Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

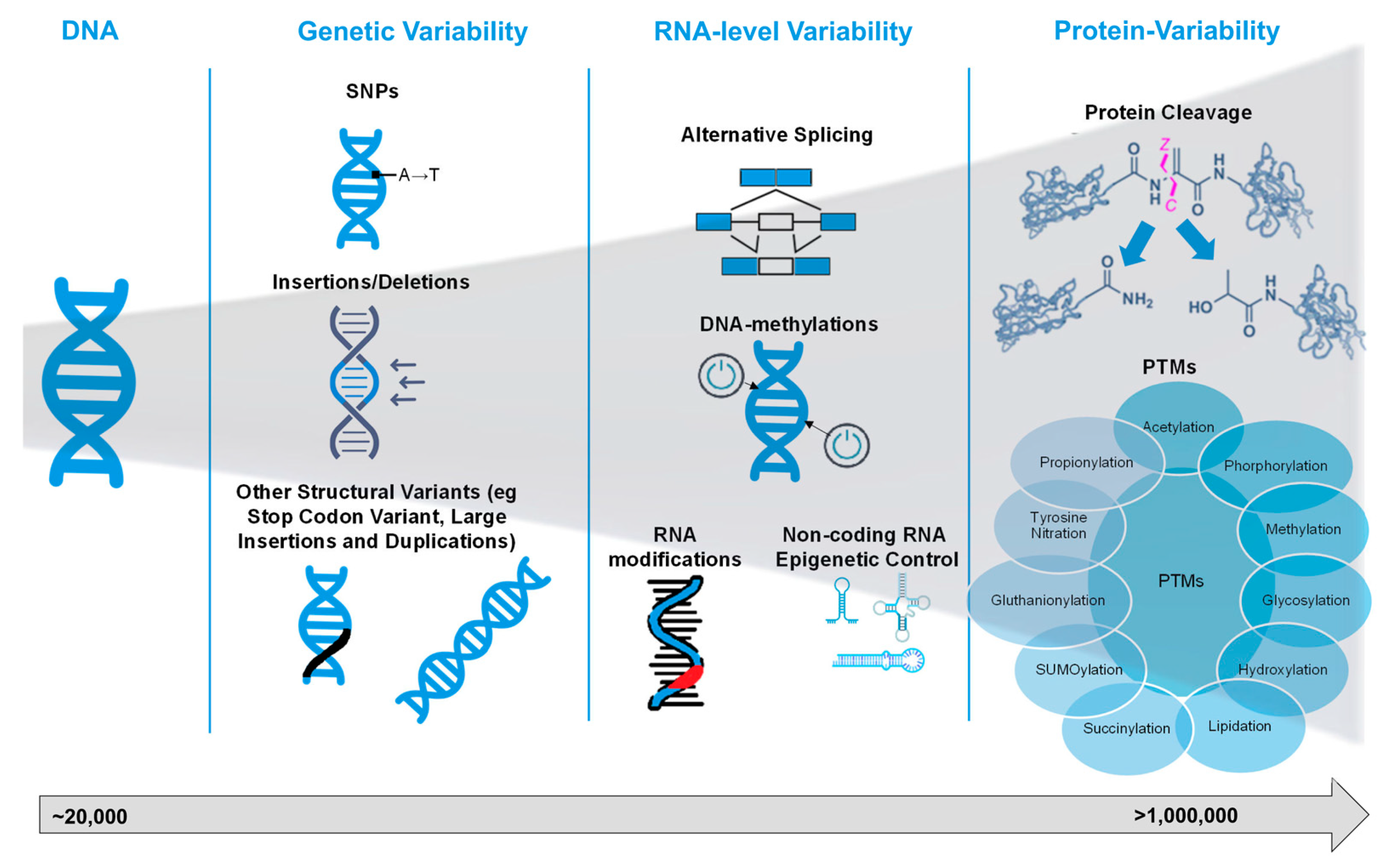

2. Biological Basis of Proteoforms

3. MS-Based Proteomics for PTM Analysis

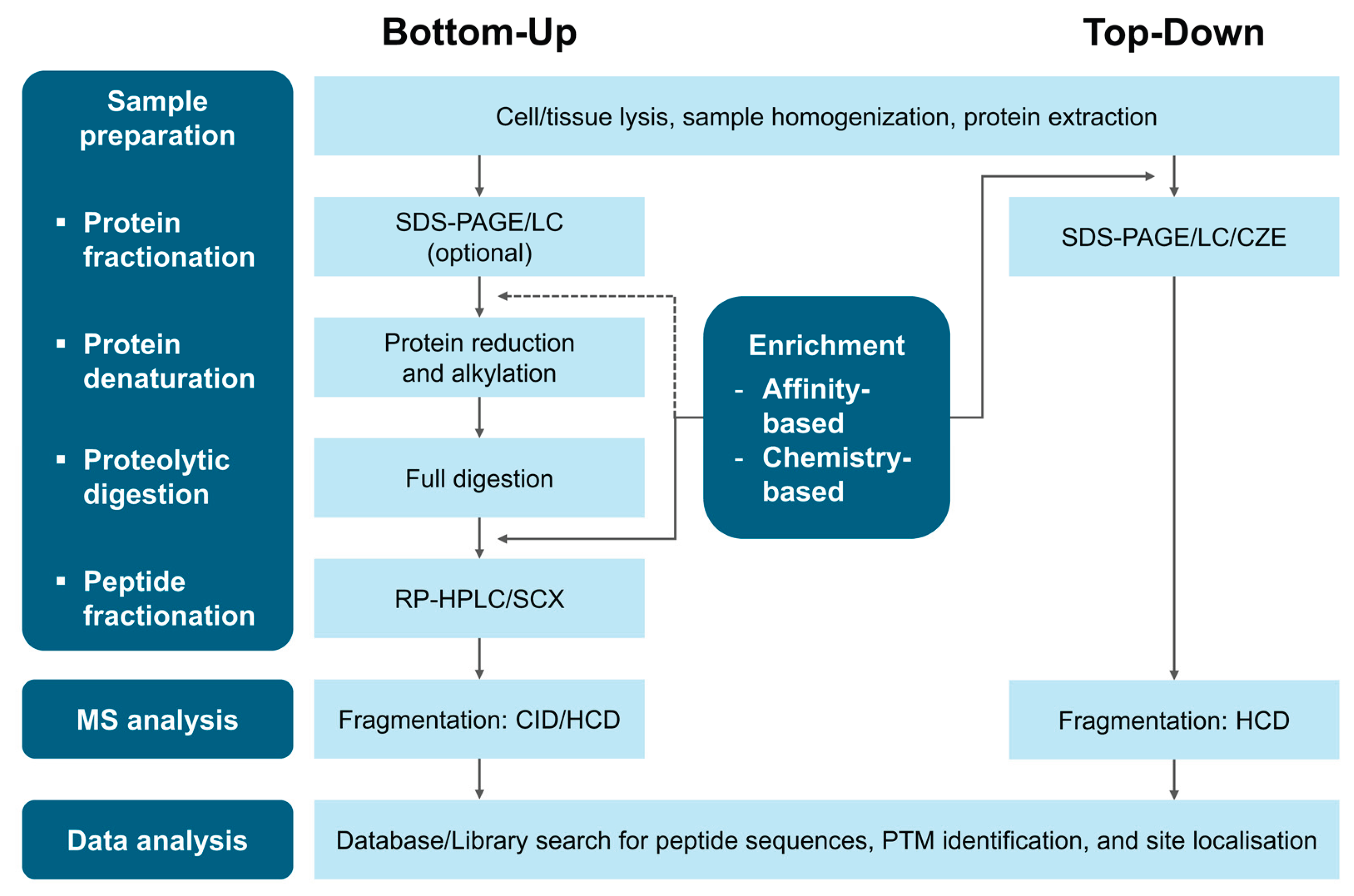

3.1. Bottom-Up Proteomics Workflow

3.2. Top-Down Proteomics Workflow

3.3. PTM Enrichment Methods

3.4. Fragmentation Methods

4. Bioinformatics in PTM Analysis

4.1. Databases for PTM

4.2. Tools for PTM Identification and Localisation

4.2.1. Bottom-Up Proteomics

4.2.2. Top-Down Proteomics

5. PTMs in Cardiovascular Diseases

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CID | Collision-induced dissociation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| ETD | Electron transfer dissociation |

| FLR | False localisation rate |

| GRP | Gla-rich protein |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MGP | Matrix Gla protein |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| m/z | Mass-to-charge ratio |

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| TMT | Tandem mass tag |

References

- Barallobre-Barreiro, J.; Radovits, T.; Fava, M.; Mayr, U.; Lin, W.Y.; Ermolaeva, E.; Martínez-López, D.; Lindberg, E.L.; Duregotti, E.; Daróczi, L.; et al. Extracellular matrix in heart failure: role of ADAMTS5 in proteoglycan remodeling. Circulation 2021, 144, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilatos, K.; Stojkovic, S.; Hasman, M.; van der Laan, S.W.; Baig, F.; Barallobre-Barreiro, J.; Schmidt, L.E.; Yin, S.; Yin, X.; Burnap, S.; et al. Proteomic atlas of atherosclerosis: the contribution of proteoglycans to sex differences, plaque phenotypes, and outcomes. Circ Res 2023, 133, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.B.; Chiou, J.; Traylor, M.; Benner, C.; Hsu, Y.H.; Richardson, T.G.; Surendran, P.; Mahajan, A.; Robins, C.; Vasquez-Grinnell, S.G.; et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 2023, 622, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.G.; Gerszten, R.E. Emerging affinity-based proteomic technologies for large-scale plasma profiling in cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2017, 135, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ille, A.M.; Lamont, H.; Mathews, M.B. The Central Dogma revisited: Insights from protein synthesis, CRISPR, and beyond. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2022, 13, e1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherrahrou, R.; Baig, F.; Theofilatos, K.; Lue, D.; Beele, A.; Örd, T.; Kaikkonen, M.U.; Aherrahrou, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Ghosh, S.K.B.; et al. Secreted Protein Profiling of Human Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells Identifies Vascular Disease Associations. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2024, 44, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramazi, S.; Zahiri, J. Post-translational modifications in proteins: resources, tools and prediction methods. Database 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, E.; Maack, C. Metabolic remodelling in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018, 15, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, C.; Boll, I.; Finsen, B.; Modzel, M.; Larsen, M.R. Characterizing disease-associated changes in post-translational modifications by mass spectrometry. Expert Rev Proteomics 2018, 15, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascovici, D.; Wu, J.X.; McKay, M.J.; Joseph, C.; Noor, Z.; Kamath, K.; Wu, Y.; Ranganathan, S.; Gupta, V.; Mirzaei, M. Clinically relevant post-translational modification analyses-maturing workflows and bioinformatics tools. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, K.; Dowling, P.; Bazou, D.; O’Gorman, P. Current methods of post-translational modification analysis and their applications in blood cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnatsakanyan, R.; Shema, G.; Basik, M.; Batist, G.; Borchers, C.H.; Sickmann, A.; Zahedi, R.P. Detecting post-translational modification signatures as potential biomarkers in clinical mass spectrometry. Expert Rev Proteomics 2018, 15, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutert, M.; Entwisle, S.W.; Villén, J. Decoding post-translational modification crosstalk with proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2021, 20, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgrave, L.M.; Wang, M.; Yang, D.; DeMarco, M.L. Proteoforms and their expanding role in laboratory medicine. Pract Lab Med 2022, 28, e00260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Sun, L. Mass spectrometry-intensive top-down proteomics: an update on technology advancements and biomedical applications. Anal Methods 2024, 16, 4664–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.; Hsu, J.; Tri, L.Q.; Willi, M.; Mansour, T.; Kai, Y.; Garner, J.; Lopez, J.; Busby, B. dbVar structural variant cluster set for data analysis and variant comparison. F1000Res 2016, 5, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.I.; van de Geijn, B.; Raj, A.; Knowles, D.A.; Petti, A.A.; Golan, D.; Gilad, Y.; Pritchard, J.K. RNA splicing is a primary link between genetic variation and disease. Science 2016, 352, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Agar, J.N.; Amster, I.J.; Baker, M.S.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Boja, E.S.; Costello, C.E.; Cravatt, B.F.; Fenselau, C.; Garcia, B.A.; et al. How many human proteoforms are there? Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tress, M.L.; Abascal, F.; Valencia, A. Most alternative isoforms are not functionally important. Trends Biochem Sci 2017, 42, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, J.M.; Pozo, F.; di Domenico, T.; Vazquez, J.; Tress, M.L. An analysis of tissue-specific alternative splicing at the protein level. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatheritt, R.J.; Sterne-Weiler, T.; Blencowe, B.J. The ribosome-engaged landscape of alternative splicing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.I.; Lessard, J.; Crabtree, G.R. Understanding the words of chromatin regulation. Cell 2009, 136, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.M.; Condorelli, G. Epigenetic modifications and noncoding RNAs in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015, 12, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartford, C.C.R.; Lal, A. When long noncoding becomes protein coding. Mol Cell Biol 2020, 40, e00528–00519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, M.; Diao, H.; Xiong, L.; Yang, X.; Xing, S. LncRNA-encoded peptides: unveiling their significance in cardiovascular physiology and pathology—current research insights. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, J.; Noberini, R.; Bonaldi, T.; Cecconi, D. Advances in enrichment methods for mass spectrometry-based proteomics analysis of post-translational modifications. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1678, 463352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Rex, D.A.B.; Schuster, D.; Neely, B.A.; Rosano, G.L.; Volkmar, N.; Momenzadeh, A.; Peters-Clarke, T.M.; Egbert, S.B.; Kreimer, S.; et al. Comprehensive overview of bottom-up proteomics using mass spectrometry. ACS Meas Sci Au 2024, 4, 338–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fert-Bober, J.; Murray, C.I.; Parker, S.J.; Van Eyk, J.E. Precision profiling of the cardiovascular post-translationally modified proteome: where there is a will, there is a way. Circ Res 2018, 122, 1221–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tape, C.J.; Worboys, J.D.; Sinclair, J.; Gourlay, R.; Vogt, J.; McMahon, K.M.; Trost, M.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Lamont, D.J.; Jørgensen, C. Reproducible automated phosphopeptide enrichment using magnetic TiO2 and Ti-IMAC. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10296–10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.E.; Rogowska-Wrzesinska, A. The challenge of detecting modifications on proteins. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.A.; Melby, J.A.; Roberts, D.S.; Ge, Y. Top-down proteomics: challenges, innovations, and applications in basic and clinical research. Expert Rev Proteomics 2020, 17, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, A.; Eyers, C.E. Top-down proteomics and the challenges of true proteoform characterization. J Proteome Res 2023, 22, 3663–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, T.Y.; Mohtar, M.A.; Lee, P.Y.; Omar, N.; Zhou, H.; Ye, M. Widening the bottleneck of phosphoproteomics: evolving strategies for phosphopeptide enrichment. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2021, 40, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Kaneko, T.; Sidhu, S.S.; Li, S.S. Creation of phosphotyrosine superbinders by directed evolution of an SH2 domain. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1555, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, C. Profiling of post-translational modifications by chemical and computational proteomics. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13506–13519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.M.; McLuckey, S.A. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) of peptides and proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2005, 402, 148–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, C.K.; Altelaar, A.F.; Hennrich, M.L.; Nolting, D.; Zeller, M.; Griep-Raming, J.; Heck, A.J.; Mohammed, S. Improved peptide identification by targeted fragmentation using CID, HCD and ETD on an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 2377–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, H.; Sun, R.X.; Yang, B.; Song, C.Q.; Wang, L.H.; Liu, C.; Fu, Y.; Yuan, Z.F.; Wang, H.P.; He, S.M.; et al. pNovo: de novo peptide sequencing and identification using HCD spectra. J Proteome Res 2010, 9, 2713–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Sharp, J.S. Relative quantification of sites of peptide and protein modification using size exclusion chromatography coupled with electron transfer dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2016, 27, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M.; Ghiulai, R.M.; Zamfir, A.D. Recent developments and applications of electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry in proteomics. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, P.V.; Zhang, B.; Murray, B.; Kornhauser, J.M.; Latham, V.; Skrzypek, E. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 43, D512–D520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Birch, H.; Rapacki, K.; Brunak, S.; Hansen, J.E. O-GLYCBASE version 4.0: a revised database of O-glycosylated proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.P.; Peterson, R.; Mariethoz, J.; Gasteiger, E.; Akune, Y.; Aoki-Kinoshita, K.F.; Lisacek, F.; Packer, N.H. UniCarbKB: building a knowledge platform for glycoproteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernorudskiy, A.L.; Garcia, A.; Eremin, E.V.; Shorina, A.S.; Kondratieva, E.V.; Gainullin, M.R. UbiProt: a database of ubiquitylated proteins. BMC Bioinform 2007, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnad, F.; Ren, S.; Cox, J.; Olsen, J.V.; Macek, B.; Oroshi, M.; Mann, M. PHOSIDA (phosphorylation site database): management, structural and evolutionary investigation, and prediction of phosphosites. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkel, H.; Chica, C.; Via, A.; Gould, C.M.; Jensen, L.J.; Gibson, T.J.; Diella, F. Phospho.ELM: a database of phosphorylation sites—update 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 39, D261–D267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenmiller, B.; Campbell, D.; Gerrits, B.; Lam, H.; Jovanovic, M.; Picotti, P.; Schlapbach, R.; Aebersold, R. PhosphoPep--a database of protein phosphorylation sites in model organisms. Nat Biotechnol 2008, 26, 1339–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heazlewood, J.L.; Durek, P.; Hummel, J.; Selbig, J.; Weckwerth, W.; Walther, D.; Schulze, W.X. PhosPhAt: a database of phosphorylation sites in Arabidopsis thaliana and a plant-specific phosphorylation site predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, D1015–D1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, T.U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D609–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn-Zabal, M.; Michel, P.-A.; Gateau, A.; Nikitin, F.; Schaeffer, M.; Audot, E.; Gaudet, P.; Duek, P.D.; Teixeira, D.; Rech de Laval, V.; et al. The neXtProt knowledgebase in 2020: data, tools and usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 48, D328–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguez, P.; Letunic, I.; Parca, L.; Garcia-Alonso, L.; Dopazo, J.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Bork, P. PTMcode v2: a resource for functional associations of post-translational modifications within and between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 43, D494–D502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.T.; Huang, K.Y.; Su, M.G.; Lee, T.Y.; Bretaña, N.A.; Chang, W.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Chen, Y.J.; Huang, H.D. DbPTM 3.0: an informative resource for investigating substrate site specificity and functional association of protein post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Arighi, C.N.; Ross, K.E.; Ren, J.; Li, G.; Chen, S.C.; Wang, Q.; Cowart, J.; Vijay-Shanker, K.; Wu, C.H. iPTMnet: an integrated resource for protein post-translational modification network discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D542–d550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolg, D.P.; Wilhelm, M.; Schmidt, T.; Médard, G.; Zerweck, J.; Knaute, T.; Wenschuh, H.; Reimer, U.; Schnatbaum, K.; Kuster, B. ProteomeTools: systematic characterization of 21 post-translational protein modifications by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using synthetic peptides. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 1850–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn-Zabal, M.; Michel, P.-A.; Gateau, A.; Nikitin, F.; Schaeffer, M.; Audot, E.; Gaudet, P.; Duek, P.D.; Teixeira, D.; Rech de Laval, V.; et al. The neXtProt knowledgebase in 2020: data, tools and usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D328–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.N.; Pappin, D.J.; Creasy, D.M.; Cottrell, J.S. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 1999, 20, 3551–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, J.K.; McCormack, A.L.; Yates, J.R. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 1994, 5, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Neuhauser, N.; Michalski, A.; Scheltema, R.A.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.T.; Leprevost, F.V.; Avtonomov, D.M.; Mellacheruvu, D.; Nesvizhskii, A.I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Millikin, R.J.; Rolfs, Z.; Shortreed, M.R.; Smith, L.M. A hybrid spectral library and protein sequence database search strategy for bottom-up and top-down proteomic data analysis. J Proteome Res 2022, 21, 2609–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shteynberg, D.D.; Deutsch, E.W.; Campbell, D.S.; Hoopmann, M.R.; Kusebauch, U.; Lee, D.; Mendoza, L.; Midha, M.K.; Sun, Z.; Whetton, A.D.; et al. PTMProphet: fast and accurate mass modification localization for the trans-proteomic pipeline. J Proteome Res 2019, 18, 4262–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausoleil, S.A.; Villén, J.; Gerber, S.A.; Rush, J.; Gygi, S.P. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat Biotechnol 2006, 24, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bern, M.; Kil, Y.J.; Becker, C. Byonic: advanced peptide and protein identification software. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2012, Chapter 13, 13.20.11–13.20.14. [CrossRef]

- Solntsev, S.K.; Shortreed, M.R.; Frey, B.L.; Smith, L.M. Enhanced global post-translational modification discovery with MetaMorpheus. J Proteome Res 2018, 17, 1844–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitski, M.M.; Lemeer, S.; Boesche, M.; Lang, M.; Mathieson, T.; Bantscheff, M.; Kuster, B. Confident phosphorylation site localization using the Mascot Delta Score. Mol Cell Proteomics 2011, 10, M110.003830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.R.; Trinidad, J.C.; Chalkley, R.J. Modification site localization scoring integrated into a search engine. Mol Cell Proteomics 2011, 10, M111.008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, D.; Burrell, M.A.; Studholme, D.J.; Jones, A.M. PhosCalc: a tool for evaluating the sites of peptide phosphorylation from mass spectrometer data. BMC Res. Notes 2008, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taus, T.; Köcher, T.; Pichler, P.; Paschke, C.; Schmidt, A.; Henrich, C.; Mechtler, K. Universal and confident phosphorylation site localization using phosphoRS. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 5354–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Tian, Z. Accurate phosphorylation site localization using phospho-brackets. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 996, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermin, D.; Avtonomov, D.; Choi, H.; Nesvizhskii, A.I. LuciPHOr2: site localization of generic post-translational modifications from tandem mass spectrometry data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1141–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.M.; Sweet, S.M.; Cunningham, D.L.; Zeller, M.; Heath, J.K.; Cooper, H.J. SLoMo: automated site localization of modifications from ETD/ECD mass spectra. J Proteome Res 2009, 8, 1965–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.O.; Wright, J.C.; Jones, M.; Rayner, J.C.; Choudhary, J.S. Confident and sensitive phosphoproteomics using combinations of collision induced dissociation and electron transfer dissociation. J. Proteomics 2014, 103, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Zhai, L.; Ying, W.; Qian, X.; Gong, F.; Tan, M.; Fu, Y. PTMiner: localization and quality control of protein modifications detected in an open search and its application to comprehensive post-translational modification characterization in human proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics 2019, 18, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Q.; Xun, L.; Liu, X. TopPIC: a software tool for top-down mass spectrometry-based proteoform identification and characterization. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3495–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.-X.; Luo, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, R.-M.; Zeng, W.-F.; Chi, H.; Liu, C.; He, S.-M. pTop 1.0: a high-accuracy and high-efficiency search engine for intact protein identification. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 3082–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Piehowski, P.D.; Wilkins, C.; Zhou, M.; Mendoza, J.; Fujimoto, G.M.; Gibbons, B.C.; Shaw, J.B.; Shen, Y.; Shukla, A.K.; et al. Informed-Proteomics: open-source software package for top-down proteomics. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, E.W.; Mendoza, L.; Shteynberg, D.D.; Hoopmann, M.R.; Sun, Z.; Eng, J.K.; Moritz, R.L. Trans-proteomic pipeline: robust mass spectrometry-based proteomics data analysis suite. J Proteome Res 2023, 22, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Shortreed, M.R.; Wenger, C.D.; Frey, B.L.; Schaffer, L.V.; Scalf, M.; Smith, L.M. Global post-translational modification discovery. J Proteome Res 2017, 16, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDuc, R.D.; Taylor, G.K.; Kim, Y.B.; Januszyk, T.E.; Bynum, L.H.; Sola, J.V.; Garavelli, J.S.; Kelleher, N.L. ProSight PTM: an integrated environment for protein identification and characterization by top-down mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddy, K.A.; White, M.Y.; Cordwell, S.J. Functional decorations: post-translational modifications and heart disease delineated by targeted proteomics. Genome Med. 2013, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastna, M. Post-translational modifications of proteins in cardiovascular diseases examined by proteomic approaches. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noels, H.; Jankowski, V.; Schunk, S.J.; Vanholder, R.; Kalim, S.; Jankowski, J. Post-translational modifications in kidney diseases and associated cardiovascular risk. Nat Rev Nephrol 2024, 20, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-P.; Zhang, T.-N.; Wen, R.; Liu, C.-F.; Yang, N. Role of posttranslational modifications of proteins in cardiovascular disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3137329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K. Research progress on post-translational modification of proteins and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zeng, C.; Huang, A.; Huang, F.; Meng, A.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, S. Relationship between protein arginine methyltransferase and cardiovascular disease (Review). Biomed Rep 2022, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J. Acetylation in cardiovascular diseases: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatham, J.C.; Patel, R.P. Protein glycosylation in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2024, 21, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wu, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, C.; Xue, L.; Lei, Z.; Li, H.; Shan, Z. New types of post-translational modification of proteins in cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2025, 18, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagwan, N.; El Ali, H.H.; Lundby, A. Proteome-wide profiling and mapping of post translational modifications in human hearts. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Li, L.; Shi, X.-L.; Liu, Y.-P.; Wen, R.; Yang, Y.-H.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.-R.; Xu, Y.-F.; Liu, C.-F.; et al. Succinylation of SERCA2a at K352 promotes its ubiquitinoylation and degradation by proteasomes in sepsis-induced heart dysfunction. Circulation Heart Fail 2025, 18, e012180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; LaPenna, K.B.; Gehred, N.D.; Yu, X.; Tang, W.H.W.; Doiron, J.E.; Xia, H.; Chen, J.; Driver, I.H.; Sachse, F.B.; et al. Dysregulated protein S-nitrosylation promotes nitrosative stress and disease progression in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Res 2025, 137, 1185–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.-F.; Wang, D.-P.; Shen, J.; Gao, L.-J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Q.-H.; Cao, J.-M. Global profiling of protein lysine malonylation in mouse cardiac hypertrophy. J. Proteomics 2022, 266, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, X.; Yu, N.; Yan, R.; Sun, Y.; Tang, C.; Ding, W.; Ling, M.; Song, Y.; Gao, H.; et al. Proteomics and β-hydroxybutyrylation modification characterization in the hearts of naturally senescent mice. Mol Cell Proteomics 2023, 22, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Huang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Guo, M.; Yu, T.; Li, Y. Proteomic analysis and 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation profiling in metabolic syndrome induced restenosis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2025, 24, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, D.; Yao, F.; Feng, S.; Tong, C.; Rao, R.; Zhong, M.; Wang, X.; Feng, W.; Hu, Z.; et al. Serpina3k lactylation protects from cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasman, M.; Mayr, M.; Theofilatos, K. Uncovering protein networks in cardiovascular proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Svanberg, E.; Dadar, M.; Card, D.J.; Chirumbolo, S.; Harrington, D.J.; Aaseth, J. The role of matrix Gla protein (MGP) in vascular calcification. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 1647–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, S.; Dounousi, E.; Eleftheriadis, T.; Liakopoulos, V. Association of the inactive circulating matrix Gla protein with vitamin K intake, calcification, mortality, and cardiovascular disease: a review. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, B. Involvement of vitamin K-dependent proteins in vascular calcification. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 24, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tan, M.; Xie, Z.; Dai, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Identification of lysine succinylation as a new post-translational modification. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, P.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Hu, J. Tandem mass tag-based quantitative proteomic analysis identification of succinylation related proteins in pathogenesis of thoracic aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Hausladen, A.; Zeng, M.; Que, L.; Heitman, J.; Stamler, J.S. A metabolic enzyme for S-nitrosothiol conserved from bacteria to humans. Nature 2001, 410, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yin, X.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zheng, H.; Huang, F.Q.; Liu, B.; Zhou, W.; Qi, L.W.; et al. Proteomic analysis reveals ginsenoside Rb1 attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting ROS production from mitochondrial complex I. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1703–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chen, D.; Zhou, H.-L. S-nitrosylation: mechanistic links between nitric oxide signaling and atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2025, 27, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Qiu, H. Post-translational S-nitrosylation of proteins in regulating cardiac oxidative stress. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, B.; Fazelinia, H.; Mohanty, I.; Raimo, S.; Tenopoulou, M.; Doulias, P.-T.; Ischiropoulos, H. Endogenous S-nitrosocysteine proteomic inventories identify a core of proteins in heart metabolic pathways. Redox Biol 2021, 47, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; Ding, Q.; Zhu, Y.Z. New role of obscure acylation modifications in cardiovascular diseases: what's beyond? Life Sci. 2025, 380, 123944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Du, Y.; Xue, Y.; Miao, G.; Wei, T.; Zhang, P. Identification of malonylation, succinylation, and glutarylation in serum proteins of acute myocardial infarction patients. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2020, 14, 1900103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, D.; Chung, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Dai, L.; Qi, S.; Li, J.; Colak, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-x.; Mu, G.; Yu, Z.-h.; Shi, Z.-a.; Li, X.-x.; Fan, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J. Lactylation: a promising therapeutic target in ischemia-reperfusion injury management. Cell Death Discov 2025, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Yu, H.; Huang, X.; Rao, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Multi-proteomic analysis reveals the effect of protein lactylation on matrix and cholesterol metabolism in tendinopathy. J Proteome Res 2023, 22, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekeen, R.; Haider, A.N.; Akhter, F.; Billah, M.M.; Islam, M.E.; Didarul Islam, K.M. Lipid oxidation in pathophysiology of atherosclerosis: Current understanding and therapeutic strategies. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev 2022, 14, 200143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatana, C.; Saini, N.K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Saini, V.; Sharma, A.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. Mechanistic insights into the oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced atherosclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5245308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flender, D.; Vilenne, F.; Adams, C.; Boonen, K.; Valkenborg, D.; Baggerman, G. Exploring the dynamic landscape of immunopeptidomics: Unravelling posttranslational modifications and navigating bioinformatics terrain. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2025, 44, 599–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugyi, F.; Szabó, D.; Szabó, G.; Révész, Á.; Pape, V.F.S.; Soltész-Katona, E.; Tóth, E.; Kovács, O.; Langó, T.; Vékey, K.; et al. Influence of post-translational modifications on protein identification in database searches. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 7469–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarohi, V.; Basak, T. Perturbed post-translational modification (PTM) network atlas of collagen I during stent-induced neointima formation. J. Proteomics 2023, 276, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Fan, J.; Chen, Y. Comprehensive analysis of lactylation-related gene and immune microenvironment in atrial fibrillation. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025, 12, 1567310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | PTM Focus | Key Features | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTM-specific databases | |||

| PhosphoSitePlus [41] | Phos, Ub, Acet, Methyl | Provides regulatory sites and PTMVars data linked to diseases and cancers. | https://www.phosphosite.org/homeAction.action |

| O-GlycBase [42] | O-gly, C-gly | Prediction tools for O-glycosylation sites based on neural network models. | https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/datasets/OglycBase |

| UniCarbKB [43] | Gly | Integration with structural and experimental glycan databases; GlycoMod tool integration for predicting oligosaccharide structures. | http://unicarbkb.org |

| UbiProt [44] | Ub | Structured protein entry in block format for easy retrieval; detailed ubiquitylation features. | http://ubiprot.org.ru* |

| PHOSIDA [45] | Phos | Phosphosite predictor trained on >5,000 high-confidence sites; motif searching and matching for user-generated or kinase motifs. | http://www.phosida.com* |

| Phospho.ELM [46] | Phos | Available structural disorder/order and accessibility information; conservation score visualisation with multiple sequence alignment. | http://phospho.elm.eu.org |

| PhosphoPep [47] | Phos | Conservation analysis across species; mass spectrometric assays for quantification. | http://www.phosphopep.org |

| PhosPhAt [48] | Phos | Two search strategies: querying experimental data or phosphorylation site prediction. | http://phosphat.mpimpgolm.mpg.de* |

| Curated comprehensive databases | |||

| UniprotKB [49] | Multiple PTMs | Machine learning-assisted curation for paper selection and data extraction; automatic annotation generation. | http://www.uniprot.org |

| neXtProt [55] | Multiple PTMs | Peptide uniqueness checker for identifying unique, pseudo-unique, or non-unique peptides, considering splicing and variants; in silico protein digestion tool for identifying proteases used in MS analysis. | https://www.nextprot.org |

| Integrative databases | |||

| PTMcode2 [51] | Multiple PTMs | Residue co-evolution and proximity-based methods for predicting functional PTM associations; PTM propagation to orthologous proteins for understudied organisms. | https://ptmcode.embl.de |

| dbPTM [52] | Multiple PTMs | Advanced search and visualisation tools for efficient querying and data analysis; functional annotations and disease associations, highlighting cancer-specific PTM regulations. | https://biomics.lab.nycu.edu.tw/dbPTM |

| iPTMnet [53] | Phos, Ub, Acet, Methyl, Gly, SNO, Sumo, Myr | Integrative bioinformatics approach combining text mining, data mining, and ontological representation; captures enzyme-substrate relationships and PTM conservation; tools for search, retrieval, and visual analysis. | http://proteininformationresource.org/iPTMnet |

| Tool | Availability | Compatible Search Engines |

PTM Focus |

Implementation Method | Key Points of Method |

URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTM localisation refinement tools | ||||||

| Mascot Delta Score [65] | Commercial | Mascot | Phos | Difference score | Calculated based on the difference between the highest and second-highest Mascot ion scores for alternative phosphorylation site localisations of the same peptide sequence. | https://www.matrixscience.com |

| SLIP Score [66] | Open source | ProteinProspector | Phos | Difference score | Calculated by comparing the probability or expectation values between the best and next best site assignments for the same peptide, with the difference converted into a Log10-based integer score. | https://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/mshome.htm |

| ASCORE [62] | Open source | SEQUEST, Mascot | Phos | Peak probability score | Calculated by subtracting the cumulative binomial probabilities of the top two site candidates, measuring the likelihood of matching site-determining ions by chance. | http://Ascore.med.harvard.edu* |

| PTM Score [58] | Open source | Andromeda | Any PTMs available by the database used. | Peak probability score | Calculated using a binomial distribution formula to score MS/MS spectra, dividing the spectrum into 100 Th mass ranges and prioritising peaks by intensity. | https://www.maxquant.org |

| PhosCalc [67] | Open source | Any (uses DTA input files) | Phos | Peak probability score | Calculated based on successful matches of theoretical b and y ions, with the probability score. | http://www.ayeaye.tsl.ac.uk/PhosCalc* |

| PhosphoRS [68] | Open source | Search engines within the Proteome Discover suite | Phos | Peak probability score | Calculated using random matches between theoretical and experimental fragment ions using a cumulative binomial distribution. | https://ms.imp.ac.at/?goto=phosphors |

| P-brackets [69] | Open source | SEQUEST, Mascot | Phos | Ion pair-based score | Calculated using phosphorylation brackets, with the P-bracket score determined by the number of complementary product ion pairs that localise a phosphorylation event to a unique site. | http://proteingoggle.tongji.edu.cn* |

| LuciPHOr2 [70] | Open source | Any (uses pepXML input files) | Any PTMs of a fixed mass | Peak probability score | Calculated based on a probability model of peak intensity and mass accuracy, with dynamic training for each dataset and user-defined parameters for PTM analysis. | https://luciphor2.sourceforge.net |

| SLoMo [71,72] | Open source | Any (uses pepXML input files) | Phos, Acet, Ox, Carba, Deam, | Peak probability score | Calculated based on the ASCORE algorithm with enhancements: user-defined modifications, customisable ion sets, and inclusion of hydrogen transfer ions. | http://massspec.bham.ac.uk/slomo* |

| PTMiner [73] | Open source | Any (requires tab-delimited files or outputs from pFind, SEQUEST, or MSFragger) | Phos, Acet, Ox, Meth, Deam | Posterior probability score | Calculated by combining prior probabilities from the MSFS vector with conditional probabilities from an intensity distribution model fitted on matched peaks of unmodified PSMs. | http://fugroup.amss.ac.cn/software/ptminer/ptminer.html |

| PTMProphet [61] | Open source | SEQUEST, Mascot, X!Tandem, Comet, ProteinProspector, MS-GF+, MSFragger | Any PTMs | Peak probability score | Calculated based on observed intensities and peaks, applying a Bayesian framework with renormalised probabilities to reflect the likelihood of modification at each site. | http://www.tppms.org/tools/ptm |

| MetaMorpheus [64] | Open source | Any (requires Thermo .raw, .mzML in centroid mode, or .mgf input file formats) | Any PTMs available by the database used. | Multi-notch search | First multi-notch search: Limiting mass differences to preselected values, improving specificity and reducing search time.Final limited multi-notch search: Accounting for precursor mass deisotoping errors and identifying coisolated peptides, enhancing peptide and PTM identification. | https://smith-chem-wisc.github.io/MetaMorpheus |

| Bottom-up proteomics search engine with PTM support | ||||||

| Byonic [63] | Commercial | No additional search engine needed | Any PTMs, whether present or absent in the database used. | IMP-ptmRS node | Three major features:Modification fine control allows for simultaneous search for multiple PTMs without a combinatorial explosion.Wildcard search enables a search for unanticipated modifications.Glycopeptide search identifies glycosylated peptides without predefined sites or masses. | http://www.proteinmetrics.com |

| Top-down proteomics search engines | ||||||

| ProSight PD | Commercial | No additional search engine needed | Any proteoforms | ProSightPD nodes | Four core ProSightPD nodes:Feature Detector nodes perform spectral deconvolution using sliding window with Xtract or KDecon, measuring deconvoluted features and quantitation traces.Search nodes search assigned databases for protein identification and characterisation.cRAWler nodes deconvolute fragmentation spectra.ProSightPD Consensus nodes handle tasks ranging from grouping redundant PrSMs into proteoforms to assigning PFR accessions. | https://www.proteinaceous.net/prosightpd |

| TopPIC [74] | Open source | No additional search engine needed | Any proteoforms | PrSM processing algorithm and MIScore | Three-step algorithm for proteoform identification (core): 1) Protein filtering, 2) Spectral alignment, and 3) PrSM E-value computation.MIScore (optional): A Bayesian model-based method for characterising modifications explaining unknown mass shifts in PrSMs. | https://www.toppic.org/software/toppic/index.html |

| pTop [75] | Open source | No additional search engine needed | Any proteoforms | Sequence-tag-based search and dynamic programming algorithm | pParseTD: Potential precursor detection using SVM, followed by deconvolution and deisotoping of MS/MS spectra.Proteoform candidate retrieval: 1) Extract sequence tags and search against the protein database index, 2) Generate candidate modifications from the mass difference between the precursor and the protein.Modification localisation and proteoform ranking using the pDAG algorithm to identify the k-best paths. | http://pfind.ict.ac.cn/software/pTop/index.html* |

| MSPathFinder [76] | Open source | No additional search engine needed | Any proteoforms | Sequence-graph approach | ProMex: LC-MS feature-finding algorithm.MSPathFinder: 1) Sequence graph construction, 2) Proteoform scoring against MS/MS spectra through graph searching, and 3) FDR estimation. | https://github.com/PNNL-Comp-Mass-Spec/Informed-Proteomics |

| Study | PTM | Key Proteins Involved |

MS-Proteomics Technique | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al., 2025 [90] | Ubiquitinoylation | SERCA2, SIRT2 | Co-immunoprecipitation combined with MS | Succinylation of SERCA2a, controlled by SIRT2, promotes its ubiquitinoylation and degradation by proteasomes in sepsis-induced heart dysfunction. |

| Li et al., 2025 [91] | S-nitrosylation | HBb, Trx, GSNOR | TMT-labelled LC-MS/MS | Identification of S-nitrosylated proteins associated with HFpEF. |

| Wu et al., 2025 [92] | Malonylation | IDH2 | Label-free LC-MS/MS | Malonylated IDH2 is downregulated cardiac hypertrophy. |

| Theofilatos et al., 2023 [2] | γ-Carboxylation | MGP, F2, GAS6, PROC, PROZ | TMT-labelled LC-MS/MS, Targeted Proteomics (Multiple Reaction Monitoring, MRM) | γ-carboxylated proteins are upregulated in female, asymptomatic and calcified plaques and drive carotid plaque clustering into subgroups with different outcome trajectories. |

| Yang et al., 2023 [93] | Lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation | MMP2, ALAD, EPB42 | Label-free LC-MS/MS | The Kbhb-modified proteins upregulated in aged hearts were primarily detected in energy metabolism pathways and localised in the mitochondria. |

| Liu et al., 2025 [94] | Lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation | COL1A1 | Label-free LC-MS/MS | Lysine β-hydroxybutyrilated COL1A1was downregulated in metabolic syndrome induced restenosis. |

| Wang et al., 2025 [95] | Lactylation | SERPINA3K, SERPINA3 | Label-free LC-MS/MS | The protective role of Serpina3k and Serpina3 lactylation though their secretion from ischemia-reperfusion-stimulated fibroblasts to protect cardiomyocytes from reperfusion-induced apoptosis. |

| Hasman et al., 2023 [96] | Oxidation | FLNA | Label-free LC-MS/MS | Oxidated FLNA is interacting cell-cell communication, neutrophil degranulation, and smooth muscle cell contraction. |

| Bagwan et al., 2021 [89] | 150 PTMs | MYH6, MYH7, PLN, TNNI3, MYBPC3, SCN5A, RYR2, CACNA1C | Label-free LC-MS/MS | Provided a resource of more than 150 PTMs in human hearts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).