TrMab-6 exerts antitumor activity in breast cancer mouse xenograft models. Oncol Rep 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. EphB2-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies Exerted Antitumor Activities in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Lung Mesothelioma Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavand, M.; Majidinia, M.; Yousefi, B. Critical Contribution of Various Signaling Pathways in the Development of Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer: An Update. IUBMB Life 2025, 77, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, A.H.; Çatli, M.M. Colorectal cancer treatment commentary review. Eur J Cancer 2025, 230, 115809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Yoshida, Y.; Takashima, A.; Kato, Y.; Kawada, M. Current Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Jo, M.J.; Kim, B.R.; Jeong, Y.A.; Na, Y.J.; Kim, J.L.; Jeong, S.; Yun, H.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, B.G.; et al. Sonic hedgehog pathway activation is associated with cetuximab resistance and EPHB3 receptor induction in colorectal cancer. Theranostics 2019, 9, 2235–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Choi, S.; Case, A.; Gainer, T.G.; Seyb, K.; Glicksman, M.A.; Lo, D.C.; Stein, R.L.; Cuny, G.D. Structure-activity relationship study of EphB3 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2009, 19, 6122–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).